Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Final Assessment

Introduction:

In this essay, I will be exploring how four readings from our class work together and explain the importance of racial representation in the television series Watchmen. These readings are Frantz Fanon, “The Negro and Psychopathology,” which explores the psychological effects of colonialism on Black individuals, highlighting the intricacies of identity formation among Black audiences and the struggle for liberation. The next reading is bell hooks, “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” which focuses on Black women’s experience with misrepresentation in the media and how the oppositional gaze challenges that notion by empowering the Black woman. The next will be Audre Lorde, “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” which delves into the intersections of identity, advocating for the acknowledgment and celebration of diversity among women while challenging systems of oppression. Finally, the last reading I will be using is Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” which explains the cultural hegemony that controls Black culture and places it in the context of Eurocentrism and white supremacy. All of these readings focus on something related to race or gender, and provide context for why TV shows like Watchmen are important to the mainstream media. I will begin by explaining the similarities between all of the sources listed above and then their differences. Then, I will focus on a specific scene from two episodes of the series to show how these terms and this theory can be applied to the current film and television we consume.

Similarities between the readings:

All of the readings focus on the experience Black audiences go through when consuming media and how misrepresentation can have a heavy impact on audiences. Frantz Fanon centers on the Black man’s experience of the world, specifically on how a white-dominant culture alienates Black people. He writes that there is no outlet for catharsis for Black audiences when there is a lack of representation. Due to the lack of catharsis, there are perpetuated feelings of inferiority among Black audiences when they are not adequately represented. He writes: “the world is white because no black voice exists” (1). His “The Negro and the Psychopathology” focuses on the psychological repercussions of Black men being mistreated, stereotyped, and negatively portrayed concerning white people. bell hooks also writes of Black audiences in her essay “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” Specifically, she writes about the experiences of Black women when consuming media. She writes: “Talking with black women of all ages and classes, in different areas of the United States, about their filmic looking relations, I hear again and again ambivalent responses to cinema (...) Most of the black women I talked with were adamant that they never went to the movies expecting to see compelling representation of black femaleness. They were all acutely aware of cinematic racism - its violent erasure of black womanhood” (2). She writes that Black women do not see themselves represented correctly in cinema, resulting in a lack of excitement to see new media. hooks’ claims are similar to Fanon’s because they both claim that stereotyping and misrepresentation impact the audience’s experiences.

Fanon and hooks’ arguments are similar because they both explore how Black voices are absent or misrepresented in cinema, causing Black audiences to feel a sense of ambivalence or negativity towards the media they are consuming. Audre Lorde’s reading “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference” expands on the idea of the Black looking relations between subject and spectator, specifically how the intersection between Blackness and womanhood represented on screen creates a unique viewing experience for Black women. “But Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living …” (3). Lorde further explores the psychological reasoning behind Fanon and Hooks’ explorations of the dissatisfaction of the Black audience with the media. She explains that since Black women’s lives are filled with hatred or the fear of hatred, they are no longer enthusiastic to see misrepresentations of themselves on screen because these representations only add fuel to the fire of racism against Black people.

Finally, Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” explores how Black culture is a site of much contestation since Black voices making art and media necessary to culture must intersect with political, social, and historical forces. “By definition, black popular culture is a contradictory space. It is a sight of strategic contestation. But it can never be simplified or explained in terms of the simple binary oppositions that are still habitually used to map it out (...)” (4). Black popular culture is controlled by Western and Eurocentric dominance, and that influences how Black popular culture is portrayed to mainstream audiences.

Hall’s writings are essential for understanding and fully grasping the ideas of past theorists because he provides historical context to how American society views Black culture. Since authentic Black voices are ignored and placed as inferior to those of European and American society, it is clear why Black audiences are dissatisfied with their portrayal. Specifically, hooks also touches on the history of the “gaze,” and because of the politics of slavery and racialized power relations, Black audiences were not granted the right to “gaze” for entertainment (5). These readings are similar because they focus on the experiences of Black audiences and the cultural context surrounding dissatisfaction or a negative impact on Black audiences who are being misrepresented on screen.

Differences between the readings:

Fanon and Hall differ from the writings of hooks and Lorde because they focus on Black women and how their experiences are unique since they must deal with the intersection of misogyny and racism in film and television while Black men do not. Lorde writes about the gender divide in race or the lack of intersectionality that women of color experience. She writes: “As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (6). This is where writers such as Lorde differentiate their commentary about race from others because she writes of the unique experience that Black women face when attempting to align with womanhood but are excluded from it because of their race.

While hooks also comments on the experience of Black female audiences, she focuses more on the relationship between the body politics in the media and how spectators will reference them in their daily lives. She writes: “Black female spectators have had to develop looking relations within a cinematic context that constructs our presence as absence, that denies the ‘body’ of the black female to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (7). hooks also adds how Black women are using the revolutionary tool of the “oppositional gaze,” defined as a resistance to the white normative gaze driven by Black spectators (8) – empowers viewers and creators to create new radical media that centers the oppositional gaze or the non-white or non-male gaze. hooks references ‘Black British Cinema: Spectatorship and Identity Formation in Territories,’ by Manthia Diawara who identifies the power of the spectator: ‘Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator’ (9). Instead of focusing on the politics of intersectionality like Lorde, hooks hones in on the sexualization and agency that Black women receive when they are in the spotlight of spectatorship and how they combat it with the oppositional gaze. Lorde and hooks are both Black women who wrote about the experience of Black women, while Fanon and Hall were narrower and focused more on Blackness as a whole, specifically Black men. However, Fanon’s theory is unique in its own right. He focuses on the psychopathology of the Black experience and how others’ perceptions of Black people can lead to further harm. Specifically, he writes of how Black people can internalize negative portrayals of race on screen and affect their self-image.

This exploration differs from those of Lorde, hooks, and Hall because it zeroes in on the specific mental repercussions of racism on screen. For example, Fanon writes of the castration of the Black man and how the nudity of Black men is tied to animalistic imagery rather than a sexually desired image - this is because of racist stereotypes of Black men being tied to rape. He writes: “Every intellectual gain requires a loss in sexual potential. The civilized white man retains an irrational longing for unusual eras of sexual license, of orgiastic scenes, of unpunished rapes, of unrepressed incest” (10). Where hooks, Lorde, and Fanon, all touch on the individual's experience, Hall writes of the historical and geopolitical context of excluding Black people from higher culture, specifically the relationship between Western/European narratives and Black narratives. The United States, specifically, prioritizes white stories and places whiteness in the spotlight, which is where the problems of co-opting and tokenization of Black popular culture arise. Hall writes that cultural marginalization is “the result of the cultural politics of difference, of the struggles around difference, of the production of new identities, of the appearance of new subjects on the political and cultural stage” (11). Hall argues that difference itself and the US’s unfamiliarity with Black culture is the reason why it is excluded from the Eurocentric high society. Hall ties in the white experience and their unfamiliarity with the Black experience to show how marginalization can occur when history has always excluded the new, unfamiliar experience of Black culture from the mainstream.

“This Extraordinary Being” Analysis

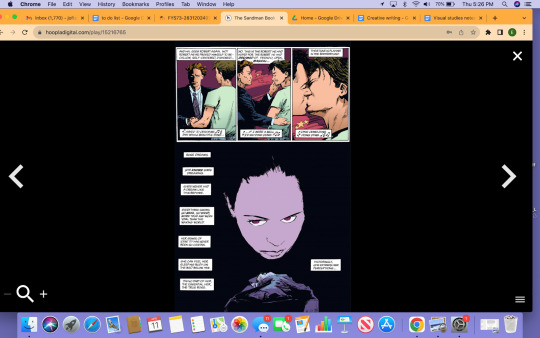

The episode “This Extraordinary Being” from Season One Episode 6 of Watchmen is a fascinating example of how all of these readings come together and are combated through racial representation. In this episode of the series, the main character Angela has taken a lethal dose of Nostalgia, which is a fictional drug that allows her to witness her grandfather’s memories. She is in a trance or coma-like state where she becomes him, and the episode gives audiences a backstory into her grandfather’s past. There are many moments where Angela’s grandfather, Will Reeves, combats racial stereotypes by playing the hero or protagonist of this episode. As a police officer, he fights his racist colleagues and discovers a group called the Cyclops is using hypnotization to turn Black people against each other. In one scene from about minute 27 to about minute 31, Reeves acts as “Hooded Justice” for the first time, wearing a black hood, white face paint over his eyes and a noose around his neck. He breaks into the Cyclops’ secret lair, killing some of the men while they were in discussion. After a fight sequence, a character from the “real world” or Angela’s reality breaks through, attempting to wake her up from this memory.

What is significant about this scene and how it ties into the readings is it does not rely on stereotypes or misrepresentation to showcase a Black character’s strength. Will Reeves’ character’s strength is strong, heroic, and confident, and he does it while killing racists that would be out to get him. Angela’s strength is emotional: she is witnessing the arduous journey fought by her grandfather to fight racists and achieve justice for those the Cyclops were attempting to harm. She carries this legacy as the next generation of Hooded Justice, but this time, she does not have to hide behind the white face paint. Audre Lorde and bell hooks alike would probably connect this powerful representation of a Black woman to how Black women in audiences will resonate and be inspired by Angela’s struggle. Angela’s story is implausible for the average person as she is a superhero. Still, her emotional and personal journey is relatable and connects Black women as carriers of traumatic pasts and also the legacies of those that came before them. Lorde would also add how Angela’s character is a force for societal change, something that she writes about how women must take on these roles because everyone else is separating women or expecting them to separate themselves based on racial, age, sexual, or class differences. hooks may have pointed out how Angela’s character does not depend on her relation to whiteness or her sexuality/desirability, but instead, her space of agency. Angela’s character is a space of agency for Black people, “wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (12).

Fanon’s commentary would probably focus more on the character of Will than Angela, specifically on the strength that the Black male character is portraying and how that would give Black audiences this moment of catharsis or empowerment, positively impacting Black audiences by portraying a positive image. In contrast to Fanon’s writings on the white person’s castration and emasculation of Black men, Will is a strong and confident Black man who is fighting for what he believes in and conquering the racists that are attempting to weaken him. Hall would point out that it is significant that stories of Black persistence and power have such a high platform and wide audience in a series like Watchmen. Considering Hall’s explanation of the displacement of Black culture in comparison to whiteness, it is a serious feat that stories of serious American racism and exclusion are making it into DC Comics and gaining large audiences. While the story of Will and Angela is a story of American history, it is a narrative that the white cultural hegemony would push under the bus or belittle because of ignorance towards the violence towards Black families and communities throughout history. In this story, Will's heroic win over the Cyclops combats Hall’s theoretical readings on white superiority in Western narratives.

“A God Walks Into Abar” Analysis

In the episode “A God Walks Into Abar” from Season One Episode 8 of Watchmen, Angela’s backstory of her relationship is revealed to the audience. This episode focuses on her 10 year love affair with Jon, renamed Calvin to take human form, who is a “God” with supernatural powers. One specific scene that illustrates this episode’s connections to the theoretical readings is the scene between minutes 22 and 25 of the episode. In this scene, Angela and Will are having sex before they get into an argument since Will knows the future, and Angela is upset by his inability to let the future go. He tells her that she will become upset with him which eventually does cause them to get into an argument, Angela telling him to leave. When he does, he goes through a portal to another dimension.

This scene is important for multiple reasons: it is the first time out of the episodes we watched so far where we see Angela and Will’s characters depicted in a sexual light, it is the first fight shown between the pair, and it illustrates the problems in their relationship between a human and the supernatural. In Lorde’s point of view, she may point out how the struggle of human relationships and connection is something that unites all women under all races, ages, classes, and sexual identities. When there are differences, it serves as a tool to understand each other more and learn from each other’s experiences. But, showcasing a common experience for all women but in the light of a not so common relationship illustrates how our differences do not have an impact on the things that unite us as human beings, and that is overcoming inevitable conflict in relationships and understanding each other.

In hooks’ point of view, she may point out the sexual nature of Angela’s character in this scene. For the first time that we have seen in this episode so far, a woman who is strong and a literal superhero is also portrayed as sexual and desirable. This duality of Angela’s character could arguably be a practice of the oppositional gaze: it is a way of portraying a Black woman as more than a one-sided character there to serve as a body but also as a body with agency and power. Something important to mention is the power relations between Angela and Jon - arguably, Angela has more of the power because she is the one that decided for him to look a certain way and he was the one that wanted her first and needed her guidance to become the right type of man for her. This is very subversive to a classic trope of women changing themselves for men, which makes it a powerful thing to see a Black woman deciding what type of man she needs for herself. Fanon may then explore the sexual nature of Jon/Calvin in this scene - going back to his idea of the castration/emasculation of the Black man, Jon is depicted as desirable and confident in this scene. He is extremely intelligent and respectful which subverts racist stereotypes that Fanon writes of Black men being portrayed in an animalistic nature. He also talks with Angela patiently and kindly, even when they are arguing, also combating the stereotypes of violence and aggression that Fanon references. It would be reasonable to believe that Fanon would be satisfied with this representation of a Black man because the character is not relying on any past misconceptions or stereotypes to build character traits and relationships.

Finally, Hall may explore the ideas of representation in postmodern media compared to Watchmen. Watchmen definitely challenges the postmodern tropes that Hall writes about by placing Black people in the center of a narrative instead. Hall writes that in postmodern media, people of color are placed in “palatable” ways for mainstream audiences to easily digest, using people of color as sidekicks or tagalongs to the main, white-centered narrative. Watchmen goes against this idea by making the story of two Black characters its center and even using uncomfortable parts like sex and fights to paint the whole picture of a relationship.

Conclusion:

Watchmen is an example of how gender and race theory can apply to modern-day media even when it may not be trying to. It is important to understand the significance of a Black female lead in a successful television series because it is a rare occurrence that goes against the expectations of our culture. By exploring the two episodes of Watchmen through the readings by Fanon, hooks, Lorde, and Hall, audiences can understand how the series is a rich tapestry of commentary about race, power, and gender relations in this country.

Works cited:

Fanon, Frantz. "The Negro and Psychopathology." Black Skin, White Masks, translated by Charles Lam Markmann, 118. Grove Press, 2008

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 310. (New York: New York University Press, 1999),

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 119. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Hall, Stuart. “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, 469 (London and New York: Routledge, 1996)

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators” 307

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” 112

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Fanon, Frantz. "The Negro and Psychopathology." 127

Hall, Stuart. “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” 470

hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

Analytical Application: Race and Representation

Cultural dominant:

The cultural dominant refers to the social and cultural norms that prevail within a certain group or culture. In Stuart Hall’s “What is ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?”, he writes that it is “impossible to refuse the ‘the global postmodern’ entirely,” stating that in this case, postmodernism has become the cultural dominant, whereas culture in itself is going through a significant shift (1). He goes on to relate this to Black popular culture and that has been created and encoded within the context of popular culture itself.

In the musical number “When I See an Elephant Fly & Dumbo Flies” from the film Dumbo (1941), birds squawking throughout the music video employ jazz and jive like musical style. The style of the music itself is reminiscent of blues and jazz, both genres popularized by the Black community. This is in itself problematic, primarily being that the actors voicing these birds are white and are participating in this “vocal equivalent of blackface” (2). In a Washington Post article, the journalist writes that the original 1941 was “decried as racist” in this past decade in a time of more political correctness and open dialogue about race representation in media. The main bird is named Jim Crow, which references the American cultural dominant: the Jim Crow era. The Jim Crow era is known as a time of racial segregation in the United States, but where it got its name is from a white man playing a caricature of a Black man on stage for entertainment and comedy purposes – the character being named Jim Crow. The main bird in this number is named Jim Crow, participating in the cultural domination of using music and entertainment styles popularized by Black Americans but tokenizing and co-opting their forms of expression for white entertainers and audiences. Additionally, the behavior of the birds – creating them as snarky and villainous – adds to the culturally dominant racist attitudes towards Black people that were explicitly obvious in this era of American history. From the beginning to the end of the musical number, the birds are very obviously caricatures of Black men. But, because making caricatures out of Black men and women was so accepted and adored at the time, it is playing into this cultural dominant.

Cultural hegemony:

Cultural hegemony refers to the dominance or control exerted by one cultural group or ideology over others, influencing societal norms, values, beliefs, and practices. Hall writes that “cultural hegemony is never about pure victory or pure domination,” but instead, “it is always about changing the dispositions and the configurations of cultural power” (3). What this means in context is that there are “cultural strategies” or ways that people utilize tactics to gain power in popular culture. For white people, to gain cultural power could be anything that instills white supremacy and is a way of reminding those on the margins who have the superiority in society.

In The Jungle Book (1967), a young boy befriends animals in the jungle and goes on an adventure. But, through stereotype, The Jungle Book instills this cultural hegemony by participating in negative stereotypes and depictions of Black people using the voices of the monkey characters. By having the monkeys in the film depict voices of Black people, the film relies on a negative trope of Black people being compared to animals, specifically monkeys. In the song “I Wan’na Be Like You,” one of the main monkeys, King Louie, sings to Mowgli, saying how he should feel lucky to be human: “I wanna be like you / I wanna walk like you / Talk like you, too / You'll see it's true / An ape like me / Can learn to be human too” (4). These lyrics could be argued to imply Black characters desire to adhere to popular culture - that the characters representing Black people want to partake in the “human” culture. These lyrics reflect cultural hegemony because there is a certain set of rules that controls a society in this fictional world as well, and everyone wants to be near that power. Unlike the character Jim Crow in Dumbo, King Louie is voiced by a Black actor and musician and he received critical acclaim for his vocal performance of the song in the 1967 film. It is significant that instead of casting a white voice actor for this part, they casted a Black actor, but the role definitely perpetuates who has the power in a society inside and outside the world of the film.

The Orient:

The Orient refers to the Eastern part of the world, specifically the continent of Asia, and even more specifically, parts of Asia that the West finds exotic or mysterious. In Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism,” he writes that “the Orient has helped to define Europe (or the West)” (5) meaning that the Western understanding of Eastern culture helps position Western culture in a certain fashion.

In “Aunt Sarah and Her Twin Siamese Cats” from the 1955 animated Disney film Lady and the Tramp, two siamese cats come to tease and mess with the cocker spaniel, Lady. In the present day, the anti-Asian depictions of the siamese cats has received a lot of backlash, but in the past, these characters were able to exist scot-free. That is possibly because of Said’s explanation of the mystery and intrigue of the Orient and how Western consumers understand it. Western audiences perceive East Asian characters as this sneak and foreign caricature that the siamese cats represent that racist stereotypes perpetuate. Their eyes are slanted and their voices are high and shrill, imitating racist East Asian stereotypes. Said describes this phenomenon of the Western’s negative portrayal of the Orient as the West’s cultural hegemony, relating to the term above (6). With the power that the West has over media depictions, their representations of outside and foreign cultures are not accidental or made up of myth but purposeful, attempting to collect material and social power from its putting down of other cultures. By portraying the Orient relying on only stereotypes, it positions the West in a position of power because it assumes that Western and US characters are the only ones that are worthy of stories.

Orientalist theory:

Orientalist theory is a way of separating the Orient from the Occident through factors such as power structures, creating that feeling of otherness, stereotypes, essentialism, and imperialism. Said asks: “How does Orientalism transmit or reproduce itself from one epoch to another?” (7), questioning how Orientalism is then passed down through generations and how it is instilled into parts of global society.

In “Everybody Wants to be a Cat” from The Aristocats (1970), the musical number shows many different types of cats all singing and dancing together and then cuts to a very racist Asian depiction of a cat playing piano with chopsticks. The cat’s eyes are dramatically slanted and with the symbol of the chopsticks the audiences can tell this is a portrayal of an Asian caricature. These depictions are a possible answer to Said’s question of how Orientalist theory is passed down through generations and how it is so instilled in our global society. By including casual anti-Asian sentiment in media as a way to caricaturize the Orient, the American audiences that The Aristocats was primarily intended for will carry this representation of the Orient into their everyday lives and their understanding of the East. Through Said’s argument, it is evident that this negative representation of the Orient is then translated into how the West views the East and positions themself into a position of power.

Stereotype:

A stereotype is a widely held belief or oversimplified idea about a particular group of people, often based on characteristics such as race, ethnicity, gender, or nationality. Stereotypes usually arise from a lack of understanding the depth of a group of people and making snap judgements about them. As Shohat and Stam wrote in “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation,” “Filmic fictions inevitably bring into play real-life assumptions not only about space and time but also about social and cultural relationships” (8).

Peter Pan (1957) employs racist stereotypes of Indigenous people in their musical number “What Makes a Red Man Red.” First of all, the name “red man” is an outdated name for an Indigenous person that was originally coined as a nickname from an Indigenous person’s appearance, so the name of the song and the language throughout already shows the Indigenous community in a negative light, one that is based solely on appearance instead of character. Secondly, how the film portrays Indigenous people is very problematic and relies on stereotypes. They are portrayed as angry and territorial and Peter Pan and his crew have to dance and partake in their traditions with them even though they seem unenthused. These stereotypes stem from colonialism as white colonizers stole land from Indigenous people, killing them and torturing them for the land. It is very clear that the representation of the Indigenous people from how they were dressed to how they acted was extremely dominated by stereotypes and misunderstandings of Indigenous culture.

WORKS CITED:

(1) Stuart Hall, “What is this ‘black’ in black popular culture?” in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 469

(2) "The original ‘Dumbo’ was decried as racist. Here’s how Tim Burton’s version addresses that." The Washington Post, March 29, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/arts-entertainment/2019/03/29/original-dumbo-was-decried-racist-heres-how-tim-burtons-version-addresses-that/.

(3) Stuart Hall, “What is this ‘black’ in black popular culture?” 471

(4) "The Jungle Book." Directed by Wolfgang Reitherman. Produced by Walt Disney. Burbank, CA: Walt Disney Productions, 1967.

(5) Edward W. Said, Orientalism (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978), 9

(6) Edward W. Said, Orientalism. 14

(7) Edward W. Said, Orientalism. 23

(8) Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, “Stereotype, Realism and the Struggle Over Representation” in Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media” (London: Routledge, 1994), 179

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

In both Said and Shohatt and Stam’s writings, they talk about how race is represented on screen and how white supremacy and Eurocentrism is instilled in everything we watch. Orientalism focuses specifically on the representation of Eastern culture in film and television.

Film/television/popular media sets a standard of orientalism because the media we consume sets a certain standard for what our reality mimics, and when negative portrayals of the Orient is utilized in what we see on the screen it translates into real life. Said describes orientalism as “the corporate institution for dealing with the Orient” (1) which is definitely reflected through the capitalist structures in media that allow orientalism to persist. In the entertainment industry those who make the ultimate decisions of what is successful or not are not placing in mind the potential harm towards “the Orient” because they can profit off of negative stereotypes. Orientalism persists through the media using stereotypes to adhere to white supremacy, or placing Western culture above the “Orient.” The West consciously tries to separate itself from the East through media which intensifies the demonology of “the mysterious Orient.”

Stereotypes are a way that a group of people are lazily represented by adhering to patterns, ways of speech, or common interest as a way to group together an entire marginalized group of people. Stereotypes misrepresent people in film and television because it relies on offensive tropes and does not tell the story of a character. It also is a way that Eurocentrism and white supremacy permeates by “othering” the person who is being stereotyped, instilling a hierarchy. Film and television can change the perception of cultural misrepresentation by identifying the errors in representation. When the use of stereotypes in film and television is debated the topic of “realism” comes into play (2). By authentically portraying marginalized groups and not relying on stereotypes to tell their stories, realistic and authentic stories come into fruition.

Throughout these readings one can see the development of negative stereotypes of race in media, specifically those against the “Orient,” made to look foreign and undesirable to the Western eye.

Works cited:

Edward W. Said, Orientalism (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1978), page 11

Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, “Stereotype, Realism and the Struggle Over Representation” in Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the media” (London: Routledge, 1994), page 178

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 10: Said to Shohat and Stam

To wrap up our studies of visual analysis, Edward W. Said’s “Orientalism” and Ella Shohat and Robert Stam’s “Stereotype, Realism, and the Struggle Over Representation” provide critical paths to understanding the roles of race and representation play in our production and consumption of film, television, and popular culture.

How is orientalism linked to film, television, and popular media, and in what ways has standardization and cultural stereotyping intensified academic and imaginative demonology of “the mysterious Orient” in these mediums?

What role do stereotypes play in the representation of people, and in what ways can film and television change the perception of cultural misrepresentation?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

What examples of “positive images” of marginalized peoples are in film and television, and how can these “positive images” be damaging to and for marginalized communities?

“Positive images” in film and television act as a subversion to stereotypes against marginalized people, a way of rethinking the images associated with marginalized groups. For example In Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film,” he describes the “barely butch” lesbian or a way to represent lesbianism without association to butchness or tomboy-behavior, coding characters with certain dress and behavior (1). Positive images can be damaging to and for marginalized communites by erasing proper representation and keeping things coded. Viewers see this in modern film and television a lot, as characters may be implied to be queer but it is kept a mystery for a more “positive image” or to leave a character’s sexual identity out of their character development. This separating one’s sexuality from their character, while it could be seen as a way to secretly imply queerness in a movie/series, erases representation of authentic and comfortably queer characters on screen.

In what ways is (popular/visual) culture (performance) a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated, and how can cultural strategies make a difference and shift dispositions of power?

Popular and visual culture is a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated because of the global control that colonialism and Eurocentric or Western dominance have over our media we consume. In Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” he writes of the The ambiguities that shift from Europe to America, since it includes America’s ambivalent relationship to European high culture (2). This relationship concerns the nature of the period of cultural globalization in progress now as the US and Europe have a control over global politics which then infiltrates media. For example, in the Academy Awards, a majority of the films in the International Feature category are coming from countries in Europe, a way that the U.S. instills white supremacy in its viewership primarily consuming content from white-centric places. Cultural strategies can make a difference and shift dispositions of power by widening our lens on cultural consumption: highlighting the popular and visual culture of Asian and African countries and shift positions of power in who has a say in the age of global postmodernism.

Works cited:

Jack Halberstam, “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” in Female Masculinity (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998) 217

Stuart Hall, “What is this ‘black’ in black popular culture?” in Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (London and New York: Routledge, 1996), 468

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 9: Halberstam to Hall

Jack Halberstam’s “Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film” and Stuart Hall’s “What is this ‘Black’ in Black Popular Culture?” link our inquiries into gender and sexuality with race and representation.

What examples of “positive images” of marginalized peoples are in film and television, and how can these “positive images” be damaging to and for marginalized communities?

In what ways is (popular/visual) culture (performance) a complicated and political site where various identities are negotiated, and how can cultural strategies make a difference and shift dispositions of power?

@theuncannyprofessoro

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application 5 Gender and Sexuality

Rupture:

Rupture is a disruption or break in established norms, ideologies, or systems, often resulting from resistance or subversion. It creates space for new perspectives and possibilities to emerge, challenging hegemonic structures and fostering social change. Judith Butler says something is ruptured when it is “forced into a rearticulation that calls into question the monotheistic force of its own unilateral operation” (1).

Nada resists Kai’Ckul because he is too powerful for her and kills herself. She resists against what was laid out for her, this “monotheistic force.” Kai’Ckul has a lot of power over her and orders her to become his queen but when she declines, he sends her to hell. Nada’s actions are ruptured because it forces the system she is in to shift, hurting herself as a way of protest. These ruptured actions are similar to other forms of protest where people challenge the norms of the system they are a part of and sometimes put themselves in harm’s way to do so. Another aspect that adds to this rupture is the nudity of Nada in this panel, as she is subverting a classic trope of womanhood – women obeying men – but at the same time she is completely nude. Her nudity is another aspect of rupture because it is a moment of a woman resisting the power of men while also falling victim to the male gaze. The dream lord tells her that he wants nothing else from her besides her love and commitment to him, but Nada still refuses. This could make one think of the classic fairy tale trope and how The Sandman ruptures this idea of fantasy relationships. In the comics, The Sandman exposes real human issues in relationships like violence and betrayal. In the case of Nada and the dream lord, Nada knew she could not stay with him because of his rise to immense power. He then hurt her because she was not obeying him, displaying the patriarchal/male dominance in the relationship between them.

Gender performativity:

Gender performativity is the concept of gender not being a quality that is necessarily inherent but performed through reinforced actions and behaviors. Judith Butler highlights that gender identity is only maintained through social norms: “ (...)which enacts the performative and gestural

conformity to a masculinity which parallels the performative or reiterative

production of femininity in other categories” (2)

In The Sandman, gender performativity is evident between Mr. and Mrs. Sandman (pages 304 and 305). Mrs. Sandman takes the role of the obedient quiet wife, prioritizing motherhood and obedience to her husband. Mr. Sandman on the other hand is the working man of the family, portrayed as a hero when his wife sits idly by. These reiterated norms are an example of Butler’s concept of gender performativity, how it is a way we conform to the “ideal” masculine and feminine purposes in stereotypical traditions and actions. Mrs. Sandman wants to have a baby while Mr. Sandman dreams of bigger goals for his career, reinforcing a “career man” type of stereotype and a maternal feminine stereotype. On page 305 of The Sandman, the author describes Mrs. Sandman as “she has all the dresses she can wear, and a husband who has a very important job.” Mrs. Sandman is performing femininity as she adheres to certain traditional standards for a woman in the home. Additionally, the chapter is called “Playing House,” further emphasizing this idea of these roles are being played into by Mr. and Mrs. Sandman. Even in a fantasy world these characters are performing certain gender practices, adhering to a realistic societal standard.

Gender norms

Gender norms are societal expectations and standards regarding behaviors, roles, and attributes considered appropriate for individuals based on their perceived gender. These norms often reinforce traditional binary understandings of gender and may limit expressions that deviate from these norms. “Identifying with a gender under contemporary regimes of power involves identifying with a set of norms that are and are not realizable, and whose power and status precede the identifications by which they are insistently approximated. This 'being a man'

and this 'being a woman' are internally unstable affairs” (3)

In The Sandman, page 329, and in other panels around this page, women are in this fantastical world but only portrayed as the help. The women in the scene are immediately recognized as inferior in society to the men in this scene because they adhere to these norms. Their power is less because they are only there to serve the male power, asking the men in the tavern if they need help or offering themselves instead of contributing anything else to the scene. Another important factor that shows the women are adhering to gender norms is their dress, as they are in traditional medieval female dress that immediately sets them apart from the male-presenting characters in the scene. Butler points out that some norms are not realizable but that a person’s power and status precede the identifications that go along with gender - even if these women were not dressed in feminine dress or told the reader/spectator that these characters were supposed to be women, their gender norms would lead the audience to still believe that they are women.

Queer gaze is known as a perspective that challenges heteronormative conventions and offers alternative ways of seeing and interpreting visual representations, particularly in relation to gender and sexuality. It celebrates non-conformity and embraces diverse identities and desires. Halberstam ties the queer gaze to cinema as describing its “ample possibilities offered by spectatorship” specifically how showing lesbianism on screen can challenge heteronormativity in media and mainstream society (4). Halberstam 176

In “The Sandman” page 405, the queer gaze does not hone in on lesbian specifically but challenges those heteronormative conventions and offers alternative ways of representing gender and sexuality. A seemingly heterosexual cis male character is seen fantasizing about a kiss with a man - which definitely challenges and subverts expectations about the character’s sexuality/identity. One could argue that by including this moment of fantasy it is illustrating that these characters are multi-dimensional and that is reflective of life. Another important aspect of this is the dreamlike artwork in the kiss - portraying the beauty of the queer gaze and the queer community instead of highlighting the tragedy. The queer gaze in “The Sandman” is a way to appeal to queer characters and add multidimensionality to its characters.

Sex/gender binary

The sex/gender binary is known as the traditional classification system that categorizes individuals into two mutually exclusive and fixed categories based on biological sex (male/female) and gender identity (man/woman). This binary framework often overlooks and marginalizes non-binary and transgender experiences. In Halberstam, he writes that media can often challenge this binary through using sexual identity terms as adjectives instead of nouns (5)

In The Sandman page 437, the character of “Desire” subverts the sex/gender binary. It is unclear what gender identity this character aligns with. The character wears a catsuit and ears, with a short haircut and defines their eyes and lips. Desire is supposed to be “desirable” but does not use any specific gender norms to achieve that desirable look. Desire aligns with Halberstam’s writtings on the sex/gender binary because their character is not defined by their sexuality or gender identity, and it does not take away from their allure. It is purely an adjective for this character that they are looking androgynous while still owning their sexuality and their “desire.”

Works cited:

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999) page 337

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” page 341.

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” 339.

Halberstam, Jack. "Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film." In The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader, edited by Henry Abelove, Michèle Aina Barale, and David M. Halperin, page 176 Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Halberstam, Jack. "Looking Butch: A Rough Guide to Butches on Film." page 178

@theuncannyprofessoro

0 notes

Text

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

Power and privilege impact our personal relationships with each other and institutions because positions in society determine the respect or rights that someone is owed or how institutions treat these positions. For example, Audre Lorde writes of how Black women and Black queer women are on the margins of a structure that is not designed to support them. “Black women know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living …” (1). We can acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization by recognizing that our entire society is built against Black women. It is crucial then, that we recognize differences in experiences and use it as a tool for social change. Lorde writes: “As women, we have been taught either to ignore our differences, or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (2). Women should recognize all forms of oppression - racism, ageism, classism, heterosexism because we have become too used to institutionalized rejection of difference in a profit economy to program responses to human differences.

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

Gender performativity exists through cultural, societal, and media representations by carrying through masculine and feminine stereotypes, the more “norms” we see, the more it sticks with the viewer (3). Gender in media can complicate gender norms by challenging the binary; for example, drag performance, butch-ness, generally traits that belong to one gender identity then being twisted and subverted to challenge expectations. When this occurs, it can point out the simplicity in gender performance – starting to question why we label certain traits with certain gender identities. Heterosexuality is a performance in ways that the simplicity and stupidity of traits that are labeled with a certain identity. Heterosexuality in itself, Butler writes, is an imitation of the classic tropes we have been fed through media and popular culture in everyone’s upbringing (4).

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 119. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." 112.

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” in Feminist Film Theory a Reader (New York: Washington Square, 1999,)

Butler, Judith. “Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion”

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 8: Lorde to Butler

In our continued discussions, Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” and “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” and Judith Butler’s Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion” provide further introspection into systems and definitions of gender and sexuality.

How do power and privilege impact the relations people have with each other and with institutions, and how can we acknowledge, examine, and remedy oppression and marginalization using oppressive and marginalized systems?

How do cultural, societal, and media representations support gender performativity and in so doing complicate gender norms, and in what ways is heterosexuality a performance?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" and "Thot Shit"

youtube

“TELEPHONE” LADY GAGA & BEYONCE

In Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (ft. Beyonce) music video, she centers two women criminals, half of the video taking place at a women's prison and the other half following the homicide the women (played by Gaga and Beyonce) set out to commit. The first striking thing about the video is the immediate use of women’s bodies. All the women in the prison are wearing revealing outfits, even the women security guards. As Gaga walks down the cells, the fellow prisoners (all female-presenting) hoot and holler and as character is thrown into her cell, the guards promptly rip off her clothes. This is an example of the use of a woman’s body that is not centering the male gaze. While a male gaze still may derive pleasure from the revealing costumes in the video, these characters are not necessarily designed to be seen as sexy by the male spectator. In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes that media depictions of women in a patriarchal culture stand as a signifier for the male other - meaning that women characters are present to engage with the male fantasy (1). While most of the women in the music video are partially nude or in revealing costumes, they are not doing so in a sexual nature. Their nudity and sexuality isn’t aiming to please men but to claim their own sexual identity. Mulvey also touches on how women’s bodies in “alternative cinema” can be also a radical or political aspect that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream media, instead of just being objects for pleasure (2). Women’s bodies are shown in “Telephone” in different ways than usual music videos – there is more of a diversity in beauty and a roughness to them – these bodies are asking to be looked at.

In hooks’ “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the “right to gaze.” Specifically, she references: “the politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that the slaves were denied their right to gaze” (3). In these racialized power relations, she writes that Black people were not permitted to engage in the same freedom of watching, entertainment, or deriving pleasure from what they were seeing. This structure ultimately permeates to this day, as hooks writes that of the Black women she spoke to, none were excited to attend the movie theaters, knowing they would not be properly represented (4). How “Telephone” works in contrast with this trend is allowing spectators to look at and derive pleasure from the woman’s body. The idea of the oppositional gaze is a major part of the video because it challenges the ideas of dominant images that women must conform to. The video’s way of resisting the hegemonic gaze was to place the power into the hands of the women characters and for their bodies and strength to be shown without comparing it to that of a male character. hooks references Manthia Diawara to talk about the power of the spectator: “Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator” (4) (309). Each person, specifically women, watching this music video could feel a sense of agency after experiencing women characters having power over their own bodies.

On the topic of bodies, the music video employs a semi-diverse cast of women in the video (the majority of women in the video are still white). Specifically, a lot of the women have stark differences about them like ethnicities, age, or sexual identity. In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes that emphasizing differences is usually taught to be bad or ignored, “or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (5). In “Telephone,” the differences between these women in prison or Beyonce and Gaga as criminals is distinctly outlined. It is unclear with what Gaga and the writers of the video were trying to accomplish with the “outsider-ness” of the characters in the video – if they were trying to make them look bad or powerful –but one could argue that these women could fit into the archetype of rebels, not caring about society’s rules for them, and that would empower the viewer. It could also be argued that these women are represented by a stereotype of women in prison: violent, erratic, and their homosexuality coming off as predatory and creepy. Mulvey references those who have stood “outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference” (6). “Telephone” puts examples in its video of women on the “margins of society,” but their purpose of being there is unclear to the viewer.

Questions:

Do you think that the other women in the video are meant to be powerful or other-ed, just perpetuating a stereotype?

Do you think “Telephone” practices using the “oppositional gaze”?

How do you think the sexual nature of woman characters in the video differs from other media depictions we have seen?

youtube

“THOT SHIT” MEGAN THEE STALLION

At the beginning of the “Thot Shit” music video, the character of the senator is shown leaving a hate comment on one of Megan’s former music videos (“Body”). When he receives a phone call from Megan she tells him “the women that you are trying to step on are the women you depend on. They treat your diseases, they cook your meals, they haul your trash, they drive your ambulances, they guard you while you sleep. They control every part of your life. Do not fuck with them.” This quote is then the theme for the rest of the video. As the senator tries to escape, Megan and her dancers have taken over every occupation and are dancing in his face. Something interesting in this video is the idea of scopophilia that the senator is taking part in. While he is at first closing his blinds and leaving hate comments before gazing, now Megan and her dancers are forcing him to look, owning their image. Mulvey writes about scopophilia in media/cinema, especially tasteful/pleasurable looking (7). While so much of scopophilia in mainstream media is about privacy and what’s “implied,” it could be argued that Megan is subverting the narrative by using her body and her dancers’ bodies freely and without concerns of what is “forbidden.” It could be seen as an act of agency.

hooks herself may argue that “Thot Shit” is an example of Black women having that sense of agency – the Black women throughout the video have multiple careers while also having the freedom of sexuality. She writes: “Spaces of agency exist for Black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (8). This quote encapsulates “Thot Shit” perfectly: a place that Black people can exist freely while also interrogating the gaze of the other. The music video is special because it is a way that Megan celebrates Black women but also the integral part that Black women play in society. They are portrayed as critical parts of a working society but also they dance in the video, owning their sexuality. The sexual nature of the women in the video ties to another example of hooks’ writings about Black women in film/media: the absence “that denies the 'body' of the Black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (9). hooks writes that too often Black women have been denied ownership and agency over their own bodies, but also the ability to be desired by white phallocentric audiences. By using the character of the senator, they show the inherent racism imposed against Black women - people criticize them but then still sexualize them. Something important to mention is Megan’s lyricism in this song - the word “thot” was coined in the hip-hop world as a derogatory term for a woman, similar to the word “slut,” “with added derision for being working class” (10) (WaPo article). The reclamation of this term is outright powerful because it is using a word that has been weaponized against Black women for years and she repurposes it to be something powerful. This subversion in itself can be tied to the work of the oppositional gaze - taking something used to oppress Black women and flipping it to empower them instead.

Rarely in popular media as big as “Thot Shit” do viewers see something with such a clear message. Megan does include a lot of Black female empowerment throughout her music and music videos, especially through sexual agency. Lorde writes, “Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living … ” (11). “Thot Shit” is a form of protesting against the dehumanization and oppression of Black women in mainstream culture. Megan consistently brings Black women into the cultural conversation when they are neglected. Her empowerment is similar to that Lorde writes of: “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (12).

Questions:

What are other ways that “Thot Shit” practices scopophilia and voyeurism in nuanced ways?

How is the video different from other music videos you have seen before?

How does “Thot Shit” work in conjunction with “Telephone”?

Works cited:

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism, 712. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 712

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 307. (New York: New York University Press, 1999)

hooks, bell “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 112. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” (112)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

O’Neal, Lonnae, “I had a thot but didn’t know it was a thing” The Washington Post, March 19, 2015

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 119

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” (112)

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Panel Presentation: "Telephone" and "Thot Shit"

youtube

“TELEPHONE” LADY GAGA & BEYONCE

In Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” (ft. Beyonce) music video, she centers two women criminals, half of the video taking place at a women's prison and the other half following the homicide the women (played by Gaga and Beyonce) set out to commit. The first striking thing about the video is the immediate use of women’s bodies. All the women in the prison are wearing revealing outfits, even the women security guards. As Gaga walks down the cells, the fellow prisoners (all female-presenting) hoot and holler and as character is thrown into her cell, the guards promptly rip off her clothes. This is an example of the use of a woman’s body that is not centering the male gaze. While a male gaze still may derive pleasure from the revealing costumes in the video, these characters are not necessarily designed to be seen as sexy by the male spectator. In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes that media depictions of women in a patriarchal culture stand as a signifier for the male other - meaning that women characters are present to engage with the male fantasy (1). While most of the women in the music video are partially nude or in revealing costumes, they are not doing so in a sexual nature. Their nudity and sexuality isn’t aiming to please men but to claim their own sexual identity. Mulvey also touches on how women’s bodies in “alternative cinema” can be also a radical or political aspect that challenges the basic assumptions of mainstream media, instead of just being objects for pleasure (2). Women’s bodies are shown in “Telephone” in different ways than usual music videos – there is more of a diversity in beauty and a roughness to them – these bodies are asking to be looked at.

In hooks’ “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the “right to gaze.” Specifically, she references: “the politics of slavery, of racialized power relations, were such that the slaves were denied their right to gaze” (3). In these racialized power relations, she writes that Black people were not permitted to engage in the same freedom of watching, entertainment, or deriving pleasure from what they were seeing. This structure ultimately permeates to this day, as hooks writes that of the Black women she spoke to, none were excited to attend the movie theaters, knowing they would not be properly represented (4). How “Telephone” works in contrast with this trend is allowing spectators to look at and derive pleasure from the woman’s body. The idea of the oppositional gaze is a major part of the video because it challenges the ideas of dominant images that women must conform to. The video’s way of resisting the hegemonic gaze was to place the power into the hands of the women characters and for their bodies and strength to be shown without comparing it to that of a male character. hooks references Manthia Diawara to talk about the power of the spectator: “Every narration places the spectator in a position of agency; and race, class and sexual relations influence the way in which this subjecthood is filled by the spectator” (4) (309). Each person, specifically women, watching this music video could feel a sense of agency after experiencing women characters having power over their own bodies.

On the topic of bodies, the music video employs a semi-diverse cast of women in the video (the majority of women in the video are still white). Specifically, a lot of the women have stark differences about them like ethnicities, age, or sexual identity. In Audre Lorde’s “Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” she writes that emphasizing differences is usually taught to be bad or ignored, “or to view them as causes for separation and suspicion rather than as forces for change” (5). In “Telephone,” the differences between these women in prison or Beyonce and Gaga as criminals is distinctly outlined. It is unclear with what Gaga and the writers of the video were trying to accomplish with the “outsider-ness” of the characters in the video – if they were trying to make them look bad or powerful –but one could argue that these women could fit into the archetype of rebels, not caring about society’s rules for them, and that would empower the viewer. It could also be argued that these women are represented by a stereotype of women in prison: violent, erratic, and their homosexuality coming off as predatory and creepy. Mulvey references those who have stood “outside the circle of this society’s definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference” (6). “Telephone” puts examples in its video of women on the “margins of society,” but their purpose of being there is unclear to the viewer.

Questions:

Do you think that the other women in the video are meant to be powerful or other-ed, just perpetuating a stereotype?

Do you think “Telephone” practices using the “oppositional gaze”?

How do you think the sexual nature of woman characters in the video differs from other media depictions we have seen?

youtube

“THOT SHIT” MEGAN THEE STALLION

At the beginning of the “Thot Shit” music video, the character of the senator is shown leaving a hate comment on one of Megan’s former music videos (“Body”). When he receives a phone call from Megan she tells him “the women that you are trying to step on are the women you depend on. They treat your diseases, they cook your meals, they haul your trash, they drive your ambulances, they guard you while you sleep. They control every part of your life. Do not fuck with them.” This quote is then the theme for the rest of the video. As the senator tries to escape, Megan and her dancers have taken over every occupation and are dancing in his face. Something interesting in this video is the idea of scopophilia that the senator is taking part in. While he is at first closing his blinds and leaving hate comments before gazing, now Megan and her dancers are forcing him to look, owning their image. Mulvey writes about scopophilia in media/cinema, especially tasteful/pleasurable looking (7). While so much of scopophilia in mainstream media is about privacy and what’s “implied,” it could be argued that Megan is subverting the narrative by using her body and her dancers’ bodies freely and without concerns of what is “forbidden.” It could be seen as an act of agency.

hooks herself may argue that “Thot Shit” is an example of Black women having that sense of agency – the Black women throughout the video have multiple careers while also having the freedom of sexuality. She writes: “Spaces of agency exist for Black people, wherein we can both interrogate the gaze of the Other but also look back, and at one another, naming what we see” (8). This quote encapsulates “Thot Shit” perfectly: a place that Black people can exist freely while also interrogating the gaze of the other. The music video is special because it is a way that Megan celebrates Black women but also the integral part that Black women play in society. They are portrayed as critical parts of a working society but also they dance in the video, owning their sexuality. The sexual nature of the women in the video ties to another example of hooks’ writings about Black women in film/media: the absence “that denies the 'body' of the Black female so as to perpetuate white supremacy and with it a phallocentric spectatorship where the woman to be looked at and desired is ‘white’” (9). hooks writes that too often Black women have been denied ownership and agency over their own bodies, but also the ability to be desired by white phallocentric audiences. By using the character of the senator, they show the inherent racism imposed against Black women - people criticize them but then still sexualize them. Something important to mention is Megan’s lyricism in this song - the word “thot” was coined in the hip-hop world as a derogatory term for a woman, similar to the word “slut,” “with added derision for being working class” (10). The reclamation of this term is outright powerful because it is using a word that has been weaponized against Black women for years and she repurposes it to be something powerful. This subversion in itself can be tied to the work of the oppositional gaze - taking something used to oppress Black women and flipping it to empower them instead.

Rarely in popular media as big as “Thot Shit” do viewers see something with such a clear message. Megan does include a lot of Black female empowerment throughout her music and music videos, especially through sexual agency. Lorde writes, “Black women and our children know the fabric of our lives is stitched with violence and with hatred, that there is no rest. We do not deal with it only on the picket lines, or in dark midnight alleys, or in the places where we dare to verbalize our resistance. For us, increasingly, violence weaves through the daily tissues of our living … ” (11). “Thot Shit” is a form of protesting against the dehumanization and oppression of Black women in mainstream culture. Megan consistently brings Black women into the cultural conversation when they are neglected. Her empowerment is similar to that Lorde writes of: “It is learning how to stand alone, unpopular and sometimes reviled, and how to make common cause with those others identified as outside the structures in order to define and seek a world in which we can all flourish” (12).

Questions:

What are other ways that “Thot Shit” practices scopophilia and voyeurism in nuanced ways?

How is the video different from other music videos you have seen before?

How does “Thot Shit” work in conjunction with “Telephone”?

Works cited:

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism, 712. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 712

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory, 307. (New York: New York University Press, 1999)

hooks, bell “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

Lorde, Audre. "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference." In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, 112. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007

Lorde, Audre “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference.” (112)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 308

hooks, bell, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” 310

O’Neal, Lonnae, “I had a thot but didn’t know it was a thing” The Washington Post, March 19, 2015

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” 119

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” (112)

@theuncannyprofessoro

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” she writes about the use of women in media and how it is stereotypically a vehicle for manipulating the aesthetics of a woman’s appearance for profit (1). A woman’s representation on screen is controlled by the “male gaze,” a phrase she utilizes to explain throughout the text how everything that we consume is controlled by a patriarchal ideology. Without realizing, we all take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze, regardless of race or sexuality. Since entertainment is so controlled and manufactured by this male gaze, it manipulates the majority of what the rest of the world consumes. Through classic narratives and genres like fantasy princesses, an action-packed hero’s journey, or horror, all are delivered through a narrow lens designed to satisfy that male gaze – one specific example: Die Hard (1988).

In bell hooks’s “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” she writes about the experiences of Black women when consuming media. She writes:“Talking with black women of all ages and classes, in different areas of the United States, about their filmic looking relations, I hear again and again ambivalent responses to cinema. (...) Most of the black women I talked with were adamant that they never went to the movies expecting to see compelling representation of black femaleness” (2). One could interpret this as Black women not seeing themselves properly represented in cinema resulting in a lack of excitement to see new media. This is a prime example of how racial and sexual differences between viewers can differentiate their experience. In contrast, the “oppositional gaze” – defined as a resistance to the white normative gaze driven by Black spectators (3) – empowers viewers and creators to create new radical media that centers the oppositional gaze or the non-white or non-male gaze.

Works cited:

Laura Mulvey, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” in Film Theory and Criticism (New York: oxford University Press, 2009)

bell hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators” in Feminist Film Theory (New York: New York University Press, 1999), 119

hooks, “The Oppositional gaze: Black Female Spectators”

@theuncannyprofessoro

Reading Notes 7: Mulvey to hooks

Shifting our visual analysis and critical inquiries to gender and sexuality, we will begin our explorations with Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” and bell hooks’s “Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.”

How does the spectacle of the female image relate to patriarchal ideology, and in what ways do all viewers, regardless of race or sexuality, take pleasure in films that are designed to satisfy the male gaze?

How do racial and sexual differences between viewers inform their experience of viewing pleasure, and in what ways does the oppositional gaze empower viewers?

@theuncannyprofessoro

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Analytical Application Psychoanalysis/Subjectivity

Uncanny: Sigmund Freud describes the “uncanny” as a feeling of eeriness, caused by something that feels familiar but makes the viewer uncomfortable. That uncanny feeling occurs when the boundaries between what is real and imagined become confusing, usually causing discomfort, (1). The uncanny often arises through places, sounds, or feelings that cause a strange dreadful sensation in the viewer.

In “Squeeze,” season 1 episode 3 of “X-Files,” uncanniness permeates throughout the entire episode but is extremely apparent in the first few minutes of the episode before the opening sequence (0:00-3:22). Immediately the viewer sees a victim being followed through the eyes of someone or something out to get him. This is made clear by suspenseful music, sneaky shots, and dark lighting. Every move he makes is clearly being watched through someone else’s eyes, and the cinematic elements add to this uncanny feeling. That anxious sensation is proven correct when the man is murdered and we see very little except a tear in the wall of the door, a blood stain, the screws on a vent turning, and a collapsed mug. Showing these few images is purposeful to make sure the audience understands that someone murdered him but to not understand why and feel scared yet intrigued, making the viewer want to keep watching.

Mirror stage: Jacques Lacan defines the “mirror stage” as a phase in development between the ages of six and eighteen (2). A phase described by a sense of anxiety and loneliness, the mirror stage is when a child’s sense of self is inconsistent so they identify themself through a mirror before looking inward for psychoanalysis.

One interesting example of the mirror stage in “Squeeze” is the bone-chilling last shot of the episode, showing the serial killer Eugene Victor Tooms sitting in the cell by himself, looking through the open slot of the cell (41:59). Alone in a confined space, one could argue that Tooms’ mental illness (possibly psychopathic tendencies) that is causing him to be a serial killer would be analyzed. But, through his creepy smile, it is apparent that he has other plans, not to engage in psychoanalysis. Even if this is true, the confinement of a mentally ill man could be compared to a child’s mirror stage - this is forcing a sense of realization and identification. While Tooms’ confinement could backfire, solitary confinement is usually a way for criminals to live without distractions, separating them from society and analyzing their behavior.

Collective catharsis: Frantz Fanon’s “The Negro and Psychopathology” explores how collective catharsis is extremely important for marginalized groups to overcome psychological trauma. He writes that in every society there must be some sort of release of collective aggression and emotion to be released (3). Collective catharsis is the release of emotion within a community that has a shared hardship usually related to oppressive forces.

An example of collective catharsis in the episode is when Tooms is handcuffed to the bathtub after attempting to murder Agent Dana Scully in her home (39:01). After a long episode of the agents trying to catch Tooms or at least attempt to figure out who the killer was, and then watching his attempted murder of Dana, this surety of protection (for now) is a moment where Dana and Agent Fox Mulder both can take a sigh of relief that they have solved the case. It is assumed that all the characters besides the antagonist in the episode are experiencing collective catharsis because they finally have this moment of feeling protected from this oppressive force or danger that had been haunting them and the public for a long time.