Text

Murder at the Feast, The Treachery of Scone

Many Murders, Many Feasts?

Like the last post, which featured the holy island of Iona, I will return to the subject of this piece, Scone, as it is a place with nearly as many legendary and historical accretions. Primary among these is the story that the Scottish king Cináed mac Ailpín, or Kenneth mac Alpin, murdered a number of Pictish nobles at a feast in this place and thus affected the political union of the Picts and Scots. The first thing to say about this legend - and it is a legend - is, apart from the fact that the story is old, there are plenty of parallel tales from other places.

It would be as well to look at Ireland first, as there may be obvious common Gaelic ancestry to the motifs of death at the feast or extinction of ancient races. When tribal names ceased to be used, for whatever reason, later writers sometimes explained this by saying that the entire identified people had been wiped out. In Ireland it was stated that the tribes named the Domnainn and Gáliain were exterminated. The Gáliain suffered a nasty supernatural end when most of them were killed by druids chanting malevolent spells against them. The tale about a massacre of Picts appears as the title to a tale, Braflang Scóine, 'Treachery of Scone', which appears in the 12th century Book of Leinster as one of the famous tales which poets should be able to recite. The fame of the legend was widespread soon after this, for a version of it was known by Giraldus Cambrensis in Wales. His work Liber de Printipis Instructione, 'Instructions for Princes,' was started in the late twelfth century. According to him:

The Scots betook themselves to their customary and, as it were, innate treacheries, in which they excel all other nations. They brought together as to a banquet all the nobles of the Picts, and taking advantage of their excessive drunkenness and gluttony, they noted their opportunity and drew out the bolts which held up the boards; and the Picts fell into the hollows of the benches on which they were sitting, caught up in a strange trap up to the knees, so that they could not get up; and the Scots immediately slaughtered them all.

Gerald may well have heard this story while he was in Leinster in the winter of 1186. Earlier in the 12th century the English Henry of Huntingdon may have been drawing on different, Scottish sources when he wrote that Kenneth attacked the Picts and secured the monarchy, battling against them seven times in a single day (an oblique reference to overcoming all seven legendary Pictish regions in one go?).

Beyond Britain of course there are plenty of corollaries of the murder at the feast legend. The Scottish historian M. O. Anderson found a parallel to the tale in the Russian Primary Chronicle. The ancient Greek writer Herodotus gives two prototypes for the murder at the feast tale: Cyaxares of the Medes invites the Scythians to a feast and slays them after getting them intoxicated. Queen Neitakri of Egypt drowns feasting nobles who had been responsible for the murder of her brother in an underground chamber.

Meanwhile we could cite the supposed murder of Celtic Britons by the Saxon Hengist in similar circumstances, as contained in the tales given by Nennius and Geoffrey of Monmouth. This tale also harks back to the supposedly historical incident of 88 BC when Mithridates V, the Great, invited sixty Celtic chiefs of Galatia to a feast and slaughtered them all.

Berchán, Fordun and Other Early Versions

The earliest account of the treachery incident in embedded in the Prophecy of Berchán, a long poem celebrating many Irish and Scottish kings which in its present form is 14th century, but containing much early material. This source speaks of Picts - signified as 'fierce men of the east' - being tricked and slaughtered by Kenneth 'in the middle of Scone of the high shields'. Digging in the earth is alluded to, possibly linking the earliest tradition to the tale told by Giraldus. According to the latter, a band of Pictish aristocrats were invited to a banquet and after they became sufficiently drunk, bolts were withdrawn from the benches they sat it, they fell into a trap or pit beneath and were slaughtered. (An alternative translation of Braflang Scóine is 'The Pit-fall of Scone'), A note in the Pictish kings lists stated that one of their last rulers, Drust son of Ferat, died at Forteviot, and there is a possibility that the story of his death migrated to Scone and was magnified.

The Berchán text magnifies the ferocity of Kenneth, 'a man who will feed scald-crows':

He is the first king from the men of Ireland in Scotland who will take kingship in the east; it will be after strength of spear and sword, after sudden death, after sudden slaughter. The fools in the east are deceived by him, they dig the earth, mighty the occupation; a deadly goad-pit, death by wounding, on the floor of noble shielded Scone. Seventeen years, heights of valour, in high-kingship of Scotland; after the slaughter of Picts, after the harassing of Vikings, he dies on the banks of the Earn.

A far different version of events is offered by John of Fordun in his Chronicle of the Scottish Nation [IV. 3]. In his story, Kenneth's Gaelic chief men are too scared of the Picts to attack. So Kenneth disguises himself with luminous fish scales on his cloak and, during the night, and passes himself off as an angel with a message that God commanded them to attack the Picts. The following day the Gaels fought the Picts and overcame them. Hector Boece adopted this story in the 16th century But the tale likewise has parallels elsewhere. Herodotus tells the story of the exiled Pisistratus to restore himself to power in Athens. He found a handsome and statuesque young woman called Phye, dressed her in armour and mounted her in his own chariot to impersonate the goddess Athene, patron of the city. When they drove through Athens, the crowds were awed into accepting his rule once more. The disguise theme is a well-attested occurrence in folklore, occurring throughout Eurrope (firstly in Italy in the 14th century) and suggests a story that Fordun had picked up from oral sources. The 'disguise as a deity' theme is classified as K1828, and 'disguise as an angel' K1828.1, in Thomson's Motif-Index iv, 438.

This tale is both a dilution of the more brutal earlier tale, transmuting it into a folk legend, but also contains the trace of the tradition that there was an ideological, religious element to the suppression of Pictish independence. A chronicle in the Poppleton manuscript refers back to a lost source describing the destruction of the Picts as a divinely ordained act in revenge for them going against God's will, 'because they not only spurned the Lord’s mass and precept, but also wished to be held equal to theirs in the law of justice [or, 'they did not wish to be held equal to others in justice.].' This may have been a reference to some stubborn Pictish adherence to customs in their own Church. A 13th century record referring to the reign of King Giric mac Dúngail (878-889) returns to this scheme and states that 'he was the first to give liberty to the Scottish churhc, which was in servitude up to this time, after the custom and fashion of the Picts.'

But whatever the facts, Kenneth had not singled out the Picts aggressively on their own for religious or any other reasons. He is reported to have fought against the Saxons 6 times and burned Melrose and Dunbar in a southern campaign.

Versions in Later Historians

By the time of the Declaration of Arbroath in the early 14th century it was believed (by some at least) that the Picts had been entirely wiped out. There was little original added to the legends in the 15th century Andrew of Wyntoun's Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland:

Quhen Alpyne this kyng was dede,

He left a sowne wes cal'd Kyned,

Dowchty man he wes and stout,

All the Peychtis he put out.

Gret bataylis than dyd he,

To pwt in freedom his cuntre!

In the 15th century the Scotonichron of Walter Bower added folkloric and other elements to explain the supposed reasons behind Kenneth's aggression against the Pictish nobles. First was that the Picts killed the king's father Alpin, and also an alliance between pagan English and Pictish forces. More strangely, another reason was the theft of a hunting dog taken by the Picts from the Scots. The 16th century work of John Leslie said that Kenneth defeated the Pictish king Dunster and invaded their town of Camelodonum, killing the inhabitants. Then he passed through all Pictish provinces, nearly putting their name into oblivion and out of memory. Those who escaped went to Denmark or Norway or to Northumberland. Kenneth divided countries among his husbandmen, renamed them. Also in the 16th century George Buchanan repeats Fordun fish scale disguise story. There was a mighty slaughter of the Picts in battle. Kenneth decimated the Picts and defeated them in a fight again in the following year:

The force of the Picts was wholly broken by this overthrow, and Kennethus wasted Lothian and the adjacent country together with those beyond the Forth, that they might never be able again to recover themselves. The garrisons, for fear, surrendered themselves. Those few Picts who were left alive fled into England, to an indigent and necessitous condition.

The Killer Kenneth?

Both Kenneth and his father Alpin bore Pictish names and their origins remain mysterious. One conundrum is the fact that all his immediate descendants and successors undoubtedly bore Gaelic names.It is undoubtedly true that the external pressures of Viking raids may have weakened the two north British nations and forced a union. But cultural trends were perhaps moving towards a kingship which encompassed a wide territory. Contemporary with the supposed conqueror Kenneth, Ireland had its first high-king in the person of Máelsechnaill mac Máele Ruanaid. It has to be noted that slaughters during feasts actually occurred. Kenneth's own son-in-law Áed Findliath in 870 gave a banquet at Dublin for the purpose of slaughtering the chieftains of the Vikings.

Yet it seems to easy to credit that a single act of treachery could have 'wiped out' the Picts. Apart from the apparently Pictish names there is the fact that several kings in the immediate generations following Kenneth described themselves as kings of the Picts. Many generations before them there had been Gaelic-Pictish cultural and settlement cross-fertilisation which makes the cataclysmic murder theory untenable. Kenneth is supposed to have reigned for 16 years over the Picts and was also responsible for bringing relics of St Columba from Iona into mainland Scotland, a move which was partially in response to Viking incursions in the the west. It is widely thought that he dignified Dunkeld with the saint's relics. Some of the relics also went to Ireland at the same time.

Whether Kenneth took advantage of Scandinavian aggression in Pictland is another bone of contention. There was a massive victory for the Vikings there in the year 839 which must have weakened its fighting capabilities. But the notion that he deliberately took advantage of this turmoil is not specifically mentioned until Fordun in the 14th century. What actually happened in terms of the Scots' motivations and actions and the subsequent fate of the Picts is hard to fathom . One pragmatic theory is imagining that the Scots, hemmed in by political pressure from several directions and physically constricted by the geography of Dal Riada, chose to take advantage of expansion into Pictland when the inhabitants of that region were more concentrated on the threat from Norse warbands. This was the favoured solution of Isabel Henderson.

When he died he was mourned by the bards, and a fragment of his eulogy has survived:

That Cinaed with his hosts is no more [or, Kenneth, of many stables]

Brings weeping to every home:

No king of his worth under heaven

Is there, to the bounds of Rome.

The Vanished Race: Picts in Tradition

One side-effect of the legend of the Pictish massacre is the supposed extinction of the Picts entirely. One popular and widespread folk tale is the story of the last picts, popularly known as 'Heather Ale' in some versions. According to this the Pictish race dwindled into a single father and son who were captured by the Scots and forced to reveal the secret of their race's heather ale. The father asked his son be killed and then he would reveal the recipe. This was done, but he said his son may have given up the secret but he never would, so he flung himself off nearby cliffs. The tale is localised in may places, particularly Galloway, where it has mingled with the legend that Picts once lived in this region.

The Northern Isles also have there legends of the people. In one of these, the Picts arrived here from Picardy, but quarrelled among themselves. Some fled to Scotland, others to the furthermost part of the isles and the last of them were slain by Norsemen. They were noted for their diminutive size. Part of this tradition was set down in writing in the Historia Norvegiae, around 1180, portraying the Picts as magical pygmies who built fabulous walled towns morning and evening but vanished underground in their houses at noon. The folk tales therefore seem to have been developing in parallel, or at least closely following, the 'state sponsored' version of the massacre of the Picts at Scone.

Chapel on the supposed site of the Moot Hill at Scone

0 notes

Text

The Battle of Dún Nechtain, A Rearguard Action in Defence of Dunnichen

The battle somewhere in Pictland, during which the Picts supposedly threw off the yoke of the over-reaching of the Northumbrians, is a puzzle on several levels. At the simplest level, there is the name. By the English it was called Nechtan’s Mere, by the Scots the Battle of Dún Nechtain, and by the Britons - who spoke a tongue which would have been intelligible with Pictish - the site of the battle was named Lyn Garan, the Crane’s (or Heron's) Lake. In modern times the place of this encounter has been questioned, a challenge to the assumption made in the early 19th century and broadly believed ever since that the fight occurred at Dunnichen in Angus. The recent speculation that the battle actually happened north of the Grampians runs parallel the recent seismic identification of the powerful Pictish province of Fortriu in the same area, when previously it was believed to have encompassed Strathearn and surrounding areas.

The Bare Bones

We know that the Pictish and Northumbrian armies clashed on a Saturday afternoon, 20 May 685. The respective armies were led by Bridei (or Brude) son of Beli and Ecgfrith son of Oswiu. The forty-year-old English ruler was slain with the greater part of his war-band and the result was that the Pictish territories gained their freedom from foreign rule. Northumbria had been shown unremitting territorial aggression for decades, eliminating the British kingdoms of Elmet, Rheged and Gododdin, hemming in the Strathclyde Britons, plus battling their English rivals of Mercia.

Some Original Sources

James Fraser helpfully brings together the early English, Welsh and Irish references to the battle in his book and they mostly also appear, in translation, in Early Sources of Scottish History.

The Anonymous Life of Cuthbert has that saint foretelling the king’s death to his own sister, Aelfleda, a year before the event. At the actual time of the battle Cuthbert was inspecting the Roman remains at Carlisle when he had a vision of the disaster. Though it is proclaimed as a defeat, no details are given. Stephan’s Life of St Wilfrith, written around 720, gives a prelude to the battle, relating how, in the previous year, the Picts who had been in subjection to the English rose in revolt and a Northumbrian force was sent to quell them. Ecgfirth and his commander Beornheth slew such a number of them that two rivers were clogged up with their corpses.

The Venerable Bede preludes his account of the battle by telling how the Northumbrian noble Berct went to Ireland and ravaged church lands there. This was taken as not only an unwise attack on innocent people, but a fateful reason for the following year’s defeat. Ecgfrith, says Bede, was warned by friends not to attack the Picts. It is Bede who states that the battle occurred in a mountainous place, yet he also states that a major consequence of the defeat was the Picts regaining their freedom, as did some of the Irish living in Britain and a section of the Britons. The English bishop at Abercorn was forced to abandon his base. All of which arguably points to a series of political changes which primarily affected south and west Scotland and may point to the battle being in the area of Pictland adjacent to these other nations.

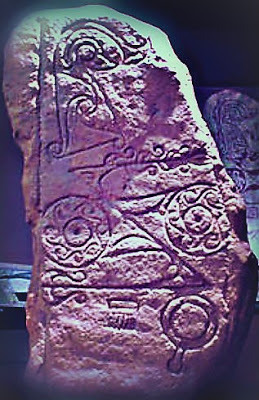

Dunnichen Stone, currently in the Meffan Museum, Forfar

The Cousins, the Four Nations

The fact that Bridei and Ecgfrith were distantly related is a side-point in the discussion of the battle, albeit it shows the wider regional and inter-national concerns of families ruling in the north of England and in Scotland. The Northumbrian prince Eanfrith had been exiled in Pictland in the early part of the century and became attached to a Pictish princess. Their son Talorcan became king of the Picts. Both British Strathclyde and English Northumbria both wanted to exercise controlling interest in the lands to the north of them, and at time in the English case, direct rule over the southern part of Pictland, and therefore we could be justified as seeing southern Pictland as the prize decisively claimed on the battlefield in 685, and another circumstantial piece of support that the encounter took place in the disputed area.

In chapter 57 of the Welsh Historia Brittonum it is stated that Ecgfrith fought against his fratuelem (cousin) Bridei, ‘and there he fell with all the strength of his army, and the Picts and their king were victorious, and the English thugs never grew [strong enough] from that battle to extract tribute from the Picts. It was called the battle of Lyn Garan.’

Alex Woolf translates the text as: ‘It is this Ecgfrith who fought a battle against his parallel cousin, who was king of the Picts, by name Bredei.’

A.O. Anderson states that:

Brude’s mother’s father must have been one of the sons of Æthelfrith. But since we may assume that Brude claimed part of the kingdom through his mother, her father must have been a descendant of Eanfrith, who married a Pictish princess (617 x 633), and whose son Talorcan held the Pictish throne from 653 to 657. The dates seem to decide that Brude must have been Eanfrith’s grandson, not Talorcan’s.’

Alfred Smyth, acting on the undisputed fact that the victor of the battle was son of the British king of Dumbarton, Bili, states that Bridei’s victory cemented Strathclyde’s overlordship of the southern part of Pictland. A. O. Anderson tellingly suggested that Bridei inherited Pictland south of the Tay from his father and the lands to the north from his mother’s family. Perhaps this should be amended to a situation where he claimed Pictland south of the Grampians from his father (or grandfather’s) territorial claims, and the lands to the north from his mother’s kin.

Even supposing that the northerly position of Fortriu is now accepted, this does not exclusively place Bridei in that area; his southern associations were indisputable as a son of the ruling house of Strathclyde. The wider campaign featured a sustained and, on the surface, surprising campaign by the Northumbrians against Ireland. Smyth again points out that this was at least partly motivated by the undoubted presence of a displaced and extremely active British war band there, whom he suggests had originated in either Rheged or Gododdin, British territories which the Northumbrians were actively encompassing into their realm. Leslie Alcock suggests that the English may have taken hostages while in Ireland to prevent Irish allies actively assisting Strathclyde and/or the Picts in military action in the north of Britain, though the theory that Northumbria would have launched a strike in foreign territory solely to subdue the possible intervention of Irish powers in northern Scotland seems rather weak. Whatever the motivation for the expedition, it has to be admitted that Ecgfrith’s long-reach to Ireland supports a military capability to send a force into northern Pictland, albeit a naval raid is logistically easier than a long-range land campaign.

The monks of Meath extended their enmity (if not an actual formalised curse against the violence of the northern English monarch). A poem ascribed to Riagual of Bangor preserves the hatred against the Northumbrian:

Iniu Feras Bruide Cath

Today Bruide gives battle

over his grandfather’s land [or, for his grandfather's heritage]

unless it is the command of God’s son

that it be restored.

Today Oswiu’s son was slain

in battle against iron [blue]swords

even though he did penance,

it was penance too late.

Today Oswiu’s son was slain,

Who used to have dark drinks: [black draughts]

Christ has heard our prayer

That Bruide would save Brega [?]

Picts and Northumbrians after the Battle

It has frequently been claimed that the Picts regained their independence after the battle, which supposes they had lost it (at least partially) before 685. Warfare between Picts and the northern English continued intermittently for some time, into the 8th century, though perhaps the scale was not so great as the encounter at Nechtansmere. In the year 698 the dux Berctred (perhaps a royal leader) of the Northumbrians was slain by the Picts at a place unknown. One sources calls him the consul of King Ecgfrith and interestingly states that he too fell victim of Irish curses, in retaliation for raids on churches in that land. It states that he went into Pictish territory to avenge Ecgfrith and there too met his end.

In the year 711 another high-ranking noble, Bertfrid (the ‘prefect’ of King Osred), also described as ‘second prince from the king’, was victorious against the Picts. The similarity of his name to the official who died in 698 (and also the Northumbrian who ravaged Ireland in the 680s) may mean they were close relatives. By the time Bede wrote his Historia Ecclesiastica in 731 there was a treaty of peace between Angles and Picts. This had its roots in the actions of the Pictish king Nechtan mac Derile who, several years earlier, as Bede recounts, asked Ceolfrid the Abbot of Jarrow to send him writings concerning the correct date of Easter and also architects so he could build a church of stone in the Roman manner. It is important to bear in mind F. T. Wainwright’s warning not to overestimate the importance of the battle. The event was not a permanent turning point in the power struggles of the four northern nations, nor a proto Bannockburn. The Picts may have regained independence, but further defeats were inflicted upon them by the English. The Northumbrians held sway up to the Forth and the Britons may have temporarily gained the upper hand, but in the following century they suffered further military and territorial defeats by the English. The Scots of Dalriada, in the wings meanwhile, had to wait a century for the beginning of their ascendancy.

The Pros and Cons of the Place Claimants

The following points regarding the pros and cons of Strathmore v Badenoch as the battle site are intended more for illustration of the issues rather than a fully weighed balancing of the respective merits of each place.

The landscape of both Dunnichen in Angus and Dunnachton in Badenoch, Inverness-shire, have naturally changed a great deal in the centuries since 685 AD, Arguably the change has been greater in the former, with unremitting human settlement, farming and drainage vastly altering the land. Nechtan's Mere itself has been drained, and it is likely that it once formed a chain of lochs in this part of Strathmore. Without going into detail there are disputes about the exact location of the battlefield, even if we accept that the battle was fought in this locality. Fraser and Alcock have differing views, which we will not go into here. Another interesting point is the location of possible local power bases which Bridei may have used. The fort on Dunnichen seems to have been rather small, as far as we can judge, but the complex of duns and forts on Turin Hill, not far north at Rescobie (one of which was known as Kemp's Castle), looks more promising as the putative regional power base for the whole region. (Turin will be the subject of a future post.)

For Dunachton: The mountainous terrain matches the brief description in one Northumbrian source.

Against Dunachton: Considerable distance from the main territory of the Northumbrians. No supplementary evidence that there was either a battle in the area of that this was a conspicuous focus of Pictish power. The symbol stone at Dunachton is an earlier example (formerly known as Class I) and does not have any representations of battle, fighting or armed men; nor do there seem to be any such stones (similar to the Aberlemno stone) within the vicinity of Dunachton. There are no major known Dark Age Pictish strongholds in the area.

For Dunnichen: The Pictish stone at Aberlemno undoubtedly portrays a major battle and is the only surviving representation of battle on any Pictish stone, only 5km from Dunnichen. The proximity of the probably hill fort on Dunnichen Hill, plus another several miles away on Turin Hill.

Against Dunnichen: Geography does not seem to match description of mountainous terrain in the English description given by Bede.

It has to be stated that nowhere is it stated that the Battle of Dunnichen/Nechtansmere/ Dún Nechtain actually took place in the kingdom or district of Fortriu, so the consequence of Fortriu’s re-alignment is almost irrelevant to the placement of the battle. James Fraser wrote his Battle of Dunnichen before the publication of Alex Woolf’s article. In From Caledonia to Pictland he acknowledges the merits of Dunachton as a possible alternative location for the battle, but still advises that Dunnichen should not be ruled out. There is the powerful neighbouring presence of the Aberlemno stone and also, as he points out, this is the zone from which the Northumbrians were rulers and were now removed.

In terms of the viability of a large war band striking out from home territory (south of the Forth in this case) into hostile lands, it would have necessitated a short, decisive campaign and Badenoch may have been beyond its practical reach. The Annals of Ulster seem to state that Ecgfrith burned a place called Tulla Aman, in Strathearn, as part of a campaign before the battle. Following such slash and burn tactics with a strike into the deep, unknown north, with the enemy fully forewarned of his scorched earth actions, would surely have been unthinkable for an experienced campaigner, as it would have given the Picts time and opportunity to gather immense military reserves from a vast hinterland.

The Aberlemno battle stone.

The Battle Stone

It would be churlish to deny that the Aberlemno stone shows a battle in progress. Nine men are featured. The top scene is construed (by Cruickshank) as a Pictish horseman pursuing a Northumbrian knight off the battlefield. The middle scene shows - possibly - three Pictish foot soldiers fighting an enemy cavalry soldier. Two opposing horsemen face each other at the bottom of the stone, then there is the large, isolated figure at the bottom right, discussed below.

The Vagaries of Tradition, Angus and Badenoch

It would be impossible for anything to survive in tradition or folk memory which directly relates to the Battle of Dún Nechtain, though of course the Irish, English and Welsh written memorials of the event could arguably constitute early examples of this. If we accept that the attribution of a battle at a place near the ‘fort/stronghold of Nechtan’ is legitimate and early, this can be explored further. There was both a saint and several Pictish kings who had the name Nechtan. The battle could not have been named after the king Nechtan son of Derile who ruled in the early 8th century and was instrumental in intellectual and spiritual links with the kingdom of Northumbria.

According to Affleck Gray, there were traditions of both a king named Nechtan and of warfare at Dunachton in Badenoch. The present Dunachton House stands on the site of an earlier property and in close proximity to St Drostan’s Chapel, actually cited as Capella de Nachtan in the late 14th century. This would seem to point to an association with the saint rather than the king, though at this remove in time it must remain unproven. What remains in terms of folklore at Dunachton is a mixed bag of elements from various times, apparently. To the west of the present Dunachton House is Tom a Mhòid, the Court of Justice Knoll, where local lairds dispensed justice from. Close to this is another hill named Creag Righ Tharoild, supposedly named after a Viking chieftain. The local tradition states that Nechtan defeated the Picts in this place. It also states that the king was forced to abdicate by another royal Pict, who was then challenged by a second pretender in a bloody battle. Following this, Nechtan resumed his rule in peace. These seem to be references to the Pictish civil wars faced by Nechtan son of Derile in the early 8th century. However, there was no Scandinavian element in these wars, as it was too early a date for Viking incursions. Based on this it could be surmised that the local traditions seem to be influenced by modern discussions of the reign of this latter Nechtan, perhaps superimposed on actual local associations with St Nechtan.

At Dunnichen there is no recorded local tradition of warfare between Picts and Northumbrians, though in Angus there are other supposed traditions of Picts fighting Scots (near Forfar and near Dundee) and at Barry (Picts fighting Vikings). None of these ‘traditions’ mention Nechtan, and they are overwhelmingly literary and antiquarian in character, some of them invented by the locally born national historian Hector Boece. Place-name and hagiographical material suggests that there was an association in Angus and the very northern part of Fife with a person of some importance named Nechtan at a very early date. Dunnichen of course means ‘Fort of Nechtan’ and may tentatively be linked to a ruler of that name who held power in this vicinity. A king named Nechtan is supposed to have been brought back to life at his fortress in Carbuddo in Angus by the 5th century Irish saint St Buitte son of Bronaig (founder of Mansterboice in County Louth. The tale in present form is from the 12th century.) This accords with the supposed propensity of saints to gain ownership of non-religious power bases, but there are problems identifying the exact location of this royal base in the area.

Postscript: the King as Carrion

As stated above, one of the primary aims of armed conflict in the Dark Ages was to eliminate the leader of the opposing war-band. That accomplished, would there have been any special treatment of the physical remains of the slain leader. It is tempting to think that there would not have been, albeit of course that both Bridei and Ecgfrith were nominally Christians, and moreover actually distant relatives. One later record (Symeon of Durham)states that the body of the slain Northumbrian was carried away to be buried in distant Iona. The king's father Oswy and his uncle Oswald were exiled on the hold island and his own successor Aldfrith was also a monk among the Irish there, so the connection was strong and personal. James Fraser however ingeniously hypothesises that the 'other' Island of St Columba was the actual place of burial, Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth.

However that is, the undoubted fact is that Ecgfrith was slaughtered on the field. There is a likelihood also, if we accept Cruickshank and others' support of the Aberlemno battle stone as a visual representation of the battle, that the figure on the bottom right represents the extremity or aftermath of that king. The figure is proportionately larger than the others on the stone, signifying undoubted importance. He is a helmeted warrior, with a shield either falling from his grasp or lying beside him. This leads to an important point: is the stricken figure standing (and falling), or is he already prone on the ground? It is really impossible to say, though I would guess that the man is caught in the act of falling down. If this is the case he is being plainly attacked by a large bird which seems to be going for his face or throat. Is it an eagle or other raptor symbolic of the other king, whose forces killed him, or a totem of Bridei's tribe? On the other hand, if the body lies lifeless on the field of slaughter it may well be a not at all symbolic carrion bird which is helping itself to his flesh.

There is another possibility, a shadowy adjunct to the theory of an attack on a live human. Is the bird in fact plucking out his eye? Some birds were regarded as more than sinister or symbolic to various early Celtic and other peoples, and whatever species the bird here represents, it may be regarded as the shadow of a recently departed Pictish deity getting revenge on its tribal enemy.

Nikolai Tolstoy pointed out the Welsh verse which hints at a lost legend featuring the north British king Gwallawg:

Cursed be the white goose

Which tore the eye from the head

Of Gwallawg ab Llenawg, the chieftain.

0 notes

Text

Do Shining Streams Dream of Radiant Ladies?

The Paphrie Burn in the north of Angus is no-one's idea of a roaring river or an awesome body of water, but someone once thought it was amazing, because its name comes from a Pictish root cognate with the Welsh pefr, which means 'radiant' or 'beautiful' (Inverpeffer near Arbroath derives from the same word). The valley of the burn is in an area packed with ancient associations. To the south is the Mansworn Rig, scene of a bloody encounter* and to the east are the hill-forts, the Brown and White Caterthun.

A ghost goes here, about its solitary business in this small glen of the radiant stream, or at least it did until the land was changed in the late 19th century. There is nothing so resonant as a dead ghost. But at least the tale remains, and here it is, as told by the Rev. Frederick Cruickshank in Navar and Lethnot, The Story of A Glen Parish in the North-East of Forfarshire (Brechin, 1899):

n a hollow part of the road betwixt Menmore [Menmuir] and Lethnot is, or rather was, for recent improvements have done away with it, a place called the Leuchat Pool. The burn running down from it to the Paphrie is still the Leuchat burn. There is a well known tradition that close by this Pool a Tailor, once on a time, killed his sweetheart. She has ever since haunted the place, and is recognised by her dress of light grey, which has given her the name of "the white wife." Many persons passing by on dull evenings have seen her. One of the Leightons of Drumcairn told me that he was riding across the Tullo hill on a moon-light night, when the spectral figure presented itself to his view. He knew at once what it was, but to make sure he struck at it with his whip which went through the seeming woman without meeting any obstruction. His courage then gave way, and he set off up the brae as fast as his horse could go. The figure kept an even pace with him for a little way, and then all at once disappeared. I remain to this day under the impression that I once saw her myself. I had been at the Manse of Menmore dining with my kind and hospitable friend, Mr Cron, and was walking home. The time might be past eleven, but the night was not dark. On reaching the Leuchat Pool, i saw a woman, clothed as above described, seated on the bank at the right hand side of the road. I spoke to her in the usual manner, but to my surprise she made no answer, and got up, taking her way towards Menmore. I did not think of the "white wife" at the time, and am not sure if up till then I had heard the story. I took it for granted that it was some poor benighted traveller like myself, who was taking a rest by the road-side, and recognising me she was afraid to speak lest her voice should betray her. But since that time I have come to the conclusion that if such a spectre haunts the place, it was certainly visible to me that night. [Navar and Lethnot, 299-300.]

[Author Adam Watson, incidentally, derives the name Leuchat from An Fhliuchad, 'the wet place', Place Names in Much of North- East Scotland, p. 107.]

The Rev. Cruickshank, the son of a weaver from Kirriemuir, was born in 1826. He became the incumbent of Navar and Lethnot in 1854 and resigned as minister in 1905, dying three years later. Apart from the parish history quoted from, he also wrote Historic Footmarks in Stracathro (Brechin, 1891).

As a footnote, it should be noted that White Ladies are particularly prone to haunt burns and other water features, though the Angus variant, in Dundee, Claypotts, House of Dun and Balnabreich generally dispenses with this rule of nature (apart from Benvie, possibly).

* Tale of the Mansworn Rig.

On the eastern side of Tullo Hill, Menmuir is the Mansworn (i.e. Perjured) Rig. It received its name after a dispute between two landowners. Both men brought witnesses to the place to swear that the land belonged to their respective masters. One servant swore to God that he was standing on his employer's ground, which so enraged the Laird of Balhall that he pulled a pistol from his belt and shot the man dead. When the body was examined it was found that he had filled his shoes with soil taken from his master's land so that he could truthfully swear his oath.

0 notes

Text

I've put out a call for information today via Facebook, Twitter, Google+, etc. to see if anyone can provide me with any additional information regarding "The Man With the White Sandshoes". This character is a kind of urban legend, whose supposed activity stretched over many decades in the mid to late 20th century. In summary, he was a nameless but terrifying apparition - I'm not sure whether human or ghostly -who terrorised people in Dundee by chasing after them, for unknown reasons. Generations of children had him whispered about by cold blooded siblings and older associates who took delight in instilling mortal fear in more gullible bairns.

A cursory investigation shows that the character (archetype?) is familiar in other parts of Scotland, most in the west, where he was sometimes known as "Sandshoe Sammy". More intriguingly, the same character also featured in the urban parts of North-East England. I always believed that the spectre was well-kent in Dundee, but there is no mention of him in Geoff Holder's very well researched Haunted Dundee.

0 notes

Photo

Antiquities from Guthrie and Kingoldrum

https://angusfolklore.blogspot.co.uk/

0 notes

Text

Celtic Relics - The Kingoldrum and Guthrie Bells

This post concentrates on those evocative but elusive ancient items associated with the ancient church in Scotland, Ireland and elsewhere, hand bells. Previous posts have mentioned several of these which were located in Angus.

St Medan's Bell

was associated with

Lintrathen

and

Airlie

and there are records of its hereditary keeper, who resigned it to the Ogilvy family, in the 15th century. Tragically, it was mistaken for scrap metal in a local sale in the 19th century and destroyed. The Lindsay family owned

St Fillan's Bell, though its hereditary keepers were the Durays of Durayhill

, dempsters of the Laird of Edzell. Sadly, this bell has also been lost. Francis Eeles described the two forms of early bells from the Celtic tradition. The first type was formed from a sheet of iron bent into a quadrangular shape, with rivets up one or two sides, coasted with bronze or copper, with a handle on the top. A later type was more regularly bell-shaped, made by a complete casting. Around 20 early quadrangular bells made of iron or bronze have been survived in Scotland, and around twice as many from Ireland, and the consensus among scholars is that they were brought into north and eastern Pictish territories by the family of Iona.

Hand-bells were the only type known during the early medieval period as the technology necessary for casting free hanging bells such as were later used in church towers etc. was not known. Hand-bells, whatever their precise use, were rung by striking, rather than being made with clappers.

The Kingoldrum Bell

Detail of crucifixion from sculptured stone at Kingoldrum.

The church and lands of Kingoldrum, north-west of Kirriemuir, were one of the early royal grants to Arbroath Abbey in the early 12th century and seems to have been an established power centre as there are fragments of sculptured stones there (though there are no records of the site in earlier records). While the kirk of the parish (which is no longer in use) was built in 1840 it sits roughly on the same site as its medieval predecessor, on a prominent mound and within a large, circular graveyard, which may indicate a very early date, though to my knowledge there has been no archaeological investigation to confirm this. Like Airlie, Kingoldrum was dedicated to St Medan, who had an attested early cult locally, and there was a well (now lost) dedicated to this cleric nearby. Gaelic seemed to flourish alongside Scots for a long period in this locality.

In 1843 an old

scellach

or bell, made of sheet metal, was found here. A bronze chalice and glass bowl were recovered beside it. Warden reports that:

A curious bronze cross and chain were found in a stone cist near the Church. These and the bell were presented to the Museum of the Society of Antiquaries by the Rev. Mr Haldane, the minister of the parish, but the chalice and bowl have disappeared. In another cist was a skeleton doubled up, with a rude bronze armlet on one of its wrists.

The Kingoldrum Bell is now housed in the National Museums of Scotland (NMAS KA3). Incidentally, the Rev. James Ogilvy Haldane was minister of the parish from 1836 and died in 1891. The enthusiastic minister also donated other finds from his parish to the Museum of Antiquities: an axe and urn (in 1880 and 1887 respectively), fragments of sculptured stones and metal relics (1867), and, most significantly, a beautiful carved stone ball in 1884, further enhancing the rich archaeology of the area. His father, William Haldane, had been minister of Kingoldrum before him.

Ball of conglomerate (3" diameter) found in Kingoldrum by the Rev. Halldane.

Daniel Wilson reports the finding as follows:

This ancient bell was dug up in 1843, and contained, in addition to its detached tongue, a bronze chalice, and a glass bowl - the latter imperfect. the bell is of the usual square form, made of sheet iron, which appears to have been coated with bronze, though little of this now remains. It measures 8 by 7 inches at the mouth and 9½ inches high, exclusive of the handle. Unfortunately the value of the discovery was not appreciated, and both the chalice and the bowl, it is feared, are now lost.

In

Scotland in Early Christian Times

, Anderson adds the following, lamenting the loss of the other unique items found:

A curious cross-shaped ornament or mounting, decorated with enamel and a portion of a bronze chain of S-shaped links, dug up near the place where the bell was found, and three sculptured stones from the same site, are also in the Museum. It is impossible to determine with certainty what the two articles, which are described as a chalice of bronze and a bowl or goblet of glass, may have been. We can only regret their loss, all the more to be deplored that nothing answering to this description has ever been found in connection with any other remains of the Christian period. No chalice of the early church exists in Scotland. [The metal finds mentioned here were donated by Haldane in 1867.]

Kingoldrum finds, illustrated in

Scotland in Early Christian Times

.

The Guthrie Castle Bell

The ancient bell which was kept (for centuries, one assumes) at Guthrie Castle is now in the National Museums of Scotland (NMAS 1922: 40). It is interesting that we have another example here in a church relic in the hands of a secular landowning family, which means that the sacred object was intimately connected with the hold a particular kindred had over the land they owned. Unlike Kingoldrum, there does not seem to be much evidence that Guthrie was an important focal point of secular or ecclesiastic power in the Pictish era or immediately afterwards. The Guthries, like the Ogilvys, were a family whose name originated in Angus. However, although they held Guthrie itself and various other local estates, they did not become enobled or play such a prominent part in national events like either the Ogilvys or the Lindsays. The Guthrie Bell is one of only two enshrined bells which have survived in Scotland. (The other was from Kirkmichael-Glassary and is also now in Edinburgh.) Eeles confirms this bell is of the earlier type, described above, and must have been both early in date and associated with an important early saint, from the 8th century or earlier. His unsupported claim that the bell and shrine must have originated in either the west or the north of Scotland can certainly be challenged.

The bell itself is made from iron and stands 8 and a half inches high. Its shrine completely covers it and is made up from four plates richly decorated by ornaments. There are indications that the shrine has been renovated several times. There is an inscription on the shrine which reads J

ohannes dlexandri me fieri feisit

, and made have been made in the 15th or 16th century reconstructions. Francis Eeles summarises his thoughts on the history of the two objects:

The bell itself is probably the relic of some important saint whose fame came down till late in the mediaeval period. It may well date from before the ninth century. It was probably enshrined early in the twelfth century, to which period the figure of our Lord crucified and the small apostle, probably St John, belong. In the fourteenth century the silver plate with its embossed decoration was made and the crucifix and attendant figures were remounted upon it. Late in the fifteenth century or early in the sixteenth, John the son of Alexander made a second reconstruction, changing the position of some of the figures and adding others. In the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries the loss of some figures may have occasioned a further re-arrangement of the rest in the manner in which they now exist, including the refixing of the inscription plate upside down.

The Guthrie Bell shrine

, based on illustration in Anderson's

Scotland in Early Christian Times

.

Selected Works and Sites Consulted

Anderson, Joseph,

Scotland in Early Christian Times, The Rhind Letters in Archaeology, 1879

(Edinburgh, 1881).

Bourke, Cormac, 'The Hand-bells of the early Scottish Church,'

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

, 113 (1983), 464-8.

Catalogue of the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland

(revised edition, Edinburgh, 1892).

Eeles, Francis C., 'The Guthrie Bell and its Shrine,'

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

, 60 (1926), 409-20.

Laing, Lloyd,

Late Celtic Britain and Ireland, c. 400-1200 AD

(London, 1975).

Warden, Alexander,

Angus or Forfarshire

, volume 4 (Dundee, 1884).

Wilson, Daniel, 'Primitive Scottish Bells,'

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

, colume 1 (1851-54), 18-23.

0 notes

Text

Sir John Kirk and the Resonance of Slavery

Slavery as a tangible fact is not something one would particularly associate with Angus, more than any other part of the British Isles, though the county of course had its connections with that trade. Interesting and little-known material about the decent and doubtless God-fearing lairds who quietly owned slaves far away, back in the day, can be unearthed through web sites like Legacies of British Slave Ownership, and though it may seem churlish to name and shame those associated with that business after all these years (people who in themselves doubtless led complex and rich lives), it can still be instructive as an eye-opener.

Among the interesting data is that concerning former slave owners who claimed compensation from the British government when slavery in the British Empire was abolished and they were financially disadvantaged. A cursory search through the records reveals the follows Angus folk as former slave owners: David Langlands of Balkemmock, Tealing, Alexander Erskine of Balhall, David Lyon of Balintore Castle, George Ogilvie of Langley Park, James Alexander Pierson of The Guynd, Thomas Renny Strachan of Seaton House, St Vigeans, Mary Russell of Bellevue Cottage, David McEwan and James Gray of Dundee, the 7th Earl of Airlie.

There is more information surrounding the Cruickshank family, who lived at Keithock House, Stracathro House and Langley Park. Alexander Cruickshank of Keithock was born in 1800 and married his cousin, Mary Cruickshank of Langley Park (formerly Egilsjohn or - colloquially - Edzell's John). In the middle of the 19th century Alexander unsuccessfully attempted to claim compensation for the loss of slaves owned on the Langley Park estate on the island of St Vincent. The whole family's fortunes were inextricably linked with slavery. Patrick jointly owned the estates of Richmond, Greenhill and Mirton in St Vincent with his brother James who was compensated £23,000 by the government following slavery abolition in 1833. The St Vincent estates had more than 800 slaves. Originally from Wartle in Aberdeenshire, the money to buy the Egilsjohn estate in Angus came from a fortune made in the Caribbean; its name was even changed to commemorate the St Vincent estate name of Langley. The Angus estates of Stracathro and Keithock followed. But we are told (Baronage of Angus and Mearns, p. 64) that Alexander Cruickshank's 'affairs eventually got embarrassed - and he returned to Demerara, where he shortly afterwards made his demise, leaving a son and daughter.'

Emigration to the colonies was by no means a passport of quick riches to those who went there with slender means to begin with. John Landlands, son of a tenant farmer from Haughs of Finavon, went to Jamaica in 1749 and found that his promised employment did not exist, though he was helped to secure another post at the vividly named Treadways Maggoty estate. In time he acquired his own coffee plantation, complete with valuable slaves. On his death he provided for his mistress/housekeeper and his natural son born to her, but the estate of Roseberry was burdened by debt and had to be disposed of by his cousin back home in Angus.

There was less known commercial speculation in the slave trade in Angus ports than in other places, though there are records held in Montrose Museum of a business deal from 1751 concerning the ship Potomack, whose master Thomas Gibson struck a deal with merchants Thomas Douglas and Co to travel with cargo to Holland and thence to west Africa and there pick up slaves for the North American market. Researchers reckon that some 31 Montrose vessels were engaged in human slave trafficking, though records survive for only four ships (the other three being the Success, the Delight, and the St George).

One Montrose family of the 18th century who went on to great things financially were the Coutts family, ancestors of the private banking dynasty which migrated to London later and dealt with the fortunes of royals and the nobility. John Coutts (born 1643) was Lord Provost of the Angus burgh five times between 1677 and 1688 (having been made a councillor in 1661). the family were involved in the Virginia tobacco trade and doubtless incidentally involved to some extent in slave ownership. John's third son Thomas went to London and was one of the promoters of the 'Company of Scotland, trading to Africa and the Indies', better known as the company who initiated the doomed Darien Scheme. A grandson of the first John Coutts was another John (son of Patrick), among those in the family who left Montrose for business opportunities further south.

John Kirk - Doctor! Botanist! Knight! Our Man in Zanzibar!

There were few places as strange to the intrepid foreigner in the mid 19th century as Zanzibar, even in an age when the whole continent of Africa held a jewel-like fascination for Europeans. The island was just off the continental coast but was truly a place apart. It had in effect been colonised and annexed before any Western interest in the place by an Arab dynasty from the north. The ruler of Oman, Seyyid Said, made the African island his capital in 1838 and brilliantly maintained his power through diplomacy with the British East India Company and a cannily managed business acumen. The Arab management of African slaves more than matched the newer European-sponsored slave trade operating in west Africa. Throughout Seyyid Said's rule it continued unabated and Zanzibar was its unashamed fulcrum, dispatching human cargo and attendant misery across the Indian Ocean. Alastair Hazell states that the mid-19th century population of the island was possibly 100,000, or which around half were slaves. Said had personally transformed his new centre of operations 'from a mere backwater, a slave market with a fort, to the largest and most prosperous trading city of the western Indian Ocean'.

Gold, ivory and gum copal were other products which flowed out of the continent via the island, but it was the process of the oldest institution on Zanzibar, the slave market outside the Customs House, which was the most outstanding element of that market place to outsiders; here described by the English traveller Sir Richard Burton. It was a place, he said:

where millions of dollars annually change hands under the foulest of sheds, a long, low mat-roof, supported by two dozen tree-stems... It is conspicuous as the centre of circulation, the heart from and to which twin streams of blacks are ever ebbing and flowing, whilst the beach and waters opposite it are crowded with shore boats.

The slave market was in the centre of town and here every year many thousands of bagham, untrained slaves, were tethered and publicly auctioned. In the mid-1850s, Hazell tells us, able-bodied young men could be bought for $4-$12 - 'about the prince of a donkey'. Girls and women were sold for sex, passed on many times via different owner/abusers. A premium was paid for 'exotics' from India or fair haired unfortunates from as far afield as the Caucasus.

The Boy from Barry

Step up John Kirk. The latest biographer of John Kirk - Alastair Hazell - makes the fundamental mistake of stating that Kirk was born in Barry, in Fife! This is a shame because his book, The Last Slave Market, is a well-researched account of this important figure who did much personally to end the intolerable anomaly of Zanzibar's slaving in a time when many cynically turned a blind eye to it. John was the third of his name in succession, following his grandfather (a baker) and father, who was born in St Andrews in 1795 (which perhaps explains Hazell's error). The Rev. Kirk was appointed minister of Barry in June 1824 and transferred to nearby Arbirlot in 1837. In the religious turmoil of the times he joined the Free Church and was minister of the Free Church in Barry from 1843 until his death in 1858. The minister was 'a man of cultivated mind, of a deportment becoming his high calling, and of a conversation that savoured of the things of Christ'. His wife was Christian Guthrie, daughter of the Rev. Alexander Carnegie, minister of Inverkeilor.

John Kirk as a young doctor.

The youngest John was he second of four children, born 19 December 1832 and must have inherited much of his iron-clad morality from his parents. The only other sibling who seems to have attained any prominence was his elder brother, Alexander Carnegie Kirk, born in 1830. He became a noted naval engineer, but unlike John did not take part in any kind of public life, dying in Glasgow in 1892.

The explorer's eldest brother.

Early Career and Into Africa

Kirk qualified as a doctor and went on to serve in the Crimea War in 1855. (His interest in botany was evident in Edinburgh, where he studied in the faculty of arts at first before switching to medicine.) Learning Turkish, he travelled widely in the Middle East, mainly pursuing botanical interests. His most significant appointment was that of a naturalist accompanying the famous David Livingstone on an expedition to east Africa in 1858. This second expedition of Livingstone's, exploring the Zambesi region, did not go entirely smoothly. Livingstone was no great communicator and preferred either his own company or that of native Africans. His brother Charles was also part of the party and was a more petty character than David, arguing with colleagues and dismissing some of them. Kirk generally got on tolerably well with Livingstone - both were doctors and of course Scots - and also accepted his plans and decisions even when these looked ill-judged and even foolhardy. But Livingstone, driven by instinct and his own demons, was at times looked upon as a madman by his younger colleague. On 18 April 1874 he was one of the pall-bearers who carried Livingstone's coffin into a funeral ceremony in Westminster Abbey. (This was despite the fact that Livingstone's chief mythologiser, Henry Morton Stanley, tried his damnedest to blacken's Kirk's name on the false basis that the doctor had not done all he could to assist the great man in his last expedition.)

John Kirk returned to Britain in 1863, but three years later he was back in a different part of Africa, appointed as a medical officer in Zanzibar. He soon became Assistant Consul and then Resident. He had been appointed Consul in 1873, succeeding Henry Adrian Churchill, who had been actively working towards the abolition of the slave market on the island. Churchill's health broke down to such an extent that Kirk advised him to return to the U.K. in 1870.

The final defeat of the slave trade in the island was accomplished by Kirk's astonishing guile and nerve. While the years in which he served primarily as a doctor in the consulate were quiet and he took no active part in public life or against slavery, there was one incident which marked him out as a risk taker. This was in 1866 when he joined in the successful attempt to smuggle the sultan's sister out of the territory. Seyidda Salme had become pregnant by a German and was at risk of death if she had remained in Zanzibar. For much of the time, Kirk pursued his own interests in Africa, collecting information about botany, trade, slavery, in an even handed and non-judgemental fashion. More of a pragmatist than the strange visionary Livinstone, he was caught between the rock and hard place of the British government and the East India Company, which often had differing ideas about slavery and much else. In 1873 he was put in an invidious position of receiving two contradictory instructions from London. The first ordered him in no uncertain terms to give the Sultan the ultimatum that he should close the slave market and cease all trade in slaves, or else the British government would blockade the island. The second order warned Kirk that no blockade was to be enforced, for fear that it would drive the territory to crave the protection of the French. Kirk only showed the first communication to the Sultan, with the result that Barghash caved in within two weeks and the slave market was closed forever.

Despite the best efforts of Kirk and his successors, slavery actually surreptitiously survived the closure of Zanzibar's public slave market. Special Commissioner Donald Mackenzie visited the island and its neighbour Pemba in the last decade of the 19th century and found that slavery was still flourishing in the agricultural estates:

In Zanzibar a good many people had been telling me how happy and

contented the Slaves were in the hands of the Arabs; in fact, they would

not desire their freedom. At Chaki Chaki I walked into a tumble-down

old prison. Here I found a number of prisoners, male and female,

heavily chained and fettered. I thought surely these men and women

must be dreadful criminals, or murderers, or they must have committed

similar crimes and are now awaiting their doom. I inquired of them all

why they were there. The only real criminal was one who had stolen a

little rice from his master. All the others I found were wearing those

ponderous chains and fetters because they had attempted to run away

from their cruel masters and gain their freedom— a very eloquent commentary on the happiness of the Slaves!

The British Consulate, Zanzibar.

Kirk's Later Years and Legacy

Kirk returned to Britain finally in 1886, settling in Kent. His awards included the K.C.M.G., G.C.M.G., K.C.B., plus the Patron's Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society. The welfare of Africa still concerned him and in 1889-90 he attended the Brussels Africa Conference as British Plenipotentiary. In later years John Kirk grew progressively blind but he maintained his interest in the natural world. He died at the age of 89 and was buried in St Nicholas's Churchyard in Sevenoaks. Among the tributes paid to him was one by Frederick Lugard, Governor General of Nigeria: 'For Kirk I had a deep affection which I know was reciprocated. He was to me the ideal of a wise and sympathetic administrator on whom I endeavoured to model my own actions and to whose inexhaustible fund of knowledge I constantly appealed.'

Substantial records survive concerning Kirk, including the journals he kept on the expedition with Livingstone, Apart from that there are his contributions and discoveries in zoology, biology, a substantial corpus of photographs(over 250). He maintained close connection with Kew Gardens until his death. The Kirk Papers have been secured for the future in the National Library of Scotland. As far as I know, there is no memorial to Sir John Kirk at Barry, but if not, there definitely should be.

Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayyid Sir Barghash bin Sa'id (ruled 1870-1888).

Selected Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Kirk_(explorer)

John Langlands: An Aberlemno Slave Owner

C. F. H., 'Obituary: 'Sir John Kirk,' Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygeine, volume 15, issue 5-6 (15 December 1921), p. 202.

Hazell, Alastair, The Last Slave Market: Dr John Kirk and the Struggle to End the African Slave Trade (London, 2011).

Low, James L., Notes On The Coutts Family (Montrose, 1892).

MacGregor Peter, David, The Baronage of Angus and Mearns (Edinburgh, 1856).

Mackenzie, Donald, A Report on Slavery and the Slave Trade in Zanzibar, Pemba, and the Mainland Protectorates of East Africa (London, 1895).

McBain, J. M., Eminent Arbroathians (Arbroath, 1897).

Scott, Hew, Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae (volume 5, new edition, Edinburgh, 1925).

Wild, H., 'Sir John Kirk,' Kirkia, volume 1 (1960-61), pp. 5-10.

0 notes

Text

Shadow in the Beginning - the First Logie Owner of Glamis

Long before the castle of Glamis was built and even before the ownership of the Lyon family, there were mysteries surrounding the place. From the Dark Age habitation to the royal estate there, the facts are scant enough. One would suppose that the records of the first non-royal ownership of the estate would throw open the history of the place and provide clear information. But history is murkier than that.

In the 1363 the records show that a man named John de Logy received the reversion of the thanedom of Glamis from King David II. The reddendo for these lands was a red falcon which had to be delivered to the king yearly at the feast of Pentecost. By 1372, however, Logy was no longer in possession and the new monarch, Robert II, granted the thanage to Sir John Lyon. The original owner is a shadowy character. The first JohnLogy – or Logie – came to a bad end, executed for his part in a plot against the king. Margaret Logy, who some historians reckon to be his daughter, went on to marry David II. Logy, or rather Logie, is by no means an uncommon place-name in Scotland. There are several such names in Angus – one in north Angus, and another between Dundee and Lochee (though for long incorporated in the city). It likely, however, that this Logy was associated with Logie-Almond in Strathearn, Perthshire. The owner of Glamis was likely the first John's son.

The downfall of Logie senior was his part in a treacherous plot against the king orchestrated by Lord Soulis. Soulis died in Dumbarton Castle. Sir John of Logie, together with several other plotters, were condemned following the ‘Black Parliament’ of 1320 and drawn, hung and beheaded. Incidentally the plot also led to the death of a notable Angus man named David Brechin, who was condemned because he had kept secret the details of the plot, despite refusing to become involved.

Margaret Logie herself presents an interesting character, judging from the facts which have survived about her. She was born into the powerful Perthshire family of Drummond and had a long liaison with King David II, whose marriage to Joan (daughter of King Edward II of England) was both childless and unhappy. When Joan retired to be a nun in England, David took a series of mistresses, one of whom was murdered by Scottish nobles who were suspicious of her power. After Joan’s death, Margaret Logie became the first Scotswoman to marry a reigning Scottish monarch since the 11th century. Margaret was a powerful lady and an active force in Scottish politics.

King David II of Scotland and Edward III of England.

But her downfall may have been sealed by the fact that she was unable to give the king a son (though she had one son by her first husband, also called John Logie and one possibly malicious chronicler later accused her of pretending to carry the king’s child). Margaret tried to secure her position by making a bond with the powerful Kennedy kindred of Carrick, but she still fell out of favour. King David annulled the marriage, but his queen appealed to the papacy. The matter was still unresolved when King David II died in February 1371. But Margaret died on her way to the papal court at Avignon soon afterwards.

The Drummonds of Stobhall, Perthshire, interestingly provided another Scottish queen, in the shape of Annabella Drummond. She was the daughter of Sir John Drummond, who was Margaret Logie’s sister. In contrast to her unfortunate aunt, Annabella’s union was a resounding success, at least if it can be measured by its duration; she was married to King Robert III for over 35 years.

Stobhall, home of the Drummonds.

Did Margaret Logie ever visit Glamis? It’s doubtful, but then again Glamis is not too many miles east of her ancestral home of Stobhall in Perthshire. One thing is certain: that she has her place among those many characters in Scottish history whose reputation has suffered as a result of her strong character and motives. John Bellenden, translating the history of Hector Boece in the 16th century, sums up the distorted tradition of this queen which survived in his era:

King David...maryit ane lusty woman, namit Margaret Logy... and within thre monethis eftir; he repentit and wes so sorrowful that he had degradit his blud-rial with sic obscure linnage...

Sources

Guthrie, James Cargill, The Vale of Strathmore, its Scenes and Legends (Edinburgh, 1875).

McPherson, J. G., Strathmore, Past and Present (Perth, 1885).

Penman, Michael, ‘Margaret Logie, Queen of Scotland,’ in The Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women, From the Earliest Times to 2004, ed. Elizabeth Ewan, Sue Innes, Rose Pipes, Sian Reynolds, pp. 248-9 (Edinburgh, 2006).

Riddell, John, Inquiry into the Law and Practice in Scottish Peerages (vol. 2, Edinburgh, 1842).

Stewart Allan, A., ‘Historical Notices of the Family of Margaret of Logy, Second Queen of David the

Second, King of Scots,’ Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 7 (1878), pp. 330-361.

0 notes

Text

Fairs and Markets of Angus

The last post about fairs and markets covered some information about the fairs in Dundee, Forfar, Glasterlaw, Glen Esk and some others. This post looks in more detail about the famous Taranty Fair at Brechin, plus the markets of Arbroath – and other information.

Taranty Fair, Brechin

Taranty (Trinity) Fair was a very renowned fair and cattle market held on the common at Trinity near the burgh of Brechin. These days it still exists, but as a palimpsest of its previous existence, being held on the first Tuesday after the second Monday in June. It was different in the mid 19th century, as recalled in an article which included contributions by James Grant (whose father farmed at Clochtow, Forfar) in the Brechin Advertiser, 25th June 1929:

Then the Market ran for three days on Wednesday for sheep, Thursday for cattle, and Friday for horses. For a month prior to the market advance parties were in Brechin and district fixing up lodgings and getting accommodation for the large number of animals that were forward for the market, and after the fair was over it was some time before the town was cleared, for the attenders sometimes enjoyed themselves not wisely but too well… At the market the Town Council, being superiors of the fair, attended, and the constabulary, it appears, were then nominated by the trades or guilds of the city. From contemporary reports their services were not highly thought of, for a writer in the “Brechin Advertiser” in 1854 complains that instead of taking their proper positions throughout the market, they hung about Justice Hall…

But on the whole the great fair seemed to pass off well, and if there were thimblers and pickpockets about the public were usually well warned… Compared with old days the market was now a shadow if what it used to be. The readier of access which people had to the towns, and development of transport had taken away the usefulness of those gatherings.

But however much the market had dwindled since its Victorian heyday, it was still a red letter day for agricultural workers in Angus and beyond well into the 20th century as one contributor to Bothy Nichts and Days (p. 44) recalled:

Fowk biket fae a’ ower Angus and the Howe o’ the Mearns tae ging tae it. Some hardy ploomen wid hae a goe at the boothboxers but it wisna offen they cud beat them, they a’ had nesty tricks, it wisna exactly Marquis o Queensberry rules. The Toon Cooncil held coort in a hoose aside the muir and onybody gettin oot o hand wis fined on the spotor spend a nicht in the cells. Ye wid get the eftirnuin aff for the local show, like the Fetterie show, aye held on a Wednesday.

Despite the centuries long record of fairs and markets associated with Brechin, most recorded change occurred throughout the 19th century, partially to reflect changing patterns in local farming. (David Black, the historian of Brechin, documented these developments.) An act of the council, dated 25th March 1801, responded to local livestock dealers and farmers asking for a Trinity Muir spring market to be held on the third Wednesday of April, and this was first held on 15th April of that year. The council established a new market – or ‘Tryst’ – in 1819, and this new date was appointed to be held on the Tuesday preceding the last Wednesday of September every year. Again this was at the behest of the local farming community. By 1833 the August Lammas Muir had ‘dwindled to a petty fair’ and further changes were instituted.

By the time David Black was writing the various fairs and markets of Brechin were still thriving, albeit those merchants who traded there were no longer the same. Tuesday’s market was for grain, though there were cattle markets on that day in autumn and winter, with horse markets in February and March. The great annual markets deserve to be described in detail as they capture a vanished mode of life:

The first Tuesday after Whitsunday, old style, is a great market day, chiefly for the hiring of country servants; and so is the first Tuesday after Martinmas, old style... Formerly these term markets were attended by chapmen, who formed a society amongst themselves, termed “The Chapmen of Angus”... These chapmen travelled in the country regularly, carrying their goods some in spring-carts, some on horseback... an inferior class, called packmen, travelled always on foot, and some of them carried immense packs on their backs... As the chapman waxed old and wealthy, he settled down as a merchant in some borough town. The race is now all but wholly extinct. On a piece of ground of nearly 33 acres in extent...called Trinity, or more generally Tarnty Muir, a great fair is annually held for three days, commencing on the second Wednesday of June, to which cattle-dealers and horse-dealers resort from all parts of Scotland and some parts of England... There are other markets held on this ground in April, August, and September, but the June market is par excellence termed “the Trinity Fair”. The April market, called the Spring Tryst, generally a large market, is held on the third Wednesday of that month...

The size, dignity and importance of the markets on Trinity Muir was enforced zealously by the city’s officials and seems to have be a customary feature from early times, as again described by Black:

Every one who has witnessed the fairs... has noticed the array of halberds with which the council are guarded to the markets, and by means of which, when necessary, the decisions of the magistrates, given in the markets, are enforced. The guard is furnished by the incorporations of the town, each sending two men at Trinity fair, and one man at Lammas fair. The weapons with which the men are armed belong to the respective incorporations...

Black then records an event in May 1683 when two of the guard staged a mutiny, one of whom was a noted troublemaker named David Duncanson who had come to the attention of the authorities several times before.

Records of Brechin’s markets stretch back to the reign of William the Lion (1165-1214) and beyond. A charter of William’s confirms a grant to the bishop and Culdees of the church of Brechin giving the right to hold a Sunday market. This confirmed a grant made by King David I and is repeated in later charters issued by Robert I and James II. The charter granted by David II in 1369 notes that the whole merchants inhabiting the City of Brechin had free ingress and egress to the waters of the South Esk and Tay for carrying their merchandise and prohibits the burgesses of Dundee and Montrose from interfering with these rights. The weekly market was moved from Sunday to Tuesday in the time of James III in the late 15th century. The Trinity Fair is first mentioned in records in the late 16th century.

St Thomas’ Fair in Arbroath and Auchmithie

By way of contrast to Brechin’s high days, we can look at the festivities surrounding the fairs and markets on the coast at Arbroath, memorably described in J. S. Neish’s In the By-Ways of Life (p. 57). One of the features of the celebration of St Thomas’s Day was an exodus of Arbroath folk along the coast to the village of Auchmithie. Lucky Walkers was the name of a famed hostelry in the fishing village. Neish describes the annual outing:

By an early hour the lads and lasses streamed out of town by the cliffs or Seaton Road... At the foot of the brae [in Auchmithie] there stood a huge barn-like building, which was used as a fish-curing house. On these festive occasions this shed... was extemporised into a ballroom... During the whole day the fishermen made short trips with their cobles round the small bay with freights of screeching half-frightened women, who eagerly invested their spare coppers in a sail.

The author tells us that Lucky Walker herself and her staff were run off their feet all day, bringing fish and ale to the incomers. But, like other honoured customs, progress put an end to the trade. The coming of the railways meant that Arbroathians went further afield on their festive days and Lucky observed that ‘sin thae railways began her hoose was nae worth naething’.

By the late 19th century (according to the author of Arbroath, Past and Present), the market of St Thomas had practically ceased to exist. But in former times this ‘Auld Market’ was held on the 18th July, if a Saturday, or the first Saturday thereafter. Not just Auchmithie was a destination for holiday makers; locals also went to Lunan, East Haven, even Dundee.

The history of the fairs and markets in Arbroath provide an exemplary guide to the changes which also occurred in other locations, for, although markets and fairs were a constant in communities for centuries, local needs frequently dictated changes. King William the Lion granted the right for Arbroath to hold a weekly market in the late 12th century, on Saturday. The burgesses in 1528 chose Tuesday as the new market day. By the time of the charter of James VI in 1599 the market was again being held on a Saturday and there were four annual markets: St Thomas’s Day, St Vigean’s Day, St John’s Day, and St Ninian’s Day. Two hundred years later the Old Statistical Account noted that there were three yearly fairs: 20th January (St Vigean’s), first Wednesday after Trinity Sunday (St Ninian’s), and 7th July (St Thomas a Beckett). The weekly market day was now Thursday (to which day it had been changed around 1742). By the time of the publication of the New Statistical Account in 1845 the fairs had shrunk to two in number and the weekly market day was once again Saturday. Late in the 19th century there were hiring markets held on the last Saturday of January, 26th May, 18th July, 22nd November (if these dates fell on Saturdays; if not, the Saturdays following).

Feeing Markets