#traumatizing and illegal. but hysterical

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

mr robot isnt even that hard to understand yall just stupid lol

(fr like. seeing people still post shit takes 6 years after the last season premiered is wild... like did yall even finish this shit or not? 'oh i dont get it this character was brilliant why they died???' 'oh why did x character do y in episode z?' why this why that bruh fr u gotta get rid of that mindset of wanting to rationally and cleanly explain everything and assuming things always add up to a neat little conclusion with no loose threads or unfinished puzzles and realize that sometimes the open-endedness and multiple possible interpretations fading into the background are there for a damn reason, to make you reflect and think about how all this applies to your life and the real world around you. how things are connected on a level much deeper than most people think in their daily lives. phenomenal, stellar, thought- and emotion-provoking tv, carefully thought out to the finest detail, and all people want to do is force it into some convoluted, safe, clean little box with a ribbon on top and sell it as criticism of the modern capitalist society or whichever interpretation they decided to go with today. but whatever. nothing i say can change your view if you just can't see what's in front of you.)

#personal#elliot is an unreliable narrator and that should already make you suspicious of everything that happens#i've said it before but mr. robot feels eerily similar to lee chang-dong's burning#trade offer: you'll get one of the best shows in contemporary tv#but most of the (online) fans are redditors#its hysterical to me actually#traumatizing and illegal. but hysterical#its no coincidence the quality of the fan theories and takes is so shit

1 note

·

View note

Photo

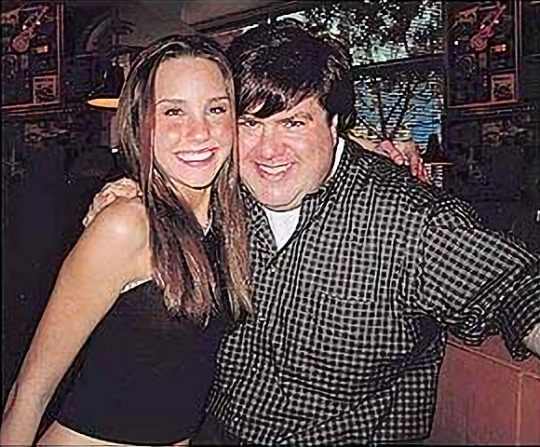

Dan Schneider’s Disgusting Nickelodeon Empire

The goo, roughly the consistency of an egg white, was being squirted repeatedly on the teen actor Jamie Lynn Spears' face. Spears was shooting an episode of Nickelodeon's Zoey 101 in which a costar accidentally sprays her with a yellowish-green liquid candy called a "goo pop." But Dan Schneider, the show's meticulous creator, found problems with every take, Spears' costar Alexa Nikolas recalled, making a crew member squirt the syringe of goo at Spears over and over again.

Then, in one take, the slime hit Spears squarely on her forehead, dripping down her face and mouth.Schneider started laughing hysterically, Nikolas said. Others laughed as well, including Spears' mother, who was on set at the time. Nikolas said she heard one of her male teenage castmates say, "It's like a cum shot.

"That was the shot that made it into the show."We're talking about a minor," Nikolas said. "I think Jamie was 13, and they're squirting stuff on her face to make it look a certain way."

At the time, around 2004, Schneider was on his way to becoming one of the most powerful people at Nickelodeon. Schneider joined the network in 1993 as a writer on All That.

His first series, The Amanda Show, starring Amanda Bynes, established his brand of kid-friendly slapstick comedy. Subsequent hits like Zoey 101, iCarly, and Victorious helped turn Nickelodeon into a powerhouse, leading The New York Times to crown Schneider "the Norman Lear of children's television."

A heavyset former child star with a round face and rumpled button-downs, Schneider was obsessively hands-on as the creator, executive producer, and writer on his shows, according to his cast and crew. He maintained a constant presence on the set, chatting with teenage casts for hours after filming ended. Winning Schneider over could be a career-making move; he was known to craft bigger roles and even new series for his favorites."

He was what every kid star wanted," said Nikolas, who played Nicole Bristow on Zoey 101. "They wanted to be on his show." Nikolas said Schneider could be volatile and described the on-set environment as "traumatizing." Once, Britney Spears intervened in the contentious relationship between Nikolas and Jamie Lynn Spears. Nikolas said the pop star screamed at and berated her, leaving her sobbing in the fetal position. Schneider set up a meeting to discuss the situation. Nikolas remembers being summoned into a large conference room with Nickelodeon executives, alone. Nikolas, who was 13 at the time, said Schneider started yelling at her, telling her it was "not called 'Nicole 101'; it's called 'Zoey 101.'" She recalled silently crying, as executives nodded along to Schneider's tirade.

Afterward, Nikolas told her mother she wanted to quit Zoey 101. Her mother demanded that Nickelodeon release Nikolas from her contract, and less than a week later, she was off the show."I was so happy to get out of there," Nikolas said. "It was the best day of my fucking life."

Writers and crew members had their own problems with Schneider. Six writers described working for him as a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the success of Schneider's shows provided rare stability in a chaotic industry. On the other, he regularly demanded 14-plus-hour days and expected writers and crew members to be available "24 hours a day, seven days a week," a former writer said.

A writer who worked with Schneider for years said that when he finally quit, the creator tried to erase his name from unaired episodes before being told it was impossible and illegal to do so.

"If you were in his favor, work was joyful and fun," Christy Stratton, a writer for The Amanda Show, said. "But if you upset him — even unintentionally — he would burn you to the ground."

Female writers suffered their own particular brand of indignity.While many of Schneider's leading actors were teenage girls, including Jamie Lynn Spears, Ariana Grande, and Miranda Cosgrove. Schneider once "openly stated he didn't like having female writers in the writers room" and rarely hired them, a longtime Nickelodeon writer said. None of Schneider's shows credited more than two female writers in the entirety of their runs; Zoey 101 and Drake & Josh had zero.

Kayla Alpert said that on her first day writing for All That, Schneider declared that women were not funny and dared her to name a single funny woman. "It speaks to something very dark and very wrong," Alpert said.

In 2000, Jenny Kilgen, one of two female writers on The Amanda Show at the time, accused Storybook Productions — the production company for the series — of gender discrimination and of creating a hostile work environment, two people with direct knowledge of the claim told Insider. Schneider was not named as a party, but during the mediation proceedings Kilgen said she was uncomfortable with Schneider's repeated requests for massages, according to the two people.

As part of the mediation, the other female writer on The Amanda Show wrote a letter, which Insider viewed, in which she said Schneider asked her and Kilgen to perform embarrassing activities for money and to massage his shoulders. The writer wrote that Schneider once pressured her into simulating "being sodomized" while she was telling a story about high school, to her embarrassment.

The case was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount, the two people said, and Kilgen left the television industry. When contacted by Insider, Kilgen declined to comment.

Schneider was known to hug female crew members for extended periods "as a joke," making people uncomfortable, two crew members said. Numerous Nickelodeon staffers said Schneider asked for massages from adult female colleagues throughout his time at the network. Kerry Mellin, who worked as a costumer on Schneider's shows for 14 years, and another costumer said Schneider received weekly massages from a third member of the costume team. Both said Schneider would ask the woman to reach under his shirt to massage him. The person close to Schneider said Schneider "regrets ever asking anyone and agrees it was not appropriate, even though it only happened in public settings."

"It was humiliating to observe a respected colleague having to do this," Mellin said. Schneider's power at Nickelodeon meant his shows continued to be greenlighted despite allegations that he created a hostile work environment. It also meant he could push the envelope more than your typical show creator, some people who worked with him said. One writer recalled Schneider receiving an email with a few minor notes from Nickelodeon's standards department. Schneider displayed the email on a large monitor in the writers room. Instead of addressing concerns, the writer said, Schneider responded point by point with gibberish — writing "flippity floo" and "flippity flam" — to "make this big show of thumbing his nose at the network." On-set employees rarely pushed back against Schneider, another writer said, because "you just didn't cross Dan — he was a really scary presence."

And while the network had a multitiered system to review content before it aired, some said it did not always succeed in preventing footage that could be viewed as inappropriate.Two people recalled Schneider fighting with Nickelodeon over teenage actresses' costumes on "Victorious," with Schneider — who signed off on all outfits — campaigning for the skimpier options. Some who worked on Schneider's show "Victorious" said they were uncomfortable with scenes they felt were overly sexual, such as a sketch in which cast members rubbed food on the exposed midriff of Victoria Justice.

In one battle, the network thought a skirt for Justice, then 17, was too short, while Schneider thought it was perfect, according to a writer and the costumer Kerry Mellin. The writer said Nickelodeon and Schneider compromised by making the skirt "3 inches longer." Daniella Monet, who started filming "Victorious" when she was 18, making her the eldest of the teenage cast members, told Insider some of the actors' outfits were "not age appropriate." "I wouldn't even wear some of that today as an adult," Monet added.

Swimwear was also a contested topic, a different writer said, as Schneider campaigned for teen actresses to wear "whatever was the most revealing." In her memoir, McCurdy wrote that she was pressured to wear a bikini on iCarly, with the head of wardrobe telling her The Creator explicitly asked for two-piece swimsuits.

The person close to Schneider said all costumes "were seen and approved by dozens of people, including the parents of the actors, and the state-licensed teachers on set." Mellin said that no one would force child actors to wear outfits if they voiced discomfort and that she did not feel Nickelodeon sexualized child actors more than other shows did. However, she said, people were reluctant to voice concerns to Schneider because they wanted to keep their jobs. "It's an imbalance of power," Mellin said. "Jennette felt it, the designer felt it, I felt it, all of us feel it."

Innuendo is not uncommon on children's television; the person close to Schneider said Schneider would "include some jokes intended for the parents." But four writers and crew members said Schneider proposed scenes they felt were overly sexual for teenagers on a children's show. A video showing scenes from Grande's time on Victorious went viral this summer; it includes several shots of Grande putting her big toe in her mouth, as well as pouring water on herself as she hangs upside down on her bed. One scene shows Grande with her eyes closed, moaning and squeezing a potato in both hands, begging it to "give up the juice." The sketch, as well as the ones involving Grande's nibbling her toe and pouring water on herself, is from a series of online extras that a database from Writers Guild of America West credits Schneider with writing.

Two writers said Schneider was almost singularly responsible for this online content, which they felt could sometimes be inappropriate, especially in the early seasons of Victorious when the Grande sketches were filmed. One said writers "largely avoided set when the web shows were being shot because they were largely very cringe."

The longtime Nickelodeon writer recalled feeling uncomfortable with another online extra in which the cast rubbed food on Victoria Justice's exposed midriff, turning her "into a hamburger" and squirting her with condiments. Monet said that after filming a Victorious scene in which she ate a pickle while applying lip gloss, she reached out to the network to express concern that it may be too sexual to air. The network aired it anyway.

Monet emphasized that Schneider is not the only one to blame. The network, as well as the department of standards and practices, had to sign off on everything. Monet added that Schneider's male-dominated writers rooms could result in some hypersexualized content. Most of Victorious, Monet said, was "very PC, funny, silly, friendly, chill.""But once in a while," she said, there'd be a moment like the pickle scene. "Do I wish certain things, like, didn't have to be so sexualized?" Monet said. "Yeah. A hundred percent."

For years Schneider's behavior went unchecked by Nickelodeon as he created hit after hit. Then, in 2013, Nickelodeon launched an investigation into inappropriate behavior on the set of Sam & Cat after complaints from McCurdy and Grande about a producer on the show, someone with knowledge of the investigation said. They said the investigation concluded that Schneider had contributed to the "toxicity."

McCurdy wrote in her memoir that The Creator was "no longer allowed to be on set with any actors." Two people who worked at Nickelodeon at the time corroborated this to Insider. Russell Hicks, who was Nickelodeon's president of content and production, said Schneider "was the shoulder" young stars "cried on when something happened to them." Hicks added that Schneider "understood what they were going through."

Curdy wrote that The Creator was confined to a "small cave-like room off to the side of the soundstage, surrounded by piles of cold cuts, his favorite snack, and Kids' Choice Awards blimps, his most cherished life accomplishment." An assistant director had to run across the soundstage to give notes, McCurdy wrote, extending shoot days to 17 hours from about 13.

Sam & Cat was canceled in 2014. Schneider went on to create two more shows with Nickelodeon: the tween sitcom Game Shakers and a superhero series called Henry Danger.

But online rumors of Schneider's supposed misdeeds became so widespread in late 2017 and early 2018 that Nickelodeon's parent company, ViacomCBS (now Paramount Global), launched another internal investigation into Schneider's "alleged sexual behavior," someone with knowledge of the investigation told Insider. The investigation found no evidence of sexual misconduct but did conclude Schneider could be verbally abusive. ViacomCBS cut ties with Schneider in 2018. ViacomCBS executives who flew to Los Angeles to tell Schneider the news were anxious he might retaliate, the same person said.

In 2019, Nikolas, who had been speaking out about her negative experiences at Nickelodeon, said she was contacted by a lawyer for Schneider's production company, Schneider's Bakery. The lawyer said he and Schneider would love to have a conversation and reach "an agreement" with her, Nikolas recalled. She said she turned the lawyer down.

"I know for a fact that guy's a creep," Nikolas said she told the lawyer. The person close to Schneider said a representative called Nikolas to tell her that she "could get into legal trouble for making false accusations about someone (in this case, Dan) — even if vague."

Schneider disappeared from the public eye for three years, but he resurfaced in a 2021 Times profile about his absence from children's television. The Times broke the news that Nickelodeon had investigated Schneider in 2018 before cutting ties with him. But many felt that the profile — in which a smiling Schneider, photographed reclining under a tree, teased a comeback, saying he had written and sold a pilot to an unnamed network — read like a puff piece. Liz Feldman, who wrote on "All That" as a teenager and is now the showrunner for Netflix's "Dead to Me," replied to a tweet about the article, writing:

"I worked for Schneider 25 yrs ago. I can confirm inappropriate behavior was happening even then. #metoo."

Feldman declined to speak with Insider about Schneider. Schneider maintains good relationships with many former stars, including Sean Flynn of Zoey 101 and Lisa Foiles of All That. Former Nickelodeon actors say he also remains close with Grande, the most successful of the actors he plucked from obscurity, even attending one of the pop star's concerts in 2019 at her invitation. "I love Dan Schneider," Foiles said. "He is a magic man. I think you can tell when something has had the Dan Schneider touch. He just has this level of comedic timing." Schneider's pilot still hasn't aired. Some who worked with him said it seemed unlikely that any network would hire him after the publication of McCurdy's memoir. He's spent the past year singing the praises of his former stars online, wishing them happy birthday on Facebook, congratulating Leon Thomas of Victorious on making Forbes' 30 Under 30 list, and watching Grande on The Voice. But since the publication of McCurdy's memoir, he's gone dark on social media. He hasn't publicly responded to McCurdy's veiled allegations. Some are optimistic that McCurdy's book will have a domino effect bringing more to light about Schneider and Nickelodeon. Alpert hopes a reexamination of Schneider's behavior draws attention to other "toxic male bosses" who have thrived in Hollywood. She said executives had long let bad behavior slide because so much money was at stake. Nikolas recently held a protest outside Nickelodeon's headquarters calling for the entertainment industry to better protect child actors.

”He's not a good guy," Nikolas said of Schneider, adding that countless kids have trauma because of him. "And Nickelodeon was just letting it happen."

48 notes

·

View notes

Photo

"Tarang" focused mainly on poverty and prostitution. it's about Rodel, a pedicab driver, his wife Aya, a sex worker, and the people that surrounded them. the film showed multiple faces of poverty. one named Klarisse was in jail for robbery. a mother told her daughter, Mariz, that she's beautiful and someday, she will be an artist and will be able to leave that place. Aya, left her child to Judy, daughter of Klarisse and Amir, for awhile for prostitution. she did that inside the pedicab that her husband drives while Rodel just sat on the pavement and waited. one faithful night, a regular customer went to see Rodel. when his wife was not available, the client pointed out to Judy and insisted to have her. Rodel asked for Amir's approval and even if you can feel Amir's hesitation, Judy told his father to accept the Php3000 before the customer change his mind. Amir entrusted Judy to Rodel since it's her first. Rodel initially didn't want to leave Judy, but took another drive due to his customer's insistence to take it as an additional income. back at the community, the movie tackled the fate of some sex workers where they experience violence during their job and was traumatized which happened to Mariz' mom. the climax was slowly built when Mariz saw her mom doing a sexual act for money and Judy's client bumped into the pedicab where she was, hurriedly running away from somewhere. this was also where Mariz' mom finally saw her crying. on his way back, Rodel hurried when he saw an ambulance in the area where he left Judy. Amir was hysterical wanting to see his daughter until they saw the stabbed body of Judy taken out from the alley. he looked around for Rodel and violently punched him in anger on why he left his daughter. Rodel, not once, fought back. the film ended with a bloodied Rodel driving away in his pedicab after he took his family home. it maybe a cliche for indie movies to have prostitution and poverty as its topic. however, the film showed the violence against women with this line of work where some, amidst the trauma, goes back to earn for a living. the illegal became their norm. it's only a matter of time when their kids would also become one. https://www.instagram.com/p/CD8c2MkH6Lg/?igshid=1w9lzwydon8y5

0 notes

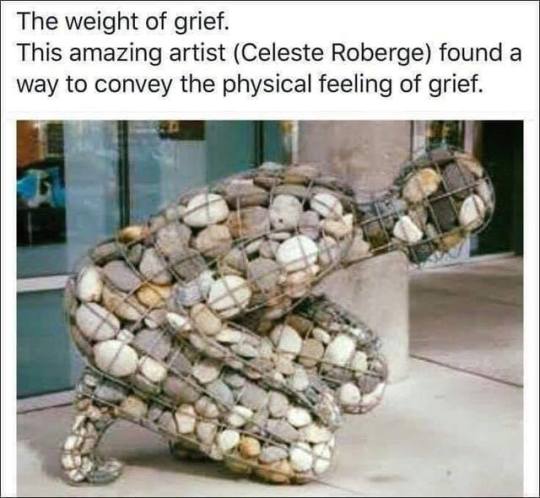

Photo

I never knew this kind of misery could exist until this year. Grief is overwhelming. I can easily say this has been the worst year for my family. Every day I try and give thanks that no one else is dead, or dying (well even that is not true a couple family members not doing so well with their health but they do not have cancer or anything that awful, so I should be grateful right?) I have learned being a better person does not make your life easier. Karma does not exist. My sweet poor baby brother, only 4 years younger than me died in January to start my year off. He would be 22 right now if he would have been alive for his birthday this month. I used to love the rain, now I have mixed feelings. That day I knew something bad was going to happen. I wrote the date two times for various things and got chills each time I wrote it. I watched The Butterfly Effect, which used to be one of my favorite movies until that happened, thinking about how true it was. He passed a semi truck with a car in front of them on that rainy night in January heading west towards the coast, that day it just rained and rained and rained. It was 10PM and dark. I was on the exact same spot on the road 10 minutes before the accident, about 10 miles outside of town. He hydroplaned, rolled and managed to defy physics and come back the other direction and rolled into a telephone pole that hit the drivers side. Completely demolished the car. Passenger was unscathed. He had a pulse for 20 minutes on scene, and was never taken to a hospital at all to even attempt to revive him. Just thrown into a body bag once pulse had stopped... makes me sick to my stomach just thinking about it. At midnight I realized I had 36 missed calls from my mom and step-dad. I was busy arguing with my controlling gas lighting “boyfriend” about tattoos, he was made that I got them. I was thinking someone got pulled over for driving while suspended or something. I never thought about my brother dying, not once my entire life. My mom blubbered “He is dead,” I said “What do you mean?” “He is dead your brother is dead he got in a car wreck” “No it can not be him are you sure?” “Yes I am sure” (can barely understand her both of us just completely blubbering and hysterical now) “How do you know did you see him?” “The police came and told me, his wallet was on him it was his car.” Now having never dealt with death in any way shape or form, not even a distant cousin, I did not know how to react other than scream. I had a slight hope maybe someone stole his car and wallet, because the passenger was not one of his friends I knew, it was someone I had never even heard my brother talk about. But I cried and screamed for days and days and days. The next morning I immediately went out to the crash sight which was right behind my moms house across a big field and put up a cross on the pole. It was still pouring, I had another one drying at home with his name on it. The scene was horrific. They left all of his costs and personal belongings just strung out all over the side of the road.PIECES OF SHIT. After they let him bleed out. Puddles of blood all over the ground in the mud. His car title, personal mail, the coats he had on that night (the passenger posted a photo of them before they left and ten minutes later he was dying) other things he had in his car like work clothes and nails and tools, he was a roofer. He always had those rings of nails everywhere. Just left out like hes worthless trash. The lack of respect for a dead 21 year old kid you did not even take to the hospital...Fucking disgusting. I went out and cleaned everything up. I could not even see my brother until Wednesday, 4 days later. It was a Saturday night when it happened. Towing company would not even let us look at his car until Tuesday. My step-dad, mother and I looked at the car in complete horror. It looked like it been crushed. How the passenger escaped unscathed I really have no idea the entire dashboard was caved in, windshield gone. Blood all over the drivers seat and floor where they just let him lay there and bleed out. Somehow his weed pipe (that was under the passenger seat in a toolbox he was not smoking and he does not drink) was not broken, neither was his phone which was smashed in between the drivers seat and console but it was cracked. We always told each other our passwords in case something like this happened never thinking we would actually have to use it... That day he asked probably 20 people to go all day including his girlfriend, and he could not get anyone to go until 10 o'clock at night when the passenger had said sure I will go. The last thing his girlfriend said to him was “I wish you would go kill yourself”, they had been together for 3 years. I know that when people are arguing they say things like that, I do not hold it against her but its unfortunate she has to live with that being the last thing she said to him. His steering wheel and dashboard were so crushed the keys had to be forcibly removed, I still carry the sideways key around on my key chain because this has made me completely insane, as if I did not struggle enough with depression and anxiety before this from constantly being broke trying to raise a child on my own and never having daycare. That is a story for another day. But this has really fucked me up. He was not a sibling I occasionally see on the holidays, that’s who I called when I really just needed a friend. We went camping and hiking all the time together. We never sat on our phones when we went so we hardly had any pictures together. He was always there for me as a child and an adult, even though I was such a bitch when we were younger. He was always so good to me, the best brother anyone could ever ask for. I hear these people talk about the things their brothers do them, and I am like my brother would have never done that to me... He was such a good person even when people did him wrong. He had a heart of gold and was so unique he had so much potential and was just starting to grow up. Besides my child, there is no other person in the world I loved more than him. I have two other siblings but they are 14 and 11 years younger than me. I love them but I do not share the same bond and he was my only full sibling. When I actually finally got to see him at the morgue (and I was the only family member that even went to see him the rest found it too “traumatizing” I wanted to see what the hell happened) my stomach sank. It was definitely him. My poor little brother, laying on a fucking slab. I just kissed his forehead over and over wishing I could somehow blow the life back into him... I know that can never happen. He will rot in the ground forever. It was just a slight dent on his head under his hair. His beautiful brown hair. You will never convince me he should have not tried to have been saved. I have seen people survive way worse injuries but they were taken to a hospital. They literally just let him lay there until his pulse stopped. I’m too poor to afford an attorney. Just like my grandpa that I never met, but I have been told by my entire family he was beat by a bunch of police officers and left to die in the hospital. My grandmas mom was overdosed in Tylenol at the hospital and her sister died of alcohol poisoning because the hospital would not treat her. Why are the poor just left to die? Because the poor can not afford lawyers, and they know it. I visited him almost every day for the 2 weeks in the morgue, we did not exactly have 5 grand laying around for a funeral so I had to gather some money before the services. I felt awful letting him stay in a morgue that long, but my other choice was cremation which I do not believe in. I wanted it to do it as my native american ancestors did which was bury him outside in a cave but its illegal. I have seen too many cremations where people get the wrong ashes when the DNA test them and I wanted a proper burial, and a place to visit him. We built the casket since I was not paying an additional 5 grand for a wooden box with pillows in it. My stepdad found old redwood on the farm and various other woods to build it with. My brother would have liked it, because he loved to fall trees. He did it for fun almost every time we went to the woods. “Sis, lets go to the woods so I can cut down a tree.” He called me Sis even as an adult. The handles were made out of deer antlers, his first deer that he killed. I bought him a red comforter set because that was his favorite color. I dressed him in his banana pajama pants and his work shirt, because he loved roofing, and one of his cozy flannels. I hope you're cozy brother. Lots of people showed up to the funeral. At least 100 people. My boss and coworker, my brothers coworkers, all my family, even distant family we never really speak to like my grandpas brother. People I did not know. My moms ex husband (my other siblings father) and his parents came. It was a very sad day, watching my grandparents cry as he went into the ground. Everyone took turns getting up to speak. I did as well, but it took so much courage for me to get up there in front of everyone and not bawl and bawl and bawl. I have never seen so many grown men cry in my life until that day. I tried so hard not to bawl but when he went into the ground I lost it, everyone did. We waited until he was buried and smoked a joint on his grave and planted some flowers even though it was freezing and raining and cold. I really did everything I could to make sure he had a proper burial. The celebration of life was a week later, another day we had to put fake smiles on our faces and socialize. What is amazing is how many people it united. But it comes back to The Butterfly Effect, if I would have said hey lets hangout. If I would have been on that road ten minutes later, because I was right fucking there right before it happened. If anyone else would have said they would go and he would have left earlier. Most importantly, if they would have taken him to a hospital and actually tried to do something instead of letting him lay there until his pulse stopped and then throwing him into a body bag. I will never, ever forget him and will never let his legacy die.

0 notes

Text

Brains(Mental health) + Drugs/Medicine

This week in class we had some great and insightful discussions. The topic for the first session was brains where we talked about the history of how the studies of mental health first started. We talked about the effects of war on men where they faced distress, displacement, and death on the battlefield which started the conversation and study of mental health. In the second session, we talked about medicine and the unfair practices of drug companies in the United States.

We started our session by talking about the creation of triage that was close to battlefields to treat soldiers after they were injured. Soldiers felt the need to be close to danger with their brothers still fighting on the battlefield. There is also a shame when soldiers show fear to be in a battlefield when bullets fly past their skull and artillery shells make loud and shocking noises. The major wars forced people in our society to change their mind about the stigma behind mental health. This created an urgency to solve this new upcoming problem that thousands of soldiers started to experience. The mental pressure that soldiers faced on the battlefield and their injury continued to haunt when they came back home. Back during WWI medical professionals weren’t really an expert when it came to mental health. This all changed when society’s young men, who were tough and strong came back broken and sick from the war. The urgency increased to solve the new problem that this new group of men was facing. One of my classmates pointed out that before these major wars, mental health was extremely stigmatized and words like hysterical were used by men to describe women whenever they disagreed about an idea that didn’t seem viable coming from a woman. Trauma now became a major focus because tough men showed symptoms of weakness and that seemed a major problem in society at that time.

Drugs are a major part of the medical field. The invention of medicine has saved billions of lives. Our major focus was when does a drug become something negative and damaging to our society. We define drugs as illegal or legal. Any substance that affects our mind and body is considered a drug. In this blog, I will focus more on legal drugs that are produced for the sole purpose of profit. Patients go to visit a doctor so they can seek treatment and most of the time that patient expects a physical medicine to be prescribed for their pain and discomfort. Our discussion mostly focused on the big pharma companies and how their marketing campaigns have changed society’s view of medicine. Harmful medicine has now become a necessity and without it, we question the doctor’s expertise in our health. The monopoly system of the pharmaceutical companies that exist in the U.S. has only benefitted huge corporations while screwing the general public. The cost for pharmaceutical companies to produce an insulin bottle is only 30 dollars while the cost to buy one is over 300 dollars in the U.S. so this shows how greedy and independent these corporations have become. While doing some research I found more evidence and sources that prove the disgusting agenda of these corporations. In the text Big Pharma's greedy new game, Jim Hightower says, “The public is dismayed and disgusted by the flagrant greed of drugmakers who are shamefully zooming the prices of medicines into the stratosphere, turning necessities into unaffordable luxuries.” Politicians are a huge contributor to this problem as their campaign donations most of the time comprises money from pharmaceutical companies so when they get elected these companies gain more independence. Unless the public becomes more aware of this agenda, society will continue to pay the price behind these greedy corporations.

This week’s open-ended question:

Why did mental health only become important when men faced traumatic situations and started suffering?

Next week we will talk about Death and visit Mount Auburn cemetery.

Additional Sources to help with discussions:

Dolliver, M. (2007, May 28). People think big pharma is shifty-in addition, that is, to being greedy. Adweek, 48, 28. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/212432538?accountid=11311

Hightower, J. (2016, Mar). Big pharma's greedy new game. Colorado Springs Independent Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1775172898?accountid=11311

Kelly, B. (2014). Treating shell shock in returning WWI soldiers. Irish Medical Times, 48(42), 24. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/1649755572?accountid=11311

Lundy, J. (2019, Feb 19). Eveleth man delves into insulin price shock: $40 in canada, $350 in the US. TCA Regional News Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/docview/2183182455?accountid=11311

0 notes

Text

What is amnesia and how is it treated ?

Amnesia is a condition in which a person can no longer memorize or remember information stored in memory. Although it is a popular topic for movies and books, it is a very rare form of discomfort. Being a bit forgetful is completely different from losing memory. Amnesia refers to the loss of large-scale memories that should not be forgotten. These may include important milestones in life, memorable events, key people in life, vital truths that are told or taught.

Amnesia patients have difficulty in remembering the past, memorizing new information and imagining the future. This is to build basic scenarios, recalling the past experiences of patients. The ability to remember events and experiences involves a variety of complex brain processes. When a person gives information to his memory or tries to retrieve information stored in the brain, he may not remember it completely. Most amnesia patients are usually transparent and have a sense of self. However, they may have serious difficulties in learning new information, remembering memories of past experiences, or both. Amnesia types There are many different types of amnesia, and the most common types are as follows: • Anterograde amnesia: The person cannot remember new information, the information that the person has been experiencing recently and that needs to be stored in short term memory is lost, called anterograde amnesia. For example, this can usually result from brain trauma when a person receives a stroke on the head and causes brain damage from it. Therefore, the person remembers the data and events that occurred before the injury. • Retrograde amnesia : In some ways, unlike anterograde amnesia , one cannot remember events that occurred before traumas, but can remember what happened after that, and this is called retrograde amnesia. Although rare, both retrograde and anterograde amnesia may coexist. • Transient global amnesia: Transient global amnesia is the temporary loss of all memory and the difficulty in creating new memories in serious situations. It is also very rare and more likely in older adults with vascular disease. • Traumatic amnesia: Memory loss is caused, for example, by hard knocks in a car accident. The person may experience a brief loss of consciousness or fall into a coma. Amnesia is usually transient, but how long it normally takes may depend on the severity of the injury. • Wernicke Korsakoff's syndrome:In Wernicke Korsakoff's syndrome, long-term alcohol dependence can cause severe memory loss that worsens over time. In addition, the person may have neurological problems such as poor coordination, loss of sensation in the toes and toes, and may result from malnutrition, particularly a lack of thiamine (vitamin B1). • Hysteric (fugue or dissociative) amnesia:Rarely, a person can forget not only his / her past but also his / her identity. They can get out of this situation and suddenly they cannot understand who they are. Even if they look in the mirror, they don't recognize their own reflection. Documents such as driving licenses, credit cards or ID cards are meaningless to the person, and often an event is triggered where the person's mind cannot cope properly. This is called hysterical (fugue or dissociative) amnesia. In addition, people with this type of amnesia often have the ability to recall slowly or suddenly within a few days, but the memory of the shocking event may never be fully restored. • Childhood amnesia: It cannot remember that early childhood events are possible because of a language development problem or some memory regions of the brain that are not fully mature in childhood. This is called childhood amnesia. • Post hypnotic amnesia: It is called post hypnotic amnesia that is not remembered during the hypnotic events. • Source amnesia: In this type of amnesia, a person may remember certain information, but not from where or from whom. • Dimming phenomenon: Consuming large amounts of alcohol may result in memory gaps in which a person does not remember parts of time in a void, which is called a dimming phenomenon. • Prosop amnesia: People with prosop amnesia cannot remember faces they have seen before. In addition, some people may be congenital or later on. Amnesia symptoms

Amnesia is a rare condition and has some symptoms. The symptoms of general amnesia can be listed as follows: • In anterograde amnesia, the ability to learn new information is impaired. • Retrograde amnesia deteriorates the ability to recall past events and previously known information. • False memories may occasionally configure a phenomenon in which false memories may occur. • Uncoordinated movements and tremor indicate neurological problems. • Confusion or disorientation may occur. • There may be problems with short-term memory, partial or total memory loss. • The person may not recognize faces or places. Amnesia is different from dementia, because patients with dementia experience memory loss, but they also experience other important cognitive problems that affect their ability to perform daily activities. Amnesia Reasons Any illness or injury that affects the brain can affect memory, and the memory function operates many different parts of the brain at the same time. Damage to the brain structures that make up the limbic system such as the hippocampus and thalamus can cause amnesia, and the limbic system controls emotions and memories. Medical Amnesia Amnesia caused by brain damage or damage. Some of the possible causes of medical amnesia are: • Stroke • Encephalitis and inflammation of the brain due to a bacterial or viral infection or an autoimmune reaction • Celiac disease may be associated with confusion and personality changes. • Oxygen deprivation may occur, for example, as a result of a heart attack, breathing difficulties or carbon monoxide poisoning • Some medications such as sleeping pills • Subarachnoid hemorrhage or bleeding in the area between the skull and the brain • Brain tumor affecting part of the brain • Some seizure disorders • Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), or shock treatment, psychiatric treatment for therapeutic effect is induced seizures can cause temporary memory loss • head injuries that can lead to memory loss and is usually temporary ones

It Is Good For Your Heart Health Nuts

Psychological Amnesia Psychological amnesia, also known as dissociative amnesia, is caused by many emotional shock. Some of these emotional shocks are: • A violent crime • Sexual or other abuse • Military warfare • Natural disasters • Terrorist action Unbearable living conditions leading to serious psychological stress and internal conflict can lead to some degree of amnesia. The psychological stressor tends to disrupt personal, historical memories, rather than intervening in revealing new memories. Amnesia Diagnostic

A physician will need to rule out other possible causes of memory loss, such as dementia, Alzheimer's disease, depression, or a brain tumor. A detailed medical history is taken, which may be difficult for the patient to remember, and may include family members or carers. The patient's permission is required to talk to the doctor about his / her medical details. Some questions to ask about the patient's medical details are as follows: • Can the patient remember recent events and events? • When did memory problems begin? • How did it develop? • Are there any factors that cause memory loss, such as head injury, surgery, or stroke? • Is there any neurological or psychiatric condition or family history? • Does the person consume alcohol? • Is he taking any medication? • Has he used illegal drugs such as cocaine or heroin? • Do the symptoms undermine their ability to care for themselves? • Is there a history of depression or seizures? • Have you ever had cancer? A physical examination may check the brain and nervous system, for example: • Reflexes • Sensory function • Balance The doctor may also examine the patient: • Judgment • Short-term memory • Long-term memory Memory assessment helps determine the degree of memory loss, which will help to find the best treatment. The doctor may require an MRI, CAT scan or an electroencephalogram (EEG) to find out if there is any physical damage or brain abnormality. In addition, blood tests can reveal the presence of any infection or nutritional deficiency. Amnesia Treatment

In most cases, amnesia spontaneously resolves without treatment. However, if there is an underlying physical or mental disorder, treatment may be necessary. Psychotherapy can also help some patients, and hypnosis is an effective way of remembering forgotten memories. In these cases family support is very important and photos, scents and music can help. Treatment usually includes techniques and strategies that help to compensate for the memory problem. Some of these techniques and strategies include: • Working with a professional therapist to obtain new information to replace lost memories, to obtain new memories, and to use existing ones. • Learn strategies for organizing information and facilitate storage. • Helping with daily tasks and identifying important events, when to take medication, and so on. Use digital helpers like smartphones to remind you. A contact list with facial photos can help. There is currently no medication to restore memory lost due to amnesia. Malnutrition or Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome may include memory loss due to thiamine (vitamin B1) deficiency, so targeted and necessary nutrition may help. In addition, whole grain cereals, legumes (beans and lentils), nuts, lean meat and yeast are rich sources of thiamine. Bibliography: sciencedirect.com ncbi.nlm.nih.gov memorylossonline.com journals.lww.com rarediseases.info.nih.go jamanetwork.com Read the full article

#amnesia#amnesiadefinition#AmnesiaReasons#Amnesiasymptoms#AmnesiaTreatment#Amnesiatypes#Anterogradeamnesia#MedicalAmnesia#PsychologicalAmnesia#Whatisamnesiaandhowisittreated

0 notes

Photo

New Post has been published on https://fitnesshealthyoga.com/yoga-meditation-and-psychedelics-would-you-take-drugs-during-your-practice/

Yoga, Meditation and Psychedelics: Would you Take Drugs During Your Practice?

Top yoga and meditation teachers Sally Kempton and Ram Dass share their personal experiences with psychedelics as we explore the latest trends in research and recreational use.

ANDREW BANNECKER

When a friend invited Maya Griffin* to a “journey weekend”—two or three days spent taking psychedelics in hopes of experiencing profound insights or a spiritual awakening—she found herself considering it. “Drugs were never on my radar,” says Griffin, 39, of New York City. “At an early age, I got warnings from my parents that drugs may have played a role in bringing on a family member’s mental illness. Beyond trying pot a couple times in college, I didn’t touch them.” But then Griffin met Julia Miller* in a yoga class, and after about a year of friendship, Miller began sharing tales from her annual psychedelic weekends. She’d travel with friends to rental houses in various parts of the United States where a “medicine man” from California would join them and administer mushrooms, LSD, and other psychedelics. Miller would tell Griffin about experiences on these “medicines��� that had helped her feel connected to the divine. She’d talk about being in meditative-like bliss states and feeling pure love.

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

Thanks for watching!Visit Website

This time, Miller was hosting a three-day journey weekend with several psychedelics—such as DMT (dimethyltryptamine, a compound found in plants that’s extracted and then smoked to produce a powerful experience that’s over in minutes), LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide, or “acid,” which is chemically synthesized from a fungus), and Ayahuasca (a brew that blends whole plants containing DMT with those that have enzyme inhibitors that prolong the DMT experience). Miller described it as a “choose your own adventure” weekend, where Griffin could opt in or out of various drugs as she pleased. Griffin eventually decided to go for it. Miller recommended she first do a “mini journey”—just one day and one drug—to get a sense of what it would be like and to see if a longer trip was really something she wanted to do. So, a couple of months before the official journey, Griffin took a mini journey with magic mushrooms.

See also This is the Reason I Take the Subway 45 Minutes Uptown to Work Out—Even Though There’s a Gym On My Block

“It felt really intentional. We honored the spirits of the four directions beforehand, a tradition among indigenous cultures, and asked the ancestors to keep us safe,” she says. “I spent a lot of time feeling heavy, lying on the couch at first. Then, everything around me looked more vibrant and colorful. I was laughing hysterically with a friend. Time was warped. At the end, I got what my friends would call a ‘download,’ or the kind of insight you might get during meditation. It felt spiritual in a way. I wasn’t in a relationship at the time and I found myself having this sense that I needed to carve out space for a partner in my life. It was sweet and lovely.”

Griffin, who’s practiced yoga for more than 20 years and who says she wanted to try psychedelics in order to “pull back the ‘veil of perception,’” is among a new class of yoga practitioners who are giving drugs a try for spiritual reasons. They’re embarking on journey weekends, doing psychedelics in meditation circles, and taking the substances during art and music festivals to feel connected to a larger community and purpose. But a renewed interest in these explorations, and the mystical experiences they produce, isn’t confined to recreational settings. Psychedelics, primarily psilocybin, a psychoactive compound in magic mushrooms, are being studied by scientists, psychiatrists, and psychologists again after a decades-long hiatus following the experimental 1960s—a time when horror stories of recreational use gone wrong contributed to bans on the drugs and harsh punishments for anyone caught with them. This led to the shutdown of all studies into potential therapeutic uses, until recently. (The drugs are still illegal outside of clinical trials.)

Another Trip with Psychedelics

The freeze on psychedelics research was lifted in the early 1990s with Food and Drug Administration approval for a small pilot study on DMT, but it took another decade before studies of psychedelics began to pick up. Researchers are taking another look at drugs that alter consciousness, both to explore their potential role as a novel treatment for a variety of psychiatric or behavioral disorders and to study the effects that drug-induced mystical experiences may have on a healthy person’s life—and brain. “When I entered medical school in 1975, the topic of psychedelics was off the board. It was kind of a taboo area,” says Charles Grob, MD, a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, who conducted a 2011 pilot study on the use of psilocybin to treat anxiety in patients with terminal cancer. Now researchers such as Grob are following up on the treatment models developed in the ’50s and ’60s, especially for patients who don’t respond well to conventional therapies.

See also 6 Yoga Retreats to Help You Deal With Addiction

This opening of the vault—research has also picked up again in countries such as England, Spain, and Switzerland—has one big difference from studies done decades ago: Researchers use stringent controls and methods that have since become the norm (the older studies relied mostly on anecdotal accounts and observations that occurred under varying conditions). These days, scientists are also utilizing modern neuroimaging machines to get a glimpse into what happens in the brain. The results are preliminary but seem promising and suggest that just one or two doses of a psychedelic may be helpful in treating addictions (such as to cigarettes or alcohol), treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety in patients with terminal cancer. “It’s not about the drug per se, it’s about the meaningful experience that one dose can generate,” says Anthony Bossis, PhD, a clinical assistant professor of psychiatry at New York University School of Medicine who conducted a 2016 study on the use of psilocybin for patients with cancer who were struggling with anxiety, depression, and existential distress (fear of ceasing to exist).

Spiritual experiences in particular are showing up in research summaries. The term “psychedelic” was coined by a British-Canadian psychiatrist during the 1950s and is a mashup of two ancient Greek words that together mean “mind revealing.” Psychedelics are also known as hallucinogens, although they don’t always produce hallucinations, and as entheogens, or substances that generate the divine. In the pilot study looking at the effects of DMT on healthy volunteers, University of New Mexico School of Medicine researchers summarized the typical participant experience as “more vivid and compelling than dreams or waking awareness.” In a study published in 2006 in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine gave a relatively high dose (30 mg) of psilocybin to healthy volunteers who’d never previously taken a hallucinogen and found that it could reliably evoke a mystical-type experience with substantial personal meaning for participants. About 70 percent of participants rated the psilocybin session as among the top five most spiritually significant experiences of their lives. In addition, the participants reported positive changes in mood and attitude about life and self—which persisted at a 14-month follow-up. Interestingly, core factors researchers used in determining whether a study participant had a mystical-type experience, also known as a peak experience or a spiritual epiphany, was their report of a sense of “unity” and “transcendence of time and space.” (See “What’s a Mystical Experience?” section below for the full list of how experts define one.)

In psilocybin studies for cancer distress, the patients who reported having a mystical experience while on the drug also scored higher in their reports of post-session benefits. “For people who are potentially dying of cancer, the ability to have a mystical experience where they describe experiencing self-transcendence and no longer solely identifying with their bodies is a profound gift,” says Bossis, also a clinical psychologist with a speciality in palliative care and a long interest in comparative religions. He describes his research as the study of “the scientific and the sacred.” In 2016 he published his findings on psilocybin for cancer patients in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, showing that a single psilocybin session led to improvement in anxiety and depression, a decrease in cancer-related demoralization and hopelessness, improved spiritual well-being, and increased quality of life—both immediately afterward and at a six-and-a-half-month follow-up. A study from Johns Hopkins produced similar results the same year. “The drug is out of your system in a matter of hours, but the memories and changes from the experience are often long-lasting,” Bossis says.

Learn if psychedelics complement a yoga practice or promote healing.

ANDREW BANNECKER

The Science of Spirituality

In addition to studying psilocybin-assisted therapy for cancer patients, Bossis is director of the NYU Psilocybin Religious Leaders Project (a sister project at Johns Hopkins is also in progress), which is recruiting religious leaders from different lineages—Christian clergy, Jewish rabbis, Zen Buddhist roshis, Hindu priests, and Muslim imams—and giving them high-dose psilocybin in order to study their accounts of the sessions and any effects the experience has on their spiritual practices. “They’re helping us describe the nature of the experience given their unique training and vernacular,” says Bossis, who adds that it’s too early to share results. The religious-leaders study is a new-wave version of the famous Good Friday Experiment at Boston University’s Marsh Chapel, conducted in 1962 by psychiatrist and minister Walter Pahnke. Pahnke was working on a PhD in religion and society at Harvard University and his experiment was overseen by members of the Department of Psychology, including psychologist Timothy Leary, who’d later become a notorious figure in the counterculture movement, and psychologist Richard Alpert, who’d later return from India as Ram Dass and introduce a generation to bhakti yoga and meditation. Pahnke wanted to explore whether using psychedelics in a religious setting could invoke a profound mystical experience, so at a Good Friday service his team gave 20 divinity students a capsule of either psilocybin or an active placebo, niacin. At least 8 of the 10 students who took the mushrooms reported a powerful mystical experience, compared to 1 of 10 in the control group. While the study was later criticized for failing to report an adverse event—a tranquilizer was administered to a distressed participant who left the chapel and refused to return—it was the first double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment with psychedelics. It also helped establish the terms “set” and “setting,” commonly used by researchers and recreational users alike. Set is the intention you bring to a psychedelic experience, and setting is the environment in which you take it.

“Set and setting are really critical in determining a positive outcome,” UCLA’s Grob says. “Optimizing set prepares an individual and helps them fully understand the range of effects they might have with a substance. It asks patients what their intention is and what they hope to get out of their experience. Setting is maintaining a safe and secure environment and having someone there who will adequately and responsibly monitor you.”

Bossis says most patients in the cancer studies set intentions for the session related to a better death or end of life—a sense of integrity, dignity, and resolution. Bossis encourages them to accept and directly face whatever is unfolding on psilocybin, even if it’s dark imagery or feelings of death, as is often the case for these study participants. “As counterintuitive as it sounds, I tell them to move into thoughts or experiences of dying—to go ahead. They won’t die physically, of course; it’s an experience of ego death and transcendence,” he says. “By moving into it, you’re directly learning from it and it typically changes to an insightful outcome. Avoiding it can only fuel it and makes it worse.”

In the research studies, the setting is a room in a medical center that’s made to look more like a living room. Participants lie on a couch, wear an eye mask and headphones (listening to mostly classical and instrumental music), and receive encouragement from their therapists to, for example, “go inward and accept the rise and fall of the experience.” Therapists are mostly quiet. They are there to monitor patients and assist them if they experience anything difficult or frightening, or simply want to talk.

“Even in clinical situations, the psychedelic really runs itself,” says Ram Dass, who is now 87 and lives in Maui. “I’m happy to see that this has been opened up and these researchers are doing their work from a legal place.”

The Shadow Side and How to Shift It

While all of this may sound enticing, psychedelic experiences may not be so reliably enlightening or helpful (or legal) when done recreationally, especially at a young age. Documentary filmmaker and rock musician Ben Stewart, who hosts the series Psychedelica on Gaia.com, describes his experiences using psychedelics, including mushrooms and LSD, as a teen as “pushing the boundaries in a juvenile way.” He says, “I wasn’t in a sacred place or even a place where I was respecting the power of the plant. I was just doing it whenever, and I had extremely terrifying experiences.” Years later in his films and research projects he started hearing about set and setting. “They’d say to bring an intention or ask a question and keep revisiting it throughout the journey. I was always given something more beautiful even if it took me to a dark place.”

Brigitte Mars, a professor of herbal medicine at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, teaches a “sacred psychoactives” class that covers the ceremonial use of psychedelics in ancient Greece, in Native American traditions, and as part of the shamanic path. “In a lot of indigenous cultures, young people had rites of passage in which they might be taken aside by a shaman and given a psychedelic plant or be told to go spend the night on a mountaintop. When they returned to the tribe, they’d be given more privileges since they’d gone through an initiation,” she says. Mars says LSD and mushrooms combined with prayer and intention helped put her on a path of healthy eating and yoga at a young age, and she strives to educate students about using psychedelics in a more responsible way, should they opt to partake in them. “This is definitely not supposed to be about going to a concert and getting as far out as possible. It can be an opportunity for growth and rebirth and to recalibrate your life. It’s a special occasion,” she says, adding, “psychedelics aren’t for everyone, and they aren’t a substitute for working on yourself.”

See also 4 Energy-Boosting Mushrooms (And How to Cook Them)

Tara Brach, PhD, a psychologist and the founder of Insight Meditation Community of Washington, DC, says she sees great healing potential for psychedelics, especially when paired with meditation and in clinical settings, but she warns about the risk of spiritual bypassing—using spiritual practices as a way to avoid dealing with difficult psychological issues that need attention and healing: “Mystical experience can be seductive. For some it creates the sense that this is the ‘fast track,’ and now that they’ve experienced mystical states, attention to communication, deep self-inquiry, or therapy and other forms of somatic healing are not necessary to grow.” She also says that recreational users don’t always give the attention to setting that’s needed to feel safe and uplifted. “Environments filled with noise and light pollution, distractions, and potentially insensitive and disturbing human interactions will not serve our well-being,” she says.

As these drugs edge their way back into contemporary pop culture, researchers warn about the medical and psychological dangers of recreational use, especially when it involves the mixing of two or more substances, including alcohol. “We had a wild degree of misuse and abuse in the ’60s, particularly among young people who were not adequately prepared and would take them under all sorts of adverse conditions,” Grob says. “These are very serious medicines that should only be taken for the most serious of purposes. I also think we need to learn from the anthropologic record about how to utilize these compounds in a safe manner. It wasn’t for entertainment, recreation, or sensation. It was to further strengthen an individual’s identity as part of his culture and society, and it facilitated greater social cohesion.”

Learn about the pyschedelic roots of yoga.

ANDREW BANNECKER

Yoga’s Psychedelic Roots

Anthropologists have discovered mushroom iconography in churches throughout the world. And some scholars make the case that psychoactive plants may have played a role in the early days of yoga tradition. The Rig Veda and the Upanishads (sacred Indian texts) describe a drink called soma (extract) or amrita (nectar of immortality) that led to spiritual visions. “It’s documented that yogis were essentially utilizing some brew, some concoction, to elicit states of transcendental awareness,” say Tias Little, a yoga teacher and founder of Prajna Yoga school in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He also points to Yoga Sutra 4.1, in which Patanjali mentions that paranormal attainments can be obtained through herbs and mantra.

“Psychotropic substances are powerful tools, and like all tools, they can cut both ways—helping or harming,” says Ganga White, author of Yoga Beyond Belief and MultiDimensional Yoga and founder of White Lotus Foundation in Santa Barbara, California. “If you look at anything you can see positive and negative uses. A medicine can be a poison and a poison can be a medicine—there’s a saying like this in the Bhagavad Gita.”

White’s first experience with psychedelics was at age 20. It was 1967 and he took LSD. “I was an engineering student servicing TVs and working on electronics. The next day I became a yogi,” he says. “I saw the life force in plants and the magnitude of beauty in nature. It set me on a spiritual path.” That year he started going to talks by a professor of comparative religion who told him that a teacher from India in the Sivananda lineage had come to the United States. White went to study with him, and he would later make trips to India to learn from other teachers. As his yoga practice deepened, White stopped using psychedelics. His first yoga teachers were adamantly anti-drug. “I was told that they would destroy your chakras and your astral body. I stopped everything, even coffee and tea,” he says. But within a decade, White began shifting his view on psychedelics again. He says he started to notice “duplicity, hypocrisy, and spiritual materialism” in the yoga world. And he no longer felt that psychedelic experiences were “analog to true experiences.” He started combining meditation and psychedelics. “I think an occasional mystic journey is a tune-up,” he says. “It’s like going to see a great teacher once in a while who always has new lessons.”

See also Chakra Tune-Up: Intro to the Muladhara

Meditation teacher Sally Kempton, author of Meditation for the Love of It, shares the sentiment. She says it was her use of psychedelics during the ’60s that served as a catalyst for her meditation practice and studies in the tantric tradition. “Everyone from my generation who had an awakening pretty much had it on a psychedelic. We didn’t have yoga studios yet,” she says. “I had my first awakening on acid. It was wildly dramatic because I was really innocent and had hardly done any spiritual reading. Having that experience of ‘everything is love’ was totally revelatory. When I began meditating, it was essentially for the purpose of getting my mind to become clear enough so that I could find that place that I knew was the truth, which I knew was love.” Kempton says she’s done LSD and Ayahuasca within the past decade for “psychological journeying,” which she describes as “looking into issues I find uncomfortable or that I’m trying to break through and understand.”

Little tried mushrooms and LSD at around age 20 and says he didn’t have any mystical experiences, yet he feels that they contributed to his openness in exploring meditation, literature, poetry, and music. “I was experimenting as a young person and there were a number of forces shifting my own sense of self-identity and self-worth. I landed on meditation as a way to sustain a kind of open awareness,” he says, noting that psychedelics are no longer part of his sadhana (spiritual path).

Going Beyond the Veil

After her first psychedelic experience on psilocybin, Griffin decided to join her friends for a journey weekend. On offer Friday night were “Rumi Blast” (a derivative of DMT) and “Sassafras,” which is similar to MDMA (Methylenedioxymethamphetamine, known colloquially as ecstasy or Molly). Saturday was LSD. Sunday was Ayahuasca. “Once I was there, I felt really open to the experience. It felt really safe and intentional—almost like the start of a yoga retreat,” she says. It began by smudging with sage and palo santo. After the ceremonial opening, Griffin inhaled the Rumi Blast. “I was lying down and couldn’t move my body but felt like a vibration was buzzing through me,” she says. After about five minutes—the length of a typical peak on DMT—she sat up abruptly. “I took a massive deep breath and it felt like remembrance of my first breath. It was so visceral.” Next up was Sassafras: “It ushered in love. We played music and danced and saw each other as beautiful souls.” Griffin originally planned to end the journey here, but after having such a connected experience the previously night, she decided to try LSD. “It was a hyper-color world. Plants and tables were moving. At one point I started sobbing and I felt like I was crying for the world. Two minutes felt like two hours,” she says. Exhausted and mentally tapped by Sunday, she opted out of the Ayahuasca tea. Reflecting on it now, she says, “The experiences will never leave me. Now when I look at a tree, it isn’t undulating or dancing like when I was on LSD, but I ask myself, ‘What am I not seeing that’s still there?’”

See also This 6-Minute Sound Bath Is About to Change Your Day for the Better

The Chemical Structure of Psychedelics

It was actually the psychedelic research of the 1950s that contributed to our understanding of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which regulates mood, happiness, social behavior, and more. Most of the classic psychedelics are serotonin agonists, meaning they activate serotonin receptors. (What’s actually happening during this activation is mostly unknown.)

Classic psychedelics are broken into two groups of organic compounds called alkaloids. One group is the tryptamines, which have a similar chemical structure to serotonin. The other group, the phenethylamines, are more chemically similar to dopamine, which regulates attention, learning, and emotional responses. Phenethylamines have effects on both dopamine and serotonin neurotransmitter systems. DMT (found in plants but also in trace amounts in animals), psilocybin, and LSD are tryptamines. Mescaline (derived from cacti, including peyote and San Pedro) is a phenethylamine. MDMA, originally developed by a pharmaceutical company, is also a phenethylamine, but scientists don’t classify it as a classic psychedelic because of its stimulant effects and “empathogenic” qualities that help a user bond with others. The classics, whether they come straight from nature (plant teas, whole mushrooms) or are semi-synthetic forms created in a lab (LSD tabs, psilocybin capsules), are catalysts for more inwardly focused personal experiences.

See also Try This Durga-Inspired Guided Meditation for Strength

“Classic psychedelics are physiologically well tolerated—with the exception of vomiting and diarrhea on Ayahuasca,” says Grob, who also studied Ayahuasca in Brazil during the 1990s. “But psychologically there are serious risks, particularly for people with underlying psychiatric conditions or a family history of major mental illness like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.” Psychedelics can cause fear, anxiety, or paranoia—which often resolves fairly quickly in the right set and setting, Grob says, but can escalate or lead to injuries in other scenarios. In extremely rare but terrifying cases, chronic psychosis, post-traumatic stress from a bad experience, or hallucinogen persisting perception disorder—ongoing visual disturbances, or “flashbacks”—can occur. (There have been no reports of any such problems in modern clinical trials with rigorous screening processes and controlled dosage and support.) Unlike the classic psychedelics, MDMA has serious cardiac risks in high doses and raises body temperature, which has led to cases of people overheating at music festivals and clubs. There’s also always the risk of adverse drug interactions. For example, combining Ayahuasca with SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) used to treat depression can lead to serotonin syndrome, which can cause a rise in body temperature and disorientation.

Learn how your brain is affected by drugs and meditation.

ANDREW BANNECKER

Your Brain on Drugs—and Meditation

Flora Baker, 30, a travel blogger from London, took Ayahuasca while visiting Brazil and the psychoactive cactus San Pedro while in Bolivia. “Part of the reason I was traveling in South America was an attempt to heal after the death of my mother. The ceremonies involved a lot of introspective thought about who I was without her, and what kind of woman I was becoming,” she says. “On Ayahuasca, my thoughts about my mom weren’t of her physical form, but her energy—as a spirit or life force that carried me and carries me onward, always, ever present within me and around. I’ve thought of these ideas in the past, but it was the first time I truly believed and understood them.” The experiences ended with a sense of peace and acceptance, and Baker says she’s sometimes able to access these same feelings in her daily meditation practice.

See also 10 Best Yoga and Meditation Books, According to 10 Top Yoga and Meditation Teachers

Baker’s and Griffin’s comparisons of certain insights or feelings they had on psychedelics to those one might get through meditation may have an explanation in modern neuroscience. To start, in a study of what happens in the brain during a psychedelic experience, researchers at Imperial College London gave participants psilocybin and scanned their brains. They found decreased activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex. These are key brain regions involved in the “default mode network,” or the brain circuits that help you maintain a sense of self and daydream. The researchers also found that reduced activity in default mode networks correlated with participants’ reports of “ego dissolution.”

When Judson Brewer, MD, PhD, then a researcher at Yale University, read the study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2012, he noticed that the brain scans looked strikingly similar to those of meditators in a study he’d published two months earlier in the same journal. In Brewer’s study, he’d put experienced meditators with more than a decade of practice into an fMRI machine, asked them to meditate, and found that the regions of the volunteers’ brains that tended to quiet down were also the medial prefrontal and posterior cingulate cortexes. (In the Yale study, meditators who were new to the practice did not show the same reductions.) Brewer, who is now director of research and innovation at Brown University’s Mindfulness Center, describes the default mode network as the “me network.” Activity spikes when you are thinking about something you need to do in the future, or when you’re ruminating over past regrets. “Deactivations in these brain regions line up with a selfless sense that people get. They let go of fears and protections and taking things personally. When that expands way, way out there, you lose a sense of where you end and where the rest of the world begins.”

Intrigued by the similarities in brain scans between people taking psychedelics and meditators, other researchers have started investigating whether the two practices might be complementary in clinical settings. In a study published last year in the Journal of Psychopharmacology, Johns Hopkins researchers took 75 people with little or no history of meditation and broke them into three groups. Those in the first group received a very low dose of psilocybin (1 mg) and were asked to commit to regular spiritual practices such as meditation, spiritual awareness practice, and journaling with just five hours of support. The second group got high-dose psilocybin (20–30 mg) and five hours of support, and the third group got high-dose psilocybin and 35 hours of support. After six months, both high-dose groups reported more-frequent spiritual practices and more gratitude than those in the low-dose group. In addition, those in the high-dose and high-support group reported higher ratings in finding meaning and sacredness in daily life.

Johns Hopkins is also researching the effects of psilocybin sessions on long-term meditators. Those with a lifetime average of about 5,800 hours of meditation, or roughly the equivalent of meditating an hour a day for 16 years, were, after careful preparations, given psilocybin, put in an fMRI machine, and asked to meditate. Psychologist Brach and her husband, Jonathan Foust, cofounder of the Meditation Teacher Training Institute in Washington, DC, and former president of the Kripalu Center for Yoga & Health, helped recruit volunteers for the study, and Foust participated in a preliminary stage. While on psilocybin, he did regular short periods of concentration practice, compassion practice, and open-awareness practice. He also spontaneously experienced an intense childhood memory.

“My brother is four years older than me. In the competition for our parents’ affection, attention, and love, he hated my guts. This is normal and natural, but I saw how I subconsciously took that message in and it informed my life. On psilocybin I simultaneously experienced the raw wounded feeling and an empathy and insight into where he was coming from,” Foust says. “During the height of the experience, they asked me how much negative emotion I was feeling on a scale of 1 to 10 and I said 10. Then, they asked about positive emotion and well-being and I said 10. It was kind of a soul-expanding insight that it’s possible to have consciousness so wide that it can hold the suffering and the bliss of the world.”

See also YJ Tried It: 30 Days of Guided Sleep Meditation

Foust started meditating at the age of 15 and he’s maintained a daily practice since then, including a couple of decades spent living in an ashram participating in intensive monthlong meditation retreats. “My meditation practice gave me some steadiness through all the waves of sensation and mood I was experiencing on psilocybin,” he says. “There were some artificial elements to it, but I came away with a much deeper trust in the essential liberation teachings in the Buddhist tradition. It verified my faith in all these practices that I’ve been doing my whole life.” Since the psilocybin study, he describes his meditation practice as “not as serious or grim,” and reflecting on this shift, he says, “I think my practice on some subtle level was informed by a desire to feel better, or to help me solve a problem, and I actually feel there is now more a sense of ease. I’m savoring my practice more and enjoying it more.”

Frederick Barrett, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins, presented preliminary findings with the long-term meditators and said that participants reported decreased mental effort and increased vividness when meditating. The meditators who reported having a mystical experience during the psilocybin-meditation had an accompanying acute drop in their default mode network.

Robin Carhart-Harris, PhD, head of psychedelic research at Imperial College London, has an “entropy hypothesis” for what happens in your brain on psychedelics. His theory is that as activity in your default mode network goes down, other regions of your brain, such as those responsible for feelings and memories, are able to communicate with one another much more openly and in a way that’s less predictable and more anarchical (entropy). What this all means is yet to be determined, but researchers speculate that when your default mode network comes back to full functionality, the new pathways forged during the psychedelic experience can help shift you into new patterns of thinking.

To Journey or Not to Journey?