I will post mainly my thoughts on things I have read and/or seen and review them. I will occasionally post artwork, or save images on this blog as ideas for future projects. I will do a written reflection on something at least once a week and may have related items around the same time too. Enjoy!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

I actually have no followers but this is a PSA to myself of, I promise Im gonna start posting more from now on, settling into university took a little while but I have so many books I still havent spoken about, so get exciteddddd

0 notes

Text

The beauty of The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco

tl;dr philosophical medieval murder mystery in a library. Highest of ratings, 10/10 and beyond. I can’t begin to praise this book enough. This book has been possibly one of the most inspiring, most jaw dropping, most intense and simply one of the most fascinating books I have read. Before creating this tumblr, a little less than a year ago, I read name of the rose, by the incredible novelist Umberto Eco. Umberto Eco has been noted to receive high praise for this work, as it combines a lot of his lifes work and research into a medieval mystery crime based in an Italian Monastery in 1327. This book is incredible for its use of semiotics, biblical analysis, medieval history and literary theory, and does it incredibly well and informatively. Admittedly, the book is rather dense. My copy (same as in picture) is about 650 pages long, and the first 100 pages are excruciatingly difficult to read, partly because the reader is still learning to read the text, immerse themselves, and learn about the context surrounding the novel (not to mention Eco probably wrote the first 100 pages deliberately to be difficult, as to immerse readers with more ease when actual events happen). Luckily, the plot is simple and rather easy to follow, as it follows a stereotypical murder mystery, just branded with a medieval mark. However, this book would not be so highly commendable by me if I read it just for the plot. This is quite possibly my favourite book to stand at the moment, and this is because of its use of religious, literary, artistic and philosophical history and theory. Based in an Italian abbey, through the voice of at-the-time novice monk following one of the most acute friars imaginable, as they are invited to investigate a recent suicide/possible murder. Yet, the incredibly acute friar does not seem very invested, instead admiring surrounding prospects of the monastery and often distracting himself. As such, the novel explores themes of the abbey, and constantly teaches readers about ‘godly architecture’ with vivid and serene imagery, while constantly hinting and foreshadowing areas and people that become important. The characters in this book are both pathetic and admirable, where instead of character development for any particular character, you more so learn about a doctrine or an idea. As I’ve said, this book is not plot oriented, it explores different historical notions that fit very well into contemporary thought. For example, a lower monk named Salvatore is introduced as a foreign, uneasy person, who ‘speaks all languages, but none’. In this book, despite most being translated into whatever text you’re reading in (or the original Italian copy), Salvatore speaks confusingly, and as a reader, frustratingly. Oftentimes, the characters will speak in Latin, and I simply used google translate to try and understand the text (though its difficult to say whether you should, or not, as it is deliberately Latin since the novice monk cannot speak it). However, when Salvatore speaks, one can recognise Latin, French, English, German and Italian words. Hence, the conversations are disjointed, like there is a wall between Salvatore and whoever he is conversing with, pointing at the language barrier formed from speaking so many languages, yet none fluently. Yet as a character, nothing in particular changes about him, this mystique, foreign and confusing nature remains throughout the book, as initially formed during his first appearance. This is one of the books interesting traits, as it is not really coming to a resolve, just observing its surroundings, and so, this is simply a picture of an unusual monk in an Italian abbey. As such, Salvatore, though generally clumsy i text, has a fascinating aspect to his character, disgusting in form, but memorable for his misplacement. This is but one of the many characters, who are each memorable respective to their assets, but in both a curiously fascinated and disappointed or disgusted way. As such, the book’s development of its surroundings becomes memorable in its own right. Essentially, the abbey parallels universities in a very casual manner, with its enormous library and transcription areas. However, Eco phrases this better than I could ever imagine, as every chapter some part of the abbey is newly explored, whether it be an aggregated hall or a small, eerie room in the library... Unfortunately, this book is difficult to admire without spoilers. As such, below there is some more text for those interested including the spoilers. For those who do not want to, but are interested in this book, I highly recommend the read, it is incredibly difficult at times, but it has a lasting mark. FROM HERE ON, THERE ARE SPOILERS. God, can I finally gush??? This book explores lots of ideas, including the antichrist, library structures, power struggles, sex, sin, virtue, art, literature, semiotics, architecture and so much more. However, I would really like to describe this ‘arc’ in the book which motivated me so much to write this review. For those spoiling themselves right now, the reason I decided to write this review was because I was reminded of one of the most GRAPHIC and VILE scenes I have ever read. There is a scene where a woman which the novice monk slept with is accused of witchcraft and is burnt at the stake among a few other monks accused of being the ‘antichrist’ and responsible for the murders. The reason why this woman is so much more notable than so many other scenes of rape, torture, poisoning and incredibly powerful and influential philosophical discussions for me is undoubtedly her lead up and one of the most haunting dialogues. To set the scene: Salvatore, the monk who speaks all but any one language, pays this woman to sleep with her, and is assumed to have done so regularly. Adso, the novice monk, searches for clues in the library one night, when Salvatore hears him and runs. Adso panics, and meets the woman, eventually overcome by adrenaline, where they both commit to sexual intercourse. Appalled by his actions afterwards, he confides in his supervising friar, who admits that his sin may be forgiven for his confession and thought (in itself an interesting dialogue between a father and son-like relationship). However, Salvatore commits to this again, but is caught by another investigator of the recent murders. Unlike William, Adso’s friar, this investigator is strongly motivated by bloodshed (ANOTHER very interesting idea, as the idea of the ‘antichrist’ is later explored in depth). This time, Salvatore pays the woman through a black rooster, but also brings other equipment such as a black cat to try and ‘seduce’ the woman through a curse. Instead, the woman is accused of witchcraft and sentenced to death, and Salvatore is to be tortured until he confesses to a series of crimes he did not commit. Finally, all the monks gather to watch the stake burning. Adso pleas the William to convince the other monks that the woman is not responsible, but William stays silent. Then, as the fire is set, one of the higher monks, Umberto, whispers in Adso’s ear. He begins to try and pity Adso, assuming he had been seduced by the ‘witch’ and said quite possibly one of the most memorable speeches personally, telling Adso about how the woman may appear beautiful, but in reality is ugly. The insides of the woman are ugly, just like all other people, there is no beauty in her, or in any of humankind, and evocatively describes how the fire burns down this ugliness. I do not want to reveal the actual speech as it is quite long, but also because I simply can’t describe it anywhere as well as Umberto had. I couldn’t look at people for a week without feeling sick. And this is only one of many incredible, fantastic and ugly scenes in the book. Please read it for yourselves, there is so much in this book to admire.

#umbertoeco#umberto eco#eco#the name of the rose#burning#spoilers#book reads#book#good book#recommend#murder mystery#crime#philosophy#philosophical books

1 note

·

View note

Text

A good book with a bad ending

I cannot say I am not frustrated by this novella. This is the first book I have read by Suskind, who is best known for his book ‘Perfume,’ and though its existentialist crises and dispassionate attitude to a pathetic man, only attached to his room is certainly comical in its dark way was an entertaining play on the typical pathetic man, I personally cannot be at peace with this ending. ‘The pigeon’ is a timeless book which sets up in a ‘One day in the life of ---’ format, with Parisian bank security guard, Jonathan Noel having an existentialist crisis and panic when a pigeon stands in front of his room. Noel is a caricature in his neuroticism, often worrying himself as he overthinks all events surrounding him, and becomes terrified by the smallest inconveniences: in this instance, a pigeon. Noel’s day progresses, becoming more and more certain that this minor inconvenience is too large for him, and that its existence means he must depart his beloved room forever, so as to never see this horrible bird again. *SPOILERS START HERE* However, leaving his room with this untrustworthy bird agitates him, as it is the only connection which he is still attached to, and upon realizing this, figures his pointless life is not worth living. He later checks into a motel, and claims he will kill himself the following morning after some sleep. Instead, he wakes up in the middle of the night, where the very existence of his life is torn apart, and reveals that this 50 year old man who has wasted 30 years working and sleeping was merely a dream. Then, the now 20 year old Jonathan Noel ventures into Paris, swearing to avoid this fate. *SPOILERS END HERE* I must admit, without looking at the ending, this book is a funny portrait of existentialism in everyday life. The ‘One day in the life of a nobody’ works so well on top of this, as every boring detail is highlighted to show how pathetic Noel’s life is. In particular, the detail of his lack of connections to any living people makes everything around him look alien, and vile. A homeless man representing Noel’s worst nightmare, and a pigeon spreading filth and dirtying his otherwise perfect home. Everything that is offered in the book is described with entire detail, from the description of his home, to Noel’s dinner containing a can of sardines and a glazed pear. His life is incredibly boring, which makes the writing so clever, as everything is described to show how little there really is, and honestly makes you bored of his existence just as he is of his own. As a result, I won’t denounce it, it is still a good book, and very worthwhile just reading some of it. It draws out existentialist angst and apathy through intelligent writing and the perfect narrative of spending one day with this pointless man. However, for those who have read it, or spoiled themselves, what do you think should have happened? Tell me your thoughts!

#pigeon#the pigeon#suskind#novella#good reads#good books#book#book review#existnetialism#existential crisis#existentialist dread

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

We don’t matter and that’s okay.

Milan Kundera’s most recent book, ‘The festival of insignificance’ (2013) is my personal introduction to this highly politicized French-Czech novelist, and has been a very inviting neo-existentialist work that laughs at its own pointlessness. Kundera, being the humorous and sardonic author behind works like ‘The joke,’ ‘Life is elsewhere,’ and ‘Ignorance’ has been boldly exploring themes of exile, identity, history, and appreciation for the less significant life. In consideration of this latest novel, these philosophies are perfectly presented as we go through the story of people’s characters and behaviors in organizing and participating in a cocktail party, seeing a pregnant woman avoiding suicide through the death of someone else, and stories of Stalin’s cheekiness and exploits amongst his Soviet official comrades. Despite the differences between these three stories, they merge splendidly, as they reflect on all the characters and also relate back to the very purpose of the book - the world is so large and clashing, with all its differences, but in the end, no individual really matters. Stalin is a tease who makes the Russian prime minister Kalinin piss himself in front of this horrifying dictator, a mother who never wanted a child escapes their deaths by killing someone else, and this very child grows up to be something she hates: an ‘apologizer.’ However, even in the very difficulty of describing how this book works so well, it is clearly enjoyable and an easy read through its well structured flow. Thus, if one was to consider Kundera’s latest book one reflecting his philosophy, it is easy to see the immense interest in these subjects. The very use of such a conglomeration of elite powers in one decorated bathroom, screaming about Stalin’s lies for killing twenty four partridges with the man himself listening outside is indescribably abstract while at the same time fascinatingly curious for example. Kundera uses these ridiculous figures who control the Soviet Union and yet, they just all seem so pathetic, which perfectly fits into the idea of ‘insignificant’ man, and the colossal, official identity the public sees in contrast to these oblivious, thick headed personalities which the readers see, performing almost deliberately like idiots. In comparison, ideas such as exile and dejection are formed so well in the narrative between one of the main characters Alain and his mother, the woman who originally intended on suicide. Through the example of Alain’s abandoned mother, we experience his self blame, self pity and self shame, projected as if the feelings of his mother watching Alain live. Conversing with his mother does not only inspire feelings of a projected missing figure, or sympathy for Alain, it also importantly underlines the very feeling of exile, or rejection, from someone so important that it becomes rejection and dis-contempt to oneself. As a result, this book explores a philosophy and phenomenon I will be happy to pursue, and will in future definitely return to. Milan Kundera has been an incredibly humorous, somewhat apathetic writer, who has created such figures that show the very meaningless of existence, while still seeing it as something worthwhile... At least, this is how I perceived it.

#kundera#milan kundera#festival of insignificance#books#good reads#Stalin#soviet history#khrushchev#existentialism#neoexistentialist#exile#history

0 notes

Photo

What a wonderful film uwu

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on blue puppy.

A 20 minute Soviet Cartoon about the misfortune a puppy suffers for being blue, this short musical displays charming aesthetics and songs with incredibly caricatured but attractive characters. Directed by Yuri Entin in 1976, I have found this to be a catchy and sweet, heartwarming tale of how a puppy becomes accepted and realizes that his blue colour shouldn’t get in the way of who he is. If one would like to watch this cartoon, here are two links: Unsubbed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-7Syt8haPIM Subbed: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=To2csb4eK-o&t=68s

‘The pale blue, so very pale blue puppy.’ The main character of the story, this poor Charlie Chaplin like puppy is bullied from the beginning of the film for his colour. Portrayed as a frail, but excitable and sweet creature, the puppy is shown to be a good citizen that is simply mistreated for something he cannot control. The entire cartoon is based on his misadventures for the very same reason, and though the cartoon uses the puppy to say ‘bullying is not okay,’ most of the animation is distracted by an entertaining and clever appeal. Likewise, this endearing character is one we can easily sympathize with, and clearly one to pity and be happy for as they eventually are accepted for being blue.

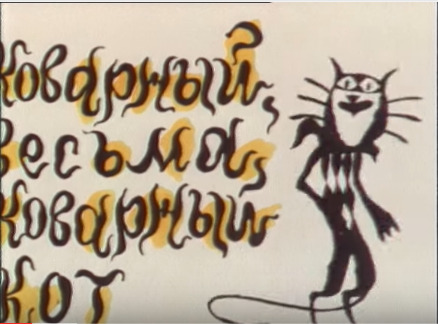

‘The mean, far too mean pirate’ is our clear villain. With one of the catchiest songs in Russian animation, the pirate is delightfully malevolent in his desire to do something bad. His ship is an axe, he transforms into horrible little figures, has a big cannon and an eyepatch, and loves to drink. The dynamic in this character, especially alongside the cruel cat is a clearly strong but fun appearance. One of the joys of this cartoon is that it enjoys showing off its aesthetics, and ‘transformations’ to fit the caricatures. This pirate clearly has no true goal, and so such pirate could ever exist for the sake of it, but it is the way you see him behave that makes this film so fun and interesting. This ‘evil’ pirate is simply an enjoyable example portraying this ‘horrible’ thing.

‘The cruel, clearly cruel cat’ is an incredible antagonist. In the history of Soviet animation, there have been examples of cats having flexible forms, but its incredible to see this one’s form, especially since he’s so inspired from a deck of cards. The cat is voiced by a prominent Russian/Soviet actor Andrei Mironov (Three Men in a boat, The Straw hat, A year like a life) and shows him to be an incredible trickster who plays along with anyone around him, but at heart seems to like the more ‘cruel’ and ‘evil’ sides of things. However, the way he appears is outstanding, with his appearance constantly flowing around, showing his careless will to do whatever. Even if one is not a fan of musicals or such things, watching this cat trickster move and dance is entertaining and seductive in its own right.

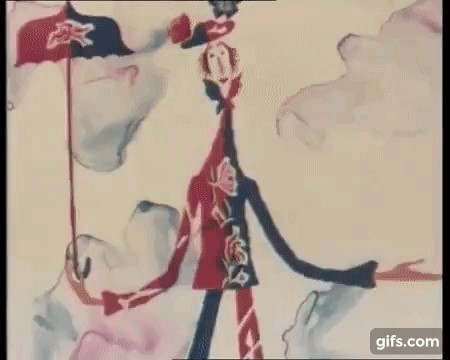

‘The kind, rarely kind sailor’ is a hero appearing for the purpose of being a hero, singing like the oh so evil pirate, but instead of chanting about ‘what horrible thing should I do?’ it becomes ‘what good thing should I do?’ Dancing and singing, this hero accepts all life forms and helps the puppy gain self confidence as he learns that ‘it’s not all that bad being blue.’ Once again, a lovely aspect of this film is that it doesn’t treat its caricatures as propaganda to teach kids how to be, but just plays with the very figures others have created, and this rosey sailor is no different.

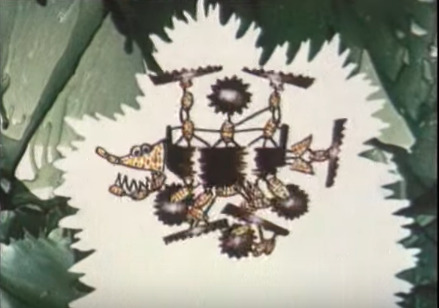

‘The wound up, very wound up saw-fish’ is both a weapon and a character in its own right, chanting about its love and need in sawing things apart. Now this is a real figure in its own right. Appearing only for a few minutes, it has yet another catchy song about sawing apart all the things in the world, wild and thrashing around unpredictably. This active ‘fish’ is a promising one, and has a frightening but surprisingly interesting appeal to it, like the other two villains. In total, these characters add up to have an entertaining dynamic as the puppy tries to return home as an accepted member of the society they live in. This film is easily one to recommend for those who need something cheery and sweet, while having an appeal to everything around it. This piece isn’t serious or dark or trying to explore anything really, just trying to be a mood lifter through the experimentation of Indian ink. Please watch it and tell me what you think of it!

#blue puppy#animation#cartoon#puppy#goluboi#goluboi shenok#soviet cartoon#soviet film#musical#yuri entin

3 notes

·

View notes

Link

Мультфильмы: Голубой щенок Edit Title via http://gifs.com/gif/pg68j2 India ink animation: The blue puppy.

0 notes

Text

Reading list Jan 2017

Read (in order): Thus spoke Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche Uzumaki, Junji Ito Starting Point, Hayao Miyazaki Goodnight Punpun, Inio Asano The pigeon, Patrick Suskind, Art Theory, Cynthia Freeland. Favourites Read in January: 1. Thus spoke Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche 2. Starting Point, Hayao Miyazaki 3. Goodnight Punpun, Inio Asano 4. Uzumaki, Junji Ito 5. Art Theory, Cynthia Freeland 6. The pigeon, Patrick Suskind To be read in Feb (at least 3): Turning Point, Hayao Miyazaki The name of The rose, Umberto Eco Don Quixote, Miguel de Cervantes A brief history of Walt Disney, Brian J. Robb The festival of insignificance, Milan Kundera The wind-up Bird chronicle, Haruki Murakami

1 note

·

View note

Text

Synopsis of Art Theory: A very short introduction

For those seeking an informative book on art theory, or philosophical attachments and relations to art, Freeland poses a good number of theories and philosophers that discuss their ‘theory’ of what art is, reflects, or tries to achieve. Cynthia Freeland uses philosopher from Ancient Greek to today’s society in order to illustrate how many influential thinkers have considered art’s purpose, and presented each with their unique differences. Some of these philosophers include Plato, Kant, Bourdieu, Dewey, and Baudrillard, each of which believed in vastly different thoughts as to what it is and what it should be additionally. As such, the book argues and exemplifies both things that agree with a theory, while soon after showing exceptions as to why it cannot be an all-encompassing idea. Thus, the book excels at both showing many different art forms, while not putting complete attention to individual pieces, as it continues to show diverse forms of art, while comparing them with actual theories. The way these theories are structured into chapters was very flowing and smooth as well. Consisting of only 7 chapters, each explores different aspects of the artistic world in history, while grouping together subjects of the art world together. This provides a non-linear, but very rational approach in explaining theories behind different parts of art. For example, ‘Blood and beauty,’ (chapter 1) provides examples from Renaissance to contemporary art, arguing how art may not be all about beauty as it may be intended to disgust people with political or social commentary. On the other hand, ‘Cultural crossings’ (chapter 3) warns readers about how theories cannot be all encompassing, particularly with other cultures, as one’s personal theory on art may be ‘chauvinistic and ignorant’ in perspective of another culture. Hence, each chapter poses a new approach to the theory of art and provides diverse examples of both philosophy and actual art. As such, upon reading this book, I am glad to have found something that explores philosophy and art together, while not being too focused on one or the other. It also illustrated some very important ideas in the art world: whether it be its purpose, its intent, its cultural meaning and/or significance, or its relations to money, paradigms and cultural and personal understanding. Hence, for those interested in learning about philosophies in art, or a deeper understanding of the subject, I would gladly recommend.

0 notes

Photo

Day 79: Peacock

Be proud of yur yuge tail

Wanna support Bird-A-Day?

Buy Me a Coffee

Visit My StoreEnvy

Preorder “Magpie Soar” Hard Enamel Pin

81 notes

·

View notes

Photo

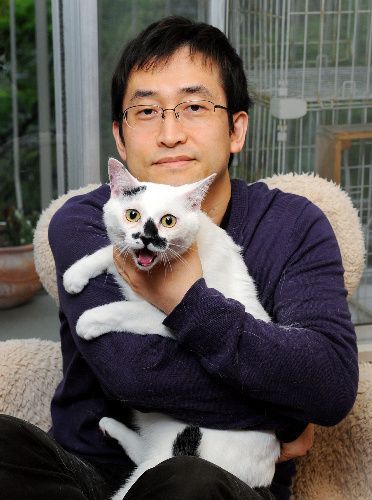

same man who draws horror manga

Portrait of horror manga writer and artist Junji Ito with his cat Tenmaru, Japan, 2013, photographer unknown.

20K notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on Uzumaki: Spiral into horror.

Having read Uzumaki recently I have a few thoughts that I would like to express with others about this frightening book. I have only read Junji Ito’s Uzumaki, but the book has convinced me of his abilities as a Japanese horror manga artist, who has produced notable works like Tomie, Gyo alongside Uzumaki. The book itself has been a captivating read of about 600 pages expressing the despair and helplessness people may face when they are challenged by an unknown force. Throughout the read, there is so much anonymity about the idea of the spiral, and why a concept without sentience plagues the small Japanese town Kurouzu-cho. Though there are some explanations for the spiral’s invasion by the end of the book, it doesn’t ultimately change the feelings evoked by the characters and readers, but rather creates a sense of hopelessness. Rather, the more important part of the book was expressing horror with the obsession and constant appearance of the same thing, with different events only related by a ‘spiral.’ However, I found this also to be problematic in some areas. Out of the 19 chapters, only a few were strongly related to each other and caused more of a build up. Similarly, some chapters had a spiral in it seemingly for forced reasons, especially Mosquitoes and Twisted Souls. It was an upsetting contrast to some of the other chapters that really pulled on the uncertainty and weakness you could feel in some chapters that really focused on the spiral. Thus, the conclusion didn’t seem like it had enough build up, as too many incidents were weakly related to each other, or even weakly related to the fear or obsession with spirals. On the other hand, the weak relation also posed some strength. From the few short stories I have read, and Uzumaki itself, i seems Ito’s horror is so effective because of the uncertainty surrounding it. In the Lovecraft-like way, Ito poses a concept stronger than man, too difficult to comprehend, and thus inspires fear. Why was this really happening? Why did the city emerge like it did? Once again, though there is some explanation, it doesn’t really satisfy the principle all the same, and so there’s a fear in what cannot be explained, as one cannot understand it, and so they cannot handle it adequately either. That’s why it was so important to have a spiral in each chapter. Though a spiral may explain erratic behavior, there’s still no certainty as to why the spiral causes it. Hence, when people try to deter something inspired by spirals like Shuichi’s parents and the emergence of snails it becomes desperate action to try and repel the origin of the spiral’s curse, which makes it all the more frustrating. In total, this is a brief synopsis of my thoughts on Uzumaki. Personally I found the book very captivating as it seemed to show a never-ending cycle of events from which one desperately tries to escape, and so I have found it a very effective piece of horror manga. Your thoughts? Tell me what you thought of it!

0 notes

Text

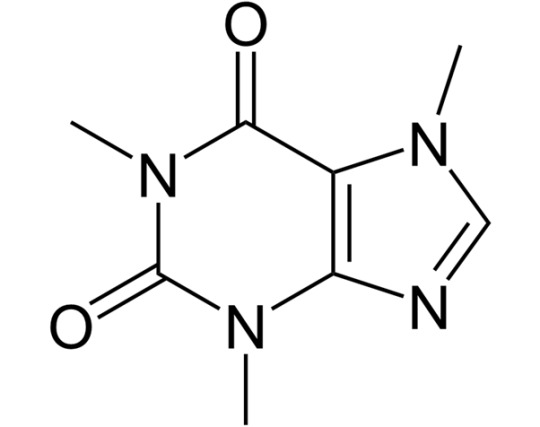

Molecule of the Day: Caffeine

Caffeine (C8H10N4O2) is a white solid that is sparingly soluble in water. It is a naturally occurring alkaloid and is the most commonly consumed drug worldwide. It is consumed for its ability to promote wakefulness and reduce lethargy.

It does so by acting as an antagonist to adenosine receptors in the central nervous system. Since the binding of adenosine to the receptors leads to drowsiness, this inhibition temporarily promotes alertness. Furthermore, it promotes the release of neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine, resulting in its stimulant effects.

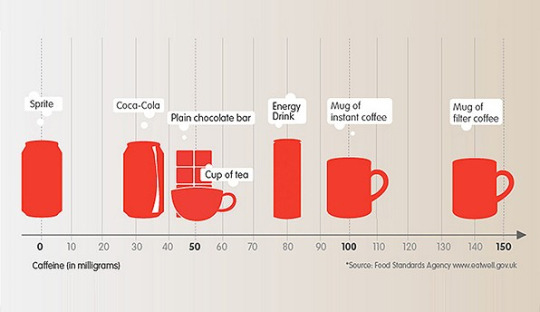

Caffeine can be found in many different beverages:

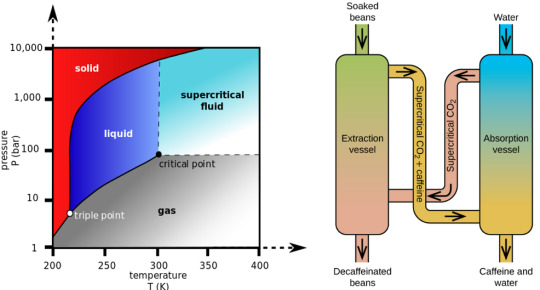

Caffeine is usually extracted from coffee beans using supercritical carbon dioxide. While carbon dioxide normally sublimes and deposits under normal pressures, bypassing the liquid phase, under high pressures, it can exist as a supercritical liquid. Liquid carbon dioxide is a good solvent for caffeine extraction, as it is non-polar and leaves the aroma chemicals intact.

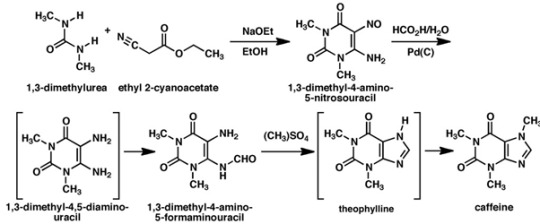

While caffeine is readily available from decaffeination processes, it can still be synthesised from dimethylurea and malonic acid:

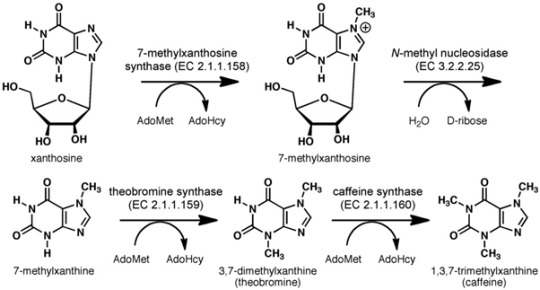

In nature, it is biosynthesised from xanthosine instead:

Caffeine consumption results in a mild form of drug dependence; furthermore, upon regular consumption, tolerance can be built up, resulting in the need for an increasing amount of caffeine to produce the same effects. In small doses, caffeine reduces cardiovascular problems, but it increases its probability in larger doses (over 5 cups of coffee).

1K notes

·

View notes