#For fuck's sake don't read that tube Gladwell

Text

CW for war, bombing, and descriptions of horror.

Valentine's night is the anniversary of one of the most controversial events of the Second World War, the bombing of Dresden. The Combined Bombing Offensive itself is profoundly controversial, the morality of it debated and questioned for nearly 80 years now.

Dresden is a lightning rod to both the far left and right, though for different reasons. The left use it to accuse the arch imperialist, Winston Churchill of being a war criminal. Neo-Nazis use it to say that Germany was innocent and German civilians were the real victims of genocide. And there are others beyond these people, who remember because they either know the full story, or don't, because they know something awful happened that should be commemorated and we should do everything we can to prevent anything like it happening again.

youtube

This is footage of a raid on Pforzheim that took place shortly after the attack on Dresden. A small town in southwest Germany, very little of pre-war Pforzheim remains, because the RAF destroyed 83% of the town that night, and killed a quarter of it's population in ways identical to what happened in Dresden. The tactics and manner of the raid were the same. But Dresden is widely remembered and Pforzheim is not.

And this is because Josef Goebbels intended for Dresden to be.

The Nazi propaganda apparatus made Dresden world famous, inflating the death toll and it's effects, to portray Germany as the victim of Allied aggression. Holocaust denier, anti-semite and goat-fucking piece of shit, David Irving repeated Nazi lies (and added a few of his own) when he wrote about the raid in the 60s. Kurt Vonnegut, who was in the city that night and survived the raid, used Irving's account as source material when writing Slaughterhouse Five.

The myths have taken root while the truth is as horrific, if not worse.

Dresden and Pforzheim were stops on a long line that began with Zeppelins in 1915 and went through towns and cities including Guernica, Rotterdam, Coventry, Hamburg and Tokyo before ending at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Airpower was a novel concept in The Great War, the technology undeveloped. The Germans bombed the UK, killing 1,414 civilians, and - less well known - the British dropped 660 tons of bombs on Germany. Bombing was largely ineffective, in strategic terms, achieving little, but heralded an era where the aeroplane would dominate.

Between the wars, influential theorists like Giulio Douhet predict the destruction of civilisations, entire wars decided by countries being bombed into dust, their populations giving up en masse under a rain of bombs. These ideas are very seductive to interwar generals and air marshals, starved for funding and relevance, and give rise to a generation of proponents eager, when they get the chance, to win a war with air power alone.

The Germans try and, their air force not designed, equipped or led for the task, fail. The Blitz will kill thousands of British civilians and cause great suffering, but does not bring about the collapse of the UK's economy, nor break the morale and will to resist of it's people.

(This gives rise to a strange and awful exceptionalism. When it is pointed out that bombing had not broken Britain's population, and expecting it to do so to Germany's was a shaky idea, this will be dismissed. The British are made of sterner stuff than the German, you see; and, if it hasn't worked so far, this is merely a case of not enough bombs having been dropped and shows the need for vast numbers more to be dropped.)

It will be the British and Americans that truly attempt to bomb their enemies into submission.

The strategies differ. The Americans prefer to fight in daylight, concentrating attacks against industrial and transportation targets, claiming a precision to their attacks that doesn't exist in practice. They use close formation as defence, their bombers equipped with large numbers of machine guns to fight back against German interceptors. Later, they use escort fighters to engage the Germans and, in huge air battles in late 1943 and early 1944, they break the Luftwaffe's ability to contest the air.

The RAF operates differently. Bomber Command flies by night, and targets population centres. Navigating to target is a problem. They struggle to drop bombs within 5 miles of the target and it is only with the coming of large, four-engined bombers and a new leader in Arthur Harris that the campaign coheres in 1942 and 1943.

Harris is a demagogue, steadfastly refusing to allocate his aircraft to tasks he sees as distractions from the main effort of destroying German cities. He will fight the navy, who want him to bomb German U-Boat bases and who need long-range aircraft to patrol the Atlantic. He will argue against bombing the U-Boat's bases in France. His crews will call him 'Butch'. Not out of affection, but for his seeming indifference to the appalling losses they suffer. It is short for 'Butcher'. But he is a very effective administrator and moulds a new, highly destructive force that will lay waste to Germany.

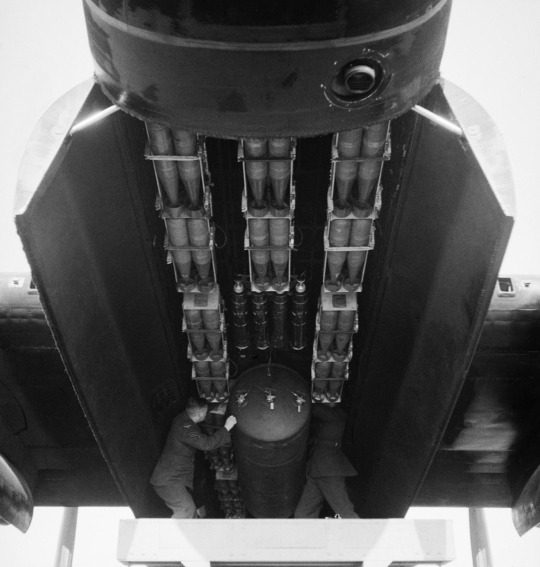

They study the construction of German buildings, calculate the correct mix of high explosive and incendiary bombs and determine how best to make cities burn. Their bombers carry 4,000lb blast bombs nicknamed cookies and small incendiary bombs. The cookies devastate buildings and roads, creating craters, rubble and huge obstacles that hinder rescue and fire-fighting. But that is not their main purpose. The shock wave from their explosions blow out doors and windows in a large area, creating airflow for fires. The RAF drop 68,000 cookies on Germany and 3 million phosphorous incendiaries, because phosphorous cannot be extinguished by water. Bullet-shaped, they punch through roofs, into attics, offices, shops and homes, setting fire to whatever they can, wherever they land.

In the footage of the Pforzheim raid, you can see the flashes of high explosive bombs detonating, the fires caused by incendiaries, and 55 seconds in you can see clusters of target indicators falling slowly into the inferno.

The British employ fireworks companies to develop slow-burning flares of different colours and intensities. They use these target indicators to mark where bombers are to drop bombs. They identify a phenomenon known as creepback - the natural tendancy of bomber crews to drop bombs slightly short so they can get the hell out and go home - and factor it into their planning, setting aiming points beyond the part of a city they want bombed, allowing creepback to sweep the whole city instead. Mass destruction becomes a scientific pursuit.

Master Bombers are introduced, senior airmen who orbit cities at altitudes above the bomber stream and direct the bombing. At Dresden, the Master Bomber will see the primary target overwhelmed with flame and direct bombers onto new parts of the city to burn as much of the city as possible.

The RAF fly diversions, spoofing attacks against cities far away from the real targets. They fly nuisance raids on nights when the main force is resting. They fly precision attacks against specific targets - famously on a night in May 1943 two dams in the Ruhr valley are breached by bouncing bombs. Harris does not like such missions and lends them little support, though he will take credit.

It is euphemistically called area bombing, the attacks against cities a campaign of 'dehousing' when what it is is an attempt to kill German civilians, the workers that keep the economy functioning and their families.

A thousand bombers are sent to Cologne in May 1942, but it is Operation Gomorrah, a week-long campaign against Hamburg a year later that realises the potential of area bombing.

Atmospheric conditions are good, the deployment of a new invention called window - strips of aluminium foil that disrupts radar - renders German defences ineffective, and the introduction of H2S - the world's first ground-mapping radar, and which picks up Hamburg's geography very well - means that bombing is very accurate. Gomorrah is a great success for Bomber Command.

The fourth raid of the week, on 27th July 1943, will see fires combine and burn so intensely a column of superheated air will rush skywards. This sucks in air at ground level, feeding the flames. Winds reach 150mph. Fires burn at 800 degrees celsius and reach 300m into the heavens. 8 square miles of Hamburg is devastated in one of the first documented firestorms of the war. It will become the aim of the RAF to do this on every raid to every city they attack. What happens to Dresden and Pforzheim will not be accidental.

40,000 people die in Hamburg that week. Most are buried in mass graves, their bodies unidentified, testament to the horrific ways they are killed.

Some will die in explosions, their bodies torn to pieces, or are left seemingly untouched, their internal organs pulverised. Others are trapped or crushed under collapsing buildings. They are gassed by the fumes caused by detonations, or suffocated as fires suck the air from their shelters. They burn alive, their bodies reduced to ash. They boil and roast as the firestorm takes hold. Oil and fuel from storage tanks spreads across the harbour and waterways and ignites, preventing escape. The charred corpses of adults shrink to the size of small children. The tar on the streets melts, trapping fleeing civilians who then die, stuck to roads as the city burns around them.

Later in the year, the Allies, thinking forward to the invasion of Normandy and seeing air supremacy as a prerequisite to success, will issue the POINTBLANK directive, aiming their airforces at German aircraft manufacture and industry. The USAAF lose 585 men in a single raid on the ball bearing plants at Schweinfurt and Regensburg in August 1943.

Harris pays lip service to POINTBLANK, continuing to bomb German cities. He embarks on a long campaign against Berlin that winter, deviating occasionally to attack other targets. Berlin, modern, with wide streets, massive ferroconcrete flak towers and sophisticated air defences, resists the assault and doesn't burn. On 31st March 1944, the RAF suffers it's worst day of the war, losing 96 bombers and 691 men on a raid against Nuremberg.

Bombing switches to targets in support of the invasion, both before and after D-Day. Harris will be brought in line and reluctantly sends Bomber Command against targets throughout France. Thousands of French civilians perish under American and British bombs.

Later, as the war in Europe enters it's final phases, the bombers switch back to attacking targets in Germany. They destroy what remains of the German oil industry, and then do the same to it's transport network, crippling it's economy beyond salvage. The intensity and scale of the attacks defy imagination. The Allies drop more bombs on German-occupied Europe in 1945 than they do from 1939 to 1943.

And they attack Dresden.

The Red Army is closing in on Germany's borders and Dresden is a transport hub, shuttling troops and supplies from west to east. It's industries are critical. And it is untouched. It has not been bombed. The rumour is that Winston Churchill has family living there and has ordered the RAF to leave it alone. It's leadership is incompetent and has not prepared for a raid or built large public shelters. It's defences have been stripped, anti-aircraft guns sent to the front or other cities. The RAF only lose 6 bombers, 3 of which are hit by bombs from other aircraft.

The RAF hit neither Dresden's rail yards, nor it's industries, which are concentrated in the suburbs. It targets the old town, densely packed with narrow streets, and it burns. A firestorm rapidly overwhelms it's emergency services and consumes the city. Maybe 25,000 die. Maybe more. USAAF bombers attack the city the following day, hampering rescue efforts. Some of the Americans get lost and bomb Prague instead.

10 days later, the RAF bomb Pforzheim, killing 17,600 people.

In March, the USAAF creates a firestorm in Tokyo. At least 90,000 Japanese die. High-level attacks over Japan are ineffective because the jetstream prevents accurate formation bombing. So the Americans use low-level attacks using napalm incendiary bombs. Bombers return from Tokyo with their aluminium fuselages blackened by smoke. Some bombers, caught in turbulence created by the firestorm, crash.

Japanese cities, their housing traditionally made of wood, are turned to ash and cinder. US bombers drop so many incendiaries on Japan that operations are temporarily suspended because they run out of supplies. Then, in August, they drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Later, one of the justifications offered for the nuclear strikes - and one that dismisses the long-term effects of radiation - will be that they were much less bad than what was already being done to Japan's cities.

55,573 Bomber Command aircrew and around 600,000 German civilians were killed in the campaign to destroy Germany from the air. It was undoubtedly effective. The German economy was dealt massive, decisive blows from which it could not survive and prosper. The lost production, the resources devoted to repairing and restructuring industry, and to defending Germany from the bombers marked a definitive success for the Allies. 30% of German artillery production was devoted to anti-aircraft weaponry. It's aircraft production became so decentralised that the wings, fuselages and cockpits of aircraft would be constructed in different locations and brought to another to be assembled. Complexes were built into tunnels under mountains to protect from attack. Large detachments of workers were organised to repair factories and help industry recover from raids.

But while the bomber's contribution went a long way to winning the war, it remains a war-winning failure. Just like the British before them, German morale did not break. Armies had to conquer the Nazi realm. The navy had to maintain control of the oceans. Air power did not win the war alone.

The bombing campaign can be argued from a position of necessity. Britain had no other way of engaging with Nazi Germany on mainland Europe from May 1940 until mid-1943. This was intolerable to those running the war, both in Britain and abroad. For political, military and economic reasons, Germany had to be bombed.

The morality and ethics of it is a much harder thing grapple with. Wars escalate and radicalise and warp the worldviews of those involved. They are snowglobes of horror and atrocity. Choices that seemed unthinkable at the beginning became obvious and logical the longer the war went on. The lives of enemy civilians mattered far less than the lives of Allied servicemen and women, and amid the escalating evils and devastation perpetrated by Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan the arguments of ruthless men like Harris and the USAAF's Curtis LeMay appeared reasonable. The scale of death and destruction got exponentially larger as technology developed and militaries learnt and became more efficient. Pre-war moralities were abandoned in favour of a victory that had to be total. Bombing shortened the war. It is unknowable if that led to fewer people dying. Or, even if it did, whether that made it the right thing to do in the circumstances.

It is a terrible and grotesque thing to deliberately go out night after night to kill as many civilians as possible in the unproven belief that it will bring about victory. Had the RAF concentrated against industrial and transportation targets, it would likely have had a greater effect on the course of the war and killed far fewer civilians. What was done sits very uneasily with me.

To my mind any moral justification rests on one thing. When, twelve weeks after Dresden, Germany surrendered, the bombing stopped. If the Allies had lost, the killing would have only just started.

Further reading:

#War is fucking awful#However bad you've imagined war to be it is much much worse#ww2#wwII#second world war#Dresden#For fuck's sake don't read that tube Gladwell#Some of those German civilians probably deserved it. There were a lot of Nazis in Nazi Germany after all.

2 notes

·

View notes