Text

Strange Tales #147 (O’Neil/Everett, Aug 1966). Bill Everett takes over from Ditko. I love that Strange just wanders into a drugstore to pick up over-the-counter meds. Moving a mystic into a mundane space!

#marvel#marvel 616#strange tales#stephen strange#doctor strange#clea#baron mordo#the ancient one#dennis o'neil#bill everett

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Star Trek Disco 1x01 “The Vulcan Hello”

“You can’t set a course without a star.”

Just before this episode debuted on CBS in September 2017, Oprah was interviewing Trump supporters. They were pleased with his performance in office so far. It was like glimpsing into an alternate reality. I wondered, “How can we co-exist in a world with people whose perspectives are so irreconcilable with ours?” Seconds later, the Klingon messiah invaded our screens and snarled in an alien language, “THEY ARE COMING.”

And it was like, oh right! Questions like this are what Star Trek is for.

Even if you don’t watch Star Trek, you’ve probably heard of Klingons. And if you do watch, you’ve gotten comfortable with Klingons: they’re our allies, our friends. But with new make-up designs and costumes, the Klingons of Star Trek: Discovery seem frightening and unfamiliar.

T’Kuvma insists that the Federation’s promise of peace conceals an insidious agenda to eradicate their traditions. Like those Trump supporters, the Klingons now pose not just a political, but an existential challenge: How do we co-exist with what we fear?

“You do understand that being afraid of everything means you learn nothing?”

It’s a big question, and Star Trek uses a TV series, rather than a film, to explore the answer. With a series of movies, you only get two hours every few years. But a TV series affords you more time: more hours and more frequency, which means more opportunities to examine the nuances of a theme or a relationship.

Discovery has a peculiar relationship with time. Before the show debuted, I was thrilled that Star Trek was returning to TV... but cautious about the time period in which it was set. The producers claimed that “10 years before Kirk” was a window where they wouldn’t violate any pre-existing continuity. But they could have simply set Discovery in the 32nd century, after Daniels’ Temporal Cold War, and defined their own mythology.

“Be careful that your assumptions are not being driven by your past.”

Star Trek exists to comment on our world, but lately it has been fixated on its own origins, commenting on itself and reliving its past. At first glance, Discovery seems to fall into the same nostalgia trap. It is simultaneously a prequel, a sequel, a spinoff, and a reboot. I think it probably can be enjoyed as its own story, but it’s constantly aware of its legacy and legends. Each episode remixes or deconstructs familiar images or concepts from previous versions of Star Trek.

The opening credits diagram recognizable parts of Trek lore: ships, phasers, encounter suits, even gestures like the Vulcan salute. As they unravel into the constituent parts (“atom by atom,” as T’Kuvma might say) and co-mingle with other shapes, we see how these big, disparate objects are united by tiny things they share in common.

“I call it a mirror, for I see myself in you.”

That’s how Discovery distinguishes itself from Enterprise and the Kelvin movies. It brings a microscope to the things we take for granted about Star Trek, it considers their purpose and their function, and proposes new ways to use them. By breaking these things down, we can discover what they really mean and how to use them. That’s semiotics in action.

Semiotics is the study of signs and what those signs mean or signify. I love this show, ‘cause Discovery uses semiotics to deconstruct Star Trek, reinterpret its meaning, and launch it beyond its origins. It discovers new content in familiar objects, relationships, and characters. The act of redesigning the Klingons’ appearance, for instance, enables us to reconsider and modernize their history, their faith, their values and their fears. And in doing that work, we discover ourselves in what seemed unfathomably alien.

“Let’s go for a walk.”

Much of the semiotic work in “The Vulcan Hello” is based on “Journey to Babel,” a classic Star Trek episode where we meet Spock’s emotionally distant father Sarek. They haven’t spoken in years, apparently because they disagreed over Spock’s illogical choice to join Starfleet Academy instead of the Vulcan Science Academy. In Discovery, we learn that Spock had a foster sister, Michael Burnham.

It may seem strange that Spock and his family never mentioned Michael Burnham before. Yet “Journey to Babel” shows us that Vulcans rarely discuss family matters, even with each other. So the question here isn’t whether Spock could possibly have a foster sister, but rather what emotional complications compelled Spock and Sarek to never mention her? And what do we learn about Sarek (and, by extension, Spock) through this never-before-seen relationship?

“This isn’t about what happened, Sarek. It’s what’s happening now.”

For a post about Discovery, I haven’t spent much time talking about its characters, plot, or aesthetic choices. Next week I plan to talk more about Burnham herself; the staggering trust between her and Captain Georgiou; their condescension toward anxious Saru; and the holocommunicator technology that seems too advanced for the period in which Discovery is set... But for now, it feels proper to define where Discovery is situated within Star Trek.

Roddenberry envisioned a future where humankind had evolved past our flaws. In the 24th century, there will be no internal conflict and we will work together, regardless of our differences. It’s a lovely goal. But when you enshrine a goal for too long, it becomes sacrosanct. Any deviation or misstep incites the ire of its most devout believers. There must be room for error, consideration, and atonement... even if that leniency seems to threaten the values of the goal.

“Your human tongue is not the problem. It is your human heart.”

The final frontier was never outer space. The final frontier is, was, and always has been the space between people. Star Trek, at its best, exhorts us to be bold, to make mistakes, and -- most importantly -- to own those mistakes and learn from them. That’s how we achieve Roddenberry’s utopia. It’s a process, a journey... a trek, if you will.

A special presentation of Star Trek: Discovery season 1 is currently airing in the U.S. on CBS, Thursdays at 10/9. These posts go live the following Monday.

#Star Trek#Star Trek Discovery#Star Trek DSC#Star Trek Disco#The Vulcan Hello#Michael Burnham#Philippa Georgiou#Saru#Sarek#Utopia#gene roddenberry#Klingon

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

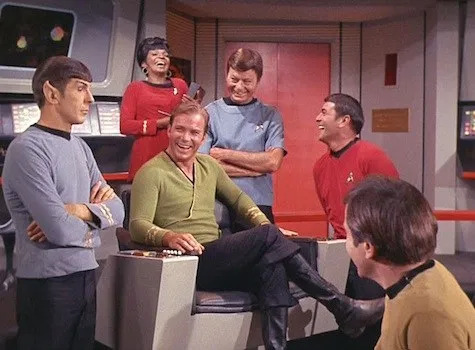

Star Trek Disco Prologue

CBS will air Season 1 of Star Trek: Discovery starting this Thursday at 10/9c.

Before the season begins, a Tribble Triple Feature! Each of these episodes are available on Netflix, Hulu, or CBS All Access. Probably Amazon too, but I didn’t check ‘cause truly is there anything less utopian than Amazon?

TOS 2x15 “The Trouble with Tribbles” TAS 1x05 “More Tribbles, More Troubles” DS9 5x06 “Trials and Tribble-ations”

Star Trek launched in September 1966. Writer Gene Roddenberry had pitched the series as a western set in outer space. But he also wanted to comment upon current events, like war and sex and religion, without attracting the ire of network censors. Season 2′s “The Trouble with Tribbles” lays out a lot of the core ideals of Star Trek that carry over the decades.

The characters hail from different backgrounds, collaborating to solve big problems — in this case, an ecological crisis. Despite their varied perspectives, they share camaraderie, respect, and a surprising amount of snark. They’re also very competent, but that doesn’t prevent disasters from happening, or the crew from simply making mistakes. This isn’t a show about space. This is a show about people who work in space.

And the people out there aren’t all friendly. We meet some adversarial aliens, namely the Klingons. We’re told they’re ferocious, brutal warriors — but Koloth actually seems quite cordial and crafty, less like a warrior and more like a spy. Rather than wage open war, they genetically modify one of their own to appear human. Which is pretty silly, ‘cause the budget constraints of the ’60s mean that Klingons already look human! These aliens seem remarkably familiar and accessible. The far more frustrating adversaries are self-important administrators like Nils Barris, or destructive capitalists like Cyrano Jones.

Star Trek features flawed heroes, frustrating villains... and a lot of moralizing. Uhura advocates on behalf of the tribbles, saying they’re “the only love money can buy.” Kirk retorts, “Too much of anything, even love, isn’t necessarily a good thing.” The bold colors and witty quips can make the morals feel reductive, even cartoonish. But for me, that’s kind of the point. Star Trek presents ethics and philosophy in a simple, accessible way. I won’t claim they’re right 100% of the time, and some of its attitudes shift over the decades — but even this early on, Star Trek stands for harmony, cooperation, and inclusion. And those are perspectives that should be cartoonishly simple.

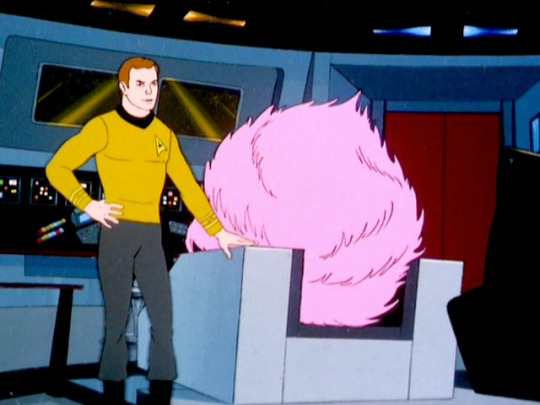

Speaking of cartoons, I took a swing with “More Tribbles, More Troubles.” I’m curious how people feel about the pacing and the primitive animation. This is one of the funnier and more action-packed episodes of The Animated Series. If folks tell me they struggled with it, I’ll cut the remaining handful of cartoons from the schedule.

I’m tickled that they bring Cyrano Jones and Koloth back; and that writer David Gerrold returns, building upon the tribbles’ previous ecological threat by introducing an ineffective predator, the glommer. I also just really enjoy the gag of Kirk repeatedly shoving an ever-growing tribble out of his chair.

Once again, the Klingons are up to crafty business, slowing down the Enterprise with an immobilizing ray and targeting some drone ships. We see more space combat than we did in live action, but it’s still more strategic than open warfare. And again, I suspect it’s a budget issue — the recycled shots of photon torpedoes suggest more action would’ve been too expensive. The result is that the Klingons just don’t seem that ferocious yet. Ultimately Koloth doesn’t even want to punish Cyrano Jones, he just wants his useless science experiment back.

So let’s see how the Klingons change over the decades! Thirty years after the original series, Deep Space Nine uses time travel to explore Star Trek’s history. “Trials and Tribble-ations” was a 30th anniversary celebration for Star Trek, utilizing the same technology that inserted Tom Hanks into historical footage for Forrest Gump.

Integrating two versions of Star Trek across time poses some aesthetic and continuity challenges.

The Klingons of ’90s Star Trek have a much more elaborate make-up design — forehead ridges, wigs, sharpened teeth, etc. They also act more ferocious than the old Klingons. So when 24th-century Klingon Worf shares the screen with the budget-constrained 23rd-century Klingons, fan culture almost demands an explanation. This anniversary episode obliges with a throwaway joke: “It is a long story, and we do not discuss it with outsiders.”

Not every aspect of style needs an onscreen explanation. “Trials and Tribble-ations” was lucky that its visual style adapted so well to the classic series. TOS (The Original Series) and DS9 both used a square 1:33:1 aspect ratio, ’cause that was the shape of everyone’s TV. The DS9 production crew built retro sets, mimicked the same lighting, and were able to insert their actors into the original shots.

This technique is no longer possible, because the technology we use to make TV has changed so much. Even the shape of the frame is different -- we’ve all got widescreen TVs now. If 21st century Trek wants to revisit its past, it must fundamentally re-conceive how those spaces are constructed, lit, and framed.

In 1996, Star Trek was free to engage with nostalgia, caressing its old tricorders and uniforms, admiring it old performances and sets, even reliving the same story points. There’s a certain degree of pleasure and comfort to this, but it makes me a little nervous.

Roddenberry intended for Star Trek to comment upon the world we live in. While “The Trouble with Tribbles” is a comedy about ecological dangers, “Trials and Tribble-ations” is simply a comedy about old Star Trek. It’s a much more limited perspective. And it’s a limited perspective that’s broadly affected pop culture for the past twenty years.

Since 2000, we’ve seen a huge rise in reboots and origin stories. (eg. Batman Begins, Casino Royale, Battlestar Galactica, Man of Steel, etc.) We usually hear that studios only trust audiences to pay for something familiar. I’d like to frame it more charitably and say, in the wake of 9/11, we’re collectively reviewing the stories that defined our culture and deciding which values and lessons are still relevant to us. Star Trek did this too.

In 2001, we got the prequel series Enterprise. 100 years before Kirk and Spock, it follows a pioneer crew on an experimental ship called Enterprise. Season 2 invokes 9/11 when an alien attack destroys Florida, and the grieving crew embark on a mission of vengeance. It was a way to comment on the invasion of Afghanistan. By season 4, the current events commentary was replaced by stories to revisit Star Trek’s lore, including a two-parter to explain Worf’s throwaway joke in “Trials and Tribble-ations” about Klingon appearances.

After Enterprise ended, we got the J.J. Abrams reboot movies, which tell an alternate origin story for Kirk and his classic crew. In the 2009 movie, an alien attack destroys the planet Vulcan, and a grieving Spock seeks vengeance. He’s still grieving in Into Darkness, but gets distracted by a character from Star Trek’s past...

If all Star Trek can do is comment upon itself, it’s no longer serving its purpose. Star Trek must be aware of the cultural, economic, and political challenges we face, and it needs to offer a vision for how we could overcome them.

We’re about to begin Star Trek: Discovery, a show drenched with contemporary awareness and semiotic significance. It takes place 90 years after Enterprise, 10 years before Kirk, and therefore has a peculiar relationship with time — both within its story, and within our world beyond the show. Discovery is Star Trek finally breaking free of its origins and serving the purpose Trek should: envisioning a way forward into a utopian future where there’s space and freedom for us all.

#star trek#star trek discovery#star trek disco#star trek dsc#tos#ds9#tribbles#the trouble with tribbles#more tribbles more troubles#trials and tribble-ations#kirk#spock#mccoy#uhura#sisko#jadzia#cyrano jones#klingon#time travel#roddenberry#mycelial mondays

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s me, I’m back, and there are new Star Treks. The world is on fire, the future is in greater peril than ever before -- am I going to rewatch all of Star Trek again? WHO CAN SAY

Star Trek

Read All Trek Posts Read All TOS Posts Read All TNG Posts Read All DS9 Posts Read All VOY Posts Read All ENT Posts Read All Abramsverse Posts

Read More

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who 1x07 “The Long Game”

In “The End of the World,” The Doctor disarms the Adherents of the Repeated Meme by reducing them to merely “an idea.” (Well, and by yanking some wires.) But ideas aren’t just ideas in this show. Like the London Eye in “Rose,” everything conceals secrets -- iconic landmarks conceal fortresses, political officials conceal aliens, and innocuous phrases conceal sinister purposes.

Here, the innocuous phrase is, “The walls are made of gold.” The employees of Satellite Five slave away to broadcast news to the Fourth Great and Bountiful Human Empire, but they’re so enthralled with the possibility of reward (ie. promotion) that they never question anything. Why is it so hot in the station? Why are there no aliens aboard? Why does no one return from Floor 500, where the walls are made of gold?

In Russell T Davies’ Doctor Who, the biggest enemy isn’t the Slitheen or the Gelth or the Mighty Jagrafess of the Holy Hadrojassic Maxaraddenfoe. It’s complicity. By exposing the secrets embedded in our institutions, The Doctor exhorts ordinary people to shirk complicity and change the universe into a more tolerant and thoughtful place.

#Doctor Who#BBC#Christopher Eccleston#Rose Tyler#Billie Piper#Russell T Davies#The Long Game#The Editor#Simon Pegg#The Mighty Jagrafess#Satellite Five#dwre

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who 1x04 “Aliens of London”

Under Russell T Davies’ supervision, Doctor Who demonstrates conspicuous diversity. I really started to notice it with this episode. As the acting Prime Minister arrives at 10 Downing Street, he’s greeted by an Indian aide named Indra Ganesh.

If the script called attention to Indra’s race, it would feel like it was fetishizing “Other”-ness. But it doesn’t. Instead, it’s a quiet extension of Russell T Davies’ agenda to advocate tolerance and compassion for everyone. After all, the universe is populated by people of all creeds and colors...

And Indra is a significant character. We don’t learn what makes him tick -- what Rust Cohle would call “his hunger and his haunt” -- but he makes a strong impression. He’s young, competent, and polite during a crisis. And although he’s murdered by the end of this episode, his death affects The Doctor and Harriet Jones in the following episode. Writing and casting an Indian for this part isn’t just an empty diversity hire; it’s a statement of intent. In Doctor Who, everyone is from somewhere, and everyone matters.\

Once you notice the conspicuous diversity in this particular episode, you start seeing it structured into the overall series. Rose and Mickey have an interracial relationship. Naoko Mori makes her first appearance as Toshiko Sato, before returning on Torchwood. And Harriet Jones is a diverse character, too -- if this story had been produced in the 1970s, that character would undoubtedly have been Harry Jones.

None of these characters are defined by their demographics; their demographics are simply part of who they are. And what’s really important about them is that they are, they exist and can therefore affect the course of history.

That’s a precious worldview. I’m surprised by how refreshing and revolutionary it still feels, ten years later.

#Doctor Who#Aliens of London#BBC#Rose Tyler#Billie Piper#Jackie Tyler#Camille Coduri#Mickey Smith#Noel Clarke#Christopher Eccleston#Diversity#Russell T Davies#Slitheen#Story arc#Structure

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Doctor Who 1x03 “The Unquiet Dead”

This is the first episode of the revived Doctor Who credited to a writer other than show runner/head writer Russell T Davies. But that credit, to Mark Gatiss, is apparently disingenuous. According to The Writer’s Tale, a wonderful book about writing and TV production and living with a creative mindset, Davies confesses that he rewrites many (most? all?) of the scripts during his head writer.

“Back in 2004, we’d always talked about my rewriting as a possibility (‘polishing’ we called it, when we were young and naive, before we actually had scripts in our hands, and I’d never rewritten anyone before, ever), but [casting director] Andy Pryor kick-started the whole process when we wanted to offer the part of Charles Dickens to Simon Callow. We really needed Simon Callow for that part -- but Mark’s script for ‘The Unquiet Dead’ wasn’t ready.

“After that, in some ways, it became a trap. I’d be rewriting an episode and I’d be thinking, well, if I didn’t get a credit for the last script I rewrote, why should I single this one out? And I have to be fair to the original writers: they work so hard and deserve that credit. It’s partly arrogance as well, because I don’t think my rewrites are as good as my actual scripts. [...] Instead of all those months of thinking and consideration, rewriting somebody else’s script is more like plate-spinning -- keeping lots of things in the air, making them look pretty, hoping that they won’t crash. In an emergency, I throw lots of things in there [...] and hope that I can make a story out of them as I go along, like an improvisation game."

- Doctor Who: The Writer’s Tale, by Russell T Davies and Benjamin Cook. (1st ed, p. 201)

This issue of authorship becomes important with this episode, because “The Unquiet Dead” has a more controversial reputation than its predecessors. Whose voice is on display here, and what were they trying to say?

First and foremost, I think the goal of Doctor Who -- and particularly, Russell T Davies’ Doctor Who -- is edutainment. Teaching the audience was actually built into the original premise of the show, back in 1963. The Doctor’s first companions were a science teacher (Ian) and a history teacher (Barbara). So, on Rose’s first jaunt to the past, we learn about Victorian England -- or, rather, Wales -- and Charles Dickens.

“The Unquiet Dead” pits Dickens against gaseous ghost aliens, embedding some true trivia in a spooky Victorian ghost story. In the episode, Dickens begins as a lonely and weary man. He has resigned himself to never writing again, and admits to being “rather, let’s say, clumsy” with his family. (This references an alleged affair between the real Dickens and Ellen Ternen.) But his adventure with The Doctor and Rose reinvigorates him -- he resolves to return to his family, and begin writing supernatural fiction, like The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Historically, Dickens died in 1870 while working on Drood.

Some parents were upset about the ghost story aspect. They complained to the BBC that the episode was too scary for their children. (This episode does engage more directly with the horror genre than the previous two. The pre-titles sequence ends with a possessed corpse walking up to the camera and letting loose an unearthly howl.) The BBC basically dismissed this, because the terror is carefully balanced with The Doctor’s heroism and humor.

And the humor is just as educational as the horror. At one point, The Doctor realizes he’s in the presence of Charles Dickens, and goes full-on fanboy:

DOCTOR: Charles Dickens, you’re brilliant, you are! Completely 100% brilliant. I’ve read them all! Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, and what’s the other one? The one with the ghost.

DICKENS: A Christmas Carol?

DOCTOR: No, no, no! The one with the trains. ‘The Signal-Man,’ that’s it! Terrifying! The best short story ever written. You’re a genius! [...] Honestly, Charles -- can I call you Charles? -- I’m such a big fan.

DICKENS: A what, a big what?

DOCTOR: Fan. Number one fan, that’s me!

DICKENS: A fan? In what way do you resemble a means of keeping oneself cool?

DOCTOR: No, it means ‘fanatic,’ devoted to you. Mind you, I’ve got to say, that American bit in Martin Chuzzlewit, what’s that about? Was that just padding or what? I mean, that’s rubbish, that bit.

DICKENS: I thought you said you were my fan.

DOCTOR: Well, if you can’t take criticism. Go on, do the death of Little Nell, it cracks me up!

It’s a silly scene, and Christopher Eccleston seems to relish the opportunity to play such enthusiasm. But it’s also an educational scene. There are several references to Dickens’ writings, including some jokes about their critical reception. (Mark Twain famously criticized the death of Little Nell, and Martin Chuzzlewit’s “American bit” has indeed been met with mixed reactions.)

And there’s also an interrogation of the word “fan,” in its modern context. I especially like that Russell T Davies recognizes fans for their weirdness but doesn’t judge them for it. Like, how ridiculous is The Doctor for criticizing Dickens to his face? And yet, how many times have you seen that exact exchange go down within fandom? (I’m probably guilty of it, myself. I like to think I’d restrain myself in the presence of Mr. Moffat, and wouldn’t immediately go, “Hi. Big fan. By the way, in ‘Cold Blood,’ The Doctor says that protective mothers are the very worst of humanity. What’s that about?”)

While we’re on the subject of fandom and criticism, let’s talk about Lawrence Miles.

In the “wilderness years” of 1989 to 2005, when Doctor Who had been cancelled, a series of original novels were published to keep the franchise alive. They were aimed at a more mature audience. (Russell T Davies wrote one of these novels, called Damaged Goods. I haven’t read it, but I understand there’s a scene where a character receives oral sex in the backseat of a taxi while the world ends. Hence, mature audiences.) Lawrence Miles wrote some of these novels, and as a relatively notable and popular figure in Doctor Who lore, fans were reading his blog when the new series began. His post on “The Unquiet Dead” attracted attention, because he accused the show of advocating anti-immigrant sentiments.

I read his post when I rewatched this episode, and I found it pretty shocking. He has valid points, I think, but the apparent depth of his rage and sense of betrayal was... well, uncomfortably familiar. I’ve shouted like that about Moffat’s Who, and I’ve written angrily before about other subjects. Today, I feel like that didn’t help anything. It didn’t make me feel any better to vent, it didsn’t change the product that made me angry -- all it did was maybe earn me a couple of likes. I’m rewatching Doctor Who now to move past that kind of attitude.

Ignoring Miles’ anger, I find myself resisting his point. I can see its validity -- after all, the Gelth are aliens who wish to peacefully relocate, then reveal themselves to be treacherous. If that story existed in a vacuum, I could see how it could be interpreted as anti-immigration. But "The Unquiet Dead” engages with the progressive worldview already seen in “Rose” and “The End of the World.”

The Doctor explicitly advocates a “different morality,” to trust the Gelth and their untraditional corpse-possession practices. Faced with the same situation again, I suspect The Doctor would make the same choice.

And like the plumber Rafallo, poor Gwenyth is a working-class woman who’s accepted her indignity. (“I know it’s not my place, and forgive me for speaking out of turn,” she tells her boss.) There’s an embittered criticism of class disparity here, which anchors in a broader attitude of equality. Everyone deserves a chance in Doctor Who. Everyone is capable of grace and greatness, so we open our gates to potential immigrants.

The episode might unwittingly align with some anti-immigration values. (After all, Russell T Davies was only just learning how to plate-spin these rewrites. Mistakes are possible.) But I don’t think it matters, ‘cause the rest of the episode contextualizes it with progressive attitudes of equality. And that’s weird, ‘cause I rejected a redemptive reading of “A Good Man Goes to War” on the same grounds -- it’s possible to read the ending in a positive way, but it doesn’t matter ‘cause the rest of the episode contextualizes it in a negative way. (But that’s Series 6. I’ll get there.)

So now I’m wondering, have I just been stubbornly rejecting things to suit my own morality? I suppose we all do that. No one’s completely objective. Even kids, before they’re old enough to be prejudiced, are instinctively afraid of the dark. It feels like there are some things we have to judge as “them” or “not us,” in order to better define ourselves. But I think “The Unquiet Dead” ultimately advocates The Doctor’s “different morality,” which values trust and equality, and encourages us to be more compassionate.

#Doctor Who#The Unquiet Dead#dwre#BBC#Rose Tyler#Christopher Eccleston#Billie Piper#Charles Dickens#Simon Cowell#Russell T Davies#Mark Gatiss#Rewriting#Reaction#Monomyth#Belly of the whale#Self-reflection#Lawrence Miles#anger

0 notes

Text

Doctor Who 1x02 “The End of the World”

When the Nestene Consciousness transmitted its activation signal, Rose gasped, “It’s the end of the world!” But it wasn’t. On her first journey with The Doctor, he shows her the true end of the world. He has ulterior motives -- he can’t quite bring himself to talk about the Time War and the end of his own world, so he manipulates her into feeling that sense of loss and horror. Then, maybe she can begin to understand his alien-ness.

The idea of alien-ness is crucial to this episode, ‘cause... well, we meet a lot of aliens. And we try to understand them.

It’s an ambitious set-up, and it doesn’t totally work. For instance, there’s an extended action sequence where Rose is trapped in a locked room. She’s banging helplessly on the door, while The Doctor pokes his sonic screwdriver into some wires to free her. And it goes on forever. Even with a deadly sunbeam threatening to incinerate Rose, it’s an oddly inert sequence -- and when it’s over, Rose is still locked in that room. It feels like nothing is accomplished, although it’s actually a crafty way to let tree-person Princess Jabe take Rose’s place as companion. Jabe dies so Rose doesn’t have to.

I don’t have any suggestions for how to fix this. The structure of this episode seems necessary -- Davies had to write some simple action sequences, partly ‘cause his budget was being spent on costumes and make-up for the alien extras and partly ‘cause he had to learn what a good Doctor Who action sequence looks like. (Hint: it does not involve The Doctor standing quietly with his eyes shut, while his new friend burns to death in the background.)

The lack of strong action in this episode is well-balanced by the parade of absurd ideas that overwhelm Rose. (She didn’t have culture shock when she first stepped aboard the Tardis, but she sure gets culture shock on Platform One.) The universe’s rich and famous have gathered to watch the Earth explode, and a blue-skinned steward announces each attendee as they enter: “We have Trees: Jabe, Newt, and Copper! The Moxx of Balhoon! The Adherents of the Repeated Meme! The brothers Hop Pyleen! Cal Sparkplug! The Ambassadors from the City State of Binding Light!”

And you could argue that it’s just a nonsensical list. But nonsensical lists have a lot of potential. They’re suggestive and allusive. Nonsensical lists are what got me interested in Doctor Who in the first place. I got excited about the narrative possibilities of a list that included Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion, Doctor Who and the Cave Monsters, and Doctor Who and the Ambassadors of Death. I suppose it’s about key words conjuring powerful associations, and Russell T Davies is demonstrating here that he’s very good at picking words.

“The Adherents of the Repeated Meme” sounds spooky, and the black robed figures who accompany that name appear sinister. But, in a plot twist, The Doctor reveals that a “meme” is just “an idea,” and that the Adherents are remote-controlled robots. Diction is part of Davies’ alchemy -- because words carry the same mythic/mundane intersection potential that the rest of his story does. Words carry meaning, and they can be corrupted or appropriated for other uses. Think about what the word “meme” describes now, ten years after this episode aired.

The other absurd ideas are more personal, as befits Rose’s sphere of experience. I particularly like the bit where she meets Rafallo, the blue-skinned plumber. Their exchange makes this bizarre alien seem relatable -- she’s a plumber, she’s a long way from home -- so it matters when she’s horribly murdered by the end of the scene. But I’m still stuck on how the scene imbues Rose with a lot of social power she didn’t ask for: Rafallo needs Rose’s permission to speak, and she’s so thrilled when Rose grants that permission.

There’s a lot of political indignation peppered throughout this story. Poor Rafallo’s just trying to do her job, but she has to suffer the indignity of silence and death to serve the entitled. And, of course, Lady Cassandra -- the “last human,” merely a sheet of skin stretched out on a metal frame -- tries to sabotage Platform One and hold her fellow spectators hostage so she can steal enough money for another plastic surgery operation. Even five billion years in the future, it’s all about money.

As much as Russell T Davies is savagely mocking that kind of attitude, I still think he fundamentally respects the people who have those attitudes. Like, Cassandra’s still a developed character with at least three ex-husbands, a transgender identity, some deeply racist attitudes about “mingling,” and a deep need to stay beautiful and thin. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence that this character arrived one week after Jackie’s “skin like an old Bible” remark. As absurd as Lady Cassandra appears, her desires and attitudes are rooted in modern, recognizable concerns.

That continues to be this show’s primary tool. When The Doctor gets defensive about his identity, Rose uses contemporary references to reach out to him. “Like my mate Shireen says, don’t argue with your designated driver. Besides, it’s not like I can call for a taxi.” The Doctor keeps forgetting that things like getting a taxi, things that seem so unimportant to him, can be defining experiences for other people.

But the show never forgets that. The most exciting stuff -- the aliens, the spaceships, the Earth exploding -- becomes more potent and meaningful, because the show keeps comparing that stuff to everyday experiences, like laundry and hangovers and lottery tickets. In this era of Doctor Who, the mythic doesn’t cheapen the mundane, or vice versa. They complement each other, make both sets of experience significant and magical.

#Doctor Who#The End of the World#BBC#Christopher Eccleston#Billie Piper#Russell T Davies#Rose Tyler#Jackie Tyler#Platform One#Lady Cassandra#Douglas Adams#Satire#Edutainment#Storytelling#dwre

0 notes

Text

Doctor Who 1x01 “Rose”

Steven Moffat was just awarded the OBE for his service to British drama, so I think it might be time for me to revisit Doctor Who. There comes a time when you realize being petty -- like John Cleese in Life of Brian, berating the creative figure for making it up as he goes -- isn't helping.

This is an exorcism. Or a rehabilitation. I just want to feel better, doc...

I’ve felt bitter and angry for a while now, and much of that has to do with my relationship with Doctor Who. This show taught me how to write, how to treat others, how to survive failure and guilt and change. But then the show itself changed, and I couldn’t deal with it. So how do I move on? How do I stop clinging to the past?

I don’t know that I can talk about this succinctly. So... oy, here’s the story of me and Doctor Who.

When I was in elementary school, I noticed that my dad had some novelizations of old 1970s Doctor Who serials. I asked about them, ‘cause the hero on the front cover had curly hair like me. Old ladies in grocery stores used to ask if they could touch my curly hair, and I hated it. I didn’t like feeling “different.” I think that had to do with growing up Jewish in North Carolina, where I had to explain every year that, no, I didn’t celebrate Christmas, but yes, I did celebrate Thanksgiving. There was always this sense of Other-ness lurking in my childhood.

And here was this adventure hero who looked kinda like me. He was smart and had adventures with robots -- but unlike Worf or Tuvok, two other aliens I felt an affinity for, The Doctor was allowed to be silly and weird. And he had so many adventures! The possibilities seemed limitless...

The first book I remember seeing was Doctor Who and the Androids of Tara, the fourth in the Key to Time saga. (Again, there’s that sense of many-ness, of potential...)

So my parents rented a video of “The Five Doctors” from our local Blockbuster. It’s the twentieth anniversary special, kind of a Greatest Hits movie, with five incarnations of The Doctor contending with their most iconic foes. And again, there was that sense of limitless possibilities -- even within the hero himself, who could be a grumpy old man, an impish clown, a vainglorious snob, or just a pleasant young fellow trying to figure out who he really is. I loved The Doctor(s), Gallifrey, his enemies, and the anywhere-anywhen potential.

I began hunting for The Doctor’s other adventures. The show had been cancelled soon after I was born, so the hunt was actually pretty difficult. There were other videos, like “The Five Doctors,” but they were expensive and rare. Instead I found episode guides and behind-the-scenes books, and shelves and shelves of those Target novelizations.

The challenge made Doctor Who special. When I found a novelization I’d never seen before, it was like unearthing an ancient artifact. The stories became elevated, legendary. Most of them, I never even read -- I just read about them, and placed the precious artifacts on a shelf where they could be admired.

By the time I hit middle school, I’d tapped out the local used bookshops. I gave up expecting to find any undiscovered adventures, and I’d long since given up expecting to ever actually watch the real episodes. I boxed up the novelizations, and moved on to Pokemon and Dragon Ball Z.

Then... I found this teaser online.

youtube

It was either late 2004 or early 2005. I was in tenth grade, and the BBC had just posted this video on their new Doctor Who website. I watched the video is a poorly buffered RealPlayer window, restarting and relistening to the awkwardly mixed dialogue five times before the entire clip loaded. (Does anyone else remember doing that, with the Star Wars: Episode I teaser or anything like that? Having to replay the beginning of those clips while they buffered added urgency to those experiences -- it made them more precious and memorable.)

But that teaser couldn’t reawaken my interest. After all, the new Doctor Who would only be aired on BBC in the UK. I had no access.

Then, someone introduced me to BitTorrent. I won’t say who, ‘cause technically it’s illegal -- but I’ve thanked this person profusely and they should know now what a huge impact this had on me. For the first half of the 2005 series, I was dependent upon this intrepid BitTorrenter. Every other weekend, they’d deliver a burned CD with two more episodes. By week eight, I couldn’t wait that long, and I learned how to BitTorrent myself.

These days, I can download a HD .mkv file of new Doctor Who episodes, approximately 1 GB each, in about two hours. (Less, if I wait until the morning.) But back in 2005, it could take as much as twelve hours for a 350 MB .avi file. Once again, the difficulty of accessing Doctor Who made the stories more precious. (I'll add now, I have since purchased the DVDs of the episodes I've pirated.)

So. Here we are. It’s 2005. I’m in tenth grade. I’ve just broken up with my first girlfriend, I’m mad that I have to work harder in the math and science classes I don’t intuitively understand, and I’ve taken enough drama and film classes that I’m starting to recognize what a well-made film looks like.

Cue the theme music.

youtube

From the first frame, it’s remarkable how similar this is to the old title sequences: the colors, the shapes, even the basic orchestration of the theme song. This is by design. Head writer and showrunner Russell T Davies is a self-proclaimed fan of the original series, slipping references to it into his previous works -- notably Queer as Folk. It was a huge deal for a writer of his caliber and acclaim to volunteer for this job. (Not that I knew that, at the time.) And Doctor Who had become kind of a joke in the UK: a cheesy, though memorable, kids’ show that outstayed its welcome, until it couldn’t compete with flashier SF like Star Trek: The Next Generation and The X-Files. So when Davies took the reins, no one knew what to expect.

And it’s essentially the same. Davies brings back the sonic screwdriver, The Doctor’s favorite all-purpose tool; the Tardis, a time machine disguised as a blue telephone box from 1960s England; and the Autons, living shop window dummies that tried to invade Earth back in the 1970 serial “Spearhead from Space” and again in 1971′s “Terror of the Autons.” This all feels familiar, and yet there’s a newly modernized focus on human beings.

The script for “Rose” (yes, I have the scripts, of course I have the scripts) begins thusly:

EXT. FX SHOT

The planet Earth drifting in space, silent, serene. Suddenly -- the beep-beep-beep of an alarm clock.

CAMERA races towards the Earth, plunging down, down, down through the clouds, revealing the UK, down towards London, a grid of buildings, zooming down to a block of flats --

INT. ROSE’S BEDROOM - DAY 1 0730

CU a black, square alarm clock. A hand slams it off. ROSE TYLER sits up in bed, gathers herself for a second. She’s 19, her bedroom’s a mess, she’s got another bloody day at work, and she’s so much better than this. Ho hum. Deep breath, and Rose throws the quilt off.

I love this beginning. The first shot gives you the scope of the show’s premise: we know we’re heading Out There. But first, he explains to you why Out There matters. The actual stage directions communicate the pacing (“down, down, down”) until we find Rose. And with one glimpse, we all know her. We recognize her. We probably identify with her. (Though, I’m still waiting for an Other to arrive.) That sense of “so much better than this” is universal. You may have read my thoughts about superhero stories, and how they establish both a mythic and a mundane space for their character to navigate. Rose is someone whose life is entirely mundane in the beginning, and we already have the sense that Out There -- in time, in space -- is her myth. Her story can be more exciting, more satisfying. Who can’t relate to that?

It must have been bizarre for British audiences to see teen pop idol Billie Piper branch out into acting. At the time, I remember reading comparisons like Billie Piper was the UK’s Britney Spears. And here she was, leaving one creative space and entering another. I can’t imagine a better story for crossing thresholds than Doctor Who.

This show is about boundaries between spaces, both diegetically (that is, within the world of the story) and non-diegetically (in the world outside the television, where you are watching the story). When this episode first aired in the UK, a broadcast error made audio from another channel bleed into the opening minutes. The downloaded copy of this episode that I first saw included this audio bleed. Philip Sandifer, occult Doctor Who blogger extraordinaire, had a really great essay about “Rose,” including some neat observations about the audio invasion:

...there is the banishing of Graham Norton. “Am I here,” he asks, and mere moments later the Doctor tacitly answers, no, you’re not. I am.

The Doctor’s arrival heralds the establishment of a threshold, or perhaps more accurately, a narrative tool for navigating thresholds. Christopher Eccleston’s performance speaks to this navigation. Even in his first scene, he transitions between different modes: he’s unfazed by the living dummies (“Run!”); he’s delighted with Rose’s cleverness (“That makes sense, well done!”); he’s stoic again about the death of Wilson, the shop’s chief electrician; and finally, he strikes a balance between the two, silly and heroic. “Nice to meet you,” he says with a smile. Then, he bellows, “Run for your life!”

youtube

I like that The Doctor slams the door on her, physically separating Rose from the basement and pushing her back into the mundane world. But transitions are costly and messy in Doctor Who -- you can’t go home without taking something with you, so Rose returns with a severed plastic arm. The arm links Rose back to The Doctor’s mythic world, and it represents one of the show’s primary narrative devices: embedding the mythic within something familiar and mundane.

I’m sure I recommended this show to some friends in high school, and they gave up when they reached the flying arm (or the burping trash can). I’ll admit, it’s goofy. Actually, it’s more than that: it’s campy.

Via Susan Sontag:

“...camp is art that proposes itself seriously, but cannot be taken altogether seriously because it is ‘too much.’ ... the essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails. Of course, not all seriousness that fails can be redeemed as Camp. Only that which has the proper mixture of the exaggerated, the fantastic, the passionate, and the naïve.”

So, like, two people fighting with a flying plastic arm.

Camp has been an important aesthetic tool for the gay community. As an openly gay writer, Russell T Davies received a lot of criticism while he was writing Doctor Who for pushing a “gay agenda.” Turns out, he was absolutely pushing a gay agenda -- but it wasn’t about converting children into being gay. It was about converting children into accepting everyone, regardless of race or class or gender or sexual orientation. (No overtly gay characters in this episode, but Rose is in an interracial relationship with Mickey. The world is full of possibility.)

Watching Rose and The Doctor roll around her living room floor with a plastic arm is campy -- and it transmits to everyone who feels that sense of Other-ness that this is a safe space for us. Nothing here will be called weird or wrong.

I think the success of Doctor Who’s camp lies in Russell T Davies’ commitment to grounding the mythic in the mundane. Everything has a reason. Jackie doesn’t hear her daughter and the strange man crush her coffee table in the next room because she’s blowdrying her hair. Rose doesn’t notice that her boyfriend has been replaced with a plastic duplicate because she’s selfishly ranting about herself. The world doesn’t notice that aliens have invaded Britain’s shops because they’re too busy eating and sleeping and watching TV.

You can summarize the campy gay agenda as, “Everything you know and trust is concealing something magical and mysterious -- and isn’t that wonderful??” This attitude expands to a grandiose level when the episode reveals that an apocalyptic weapon has been concealed within a major London landmark. If you’re actually comfortable in your sexuality, then this kind of storytelling is really exciting! I love that, as The Doctor realizes that the London Eye is the round and massive transmitter he’s seeking, the music kicks in to punctuate a triumphant moment of realization. It makes the act of learning -- crossing a threshold from mundane ignorance to mythic insight -- into something valuable, triumphant! “Fantastic!”

And when the world is so outrageously fantastic, Rose’s dramatic function becomes clear: she reminds The Doctor of the mundane world he’s forgotten. When she crosses the threshold into the Tardis, she cries. The Doctor assumes she has culture shock, but no, she’s worried about people. “Did they kill Mickey, is he dead?” The Doctor resists her association with the mundane (“Can we keep the domestics outside?”), and he seems happiest when things are most chaotic: he grins when Mickey’s headless plastic duplicate rampages through a restaurant, and when the Nestene Consciousness’ secret base starts collapsing around his ears. But this adventure makes him realize that he needs someone like Rose to remind him that there are shopping malls and spreadsheets at stake, and that those things matter.

The space where this intersection of mythic and mundane is most readily apparent is, of course, the Tardis set. (I suppose technically it should be “TARDIS,” since it’s an acronym for “Time and Relative Dimension(s) In Space.” But I prefer “Tardis,” because if you have to write the word in a screenplay, capital letters are usually reserved for scene headings, character names, or sound effects.)

Traditionally, the Tardis interior is a vast white sci-fi laboratory nestled inside a recognizable British icon. But for the 2005 series, the interior becomes a gold-and-green dome, a cross between a laboratory (with makeshift controls and metal gangplanks) and a cathedral (amber lighting and coral columns). When we get our first glimpse of it, the soundtrack gets very moody and spiritual. Everything in Russell T Davies’ version of Doctor Who has multiple allegiances. Everything intersects. Meaning erupts from those intersections. The Tardis is a place where science and spirituality intersect, and when you open those doors and cross the threshold, anything can happen.

When Steven Moffat took over, the Tardis set expanded -- it got a second level -- but it just feels like a sci-fi set to me now. There’s nothing spiritual, nothing organic. It just does one thing now. That’s so weird, ‘cause the second level gives an opportunity for the kinds of ascents and descents that Russell T Davies writes: gloriously selfish Rose descends into mythic spaces in the shop’s basement and beneath the London Eye, and ascends back into the mundane world with new knowledge of selfless acts. The Doctor gives her an opportunity to feel selfless, so she selfishly leaves her mundane world behind. That’s not just mythic, that’s archetypal.

Here’s the thing.

I love Russell T Davies’ Doctor Who, because I believe it is a good story. It’s well-made and has positive values.

There are stories that I like that are not good. Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance is very entertaining, but it is a clusterfuck of bizarre acting, disorienting cinematography, and unclear ethics. But, you know, Nic Cage pisses fire in one scene, so I roll with it.

Right now, I believe that Steven Moffat’s Doctor Who is just bad. It’s structureless and cruel. I don’t have a problem with people liking his version, but I do have a problem with people calling it “good.” So my biggest hope for this rewatch is that I’ll either discover something that recontextualizes my views on Moffat’s Who, or I’ll figure out how to live in a world where everyone -- including the Queen of England -- has such different values than mine.

As I finish rewatching “Rose,” I’m thinking about the value of access, and how the difficulty of accessing earlier Doctor Who stories made those stories seem more valuable. Maybe part of my problem with Moffat’s Who is that it’s just too accessible: it’s easy to find and to watch. Does that diminish its quality? Am I just mad that the show is popular? (I’m not above that. I wandered away from the Harry Potter books for a few years, when Order of the Phoenix came out, ‘cause no one would shut up about it. I’ve since returned to the fold.) Or has the show actually changed so substantially that it’s no longer the same show? I’ll try to keep an open mind about this, as I continue.

Now, if you’ve made it to the end with me, I’ll let you in on a little secret.

I watched this episode last night in my childhood bedroom, grinning like a lunatic and clutching my toy sonic screwdriver. (Ninth and Tenth Doctor model, obvs.) They say you can’t go home again, but Doctor Who somehow defies that adage. It’s about time travel and limitless possibility, so of course it can take you home again. That’s magical. I feel a little better already, Doc.

#Doctor Who#Rose#BBC#Ninth Doctor#Rose Tyler#Mickey Smith#Jackie Tyler#Autons#Nestene Consciousness#Living plastic#Russell T Davies#Tardis#Storytelling#Target novels#BitTorrent#Christopher Eccleston#Billie Piper#dwre

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Batman Beyond 1x01/02 “Rebirth”

Batman: The Animated Series was stylish and sophisticated, but I quickly got tired of the Dark Knight's inability to change. The series tries to mitigate that by teaming him with actual humans, like Dick and Barbara and Tim. But he's still the center of the show, and I don't care as much about Batman because I don't aspire to be like him. I don't want to sacrifice all of my mundane, personal attachments to become something purely mythic. I want to integrate my mundane qualities into a mythic life. That, I think, is why I enjoy Batman Beyond. Sure, it's set in the future, so there are robots and flying cars. But the real benefit of setting a Batman story in the future is that, even if Bruce Wayne won't change, he can't stop the world around him from changing. Change happens, whether Batman wants it to or not. The future corrupts Bruce's body, his company, and his city.

Neo-Gotham runs rampant with Jokerz, naive gangsters who've appropriated the image of Batman's most dangerous foe -- and they're just pathetic. But more offensive to him, surely, is Bruce's inability to fight aging. In the pre-titles sequence, he suffers a heart attack and resorts to wielding a gun in self-defense... violating his most hallowed code, brandishing the very weapon that murdered his parents and sent him on this crusade. It breaks him. (He changes!)

Enter Terry McGinnis: a brash teenager, a product of a broken home. He's a cross between the surly post-apocalyptic bikers of Akira and the recognizably self-obsessed students from early Spider-Man comics. He's liminal in a way that Bruce Wayne never was. As a teenager, he's between childhood and adulthood; between parents; and between justice and lawlessness.

The new Batsuit is brilliantly designed to externalize Terry’s liminality. The animators ditch the iconic cape in favor of a form-fitting bodysuit -- where is the edge between the mask and Terry’s face? Body and suit blend together, becoming a nexus point for all the boundaries that Terry crosses. Meanwhile, Old Bruce is much more compelling to me as a sturdy, unyielding mentor. There's less pressure for him to be a dynamic character in this capacity. (Dynamic, in the literary sense of, “can he change?” And no. He can't. Batman is a static character. Which isn't an empirically bad thing, it just means that I don't like him.)

These strong characters are established in a more serialized world than B:TAS. There’s still a sense of the episodic, with Bruce hiring Terry as his “gofer.” We anticipate that, with Terry having a mundane reason to stick close to Bruce, they’ll be able to cooperatively battle Neo-Gotham’s next villain-of-the-week. But that’s not how the episode ends. Instead, we cut to a secret Wayne/Powers lab, where slimy CEO Derek Powers has been transformed into an irradiated glowing skeleton. It’s a cliffhanger that won’t be immediately resolved, but it suggests that Terry’s story, unlike Bruce’s, will have some sense of linear progression.

#Batman Beyond#DCAU#Batman#Neo-Gotham#Terry McGinnis#Bruce Wayne#Derek Powers#DC Entertainment#Animation#Blight

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Don’t worry, she’ll be bad at it.

322 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wendio music.

Feast on your ears on this! Preorder all four volumes of original music from Hannibal composed by Brian Reitzell on vinyl here.

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Quantum Leap 2x08 "Jimmy: October 19, 1964"

Al's not allowed to tell Sam anything personal, due to some hazily-defined rules about the project. (Maybe Ziggy's still running tests on Sam, including how quickly he recovers his memory -- and filling in the blanks would mess with the data? That's just me making things up, but it's as good a reason as any.) But, despite how much he withholds, I still feel like I know Al pretty well. Each piece of his backstory that falls into place just makes sense. I get why he's a cad, and how he can also be capable of such progressive empathy.

"Jimmy" reveals a key part of Al's character: he grew up with a young sister who had special needs. This was before the major effort to "mainstream" the developmentally disabled; the stress and confusion surrounding Trudy's situation tore Al's family apart. (His mom ran away, and his dad shacked up with a series of girlfriends thereafter: hence, Al's womanizing.) He holds himself partly responsible for failing to take her out of the institution, where she allegedly died of pneumonia. (Hence, Al's involvement in various civil liberties campaigns -- he's trying to make up for that failure.)

Because the characters had such a personal investment in this issue, I really noticed how this episode, so early in Quantum Leap's run, stopped talking about changing the world. Sam and Al discuss the historical context for the situation, but Sam doesn't leap into Jimmy's life to reform the system -- he's simply there to earn acceptance for Jimmy, to improve this one man's life.

I found it a little challenging to watch, honestly, 'cause the situation was just so intense. That's not to say that racism and sexism aren't intense issues, but we have words to describe those situations. It's easier to contextualize and empathize with victims of those prejudices. I don't think there is a word for prejudice against the developmentally disabled.

As Jimmy, there's constant pressure and frustration heaped upon Sam. It's not like anything he does is so catastrophic: he drops some plates, and does a poor job at washing a car. If someone who wasn't disabled did those things, it would be written off as a mistake. But, as Jimmy, every mistake feels magnified, 'cause everyone's upset with him all the time, and it's agonizing to watch. No one in Jimmy's life understands what's going on -- there is no "whole word" to talk about it.

But you have to call it something, or else you can't address it. And, for my money, Quantum Leap is at its best when it addresses these kinds of issues, when it helps audiences to empathize with people they don't understand.

This episode aired in 1989, and already, everyone's embroiled in a difficult discussion about what we call it. Jimmy's brother Frank insists that Sam refer to it as being "slow," not "retarded." Sam suggests that he's "special." Outside the show, in 2006, the American Association on Mental Retardation elected to change its name to the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. We just can't decide what to call it.

The terminology subsection on Wikipedia's intellectual disability page is fascinating, 'cause you can see just how charged and problematic it's been. "Retarded" was introduced as a neutral replacement for derogatory terms like "cretin" and "imbecile," but the social stigma of this disorder corrupted the new term's neutrality.

The fact that Quantum Leap engages with this discussion at all is huge. They're not out to solve a global problem, they just want to acknowledge that a problem exists in how we perceive and treat those who are different than us -- whether they have a different gender, race, or degree of cognitive function. So there's much less emphasis on the wider ramifications of Sam's leap this time.

Although he references Star Wars, the show doesn't insert a young George Lucas getting a bright idea. (Whereas, in the previous episode, there's a gag where Sam performs the Heimlich maneuver on a choking man, who turns out to be Dr. Heimlich himself.) And we don't get the familiar moment at the episode's conclusion where Al reads from his glittery LEGO and confirms that everyone will now live happily ever after. No, the only reward in this episode is Jimmy's acceptance by the dock workers.

And that only comes about because Sam, as Jimmy, performs C.P.R. on a drowned boy. Once again, I'm left wondering what happens to the host body's consciousness after Sam leaps. I guess it's possible that Jimmy did (or could) know C.P.R., but the drama of that scene hinges on the idea that Sam -- with his six doctorates! -- knows something relevant that Jimmy may not. He can give everyone a reasonable explanation for how Jimmy could have learned such a thing. But if Jimmy himself doesn't actually know C.P.R., or (maybe more relevantly) doesn't remember performing C.P.R., then couldn't he undo all the work Sam just did? Or are we supposed to believe that Sam's efforts have changed Connie and the dock workers, so they'll give Jimmy the benefit of the doubt, even if he insists that he's never performed C.P.R. in his life?

I really like the focus that this episode took with improving one man's life, rather than attempting huge societal reforms. But I wonder how effective intervening in someone's personal life can be. How can you prevent the same mistakes from happening when you're no longer there to intervene? That's quite a leap of faith...

#Quantum Leap#Jimmy#1964#Sam Beckett#Al#Time travel#Special needs#Developmentally disability#Retarded#Empathy#Faith#Terminology#Words

1 note

·

View note

Text

Quantum Leap 2x04 "What Price Gloria?"

When Sam was Jesse, he made a point of noting the differences between himself and a black man. Jesse was a role he could play, while still maintaining his internal identity as Sam Beckett. But, when he inhabits the body of Samantha Stormer, the boundary between male Sam and his female host gets blurred.

This manifests on screen when Scott Bakula paints his nails, curls his hair, applies lipstick, wears dresses and earrings, and walks in high heels. As previous male characters, Sam's only ever had to change clothes -- and there were always moments in the episode where he could drop the facade and speak to Al as himself. There are no such opportunities in this episode. Even leaping into the body of someone named "Sam," Dr. Beckett never gets a chance to stop performing.

And I think that's what the episode is suggesting about Samantha Stormer, as well. Even without Sam's consciousness using her body, she still has to wear all that makeup. She has to perform a version of herself that's socially acceptable. That kind of masquerade is demeaning; the women in this story are so used to determining their worth via approval from their bosses and peeping neighbors, their sense of self diminishes.

Thus, "What Price Gloria?" handles the issue of prejudice much more elegantly than "The Color of Truth." Sam tried to confront racism in a more global sense -- he wanted to kickstart integration in the Deep South. Here, he flirts with the idea of making a similar gesture for emancipation, but the true effectiveness of this leap lies in how he affects individual lives. He prevents Gloria from committing suicide over an affair with a married man, and inadvertently guides Samantha to becoming a successful car designer and single mother.

And even more significant is the impact this leap has upon Sam himself. Experiencing life as a woman enables him to take some control over his time-traveling. Typically he has very little control over when he leaps: he and Al determine a task, accomplish it, then God whisks him away to the next adventure. This time, even after rescuing Gloria and bolstering Samantha's future, Sam manages to delay the leap... by hoping for revenge on Samantha's misogynistic boss, Buddy.

Frankly, I'm not quite sure what to make of that. Especially 'cause Al sums up the situation as "very female." I feel that Al can get away with speaking a lot of sexist horseshit, 'cause typically he's on the side of the angels. We know he was active in the civil rights movement, so he's socially progressive. He supports Sam, and in this episode, even admits to loving him (as a best friend). But those positive qualities are balanced out by the fact that he's a womanizing sleazebag. That works dramatically, 'cause it gives Al a flaw that makes him more human and therefore relatable, and because this episode specifically criticizes sexism. But I'm still not sure whether the show, by extension, criticizes Al for being sexist.

He's particularly bad about it in this episode. We learn that Al sees the host body, rather than Sam's own -- and Samantha is very attractive. This contributes to the blurred boundary between Sam's and Samantha's identities. Al's so busy lusting over Samantha's body that he can't recognize Sam or treat him as a friend, so Sam never really gets a chance to stop being Samantha, to stop "being" a woman, to be himself.

Al's line -- "Very female." -- sticks out to me, 'cause it seems to indicate two different concepts. Al still treats women as The Other, as if vengeance is a uniquely feminine thing; yet Sam has seemingly erased his personal sense of a gender gap. I think he wants revenge 'cause all people, regardless of gender, should resist the kind of victimization that women endure.

In retrospect, the episode never makes that explicit. And the nature of Sam's revenge complicates that idea, 'cause his plan is to seduce Buddy, then reveal that he's a dude. It's a bizarrely cartoonish sequence, culminating in a sucker punch with chirping bird sound effects, and it all seems to hinge on humiliating someone for a same-sex attraction -- and that opens up a whole new can of worms about treating crossdressers or transgendered people as The Other.

Maybe that's an unfair reduction. Maybe it's not Sam humiliating Buddy for being attracted to a man, maybe it's more like Sam destabilizing Buddy's sense of identity. Sam shifts the power dynamic in that office, makes Buddy feel objectified and preyed upon -- and, to achieve that, Sam leads Buddy to question the ideas that his own identity and prejudices were founded upon: namely that, as a man, he is superior to women.

So, I don't know. It's a complex scene, and it's very visually inventive, too! The camera keeps passing a mirror in Buddy's office. In the foreground, we see Bakula as Sam, wearing a dress and using feminine body language to seduce Buddy; while in the reflection, we see the actress playing Samantha wearing the same costume and making the same gestures. From a technical standpoint, it's expertly done.

(For what it's worth, I found an interview with Scott Bakula about how they filmed the reflections in "The Color of Truth." Apparently, they constructed two adjacent sets, and had identical actors wearing mirrored versions of all costumes. Sounds complicated!)

It's peculiar, watching this episode -- particularly the revenge scene -- in 2014, when the "Like A Girl" video just went viral. 'cause, at one point, Sam crows, "Let me show you how I throw a ball!" Oof. While Sam should have just spent the last 45 minutes learning that men and women should be treated with equal respect, he still ends up making a "throw like a girl" joke. And so I have no idea what the show meant, when Al called Sam's revenge plans "very female." In the end, what is Quantum Leap even saying about gender?

I wonder if all this backtracking is a symptom of Quantum Leap being a network TV show in 1989, or if it's an intentional statement by the show's creators. Either way, the show keeps encountering the same limitation -- Sam's only real power is affecting personal, individual change; never universal change. He can't break down the boundaries between genders or races; he can't make everyone treat women equally. But he can make sure that Samantha and Gloria (or whoever, regardless of race or gender) get to lead more satisfying lives.

#Quantum Leap#What Price Gloria#1961#Sam Beckett#Al#Sexism#Crossdresser#Equality#Feminism#Emancipation#Women's lib#Revenge#Gender#Identity

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You can't do that.

115K notes

·

View notes