#with exception of two years、one of which was ancient/prehistory and the other was world history

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

shout out to my college World Cinema class for teaching about argentina's dirty war. they definitely did not teach about that in gradeschool

#grade school history class was... severely lacking and repetitive.#literally every year would switch off btwn pre/early american continent colonial history and then indigenous cultures from the same period#with exception of two years、one of which was ancient/prehistory and the other was world history#(though world history only lightly grazed over things and a lot of the WORLD stuff was optional and the european stuff was not)#so. :/#and i feel like almost none of the classes went into as much detail as they should have :/#the class i took when i was like 12 wasn't too bad tho.#it went into detail about how all the indigenous tribes in my region got their land taken/rights taken away/etc and colonization#that one actually went into a lot of detail and had a lot of like. 1st hand accounts of treaties and stuff#but anyways.#overall pretty lacking#and the Dirty War? definitly never even mentioned. amongst various others.#unityrain.txt

1 note

·

View note

Text

Some non-Americans in the notes seem confused about how our history classes are structured so I thought I'd throw in my two cents.

First of all, standards are set at the state level (it's more complicated, I'm simplifying a little) but actual implementation is left up to the school district. The school district is in charge of choosing textbooks, teacher training, lesson plans, school day structure, things like that. Basically no two schools are going to be exactly alike in what and how they teach, even within the same state.

That said, my personal experience with a rural Arizona school district in the 00s and 10s was this:

Elementary school (kindergarten-fifth grade, about ages 5 to 10): All subjects are taught by one teacher, so there's no "history class" per se. History topics are taught in a way that ties them to something else happening in real life or in the classroom, such as teaching about the the Revolutionary War near President's Day or about Isaac Newton right after doing a science experiment. In fourth grade, we had a huge unit about the Conquistadores; in fifth grade, we did a whole quarter focused on World Wars 1 and 2, including reading an abridged version of The Diary of a Young Girl.

Middle school (6th-8th grade, about ages 11-13): Subjects are taught by different teachers in different classrooms, so "classes" become distinct and stop bleeding into each other. Classes were still strictly separated by grade (except for math). I didn't attend 8th grade but 6th and 7th had two different history classes: World History and American History.

6th grade World History focused on ancient and classical history and mythology in Europe and Asia in the first semester, and Medieval Europe and Mesoamerica in the second.

7th grade American History went chronologically from Jamestown to Watergate, except for major anniversaries (eg 9/11, which all of us remembered; the Challenger explosion).

High school (9th to 12th grade, about ages 14 to 18): Classes are now no longer restricted to specific grades; you can take them in whatever order (mostly) and still graduate on time. Required for graduation was at least three credits of history or civics, and I took four: World History, Arizona History, AP US History, and AP US Government and Politics (civics).

World History: Once again focused on ancient history, but this teacher went purely geographically instead of doing a vague timeline and bopping all over. Squeezing the Indus Valley Civilization, the emergence of Buddhism, and a brief discussion of Ghandi all into five classes labelled "India" didn't work for me personally but I can see why he did it.

Arizona History: Focused on our state. Went from early prehistory to present day.

AP US History: Began with the establishment of the Iroquois Confederacy, skipped straight to the Revolutionary War, and then went on chronologically until the Civil Rights Movement in the 60s. Even more than all the other classes, AP classes are designed around test-passing and the Civil Rights Movement was the last thing on that test chronologically. After the test in April, we chose an individual topic for a project to work on relating to US history between 1950 and the year 2000. I don't remember what I chose, but someone else chose Watergate and I remember my thoughts about it, haha.

Edit: Whoops, hit post too soon.

We also didn't only learn history in history class: it was kind of baked into English, too. When we read Shakespeare, we learned about Elizabethan times; when we read The Crucible, we learned about McCarthyism; when we read To Kill A Mockingbird, we learned about the antebellum South; when we read The Great Gatsby, we learned about the 1920s; and so on. A lot of my history knowledge doesn't come from history class at all, but the more in-depth looks in from English!

Through my public school education in the '90s and early '00s, our US history classes always ran out of time at the end of the year, somewhere around the '60s civil rights movement. We usually had enough time for a rushed, incomplete, confusing explanation of the Vietnam War. We never learned about Watergate or the fall of the Berlin Wall or Reagonomics or the Gulf War. They were in our history books, but we never got to that part.

It terrifies me to wonder what era history classes end on now. Do they make it past the Cold War era now? Past 9/11 and the War on Terror? Or are young folks today entirely uneducated on the horrific Islamophobia and civilian slaughter that occurred at the beginning of this millennium?

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Before Conan the Barbarian, There Was Bran

By Adrián Maldonado

I write about medieval barbarians in my legit academic work, and use this blog to explore how they occasionally escape from our powerpoint slides into the public consciousness.

I recently realized that for all my degrees, I didn’t know a thing about one of history’s most famous barbarians. It was high time I looked up Conan.

Stock image of Dark Age Europe

In my 80s childhood, Conan the Barbarian was a kind of folk character – a stock image of a beefy white guy in a furry loincloth with a giant sword. (I would probably be picturing Conan the Librarian, to be honest.) But I already had He-Man in my life, a knock-off Conan cartoon made to sell toys, though I could not have known that because the cartoon was so unspeakably awesome it would brook no questioning. Indeed, I only discovered the Schwarzenegger Conan films later on, when I was old enough to realize he had made other weird, non-science fiction films back in the Reagan era. I knew vaguely that the character was based on a book, or was it a comic book? This was before the internet, and before I could ever give a shit about a character with no good action figures.

Flash forward twenty years or so, when I am a grizzled Xennial hunched over his computer, writing about depictions of the Picts in pop culture. Immersed in terrible filmic depictions of ancient Scottish warriors (always warriors), it struck me that I had never thought about Conan the Barbarian. What kind of barbarian was he meant to be? Did his story take place in some kind of historical epoch? Were there Picts in it that I could add to my list?

Imagine my shock when I did find a Pict down this rabbit hole (or souterrain?), and he looked like this:

Whatever else I was working on, stopped.

***

Robert E. Howard is best known today as the creator of Conan the Barbarian. But little did I know that he was one of the first pop culture appropriators of the Picts. Indeed, he was writing about the Picts long before he even conceived of Conan. The Picts were his muse. I feel like this is important, and I may need more than one blog post to say why. But first, an introduction.

I had seen some hilarious renderings of Picts over the years, but they always fell into the usual stereotype of tattooed maniacs hurling themselves onto Roman spears.

Tattooed maniacs hurling themselves onto Roman spears (source)

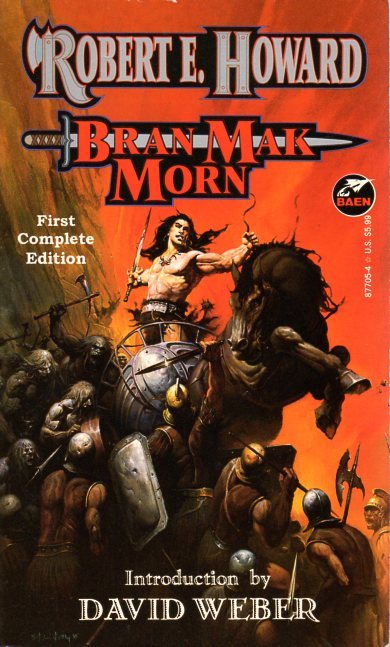

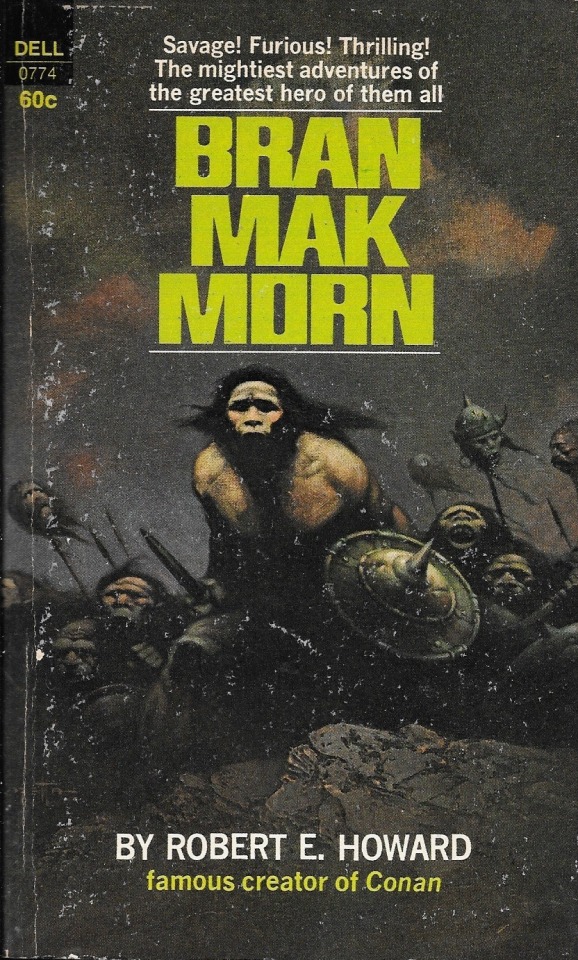

This 1960s paperback collection of stories by Howard entitled Bran Mak Morn, apparently the last king of the Picts, depicted this king Pict as a Neanderthal surrounded by howling ape-men. To me, this seemed like the purest distillation of the idea of the barbarians beyond the wall as sub-human, a trope developed in Roman imperial propaganda and continually reproduced today by the Hadrian’s Wall heritage ecosystem.

The paperback was one of a series of reprints of Howard’s genre-defining pulp fantasy of the 1920s and 1930s, brought back to life in the wake of the Tolkien wave of the 60s. Closer inspection revealed that Frank Frazetta’s 1969 cover image bore little resemblance to the description of Bran himself in Howard’s tales, even if his Pictish ‘race’ was certainly of a simian variety. More on this presently. What I wanted to know first was how a Texas kid learned about the Picts in the early 20th century, and came out with this.

***

Robert E Howard had a tough childhood in his native Texas. Coming from a broken home, he moved around a lot and read books to keep himself company. In 1919, at the age of 13, his father dragged him to New Orleans while he took classes, so he squirrelled himself away in a library on Canal Street. It was there that he first read about the Picts in a book about British history. The image of a little, dark race from the north that hassled the Romans but could never be conquered fascinated him. Perhaps due to the ray of light this book gave him at a sensitive point in his childhood, the Picts remained ingrained in his mind for the rest of his short life, which he would later take in 1936, at the age of 30.

Like many other nerdy kids, he wrote stories to pass the time. In his archive were found several early writings which reveal the impact the Picts had on him. There is a school paper from 1920-23 about the Picts. The first story he ever submitted for publication was about the Picts, ‘The Lost Race’, but it was rejected by the editor of Weird Tales in 1924. He sold his first story later that year, beginning his professional writing career. A revised version of ‘The Lost Race’ was finally published in Weird Tales in 1927, introducing the world to Bran Mak Morn, a Pictish king who fought the Romans. He would go on to make several more appearances in Howard’s swords-and-sorcery tales, and the Picts eventually became one of the myriad ‘races’ in Howard’s Hyborian Age, a proto-prehistoric shared universe inhabited by Conan the Barbarian.

Bran Mak Morn by Gary Gianni (source)

Howard’s Picts are a peculiar bunch. From his first essay on them, he describes them as the remnants of the stone age inhabitants of Britain, comparing their appearance to Native Americans. In this view, they were the ‘Mediterraneans’ (as opposed to Celts or Nordics) who first brought the knowledge of farming to Britain in the Neolithic. They were eventually swept aside by the fair-skinned ‘Celtic’ race of metalworkers, at which point they were forced to mingle and interbreed with the indigenous cavemen, a barely human simian-like race. This meant that by the arrival of the Romans, the Picts had become stunted, swarthy, long-armed ape-men. All except Bran Mak Morn, their king, who had kept his bloodline pure. All pretty disgusting racial logic now, but hey, so the argument goes, it was the 20s.

Except that here it was, unfiltered and raw, in a book released during the height of the civil rights struggle in the United States. I bought this ancient artefact off of Amazon for pennies, and holding it in 2017, it felt like I’d acquired an illicit antiquity. Plenty of writers have tripped over themselves to call out and defend Tolkien and Howard regarding the racial (if not always racist) component to their mythical prehistories, so I won’t go down that route just now. But that cover image haunted me.

***

In 2005, Bran Mak Morn received a brand-new edition, the Weird Tales stories now bundled with unpublished manuscripts, fragments of Howard’s correspondence, and critical essays by Rusty Burke and Patrice Louinet. Armed with an annotated timeline of Howard’s Pictish writings, which spanned his career, and supplemented with google-fu, I was able to clarify the genesis of Bran Mak Morn.

Former Canal Street public library, New Orleans, 1911 (source)

It is possible to trace the public library Howard visited when he was 13, when he first encountered a British history book and his vision of the dark, prehistoric Picts. The Canal Street public library in question must be the one that formerly stood at 2940 Canal Street at the corner of South Gayoso, opened in 1911. A photograph survives on the New Orleans library website, and Google Maps reveals it is now a Yoga studio.

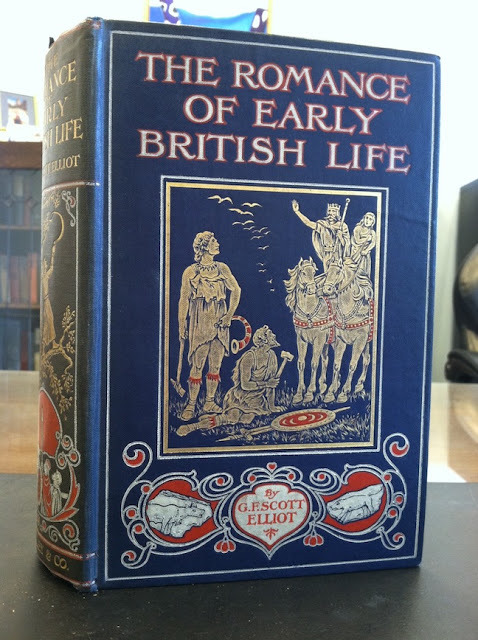

Origin myths of the Picts (source)

Rusty Burke has also plausibly identified the very book that Howard seems to have read: The Romance of Early British Life (1909) by George Francis Scott Elliot. This is apparently one of the flashy, pulpy ‘Library of Romance’ published by London-based Seeley and Co, described as ‘profusely illustrated’ ‘gift books’, which included among their number volumes such as The Romance of Modern Mining and The Romance of the World’s Fisheries. The author Scott Elliot was a botanist and antiquarian, president of Dumfries and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society during an apparent low point in its history.

The fairly ridiculous book in question seems to have been written for Edwardian teenage boys, and does indeed bear the DNA of Howard’s later writing on the Picts: “In very ancient times Britain had been twice conquered, first by the small, dark Picts of the Mediterranean, and later (about 2000 or 1000 B.C.) by the tall, brown-haired, Gaelic-speaking Celts (237).” The chapter on the introduction of farming to Britain is called ‘The coming of the Picts’, in which Scott Elliot explains that they have been called by several names before – Homo Mediterraneus, Basques, Iberians, Silurians, the Firbolg, the Dolmen-builders – but he calls them Picts to save on ink (80-1). He claims they are still readily identifiable in the present day, as the short, brunette people who are mostly found in towns and cities, unlike the fairer Teutons or Kelts who prefer the countryside (92-3).

Howard’s vision of the Picts was thus formulated by the equivalent of our contemporary public archaeology, an accessible potted prehistory of Britain by one of Scotland’s leading antiquaries. Why this particular image, of a dark, forgotten people without a history, resonated so deeply with him, is a subject to ponder. But he was clearly not alone in his fascination. While racial views of the past soon died out in archaeological writing, they would go on to have a tenacious grip on the fantasy world. And which of these two genres do you think has a greater influence on people’s image of the medieval past?

***

Why does any of this matter? It is a demonstration of the role of ‘the Picts’, in various guises, as the untermenschen of what you might call western folk history. The fact that a young boy in inter-war Louisiana could head to the nearest library, read about them in a cheap history book, and then build a world-beating fictional universe that is still beloved today based on this is remarkable. As I’ve spent some time documenting on these pages, that image of the Picts is still in a way with us. A recent article in the Glasgow Herald has the reporter coming to the shocking insight that the Picts were not ‘hairy savages’ after speaking briefly to a couple of scholars. I wonder if that means we are doing our job well, or terribly.

It also opens up questions about the central role of race at the origins of both archaeology and the fantasy genre, a sticky subject that will have to be the subject of future blog posts [Editor's note: now read the follow-up to this post]. In the meantime, go check out similar topics being covered over on The Public Medievalist.

And hey, why not donate to your local public library while you’re at it?

***

Follow us on @AlmostArch

Header image via Jeff Black

5 notes

·

View notes