#this includes that queer theory unit in my senior year of high school

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The first four chapters of Bram Stoker’s Dracula are the gayest thing I’ve ever had to read for class, bar none.

#this includes that queer theory unit in my senior year of high school#dracula#media analysis#sort of?#not creative writing#bram stoker#count dracula#jonathan harker#that solicitor is a down bad for this old ass vampire#i will die on this hill#bimorebooks posts

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

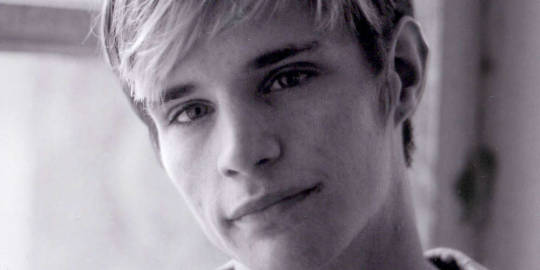

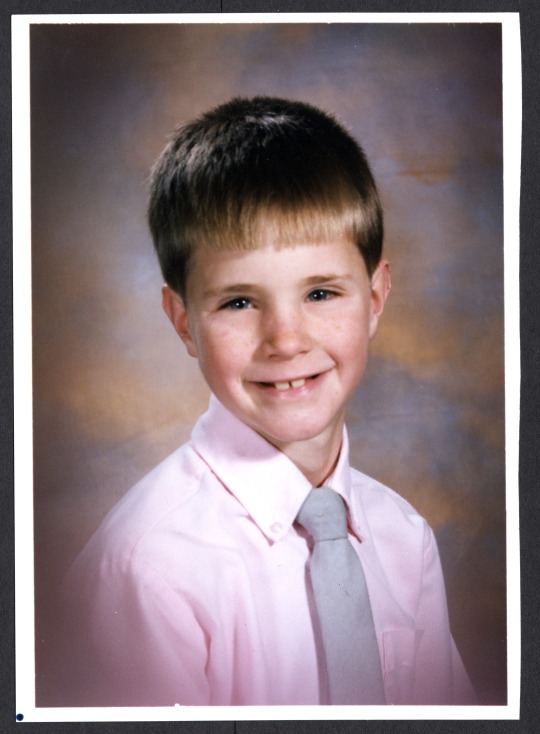

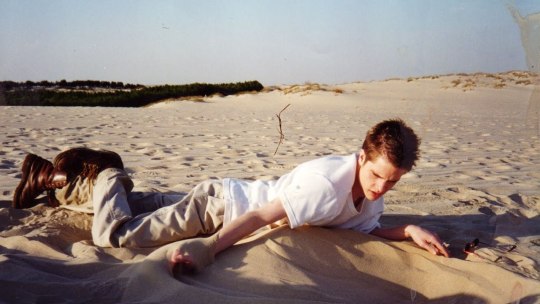

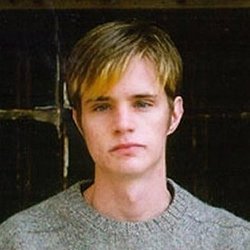

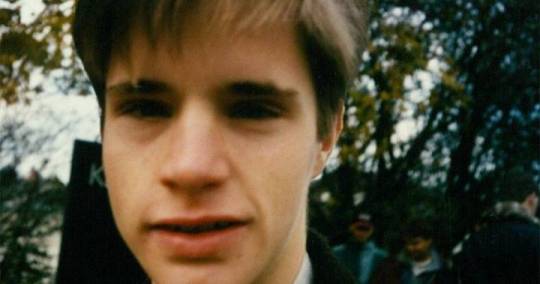

Chapter Twenty-One : MATTHEW SHEPARD

Matthew Wayne Shepard was born on December 21st 1976 in Casper, Wyoming to mother Judy and father Dennis Shepard. He was the oldest of two sons, with younger brother Logan, five years his junior.

Of Episcopalian faith, the family stayed put in Wyoming until David got a new job as an oil industry safety engineer. For 16 years, he worked in safety operations for Saudi Aramco in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, starting during Matthew’s senior year of high school. After schools in Wyoming, he then graduated at the American School in Switzerland in 1995. He was often described as a sensitive, soft-spoken, 5'2 and 100 pounds kind young man, interested in politics and theater. His father said “(he) had a special gift of relating to almost everyone. The was the kind of person who was very approachable and always looked to new challenges. Matthew had a great passion for equality and always stood up for the acceptance of people’s differences”.

Matthew Shepard was gay. He knew it from a very young age but did not come out until after high school to his mother. Judy was very accepting of his son’s sexual orientation and knew for years as well.

During his senior year, Matthew accompanied three of this classmates to Morocco. During this vacation, he was beaten, robbed and raped by a gang of locals. The perpetrators were never apprehended. The assault caused multiples traumas that translated into flashbacks, panic attacks, nightmares, paranoia, depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts. Matthew was then hospitalized on more than one occasion due to his clinical depression.

After briefly attending a small liberal arts school in North Carolina, Matthew went on with his life. With a lesbian friend, he moved to Denver then in 1998 to Laramie and enrolled at the University of Wyoming. He studied political science and international relations, joined the college’s LGBT student alliance and became the student representative for the Wyoming Environmental Council. He envisioned a career in Foreign Service.

On October 6th, 1998, only a few months after moving to Laramie, Matthew was approached by two young men in a bar called the Fireside Lounge. They pretended to be gay, just like Matthew and offered him a ride home.

They drove to a remote, rural area and proceeded to rob, pistol-whip and torture him. They tied him to a fence in near-freezing temperature, set him afire and left him to die. Reports described that Matthew was beaten so brutally his face was completely covered in blood, except where it had been partially cleansed by his tears. His skull was fractured to the excess of pistol shocks.

Matthew was tied to that fence for eighteen hours. He was discovered on October 7th by a cyclist named Aaron Kreifels who initially mistook Matthew for a scarecrow. He was still alive when a police officer arrived at the scene. The officer, Reggie Fluty, used her bare hands to clear an airway in Matthew’s bloody mouth as her medical gloves were faulty and she ran out of supplies. She was informed while Matthew was in the hospital that he was HIV-positive and that she might have been exposed to the virus due to cuts on her hands. After a few months of AZT treatments, she tested negative.

Matthew was transported to Ivinson Memorial Hospital before being moved to the more advances trauma ward at Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado. He had fractures to the back of his head and in front of his right ear, severe brainstem damage, which affected his body’s ability to regulate his heart rate, body temperature and many others vital functions. A dozen small lacerations around his head, face and neck were noticed. His injuries were deemed too severe for doctors to operate. Matthew never regained consciousness and remained on life support. He was pronounced dead six days after the attack at 12:53 am on October 12, 1998. Matthew was 21 years old.

The two murderers were arrested on the night of the attack, due to an altercation with two hispanic youths that prompted police interventions. While searching one of the men’s car, the police officer found blood-smeared gun near Matthew Shepard’s shoes and credit card. They were initially charged with attempted murder, kidnapping and aggravated robbery. After Matthew’s death, the charges were upgraded to first-degree murder, making the two defendants eligible for the death penalty. As they later tried to persuade their girlfriends to provide alibis for them and dispose of evidence, one of them was charged with being accessories after the fact.

According to one of the murderer’s testimony, the two targeted Matthew as victim for robbery but the physical attack was triggered by the victim who put his hand of one their knees. As we shall call them, Murderer 1 pleaded guilty to murder and kidnapping charges. To avoid the death penalty, he agreed to testify against Murderer 2. He was soon sentenced to two consecutive life terms.

Murderer 2’s trial ran from October to November 1999. His girlfriend testified to the fact that they pretended to be homosexuals to get Matthew in the truck and rob him. His lawyer attempted the worst kind of defense, GAY PANIC DEFENSE, arguing temporary insanity by alleged sexual advances from the victim. It was rejected by the judge. The jury found Murderer 2 not guilty of premeditated murder but guilty of felony murder. He later received two consecutive life terms with no possibility of parole.

In the days following the attack, candlelight vigils were held all around the world. Matthew’s death was a cataclysm event felt across the entire Queer community and beyond.

On the day of his funeral attended by over 700 people, protestors from a Baptist Church circled the entrance of the church with signs bearing homophobic slogans like “Matt in Hell” or the classic “God Hates Fags”. They organized anti-gay protests during the trial of Murderer 2, prompting a friend of Shepard, Romaine Patterson, to assemble a group of people dresses in white robes and gigantic wings to block the protestors. That didn’t stop Matthew’s parents from having to hear gay slurs and insults directed towards them.

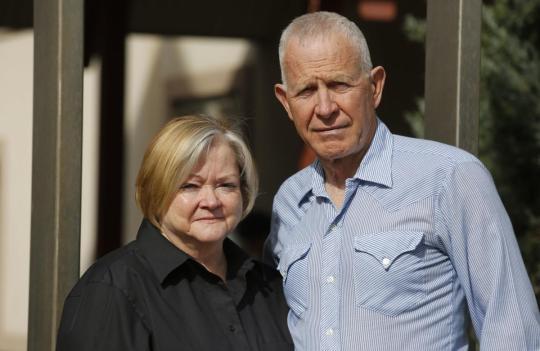

In December 1998, two months after Matthew’s passing, Judy and Dennis founded the Matthew Shepard Foundation, a non profit organization for outreach, advocacy and educational purposes. Judy is now president of the governing board, while younger brother Logan works there as well.

Judy and Dennis kept their activism alive to honor their son’s memory. On October 11, 2009, Judy addressed a rally for LGBT rights and said “I’m here today because I lost my son to hate… No one has the right to tell my whether or not he can work anywhere. Whether or not he can live wherever the wants to live and whether or not he can be with the one person he loves . No one has that right”. The same year, she released a memoir, The Meaning of Matthew.

New legislation to address hate crimes became a hot topic during the coverage of the murder as under United States federal law and Wyoming state law, crimes committed on the basis of sexual orientation would not be prosecuted as hate crimes. A bill was introduced in a session of the Wyoming Legislature that defined certain attack motivated by victim identity as hate crimes. The motion failed on a tie.

Under President Clinton, several attempts were made to extent federal hate crimes to include LGBT individuals. In November 1997 then in March 1999 to the Senate and the House of Representatives, with only the Senate passing it in July of the 1999. The next year, both houses passed the legislation, which was then stripped out in conference committee, whatever that bullshit is.

On March 20, 2007, The Matthew Shepard Act was introduced to the U.S. Congress as a bipartisan legislation. It passed the two houses once again but was dropped when President Bush indicated he would veto it if it reached his desk.

It took until October 28, 2009, when President Obama signed the approved measure into law to be implemented and secure hate crimes status for LGBTQ+ people. Judy Shepard was present next to the President.

No matter the somewhat homophobic drug theories that went on years after the incident, Matthew’s murder served as a window into the violence against the Queer community. It was a catalyst for the legal protections and federal hate crime legislation that the United States has today. Matthew Shepard was a ghostly figure in my life ever since I saw his picture for the first time when I was 17. I’ve spend hours lost in that picture. He lived 21 years on this earth and he’s been gone for just as long. Today, I honor him.

0 notes

Text

Endless Island

By Matthew Pifko

I. Coffee, Whole Milk, and 2 Sugar Packets

My mom is drawing on a napkin at the diner while we wait for our food. She sketches out long, parallel lines across the fragile fabric, careful not to tear through the tissue-like surface. She is drawing me a map of Long Island - more specifically, the roads that criss and cross it. I sip coffee out of the stout, ceramic mug. I’m now seventeen, I’ve already decided I like coffee, and it’s too late to turn back. It tastes bitter and sour and it burns my tongue a little bit, but I diligently sip it anyway. I don’t really like the taste, but I do like the way it makes me feel buzzy and present (I never say that of course, because that makes me sound like a drug addict).

“So, this is Sunrise Highway,” she declares, pointing to the thin line of ink. “And that’s connected to 347, right?” I murmur into my steaming cup. “No. Sunrise Highway runs along the south shore, all the way to the end, y’know, like where Montauk is. And the Long Island Expressway runs here, over near us on the north shore, from the city out to the middle of the island. 347 is one of the roads connected to the Northern State Parkway, which is that windy and old road that was built before they had big expressways on the island.”

I nod blankly, and mutter something. Just a noise of affirmation to get her to think my mind is still on the conversation. The truth is that I couldn't care less about the long, flat strips of concrete that connect Long Island. I don’t care what they’re called. I don’t care where they go. None of this matters to me when I’m seventeen, because I’m not going to live here. In fact, pretty soon, my license will be useless to me, since I’ll be soaring on a gleaming bullet of a subway. The second I graduate from my claustrophobic little prison of a high school, I’m going far, far away. As far as I’m allowed to go. At the moment, I have compromised with Boston - a city that isn’t exactly Los Angeles, but is at least a couple hours away from New York. I tell myself there’s a good chance I’ll transfer over to LA in a year, anyway. To me, Long Island was the place to escape from, the starting line of a marathon, a ledge to leap from. This is not to say Long Island is Bumblefuck, Idaho. In fact, the Island is positively teeming with people, and there are more flooding in every day. So many people that they’re packed like sardines into this tiny strip of land clinging to the East Coast, the price tags on their houses going up and up and up until the entire place is swallowed up by the ocean. I was determined to never be one of them. Convinced that I couldn’t be one of them, even if I tried. I knew Long Island wasn’t “for” me, the same way I knew as a child that scary R-rated movies weren’t “for” me. The thing about Long Island, and more specifically, my quaint little homogenized tourist town, is that I always felt like an “other” there. In terms of postcolonial theory, “otherness” is defined as a sort of psychological divide constructed by conquerors to separate themselves from the conquered - to my understanding, this group of conquerors includes Spanish conquistadors, British imperialists, Nazis, and even those wealthy, boisterous, self congratulatory high schoolers who call quiet kids

“fags”. In other words, “otherness” is a weapon used by monsters of all shapes and sizes. As an other, I understood that, on some level, I was lesser than the conquerors. Maybe because I was queer. Maybe because I was Jewish. Maybe because I wanted to be an artist. Or maybe because I just felt like Matt Pifko didn’t belong there, like his brain chemistry was incompatible with the air he breathed in Port Jefferson, Long Island, New York, United States, zip code 11777.

II. Learning

Don’t worry, this isn’t a tragic backstory. In high school, I wasn’t bullied or tormented or even excluded. I had a superpower - I was selectively invisible. That is, “Queer Jew With Anxiety” wasn’t exactly stamped on my forehead. My voice was deep. My hair was straight. My nose was normal. My body wasn’t twitchy or nervous. My face was square enough. My beard grew patchy, but it grew. I was tall, tall enough that no one questioned my masculinity. I laughed a lot, and I was funny. I looked depressed, or maybe just tired, but in a relatable way. After all, what high schooler isn’t “depressed” these days?

“Your face is my mood,” my friend once said to me as I stumbled into the fluorescent white building at 7:18 am.

When you ask people what superpower they’d want, they always say “flying” or “time travel” or some ridiculous shit like that. I say invisible, because being figuratively invisible is great. To walk down the hallway and not feel eyes on you is to feel power in high school. To be invisible is to be able to blend in anywhere, to fit into any friend group, any clique, any niche. Information is power, and the less information, the less control they had over me. I was slippery. Being translucent is even more powerful in a small town like Port Jefferson, where the local mothers gossip on their Facebook forums and around dinner tables, where the same 70 kids who went to pre-k together went to high school together as well. Port Jefferson was a special small town, in that it was a literal port. Located on the North Shore of Long Island, Port Jefferson has a ferry system that constantly shuttles tourists from Bridgeport, Connecticut into our quaint little town. Stepping off this ferry, one looks down the barrel of Main Street, a bustling cardboard cutout of coffee shops, bars, and everything in between. Thus, tourist traps selling useless knick knacks would open and close every season along Main Street, a new vintage board game store replacing the new crystal shop from last year. During the summers, my parents would complain about the mobs of strangers running into traffic downtown. I never understood why it made them so mad until I got a car of my own and almost hit wandering pedestrians on multiple occasions. In Port Jefferson, you’d swear you could actually feel eyes on you. Think 1984, but Big Brother is a network of parents who were once the popular kids in Port Jefferson High School back in nineteen-seventy-whatever. And now, their offspring are the popular kids once again, like some sort of inbred dynasty. To express otherness was to be shunned out of the community. To be invisible was to live on their watch-list. Nothing scared the denizens of Port Jefferson more than invisibility - they had a fear of blindness, of not being able to peer behind the curtain.

This was their town, and they’d be damned if anything or anyone was awry in their town. To these lifelong townspeople, a town had to be possessed. A town had to be owned - and therefore it was their job to own it. To control it. To keep it the same. To keep the others out. I remember going to a stage crew party senior year, and finally stepping into the old fashioned, brick-built mansion of one of these Port Jefferson dynasties. Their son, in my grade, controlled the entire theater department, to the point where he was actually paid to manage the other kids (other kids including me and my friends on the art team). Walking around this palace, seeing the off-kilter smiles of his parents as they greeted me, I felt genuine terror. Could their gazes pierce my thin armor? How much did they know? How much did they see?

From time to time, my invisibility would scare me. I’d think about dying in some horrible car accident on the LI Expressway, my consciousness and interior life gone before I could blink, with no one ever knowing that I was gay. No one ever knowing why I was an irritable and inconsolable asshole from time to time, why I holed myself up in my room listening to Frank Ocean and The Smiths for hours. At my funeral, they’d shrug, and just figure I was a strange boy. Often, I’d think about confessing my queerness on a paper, locked in a box that they could only find after I died.

This is not to say that I had no meaningful friends in high school, or that my parents didn’t know me at all, or that I was dead inside from freshman year till the day I graduated. After all, there were smaller, safer ways of exposing my otherness, whether it was my unwavering liberal political allegiance or my undying commitment to twisted horror cinema. It’s just... when you’re an other on Long Island, in Port Jefferson, you get scared what would happen if you ever truly lost your power. Being slippery is good. It means you won’t get caught. Even when I came out to my closest friends in the sticky spring of senior year, I felt scared. I felt my invisibility fade away, my body now opaque and ugly. I was seen, and I could be caught. Nothing’s worse than feeling like you could be trapped in Port Jefferson.

III. Endless Island

When I try real hard to visualize Long Island, to visualize the idea of Long Island, I always come back to the days I spent canvassing for Suffolk County Democratic Legislator Sarah Anker, a mission that spread from the summer to election day 2017. Trump had already taken over the White House, so there was an element of hopelessness to the whole affair. There was also a little rebellious spark in that uphill battle, making our fight for office a tad exciting.

I had taken up the internship with two of my friends from high school. Together, we traced the windy roads every Saturday, using the dots on our printer paper maps to find the targets of our campaign. Each week, we would get new black and white rectangles of Long Island, the tiny roads threaded out like a spider’s web across the page, the black circles that indicated houses appearing to me like trapped flies. On the page, we could indicate whether that

resident we had spoken with supported the candidate, supported the opposing party, refused to say, didn’t speak English, wasn’t there at all, and so on. Our campaign supervisor was Tim, a tall, slim man in his early 20s. Most importantly to seventeen year old me, Tim was openly gay. Gay. Gay, like how no guy in my high school was openly gay. The very thought of Tim existing, running this little organization, sent excited chills through my body. He was here, he was an “other”, and he was living and breathing just like the rest of us.

Since the three of us Port Jefferson boys had just gotten our licenses, we would swap on and off driving, one of us spending our precious gas money at a time. I drove my beat-up 1996 Lexus that my family had purchased for 3,000. Leland drove his dad’s silver, scratched 2003 Honda minivan. Dylan rarely drove, but when he did, he drove the sleek black Volkswagen that his mom normally used. Leland, with his twitchy hands and manic laugh, was probably the worst driver out of us three (we may have gotten pulled over once or twice), but he drove the most. He liked driving. I liked it when he drove, for in these hours I could just listen to the laughter of my friends, the tinny music coming from the rusted speakers, and the hum of the air conditioning. I would stare out the big rectangular minivan window at the endless rows of box houses, their color changing from tan to grey to maroon to blue to grey to black to tan to grey. When the car stopped, we would split off in three directions, each of us knocking doors, pacing down the pavement in search of potential voters. When we walked during the stretched out summer days, it was always too humid. When we walked during the inky black autumn nights, it was always too frigid. Canvassing, in its essence, was an “other” invasion - we invaded these boring neighborhoods, these undisturbed sectors, infiltrating their tranquil suburbs with our Democrats and our queerness and our papers, our papers that we left on their doorstep whether they liked it or not. They would be forced to see our faces, to hear our voices. Often, I felt like a deep sea explorer, diving deeper into the trenches of Long Island and seeping into their private lives through the cracked roads I once resented. Knocking on these endless doors, peering into endless sets of eyes, was that fertile mix of strange, scary, and thrilling that defines the best moments of adolescence. Sometimes, staring out into the vast Boston cityscape, I miss those ugly houses a little.

But really, when I think of Long Island, I don’t think of a place. A specific, singular snapshot doesn’t come to mind. Rather, I think of driving through the suburbs in Leland’s creaky minivan, the roads blurring together, the yellow dashes mixing with the white lines, the street lights gliding into one another. Sometimes, after a party that ended too early, or after our parents had come home too soon, we would flee to the car, and just drive in circles around Long Island. Maybe stop and get some shitty fast food. Sit in the parking lot and talk a lot and then settle into a warm silence. Get back in the car. Look at the small towns pass by, peer curiously at the anonymous rows of houses. Go to the beach and creep onto the pitch black dunes. Listen to each others’ shaky breath, and the sound of wind hitting the water. And then drive some more.

Acknowledgments

Joan Didion deserves top billing here, without whom this essay would not have existed. I’d like to thank Mary Kovaleski-Byrnes for giving me the opportunity to create my first piece of writing about my queer identity. Clare Jackson, thank you for bringing this text to where it is now. I will always remember when tears fell down your face as you read my first draft in class. Eitan and Abby, thank you for the further assistance and final touches. Long Island - I don’t know what to say to you.

0 notes