#Kuikuru

Text

The Virtual Amazon

No, we’re not talking about a video game featuring an ancient woman warrior. We’re talking about making the museum’s Amazon Basin collections electronically accessible to the people of that region, as well as to scientists and the public. Through collaboration with the indigenous people whose cultures these objects represent, we hope to more widely and authentically share information about the way of life in Amazon Basin villages. The significance of fishing, hunting, gardening, and even rituals ablaze with celebrated feather work can all be better understood through the visual exploration of materials already in the CMNH collection.

With the ongoing massive deforestation in the Amazon by neo-Brazilians for logging, farming, and mining, the “lungs of the world” are under threat, as are the lives of the indigenous people whose way-of-life depends on the flora and fauna of the forest they have managed successfully for centuries. If the forest disappears, or is even diminished much more, its loss will have a devastating effect on the world’s climate. A number of scientists and non-government organizations (NGOs) from Brazil and other countries are partnering with the indigenous people to preserve their lands, their cultures, and their lives.

The border between the Território do Xingu and a neo-Brazilian soybean farm is very distinct.

Although the CMNH project will take some time—and a lot of planning and resources, the growth of collaborative efforts to address the looming threats to the Amazon Basin have made conditions optimal to bring collections-centered stories to the American public. The idea to provide wider access to the artifacts got started two years ago, when on September 2, 2018, Museu Nacional, the national museum of Brazil, was almost entirely destroyed by a fire. The blaze destroyed a magnificent natural history collection, and also one of the largest archeological and ethnographic collections in the world. The institution’s holdings of Amazon Basin material were unparalleled, and are now gone.

By great good fortune and the foresight of then-curator James B. Richardson, the CMNH Section of Anthropology developed an outstanding Amazon Basin collection, starting in the early 1980s. Richardson was also a professor of anthropology, and divided his time between the University of Pittsburgh and the museum. As an archeologist working in Peru, he regularly advised South American-focused graduate students. Whenever one of these students prepared for fieldwork, Richardson would make museum funds available for artifact collection and shipping. Through this process, and aided by purchase of existing collections, the museum amassed materials from 72 Amazon Basin tribes. The three most-complete assemblages (with associated collectors) are from the Yanomamo [Dr. Giovanni B. Saffirio], the Kayapo [Dr Darrel A. Posey], and the Kuikuro [Dr Michael J. Heckenberger]. With the loss of Museu Nacional, these collections are now the best and most complete in the world.

The COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult to predict project timing, but we plan to eventually document every relevant item with high-resolution digital images, and a smaller number with 3-D images, beginning with the Kuikuro collection. Ideally, we would like to bring several Kuikuro people to Pittsburgh to co-curate the artifacts by identifying component materials, and explaining each item’s creation process and use.

Aerial view of Ipatse village, the main Kuikuro settlement. The basic layout of Xingu villages has remained unchanged for over 800 years.

Dr. Heckenberger, whose archeological findings were recently featured on the Discovery Channel’s 3-part series, “Lost Cities of the Amazon,” continues to work with the Kuikuru in the upper Xingu River basin. Chief Afukaka Kuikuro, who helped Heckenberger gather materials for the museum in the early 1990s, and is involved in other collaborative projects, will likely play a critical role. Because ethnographers were historically male, women’s views and artifacts got short shrift in museum research. In an effort to remedy such bias, several Kuikuro women will be included in the project.

Working around the computer. Archeologist and CMNH Research Associate Michael J. Heckenberger is second from the left. Chief Afukaká is on the right.

Kuikuro man using the mapping function on his cell phone.

What will be the outcome of this endeavor? At the very least, a small exhibit in the museum will make select artifacts accessible to the people of the Pittsburgh Region as windows into the culture of the Kuikuro. Other possibilities include an online catalog, or a large installation with visiting Kuikuro to present lectures and show the films of film-maker Takumā Kuikuro. At the very least, artifact images will be shared with the Kuikuro themselves, so that they have a record that will remain available to their craftworkers, children, and grandchildren.

These ambitious plans might not happen anytime soon. With time and funding, however, bringing these wonderful objects to the attention of the public will provide a glimpse of life in a very different world. The Kuikuro have much knowledge to share, and we’d like to be a part of making it available to the rest of the world.

Sunrise over the Xingu river, at Ipatse village.

Additional resource: The Xingu Firewall

Deborah Harding, M.A. is the Collection Manager of the Section of Anthropology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. This blog is part of Super Science Days: Scientist Takeover!

33 notes

·

View notes

Link

Mark Zuckerberg’s banned photos of indigenous Brazilians on my Facebook wall and labeled them obscene. Some of those photos were by Claude Levi-Strauss and Sebastiao Salgado, neither of whom is a pornographer. So I made a song about Zuckerberg’s attempt to obliterate, cybernetically, the remnants of indigenous Brazilian culture because it does not adhere to Judeo-Christian notions of propriety. I thought of calling the song “The Kuikuru Don’t Wear TIrousers” but I settled for “Nearly Naked While Not White.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Telematic Embrace: Visionary Theories of Art, Technology and Consciousness by Roy Ascott

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

2003

---

From Cybernetics to Telematics

The Art, Pedagogy, and Theory of Roy Ascott

Edward A. Shanken

- Frank Popper - the foremost European historian of art and technology

- Roy Ascott is recognised as “the outstanding artist in the field of telematics”

- Telematics integrates computers and telecommunications, enabling such familiar applications as electronic mail (e-mail) and automatic teller machines (ATMs).

- Ascott began developing a more expanded theory of telematics decades ago and has applied it to all aspects of his artwork, writing and teaching. He defined telematics as “computer-mediated communications networking between geographically dispersed individuals and institutions...and between the human mind and artificial systems of intelligence and perception.”

- Telematic art challenges the traditional relationship between active viewing subjects and passive art objects by creating interactive, behavioural contexts for remote aesthetic encounters.

- Synthesising recent advances in science and technology with experimental art and ancient systems of knowledge, Ascott’s visionary theory and practice aspire to enhance human consciousness and to unite minds around the world in a global telematic embrace that is greater than the sum of its parts.

- By the term “visionary”, I mean to suggest a systematic method for envisioning the future. Ascott has described his own work as “visionary”, and the word itself emphasises that his theories emerge from, and focus on, the visual discourses of art.

- While the artist draws on mystical traditions, his work is more closely allied to the technological utopianism of Filippo Marinetti than to the ecstatic religiosity of William Blake. At the same time, the humanism, spirituality, and systematic methods that characterise his practice, teaching, and theorisation of art share affinities with the Bauhaus master Wassily Kandinsky. In the tradition of futurologists like Marshall McLuhan and Buckminster Fuller, Ascott’s prescience results from applying associative reasoning to the serendipitous conjunction, or network, of insights gained from a widely interdisciplinary professional practice.

- Ascott’s synthetic method for envisioning the future is exemplified both by his independent development of interactive art and by the parallel he subsequently drew between the aesthetic principle of interactivity and the scientific theory of cybernetics.

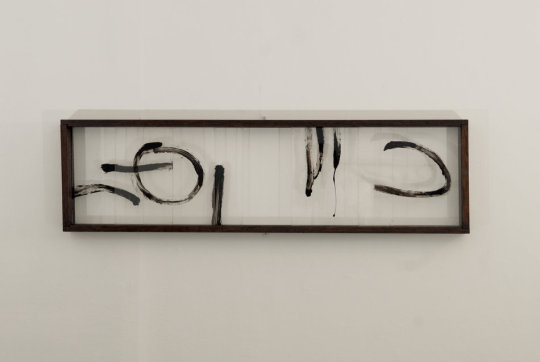

- His interactive Change Paintings, begun in 1959, joined together divergent discourses in the visual arts, along with philosophical and biological theories of duration and morphology. They featured a variable structure that enabled the composition to be rearranged interactively by viewers, who thereby became an integral part of the work.

- In 1961, Ascott began studying the science of cybernetics and recognised its congruence with his concepts of interactive art. The artist’s first publication, “The Construction of Change”, reflected an integration of these aesthetic and scientific concerns and proposed radical theories of art and education based on cybernetics. For Ascott and his students, individual artworks - and the classroom alike - came to be seen as creative systems, the behaviour of which could be altered and regulated by the interactive exchange of information via feedback loops.

- By the mid 1960s, Ascott began to consider the cultural implications of telecommunications. In “Behaviourist Art and the Cybernetic Vision”, he discussed the possibilities of artistic collaborations between participants in remote locations, interacting via electronic networks. At the same time that the initial formal concerns of conceptual art were being formulated under the rhetoric of “dematerialization”, Ascott was considering how the ethereal medium of electronic telecommunications could facilitate interactive and interdisciplinary exchanges.

- The sort of electronic exchanges that Ascott had envisioned in “Behaviourist Art and the Cybernetic Vision” were demonstrated in 1968 by the computer scientist Doug Engelbart’s NLS “oN Line System.” This computer network based at the Stanford Research Laboratory (now SRI) included “the remote participation of multiple people at various sites.”

- In 1969, ARPANET (precursor to the Internet) went into operation, sponsored by the U.S. government, but it remained the exclusive province of the defense and scientific communities for a decade.

- Ascott first went online in 1978, an encounter that turned his attention to organising his first international artists’ computer-conferencing project, “Terminal Art” (1980).

- Ascott’s early experiences of telematics resulted in the theories elaborated in his essays “Network as Artwork: The Future of Visual Arts Education” and “Art and Telematics: Towards a Network Consciousness”. Drawing on diverse sources, in the latter essay, he discussed how his telematic project “La Plissure du Texte” (1983) exemplified Roland Barthes’ theories of nonlinear narrative and intertextuality. Moreover, noting parallels between neural networks in the brain and telematic computer networks, Ascott proposed that global telematic exchange could expand human consciousness.

- He tempered this utopian vision by citing Michel Foucault’s book L’order du discours (1971), which discusses the inextricability of texts and meaning from the institutional powers that they reflect and to which they must capitulate. Consequently, the artist warned that in “the interwoven and shared text of telematics...meaning is negotiated - but it too can be the object of desire...We can expect a growing...interest in telematics on the part of controlling institutions”.

- Science and technology, for Ascott, can contribute to expanding global consciousness, but only with the help of alternative systems of knowledge, such as the I Ching (the sixth-century B.C. Taoist Book of Changes), parapsychology, Hopi and Gnostic cosmologies, and other modes of holistic thought that the artist has recognised as complementary to Western epistemological models.

- In 1982, Ascott’s telematic art project “Ten Wings” produced the first planetary throwing of the I Ching using computer conferencing. More recently, Ascott’s contact with Kuikuru pagés (shamans) and initiation into the Santo Daime community in Brazil resulted in his essay “Weaving the Shamanic Web”. Here the artist’s concept of “technoetics” again acknowledges the complementarity of technological and ritualistic methods for expanding consciousness and creating meaning.

- Ascott’s theories propose personal and social growth through technically mediated, collaborative interaction. They can be interpreted as aesthetic models for reordering cultural values and recreating the world.

- Throughout the late 20th century, corporations increasingly strategised how to use technology to expand markets and improve earnings, and academic theories of postmodernity became increasingly anti-utopian, multicultural, and cynical. During this time, Ascott remained committed to theorizing how telematic technology could being about a condition of psychical convergence throughout the world. He has cited the French philosopher Charles Fourier’s principle of “passionate attraction” as an important model for his theory of love in the telematic embrace. Passionate attraction constitutes a field that, like gravity, draws together human beings and bonds them. Ascott envisioned that telematic love would extend beyond the attraction of physical bodies. As an example of this dynamic force in telematic systems, in 1984, he described the feeling of “connection and...close community, almost intimacy...quite unlike...face-to-face meetings” that people have reported experiencing online.

- Telematics, the artist believed would expand perception and awareness by merging human and technological forms of intelligence and consciousness through networked communications. He theorised that this global telematic embrace would constitute an “infrastructure for spiritual interchange that could lead to the harmonisation and creative development of the whole planet”.

- Joining his long-standing concerns with cybernetics, telematics, and art education, he founded the Centre for Advanced Inquiry in the Interactive Arts (CAiiA). In 1995, CAiiA became the first online Ph.D. program with an emphasis on interactive art.

CYBERNETICS

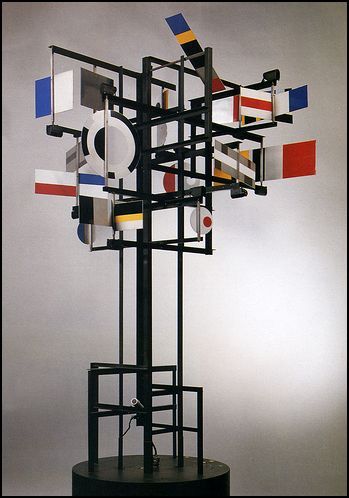

The Hungarian-born artist Nicolas Schöffer created his first cybernetic sculptures CYSP O and CYSP I (the titles of which combine the first two letters of the words “cybernetic” and “spatio-dynamique”) in 1956.

CYSP 0

CYSP 1

In 1958, scientist Abraham Moles published Théorie de l’information et perception esthétique, which outlined “the aesthetic conditions for channeling media”. Subsequently, “Cybernetic Serendipity,” an exhibition curated by Jasia Reichardt in London (1968), Washington D.C. (1969), and San Francisco (1969-70) popularized the idea of joining cybernetics with art.

Art historian David Mellor writes of the cultural attitudes and ideas that cybernetics embodied at that time in Britain. “The wired, electronic outlines of a cybernetic society became apparent to the visual imagination - an immediate future...drastically modernised by the impact of computer science. It was a technologically utopian structure of feeling, positivistic and ‘scientistic’”.

Evidence of the sentiments described by Mellor could be observed in British painting of the 1960s, especially among a group of artists associated with Roy Ascott and the Ealing College of Art, such as his colleagues Bernard Cohen and R.B. Kitty and his student Steve Willats, who founded the journal Control in 1966. Eduardo Paolozzi’s collage techniques of the early 1950s likewise “embodied the spirit of various total systems,” which may possibly have been “partially stimulated by the cross-disciplinary investigations connected with the new field of cybernetics”. Cybernetics offered these and other artists a scientific model for constructing a system of visual signs and relationships, which they attempted to achieve by utilising diagrammatic and interactive elements to create works that functioned as information systems.

THE ORIGIN AND MEANING OF CYBERNETICS

The scientific discipline of cybernetics emerged out of attempts to regulate the flow of information in feedback loops in order to predict, control, and automate the behaviour of mechanical and biological systems. Between 1942 an 1954, the Macy Conferences provided an interdisciplinary forum in which various theories of the nascent field were discussed. The result was the integration of information theory, computer models of binary information processing, and neurophysiology in order to synthesize a totalizing theory of “control and communication in the animal and the machine”.

Cybernetics offered an explanation of phenomena in terms of the exchange of information in systems. It was derived, in part, from information theory, pioneered by the mathematician Claude Shannon. By reducing information to quantifiable probabilities, Shannon developed a method to predict the accuracy with which source information could be encoded, transmitted, received and decoded. Information theory provided a model for explaining how messages flowed through feedback loops in cybernetic systems. Moreover, by treating information as a generic substance, like the zeros and ones of computer code, it enabled cybernetics to theorise parallels between the exchange of signals in electro-mechanical systems and in neural networks of humans and other animals. Cybernetics thus held great promise for creating intelligent machines, as well as for helping to unlock the mysteries of the brain and consciousness. W. Ross Ashby’s Design for a Brain (1952) and F.H. George’s The Brain as Computer (1961) are important works in this regard and suggest the early alliance between cybernetics, information theory, and the field that would come to be known as artificial intelligence.

Information in a cybernetic system is dynamically transferred and fed back among its constituent elements, each informing the others of its status, thus enabling the whole to regulate itself in order to maintain a state of operational equilibrium, or homeostasis. Cybernetics could be applied not only to industrial systems, but to social, cultural, environmental, and biological systems as well.

Much research leading to cybernetics, information theory, and computer decision-making was either explicitly or implicitly directed towards (or applicable to) military applications. During World War II, Norbert Wiener collaborated with Julian Bigelow on developing an anti-aircraft weapon that could predict the behaviour of enemy aircraft based on their prior behaviour. After the war, Wiener took an anti-militaristic stance and refused to work on defence projects.

Cybernetic research and development during the Cold War contributed to the ongoing buildup of the U.S. military-industrial complex. Indeed, the high-tech orchestration of information processing and computer-generated, telecommunicated strategies employed by the U.S. military suggests nothing short of a cybernetic war machine.

To summarize, cybernetics brings together several related propositions: (1) phenomena are fundamentally contingent; (2) the behaviour of a system can, nonetheless, be determined probabilistically; (3) animals and machines function in quite similar ways with regard to the transfer of information, so a unified theory of this process can be articulated; and (4) the behavior of humans and machines can be automated and controlled by regulating the transfer of information.

There is, in cybernetics, a fundamental shift away from the attempt to analyse either the behavior of individual machines or humans as independent phenomena. What becomes the focus of inquiry is the dynamic process by which the transfer of information among machines and/or humans alters behaviour at the systems level.

CYBERNETICS AND AESTHETICS: COMPLEMENTARY DISCOURSES

The application of cybernetics to artistic concerns depended on the desire and ability of artists to draw conceptual correspondences that joined the scientific discipline with contemporary aesthetic discourses.

The merging of cybernetics and art must be understood in the context of ongoing aesthetic experiments with duration, movement and process. Although the roots of this tendency go back further, the French impressionist painters systematically explored the durational and perceptual limits of art in novel ways that undermined the physical integrity of matter and emphasised the fleeting-ness of ocular sensation. The cubists, reinforced by Henri Bergson’s theory of durée, developed a formal language dissolving perspectival conventions and utilising found objects. (Durée - the consciousness linking past, present, and future, dissolving the diachronic appearance of categorical time, and providing a unified experience of the synchronic relatedness of continuous change). Such disruptions of perceptual expectations and discontinuities in spatial relations, combined with juxtapositions of representations of things seen and things in themselves, all contributed to suggesting metaphorical wrinkles in time and space.

The patio-temporal dimensions of consciousness were likewise fundamental to Italian futurist painting and sculpture, notably that of Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni, who were also inspired by Bergson. Like that of the cubists, their work remained static and only implied movement. Some notable early 20th-century sculpture experimented with putting visual form into actual motion, such as Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913) and Precision Optics (1920), Naum Gabo’s Kinetic Construction (1920) and Lázsló Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator (1923-30). Gabo’s work in particular, which produced a virtual volume only when activated, made motion an intrinsic quality of the art object, further emphasising temporality. In Moholy-Nagy’s kinetic work, light bounced off the gyrating object and reflected onto the floor and walls, not only pushing the temporal dimensions of sculpture, but expanding its spatial dimensions into the external environment.

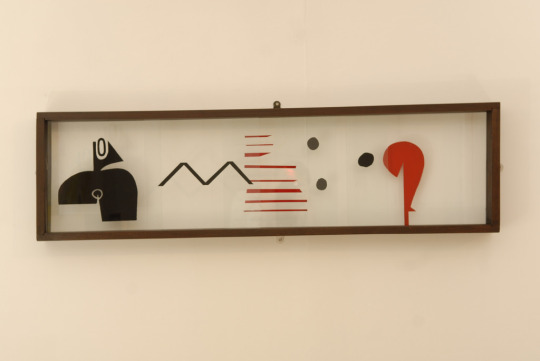

By the 1950s, experimentation with duration and motion by sculptors such as Schöffer, Jean Tinguely, Len Lye, and Takis gave rise to the broad, international movement known as kinetic art. Schöffer’s CYSP 1, for example, was programmed to respond electronically to its environment, actively involving the viewer in the temporal experience of the work. In this work, Schöffer drew on constructivist aesthetic ideas that had been developing for 3/4 of a century and intentionally merged them with the relatively new field of cybernetics. In Paris, in 1959, Romanian-born artist Daniel Spoerri founded Editions MAT (Multiplication d’Art Transformable), which published affordable multiples of work by artists such as Duchamp, Man Ray, Tinguely, and Victor Vasarely. Vasarely’s “participative boxes”, for example, included a steel frame and magnetised coloured squares and circles that “enabled the buyer to assemble his own ‘Vasarely’”.

The interactive spirit of kinetic art gave birth in the 1960s to the Nouvelle Tendance collectives. Groups such as the Groupe de Recherche d’Art visuel (GRAV) in Paris and ZERO in Germany, for example, worked with diverse media to explore various aspects of kinetic art and audience participation. Taking audience participation in the direction of political action, after 1957 the Situationist International theory of détournement (diversion) offered a strategy for how artists might alter pre-existing aesthetic and social circumstances in order to reconstruct the conditions of everyday life.

Through cross-pollination, the compositional strategy of audience engagement that emerged in Western concert music after World War II also played an important role in the creation of participatory art in the United States. Although not directly related to cybernetics, these artistic pursuits can be interpreted loosely as an independent manifestation of the aesthetic concern with the regulation of a system through the feedback of information among its elements.

The most prominent example of this tendency, the American composer John Cage’s 4′33″, premiered in 1952. Written for piano but having no notes, this piece invoked the ambient sounds of the environment (including the listener’s own breathing, a neighbour’s cough, the crumpling of a candy wrapper) as integral to its content and form. Cage’s publications and his lectures at the New School influenced numerous visual artists, notably Allan Kaprow, a founder of happenings (who was equally influenced by Pollock’s gestural abstraction), George Brecht, and Yoko Ono, whose “event scores” of the late 1950s anticipated Fluxus performance.

Robert Morris’ Box with the Sound of Its Own Making (1961) explicitly incorporated the audible process of the object’s coming into being as an integral part of the work. Morris’ 1964 exhibition at the Green Gallery featured unitary forms that invoked the viewer as an active component in the environment.

In his provocative essay “Art and Objecthood”, the art historian Michael Fried wrote disparagingly of the way minimalist sculpture created a “situation”. He interpreted this “theatrical” quality as antithetical to the essence of sculpture. The interactive quality that Fried denigrated is at the heart of Ascott’s Change Paintings and his later cybernetic artworks of the 1960s...focused attention on creating interactive situations in order to free art from aesthetic idealism by placing it in a more social context.

By the 1960s, cybernetics had become increasingly absorbed into popular consciousness. French artist Jacques Gabriel exhibited his paintings Cybernétique I and Cybernétique II in “Catastrophe”, a group show and happening organised by Jean-Jacques Lebel and Raymond Cordier in Paris in 1962. Also in 1962, Suzanne de Coninck opened the Centre d’Art cybernetic in Paris, where Ascott had a solo exhibition in 1964. Wen-Ying Tsai’s Cybernetic Sculpture (1969) consisted of stainless-steel rods that vibrated in response to patterns of light generated by a stroboscope and to the sound of participants clapping their hands.

In 1966, Nam June Paik drew a striking parallel between Buddhism and cybernetics:

Cybernated art is very important, but art for cybernated life is more important, and the latter need not be cybernated...

Cybernetics, the science of pure relations, or relationship itself, has its origin in karma...

The Buddhists also say

Karma is samsara

Relationship is metempsychosis. (Paik, 1966)

In this statement, Paik suggested that Eastern philosophy and Western science offered alternative understandings of systematic phenomena. Buddhist accounts of cosmic cycles such as samsara (the cycle of life and death) and metempsychosis (the transmigration of souls) could also be explained in terms of scientific relations by cybernetics.

Audio feedback and the use of tape loops, sound synthesis, and computer-generated composition reflected a cybernetic awareness of information, systems, and cycles. Such techniques became widespread in the 1960s, following the pioneering work of composers like Cage, Lejaren Hiller, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Iannis Xenakis in the 1960s. Perhaps most emblematically, the feedback of Jimi Hendrix’s screaming electric guitar at Woodstock (1966) appropriated the National Anthem as a countercultural battle cry.

The visual effects of electronic feedback became a focus of artistic research in the late 1960s, when video equipment first reached the consumer market. Woody and Steina Vasulka, for example, used all manner and combination of audio and visual signals to generate electronic feedback in their respective or corresponding media.

Not all artists were so enamoured with cybernetics. The artists associated with Art & Language applied scientific principles to art in a tongue-in-cheek manner, suggesting a parallel between the dogma of cybernetics and the dogma of modernist aesthetics. For example, ini the key to 22 Predicates: The French Army (1967), Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin offered a legend of abbreviations for the French Army (FA), the Collection of Men and Machines (CMM), and the Group of Regiments (GR). Using logic reminiscent of Lewis Carroll, the artists then described a variety of relationships among these elements as part of a system (of gibberish).

This ironic description mocked the manner of cybernetic explanations. It reduced to absurdity the systematisation of relationships among individuals, groups, and institutions that Ascott employed in defining his theory of a cybernetic art matrix (CAM) in the essay “Behaviorist Art and the Cybernetic Vision”. Similarly, in Harold Hurrell’s The Cybernetic Art Work That Nobody Broke (1969), a spurious computer program for interactively generating color refused to allow the user to interact beyond the rigid banality of binary input. If the user inputted a number other than 0 or 1, the program proffered the message: YOU HAVE NOTHING, OBEY INSTRUCTIONS! If the user inputted a non-number, it said there was an ERROR AT STEP 3.2.

On each plexiglas panel of Ascott’s Change Paintings was a painterly gesture that the artist conceived of as a “seed” or “ultimate shape.” Seeking to capture the essence of the phenomena of potentiality, these morphological art works may also be related to the ideas of organic development described in Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form and to the ideas of élan vital and durée developed by Bergson. The Change Paintings can be seen as an interactive visual construction in which the vital essence of the work can creatively evolve, revealing the multiple stages of its nature (as in the growth of a biological organism), over the duration of its changing compositional states. The infinite combination of these compositional transformations constituted an aesthetic unity, a metaconsciousness, or Bergsonian durée, including all its possible states in the past, present and future.

Ascott visually suggests equivalences between I Ching hexagrams, binary notation of digital computers, scatterplots of quantum probability, wave forms of information transmissions, and biomorphic shapes.

A similar convergence of methods characterises works like Cloud Template (1969) and Change Map (1969). Ascott created these sculptural paintings using aleatory methods. By throwing coins (as in casting the I Ching) on top of a sheet of plywood, chance patterns developed. The artist drew lines and curves connecting the points marked by the coins, then cut through the wood, progressively removing segments and creating an unpredictable shape. Ascott’s use of chance methods is related both to Dada and Surrealism and to the techniques of Cage, who determined parameters of his musical compositions by casting the I Ching.

At the same time, the verticality of this method shares affinities with the cartographic and horizontal qualities in the work of Pollock and Duchamp. Pollock’s decision to remove the canvas from the vertical plane of the easel and paint it on the horizontal plane of the floor, for example, altered the conventional, physical working relationship of the artist to his or her work. Similarly, Ascott’s corporeal orientation to his materials became horizontal, whereby the artist looked down on his canvas from a bird’s-eye view. This shift embodied and made explicit the ongoing reconceptualization of painting from a “window on the world” to a cosmological map of physical and metaphysical forces. The random method that Duchamp used for creating 3 Standard Stoppages (1913-14) also demanded a horizontal relationship between artist and artwork. Duchamp’s related Network of Stoppages (1914), which can be interpreted as a visual precursor to the decision trees of system theory, further offered a diagrammatic model for the interconnected visual and semantic networks of Ascott’s transparent Diagram Boxes.

For thousands of years the I Ching has been consulted on choosing a path towards the future; much more recently cybernetics emerged in part from Wiener’s military research, which attempted to anticipate the future behaviour of enemy aircraft.

TELEMATICS

Telematics, or the convergence of computers and telecommunications, is rapidly becoming ubiquitous in the developed world. Anyone who has corresponded using e-mail, surfed the World Wide Web, or withdrawn money from an automatic teller has participated in a telematic exchange.

Ascott’s theorisation of telematic art embraced the idea that any radical transformation of the social structure would emerge developmentally as the result of interactions between individuals and institutions in the process of negotiating relationships and implementing new technological structures.

Like a cybernetic system (in which information can be communicated via feedback loops between elements), telematics comprises an extensive global network in which information can flow between interconnected elements. Drawing a parallel between cybernetics and computer telecommunications, William Gibson coined the term “cyberspace” in his 1984 novel Neuromancer. Cyberspace applies a virtual location to the state of mind an individual experiences in telematic networks. Telematics implies the potential exchange of information among all nodes in the network, proposing what might amount to a decentralised yet collective state of mind. Whereas cyberspace emphasises the phenomenology of individual experience, telematics emphasises the emergence of a collective consciousness.

TELEMATICS AND ART

Telematics permits the artist to liberate art from its conventional embodiment in a physical object located in a unique geographic location. It provides a context for interactive aesthetic encounters and facilitates artistic collaborations among globally dispersed individuals. It emphasises the process of artistic creation and the systematic relationship between artist, artwork, and audience as part of a social network of communication. In addition to these qualities, Ascott argues that a distinctive feature of telematic art is the capability of computer-mediated communications to function asynchronously. Early satellite and slow-scan projects enabled interactive exchanges between participants at remote locations, but they had to take place in a strictly synchronous manner in real time; that is, all participants had to participate at the same time. In Ascott’s telematic artworks of the sae period, information could be entered at any time and place, where it became part of a database that could be accessed and transformed whenever a participant wished, from wherever there were ordinary telephone lines.

Telematic art draws on the heritage of diverse currents in experimental art after World War II, including various strains of art and technology, such as cybernetic art, kinetic art, and video art, happenings and performance art, mail art, and conceptual art. What, after all, could be more kinetic and performative than an interactive exchange between participants? What could be more technological than computer-mediated global telecommunications networks? And what could be more conceptual than the semantic questions raised by the flow of ideas and creation of meaning via the transmission of immaterial bits of digital information?

PRECURSORS

The first use of telecommunications as an artistic medium may well have occurred in 1922, when the Hungarian constructivist artist and later Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy produced his Telephone Pictures. He “ordered by telephone from a sign factory five paintings in porcelain enamel.” Their commercial method of manufacture implicitly questioned traditional notions of the isolated, individual artist and the unique, original art object.

The idea of telecommunications as an artistic medium is made more explicit in Bertolt Brecht’s theory of radio. The German dramatist’s manifesto-like essay “The Radio as an Apparatus of Communication” (1932) has offered ongoing inspiration not only to experimental radio projects but to artists working with a wide range of interactive media...Brecht sought to change radio “from its sole function as a distribution medium to a vehicle of communication [with] two-way send/receive capability.” Brecht’s essay proposed that media should

[L]et the listener speak as well as hear...bring him into a relationship instead of isolating him.

Written in the midst of the rise to power of the Nazi dictatorship, Brecht’s theory of two-way communication envisioned a less centralised and hierarchical network of communication, such that all points in the system were actively involved in producing meaning. In addition, radio was intended to serve a didactic function in the socialist society Brecht advocated.

As a variant on the two-way communication that Brecht advocated for radio, artists have utilised the postal service. While such work does not explicitly employ electronic telecommunications technology, and reaches a much smaller potential audience, it anticipated the use of computer networking in telematic art. In the early 1960s, the American artist George Brecht mailed “event cards” in order to distribute his “idea happenings” to friends outside of an art world context.

In 1968, Ray Johnson organised the first meeting of the New York Correspondence School, which expanded to become an international movement.

This postal network developed by artists explored non-traditional media, promoted an aesthetics of surprise and collaboration, challenged the boundaries of (postal) communications regulations, and bypassed the official system of art with its curatorial practices, commodification of the artwork, and judgment value...[It] became a truly international...network, with thousands of artists feverishly exchanging, transforming, and re-exchanging written and audiovisual messages in multiple media.

Mail art was especially important to artists working, not only in remote parts of South America, and even Canada, but in countries where access to contemporary Western art was severely limited, such as Eastern Europe. Many such artists also embraced telecommunications technologies, such as fax, which expanded the capabilities of mail art. In Hungary, for example, György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay founded Art Pool in the mid 1970s in order to obtain, exchange, and distribute information about international art, which was forbidden behind the Iron Curtain. Art Pool maintains an extensive physical online archive of mail and fax art.

Some of the earliest telecommunications projects attempted by visual artists emerged from the experimental art practice known as “happenings”. In Three Country Happening (1966), a collaboration between Marta Minujin in Buenos Aires, Kaprow in New York, and Wolf Vostell in Berlin, a telecommunications link was planned to connect the artists for a live, interactive exchange across three continents. Ultimately, funding for the expensive satellite connection failed to materialize, so each artist enacted his or her own happening and, as Kaprow has explained, “imagined interacting with what the others might have been doing at the same time.”

Three years later Kaprow created an interactive video happening for “The Medium Is the Medium,” a thirty-minute experimental television program produced by Fred Barzyk for the Boston public television station WBGH. Kaprow’s piece Hello (1969) utilised five television cameras and 27 monitors, connecting four remote locations over a closed-circuit television network.

Groups of people were dispatched to the various locations with instructions as to what they would say on camera, such as “hello, I see you,” when acknowledging their own image or that of a friend. Kaprow functioned as “director” in the studio control room. If someone at the airport were talking to someone at M.I.T., the picture might suddenly switch and one would be talking to doctors at the hospital.

Through his interventions as director, Kaprow was able to provide a critique of the disruptive manner by which technology mediates interaction. Hello metaphorically short-circuited the television network - and thereby called attention to the connections made between actual people.

Indeed, many early artistic experiments with television and video were, in part, motivated by a Brechtian desire to wrest the power of representation from the control of corporate media and make it available to the public. Douglas Davis’ Electronic Hokkaidim (1971) enabled television viewers to participate in a live telecast by contributing ideas and sounds via telephone. This work “linked symbiotically with its viewers whose telephoned chants, songs, and comments reversed through the set, changing and shaping images in the process”. Davis later commented: “My attempt was and is to inject two-way metaphors - via live telecasts - into our thinking process...I hope [to] make a two-way telecast function on the deepest level of communication...sending and receiving...over a network that is common property.” Davis’ work exemplifies the long and distinguished history of artistic attempts to democratise media by enabling users to participate as content-providers, rather than passive consumers of prefabricated entertainment and commercial messages.

In Expanded Cinema (1970), a classic and perceptive account of experimental art in the 1960s, the media historian Gene Youngblood has documented how some of the first interactive video installations also challenged the unidirectionality of commercial media. In works like Iris (1968) and Contact: A Cybernetic Sculpture (1969) by Les Levine and Wipe Cycle (1969) by Frank Gillette and Ira Schneider, video cameras captured various images of the viewer(s), which were fed back, often with time delays or other distortions, onto a bank of monitors. Levine noted, Iris “turns the viewer into information...Contact is a system that synthesises man with his technology...the people are the software.” Wipe Cycle was related to satellite communications, “You’re as much a piece of information as tomorrow morning’s headlines - as a viewer you make a satellite relationship to the information. And the satellite which is you is incorporated into the thing which is being sent back to the satellite.” While these works were limited to closed-loop video, they offered an unprecedented opportunity for the public to see itself as the content of television.

Significant museum exhibitions in 1969-70 also helped to popularise the use of interactive telecommunications in art. Partly in homage to Moholy-Nagy (who emigrated to Chicago after World War II), the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art organised the group exhibition “Art by Telephone” in 1969. “Artists were invited to telephone the museum with instructions for making an artwork. Dick Higgins asked that visitors be allowed to speak into a telephone, adding their voices to an ever denser ‘vocal collage.’ Dennis Oppenheim had the museum call him once a week to ask his weight. Wolf Vostell supplied telephone numbers that people could call to hear instructions for a 3-minute happening”. In 1970, Jack Burnham’s exhibition “Software, Information Technology: Its New Meaning for Art” examined how information processing could be interpreted as a metaphor for art. “Software” included Hans Haacke’s News (1969), consisting of teletype machines connected to international news service bureaus, which printed continuous scrolls of information about world events. Ted Nelson and Ned Woodman displayed Labyrinth (1970), the first public exhibition of a hypertext system. This computerised work allowed users to interactively construct nonlinear narratives through a database of information.

On July 30, 1971, the group Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) organized “Utopia Q&A”, an international telecommunications project consisting of telex stations in New York, Tokyo, Ahmedabad, India, and Stockholm. Telex (invented in 1846 was essentially mechanical, and not developed since the late 19th century) enabled the remote exchange of texts via specialised local terminals. Participants from around the world posed questions and offered prospective answers regarding changes that they anticipated would occur over the next decade. It poignantly utilised telecommunications to enable an interactive exchange across geopolitical borders and time zones, creating a global village of ideas about the future.

As an outgrowth of their “Aesthetic Research in Telecommunications” projects begun in 1975, Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz organised the “Satellite Arts Project: A Space with No Boundaries” (1977). With the support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the artists produced composite images of participants, thus enabling an interactive dance concert amongst geographically disparate performers, two in Maryland and two in California. On video monitors at these locations was a composite image of the four dancers, who coordinated their movements, mindful of the latency, or time-delay, with those of their remote partners projected on the screen.

The “Send/Receive Satellite Network” (1977) emerged from Keith Sonnier’s idea to make a work of art using satellite communications and Liza Bear’s commitment to “gaining access to publicly funded technology...[and]...establishing a two-way network among artists”. Bear brought the project to fruition, orchestrating the collaboration between the Centre for New Art Activities and the Franklin Street Arts Center in New York, Art Com/La Mamelle Inc. in San Francisco, and NASA...For three and one-half hours, participants on both coasts engaged in a two-way interactive satellite transmission, which was shown live on cable television in New York and San Francisco. An estimated audience of 25,000 saw bi-coastal discussions on the impact of new technologies on art, and improvised, interactive dance and music performances that were mixed in real time and shown on a split screen.

“Good Morning Mr. Orwell” was a satellite telecast that Nam June Paik organised on New Year’s Day, 1984. It was intended, Paik explained as a liberator and multidirectional alternative to the threat posed by “Big Brother” surveillance of the kind that George Orwell had warned of in his novel 1984: “I see video not as a dictatorial medium but as a liberating one...satellite television can cross international borders and bridge enormous cultural gaps...the best way to safeguard against the world of Orwell is to make this medium interactive so it can represent the spirit of democracy, not dictatorship.” Broadcast live from New York, Paris, and San Francisco to the United States, France, Canada, Germany, and Korea, the event reached a broad international audience and included the collaboration of John Cage, Laurie Anderson, Charlotte Moorman, and Salvador Dali among others.

EXTENSIONS: TELEMATIC ART AND THE WORLD WIDE WEB

The availability of relatively inexpensive and powerful personal computers, the creation of hypertext markup language (HTML), and the free distribution to consumers of graphical user interfaces (GUI - pronounced “goo-ey” browsers, such as Netscape Navigator and Microsoft’s Internet Explorer), all contributed to enabling the multimedia capabilities of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s.

Many artists have utilised the hyperlinking capability of the Web in order to create nonlinear text and multimedia narratives. Melinda Rackham’s “Line” (1997), for example, subtly integrated visual and textual elements. Using a simple and intuitive interface, the 17 screens of this hypermedia fairy tale about identity in cyberspace incorporated both associative connections via text and random elements via the image. A map allowed the participator to visualise where she or he was in relation to the other screens. Users were invited to submit their own personal views via e-mail, which were incorporated into the work, adding intimacy and complexity.

Eduardo Kac has created numerous “telepresence” works involving the interaction between humans, machines, plants, and animals. He defines “telepresence” as the experience of being physically present and having one’s own point of view at a remote location. His “Essay Concerning Human Understanding” (1995), created in collaboration with Ikuo Nakamura, used telematics in a telepresence installation in order to facilitate remote communication between nonhumans, in this case, a canary in Kentucky and a philodendron plant in New York. As Kac explained:

An electrode was placed on the plant’s leaf to sense its response to the singing of the bird. The voltage fluctuation of the plant was monitored through a [computer] running software called Interactive Brain-Wave analyser. This information was fed into another [computer]...which controlled a MIDI sequencer. The electronic sounds [sent from the plant to the bird] were pre-recorded, but the order and the duration were determined in real time by the plant’s response to the singing of the bird.

Although the work spotlighted the process of communication between the bird and the plant, Kac noted that humans interacted with the bird and the plant as well, causing the bird to sing more or less, and the plant to activate a greater or fewer number of sounds. In this way, humans, plant, and bird became part of a cybernetic system of interrelated feedback loops, each affecting the behaviour of the other and the system as a whole.

Since commencing his controversial suspension performances in 1976, perhaps no artist has challenged the physical limits of the body with respect to technology more than Stelarc. In Ping Body, first performed on April 10, 1996, in Sydney, he wired his body and his robotic “Third Hand” to the Internet, and allowed variations in the global transfer of online information to trigger involuntary physiological responses. The artist’s arms and legs jerked in an exotic and frightening dance. As he explained:

The Internet...provide[s]...the possibility of an external nervous system which may be able to telematically scale up the body to new sensory experiences. For example when, in the Ping Body performance, the body’s musculature is driven by the ebb and flow of Internet activity, it’s as if the body has been telematically scaled up and is a kind of “sensor” or “nexus” manifesting this external data flow.

Ping Body conflated the standard active-passive relationship of human to machine. While, ultimately, the artist was the master of his work, he permitted his body to be a slave to more or less random exchange of amorphous data on the Internet. At the same time, Stelarc retained control over a robotic arm activated by muscle contractions in his body. As in most of Stelarc’s work, the artist remained the central performer/subject of the piece.

As a final example of Web-based art beyond the Internet, “TechnoSphere,” spearheaded by Jane Prophet beginning in 1995, combined telematics and artificial life, using the Web as an interface to an evolution simulator that enables users to create their own creatures and monitor them as they grow, evolve, and die in a virtual three-dimensional environment. A series of menus allowed users to select attributes to create an artificial life form that entered the virtual world of “TechnoSphere” and competed for survival and reproduction. Users selected various physical features (eyes, mouths, motility, and so on), chose between herbivorous or carnivorous feeding, and assigned a name to the creature they had parented. The condition and activities of each creature - its weight, battles with other creatures, reproductive success, and so on - were calculated using natural selection algorithms, and the creator was periodically e-mailed updates on his or her offspring’s status. It shared many concerns including biological morphology, interactivity, systematic feedback, and telematic connectivity.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

‘Kuarup’, o ritual mais encenado da história do Festival de Parintins

Publicado em https://parintinsnoticias.com/kuarup-o-ritual-mais-encenado-da-historia-do-festival-de-parintins/

‘Kuarup’, o ritual mais encenado da história do Festival de Parintins

Pela oitava vez, Kuarup, cerimônia feita em homenagem aos mortos ancestrais das tribos Kamayurás, Waurá, Kuikuru, Mehinaku e, outras etnias da região do Parque Nacional do Xingu, será encenada na arena do Bumbódromo.

Esta será quinta vez que o Boi Garantido vai levar a história para a arena do Bumbódromo. Outras três, pelo Caprichoso. O rito é centrado na figura do pajé Mavutsinin, que teria tentado ressuscitar seus entes mortos usando troncos de madeira, que seriam transformados para receber estas vidas.

Os índios acreditam que através do Kuarup, as almas dos mortos vão se libertar e viver em outro mundo. O rito, também é uma forma de celebrar a despedida dos mostos e encerramento do período de luto.

A celebração, corresponde à cerimônia de finados, dos brancos. Entretanto, o Kuarup é uma festa alegre, onde cada um coloca a sua melhor vestimenta na pele, conforme o trecho da letra da toada deste ano do Garantido, “Kuarup – a festa dos mortos”, dos compositores Marlon Brandão, Moisés Amazonas, Valdenor dos Santos e Vanílson Oliveira: “Clã da onça-pintada, Clã da serpente sucuri… Clã da arara vermelha, Cantam as tribos na aldeia, É dança, é festa no Xingu”. Na visão dos índios, os mortos não querem ver os vivos agindo de forma combalida ou reprimida.

Resistência

Uma destas cerimônias realizadas, como também descreve o trecho da letra da mesma toada, foi feita em homenagem a um dos maiores sertanistas do Brasil, Orlando Villas-Bôas, defensor dos povos indígenas.

Se não fosse o trabalho de toda a vida dos irmãos Villa-Boas, hoje na divisa do Planalto Central com a Amazônia teríamos um deserto, com a terra exaurida por pastagens e plantações de soja ou cana de açúcar.

Por esses motivos, o Kuarup feito em homenagem a Orlando foi a maior honraria que um caraíba (homem branco) poderia receber. Em 2003, mais de dois mil índios vindos de diversas regiões se concentraram na aldeia Yawalapiti para celebrar o que eles mesmos consideraram o maior Kuarup já realizado na região.

Orlando foi indicado duas vezes ao Prêmio Nobel da Paz por Julian Huxlei e Claude Lévi-Strauss.

Enfim, o ritual que será encenado em uma das três noites de apresentação do Boi Garantido, pretende expor os desafios do povos do Xingu vinculado ao plano espiritual, para manter viva a chama das crenças e costumes indígenas.

Oito vezes Kuarup

O ritual “Kuarup, a festa dos mortos”, que será apresentado este ano pelo Garantido, já teve outras quatro exibições feitas na arena do Bumbódromo: Ritual Decameron Kuarup (1996), Kuarup (1999), Ritual Kuarup (2011) e, em 2015, com a toada de 1999.

Além das cinco encenações no Garantido, houve outras três no Boi Caprichoso, com Yoparanã (1996), Kuarup, tronco sagrado (2004), A Mística Xinguana (2012), encenação tribal diante de módulos alegóricos. As histórias dos ritos e lendas dos Ianomâmis, Karajás e Parintintins, são as que mais se aproximam de Kuarup em apresentações no Festival.

Fonte: Por Náferson Cruz | BNC AMAZONAS/TOADAS

0 notes

Text

The Lost Cities Of The Amazon

https://youtu.be/b6z1tmkPSg8 Following famous Amazon explorer Col. Percy Fawcett's trail to the point of his last known location deep into Brazil's Mato Grosso region, Josh Bernstein and University of Florida's Michael Heckenberger take buses, planes, trucks and river boats five days deep into areas of massive deforestation until they finally reach the untouched jungle. There, among a people called the Kuikuru, they discover the archaeological evidence that points - not only to the existence of huge cities in the jungle - but also to the fact that their descendants are still very much alive today.

More Quality Content

0 notes