Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

MAGA - Msg for US Veterans by Jason Lewis

The Path to Prosperity: Veteran Entrepreneurship Resources Entrepreneurship offers a unique opportunity for veterans to apply their exceptional skills and discipline in a new arena. The transition from military service to business ownership can be both rewarding and challenging. However, numerous dedicated resources exist to support veterans in this endeavor, ensuring they are well-equipped to navigate the complexities of starting and growing their own businesses. This guide from the European Center of Military History highlights essential avenues for support, offering insights into how veterans can leverage these resources to build successful enterprises.

Finding Funding For veteran business owners looking to secure funding, there are numerous grant opportunities available through organizations like The StreetShares Foundation and Warrior Rising. However, to tap into these resources, you must actively apply for the funding they offer. It's crucial to prepare a thorough business plan before submitting your application. This document will not only strengthen your application but also clarify your business strategy, making it easier for these organizations to understand and support your venture. The SBA's Role in Veteran Entrepreneurship The Small Business Administration (SBA) is a cornerstone for veterans stepping into the business world. By providing access to funding, education, and mentorship, the SBA ensures that veterans have the necessary tools to succeed. Their programs are specifically designed to address the unique challenges faced by veteran entrepreneurs, offering a supportive foundation from which to launch and expand their businesses. Navigating the Veterans Entrepreneur Portal The Veterans Entrepreneur Portal (VEP) is an invaluable resource for those seeking to finance their business ventures. It simplifies the search for veteran-specific grants and funding opportunities, serving as a comprehensive gateway to financial support. The portal's user-friendly interface makes it easier for veteran entrepreneurs to find and apply for the resources most relevant to their business needs, ensuring they have the capital necessary to thrive.

How the OVBD Supports Veterans The Office of Veterans Business Development (OVBD) stands as a cornerstone for veteran entrepreneurs, delivering comprehensive support via training, counseling, and mentorship specifically tailored to meet the needs of the veteran business community. These initiatives are meticulously crafted to encourage both growth and sustainability, creating an environment where veteran-owned businesses can thrive. By facilitating connections with seasoned mentors and offering continuous educational opportunities, the OVBD significantly contributes to the success and flourishing of these businesses, underscoring its vital role in the ecosystem of veteran entrepreneurship.

Embracing Digital Document Management In the digital age, the ability to manage documents efficiently is crucial for any business. For veteran entrepreneurs, digitizing important documents and saving them as PDFs offers several advantages, including enhanced security and easier access. Moreover, mobile apps that scan documents and convert them to PDF format can streamline operations, allowing for more effective organization and management of critical business information.

The Benefits of Joining NaVOBA The National Veteran-Owned Business Association (NaVOBA) fosters a sense of community among veteran entrepreneurs. By connecting members with networking opportunities, exclusive events, and advocacy support, NaVOBA enhances the entrepreneurial journey for veterans. This association is instrumental in promoting the growth and visibility of veteran-owned businesses, encouraging collaboration and mutual support among its members.

Engaging with the Veterans Entrepreneurship Program The Veterans Entrepreneurship Program (VEP) offers a groundbreaking journey that arms veterans with crucial knowledge and skills essential for triumph in the business realm. Engaging in rigorous training and hands-on exercises, veterans acquire a profound comprehension of the intricacies involved in steering through the business landscape. More than just preparing veterans to tackle the hurdles of entrepreneurship, the VEP instills a robust sense of confidence and stimulates a spirit of innovation, thereby setting the stage for their success and enabling them to leave a mark in the world of business.

Leveraging IVMF Resources The Institute for Veterans and Military Families (IVMF) is dedicated to the success of veteran and military family-owned businesses. Offering comprehensive programs that include education, mentorship, and community engagement, the IVMF ensures veterans have access to a wide range of support services. This holistic approach helps veteran entrepreneurs achieve their business objectives while contributing to their overall well-being. Veteran entrepreneurs possess the drive, discipline, and leadership skills necessary to succeed in the business world. By taking advantage of the wealth of resources designed specifically for them, veterans can overcome the unique challenges they face and build thriving businesses. From financial support and digital tools to community networks and educational programs, the avenues for support are both vast and varied. Armed with these resources, veterans are well-positioned to turn their entrepreneurial dreams into reality, contributing significantly to our economy and society. Explore the depths of military history at the European Center of Military History. Dive into our extensive archives and uncover the stories that shaped our world. Best, Jason Lewis Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Veterans: Iwo to Korea, from Vietnam to Iraq then back to Civilian Life (Jason Lewis)

The Path to Prosperity: Veteran Entrepreneurship Resources Entrepreneurship offers a unique opportunity for veterans to apply their exceptional skills and discipline in a new arena. The transition from military service to business ownership can be both rewarding and challenging. However, numerous dedicated resources exist to support veterans in this endeavor, ensuring they are well-equipped to navigate the complexities of starting and growing their own businesses. This guide published by the Read the full article

#5thUSMCRegt#7thUSMCRegiment#Afghanistan#CaptJackieMunn#ChineseCommunist#ChosinReservoir#ForwardOperatingBaseSalerno#Funding#GenDavidPetraeus#InstituteforVeteransandMilitaryFamilies(IVMF)#Iraq#IwoJima#JasonLewis#Kandahār#KhirbetAmmu#KhostProvince#KoreanWar#NationalVeteran-OwnedBusinessAssociation(NaVOBA)#PaktīkāProvince#QamishliCity#RussianRifle#SBARole#SmallBusinessAdministration#StreetSharesFoundation#Syria#VeteranEntrepreneurship#VeteransBusinessDevelopment(OVBD)#VeteransEntrepreneurPortal(VEP)#VietCong#Vietnam

0 notes

Text

7-AD – Withdrawal Behind the 82-A/B Lines December 1944

Document Source: (AAR) After Action Report (December 1944), Headquarters 7th Armored Division, December 1, 1944, – December 31, 1944, St-Vith & Vicinity, Belgium, Col John L. Ryan Jr, GSC, Chief of Staff

FOREWORD

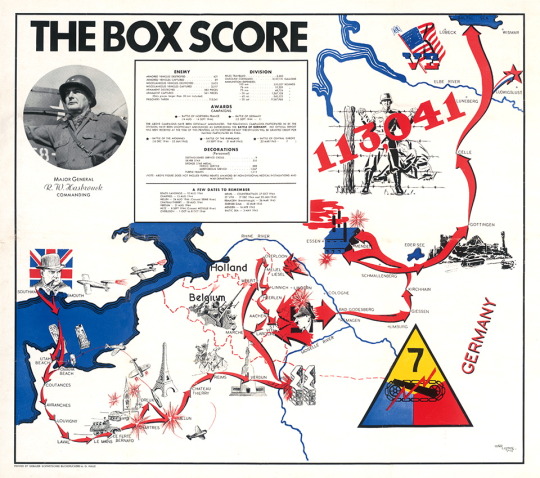

The 7th Armored Division was activated on March 1, 1942, reorganized on September 20, 1943, and sent to the United Kingdom in June 1944. The division landed in Omaha Beach and Utah Beach, on August 13/14, 1944, and was assigned to the US 3-A. The 7-AD drove through Nogent-le-Rotrou in an attack on Chartres which fell on August 18. From Chartres, the Division advanced to liberate Dreux, then Melun where the division crossed the Seine River on August 24. The 7-AD then pushed on to bypass Reims, liberated Château-Thierry and Verdun, August 31, halted briefly for refueling until September 6, when it drove toward the Moselle River and made a crossing near Dornot. This crossing had to be withdrawn in the face of the heavy fortifications around Metz.

The 7-AD then made attempts to cross again the Moselle River northwest of Metz but the deep river valley was not suitable terrain for an armored attack. Elements of the division assisted the 5th Infantry Division in expanding a bridgehead east of Arnaville, south of Metz, and on September 15, the main part of the division crossed the Moselle. The 7-AD was repulsed in its attacks across the Seille River at and near Sillegny, part of an attack in conjunction with the 5-ID that was also repulsed further north. On September 25, the 7-AD was transferred to the US 9-A and began the march

to the Netherlands where they were needed to protect the right (east) flank of the corridor opened by Operation Market Garden. They were to operate in southeastern Holland so that British and Canadian forces and the US 104th Infantry Division could clear the Germans from the Scheldt Estuary in the southwest Netherlands and open the shipping lanes to the critical port of Antwerp, to allow Allied ships to bring supplies from Britain.

In September 1944, the 7-AD launched an attack from the north on the town of Overloon, against significant German defenses. The attacks progressed slowly and finally settled into a series of counter-attacks reminiscent of World War I trench warfare. On October 8, the 7-AD was relieved from the attack on Overloon by the British 11-AD and moved south of Overloon to the Deurne – Weert area. Here they were attached to the British 2-A and ordered to make demonstration attacks to the east, in order to divert enemy forces from the Overloon and Venlo areas, where British troops pressed the attack. This plan succeeded, and the British were finally able to liberate Overloon. On October 27, the main part of the 7-AD was in essentially defensive positions along the line Nederweert (and south) – Meijel – Liesel, with the demonstration force still in the attack across the Deurne Canal to the east. The Germans launched a two-division offensive centered on Meijel, catching the thinly stretched US 87-CRS (Cavalry Recon Squadron) by surprise. However, the response by the 7-AD and by the British VIII Corps to which the division was attached, stopped the German attack on the third day and from October 31 to November 8, gradually drove the enemy out of the terrain that they had taken. During this operation, at midnight on the night of October 31 – November 1, Gen Robert D. Hasbrouck replaced Gen Lindsay Silvester as Commanding General of the division. On November 8, the 7-AD was again transferred back to the US 9-A and moved south to rest areas in the eastern vicinity of Maastricht. Following an inflow of many replacements, they began extensive training and reorganization, since so many original men had been lost in France and Holland that a significant part of the division was now men who had never trained together. At the end of November, the division straddled the Dutch-German Border with one combat command in Germany (in the area of Ubach–Palenberg, north of Aachen) and two in the Netherlands. Elements of the division were attached to the US 84th Infantry Division for operations in early December in the area of Linnich, Germany, on the banks of the Roer River.

DECEMBER 1, 1944 On December 1, the division order of battle was as follows: CCA – 48th Armored Infantry Battalion – Able Co, 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion – Dog Co, 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron Mecz CCB – 23rd Armored Infantry Battalion – 31st Tank Battalion – Baker Co, 33rd Armored Infantry Battalion – Baker Co, 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron Mecz – Dog Co, 203rd AAA Battalion – Charlie Co, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – 1st Plat, Baker Co, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – 1st Plat, Recon, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion CCR – 38th Armored Infantry Battalion – Baker Co, 40th Tank Battalion – Charlie Co, 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion – Ordnance Detachment – Medical Detachment Division Troops – 203rd AAA Battalion (-) – 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion (-) – 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion (-) – 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron Mecz Division Trains – 129th Ordnance Maintenance Company (-) – 77th Armored Medical Battalion (-) – 446th Quartermaster Truck Company (-) – 3967th Quartermaster Troop Transport Company (-) – Baker Co, 203rd AAA Battalion Division Artillery was under XIII Corps control and consisted of: – 434th Armored Field Artillery Battalion – 440th Armored Field Artillery Battalion – 489th Armored Field Artillery Battalion – Able Co and Charlie Co, 203rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion Attached to the division were the: – 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – 203rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion – 446th Quartermaster Trucking Company – 3967th Quartermaster Troop Transport Company Detached from the division were the: – 17th Tank Battalion (attached to the 102-ID) – 40th Tank Battalion (-) Baker & Dog Cos (attached to the 84-ID)

(CCR/7-AD), commanded by Col John L. Ryan Jr, was in the vicinity of Ubach, Germany, on December 1, 1944. The only divisional unit in action under division command was Baker Co 40th Tank Battalion which was supporting the 84th Infantry Division's operations in the vicinity

of Lindern. Able Co 40-TB was holding Lindern with elements of the 84-ID. Baker Co 40-TB was sent in to reinforce it. Due to enemy artillery concentrations on the supply route, supplies were brought to the two companies by means of the Blue Ball Express, an innovation using the light tanks of Dog Co 40-TB to bring up trailer loads of rations and ammunition under the cover of darkness.

(CCB/7-AD) under the command of Col Bruce C. Clarke, was alerted to move east of the Wurm River, Germany, to assemble at Gereonsweiller. The mission was to attack southeast from Lindern and to seize Linnich by passing through the 84-ID and 102-ID. The 814-TDB was to support the attack. However, due to the progress of the infantry divisions, it was not necessary

to commit CCB. (CCA/7-AD) under Col Dwight A. Rosenbaum, located in the vicinity of Heerlen, Holland, was undergoing a training and maintenance program pending operations to the east.

DECEMBER 2, 1944

The Division Tactical Headquarters was established at Rimburg, Holland. CCB 7-AD moved east of the Wurm River. This placed two combat commands east of that river, prepared for immediate operations to the east, northeast, or north. At 0115, the elements of the 40-TB which had been attached to the US 84-ID were relieved from such attachment. Baker 40-TB was then attached to the US 84-ID. While prepared to repel any enemy counter-attacks, the division units continued with training and maintenance programs.

DECEMBER 3, 1944

At 1200, the 17-TB was relieved from attachment to the US 102-ID and returned to CCR 7-AD control. Proposed operations to the east were dependent upon the destruction of the enemy-held Roer River Dams, south of Düren. The enemy was capable of countering an Allied offensive in this area by flooding the Roer River Valley. This would result in either destruction of the troops in the flooded region or the cutting off of our supply lines. To eliminate this threat, Allied air forces made

several attempts to destroy the dam by bombing. The first attempt was made on December 3. While training and maintenance continued for the division as a whole, various divisional units were in action while under attachment to other commands. Baker Co 40-TB was attached to the US 84-ID from December 2, 1944, at 2230 to December 6, 1944, at 1600. Charlie Co 38-AIB

was also under attachment to the US 84-ID from December 3, 1944, at 2100 to December 6, 1944, at 1800. The 48-AIB was attached to the US 102-ID from December 5, 1944, at 1400 to December 9, 1944, at 2400 and the 17-TB was attached to the US 84-ID from December 9, 1944, at 1400 until December 16, 1944, at 2000.

During the period, detailed plans were made for seizing the town of Brachelen. The town was defended by the German 694.Infantry-Regiment, the 695.Infantry-Regiment and the 696.Infantry-Regiment from the 340.Infantry-Division. The attack was dependent upon the destruction of the Roer River Dams which would isolate the town. When one of the dams was broken it would take from 4 to 5 1/2 hours for the crest of the flood to reach Brachelen, and as the dam could not be bombed before 1000, the attack was to be launched the day after the destruction of the dam. CCB 7-AD was assigned the job of taking Brachelen. The plan of attack was outlined in Operations Instructions on December 11, at 0900, known as plan Dagger. CCA 7-AD was to move east of the Wurm River after CCB’s attack. Both combat commands were constituted as follows: CCA – 40th Tank Battalion – 48th Armored Infantry Battalion – Able Co, 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion – Dog Co, 87th Cavalry Rcn Squadron (Mecz) – Able Co, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – 1st Co, Recon, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – Detachment, 77th Armored Medical Battalion CCB – 23rd Armored Infantry Battalion – 31st Tank Battalion – 38th Armored Infantry Battalion – Baker Co, 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion – Baker Co, 87th Cavalry Recon Squadron (Mecz) – Charlie Co, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – 1st Plat, Baker Co, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – Detachment, 129th Ordnance Battalion – Dog Co, 203rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion – Detachment, 77th Armored Medical Battalion CCR – 1 Squadron Recon, 814th Tank Destroyer Battalion – Charlie Co, 33rd Armored Engineer Battalion

DECEMBER 10 Today, Col Bruce C. Clarke, Commanding CCB 7-AD, was promoted to brigadier general. At 1000, CCB 7-AD was placed in the Corps reserve. DECEMBER 11 At 1500, CCB was released from the Corps Reserve and replaced by CCA 7-AD. DECEMBER 13 Division Main Headquarters moved from Robroek to Heerlen, Holland, while the rest of the division continued training and maintenance, pending the destruction of the Roer River dam and the beginning of the operations Dagger. DECEMBER 16

Read the full article

#104thInfantryDivision#23rdArmoredInfantryBattalion#3-A(US)#38thArmoredInfantryBattalion#40thTankBattalion#422ndInfantryRegiment#423rdInfantryRegiment#424thInfantryRegiment#48thArmoredInfantryBattalion#5thInfantryDivision#7thArmoredDivision#811thTankDestroyerBattalion#814thTankDestroyerBattalion#84thInfantryDivision#87thCavalryReconSquadron#Aachen#Antwerp#Arnaville#Aywaille#Bastogne#Beho#Born#Bovigny#Braunlauf#BritishForces#CanadianForces#CCB-7-AD#Chartres#ChateauThierry(France)#Cherain

0 notes

Text

1/422/106-ID - Forced March (Mohn) The Fate of the American POWs of the 106-ID)

Source Document: Forced March Major John P. Mohn, HQ Co, 1st Battalion, 422nd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division

Forced March, from Schoenberg - St Vith (Battle of the Bulge, Belgium) to Berchtesgaden in Germany, is the Prisoner of War memoir of the 1200-mile forced march done by Maj John J. Mohn, Hq Co, 1st Battalion, 442nd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division, Golden Lion and has been extracted from a book published in Canton, Ohio, USA and printed by PPi Graphics, also in Canton Ohio, (ISBN-13:978-08-9863465-5-2). Being a friend of Mandy Altimus Pond, Maj John J. Mohn's granddaughter, we talked about the publishing of this book on the EUCMH Website and agreed that this work would be a great way to render honor to Maj John J. Mohn and the terrible period he experienced while being one American Prisoner of War in Nazi Germany during the last year of WW-2. Before starting with the text, I would like the reader to notice that combat photos from a surrendered unit in the combat zone don't exist, especially with the 422 and the 423-IRs of the 106-ID. On the morning of Dec 16, 1944, these two infantry regiments, were trapped between two German main axes of penetration; on their front, elements of the 5.Panzer-Army (Manteufeul) coming from Blieaf in Germany and heading to St Vith and on their rear, elements of the 6.Panzer-Army (Dietrich) coming from Lanzerath and Manderfeld heading to Liège via St Vith, didn't give a one of a chance to these two Regimental Combat Teams (422 and 423) which once cut off, without supply, couldn't withdraw in any direction. These men combated up to the last cartridge, then destroyed all their guns, machine guns, and rifles, and finally surrendered. Dedication To my wonderful wife, Cheri, and loving daughter, Debora Mohn Altimus; without whose prodding and encouragement this book would never have been written. And to my son-in-law Richard Altimus who assisted in the computer editing of this book. Editor's Note: Additional thanks to my granddaughter, Mandy Altimus Pond, who helped me with the publishing of her grandpa's book. Maj John J. Mohn, 1/442-IR, 106-ID

Foreword When WW II's Battle of the Bulge began with a surprise German attack on Dec 16, 1944, troops of the US 106th Infantry Division occupied the most exposed American positions. They had been in the European continent for less than two weeks and cut off from reinforcements, were left to face the German onslaught alone. They fought back, standing their ground, but as their ammunition; food and medical supplies dwindled and the enemy noose drew tighter, over 7000 were ordered by their commanding officers to surrender to the surrounding German forces. Except for the Bataan Death March, this was the largest surrender of American troops during WW II. Maj Mohn, of Akron, Ohio, the author of this book, was the Operations Officer of the 1/422-IR. He was a citizen-soldier who had volunteered to join the Army as a private in 1941. This is the story of his 1200-mile odyssey as a prisoner of war to the far reaches of the Nazi empire during which he and his fellow soldiers were starved, frozen, bombed, and shot. Because the Germans were unprepared to absorb a massive influx of American POWs and had little space to house them, Maj Mohn's imprisonment became an almost continuous five-month march through the collapsing and chaotic Third Reich. Initially, he was sent to a camp for American officers over 500 miles away from Poland. He

arrived there only to be marched out of the camp a few days later when the Russian forces broke through the German lines around Warsaw. Seeing the prisoners as a potential bargaining chip and intent on keeping them out of Russian hands, the Germans forced the Americans to make a harrowing march westward across rural Poland and Germany in the dead of winter just ahead of pursuing Soviet forces. After this month-and-a-half ordeal, the prisoners finally arrived at the Hammelburg POW Camp in northern Bavaria, only about 100 miles away from where they started. Two weeks later this camp was attacked and briefly captured by a Task Force of Patton's 3-A. The Germans, however, soon recaptured the camp and immediately sent Maj Mohn and the other prisoners on another dangerous march which ended at the Austrian border five weeks later they were liberated by American troops. Through it all, Maj Mohn preserved and returned to the USA where he underwent treatment and rehabilitation for injuries he had suffered as a prisoner of war. he returned to civilian life and developed a highly successful career as a psychologist. But his remarkable experiences in the military never quite left him. Eventually, he put words to paper and the result is the archive you are about to read - one of the very few accounts of this type ever to have been published. More than just a narrative of his experiences as a POW in Nazi Germany, it is a testament to the indomitable spirit of the US soldiers and a reminder to all of us of the sacrifices they made to preserve our freedom. Before the Battle of the Bulge - Mandy Altimus Pond

About 1937, while attending Akron University, John Mohn took Reserve Officers' Training Corps. John had no desire to become an officer, but by the end of his training, he had reached the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. In preparation for what appeared to be an inevitable world conflict, Congress passed the Selective Service Act in 1940. This was the first peacetime conscription in US history. Enacted in September 1940, this act required men between 21 and 35 years of age to register with local draft boards. Men were drafted by a lottery system and were required to serve for twelve months. After that year was completed, John was told he would be draft-free and not required to sign up, should a war arise. On Feb 4, 1941, John decided to enlist for this program and join the Navy. He drove to Cleveland, entered the Armory, and began the process. He took the written test, passed the physical, and was about to be sworn in when the commanding officer at the Armory said that John's teeth protruded too much and they would not accept him. John stated in an interview that 'this is stupid' and went to the other end of the Armory and enlisted in the Army. At this moment he could have enlisted as a 2nd Lieutenant because of his ROTC training. It slipped his mind and he enlisted as a Private.

John was assigned to the 37-ID at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. He volunteered for the Signal Company (Teletype) and the day after he signed up, the teletype was discontinued, so he was reassigned to supply in the Signal Company and was sent to Indiantown Gap Pa. On Dec 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the next day upon request from President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Congress declared war on Japan and their ally Germany. This canceled the draft-free status that John had signed up for, as he had not completed his twelve months of training. His division was scheduled to board a ship headed to the Pacific Theater of the war, but the boat blew up before they could head out.

John was then sent to Fort Benning, Georgia, for officer training from February through April 1942. In late 1942, he was sent to Camp Forest and assigned to the 80-ID for a year. He became CO Fox Co, 1/319-IR, 80-ID. His division was in charge of clearing trees in the mountains in preparation for war games, training men in firing artillery, and surviving in realistic battle situations. John was in charge of the logistics and planning for the war games.

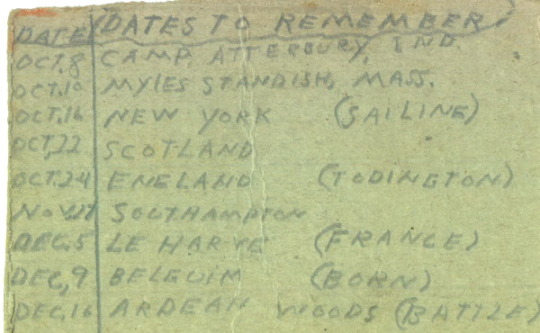

The 80-ID was then incorporated into the 106-ID. John was reassigned as Bn OP Officer and sent to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, and assigned to Hq Co, 1/422-IR, 106-ID. John reached the rank of Captain and was told that he was the youngest Captain in the Division. As Operations Officer, he was in charge of logistics for troop movements. He staged a large 3000-troop parade in Indianapolis in 1944. After our advance movement order was in, we received new equipment, turned in motor vehicles, and did what training we could at odd intervals. Finally, in September we moved by rail to Camp Myles Standish at Taunton, Mass. This place was known as a staging area where life reached the maximum of not letting anyone know anything at all. We existed on a monotonous routine of rumors until the day we redoubled our tracks, returned to New York, boarded the RMS Aquitania, and departed for Gourock, Scotland, on Oct 21, 1944. The 423-IR with various attached units arrived Oct 27, and the 422 and 424-IRs arrived Oct 28 with the artillery and some special units. We moved then to England where we were deployed in one of the most interesting and certainly the most beautiful parts of this country, the Cotswold section of the midlands. The 422-IR was stationed some 12 miles west and northwest of Oxford, the 424-IR near Banbury of Banbury Cross fame, and the 423-IR, and the Division Artillery near Cheltenham and Gloucester respectively. Division headquarters and special units were located centrally in this 200-square-mile area.

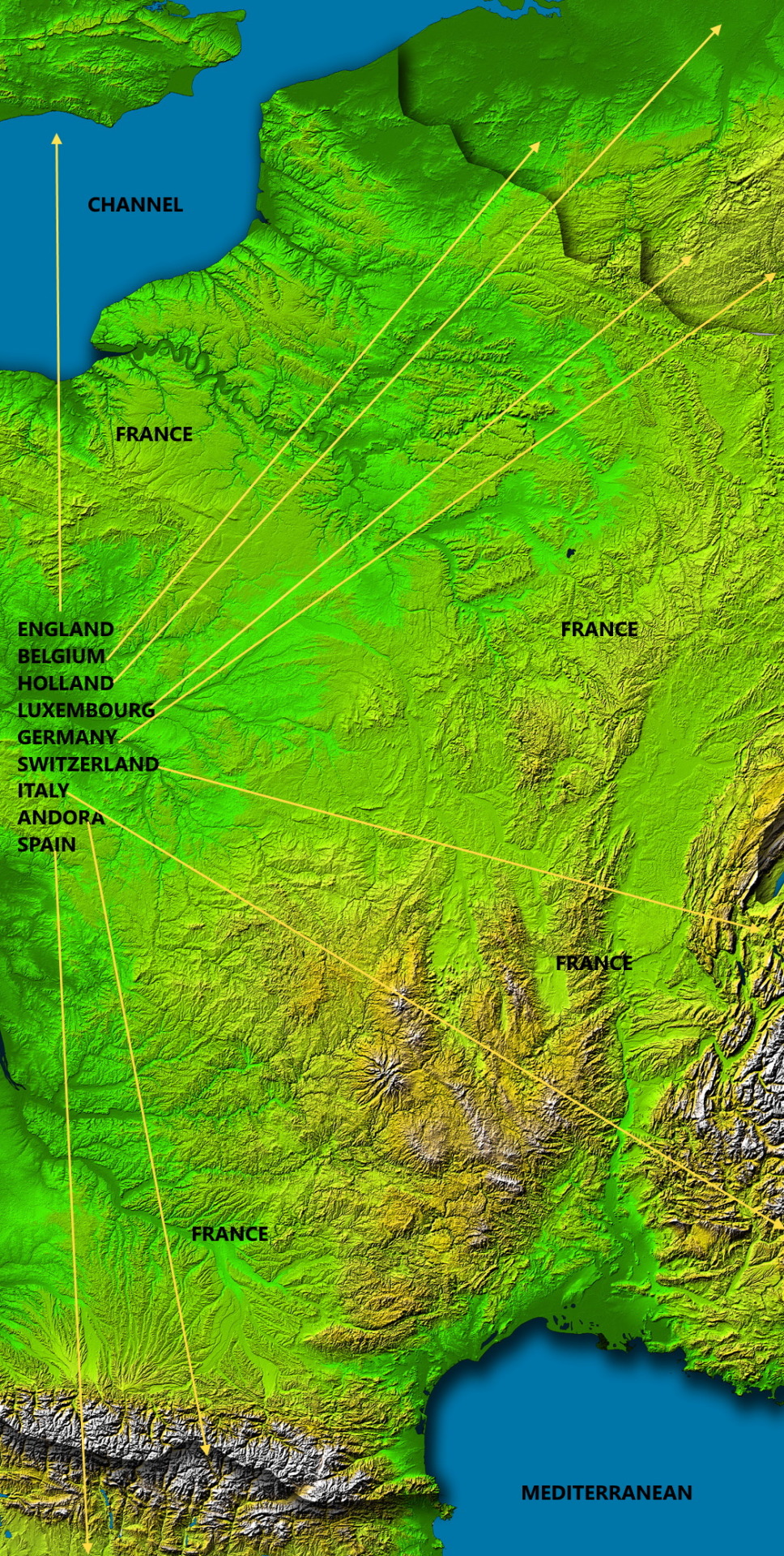

We remained in England preparing for an expected early crossing of the Channel. Between Nov 30 and Dec 1, the Golden Lions embarked on the long slow fifty-mile trip from Southampton to cross the Channel. We disembarked at Le Havre and at Rouen, a town about one-third of the way up the Seine toward Paris, and went into a bivouac in deep mud in the open fields in a cold drizzling rain, between the Dec 1/8.

During these days liaison officers from the 1-A headquarters arrived at odd intervals with conflicting and inconsistent sets of orders, so that during 48 hours we were assigned to three different corps in as many separate locations. Fortunately, troops and staff were arriving in unrelated groups as the weather and the Navy allowed them ashore so that no damage was done except to my disposition. The final messenger appeared on Dec 6 with instructions for us to leave for the St Vith area in Belgium. The first combat team to move, left the area on Dec 8, followed by the others as rapidly as possible. Upon arrival, we were to relieve the 2-ID, then in a defensive position, as part of the VIII Corps whose headquarters was then at Bastogne. Troops being in the throes of landing after a rough winter crossing, staffs only partly present and maps few and far between, our move to the battlefield was a rather remarkable one and highly successful despite its discomfort. The route carried us nearly 300 miles through Amiens, Cambrai, and Maubeuge in France to Philippeville in Belgium. After an overnight bivouac in extra deep mud near the latter town, we passed through Marche and the villages of eastern Belgium to the vicinity of St Vith, arriving during the period Dec 9/15. The relief of the 2-ID's weary troops stationed along the quiet German border in the Belgian Ardennes Forest commenced on Dec 11, and was completed on Dec 13, responsibility for the defense of the sector passing to me on Dec 12. The troops of the Indian head Division assured the men of the Golden Lion Division that there would be little action on this hilly terrain in the middle of winter. Edward P. McHugh

Preface - Maj John J. Mohn It was Dec 16, 1944, somewhere along the Siegfried Line near St Vith, Belgium. The German counter-attack that would later be referred to as the Battle of the Bulge had begun. The gray, foggy dawn made a perfect umbrella for the German launching of an onslaught that nearly cost the Allies World War Two. What happened at the Battle of the Bulge may be a well-known story but none of the stories make any reference to the group of American Soldiers taken prisoner at that time and marched for 140 continuous days covering over 1200 long, cold, starvation-ridden, nightmare miles, terminated only by the end of the war in Europe. Adversity is a mild term to describe the unbearable hardships endured by the ever-changing, ever-diminishing column of men. Temperatures dropped to ten degrees below zero (22°F). There were periods of fifteen days without a single bite of food. All suffered a phenomenal loss of weight (I weighed 65 pounds by the time of the liberation). We had inadequate clothing; many were without hats or gloves and at times no shoes. It was especially brutal for the poor Army Air Corpsmen who were only wearing thermal boots with no soles for walking when they were shot down and captured. The journey was marked by frozen feet, legs, arms, faces, and even blood trails. Treachery, deceit, and fear are just feeble attempts to put into words the anger, horror, anguish, and despair felt by these military men.

The ordeal that the approximately 7000 US soldiers endured between Dec 16/44 and May 2/45 can only be epitomized by saying that a scant thirty of the original group even reached liberation as a unit. Losses of men beyond belief resulted from attempts at escape, exposure, starvation, the sadism of the German Guards, and being strafed daily by our own and Allied planes. My book is not intended as a condemnation of the German People or Army but does make reference to differing attitudes and treatment by the Wehrmacht, to whom I owe a debt of gratitude for being alive, and the Elite SS Troops, who were constantly threatening our lives with attempts to exterminate us with machine guns and failed to provide even the most basic of necessities for our daily maintenance. The German High Command seemed at a loss as to what to do with so many prisoners and lacked a plan regarding the disposition of us. The result was a wandering march covering three countries with no apparent purpose, with a final goal of holding us as hostages in Berchtesgaden at the end of the war. The consequences for us, as Prisoners of War, were painfully clear. The facts and sequences of events I know first-hand because I was there from the beginning to the end. I saw dramatic changes in attitudes, values, behavior, and beliefs. Hidden strengths and weaknesses in the struggle for survival were surprising and at times frightening, but the salient factor through it all was that survival is 'All-Important' and that the 'Veneer of Civilization' is extremely thin.

December 16, the Horror Begins I couldn't help being reminded of that famous poem by Rudyard Kipling 'The Charge of the Light Brigade' on that fateful, foggy, grey, cold, drizzling morning Dec 16, 1944. The difference was that instead of 'cannons' noted in the poem, we had German tanks to the left of us, tanks to the right of us, tanks in front of us, and tanks behind us. To 'charge' ahead would have been to go down the steep slope of an evergreen-covered mountain. The landscape was so much like the mountain areas of Pennsylvania that it was hard to remember that we were in a foreign country fighting a very serious war. Even more seriously, we were surrounded and annihilated by German Panzer Divisions from the left and right of us. German artillery from the front was terrible enough but, to our dismay, the Germans had captured our artillery and were using our guns to fire upon us from the rear. When we called for supporting fire, they were aiming at us instead of their troops. Our Battalion Commander, Col Thomas Kent was killed by a shell coming in from the rear of our 'Pillbox' command post. At first, we thought our artillerymen were firing short of their target, but when we heard the German voice on our radio, we realized the awful truth - we were literally at their mercy. The divide-and-conquer strategy used in the German attack had been completely unexpected and effective. Read the full article

#106thInfantryDivision#28thInfantryDivision#2ndInfantryDivision#3-A(US)#422ndInfantryRegiment#5.PA(German)#6.Panzer-Army#80-ID(US)#9-AD(US)#Afron#BalticSea#BataanDeathMarch#BattleoftheBulge#Belgium#Berchtesgaden#Bleialf(Germany)#CampMylesStandish#CampShelby#DeboraMohnAltimus#December1944#EdwardP.McHugh#Falkenberg#Fatherland#FortBenning#GenAllanW.Jones#GenevaConvention#Germany#HammelburgPWCamp#HQsCo1/422#IndiantownGap

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

442-RCT's The Rescue of the Lost Battalion (Watanabe)

Document Source: A thesis presented to the Faculty of the US Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Military Art and Science, Military History, by Maj Nathan K. Watanabe, USA B.S., US Air Force Academy, Colorado, 1988, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2002 (Doc Snafu Final Check September 12, 2022)

Introduction

The 442nd Infantry Regiment, later 442nd Regimental Combat Team, was an infantry regiment of the United States Army and was the only infantry formation in the Army Reserve. The regiment is best known for its history as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-generation American soldiers of Japanese ancestry (Nisei) who fought in World War II. Beginning in 1944, the regiment fought primarily in the European Theatre, particularly in Italy, southern France, and Germany. The story of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team (442-RCT) is rooted in the history of the Japanese in Hawaii and America itself. As the second generation of Japanese born abroad or the first Japanese generation born in Hawaii and America through the early 1910s and 1920s, the Nisei were American citizens and part of the larger greatest generation to be of the right age to face the conflict of World War II. This generation of Japanese born abroad best personifies the blending of American and Japanese cultures that laid the foundation for a resolute, cohesive, and dedicated unit that accomplished every assigned mission without fail.

The 442nd Regiment is the most decorated unit in the US military history. Created as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team when it was activated on February 1, 1943, the unit quickly grew to its fighting complement of 4000 men by April 1943, and an eventual total of about 14.000 men served overall. The unit earned more than 18.000 awards in less than two years, including 9.486 Purple Hearts and 4.000 Bronze Star Medals. The unit was awarded eight Presidential Unit Citations (five earned in one month). Twenty-one of its members were awarded Medals of Honor. In 2010, the Congressional Gold Medal was awarded to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and associated units who served during World War II, and in 2012, all surviving members were made chevaliers of the French Légion d'Honneur for their actions contributing to the liberation of France and their heroic rescue of the Lost Battalion.

Arriving in the European Theatre, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, with its three infantry battalions, one artillery battalion, and associated HQ and service companies were attached to the 34th Infantry Division. On 11 June 1944, near Civitavecchia, Italy, the existing 100th Infantry Battalion, another all-Nisei fighting unit that had already been in combat since September 1943, was transferred from the 133rd Infantry Regiment to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Because of its combat record, the 100th was allowed to keep its original designation, with the 442nd renaming its 1st Infantry Battalion as its 100th Infantry Battalion. The related 522nd Field Artillery Battalion liberated at least one of the satellite labor camps of Dachau concentration camp and saved survivors of a death march near Waakirchen.

The 442nd saw heavy combat during World War II and was not inactivated until 1946, only to be reactivated as a reserve unit in 1947 and garrisoned at Fort Shafter, Hawaii. The 442nd lives on through the 100th Battalion/442nd Infantry Regiment, which has maintained alignment with the active 25th Infantry Division since a reorganization in 1972. This alignment has resulted in the 100th/442nd Infantry Regiment's mobilization for combat duty in the Vietnam War and the Iraq War, in which the unit was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation. With the 100th/442nd Infantry Regiment the last infantry unit in the Army Reserve, the 442nd's current members carry on the honors and traditions of the historical unit.

Last Voyage of the Inakawa-Maru - 1806 The first known arrival of Japanese to the Kingdom of Hawaii came on May 5, 1806, involving survivors of the ill-fated ship Inawaka-maru who had been adrift aboard their disabled ship for more than seventy days. The Inawaka-maru, a small cargo ship built in 1798 in Osaka, was owned by MansukeMotoya of Kitaniura, Hiroshima, and was chartered by the Kikkawa fiefdom in Iwakuni, a district in the present Yamaguchi prefecture, to transport floor mats and horse feed to the residence of the Kikkawalord in Edo (Tokyo today). The trip began in November 1805. The ship was manned by Capt Niinaya Ginzo, thirty-three years old; Master Ichiko Sadagoro, fifty-three; and four sailors: Hirahara Zenmatsu, thirty-four; Akazaki Matsujiro, thirty-four; Yumori Kasoji, thirty-one, all from Kitaniura; and Wasazo, twenty-seven, from Higashinomura. The ship departed from Kitaniura, Hiroshima, on November 7, 1805, and took on its designated cargo together with two officials of the Kikkawa fiefdom at Iwakuni. Before leaving for Edo, however, the ship returned to Kitaniura and then headed for Edo on November 27, 1805. On December 21, 1805, the Inawaka-maru arrived in Shinagawa, a port in Edo. After unloading the cargo headed southward stopping at Kanagawa, Uraga, and Shimoda. On January 6, 1806, the vessel departed Shimoda for its final homebound voyage.

While crossing the Sea of Enshunada near the Shizuoka prefecture, the Inawaka-maru encountered a snowstorm backed by a strong east wind. The snowstorm turned into heavy rain, and the wind became stronger. The ship was soon disabled and was blown toward the Eastern Pacific. On January 7, 1806, due to the increased force of the wind, the crew cut the mast down, and the disabled ship began drifting further eastward. On January 11, two rocky islets were sighted, but a decision was made not to make a landing. The ship continued drifting eastward. The supply of water ran out on January 20. Except for relief during an occasional rainfall, the crew often went without water for four or five days. Rainwater was collected by every means possible. At times they had to quench their thirst by sucking on cloth that contained some moisture. By February 28, the supplies of rice and water were nearly exhausted. The last dinner was cooked with the last little supply of rice. They all prepared for death, hoping that their ship would take them to their Buddhist paradise. On March 15, a flying fish jumped into the ship. Zenmatsu made a soup with it and shared it with the rest of the crew. They made hand-made hooks and used the innards of the flying fish to catch more fish. In this way, they were able to regain their strength. Some fish were saved by drying.

On March 20, 1806, a foreign ship appeared. The crew of the Inawaka-maru climbed onto the deckhouse roof and signaled the ship by waving a mat and shouting for help. At first, they seemed not to have been seen, but finally, the ship came closer and lowered her sails. Four foreigners, including one carrying a sword, who seemed to be the captain, came up on deck as the ship circled around the Inawaka-maru. Upon realizing that the Japanese vessel was disabled, they came aboard. Two sets of Japanese swords that belonged to the two officials from Iwakuni were found in a closet at the stern and were confiscated. The captain asked the Japanese something, but they could not understand English. The Japanese asked for food by putting their hands on their stomachs, pointing to their mouths, and bowing with their hands together. The captain touched each one's stomach and took a look around the galley. When he realized that they had no food or water, he took all eight Japanese on board his ship, assisting them by taking their hands and putting his arms around them. The personal belongings of the Japanese were also transferred. The rescuing ship was an American trading vessel, the Tabour, commanded by Captain Cornelius Sole. The Japanese had been rescued after being adrift in the Pacific for more than seventy days. Aboard the Tabour, the Japanese were served a large cup of tea with sugar.

It tasted so good that they asked for more, but the captain did not allow them to eat anything more on that day (remedy for starvation). On the following day, they were given two cups of sweetened tea followed by a serving of gruel. This was repeated for another three days. On the fifth day, when everyone gradually became well, they were served rice for breakfast and dinner and bread for lunch. The bread, tasted by the Japanese for the first time, was described by Zenmatsu as similar to a Japanese confection called Higashiyama, which is shaped round like a cross-section cut of thick daikon (radish). The Japanese had no words to express their gratitude and they were deeply touched by the kind treatment received from the foreigners. On May 5, 1806, the Tabour arrived in Hawaii and docked in Oahu after forty-five days of sailing following the rescue. Zenmatsu reported being rescued by a foreign ship at 4000 RI (9760 miles) from Hawaii and 1000 RI (2440 miles) from Japan. He also stated that the distance between Japan and Hawaii is 5000 RI (12.200 miles). Zenmastu was considerably off in his distance estimation as the distance between Japan and Hawaii is 3800 miles. According to Zenmatsu, nearly five hundred men and women onlookers gathered around them when they disembarked from the ship.

They camped outdoors on the night of their arrival. Steamed potatoes (sweet potato or taro) were brought to them the following day. On the second day after their arrival, Zenmatsu reported, the building of a house for the Japanese was started, probably on orders of the chief. More than fifty persons were engaged in cutting trees from the mountains and building a house with a thatched roof. Only four days after their arrival, the house was completed, and the eight Japanese moved in. People brought Kalo (taro) and Uala (sweet potatoes) in gourd containers while the house was being constructed. A fence was built around the house when the Japanese moved in to prevent others from entering, and a cook was assigned to prepare meals for them. Two Hawaiian guards were assigned since so many onlookers were gathering around the fence trying to look into the house. To satisfy the onlookers' curiosity, four Japanese in turn walked inside the fence and after a while, people started leaving, talking to each other. More and more onlookers arrived for almost two weeks, but their numbers gradually diminished to thirty to fifty a day.

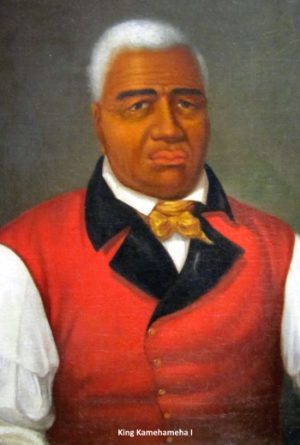

The Japanese remained in Hawaii for more than three months until an American ship offered to take them home. When the trading ship Perseverance, commanded by Captain Amasa Delano, arrived in Hawaii, Delano learned that Captain Sole had left the Japanese under the care of King Kamehameha I until another ship could take them back to Japan via China. Capt Sole left one of the anchors from the Japanese wreck, forty axes, and some other articles to compensate for their living in Hawaii. Sole also left a note describing the Japanese for anyone who could take them back to Japan. Thus, Delano offered to take them as far as China so that they could find their way back home on another ship inasmuch as only Dutch and Chinese ships were allowed to enter Nagasaki, the only port then open to foreigners. On August 17, 1806, all eight Japanese left O'ahu with Delano aboard the Perseverance. Zenmatsu described the departure in personal terms: August 15, was a day for festivities for our home village shrine. Everyone felt so homesick, longing to return home. On that same day, an American trading ship, the Perseverance, about 2000 Goku (300 tons), with a crew of sixty-three, arrived in Hawaii for their provisions. Learning of our presence, they came to see us. Upon seeing a banner-like object that was left by the captain of the rescuing ship, and after talking among themselves, they urged us to board their ship.

Japanese Survivors Leave Oahu - 1806 The Hawaiians, old and young, who had become friendly to us during our stay, brought taro, sweet potatoes, beef, pork, and chicken to the ship and stayed around us, and one by one bade farewell to us. When the ship left Honolulu on August 17, about five hundred Hawaiians came out to the shore, waving their hands and shouting 'goodbye'. They stayed to see us off until the ship was out of sight. We were so deeply touched that we all could not hold back our tears. About 2000 RI (4880 miles) of sailing away from Hawaii, the Americans pointed to the north saying 'Japan! Japan!' We became excited, purified ourselves, and bowed toward the direction of Japan. When we begged the Americans to take us to Japan, they indicated 'no' by gesturing with signs signifying that we would be beheaded. The Perseverance arrived in Macao on October 17, 1806. On December 25, the Japanese were sent to Jakarta, Java, on a Chinese ship. They were in Jakarta for more than four months and apparently contracted malaria and other tropical diseases.

Thus, only three of the original eight finally reached Nagasaki on June 17, 1807, onboard an American ship flying a Dutch flag. All others died in Jakarta or on the ship. Unfortunately, one more died soon after returning to Nagasaki, and another committed suicide during the official interrogation there. Zenmatsu was jailed and underwent severe interrogation by officials as he had violated the Sakoku edict, which prohibited Japanese subjects from leaving the country. Zenmatsu was kept in Nagasaki for five more months before being allowed to return to his village on November 29, 1807. Soon after his return, he was summoned by Lord Asano of Aki to report on his overseas experiences. He died six months after his return. The King delegated the responsibility for the Japanese to Kalanimoku who had 50 men construct a house on May 6 for the Japanese. It took four days to build and a cook and two guards were assigned to the house, which attracted crowds to these men of different ethnicity. On August 17, the Japanese left Hawaii aboard the Perseverance to Macau. From there they took a Chinese ship to Jakarta on December 25. In Jakarta, they fell ill and five died there or on the voyage to Nagasaki where they arrived on June 17, 1807, and where another died. At the time of the Sakoku, it was illegal to leave Japan and the remaining two survivors were jailed and interrogated. One committed suicide and the remaining survivor Hirahara Zenmatsu eventually made it home on November 29 1807 but was summoned by Asano Narikata, the Daimyō of Hiroshima, to recount his odyssey of an experience titled Iban Hyoryu Kikokuroku Zenmatsu. Hirahara Zenmatsu died six months later.

Gannenmono In 1866, Eugene Miller Van Reed, a Dutch American, went to Japan as a representative of the Hawaiian Kingdom. Read the full article

#133rdFieldArtilleryBattalion#16.VGD(German)#198.PB(German)#201.-Gebirgsjäger-Bataillon#202.-Gebirgsjager-Bataillon#232ndEngineerCombatBattalion#34thInfantryDivision#388.-Infanterie-Division#3rdInfantryDivision#442ndInfantryRegiment#442ndRegimentalCombatTeam#522ndFieldArtilleryBattalion#602.-Schnellabteilung#716.-VolksGrenadier-Division#92ndInfantryDivision#933.-Grenadiere-Regiment#AkijiYoshimura#AlamoRegiment#AmericansofJapaneseAncestry#Anzio(Italy)#ArdantduPicq#ArmyHawaiianDepartment#ArnoRiver#AsanoNarikata#BelfortGap#Belmont#Belvedère#BenjaminHarrison#Biffontaine#Bologna

0 notes

Text

B17G #4297904 Lady Jeannette - B24J #4251226 I Walk Alone (1944) (Part Two)

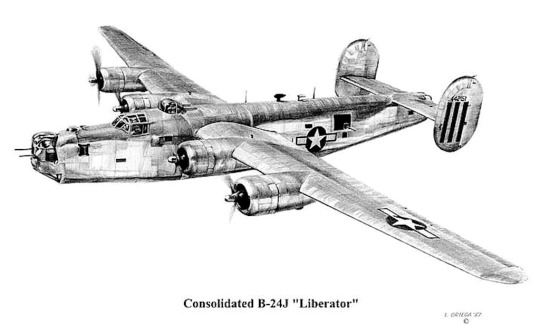

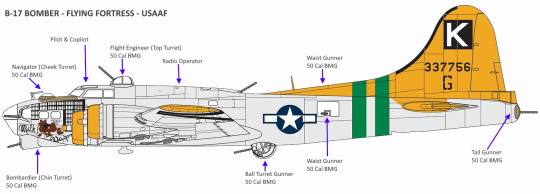

At the 566-ASWB, the on-duty highest ranking officer, and at the 563-ASWB, which was monitoring the action, both were placing calls to their commanders to inform them of the situation. This was quickly passed on to their reporting command, the XIX USAAF. Aboard the B-24, the pilots and crew, who were flying with no light other than the instrument panel and the limited lighting required in the navigator’s compartment and bomb bay, where the switch switcher was waiting to be told by the navigator, the next switches he was to turn on or off. Engine #3 provided the major power to the interior of the plane, including the electric motors that drove the hydraulics which provided the power to operate the chin and tail turrets. Suddenly, their left wing was lit up and loud explosions were heard. The engine suddenly shut down and a fire started within the cowling. At the same time, the bright light ruined the night vision of the pilots and immediately the electrical power died. The pilots immediately switched on the emergency power that was supposed to be provided by Engine #2 emergency generator and even though the power meter showed it was providing the interior of the bomber with emergency power, it was obvious none was being supplied. The emergency power check was one the pilots conducted when preparing to take off. Without that emergency power, they were not supposed to fly. However, the B-24’s top-secret electronics were being constantly updated and each upgrade required more power.

The original power was supplied from large forklift batteries, however, after some mission one night, the top-secret equipment shut down which caused that night’s mission to fail. Upon discussion by the 'genies' who maintained the equipment, they realized the equipment now required additional power. As the normal emergency generator on engine #3 was rarely used, the decision was made without the crew being told, to install a hidden connection on that emergency generator’s supply line, that diverted the emergency power to the top-secret equipment. One night, during a main generator problem, the pilots switched to the emergency power. The voltage flux in the top-secret equipment caused it to fail and they had to shut down the mission early. Upon their return, the 'genies' discussed the problem and decided that the engine mount for the emergency power generator was the same as the main generator, so they replaced the normal emergency power generator with a larger main power generator and at the same time they rigged the power switch so the crew would think they had the required emergency power when in fact it was no longer available. That greatly increased the power available to the top-secret equipment and it would prevent any emergency switching that may damage the equipment. So, without informing the flying crews that they no longer had emergency power if required, they wired the switch to give a false indication. In fact, with the obvious knowledge of the electronics officer, the executive officer, and the commander of the squadron, a decision was made, that the top-secret electronic equipment was more important than the lives of the aircrew.

Hornsby felt the plane begin to buck and want to dive due to the sudden unbalance of power, so he had to gain control and with Casper working the other engine’s power output, he told Casper to set off the fire extinguisher to put the fire out. As Hornsby began to regain control, Casper told him, it was not working and the fire was growing. If it continued, it could break into the wing, melting the wing and setting the fuel on fire, and then the wing would break free and they would fall to their death. Hornsby hollered at the radio operator to get back and warn the crew in the back to get ready to bail out, as the intercom was as dead as the generator. Then, he was to go to the nose and tell the men there to be ready to bail out. He and Casper then made the decision, their only hope was to dive as quickly as they could and build up their airspeed to a point where the fire would be blown out. At that time, their eyes were beginning to adjust to the lack of light, however, the phosphorus dots on the instruments were beginning to fade and if he could not see their altitude, he might dive them into the ground. Casper got the flashlight and used it to shine on the instruments so Hornsby could see them. Due to the engine being out, and the interference of the air stream, the bomber had been bouncing up and down and rocking back and forth. However, he started the dive and as Casper called off the lowering altitude, they were able to blow the fire out, both of them had to pull back on the controls to stop diving and regain as much altitude as they could. While they were doing this, the number four, outboard engine began acting up, probably due to damage occurring at the same time the #3 had been destroyed. Until Hornsby was interviewed by the author, he had always believed what he had been told by his commander when he got back to his unit. They had flown so far to the east that they were over the Rhine River when the German anti-aircraft artillery had destroyed their #3 engine and damaged the #4. He remembered seeing the moon reflected off a big river and he believed the lie he was told. The pilots got the bomber under control, however, they were in a pickle. With no lighting in the bomber and with engine #3 dead and the other hurting, Hornsby knew they did not want to try to cross the Channel. A B-24J did not fly well with an engine gone, it was worse when the remaining engine on the same wing was failing. So, they had to bail out before they got too far to the west. He told Danahy to go back to the nose compartment to check with the navigator to find their location and to tell them while he was going to keep the bomber in the air as long as they could fly west, willing to bail out and crash the plane in Liberated Europe. Casper had to keep the flashlight on the instruments, as the blow buttons would dim very quickly if the light was taken away. The only problem was that he accidentally flashed Hornsby a couple of times and each time, he lost his night vision.

Unknown to the pilots, Sgt Bartho, in the hydraulic-driven nose turret had immediately rotated his turret to the right to see what had caused the explosion. Then, when the power went off all of a sudden, he had no hydraulic power and he could not turn the turret. Bartho was a taller man and when the author interviewed several B-24J nose gunners, they told him that if you were tall it was impossible for you to follow the emergency instructions in case of such a failure. The gunner was supposed to bend down, reach toward the rear of his seat then disengage the hydraulic drive from the gear drive. Then, he had to reach an emergency handle that was clipped to the back of his seat. Once he had the handle, he had to insert the end in a small hole in the bottom of the turret. This would then allow him to hand crank the turret back to its neutral position and allow him to open the turret door to exit the turret. At the same time, in the nose of a B-24J, one of the crew had to be inside the nose, near the turret and he had to open an inside door that had to be open so the hatch door could open and the gunner could get out. At some point, Lt Grey had to have realized Bartho was not able to move the turret, and with the intercom out, he could not communicate with anyone to help. I believe, as the only man who knew what the top-secret equipment was capable of doing, he had been ordered, not to be captured.

In the cockpit, Hornsby and Casper agreed it was time to bail out, as they did not want to accidentally fly out over the Channel. They knew they did not have the ability left to cross the Channel and they did not want to die in the Channel. It had been about a half hour since the engine damage had happened and when Danahy returned, he said the navigator had no lights, other than a flashlight and he actually had no idea where they were, except they had to have flown far enough to the west, it was time to bail out. Hornsby then gave the order to bail out telling Casper and Danahy that he would stay in for five minutes or until the plane had less than 10,000 feet, and then, he would follow. Casper immediately stood up, opened the escape hatch above the pilots, and bailed out. Danahy and the flight engineer went to the waist. Everyone had their chutes on and they started to drop out using the waist emergency exit. The flight engineer headed for the nose, hollered for them to bail out and he went down into the nose escape hatch, past the nose wheel, and fell free. Back at the waist hatch where Danahy had sat down on the edge with his feet out in the slipstream, Mears asked him if he had seen Bartho. Mears and Bartho were good friends and tonight, they had exchanged their normal positions. Danahy hollered no, he had not and Mears hollered back, that he was going to the nose to check on Bartho. Danahy really did not want to bail out by himself and he tried to pull himself back up, but the slipstream would not let go and it pulled him down and out. That was the last time, any survivor saw Mears, the following being based on what must have taken place in the nose. Mears arrived in the nose and it is obvious that he and Grey continued to work to help Bartho. One has to question the actions of Lt. Grey. He knew, they had been told to bail out, he had his parachute on, and yet, he did not drop down and out of the nose escape hatch. Mears arrived and realized that Bartho must have turned his turret away from its home position, just as the hydraulic power went out. With the intercom out, they would have been unable to communicate. Even though they had been told to bail out both had parachutes on and both were a couple of steps from an escape hatch. Both were staying in the nose and both had to know they were going to die when the B-24 crashed. The author believes, Lt Grey stayed with the bomber as he was the only one aboard, who knew exactly what the electronic equipment was capable of doing and it is most likely that he was ordered to end his life if he thought he might be captured. In the cockpit, Hornsby looked at his watch and when the time was up, he climbed up out of the pilot's escape hatch, slid down and off the bomber, and pulled his zip cord.

In the nearby countryside, the French woke up to the sound of laboring engines, then a sudden shriek as the aircraft went into a dive, followed by an explosion, the sound of the bomber hitting the earth, then another explosion, and all was silent. At the nearby, A-72 American Air Base, the home of the 397-BS, Pvt Barney Silva woke up in his bunk as he heard what sounded exactly as the movies portrayed the diving crash of an airplane. There were two explosions and then, silence. He had just pulled the covers up over his head when the intercom speaker came alive with the announcement, 'Pvt Silva, get your ambulance and report to the headquarters at once. He checked the time and it was just 0230 in the morning of November 10, 1944.

Lt Casper had been the first one out and as he was higher and the wind was blowing he landed the furthest to the west. He had been falling through the sky when he saw dim lights and suddenly he landed on the slate roof of a building. He began to slide down one side and his parachute went down the other. Inside the building, the office of a sugar factory, the night fireman heard something on the roof and sliding tiles. He had been looking out a window to the northwest after hearing the approaching plane. When he heard something land on the roof, it was sliding down the roof, along with some loose tiles. He started toward the door and heard a knock. Casper had slid off the roof and was falling straight down when his parachute shrouds tightened and he came to a stop, standing in front of the door. At the same time, his parachute slid clear and as it fell, he collected it. When done, he knocked on the door, which was immediately opened by a Frenchman. The man could speak enough English to understand Casper and he went to a telephone and made a call. In a few minutes, the telephone rang and the Frenchman told Casper, that the nearby American base was sending a vehicle to pick him up. Danahy and Chestnut had bailed out very close together and landed in a pasture. They immediately got together and heard people talking, a short distance away they saw the doors of some houses open and they walked over, they were invited in and told they were sending someone to a house with a telephone, who would call the nearby American air base to have them picked up.

Just before the men began to land, they had been tracking their bomber by the sparks blowing out of the damaged engine, then the sound changed and it was diving to the ground, looking in that direction, most of them saw two flashes and heard the explosions, then there was a flash fire and they knew, 226 had met her end. Danahy landed near a road and the bomber appeared to have crashed a short distance away. He decided, the safe thing to do, was walk away from the crash site until he knew he was safe. He soon came to a stream and heard someone crossing the stream, whistling 'Yankee Doodle Dandy'. He hollered and Chestnut came over and they discussed their situation. They decided they would go back to the road and walk down it, away from the crash site. They had gone a short distance, when they heard someone coming from the other direction, the crash site was still providing a little light and they saw a boy on a bicycle riding toward them. Danahy told Chestnut, he had studied French in school, so he would try to talk to the boy. He stepped out spread his arms apart and began speaking French. He later told the author, that the boy's eyes opened up to the size of a plate, he leaned over and peddled as hard as he could, skirted Danahy, and rode as fast past as he could, down the road.

They continued to walk down the road and soon saw a man coming toward them carrying a lantern. The man approached them and they told him, they were Americans and he motioned they should follow him. Soon, they approached a small village and the man went to a house, opened a door, and invited them in, where the man’s wife offered them coffee, with bread and butter. Unknown to them, the boy was hiding in an outbuilding and the man went out and told the boy to go to the next village and tell the policeman about the two men. After a while, the boy came back and told the man to take them to the village hall where the policeman would be. He indicated the two should follow him and he took them to the village hall. There they were told, a man who had a working car would pick them up and take them to the next location. In a few minutes, a small car, kind of like a Model T Ford, pulled up and Danahy remembered, it had the most chrome he had ever seen on a car. The fellow drove a few minutes, stopped alongside a small hill, and indicated the men should get out. As he left the car, Danahy realized, the man was carrying a pistol and instantly, wished he had his own Colt 45. However, after a couple of missions, the crew realized they were just in the way and they never went where a gun would be needed. The man came around the car, pointed the gun at them, and indicated they should start up the hill. Danahy told the author, that he was certain, the man was taking them to the woods on top of the hill to kill them.

As they approached the hill they could see the trees had a lot of camouflage draped in them and there were several American trailers. As they approached an American came toward them, asked if they were from the crash he had seen. They told him they were and the man told them, there were only two men on duty and they were the radio unit for the nearby airbase. That way, if the Germans flew down their radio beams and dropped bombs, the base would not be damaged. He told them to wait a minute and he would call in and report they were there. In a couple of minutes, he came out and asked the Frenchman, if he could take them to the base. Now, that he knew they were real Americans and not German spies, he was all smiles, and the gun was put away. He agreed to do so and the radio man gave them instructions. Read the full article

#1/LtDanielJ.Gott(Pilot)#1/LtJosephR.Hornsby#1/LtRobertH.Casper#109thEvacuationHospital#2/LtFredericG.Grey#2/LtJosephF.Harms(Bombardier)#2/LtWilliamE.MetzgerJr(Copilot)#36thBombSquadron#397thBomberSquadron#422ndP-61BlackWidowNightFighter#425thNightFighterSquadron#452ndBombGroup#563dAirWarningSignalBattalion#606thMobileHospital#728thBomberSquadron#729thBomberSquadron#730thBomberSquadron#731stBomberSquadron#A-72AmericanAirBase#AN/APS-4#B-17G4297904#B-17GLadyJeannette#BernardLeguillier#BillO’Reilly#BoisdeBuirre#Boulay(France)#CampShanks(NewYork)#Cartigny(France)#Cheddington#ClaudeLeguillier

0 notes

Text

ABOUT

October 28, 2023 Doc Snafu getting Medical Surgery on November 2, 2023. (Nothing really serious but right hand will be over for weeks). EUCMH needs a little help - Thank You

Welcome to the site. Just a few words before, I just want you to know that the entire project EUCMH runs only on donations done by our visitors. Being on rent now, I'm 68, I have no other way to keep this online and this is why I am asking you to understand that it is not easy full time. So, think about and if you can help, just do it. You can donate via Paypal and get a bill (upon request) or you can also in the side bar of every single post do a donation via Give or even via Crypto Currency, USDT (TRC20). A big Big thank you in advance, Gunter G. Gillot (aka Doc Snafu) Gunter G. Gillot, a.k.a Günter G. Gillot Jr (G for Georges), a.k.a Doc Snafu, born unintentionally in Aachen, Germany on May 4, 1955, has exhibited a profound interest in World War Two since his early years. His fascination with this historical period stemmed from his frequent visits to the Krinkelter Forest with his parents during weekends for more than 15 years. Gunter is one of five siblings, having three younger sisters named Katryn, Catherine, and Carole, and a deceased toddler brother. Katrin resides in Heidelberg, Germany, while Catherine resides in the Sainte Marie de la Mer along the Mediterranean Sea in France. Unfortunately, Carole passed away at the age of 44 due to cancer. Gunter's toddler brother also met an untimely demise in the early 1950s. Volunteering for the Belgian Army in the Zone of Occupation in Germany, Gunter's military service stationed him in Düren, Germany, for one year (1973-1974), followed by Siegen, Germany, for another year (1975-1976). During his time in Siegen, he encountered Annegret, whom he later married in 1976 upon his return to Belgium after being discharged from the army. Gunter and Annegret were blessed with three children: Cindy (39 years old), Kimberley (36 years old), and Gary (30 years old). Cindy opted to remain at home and continues to reside with Gunter and Annegret to this day. Kimberley, who experienced a failed marriage, is currently in a committed relationship with Jordao. Kimberley and Jordao are working towards making Gunter a grandfather by September 2023. Tragically, Gary suffered severe injuries approximately ten years ago when he was struck by a young female driver under the influence. The accident resulted in significant damage to his foot and severe brain trauma, leaving him in the process of recovering and reintegrating into everyday life. Despite these challenges, Gunter, now 68 years old, has persevered and maintained his lifelong passion for World War Two and the American soldiers who liberated his parents' and grandparents' generation in 1945. Since 1995, Gunter has been managing the European Center of Military History, dedicating his efforts to preserving and disseminating accurate historical information. He takes great satisfaction in the absence of comments on the center's website, as he exclusively relies on original archives authored by those who actively participated in combat. Gunter's commitment to ensuring textual precision has allowed him to achieve his goal of presenting the most accurate accounts. During his transition from an expert in ammunitions and civilian explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) to a historian, Gunter found guidance in Charles B. MacDonald, a World War Two veteran who served as his spiritual mentor. MacDonald not only provided Gunter with a path to follow but also imparted knowledge on avoiding the publication of sensationalized texts that often cater to the financial motives of post-war individuals seeking maximum exploitation of the subject matter. The European Center of Military History, an esteemed institution dedicated to the preservation and dissemination of accurate historical information, operates as a genuine non-profit endeavor. Its primary sources of funding are derived from Google Adsense advertising and, on occasion, generous donations from the readers of the website. As an organization committed to upholding historical integrity, the European Center of Military History relies on financial support to acquire essential materials such as archives and photographs. These resources play a crucial role in enabling the center to create publications of the highest quality, characterized by meticulous research and comprehensive documentation. While donations from readers are gratefully received, the center often encounters financial limitations in acquiring the necessary materials for its publications. The costs associated with procuring archives and photographs can be substantial, making it challenging to achieve the level of perfection and accuracy that the center strives for. As a passionate advocate for historical accuracy, the European Center of Military History kindly appeals to its readers and supporters for additional contributions. These additional funds would greatly assist in acquiring the materials required to enhance the publication process, ensuring that the center continues to provide valuable historical insights and educational resources to a wide audience (1.75 million in the past 6 years). By investing in the European Center of Military History, individuals have the opportunity to directly contribute to the preservation and advancement of historical knowledge. Their generous support through donations can help bridge the financial gap, enabling the center to acquire the necessary materials and deliver exceptional publications that uphold the highest standards of accuracy. The center remains committed to its mission of fostering a deeper understanding of military history, and it sincerely appreciates the support of its readers and the wider community in sustaining its important work. The European Center of Military History is currently undertaking preparations to establish a comprehensive "Then and Now" photos directory. While I possess knowledge of numerous locations relevant to the project, the accessibility of these sites varies, with some being open to the public and others situated on private grounds. Consequently, I am actively planning to procure professional photography equipment to ensure the production of high-quality images. Maintaining a commitment to precision and authenticity, both in textual descriptions and accompanying photographs, remains a primary objective for myself and the center. The discerning nature of my readers and the majority of visiting historians necessitates an unwavering dedication to accuracy. To fulfill this objective, the acquisition of specialized equipment is imperative. However, due to financial constraints resulting from my current rental status, the cost of acquiring such equipment proves prohibitively expensive and beyond my means. Given the circumstances, any assistance or support in obtaining the necessary photography equipment would be sincerely appreciated. The expenses associated with procuring this material are substantial, making external aid vital for the successful realization of the "Then and Now" photos directory. Support from renowned entities in the industry, such as Kodak USA or Kodak EU, would be particularly invaluable in furthering the project which would costs about 12K. By securing the required resources, the European Center of Military History aims to ensure the highest quality representation of historical sites and their transformations over time. The inclusion of professional photography equipment will enable the center to accurately capture the essence of these locations, providing an invaluable resource for researchers, historians, and enthusiasts alike. The establishment of the "Then and Now" photos directory represents an important step towards preserving historical authenticity and advancing our understanding of the past. Any assistance received in acquiring the necessary equipment would greatly contribute to the center's ability to deliver comprehensive and reliable historical documentation, enhancing the overall value of the project to the scholarly community and the public at large. The last point of this behalf is that I use only Paypal for this because I don't want to collect personal informations about my Donators until they request it. Last be not least, the European Center of Military History welcomes the participation of Guest Writers, a term employed to denote individuals, including children, who contribute to the publication by sharing their parents' diaries discovered in attics or other similar locations. The center acknowledges the inherent value of such personal accounts and encourages their dissemination as a means of enriching historical understanding. The opportunity to collaborate with Guest Writers is a cherished aspect of the center's mission, as it recognizes that history, like freedom, possesses an immeasurable worth that transcends monetary considerations. The inclusion of Guest Writers offers a unique perspective and enhances the diversity of voices within the historical narrative. These contributions bring forth firsthand experiences and personal recollections, shedding light on the multifaceted aspects of historical events. By fostering an environment that embraces the accounts of individuals who have stumbled upon family diaries or other pertinent artifacts, the center cultivates a deeper appreciation for the intricate tapestry of human experiences during significant periods of history. It is of paramount importance to remove any hesitations surrounding the written form, as the European Center of Military History views historical knowledge as an invaluable asset that must be safeguarded and shared. Therefore, if there is any uncertainty or apprehension regarding the articulation of these accounts, the center is ready to assist in the editing and refinement process, ensuring that the essence of the historical narratives remains intact while adhering to established academic standards. In recognizing that history holds a value beyond measure, the European Center of Military History emphasizes its commitment to providing a platform for Guest Writers and the unique contributions they bring. By transcending the confines of monetary considerations and embracing the spirit of historical exploration, the center endeavors to uphold the integrity and accessibility of historical knowledge, fostering an environment where the diverse voices of Guest Writers can coalesce and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the past. Doc and Maryline Solwaster (Jalhay), Belgium June 12, 2023

Read the full article

0 notes

Text

B17G #4297904 Lady Jeannette - B24J #4251226 I Walk Alone (1944) (Part One)