#sapir-whorf but in the opposite direction

Text

Something that I thought would be confusing but just isn't is that Japanese uses the opposite set of direction metaphors for time as English does. So in English, words like "ahead" refer to the future, and "behind" refer to the past. In Japanese it's reversed, 前 (mae) means "in front" and "before", while 後 (ato) means "behind" and "after".

When I first heard about this I thought it would require some kind of difficult retooling of how I visualize time, but turns out it just doesn't. 前 just means "past" to me in a time context and "front" in a space context, mutatis mutandis for 後, and it's no problem. Turns out the spacial metaphor wasn't really load-bearing in my conception of time to begin with.

It's shit like this that makes me doubt the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

276 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have lots of thoughts about how girls and boys in the US (and lots of places, I just didn’t want to overgeneralize) are brought up in totally different social, cognitive, and linguistic silos that we’re raised in from the earliest part of childhood. As soon as we can talk and our words are corrected by the people around us, based upon their perception of our gender, we’re being socialized into a gender silo.

Now, before I go on with this, I want to point out that for all kinds of reasons - unusual upbringing, gender identity/conformity, neurodivergence, being raised in a culture space without strong homosociality norms, etc - it’s possible for someone not to end up in a silo from early early childhood. So there being no one biologically essential experience of girlhood or boyhood, can absolutely co-exist with the existence of social and cognitive silos.

The thing with these silos is that, in my opinion, men and women have more of the same experiences and emotions in common than not. I am not saying - necessarily - that men and women are the same.

What they’re taught is completely different expected social norms around these things, and different ways of dealing with conflict within their groups and with their friendships. Now, if you are my age and you’ve read Deborah Tannen then this seems like a no-brainer. But I don’t think people really think about how far down this rabbit hole goes, or the probable Sapir-Whorf-adjacent implications of the whole thing.

Boys and girls are given completely different messages by children’s programming and by the world around them about how they’re supposed to interact, communicate, and even PERCEIVE THEIR WORLD, and what words they’re supposed to use to describe their emotions.

Depending upon how sealed off their silo is - they may grow up thinking that only *their* gender experiences specific emotions or life experiences. For example, some women thinking all men are inherently predators, because they’ve never known any men except the ones who preyed upon them. Some hetero-attracted cis men thinking ALL women can get any sex they want, and are never lonely, and that the rich, mean hot girls represent the attitudes of all women - because they’ve never known, in their entire life, unrelated girls or women outside of a very specific social context. Women with almost identical types of attitudes thinking that entitled incels are always male. Et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

It always looks like, from within your particular social silo, the opposite sex has actually different emotions and needs as opposed to being socialized to talk about those things differently.

Like... it became really clear to me that “bunny boiler discourse” and “crazy ex girlfriend discourse” in the 80s and 90s was actually a conversation about female-on-male abuse and/or predation, filtered through an 80s average male-normative vocabulary instead of the therapy-influenced language that we’re taught as middle class women is “the right way to describe things” (particularly in a social environment where men are ALWAYS seen as victimizers and never victims). When you actually listened to what these guys were saying instead of getting pissed off at their choice of words, you actually absorbed that there was a legitimate experience being described here that cut across gender lines... guys just didn’t use the same words to talk about it, and were dealing with the social minefields of *their* particular silo in trying to articulate this rotten experience that was happening to them (that happens to all genders), and were just as socially slapped for using the wrong choice of words as women are.

And when middle class girls talked about the same experiences, they were often directed away from blunt, short/succinct “working class” or “male” language and reinforced to express their thoughts/feelings in terms of the “polite” therapeutic or academic language that passes for Obligatory (White) Middle Class Female English in your particular era. Further, they were reinforced by practically all adults and all media that it was their job to police the speech of any boys in their presence. What’s frustrating is that a lot of upper class feminist approaches don’t really acknowledge that Compulsory Middle Class Female English is practically constructed so that women DON’T succinctly describe their experiences and feelings, yet this particular style of feminist discourse tends to present this form of communication as the *only* valid communication and actively problematizes other styles of communication.

A big problem with a lot of approaches to feminism is that they don’t question the existence of this metaphysical silo or even try to leave it. You’re stuck inside Plato’s Cave, thinking that’s the whole universe. You don’t try to dismantle it and in many cases the things you’re doing that you think are “feminist” actually just reinforce this cultural silo.

And I think it may even go deeper than the most popular approaches to Deborah Tannen’s analyses because there’s a whole Sapir-Whorf Adjacent metaphysical worldview/cognitive component to being siloed, it’s not *just* what words you use... but how you’re taught to relate to the world based upon what words you use and how it may even affect your development.

And it’s also the fact that these silos act as social protection rackets that reinforce compulsory gender-conformist behavior.

#this is where The Matrix really nails gender if you think about it#reason the millionth that I'm an egalitarian#my own experience is that I was raised to communicate my boundaries and needs in short/blunt ways and had to learn how to use and speak#in politicized therapeutic language not just to interact with women but increasingly with many men too#the Sapir-Whorf adjacency and the cognitive aspects of these silos is why I feel that yes - correcting someone's language about describing#their own feelings and experiences - is just often just straight gaslighting

370 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Language Shapes Our World

‘The limits of my language means the limits of my world.’

― Ludwig Wittgenstein

There is undeniably a relationship between language use and our experience and perception of the world, but before we can discuss this, there are two concepts that we need to understand: the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, and Cognitive Linguistics.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis was first put forward by Edward Sapir in the early 1900s and later progressed by Benjamin Whorf, and makes the case that the structure of our language must in some way influence the way that we see the world, and so perception is relative to a subjects’ spoken language.

Cognitive linguistics, on the other hand, adopts quite the opposite: the way that we view the world influences the structure of the language and words that we use.

We use language every single day, in a number of different ways, whether this be to communicate information or express emotions, to tell jokes or entertain, to persuade others of a certain belief etc. we continue to use language in our expressions and thoughts. However, many linguists and philosophers (or maybe all linguists are philosophers) believe that language does not only express ideas but it plays a role in shaping the way that we view and understand the world.

There is a lot to look at when we look at language, not least because of how many words there are in a language, the different ways that words are used etc. but how do we go about choosing one language of the six and a half thousand languages that are in existence? I will provide two examples of how metaphors are used and their basis being on the way that the world is perceived, both involving direction.

When we English speakers in the West claim that something is ‘behind us’, we can think of this in the literal sense as being physically behind – that’s to say out of sight at the ‘back’ of us – or we can think of it metaphorically as being in the past and what is before us is what is to come in the future. Both are valid interpretations and understandings.

If we analyse this two-word phrase ‘behind us’, not just in English but cross referencing them to other cultures also, Trask and Mayblin show how they can mean different things in different contexts.

First, let us look at the metaphorical example, that what is ‘behind us’ is the past and what lies ‘before us’ is the future. This understanding depends on our perception of time. It is believed that we English speakers in the West view time as being a thing that remains constant and stands still, while we travel through it. In this way, we are travelling through time, the past has already come and gone, and is now behind us as we walk away from it and towards our future.

For Ancient Greeks however, the subject remains still in time while time overtakes us. Because of the direction they believe time to be travelling (coming from ‘behind’), the ‘past’ is in front of them and thus visible, while the future is behind them and unknown. The root of this lies in different perceptions of time. The use of metaphor here used by ourselves and the Greeks, bound by context, plays a central role in cognitive linguistics.

Now to look at the literal meaning of ‘behind’ or on the ‘back’ of, let us use the example given by Trask and Mayblin, of a cockerel. In English, when we say that the cockerel is on the back of the house, it seems obvious what this means – it means that the cockerel is behind the house, maybe in the garden etc., whatever is the opposite to the front of the house. This makes sense to us. But, in many cultures and languages (which we must distinguish from one another), namely in parts of Africa, to find the cockerel ‘at the back of the house’ means that you will find the cockerel on the roof! How can this be, is the natural question…

We as English speakers in the West orient ourselves as human beings. What this means is that we view our left and right based on our positions and as our backs are behind us, we naturally believe whatever is on the back of something to be behind – the two become almost synonymous. Not all languages work the same, they do not all use the human being as a metaphor for direction as we do. There are speakers in other languages who use four legged animals as their metaphor, such as some African language speakers who use animals such as the buffalo; as the ‘back’ on the buffalo is not behind it, as is the case for people, but on top, ‘the cockerel is on the back of the house’ would mean that it is actually on top of the house.

Although ‘behind’ or ‘on the back’ seemed to be a literal meaning, they too are metaphors that have developed through our perception of the world, which has through time evolved the way we use words and phrases. Different metaphors, as seen, produce different meanings and the cognitive linguist would argue that almost nothing can be expressed without understanding of metaphors, and more importantly the context of the metaphor produced.

136 notes

·

View notes

Text

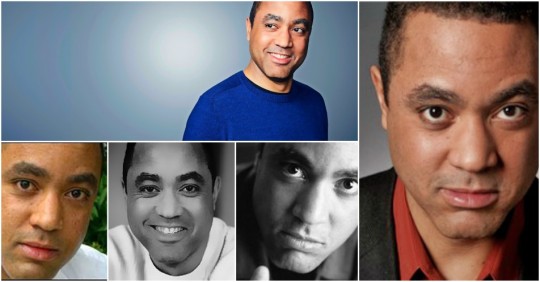

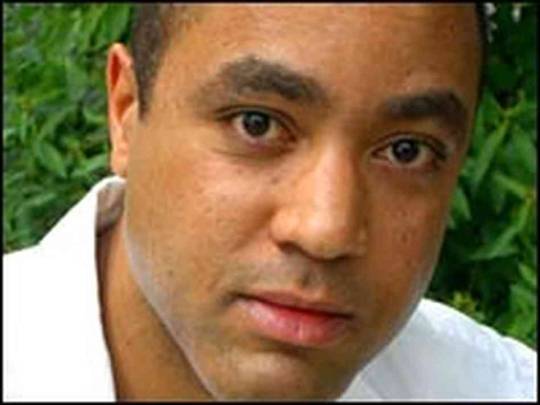

John McWhorter

John Hamilton McWhorter V (born October 6, 1965) is an American academic and linguist who is Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, where he teaches linguistics, English, American studies, comparative literature, philosophy, and music history. He is the author of a number of books on language and on race relations. His research specializes on how creole languages form, and how language grammars change as the result of sociohistorical phenomena.

A popular writer, McWhorter has written for Time, The Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Republic, Politico, Forbes, The Chicago Tribune, The New York Daily News, City Journal, The New Yorker, among others; he also hosts Slate's Lexicon Valley podcast.

Early life

McWhorter was born and raised in Philadelphia. He attended Friends Select School in Philadelphia, and after tenth grade was accepted to Simon's Rock College, where he earned an A.A. degree. Later, he attended Rutgers University and received a B.A. in French in 1985. He received a master's degree in American Studies from New York University and a Ph.D. in linguistics in 1993 from Stanford University.

Career

Since 2008, he has taught linguistics, American Studies, and in the Core Curriculum program at Columbia University and is currently an Associate Professor in the English and Comparative Literature department there. After graduation McWhorter was an associate professor of linguistics at Cornell University from 1993 to 1995 before taking up a position as associate professor of linguistics at the University of California, Berkeley, from 1995 until 2003. He left that position to become a Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank. He was Contributing Editor at The New Republic from 2001 to 2014. From 2006 to 2008 he was a columnist for the New York Sun and he has written columns regularly for The Root, The New York Daily News, The Daily Beast and Time Ideas.

McWhorter has published a number of books on linguistics and on race relations, of which the better known are Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language, Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English, Doing Our Own Thing: The Degradation of Language and Music and Why You Should, Like, Care, and Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America. He makes regular public radio and television appearances on related subjects. He is interviewed frequently on National Public Radio and is a frequent contributor on Bloggingheads.tv. He has appeared twice on Penn & Teller: Bullshit!, once in the profanity episode in his capacity as a linguistics professor, and again in the slavery reparations episode for his political views and knowledge of race relations. He has spoken at TED (2013), has appeared on The Colbert Report and Real Time with Bill Maher, and appeared regularly on MSNBC's Up with Chris Hayes.

McWhorter is the author of the courses entitled "The Story of Human Language, "Understanding Linguistics: The Science of Language," "Myths, Lies and Half-Truths About English Usage," and "Language From A to Z" for The Teaching Company.

Linguistics

Much of McWhorter's academic work has concerned creoles and their relationship to other languages, often focusing on the Surinam creole language Saramaccan. His work has expanded to a general investigation of the effect of second-language acquisition on a language. He argues that languages naturally tend towards complexity and irregularity, and that this tendency is only reversed by adults acquiring the language, of which creole formation is simply an extreme example. As examples, he cites English, Mandarin Chinese, Persian, the modern colloquial varieties of Arabic, Swahili, and Indonesian. He has outlined these ideas in academic format in Language Interrupted and Linguistic Simplicity and Complexity, and for the general public in What Language Is and Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue. Some other linguists suggest that his notions of simplicity and complexity are impressionistic and grounded on comparisons with European languages, and point to exceptions to the correlation he proposes.

McWhorter is a vocal critic of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. In The Language Hoax, he outlines his opposition to the notion that "language channels thought."

McWhorter has also been a proponent of a theory that various languages on the island of Flores underwent transformation due to aggressive migrations from the nearby island of Sulawesi, and has joined scholars who document that English was profoundly influenced by the Celtic languages spoken by peoples encountered by Germanic invaders of Britain (see Brittonicisms in English). He has also written various pieces for the media arguing that colloquial constructions such as the modern uses of "like" and "totally," and nonstandard speech in general, be considered alternative renditions of English rather than degraded ones.

In January of 2017, McWhorter was one of the speakers in the Linguistic Society of America's inaugural Public Lectures on Language series.

Social and political views

McWhorter characterizes himself as "a cranky liberal Democrat". In support of this description, he states that while he "disagree[s] sustainedly with many of the tenets of the Civil Rights orthodoxy," he also "supports Barack Obama, reviles the War on Drugs, supports gay marriage, never voted for George Bush and writes of Black English as coherent speech". McWhorter additionally notes that the conservative Manhattan Institute, for which he worked, "has always been hospitable to Democrats". McWhorter has criticized left-wing and activist educators in particular, such as Paulo Freire and Jonathan Kozol. He believes that affirmative action should be based on class rather than race. One author identifies McWhorter as a radical centrist thinker.

In April 2015, McWhorter appeared on NPR and claimed that the use of the word "thug" was becoming code for "the N-word" or "black people ruining things" when used by whites in reference to criminal activity. He added that recent use by President Obama and Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake (for which she later apologized) could not be interpreted in the same way, given that the black community's use of "thug" may positively connote admiration for black self-direction and survival. McWhorter clarified his views in an article in the Washington Post.

Bibliography

1997: Towards a New Model of Creole Genesis ISBN 0-820-43312-8

1998: Word on the Street: Debunking the Myth of a "Pure" Standard English ISBN 0-738-20446-3

2000: Spreading the Word: Language and Dialect in America ISBN 0-325-00198-7

2000: The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages ISBN 0-520-21999-6

2000: Losing the Race: Self-Sabotage in Black America ISBN 0-684-83669-6

2001: The Power of Babel: A Natural History of Language ISBN 0-06-052085-X

2003: Authentically Black: Essays for the Black Silent Majority ISBN 1-592-40001-9

2003: Doing Our Own Thing: The Degradation of Language and Music and Why We Should, Like, Care ISBN 1-592-40016-7

2005: Defining Creole ISBN 0-195-16669-8

2005: Winning the Race: Beyond the Crisis in Black America ISBN 1-592-40188-0

2007: Language Interrupted: Signs of Non-Native Acquisition in Standard Language Grammars ISBN 0-195-30980-4

2008: All About the Beat: Why Hip-Hop Can't Save Black America ISBN 1-592-40374-3

2008: Our Magnificent Bastard Tongue: The Untold History of English ISBN 1-592-40395-6

2011: Linguistic Simplicity and Complexity: Why Do Languages Undress? ISBN 978-1-934-07837-2

2011: What Language Is: (And What It Isn't and What It Could Be) ISBN 978-1-592-40625-8

2014: The Language Hoax: Why the World Looks the Same in Any Language ISBN 978-0-199-36158-8

2016: Words on the Move: Why English Won't - and Can't - Sit Still (Like, Literally) ISBN 978-1-627-79471-8

2017: Talking Back, Talking Black: Truths about America's Lingua Franca ISBN 978-1-942-65820-7

Wikipedia

3 notes

·

View notes