Studying Chinese coming from a background studying Japanese, so I'm likely to make a lot of comparisons to kanji (Chinese characters as used in Japanese).

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

youtube

Linguaflow Chinese is a new channel making lessons in Chinese with lets plays!

They're small, so if you comment they'll see your words and appreciate it. If you know any learners, maybe share thejr channel.

It's just a lovely little channel, and I hope it grows.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Not consecutive days

(but I'm getting there)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Chinese from Spam Texts

I got a very amusing spam text in Chinese this morning, so naturally I have to turn it into a vocabulary lesson.

生活洋溢甜蜜温馨,周末愉快,今天有什么安排呢? 看你没有回信息,你是在忙还是没有收到我的信息呢?

新词 Vocab:

洋溢 / yáng yì / brimming with

甜蜜 / tián mì / sweet

温馨 / wēn xīn / soft, fragrant and warm

愉快 / yú kuài / happy, pleasant, cheery

安排 / ān pái / plan or arrangements; to plan or arrange

信息 / xìn xī / text message; information

收到 / shòu dào / to receive

翻译 Translation:

Life is brimming with sweetness and warmth, happy weekend, what plans do you have today? I see you haven't replied to my message, are you busy or have you not received my message?

266 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vidioma.com: Chinese Comprehensible Input

Hi friends, so this site collects a bunch of comprehensible input video lessons from youtube: https://www.vidioma.com/

The site is free, and does not require you to login to use it. Another person learning Chinese made the website to collect lessons. It really is great. Start with the New Starter lessons if you have never learned Chinese before, or Beginner if you know a bit, or Intermediate if you're around ~B1. If you like any particular lesson, you can click it to go to the Youtube page of the video, and then follow that creator on youtube.

It has a counter for how many minutes and hours you've watched, but it just counts on the device you're using it on. So if you're trying to count time watched on that site, on your computer and phone combined, you should just keep your own track of time spent.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Winter break homework

English added by me :)

7K notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

I'm linking this because it explains how native speakers learn Chinese.

If one is doing Dreaming Spanish, or a method like ALG where they attempt to learn like a native speaker, this guide could be useful.

1. Toddlers before 3 years old can understand 50-100 words, some simple sentences

2. After age 3 they go to kindergarten and learn 300 common simple hanzi (looks like mostly picture-type hanzi like 水山日 etc). Start practicing how to write. Children memorize nursery rhymes, childrens stories, and songs. Reciting them, and seeing the hanzi to write them.

3. At 6 or 7 years old, children start primary school and have 语文课yvwenke class to systematically learn hanzi. So if you wanted to use a textbook children use then you could search "语文课" They learn pinyin in these classes, and hanzi. They also get lots of homework to practice writing - like writing each hanzi studied 10 times, for multiple days in a row for multiple characters. There is pinyin alongside hanzi in first and second grade textbooks, often nursery rhymes and short stories.

4. In 3rd grade, there's no more pinyin in textbooks, only newly taught hanzi will have pinyin marked. Aside from hanzi writing exercises, students will have make word exercises where they're given a hanzi and asked to make as many words as they can that contain it, and another exercise where they're given a word and asked to write a sentence that uses it.

5. By 9-10 years old, after 3rd grade, children can recognize 2000 characters, and write 1500 characters. Starting in 4th grade, the textbook reading material gets longer and more literary. Students begin to learn many idioms 成语, and some poetry and ancient chinese.

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

I started reading this serialized fantasy novel in Chinese called Twig 枝丫. It’s about trees growing in people and controlling them 😱 Very spooky and intriguing. It’s written by a student and specifically for intermediate learners. The Substack has vocab lists for each chapter and audio, which is amazing! The best part is that a new chapter comes out every Friday. I’m only on chapter 10 so far, so I’m not caught up yet. If you also want to read it, you can just look up the Twig 枝丫 Substack. I pasted the chapters into Pleco to look up words.

I’ve also been watching this show called Women in Taipei 台北女子圖鑑 and it’s really good. I feel like I can understand about 80% of it. Apparently it’s an adaptation of a Japanese show, so I might also watch it in Japanese. Oh wait I just looked it up, it’s an adaption of Tokyo Girl, which was the first show I watched in Japanese 😅

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word of the day:

鳥居 niǎojū / torii (gateway of a Shinto shrine) (orthographic borrowing from Japanese 鳥居 "torii")

My teacher kept saying this word cause we were drawing one in class, and I did put together what it meant through context, but I really expected it to be called something with a 門, you know?

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

I've done other posts about this (hopefully tagged under #chinese resources). If you're looking for chinese content, you can search in a search engine (google, duckduckgo), youtube, spotify, bilibili.com. also missevan.com, ximalaya (if you can make an account - i couldn't), other chinese podcast websites.

If it's easiest for you, just search on google.com or youtube.com

Youtube.com is good for finding comprehensible input lessons and podcasts. Good search terms to try: comprehensible input chinese, comprehensible input mandarin, mandarin podcast, chinese learner podcast, chinese listening hsk 4 (or type any hsk level), chinese conversation, learn chinese lessons, learn chinese podcast

Bilibili.com has the most materials I've found. The site will also start recommending similar things, so if you find a manhua with voice acting on there, it will recommend you more, which is nice.

Search terms to use to find things below. Note that if you click random sites with random letter/number names, have an adblocker or don't click the ads (I often use mozilla firefox because I have my phone mozilla firefox settings to block most ads). If you aren't comfortable looking through various websites for a show you want to watch online desperately in a language you know well, then probably stick to well known sites when you search (like youtube and bilibili). If you're used to hunting for stuff free online, go on any search engine and go wild. You can find nearly anything.

If you want to look for a specific type of material, I suggest you look up the term for that word in chinese (such as manhua for comic, donghua for animation, yousheng duwu for audiobook, boke for podcast) and then you can look up whatever you want. Look things up with all chinese words, and you'll find the chinese materials as results.

Most of the time, searching in google and youtube will work whether you type your search terms in pinyin or hanzi.

For audiobooks: youshengshu zaixian, youshengshu, yousheng duwu 有声书 在线,有声书, 有声读物

For finding novel text online: "novel name in chinese" xiaoshuo zaixian, "novel name in chinese" xiaoshuo zaixian yuedu,小说 在线,小说在线阅读

Once you find a novel you can paste the text into Pleco Clipboard Reader to use Pleco to lookup words, or paste the url into Readibu search to save the page as a novel inside Readibu.

For finding manhua: "manhua name in chinese" zaixian, "manhua name in chinese" kan zaixian, kan zaixian mianfei (free), manhua zaixian 在线,看在线,看在线 免费,漫画在线

For finding dramas: "drama name in chinese" kan zaixian (watch online), kan zaixian mianfei (watch online free) 看在线,看在线免费

For finding donghua: "donghua chinese name" donghua zaixian (yes all the search terms boil down to name+chinese word for the media type+online(在线),动画在线

For finding mandarin dubs of cartoons or shows: "title in chinese" 国语 配 guoyu pei, tai pei 台配 (taiwan dub)

For finding audio dramas: "audio drama name in chinese" 有声剧 youshengju, "name" yinpin ju 音频剧, youshengju zaixian 有声剧 在线

For finding downloads specifically: xiaxian 下线, if it's a novel then sometimes "txt 下线" or "epub 下线" works for finding downloads. Annas-archive.org and z-lib have a lot of chinese ebook downloads.

Bonus, do you want to watch something in a different language than chinese and just hoping a chinese site has it for free? Look up: "title in language you're looking for" zaixian, zaixian mianfei (online free). I did this to find Skins BBC online free. Note that the site may have chinese subs on the videos, which hey that could be good reading practice.

Another bonus: fuermosi is the chinese title of sherlock, if you search 福尔摩斯 on youtube you can find Granada Holmes tv show with chinese subtitles, and audiobooks of sherlock in chinese

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

So many thoughts on using audiobooks lol. Going through the HP audiobooks, if I relisten to an audiobook it becomes Obvious how much improvement is happening. I hear so many new details, very specific details, on a relisten.

But also I know the "listening difficulty" is increasing each book, because I do not notice the improvement as much when just going from one book to the next. Increasing difficulty is good though, if it's anything like how reading skill improves, then pushing up the difficulty of material I can handle ends up lifting the floor of "what feels easy" over time to higher level reading material.

I see very gradual improvement in comprehension from one audiobook to the next. For example HP1 I could follow the main plot on the first listen, HP2 I got lost sometimes about which scenes I was listening to - probably due to the increase in vocabulary/material complexity. I relistened to HP2 and understood both the main plot and a decent chunk of details, which was more than I understood HP1 (which was only the main idea and occassionally details). I get to HP3 and I understood both the main plot and a decent chunk of details on the first listen. So the first listen of HP3 felt as easy as the 2nd listen to HP2. I'm relistening to HP3 now, and understanding another decent chunk of details... so if before I was understanding 50% of the details, now I'm understanding 80% of the details or something. It feels like significantly more.

I am clearly getting benefit from the initial listen to an audiobook, even if my comprehension only feels like "all of main plot" (HP1) or "most of the main plot but not all" (first listen to HP2). Once I can understand "all of main plot and some details" it causes improvement to later be able to grasp More details of something at the same difficulty level. Interesting. So if I already know some context in advance, such as the plot from reading it in english, then just understanding "the main plot" of the audiobook eventually will result in improvement in understanding a lot more. That's the floor of what materials are useful.

I imagine, once I start using audiobooks I have no familiarity with, the floor of wha's useful will be things where I can follow at least "some of the main plot but not all." And ideally, where I can follow "all of the main plot" but not necessarily details.

For anyone emulating what I'm doing: I already had decent reading skills (someone who could read webnovels with Readibu or Pleco word-translation tools, and some simpler written webnovels extensively with no tools), and I am partially listening. As in, I listen while browsing the internet, working on spreadsheets and emails, doing grinding in video games, walking, doing chores, driving. I am not 100% focusing. I find, frustratingly, that 100% focusing I understand more individual words but I am translating in my head and I end up missing what's said right after any word/phrase I have to inner translate - which results in it feeling more exhausting and harder to grasp sentences as whole units of meaning. When I partially listen, what I manage to understand feels just as easy as listening to an english audiobook - I am not thinking super hard, I'm understanding quickly and not mentally slowing down, I can picture the scenes I hear. So on the one hand: if you did a lot of reading and translating words, listening at natural speed with partial focus could let you practice improving listening as a skill and not inner translate so much. On the other hand, my progress is proof partial focusing on audio can work for some people to improve listening skills.*

*Provided they have some knowledge of vocabulary like I did, from reading or anki or textbooks etc, even if it's not listening recognition of that vocabulary. I have no idea how well partial listening would work if you truly had no mental familiarity with a few thousand vocabulary already. Provided they could listen to something in their native language while doing other things - if you can't follow an audiobook or youtube essay in your native language when playing video games, doing chores, doing spreadsheets? Then it won't be doable in a language you're learning either. I often listen to some audio when driving, walking, doing chores, gaming, so I know how much I normally understand if I do it in my native language. I know when, in my native language, I'd tune out what I'm listening to and need to relisten - if I'm composing emails at work or spreadsheets with math, or trying to rewrite something then I can't focus on what I'm listening to, and don't try to listen at those times (or pause what I'm listening to).

Note: I do think similar activities, partial listening during activities when you know you could follow the main idea, with materials you can understand most/all of the main ideas (but not necessarily details) of, would work if you only knew 1000 words. Or even only 500 words, again provided you are listening to things you understand the main idea of (so perhaps learner podcasts or textbook audios). I think this activity has been helping a TON with listening skills, and I wish I'd done it sooner and more often.

Another note: if a listening material is too hard to understand the main idea of, you can look up words you hear that sound important to meaning. This will allow you to understand the main idea, if you look up enough words. Just like with reading, if you encounter a few key words a page that seem critical to understanding the main idea of what's going on. For myself, I try to limit myself to 5-10 word lookups or less per chapter or 4k words, per 20 minutes of listening. Just because if I start looking up more than 1 word every few minutes, I get burned out easily and no longer find it fun. Looking some words up though, if you don't quite understand enough of the main idea to learn from it, will give you enough information you need TO follow the main idea and then learn some stuff from the context of that main idea.

Relistening: I watched a video ages ago by a person learning korean about the value of relistening, of a LOT of relistening. They were right, honestly. I did not listen, let alone relisten, as much as the person. Any time I do relisten, I am reminded how absolutely useful it is. The more you relisten, the more prior context you have (from the last listen) of what's going on, so the more new details you understand and the more words you practice hearing. And practice hearing words is a skill that must be practiced! A lot! Relistening is one of the easiest ways to practice hearing and recognizing words faster. Since it's the same words, relistening to something you can predict more and more of, each relisten the words getting clearer and it getting easier to parse and recognize. I think the polymathy channel's video on using the nature method books first got me considering the use of relistening, but it was a different youtuber that really insisted on relistening 5-20 times to things.

(I wonder how much rewatching stuff as children helped some of us, I remember watching some movies 100-300 times, rewatching again daily, until the tape broke and I needed a new one. I must've practically had those movies memorized, even with my awful memory that ultimately forgot again lol, but I can imagine even at age 4-6 once I watched the movie SO much I understood most of every line. I rewatched movies every night as a little kid, just rewatching the same movie for months straight while I was into it).

All this said... if you do not know enough words to understand most of the main idea, and refuse to look up enough key words to understand most of the main idea, use audio-visual materials to practice listening. Especially audio-visual materials where you can follow the main idea based on the visuals. Like with comprehensible input lessons, cartoons for young children, some* shows you've seen before and know the story well enough that you can follow the main idea with the combo of visuals/prior knowledge/words you do know. For learning brand new words, I am finding audio-visual materials are much faster for learning words I didn't know before, and it's much more obvious what the words mean because I see visuals. Compared to when listening to audio only, and I can kind of guess the meaning of some new words... but if you read or listen to say "monsoon" for the first time you may guess it means something related to rain based on the surrounding sentences, if you see a monsoon visually while someone says "monsoon" then you have a clear meaning visually to attach to the word.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's suppose you want to learn Chinese mainly to read webnovels (or other reading material).

Now, personally, I recommend some study of pronunciation like pinyin, and watching some videos or reading some articles on tones and tone sandhi, grammar, hanzi and hanzi structure. Because at some point you'll probably want to listen too, speak too. So you know - use other resources to study the other skills! If you plan to do anything besides read eventually. Also, I think some pronunciation study actually helped me with remembering hanzi (the sound components in them) and reading skill.

But lets suppose you're studying mainly so you can read webnovels. Which is what I did in my first year. And you can set a goal to start reading webnovels within a year. For some people it takes as little as 3 months to start reading webnovels, for others like me it took around 6 months to start reading webnovels and 12 months to feel comfortable.

Download Pleco app and Readibu app. These apps will be your best friends. Pleco app is a dictionary tool so you can look up unknown chinese words, and it's Clipboard Reader area is where you can paste any chinese text into and then click-translate any words. I recommend the first time you look up any word, you press the dictate/speaker tool so you can hear how it's pronounced. You can save words in Pleco and study them using Pleco's built in SRS flashcards if you wish. Mainly though, the important part is using Pleco to look up words, read example sentences, and to use the Clipboard Reader area to read any Chinese text you find online. Pleco has an area to purchase graded readers, these will probably be some of the first things you read (if you choose to use paid resources). Readibu app is a click-translation Reader app for Chinese, you can browse the app for webnovels, or you can go to the Search area and paste in a url of a chinese webnovel, then Readibu will say it's not in the database so click 'search with Google' then you'll see the url as a result and click it, then bookmark the webnovel page in Readibu. From there you can click the open book icon on any webnovel, and it will make it just click-translate text and provide you the Readibu app features. Once you're reading a lot of webnovels, you may wish to use Readibu to read, for some people it will be more convenient than Pleco for going chapter by chapter.

Make a plan to start studying hanzi. I recommend you focus on the most common 1000-2000 chinese words, or the HSK 4 vocabulary, or both. The goal here is to get your vocabulary and hanzi recognition around HSK 4 level. I used this book (Tuttle Learning Chinese Characters: (HSK Levels 1 -3) A Revolutionary New Way to Learn and Remember the 800 Most Basic Chinese Characters) because it just clicked with me, I just read through it over a few months. You can use SRS flashcards (like Anki or Pleco) collections that people have made (I recommend this Mnemonics Simplified Hanzi Deck, or Mnemonics Traditional Hanzi Deck). For common words, I recommend Spoonfed Chinese anki deck (note it has some mistakes but I like that it has audio and sentence examples), but there's a ton of anki decks and common word frequency lists (you can genuinely just study a list) just pick a resource you like with either 2000 common words or HSK 4 vocabulary. Literally just pick any study materials where you can learn roughly 1000 common hanzi and 1000 common words or more. Whatever materials work for you. Study however you want - some people find anki flashcards useful (I just cram studied 1000 words for a few weeks each then never looked at anki again), some find books useful, some find textbooks useful, some use vocabulary lists, some use videos, just pick something. Your goal is going to be to study these words/hanzi in 3-6 months. 8-10 months if you want to wait to read longer, or need more time to study. I studied 800 hanzi in the book I linked for the first 3 months, then 1000 words the next month, then 1000 words the next month, then about 500 more hanzi the next month. It is okay to cram study! It is okay to not memorize these hanzi and words! Just get a basic familiarity! You are going to fully learn these common hanzi and words when you READ later.

As you are studying common hanzi and words, start reading a grammar guide if you would like some knowledge of grammar. Or watch some grammar videos on youtube, whatever clicks best with you. Basic Patterns of Chinese Grammar is a good grammar guide summary book, AllSetLearning Chinese Grammar Wiki is an excellent website you can read. I read another grammar guide summary, the website no longer exists. Again, do not try to memorize and drill this stuff, just go through it and get a basic familiarity. You can move on if a particular grammar point makes no sense right now. Learn about grammar the same time you're studying hanzi and common words, so the first 3-6 months.

Okay it's been 3 months! You know some hanzi (maybe 50-500), you know some words (maybe 50-1000 depending on how intensely you've been studying)! Start reading! You're going to start with Graded Readers, which are reading material made for learners. Heavenly Path's Comprehensive Reading Guide suggests some free graded reader resources in the Below 1000 characters section. I used Mandarin Companion Graded Readers and other graded readers I could purchase in Pleco. Mandarin Companion has some graded readers with 50 unique characters. I started with some Pleco graded readers that had 300 unique characters, then moved up to graded readers with 500-800 unique characters. Read graded readers! Reread them! Look up any words you don't know (using Pleco or something else). Listen to the pronunciation of any new words. If reading in Pleco, you can use the Dictation tool to hear the sentences read aloud. When using graded readers in general, use any audiobooks that accompany them. Mostly though just read, read, read, and look up anything you want. Look up grammar points in something like AllSetLearning Chinese Grammar Wiki if you are now starting to see some grammar that confuses you while reading. The reading practice is what is going to teach you the words you've been studying in other materials.

Now it's been 6 months. You've been working your way through graded readers of increasing unique character count (and are now reading graded readers of at least 800 unique characters or more). You've been working your way through studying common hanzi and words, and now have studied at least 1000 words or more. (If you cram like I did, you probably have studied over 2000 words but only the 800-1000 words in your graded reading material have been 'fully learned' and the other words you studied are only vaguely familiar, this is perfectly fine). Go to Heavenly Path and start reading the stuff they recommend for people who know 1000-2000 characters. I think @秃秃大王 by 张天翼 is perfect for people who know around 1000 characters to start with. You can keep reading some graded readers like those that go up to 1500-2000 unique characters if you'd like, but start trying to read novels for native speakers too. Again, I recommend anything in the easiest 'recommendations' from Heavenly Path's recommendation list of webnovels, a lot of novels for children will be perfect at this point. You'll gradually work on increasing the unique characters of your reading materials. Read in Pleco or Readibu so you can use the click-translate tool. To find webnovels online, paste or type the chinese name of the novel (and author if you know it), and then 'zaixian yuedu' like this '秃秃大王 张天翼 在线阅读'. It is very easy to find novels online in chinese.

From here you just continue reading more difficult novels! Go at the pace you choose! Once you're reading stuff with 2000 unique characters, then if you wish you can stop studying hanzi and common words outside of just looking them up in reading. You can of course continue to study hanzi and words outside of reading. But if you'd rather just learn words by looking them up as you read, you can start doing that as soon as you switch to novels for native speakers (1000-2000 characters). Congrats, you are reading webnovels!

Some people start reading webnovels within a few months, and you can start with a higher unique character count if you wish. Such as starting with MoDaoZuShi or Zhenhun or SaYe as soon as you go from graded readers to regular novels. The difficulty curve will be a lot steeper, and you'll be looking up a LOT of words for a while. But other people have done it. I started reading webnovels around 6 months, after doing graded readers for a while, and it took picking several easier and harder reading materials until I found a comfortable reading level to continue from.

So it boils down to: start studying very common words and hanzi (a list, a book, anki, whatever works for you, and you don't have to memorize just get some Exposure some Basic Familiarity), read about grammar if you wish (again just get some Basic Familiarity so later if you need to look up a grammar point in depth as you read, you know what to look up), and START READING ASAP. Use Pleco and Readibu to read with click-translations of words. Start with graded reader materials, then as soon as you can tolerate move on to novels for native speakers. Heavenly Path's website is a great resource for finding reading material at your level if you have no idea what to pick and don't want to trial and error different webnovels until something is doable. For anyone who finds sounds help with memory (like me) or who plan to eventually learn to listen to chinese, listen to the pronunciation of any new words when you look them up. If you watch cdramas, cdramas often have chinese subtitles on them, those can be good practice for reading as well.

You can start reading within a year. You can read graded readers within a few months, as soon as you feel it's tolerable. And then you can just learn new words BY reading, review words you've looked up before BY reading, review grammar BY reading, and work your way up to reading whatever webnovels you want. I find learning words BY reading much easier for myself, doing what I want to do in the language as I'm learning to read, much easier to stick to and enjoy than anki flashcards or word lists or textbooks. So from me, the suggestion to push yourself to read graded readers ASAP is so you can get to the part of learning BY reading quicker.

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning Hanzi

I know I'm a broken record about this. The big picture is you should learn hanzi however you want, in whatever methods work for you. The small scale however is there's a lot of people who give their advice and a lot of people push their products cost a lot and only teach you '200 hanzi' and claim they'll get you fluent... that is just not enough to read. I've bought multiple textbooks that taught only 100-200 hanzi, it really frustrates me how many of these things capture learner's attentions and hopes only to leave them still beginners after learner's spend months or years on them.

Hesig's Remember the Hanzi/Remember the Kanji books are super well known, and often recommended. I think these books have a use but mostly just... in how they explain what mnemonics are, and radicals in characters. Go to some bookstore for free, or library for free, or find a pdf of the book free online, and just read the beginning explanation of radicals and what mnemonics are.

Or look up radicals and mnemonics online free - there's explanations out there which are more understandable for some people than Heisig's book, and which also go into hanzi types (here's one, here's two more here and here that go into phonetic components that I have found useful, one on phonetic sets). This site has written mnemonics for a bunch of hanzi, as does this site.

My personal favorite way to make mnemonics for hanzi is this: take any characters that build the new character - so for hao 好 it's woman and child, 柊 it's tree and winter. Then make up a story that involves the 2 things and the meaning of the hanzi. If I want to make the mnemonic include the pronunciation, then I might add a word that sounds like the pronunciation into the mnemonic. Example: in winter time 冬 the tree that has berries 木 is holly, the berries sound like zhong as they fall to the ground.

My favorite book for learning hanzi is this HSK 1-3 800 Characters book, because it wrote pre-made mnemonic stories for 800 common hanzi, including a system to include the sound and tone of each hanzi in the mnemonic story. The stories also tend to be ridiculous, which helps with remembering them until you don't need to rely on them anymore. Note: the book is available in many ebook libraries for free (so check Hoopla, your local college's e-library). I think it's great for people like me who suck at making up mnemonic stories, at least as a beginner. If you're already great at making your own mnemonics, skip it. If you already can make your own mnemonics, skip Heisig's book too as the book doesn't include many mnemonic stories and mostly expects you to make up your own - only use Hesig's book if you just want a list of the hanzi in book form I guess. Although there's free hanzi lists online, and probably better books that go through hanzi to explain them in depth. After that HSK 1-3 800 Hanzi book, I used this mnemonics hanzi anki deck until I was able to start remembering hanzi on my own. The anki deck is also available in traditional, and a traditional+simplified option.

Honestly if you only do 1 think, the most useful bang for your buck (because it's free and has 3000 hanzi) is to just go through the mnemonics hanzi deck. I would recommend reading some free articles online about radicals, how to make mnemonic stories, and phonetic components in hanzi first. Just because if you're aware of those things, you can start making up your own 'way to remember' new hanzi you happen to see while reading or watching shows, even if you aren't using any books or anki decks.

Eventually at a certain point, maybe once I learned 1500-2000 hanzi, I started remembering the rest just by going 'X part' is sound component and I remember the sound based on that, 'Y part is related to meaning' so something like 疾 the top part is like other words such as 疾病 related to sickness (so this word has to do with illness) and 矢 is shi which for me is close enough to ji (same final i) to remember this hanzi is ji. Then how much I specifically remember the hanzi's meaning will depend on what words I've been seeing it in, and context. This is also how I guess what pinyin to type into a translator if I'm trying to figure out the word - for this 疾 I'd probably have typed zhi/ji/shi until the right hanzi pops up, or if I knew the full word jibing I might type zhibing jibing until the search recognized what it was.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

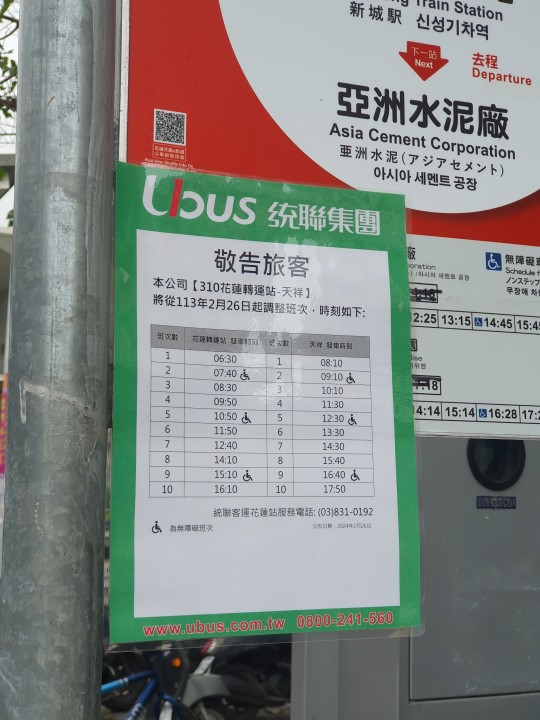

Direction: Taroko National Park/ Part One

When I decided to visit Taroko National Park using only public transportation, I didn’t have high expectations, but I decided to give it a shot. I arrived at Hualien station in the morning and headed to the bus stop: no issues, except that the buses ran infrequently, and the schedules could be a bit unpredictable. Encouraged by the welcoming demeanor of the gentlemen and lady waiting at the bus stop, I decided to ask them for some information: that’s when, out of nowhere, my luck began!

My luck was called 云霞 (Yunxia), a Chinese lady's name, meaning "rosy clouds." After gathering some courage with my somewhat broken Mandarin and getting some helpful information from a few kind gentlemen, or 叔叔 (uncles), about whether my plan was feasible, a short, middle-aged woman with a warm and open attitude, reminding me a lot of one of my inspiring high school teachers, told me that she was heading in the same direction. That's how we ended up heading in the same direction toward 砂卡礑步道 (Shakadang Trail: a name likely derived from the Atayal indigenous tribe, referring to a place characterized by sand and rocks).

From the station, we got off after 11 stops, and despite the slightly cloudy weather, once we passed the entrance and descended the steps, we were greeted by a lush, green landscape. I had thought Yunxia would just accompany me to the stop, but instead, after exchanging a few words to get to know each other, taking photos of the scenery and of each other, despite my shaky Mandarin, we somehow understood each other very well, and continued to walk together.

We ended up walking the entire trail together, reaching one of the most scenic spots of the Canyon: crystal-clear water, smooth rocks, lush greenery, and dark clouds contrasting with a kind of grey mist that occasionally descended to the height of the trees.

Yunxia decided to buy some local food from a few stalls run by locals, and her kindness, openness, and generosity towards everyone she met deeply inspired me. It felt like walking among friends, as she addressed every person we encountered as if she had known them forever, and they responded in the same way. I felt warmly welcomed by everyone we met, and she introduced me as her newly-met friend; despite the few words, the smiles, and gestures spoke volumes.

After avoiding a bit of rain and finishing the meal — which she insisted on offering me (black rice with a sweet filling, served inside bamboo) — we decided to head back. After all, we wanted to continue on to at least two more stops, and with the unpredictability of the buses, who knew if we’d make it! On the way back to the bus, we continued getting to know each other. She asked me, 'Try to guess what my profession was before retirement, 猜猜.' And guess what? As I had thought, of course she was a teacher!

This is just the first part of a short story from a late February 2024 day when I went to Hualien from Taipei, with the main goal of exploring Taroko Canyon National Park, without much planning. If you enjoyed this, stay tuned for the second part in the coming days, along with more adventures around Taiwan and mainland China.

Recalling these memories, it’s impossible not to think about the losses caused by the earthquake that occurred on April 4, one month after my trip. Due to the severe damage, this section of the trail is now closed. (Note: the earthquake had a significant impact on the region, and the trail has been closed ever since.)

20 notes

·

View notes

Photo

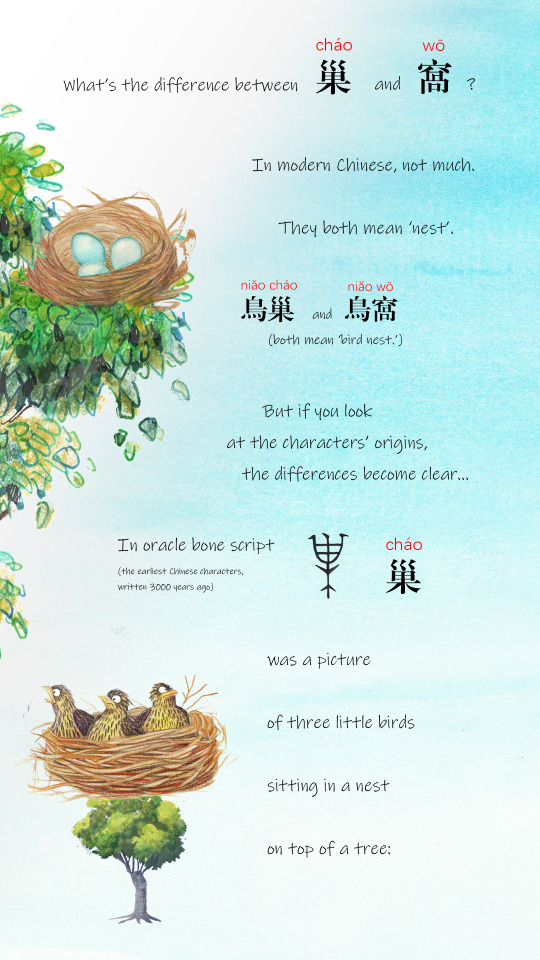

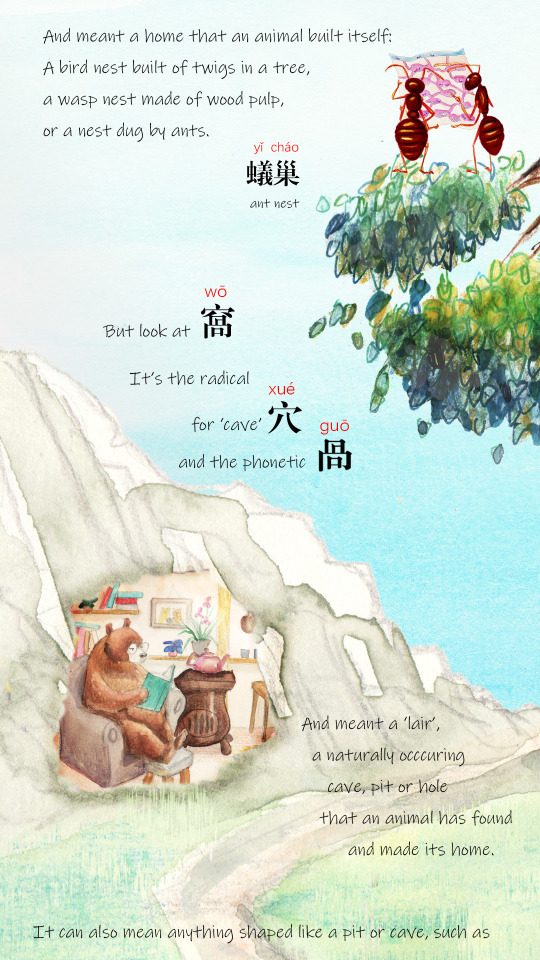

What’s the difference between 巢 cháo and 窩(窝) wō?

In modern Chinese, not much.

They both mean ‘nest.’

(鳥巢 niǎo cháo and 鳥窩(鸟窝) niǎo wō both mean ‘bird nest’).

But if you look at the characters’ origins, the differences become clear.

In oracle bone script (the earliest Chinese characters, written 3000 years ago), 巢 was a picture of three little birds sitting in a nest on top of a tree. It meant a home that an animal builds itself: A bird nest built of twigs; a wasp nest made of wood pulp; or a nest dug by ants.

蟻(蚁)巢 yǐ cháo ant nest

But look at 窩(窝) wō,it’s the radical for ‘cave’ (穴 xué) and the phonetic guō (咼(呙)), and meant a 'lair’: A naturally occurring cave, pit or hole that an animal has found and made its home.

It can also mean something shaped like a pit or cave, such as

胳肢窩(窝) gā zhi wō armpit, or

酒窩(窝) jiǔ wō dimple (in the cheek, etc), literally 'alcohol lair.’

Please note that the phonetic in 窩(窝) wō, 咼(呙) guō, you’ll most likely encounter as a last name, but it’s also pronounced 'wāi’ and means 'lopsided’, originally describing a lopsided mouth (hence the 口字旁 mouth radical). But a much more common wāi character for lopsided is 歪,which is an extremely satisfying character, made up of '不正.’

@liu-anhuaming

414 notes

·

View notes

Text

Responding to common douyin hooks

English added by me :)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

The known-ish words of intermediate Chinese, or: What does it mean to know a word?

We all have this intuition, especially in languages like Chinese, that there are words we 'kind of know'. These are the known-ish words. In the case of Chinese, most people would recognise at least three axes:

1) Do I know the meaning? 2) Do I know the pronunciation? 3) Do I know how to handwrite it?

You might answer yes to some, but no to others. Voila! You know the word - ish.

And then you can also add the dimension of passive and active knowledge:

1) Do I recognise this word passively? 2) Can I use this word actively?

Great. Even more ways of kind of but not really knowing a word. But that's far from all. There's also the different domains of listening and reading, writing and speaking.

So passively, that looks like:

1) Do I know the meaning when listening? 2) Do I know the meaning when reading? 3) Do I know the pronunciation when reading?

Once we add in the active dimension, it all starts to get a bit more complicated. This is far from an exhaustive list, but consider the follows ways you could define 'knowing' a word:

1) I can read the word out loud (but I don't know what it means, and I can't use it in a sentence) 2) I know what the word means, and I can use it in a sentence (but I can't handwrite it) 3) I can use the word in a spoken sentence (but I don't know how to type it, or which character it uses) 4) I can recognise the word when reading (but don't know how to read it out loud, and can only guess at the meaning) 5) I can use the word in a written sentence (but not a spoken sentence) 6) I can type the word and recognise the word (but I don't know how to handwrite it) 7) …

Okay. What else?

Chinese is a compounding language.

Have you ever had the experience that you can't recognise a character individually, but as soon as you see it in a familiar compound, you know what it means? So:

1) I can recognise the word individually 2) I can recognise the word as part of a compound 3) I can recognise the word as part of an unfamiliar compound

Chinese is also a language with a long and storied tradition of writing in Classical Chinese as a literary language and a lingua franca across the whole of East Asia - even two hundred years ago, people were writing in Literary Chinese. 'Mandarin' as a concept did not exist.

So often the meanings of familiar characters can be quite different in formal language or chengyu in the modern language, which uses more classical / literary structures and grammar.

Take, for example, the character 次. The first layer of meaning in modern Chinese - the most foundational layer - is its meaning as time, like 'I have been to Ghana two times'.

But its second layer of meaning is secondary, or next best, or just next. For example:

1) 次货 - substandard goods 2) 次子 - second son 3) 次年 - next year

And so on. Many common words have this kind of polysemy.

So we can add another dimension:

1) I recognise this word's common meanings 2) I can use this word's common meanings 3) I recognise this word's less common meanings 4) I can use this word's less common meanings

Add in the reading and listening dimensions, and things get even messier. I am familiar enough with this basic secondary meaning of 次 to fairly quickly be able to understand that it means 'next' or 'second' rather than 'time' if I see it in a written unfamiliar compound or chengyu. But I am most definitely not quick enough to do that every single time whilst listening to the news, for example!

And what about pronunciation? Once you know a fair amount of Chinese characters, you can often guess the pronunciation of new or unfamiliar characters. How?

Because of phonetic components.

For example:

请

清

情

Notice how these all have the same component on the right? This tells us that these characters belong to the largest group of Chinese characters, phonetic-semantic characters. That is - some part of the character gives a clue to the meaning, and some part gives a clue to the pronunciation. In this case, we know they are all pronounced some variety of qing.

But it isn't always that easy. Some phonetic components tell you the tone and pronunciation - some tell you the pronunciation, but not the tone (like qing above). Some phonetic components, to go even further, are only really decipherable if you have a particular interest in phonology or historical linguistics, or learn the patterns. Consider:

脸 - lian3 (face)

险 - xian3 (dangerous)

验 - yan4 (test)

剑 - jian4 (sword)

签 - qian1 (to sign)

捡 - jian3 (to pick up)

There are far more. If you look down the whole list on Pleco, they all show a similar pattern of variation. You can see some patterns, but also numerous exceptions - most end in the -ian final, except for those that are yan of various tones. All begin with l, x, y, j, q. Most are pronounced jian3, but that is far from a rule.

All this to say - you can see a character, and know vaguely how it is pronounced. If I know that a character is pronounced qing definitely, 100%, but don't know the tone - does that mean I know the pronunciation? Or would you only say that knowing it 100% means knowing it? And in that case - how can you account for the fact that learning a character when you already know 90% of the pronunciation is significantly easier than not knowing it at all?

Let me add just a few more scenarios. Bear with me!

1) A character has more than one way to be pronounced. For this word, you read it incorrectly (but you usually know it). 2) A character has more than one tone. Some people pronounce it always with one tone, and some alternate between the two pronunciations. You only knew it with one - but you're half right? 3) You make the same mistake that a native speaker would make with tone or pronunciation of a rarer character.

In some way, these are all more knowing than not knowing anything at all.

And none of this is even taking into account different writing systems, traditional and simplified.

Here are some more scenarios:

I recognise the character in traditional (but not simplified)

I can type the character in both, but I can only hand-write in simplified

I know the Taiwanese pronunciation, but not the Chinese

etc

And of course Chinese characters are used across multiple different languages.

So you could conceivably have these kinds of situations:

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese and Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese, and the meaning in Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Mandarin and recognise it in Cantonese, but know it means something different

I know the pronunciation in Mandarin, but don't know what the whole word actually means in Mongolian (Chinese characters used to transliterate Mongolian words)

Plus there's handwriting and calligraphy!

Personally, I can't read a lot of calligraphy and have accepted my happy illiteracy in many styles. All Chinese learners and heritage speakers know the feeling of sitting in a Chinese restaurant or museum and having a well-meaning friend say, 'Oooo, what does that say?' It's depressing! So let's add some more nuances to our known-ish characters:

I can read this character in common fonts

I can read this character in less common fonts

I can read this character when handwritten

I can read this character when handwritten quickly / by a child / by a doctor

I can read this character in grass script / seal script / etc

Then there's the question of naturalness.

I frequently add words to my Anki decks that I would be able to understand, no question, if I were reading or listening - but I probably wouldn't have thought to say it in that way. So:

I recognise this word, and would have said it exactly like this

I recognise this word, but would never have thought to say it like this

I can use this word, but didn't know you could use it in such a metaphorical way

I can use this word in a metaphorical way, but didn't realise it corresponded so closely to English / was so different from English in its meaning

And finally there's the simple question of memory.

I know I've seen this word before, but I can't remember it right now and I want to drown myself pathetically in the vast uncaring sea

I know I used to be able to use this word actively, but now can only use it passively

I can still type it, but have forgotten how to handwrite it

I can still use it in writing, but I wouldn't be able to use it in speaking

I can recognise it in set expressions, but wouldn't remember how to use it on its own

I can remember the simplified character, but not the traditional

…

So how many ways do you know a word?

I often feel embarrassed to post my vocabulary lists, because I feel that people will be surprised that I don't 'know' certain more foundational words. I think they will be confused as to why I have very 'advanced' vocabulary alongside 'simple' vocabulary. I feel a lot of pressure to be 'advanced' because of the amount of followers I have, but there's a lot of more basic characters I still don't fully know in a holistic way.

And the truth is that all of those characters and words are in Anki for different reasons. I might have a vocab list that looks like this:

略

松懈

星光

缕缕

薄雾

博览

I don't know any of these words in exactly the same dimensions as I know the others! Let's look at my reasons for including each in detail.

略 - lve4 - slightly. I have this word here because although I know it well in set expressions like 略有耳闻 'have heard a little about',略有受损 'has suffered slight losses' etc, I wouldn't remember the pronunciation if I saw it alone or with another verb apart from 有. I would still know the meaning - but I wouldn't remember how to pronounce it. So even though I 'know' this word, it's still there in Anki.

松懈 - song1xie4 - to relax, lax, slacken. This is a rare example of a totally 'new' word - most of my Anki words aren't. I know 松 already well, but have never seen the character 懈 before: I didn't know its meaning, or pronunciation.

星光 - xing1guang1 - starlight. I know both characters, pronunciation and meaning, and I can easily understand this word. I just never would have thought to say it so simply. I want to use it actively, so I put it in Anki.

缕缕 - lv3lv3 - fine and continuous (i.e. rain, drizzle). I know 缕 already on its own as a measure word for sunlight, thin hair, gossamer, mist, smoke, fine threads etc - I often forget its pronunciation, but I know its meaning reliably when reading. But together the compound 缕缕's meaning isn't quite extricable from just knowing 缕, so I put it in here.

薄雾 - bo2wu4 - mist, fog. I know 雾 well, but hadn't come across 薄 before (or wasn't sure if I had or not). This is an example where I knew its pronunciation, because of phonetic components, but I didn't know the meaning of the character.

博览 - bo2lan3 - to read widely. I know this word very well. So why is this in there? Literally just because I remembered the pronunciation and meaning of 博览, and when I was racking my brains trying to see if I knew the 薄 in 薄雾, I thought it might be the same character. I looked it up, and it wasn't. So even though I know the word, the meaning and the pronunciation, I had to put it in - because I didn't remember which character was used for the bo2.

When you acknowledge all of the different ways of knowing a Chinese character, it makes sense that your learning after the beginning level is going to be full predominantly of known-ish words.

Accept this! Form your own relationship to it! For me, a huge part in my motivation to return to learning Chinese after a year-long break was just to accept that I was likely never going to 'fully know' most of the characters and words that I partially know.

But that's okay. Think about your native language.

If your native language is English or you speak it very well, consider a word like monadic. Could you say you knew this word? Fully knew it? Like me (I learnt this word in the context of Linguistics yesterday), you might have an idea that it has something to do with one - mono, monorail, monotropism, monologue, monolithic etc. But would you be able to use it in a sentence? Would you be able to explain it to a child?

Or let's say you're learning two new English words: lithology and dreich. (The latter is a Scots word, not English - you would hear it in Scotland frequently.) Neither word you completely know. Which one is going to take you longer to learn?

It's likely going to be lithology. You can form connections with words like monolith or paleothic or maybe even lithium - even if you couldn't say for sure what the Greek element lith means, you're passingly familiar with other words containing it. You also know -ology, and you know how to pronounce the word. If you learn that it means 'the study of rocks', that is probably quite easy to remember.

Dreich, on the other hand - what is there to tell you a) how to pronounce this, or b) that it means 'dreary' or 'bleak', as in, dreary weather? You can't form any connections with similar words at all, and the [x] sound at the end - like in German or Hebrew - might be unexpected to hear if you don't live in Scotland.

That's what Chinese is like in the beginning. All words are like dreich. But the more you learn, the more words begin to be like monadic or lithology.

Learning ten new words a day like dreich would be very difficult. But if you've seen monadic a few times over the last few months, know vaguely when to use it, know how to pronounce it - it's not so hard to imagine that you could learn ten of those a day.

I find all these known-ish words very overwhelming.

And I also find recognising the potential for overwhelm in the Chinese language - because of its unique properties - very helpful in letting me feel less guilty about my current known-ish words. I do know them - ish.

But when I finally get around to properly learning them, all that ish-ness will make them that much easier to remember!

Now I try not to stress out about these types of words. I recognise that, in many ways, they are inevitable. Unless you're a poet who composes out of thin air, you're not going to ever say a literary word for emerald green as frequently as you'll read it in descriptive passages in novels.

It's natural to know certain words in a spiky profile: to know them very well in some ways, but not at all in other ways.

The more you read, the more pronounced this can become.

So here's what I've learnt, and here's the message of all this big, long, rambling post:

Putting 'easy' words that you feel you should know into Anki isn't regressing. It's adding another dimension of knowledge to your understanding of the word. You shouldn't feel ashamed or frustrated when you find you don't know one aspect of an otherwise 'easy' word. I'm still trying to learn this.

Because -

Having lots of known-ish words is not a unique failing on your part. It's a reflection of Chinese as a language and its unique complexity -

And it's part of what makes it so uniquely beautiful.

Have a nice day, everyone. meichenxi out!

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

chinese comrades have our back ❤️🇨🇳

7K notes

·

View notes