#silures territory

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hike along the River Wye with friends the other day. Wasn't as long as we'd have liked but had fun. We did go into Chepstow Castle, but I'd left my phone in the car, so no photos, unfortunately. (I'll get some next time I'm there—I hail from a nearby town, so I'm down that way a few times a year).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Llanmelin Wood Hillfort

#iron age#llanmelin wood hillfort#ancient wales#silures territory#celts#ancient history#prehistory#hillfort

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

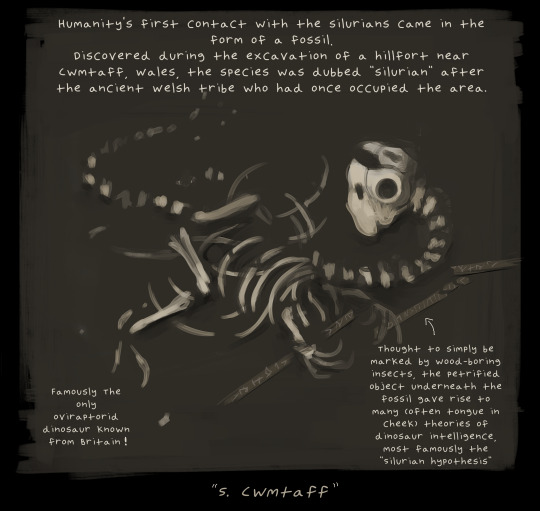

The genus Silurian ("Person of the Silures", in reference to the historical territory of Wales in which they were first found) was initially known only from a single fossil, notable in part for the unusual object fossilized alongside it (1). Though this was generally accepted to simply be a large petrified stick, the "Silurian Artifact" and the associated "Silurian Hypothesis" were often a point of discussion in the topic of dinosaur intelligence and the theory of pre-human civilizations. It wasn't until large-scale mining operations began to impede on their extensive networks of stasis chambers that the Silurians themselves finally woke up and were able to meet humankind in person. To the surprise of many (and dismay of a few) the Silurians were not the scaled, humanoid "dinosauroids" so often depicted, but colorful, feathered, and relatively goose-shaped. Most Silurians who were present in the planet's underground represent the gentry and high ranking military, who were given priority in the earth-based shelters. Most others were evacuated on large, extensive spaceships, all of which are yet to return to Earth. Due to this, the varied mindsets and cultures of the Silurians are in shambles at best, largely replaced by the speciesism and real estate concerns of the upper classes. (1) Much later, the original type fossil was identified as Rohlik, a student who fell to his death after attempting to drunkenly pole vault over a ravine with a large petrified stick.

#in universe cow tools is a reference to this#doctor who art tag#doctor who#All The Strange Strange Creatures#thank you rachel for reminding me of the origin of the term silurian . my life in your hands#speculative biology#silurians#my art

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Caratacus, sometimes known as Caractacus, was an ancient British king of the Catuvellauni tribe.

He is best known for his pivotal role in resisting the Roman invasion of 43 CE. However, it may indeed been Caratacus himself who triggered the invasion in the first place, though it must be said that the Romans were already looking for an excuse to invade anyway.

In the decades prior to the Roman invasion in 43 CE, the Catuvellauni appeared to have expanded, growing to become the dominant tribe in south-eastern Britain.

Some of this expansion came at the expense of the neighbouring Atrebates. The war was started by Caratacus’ father Cunobelinus, continued by his uncle Epaticcus and finished by Caratacus himself. The conquest of the Atrebates led their king, Verica, to flee to Rome where he requested assistance in regaining his throne and thereby giving the Romans the excuse they sought.

40,000 Roman troops landed on the south coast. Caratacus and his brother Togodumnus became the leaders of the resistance and they met the Romans in battle along the Medway and Thames rivers. Defeated both times, the territory of the Catuvellauni was conquered. But Caratacus himself was not.

He fled to the Silures in southern Wales. Together with the nearby Ordovices, Caratacus continued to resist the Romans, this time with greater success. Seven years later, the new Roman governor finally managed to bring Caratacus to battle and defeated him, though the man himself once again escaped.

This time he fled north to the formidable Brigantes, the most powerful tribe in southern Britain. But their Queen Cartimandua was in no mood to fight the Romans. She handed Caratcus over to his great enemy.

Caratacus was sent to Rome as a war prize, something that typically ends with ritual strangulation. However, for unknown reasons Caratacus was allowed to speak to the Senate, including Emperor Claudius himself.

Apparently he made such an impression that he was pardoned and allowed to live in relative comfort in Rome for the rest of his life.

Upon exploring Rome, Caratacus is said to have asked “And can you, then, who have such possessions and so many of them, still covet our poor huts?”

#history#real history#military history#ancient history#ancient rome#roman empire#roman history#rome#british history#ROMA series

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ganieda’s love...

"So raise me a house... Before the other buildings build me a remote one to which you will give seventy doors and as many windows, through which I may see fire-breathing Phoebus with Venus, and watch by night the stars wheeling in the firmament..." - from Geoffrey of Monmouth's LIFE OF MERLIN

“THE HOUSE AND OBSERVATORY GWENDDYDD BUILDS FOR HER BROTHER,

https://mistshadows.blogspot.com/2018/09/the-house-and-observatory-gwenddydd_42.html?m=1

~~

Sorry, in perusing the ‘VitaMerlini’, which touches on the relationship between him and his sister (sibling and possibly, sexual...Ganieda/Gwenddydd is sometimes conflated with Myrddin/Merlin’s legendary wife, Gwendolena, who crosses over in a confusion of genders and misprints with the slain king, Gwenddolau, who Myrddin serves up to the battle of Arfderydd/573AD, and whose death is said to have driven Myrddin mad with grief, resulting in his flight to the woods...), I’m reminded of Thomas Jefferson, and his adoration of his sister, Jane. Not b/c of fabricated charges of incest, mind you. Maybe Gwenddolau was actually a Queen, and it was Mryddin’s wife, who led men in battle, and was slain, which set his grief tale-spinning to insanity?? Incidentally, in Geoffrey’s account, Merlin, while associated the sorcerer aspect, is actually described as a warrior and a King of Demetia/Dyfed, the old territory of the Silures in SW Wales/around Moridunum/Carmarthan...

Anyway, it’s hard to read the descriptions of the Mansion of the Stars which Mryddin’s/Merlin’s sister, Ganieda/Gwenddydd then builds for him in the forest, and not be reminded of Monticello, Thomas Jefferson, and his (oft’ complicated) relationships with the women in his life. The Man on the Mountain, like Heimdallr in his Mountain fast Fortress, ever gazing to heaven and earth and the affairs of humans...

Ganieda’s construction succors Merlin’s soul, as she looks after his recovery, and she partakes of his intellectual and esoteric studies of the heavens and nature. Taliesin even appears for a coffee-clatch, or a brewskie (from their craft beer microbrew operation, no doubt...) at times.

I‘ve read that Jane Jefferson Jr, the oldest sister of Thomas Jefferson, was described as his favorite. Equal to him in accomplishment and intellectual inclination. From some random 540page examination of the Jeffersons at Shadwell (The childhood home of Young Jefferson...), is alluded Thomas Jefferson’s epithet to his beloved sister, taken in the bloom of her maturity...

“There is no record of Jane Jr.’s cause of death, burial, or funeral in 1765, only her brother’s idealized memorisl six years later. He wrote in Latin:

~ “Ah,Joanna, best of all girls. Ah, torn away from the bloom of vigorous age. May the earth be light upon you. Farewell, forever and ever.” ~

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235406197.pdf

~~ I draw story arcs to analogous characters as archetypes connected in different eras. Roman-Britain/Arthurian legend/LateRoman Europe/Heroic Age myth and history I’ve always loved. Jefferson was a more recent fascination, over the last decade, and continues; though admittedly, I’m focused more on the DarkAge/Late Roman Britain plotline right now.

In the same way my fictional Scottish Lady physician with whom Jefferson takes up an affair during his years in PreRev Paris, relates in part to my 2nd Century protagonist, and my take on SubRoman British Guinevere, Jefferson brings to mind aspects of Uther and Mryddin/Merlin. I actually don’t differentiate Uther from Merlin, as I‘ve made my own completely unsubstantiated conclusion that they’re indeed, aspects of the same person. In the Medieval Welsh corpus of poetry, and folk-legend, it’s written that Uther was the enchanter, seer, and sorcerer who studied all the laws of nature through the Universe. He blends wonderfully with the mythic toponomy of Snowdonia as well—where a Mountsin Named Cadair Idris—The Seat of Idris/Isdernus/Yder (??Uther??), was said to be the seat where a powerful king, one IDRIS, who knew all the mysteries of the universe, would sit to gaze at the stars.

This is where one wonders if the compilers of these texts, scribbling away in some drafty monestary in newly Anglo-Normanized Medieval Wales, weren’t just a little familiar with Gnostic/Judaic/Islamic mystical tracts journeying with returning Crusaders and merchants, back from the cultural and literary treasure troves of MiddleEastern cities. A Kabbalistic icon steps from the pages of these esoteric texts, one Idris—a prophet/seer/scholar/advisor to kings/philosopher/etc. He’s likened to Enoch, of the Old Testament, utilized as a poetic/literary/mythical figure lending wisdom and insight to receptive minds seeking true Enlightenment...

In my sober and rational pursuits, no I’m not one of the Woo-Conspiracy types who believes there was something preOrdained about Mystical America or her Mystical (lol, Rosicrucian??) Founders, or that there’s some relation to Late Roman/Post Roman era Britain or Europe. On the other hand, we should all recall, it was Jefferson who suggested Hengist and Horsa arriving to the shores of Britain, as the face of the National Seal. Which, while a lovely token to milk for poetic license, in reality, simply suggests to me, Jefferson felt the legacy of representative demos in America arose first from AngloSaxon civil law, than from any predecessor trace of Roman law still practiced upon the British shores to which Hengist and Horsa supposedly arrived at Vortigern’s summons (dated anywhere from 425-449AD). Gildas says Britain was *ruled by kings, but they tyrants*, and while the AngloSaxon incursion was viewed as a punishment of God for the sins and excesses of the Tyrants/British War Lords who continued to battle with each other, by the centuries in which the Venerable Bede writes his British and Anglo-Saxon history from Northumbria, approx 300 years later, the AngloSaxons are the civilizing force, especially after they are Christianized, tempering Barbaric and Tyrannical Britons. God-Chosen to conquer and rule lands that the native British were not worthy to rule. One ought recall, the Catholic/Nicene church by this point was intimately associated as a vestige of Roman law and order, and while the post-Roman British rulers were Christian, they had fallen away from the dictates of Papal law, possibly following the heretical beliefs of Arianism or Pelagianism. And to Bede’s firmly Roman Christian mindset by the 8th Century (when he’s writing), it was the Catholic creed of Rome to which the first AngloSaxon Kings were converted, so making the AngloSaxon kingdoms the worthy inheritors of Old Roman civilized values brought to order and rule the unruly Britons...consider that a tale (biased and inaccurate, undoubtedly as I’m writing on the fly) in how doth the Pen of Propoganda flourish between conquered and conqueror.

One has only to read the Historia Brittonum to view the Cymric perspective in balance to Bede. Anyway, I’m just sort of lovin’ on how affectionate was the relationship between Ganieda/Gwenddydd for her brother, Merlin/Myrddin, in building his sylvan abode, atop a mountain, to gaze at the heavens and their eternal tales. Having recently taken up StarGazing, incidentally, SkyApp rocks! Also, the mythic histories of our constellations actually drives a lot of the archetypes behind my protagonists.

Back on point, I can’t help but see Monticello as Jefferson’S Mountain and Sylvan abode, from where he could examine and advise on the World as the Seer and Political Poet/Philosopher he was, and find comfort away from the Real World messiness of back-stabbing and scheming envelopong the governing factions of his Early America. It’s no original insight of mine, but a reiteration of certain scholars over the years, who point out that Monticello was probably the truest reflection of Jefferson’s mind and soul. Personally, I feel Monticello, and maybe his other haven of Lynchburg, were really his truest loves, even before the women of his family—including the Hemings. In a Triad completing his opus magnum, the University of Virginia embodied his ideal, as a true Temple of Science.

In fictional recounting, it’s Caroline Eleanor Graham who points this out to him years into their hidden liaison, after she’s come to America with their daughter, conceived on the eve of the Bastille’s fall. That her own pursuit of medicine, a discipline she’ll encourage their daughter to follow, against Jefferson’s own wishes (though, there’s nothing he can do to forbid this, as he’s not her acknowledged father), takes her too much into the world, amid the rabble he’d rather not abide. Too much an Amazon to the Domestic Angel for who Monticello has been constructed, MarthaWaylesSkelton’s ghost never far from the shadows lining the halls and recesses of that great mansion. Thus, in a weird way, Jefferson drafts, and eventually initiates the University of Virginia, as an unspoken dedication to the daughter he could never acknowledge. The daughter, who completes this whole cycle by intending to help establish the first Women’s Medical School of Philadelphia...

And in a scene I scratched out in rough form a long time ago, with an aged Caroline, come to make her peace at the grave of Jefferson, in the autumn after his death, written before my side-Road wandering into Arthuriana, it’s Caroline, mourning with the oldest Jefferson daughter, MarthaRandalph, who senses his presence somewhere wandering, freed at last, searching out the mysteries elucidated amongst the stars. The scene is meant as parallel to Uther’s funeral scene—3 Fold death at the hands of the Visigoths after Vouille/507AD—where Guinevere travels in haste to Gaul, aware of his brutal loss, those of his most loyal warriors.

She accuses Clovis of delaying the arrival of his own Frankish forces, until Uther and his British/Amorican host had fended off the strongest contingents of Visigoth Alaric’s onslaught, bringing an easy victory to the Frankish king, at the price of British lives. This is my version of Camlann 1.0. Britannia’s Tribal confedracy is left in a succession crisis, until her son, Vortiporius/Vortipor returns from serving Theodoric the Great, who also maybe his father. Or, Uther is his father...

Anyway, adapting scenes of Arthur taken away to Avalon in a boat, Uther’s body, b/c of his descent from Volsung blood, and Yngling-Swedish nobility, a pragmatic Christian when convenient, with a classical education of philosophers and scientists, and a son of Wotan as well, he’s not to be buried, but sent off as a ship burial, with his horse and slave women sacrificed to accompany him to the OtherWorld, joined by his various other fallen warriors from Vouille—very like the Ibn Fadlan treatise of the ship burial he witnessed while traveling amongst the Rus. Guinevere sending forth an arrow lit by fire, to immolate the funeral ship sailing into a western sun. Maybe the ship is cast off to sail from Finis Terre/Breton coast as it burns. Maybe it’s sent north, toward an island off the Frisian/Germanic coast, called Hagaloland (???), which on some Roman maps, was called “Insula Aballona” (that’s disputed...but marked as that, on the Digital Map of the Roman World...). Hence, the grave of Arthur, or Uther in this case. “Oeth and Anoeth”-a thing of wonder, unknown to the world of men.

And Guinevere, Venaura in my etymologizing, standing at the shore, with the bow and arrow at her side, stoic in her sorrow, her only daughter, Gwenog/Fyndocha/Nennoch (Saints Lives...), weeping with her face buried in her hands, heart heavy, and her youngest son, Vortipor/Artuir, barely come to manhood, angered in his grief at his father’s death, an anger he doesn’t know how to release yet. He kneels before the sword Mimung, Uther’s blade, on the other side of his mother, head bowed to hide his tears.

Fostered in Ravenna, in Theodoric’s court, and unknowing as yet, the full truth of his siring. Begotten of 2 Fathers, Volsung and Amalung. And from the Votadini blood of the Cawnur, from his mother, British, Scandian, and Ostrogoth heritage, son of the Wolf/Uther, son of the Lion/Theodoric, but before all, Son of the Mother/Venaura. Mabon, blessed youth, son of Modron...

Yes, Vortipor, is one of Gildas’s 5 Tyrants. “The bad son of a good king,” per his own castigation, as Arthur mab Uter, translated, not as “son of Uther”, but rather, “terrible son,” b/c in his youth, he was terrifying. His father, Aergol Lawhir/Agricola, arises in Demetian genealogies. The Irish form of Vortipor is Gartbuir, and as the ‘G’ drops out in early protoGaelic forms, and the Brythonic prefix of ‘Vor-‘/Gor/Gwr-‘ (high/noble/strong) is actually synonymous with ‘Ar/Ardd/Art-‘, we’re using some pretty loose applications of philology to turn Vortipor, the Tyrant of Demetia into Artuir Imperator...we also have Ida/Aebba of Bernicia as his comrade, and based off Ida/Ebba, a general in Theoderic’s army, when the Ostrogoths finally mobilize through 508AD, to join their Visigoth cousins, and halt Clovis’s advance to the Mediteranean, winning back a good portion of southern Gaul, and joining the Visigoth and Ostrogoth territories from Hispania to the Balkans...

Artuir/Vortipor is a part of that campaign, before returning to Britannia. Ida the Ostrogoth commander, comes with him—eventually establishing Bernicia after Artuir’s death many years later, wherein he marries Artuir’s widow, Beara/Bebhionn-Vivian-after Who, it’s said, Bamburgh, the center of Bernician power, was named. But first, Ida helps his comrade claim sovereignty over the island, circa 515AD, and Northern Sea Kingdom founded by Uther, ruling over the peoples residing through Jutland/Scandia-Geatland. I do adopt a bit of Geoffrey and Layamon here...

I also have to admit a certain obsession with Theoderic’s daughter, Amalsuintha, as well. As she essentially is raised with Artuir in her father’s court, growing into an educated, strong-willed, beautiful woman (as the accounts of her describe), and the 2 of them unaware of their potential blood relation, they fall in love in their early adolescence, taken by adolescent hormones, they end up sleeping together. Which Theoderic only discovers after the act. And blows up, like an enraged father would, over his daughter’s lost virginity, but he’s more horrified at the potential of incest. Notice, the parallel with Arthur and Morgana. No child is born of the indiscretion, but an equally guilt-ridden Artuir finally decides it’s time to return to his homeland, and Amalsuintha marries Eutharic.

Years later, when Amalsuintha is the only survivor of her father, and her son by Eutharic, after the failed gambit to claim the Italian throne against rival Ostrogoth contenders, she’s finally condemned to exile and death on an island (still said to be haunted by her tears, when the winds rise into storm) in Lake Bolsano. Altering reality, in fact, she’s rescued/abducted by a bunch of British and Northmen, sent by Artuir to offer her haven on British shores. She’s eventually courted by Yffi/Uffa of Deiran Northumbrians, and becomes not only the source of Geoffrey’s eponymous “Marcia”—the Queen who is said to have established The Mercian Laws compiled by Alfred the Great in the Great codex of AngloSaxon legislation— but she’s also the grandmother of Aelle of Deira. The Deiran King who starts the ball rolling toward uniting Anglian and Northern Briton into Northumbria, as a United Kingdom, and the Star of the North, as it came to be known.

Basically, the sum game here is, my take on the tale of Uther/Merlin, Guinevere, Arthur, and other sundry cast, isn’t only a tale of the end of Roman-Britain. It’s actually a tale, in which they participate, to actively see what remained of Rome upon their beloved Isle of the Mighty, transition into a NewWorld, borne by the newest colonizers of Scandinavian and Germanic lands, mingling—Sometimes by love, sometimes by war—with the native inhabitants of British and Roman progeny, to create a new nation...fighting for recognition upon a new Medieval European stage, flawed, hopeful, tumultuous, brutal, struggling to lend voice to the weak and exploited, an ever-evolving clash of power and ambition, versus justice and compassion... Sort of a familiar tale, right? In the ongoing story of America, and her predecessors...maybe her future? Meh, anyway, too many hours wasted here...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let’s talk tactics: Highland Charge

The Scottish Highlands historically has maintained its own unique culture which touches on virtually all aspects of life, food, drink, fashion, family, religion and even warfare. In the art of warfare the Scottish Highlands contributed in two ways one its rugged topography leading to a guerilla style of warfare and two in its infantry tactics and one that conjures almost a romantic vision, the Highland Charge. Before we discuss the tactic itself, we need to know the history of the region from ancient times until the modern era and how topography and tradition shaped the Highland Charge.

Historically, Scotland has been viewed by many an invader to be wild and untamed land. This was true of the Romans during the age of Roman Britain from the 1st-4th centuries AD. The Roman legions encountered a number of various Celtic tribes that caused them troubles in the modern day regions of England, Wales and the Lowlands of Scotland. The areas that often leant the Romans the most difficulty were areas of rugged topography, namely the Britons of Wales in particular the Ordovices and Silures of the mountains of North Wales and valleys of South Wales respectively. Topography in war is a sometimes underappreciated part of strategy and it took many years and much loss of life and the development of forts and garrisons to finally subdue these tribes in Wales. The same can be said of the Highlands of Scotland. The Lowlands known to the Romans as Caledonia was conquered but this remained the greatest extent of Rome’s northward expansion. To the north in the Highlands with its rugged mountains, hills and many glens were a related but distinct Celtic people, the Picts, who spoke a language identified as Celtic but somewhat distant from the Common Brittonic southern tribes.

The Romans associated the Picts as pirates in later Roman Britain along the coasts and fierce warriors in the interior of the country, conducting raids and disappearing into the Highlands before the Romans could send legions after them. Rome’s response to this was to build and garrison Hadrian’s Wall along the modern English/Scottish border. The Picts were never subdued by Rome unlike the rest of Britain and this was to have a ramifications overtime and echoes throughout history in the Highlands in which they resided.

In time as the lower portions of Britain saw the Romans retreat, leaving the Romano-Britons to their own defense and the subsequent establishment of the Welsh and Cornish as distinct Celtic nations so to would the Picts meld with their fellow Gaels from Ireland and Western islands of Scotland’s coast giving birth to the modern Scots. While the southern Britons in the start of the Middle Ages faced the Anglo-Saxon threat. The Scots merged into their own kingdoms with the Gaels becoming overlords of the Picts and eventually both Celtic confederations synthesizing into one distinct entity.

In time Scotland, like the rest of British Isles was subject to Viking raids and the establishment of Viking petty kingdoms, but unlike England and even parts of Ireland, Scotland’s Viking rule was largely relegated to the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland islands on its periphery, the Highlands and much of lower Scotland remained the Scots Gaelic speaking land that forged out of the blending with the Picts. The topography of the Highlands as always contributed to this isolation.

As the Middle Ages wore on, the Kingdom of England would see troubles in its attempts to subdue Scotland, especially of note was the Scottish Wars of Independence against England under Edward I and Edward II of England. Despite some English successes their overall rule of Scotland remained somewhat limited due to in part to Scotland’s difficult to manage geography and its Clan system.

The Clan system had been a tradition found in Scotland and Ireland throughout the centuries, an important dynamic that social groups were built around. The Highland clans had a fierce sense of independence from both the English and Scottish crowns and from each other at times, alliances were formed and rivalries as well. Murder, warfare alternating with peace and cooperation were part of Clan lifestyle throughout the centuries. The romantic and distinct image of the kilt and tartan clad Highlander Clans really forged in the 15th-17th centuries. Gradually, English rule, settlement and influence over the Lowlands of Scotland lead to the spread of the English language being spoken along with a distinct derivative Germanic language called simply “Scots” quite separate from this the Highlanders retained their Scots Gaelic language and Celtic traditions. Once again geographic isolation a contributing factor.

The Highlander Clans alternated their allegiance to the Crown of Scotland when it suited them. Some clans would rebel against the Crown while others supported them, less out of honor bound duty to the king and more pragmatically for the chance to rid themselves of a rival and gain riches and territorial expansion for their own clan. Clans were led by chieftains who in time were granted titles of nobility and rewarded with wealth and land for their service to the Crown. Highlander Scots became famed for their prowess in combat and became mercenaries throughout Europe, serving in various armies at various times. Some Highlanders became involved in England’s conquest of Ireland, namely after the Elizabethan era establishment of the Plantation of Ulster in the North of Ireland, Highlanders would side with both the native Gaelic Irish and English and Lowlander Scots depending on motivation ranging from cultural and familial ties to money and the promise of wealth. Ultimately, the English gained control over Ireland and the Scottish Highlanders added to the mix with Lowlanders and English to form the Scots-Irish or Ulster-Scots community of Northern Ireland.

By the late 17th century Scotland had much upheaval due to Stuarts of Scotland becoming the royal dynasty of England as well. They remained separate kingdoms under one monarch. The War of Three Kingdoms and the English Civil War along with religious fervor all caused Highlanders to alternatively suffer and profit, largely depending on which winner they would back. By the year 1688, James II of England/VII of Scotland with his Catholic leanings was overthrown and in the so called Glorious Revolution by his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband and his Dutch nephew and her cousin William, Prince of Orange and Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic. They were crowned William and Mary of England and a de-facto personal union now existed between the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, Ireland and the Dutch Republic. James II/VII fled to France and later to Ireland to conjure up support among the Irish Catholic populace in hopes of regaining the throne, he also raised some support from loyal Scots and French soldiers too. This started the Williamite War, the British theater of the Nine Years War. William III of England now forged an army of Protestant forces made of English, Scottish, Irish, French, Dutch and Danish troops. Famously in 1690 at the Boyne River north of Dublin, Ireland, James and William’s armies met. However, the better trained Protestant forces won the day and James fled Ireland ultimately returning to France. However, he never accepted in theory that he or his direct Catholic descendants were not the rightful rulers of Britain. This was to have repercussions in the form of the Jacobite Rebellions and it would play out its final stages with the Highlander Scots and the famed Highlander charge.

The House of Stuart tried to regain the British throne in exile with French support in the early 18th century. William and Mary had no children and they were succeeded by James other daughter, Anne. Anne like Mary and William was raised Protestant and under her rule Great Britain was formed with the 1707 merging of the Crowns of Scotland and England officially as one with a single parliament based in London as opposed to a separate Scottish one as had been the case for the last century. Anne in turn passed away without an heir and was replaced by her closest Protestant relative, the Elector of Hanover from Germany, now George I of Great Britain.

The Jacobites were supporters of the Stuart royalist cause in exile and hoped to restore them to the throne of Britain. Jacobites were so named for the Latin name for James was Jacobus. Jacobitism as an ideology had Stuart restoration as it central tenant but the individual motivations were varied largely depending on the country the Jacobite supporter was located in. In Ireland, it was support for a Catholic monarch in and the promise of religious toleration that James II had granted earlier. In England and Wales a Catholic minority showed Jacobite support but largely its greatest support was found among royalist conservatives or Tories who believed in the divine rights of kings and felt the Glorious Revolution had been an unlawful usurpation and was in violation of what they saw as God’s natural order. Nevertheless, the vast majority of England and Wales were Protestant and anti-Catholic so it is a matter of academic debate among historians just how strong Tory support of Jacobitism really was. In Scotland the reasons were also varied. For some, the Jacobite cause was in solidarity amongst the Scottish Catholic minority. For Highlanders, their own feudal Clan system prized a tradition of feudal service to a landlord, namely the King. Despite the Highlanders varied legacy of service and opposition to the King was a matter of pragmatism but the essential relationship between Highlander Clans and the Crown was still rooted in a traditional belief in the divine rights of a monarch as feudal landlord of all Scotland and the Clan chieftains were loyal subjects granted a certain degree of autonomy in exchange for their recognition of King’s nominal authority and service to the Crown in times of need. This established a looser form of nobility than the later English influenced tradition. However, the traditional ideological and religious causes were in reality only the surface for Highlander support for the Stuart cause, as always economics, a sense of autonomy coupled with what they saw as a defense against an encroachment on their way of life was the primary motivation. Opposition to the Act of Union 1707 which united Scotland and England into one nation under a common monarch and Parliament was viewed by some Highlander Clans, particularly in the northwest of Scotland as to the detriment of Scotland namely for economic reasons and due to certain laws barring Scottish nobility from serving in the House of Lords in London, opposition to the Union was also strong in Edinburgh, the modern capital of Scotland and seat of its own Parliament.

From their positions in France and later Rome, Italy the Catholic Stuarts with French funding often tried to stir rebellions to their cause back in Britain. From 1689-1745 a number of Jacobite Rebellions occurred with the goal of Stuart restoration being central to their goals. 1715 and the final one of 1745-46 were the most notable, particularly for their support among the Highlander Scots.

1715′s rebellion was a clash of Highlanders in some ways. Under John Erksine, 6th Earl of Mar Highlander clans were rallied to the Jacobite cause and army was assembled with took over the Highlands and spread on down to Stirling Castle in the heart of Scotland. They had declared James II’s son James Francis Edward Stuart the new King of Scots, he was also referred to as the “Old Pretender”. In opposition to him was the Hanoverian British government and its commander in Scotland, John Campbell, 2nd Duke of Argyll. Campbell was a well known Highlander Clan with the Earls and Dukes of Argyll as its primary chieftain, the Campbells of Argyle had become very wealthy and politically well connected, perhaps the most well connected Highlander Clan in Scotland by the 18th century. Argyll led his force against Mar the Battle of Sheriffmuir in November of 1715. Both sides would claim victory but it was inconclusive, the Highlanders fought on both sides of the battle, largely depending on which clan one was a member. Ultimately, the Jacobites were beaten at the later Battle of Preston and the cause was frustrated in its goal once more.

1745 would see the most famous Jacobite Rebellion, it was an outgrowth of the concurrent War of the Austrian Succession. During the greater European wide War of the Austrian Succession, France and Prussia formed a coalition with Spain and other German and Italian states against Austria, Great Britain, the Electorate of Hanover and the Dutch Republic with other German supporters and limited Russian support. The new Jacobite leader was Charles Edward Stuart, known to the Jacobites as the “Young Pretender” after his father and to the Scots he was affectionately called “Bonnie Prince Charlie”. Charles was smuggled into Scotland to start an uprising when British military power there was weakest due to the bulk of Britain’s military being on the continent in war against the French coalition. Charles had hoped for French support to help knock Britain out of the war and raise him to the throne but bad weather prevented this from happening. Nevertheless, he gathered local support mostly from the Highlanders of northwestern Scotland.

He captured Edinburgh and was declared King and subsequently the Highlander Jacobites routed the Hanoverian British government forces in September 1745 at the Battle of Prestonpans, thanks to the Highland Charge. Further success was later had at Falkirk Muir in January 1746, once again the Highland Charge was instrumental to Jacobite success. However, by spring of 1746 the good fortunes of the Jacobite cause was fading. That winter they had marched into England toward London which caused a panic. They made it as far as Derby but realizing the French support they long hoped for never materialized and now facing a large, disciplined and experienced government army fresh from war on the continent, under the command of Prince William, Duke of Cumberland and son of King George II, the Jacobites returned to Scotland in high spirits but achieving no last strategic outcome. With Cumberland in pursuit the Jacobites retreated to the Highlands themselves, there they hoped to blend in and lead the government force on to ground of their own choosing where they could defeat them decisively.

Since 1689, government forces had been often been overrun by the Highland charge tactic in battle. Largely this was due to lack of discipline in government troops and the Highlanders fighting on topography of that catered to their advantage. The Duke of Cumberland was aware that these elements had lead to government defeat in the past, he was not apt to repeat the mistake of past commanders. The battle that finally took place in April 1746, known as the Battle of Culloden, fought near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands was not fought in the hilly or mountainous terrain that favored the Highlanders but instead on a boggy moor ground which slowed their advance in the face of modern weaponry (muskets and canister shot from cannons), the result was an hour long battle culminating in the last Highland Charge in history and the last major battle on British soil. It ended in bloody fashion for the Jacobites, Charles was thoroughly defeated, though he escaped Scotland back to the continent, disguised in drag. His Highlander force was butchered in the aftermath of the battle and so with Culloden died the Highland Charge tactic and effectively the Jacobite cause with which it had become so linked...

The Highland Charge tactic itself was essentially a infantry shock tactic. It required speed and relied on overwhelming force, it was psychological weapon as much as a physical weapon. Enhancement to its success was the charge being initiated downhill from the high ground head on into the enemy’s front or flank. The Scottish Highlands being rife with hilly and mountainous countryside, were a logistical nightmare for large armies used to fighting pitched battles, a lesson the Romans on down to the English had learned. In turn, they were the perfect place for a loose fighting formation like the Highlander Clans which operated as functionally a guerilla army against their opponents, they possessed local knowledge of the terrain and could blend in to hide from the enemy and then ambush and disappear seemingly at will. The tactic developed overtime from the original Scottish Highland tactic of fighting in tight formation. The Scots overwhelmed the enemy with their ferocity in battle, heavy weaponry and unsettling war cries. in battle they fought with battle axes or two-handed heavy swords called claymores. By the 17th century with weapons shifting to gunpowder based firearms and artillery, these tight formations were becoming vulnerable to ranged weapons which could cause many casualties at a distance. The Highlanders instead adapted the formation to one more reliant on terrain, looser and faster in format overall but still using the goal of traditional overwhelming force with unsettling war cries. The weapons and clothing were also adapted to better accommodate the charge. Instead of a claymore, the Highlanders carried a single handed broadsword which was large but lighter, they also carried a targe shield for defense and a smaller dirk thrusting dagger. Their clothing below the waist was reduced to a kilt.

The Highland charge was launched downhill on firm open ground at great speed in a wedge formation with loud war cries to raise the attacker’s morale as well as frighten a hopefully inexperienced and ill-disciplined enemy. The charge was meant to hit the enemy as high speed and break their lines with the “savagery” of their fighting, sometimes the mere sight and sound was enough unnerve and overrun the enemy. The Highland charge always anticipated a number of casualties due to a initial musket volley from the enemy, but the speed would be too much for them to reload in an era of single shot firearms. By the time the enemy was reloading they were struggling unnerved by the wails of the Highlanders and already being engaged with swords and dagger hacking and stabbing them to death. In many cases like at Killiecrankie, Prestonpans and Falkirk Muir the charge was successful due to the essential elements, speed, terrain and ill-disciplined enemies. Psychologically terrifying and well timed it proved to be a classic shock tactic. It shortcomings however were the danger of modern ranged weapons like artillery and muskets hitting the enemy at range, especially those fired by a professional disciplined army not inclined to turn and run at the sound and fury of the charge. Additionally, its implementation over broken ground or flat terrain or a combination of two in the face of modern weaponry like at Culloden could yield fatal consequences. The Highland charge has its roots and a resemblance in the ancient shock charge tactics of the Scots Celtic forbearers of Britain against Roman legions and other enemies. It embodied an ancestral connection and became a romantic image in and of itself, forever etched in the minds of historical memory when we think of the Scottish Highlands, kilted-tartan clad men running at full speed with sword, shield and dagger in hand, screaming like a banshee right into the enemy’s front, cutting down their opponent with fierce and wild abandon. The ultimate image of the barbarian fighting to preserve his way of life and freedom in the face of modernity. That’s the kind of image Killiecrankie and Culloden conjure, the image Walter Scott in the later Victorian era somewhat revived. The ultimate picture of Scottish romanticism on the battlefield...

#military history#scotland#romanticism#culloden#jacobites#highlands#1745#1715#1689#britain#celts#infantry tactics#shock tactic#highlander

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

English History (Part 2): Mesolithic

Mesolithic Period (11,600 years ago [9600 BC] – 4000 BC)

At Formby Point (on England's north-west coast) are 8,000-year-old human footprints, continuing for about 9.75 metres. They include the footprints of children. The men were about 1.55m tall, and the women about 1.35m tall. They were looking for shrimps and razor shells.

Formby Point footprints.

The Severn Estuary also has prehistoric footprints, from about 7,000 years ago. They fade away at the point where dry land once became swamp.

Severn Estuary footprints.

Mesolithic people burned the woods and forests to clear them, so they could build settlements or hunt for game more effectively. They also burned pine trees to make way for hazel trees – autumnal hazelnuts were a popular food source. They knew how to manage their resources.

Although they were “hunter-gatherers”, with dogs for hunting, the Mesolithic English did not just wander randomly. They ranged through group territories with well-defined boundaries that adjoined each other. They liked the areas where land met water.

Star Carr is a Mesolithic archaeological site in North Yorkshire, dating back around 11,000 years (to the early Mesolithic period). What is now the Vale of Pickering used to be covered in a great lake. A platform, made of birch wood, was built on the lake's bank. It may have been used for fishing, but probably was used for ritual ceremonial. The people wore amber beads, and left behind pig, red deer, duck and crane bones.

A round house, 3.5m in diameter, has also been found. It was made of 18 upright wooden posts, with a thick layer of moss & reeds so people could sleep on it. The house appears to have had a hearth; and the inhabitants used iron pyrite to start fires. They also used barbed antler points, and flint knices & scrapers.

The people of Star Carr used canoes to travel over the lake, and one paddle has been found. There are also 21 fragments of deer skull, some with antlers. They were probably used as shamanic masks or head-dresses, to enter the spirit of the deer. It may have been an early form of morris dancing.

Reindeer antler mask/head-dress from Star Carr.

Another Mesolithic settlement has been found at Thatcham (Berkshire), dating to around 8400 – 7700 BC, slightly younger than Star Carr. The people lived on the shores of a lake. Burnt bones, burnt hazelnuts, and patches of charcoal used for fires have been found. There are cleared spaces showing where small hut floors were.

There were hundreds of such settlements, many of them in coastal regions that now lie underneath the seabed. The coasts were once 21-30 metres higher than they are now, so settlements were lost as the seas rose.

One submerged village was found at Bouldnor Cliff off the Island of Wight. Divers saw a lobster flinging pieces of worked flint out of its burrow, and a settlement of craftsmen and manufacturers, hunters and fishermen, was revealed. A canoe carved from a log was found; so was a wooden pole with a flint knife embedded in it.

The Bouldnor Cliff site also has Britain's oldest boat building. Beneath it is a wooden platform from around 6000 BC, made of split timbers several layers thick, resting on round-wood foundations that were laid horizontally.

Tools found at Bouldnor Cliff.

The waters gradually rose; after the glacial era's ice sheets melted, it encircled the new archipelago of England, Scotland and Wales. This happened around 6000 BC, with the marshes and forests of the plains between England and the continent were obliterated by the southern North Sea. It probably took about 2,000 years overall, as the land slowly became swamp and then lake.

Earlier in prehistory, two huge floods had created the Engish Channel between England and France. Now with the newly-risen waters, 60% of the land surface became what is now England.

The tools made in England became smaller than those in continental Europe, and some types of microlith were unique to England.

Travellers still came to England from the continent – from north-western Europe, and the Atlantic coasts of Spain and south-western France. The migrations from the Atlantic coast were not a new phenomenon. These people had been colonizing the south-western regions of England throughout the Mesolithic, and by the time the archipelago was formed, a distinctive culture was flourishing in the western parts of England.

Those coming from Spain also settled in Ireland. “Hibernia” is the Latin name for Ireland, and is related to the word “Iberia”. The Iron Age tribe of the Silures (South Wales) always believed that their ancestors had come from Spain some time in the distant past. Tacitus stated that these tribal people had dark complexions and curly hair. They were later known as the Celts.

So by 8,000 years ago, there were already distinctions between the English regions. England's flint tools are divided into five categories. Those in the south-west had a different appearance to those in the south-east, which encouraged trade between the two regions. Individual cultures were being created, reinforcing geographical & geological identities (such as cultures established upon chalk & limestone vs. granite).

England can be divided into two zones – the Lowland Zone and the Highland Zone. The Lowland Zone covers the south and east (the midlands, Home Counties, East Anglia, Humberside, and the south central plain). It is built upon soft limestone, chalk and sandstone; it has low hills, plains and river valleys. It is a place of centralized power and settlement.

The Highland Zone covers the north and west, including the south-west corner of England (the Pennines, Cumbria, North Yorkshire, the Peak district of Derbyshire, Devon and Cornwall). It is mostly built upon granite, slate and ancient limestone; it has mountains, high hills and moors. It is a placce of scattered groups or families, independent from each other; it is hard, gritty and crystalline.

These two zones did not face each other. They faced outwards, towards the seas. The changes can be seen upon the ground itself. In Wessex, artifacts from one settlement stop where the chalk meets the Kimmeridge clays, showing that the people would move no further west. So regional differences began to spread.

Differences of accent & dialogue may already have existed. There was a language in the south-east that left traces in contemporary English – the words London, Thames and Kent have no known Germanic/Celtic root.

The people of East Anglia & the south-east may have spoken a language that developed into Germanic, and the people of the south-west one that became Celtic. The Germanic tongue would become Middle English and then Modern English; Celtic split into Welsh, Cornish and Gaelic.

In Wales and Cornwall, stones carved with Celtic inscriptions (from the Roman Age) can be found, but none have been found in southern England. Tacitus stated that by the time of Roman colonization, the south-eastern people spoke a language not unlike that of the Baltic tribes.

#book: the history of england#history#prehistory#geography#geology#classics#languages#linguistics#mesolithic period#britain#prehistoric britain#mesolithic britain#celtic britain#england#ireland#wales#formby point#severn estuary#star carr#isle of wight#bouldnor cliff

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Révolte?

Couve la révolte, si les gentils hollandais voulaient nous donner la main. Ici on ne joue plus, on crève. Peuple de la F. France urbaine, dans ton SUV t'as vieilli, tu te retourne dans ton lit, agité de haine, de peur, transpirant.

Les ogres du FMI, les loups gris en treillis, les technocrates en cravate, les hordes de l'est, solidaires et rageuses, les gosses harassés et paumés du sud méditerranée. Non pas une, mais dix armées enserrent ton cocon abimé et menacent de te réduire à peau de chagrin.

Les pandémies, anémies, obésités, vers, frelons et fourmis exotiques feront à ta terre ce que les silures et les écrevisses américaines avaient commencé.Tes forêts calcinées, rasées pour un profit dérisoire, vendues à la stère, ne retiendrons plus la moindre nappe d'eau polluée, d'ailleurs les bonnes sources comme les bon vins ont déjà été vendues à des fonds américains et chinois.

Tes terres rendues infertiles exhumeront les jus chimiques, les épandages incessants que tu pensais pouvoir infliger à ce que qui avait fait ta richesse jadis, en empoisonnant tes nourrissons de façon durable et pérenne.

Mais PIRE (pour toi), ce sont tes flics, tes profs, tes juges, tes toubibs à l'hôpital ou à l'hospice, les potentats urbains, chaque petit fonctionnaire de la république, qui seront amené à transformer ton territoire en prison à ciel fermé, ta porte blindée 3 points n'y résistera pas... Leur bélier est bien plus têtu que ta molle volonté ratiboisée.

Alors courre, Durand, courre Dupond, courre Simon, courre Bernard, courre Ducon, en vissant bien fort tes oreillettes bluetooth et en évitant sans un regard le "migrant" allongé sur ton chemin. Courre dépenser tes euros en yuan HK, ils sont le denier de ta quête impossible, de ta fin inglorieuse, impréparée et infiable...

Signé Fanon, Signé Glissant, Signé Furax!

PS : le stage de repositionnement personnel feng chui est annulé sans date de report. RV en télétub!

Cover the revolt, if the good Dutch wanted to help us. Here we no longer play, we die. People of urban F. France, in your SUV you've grown old, you roll over in your bed, agitated with hatred, fear, sweating. The IMF ogres, the gray wolves in fatigues, the technocrats in ties, the hordes of the east, united and angry, the exhausted and lost kids of the southern Mediterranean. Not one, but ten armies enclose your damaged cocoon and threaten to reduce you to grief. Pandemics, anemias, obesities, worms, hornets and exotic ants will do to your land what the American catfish and crayfish started. Your charred forests, razed to the ground for a derisory profit, sold per cubic meter, will no longer retain the slightest sheet of polluted water, moreover good sources as well as good wines have already been sold to American and Chinese funds. Your lands rendered infertile will exhume the chemical juices, the incessant spreading that you thought you could inflict on what had made your wealth once, by poisoning your infants in a lasting and perennial way. But WORSE (for you), it is your cops, your teachers, your judges, your medics in the hospital or in the hospice, the urban potentates, each small civil servant of the republic, who will have to transform your territory into a prison with closed sky, your armored door 3 points will not resist it ... Their ram is much more stubborn than your weak will ratiboisée. So run, Durand, run Dupond, run Simon, run Bernard, run Ducon, by screwing your bluetooth earpieces tight and avoiding without a glance the "migrant" lying on your way. Run to spend your euros in HK yuan, they are the denier of your impossible quest, of your inglorious, unprepared and infiable end ...

0 notes

Text

The Silures of South Wales

Iron Age Wales was under the control of five Celtic tribes before the Roman invasion of 43/44AD under Roman Emperor Claudius, led by Aulus Plautius. Whilst conclusive tribal boundaries are almost impossible to place, the Silures were certainly one of the larger tribes of Wales and probably commanded some respect in the Celtic tribes of Britannia. Their domain stretched from the Gower peninsula (Swansea) in the south west to the English county of Herefordshire and likely included some of that territory. Even for the Britons, the Silures were a warlike people. Whilst the southeast of England was initially subdued under the campaigns of Claudius and Aulus Plautius, campaigns led by the Legate Publius Ostorius Scapula aimed at pushing into the Welsh borderlands were resisted furiously by the Silures from 48AD. In league with the neighbouring Ordovices tribe, the Silures mounted a furious defence of the Welsh borderland, conducting an effective guerrilla warfare campaign lasting decades. It is at this time that the Silures and Ordovices are led by the British warlord, Caratacus, a man who claimed to be high king and whose aggression against neighbouring tribes provided the excuse for the Roman invasion. Many warlords claim the title of High King, but Caratacus, who led the Catavelluni and Cantii (south east England) was respected enough to not only be given shelter by the Welsh tribes, but emerge as a local general or even King of the two tribes. I shall elaborate on him in another post. From 49-52 AD, Caratacus led the Silures and Ordovices (and elements of other tribes who wished to resist Roman occupation) in guerrila warfare against the advancing Roman forces. However, in AD 52, he and his army was forced into meeting the Romans in the open and were duly defeated, prompting his flight to Northern England and the Brigantes tribe.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hike along the River Wye with friends the other day. Wasn't as long as we'd have liked but had fun. We did go into Chepstow Castle, but I'd left my phone in the car, so no photos, unfortunately. (I'll get some next time I'm there—I hail from a nearby town, so I'm down that way a few times a year).

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Celtic Coin of the Dobunni King Corio

This is a 'Tree Type' gold stater of the Dobunni tribe. It was struck circa 20 BC to AD 5 during the rule of Corio. On the obverse is the image of a tree-like emblem known as a Dobunnic Tree, with a pellet below. The reverse bears the name Co[rio] above a triple-tailed, stylized Celtic horse, with a wheel below and other symbols in the field. The Dobunnic Tree's meaning is unclear although corn, ferns and a form of a wreath have all been suggested as explanations.

The Dobunni were one of the Iron Age tribes living in the British Isles prior to the Roman invasion of Britain (43-84 AD). They lived in the southwestern part of Britain that roughly coincides with the English counties of Bristol, Gloucestershire and the north of Somerset, although at times their territory may have extended into parts of what are now Herefordshire, Oxfordshire, Wiltshire, Worcestershire, and Warwickshire. Their capital acquired the Roman name of Corinium Dobunnorum, which is today known as Cirencester. Unlike the Silures, their neighbors in what later became southeast Wales, the Dobunni were not a warlike people and submitted to the Romans before they even reached their lands. Afterwards they readily adopted the Romano-British lifestyle.

Corio was a 'king' of the southwestern Dobunni. No one knows if 'king' is the correct term for their leaders however, it is likely that this is what the Romans called them. The Dobunni rulers are only known from names found on their coinage and the exact order of each of their reigns has yet to be determined. Some of the other Dobunni kings’ names are Anted, Eisu, Aatti, Comux, Inham and Bodvoc.

#history#coins#celtic#dibunni#numismatics#corio#stater#gold#dobunnic tree#tree type#horse#wheel#ancient#britain

613 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Tale of Two Iscas

by Alison Morton Whenever I visit a town I'm drawn to the museum, especially (and sometimes exclusively) to see if there is any Roman stuff. This is what a 'Roman nut' usually does. Woe betide anybody coming in between me and tesserae, Samian ware or a nice bit of Roman concrete. Last year in Exeter was a special treat because it was the second of the twin Iscas, the other one I'd never seen. The Romans established a large castrum (fortified camp) named Isca around AD 55 at the southwest end of the Fosse Way as the base for the 5,000-man Legio II Augusta (Second Augustan Legion) originally led by Vespasian, later Roman emperor. Twenty years later they moved to Caerleon in Wales, which was also confusingly known as Isca. To distinguish the two, the Romans referred to Exeter as Isca Dumnoniorum after the name of the local tribe and Caerleon as Isca Augusta. I'd visited Caerleon decades ago as a student when I'd been working on the archaeological dig at Usk, and more recently when I was at a writing conference. But I'd never visited its twin, Exeter. Exeter – Isca Dumnoniorum The name is a Latinisation of a Brythonic name describing flowing water (Uisc), in reference to the River Exe. Like many early settlements Exeter began as a place of dry land by a navigable river; in Exeter's case on a ridge ending in a spur overlooking the Exe. The bonuses were a fertile hinterland, a river full of fish and access to a large protected estuary and the open sea. Although there have been no major prehistoric finds, these advantages suggest the site was occupied early. Coins have been discovered from Hellenistic kingdoms, suggesting the existence of a settlement trading with the Mediterranean as early as 250 BC.

Isca Dumnoniorum Castrum

In mid first century Exeter, a civilian community (vicus or canabae) inhabited by local tribespeople and soldiers' 'unofficial' families, grew round the Roman camp, mostly to the northeast. When Legio II Augusta left around AD 75 to go north to fight tribes in Wales, the camp grounds were converted for civilian purposes; its very large legionary bathhouse was demolished to make way for a forum, basilica and a smaller-scale bathhouse. In the late 2nd century AD, the ditch and rampart defences around the old fortress were replaced by a bank and wall enclosing a much larger area, around 92 acres. The course of the Roman wall was used for Exeter's subsequent city walls; the stones are a mixture of Roman and medieval. About 70% of this wall remains, and most of its route can be traced on foot. The settlement served as the tribal capital (civitas) of the Dumnonii and Isca Dumnoniorum seems to have been most prosperous in the first half of the 4th century: more than a thousand Roman coins have been found around the city and there is evidence for copper and bronze working, a stock-yard, and markets for the livestock, crops, and pottery produced in the surrounding area. Trade with the Mediterranean continued bringing luxuries like wine and fine pottery. In the 3rd century AD new stone wall and gatehouses were built. Rich people lived in townhouses with costly mosaic floors; other areas of housing fell into disuse or were converted into farmyards.

Display of pottery and glassware, Exeter Museum

In the museum, the Roman military presence is testified by hooks from legionary helmets, knives, armour hinges, armour tie hooks, armour buckles and hinged fittings, belt buckles, legionary apron fittings, strap ends, tent pegs, and horse harness fittings. These are all small things of life then, but precious to us now for the story they tell. But beside those, the cases display a rich variety of military and civilian basins, strigils, pots, jars, cooking implements, even glassware. And of course, tiles, mosaics, plaster and stone remnants alongside domestic rings, brooches, weaving weights, board games, keys and styli. And, of course, silver coins. As in any other part of the Roman Empire, the pickings show a rich diversity and sheer numbers of objects that even humble people possessed.

Display of military clips, ties and buckles, Exeter museum

In 410 AD the last Roman soldiers left Britain to defend Rome against attacks by hostile tribes. By then Isca's suburbs were being abandoned; there are few remains from this time. Dates of coins discovered so far suggest a rapid decline: virtually none have been discovered with dates after AD 380. By around 500, the basilica had fallen down and Isca Dumnoniorum's busy urban life was over. Circling back to AD 75, when the Legio II Augusta soldiers strapped on their marching boots and filed out of the castrum gate, I wonder what the effect was on the Devonian Isca. The heavy military presence was lifted; the drinking, rowdiness, the casual brutality, the gambling, testosterone, the whoring and the unwanted pregnancies. Many unofficial wives upped sticks and with their children followed the soldiers to their new home. However, the economic effect must have been significant for the the innkeepers, brothels, tailors, weavers, leather and knife suppliers, laundries and local food suppliers and grain merchants. Caerleon – Isca Augusta (Isca Silurum) The Brythonic name Isca referred to the River Usk which literally means 'river of flowing water' (tautology alert!). The suffix Augusta, an honorific title taken from the legion stationed there for 200 years, appears in the Ravenna Cosmography, a list of place-names covering the world from India to Ireland compiled by an anonymous cleric in Ravenna around ad 700. It's also referred to as Isca Silurum to differentiate it from Isca Dumnoniorum and because it lay in the territory of the Silures tribe. However, there is no evidence that this form was used during the Roman period. Caerleon, the name we know today, is derived from the Welsh for "fortress of the legion". Isca Augusta was founded by Governor Sextus Julius Frontinus during the final campaigns against the native tribes of western Britain, notably the Silures in South Wales who had resisted the Romans' advance for over a generation. It became the headquarters of the Legio II Augusta, a large fortress base on the typical rectangular castrum pattern and built initially with an earth bank and timber palisade. It remained their headquarters until at least 300 AD. The camp interior was fitted out with the usual array of military buildings: a headquarters building, legate's residence, tribunes' houses, hospital, large bath house, workshops, barrack blocks, granaries and, unusually, a large amphitheatre.

The excavated amphitheatre

Britannia was one of the most heavily militarised provinces due to its frontier status and hostile neighbours. Isca Augusta is uniquely important for the study of the conquest, pacification and colonisation of the island. It was one of only three permanent legionary fortresses in later Roman Britain and, unlike the other sites at Chester and York, its archaeological remains are relatively undisturbed beneath fields and the town of Caerleon. Excavations continue and one of the most exciting discoveries is a complex of very large monumental buildings outside the fortress between the River Usk and the amphitheatre. This new area of the canabae (settlement of traders, families and discharged soldiers) was previously completely unknown. And in August 2011 it was announced that remains of a Roman harbour had been discovered in Caerleon. I have a little secret about that. Walking by the fortress wall in the fine rain a month before, loving and absorbing everything, I bumped into a fellow walker. We chatted and he obviously caught on that I was a 'Roman nut'. He told me he was a member of the University of Cardiff faculty involved in digging the site. Poor man! I bombarded him with questions.

Mosaic and pottery finds, Roman National Legion Museum

But as he was speaking to another enthusiast, he told me they were developing excavations as there had been indications there was much more to find. There always is, of course, but his was a humdinger. He revealed that remains of a Roman harbour had been found in a meadow by the river.. All very hush-hush, so please not to speak about it. I almost jumped up and down, but did manage to keep my dignity. You can look through the gallery of pictures for more images of what Roman Caerleon might have looked like. Most of the sites I have been to are ruins, but there is memory in those stones. Touching walls, walking on mosaics, breathing the air of the place and sometimes seeing the same view they saw.

Prysg Field Barracks

The walls of Prysg Field Barracks at Caerleon, the only Roman legionary barracks visible in Europe are gone, but the foundations are still there showing their outline. The amphitheatre – the largest ever uncovered in Britain and once romantically (and mistakenly) said to have been the site of Arthur's Round Table of Camelot – is grassed over. The timber grandstand which would have seated some 6,000 shouting, cursing and cheering legionaries and townspeople is no more. These and the legionaries' swimming pool, the make you wonder who the people were who trod the same pathways, swam in the pool, placed bets, got drunk, made assignations. The light grey sky, the misty rain, the waves and slopes of the landscapes, your hand touching the stone and concrete in a place where so many people had lived and worked two thousand years ago give you something that no book or picture or film can give you. Sources: Bidwell, Paul T. (1980). Roman Exeter: Fortress and Town. Exeter City Council. Hoskins, W. G. (2004). Two Thousand Years in Exeter (Revised and updated ed.) National Roman Legion Museum, Caerleon University of Cardiff, Dr Peter Guest BBCwww.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-14628286 [Accessed 20/2/2017] For more on Caerleon discoveries see youtu.be/nwx00pe2HH8 [Accessed 20/2/2017] [Photographs - author's own, one time use allowed for this article] ~~~~~~~~~~ Alison Morton has misspent decades clambering over Roman sites throughout Europe. She holds a MA History, blogs about Romans and writing. Now she writes, cultivates a Roman herb garden and drinks wine in France with her husband of 30 years. She writes the Roma Nova thriller series featuring modern Praetorian heroines. She blends her deep love of Roman history with six years' military service and a life of reading crime, adventure and thriller fiction. All five books have been awarded the BRAG Medallion. SUCCESSIO, AURELIA and INSURRECTIO were selected as Historical Novel Society's Indie Editor's Choices. AURELIA was a finalist in the 2016 HNS Indie Award. The sixth, RETALIO, is due out in April 2017. Buying links: alison-morton.com/books-2/buying-links/ Blogsite: alison-morton.com Facebook: www.facebook.com/AlisonMortonAuthor/ Twitter: twitter.com/alison_morton

Hat Tip To: English Historical Fiction Authors

0 notes

Text

The Silures, continued

Despite losing their leader and control over the Welsh Borders, the Silures simply fought on in guerrilla fashion, rarely fighting in the open where the disciplined Roman legions held the advantage. In the fluid political situation in Britain, it is possible that the Silures took the leadership and tribal influence of leading tribal resistance to the ongoing Roman occupation. Put simply, before the Roman occupation, the Catavelluni of south east England were the leading tribal power in Britain, due to their strategic position and territorial size. Following the invasion and rapid defeat and occupation by the Roman occupiers, the Catavelluni obviously lost this position. With other tribes being subdued, capitulating or agreeing to one sided client kingdom status (as the Iceni and Brigantes did), the Silures assumed the status of leading opposition to Roman forces and their subdued allies. Joined by their neighbours, the Ordovices, and elements of tribes or volunteers who sought to resist Roman rule, it can be argued that during this time, the leaders of the Silures were High Kings of Briton, by virtue of being led by Caratacus and then by waging constant, fierce guerrilla warfare against the Romans. Obviously, this is speculative and almost wishful thinking at best, especially as the Ordovices weren't exactly junior partners in this alliance and what was left of "free" Britannia was shrinking fast. And of course, Scottish and Irish tribes weren't in the fight yet. But for a brief time, a Welsh tribe could be argued to be High Kings of Britain. The Silures weren't idle in their status as leading the tribal resistance to foreign occupation. Despite his success in pursuing and capturing Caratacus and so soon after his victory at Caer Caradoc, Ostorius, came under increased pressure from the Silurians. Sometime in 52 AD (I have no clue in what order some of these events take place, blame Tacitus), the Silures trap a unit of legionnaires and inflict heavy casualties, killing their prefect and eight centurions. A foraging/scouting party nearby is routed and to make matters worse for the Romans, two auxiliary units, one cavalry, one infantry, sent to rescue the trapped legionnaires are similarly defeated. Ostorius, his situation going from bad to worse, is forced to commit the legions to halt the what is possibly Rome's worst defeat in Britain yet. Despite this escalation, two auxiliary cohorts, either 1,000 or 2,000 strong, are captured and enslaved. The Silures, seeking to build a new British confederacy, distribute these slaves amongst neighbouring and allied tribes, binding these tribes to resistance against the Roman occupation and secure themselves as leaders. The turn of fortunes for the Silures is huge. From losing their high king and the decisive battle of Caer Caradoc mere months before, the Silures remain unbowed and fiercely independent. Ostorius, who by now was facing the disintegration of Roman control of the Welsh borders, died suddenly, as Tacitus says, "worn out by care". In the ensuing chaos, it is mentioned that the Silures defeated an entire legion, with the possible targets being either Legio II Augusta or Legio XX Victrix, but with both legions surviving to be mentioned in later engagements across the Empire, the defeat can't have been too major. Nevertheless, the Silures continued their tactics of harrying Roman forces, surrounding their fortresses at which they could only be displaced at great difficulty. A small campaign, led by the new governor, Quintus Verainius, in 57-58AD against the Silures, amounts to nothing. However, in North Wales in 60AD, the Romans destroy the last Druidic stronghold in Britannia, the Isle of Anglesey. With most Roman forces stationed on the Welsh borders in 61AD, defeat was inevitable. By 78 AD, the Silures were defeated by the Romans, but for 40 years, the Roman Empire was frustrated by a warlike tribe from South Wales.

3 notes

·

View notes