21, He/Him | Interested in biology, ecology, and worldbuilding | Working part-time at a taxidermy studio

Last active 4 hours ago

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

One of the most talented abstract artists I know of! Every detail suggests so much meaning and function, but completely untethered from reality, I love it.

#Abstract #art #matrix #tree #computer

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanted to paint something, so here’s a largemouth bass. I see them pretty frequently while snorkeling, but it’s always exciting anyways.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

As long as there's enough moisture and dark spaces to hide in, Scuttlebugs will thrive on next to nothing. They will scavenge almost any organic matter, including paper and bone, under the cover of darkness when they roam in blinding bursts of speed. By day, they avoid hungry predators and the drying sun by wedging themselves into the narrowest spaces that will hold their flattened bodies. As they are only two centimeters long excluding their long antennae and cerci, this can mean almost anywhere.

Their lungs lose water rapidly in dry conditions, so they are not common household pests, but they are abundant near or in water, able to breathe equally well in oxygenated water and moist air. They even tolerate saltwater, and intertidal colonies can grow massive feasting on low-tide scraps. Most poisons don't harm them either, not to mention nuclear radiation, the resilient little Germites continuing their humble feeding under conditions that would kill most animal life. Reproduction is a simple affair, females mating before laying a clutch of pearly eggs in a moist, protected space. The hatchlings resemble miniature adults, and live among adults as they go through a handful of molts to reach adult size.

Their germ bodies emerge from their undersides, and are easily mistaken for juveniles, with a pair of filaments on either end. These race along the substrate in bursts, searching for host Germites.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please don’t skip taking a look 🙏🥹

I am Eman from Gaza, 29 years old. I stand before you as a human being trying to protect her children. I am married and a mother of two children: waleed, 8 years old, and Layan, 5 years old.

We live a life filled with fear, hunger, and displacement. We have been displaced seven times and are now in the Mawasi area of Khan Younis, south of Gaza. It is difficult for me to describe what we face daily in Gaza: no food, no drink, no medicine, oppression, helplessness, psychological pressure, doubt, and daily trauma due to the loss of loved ones in Gaza.

The crossings are closed, prices are high, the stones have become more severe on us, we have not found food in the markets to eat, my children are suffering from a shortage of food, the situation here is absolutely catastrophic.💔

Now, I find myself in this difficult situation. I humbly and strongly ask you to help me save my children's lives. All we want now is to buy them some food, due to the high prices and the closure of the crossings.🍉

Please help me to provide food for my children and save them from the famine we are living in.

Your help will greatly help alleviate our suffering. I hope you will share my story with your family and friends.

Thank you to everyone who stands by us and helps us during this difficult time we are going through.🤍🥹

@sayruq @sar-soor @90-ghost @gaza-evacuation-funds @hella-gross @gxrlfxg @bubmyg @fifthnormani @ankle-beez

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

The initial sketch was very much based on Hibbertopterus, and it's where a lot of my enthusiasm to write it up came from, so it is biased toward that body plan. That said, I tried to consider alternatives, and I think long limbs like a coconut crab might struggle to hold such a large animal in a sprawl. Now, if it had a more erect posture, I'd probably have gone that direction, which is an interesting idea.

Giant spiders, by which I mean like human-sized, are really common in fiction, so I got to thinking about how one would actually look. I referenced arthropods that actually achieved this kind of mass in the paleozoic, especially hibbertopterids. A lot of these giant bugs existed when oxygen levels were unusually high, and it does seem that oxygen is a limiting factor on the size of insects, but the very biggest arthropods weren’t insects, and some of them existed before or after the highest oxygen levels. What I’m getting at is that maybe only insects are limited this way, and arthropods that breathe differently could get huge even at present oxygen levels. Of course, they don’t, but that may have to do with competition with vertebrates, or being unable to keep up with faster-paced nutrient cycles.

So let’s say this giant spider lives on an isolated landmass, or in an alternate timeline, where vertebrates aren’t a problem, and ecosystems move slowly. It’s descended from tarantulas or related spiders that exclusively use book lungs to breathe, unlike most spiders that also have insect-style spiracles and tracheae. To efficiently move that oxygen to all of its tissues, it’ll use copper-based hemocyanin like a horseshoe crab, making its blood bright blue. The sprawling posture of a spider isn’t the best at bearing 100 kilograms, so its legs are short, and attach close to the midline of the body. The abdomen rests partially on top of its carapace to help support its organs. Being so bulky, and having a slow metabolism, it can’t sustain high activity, so actively chasing prey won’t work. But its caloric needs are also high enough that sitting in a burrow and waiting for food to come along is risky. Instead, it slowly roams like an eight-legged tortoise, “grazing” on whatever is too slow or oblivious to get out from under it as it rummages in the leaf litter and soil of damp forests with shoveling forelimbs. Insects, worms, snails, carrion, even fruit, all get shoveled between its grinding maxillae, mixed with saliva, and sucked up into its stomach. This kind of small prey is most abundant near water, so I imagine they would be shoreline animals.

Another struggle giant arthropods face is molting. It’s a long process, and it takes even longer for the new exoskeleton to harden. This giant spider would dig a burrow to molt in, and then remain dormant underground as its exoskeleton fully tans. It would emerge from its den weeks later, ravenously hungry, like a bear after hibernation. Lastly, sexual dimorphism is often more extreme in larger animals, so the males of this species would hardly grow bigger than the largest real spiders. They would still ambush prey from burrows like the ancestral tarantulas, but would also go on long journeys to find female partners. Like real tarantulas, once a male reaches adulthood, the sexual organs on its pedipalps prevent it from safely molting again, capping their lifespan at around 10 years. The females however are so large that they take 20 years just to reach maturity, and can live past 80.

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Every activity is a social activity for a Wryling. These handsome little, starling-like germites live in huge flocks, maintaining individual relationships and reputations with dozens of others. Precise etiquette is observed, with subtle differences in call and posture carrying great significance.

They feed mostly on the ground, the flock organizing itself by hierarchy and familiarity as they pick for insects and seeds. Much of the rest of their time is spent preening, keeping their silky black plumage clean to contrast with their pale masks, as well as preening their close companions to maintain bonds. Even in the air, they coordinate so tightly that they become a graceful, seamless mass of hundreds or thousands. Nesting is done colonially as well, the flock choosing a cliff or tree to build their nests in. They pair off for the season, and the couple cooperate to weave a nest of twigs and grasses, brood eggs, and keep their helpless nestlings full.

Wryling germ bodies are shed during their frequent preening sessions, resembling white feathers that dance gracefully through the air, as though blown on the wind.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A quick painting I did for an art trade with my sibling. I miss the sea.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Giant spiders, by which I mean like human-sized, are really common in fiction, so I got to thinking about how one would actually look.

I referenced arthropods that actually achieved this kind of mass in the paleozoic, especially hibbertopterids. A lot of these giant bugs existed when oxygen levels were unusually high, and it does seem that oxygen is a limiting factor on the size of insects, but the very biggest arthropods weren’t insects, and some of them existed before or after the highest oxygen levels. What I’m getting at is that maybe only insects are limited this way, and arthropods that breathe differently could get huge even at present oxygen levels. Of course, they don’t, but that may have to do with competition with vertebrates, or being unable to keep up with faster-paced nutrient cycles.

So let’s say this giant spider lives on an isolated landmass, or in an alternate timeline, where vertebrates aren’t a problem, and ecosystems move slowly. It’s descended from tarantulas or related spiders that exclusively use book lungs to breathe, unlike most spiders that also have insect-style spiracles and tracheae. To efficiently move that oxygen to all of its tissues, it’ll use copper-based hemocyanin like a horseshoe crab, making its blood bright blue. The sprawling posture of a spider isn’t the best at bearing 100 kilograms, so its legs are short, and attach close to the midline of the body. The abdomen rests partially on top of its carapace to help support its organs. Being so bulky, and having a slow metabolism, it can’t sustain high activity, so actively chasing prey won’t work. But its caloric needs are also high enough that sitting in a burrow and waiting for food to come along is risky. Instead, it slowly roams like an eight-legged tortoise, “grazing” on whatever is too slow or oblivious to get out from under it as it rummages in the leaf litter and soil of damp forests with shoveling forelimbs. Insects, worms, snails, carrion, even fruit, all get shoveled between its grinding maxillae, mixed with saliva, and sucked up into its stomach. This kind of small prey is most abundant near water, so I imagine they would be shoreline animals.

Another struggle giant arthropods face is molting. It’s a long process, and it takes even longer for the new exoskeleton to harden. This giant spider would dig a burrow to molt in, and then remain dormant underground as its exoskeleton fully tans. It would emerge from its den weeks later, ravenously hungry, like a bear after hibernation. Lastly, sexual dimorphism is often more extreme in larger animals, so the males of this species would hardly grow bigger than the largest real spiders. They would still ambush prey from burrows like the ancestral tarantulas, but would also go on long journeys to find female partners. Like real tarantulas, once a male reaches adulthood, the sexual organs on its pedipalps prevent it from safely molting again, capping their lifespan at around 10 years. The females however are so large that they take 20 years just to reach maturity, and can live past 80.

#art#creature design#digital art#spider#giant spider#spec evo#spec bio#speculative biology#tarantula

460 notes

·

View notes

Text

Awkward starling interaction I recently saw.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

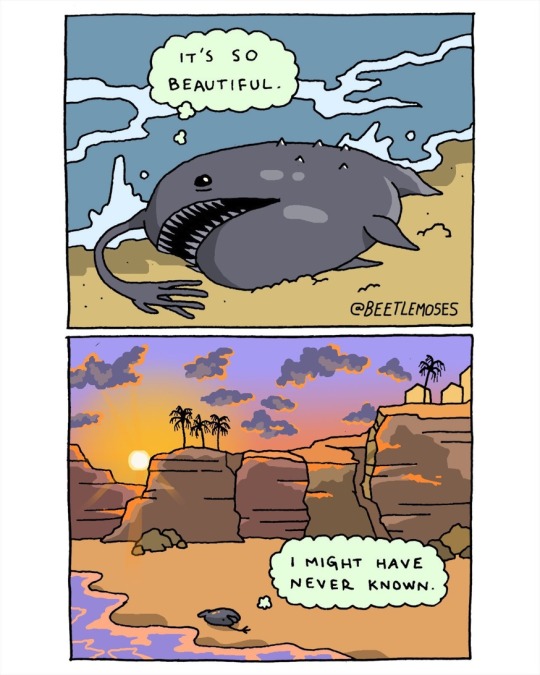

This comic makes me so stupid emotional. She might have never known.

103K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was asked for some exploratory sketches for a tattoo design, and they came out really neat.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have crazy news for you. Tarsiers aren't even lemurs, they form a clade with monkeys that true lemurs are outside of. Which means we're more closely related to this freak than either we or it are to lemurs. Evolution is chaos.

Hey

LEMUR. You thought of a ring tailed lemur or something, didn't you 🙄

The first time I ever learned what a lemur was, it was in a kid's book that used a photograph of a tarsier as the example, and it didn't even specify this was just one kind of lemur or anything. It just said "LEMUR" under tarsier picture.

So even after learning about other types of lemurs I was under the impression that "the" lemur in everyone's mind was this thing:

I have never shaken this. This extremely thing of an animal remains my world's default lemur. Why isnt it yours. What did he do wrong.

237 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anywhere in the world that one can find shallow, sheltered waters that don't freeze over, they will likely find colorful schools of little Millifish. It is not uncommon for these to teem with tens of thousands of individuals, and yet no two of them are the same. Every single Millifish possesses unique coloration, partially inherited, but effectively limitless in potential variety. In waters that they share with their many predators, mottled, camouflaging tones favor survival, and so these individuals are most common. However, rainbow-barred and piebald and solid black and every other description are mixed among them, finding safety in close proximity to their countless schoolmates.

When not among the cover of aquatic vegetation or river rocks, Millifish stick close to each other for shelter, creating very cohesive schools that can resemble a seamless, round, multicolored mass. They tend to spread out more while feeding, pecking at tiny invertebrates and algae, but will quickly consolidate into a blob again when trouble is spotted. When food is abundant or the water warms, males and females alike compete for partners in the school. After pairing up, ideally with a large and persistent mate, the female adheres her sticky eggs to a sheltered surface, and the male fertilizes them. He remains to guard them until they hatch in a few days, after which the fry only have each other for safety, taking several months to reach maturity.

Millifish germ bodies are vaguely fish-shaped themselves, silvery and reflective, and tend to aggregate into masses as they cruise around in search of hosts.

194 notes

·

View notes

Text

It's really cool to hear more about this, especially having gone through something similar with my own art. There's no standard we're being held to, so why not make art in the most engaging, enjoyable way we can? People appreciate having it shared with them all the same.

Today's church notebook doodle is a family of Mermares fleeing from a predatory Akhlut. The stallion's elongated flippers are raised in defensive posture, ready to whip back and hit the giant marine dog in the face if he gets too close.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reminder that turkeys are not just food, they are amazing animals. Huge grouse that can easily hit ten kilograms, and are still capable of hauling all of that weight several meters straight up into the air at split-second notice. It is a genuinely astonishing display of power, they are fantastic fliers, just not over distance.

It's just crazy to me that so many people in North America live with these gorgeous, fully volant, dog-sized dinosaurs, and we consider them mundane. So today, I'm thankful for turkeys.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

How could I have gone this long without learning that there are value-size antlions. I love them so much. I want to keep one in a sand garden.

Giant Antlions (Palpares immensus): these enormous antlions have been known to attack geckos and other small reptiles

The images above depict the larval stage of Palpares immensus, which is one of the largest antlion species in the world.

This article provides more information about the unusual behavior of this species:

The larvae live freely in sand and are ambush hunters. They are voracious predators and feed mainly on other arthropods, but have been known to attack geckos and, in one case a small adder. They are unable to feed on these reptiles and usually die as a result of not being able to extract their jaws from the vertebrate prey.

These antlions can be found in sandy, arid environments throughout southern Africa.

The adult form of Palpares immensus is also depicted in the images below:

Sources & More Info:

Biodiversity and Development Institute: Palpares immensus

Global Biodiversity Information Facility: P. immensus

Animal Life: Giant Antlion Larva

What's That Bug?: Uncovering Antlion Habitats

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Three figures from recent dreams. Each had a feeling of almost prophetic significance attached to it.

First, one of what may have been a pair of deities. I remember photos of stormy, summer skies from both the midwestern US and Wales, so similar that they seemed two halves of a whole. Riding in a car down a lonely, rural road in the midwest, twin bolts of red lightning struck the corn fields. Arcs of purple lightning momentarily formed the shape of a bestial figure, the red bolts flashing from its eyes, standing monumental before the gray-black storm clouds. As it was made of lightning, I only saw it for an instant.

Second, a many-headed swan I briefly glimpsed through a window, backlit in golden fog. I had been crawling on my stomach up to the window through an ancient stone hallway. The walls were stone pillars impossibly hovering just an inch or so above their foundations. I was filled with terror at what I feared would happen should I make the tiniest sound. It was not eerie fear of the unknown, but a certainty that if I was heard, I would die. But I still nervously anticipated what I would see through that window. I know the swan was not what I had expected.

The third, I think, requires some context. My family owned a white goose for some time, and though she was standoffish, she was well-loved. Unfortunately, she was killed a few years ago by a husky we hosted for a short time. In this dream, I was in my family's driveway after dark, and saw the goose standing there. I couldn't believe it. My mother and I talked to her in a trailer in the driveway, where she appeared human. It didn't even occur to me to question this. In this form, she was a slim, middle-aged, white woman with an arched nose and red hair. She acknowledged our confusion about her death by simply saying that she had "been away for a while."

5 notes

·

View notes