#anio river

Text

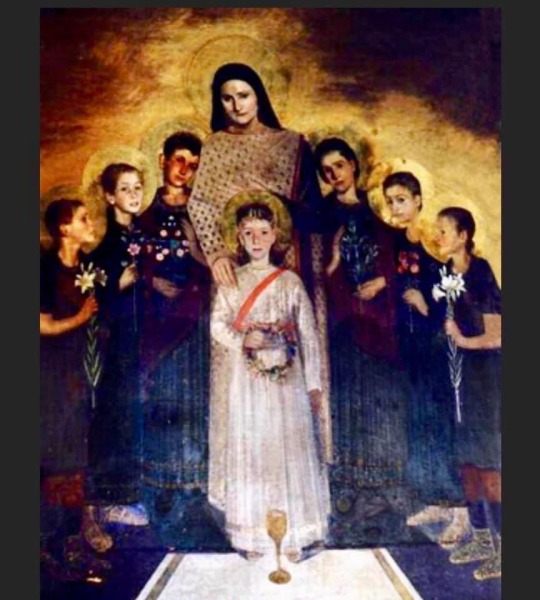

Today the Church remembers a family of ten early Roman Christian martyrs, who in their lives, and in the case of seven in their youth, manifested more than firmness in the confession of the true Faith. Their names were, Crescentius, Julianus, Nemesius, Primitivus, Justinus, Stacteus, and Eugenius. Symphorosa, their holy and not less heroic mother, was a native of Rome, and wife of Getulius, a Roman consul.

Orate pro nobis.

Symphorosa (died circa AD 138) is venerated as a saint of the Church. According to tradition, she was martyred with her seven sons at Tibur (present Tivoli, Lazio, Italy) toward the end of the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-38).

When Emperor Hadrian had completed his costly palace at Tibur and began its dedication by offering pagan sacrifices, he received the following locution from the pagan gods: "The widow Symphorosa and her sons torment us daily by invoking their God. If she and her sons offer sacrifice, we promise to give you all that you ask for."

When all of the Emperor's attempts to induce Symphorosa and her sons to sacrifice to the pagan Roman gods were unsuccessful, he ordered her to be brought to the Temple of Hercules, where, after various tortures, she was thrown into the Anio River with a heavy rock fastened to her neck.

Her brother Eugenius, who was a member of the council of Tibur, buried her in the outskirts of the city.

The next day, the emperor summoned Symphorosa's seven sons, and being equally unsuccessful in his attempts to make them sacrifice to the gods, he ordered them to be tied to seven stakes erected for the purpose round the Temple of Hercules. Their members were disjointed with windlasses.

Then, each of them suffered a different kind of martyrdom. Crescens was pierced through the throat, Julian through the breast, Nemesius through the heart, Primitivus was wounded at the navel, Justinus was pierced through the back, Stracteus (Stacteus, Estacteus) was wounded at the side, and Eugenius was cleft in two parts from top to bottom.

Their bodies were thrown en masse into a deep ditch at a place the pagan priests afterwards called Ad septem Biothanatos (the Greek word biodanatos, or rather biaiodanatos, was employed for self-murderers and, by the pagans, applied to Christians who suffered martyrdom). Hereupon the persecution ceased for one year and six months, during which period the bodies of the martyrs were buried on the Via Tiburtina, eight or nine miles from Rome.

Almighty God, who gave to your servants Symphorosa and her family the boldness to confess the Name of our Savior Jesus Christ before the rulers of this world, and courage to die for this faith: Grant that we may always be ready to give a reason for the hope that is in us, and to suffer gladly for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever.

Amen.

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ponte Nomentano and River Anio, c.1870

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Bathers, Souvenir of the Banks of the Anio River at Tivoli, Théodore Caruelle d' Aligny , c. 1860/1861, Cleveland Museum of Art: Modern European Painting and Sculpture

Although painted in France, this work depicts bathers near Tivoli, a popular, parklike estate near Rome, famous for its fountains, picturesque hills, and lush forests. As was the custom for many artists of the 19th century, d'Aligny traveled to Italy to study. He remained there from 1825 until 1827, making careful drawings and oil sketches directly from the Roman countryside. He would often use these works to compose more finished paintings in his studio. Although d'Aligny visited Italy twice more, his last trip was in 1843. This painting, made years after that date, is therefore a true souvenir, that is, a recollection evoking his experiences in Italy

Size: Framed: 58.5 x 60.5 x 8 cm (23 1/16 x 23 13/16 x 3 1/8 in.); Unframed: 37.5 x 41 cm (14 3/4 x 16 1/8 in.)

Medium: oil on wood panel

https://clevelandart.org/art/1980.4

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Roman Infastructure

Although Ancient Rome had a heavy influence on growth and expansion throughout provinces, wealth and citizens, they didn't just focus on that. Dating back, Ancient Greece sought to expand on similar things but also took focus on its infrastructure. With different styles of architecture on the acropolis like in the Parthenon and Erechtheion, Greece managed to set infrastructure standards that different ancient worlds could live with.

Again, much like the Greeks, Roman architecture was very similar. Paying attention to detail, and perfection, Rome also implement various similar styles like ionic, doric and corinthian columns. Also, the inside buildings normally had gigantic porticos (large open spaces). This mainly was prevalent in the Pantheon, a building that is still standing today!

Going into the plumbing of Ancient Rome, the population at a certain point was up to 1 million living in the actual city. Because there were so many people who needed water, the city was in desperate need of a good water transportation system. The infrastructure was built mainly with aqueducts. An aqueduct is similar to a pipe in the sense that it carries water from one place to another. Specifically, Rome got its source of water from various springs in the Anio valley. Unlike a pipe though which uses pressure for transportation, Romans weren't extremely technologically advanced which made them use their surroundings. Gravity made the water go from one place to another, with the water source starting at a higher altitude than it ended at.

Plumbing was implemented in society too! Communal bathrooms, also know as public latrines, for the lower class meant that the sewage flowed in a stream to a flowing river or stream outside of the city. A very similar type of plumbing system but only now, the sewage is transported to a sewage waste plant where they disinfect feces so that the water can be used again.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Away and Under the Weather: Part 3

This is it. My final and, in my opinion, WORST illness-related experience abroad. It actually involves a few different illnesses and was spread out over at least a month. It was painful, exhausting, and just bizarre. Enjoy!

#1 It started with the flu...

It started with the flu. Nothing special, just the flu. When you live in another country AND work with children, you're going to get sick now and then. It was around this time of year (April) in 2007. I don't even remember how bad a flu it was. I probably had a fever, some body aches and a runny nose. That's usually what I get. I taught lessons through it (as usual) and it was over. I didn't need to go to the doctor until later.

The flu ended but the crap in my lungs never really went away. After a week or two of wheezing and coughing, I went to get checked out. At the hospital, I was shown around by my own English-speaking nurse to see two specialists and got an x-ray of my lungs. It cost less than US$50. (I miss Korea.) I had acute bronchitis. The flu had slightly inflamed my bronchial tubes and there was a little infection. They gave me antibiotics, pain pills, something for the mucus, and anti-inflammatory medicine.

Getting treated in Korea by western medicine is different than at home. Korean hospitals also treated people using eastern medicine and I took advantage of that more after this experience. Eastern medicine is about treating the delicate balance that exists in your body and allowing your body to function at its peak potential. Western medicine works more like a band aid. You're hurt here; fix here. Western medicine in Korea takes this metaphor even further. Sick? In pain? Appendages double in size? Okay! What can we do to patch you up and get you back to work?

On top of that, we really do blindly trust doctors a lot. Which is fine for the complicated stuff. But in Korea, you barely even know what medicine you're taking. They give me the list but there's a lot on there and it's hard to tell the pills apart. They prepare all the pills for you and separate them by dose in these long strips of vacuum sealed plastic baggies. Swallow the cocktail and get back to work. No need to wait for the effects to kick in.

I can tell you that I took my first baggie on a Wednesday night or Thursday morning. I remember that because by Friday I was calling the nurse and taking the only sick leave I ever took in 3 years in Korea.

I felt a little off on Thursday. Not sick, just off. So it took me (and my head teacher/neighbor who was walking home with me) completely by surprise when I randomly puked on the street Thursday night. I barely made it to the storm drain let alone even thinking about trying to find a toilet. Living abroad, I've had my share of food poisonings so the idea that my body was rejecting something was not foreign to me. But there was no food. It was like a hangover without the bliss of being an idiot the night before.

Since it wasn't food, I assumed pills and called the nurse. I stopped taking all of them since I didn't know which was which in my poison cocktail. I didn't feel any better the next day as I started to have stomach problems come out the other end. Great. And remember how I couldn't have sick days? That was especially true my first year when our numbers were already small and there were teachers fleeing the country in the middle of the night every other week. Fortunately, though, through some luck--and a lot of pity from my head teacher and principal who watched me try to teach my 4pm-7pm elementary class from a chair when I wasn't running to the bathroom--my head teacher had her second three-hour slot free and taught my 7pm-10pm middle school class.

So I went home and proceeded to have my worst weekend ever. I was supposed to be at a wedding. Instead, every three hours (like clockwork!) I crawled the three feet from my bed to the bathroom and then tried crawl back, dragging what was left of my tattered stomach on the floor. Eventually that was too much and I brought a pillow and blanket into the bathroom to sleep on the floor in between sessions. I didn't leave the house until Sunday afternoon. I limped across the street to get some saltines and electrolytes with some hope that I would be better before Monday.

And, surprisingly, I was. My stomach was convinced everything was out that it didn't like and it stopped trying to kill me. On Monday, I was exhausted, soar, and really cranky but I was mobile enough to go down the hill to my work. I settled in my chair to be a white-faced, native speaker in front of 15 Korean kids for 6 hours. The kids were extra nice and the next few days went fine. Although, it still amazes me that the kids never viewed this behavior as strange. I could not stand most of the time and could barely speak but I was still there. Even now in Hong Kong, I often teach while wearing a doctor's mask when I have a cough or runny nose, and I have some kids come to EVERY class in a mask. Sick? Wrap it, cover it up, take a pill. But do it at work.

In this case though, the pills were the problem. I talked to my mom on Skype later and she told me that it was probably the anti-inflammatory medicine. She used to work for a doctor and patients often called and complained of stomach problems when the doctor prescribed anti-inflammatory medicine. So that was it. The weekend was more than enough to learn my lesson. The body is connected, beware of pills, listen to your mother, work somewhere with sick days, bla, bla, bla... Teacher, finishee?? Anio.

I got better and started to regale my friends with gross stories of the worst weekend ever. Around midweek, I decided that I was better enough to not cancel my rafting trip for the coming weekend. It was rafting in Korea, after all, which is only slightly more intense than floating down a lazy-river. It was mostly an excuse to drink somewhere else and also to watch a traditional Korean mask performance.

Rafting was scheduled for Sunday so we watched the mask dance on Saturday. It was in a very cool theatre-in-the-round, and--despite not understanding a word they were saying--it was really funny! There was an ajumma character which is always a riot and at one point a guy pretended to cut off the fake bull's penis. It was an outdoor theater, and it was really hot, so most people sat in the shaded section. About 30 of us came on the trip and showed up late so a few of us sat in the sun so we could watch from the front row.

It was really bright when I first stared down at my feet so I just thought I was seeing things. They felt a little strange and warm, but so did the rest of me. And I was wearing larger flip-flops so I wasn't uncomfortable. I felt a little stupid but I turned to my friend and said it anyway, "Do my feet look bigger to you?"

I'm not sure if she could see or if she was just a little worried about the question I just asked but we needed a closer look. We walked around the edge of the seating and went outside to where it was shaded and we could see better. And there they were: cankles. I grew cankles in an afternoon! There was a weird fluster next as three of my friends and I tried to figure out what to do for a case of instant-fat-feet. I lay down on the ground and elevated them, someone put a cold water bottle on them, but mostly we just poked them a lot as if we were suddenly going to able to diagnose the problem.

I freaked out for a while as they seemed to get bigger in the heat. Fortunately, they grew to certain size and stopped. They didn't hurt and I could walk. I didn't go to a doctor because I was where I usually was when stuff like this happens: in a village in a foreign country.

The play ended and after some shopping we all got on the buses to go back to the place we were staying. A few more people got to see my exciting new development. Most of the theories tossed around that day had to do with the bus going up and down the hills and something with altitude. I kept them elevated and took some allergy pills or something. I even went rafting the next day. (Seriously, easy rafting.) I just kept showing people my fat feet hoping someone could tell me what was happening to me.

Monday I went to work, fat feet and all. I got a kick out of freaking out the kids with my cankles. (It actually freaked out the other teachers and staff more.) They were still there a week later when my parents arrived in Korea. I'm sure it was a great sight for my mother, who hadn't seen me in nine months. Because that's what you want to see when your oldest child is all alone for the first time and on the other side of the world. That she's becoming deformed.

My dad made me sleep in his special airplane socks that are supposed to give you even circulation and they started to really go down. Mom cleaned my apartment which was not in an acceptable state (is it ever?). I took my first real vacation since I arrived in Korea and relaxed in Jeju-do. It took some time but they went back to normal and I was all better.

Finally, we sat down together with the Internet and tried to figure out why my feet blew up. (Mom is an experienced hiker and didn't buy the 'altitude' theory.) And there, at the bottom of the list, on some medical website under possible causes for swollen feet it said, "...may be caused by anti-inflammatory medicine."

So that was it. I got the flu which gave me bronchitis that led to the worst weekend of my life followed by one of the weirdest. The lesson for all this is very simple and not at all original: Stuff happens. I did what I was supposed to. I was sick so I went to the doctor. Usually that's the end. Take the pills, drink some liquids, all better. Only this time the pills poisoned me, my stomach tried to kill me, and my feet doubled in size. The good experience that came out of this was that the next time I was sick, I was really willing to try acupuncture and Korean traditional medicine. Also, I try not to suck down pills like candy. My feet are big enough already.

Unfortunately, I know this is not the end. Despite Hong Kong being more western than Korea and having more resources than Buenos Aires, I know it will happen again. You get sick, you fall down; drink your fluids, pick yourself up.

It's just different when you don't speak the language.

**********

Again, this is old content I wrote about nearly 10 years ago for another blog (http://laurabusan.blogspot.com/). It’s time I start writing again and bringing everything together.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Traces

Anio

.

‘‘ML: You do something with architectural means that makes an obsolete reality present again.

PZ: I think it is more about creating a feeling for the things that are absent than about creating a feeling of presence for things lost. So I try to create a feeling for things that are no longer here or for the lost context of things that are still here.’’

Peter Zumthor and Mari Lending - A Feeling of History

Allmannajuvet Zinc Mine Museum in Sauda - Peter Zumthor

As a child I rarely took the tube. But when I did, I found it a hostile environment; the artificial light, or better said the lack of natural light, the unrealistic fear of falling on the train tracks, the lack of anything to do while waiting. As I grew up I had to start taking the metro in Bucharest. I remember going to drawing lessons from school, and in winter, when I was coming back, it was right at that time of day when the light is dimming. 5 minute wait, 12 minute ride, 4 stations, and when I’m out its pitch dark. I find it the closest mean of transport to teleportation.

Imagine yourself in a city where you’ve never been before in an underground station. Remove from your mental image the station sign, the clock (including the line monitor) and the posters. Now you find yourself in any station of that city, at any time of the day, at any time of the year, in any year since the station was build; it’s a feeling of atemporality and a-spatiality. Most underground stations are quite sterile spaces, they are utility constructions that are guided by the laws of efficiency. The materials used are durable and don’t show signs of weathering - glazed tiles, metal or plastic seats, rubbery paint; they are materials that don’t absorb any memories, except of their initial moment(from station to station they vary slightly in fashion according to the time they were built).

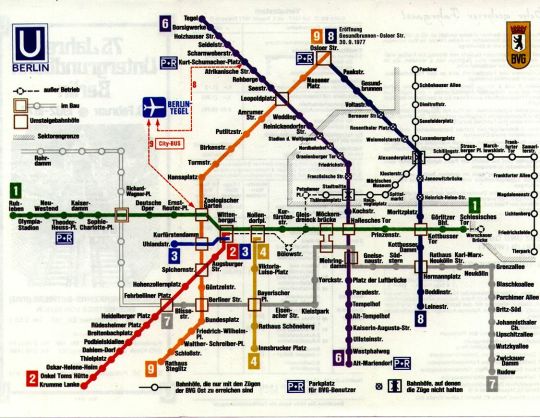

Berlin underground stations closely respects this morphology (I will be referring as underground stations to both U-Bahn and S-Bahn stations that are in the underground). Built at the beginning of the 20th century, with a rapid growth up until the Second World War, and further, after the separation of the city, Berlin underground system(and overground) was and is an ever changing fingerprint of the city. From the lines’ web to the specific sign and lettering it is a system, or better said the circulation of the city’s body particular for Berlin and only for Berlin. Even though it respects the guidelines on which a metro is built, it can only tell the story of Berlin. One distinctive aspect to be noted about German underground stations is that you don’t have any form of physical barriers when accessing the platform; in this way I would argue that the stations become extensions of the streets and the ‘no questions asked’ public space. It acts primarily as part of the transport scheme, but auxiliary it undertakes non-direct characteristics of shelters, meeting spaces and shortcuts in the urban scape.

As a downfall, Berlin underground stations develop as more than shady places. For instance, the film ‘Christiane F. - Wir kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo’ - 1981 (Christiane F. - Us children from Bahnhof Zoo) focuses on a group of West Berlin teenagers who get addicted to heroin. They’re place of hangout is an U-Bahn station around which are depicted scenes of drug dealing, violence and prostitution. Another example, is set in East Berlin in the film ‘Coming out’ focused on the LGBT community in an oppressive regime(the film first airs publicly the night Berlin wall fell). One of the scenes shows a man being beaten up by a group of people in a tube station for looking distinctive.

From ‘Christiane F. - Wir kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo’

From a historic point of view, Berlin underground bears marks and tears, nowadays mostly concealed or erased, of the city’s life. In WW2 part of the tube stations served as air-raid shelters and housed military wounded in trains on underground sidings. In the final Battle of Berlin, on 2 May 1945, the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel (a major service line) gets flooded, leaving behind an unknown number of casualties, making it paradoxically a safe space and a death trap.

The night commencing the 13th of August 1961, underground passengers were the first to experience the division of the city. The late-night trains started stopping at the boundary between sectors, travellers were brought to the side they belonged to, and outside there was the wall. In the following years to come, the whole metro system got separated, cut in two, being another form of disruption. Bearing this in mind, it had its blind spots, small inaccuracies given by the complexity of the rail system, both physical and political.

Certain lines(U6, U8 and S2), primarily in the West were still running under sections of Eastern ground. This services were not interrupted, but it was decided to continue working without stopping in Eastern stations. They become ‘ghost stations’; on western maps they are crossed out, while on eastern maps they disappear all together, access being sealed and guards permanently surveying them from newly built concrete booths. In 1989, shortly after Berlin wall fell, Max Gold films one of the ghost stations(Potsdamer Platz). In the video you can see the station, in a form of weathering and decay through lack of use, but at the same time it is frozen in time in 1961. There are not many differences to any other station in Berlin, besides the old posters and the guard booth, but it is covered in thick dust and tiles are falling off the wall. In 1992, Potsdamer Platz S-Bahn station is the last ghost station to reopen, after the restoration of the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel. The station looks awfully a lot as it looks in the 1989 footage, even the white tiles covering the concrete columns are kept the same, making it almost impossible to distinguish if you’re in 1961 or 1992 or 2019.

Potzdamer Platz S-Bahn Station in 1989

U-Bahn map West Berlin

S-Bahn and U-Bahn map East Berlin

I’ve set as a direction for ‘Traces’ the insertion or change of an element in the Potsdamer Platz S-Bahn station that gives it a sense of temporality and spatial distinction, while alluding to its memory, without reconstructing it in any forward manner. By decomposing the station into component parts I focused on identifying the bit that interacts with the largest amount of people, that realistically, is touched, directly or indirectly, by anybody who passes through the space; and that would be the pavement/flooring. What I would find as being the three pieces characteristic for a metro station flooring are the general waiting area, the delimitation strip (for example the yellow line in London) and the space between the delimitation line and the track lines, where you are not allowed to step if the train isn’t in the station. This structure triggered my interest, as it creates a visual and tactile language that communicates to you through changes in colour and texture.

Materiality, Form and Sizing

After watching Adrian Forty’s lecture on his book ‘Concrete and culture’ I have reinforced my idea of concrete as a suited material for my endeavour. He argues for the multiple dualities of concrete; natural-artificial, historic-unhistoric, universal-local, memory-amnesia etc. Moreover, I took as inspiration Rachel Whiteread’s approach on concrete as a material that can embed the memory of an object, while creating an identity of its own. Through experiments, I have tested how different compositions of concrete get set or altered by the use of textiles. The indentations are generally made by using my fingertips not only to show how concrete can be easily manipulated, emphasising the antithesis between solidity and fragility, but also to give a scale for the striations that are meant to be felt while not being dangerous(if you’re not wearing stilettos). The patterns create shadows that give relief to the station, moving it away from a 2D register of materials.

The pavement is able to store information such as the weather outside, or the time of year, while being quite durable and easy to maintain. It might resemble to the eye the side of a river where there used to be water, suggesting the tunnel’s flooding (Potsdamer Platz was and is part of the Nord-Süd-Bahn tunnel). The liminal bit is rougher making a visual statement of danger and brittleness, while the demarcation strip is set in wood and stuck in using mortar, talking about an old ‘doorstep’, that was hard to place, but effortlessly removed. The model is 40cm x 64cm so it can be tested. The liminal bit and the strip will rarely be stepped on as they have a width of 24cm while an average step from heel to heel is 76cm, leaving an untouched space.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Italian Landscape in the Valley of the Aniene River with the Waterfalls of Tivoli by Cornelis Apostool, Museum of the Netherlands

Italiaans landschap met het dal van de Anio en de watervallen van Tivoli.

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/nl/collectie/SK-A-1681

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Text

Today the Church remembers a family of ten early Roman Christian martyrs, who in their lives, and in the case of seven in their youth, manifested more than firmness in the confession of the true Faith. Their names were, Crescentius, Julianus, Nemesius, Primitivus, Justinus, Stacteus, and Eugenius. Symphorosa, their holy and not less heroic mother, was a native of Rome, and wife of Getulius, a Roman consul.

Orate pro nobis.

Symphorosa (died circa AD 138) is venerated as a saint of the Church. According to tradition, she was martyred with her seven sons at Tibur (present Tivoli, Lazio, Italy) toward the end of the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (AD 117-38).

When Emperor Hadrian had completed his costly palace at Tibur and began its dedication by offering pagan sacrifices, he received the following locution from the pagan gods: "The widow Symphorosa and her sons torment us daily by invoking their God. If she and her sons offer sacrifice, we promise to give you all that you ask for."

When all of the Emperor's attempts to induce Symphorosa and her sons to sacrifice to the pagan Roman gods were unsuccessful, he ordered her to be brought to the Temple of Hercules, where, after various tortures, she was thrown into the Anio River with a heavy rock fastened to her neck.

Her brother Eugenius, who was a member of the council of Tibur, buried her in the outskirts of the city.

The next day, the emperor summoned Symphorosa's seven sons, and being equally unsuccessful in his attempts to make them sacrifice to the gods, he ordered them to be tied to seven stakes erected for the purpose round the Temple of Hercules. Their members were disjointed with windlasses.

Then, each of them suffered a different kind of martyrdom. Crescens was pierced through the throat, Julian through the breast, Nemesius through the heart, Primitivus was wounded at the navel, Justinus was pierced through the back, Stracteus (Stacteus, Estacteus) was wounded at the side, and Eugenius was cleft in two parts from top to bottom.

Their bodies were thrown en masse into a deep ditch at a place the pagan priests afterwards called Ad septem Biothanatos (the Greek word biodanatos, or rather biaiodanatos, was employed for self-murderers and, by the pagans, applied to Christians who suffered martyrdom). Hereupon the persecution ceased for one year and six months, during which period the bodies of the martyrs were buried on the Via Tiburtina, eight or nine miles from Rome.

Almighty God, who gave to your servants Symphorosa and her family the boldness to confess the Name of our Savior Jesus Christ before the rulers of this world, and courage to die for this faith: Grant that we may always be ready to give a reason for the hope that is in us, and to suffer gladly for the sake of our Lord Jesus Christ; who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, forever and ever.

Amen.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Photo

The Bathers, Souvenir of the Banks of the Anio River at Tivoli, Théodore Caruelle d' Aligny , c. 1860/1861, Cleveland Museum of Art: Modern European Painting and Sculpture

Although painted in France, this work depicts bathers near Tivoli, a popular, parklike estate near Rome, famous for its fountains, picturesque hills, and lush forests. As was the custom for many artists of the 19th century, d'Aligny traveled to Italy to study. He remained there from 1825 until 1827, making careful drawings and oil sketches directly from the Roman countryside. He would often use these works to compose more finished paintings in his studio. Although d'Aligny visited Italy twice more, his last trip was in 1843. This painting, made years after that date, is therefore a true souvenir, that is, a recollection evoking his experiences in Italy

Size: Framed: 58.5 x 60.5 x 8 cm (23 1/16 x 23 13/16 x 3 1/8 in.); Unframed: 37.5 x 41 cm (14 3/4 x 16 1/8 in.)

Medium: oil on wood panel

https://clevelandart.org/art/1980.4

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes

Photo

Such as Gundila

This disposition still favored the rich, such as Gundila—those who had something left—over those who had been forcibly uprooted and fobbed off with a pittance. Someone who could keep a low profile, however, could very often succeed in hanging on to what he had owned, especially if he and his family had remained in a particular place for all the years since Odoacer and Theoderic entered Italy. A man like that who had been calling himself a Goth under Theoderic’s successors may just have forgotten to answer to this label any longer.

One windfall came to the church, naturally, when Arian church lands were confiscated and made over to the orthodox church. We know of surprisingly few such Arian churches—especially if one considered Theoderic’s Italy an Arian, Gothic kingdom—but they faded away quickly at this moment.

Power began to fragment. Provincial governors—there would be a dozen in Italy at one moment now—could be nominated locally by the traditional local luminaries, but also by bishops. Tax collection, moreover, now devolved away from Ravenna and fell to the hands of the governors. Troops were to be provided for gently, as it were, by purchases of food and goods at market prices, not by tax, confiscation, or forced sale; and it was stipulated that in the toe and heel of Italy’s boot, such purchases could be made only at the regular public markets. Civil law was to be restored, but in the absence of a strong central administration, this meant effectively the drumhead justice of local potentates, in some places generous and wise, in others doubtless extortionate and cruel.

On a bridge over the Anio River

The city of Rome was to be brought back to life. On a bridge over the Anio River not far outside the city’s walls, an inscription made in 56512 speaks of “the restoration of the liberty of the city of Rome and the whole of Italy.” When Boethius was executed for hoping for “liberty for Rome,” he could scarcely have had this in mind. Free grain for the citizenry and subsidies for the fine professors of the liberal arts were ensured at Rome, as well as funds for the repair of public buildings and aqueducts. We know that the old schools in which those professors taught were on their last legs by now. Of other restorations, there is not much evidence customized tours balkan.

Ravenna told a different story. There, an infusion of energy and subsidy from the east kept the city’s golden age alive a little longer. Theoderic’s capital had seen art and architecture of substance and value, but it was now Bishop Maximian, placed in power in the church there under Belisarius in 546 and remaining until 556, who became the senior churchman in Italy in the absence of Vigilius and brought the new capital to architectural glory. Maximian was the first bishop of Ravenna to be called archbishop, and his rise is a sign of Constantinople’s willingness to turn away from the city of Rome, which was socially messy, indefensible, and (from Constantinople) hard to reach. Ambitious building had continued past Theoderic’s death, and his tomb and the great church of San Apollinare Nuovo reflect the wealth and very Roman taste and style of that generation. We wish Theoderic’s palace, an elaboration of what he found on arrival, had survived as more than a faint rumor. A banker, Julian, dedicated a new church to Saint Michael the archangel and finished it before Maximian became bishop.

Gervase and Protase

At the same time, a greater church had been abuilding from 526, dedicated to Saint Vitale, a bogus patron of the local church. Vitale was the father of saints Gervase and Protase, who had been martyred under the last of the bad emperors before Constantine. Their bodies had been conveniently discovered by Saint Ambrose in the 380s and played a dramatic role in solidifying the authority of the Nicene bishop in Milan when Arian forces seemed destined to prevail.13 According to the legend in Ravenna, all three had been martyred on the site there where the church in honor of the father would be built. The astonishing church, still intact and richly adorned with famous mosaics continuing the tradition that had flourished under Theoderic, was completed and dedicated on May 17, 548, when the empress Theodora lay dying in Constantinople. Anyone who thinks he knows what Theodora and Justinian looked like draws his ideas from the mosaic procession here, which shows them and their retinues at the moment of ritual entrance to a church they never saw. Maximian finished a second new church in Ravenna, San Apollinare in Classe, in 549, after a visit to Constantinople.

Then funding slacked off, and Ravenna settled into its destiny as a provincial capital. No emperor ever set foot there again.

0 notes