#unit 11 devising performance work

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"The Omers." From the Acts of the Apostles 7: 44-46.

Housing God became a big issue for the lost Israelites in the Desert of Paran. They were and still are homeless themselves but the concept of a House for God was still paramount. The instructions for building the Temple no matter where or when a Jewish person resides is detailed within the Torah. I have devised it is a floor plan for a kind of mandala, a map of how the Torah itself and its stochastic progression work. The variables are far too complicated to perform the model manually but here is the overview:

The Tabernacle, From Vayakhel:

8 All those who were skilled among the workers made the tabernacle with ten curtains of finely twisted linen and blue, purple and scarlet yarn, with cherubim woven into them by expert hands. 9 All the curtains were the same size—twenty-eight cubits long and four cubits wide.[b]10 They joined five of the curtains together and did the same with the other five. 11 Then they made loops of blue material along the edge of the end curtain in one set, and the same was done with the end curtain in the other set. 12 They also made fifty loops on one curtain and fifty loops on the end curtain of the other set, with the loops opposite each other. 13 Then they made fifty gold clasps and used them to fasten the two sets of curtains together so that the tabernacle was a unit.

14 They made curtains of goat hair for the tent over the tabernacle—eleven altogether. 15 All eleven curtains were the same size—thirty cubits long and four cubits wide.[c]16 They joined five of the curtains into one set and the other six into another set. 17 Then they made fifty loops along the edge of the end curtain in one set and also along the edge of the end curtain in the other set. 18 They made fifty bronze clasps to fasten the tent together as a unit. 19 Then they made for the tent a covering of ram skins dyed red, and over that a covering of the other durable leather.[d]

20 They made upright frames of acacia wood for the tabernacle. 21 Each frame was ten cubits long and a cubit and a half wide,[e]22 with two projections set parallel to each other. They made all the frames of the tabernacle in this way. 23 They made twenty frames for the south side of the tabernacle 24 and made forty silver bases to go under them—two bases for each frame, one under each projection. 25 For the other side, the north side of the tabernacle, they made twenty frames 26 and forty silver bases—two under each frame. 27 They made six frames for the far end, that is, the west end of the tabernacle, 28 and two frames were made for the corners of the tabernacle at the far end. 29 At these two corners the frames were double from the bottom all the way to the top and fitted into a single ring; both were made alike. 30 So there were eight frames and sixteen silver bases—two under each frame.

31 They also made crossbars of acacia wood: five for the frames on one side of the tabernacle, 32 five for those on the other side, and five for the frames on the west, at the far end of the tabernacle. 33 They made the center crossbar so that it extended from end to end at the middle of the frames. 34 They overlaid the frames with gold and made gold rings to hold the crossbars. They also overlaid the crossbars with gold.

35 They made the curtain of blue, purple and scarlet yarn and finely twisted linen, with cherubim woven into it by a skilled worker. 36 They made four posts of acacia wood for it and overlaid them with gold. They made gold hooks for them and cast their four silver bases.

37 For the entrance to the tent they made a curtain of blue, purple and scarlet yarn and finely twisted linen—the work of an embroiderer; 38 and they made five posts with hooks for them. They overlaid the tops of the posts and their bands with gold and made their five bases of bronze. = The five books of the Torah, one for each finger, together they create the Hand of God called the Yod.

=

-> Each of these elements in the Temple and their materials symbolize the making of the Man of God.

The Ten Purple Curtains woven with Cherubim- they protect the senses from idolatry. Each sense has two eyes and two ears and two nostrils, two mouths with two tongues in it. The Curtains produce the darkness that empties them of all that propaganda and bullshit from Egypt, prevents their re-entry.

There are 10 of these, the same number as the nodes on the Kabbalah.

The “blue material and “gold clasps” unites the senses; are 50 precepts in the Torah called Omers that keep the person "coupled" after dipping twice (see below). The fifty Omers prevent a return to slavery after one is freed.

Blue and Gold, are the sky and the sun, and these represent the activities of God as He said let there be light and made a vault, remember God wanted to Vault things together and yet be able to discern them.

Leather and Goat Hair Curtains: over the internal lattice work of the mind and its intuition comes skin and hair, and these are also supposed to be Vaulted together with a sentient self-concept.

I THINK there are eleven of these because the 11th character in the Hebrew alphabet symbolizes life- there are ten faculties and One Supreme Intelligence = all living things, but man especially covered in skin and hair and the Crown.

Bronze Loops signify the Law which binds living things together, similar to how the Gold of the Sun binds life to the sky.

Twenty Frames/Forty Silver Bases etc.

Pure silver, is the most powerful conductor of heat, electricity and most importantly to our discussions of Torah, has the most reflectivity. There are suggestions that the 40 silver bases are the same as 40 days or forty years, “time, not place” frames the House of God,

But really, truly, the number adds up to the # of Parshiot, which is 54:

20 frames N

20 frames S

then 6 west

And two frames were made for the corners of the tabernacle at the far end. 29 At these two corners the frames were double=

46+ 8 = 54.

Crossbars of Gold: I am pretty sure these are Rabbis, the learned ones.

The Final Curtain: the work of the Embroiderer is either a Magus, or a King who unites the rest within the Temple aka the Kingdom.

Luke explains the role these "field exercises" play in making of a Home For God and a resting place for the people of the Kingdom of Israel:

44 “Our ancestors had the Tent of God's presence with them in the desert. It had been made as God had told Moses to make it, according to the pattern that Moses had been shown.

45 Later on, our ancestors who received the tent from their fathers carried it with them when they went with Joshua and took over the land from the nations that God drove out as they advanced. And it stayed there until the time of David.

46 He won God's favor and asked God to allow him to provide a dwelling place for the God of Jacob.[b] 47 But it was Solomon who built him a house.

To understand all of this one needs to be literate with the Book of Joshua which explains the purposes of the Torah Circuit. I have created an English copy here. Joshua states after we Cross Over, have plans for the future that reflect one's adult mature Self, then one has what one needs to find a home. Home, according to Joshua is the experience of Shabbat without end. All one needs is a little love squeeze and one shall be ready.

Lukes explanation of how to hand Joshua's tent over to David, the second to the last tage "persistent beloved beauty" is followed by the conlusion, called Solomon, "A Basket of Peace." Each of these Jewish national identities are "driven out" by God as the population matures into its studies of Judaism, like a horse race drives horses to the finals at the Pan Pacific Grand Prix.

We simply can't have people dancing their own steps. This is why God drives.

The Values in Gematria are:

v. 44: Our ancestors had the tent of God. The Number is 6857, סחןז, sahenz, "the miracle." Anyone who knows what God is and why He gave us this massive math problem to solve knows why His help is a miracle. We would still be living in shit without Him.

v. 45: Later on they carried it with them. The Number is 14841, ידףםא, jodpam, "integrity."

"The verb תמם (tamam) means to be complete, finished, ethically sound or upright. Nouns תם (tom) and תמה (tumma) mean integrity or completeness. Adjective תם (tam) means complete or perfect, sound or wholesome, or morally integer (Job 1:8). Adjective תמים (tamim) means complete or whole, or sound or having integrity. Noun מתם (metom) means entirety or soundness."

v. 46: We won God's favor. The Number is 9994, ץיץץד, tshitzatzad, Tzachi Tzad, "win a step." The winning step is Step 9, yagaati, "We touched."

The final Gemara is סחןזידףםא ץיץץד, schanizidephema tshitzatzad, schenzidfam a tsitztsd,

"That which is alive dip them twice and win a step."

The entire purpose of the Temple and its incarnations and serial manifestations all pertain to the completion of the Passover Seder, during which we "dip twice."

Dipping twice is a bizarre way of saying one has to perform the Seder as written and again using one's intuition. It begins, "In wisdom and factiousness, connect wisdom with the mouth. Let us hope to show grace and intelligence."

Persons who profess the Seder and then "go out" according to God will experience good lives.

It concludes, "May God pay attention to this place, may we not waste time."

Dipping twice then is "you have to spend time not to waste it. "

0 notes

Photo

Asta Nielsen (11 September 1881 – 24 May 1972), she was one of the more transcendent stars of the 1910s. With her fame crossing from Europe to the United States, in a time where that was rarely done. She was one of the many who marked a dramatic turn in how acting occurred on film. In the early days of cinema, there was a large swath of actors who had made their living as theater performers. They carried their experiences onto the screen, leading to somewhat exaggerated performances at the worst of times. It wasn’t until stars such as Nielsen or Lillian Gish came along that a more reserved style of acting took over. By then, directors such as Maurice Tourneur or Albert Capellani called for naturalism in film, which Nielsen was able to provide.

Right from the very beginning, Nielsen made a name for herself. When she starred as Magda Vang in ‘The Abyss’ (1910), her minimalistic acting style garnered acclaim across Denmark. Although her acting in the film as a young, naïve person who is lured into a tragic life was exceptional, it is the eroticism from the Gaucho Dance scene that brought attention over seas. Before ‘The Abyss’ could be shown in theaters in the United States it needed to be heavily edited, something that would become a trend in her films over the years.

After the immense popularity of, ‘The Abyss,’ Nielsen moved with her husband, screenwriter and director Urban Gad, to Germany where they founded the Internationale Film-Vertriebs-Gesellschaft with Paul Davidson. While in Germany, Nielsen’s popularity hit an all-time high, she was simply known as Die Asta (The Asta). In 1914, she had an annual fee of 85,000 marks. Paul Davidson is quoted as saying:

‘I had not been thinking about film production. But then I saw the first Asta Nielsen film. I realized that the age of short film was past. And above all I realized that this woman was the first artist in the medium of film. Asta Nielsen, I instantly felt could be a global success. It was international film sales that provided Union with eight Nielsen films per year. I built her a studio in Tempelhof, and set up a big production staff around her. This woman can carry it. Let the films cost whatever they cost. I used every available means – and devised many new ones – in order to bring the Asta Nielsen films to the world.’

In 1911 she was voted the world’s top female star by a Russian poll.

In 1921 she acted in what was at the time, a radical interpretation of ‘Hamlet,’ where she played the titular character, a woman disguising herself as a man. This was done because in Prologue, the Queen of Denmark gives birth to a girl and shortly thereafter hears her husband has been killed in battle. Knowing only a male heir can claim the throne, she announces that she gave birth to a boy, named Hamlet. The New York Times would go onto rank it as one of the top ten films of that year, citing her performance as one of the main reasons why.

Neilson worked the remainder of her career in Germany, finishing out her acting career in 1932 with ‘A Crown of Thorns,’ her lone Talkie. It wasn’t that she lacked the passion to continue acting, it was just by the time Talkies came along there came with them a whole new generation of actors who had perfected the style Neilson had helped innovate. She did return to the stage for a brief period. However, with the rise of the Nazi’s, there came an increased demand for propaganda, and one afternoon, Neilson was offered her own studio by Joseph Goebbles. When she declined, she was invited to tea with Hitler, who tried to show her how much sway she could have with the German people.

Neilson again declined. Understanding the situation she was in, she left for Denmark. While there she wrote articles about art, acting and began work on her autobiography.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

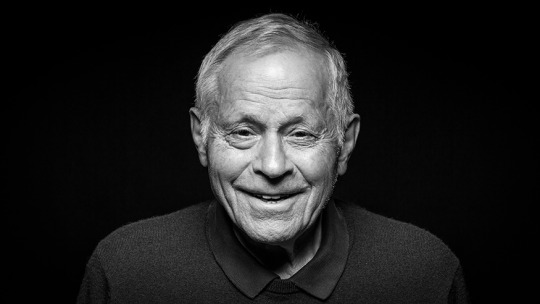

We Worked on Apollo

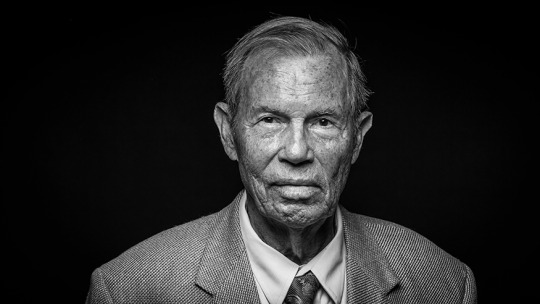

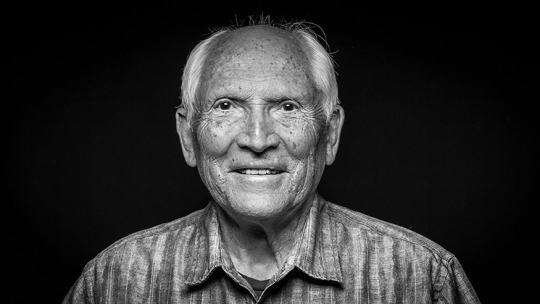

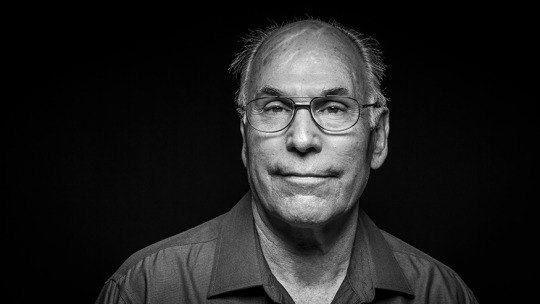

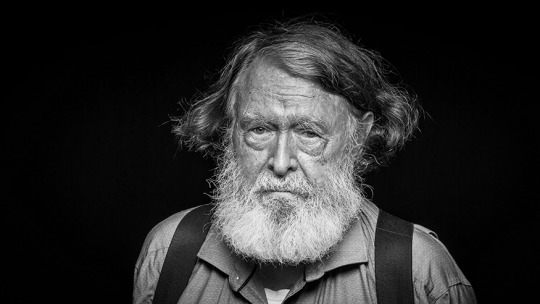

On July 20, 1969, the world watched as Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took their first steps on the Moon. It was a historic moment for the United States and for humanity. Until then, no human had ever walked on another world. To achieve this remarkable feat, we recruited the best and brightest scientists, engineers and mathematicians across the country. At the peak of our Apollo program, an estimated 400,000 Americans of diverse race and ethnicity worked to realize President John F. Kennedy’s vision of landing humans on the Moon and bringing them safely back to Earth. The men and women of our Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley supported the Apollo program in numerous ways – from devising the shape of the Apollo space capsule to performing tests on its thermal protection system and study of the Moon rocks and soils collected by the astronauts. In celebration of the upcoming 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing, here are portraits of some of the people who worked at Ames in the 1960s to help make the Apollo program a success.

“I knew Neil Armstrong. I had a young daughter and she took her first step on the day that Neil stepped foot on the Moon. Isn’t that something?”

Hank Cole did research on the design of the Saturn V rocket, which propelled humans to the Moon. An engineer, his work at Ames often took him to Edwards Air Force Base in Southern California, where he met Neil Armstrong and other pilots who tested experimental aircraft.

“I worked in a lab analyzing Apollo 11 lunar dust samples for microbes. We wore protective clothing from head to toe, taking extreme care not to contaminate the samples.”

Caye Johnson came to Ames in 1964. A biologist, she analyzed samples taken by Apollo astronauts from the Moon for signs of life. Although no life was found in these samples, the methodology paved the way for later work in astrobiology and the search for life on Mars.

“I investigated a system that could be used to provide guidance and control of the Saturn V rocket in the event of a failure during launch. It was very exciting and challenging work.”

Richard Kurkowski started work at Ames in 1955, when the center was still part of the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics, NASA’s predecessor. An engineer, he performed wind tunnel tests on aircraft prior to his work on the Apollo program.

“I was 24 and doing some of the first computer programming work on the Apollo heat shield. When we landed on the Moon it was just surreal. I was very proud. I was in awe.”

Mike Green started at Ames in 1965 as a computer programmer. He supported aerospace engineers working on the development of the thermal protection system for the Apollo command module. The programs were executed on some of earliest large-scale computers available at that time.

“In 1963 there was alarm that the Apollo heat shield would not be able to protect the astronauts. We checked and found it would work as designed. Sure enough, the astronauts made it home safely!”

Gerhard Hahne played an important role in certifying that the Apollo spacecraft heat shield used to bring our astronauts home from the Moon would not fail. The Apollo command module was the first crewed spacecraft designed to enter the atmosphere of Earth at lunar-return velocity – approximately 24,000 mph, or more than 30 times faster than the speed of sound.

“I was struck by the beauty of the photo of Earth rising above the stark desert of the lunar surface. It made me realize how frail our planet is in the vastness of space.”

Jim Arnold arrived at Ames in 1962 and was hired to work on studying the aerothermodynamics of the Apollo spacecraft. He was amazed by the image captured by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders from lunar orbit on Christmas Eve in 1968 of Earth rising from beneath the Moon’s horizon. The stunning picture would later become known as the iconic Earthrise photo.

“When the spacecraft returned to Earth safely and intact everyone was overjoyed. But I knew it wasn’t going to fail.”

Howard Goldstein came to Ames in 1967. An engineer, he tested materials used for the Apollo capsule heat shield, which protected the three-man crew against the blistering heat of reentry into Earth’s atmosphere on the return trip from the Moon.

“I was in Houston waiting to study the first lunar samples. It was very exciting to be there when the astronauts walked from the mobile quarantine facility into the building.”

Richard Johnson developed a simple instrument to analyze the total organic carbon content of the soil samples collected by Apollo astronauts from the Moon’s surface. He and his wife Caye Johnson, who is also a scientist, were at our Lunar Receiving Laboratory in Houston when the Apollo 11 astronauts returned to Earth so they could examine the samples immediately upon their arrival.

“I tested extreme atmospheric entries for the Apollo heat shield. Teamwork and dedication produced success.”

William Borucki joined Ames in 1962. He collected data on the radiation environment of the Apollo heat shield in a facility used to simulate the reentry of the Apollo spacecraft into Earth’s atmosphere.

Join us in celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 Moon landing and hear about our future plans to go forward to the Moon and on to Mars by tuning in to a special two-hour live NASA Television broadcast at 1 pm ET on July 19. Watch the program at www.nasa.gov/live.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

4K notes

·

View notes

Note

Tell me about ur ocs

Okay okay I have been WAITING for someone to ask me this. I hope you’re ready for an onslaught anon!

okay so since you didn’t ask for a specific set or certain oc, imma tell you about my main oc’s, the prime 16!

the prime 16 are a class of super-powered individuals living in a post-apocalypse, and under the gaze of the institute they live in. that is, until they run away and make lives of their own! Their main goal is to regroup in Boston, but many decide to take the scenic route around the broken country. Here they are, from oldest to youngest and in order of class:

Class Alpha: the first class to emerge, they are the strongest and most skilled with their abilities. They’ve been in the clutches of the institute longer than any of the others, and their need for escape lets them find freedom.

1: Marlon, the soul scholar. He is the oldest and was the one to devise the escape plan in the first place. He escaped and went straight to Boston, using his power of elemental construction to research into soul power, making him a useful asset to anyone. However, his need for knowledge doesn’t stop there. He goes searching and looking where no one has or should, and finds himself deep into something he never should have disturbed.

2: Charlie, the shadow spy. She is the second-in-command to Marlon, but prefers to stay out of the limelight. She finds herself in the holographic city of Chicago, and finds that the best places for her are in the dark corners of the streets. She uses her ability intuition to become a valuable spy and mercenary, able to take out or find anything she is hired to find. She finds though that the shadows she saw as her ally can hold more secrets than she could ever want to know.

3: Colby, the glam American. Colby is a lot more easygoing than most of the others in his class, and is able to mutate his genes however he likes. He uses this skill to join a rock band and become a roving sensation across the ruined country. He finds that not everyone just wants to listen though, and that there will be people who may just want to use him for themselves.

4: Lydia, the lucky bullet. She’s the most energetic of class Alpha and has herself a cartoon physiology, making life around her a living cartoon. She moves off to the west to become a famed cowboy, and is beloved by the people around her. However, all cartoons have their run, and Lydia is terrified of when she will run out of luck.

Class Beta: the second best, the afterthought, whatever you call them, class Beta has heard it before. They have powers that are less useful in battle and more with other people, or in life. They are constantly played as Alpha’s little siblings (which they are) to an insane degree, leading them to often resent or idolize the higher class.

5: Kit, the lonesome nomad. He was one of the kids headed for Boston, until a tragic accident landed him on the road. His only goal is to try and make it to Boston with his brothers and sisters in one piece, and he will betray and manipulate anyone with his empath abilities to get there. He is cold and untrusting, but soon finds that self-isolation is an even colder fate.

6: Georgina, the traveling psychic. She has the power of divination, and can see the future. But it’s not the most reliable very often, only showing flashes and bits of voices. However, she manages to use her powers to go from some local psychic of a small town to a traveling performer, telling peoples’ futures far and wide.

7: Samuel, the bloodthirsty knight. He is the second most resentful of class Alpha, mostly stemming from his own inferiority complex from his power, action link. Meaning he can’t be a powerhouse on his own. However, when he escapes, he is let out into a war zone. He works his way up and becomes a soldier, soon earning his title through the bloodshed at one of his most famed battles. But his winning streak can only last so long, and he’ll have to find that out the hard way.

8: Sarah, the starry oceanographer. She is the most resentful of class Alpha, and ironically the first to reach Boston. She becomes an acclaimed sailor with her navigational intuition, and with her help ships stop disappearing into the shifting oceans forever. However, she soon finds out the hard way that there are depths too deep for even her to reach.

Class Gamma: the less put-together class, they escaped at a younger age and have less of a kinship with each other. The only thing that unites them in the slightest is their common childhood trauma.

9: Jordan, the reaper’s seeker. He is young and impressionable, but his path was set for him the moment the accidentally used his power, intuitive aptitude, to find a hidden tumor in his adoptive mother. From there he is seen as an omen of evil to many, but is used as a tool to find the issues in many for others. He wants it to end so badly, but in what way is up to him.

10: Robin, the false herald. Robin finds herself sent to a religious academy for her safekeeping, but in the process uses her power of possession to accidentally call down their god through her. She is revered as a saint and is given special treatment, but due to her identity as the herald, she never gets to find an identity of her own, which is what she wants more than anything.

11: Archie, the human pandemic. Archie’s goal was to try and reunite with his family, but the moment he first contracted the first viruses, he knew that would be impossible. He has the power of invincibility, meaning that the viruses in his body won’t hurt him, but they will hurt anyone else who comes in contact with him. He now wanders the woods alone, hoping that someone will come along and help him. But in the meantime, he has friendship with the other things living on him.

12: Adrianna, the nether queen. After separation from the rest of the prime 16, she finds herself running from raiders and police, until she comes across the entrance to an underground realm full of people that soon forcibly crowns her as queen of the underground after she kills the last one on arrival. However, Adrianna wants nothing to do with the affairs of the underground and longs for escape, and with her indomitable will, she’ll make sure of it.

Class Delta: the youngest of the prime 16, they have little to no memory of the institute. Because of this, they have no practice with their powers and have had their fates completely thrown to the wind, making them the hardest to find of the group.

13: Archie, the calamity child. He has lived his life jumping from one adoptive family to another, and tragedy seems to follow him no matter where he goes. From hurricanes to tornadoes and flash floods, Archie has always been the only one to remain with his botanical abomination power. He has ended up getting bad rep, with people blaming his power for his bad luck. He ends up becoming disconnected from other kids and mistrustful of adults, but just wants a family of his own.

14: Maya, the gateway girl. She was raised in the complexes of downtown New York, and with her friends is constantly braving the dangers of the uptown ruins. Maya’s own power, domain, is only known between her and her own friends. Not even her ‘parents’ know about it. However, she’s forced to face herself and confront her past when she finds how similar her power is to to the monsters living uptown, and finds some shocking truths.

15: Xavier, the griefer king. He was found by the real king as a baby, and after finding out about his power, animalistic abomination, he wholeheartedly adopts the boy as his own. Xavier is raised among the other griefers as one of them, but is abruptly put in charge when the king must go on a journey to expand west. He becomes a ruthless leaver, unafraid to go to violent measures, and finds himself reveling in the hunting of unknowing travelers on the highway. But Xavier soon needs to find the balance of human and animal, lest he finds himself going off the deep end.

16: Adeline, the sacrifice. The youngest and rumored to be the most powerful, Adeline lived her life peacefully without her power ever awakening. However, the truth came to her abruptly and soon uprooted her whole life, and was told that she must become a vessel to save the world. In the stress of everything moving and her whole life crumbling in front of her though, her power awakens, and everyone finds what makes her the most powerful of them all…

and that is the prime 16! Hope you like them, and don’t be afraid to send questions if you want!

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best Movies Of The Year 1980 - Top 20 Films Of 1980

What Are The Best Movies Of The Year 1980?

From New York to Los Angeles this is a question that will get a different answer from every person you ask. There were some great films in the 1980s, and 1980 started the decade off with a bang as a year full of innovation in every way throughout all of society, and it was the start of some exciting new techniques, technologies, and ideas in the film industry in particular with many movies from the year 1980 introducing revolutionary and pioneering cinematic visions. Many people think that some of the best 80s movies of the decade came out in 1980. In this article post, we will go through our top picks for the 20 best movies of 1980, you might be surprised to find out which movies made it on the list! 1) Kramer vs. Kramer In 1980, "Kramer vs. Kramer" was released and became a huge success at the box office. The movie starred Meryl Streep as Joanna Kramer, Dustin Hoffman as Ted Kramer, Jane Alexander as Marylin Jaffe-Jenson, and Justin Henry as Billy Kramer. This film won five Academy Awards in 1981 including Best Picture of 1979 or 1980. It also received nominations for best director (Robert Benton), best actor (Dustin Hoffman), and best-adapted screenplay based on another work (Erica Mann). It is now considered one of the most significant Hollywood films ever made about divorce because it provides nuance to both sides of an argument. 2) The Shining This iconic horror classic film directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring Jack Nicholson and Shelley Duvall was released in 1980. It is based on Stephen King's 1977 novel of the same name. The film has been ranked a number of times as one of the best horror movies ever made and is now considered to be one of Kubrick's best films. It was nominated for two Academy Awards (Best Actor in Leading Role--Jack Nicholson) and won none at the time. The Shining also received nominations for Best Director - Stanley Kubrick), Best Adapted Screenplay--Steven Spielberg/Stanley Kubrick). Its reputation grew over time, eventually earning an Oscar nomination for Best Picture. 3) Being There Hal Ashby himself had been nominated for an Academy Award in 1971 with directing The Last Detail. It is a film that could be classified as both comedy and drama, but the emphasis on this 1980 release lies more on its comedic aspects. While it was not one of the most acclaimed films when it came out, many now consider Being There to be a classic film about society's relationship with television at the time. It offers commentary on economic inequality and how people are often reduced to simple archetypes who can easily fit into neat narratives for consumption purposes. 4) Time Bandits Time Bandits, a 1980 British fantasy film about adventure, was co-written by Terry Gilliam. It stars Sean Connery and John Cleese as well as Shelley Duvall and Ralph Richardson. Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm. Peter Vaughan and David Warner are also featured. It is a whimsical kids' movie with the fantasy adventure of time travel that has been ranked as one of the best movies ever made by many critics. Gilliam has referred to time bandits as first in his "Trilogy of Imagination", which includes Brazil (1985), and then The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (88). They all revolve around the "craziness and incoherence of our society, and the desire for escape through every means. These films all focus on the struggles and attempts to escape through imagination. Brazil is seen through the eyes of a young man, Time Bandits through a child's eyes, and Munchausen through an old man's eyes. Time Bandits, in particular, was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects. 5) Pennies from Heaven Quite a departure from his previous work, this film is much more lighthearted and comedic than the serious dramas of The Miracle Worker or Bonnie and Clyde. The plot revolves around Arthur Parker (Steve Martin), whose life becomes increasingly chaotic as he tries to juggle two jobs, an impending child custody battle for his daughter, and a demanding girlfriend who wants him to give up one job so that they can have some time together. 6) Airplane! This Leslie Nielsen instant comedy classic was one of the highest-grossing movies of 1980. The movie is about an airplane crew that must find a way to land their plane after food poisoning breaks out on board and the pilots become incapacitated, with only two inexperienced passengers who happen to be a doctor (Robert Hays) and a flight attendant (Julie Hagerty) qualified to land the plane. Airplane! was one of the most successful films at theaters in 1980 It had more than $83 million worth of ticket sales by year's end - it became one of Leslie Nielsen's most popular roles ever The film also helped launch Robert Hays' career as a leading man, though he later found greater success playing comedic supporting characters before retiring from acting. 7) The Empire Strikes Back One of the most famous of the 1980s movies, The Empire Strikes Back is remembered for its numerous plot twists and turns as well as introducing fan-favorite Yoda The film features Mark Hamill reprising his role as Luke Skywalker in this second installment of George Lucas' Star Wars series and it was the first star wars to be released on VHS. Featuring a mixture of live-action footage with high-quality animation from Japanese company Toho, it became one of the best critically acclaimed movies ever. In 1997, it won an American Film Institute award for being among the top 100 films since 1941. 8) Raging Bull 1980 was a strong year for movies, and Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull is one of the most acclaimed action films to be released that year. It stars Robert De Niro in an Academy Award-winning performance as new york boxer Jake La Motta, who has a turbulent affair with Kim Basinger's Vickie. The film depicts how new york boxing served as both his escape from domestic abuse but also led him on a self-destruction path. In addition to being nominated for ten Oscars (including best picture), it won two including best actor for Robert de Niro and best director awards respectively. Released by United Artists, the movie has ranked among the top 100 American Films ever made according to AFI rankings. This release is considered one of the best films of the 80s by many critics. 9) Kagemusha One of the most interesting and well-made movies that 1980 has to offer, Kagemusha tells the story of a warlord who is critically injured and after being buried alive. The movie was directed by Akira Kurosawa and stars Tatsuya Nakadai in one of his best performances ever as both warrior leader Katsuyori Shibata and an imposter named Shingen Yashida. Released in Japan on April 20th, 1980, it became the second-highest-grossing film at the Japanese box office just behind The Return of Godzilla (1984). Kagemusha made its international debut at Cannes Film Festival's Directors Fortnight where it won two major awards: Special Jury Prize for Best Direction and Grand Prix du Festival International du Film - Art. 10) The Gods Must Be Crazy Part comedy, part drama, The Gods Must Be Crazy is a timeless classic. Released in 1980, the film follows Xi (N!xau), an out-of-touch bushman who lives happily with his family until he encounters Coca Cola for the first time and it changes their world forever. The premise of this movie makes us laugh because we can relate to how much more comfortable life was before modern society became so intricate that things like Coke began infiltrating every aspect of our lives. We're drawn into Xi's story as he goes from living peacefully with his tribe to being thrust into a completely different reality when they start hunting down any remaining cases of coca-cola at stores all over town! It also touches on some deeper themes such as the cultural modern world where his customs and rituals mean nothing. Xi's journey is our own as we watch the culture clash of modern society, with all its good intentions and never-ending thirst for new things to consume, come into contact with a simpler time that has long since passed by. The humorous film release was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film but lost out to Italy’s Cinema Paradiso (1988). 11) Caddyshack Released in 1980 this classic comedy film by Harold Ramis is widely considered one of the funniest movies ever made by fans and critics alike. It features an amazing comedic all-star ensemble cast, including Chevy Chase as a rich playboy who turns caddie in order to get girls; Ted Knight as Judge Smails, who wants to keep his country club memberships exclusive and prestigious; Rodney Dangerfield as Ty Webb, a millionaire golfer-cum-caddy who has been banned from all other golf courses for being too good. Also featuring Bill Murray as Carl Spackler, the groundskeeper at Bushwood Country Club whose only goal seems to be killing off gophers with any weapon he can devise (including explosives); Michael O'Keefe as Danny Noonan, a young man hired by Judge Smails's daughter (Castle) to caddy for him; and Brian Doyle-Murray as Lou Loomis, the club's ultra-snobby head professional. 12) The Blues Brothers Another instant classic 1980 movie, The Blues Brothers are best known for its 1980 car chases. Starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd as Joliet Jake & Elwood Blues respectively, the two brothers who perform a blues show before being arrested by police. They break out of jail with their friends to save an orphanage from foreclosure through satanic cult leader sheik Abdul Khadaffi's "Elvis-Is-King" rally in Chicago Illinois on Mothers Day 1980 at noon. The film has been praised by audiences and critics alike for its music, screenplay, and performances but criticized for its lack of character development (most likely due to budget constraints). This was even acknowledged during production when director John Landis told cast members not to act too much because "no one is going to see this movie." The 1980 car chases are iconic and highly regarded by film critics. One of the most memorable moments in 1980 was when Elwood Blues while driving his 1980 Chevy Malibu, spots a cat on the front fender as he's being chased by police officers from Illinois State Troopers who try to arrest him for not wearing seat belts (the law at that time). The chase ends with Jake & Elwood crashing into an old man sitting atop a 1980 Chevy Monte Carlo. After striking them, the cops then swerve quickly around their fallen comrade before continuing after our heroes. 13) 9 To 5 9 to 5 (listed in the opening credits as Nine to Five) is a 1980 American comedy film directed by Colin Higgins, who wrote the screenplay with Patricia Resnick. It stars Jane Fonda, Lily Tomlin, and Dolly Parton as three working women who live out their fantasies of getting even with and overthrowing the company's autocratic, "sexist, egotistical, lying, hypocritical bigot" boss, played by Dabney Coleman. The film grossed over $103.9 million and is the 20th-highest-grossing comedy film. As a star vehicle for Parton—already established as a successful singer, musician, and songwriter—it launched her permanently into mainstream popular culture. A television series of the same name based on the film ran for five seasons, and a musical version of the film (also titled 9 to 5), with new songs written by Parton, opened on Broadway on April 30, 2009. 9 to 5 is number 74 on the American Film Institute's "100 Funniest Movies" and has an 83% approval rating on the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes. 14) Smokey And The Bandit 2 Smokey and the Bandit 2 Is a 1980 American action comedy film directed by Hal Needham, starring Burt Reynolds, Sally Field, Jerry Reed, Jackie Gleason, And Dom DeLuise. This film is a sequel to 1977's film Smokey and the Bandit. The original release of the film was in the United Kingdom, New Zealand, and Australia. Bo "Bandit", Darville (Burt Reynolds), and Cledus "Snowman," Snow (Jerry Reed) transport an elephant to the GOP National Convention. Sheriff Buford T. Justice, Jackie Gleason (Jackie Gleason), is once more in hot pursuit. 15) Superman 2 Superman II, a 1980 superhero movie directed by Richard Lester, is written by Mario Puzo, David, and Leslie Newman and is based on a story by Puzo about the DC Comics character Superman. It features Gene Hackman and Terence Stamp, Terence Stamp, Ned Beatty, and Sarah Douglas. The film was first released in Australia and Europe on December 4, 1980. It was also released in other countries during 1981. Megasound is a high-impact surround sound system that's similar to Sensurround and was used for select premiere Superman II engagements. The Salkinds decided in 1977 that they would simultaneously film Superman and its sequel. Principal photography began in March 1977 and ended in October 1978. There were tensions between Richard Donner, the original director, and the producers. It was decided to stop filming the sequel (of which 75 percent was already completed) and instead finish the first film. After the December 1978 release of Superman, Donner was fired from his post as director and was replaced by Lester. Many cast members and crew members declined to return following Donner's firing. Lester was officially acknowledged as the director. Principal photography resumed in September 1979 and ended in March 1980. Film critics gave the film positive reviews, praising the performances of Reeve, Stamp, and Hackman as well as the visual effects and humor. The film grossed $190million against a $54 million production budget. 16) Friday The 13th Friday the 13th, 1980 American slasher movie, is directed and produced by Sean S. Cunningham. Written by Victor Miller, it stars Betsy Palmer and Adrienne King. The plot centers on a group of teenager camp counselors, who are each murdered by an unknown killer as they attempt to reopen an abandoned summer camp. Cunningham, inspired by John Carpenter's Halloween (1978) success, put out an advertisement in Variety to sell the film. Miller was still writing the screenplay. Filming began in New York City after casting the film. It was shot in New Jersey during summer 1979 on an estimated budget of $550,000. The finished film was the subject of a bidding war. Paramount Pictures won domestic distribution rights while Warner Bros. Pictures took European rights. Friday the 13th, which was released on May 9, 1980, was a huge box office hit, earning $59.8 million globally. The film received mixed reviews, some praised its cinematography, score, and performances while others criticized it for depicting graphic violence. It was the first independent film of its type to be distributed in the U.S. by major studios. The film's box office success led it to many sequels, a crossover film with A Nightmare on Elm Street, and a reboot of the series in 2009. 17) Flash Gordon Flash Gordon is a 1980 space opera film directed and produced by Mike Hodges. It was based on Alex Raymond's King Features comic strip. The film stars Sam J. Jones and Melody Anderson as well as Max von Sydow, Max von Sydow, Max von Sydow, and Topol. Topol is supported by Timothy Dalton and Mariangela Melato. Peter Wyngarde plays the role of Peter Wyngarde. The film features Flash Gordon (Jones), a star quarterback, and his friends Dale Arden and Hans Zarkov (Topol), as they unify the warring factions on the planet Mongo to resist the oppression by Ming the Merciless (von Sydow), a man who wants to destroy Earth. Producer Dino De Laurentiis had been involved in two comic book adaptations: Danger: Diabolik and Barbarella (both 1968). He had also previously worked on Danger. De Laurentiis declined a George Lucas directorial offer, a Star Wars version directed by Federico Fellini was also rejected. De Laurentiis hired Nicolas Roeg as director and Enter the Dragon writer Michael Allin as the lead developer on the film. They were replaced in 1977 by Lorenzo Semple Jr. and Hodges, who had written De Laurentiis’ remake of King Kong, this was due to Roeg's dissatisfaction. Flash Gordon was mostly shot in England, with several soundstages at Elstree Studios and Shepperton Studios. It uses a camp style that is similar to the 1960s TV series Batman, which Semple created. Jones quit the film before principal photography was overdue to a dispute between De Laurentiis and Jones. Much of Jones's dialogue was dubbed by Peter Marinker. The documentary Life After Flash examines the main subjects of Jones' departure and his career after it was released. It is known for its Queen-inspired musical score, which features orchestral sections by Howard Blake. Flash Gordon was a box-office success in Italy and the United Kingdom, but it did poorly in other markets. The film received generally positive reviews upon its initial release and has since developed a large cult following. There have been many attempts at sequels or reboots, but none of them have ever made it to production. 18) Cheech & Chong's Next Movie Cheech and Chong's Next Movie, a 1980 comedy film by Tommy Chong, is the second feature-length Cheech & Chong project, after Up in Smoke. It was released by Universal Pictures. Cheech and Chong go on a mission: siphon gasoline to their neighbor's car. They then continue their day. Cheech works at a movie theater, while Chong looks for something to smoke (a roach). Then Chong revs up his indoor motorcycle and plays loud rock music that disrupts the neighborhood. Cheech is fired and the couple goes to Donna, Cheech's girlfriend, and welfare officer. Cheech seduces Donna over her objections and gets her in trouble with her boss. 19) Coal Miner's Daughter Coal Miner's Daughter, a 1980 American musical biographical film, was directed by Michael Apted and based on a screenplay by Tom Rickman. The film follows Loretta Lynn's rise to stardom as a country singer, starting in her teen years with a poor family. The film is based on Lynn's 1976 biography by George Vecsey. Read the full article

#BestFilmsOf1980#BestMoviesOfTheYear1980#BestMoviesOfTheYear1980-Top20FilmsOf1980#movies1980#Top20FilmsOf1980

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

• Fu-Go Balloon Bomb

A Fu-Go, or fire balloon (風船爆弾, fūsen bakudan, lit. "balloon bomb"), was a weapon launched by Japan during World War II.

The fūsen bakudan campaign was the most earnest of the attacks. The concept was the brainchild of the Imperial Japanese Army's Ninth Army's Number Nine Research Laboratory, under Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, with work performed by Technical Major Teiji Takada and his colleagues. The balloons were intended to make use of a strong current of winter air that the Japanese had discovered flowing at high altitude and speed over their country, which later became known as the jet stream. The jet stream reported by Wasaburo Oishi blew at altitudes above 30,000 ft (9.1 km) and could carry a large balloon across the Pacific in three days, over a distance of more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km). Such balloons could carry incendiary and high-explosive bombs to the United States and drop them there to kill people, destroy buildings, and start forest fires. The preparations were lengthy because the technological problems were acute. A hydrogen balloon expands when warmed by the sunlight, and rises; then it contracts when cooled at night, and descends. The engineers devised a control system driven by an altimeter to discard ballast. When the balloon descended below 30,000 ft (9.1 km), it electrically fired a charge to cut loose sandbags. The sandbags were carried on a cast-aluminium four-spoked wheel and discarded two at a time to keep the wheel balanced. Similarly, when the balloon rose above about 38,000 feet (12 km), the altimeter activated a valve to vent hydrogen. The hydrogen was also vented if the balloon's pressure reached a critical level.

The control system ran the balloon through three days of flight. By that time, it was likely over the U.S., and its ballast was expended. The final flash of gunpowder released the bombs, also carried on the wheel, and lit a 64 feet (20 meters) long fuse that hung from the balloon's equator. After 84 minutes, the fuse fired a flash bomb that destroyed the balloon. The balloon had to carry about 1,001 pounds (454 kg) of gear. At first the balloons were made of conventional rubberized silk, but improved envelopes had less leakage. An order went out for ten thousand balloons made of "washi", a paper derived from mulberry bushes that was impermeable and very tough. It was only available in squares about the size of a road map, so it was glued together in three or four laminations using edible konnyaku (devil's tongue) paste – though hungry workers stealing the paste for food created some problems. Many workers were nimble-fingered teenaged school girls.

The bombs most commonly carried by the balloons were, Type 92 33-pound (15 kg) high-explosive bomb consisting of 9.5 pounds (4.3 kg) picric acid or TNT surrounded by 26 steel rings within a steel casing 4 inches (10 cm) in diameter and 14.5 inches (37 cm) long and welded to a 11-inch (28 cm) tail fin assembly. Type 97 26-pound (12 kg) thermite incendiary bomb using the Type 92 bomb casing and fin assembly containing 11 ounces (310 g) of gunpowder and three 3.3-pound (1.5 kg) magnesium containers of thermite. 11-pound (5.0 kg) thermite incendiary bomb consisting of a 3.75-inch (9.5 cm) steel tube 15.75 inches (40.0 cm) long containing thermite with an ignition charge of magnesium, potassium nitrate and barium peroxide.

A balloon launch organization of three battalions was formed. The first battalion included headquarters and three squadrons totaling 1,500 men in Ibaraki Prefecture with nine launch stations at Ōtsu. The second battalion of 700 men in three squadrons operated six launch stations at Ichinomiya, Chiba; and the third battalion of 600 men in two squadrons operated six launch stations at Nakoso in Fukushima Prefecture. The Ōtsu site included hydrogen gas generating facilities, but the 2nd and 3rd battalion launch sites used hydrogen manufactured elsewhere. The best time to launch was just after the passing of a high-pressure front, and wind conditions were most suitable for several hours prior to the onshore breezes at sunrise. The combined launch capacity of all three battalions was about 200 balloons per day. Initial tests took place in September 1944 and proved satisfactory; however, before preparations were complete, United States Army Air Forces B-29 Superfortress planes began bombing the Japanese home islands. The attacks were somewhat ineffectual at first but still fueled the desire for revenge sparked by the Doolittle Raid. The first balloon was released on November 3rd, 1944. The Japanese chose to launch the campaign in November; because the period of maximum jet stream velocity is November through March. This limited the chance of the incendiary bombs causing forest fires, as that time of year produces the maximum North American Pacific coastal precipitation, and forests were generally snow-covered or too damp to catch fire easily. On November 4th, 1944, a United States Navy patrol craft discovered one of the first radiosonde balloons floating off San Pedro, Los Angeles. National and state agencies were placed on heightened alert status when balloons were found in Wyoming and Montana before the end of November.

The balloons continued to arrive in Alaska, Hawaii, Oregon, Kansas, Iowa, Washington, Idaho, South Dakota, and Nevada (including one that landed near Yerington that was discovered by cowboys who cut it up and used it as a hay tarp. Balloons were discovered as well in Canada in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Alberta, the Yukon, and Northwest Territories. Army Air Forces or Navy fighters scrambled to intercept the balloons, but they had little success; the balloons flew very high and surprisingly fast, and fighters destroyed fewer than 20. American authorities concluded the greatest danger from these balloons would be wildfires in the Pacific coastal forests. The Fourth Air Force, Western Defense Command, and Ninth Service Command organized the Firefly Project of 2,700 troops, including 200 paratroopers of the 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion with Stinson L-5 Sentinel and Douglas C-47 Skytrain aircraft. These men were stationed at critical points for use in fire-fighting missions. The 555th suffered one fatality and 22 injuries fighting fires. Through Firefly, the military used the United States Forest Service as a proxy agency to combat FuGo. Due to limited wartime fire suppression personnel, Firefly relied upon the 555th as well as conscientious objectors.

By early 1945, Americans were becoming aware that something strange was going on. Balloons had been sighted and explosions heard, from California to Alaska. Something that appeared to witnesses to be like a parachute descended over Thermopolis, Wyoming. A fragmentation bomb exploded, and shrapnel was found around the crater. On March 10th, 1945, one of the last paper balloons descended in the vicinity of the Manhattan Project's production facility at the Hanford Site. This balloon caused a short circuit in the power lines supplying electricity for the nuclear reactor cooling pumps, but backup safety devices restored power almost immediately. Japanese propaganda broadcasts announced great fires and an American public in panic, declaring casualties in the thousands. With no evidence of any effect, General Kusaba was ordered to cease operations in April 1945, believing that the mission had been a total fiasco. The expense was large, and in the meantime the B-29s had destroyed two of the three hydrogen plants needed by the project. On May 5th, 1945, a pregnant woman and five children were killed when they discovered a balloon bomb that had landed in the forest of Gearhart Mountain in Southern Oregon. Military personnel arrived on the scene within hours, and saw that the balloon still had snow underneath it, while the surrounding area did not. They concluded that the balloon bomb had drifted to the ground several weeks earlier, and had lain there undisturbed until found by the group.

The remains of balloons continued to be discovered after the war. Eight were found in the 1940s, three in the 1950s, and two in the 1960s. In 1978, a ballast ring, fuses, and barometers were found near Agness, Oregon, and are now part of the collection of the Coos Historical & Maritime Museum. The Japanese balloon attacks on North America were at that time the longest ranged attacks ever conducted in the history of warfare, a record which was not broken until the 1982 Operation Black Buck raids during the Falkland Islands War.

#second world war#world war 2#balloons#strange technology#military history#jetstream#imperial japan#japanese history#japanese#wwii#ww2

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

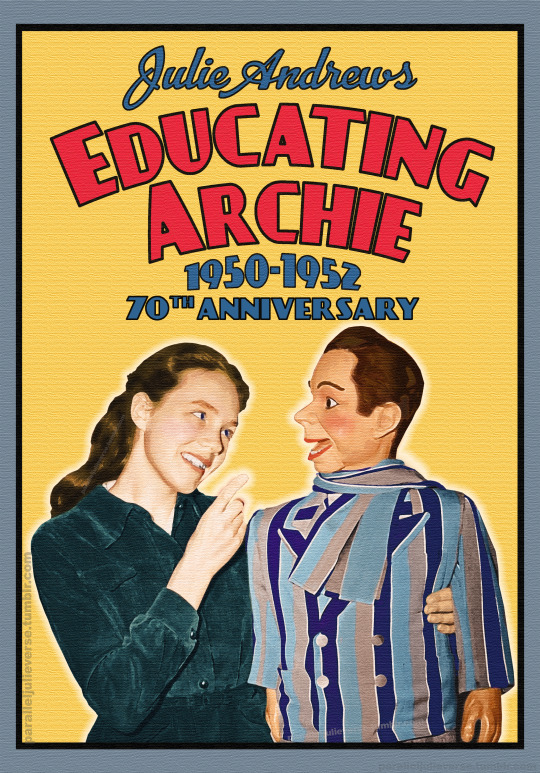

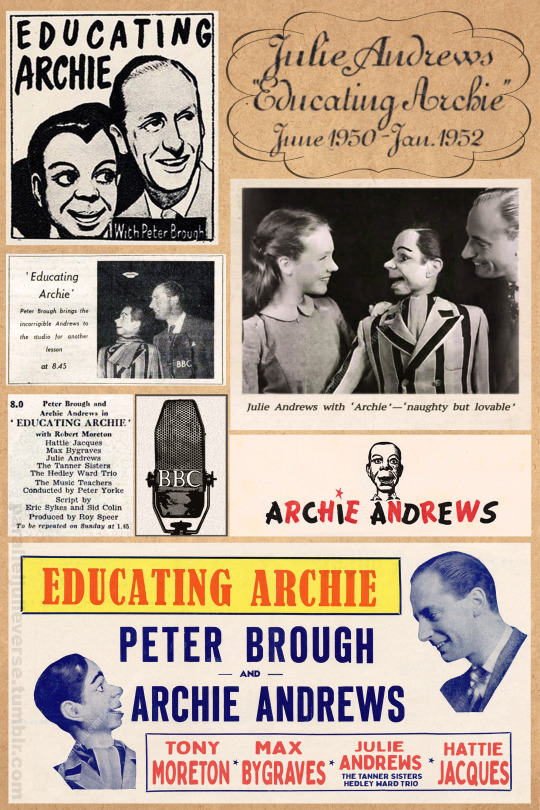

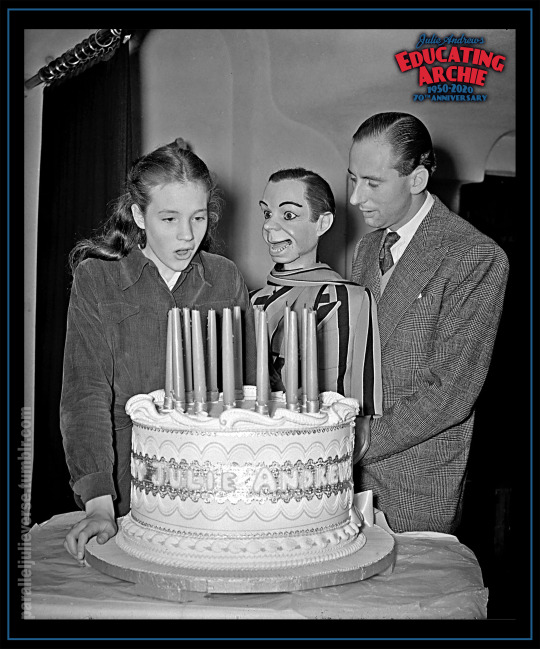

“We’ll be educating Archie, so we’ll be busy for a while...”

We are a little late with this commemorative post, but last month -- 6 June, to be precise -- marked the 70th anniversary of the debut of Educating Archie (1950-59), the legendary BBC radio series starring ventriloquist Peter Brough and his dummy, Archie Andrews. Fourteen-year-old Julie Andrews was part of the original line-up for the 1950 premiere season of Educating Archie and she would remain with the show for two full seasons till late-1951/early-1952.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the significance of Educating Archie during the ‘Golden Age' of BBC Radio in the 1950s. Across the ten years it was on the air, it grew from a popular series on the Light Programme into a “national institution” (Donovan, 74). At its peak, the series averaged a weekly audience of over 15 million Britons, almost a third of the national population (Elmes, 208). Even the Royals were apparently fans, with Brough and Archie invited to perform several times at Windsor Castle (Brough, 162ff). The show found equal success abroad, notably in Australia, where a special season of the series was recorded in 1957 (Foster and First, 133).

Audiences couldn’t get enough of the smooth-talking Brough and his smart-lipped wooden sidekick, and the show soon spawned a flood of cross-promotional spin-offs and marketing ventures. There were Educating Archie books, comics, records, toys, games, and clothing. An Archie Andrews keyring sold half a million units in six months and the Archie Andrews iced lolly was one of the biggest selling confectionary items of the decade (Dibbs 201). More than a mere radio programme, Educating Archie became a cultural phenomenon that “captured the heart and mood of a nation” (Merriman, 53).

On paper, the extraordinary success of Educating Archie can be hard to fathom. After all, what is the point of a ventriloquist act on the radio where you can’t see the artist’s mouth or, for that matter, the dummy? Ventriloquism is, however, more than just the simple party trick of “voice-throwing”. A good “vent” is at heart a skilled actor who can use his or her voice to turn a wooden doll into a believable character with a distinct personality and dynamic emotional life. It is why many ventriloquists have found equal success as voice actors in animation and advertising (Lawson and Persons, 2004).

Long before Educating Archie, several other ventriloquist acts showed it was possible to make a successful transition to the audio-only medium of radio. Most famous of these was the American Edgar Bergen who, with his dummy Charlie McCarthy, had a top-rating radio show which ran in the US for almost two decades from 1937-1956 (Dunning, 226). Other local British precedents were provided by vents such as Albert Saveen, Douglas Craggs and, a little later, Arthur Worsley, all of whom had been making regular appearances on radio variety programmes for some time (Catling, 81ff; Street, 245).

By his own admission, Peter Brough was not the most technically proficient of ventriloquists. A longstanding joke -- possibly apocryphal but now the stuff of showbiz lore -- runs that he once asked co-star Beryl Reid if she could ever see his lips move. “Only when Archie’s talking,” was her deadpan response (Barfe, 46). But Brough -- described by one critic as “debonair, fresh-faced and pleasantly toothy” (Wilson “Dummy”, 4) -- had an engaging performance style and he cultivated a “charismatic relationship with his doll as the enduring and seductive Archie Andrews” (Catling, 83). Touring the variety circuit throughout the war years, he worked hard to perfect his one-man comedy act with him as the sober straight man and Archie the wise-cracking cut-up.

Inspired by the success of the aforementioned Edgar Bergen -- whose NBC radio shows had been brought over to the UK to entertain US servicemen during the war -- Brough applied to audition his act for the BBC (Brough, 43ff). It clearly worked because the young vent soon found himself performing on several of the national broadcaster’s variety shows. His turn on one of these, Navy Mixture, proved so popular that he secured a regular weekly segment, “Archie Takes the Helm” which ran for forty-six weeks (ibid, 49). While appearing on Navy Mixture, Brough worked alongside a wide range of other variety artists, including, as it happens, a husband and wife performing team by the name of Ted and Barbara Andrews.

Fast forward several years to 1950 and, in response to his surging popularity, Brough was invited by the BBC to mount a fully-fledged radio series built around the mischievous Archie (Brough, 77ff). A semi-sitcom style narrative was devised -- written by Brough’s longtime writing partner, Sid Colin and talented newcomer, Eric Sykes -- in which Archie was cast as “a boy in his middle teens, naughty but lovable, rather too grown up for his years-- especially where the ladies are concerned -- and distinctly cheeky” (Broadcasters, 5). Brough was written in as Archie’s guardian who, sensing the impish lad needed to be “taken strictly in hand before he becomes a juvenile delinquent,” engages the services of a private tutor to “educate Archie” (ibid.). Filling out the weekly tales of comic misadventure was a roster of both regular and one-off characters. In the first season, the Australian comedian, Robert Moreton, was Archie's pompous but slightly bumbling tutor, Max Bygraves played a likeable odd-job man, and the multi-talented Hattie Jacques voiced the part of Agatha Dinglebody, a dotty neighbourhood matron who was keen on the tutor, along with several other comic characters (Brough, 78-81).

In keeping with the variety format popular at the time, it was decided the series would also feature weekly musical interludes. “Our first choice” in this regard, recalls Peter Brough (1955), “was little Julie Andrews”:

“A brief two years before [Julie] had begun her professional career as a frail, pig-tailed, eleven-year-old singing sensation, startling the critics in Vic Oliver’s ‘Starlight Roof’ at the London Hippodrome by her astonishingly mature coloratura voice. Many people of the theatrical world were ready to scoff, declaring the child’s voice was a freak, that it could not last or that such singing night after night would injure her throat. They did not reckon with Julie’s mother, Barbara, and father, Ted: nor with her singing teacher, Madame Stiles-Allen. In their care, the little girl, who had sung ‘for the fun of it’ since she was seven, continued a meteoric career that has few, if any rivals” (81).

As further context for Julie’s casting in Educating Archie, the fourteen-year-old prodigy had already appeared on several earlier BBC broadcasts and was thus well known to network management. In fact, Julie had already worked with the show’s producer, Roy Speers, on his BBC variety show, Starlight Hour in 1948 (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

Julie’s role in Educating Archie was essentially that of the show’s resident singer who would come out and perform a different song each week. In the first volume of her memoirs, Julie recalls:

“If I was lucky, I got a few lines with the dummy; if not, I just sang. Working closely with Mum and [singing teacher] Madame [Stiles-Allen], I learned many new songs and arias, like ‘The Shadow Waltz’ from Dinorah; ‘The Wren’; the waltz songs from Romeo and Juliet and Tom Jones; ‘Invitation to the Dance’; ‘The Blue Danube’; ‘Caro Nome’ from Rigoletto; and ‘Lo, Hear the Gentle Lark’” (Andrews 2008, 126)

Other numbers performed by Julie during her appearances on Educating Archie include: “The Pipes of Pan”, “My Heart and I”, “Count Your Blessings”, “I Heard a Robin”, and “The Song of the Tritsch-Tratsch” (”Song Notes”, 11; Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I). Additional musical interludes were provided by other regulars on the show such as Max Bygraves, the Hedley Ward Trio and the Tanner Sisters.

Alongside her weekly showcase song, Julie’s role was progressively built into a character of sorts as the eponymously named ‘Julie’, a neighbourhood friend of Archie’s. In a later BBC retrospective, Brough recalled that it was actually Julie’s idea to flesh out her part:

“We were thinking of Educating Archie and dreaming up the idea...and we wanted something fresh in the musical spot. We had just heard Julie Andrews with Vic Oliver in Starlight Roof...and we thought, why not Julie with that lovely fresh voice, this youngster with a tremendous range? So we asked her to come and take part in the trial recording and she came up with her mother and her music teacher, Madame Stiles-Allen...and Julie was a tremendous hit, absolutely right from the start. She used to sing those lovely Strauss waltzes...and all those lovely songs and hit the high notes clear as a bell. And then she came to me and said, ‘Look...I’m just doing the song spot, do you think I could just do a line or two with Archie and develop a little talking, a little character work?’ So, I said, ‘I don’t see why not’, So we talked to Eric Sykes and Roy Speer and, suddenly, we started with Julie talking lines back-and-forth with Archie, and Eric developed the character for her of the girl-next-door for Archie, very sweet, quite different from the sophisticated young lady she is today, but a lovely sweet character” (cited in Benson 1985)

As intimated here, an initial trial recording of Educating Archie was commissioned by the BBC, ostensibly to gauge if the format would work or not. This recording was made with the full cast on 15 January 1950 and was sufficiently well received for the broadcaster to green-light a six-episode pilot series to start in June as a fill-in for the popular comedy programme, Take It From Here during that series’ summer hiatus (Pearce, 4). The first episode of Educating Archie was scheduled for Tuesday 6 June in the prime 8:00pm evening slot, with a repeat broadcast the following Sunday afternoon at 1:45pm (Brough, 88ff).

All of the shows for Educating Archie were pre-recorded at the BBC’s Paris Cinema in Lower Regent Street. Typically, each week’s episode would be rehearsed in the afternoon and then performed and recorded later that evening in front of a live audience. Julie’s fee for the show was set at fifteen guineas (£15.15s.0d) for the recording, with an additional seven-and-a-half guineas (£7.17s.6d) per UK broadcast, 3 guineas (£3.3s.0d) for the first five overseas broadcasts, and one-and-a-half guineas for all other broadcasts (£1.11s.6d) (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

The initial six-episodes of Educating Archie proved so popular that the BBC quickly extended the series for another six episodes from 18 July to 22 August (“So Archie,” 5). Of these Julie appeared in four -- 25 July, 1, 8, 14 August -- missing the fist and last episode due to prior performance commitments with Harold Fielding. Subsequently, the show -- and, with it, Julie’s contract -- was extended for a further eight episodes (29 August-17 October), then again for another eight (23 October-18 December). These later extensions were accompanied by a scheduling shift from Tuesday to Monday evening, with the Sunday afternoon repeat broadcast remaining unchanged (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I). All up, the first season of Educating Archie ran for thirty weeks, five times its original scheduled length. During that time, the show’s audience jumped from an initial 4 million listeners to over 12 million (Dibbs, 200-201). It was also voted the top Variety Show of the year in the annual National Radio and Television Awards, a mere four-and-a-half months after its debut (Brough, 98; Wilson “Archie”, 3).

Given the meteoric success of the show, the cast of Educating Archie found themselves in hot demand. Peter Brough (1955) relates that there was a growing clamour from theatre producers for stage presentations of Educating Archie, including an offer from Val Parnell for a full-scale show at the Prince of Wales in the heart of the West End (101). He demurred, feeling the timing wasn’t yet right and that it was too soon for the show “to sustain a box office attraction in London” -- though he left the door open for future stage shows (102).

One venture Brough did green-light was a novelty recording of Jack and the Beanstalk with select stars of Educating Archie, including Julie. Spread over two sides of a single 78rpm, the recording was a kind of abridged fantasy episode of the show cum potted pantomime with Brough/Archie as Jack, Hattie Jacques as Mother, and Peter Madden as the Giant. Julie comes in at the very end of the tale to close proceedings with a short coloratura showcase, “When We Grow Up” which was written specially for the recording by Gene Crowley. Released by HMV in December 1950, the recording was pitched to the profitable Christmas market and, backed by a substantial marketing campaign, it realised brisk sales (“Jack,” 12). It was also warmly reviewed in the press as “a very well presented and most enjoyable disc” (“Disc,” 3) and “something to which children will listen again and again” (Tredinnick, 628).

In light of its astonishing success, there was little question that Educating Archie would be renewed for another season in 1951. In fact, it occasioned something of a bidding war with Radio Luxembourg, a competitor commercial network, courting Brough with a lucrative deal to bring the show over to them (Brough, 103-4). Out of a sense of professional loyalty to the BBC -- and, no doubt, sweetened by a counter-offer described by the Daily Express as “one of the biggest single programme deals in the history of radio variety in Britain” (cited in Brough, 104) -- Brough re-signed with the national broadcaster for a further three year contract.

For their part, the BBC was keen to get the new season up on the air as early as possible with an April start-date mooted. Brough, however, wanted to give the production team an extended break and, more importantly, secure enough time to develop new material with his writing team. Rising star scriptwriter, Eric Sykes was already overstretched with a competing assignment for Frankie Howerd so a later start for August was eventually confirmed (Brough, 105ff). The Educating Archie crew did, however, re-form for a one-off early preview special in March, Archie Andrew’s Easter Party, which reunited much of the original cast, including Julie (Gander, 6).

The second 1951 season started in earnest in late-July with pre-recordings and rehearsals, followed by the first episode which was broadcast on 3 August. This time round, the programme would air on Friday evenings at 8:45pm with a repeat broadcast two days later on Sunday at 6:00pm. The cast remained more-or-less the same with the exception of Robert Moreton who had, in the interim, secured his own radio show. Replacing him as Archie’s tutor was another up-and-coming comedy talent by the name of Tony Hancock (Brough, 111). It was the start of what would prove a star-making cycle of substitute tutors over the years which would come to include Harry Secombe, Benny Hill, Bruce Forsyth, and Sid James (Gifford 1985, 76). A further cast change would occur midway through Season 2 with the departure of Max Bygraves who left in October to pursue a touring opportunity as support act for Judy Garland in the United States (Brough, 113-14).

The second season of Educating Archie ran for 26 weeks from 3 August 1951 till 25 January 1952. Of these, Julie performed in 18 weekly episodes. She missed two episodes in late September due to other commitments and was absent from later episodes after 14 December due to her starring role in the Christmas panto, Aladdin at the London Casino. She was originally scheduled to return to Educating Archie for the final remaining shows of the season in January and her name appears in newspaper listings for these episodes. However, correspondence on file at the BBC Archives suggests she had to pull out due to ongoing contractual obligations with Aladdin which had extended its run due to popular demand (Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I).

Season 2 would mark the end of Julie’s association with Educating Archie. When the show resumed for Season 3 in September 1952, there would be no resident singer. Instead, the producers adopted “a policy of inviting a different guest artiste each week” (Brough 118). They also pushed the show more fully into the realm of character-based comedy with the inclusion of Beryl Reid who played a more subversive form of juvenile girl with her character of Monica, the unruly schoolgirl (Reid, 60ff). Moreover, by late 1952, Julie was herself “sixteen going on seventeen” and fast moving beyond the sweet little girl-next-door kind of role she had played on the show.

Still, there can be no doubt that the two years Julie spent with Educating Archie provided a major boost to her young career. Broadcast weekly into millions of homes around the nation, the programme afforded Julie a massive regular audience beyond anything she had yet experienced and helped consolidate her growing celebrity as a “household name”. Because Archie only recorded one day a week, Julie was still able to continue a fairly busy schedule of concerts and live performances, often travelling back to London for the broadcast before returning to various venues around the country (Andrews, 127). As a sign of her evolving star status, promotion for many of these appearances billed her as “Julie Andrews, 15 year old star of radio and television” (”Big Welcome,” 7) or even “Julie Andrews the outstanding radio and stage singing star from Educating Archie” (”Stage Attractions,” 4). In fact, Julie made at least two live appearances in this era alongside Brough and other members of the Educating Archie crew with a week at the Belfast Opera House in October 1951 and another week in November at the Gaumont Theatre Southampton (Programme, 1951).

Additionally, the fact that the episodes of Educating Archie were all pre-recorded means that the show provides a rare documentary record of Julie’s childhood performances. To date, several episodes with Julie have been publicly released. These include recordings of her singing “The Blue Danube” from 30 October 1950 and the popular Kathryn Grayson hit, “Love Is Where You Find It” from 19 October 1951. Given recordings of the series were issued to networks around Britain and even sent abroad suggests there must be others in existence and, so, we can only hope that more episodes with Julie will surface in time.

Reflecting on the cultural significance of Educating Archie, Barrie Took observes that, “Over the years [the] programme became a barometer of success; more than any other radio comedy it was the showcase of the emerging top-liner” (104). Indeed, the show’s alumni roll reads like a veritable “who’s who” of post-war British talent: Peter Brough, Eric Sykes, Hattie Jacques, Max Bygraves, Tony Hancock, Alfred Marks, Beryl Reid, Harry Secombe, Bruce Forsyth, Benny Hill, Warren Mitchell, Sid James, Marty Feldman, Dick Emery (Foster and Furst, 128-32). All big talents and even bigger names. However, it is perhaps fitting that, in a show built around a pint-sized dummy, the biggest name of all to come out of Educating Archie -- and, sadly, the only cast-member still with us today -- should be “little Julie Andrews”.

Sources:

Andrews, Julie. Home: A Memoir of My Early Years. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2008.

Baker, Richard A. Old Time Variety: An Illustrated History. Barnsley: Remember When, 2010.

Barfe, Louis. Turned Out Nice Again: The Story of British Light Entertainment. London: Atlantic Books, 2008.

Benson, John (Pres.). “Julie Andrews, A Celebration, Part 2.” Star Sound Special. Luke, Tony (Prod.), radio programme, BBC 2, 7 October 1985.

“Big Welcome for Julie Andrews.” Staines and Ashford News. 17 November 1950: 7.

Broadcasters, The. “Both Sides of the Microphone.” Radio Times. 4 June 1950: 5.

Brough, Peter. Educating Archie. London: Stanely Paul & Co., 1955.

Catling, Brian. “Arthur Worsley and the Uncanny Valley.” Articulate Objects: Voice, Sculpture and Performance. Satz, A. and Wood, J. eds. Bern: Peter Lang, 2009: 81-94.

Dibbs, Martin. Radio Fun and the BBC Variety Department, 1922—67. Chams: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018.

“Disc Dissertation.” Lincolnshire Echo. 11 December 1950: 3.

Donovan, Paul. “A Voice from the Past.” The Sunday Times. 17 December 1995: 74.

Dunning, John. On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Elmes, Simon. Hello Again: Nine Decades of Radio Voices. London: Random House, 2012.

Fisher, John. Funny Way to Be a Hero. London: Frederick Muller, 1973.

Foster, Andy and Furst, Steve. Radio Comedy, 1938-1968: A Guide to 30 Years of Wonderful Wireless. London: Virgin Books, 1996.

Gander, L Marsland. “Radio Topics.” Daily Telegraph. 13 March 1951: 6.

Gifford, Denis. The Golden Age of Radio: An Illustrated Companion. London: Batsford, 1985.

____________. “Obituary: Peter Brough.” The Independent. 7 June 1999: 11.

“Jack and the Beanstalk.” His Masters Voice Record Review. Vol. 8, no. 4, December 1950: 12.

Julie Andrews Radio Artists File I, 1945-61. Papers. BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham.

Lawson, Tim and Persons, Alissa. The Magic Behind the Voices: A Who's Who of Cartoon Voice Actors. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi Press, 2004.

Merriman, Andy. Hattie: The Authorised Biography of Hattie Jacques. London: Aurum Press, 2008.

Pearce, Emery. “Dummy is Radio Star No. 1.” Daily Herald. 6 April 1950: 4.

Programme for Peter Brough and All-Star Variety at the Belfast Opera House, 22 October 1951, Belfast.

Programme for Peter Brough and All-Star Variety at the Gaumont Theatre Southampton, 12 November 1951, Southampton.

Reid, Beryl. So Much Love: An Autobiography. London: Hutchinson, 1984

“So Archie Stays on.” Daily Mail. 1 July 1950: 5.

“Song Notes.” The Stage. 28 September 1950: 11.

“Stage Attractions: Arcadia.” Lincolnshire Standard. 18 August 1951: 4

Street, Seán. The A to Z of British Radio. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2009.

Took, Barry. Laughter in the Air: An Informal History of British Radio Comedy. London: Robson Books, 1976.

Tredinnick, Robert. “Gramophone Notes.” The Tatler and Bystander. 13 December 1950: 628.

Wilson, Cecil. “Dummy Steals the Spotlight.” Daily Mail. 27 May 1950: 4.

____________. “Archie, Petula Soar to the Top.” Daily Mail. 20 October 1950: 3.

Copyright © Brett Farmer 2020

#julie andrews#educating archie#peter brough#archie andrews#radio#bbc#british#1950s#ventriloquist#hattie jacques#max bygraves#tony hancock

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

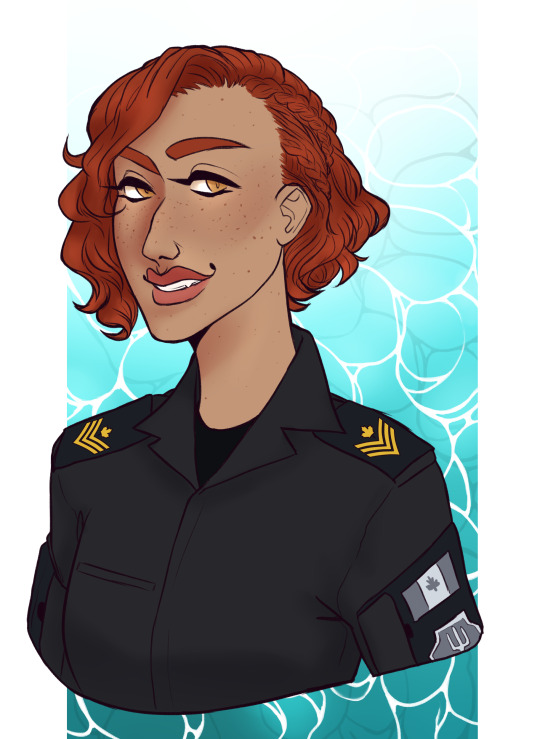

Decided to finally do her Bio

Name: Finley MacNamara

Alias: Aquila

Organization: NTOG

Home Base: CFB Halifax

Home Unit: NTOG (Atlantic)

DoB: 07/13 (30 y/o)

Birthplace: Mt Pearl, Newfoundland

Weight: 54 kg

Height: 1.67 m

Armour: 2

Speed: 2

Gadget: Puma AE UAS ‘Muninn’

Maove’s drone, nicknamed ‘Muninn’ was built with infrared technology useful in day, evening and night time situations. The drone will send a pulse when used, lighting up any operator within 20 feet of her, which she can see using her specialized glasses, nicknamed ‘Huginn’. The pulse lasts for 2 seconds before fading, and has 20 seconds between uses for up to 4 uses.

Primary Weapons:

C7-A2:

Damage- 62

Rate of fire- 725 full auto mode (can be switched between full auto, 3 round burst or semi auto)

Mobility- 50

Capacity- 30

M590A1 Shotgun

Damage: 48

Rate of Fire: 85 RPM

Mobility: 50

Capacity: 6+1

Secondary Weapons:

Sig Sauer p229:

Damage- 117

Rate of Fire- single shot

Mobility- 50

Capacity- 10

SMG-11

Damage: 35

Rate of Fire: 1270 RPM

Mobility: 50

Capacity: 16+1

BIOGRAPHY

“‘Aye, the ship may be good, but ‘tis the b'ys who make it great.”

Petty Officer 2nd Class MacNamara was born to a fisherman father and a barkeep mother in Mt Pearl Newfoundland. From a young girl to now, she was always active, looking for adventure; whether it be hiking along a trail, playing rugby or devising an elaborate prank on one of her senior coworkers.