Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

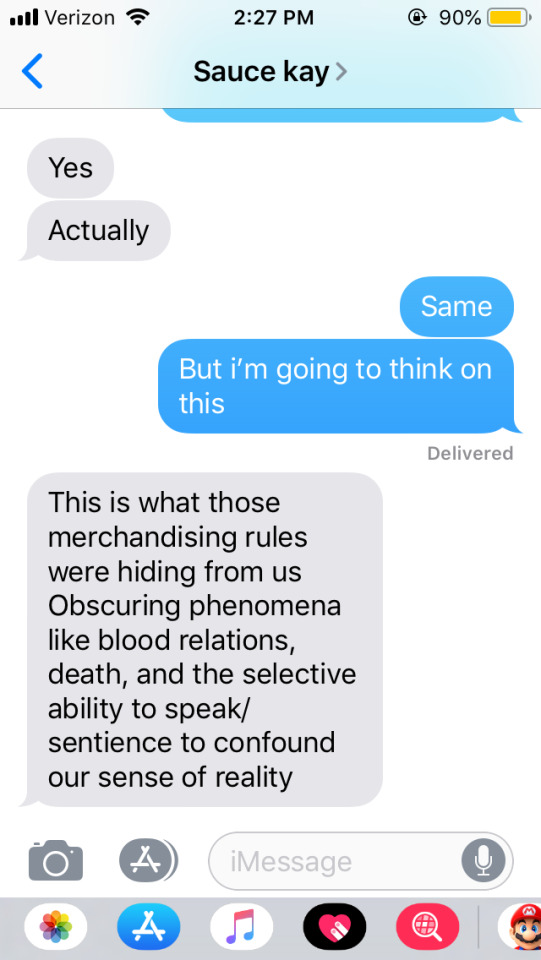

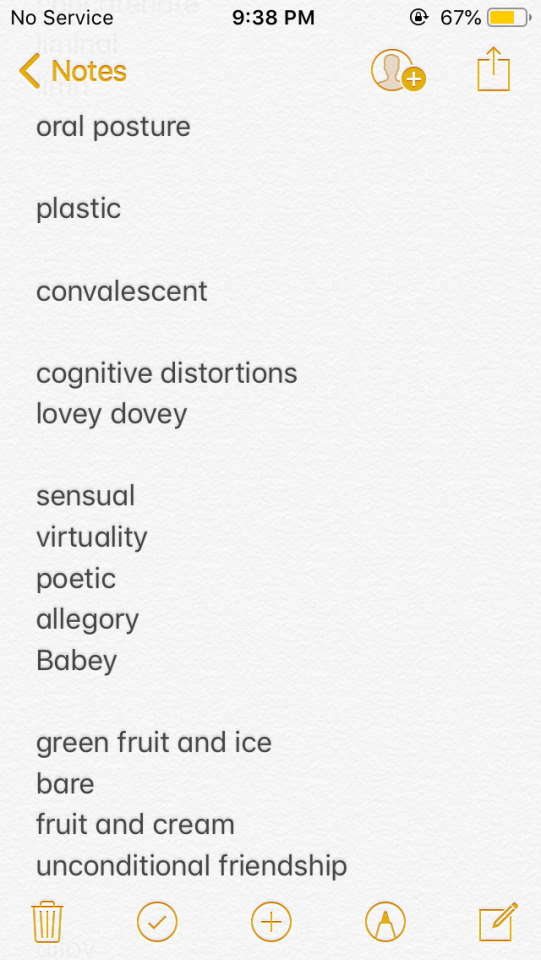

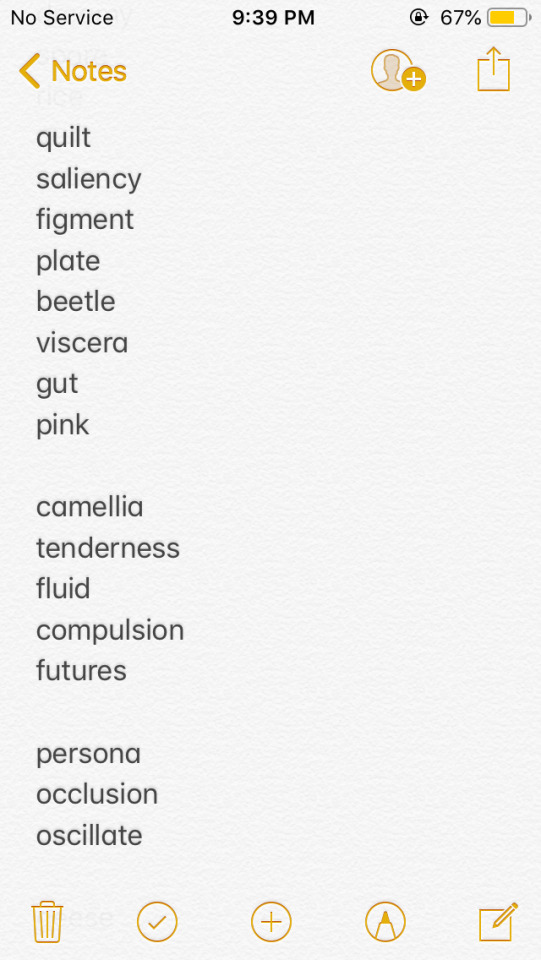

materia, 2018-2019

I don’t get a lot of time to read on my commute from my home near the university to downtown. Many of my colleagues have a long commute on which they read their books (which we go over in our work book club, something I really love to listen to. My commute is chopped up and I spent a lot of time going up and down stairs or weaving between people.

My return commute is longer (an hour or more) and much less hurried, and late night buses are infrequent. While I’m waiting for a bus or a train, I sometimes add to a body of my favorite words, or word sounds, ordered and spaced according to how I want them to sound together in this concatenation. It’s calming and feels like a puzzle, or the last stretch of editing an essay or a letter when you want to communicate something very subjective with the most specificity (also subjective). It feels satisfying, healthy, and sharpening.

I first shared this on my Instagram stories in June. I had taken the train in the wrong direction, had to get out and run to the other platform, and wait about fifteen minutes in the tunnel. I rearranged some things before taking screenshots - I was planning on getting a new phone soon, and wasn’t sure if my notes would make it because I never back it up, and the visual references felt genuine and I want to be more in the habit of allowing the small creative habits I’m trying to maintain to carry the same importance I used to reserve only for painting. It seemed to resonate with my friends, which was nice, since it feels like sharing a very private artifact but knowing that they found it pleasant to read too was a pleasure. Pleasant.

The first word is from the title of a publication by Japanese photographer Rinko Kawauchi. I love her work, but I’m unsure in what form “Materia” actually exists because I saw the cover from a Tumblr post, the same way I discovered her body of work, and it’s not on her website.

I first heard the word “materia” as the Final Fantasy term for powers/abilities/knowledge. Of course that’s just been a point of departure for developing a difference sense of the word, but I think of that first.

Certain other words on the list come from internet searches, articles, jargon that you hear a lot in exhibition titles and the smattering of graduate degrees dealing with digital or new media art in some way (a degree in “digital futures,” ... also things like Speculative Ecologies or Poetic Computation) . And other words used to talk about symbols or gestures in modern painting, popular in writing probably from the 60s through the 80s, in reference to Rauschenberg or Gorky (reify, oscillate, allegory). Some are from video games. Some are food items, usually in a mental image of in that vibrant, highly saturated hue of a dye transfer print because produce is aesthetically beautiful, sculptural and totally mundane and poetic. On its own. There is a lot of labor that goes into farming industry and marketing produce to put the melon on the stand, which is not what I always think of when I get the melon out of season and out of the region where I live. The melon is also the rectangular prism of the Melona ice cream. Green fruit and ice is editorial. Rice is nostalgic.

A lot of them are words I use to describe my feelings in therapy. Sediment, threat, compulsion, self-possessing, though these are all terms that can be applied to artwork as well. I like that they are aspirational, in terms of how I want to be, and critical of how I feel. And not all of them have singular images or meanings. They belong under materia for that. There are more lists in materia, but these make the most sense together.

I know this blog was created for class, and I intend to keep adding excerpts from books, articles, texts relevant to embodiment, landscape, technology and perception, and navigation. materia is an organized reminder of recurring themes (visual motifs, aural motifs, tangential to embodiment or perception or memory), and I’ve been reading too many good things to not try to connect them back to one another - in my conversations, in small moments of video that remind me of those themes, in game tropes or mechanics or emulations, or poetic writing - using links, tags, and a platform that allows reblogging, or easier appropriation of those images and the chain of provenance. I’m aiming for something essayistic, something like an index for that reading, a database for things I forget and then remember and forget. I kind of hate that Facebook allows you to remember people you could have forgotten happened to you, and how it prolongs some acquaintanceships/connections/relationships longer than is natural for the memory. I know a lot of things that aren’t my business, and that those things show up on my internet activity alongside things that I forget too quickly.

It’s a repository for sediment and it’s not that deep but it’s more visible and more connected than separated by written pages or filed away, so thanks

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The goal of some Post-Internet practices is to engage with this proliferation of images and objects -- “general web content,” items of culture created without necessarily being described as art -- and proclaim an authorial stance by indexing / curating these objects. These projects are as wide-ranging as Jon Rafman’s “Nine Eyes of Google Street View” project and some of the earlier works done by Surf Clubs and their participants, among them Guthrie Lonergan who was one of the first artists to release works in the form of YouTube playlists. Artists after the Internet thus take on a role more closely aligned to that of the interpreter, transcriber, narrator, curator, architect.

This is often broadly ascribed to traditions of artists dealing with the banal, the everyday: “surfing as art” articulating quotidian Internet-user “tactics” or the artists acting, essentially, as ethnographers who would chart and explain the new variety of images found within visual culture. I would argue for a slightly different case.

In his essay On the New, Boris Groys writes:

… art can [become unusual, surprising, &c.] only by tapping into classical, mythological, and religious traditions and breaking its connection with the banality of everyday experience. The successful (and deservedly so) mass cultural image production of our age concerns itself with attacks by aliens, myths of apocalypse and redemption, heroes endowed with superhuman powers, and so forth. All of this is certainly fascinating and instructive. Once in a while, though, one would like to be able to contemplate and enjoy something normal, something ordinary, something banal as well … In life, on the other hand, only the extraordinary is presented to us as a possible object of our admiration.

But just as any object is conceivably any other object, our ubiquitous authorship marks a point in cultural production at which the extraordinary is now also the ordinary -- the myth is also the everyday. In many of my video works, I make a point to appropriate imagery from recent popular films, mass media spectacles made with all of the fervor and resolution of an empire that only partially realizes its own decay. The striking thing about these images is not their content but their availability and the context within which they are now received. Where once an experience of cinema was that of receiving an absolute, fixed icon -- a definitive copy, inaccessible and precious -- that is now far from the case. Cinema now becomes encapsulated, transferrable and transformable in the same vain [sp] as everything else, a ‘file’ to be treated with all the levity we reserve for any other file.

The images I deal with in my work, authentic unauthorized copies of spectacle films, thus represent the absolute collapse of the mythological and the quotidian into a single indistinguishable whole.

The goal of organizing appropriated cultural objects after the Internet cannot be simply to act as a didactic ethnographer but to present microcosms and create propositions for arrangements or representational strategies which have not yet been fully developed. Taking a didactic stance amounts to perpetuating a state of affairs of art positioned in contradiction to an older one-to-many hierarchy of mass media. For the new hierarchies of many-to-many production, the cultural status of objects is now influenced entirely by the attention given to them, the way they are transmitted socially and the variety of communities they come to inhabit.

Thus in the same way that all cultural images and objects become general -- the film Independence Day being not dissimilar in homogeneity and degree of spectacle from any individual’s photos of their newborn child on Facebook -- so too does the authorial stance of the artist become general. Any sorting of images or aspects of culture, applied with a declaration or narrative gesture, becomes not dissimilar to our experience of everyday life, regardless of the degree to which images are spectacular. What comes to matter is not that an artist has presented some aspect of the spectacle and how it fits neatly into some aspect of a linear historical trajectory. What matters is that in the presentation they have created a proposition towards an alternate conception of cultural objects.

#Vierkant#Artie Vierkant#The Image Object#curation#banal#Internet#post-Internet#self reflexive#lol#images#social object#Boris Groys#Essay On the New

0 notes

Photo

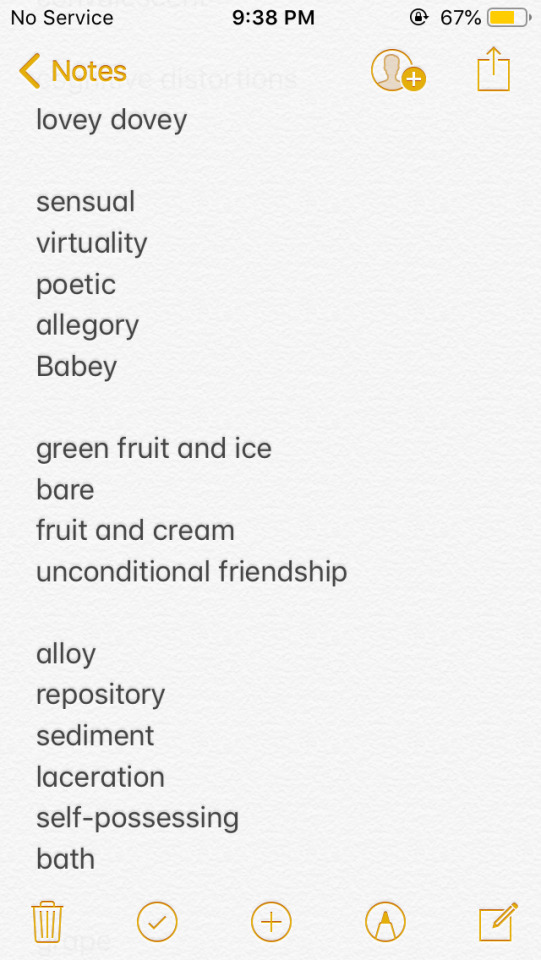

Cerith Wyn Evans, installation view at indoor stone garden “Heaven,” The Sogetsu Kaikan, Tokyo, Apr 13 – 25, 2018. Photo: Kenji Takahashi

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

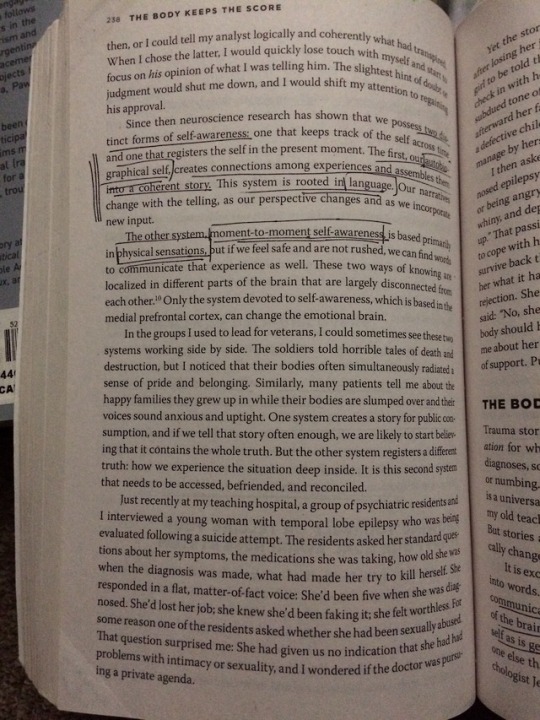

Of The Survival of Images: Memory and Mind

To sum up briefly the preceding chapters: we have distinguished three processes, pure memory, memory-image and perception, of which none o f them in fact, occurs apart from the others. Perception is never a mere contact of the mind with the object present; it is impregnated with memory-images which complete it as they interpret it. The memory-image, in its turn, partakes of the “pure memory,” which it begins to materialize, and of the perception in which it tends to embody itself: regarded from the latter point of view, it might be defined as a nascent perception. Lastly, pure memory, though independent in theory, manifests itself as a rule only in the colored and living image which reveals it. Symbolizing these three terms by the consecutive segments AB, BC, CD, of the same straight line AD, we may say that our thought describes this line in a single movement, which goes from A to D, and that is impossible to say precisely where one of the terms ends and another begins.

In fact, this is just what consciousness bears witness to whenever, in order to analyze memory, it follows the movement of memory at work. Whenever we are trying to recover a recollection, to call up some period of our history, we become conscious of an act sui generis by which we detach ourselves from the present in order to replace ourselves, first, in the past in general, then, in a certain region of the past -- a work of adjustment, something like the focusing of a camera. But our recollection still remains virtual; we simply prepare ourselves to receive it by adopting the appropriate attitude. Little by little it comes into view like a condensing cloud; from the virtual state it passes into the actual; and as its outlines become more distinct and its surface takes on color, it tends to imitate perception. But it remains attached to the past by its deepest roots, and if, when once realized, it did not retain something of its original virtuality, if, being a present state, it were not also something which stands out distinct from the present, we should never know it for a memory.

The capital error of associationism is that it substitutes for this continuity of becoming, which is the living reality, a discontinuous multiplicity of elements, inert and juxtaposed. Just because each of the elements so constituted contains, by reason of its origin, something of what precedes and also of what follows, it must take to our eyes the form of a mixed and, so to speak, impure state. But the principle of associationism requires that each psychical state should be a kind of atom, a simple element. Hence the necessity for sacrificing, in each of the phases we have distinguished, the unstable to the stable, that is to say, the beginning to the end. If we are dealing with perception, we are asked to see in it nothing but the agglomerated sensations which color it and to overlook the remembered images which form its dim nucleus. If it is the remembered image that we are considering, we are bidden to take it already made, realized in a weak perception, and to shut our eyes to the pure memory which this image has progressively developed. In the rivalry which associationism thus sets up between the stable and the unstable, perception is bound to expel the memory-image, and the memory-image to expel pure memory. And thus the pure memory disappears altogether. [...] Psychical life, then, is entirely summed up in these two elements, sensation and image. And as, on the one hand, this theory drowns in the image the pure memory, which makes the image into an original state, and, on the other hand, brings the image yet closer to perception by putting into perception, in advance, something of the image itself, it ends up by finding between these two states only a difference of degree, or of intensity. Hence the distinction between strong states and weak states, of which the first are supposed to be set up by us as perceptions of the present, and the second (why, no man knows) as representations of the past. But the truth is that we shall never reach the past unless we frankly place ourselves within it. Essentially virtual, it cannot be known as something past unless we follow and adopt the movement by which it expands into a present image, thus emerging from obscurity into the light of day. In vain do we seek its trace in anything actual and already realized: we might as well look for darkness beneath the light. This is, in fact, the error of associationism: placed in the actual, it exhausts itself in vain attempts to discover in a realized and present state the mark of its past origin, to distinguish memory from perception, and to erect into a difference in kind that which it condemned in advance to be but a difference of magnitude.

To picture is not to remember. No doubt a recollection, as it beomes actual, tends to live in an image; however, the converse is not true, and the image, pure and simple, will not be referred to the past unless, indeed, it was in the past that I sought it, thus following the continuous progress which brought it from darkness into light. This is what psychologists too often forget when they conclude, from the fact that a remembered sensation becomes more actual the more we dwell upon it, that the memory of the sensation is the sensation itself beginning to be. The fact which they allege is undoubtedly true: the more I strive to recall a past pain, the nearer I come to feeling it in reality. But this is easy to understand, since the progress of a memory precisely consists, as we have said, in its becoming materialized. The question is: was the memory of a pain, when it began, really pain?

Bergson, Henri. Matter and Memory. Translated by N.M. Paul and W.S. Palmer. New York, NY: Zone Books, 1991. 132-136.

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

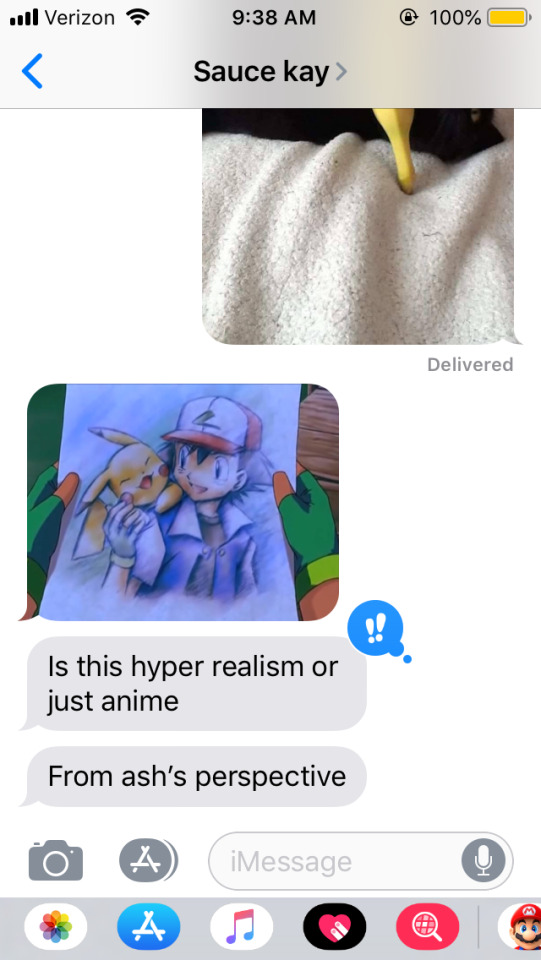

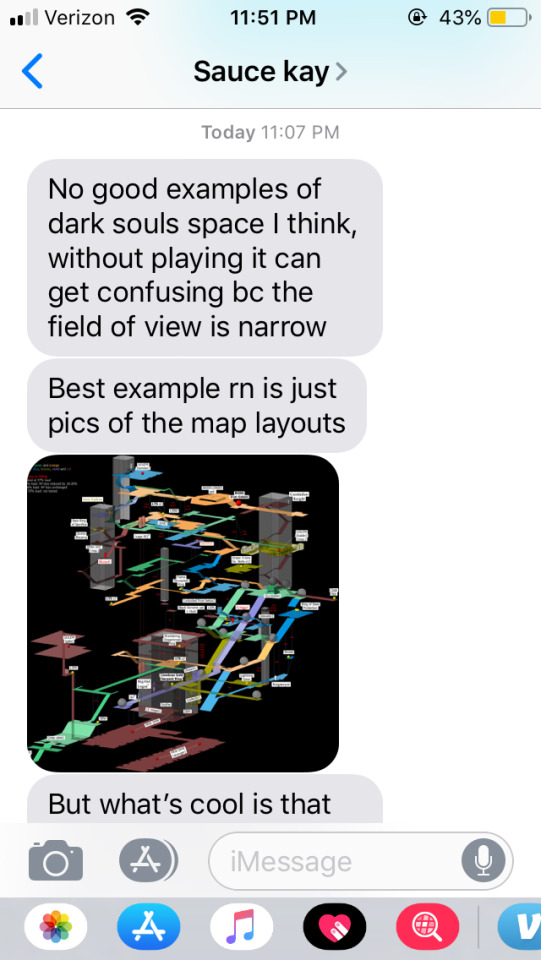

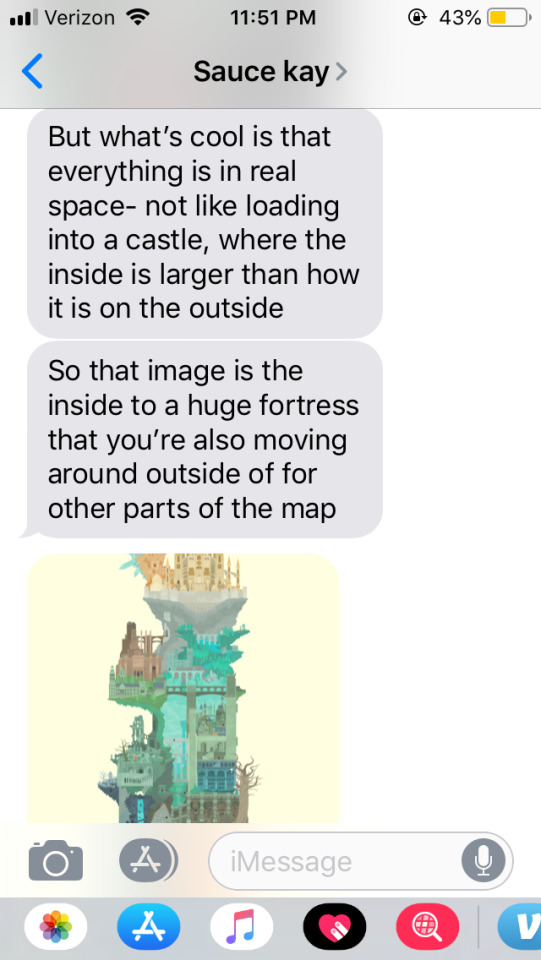

The World Design of Dark Souls

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

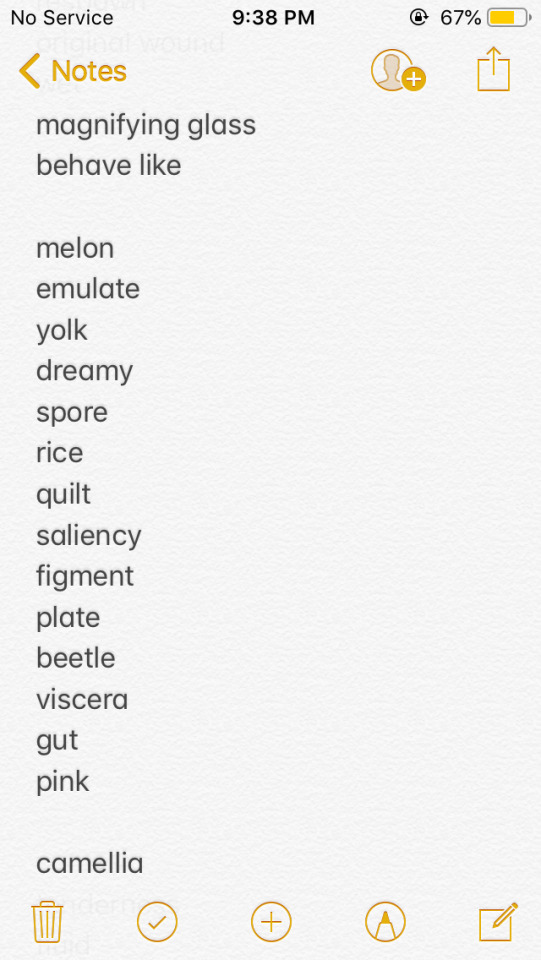

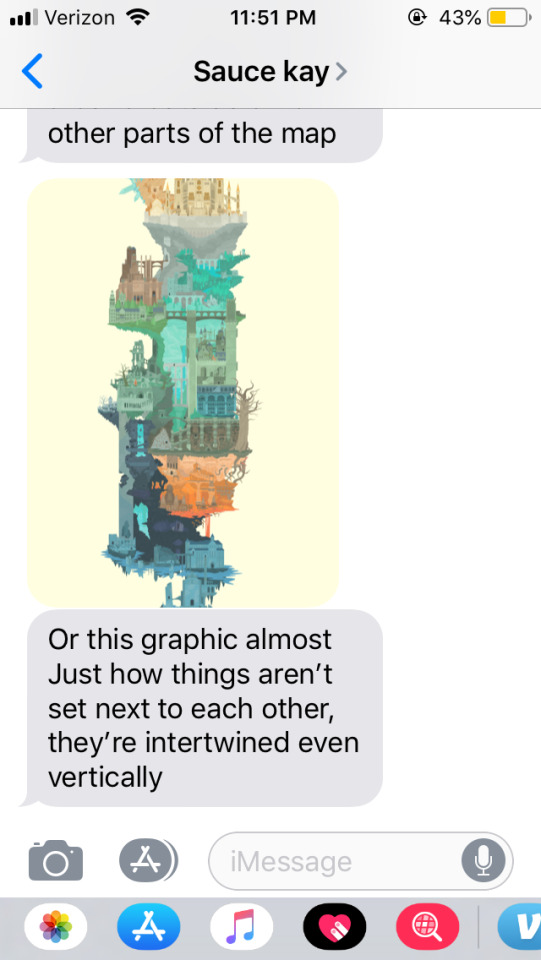

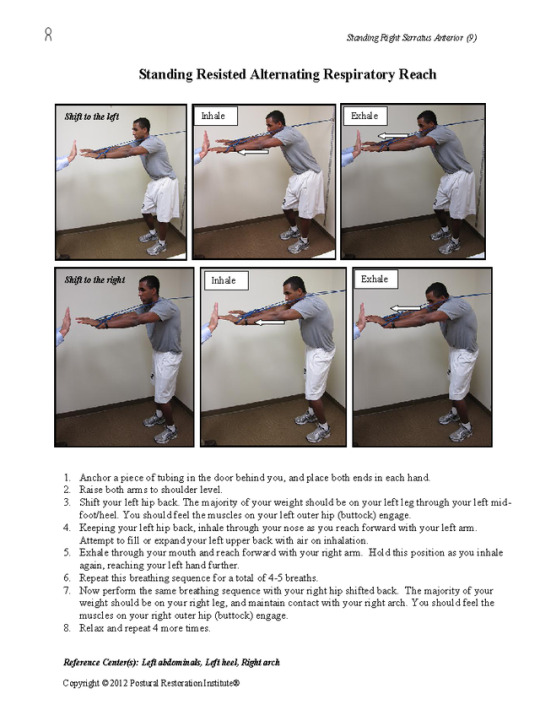

#postural restoration#pri#postural restoration physical therapy#back#stress#chronic pain#computer user#office therapy#tension#seated supported bilateral posterior mediastinum expansion with subcapularis stretch#stretch

0 notes

Photo

#postural restoration#pri#postural restoration physical therapy#pt#chronic pain#back pain#office therapy#computer user#stress#tension#standing resisted alternating respiratory reach#breathing

0 notes

Text

virtual body, performative body, avatar

“Some of the key differences between magnetized (that is, pre-digital) videotape and celluloid film are the quantitative shifts in the following three categories:

1. Memory storage capacity.

Videotape, as a media storage device, holds more temporal information and affords un-interrupted recording.

2. Affordability.

Videotape is less expensive than celluloid film.

3. And mobility.

Video cameras are lighter than film cameras and videotape is more robust in more light conditions then [sic] celluloid film.

That is to say, automatic moving image reproductions were -- with the onset of magnetized videotape in the 1960s -- no longer quite as precious.

This change in the relationship of moving image technology to the representation of time became a point of interest to many artists.

Bruce Nauman, for example -- in a particular series of videos from the late 1960s -- pictures the artist not as one who represents an act of creation, but rather as one who (through the technology’s ability to depict greatly extended units of un-interrupted time) represents creating.

One views Nauman stomp on the ground of his bare artist studio in a rigorous rhythm for approximately 60 minutes.

Or one views him adjust a piece of wood, never quite getting it right, for the same amount of time.

These projects can be read as allegories about creation.

The artist never gets it quite right; every stomp or every movement of the wood is a failure.

What is more important is the evolving process of creation.

In the wake of videotape technology, though, a further series of media storage mutations have come and gone.

The result is the end of material storage devices such as videos or hard drives and the birth of the virtual data cloud -- the immaterial field of code transformed into information signage -- both private as well as public -- hovering in, out, and around one’s physical locations in space.

Each one of these generational mutations, then, has necessitated subsequent mutations in the pictures artists draw of their own body performing actions through time.

Kari Altmann, for example, considers her work to be located not in individual works (as meaningful as they may be) , but rather in her avatar inside the data cloud wherein one views her perform the excavation and molding of her own artistic archive in mutable cloud-space, cloud-time.

Sometimes she’ll just add an image for research or edit an older project; sometimes she’ll list, but not show new projects she’s working on; sometimes she’ll add a new video; sometimes she’ll take a video away; and so on and so on and so on and so on in a plethora of permutations one follows the artist play with her own cloud data:

Change, evolve -- not to “better” data, just different data -- data occurring in an ecological network of additional data networks which are -- as a whole -- growing and becoming self-reflexive, becoming visible to themselves.

The performative focus here, then, is not on the physical body repeating an action, but rather on the virtual body mutating its own archival network.”

McHugh, Gene. Post Internet: Notes on the Internet and Art, 12.29.09 > 09.05.10. “Monday, April 5, 2010.” 110-111.

#Gene McHugh#Post Internet#post-internet#art#internet art#Kari Altmann#12292019#04052010#cloud#avatar#performative#body#virtual body#archive

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Matter and Memory, Of the Survival of Images

(144) We have shown the the objects which surround us represent, in varying degrees, an action which we can accomplish upon things or which we must experience from them. The date of fulfillment of this possible action is indicated by the greater or lesser remoteness of the corresponding object, so that distance in space measure the proximity of a threat or of a promise in time. Thus space furnishes us at once with the diagram of our near future, and, as this future must recede indefinitely, space which symbolizes it has for its property to remain, in its immobility, indefinitely open. Hence the immediate horizon given to our perception appears to us to be necessarily surrounded by a wider circle, existing though unperceived, this circle itself implying yet another outside it and so on, ad infinitum. It is, then, of the essence of our actual perception, inasmuch as it is extended, to be always only a content in relation to a vaster, even an unlimited, experience which contains it; this experience, absent from our consciousness, since it spreads beyond the perceived horizon, nevertheless, appears to be actually given. But while we feel ourselves to be dependent upon these material objects which we thus erect into present real (145) cities, our memories, on the contrary, inasmuch as they are past, as so much dead weight that we carry with us, and by which we prefer to imagine ourselves unencumbered. The same instinct, in virtue of which we open out space indefinitely before us, prompts us to shut off time behind us as it flows. And while reality, in so far as it is extended, appears to us to overpass infinitely the bounds of our perception, in our inner life that alone seems to us to be real which begins with the present moment; the rest is practically abolished. Then, when a memory reappears in consciousness, it produces on us the effect of a ghost whose mysterious apparition must be explained by special causes. In truth, the adherence of this memory to our present condition is exactly comparable to the adherence of perceived objects to those objects which we perceive; and the unconscious plays in each case a similar part.

But we have great difficulty in representing the matter to ourselves in this way because we have fallen into the habit of emphasizing the differences and, on the contrary, of slurring over the resemblances, between the series of objects simultaneously set out in space and that of states successively developed in time. In the first, the terms condition each other in a manner which is entirely determined, so that the appearance of each new term may be foreseen. Thus I know, when I leave my room, what other rooms I shall go through. However, my memories present themselves in an order which is apparently capricious. The order of the representations is then necessary in the one case, contingent in the other; it is this necessity which I hypostatize, as it were, when I speak of the existence of objects outside of all consciousness. If I see no inconvenience in supposing, given the totality of objects which I do not perceive, it is because the strictly determined order of these objects lends to them the appearance of a chain, of which my present perception is only one link. This link communicates its actuality to the rest of the chain. But, if we look at the matter closely, (146) we shall see that our memories form a chain of the same kind, and that our character, always present in all our decisions, is indeed the actual synthesis of all our past states. In this epitomized form our previous psychical life exists for us even more than the external world, of which we never perceive more than a very small part, whereas, on the contrary, we use the whole of our lived experience. It is true that we posses merely a digest of it, and that our former perceptions, considered as distinct individualities, seem to us to have completely disappeared or to appear again only at the bidding of their caprice. But this semblance of complete destruction or of capricious revival is due merely to the fact that actual consciousness accepts at each moment the useful and rejects in the same breath the superfluous. Ever bent upon action, it can only materialize those of our former perceptions which can ally themselves with the present perception to take a share in the final decision. If it is necessary, when I would manifest my will at a given point of space, that my consciousness should go successively through those intermediaries or those obstacles of which the sum constitutes what we call distance in space, so, on the other hand, it is useful, in order to throw light upon this action, that my consciousness should jump the interval of time which separates the actual situation from a former one which resembles it; and as consciousness goes back to the earlier date at a bound, all the intermediate past escapes its hold. The same reasons, then, which cause our perceptions to range themselves in strict continuity in space, cause our memories to be illumined discontinuously in time. We have not, in regard to objects unperceived in space and conscious memories in time, to do with two radically different forms of existence, but the exigencies of action are the inverse in the one case of what they are in the other.

But here we come to the capital problem of existence, a problem we can only glance at, for otherwise it would lead us step by (147) step into the heart of metaphysics. We will merely say that with regard to matters of experience -- which alone concern us here -- existence appears to imply two conditions taken together: (1) presentation in consciousness and (2) the logical or casual connection of that which is so presented with what precedes and with what follows. The reality for us of a psychical state or of a material object consists in the double fact that our consciousness perceives them and that they form part of a series, temporal or spatial, of which the elements determine each other. But these two conditions admit of degrees, and it is conceivable that, though both are necessary, they may unequally fulfilled. Thus, in the case of actual internal states, the connection is less close, and the determination of the present by the past, leaving ample room for contingency, has not the character of a mathematical deviation -- but then, presentation in consciousness is perfect, an actual psychical state yielding the whole of its content in the act itself, whereby we perceive it. On the contrary, if we are dealing with external objects it is the connection which is perfect, since these objects obey necessary laws; but then the other condition, presentation in consciousness, is never more than partially fulfilled, for the material object, just because of the multitude of unperceived elements by which it is linked with all other objects, appears to enfold within itself and to hide behind it infinitely more than it allows to be seen. We ought to say, then, that existence, in the empirical sense of the word, always implies conscious apprehension and regular connection; both at the same time, although in different degrees. But our intellect, of which the function is to establish clear-cut distinctions, does not so understand things. Rather than admit the presence in all cases of the two elements mingled in varying proportions, it prefers to dissociate them, and thus attribute to external objects, on the one hand, and to internal states, on the other hand, two radically difference modes of exis-(148) tence, each characterized by the exclusive presence of the condition which should be regarded as merely preponderating. Then the existence of the psychical states is issued to consist entirely in the apprehension by consciousness, and that of external phenomena, entirely also, in the strict order of their concomitance and their succession. Whence the impossibility of leaving to material objects, existing, but unperceived, the smallest share in consciousness, and to internal unconscious states the smallest share in existence. We have shown, at the beginning of this book, the consequences of the first illusion: it ends by falsifying our representation of matter. The second illusion, complementary to the first, vitiates our conception of mind by casting over the idea of the unconscious an artificial obscurity. The whole of our past psychical life conditions our present state, without being its necessary determinant; whole, also, it reveals itself in our character, although none of its past states manifests itself explicitly in character. Taken together, these two conditions assure to each one of the past psychological states a real, though an unconscious, existence.

But we are so accustomed to reverse, for the sake of action, the real order of things, we are so strongly obsessed by images drawn from space, that we cannot hinder ourselves from asking where memories are stored up. We understand that physics-chemical phenomena take place in the brain, that the brain is in the body, the body in the air which surrounds it, etc.; but the past, once achieved, if it is retained, where is it? To locate it in the cerebral substance, in the state of molecular modification, seems clear and simple enough because then we have a receptacle, actually given, which we have only to open in order to let the latent images flow into consciousness. But if the brain cannot serve such a purpose, in what warehouse shall we store the accumulated images? We forget that the relation of container to content borrows its apparent clearness and universality from the necessity laid (149) upon us of always opening out space in front of us and of always closing duration behind us. Because it has been shown that one thing is within another, the phenomenon of its preservation is not thereby made any clearer. We may even go further: let us admit for a moment that the past survives in the form of a memory stored in the brain; it is then necessary that the brain, in order to preserve the memory, should preserve itself. But the brain, insofar as it is an image extended in space, never occupies more than the present moment: it constitutes, with all the rest of the material universe, an ever-renewed section of universal becoming. Either, then, you must suppose that this universe dies and is born again miraculously at each moment of duration, or you must attribute to it that continuity of existence which you deny to consciousness, and make of its past a reality which endures and is prolonged into its present. So that you have gained nothing by depositing the memories in matter, and you find yourself, on the contrary, compelled to extend to the totality of the states of the material world that complete and independent survival of the past which you have just refused to psychical states. This survival of the past per se forces itself upon philosophers, then, under one form or another; the difficulty that we have in conceiving it comes simply from the fact that we extend to the series of memories, in time, that obligation of containing and being contained which applies only to the collection of bodies instantaneously perceived in space. The fundamental illusion consists in transferring to duration itself, in its continuous flow, the form of the instantaneous sections which we make in it.

But how can the past, which, by hypothesis, has ceased to be, preserve itself? Have we not here a real contradiction? We reply that the question is just whether the past has ceased to exist or whether it has simply ceased to be useful. You define the present in an arbitrary manner as that which is, whereas the present is sim-(150)ply what is being made. Nothing is less than the present moment, if you understand by that the indivisible limit which divides the past from the future. When we think this present is going to be, it exists not yet, and when we think it as existing, it is already past. If, on the other hand, what you are considering is the concrete present such as it is actually lived by consciousness, we may say that this present consists, in large measure, in the immediate past. In the fraction of a second which covers the briefest possible perception of light, billions of vibrations have taken place, of which the first is separated from the last by an interval which is enormously divided. Your perception, however instantaneous, consists then in an incalculable multitude of remembered elements; in truth, every perception is already memory. Practically, we perceive only the past, the pure present being the invisible progress of the past gnawing into the future.

Consciousness, then, illumines, at each moment of time, that immediate part of the past which, impending over the future, seeks to realize and to associate with it. Solely preoccupied in thus determining an undetermined future, consciousness may shed a little of its light on those of our sites, more remote in the past, which can be usefully combined with our present state, that is to say, with our immediate past: the rest remains in the dark. It is in this illuminated part of our history that we remain seated, in virtue of the fundamental law of life, which is a law of action: hence the difficulty we experience in conceiving memories which are preserved in the shadow. Our reluctance to admit the integral survival of the past has its origin, then, in the very bent of our psychical life -- an unfolding of states wherein our interest prompts us to look at that which is unrolling, and not at that which is entirely unrolled.

So we return, after a long digression, to our point of departure. There are, we have said, two memories which are profoundly (151) distinct: the one, fixed in the organism, is nothing else but the complete set of intelligently constructed mechanisms which ensure the appropriate reply to the various possible demands. This memory enables us to adapt ourselves to the present situation; through it the actions to which we are subject prolong themselves into reactions that are sometimes accomplished, sometimes merely nascent, but always more ore less appropriate. Habit rather than memory, it acts our past experience but does not call up its image. The other is the true memory. Coextensive with consciousness, it retains and ranges alongside of each other all our states in the order in which they occur, leaving to each fact its place and, consequently, marking its date, truly moving in the past and not, like the first, in an ever renewed present. But, in marking the profound distinction between these two forms of memory, we have not shown their connecting link. Above the body, with its mechanisms which symbolize the accumulated effort of past actions, the memory which imagines and repeats has been left to hang, as it were, suspended in the void. Now, if it be true that we never perceive anything but our immediate past, if our consciousness of the present is already memory, the two terms which had been separated to begin with cohere closely together. Seen from this new point of view, indeed, our body is nothing but that part of our representation which is ever being born again, the part always present, or rather that which, at each moment, is just past. Itself an image, the body cannot store up images, since it forms a part of the images, and this is why it is a chimerical enterprise to seek to localize past or even present perceptions in the brain: they are not in it; it is the brain that is in them. But this special image which persists in the midst of the others, and which I call my body, constitutes at every moment, as we have said, a section of the universal becoming. It is then the place of passage of the movements received and thrown back, a hyphen, a connecting link between the things which act upon me (152) and the things upon which I act --

#The bodily memory#made up of the sum of the sensori-moto systems organized by habit#is then a quasi-instantaneous memory to which the true memory of the past serves as base

0 notes

Link

Brains of Pokemon trainers

0 notes

Quote

… it only takes two facing mirrors to construct a labyrinth.

Jorge Luis Borges, “Nightmares” from Seven Nights (via heteroglossia)

3K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Their agendas for the last decade. Opinions differ as to the definition of the technical goals to be achieved, the means for reaching them, and the place of humans in a future heavily populated with intelligent agents. Not everyone on the frontlines of robotics research shares Moravec’s optimism about mapping neural structures with sufficient completeness, and migrating consciousness to other media, such as silicon. For instance, Danny Hillis, designer of the world’s fastest computer, the Connection Machine, on the one hand agrees with Moravec and Minsky about the lack of a dividing line between human beings and machines; he holds too that the brain is a kind of computer, and that thought is a complex computation. On the other hand, he (like others) argues, we may never be able to understand and map natural intelligence into a wiring diagram. Nevertheless, for Hillis this ultimate limitation does not imply that we cannot engineer an artificial intelligence eventually superior to human intelligence. He asserts that intelligence is really an emergent phenomenon, a complex behavior that self-organizes as a consequence of billions of tiny local interactions. This conception of intelligence leads him to predict: “We will not engineer an artificial intelligence; rather, we will set up the right conditions under which an intelligence can emerge. The greatest achievement of

our technology may well be the creation of tools that allow us to go beyond engineering – that allow us to create more than we can understand.” Indeed, critics of the disembodied mind are very much at home in the AI community. Fundamentally in agreement with the views of Damasio, Lakoff, and Johnson, While he agrees in principle that it may be possible to computationally simulate the brain, creating a virtual version running on a computer, he sees the problem as getting it to run in a different medium, such as silicon and metal, and this transfer might take a hundred years just to figure out. But while Brooks agrees that humanoid intelligence requires he sees nothing mystical about carbon-based matter: “My own beliefs say that we are machines, and from that I conclude that there is no reason, in principle, that it is not possible to build a machine from silicon and steel that has both genuine emotions and consciousness.” This statement expresses an ideology reinforced by several powerful technical advances in computing over the past decade, rich ideas about the nature of computation, and amazing progress in both biotechnology and nanotechnology. Brook’s view, not only representing those of AI scientists and engineers but also rapidly becoming the view we all silently share, fuses perspectives from computing, communications technology, biotechnology, and nanotech into a powerful new technoscience. In this view, there are only assemblages of machines, whether in the domain of consciousness, intelligence, or other biological and material systems, and these constructions are all to be understood as different forms of computation. According to this view, the world is a collection of machines – indeed, a computer.”

Lenoir, Tim. Makeover: Writing the Body into the Posthuman Technoscape Part One: Embracing the Posthuman. Stanford University. https://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/TimLenoir/Publications/Lenoir_MakeoverIntroPt1.pdf

0 notes