#vaganova method

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Happy Birthday, Agrippina Vaganova.

“She knew everything there was to know about the body” said her students. June 26th is the birthday of history’s greatest ballet pedagogue - Agrippina Vaganova.

290 notes

·

View notes

Photo

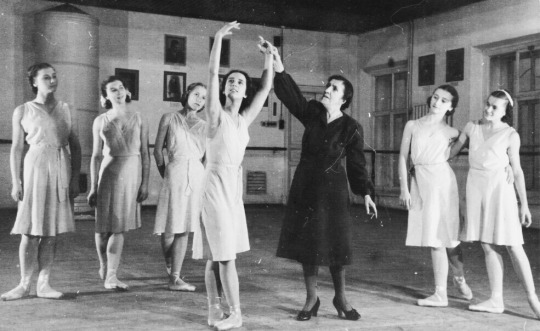

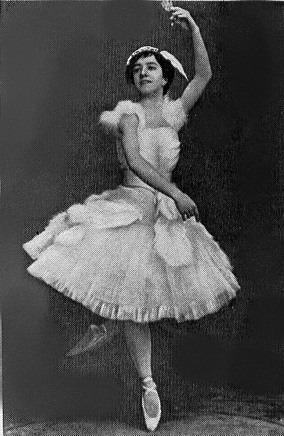

AGRIPPINA YAKOVLEVNA VAGANOVA ✝ (June 26 1879 - November 5, 1951)

Ballet did not come easily to Vaganova in her first years as a student, but slowly, through the efforts of her own will power, she was able to join the illustrious Imperial Ballet upon her graduation. By the time she attained the rank of soloist, Saint Petersburg balletomanes dubbed her queen of variations, for her unlimited virtuosity and level of technique.

During her years as a performer, Vaganova had observed the absence of method in Russian ballet. When she became a teacher, she selected the best aspects of the various styles and integrated them into a coherent system based in classical movement. Her teaching system emphasized harmony and coordination of all parts of the body but particularly developed the spine and neck, enabling her students to maintain a seemingly effortless core of stability while dancing.

Via Encyclopædia Britannica and Wikipedia

#ballet#Agrippina Vaganova#Vaganova Ballet Academy#Vaganova Method#Inspiration#ballerina#appreciation post

80 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's watch:

Maria Khoreva overview of Vaganova Academy focusing on years 1-5

My very not perfect translation:

Perhaps in this video, I’ll be able to debunk some of the untrue myths—and bring the true ones to life, one way or another.

Today, I want to share my learning experience with you. I studied at the Vaganova Academy from first through eighth grade, completing the full course of secondary vocational education. After that, I enrolled in the correspondence bachelor's program at the Faculty of Performing Arts, where I studied for three years. And now, this year, I’m finishing my master’s degree in the Faculty of Pedagogy.

I’m incredibly grateful—to the city, my family, my country, the circumstances, and all the people who supported me—for giving me the opportunity to gain such unique knowledge at the Vaganova Academy. To be able to touch this place steeped in history has truly been a gift.

Now, I’m excited to talk about how certain events influenced my life—and how different moments during one’s training can shape a student’s future in general. In our pedagogical master’s program, we study how to properly design a ballet training curriculum, how to combine physical and psychological aspects, and how to approach administration. Looking back now, especially at my time in the performing faculty, I see myself in a very different light—hopefully, a more accurate and kind one.

So today, I’d like to revisit those memories with you. I think it will be very interesting. Let’s get started!

(By the way—speaking of which—it might be a good idea to make a separate video someday about the whole admission process to the Vaganova Academy. It’s a big topic on its own. But for now, I’ll skip that part.)

I want to start my story with the school’s opening ceremony—our “line,” as we call it. If I remember correctly, it took place on September 7, not the 1st, because the Academy doesn’t always follow the standard rules of regular schools. Of course, Vaganova combines both general academic subjects and specialized ballet training, but I’ll talk more about that later.

So, our ceremony was on a rainy, cold day. There's a tradition at the Academy: a strong, stately boy graduate carries a tiny first-grader on his shoulder, and she rings a bell. This ritual is known as the “First Bell.” Every little girl in our class probably dreamed of being the one to ring it—including me. About 30 ambitious girls were admitted to our class, and from day one, everyone wanted to be first. I wasn’t chosen for that honor, unfortunately—but that’s okay. More was to come.

At first, I thought the hard part was over once I got in—but that wasn’t quite true. The first lessons were... strange, and to be honest, a little boring. I remember my very first classical dance class. We started doing slow movements, facing the barre. The teacher talked about “supporting legs”—the ones we stand on—and “working legs,” the ones that move. She said they “work,” like workers in a factory.

I was placed at the side barre, on the first line—not a prestigious spot. The central barre positions were the most desirable. We were placed randomly at first, and I remember standing there, staring out the window, far more interested in what was outside than in the slow, repetitive movements we were doing again and again.

In fact, during our very first classical dance class, I don’t think we did anything besides those tendus. It amazed me.

Before joining the Academy, I was involved in rhythmic gymnastics—I had already done some fouettés, a few jumps, and choreography classes were part of our training. So, when I started at Vaganova, I couldn’t understand why we were going back to such basic, seemingly simple movements. It all felt too easy to me.

But I couldn’t have been more wrong.

My first classical dance teacher—who, in ballet, is considered one of the most important figures in a dancer’s life—was Elena Georgievna Alkanova. A truly wonderful, soulful woman, who still teaches at the Academy. She brought a remarkable balance of discipline and love for the art into our classroom. She was meticulous with us, especially when it came to the most foundational elements of classical dance.

To me, being the head teacher of an elementary-level class is the hardest job in ballet. Children arrive either knowing nothing or, worse, having learned things incorrectly. Some come in with fixed ideas of what ballet should be, while others are simply bored. The teacher’s role isn’t just to teach proper technique from the very beginning—it’s also to light a fire in their hearts, to instill genuine love and motivation for the art. And doing that with young children is no small feat.

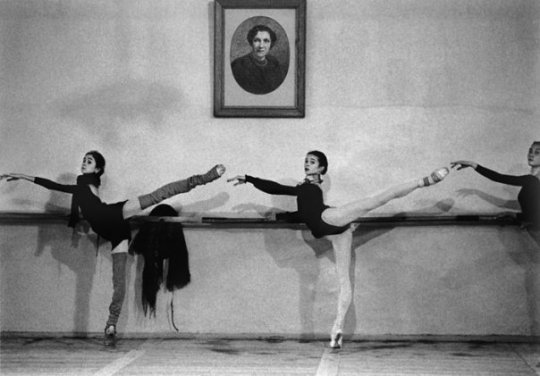

The method of Agrippina Vaganova—after whom the Academy is named—emphasizes a gradual progression: from the simplest ballet movements to the most complex variations. This means that in the first few years, there's no place for imitation of adult performance. Vaganova herself was a unique figure—a brilliant dancer who became a visionary theorist. She laid the foundation of the Russian ballet tradition that has amazed the world for generations.

In her writings, she stresses that the most important thing is to master the very basics—battement tendu, for instance, which is simply extending the leg along the floor to the side, or demi-plié, which is just a bend in the knees, but in a turned-out position. These movements may seem minimal, but they’re absolutely essential. From these foundations, all future grace, strength, and precision are built.

She even warned against assigning overly complex combinations too early in training. Why? Because when you skip the basics, students lose the ability to control their technique during more advanced movements. Ballet is built on perfect geometry—every line, every position must be precise from the very beginning. Without this, true mastery is impossible.

And yes, for all the beauty in Vaganova’s meticulous method… it could feel mind-numbingly boring. The exercises were slow, corrections were constant, and as young students, we didn’t yet understand why we had to "suffer" through such repetition. That was probably the biggest challenge of the first year.

Eventually, the movements became more difficult and more interesting. But to execute them correctly, we needed to rely on a growing internal mechanism—like mental gears slowly turning. I could feel new neural connections forming as we learned to process and apply the technique.

One correction from first year I’ll never forget: I was asked to lift my leg to the back, but keep my hip bones completely straight and motionless. I couldn’t wrap my head around it. How could that be anatomically possible? I was supposed to maintain a perfectly square alignment of my shoulders and hips while raising the leg behind me. But that’s exactly what classical ballet demands. We had to memorize this “geometry” so deeply that it would become second nature—even in the most advanced movements later on.

Looking back, classical dance lessons were without a doubt the most vivid, unforgettable part of my time at the Vaganova Academy. They were also the longest. Every day, we had what we called simply classics, and each session lasted around an hour and a half—though in reality, it was often longer. That's because we always ended up eating into our breaks for the sake of classical class. Typically, we had two double lessons: like real university-style sessions, with a break in the middle, and then another break before the next subject in the schedule. So, when you factored everything in, our “hour and a half” of classical dance often stretched quite a bit longer.

Now, I’d like to share how training is generally structured at the Vaganova Academy, especially the combination of academic and ballet subjects. Children enter the Academy after completing the fourth grade in general education. From there, they continue their academic studies alongside intensive dance training. Subjects include math, history, physics, chemistry, social studies, geography, and others I may not even remember now. We had etiquette lessons. We had English and French. French, in particular, was crucial because ballet terminology is still entirely in French. We had to learn not only the names of movements but also basic grammar and sentence construction to understand the meaning behind those terms—what exactly we were being asked to do in each movement.

There’s a common belief that in specialized institutions like music or ballet academies, general education is weak. But honestly, that wasn’t the case at all in my experience. Our academic standards were very high. In our cohort, there were two classes—A and B—and ours was an all-girls class for the first few years. Oh, how we all tried to be straight-A students! The competition was fierce—not just in the ballet studio, but also in our academic classes. We even competed in math! I’ll never forget mental arithmetic. It was terrifying. Our class teacher, Aleksandrovna Putina, and our math teacher—who was firm but progressive—used a very particular method. She would hand out a sheet of paper, quite small in size, and dictate math problems out loud, one after another. If you didn’t finish solving one before she moved to the next, your whole plan could fall apart. These were complex tasks too—definitely not easy. We trained our brains as much as we trained our bodies. Especially in those first few years, the workload was intense. The combination of general education and ballet was a huge challenge.

Our daily schedule typically started at 9:20 or 9:30 in the morning and ended around 6 p.m. Most days included a classical dance lesson in the middle. Lessons at the Academy usually began either at 9:00 or 11:00, depending on the class and level.

But one thing was certain: classical class always had to come early in the day. That’s because classical dance serves as the foundation and warm-up for the rest of a dancer’s training. It prepares the body, sets the tone, and tunes the mind and muscles for everything that follows—whether it’s rehearsal, another discipline, or a performance. That daily ballet class is essential—not just physically, but mentally. It’s the core of academic classical dance, and everything else builds from it. To properly integrate into the rhythm of academic classical dance, it made no sense to schedule ballet lessons later than early afternoon. That’s why classical classes were always set for either 9:00, 11:00, or at the latest, 1:00 p.m.—to accommodate all the various student groups, levels, and teachers across the Academy’s many halls.

Naturally, not everyone could take class at the same time. So, we were split across those three time slots, and our class almost always got the 1:00 p.m. slot. Only in the first year did we study at 9:00 a.m.—and I remember clearly how much I disliked it.

Imagine this: it's 9:00 in the morning, you’ve just rolled out of bed, and you’re already heading through the cold, damp streets of St. Petersburg—which somehow feel chilly even in summer, and downright miserable in winter. You arrive half-awake and have to immediately start moving your legs, performing precise ballet movements.

And what were we wearing? Well, in first grade, the uniform was just a simple leotard and socks. No warm-up gear, no tights covering the legs—completely bare. It was always cold and terribly uncomfortable to begin the day like that.

Later on, starting at 11:00 or 1:00 felt far better. We never had lessons at 11:00 during our entire time at the Academy—and I always thought that would have been the perfect time. I was so happy when I finally joined the theater and had the luxury of taking class at 11:00 every day.

As for the ballet studios themselves, the Academy had a quirky naming system. At first, I remember the “first top” and “second top” halls. Then after a few months, we started using names like “first bottom,” “second bottom,” “third A,” and so on. Only two studios had special names. One was “the hall,” where all senior exams were held. The other was “the large hall,” where major rehearsals for our graduation performances took place—the same performances that traditionally took place on the prestigious stage of the Mariinsky Theatre.

So, classical dance classes were slotted into that central daily space, and everything else—academic subjects—was arranged around them. We studied Russian, Piano, music, math, chemistry, physics, social studies, and so on. We started physics and chemistry a little later in our studies, like regular students in a typical school.

We even took the Unified State Exam like everyone else in Russia. We struggled through practice tests, official exams, and written assignments across all our subjects. We really did try to keep up with academic life and took it seriously.

At the same time, we had ballet-specific subjects—both practical and theoretical. As I mentioned earlier, we had etiquette and French from the first grade. I think French ended around the fourth grade, though to be honest, I don't remember exactly. We also had a course called “musical game,” which later evolved into music history and cultural education.

These cultural classes gave us inspiration, helping us become more educated and artistically aware—especially within the context of ballet and the broader cultural world.

All of this—the combination of general subjects and specialized classes—helped us grow into educated specialists in the field of ballet, culture, and dance. One of the first special disciplines we were introduced to in the first grade was historical dance. It’s actually a very interesting subject. We were taught ballroom dances, courtly steps from different eras—it was a completely different rhythm compared to the slow, mechanical exercises of classical dance. Historical dance gave us a chance to actually dance a little, to start feeling our own movement coordination, to get a sense of our organic relationship with dance. That’s so important at the beginning, because classical lessons at that stage were filled with endless repetitions of the most basic mechanics. So this subject gave us a breath of fresh air—something playful and expressive to balance things out. It was also one of the rare classes where we got to stand in pairs with boys, laugh, feel awkward, and slowly learn to overcome that awkwardness. Of course, that discomfort would eventually disappear in our later years at the Academy, and especially once we entered the world of theater—but in the beginning, it was a whole experience in itself.

Our teacher was Nina Viktorovna Ivanovna(?)—a very beautiful woman, always graceful in how she demonstrated movements during historical dance classes. Sometimes she’d raise her voice, but always with warmth, never in anger. We only had historical dance for 45 minutes, twice a week, but even so, those lessons had something truly magical and engaging about them.

I wonder what image you have in your mind right now. What do you imagine when you think of the Vaganova Academy? What do you see when you picture the primary school students? Little girls with neat ballet buns and perfect posture, already imagining themselves as future ballerinas?

Well, let me tell you—we didn’t have a strict school uniform, but we definitely had a set uniform for ballet class.

While we were in our general education classes, there was a sort of unofficial dress code—something black and white, ideally a white top and black bottom. But in reality, it was hard to stick to these rules because we constantly had to change clothes—before and after classical dance lessons. And we always ate into our breaks, so we had very little time to switch outfits. Before class, we also had to warm up properly, so our clothing needed to be functional and warm. In the corridors and classrooms, it could be quite drafty—which, honestly, seems inevitable in any school in our cold northern city. So of course, we all tried to adapt as best we could. Our moms tried to dress us as cozily and warmly as possible.

At one point—I can’t quite remember which grade it was—we were even allowed to wear special tracksuits, custom-made by the Grishko company. These were lilac-colored and specifically designed for students at the Academy. We wore them over our ballet uniforms, with our leotards underneath.

In first grade, the uniform for classical ballet class was all white: white leotard, white skirt, white socks, and white soft ballet slippers. Actually, in the very beginning, we weren’t even allowed to wear skirts—we had to be in just the white leotard. At the time, we didn’t really notice how uncomfortable that was… but looking back, it definitely was.

Now, as an adult, I’d never go into a ballet class wearing just a leotard from the start. I need warm-up clothes at the beginning of a lesson to properly heat up my muscles. Then I can gradually peel off layers—take off my woolen warm-up gear—and be left in just the essentials, which allows for better visibility of muscle work during the lesson.

Over time, the Academy’s ballet uniform evolved a bit. For the younger classes, the leotards were turquoise. Then, starting in 4th and 5th grade, they became lilac. From 6th to 8th year—what we called the “courses”—we wore coffee-colored leotards, like a latte shade.

And speaking of classes, there’s an interesting detail about the naming of grades at the Academy. You enter the Vaganova Academy after finishing 4th grade in a regular school. So, in terms of general education, you're starting 5th grade. But at the Academy, that same year is considered first grade. So the sequence goes like this:

1st year at the Academy = 5th grade general school

2nd year = 6th grade

3rd year = 7th grade

4th year = 8th grade

5th year = 9th grade

6th year = 10th grade

7th year = 11th grade

8th year= 12th grade

So, while we were studying general school subjects like 10th and 11th grade students elsewhere, we were also receiving a professional secondary education in ballet.

Girls were allowed to start wearing special ballet leotards from the second year. So we got used to all of this from a young age.

Now, about this eternal debate: “a leotard—necessary or not?” Ballet uniforms are an essential part of a dancer’s wardrobe—not just in class, but also on stage.

I remember going through a bit of a rebellious phase when I first started working at the theater. I stopped wearing leotards and tights to ballet class. It felt like now that I was a real artist, I should be as free as possible. I thought, “I’m not a student anymore; I don’t need to follow these rules.” So for a while, I didn’t wear a leotard in class. And yes, in some ways it really was more convenient—you didn’t risk ruining a leotard or tights that you might need for a performance.

But after a few years in the theater, I came to realize that ballet leotards and tights are, in fact, one of the defining symbols of an artist’s discipline. And now? I wear pink tights every day for class—because I want to see my legs exactly as they’ll look on stage, in front of an audience.

I also remember that for quite a long time, I was totally lost trying to navigate the Academy’s corridors—I was constantly confused about where everything was. Although to be honest, compared to the Mariinsky Theater, the structure of the Academy building is actually quite simple.

The building itself is beautiful. It was designed by the Italian architect Carlo Rossi, and it stands on a stunning street—one of those perfect architectural imperial ensembles. The street ends at the Alexandrinsky Theater, and the entire row of buildings is painted a soft, pale yellow that gives the whole area an imperial, majestic feel.

I remember being told in class that the street’s length is 220 meters, its width is 22 meters, and the height of the buildings lining it is also 22 meters. Even the numbers speak to a kind of beauty. And the love for beauty wasn’t taught only in ballet lessons, but also in our general education subjects. It was in everything around us—even just walking down the corridors.

Portraits and epigraphs hung on the walls—images of legendary ballet dancers, iconic figures of our art. And of course, all of that couldn’t help but inspire you.

Even now, when I return for exams during my master’s program, I look at those portraits with deep respect and admiration. Now, of course, I understand so much more. I can truly appreciate who these people were—and that’s exactly why they leave such a strong impression on me.

But even back then, something was being built inside of me—a foundation for a lifelong love of this art. A love that’s stayed with me for my entire career... and for life, really.

But after such an enthusiastic monologue about how wonderful, beautiful, and inspiring it all was, it’s only fair to move on to a harder topic—an alarming one, and for us students, the scariest of them all.

Even now, I still remember, with a flutter in my chest and a kind of inner shiver, the classical dance exams. It seems strange to talk now about how anxious we were, but honestly—there are no words to convey the fear. It was pure horror.

And you had to fight that horror—right up until graduation. For some reason, this exam remained the single most terrifying part of our lives as students at the Academy.

The thing is, each year the Academy holds exams in all of the core dance disciplines. But the classical dance exam? That’s the most important one. Sixty students were admitted to our class. By graduation… maybe only half remained. Every year, students are weeded out—those who didn’t manage to master the program. Because the Academy simply can’t produce that many ballet specialists. The training process is grueling and intense.

And here, of course, we have to talk about something heartbreaking—not just the academic challenge, but the physical toll. The tragedies that come from the body not cooperating.

Sadly, and to my deep regret, it happens: some students enter the Academy, study for years—even just one year is a lot, especially for a fragile child’s mind—and they can’t imagine any other path than becoming a dancer. They’ve become totally immersed in this life, in these ideas, in this system—a beautiful system, yes, but also a strict one. And suddenly… the body fails.

Maybe like a weightlifter, your body becomes too muscular. Maybe you begin to grow too fast, or you lose strength. And it’s a tragedy, because that child has no control over it. It’s just genetics. It’s some cruel mix of factors that can’t be influenced or predicted.

Ballet is an aesthetic art. And unfortunately, the jury sitting at those classical exams must assess not only performance, but whether a student matches the visual and physical ideals of the art form. Those who don’t fit that standard... are expelled.

I hate that word—expelled. Expulsion. “You’ll be expelled.” We heard it constantly—from teachers, from classmates. That word burrows into your subconscious. It has a kind of dark, heavy power.

And yes, precisely because of that word—and not only because of it—but because of everything around it, those classical exams were so frightening. It felt like everything—absolutely everything—depended on that one day. How you looked that day. Whether you could nail certain pirouettes or other elements. Whether your turnout was enough on that day. Whether your skirt was correctly aligned with your leotard on that day. It seemed like your entire future would depend on the commission’s evaluation of that day.

But in truth, that’s not how it works at all.

What really matters is how well you know the material. How attentively you’ve listened to your teachers. How engaged and present you’ve been throughout your training. And strangely enough, how much you can remain yourself—not following anyone else’s instructions except your teachers', not trying to mold yourself into what you think the system wants, but working diligently, persistently, with your hands, your feet, your whole being—on yourself.

That’s what truly determines your path.

But at the time, we were convinced the whole world hinged solely on those exams: on that one moment—on that exam.

The anxiety would start building at least a week in advance. A whole week where I could barely breathe. I couldn’t even take a full sigh. And oddly enough, it felt like you had to keep yourself wound up before the exam, just to stay sharp—to make sure you didn’t forget anything, to boost your concentration.

Even now, before performances, I don’t get as nervous as I used to before those exams. And our teachers? They were just as nervous as we were.

After I passed the classical exam, all the others—even those in other special disciplines—never seemed quite as terrifying.

For example, in the fourth year at the Academy, in addition to historical dance, we had a subject called character dance. On stage in classical ballets, this includes dances like the Hungarian, Polish Mazurka, Russian, Spanish, Gypsy dances—all the national folk styles. In ballet, these are called character dances.

The exam in character dance was also challenging and unpredictable. We were definitely afraid of it—but not as much as classical.

I remember starting this whole story with how bored I used to be—just standing there, watching people move their strange little feet, doing strange movements with no meaning. But that boredom faded very quickly. The teachers’ demands grew, and we slowly began to understand what was expected of us. We started to realize how important it all was.

And then came this enormous sense of responsibility. Responsibility to ourselves. To our families. To our parents who supported us through all those years at the Academy. Their support—honestly—it was immeasurable. I don’t know… it seems to me they were far more nervous than we were.

And you’d think, “How is it even possible to be more nervous than we are?” But I’m sure of it—our parents were.

That responsibility—to all those who believe in you—starts to sink in. You must get a good grade. You must make your teacher proud. You must prove to everyone that you can.

That understanding hits quickly. It hits when you see how your classmates are managing certain movements—when you notice that you can’t do something someone else can. Or vice versa—when you suddenly can do something others can’t. And then your name is used as an example, and you feel like, “Okay, I have to do even better. Even better.”

And of course—it was unbelievably interesting. That’s when our journey as ballerinas truly began. Every one of us thought so.

I won’t say it was easy. But I can’t help but admit—it was genuinely fascinating.

Speaking of fascinating moments: one of the most fun parts of our training was stage practice. Especially in the first few years, stage practice was pure joy. Because it happened on the stage of the Mariinsky Theater.

The thing is, in many classical ballets, there are roles for very small children—little ones, who look almost like babies on stage. And that’s where first- and second-year students came in. We were those “babies.”

I don’t even know why it worked that way—but somehow, we really did look much younger than we actually were. Maybe it’s the costumes, maybe it’s the magic of ballet.

And you know what? That illusion of youth continues all through Academy training. Ballet girls and boys… somehow always end up looking older later, and younger earlier.

They seem to mature later. Maybe because of the immense workload. Maybe it’s the refined atmosphere inside the Academy. Who knows?

So, on the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre, we probably didn’t go out right away—but the Academy’s students did, in various performances. There was the Waltz in Sleeping Beauty, the children’s dance in Shurale, the elves in A Midsummer Night’s Dream—and that one was one of my absolute favorites. I got to perform in it as a child, on the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre.

I even took part in the premiere of that ballet. The directors came from the Balanchine Foundation to stage it. It was a completely new experience for us—we weren’t dancing classical choreography, but something fresh, modern, and unfamiliar. George Balanchine’s choreography was introduced to us for the first time as students, and it had us doing these unusual, fascinating movements on stage.

We got to try on new costumes—sewn just for us. Brand new elven headdresses. This whole elven fairytale world of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was magical.

By the way, this ballet—Midsummer Night’s Dream—if it ever comes back to Russian stages, I highly recommend seeing it. It’s like a gentle fairytale, but also a breathtakingly beautiful visual story set to Mendelssohn’s music. It makes you think about things. It makes you marvel at the beauty of Shakespeare, the brilliance of Mendelssohn, and the elegance of Balanchine’s choreography. If you ever get the chance, do watch it.

There were some standard roles for the youngest children in stage practice—like the children kidnapped in the Waltz from Sleeping Beauty, or the children's dance in Shurale. But I didn’t get cast in those parts—I was a little taller than what was needed for those roles.

So instead, in my first year, I danced… a dwarf.

Yes, a dwarf! It was actually a really funny part because kids were supposed to look cute and endearing—and we wore these enormous masks. Honestly, I don’t even know what they were made of. Maybe papier-mâché? The dwarf masks looked amazing from the audience—adorable and just fun. But inside the mask? Honestly… you could barely see anything. At least in mine. I danced that dwarf part several times in a row, in different casts—but I still don’t understand how I managed to dance properly in that mask. It was like moving through a fog. At the Academy, we’d rehearse everything in the studio without the masks, super carefully—but as soon as we put them on, and went out on stage, it was chaos. And then, right as we entered as dwarfs, the lightning and thunder effects would start. In the darkness, with those masks on, we couldn’t see a thing. We bumped into each other, missed our marks—it was kind of a disaster, but also kind of hilarious.

That ballet is still performed now, by the way, at the Minsk Theatre. It’s a beautiful production, a fairytale again—this time about a bird-girl and the arrival of evil spirits. It gets very dark on stage during those scenes—so, naturally, we couldn’t see anything then either. And, as little kids, no one really tells you how to handle that kind of thing. Still, it was a fascinating experience. I think it was actually more exciting than some of the standard children’s dances.

I danced dwarfs in Shurale. I danced elves in Midsummer Night’s Dream. And I also participated in the annual Nutcracker production.

The Nutcracker was performed entirely by the Academy. The graduating students danced the lead roles—Masha and the Prince. Students a bit younger danced the snowflakes, the waltz of the flowers, the parents at the Christmas party—and the youngest children performed as kids at the tree. Every age had their part. In third grade, I danced the pas de trois. And I also danced the doll. It was always an immersion into another, completely magical world. My warmest first memories of the Mariinsky Theatre come precisely from those days of stage practice.

I recently wrote about how even the apples and cutlets in the Mariinsky Theatre buffet left the brightest and most delightful impressions. Just getting to rehearse and perform there was special—but those little details made it unforgettable. Sure, we could dance these same parts in the Academy’s rehearsal halls, and we did, for a long time, over and over. But to actually get to the Mariinsky Theatre… to feel it not just with your hands and feet, but with all your senses—that was a different kind of magic. The cutlets, the cottage cheese casseroles—I adored them. They even gave us those big liter juice boxes for a while, and it all felt so amazing. It seemed to us that someone cared so much about us there. At the Academy, of course, people cared too. But it didn’t feel the same. At the theatre, we felt like royalty—just because we were given such delicious food. Afterwards, we would dance, rehearse, and walk around with joy—completely absorbed in the enchantment of ballet.

That’s probably all I can share with you today, if I try to keep this in the format of a regular conversational video—10 to 20 minutes. Otherwise, I could go on for tens of hours. I could honestly talk about this endlessly.

I am infinitely grateful to all the teachers who guided us through that journey, to everyone who surrounded us at the Academy. I’m grateful to my classmates. To the older students who helped us. To the younger students who stressed because of us.

It was such a beautiful, magical process—and I can’t wait to tell you about my time in the senior classes. There’s so much to say about that. We started having special disciplines, the stakes got higher, the emotions deeper, and everything became much more difficult—and sometimes even painful.

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova academy#vaganova ballet academy#mariinsky theatre#vaganova#agrippina vaganova#maria khoreva#vaganova exam#vaganova class#mariinsky#mariinsky ballet

43 notes

·

View notes

Photo

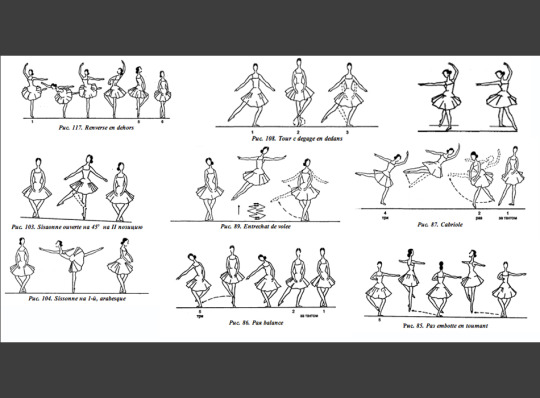

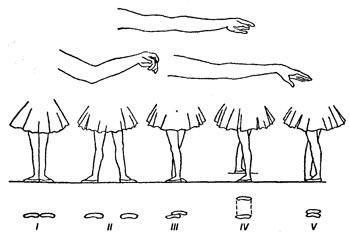

Pictures from “Basic Principles of Classical Ballet”, making Vaganova Method accessible.

Source

30 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Nutcracker Rehearsal by the two top students at Vaganova Ballet Academy- Kristina Shapran as Masha-princess, and Sergei Strelkov as Nutcracker-prince

#ballet#Vaganova#vaganova#Vaganova Ballet Academy#Vaganova method#Nutcracker#Kristina Shapran#Masha#Sergei Strelkov#rehearsal

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Agrippina Vaganova, Basic Principles of Classical Ballet; Russian Ballet Technique, 1946.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Join us at the 36th Annual Children's Festival, "The World of Dance," presented by Brighton Ballet Theater (BBT) on Thursday, June 22nd, 2023, at 6:30 PM at #Kingsborough #CUNY.

Despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, BBT remains committed to nurturing responsible, well-rounded individuals through dance education. This festival is the highlight of the year for our students, who have dedicated themselves to combining their academic studies with weekly rehearsals.

Secure your tickets now! They can be purchased online at www.bbtballet.org, by calling 929-610-2117, or in person at the BBT office by appointment. For more details, reach out to BBT | The American School of Russian Ballet at Kingsborough.

The 36th Annual Children's Festival is a unique platform for our students to showcase their talents and develop essential life skills. We are honored to serve our community and look forward to celebrating this special moment with all of you.

Donations are vital in expanding our programming and providing scholarships to deserving students. Brighton Ballet Theater is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and your contribution is tax-deductible. Help us make a difference by visiting www.bbtballet.org.

Dance education at Brighton Ballet Theater | The American School of Russian Ballet at Kingsborough offers a remarkable and enriching experience, fostering physical, creative, and emotional growth in children. Let them discover their unique style and become confident, well-rounded individuals.

#ballet#classical ballet#dancers#vaganova method#learn to dance#dance#brooklyn#russian ballet#dancing#kingsborough

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Today’s watch:

Nina Kaptsova, Sugar Plum Fairy, Bolshoi theatre.

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#Nina Kaptsova#bolshoi theatre#bolshoi ballet#nutcracker#sugar plum fairy#Youtube

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's watch:

Raymonda debut Alexandra Khiteeva preparation with coaches Margarita Kullik and Yulia Makhalina. The tutors, both students of Natalia Dudinskaya. March 2025, Mariinsky Theatre

youtube

Intro: Yulia Makhalina: I received this role from the hands of an outstanding master. It was my happiness to work with her — I was lucky. Natalia Dudinskaya (coaching Yulia): It's like [touching] with a little paw Alexandra Khiteeva: We’re trying to bring back what was staged back then. Margarita Kullik:It was very important to me that Yulia Makhalina passed on exactly what Natalia Mikhailovna had passed on to her, so that it would be preserved in one of my students. Alexandra Khiteeva:You have to somehow time it right so you don’t over-rehearse — and hit that exact peak when you're ready to be on stage Margarita Kullik:Like with Natalia Mikhailovna — every little pinky, every glance… I dreamed of being able to name it. To name the Raymonda — but I didn’t succeed. Today is a historic event: a true birth of a new Raymonda happened on stage. Fadeyev/Kullik(?): So you gave birth to a good little Raymonda.

During rehearsal: Makhalina or Kullik: The body of the hand, yes, and the little brushes (fingers) Everything the same, just to the side, not back, but to the side. Okay, good, good. Yulia Makhalina: Just make a little emphasis. Now we've already taken this position, yes, let's go. Let's go, and like this, just like that — perfect! Alexandra Khiteeva: The second time, I made the wrong ball (shape), I did it like this… Makhalina/Kullik: Yes, I noticed. The main thing is that you understood it. Alexandra Khiteeva: Initially, you need to learn the entire text, rehearse it, and assemble the whole performance. It’s always a rather long process. Margarita Kullik: Sashenka, you forgot again. — it's fine. Alexandra Khiteeva:I've been preparing Raymonda for about two weeks. It may not seem like much, but already there’s a feeling that I want to get out there and dance as soon as possible. Makhalina/Kullik: Sanya, here, there — tada-dam, tada-dam, move a little more, and with that, you know, well… And especially the first part, remember I told you to walk more so there’s a diagonal, and here more of this… ta-ta-ti-ta-ta. There should be confusion, confusion, you understand?" Alexandra Khiteeva: About two years ago, I danced Raymonda on the Primorsky stage of the Bryansk Theater, just once. And back then, I was also preparing it with Yulia Viktorovna Makhalina and Margarita Goralidovna Kullik. Somehow, we also prepared it very quickly. I think we even did it in less than two weeks. After two years, I was trusted to dance on my home stage. I thought that some moments would be forgotten, but when I started remembering and rehearsing again, my body hadn’t forgotten. It recalled everything by itself, even though in my memory it seemed like it was far away. Makhalina/Kullik:Shh, it's structured, yes, just a little bit… and then, in such confusion, so there’s a difference. Right now, everything is for one night. Three… You’re here with the girl and your friend. You kind of take control with them, they’re like family, your close ones, and you… change the mood, the water, and the breed today. Somebody: This is just like Yulia Viktorovna Makhalina. Alexandra Khiteeva: She showed a lot of little details that are now lost, and some ballerinas now dance in their own way, adding their own touches. She shows exactly how she prepared it with Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya. Yulia Makhalina: I received this role from the hands of an outstanding teacher, the greatest ballerina, the incomparable Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya. My happiness was working with her, I was lucky. I was lucky not only because such a chance came in my life, but because I was physically ready to take such serious material from the hands of the master. In flashback: Natalia Dudinskaya (coaching Yulia): "It's like a cat's paw, with that soft little paw, you know? Otherwise, they’re a bit too loud. Yulia Makhalina: On the other hand, I’m afraid it will be too limp. Natalia Dudinskaya: No, it shouldn’t be limp. Well, you know, like a cat's paw, just like this, one, two." .... With the hands, something like little dips — look, pam-pam-yam-pam-naram. Now: Margarita Kullik:It was very important to me that Yulia Makhalina passed on exactly what Natalia Mikhailovna had passed on to her, so that it would be preserved in one of my students. Yulia Makhalina: I was happy to help Riti Kullik; she is our wonderful teacher, a master, and she herself is a beautiful ballerina. But most importantly, she is the beloved, beloved student of Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya.

Back in rehearsal: Makhalina/Kullik: I don't want to open up here, but instead just go into this set of movements, and already move into it. But I need a little more energy, just a bit like this, somewhere around here.

Yulia Makhalina: But I must remember that back in my second year at the Vaganova Academy, I was entrusted with the role of Raymonda, which I prepared with Konstantin Mikhailovich Sergeyev. I was still young, and Konstantin Mikhailovich Sergeyev instilled Raymonda in me even then. Konstantin Sergeyev was a very delicate restorer of performances, and Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya, of course, as she was his wife and assistant for all of Sergeyev’s productions, knew the entire style thoroughly. Let me return to the school, because back then it was really hard for me. We had a teacher with whom we were the first class, Marina Vasilieva, and the parallel class was with Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya. There was a lot of tension, we had to keep up. If someone had told me back then that I would later work with the great master Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya in the Mariinsky Theatre, honestly, I would have thought it was a dream.

In flashback rehearsal: That’s good. And this adagio, which Konstantin Mikhailovich staged in The Sleeping Beauty, he and Kostyazilinsky complement each other so perfectly. If Sergeyev had seen how they danced the adagio, I think he would have been very pleased, truly, because both are tall, both are beautiful, both have long lines. I think I received immense pleasure today, and I’m really happy that I managed to prepare such a performer. Now: Alexandra Khiteeva: You know, sometimes it happens that when you’ve been rehearsing for so long, it doesn't work to your benefit. It starts to blur, to get stuck. Some moments that used to work well suddenly don’t, or something is just off. The style, the presentation starts to feel too forced, and I really don’t like that. You have to time it right so that you don’t over-rehearse and hit the peak of when you’re ready to step on stage During rehearsal: Alexandra Khiteeva: You filmed it, right? Makhalina/Kullik/Music conductor: We filmed it ourselves. Try, Sashul, try to go a bit faster. Maestro, we’re just following the wishes of Natalia Mikhailovna. The last donation… yes, now Sashka is gripping my hand because… and then… Right before performance to Sasha: Yulia Makhalina: Happy birthday to you, yes, in the historic house of Pyatipa, just like here, where everything shines and sparkles, calm and serene… we are your support group, don’t be afraid, you’re absolutely ready. Interview: Margarita Kullik: I’m very grateful to Yuri for this, for responding and giving us so much warmth and soul. She gave us her heart, and I was able to preserve Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya’s notes, every finger, every wrist, the turn of the head. She said that Raymonda is such a vast image, and like Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya, every little finger, every glance, this sort of… understand, this detachment from everything that surrounds us. But it was something extraordinary, an aura around each image.

Somebody: How they loved this adagio with Sergeyev, which goes in the dream, you understand, it’s something extraordinary. Natalia used to say how we, with Kostya, loved this adagio.

In flashback: Konstantin Sergeyev: These are questions of continuity—continuity coming, so to speak, from Vaganova through Dudinskaya to other subsequent teachers and to the next generation. This is the eternal life, the continuous and mighty strength that gives the right for our Leningrad school to truly be called academic. Here, too, there is a great contribution from Natalia Dudinskaya. (Dudinskaya enters room...)You came in time, I’ve already said everything about you that I thought. Natalia Dudinskaya: I’ve heard all of this, you know. Konstantin Sergeyev:It’s not good. If I knew you were standing there, I would never have said anything like this. Natalia Dudinskaya: Please forgive me.

Now: Margarita Kullik: I dreamt of Raymonda, but I couldn’t achieve it. I deeply regret this, because this role, specifically with Natalia Mikhailovna, I didn't prepare it. Not that I didn’t dance it, but you see, I was forced to turn to Yulia now because I want it to be a real performance, the one that Natalia Mikhailovna Dudinskaya passed on. Because this is the greatest value. Yulia Makhalina: I thank Margarita for trusting my memory when we were two completely different people, two different ballerinas, you could even say from different repertoires. But we united, we were brought together by Alexandra.

After performance: Alexandra Khiteeva: For now, I feel confused, very empty inside, but of course, I’m very happy that this happened today.

Yulia Makhalina: It’s a historic event, and for me, it’s double special, because on this stage, exactly 32 years ago, the celebration of the birth of the Raymonda image in my performance took place. I’m doubly happy because on stage, the birth of a new Raymonda really happened. It’s another Raymonda, it’s the Raymonda of the 21st century. But what’s important is that it keeps the traditions, and I sincerely congratulate not only the heroine Raymonda, but everyone responsible for this celebration.

Fadeyev/Kullik(?):No, not just any Raymonda, but a great performance—Luka, you gave birth to a beautiful Raymonda.

Margarita Kullik: Therefore, I'm so happy for Sasha, that she danced this role, she was born for it. As Yulia said, Sasha, I started with this – Yulia congratulated Sasha on the birth of Raymonda, on her 'birthday' as Raymonda. But it’s truly like that for us; every role is a big event.

Yulia Makhalina: So here I keep this photograph. Today, my talisman was here. We danced the premiere of Raymonda with Konstantin Zaklinskij. This is my memory and my pride.

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova academy#mariinsky theatre#mariinsky#mariinsky ballet#mariinsky raymonda#Alexandra Khiteeva#raymonda ballet#Margarita Kullik#Yulia Makhalina#Natalia Dudinskaya

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today's watch:

Renata Shakirova interview as she prepares for The Little Humpbacked Horse, Mariinsky, 2021

youtube

I've translated some parts, but not everything. Interview with Renata Shakirova

Interviewer: Hello, guys! I’m here today with Renata Shakirova in her personal dressing room. Tonight, she’ll be performing the role of the Tsar Maiden in the ballet Little Humpbacked Horse. Hi, Renata!

Renata: Hi, everyone!

Interviewer: In today’s episode, we’ll show you how a first soloist prepares for a performance and what goes on both before and after the show.

Preparations

Interviewer: Renata, what are we doing?

Renata: Is it possible for the braid to start lower?

Hair Stylist: Of course!

Renata: Thank you!

Interviewer: Renata, why do you have two crowns?

Renata: So I could choose which one I like better. You’ll help me decide. This one or the smaller one?

Interviewer: The smaller one.

Renata: The decision is made! This is my costume for today—it’s very petite and beautiful.

Braiding Hair:

Adding extension hair

Renata: Back in the Academy, I constantly braided girls’ hair. I managed to do half of it nicely.

Interviewer: Did you pull girls’ braids?

Renata: Once or twice… did you?

Renata hands hairpins to speed up the process.

Foundation Application: Interviewer: What did you just apply? Renata: Foundation! (Securing the crown.)

The Interview

Interviewer: Stop laughing! This is a serious interview. Renata: The most serious one. Interviewer: Renata, I have a few questions for you. Are you ready? Renata: I’m ready! Interviewer: Tell us about yourself. Where are you from? Renata: I was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. When I was four, my family moved to Bashkortostan. Since I was about five years old, I lived in Sterlitamak. Interviewer: Dance company “Solnyshko” says hi. Renata: Thank you! Hi to them, too! Interviewer: Was “Solnyshko” your first dance company? Renata: My first and last, so to speak. All my childhood memories are from there. We attended different festivals, visited cities like Samara and Saratov, and it was amazing. Interviewer: How many years did you dance there? Renata: Until I was 11, when I got into the Academy. Teachers recommended auditioning since they thought I had potential. I loved dancing and being on stage as a child.

A Funny Childhood Memory Renata: Once, at a festival, my dance number began with me standing alone on stage. A pre-recorded track was supposed to play, but it never did. I was embarrassed, my heart was in my throat. I just stood there until the end, waiting for the track. Everyone started laughing, and I had no idea what to do. It was a good exercise in resilience.

About Stage Makeup Interviewer: You do your own stage makeup? Renata: Yes, it’s easy for you boys since everything is done for you. We do everything ourselves. I even took professional stage makeup courses because my makeup would wear off during applause. Interviewer: So this is professional stage makeup? Renata: Yes. Interviewer: You have so many brushes. Renata: That’s only half of them. Interviewer: Do you really need so many? Renata: I personally do. Interviewer: I’d only use three. Renata: I’m a girl. Interviewer: I’m always amazed how girls do their makeup. They use so many brushes and products, but it all looks the same until suddenly, it’s done. Renata: Slowly, a face appears. It’s funny because when I leave the theater, no one recognizes me. It’s happened multiple times.

What Motivates You? Interviewer: What motivates you to get up every morning, do ballet, and perform? Renata: Honestly, I’m lazy, but if I’m unprepared, the performance won’t go well. Videos of a bad performance are painful to watch. I can’t always watch my own videos, but it keeps me motivated to improve.

Ballet Nightmares Interviewer: Do you have any ballet-related nightmares? Renata: The biggest one is being on stage and forgetting the choreography. Interviewer: I’ve also dreamed about sliding down a tilted stage with the audience laughing. Have you had that nightmare? Renata: No. Interviewer: Now you will! Renata: In Italy, the stage is so tilted, it’s like my nightmare coming true.

Falling on Stage Interviewer: Have you fallen on stage? Renata: Too many times. Initially, it felt catastrophic. But other ballerinas comforted me by sharing their own funny falling stories. Everyone falls eventually.

Soloist vs Corps de Ballet Interviewer: Which is harder: being a soloist or in the corps de ballet? Renata: Corps de ballet is harder because you must keep the formation perfect. As a soloist, any mistakes are solely on you, but there’s no one else to blame.

Stretching and Flexibility Interviewer: You stretch a lot. Why do you continue to stretch so much? Renata: It helps keep my muscles elastic. Stretching improves range of motion and prevents injuries. I tell my students to stretch so they don’t face the same issues I did.

Your Goal Interviewer: What is your main goal? Renata: I have a box for all my roles. My dream is to keep adding to it with exciting new roles.

Favorite Role Interviewer: What’s your favorite role to perform? Renata: I enjoy all roles, but Juliet in Romeo and Juliet stands out. The story, the character’s emotional journey, and the three acts make it unique.

Pre-Performance Ritual Interviewer: Any special pre-performance rituals? Renata: I don’t have anything special. Before emotional roles, I hold back my emotions during rehearsals to save them for the stage. Nervousness is natural and helps keep me sharp.

Post-Performance Relaxation Interviewer: How do you unwind after performances? Renata: I’d love to rest more often, but it doesn’t always happen. I use compression pants and a vibrating massager. I also enjoy taking baths, visiting the spa, and eating delicious food.

Talent vs Hard Work Interviewer: In your opinion, how much is talent versus hard work? Renata: Talent is important, but hard work is 90% of the equation. Even if you have talent, you won’t succeed without effort.

Advice to Aspiring Ballerinas Renata: Work hard, listen to your teachers, and embrace healthy competition. Competition in the studio can push you to improve, but outside of class, it’s important to maintain friendships and support each other.

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova#vaganova academy#mariinsky theatre#vaganova ballet academy#mariinsky#The Little Humpbacked Horse#mariinsky The Little Humpbacked Horse#mariinsky ballet#renata shakirova#Youtube

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would Agrippina Vaganova have a heart attack watching Nikolay Tsiskaridze girls exam?

Truthfully? No. Agrippina Vaganova was an innovator and might appreciate that NT is taking the old approach and adding something to it, just like she did. Vaganova herself said ballet was bizarre, and the NT exam was definitely mental. In addition, Agrippina Vaganova had an obsession with allegro rather than adagio, and she never spoke of legs going higher than 135 degrees. That said, she might mourn the loss of precision and tight fifths. However, if you look at videos from back in the day, they weren’t nearly as technically advanced as we are today, by default AV would still be impressed. She might not love the lack of aplomb and épaulement- I also don’t think she would appreciate (from a pedagogical standpoint) the complicated choreography and the music choice, as it lacked the precise tempo required to learn musicality. She would criticise NT as teacher because the exam showcased overly complex choreography and music which compromised his students' ability to demonstrate foundational technique, and thus, compromised their learning.

Controversially, she would appreciate that NT did not have all the girls perform every exercise. He did not make some girls do cabrioles (the hardest and most dangerous jumps) because he said he valued their health and did not want them to get injured for the sake of performing the jumps. AV would approve of this; she herself wanted ballet to be healthy and spoke at length about what teachers should do to prevent their students from getting injuries and to teach "pas" only when students were absolutely ready for them.

You know who I think had a heart attack watching that exam? The beautiful Altynai Asylmuratova. She probably lost ten years of her life watching that exam.

#ballet#russian ballet#vaganova#vaganova method#vaganova academy#elegantballettalk#elegantballetalk#Altynai Asylmuratova#Agrippina Vaganova

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today’s watch:

Figure skater Kamila Valieva with Olga Smirnova, Bolshoi Theatre, oct 2021

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova academy#vaganova ballet academy#Bolshoi theatre#Bolshoi ballet#figure skating#olga smirnova#kamila valieva

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have video's of Sofia Valiullina debuting Gamzatti at Komi opera? nobody's posting!!

Look at Sofya going for a more normal Italian Fouettés tempo! 14 april 2025:

in 2022:

youtube

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova#komi opera ballet#La Bayadere#Bolshoi ballet#mariinsnky ballet#sofya valiullina#sofia valiullina#kimin kim#gamzatti

13 notes

·

View notes

Note

Thank you for your balanced take on Tsiskaridze’s classes. This is just a rambling collection of thoughts I have in response to you and the other commenters:

I actually agree with you that Russian dance in general is having problems with slow pace, so an injection of speed can have some benefits.

I also absolutely agree that it is structured like a Bolshoi exam. Something I have noticed is that the dancers in the few Bolshoi exams that have been put online always look less polished/artistic than the Vaganova exams - this often perplexes people used to watching Vaganova exams online, but clearly it doesn’t hold the dancers back once they reach the theatre. You could argue that actually 18 yr olds shouldn’t be expected to have the artistry of professionals, that is something they can gain as they grow!

However, I saw a comment on the last exam videos which keeps coming back to me - these girls auditioned for the Vaganova and have been working away there for as much as seven years, presumably with the expectation that they would come out looking like Vaganova dancers. Even if they are well-trained and employable, the fact that they haven’t been taught the full style feels like a bit of a betrayal.

but actually, thank you all for interacting and participating with me on this page! yes, I do always try to look at strengths and weaknesses, things I like, and things I dislike. I remember when his exam dropped last year, most of the Russians were complimenting the exam, while calling the girls overweight (absurd😂) while most of us westerners were criticising the exam while calling the girls healthy and strong. I do remember thinking all the criticism was a bit too much, that the exam did have some really good qualities, while missing others, but I remember it to be “interesting”.

I am liking the direction of a faster tempo and no legs at 180 degrees, I think that’s almost old school, and if done properly with musicality the result is incredible. I do not love the obsession with pointe shoes. I do not get it! (But I did see a clip of a girl absolutely doing the best hops en pointe I’ve ever seen in my life). My personal opinion is that pointe shoes should be worn at the barre and at the centre only if the person is not rehearsing later and does not have access to many ballet classes—which is definitely not the case in the Vaganova—so I find it cruel and tiring, but at the same time, there are some aspects of pointe which are easier than being on flat, so except for the pain, perhaps there are advantages. I do think it’s a pity to do jumps in pointe, because they are less beautiful, but it is more realistic and functional to do them in pointe.

now, about the experimental barre: the truth is I don’t know if NT is following a methodology or if he’s just creating those combinations for aesthetic purposes. If it’s just for aesthetics I would hope that his class work is normal, and then he choreographs interesting exercises for the girls purposely for the exam. If there’s a methodology behind them, I’m so interested to learn about it and decide for myself.

what you’re saying about the Vaganova style is so interesting, I hadn’t thought about this betrayal. But I think you can take consolation in a couple of things, firstly is that they’ve been trained in the pure style for six years: that amount of training is just not going anywhere. Secondly they will continue to be trained with the best teachers once they join a company, so they will keep learning and honing their craft. Thirdly, I will never forget NT saying that he took on a weak class, so somehow I think they thought it would be okay to “experiment” on them because they would have been left in the shadows regardless, so they might as well try something with them. Ethically very shady, but perhaps the girls are grateful for this different type of training. Most of them are also physically shorter than the average Vaganova graduates, so I’m sure they appreciated working on things which suited their body type rather than forcing themselves into an aesthetic and mold that wouldn’t be kind to them. I did like what NT was saying last year that not all girls should do all the jumps, because some jumps are dangerous and if somebody isn’t ready to do a particular jump she shouldn’t risk an injury for the sake of doing it. Let’s see if this year everybody was ready for everything. Lastly, I do think that if they want to they are fully proficient in that Vaganova style, but for the exam’s purpose they are exhibiting other qualities. But I do think that they do look Vaganova, not Vaganova adagio (I mean, we haven’t seen them really do one) but I do think the arms , wrists and fingers are in the St. Petersburg style, (while some things really are not) but, if given the chance to display those vaganova qualities I’m sure they would be as proficient as the other graduates. And at the same time I do not think that Vaganova academy should just produce only Maria Khoreva style of dancers, what I think they excel at is creating dancers which are company ready on graduation, while in other schools they usually need some years before being at that level. I do think that even the “worst” in any Vaganova graduation class could pull off soloist roles fresh out of school while other schools tend to have less consistent high results.

Of course these are all personal opinions and conjectures, and just based on the clips, a better opinion will be formed when we have the full exam, but for now, this is what I think, let me know!!

thank you again for your post, I really love to have these kind of conversations

#ballet#elegantballetalk#elegantballettalk#russian ballet#vaganova method#vaganova academy#vaganova ballet academy#Nikolai Tsiskaridze

13 notes

·

View notes