Text

A BOX.

A large box is handily made of what is necessary to replace any substance. Suppose an example is necessary, the plainer it is made the more reason there is for some outward recognition that there is a result.

A box is made sometimes and them to see to see to it neatly and to have the holes stopped up makes it necessary to use paper. A custom which is necessary when a box is used and taken is that a large part of the time there are three which have different connections. The one is on the table. The two are on the table. The three are on the table. The one, one is the same length as is shown by the cover being longer. The other is different there is more cover that shows it. The other is different and that makes the corners have the same shade the eight are in singular arrangement to make four necessary.

Lax, to have corners, to be lighter than some weight, to indicate a wedding journey, to last brown and not curious, to be wealthy, cigarettes are established by length and by doubling. Left open, to be left pounded, to be left closed, to be circulating in summer and winter, and sick color that is grey that is not dusty and red shows, to be sure cigarettes do measure an empty length sooner than a choice in color.

Winged, to be winged means that white is yellow and pieces pieces that are brown are dust color if dust is washed off, then it is choice that is to say it is fitting cigarettes sooner than paper.

An increase why is an increase idle, why is silver cloister, why is the spark brighter, if it is brighter is there any result, hardly more than ever.

Excerpt From Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein.

0 notes

Text

A RED STAMP.

If lilies are lily white if they exhaust noise and distance and even dust, if they dusty will dirt a surface that has no extreme grace, if they do this and it is not necessary it is not at all necessary if they do this they need a catalogue.

Excerpt from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein.

0 notes

Text

A METHOD OF A CLOAK.

A single climb to a line, a straight exchange to a cane, a desperate adventure and courage and a clock, all this which is a system, which has feeling, which has resignation and success, all makes an attractive black silver.

Excerpt from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein

0 notes

Text

Roman cavalry mask, Hellvi, Gotland, migration era ~400 CE

667 notes

·

View notes

Text

Iran’s Daughters of the Sea

Kobra Arbabi, a native of Hengam Island, has been fishing for more than twenty years.Photographs by Forough Alaei

Forough Alaei’s stunning photographs of a community of fisherwomen on a remote island in the Persian Gulf.

By Robin Wright June 7, 2025

Hengam Island is a tropical isle off the coast of Iran, at the southern end of the Persian Gulf. Just fourteen square miles, it has three villages with only a few hundred families. The island has long been recognized for its geostrategic importance. Nearchus, the Greek explorer and admiral of Alexander the Great’s naval fleet, referenced it when he navigated the Gulf in the fourth century B.C. Hengam was occupied by the Portuguese military in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. In 1913, Britain established a naval base there. Since the late nineteen-forties, tanker ships have skirted Hengam en route to the Strait of Hormuz, a global choke point about thirty-seven miles away. A fifth of the world’s supply of oil and natural gas passes through it each day.

Khadijeh Ghodsinejad is the youngest female fisher in the community. She began accompanying her mother on fishing trips in a rowboat when she was four or five.

Today, Hengam may be most noted for its so-called daughters of the sea, the only fisherwomen in Iran—and probably in the eight other countries around the Gulf. Forough Alaei, a law student turned photojournalist, spent years documenting the women as they set off at dawn, without men and often alone, to ply the Gulf waters. In small, weathered boats, they fish for barracuda and spangled emperor, which have vibrant blue markings that change color when they are frightened or caught. Both fish are famed for their sharp teeth and ferocious bites.

Preparing fishing hooks for the day.

A day’s catch.

The women’s clothing is as vibrant as their catch. They wear full-length burqas, a style more common in Afghanistan and the Arab sheikhdoms than in Iran. Burqas are often a dark, solid color. Theirs, though, are sewn from summery blue, orange, and pink floral prints. The history of their attire goes beyond Islamic modesty, Alaei told me. According to one narrative, women masked their faces when the Portuguese, and later the British, occupied the island, to try to prevent harassment—or worse. Some burqas, as stated by local lore, included ersatz mustaches, to further discourage threats from foreign men. Burqas also provide women protection from long days under a punishing sun.

Ghodsinejad goes fishing several days a week. She uses a portion of her catch at her restaurant, and sells the remainder through her Instagram page to customers across Iran.

After long hours on the water, a fisher grew weary and tied the fishing line to her toe, so that she could recline.

Hava Arbabi, a native of Hengam Island, has been fishing for thirty years. Nowadays, she spends most of her time at her booth, as knee pain prevents her from working on the water.

They have worked in defiance of Iran’s labor laws, which stipulate that “women shall not be employed to perform dangerous, arduous or harmful work.” For decades, the government failed to grant fishing licenses to women, depriving them of fuel subsidies and the right to insure their boats. After the women protested, the Fisheries Department agreed two years ago to issue licenses, though each had to be shared by two women, even if they had their own vessels.

Iran’s theocracy is strident about its priorities. “The most important role that a woman can play at any level of science, literacy, information, research, and spirituality is the role of a mother and wife,” Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has decreed. “This is more important than all her other works.” Within a family, a father or husband is also able to prevent his daughter or wife from working a job that he deems beneath the family’s dignity. Last year, the World Economic Forum’s report on the global gender gap ranked the Islamic Republic among the bottom four in its survey of a hundred and forty-six countries.

Sakineh Karimdadi has been fishing since her twenties.

Ghodsinejad cleaning fish in front of her seaside booth.

Alaei, whose larger body of work captures girls and women challenging taboos in Iran, was inspired by the fisherwomen. “It was amazing to see women who have a critical role in the economy of the family,” Alaei told me. “The rate of women in the labor force in Iran is less than twenty per cent. But on a really traditional island women were a great part of the economy.”

Modernity is seeping into remote Hengam. Some fisherwomen have objected to being photographed—and put on social media—by tourists, who are vacationing on the island in increasing numbers. But at least one fisherwoman is using social media to her advantage. Khadijeh Ghodsinejad, the island’s youngest fisherwoman, and the mother of a toddler, offers her catch nationwide on the Instagram account Khajoou. (Fish sold the typical way, through an intermediary, go for between fifty and eighty U.S. cents a pound—half of what can be made selling directly to consumers.) She’s amassed more than a hundred thousand followers. With her husband, Kayhan, she also operates a small hostel and café where they cook her fresh catch.

A group of women pose for a selfie before work.

Marziyeh Arbabi is a chef at a local restaurant.

As outsiders visit more frequently and Hengam becomes more connected to the rest of Iran, the daughters of the sea have declined in number. Today, around a dozen are still fishing. The younger generation want more education, secure office jobs, the attractions of urban life, and the promise of pensions, not demanding physical work dependent on fickle weather and the unpredictable sea. Alaei’s photographs also capture Hengam’s youth wearing matte red lipstick reminiscent of Taylor Swift, taking selfies on cellphones, smoking hookahs, and wearing masks in red and bright yellow, some bedazzled. She worries that Hengam’s current fisherwomen may be its last.

Kobra Arbabi at the end of a long day.

1 note

·

View note

Text

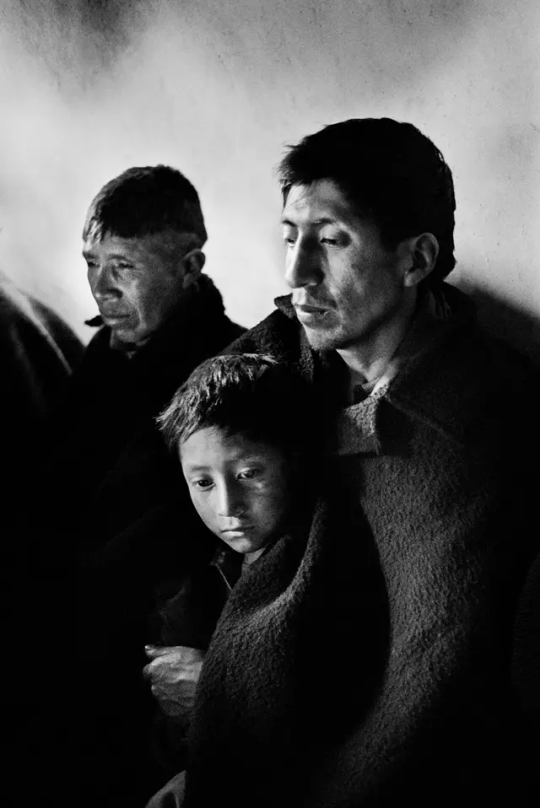

Sebastião Salgado’s View of Humanity

Chemical sprays protect this firefighter against the extreme flame temperature. Greater Burhan Oil Field, Kuwait, 1991.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

The photojournalist documented some of the greatest human horrors of the past century, but he said, “I never, I never, photograph the misery.”

By Chris Wiley May 31, 2025

Sebastião Salgado, who died last week, of leukemia, at the age of eighty-one, was among the most famous documentary photographers of the twentieth century. Throughout more than four decades of epic, globe-spanning projects, many of which were both self-assigned and largely self-funded, he forged an instantly recognizable aesthetic in a field that tends to shy away from overt authorial touch. His pictures were sweepingly cinematic, symbolically loaded, and unabashedly gorgeous, even when he was photographing some of the greatest human horrors of the past century, such as the famine in the Sahel region of Africa in the mid-nineteen-eighties, or the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. A latter-day cornerstone of what Cornell Capa once dubbed “concerned photography,” Salgado’s work earned him numerous prestigious prizes and was showcased in grand touring exhibitions and in hefty coffee-table books. Sandra Phillips, the former senior curator of photography at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, once called him “one of the most important artists in the Western Hemisphere.”

Rwanda Refugee Camp, 1994.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Salgado’s pictures were also freighted with their fair share of controversy. Susan Sontag, in her final book, “Regarding the Pain of Others,” called him“a photographer who specializes in world misery,” whose work “has been the principal target of the new campaign against the inauthenticity of the beautiful.” The critic and editor Ingrid Sischy wrote in a scathing 1991 piece for The New Yorker that Salgado’s work was “oversimplified,” “heavy-handed,” and ultimately ineffectual. “To aestheticize tragedy,” she said, “is the fastest way to anesthetize the feelings of those who are witnessing it. Beauty is a call to admiration, not to action.” How you feel about Salgado’s work might depend on whether you agree with that statement. If you believe that difficult truths should be delivered only in their rawest, plainest form (which is, of course, simply another form of artifice), then Salgado’s stunning images are not for you. But, if you believe, as I do, that most viewers are savvy enough to separate content from form, then Salgado’s operatic style can be seen as a potent enhancement of his act of bearing witness.

Refugees in the Korem Camp, Ethiopia, 1984.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Salgado was born in the Brazilian municipality of Aimorés, in the state of Minas Gerais, in 1944. He grew up on a cattle ranch alongside seven sisters, and as a young man he became an avowed Marxist. After a military coup in 1964, he and his wife, Lélia, fled to Paris, where he completed coursework for a Ph.D. in economics from the Sorbonne, before taking a job in London at the International Coffee Organization. He stumbled into photography after borrowing a camera Lélia had purchased to aid in her studies to become an architect, and became so quickly enamored that, soon enough, he built a darkroom in their apartment. After some debate, he turned down a job offer with the World Bank and resolved to become a photographer.

First Communion in Juazeiro do Norte, Brazil, 1981.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Within a few years of working as a peripatetic photojournalist, during which he covered a handful of minor conflicts and standard-issue fare such as golf tournaments, Salgado secured a spot with the legendary photo agency Magnum, in 1979. (He later broke with Magnum to found his own agency with Lélia, Amazonas Images, which exclusively represented his work.) In 1981, on assignment covering the early days of the first Reagan Administration, he took a career-making series of pictures of the aftermath of John Hinckley, Jr.,’s assassination attempt, which were picked up by newspapers across the globe—and the financial windfall from these shots allowed him to purchase the Paris apartment that he lived in with his wife until his death. But Salgado undertook his most ambitious projects independently.

Eastern Part of the Brooks Range, Alaska, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Gold mine, Serra Pelada, Brazil, 1986.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

“Workers: An Archaeology of the Industrial Age,” the first of three mammoth series completed over nearly three decades, was an attempt to commemorate manual labor at a time of rapid mechanization. The pictures, which were taken in twenty-six countries, cover an exotic range of human endeavors, including the production of perfume in Réunion, the quelling of the Kuwaiti oil fires, and, most famously, the toils of gold miners in Serra Pelada, Brazil. Overwhelmingly, the pictures portrayed manual work as a noble, even romantic enterprise. In one, we see a Galician fisherman perched at the head of a small, crowded boat, staring into the middle distance with a gravity befitting Odysseus. In another, we see a Bangladeshi ship-breaker dwarfed by the sublimely towering husk of a boat docked on a beach, suggesting an industrial-era update of Caspar David Friedrich’s “The Monk by the Sea.”

Fishing in the Piulaga Laguna during the Kuarup ceremony of the Waura Group. Upper Xingu Basin, Mato Grosso, Brazil, 2005.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

Sischy, in her critique of Salgado, wrote that his approach to industrial labor shared none of the activist bite of Lewis Hine’s turn-of-the-century pictures of child laborers, which famously played a role in cementing anti-child-labor legislation. Salgado’s “basically uncritical” pictures, Sischy asserted, “would look at home in corporate annual reports.” Like Hine in the latter part of his career, which was largely defined by his heroic, semi-staged photographs of workers, Salgado was principally concerned with portraying the fundamental humanity of his subjects, asserting the value of their work rather than portraying them simply as victims of rapacious exploitation. In this way, they were perhaps closer to Soviet-style socialist realism than they were to boosterish corporate pablum.

Gold Mine, Serra Pelada, Brazil, 1986.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

A worker rests after an exhausting day trying to put new heads on the wells. Workers toil in twelve-hour shifts. Kuwait, 1991.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

Last year, on the occasion of Taschen’s reissue of “Workers” (originally published in 1993), I had the chance to interview Salgado over video chat. He was in Paris, sitting in his studio, with a mural-size print of one of his photographs behind him. Salgado had a smooth shaved head and wild white eyebrows. In conversation, he was charming and genial, but he is well practiced in sparring with his critics. “People criticize me that what I do is the beauty of the misery,” Salgado told me. “But I never, I never, photograph the misery. Never. I photograph people that were less rich in material goods. Misery, what is the misery?” His follow-up to “Workers” was a project called “Exodus,” which documented the world’s deracinated people—migrants, exiles, refugees. He spoke to me of the importance of community. “When I photograph the refugees that come out of Malawi, going inside Mozambique—if one of them dies, the others will cry for him. You see they have not a bank account, they have no shoes. But they were proud. They were happy. They have a family that they live inside. And they deserve to have a nice picture. Why not?”

Wake, Village of Alao, Region of Chimborazo, Ecuador, 1998.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Yancey Richardson Gallery

After spending time in Rwandan refugee camps, Salgado told me, he suffered from a series of physical and mental maladies. He saw a doctor back in Paris who told him that, though there was nothing physically wrong, if he kept pursuing his work he would surely die. “I was so upset to be a human being,” he said, “because I saw the amount of violence that we are capable of. We are a terrible species. I gave up photography. I said, ‘Never more in my life I do pictures.’ ” Salgado put his camera away and moved with his wife back to Brazil, to the family cattle ranch, which he had inherited from his father. When they arrived, they found the land nearly denuded of life. Lélia suggested that they might try to rewild it, partly as a form of therapy and partly out of ecological concern. Decades later, what is now called the Instituto Terra is a lush Eden, replete with wildlife and more than two and a half million trees, and serves as a kind of laboratory, providing inspiration for similar projects around the world. “This forest coming back gave me a huge wish to photograph again,” Salgado told me. “And in this moment I said, ‘I go to see my planet.’ I wanted to see what is pristine in this world.”

Zo’e Group, State of Para, Brazil, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

The resulting eight-year project, “Genesis,” was a paean to natural landscapes and Indigenous ways of living, from Antarctica to the Amazon rain forest. The project is tinged with a tentative note of optimism—look how much of our Earth remains unspoiled—but it also represents a sort of pulling away from humanity. “Before then, I had only faith in humanity,” he told me. “I started to discover that the planet was not composed only of human beings.” Salgado, who is survived by Lélia, their two sons, and two grandchildren, was eighty years old at the time of our conversation. Although he was still occasionally making pictures—he had been trying his hand at drone photography—his days of crafting large-scale projects were over. The waning of Salgado’s career seemed to mark the end of an era of ambitious, essayistic photojournalism, which has been under pressure for more than a decade owing to dwindling print-publication budgets and increased reliance on iPhone-toting “citizen journalists.” Salgado reflected on the privilege of seeing the world as thoroughly as he had. “To see what I see, to have contact where I have—I lived really deep inside the human communities, and I lived deep inside the environment. If it was necessary to start again, I would start exactly as I did before. I had a big pleasure in my life.”

Pico da Neblina, Brazil, 2009.Photograph by Sebastião Salgado / Amazonas Images / Contact Press Images / Peter Fetterman Gallery

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

A LONG DRESS.

What is the current that makes machinery, that makes it crackle, what is the current that presents a long line and a necessary waist. What is this current.What is the wind, what is it.Where is the serene length, it is there and a dark place is not a dark place, only a white and red are black, only a yellow and green are blue, a pink is scarlet, a bow is every color. A line distinguishes it. A line just distinguishes it.”

Excerpt from Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons.

0 notes

Text

MILDRED'S UMBRELLA.

A cause and no curve, a cause and loud enough, a cause and extra a loud clash and an extra wagon, a sign of extra, a sac a small sac and an established color and cunning, a slender grey and no ribbon, this means a loss a great loss a restitution.

Excerpt from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein.

0 notes

Text

A SELTZER BOTTLE.

Any neglect of many particles to a cracking, any neglect of this makes around it what is lead in color and certainly discolor in silver. The use of this is manifold. Supposing a certain time selected is assured, suppose it is even necessary, suppose no other extract is permitted and no more handling is needed, suppose the rest of the message is mixed with a very long slender needle and even if it could be any black border, supposing all this altogether made a dress and suppose it was actual, suppose the mean way to state it was occasional, if you suppose this in August and even more melodiously, if you suppose this even in the necessary incident of there certainly being no middle in summer and winter, suppose this and an elegant settlement a very elegant settlement is more than of consequence, it is not final and sufficient and substituted. This which was so kindly a present was constant.

Excerpt from Gertrude Stein's Tender Buttons.

0 notes

Text

NOTHING ELEGANT.

A charm a single charm is doubtful. If the red is rose and there is a gate surrounding it, if inside is let in and there places change then certainly something is upright. It is earnest.

Excerpt From Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein.

0 notes

Text

Signs, Yaesu 八重洲

918 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isaac Levitan (Russian, 1860-1900) - Winter in the Forest (1885)

597 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice Brasser Swimmer - Blond Oil on paper, 2024

442 notes

·

View notes

Text

DIRT AND NOT COPPER.

Dirt and not copper makes a color darker. It makes the shape so heavy and makes no melody harder. It makes mercy and relaxation and even a strength to spread a table fuller. There are more places not empty. They see cover.

Excerpt from Tender Buttons by Gertrude Stein.

0 notes

Text

Wassily Kandinsky, Clear Connection, 1925. Watercolor and Indian ink on paper.

237 notes

·

View notes