#klunk supremacy!

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

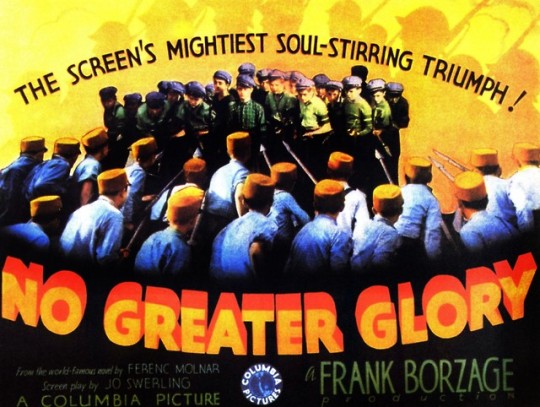

War in Miniature: NO GREATER GLORY (’34) by R. Emmet Sweeney

In April of 1932 the Screen Guild was formed, an ill-fated film production cooperative founded by Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences president M.C. Levee. With backing from Bank of America and initial support from Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and Cecil B. DeMille, it was to provide funding “without restriction and obstructive supervision,” according to Levee in a New York Times article. It only lasted a few years, though they managed to shop two Frank Borzage films to Columbia Pictures: A MAN’S CASTLE (’33) and NO GREATER GLORY (’34), which are currently streaming on FilmStruck. Both were flops at the box office, and the Screen Guild dissolved soon thereafter. Borzage took full advantage of the creative freedoms afforded by the Screen Guild, though A MAN’S CASTLE was hampered by the censors. NO GREATER GLORY, adapted from the popular Hungarian novel by Ferenc Molnár, suffered no such cuts, though its depiction of children embracing militaristic ritual was embraced by pacifists and fascists alike. Borzage would remark years later: “It was an indictment against war…and got a citation from Mussolini!”

Borzage had an admiration for Molnár’s work, having adapted LILIOM in 1930, and sped NO GREATER GLORY into pre-production in September of 1933, two months before A MAN’S CASTLE’s failure might have soured Harry Cohn on funding such a venture. But Jo Swerling put the finishing touches on the script, leaving the difficult job of casting. According to Herve Dumont’s Frank Borzage biography, the film needed fifty teenagers cast, and the director wanted performers with no previous experience. This led to the lead role of tremulous youth Nemecsek going to George Breakston, who had only done uncredited background work on IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT (’34). An unruly set was the result, according to Dumont Harry Cohn came in person to complain about the noise they were causing – he designated Frankie Darro as sheriff in order to maintain order.

Nemecsek is the center of NO GREATER GLORY, the son of a poor tailor who desperately wants to climb the ranks of the Paul Street Boys, a local gang of kids who play at army life in an abandoned lot. Their nemeses are the Red Shirts, a group of older boys led by Feri Ats (Frankie Darro), who are plotting war to snatch the lot. The two groups pull minor pranks on each other – stealing flags and marbles – leading to a full-blown battle for supremacy made up of sand bombs and dirt wrestling. Poor Nemecsek is desperate to prove his worth, running himself ragged until he comes down with a dangerous cold that morphs into pneumonia. Near death, and hallucinating orders from his commanding officer, Nemecsek returns to the field of battle, putting into question what the Paul Street Boys and Red Shirts were fighting about in the first place.

The movie opens with clips from ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (’30), followed by a maimed serviceman yelling how “patriotism is a loathsome lie” (this opening was excised in foreign release). Borzage dissolves to a school teacher lecturing that there is “nothing finer” than fighting for your country. This opening sets up the gap between rhetoric and action, a gap these children will learn about in short order. The Paul Street Gang has been so indoctrinated in military ways, seemingly through osmosis, all they yearn for is to rise up the ranks, defend the gang’s honor and defeat the Red Shirts. Nemecsek is the only private in the Paul Street Gang, so the only one unable to wear a military cap. This tortures the poor child, who finds an intense sense of belonging in the group – which is led by a loudmouthed tyro named Boka (Jimmie Butler, who had trained at Southern California Military Academy). Nemecsek is the youngest and just about the smallest member, but he gains respect by sneaking into the Red Shirt camp and almost stealing their flag back.

But it is during this courageous mission that he is once again dunked in water – the Red Shirt punishment. From that he contracts the virus that slowly saps his body of strength.

The themes are pushed across with such clarity that NO GREATER GLORY can seem didactic at times. And though Borzage’s affection for his tiny tin horn leaders sometimes undermines the allegorical point the film is making about the effects of war, both Boka and Feri Ats are shown to be men of principle, especially in their dealings with Nemecsek, who impresses them with his passionate loyalty as well as his bravery in infiltrating the Red Shirt camp. Breakston was a spindly child, and with his blond mop top and neurasthenic breathing, he seems fragile to the touch. It seems like his old man’s breath could tip him over. Their mutual protectiveness of Nemecsek, and the diplomatic way in which they handled his sickness, could be interpreted in support of the military bearing taken on by these children, an exercise in discipline. This is surely what caused the Fascist Italian jury to give him a prize.

Jean Mitry wrote that in this film Borzage “exalts in order to better stigmatize.” The more these children are writ large, the clearer their flaws. Both the Paul Street Gang and the Red Shirts sacrifice the majority of their free time to their nonsensical battle, over a spit of grubby land that will soon be razed to put in apartment buildings. All that planning and chaos and violence are executed for literally nothing. The kids are re-enacting WWI on their own miniature scale, digging trenches and sustaining losses for “patriotism,” a patriotism for land that is not theirs, and for a group invented just a few months prior. But when Nemecsek tremblingly asks to wear his military cap as the life drains out of his body, you wish he could keep these illusions a little longer. His mother carries him through the town in a procession of beseeching abjection, the kid actors trudging behind her like zombies heading for the grave.

Though a critical success, the public didn’t show up. The film’s eulogy was expertly stated by Frank Capra:

There has not been a finer, more tender or better made motion picture turned out in some time than director Frank Borzage’s No Greater Glory. It has everything the critics of motion pictures could ask for, and what does the public do? It lets a fine picture become a box-office klunk. That’s one reason why the producers don’t gamble on more such fine pictures. When they do, the public fails to support them.

NO GREATER GLORY was the end of the Screen Guild, and as Dumont wrote, “put an end to Borzage’s dreams of independence.”

11 notes

·

View notes