cw-guzman

299 posts

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

The Importance of The Unlikable Heroine

I’ve always had this tendency to apologize for everything—even things that aren’t my fault, things that actually hurt me or were wrongs against me.

It’s become automatic, a compulsion I am constantly fighting. Even more disturbingly, I’ve discovered in conversations with my female friends that I’m not alone in feeling this impulse to be pleasant, to apologize needlessly, to resist showing anger.

After all, if you’re a woman and you demonstrate anger, you’re a bitch, a harpy, a shrew. You’re told to smile more because you will look prettier; you’re told to calm down even when whatever anger or otherwise “unseemly” emotion you’re experiencing is perfectly justified.

If you don’t, no one will like you, and certainly no one will love you.

I’m not sure when this apologetic tendency of mine emerged. Maybe it began during childhood; maybe the influence of social gender expectations had already begun to affect me on a subconscious level. But if I had to guess, I would assume it emerged later, when I became aware through advertisements, media, and various unquantifiable social pressures of what a girl should be—how to act, how to dress, what to say, what emotions are okay and what emotions are not.

Essentially, I became aware of what I should do, as a girl, to be liked, and of how desperate I should be to achieve that state.

Being liked would be the pinnacle of my personal achievement. I could accomplish things, sure—make good grades, go to a good school, have a stellar career. But would I be liked during all of this? That was the important thing.

It angers me that I still struggle with this. It angers me that even though I’m an intelligent, accomplished adult woman, I still experience automatic pangs of inadequacy and shame when I perceive myself to have somehow disappointed these unfair expectations. I can’t always seem to get my emotions under control, and yet I must—because sometimes those emotions are angry or unpleasant or, God forbid, unattractive, and therefore will inconvenience someone or make someone uncomfortable.

Maybe that’s why, in my fiction—both the stories I read and the stories I write—I’ve always gravitated toward what some might call “unlikable” heroines.

It’s difficult to define “unlikability”; the term itself is nebulous. If you asked ten different people to define unlikability, you would probably receive ten different answers. In fact, I hesitated to write this piece simply because art is not a thing that should be quantified, or shoved into “likable” and “unlikable” components.

But then there are those pangs of mine, that urge to apologize for not being the right kind of woman. Insidious expectations lurk out there for our girls—both real and fictional—to be demure and pleasant, to wilt instead of rally, to smile and apologize and hide their anger so they don’t upset the social construct—even when such anger would be expected, excused, even applauded, in their male counterparts.

So for my purposes here, I’ll define a “likable heroine” as one who is unobjectionable. She doesn’t provoke us or challenge our expectations. She is flawed, but not offensively. She doesn’t make us question whether or not we should like her, or what it says about us that we do.

Let me be clear: There is nothing wrong with these “likable” heroines. I can think of plenty such literary heroines whom I adore:

Fire in Kristin Cashore’s Fire. Karou in Laini Taylor’s Daughter of Smoke and Bone series. Jo March in Little Women. Lizzie Bennet in Pride and Prejudice. The Penderwick sisters in Jeanne Birdsall’s delightful Penderwicks series. Arya (at least, in the early books) in A Song of Ice and Fire. Sarah from A Little Princess. Meg Murry from A Wrinkle in Time. Matilda in Roald Dahl’s classic book of the same name.

These heroines are easy to love and root for. They have our loyalty on the first page, and that never wavers. We expect to like them, for them to be pleasant, and they are. Even their occasional unpleasantness, as in the case of temperamental Jo March, is endearing.

What, then, about the “unlikable” heroines?

These are the “difficult” characters. They demand our love but they won’t make it easy. The unlikable heroine provokes us. She is murky and muddled. We don’t always understand her. She may not flaunt her flaws but she won’t deny them. She experiences moral dilemmas, and most of the time recognizes when she has done something wrong, but in the meantime she will let herself be angry, and it isn’t endearing, cute, or fleeting. It is mighty and it is terrifying. It puts her at odds with her surroundings, and it isn’t always easy for readers to swallow.

She isn’t always courageous. She may not be conventionally strong; her strength may be difficult to see. She doesn’t always stand up for herself, or for what is right. She is not always nice. She is a hellion, a harpy, a bitch, a shrew, a whiner, a crybaby, a coward. She lies even to herself.

In other words, she fails to walk the fine line we have drawn for our heroines, the narrow parameters in which a heroine must exist to achieve that elusive “likability”:

Nice, but not too nice.

Badass, but not too badass, because that’s threatening.

Strong, but ultimately pliable.

(And, I would add, these parameters seldom exist for heroes, who enjoy the limitless freedoms of full personhood, flaws and all, for which they are seldom deemed “unlikable” but rather lauded.)

Who is this “unlikable” heroine?

She is Amy March from Little Women. She is Briony from Ian McEwan’s Atonement. Katsa from Kristin Cashore’s Graceling. Jane Austen’s Emma Woodhouse. Sansa from A Song of Ice and Fire. Mary from The Secret Garden. She is Philip Pullman’s Lyra, and C. S. Lewis’s Susan, and Rowling’s first-year Hermione Granger. She is Katniss Everdeen. She is Scarlett O’Hara.

These characters fascinate me. They are arrogant and violent, reckless and selfish. They are liars and they are resentful and they are brash. They are shallow, not always kind. They may be aggressive, or not aggressive enough; the parameters in which a female character can acceptably display strength are broadening, but still dishearteningly narrow. I admire how the above characters embrace such “unbecoming” traits (traits, I must point out, that would not be noteworthy in a man; they would simply be accepted as part of who he is, no questions asked).

These characters learn from their mistakes, and they grow and change, but at the end of the day, they can look at themselves in the mirror and proclaim, “Here I am. This is me. You may not always like me—I may not always like me—but I will not be someone else because you say I should be. I will not lose myself to your expectations. I will not become someone else just to be liked.”

When I wrote my first novel, The Cavendish Home for Boys and Girls, I knew some readers would have a hard time stomaching the character of Victoria. She is selfish, arrogant, judgmental, rigid, and sometimes cruel. Even at the end of the novel, by which point she has evolved tremendously, she isn’t particularly likable, if we go with the above definition.

I had similar concerns about the heroine of my second novel, The Year of Shadows. Olivia Stellatella is a moody twelve-year-old who isolates herself from her peers at school, from her father, from everything that could hurt her. Her circumstances at the beginning of the novel are inarguably terrible: Her mother abandoned their family several months prior, with no explanation. Her father conducts the city orchestra, which is on the verge of bankruptcy. He neglects his daughter in favor of saving his livelihood. He sells their house and moves them into the symphony hall’s storage rooms, where Olivia sleeps on a cot and lives out of a suitcase. She calls him The Maestro, refusing to call him Dad. She hates him. She blames him for her mother leaving.

Olivia is angry and confused. She is sarcastic, disrespectful, and she tells her father exactly what she thinks of him. She lashes out at everyone, even the people who want to help her. Sometimes her anger blinds her, and she must learn how to recognize that.

I knew Olivia’s anger would be hard for some readers to understand, or that they would understand but still not like her.

This frightened me.

As a new author, the prospect of writing these heroines—these selfish, angry, difficult heroines—was a daunting one. What if no one liked them? What if, by extension, no one liked me?

But I’ve allowed the desire to be liked thwart me too many times. The fact that I nearly let my fear discourage me from telling the stories of these two “unlikable” girls showed me just how important it was to tell their stories.

I know my friends and I aren’t the only women who feel that constant urge to apologize, to demur, to rein in anger and mutate it into something more socially acceptable.

I know there are girls out there who, like me at age twelve—like Olivia, like Victoria—are angry or arrogant or confused, and don’t know how to handle it. They see likable girls everywhere—on the television, in movies, in books—and they accordingly paste on strained smiles and feel ashamed of their unladylike grumpiness and ambition, their unseemly aggression.

I want these girls to read about Victoria and Olivia—and Scarlett, Amy, Lyra, Briony—and realize there is more to being a girl than being liked. There is more to womanhood than smiling and apologizing and hiding those darker emotions.

I want them to sift through the vast sea of likable heroines in their libraries and find more heroines who are not always happy, not always pleasant, not always good. Heroines who make terrible decisions. Heroines who are hungry and ambitious, petty and vengeful, cowardly and callous and selfish and gullible and unabashedly sensual and hateful and cunning. Heroines who don’t always act particularly heroic, and don’t feel the need to, and still accept themselves at the end of the day regardless.

Maybe the more we write about heroines like this, the less susceptible our girl readers will be to the culture of apology that surrounds them.

Maybe they will grow up to be stronger than we are, more confident than we are. Maybe they will grow up in a world brimming with increasingly complex ideas about what it means to be a heroine, a woman, a person.

Maybe they will be “unlikable” and never even think of apologizing for it.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Something about The Rise of Skywalker feels hollow, but not completely hollow. Solo felt hollow, but I couldn’t figure out why. Rogue One didn’t feel hollow.

Part of that is probably a personal factor. Would I have felt differently about Solo at age 12, or would I have forgotten it as not sufficiently transcendent to be worth that portion of my remaining lifespan? I certainly wouldn’t have phrased it that way, but would I have that as some indescribable feeling?

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

Drafting

The Draft Notebook

Be More Productive with Ambient Noise

How to Steal: Know Your Tropes

How to Steal: Good Writers Borrow

Write What You Know (Not What You’ve Experienced)

The Best Way to End a Writing Session

How To Finish a Draft

A Few Tips on Chapters

Language, Description, & Dialog

“To Be” Or Not “To Be”: What Exactly Is Passive Voice?

Tagging Dialog

Narrative Voice

Writing Better Descriptions

Basic Rules for Metaphors and Similes

Character, Plot, & Setting

Creating Characters: a 4-Step Process

Writing Relationships Your Reader Can Get Behind

Informative Character Names

The Strength of a Symmetrical Plot

How to Foreshadow

Crafting Homes of Paper, Ink, and Neutral PH Glue

Motivation

On Writing Flawed Books

How to Return to Your Manuscript

The Acknowledgements Page

Staring at Blank Pages

What to Do When You Can’t Write

Motivational Writing Posters

Publishing

Writing the Perfect Query Letter

How to Write a Synopsis

How to Pitch Your Novel in Under a Minute

A Glossary of Publishing Terms: Vol 1

Writing Tools

Why You Should Give Scrivener a Try

Outlining, Brainstorming, and Researching with Scrivener

Drafting with Scrivener

Editing with Scrivener

CTRL+F

The Forest Productivity App

Editsaurus

NaNoWriMo

Why Try NaNoWriMo

October Prep

Why Listen to Writing Podcasts

Pick a New Daily Word Count Goal

How to Write 2000 Words a Day

How to Plan a Novel without a Story

Pacemaker: Custom Daily Word Count Website

NaNoWriMo Master Post

Other

How to Read an Absurd Number of Books

Writing Workshops: An Introduction

Writing Groups

Different Types of Fantasy Novels

Ambient Soundscapes Based on Famous Writers

Ko-Fi & Other Support

If you enjoy my posts and can afford it, I would greatly appreciate it if you donated to my new ko-fi page! Each of these posts represents multiple hours of unpaid labor. I love writing for this blog, but I’m also an underpaid 20-something trying to stay afloat. I’ve made this master post of every essay I’ve written for this blog as a way to show my appreciation in advance of any support. If you donate, to further show my gratitude and appreciation, I’ll take requests for essay topics in the ‘messages of support.’

If you can’t afford to donate via ko-fi, another great way to show your support is simply by reblogging posts that you find useful and helping my blog reach new writers.

Thanks so much!

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

quick protip: if someone is crying or freaking out over something minor, eg wifi not connecting, can’t find their hat, people talking too loud, do NOT tell them how small or petty the problem is to make it better. they know. they would probably love to calm down. you are doing the furthest possible thing from helping. people don’t have to earn expressions of feelings.

626K notes

·

View notes

Note

"Narrative distance"? Do tell!

Explain it in text? Without emphatic arm gestures or wine? Oh god. Okay. I’ll try.

All right, so narrative distance is all about the proximity between you the reader and the POV character in a story you’re reading. You might sometimes also hear it called “psychic distance.” It puts you right up close to that character or pulls you away, and the narrative distance an author chooses greatly affects how their story turns out, because it can drastically change the focus.

Here’s an illustration of narrative distance from far to close, from John Gardner’s The Art of Fiction (a book I yelled at a lot, because Gardner is a pretentious bastard, but he does say very smart things about craft):

It was winter of the year 1853. A large man stepped out of a doorway.

Henry J. Warburton had never much cared for snowstorms.

Henry hated snowstorms.

God how he hated these damn snowstorms.

Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing and plugging up your miserable soul

It feels a bit like zooming in with a camera, doesn’t it?

I always hate making decisions about narrative distance, because I usually get it wrong on the first try and have to fix it in revision. When I was writing Lost Causes, the first thing I had to do in revision was go through and zoom in a little on the narrative distance, because it felt like it was sitting right on top of Bruce’s prickly skin and it needed to be underneath where the little biting comments and intrusive thoughts lived.

Narrative distance is probably the simplest form of distance in POV, and there is where if I had two glasses of wine in me you would hit a vein of pure yelling. There are SO MANY forms of distance in POV. There’s the distance between the intended reader and the POV character, the distance between the POV character and the narrator (even if it’s 1st person!), the distance between the narrator and the author. There’s emotional distance, intellectual distance, psychological distance, experiential distance. If you look closely at a 3rd person POV story, you can tell things about the narrator as a person (and the narrator is an entity independent of the author) - like, for starters, you can tell if they’re sympathetic to the POV character by how they talk about their actions. Word choice and sentence structure can tell you a narrator’s level of education and where they’re from; you can sometimes even tell a narrator’s gender, class, and other less obvious identifying factors if you look closely enough. To find these details, ask: What does the narrator (or POV character, or author) understand?

I can’t put a name on the narrator of the Harry Potter books, but I can tell you he understands British culture intimately, what it’s like to be a teen boy with a crush, to not have money, to be lonely and abused, and to find and connect with people. There’s a lot he doesn’t understand (he doesn’t pick out little flags of queerness like I do, so he’s probably straight, for example), but he sympathizes with Harry and supports him. I like that narrator. I’m supposed to sympathize with him, and I do.

POV is made up of these little distances - countless small questions of proximity that, when stacked together, decide whether we’re going to root for or against a character, or whether we’ll put down a book 20 pages in, or whether a story will punch you in just the right place at just the right amount to make you bawl your eyes out.

There are so many different possible configurations of distance in this arena that there are literally infinite POVs. Fiction is magical and also intimidating as fuck.

22K notes

·

View notes

Text

Sci-Fantasy and Technomancy

Creating a world where magic and technology co-exist

Mixing science fiction and magic can be tricky; if everyone in the world is capable of teleporting anywhere at anytime, it probably won’t make much sense for people to own cars, for example. Blending these two forces leads to countless exciting possibilities, but it can also end up creating some inconsistencies that your audience will pick up on if you don’t think things through well.

I have several tips and things you should think about if you want to build a world that mixes sci-fi and fantasy. Ultimately how detailed you get with it is up to you; maybe you want to plot out ever single tiny aspect of how your world works, or maybe you just want to have robot dragons and to hell with whoever disagrees! It’s a story of your making; if you and your audience are having fun with it, that’s what I consider most important.

Either way, here’s some things to think about!

- Of course, it helps to start off with the usual integral factors that tend to define societies; things like geography, language, religion, laws, agriculture, philosophy, etc. Before you even start throwing magic/tech into the mix, what does your world look like? What does it sound like? What does it taste like??

- How does magic work in your world? Is it a gift only available to a select few, or can pretty much any Average Joe summon a fireball? Are all mages Clerics (with magic derived from a powerful entity), Wizards (with magic learned from studying), Sorcerers (with magic just as an innate trait), or a mixture of these (and other?) things?

- How does technology (generally) work in your world? How widely available is it? How well is it understood? What level is it at; are there nanobots in everyone’s bloodstreams, or is a bronze sword considered “high technology”?

- How well do magic and technology (generally) mix in your world? Are they both just two different tools for solving problems, or opposed forces? Can one be used to study the other? Can someone be an expert on both things? What problems have been solved (and created) from blending the two?

- Are either things taboo? How much social friction do either things cause? Is the use of one meant to be secret or forbidden? Why?

- Are tech-favoring people/societies generally on equal footing with magic-favoring ones? They don’t have to be! The world being skewed in one side’s favor could be a great source of conflict!

- What can only be done with magic? What can only be done with technology? Consider the limitations of both forces in the world. Does one force typically work better in some or most ways than the other? What things simply can’t be replicated by one side?

- Consider how advanced each side is. What methods of communication, transportation, education, fuel consumption, medical care, etc are available to magic-favoring societies and which ones are available to tech-favoring societies? One side may not be exclusively better than the other; a tech-favoring society might have much faster land transportation in the form of huge cars, but a magic-favoring one might be able to magically tame huge creatures that can walk on walls and reach places tech can’t easily get to.

- (When it can,) how does magic solve the same problems as tech and vice versa? A magical stone of far-speech can fill the magic-equivalent role of a phone, for example. A manufactured chemical packet could function like a certain spell. Of course, if one side’s method is so ubiquitous and accessible, it’s more likely that all people’s will favor it.

- On the other hand, the different perspectives will likely produce entirely different problems and methods of solving them. Beyond one side being unable to replicate certain things from another, they may not want to. Mages may have no interest in creating an internet analogue they instead have access to some great collective unconscious tech-favoring people can’t access. How might one describe these things to the other? This is where the real creative world-building comes in; not every problem should be solved by just having an equally viable magic or tech version of it. Different cultures will value things differently, and exploring that leads to lots of creative worldbuilding and conflict!

- Consider what divisions might exist within societies. There are always subdivisions within groups; not all mages are as powerful, knowledgeable, or experienced as one another. Some subgroups may think themselves superior in some way, and/or might look down upon others within their own circle for all kinds of reasons. No group is a hivemind (unless they literally are); groups are made up individuals!

- Lastly (but possibly most importantly), DON’T GET TOO CAUGHT UP WITH HOW COOL YOUR WORLD IS! Consider exactly what information is relevant to the audience and what interesting ways you can show/explain it. Remember that the focus should generally remain on the characters; there’s nothing wrong with having lots of extra world-building details, but they can bog down the story in minutia if you get too off track! You can always explore and explain deeper lore in side material!

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

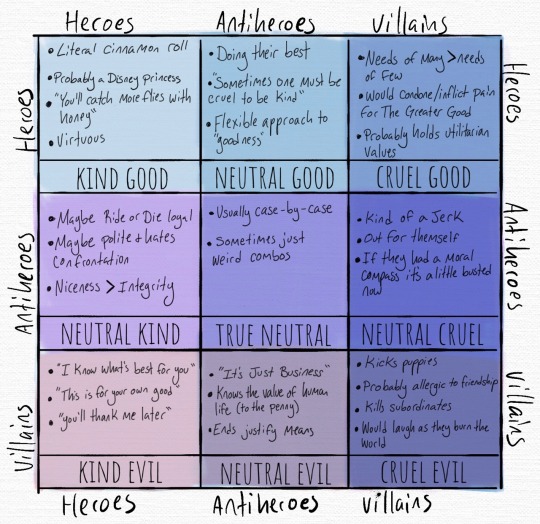

So the other day, I was thinking about the classic alignment chart, and how it doesn’t really do much for me personally since it’s more about how characters interact with systems rather than how they interact with other people

I had a minute, so I figured I’d throw something together that DID suit my needs!

(Note: This chart regards a character’s intent rather than the outcome of their actions—and for sake of clarity, here are the definitions I’m working with:

Good: concerned with the well-being the collective, often at expense of the self

Evil: concerned with the well-being of the self, often at the expense of the collective

Kind: concerned with the emotional responses of others

Cruel: unconcerned with the emotional responses of others)

I like conceptualizing things this way, cause sometimes Bad People behave with ‘good’ or ‘kind’ intentions, and sometimes Good People do things that seem ‘evil’ or ‘cruel’

Also this gives me a way to compare/contrast characters who get lumped together under the other system

40K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fun little thing about medieval medicine.

So there’s this old German remedy for getting rid of boils. A mix of eggshells, egg whites, and sulfur rubbed into the boil while reciting the incantation and saying five Paternosters. And according to my prof’s friend (a doctor), it’s all very sensible. The eggshells abrade the skin so the sulfur can sink in and fry the boil. The egg white forms a flexible protective barrier. The incantation and prayers are important because you need to rub it in for a certain amount of time.

It’s easy to take the magic words as superstition, but they’re important.

146K notes

·

View notes

Text

I saw a post talking about how Terry Pratchett only wrote 400 words a day, how that goal helped him write literally dozens of books before he died. So I reduced my own daily word goal. I went down from 1,000 to 200. With that 800-word wall taken down, I’ve been writing more. “I won’t get on tumblr/watch TV/draw/read until I hit my word goal” used to be something I said as self-restraint. And when I inevitably couldn’t cough up four pages in one sitting, I felt like garbage, and the pleasurable hobbies I had planned on felt like I was cheating myself when I just gave up. Now it’s something I say because I just have to finish this scene, just have to round out this conversation, can’t stop now, because I’m enjoying myself, I’m having an amazing time writing. Something that hasn’t been true of my original works since middle school.

And sometimes I think, “Well, two hundred is technically less than four hundred.” And I have to stop myself, because - I am writing half as much as Terry Pratchett. Terry fucking Pratchett, who not only published regularly up until his death, but published books that were consistently good.

And this has also been an immense help as a writer with ADHD, because I don’t feel bad when I take a break from writing - two hundred words works up quick, after all. If I take a break at 150, I have a whole day to write 50 more words, and I’ve rarely written less than 200 words and not felt the need to keep writing because I need to tie up a loose end anyways.

Yes, sometimes, I do not produce a single thing worth keeping in those two hundred words. But it’s much easier to edit two hundred words of bad writing than it is to edit no writing at all.

126K notes

·

View notes

Text

Creating a Fictional Language Step-by-Step

Writing Advice | My WiP | Twitter

The first step in creating a language for a fictional universe is deciding the feel. How do the words flow? How do they sound? Is it a goblin language that’s spat out in short, rough bursts? A soft, melodious language of elves? Is it ancient or new? Once you’ve figured out how you want your language to feel, you can move onto step 2.

Research other languages. These can be fictional languages or actual languages that are similar to yours. When deciding on my language for my finished novel, I took a lot of inspiration from Hawaiian, Italian and Latin. If you’re not sure where to start, go to Google Translate, dump a sentence into the translator, and filter through a bunch of languages to see which ones you like.

Once you’ve conceptualized and done the research, it’s time to actually start building. Make sure you establish grammar rules. These don’t have to be super complex. Figure out how you’d make something plural, (like English ‘s’ and ‘es’) or what an action verb looks like. (English ‘ing’) If you aren’t sure where to start I recommend looking up English grammar worksheets for kids and basically remaking them to fit your language instead.

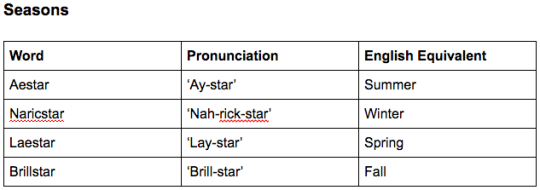

NEXT! Create a separate document where you’ll keep all the new words you create. Keep a guide, not a dictionary. What I mean by that is instead of just listing words and describing what they mean, keep words in categories like “Times of Day”, “Numbers” and “Greeting, Goodbyes, and Responses”. Chart them out so you have the word in your language, the pronunciation and the English equivalent.

The fifth step is developing common phrases. For example, if you figure out how to say “A good morning to you” in your language, then you’ve figured out five full words and you’ve constructed a useful sentence for future use all at the same time. You don’t need 300 pages of words, just enough to fake like you might have actually done that much work!

Lastly, think about dialect, accents and slang. If this isn’t an ancient ceremonial language and it’s something your characters use in their day-to-day lives then there’s a good chance that they’re using short forms of words, contractions and slang terms. Additionally, if two characters speak the same language but come from different parts of the world, their versions of the language will probably differ. These things might not even be evident to the reader but they should be to you.

And that’s it, really. I could honestly write a whole other post on how to USE a fictional language in a story. So if you guys are interested in the formatting and general use then let me know. Oh, and I also recommend @worldanvil to help build your language. I didn’t know it existed when I wrote up mine or I totally would have used it.

I did write that post about using your language in your story so check that out by clicking HERE!

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

How to Use Fictional Languages in Your Story

Writing Advice | My WiP | Twitter

My last post about creating your own fictional language got some pretty positive feedback so I went to work on this one as soon as I could! And BOY is it a LONG ONE! Thanks to everyone who read the last one and wanted more! <3

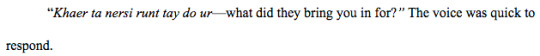

So first: Formatting. I recommend using italics any time you include non-English words in an otherwise English piece of work. That goes for fictional and real languages. You’ll see some examples a little further down.

I’d also like to remind everyone reading this that nobody else knows your fictional language so your job is to teach your readers how to understand and accept it as part of the world. How do you do that? Repetition, restraint, not-awkward translations, and seamless integration.

Repetition: Use the same few words or sentences over and over in your books where they feel natural so readers will start to remember what they mean.

Restraint: You can definitely have too much of a good thing. I don’t recommend having a full dialogue between characters be carried out in a fictional language or an entire paragraph. Use your language sparingly. Too much information too quickly can be overwhelming for a reader.

Translations and Integration: When using a fictional language in a story there’s a lot of ways you can approach translating and integrating it. It’s easier to just show you how I usually do it so here goes:

Option 1

With this option, we have the full sentence in Wey (the name of my language) in italics. Cadence, not knowing Wey, tells the voice she doesn’t understand and so it’s forced to say it again in English.

Option 2

This is probably the most obvious way to throw in a translation. It’s right in the same line of dialogue. The only issue with this is that it can come off a little stilted. There aren’t a lot of instances in real-world speech where people would speak in one language and then repeat themselves in another immediately afterwards without prompting.

Option 3

***This option should only ever be used when all the other characters in the scene speak the same language and can understand what they’re saying.*** This gives you an out so you don’t have to actually write out a full sentence in your fictional language but it tells the readers that the character speaking is doing so in something other than English.

Option 4

This is the other way to go about the whole “using your fictional language but not really” route. If the other characters in the scene don’t understand the language you can express the language like the above example. I also recommend using descriptors for how they’re speaking to better convey the message. Even if a character doesn’t understand the words, they would probably be able to tell that they’re being said with anger, joy, or fear.

There’s also ways to throw in some fictional words in otherwise English sentences, like if you’re insulting someone or greeting them. You don’t have to provide a proper translation if it’s obvious in context.

Aaaaaand that’s all I’ve got for you, folks! Well, I could probably write about this all day but I think I should probably end it here because this post is just way too long as it is. If anyone else has any other tips, feel free to let me know!

@dawen-nightmaiden because you specifically asked me about this post! Hope it lives up to expectation!

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

You know what fantasy writing needs? Working class wizards.

A crew of enchanters maintaining the perpetual flames that run the turbines that generate electricity, covered in ash and grime and stinking of hot chilies and rare mushrooms used for the enchantments

A wizard specializing in construction, casting feather fall on every worker, and enchanting every hammer to drive nails in straight, animating the living clay that makes up the core of the crane

An elderly wizard and her apprentice who transmute fragile broken objects. From furniture, to rotten wood beams, to delicate jewelry

A battle magician, trained with only a few rudimentary spells to solve a shortage of trained wizards on the front who uses his healing spells to help folks around town

Wizarding shops where cheery little mages enchant wooden blocks to be hammered into the sides of homes. Hammer this into the attic and it will scare off termites, toss this in the fire and clean your chimney, throw this in the air and all dust in the room gets sucked up

Wizard loggers who transmute cut trees into solid, square beams, reducing waste, and casting spells to speed up regrowth. The forest, they know, will not be too harsh on them if the lost tree’s children may grow in its place

Wizard farmers who grow their crops in arcane sigils to increase yield, or produce healthier fruit

Factory wizards who control a dozen little constructs that keep machines cleaned and operational, who cast armor to protect the hands of workers, and who, when the factory strikes for better wages, freeze the machines in place to ensure their bosses can’t bring anyone new in.

Anyway, think about it.

57K notes

·

View notes

Text

“so I believe in a universe that doesn't care and people who do”

37K notes

·

View notes

Link

Earlier today, I served as the “young woman’s voice” in a panel of local experts at a Girl Scouts speaking event. One question for the panel was something to the effect of, “Should parents read their daughter’s texts or monitor her online activity for bad language and inappropriate content?”

I…

484K notes

·

View notes

Text

My counselor once told me to make sure I wasn’t doing things to distract myself from the boredom rather than try to sate it. I feel its one of the most important things he ever said to me.

When I’m distracting myself from the boredom, I read or game excessively so I don’t feel the emptiness of boredom. It’s a short term thing, and it only staves the boredom as long as I’m doing the thing.

When I’m sating myself from the boredom, I pursue things I am genuinely interested in and so find myself feeling fulfilled and happier for a longer period of time. Even if I stop doing it temporarily, I don’t immediately fall apart as I would with the distraction.

24K notes

·

View notes

Text

I hope Stephen Hawking’s anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist politics aren’t erased from history, or obscured in our collective remembrance of him.

101K notes

·

View notes