Text

"Just because you are soft doesn't mean you are not a force. Honey and wildfire are both the color gold."

- Victoria Erickson

340 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We are afraid to care too much, for fear that the other person does not care at all.”

— Eleanor Roosevelt

17K notes

·

View notes

Text

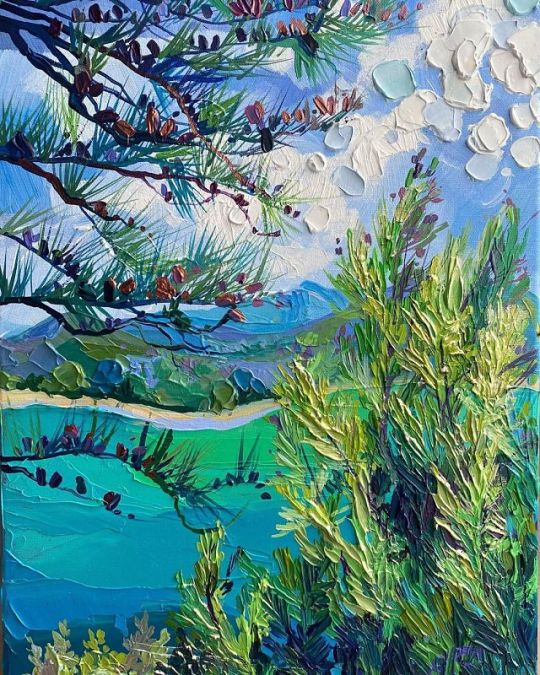

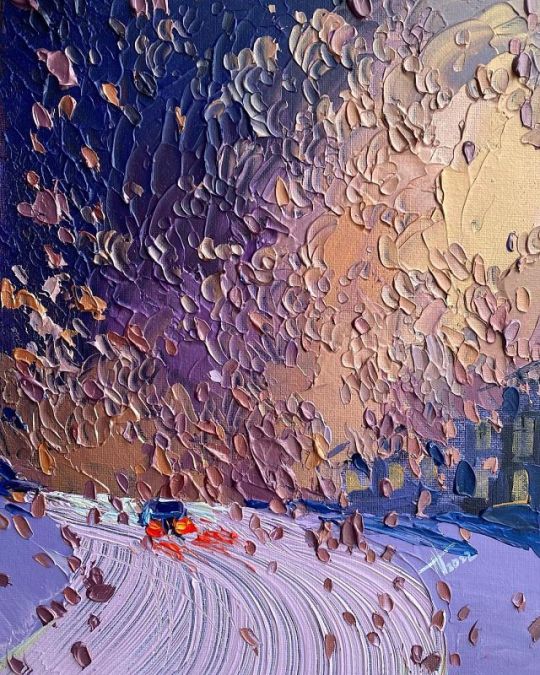

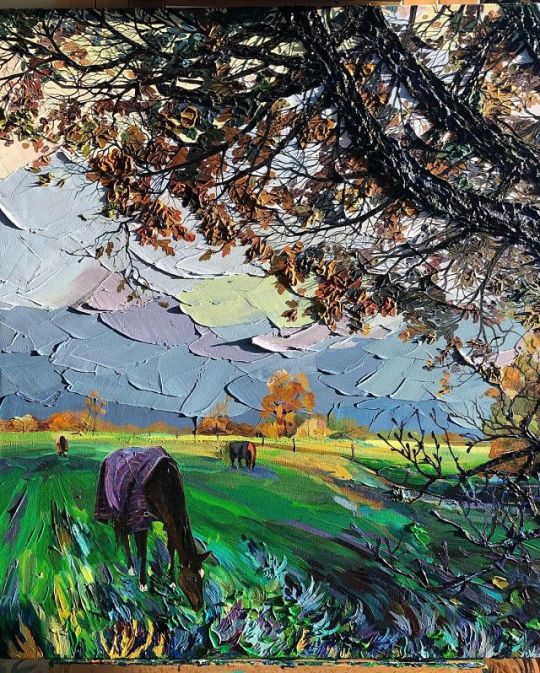

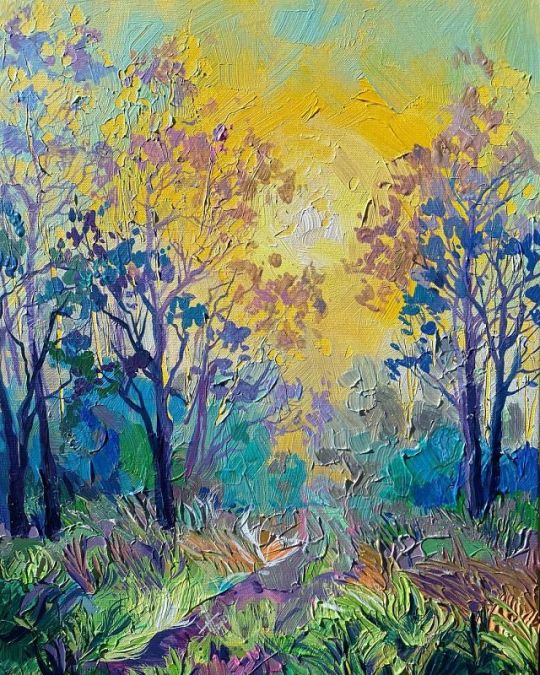

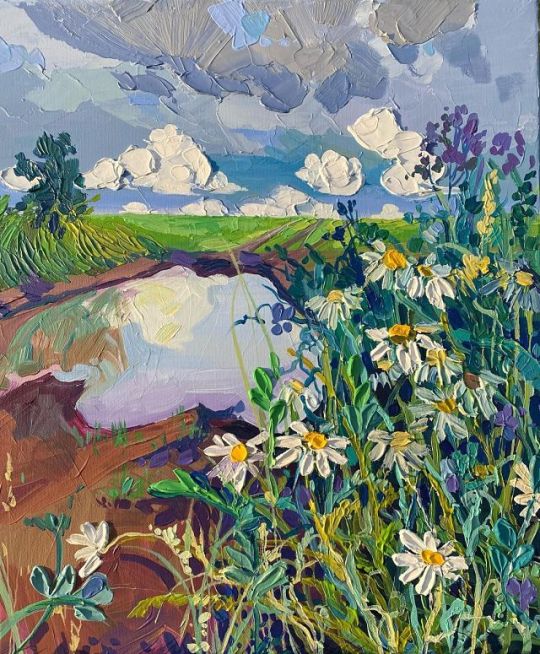

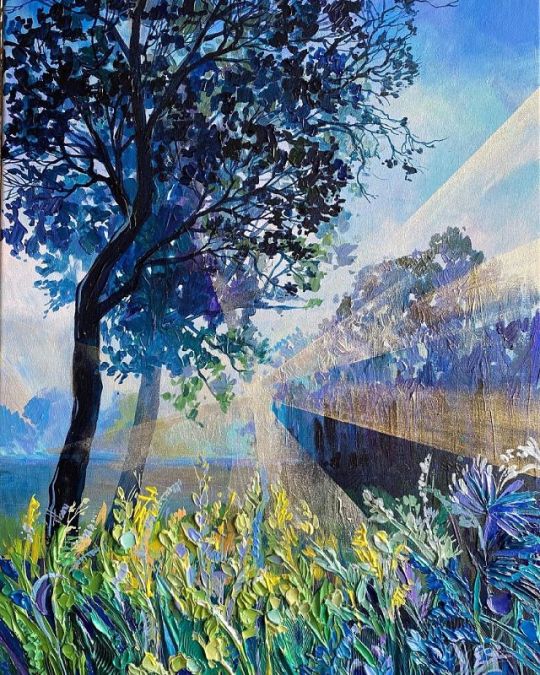

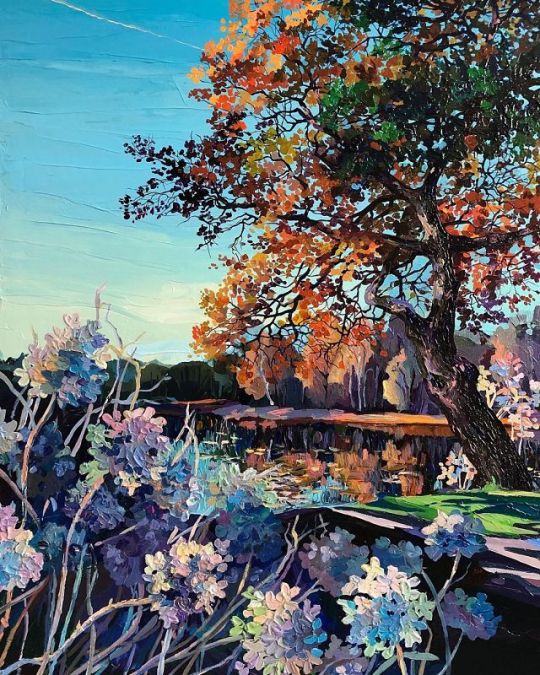

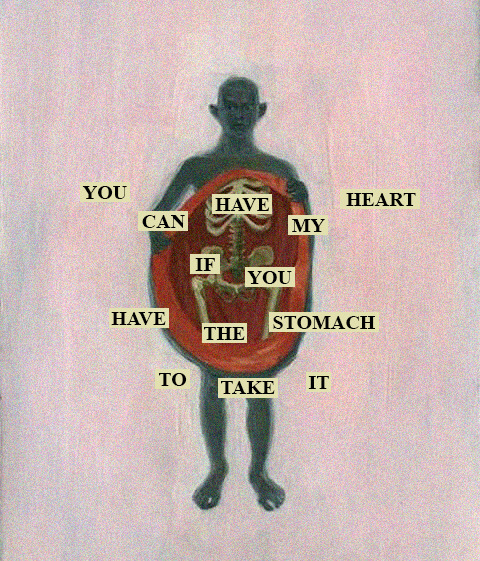

I’ll steal a kiss from you like a naughty angel, even if it’s the last of all my kisses. Paintings made by: Anastasia Trusova.

8K notes

·

View notes

Text

i want ads to feel pain when i skip them btw

133K notes

·

View notes

Text

praying for my girlies rn 🙏🙏 nothing but love n support from the gay community 💜

Girls will be like Idk why im so unproductive recently and then you ask whats going on in their life and they list eight lifestopping crisies and then say 'yeah but i should be fine :/ '

207K notes

·

View notes

Text

“I hope that one day someone will make flowers grow in even the saddest parts of you.”

— vacants

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

In every wood in every spring there is a different green.

110K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Take wrong turns, talk to strangers, open unmarked doors. And if you see a group of people in a field, go find out what they are doing, do things without always knowing how they’ll turn out.”

—

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Some old wounds never truly heal, and bleed again at the slightest word.”

— George R.R. Martin, A Game of Thrones

8K notes

·

View notes

Photo

“I know that I never… uh… I never really said it before… but… I wanna be with you.”

12K notes

·

View notes

Text

I was recently commissioned to write a piece about two books by Charles Moore, The Black Market: A Guide to Art Collectingand The Brilliance of the Color Black: Through the Eyes of Art Collectors. The books offer a panoramic view of the world of art collectors and the Black Market—art made by Black artists. Whether or not you know anything about collecting art or the Black Market, these are fascinating reads, especially in the modern climate.

But this isn’t quite the topic on my mind today. Whilst reading the books, I came across a couple of quotes that stopped me in my tracks and got me thinking:

“[Artist] Biggers welcomes differing opinions—stating that, as an artist: ‘if everyone agrees in the positive or just the negative, then something hasn’t worked’.”

And:

“As an artist, Nina Chanel Abney revealed that she’s ‘intentional about creating work that gets a mixed response’.”

I previously wrote about negative reviews and how, as writers, we can learn to look at getting a negative review on our work in a positive light. But the perspective I was taking was purely in terms of writing the book you want to write, and then dealing with a negative review as a sort of inevitable and unfortunate aftermath. Coming across those two passages in Moore’s work got me considering the topic in a whole different light:

More than just learning to deal with bad reviews… Should we aim to create work that is going to generate mixed reviews in the first place?

We can’t please everyone, sure. But should we actually actively make sure to displease some of our readers?

Art as a vessel

Since the very beginning, art has been a vessel, a vehicle to convey messages to the public. Artists have always used their art to share their views of the world and the societies they live in. They portray their vision of the world. And since that in itself is subjective, the output is bound to be divisive.

The same is true for every book we write and tale we tell. The most seemingly innocuous stories out there convey messages, not just in terms of what is said, but how it’s said, too. They’re a mirror for the writer’s views, perception of the world, a reflection of their values and inclinations. Again, all very subjective things, which aren’t going to be everyone’s cup of tea. For Charles Moore, that’s a good thing:

“A good artist”, he states in The Black Market, “can make interesting works. They can hold an audience’s attention for a certain period of mind. The great artists, however, can make interesting art while being conscious about their subjectivity and relationship with the world around them. Great art isn’t just about the aesthetics; it is a highly critical intellectual activity.”

Working those ‘little grey cells’

In that case, as writers, we must learn to look at the creative process in a different light. It’s about telling the stories we want and need to tell, yes, but it’s also about being aware of the messages—conscious or unconscious—we weave into our work, and the people at the receiving end of those messages. It’s about leaving those messages open to interpretation, and welcoming anyone’s differing opinion from the outset. Because, if someone disagrees, it means it’ll have made them think about our work enough to ponder the matter and form a view of their own.

With that in mind, far from wanting everyone to leave a five star review, we should aim for our readership to interpret the stories we write in their own way and to think about them critically. In short, we want them to think, to reflect, to use their ‘little grey cells’ (and kudos to those of you who got the Hercule Poirot reference!).

As Charles Moore says in The Brilliance of The Colour Black: “Refusing to restrict herself to just one material, medium, message, or cause, [artist] Nina Chanel Abney explores the universes of fine art and commercial art as she embarks on a mission to share her art through every medium necessary to find—and provoke—her audience.”

I like that. From that vantage point, our mission as writers is no longer to please others, or simply to express ourselves, but also to provoke a reaction in our readers, and to welcome the positive and negative feedback with the same satisfaction, that of having done our job well.

Art as a conversation starter

Is that not just angsty, some of you might ask? Can’t anyone just create something for the pure joy of manifesting a piece of work into existence, without any ulterior motive?

Of course we can. But even those apparently inconspicuous pieces reveal a lot about us as writers, our experiences and our views of the world. And that alone sends a certain message, whether you like it or not.

Similarly, when you chose to tackle a topic in your writing voluntarily, just because you convey one particular message in one piece of work doesn’t mean you have to stick to it forever or in the same manner.

In The Brilliance of the Colour Black, Moore goes on: “Abney reveals that she wants viewers to have a “personal relationship” with her artwork, so she tries to avoid being pigeonholed or associated too strongly with one particular cause or message. By making the events and figures depicted in her work somewhat inscrutable, she accomplishes open interpretability for the most part.”

And, ultimately, what is ‘interpretability’? It’s leaving things open-ended. It’s allowing others to take what you create and read it in any way they wish. It’s having people who’ll love your work and people who won’t, and people who’ll get it spot on and people who just won’t see your point, or read it completely wrong. And some who’ll write good reviews and some who’ll trash your book for everything they hated about. But… (Yes, there’s a but, and a good one at that!).

Even for someone to trash your book with passion they’d have to think about it enough to evaluate why they hated it. They’d have to have that conversation with themselves about what it was in the book that didn’t work for them. And, in the process, it’d have made them think, deeply, profoundly about your work and what you were trying to achieve. It’d have them exploring their own understand of the world and challenging their views of particular scenarios. In doing that, regardless of where they land with your work, little by little, they’ll end up expanding their horizons.

And that alone, in my view, is quite a win.

Disruptors make the world go round

If you’ve read some of my previous articles, you may know where I’m headed: what now? What does this mean for us writers? Have we failed if we don’t get our readers to intensely weight the ins and outs of our work after they’ve read it?

Absolutely not.

What I am saying however is that we should be conscious of the messages we convey in our writing, whether we want it (or know it) or not. And we shouldn’t shy away from people disagreeing with what we’re saying or how we chose to say it. We should aim to step away from that stigma of bad reviews, that more common approach that says something like ‘getting a bad review means you’re worthless as a writer and your work sucks and you should hide in a hole and never write another word again’.

Instead, from the moment we put the very first word of any WIP down, we should embrace the idea that some people will strongly dislike it. That some readers will disagree with any (or all) parts of our work. We should welcome those reactions. Better even, we should hope for them wholeheartedly.

It’s easy to receive praise, or to get someone to agree with you who’s pre-disposed to like your work. What’s not that easy, on the other hand, is to be a disruptor. To get someone who’s not on the same page as you to consider your work and articulate an opinion, even if at the end of the day their view on the topic still differs from yours.

So here’s my challenge to you (and to myself): next time you sit down with your WIP, or read a negative review on your work, or come across someone disagreeing with something you’ve written… Force yourself to step away from that downward spiral of self-doubt and self-criticism. Instead, congratulate yourself on a job well done.

In a world where people’s attention span averages a few seconds, where original thought has been nearly eclipsed by avalanches of pre-digested and oversimplified content, it’s our duty as writers to help readers reclaim their critical thinking powers, to help them re-learn how to make their own opinions, one word at a time.

58 notes

·

View notes

Photo

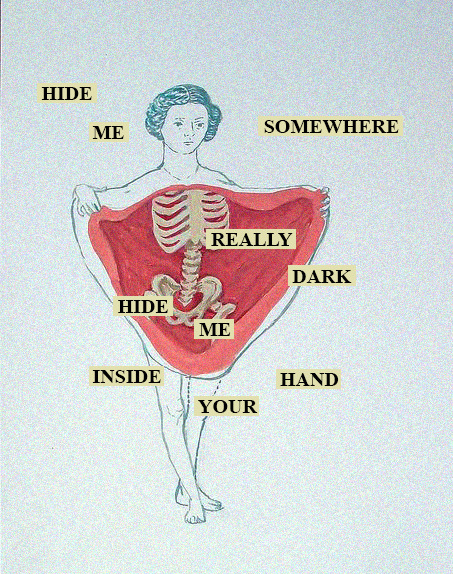

aleksandra waliszewska // yves olade // joy priest, horsepower // richard siken, wishbone

46K notes

·

View notes

Text

“Its a frightening thought, that in one fraction of a moment you can fall in the kind of love that takes a lifetime to get over.”

— Beau Taplin

7K notes

·

View notes