𖥦 ヽ♥︎ FEM Newsmagazine talks NOSTALGIA /✿ ★☆ Table of Contents - Editors Note - Staff List

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Note

tbh: i think this blog is really cool. rate: bms 😳

so true

0 notes

Text

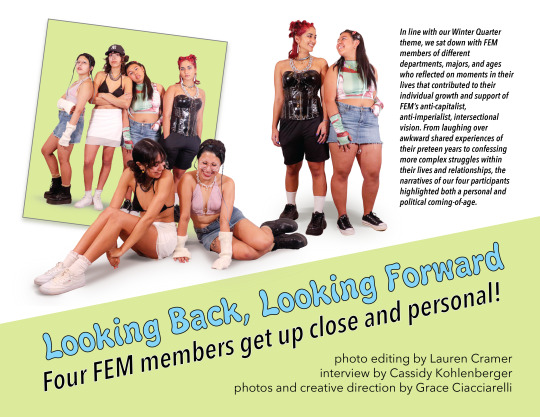

Looking Back, Looking Forward: Four FEM members get up close and personal!

photo editing by Lauren Cramer, interview by Cassidy Kohlenberger, photos and creative direction by Grace Ciacciarelli

0 notes

Photo

Saccharine Cane

by Ashley Leung, design by Katelynn Perez

On the second floor of an apartment building near Jiandong street lived a family: yeye, laolao, and their four-year-old granddaughter Yingying.

Xi’an, China. 2005.

“Don’t let her eat it, it’s too tough,” Mom’s voice chimed from the kitchen.

Grandpa murmured with reassurance. The blade of a knife thudded against wood. Chop. Chop.

Chop.

He emerged from the kitchen with a metal bowl. I watched him as he walked to the water dispenser, pulling the red tab down. Red was for hot — off limits to me. Steaming water filled the bowl.

My legs dangled idly from the wooden chair propped against the narrow, white wall between two doors. If you look closely, you could distinguish the pen-marks carefully etched along the left edge, marking my cousins’ heights throughout the years. There was no mark with my name yet; I was too short.

Gan zhe, gan zhe, I heard them say when Grandpa entered through the front door, carrying a long, green stalk. He had bought fresh sugarcane from the market.

The bowl came over, and I peered into it. One-inch chunks floated in warm water. Grandpa’s hand plucked one out and held it to my mouth. My baby teeth bit into it, barely making a mark on the firm fibers.

“It’s too tough,” Grandpa concluded as I futilely gnawed the chunk.

“I told you,” Mom said with a tinge of exasperation. “Don’t let her eat it. It’s going to ruin her teeth.”

Grandpa murmured, “I’ll try cutting it into smaller pieces.”

I sat, waiting some more.

When he reemerged, the chunk had turned into slivers. I bit into one, this time thoroughly chewing.

It was sweet.

***

Do you ever wonder why you remember something?

Fruit by the Foot was my favorite candy growing up. Cherry Jolly Ranchers were a close second. I got a kick out of the bright food coloring, artificial flavors, and teeth-aching sugariness; I wanted Red 40, Yellow 5, Blue 1 running through my veins.

By the age of three, I already had rotting teeth (according to my mom) because my grandparents spoiled me and let me drink sweetened milk, chew White Rabbit candies, and eat lollipops. I would dance to supermarket music and point at bubblegum next to the cashier counter. Grandpa and Grandma never denied me.

I don’t remember any of that.

In my memory, sugarcane was my first candy. And Grandpa was my candy-man.

Sometime between middle school and high school, I went through a teen-angst phase, a searing female empowerment phase, a Twilight-fanatic phase, and a write-cigarette-and-whisky-poems-about-your-unrequited-crush phase — all at once.

I was rigid and girl-bossy. I had the urge to do everything myself, just to prove that I can — just to prove that I am.

When I struggled with calculus or chemistry, when I couldn’t carry a 50 lb. bag of jasmine rice, or when I couldn’t resolve all the technical difficulties at home, I spiraled into self-contempt not because I was failing as an Instagram girl boss but because I couldn’t prove my dad wrong with his explicit preference for sons over daughters. “If only you were a boy” is a traditional thought, passed down like an heirloom. No amount of incels online could overpower the culprit in your own home.

At 14, I mistook my painful self-awareness for the peak of maturation. I wanted to find the hidden lessons behind all the memories I had taken for granted; to understand the adults in your life is to become an adult yourself.

So, Grandpa’s sugarcane morphed into a lesson: sweetness comes from hard work. Grandpa had to peel it, chop it, slice it, soak it, and I had to wait… wait… wait for it.

But I’ve waited for things, I’ve peeled, chopped, sliced, and soaked my way through school and work. The fruits of my labor — a part-time job, an academic award, a published article — were sweet for about a week. UCLA was sweet for two weeks. Then, it dissipated.

Waiting on my wooden chair, I don’t recall feeling any impatience — only tender curiosity. Chewing on my sliver of cane, I don’t recall my heart swelling with gratitude for Grandpa’s relentless efforts — only subtle satisfaction as the chewing led to sweetness.

High-fructose corn syrup is the top ingredient in many of the candies I love, but its sweetness dissipates and leaves me craving the clean bite of sugarcane. In this highly individualist society, my facade of emotional independence, girl-boss strength, and self-help has become high-fructose corn syrup — artificial and transient.

Let me be strong, I had declared at 14, envisioning myself power-walking through corporate doors, voluminous hair flying back, Hermes Birkin in hand.

No, let me be vulnerable again, I correct myself at 20. Perhaps I can have all that, but I don’t need all that. Perhaps “strong” means the soft resilience of water, the tough fibers of a sweet plant.

***

If I could encounter a stalk of sugarcane again, I would soak it in warm water and chop it into one-inch chunks. Chewing and chewing, I would taste the same subtle sweetness reminiscent of toddler innocence and serenity. I would exclaim to my empty kitchen, but really to my Grandpa, “Look! It’s not too tough for me now.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Revisiting Cola Chicken Wings

By Haiqi Zhou

Mom: “I played card with your dad yesterday. We played 5 rounds and I won a thousand RMB!”

She started laughing.

Dad: “Your mom had the best luck.”

Mom: “I don’t know if it was my luck or if your dad was letting me win.”

Dad: “Every time I had a good hand, your mom had a better one!”

After calling my parents on New Year’s Day, I realized suddenly that I haven’t been home in more than two years. The city that I grew up in has become so unfamiliar, so distant. I constantly struggle with the thought that my country does not want me back. And it could be true. Chinese international students are stuck between the worsening US-China relations, between racism in the States and criticism of Chinese netizens. “Don’t bring COVID back to China,” they would say. “Go back to China,” they would say. In the midst of all this, food is my purest memory of home.

While talking with friends about our parents’ cooking the other day, I thought about the food my mom used to make and started crying. I was reminded of the feeling of going home after school to a table of mouthwatering dishes. During dinner, my mom would always ask me: “Did you have a good time at school?” I would mumble yes while devouring a Cola chicken wing with my second bowl of rice (I was still growing). Unsurprisingly, the thought of food from home has become the biggest trigger for the girl who finds herself stuck in the U.S. What is the past tense of food? In our memory of food, is there a smell? Is there a taste? I decided to ask my mom for her recipe of Cola chicken wings, one of my favorite dishes, also a combination of the U.S. and China. Here it is, a taste of my home.

Recipe for Cola chicken wings

Clean about 1 pound of chicken wings and cut two vertical slices on the surface of each wing, put the wings into a bowl for the next step.

Now, you will make a marinade and pour it into the chicken wing bowl, start with 2 tbsp soy sauce, 3 slices of ginger, and 1 tbsp Chinese cooking wine, 1 tsp salt, and 1 tbsp of dark soy sauce (optional). Mix the marinade and wings throughout, and let it sit out for two hours.

After two hours, heat your pan/wok with 1 tbsp of cooking oil and 3 slices of ginger, cook until the ginger aroma fills the air.

Then, put the chicken wings in a hot pan/wok and fry them for two minutes with medium heat.

Next, pour Cola (I recommend the brand Coca Cola) in the pan/wok until the wings are fully submerged. If you are feeling fancy, you can add star anise and chili flakes in for additional flavor.

For the final step, place the lid on your pan/wok and put the fire at medium heat to boil. Once it is at a boil, lower heat to allow it to cook for 10-15 minutes. As it cooks, you will see the Cola caramelize. After 10-15 minutes, it is ready!

Here is my taste of my home to yours, I recommend enjoying your wings with some white rice! :)

0 notes

Photo

The Colonizer Wants You To Forget: Abolition, Memory, And Escaping The Wake

by Jamie Jiang, design by Lauren Cramer

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, a Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg native scholar, wrote in 2008:

“Too often in contemporary times we are presented with a world-view that renders us incapable of visioning any alternatives to our present situation and relationship with colonial governments and settler states. Indigenist thinkers compel us to return to our knowledge systems to find answers.”

I read this quote in a class when Simpson was just finishing her lecturing career at UCLA. At the time, I had just started my first longterm project, a three-episode podcast about campus police abolition. I was thinking almost daily and nightly about abolition; about “visioning any alternatives to our present situation.”

When you’re an abolitionist, most people have skepticism about your “vision”. They ask if you have any workable plans for a post-abolition world. They ask what happens to psychopaths, what happens to traumatized people, what happens to jobs. The constant questions, the opposition, and the rhetoric churned gently in my head. I wasn’t really thinking about abolition in the future, of course. I was thinking of urgent calls for abolition, immediate changes and their fallout, and little revolutions happening right here in my neighborhood.

Abolition’s first directive is to be imaginative.Simpson’s writing spoke to me, urging me to look to pre-colonial knowledge systems to find imaginative answers.

In May of 2020, George Floyd was murdered by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. During that summer, Black Americans and allies internationally protested a history of law enforcement’s brutal violence against their own communities, especially Black folks. My father — an idealistic politics junkie — and I had long talks about the police state and the validity of police.

My dad was a Beijing native and fresh out of college during the Tiananmen Massacre, when thousands of Beijingers occupied a political landmark in China’s capital to demand a democratic system. He rode his bike with his friends from their college to occupy Tiananmen. They jeered at the young soldiers from the national military who waited in their vehicles for something to happen.

He disapproved of how the police treated American protestors. American police treated its protestors with particular brutality this summer – severely and fatally injuring them, stalking and terrorizing them, arresting en masse and tear gassing them.

The young people he protested with were idealistic, healing from a childhood steeped in broken communities, economic inadequacy, and national shame. They expected that the government, which had scooted closer to Western economic practices since the cultural revolution, would warm up to democracy. Instead, in May, the state cracked down on protestors. The military opened fire, and hundreds of people died. My father has that “world-view” Simpson wrote about. He’s resigned, expecting nothing more of the state than the same old brutality.

At Tiananmen, the young protestors knew and communicated with their police officers – Beijing’s a big city, but Beijingers feel this immediate familiarity with each other. Officers promised no violence, perhaps because they could not believe the government would ever hurt its own people like that.

I started a tentative conversation with my father about abolition, fully expecting skepticism. Instead, my father became animated. He leaned away from me and crossed his arms.

“There’s something from old Beijing,” he said, talking about the old capital city culture our ancestors nurtured. “That was community safety.”

Much of my family’s history, like many in China, is marred by the Sino-Japanese war during World War II. At least 14 million Chinese people died at the hands of the Japanese, displacing 80-100 million. Out of all our thousands of prisoners of war, only 56 were found alive when Japanese invaders pulled out of China. Fascist imperialist Japan tore through an already beleagured China, occupying Beijing, our capital, and making history with the horrific genocidal event, the Rape of Nanjing.

Just before the Japanese invasion and for some time after, old Beijing neighborhoods relied on a nosy, bossy elder in the community to visit homes and keep people safe and well. The elder performed safety patrols, usually keeping an eye on things on his strolls and acting as an intermediary. Usually, my father said, signs of domestic abuse brought this elder parading into the shared courtyard to gently reprimand the man of the family. “Hey, why don’t you give it a break,” the elder would say.

When the Japanese invaded, these safety patrol elders took a more diplomatic role. Their negotiation skills and long-built trust with the community helped dissuade the brutal military force from coming to certain doors. That relationship put an odd, twisted layer of manufactured peace between the urban neighborhood and the fascist Japanese colonists.

I have to say, my dad surprised me. I didn’t know the trusting, care-based China he knew. I assumed Beijingers were always just what they are now: just like a Euro-American community when it comes to government, law enforcement, and social hierarchy, just with different language practices and different holidays.

My city had a different relationship with police before colonization, globalization, and the cultural revolution. My ancestors invented ways to look after each other humanely when the state and the invader came to occupy the land. My forebearers’ traditions folded neatly into my own politics. I think it’s not every day that a colonized person can connect their history with their current.

Derecka Purnell writes how her deepening interest in abolition was sparked by the history of marooning tribes of formerly enslaved people and Indigenous folks. Marooners, she wrote, were the “first” radical Black abolitionists in America’s history, and the very first to create communities of mutual aid, self-sufficient horizontal political structures, and non-American governments on American settler soil. Purnell urged us to remember that your ancestors — in your ideological tradition and your bloodline — made sacrifices in their own day for a better, more radical future.

Black and Indigenous people birthed abolitionist thought. Simultaneously, BIPOC are crushed under the heel of the oppressive, violent present. Christina Sharpe wrote that being Black was like being “in the wake” of slavery – the slave ship of empire passes through history, leaving behind a disturbance in the water. Black people today bob and float in the disturbance of the massive, institutional harm founding our society, waters just as rough as though it had just happened yesterday.

History never passes for BIPOC. The dead never die for the colonized body. The same trauma occurs over and over, retraumatizing each generation.

But Sharpe ends her book “In The Wake” by asking readers to “imagine.” Being “in the wake” gives you a special vantage point, from which you can point out a better way to be. She writes, “If we are lucky, the knowledge of this positioning avails us of particular ways of re/seeing, re/inhabiting, and re/imagining the world.” That’s why, as Purnell proves, Black folks founded American abolition. Only the people living perpetually in history are the ones with the power to re/see the past, re/inhabit the present, and re/imagine the future.

That’s powerful. A person in the wake, realizing their history, reclaiming it, and reimagining the world, is a dangerous radical weapon against those in power.

I was at a poetry reading where one Muslim woman performed a tribute to Palestine, her homeland. I remember a line from her poem… she talked about resisting the “invaders who are threatened by memory.” Colonizers, from the United States to China to Palestine, are afraid of BIPOC who remember their history.

This reminded me of a trans friend, who is stepping into a new gender one foot at a time. In the process, they told me, they are starting to view their childhood again, not with the eyes of someone disgusted with what they once were, but with new eyes. Sometimes they’ll tell me an anecdote from their childhood and say, I didn’t realize it then, but maybe it was a sign that I was trans!

Memory works that way – over time, as we are allowed distance from a painful past, the negativity of those memories fades away. In an act of self-preservation, we spare ourselves the energy of feeling the full range of negativity associated with that time in our lives and instead, cherry-pick the pieces that work with our preferred narrative.

It’s a beautiful thing, actually. Ted Chiang, an author, wrote about memory in his lecture “Technology and the Narrative of the Self.” A short story of his asked what the world would be like if we no longer needed to remember events, but trusted a computer to record it all for us in videos. Chiang said that people don’t want the “objective” truth. What people need is a story, because – paradoxically – the story is what brings out the truth. It’s true in many other ways; neuroscientists found that the very act of recalling an event changes the very nature of that memory, so that recalling the memory actually changes the memory itself. Toni Morrison wrote that she could never trust recorded history to tell the truth about slavery; she had to rely on memory instead, or “rememory,” the key to liberation.

The past is, to all of us, a rich minefield for stories about ourselves. Nostalgia is combing over that past and finding particularly affirming stories to tell. Researcher Xinyue Zhou of Sun Yat-Sen University found a biological benefit to nostalgia. Nostalgic people feel warmer in cold temperatures than people who aren’t nostalgizing. Maybe you too, instinctually thought fondly about the past this winter.

One of these days, we will be liberated from the wake, and the repeated shocks and horrors of a colonizing, capitalist, racist world won’t batter us around in its waters anymore. Then, the past will grow distant, and less present, and brim with potential. We will comb over it and find in it the vision of a better future. It may not be nostalgia, but it is a deliberate and a powerful rememory.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Backstage Disney

Disney Adventures, September 2007

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Laurel Hell” as a Journey Through Self Reflection

by Ammi Lane-Volz, design by Hailey Lynaugh

“Who will I become tonight?” asks Mitski on her hiatus-breaking 2022 album, “Laurel Hell.” This question, found in the first verse of track one, establishes a theme for the following songs and the album as a whole. By looking at select tracks in order, “Laurel Hell” tells a story of self reflection and acceptance that the past can be looked upon with fondness.

Her intention of self reflection is set up in the first song of the album, “Valentine, Texas.” The title itself acts as a callback to her previous body of work, as her first post-college album began with the similarly Texas-named song, “Texas Reznikoff.” In both songs, the energy after the first verse transforms completely in one beat and bombards the listener with imagery. However, instead of being explicitly about a relationship, as “Texas Reznikoff” was, her newer song focuses more on the protagonist’s self development. In the second verse, full of southwestern imagery reminiscent of that which underscored her fifth album, 2018’s “Be the Cowboy,” the protagonist takes listeners through a winding drive of figurative language. Dust devils– small and harmless cyclones in sunny deserts– are made by “dancing ghosts” kicking up “clouds of sand” which “look like mountains.” The ghosts can be seen as haunting memories– immaterial things still material enough to dredge up painful particulates. Yet while they are able to conjure objects that appear tangible and terrible to conquer, the mountain-like clouds are simply outlines of what they appear to be. The music shimmers away with the final line: “Let me watch those mountains from underneath/and maybe they’ll finally/float off of me.” All one can do to conquer them is not to reach their summit, but to do the opposite– examine them from a different perspective and wait for them to pass.

The next step in the protagonist’s self reflection journey is taken in the fourth song, “Everyone.” The sounds of this song are ominous, incessant; a foreboding march towards some foretold bad ending. Reflecting on the past, this song’s protagonist sees only pain and regret that was, in their eyes, their own fault. Out of spite or ignorance, the protagonist followed the path in life that “everyone” told them not to go down. And despite the dangers and uncertainty on this new path, they not only “left the door open” to the unknown, but also “opened [their] arms wide” to it, saying to “take it all.” In a foreboding voice, they repeat these lines: “I didn’t know what it would take.” This song could be viewed from a metatextual standpoint to be about Mitski’s own experience in the music industry from a young age. As some of her earlier songs, such as “But Dreaming Costs Money, My Dear,” saw the songwriter grappling with the low financial resources one often gets from being in music, there was likely some uncertainty around being able to survive in her chosen career. Furthermore, she has been involved in this industry for most of her young adult life, self-releasing two albums in the last two years of college, and staying active up until her recent 2018 hiatus. Particularly with her most recent album and the one that rocketed her to indie-superstardom, 2018’s “Be the Cowboy,” her time touring and working in this field shaved off bits of her soul and damaged her ability to have friendships. The title of the song “Everyone” seems to directly reference the newfound popularity she gained through “Be the Cowboy” by playing off the title of the ninth track, “Nobody.” However, while “Nobody” was a song about loneliness and yearning for human connection, with the intense popularity that Mitski gained from it, she now has even more (para)social connections than ever. But this still isn’t true human connection. Rather, she is a product for everyone’s consumption, someone who functions as a “black hole where people dump their feelings.” This feeling of not being able to be human prompted her hiatus from the music industry; however, because of contractual obligations, and because she loves performing, she is still trapped. The song closes out with the lines: “Sometimes I think I am free/ Until I find I’m back in line again.”

As a standalone song, “Everyone” can also be interpreted as a metaphor for the experience of some childhood trauma survivors. This song communicates a corruption of nostalgia. Calls of the childhood game hide-and-seek are warped to communicate danger. Some unspecified thing– innocence, the ability to be vulnerable– was taken from the exploited protagonist during their youth, far more than what they could handle giving. What should have been a pleasant memory of the past and its vulnerability is flooded with bitterness and regret. And despite being the exploited party, comparing themselves to a “babe in a crib/after some big hand turns out the lights,” they still blame themselves for choosing the path that would bring them closest to danger. This victim blaming mentality that often comes from external sources, especially for survivors of sexual abuse, has become internalized for the protagonist.

The next two songs that continue the theme of self reflection are track seven, “Love Me More,” and track eight, “There’s Nothing Left Here For You.” The sounds of the former song are a completely different tempo and feel than “Everyone,” and more closely reflect the danceable mood of some of the other less explicitly self-reflective songs on the album. This is fitting to the theme of the song, as it is about using love as a distraction from internal struggles. High tempo masks the moodiness and compliments the vague distractedness of lyrics like “I wish that this would go away” and “I need you to love me…enough to drown it out.” The lyrics mention an unspecified mistake that the protagonist has been continually making for 15 years; a mistake that has been caused by their desire to not stay “at home.” By staying at home, whether that be a physical place, the stability of a singular relationship, or one’s own body (i.e. having internal validation), they hope to reinvent themselves. But despite whatever they “should” be doing, they still need external validation and love to “fill”, “drown out”, and “clean up” the protagonist. This implies that without this external validation, they are empty, too loud, and dirty. The protagonist seeks to avoid this supposed reality.

But, just like a passing cloud, this avoidance through love cannot last forever. The sounds of “There’s Nothing Left Here For You” are an aftermath– low and droning, almost ambient. The protagonist’s single reason for being is no longer there, whether that be the creation of a career, fulfillment of a goal, or the external validation supplied by an audience. Mitski herself wrote this song just after she played what she announced to be her last show indefinitely. Yet they must decide what to do from here. Reflecting back on their experience, the song’s sounds shift gears, filled with hope and the ecstatic energy of achieving what they devoted their life to, and just as suddenly, it disappears. However, the protagonist is now able to devote their love and attention to other things, like their personal relationships and relationship with themselves.

The penultimate song, “I Guess,” is a song about reluctant acceptance of an ending. The protagonist is almost at a point of acceptance, but the slow tempo indicates mourning.

However, a step further from “There’s Nothing Left Here For You,” the protagonist has reached a point of gratitude. While reluctant to move into a new unknown, they are thankful for the self reflection that this ending has brought about. They believe they will be able to learn how to live without “you”-- whether that be a lover or the music industry. This sentiment rings of another expressed in the song “Brand New City” from her very first album. In the song, the protagonist feels that their life and body are deteriorating, and that they need to completely reinvent themselves. If they “gave up on being pretty” (i.e. were no longer consumable and pristine, and they allowed themselves to be vulnerable), they “wouldn’t know how to be alive.” The speaker in this song then comes to the conclusion that they should move somewhere where no one knows them and “teach [themselves] how to die.” “I Guess” contains similar lyrics: “Without you, I don’t yet know quite how to live.” However, this sentiment is much less fatalistic. There is still hope contained within this line that they will learn how to live– they do not need to teach themselves to die.

The album closes out, unlike the rest of Mitski’s discography, on a high note with the song “That’s Our Lamp.” While the upbeat nature of “Love Me More” was used to symbolize distraction, the upbeat nature of “That’s Our Lamp” symbolizes nostalgia and acceptance. The relationship the protagonist is in is not doing well. The good times, where their partner genuinely enjoyed their company and their relationship “[shone] like a big moon,” are now past, and it seems to the protagonist that their relationship may be ending. They are again in the realm of the unknown, as was the case in the beginning of the album. However, unlike previous songs, they have a past to look back on fondly. While not completely in the aftermath of the relationship yet, the protagonist is finally at a place where they can move on. The past is not simply negative, nor is it something one needs to be distracted from– it can be viewed with true nostalgia. Looking up into the single room where the relationship was contained, the album fades out, layered with the sounds of crowds and laughing children, on this final phrase: “That’s where you loved me.”

1 note

·

View note

Photo

The Soundtrack of My Rage

by Makayla Williams, design by Bela Chauhan

(CONTENT WARNING: The following piece contains mentions of bullying, self-harm, body dysmorphia, depression, and suicidal ideation. There are also extended mentions of anti-Black racism, misogynoir, and white supremacy.)

Introduction

“Black women are mad as hell… and they should be.”

With 1976’s “Network,” actor Peter Finch cemented his place in pop culture history, thanks to the now-iconic line: “I’m mad as hell, and I’m not going to take this anymore.” As TV news anchor Howard Beale, Finch’s oft-quoted declaration conveys a specific type of rage. It’s the kind someone feels when they come to terms with how powerless and alone they feel. It's a boiling, heartbreaking rage over the way life keeps disappointing you.

Howard’s outburst – now part of modern cinema history – succinctly sums up my adolescence. I wasn’t always an angry kid, but, whenever I think back to my childhood, I only remember the rage.

When I look at pictures from my youth, I always hone in on the big smile on my face in nearly every school photo. Maybe that girl had everyone else fooled, but I knew how angry she was. The memories that stick out from are the bad ones, namely the bullying and how it came in different flavors, like a shitty, knockoff version of Baskin-Robbins.

I was overweight, so thinner girls and heavier-set girls made fun of my body. I was shy, so extroverted kids made me feel bad for not talking enough. I was tomboyish, so I got sneers from girls who hated how I dressed and fangirled over “Doctor Who” and “The X-Files.”

The teasing over my weight led to an unhealthy relationship with my body and food. Eventually, I became convinced that I didn’t deserve to be alive. Suicidal thoughts suddenly became a constant in my life, and they continue to be part of my young adulthood. Worst of all, I took that pain out on others. I shut out anyone, kids and adults alike, who tried to bond with me. Most of the time, I thought I didn't deserve friendship, that I deserved to be sad and lonely.

Then, the switch was flipped. I can’t recall when but I was certain of one thing: I was mad as hell, and I wasn’t going to take it anymore.

Who’s Afraid of the Angry Black Femme?

In her 2018 book “Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower,” author Brittney Cooper makes a provocative declaration: Black women are mad as hell… and they should be. “Black women have the right to be mad as hell,” Cooper writes, “There is no other group, save Indigenous women, that knows and understands more than fully the soul of the American body politic than Black women, whose reproductive and social labor have made the world what it is. This is not mere propaganda. Black women know what it means to love ourselves in a world that hates us.”

To a white reader, Cooper’s words are incendiary. How dare she say such a thing? Does she know how far she is setting back Black women right now? To a Black femme reader like me, her words were a balm. Here was a Black woman acknowledging the pain and fury of fellow Black women and femmes, telling them they had every right to be angry. Given how much we put up with in this country, from living with the chronic stress brought on by daily racism and misogynoir to being forced to shoulder the unrealistic (and racist) burden of being the savior of America, why shouldn’t we let the world know we’re pissed?

Yet, Cooper’s words were a deliberate rejection of what I had to adapt to as a kid. Indirectly, I was taught that the worst thing a Black woman or femme could be was angry. We needed to be calm and approachable. I watched my father, a Black man who can freely express his fury, tell my mother to “calm down” whenever she was in distress. I, too, got the “calm down” refrain from my dad and my mom. Being told to “calm down” peeved me more than some random kid making fun of my hoodie.

If my parents weren’t telling me to calm down at home, I was hearing about people (read: white people) telling a Black woman to calm down. During the Obama years, Michelle Obama would easily be branded “the angry Black woman” because she refused to be in the background. Michelle always spoke up for herself and for those who couldn’t, but she might as well had been committing an act of treason every time she spoke.

It was reminiscent of how Serena Williams’ rage on the tennis court was used against her in the press. At best, her rage was unsportsmanlike; at worst, it was ugly. As a result, Serena was seen as a raging animal or, worse, a crybaby. Seeing Serena and Michelle get torn down in the press or on social media sparked an awful thought in my brain: this is routine for us. Black women and femmes were always at risk of being subjected to misogynoir – a cross-pollination of racism and misogyny directed squarely at Black women and femmes – in their day-to-day lives. Thus, the famous “mad as hell” scene from “Network.”

Watching misogynoir happen in front of me, long before I knew such a word even existed, was distressing. I had to escape it – no, I needed to escape it. So, I ran headfirst into an unusual space, one where rage wasn’t this beast that threatened to swallow society whole: alternative rock.

“I’ll Stop the Whole World from Turning Into a Monster”

Today, there’s a running gag on Twitter about Black people loving Paramore, but, back in middle school, I treated them with abjection. In the mid-2000s, it was cool to hate on the “Twilight” franchise and the teenagers who loved it. Although Paramore had a song on the “Twilight” soundtrack, to be outed as a “Twi-hard” was a social life death sentence.

So, in 2011, I listened to Paramore for the first time, free from any dumb pretensions about “Twilight.” A random music channel happened to be playing the music video for “Monster,” which was featured on the soundtrack for “Transformers: Dark of the Moon.” The most vivid memory I have about “Monster” was Hayley’s red hair. It was a light red with tinges of blonde at the roots, but still fiery. It was like Molly Ringwald got the makeover instead of Ally Sheedy in “The Breakfast Club.” In Paramore’s world, the outcast was the cool girl. But more than that, the outcast got to speak her mind.

Reading the lyrics of “Monster” now, it is obvious that Hayley is directly addressing how she was vilified by her former bandmates in a blog post. Despite being twenty-three, I still interpret them the same way I heard them at twelve-years-old: a scathing screed against a rapidly crumbling world.

Coupled with a grungy aesthetic and shots of the band running through an abandoned hospital, “Monster” captured my teenage experience. Whatever innocent world I lived in was shattered by wall-to-wall news coverage of Black bodies being brutalized by police officers and white supremacist vigilantes and the Black Lives Matter protests that arose in response. Adding insult to injury, of course, was the misogynoir prevalent in mass media and pop culture. When all you see is the horror of being Black in America, a decrepit, abandoned hospital quickly falling apart felt like an apt description of my Black adolescent experience.

Somehow, these three white twenty-somethings from Tennessee captured what it felt to be a Black pre-teen witnessing the beginnings of the Black Lives Matter movement and coming to grips with the insidious anti-Blackness of American life. It was unsettling. It was also the most realistic representation of Black American teen life I’d ever seen.

After “Monster,” I immediately sought out more Paramore. I listened to their music, including “Decode” from the “Twilight” soundtrack, for the rest of that evening. Not just because I loved what I was hearing, but because, for the first time in a long time, I didn’t feel so alone and helpless.

“All That I Want is to Wake Up Fine”

As the world began to grasp the scope of the global coronavirus pandemic in 2020, I was also preparing to start my first year at UCLA.

The fall quarter was supposed to be – please forgive the “High School Musical” reference – the start of something new. For three years, I worked hard throughout community college, pushing myself to get my associate’s degree. There were lots of tears, sleepless nights, and anger, but somehow I pulled off the impossible. Additionally, I was learning to live with anxiety and clinical depression. After years of struggling with ill mental health, I discovered what I was experiencing had a name and others my age were coping with the same struggles. Heck, I’d even gotten my first steady job working at the local movie theater.

For the first time, things weren’t so bleak. I actually felt like a (mostly) functioning young adult. Then, the world shut down.

For yet another year, I was at home with my parents, stuck in my tiny, messy bedroom. I had to subsist off unemployment checks that barely covered textbooks, let alone basic necessities. I had to learn how to navigate life with a mask on and re-learn how to go inside a store without having an anxiety attack. And, I had to make my bedroom a functional learning space, which was hard to do with all the Funko POPs that took up space on my desk.

All of these circumstances reignited the rage I thought I had left back in high school. Worst yet, they also triggered depressive episodes that grew harder to recover from. Since I couldn’t see my therapist in person, I had to talk to her over the phone or Zoom, but this didn’t help. That simmering rage was now coupled with sadness.

The seemingly endless news coverage of the police lynchings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor and the white supremacist vigilante killing of Ahmaud Arbery didn’t help either. I couldn’t bear to see more Black lives snuffed out by a colonial-capitalist white supremacist empire. Their faces, their deaths, their grieving families … they were all over my Instagram feed and the national news cycle. It was a brutal reminder that not only was Black death a constant fixture of the pandemic, but that Black death was a constant fixture of American life.

For the first time in a few years, I re-listened to Paramore’s 2016 album, “After Laughter.” Combining the zany, upbeat flare of the synth-heavy 80s New Wave with classic coming of age themes, “After Laughter” honestly confronted the brutal and messy transition from adolescence to adulthood. As Hayley Williams told The New York Times: “You can run on the fumes of being a teenager for as long as you want, but eventually life hits you real hard.”

I didn’t appreciate “After Laughter” when it was first released. Partly because I thought it was childish to be nostalgic for the stuff that brought you joy as a kid, and partly because I didn’t want to relive the worst years of my life during what proved to be the worst year of my young adulthood. So, I shut Paramore out.

Fast forward to 2020, and I was listening to “Hard Times,” the first song off the album.

“All that I want,” sings Hayley in the first verse, “is to wake up fine/Tell me that I’m alright/That I ain’t gonna die.” Despite the aggressively joyful synth-pop beat, that first verse summed up how I was feeling in the early days of the pandemic.

More than going outside or being around my friends, all I wanted was to wake up the next morning and feel okay. Like the world as I knew it wasn’t teetering on the brink of collapse. Needless to say, I got choked up listening to “Hard Times.”

I already knew the song was inspired by Hayley’s battles with depression, so that wasn’t the reason I had that painful lump in my throat. Like they did when I was twelve, Paramore captured what it felt like to be Black, femme, and in distress. Most importantly, Paramore gave me a much-needed space to let out all the emotions I had been stifling throughout the pandemic– especially that twisted, monstrous fusion of rage and sadness. I was mad as hell, and I couldn’t take the depression, the anxiety, and the Black death anymore.

I was tired of the constant negging on about staying positive; there was nothing positive about what we were living through. Being told repeatedly to “stay positive” or “remain calm” felt like more of the respectability politics I had swallowed since I was a kid. How was I supposed to stay calm in the face of both a global pandemic and exacerbated anti-Black racism? Matter of fact, why should I have to?

Black femme rage is a terrifying thing, no doubt about it. When Black women and femmes get angry, it has the potential to upend everything the colonial-capitalist white supremacist empire holds near and dear. We can transform that anger into meaningful action; just look at how we turned Donald Trump into a one-term president.

Mass media says we saved American democracy by rejecting the neo-fascist, white nationalist reality TV reject, but really we just aren’t the type to suffer fools lightly. Nor did we save American democracy; it is just as corrupt as any of the institutions that have sprung from it. It’s been that way for awhile; it didn’t start when Trump got elected. We’re just waiting for everyone else to get a clue.

For Paramore, “ignorance is your new best friend” makes for a great chorus. For the rest of America, it makes for a reality we’re tired of. If there’s one thing I have learned from this pandemic, it’s that America has been friends with ignorance for too long. Paramore grew up and dropped the deadweight that held them back from growing up. Maybe it’s time for America to do the same.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nostalgic Dumps: Open letter to the Childhoodless

by Alexus Torres, design by Bela Chauhan

Hello Lonely Child,

How are you? I ask this as I know it is rare that someone genuinely cares how you are feeling. I ask you now in hopes that you reflect on yourself today as you read this. I hope you deeply evaluate how you truly feel, not the feelings you show to your family or the sentiments you express in social settings, but the authentic you.

You are unreasonably expected to perform well at all times and perform well you do, but what about you? You, whose hazy, childhood memories are overrun by a forced responsibility over a child, while you were a child yourself. You, who carries hazy memories of translating important legal documents for your immigrant parents. You, whose hazy childhood you spent raising yourself and becoming your own provider.

An adult since you were old enough to take directions, from “watch your brother” to “make yourself lunch”; you alone have faced challenges and tasks that no one else your age had to do. You alone, who was so worried about providing for yourself and your family that you had childhood ripped away from you. Time that was for watching whatever was playing on Disney Channel or Nickelodeon was replaced with worrying about if your family had enough money to feed everyone that day, or if your family would be able to survive another fight.

My little peacemaker, nostalgia is hard for you because what is there to be nostalgic about? You were never allowed the luxury of playtime or the beauty of self-discovery, expelled with anxiousness and worry. What is your nostalgia?

Does it lie in the children you raised? Watching those kids growing up, taking them places, helping them with their homework, laughing whilst watching their smiling faces dance about. Does it lie in your escape? The books you read, the shows you watched, or maybe, the Tumblr blogs you were too young to see. But where are you in this narrative, child?

Memories of youth come hard to you. While everyone recalls their childhood filled with reds, oranges, blues, pinks, and purples all you can recall is gray. Being the parent who raised babies while being the baby yourself. Everything you did was for your family because you love them so much. It feels as though your life was never truly yours and all the choices you make are perfectly calculated, producing the best results. Your grand performance of childhood that deserved a standing ovation was met with the shy squeak of a mouse. No one has ever thanked you or acknowledged the sacrifices you made, but you have never expected praise. This was your responsibility.

Even now you may not have any regrets about your childhood because you hold intense love for your family. You love them enough to be okay with the idea of sacrificing your own childhood because you kept your family together. You know that the children you raise will have long-lasting childhood memories. You know that everything you sacrificed made sure your family survived another day.

But it’s okay to be angry about not having a childhood. It’s okay to be upset at the gray area of your crucial developmental years. It’s okay to have never refined your narrative; you have never taken the time to care for yourself and explore your likes, wants, and needs.

So, what do you like? No, not what does your family like or what were you expected to like, but what do you like? It’s okay not to know. It is okay to be confused. Now is your time to take care of yourself. Development does not end with childhood – you can always discover yourself. You can still laugh and play like you craved to do when you were younger.

Age does not define your ability to have fun. Make mistakes now. Eat ice cream in the morning. Wake up early on Saturday and watch cartoons. Play in puddles in the rain. Color outside of the lines.

Learn to become comfortable with yourself, but also with others. You have been alone for so long and sometimes you feel as though people are a hindrance to you but it’s okay to let people in. It is okay to ask for help when you need it. No one will think you are weak or annoying for needing a helping hand. You are human, harmonizing child.

Your life does not end when you turn eighteen. You are a forever-growing tree. You will grow new branches, new leaves, and, over time, maybe even some fruit and flowers. Even in your growth journey, you will experience hardships. You may not flower every spring. Some will take your branches and use them to start a fire. You will lose branches and leaves as you grow but that’s okay too, it is all a part of the circle of your life.

Now is the time to focus on your needs and focus on your likes and dislikes. What makes you happy? What makes you unhappy? What’s your favorite song? Who's your favorite cartoon character? What’s your favorite book? What’s your favorite food?

Now is the time to figure this out. Figure it out for you, not your family, not your kids, not for what your friends have said but truly for yourself. You deserve the kinship of childhood, lonely child. You deserve the chaos of childhood, peaceful child. You deserve the clash of childhood, harmonizing child. This and much more. Now is the time to discover yourself, child. To discover yourself.

From,

A Healing Child

1 note

·

View note

Text

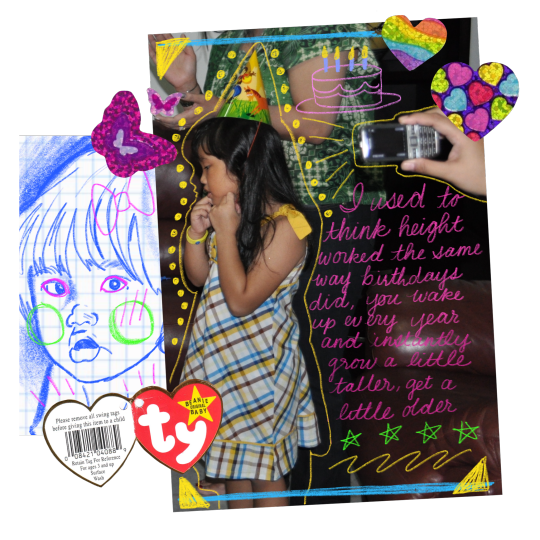

The Feminine Urge to Cry Over Growing Older

by Tiffany Peverilla, design by Hailey Lynaugh

January 8th. 8 years old. I still remember how cold the marble-tiled floor felt on my toes when I crept out of bed in the early morning and ran to the mirror in the corner of my room to check my height. I used to think height worked the same way birthdays did, you wake up every year and instantly grow a little taller, get a little older. That was growing up to me, I just wanted my tiny little hands to reach the sky.

Even now, the image stays clear in my head of the messy pink frosting, the big Snow White birthday banner hanging between two towering cabinets, the party hats on that black coffee table in that small living room I used to know. I was so convinced 8 would be the year I finally got to be a big girl, the year I would finally grow up.

Today is January 8th again, but this time, I did not have the privilege of stepping on a cold marble floor. I do, however, have the privilege of a mirror in the corner of my room, but one I avoid profusely in fear of having to stand face to face with the version of myself my brain would cruelly craft for me each day. No longer are there party hats on the table, pink frosting on a cake and Snow White wishing me a happy birthday. No, because growing up isn’t growing taller and being allowed to stay up past 9pm. Growing up means being greeted with the pinging sounds of text notifications that all seem to scream, “19!” even though you still feel 8. Growing up is looking at your mom’s contact profile a little too long, wondering if she might have liked you more if she didn’t see a reflection of all the things she hates about herself whenever she looks at you. Growing up is not growing taller, it’s nights of wishing you were smaller.

—

… Until it isn’t.

About a week after my birthday, my little sister sent me a TikTok video that forever changed the way I think about growing up. In this video was a think-piece written by a woman on why women seem to perceive growing up as a negative experience, but men don’t.

**Disclaimer: I acknowledge that gender is not a binary and that the growing up experience is not exclusive to just men and women. My intentions with this article is solely to view this topic in a male vs. female perspective due to the fact that the issues I will be talking about stem from society at large not having fully progressed to accepting the absence of a binary.

I don’t tend to gravitate towards political think-pieces and comments written by people on social media because, truthfully, I’ve always found them to be lackluster and a little too speculative. So when I first watched the video sent by my sister, I scoffed and brushed it off in disbelief. Surely this random white woman on TikTok is just looking at it a little too deeply, right? Who in their right mind would actually be optimistic over getting older?

But then I thought about it.

Have I ever heard a man complain about growing up? Every post, song, book, movie, or quote I’ve encountered that talked about growing up in a negative or even bittersweet way was always exclusively from the perspective of someone who did not identify as a cis-het male. So maybe there really was something to it, and maybe this TikTok video was right.

Still a little skeptic, I turned to some guys for a little more insight. The men I could get a hold of ranged from being working class to high class and were either cis-het or gay; this is because even though I could not account for the differences between every social/ethnic/economic background, I still made sure to include different male perspectives instead of just treating them like a monolith. I texted them the million-dollar question of “What is/was your experience with entering adulthood?” and hit send with half of me hoping their answers would prove that TikTok video wrong and the other half of me wanting them to say exactly what it hypothesized.

Lo and behold, all of their experiences somehow perfectly fit the narrative I’ve been oblivious to for so long. They were excited (or had been excited) to grow up. I sat there completely baffled. I almost wanted to vomit from how stunned I was that all this time I’d been grieving my childhood, I was alone; that all this time I thought crying over wasted youth was a universal experience, it was really just something only half the world was subjected to.

The longer I sat with it, though, the longer I thought, of course. Why wouldn’t they be optimistic? It’s true that not all men experience growing up the same way due to racial background, sexuality, class, etc., but it’s clear that for most of them, they were taught that entering adulthood meant entering a world of opportunity. For some of them, they were even told that the second they left childhood, they would be greeted with power and sex and stability. To them, growing up was getting taller, and endlessly so at that. And even if the unfortunate reality is that many men never quite end up getting to this dreamland fantasy, very rarely were they informed of it.

Take, for example, how most male protagonists are represented in all your beloved stories, movies, and TV shows. Male characters are almost always represented as successful, opportunity-chasing people who never fail to get the girl. Even if they are forced to go through challenges and periods of hardship, they are almost always one-dimensional in the sense that very few of their problems seem to intersect with their identity as a cis-het man because there really aren’t any. Who can make an issue out of gaining privilege, anyway?

Beyond that, there’s also the idea that women are born with proverbial shelf-lives in the sense that they only tend to decay as they age – very much like how bread gets moldy around the time of their expiration date – whereas men only seem to be more desirable the older they become.

Think of George Clooney, Brad Pitt, or Ryan Reynolds. These are all examples of men well above 40, and they all clearly show signs of aging (i.e. gray hair, wrinkles, aging physique, etc.) but they are what society still perceives to be successful “heartthrobs”, or as some people like to say it, dilfs. Now, think of Kirsten Dunst; she’s only 40, but you could never imagine her as the main, hot, beloved darling of any blockbuster movie. She’s younger than the men listed above, but her appropriate and totally natural signs of a life well lived are not acceptable nor attractive to society. This only becomes increasingly obvious when we start to think about the number of “She’s already 30?” posts circulating social media about female celebrities who people are deluded into thinking are “sexy starlets”, even though they look like almost every other 30-year-old woman in the world. And what about the fact that when old men have gray hair and a beard, they’re categorized as “silver foxes”, but when a woman’s hair turns gray, she’s undesirable and a grandma? Whether we like it or not, we have been socialized to think that for women who are growing older, change (especially that concerning physical appearance), is not natural. Even semantically speaking, milfs and dilfs refer to people of different age groups. The dilf is in his mid 40s to 50s, he’s “aged like a fine wine”, and maybe even has a dad-bod. The milf, on the other hand, is a 30, maybe 40-something-year-old Pixar mom with a minuscule waist, and hips that don’t lie.

This double standard slithers its way into many professional settings, too. The plastic surgery and beauty industry, for instance, prey on women who have been told repeatedly that they can’t look a day over 30 and make billions of dollars because of it. Maybe it seems like getting a little botox isn’t harmful, but think of the reason behind it. Do whatever you want to your appearance, sure. After all, no one is here to tell you you can’t – but would you have wanted to change the way you look if society hadn’t bombarded you with subliminal, and sometimes even direct, advertising of an unattainable and toxic beauty standard?

Even more than that is the way race/ethnicity intersect with how the world perceives girlhood and womanhood. Black girlhood, for example, is often not equated to youth in the same way others are. This is because to our society, young Black girls are frequently not seen as girls at all. Rather, they are perceived as grown women and subsequently expected to act like one. They don’t get to feel like, be represented as, or seen as young girls. In movies, they are often not depicted as innocent, pure and youthful the way white children would be. They are instead sassy, grown up, and in some cases, even sexualized. They are “sapphires” and “Jezebels”, but not children. They can never fit into mostly white and Eurocentric beauty standards, even if they physically have some of the desired features. It doesn’t matter what they look like because other people will always automatically perceive them as more mature and adult-like, almost as if they’re not pure enough or traditionally feminine enough to be as protected as the white girls of our society are. Meanwhile, many East Asian women are infantilized and fetishized for their stereotypical baby-faces and youthful or delicate features. Take a look at how people buy sexualized versions of Japanese school-girl uniforms to perform with on their OnlyFans accounts.

The harsh reality is that there is no winning for anybody. If you do get botox and try to stay young, you’re trying too hard and insecure. If you’re acting too childish and innocent, it’s off-putting. If you have a 20-step skincare routine to prevent wrinkles and sun-damage, you’re obsessive and high maintenance. You have to be perfectly young yet also sexy, adolescent yet adult, delicate yet sultry, exotic yet tame, tiny but curvy, non-threatening yet challenging, etc. This judgement doesn’t just exist in the personal sphere of a heteronormative romantic life either, it also affects women in their work lives and communities. If you’re too young, then you’re naive, but if you’re too old, then you need to be caring for your family and children instead of spending time in the office. Then, if you don’t spend as much time in the office, the pay gap is suddenly explained and warranted. How much time do women have to live? It seems like the countdown of when a woman expires to society starts right before puberty and ends right before full adulthood. When is a woman’s prime? Their teens? Their 20s? It’s impossible not to feel the constant fear of getting older when you have no time to enjoy the now. So much of most women’s lives are spent trying to prevent the inevitable, all because we refuse to see women as more than their age.

So, to the rest of us who don’t identify as a man, we are just brought into this world to have to live with the consequences. There’s a quote from Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag that may have been intended as a joke but actually rings true in many aspects, “Women are born with pain built in, it’s our physical destiny.” Whether or not one identifies as a woman, if they are perceived by the world at large as a woman, then they instantly carry the inherent baggage of responsibility. They instantly owe many different things to many different people – they owe marriage to their families, children to their spouses, beauty to the world, etc. Suddenly their value does not come from their own being but from what their body can offer. We are expected to become, as Taylor Swift puts it, “a never-needy, ever-lovely jewel” – an ornament to society.

As a lesbian woman from Southeast Asia, the cultural and societal responsibilities of heterosexual marriage and bearing children are constantly looming over me. Growing up, I was told that producing children was gravely important to my culture and that continuing my family’s bloodline was a must, not an option. Even at 10 years old, dining table conversations would consist of my parents giving my sisters and me advice on what kind of man we should marry and what kind of houses would be most suitable for us and our future kids. I remember attending the funeral of one of my distant relatives once and my mom pointing to people gathering together and celebrating. She said, “Look. In Batak culture, if all the kids of the person who died have successfully built families of their own, then that means the person who died will be happy in heaven and people will celebrate, even if they are dead. Otherwise, the death of the person cannot be celebrated because it can be said that they have not lived their full life.”

On top of that, my parents were not born wealthy. I did not come from a family who could easily pull money out of trust funds and hand it over to me. My parents and their parents had to work tirelessly so that I could have a roof over my head, have food on the table every day, go to good schools and live a successful life. If my grandma can escape from poverty and endure a loveless and abusive marriage just to provide for my mother, and if my parents can sacrifice their health for years just so I could go to a school like UCLA, then why is it so hard for me to just give them one thing back by marrying a good man and having babies that they could hold in the hospital one day? Why is it so hard for me to just not be gay?

This is what the ticking time bomb in my head is counting down towards – the reality that I someday have to look my parents dead in the eyes and say I’m sorry. I’m sorry I cannot be the woman you wish I could be. I’m sorry all those years you spent working hard for me have gone to waste. I’m sorry all those prayers for me to stray away from homosexuality never made it to the God I can’t even be sure I believe in. I’m sorry that the world has taught you to believe my identity is an act of defiance. I’m sorry.

That is growing up to me.

—

Today is no longer January 8th, but I dread the day that it will be. I dread the feeling of the cold floor on my no-longer-tiny toes when I get up in the morning. I dread what the mirror in the corner of my room will show me. I dread the lack of party hats and towering cabinets and black coffee tables and pink frosting on cakes. I dread the absence of that ridiculous Snow White banner. I dread the “Happy birthday!” notifications and the recycled ugly pictures posted on friends’ social media accounts. I dread hearing all the same stories of the day my mom gave birth to me. I dread not being able to breathe in the shower. I dread having to hold in tears during phone calls. I dread having to look at childhood pictures thinking “God, when did everything change?”. I am dreading it all because 8-year-old me was wrong: growing up is not growing taller. At least not to me.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Results!

Girlboss - Hey girly! You totally crushed capitalism. Whether your weapon of choice is pyramid scheme or oil company, you clawed your way to the top and have the #girlbossplaque to prove it.

Gaslight - Quiz? What quiz? I don’t know what you’re talking about.

Gatekeep - When you’re not busy making strangers list the entire discography from the band on their t-shirt, you’re updating your fanpage, memorizing the bloodtypes of your faves, and scouring social media for real life easter eggs. Godspeed in securing those concert tickets, bestie.

Intersectional gaslight, gatekeep, girlboss, - Girlboss might’ve won capitalism, but you won at life. As an intersectional gaslighter, gatekeeper, and girlboss, you’re the best of the best and the worst of the worst.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Our Invisible Reflection

by Minnie Seo, design by Lauren Cramer

As the word “Nostalgia” provokes retrospection, it can be easy to reflect upon the past with rose-colored glasses — remembering the good days when there seemed to be never-ending freedom from worry and everything seemed so much easier… Was everything really as great as we remember it to be? Even before the pandemic, was everything perfect? Memories of dunkaroos, Lisa Frank, De Neve Late Night, and maskless students may come to mind, but is it the proverbial “good ol’ days” or the sheer ignorance that makes it easier to look back?

The process of looking back on these times can prevent the reflection of the mistakes and flaws of not only ourselves, but also our society and campus. Perhaps this nostalgia, an escape from our reality, paves over the words we most needed to hear and the people we needed to scrutinize in order to progress.

Let’s take a look at FEM. Our publication was first known as “Together” from 1973 to 1996. In the beginning, Together was considered a women's interest paper. UCLA —at the time— was not keen on the idea of a feminist centered news outlet. However, the destigmatization of feminism in mainstream media in the 1980s allowed the publicated to be redesignated as a feminist paper. Eventually, in 1996, the publication decided to rebrand what we know it as today: FEM — UCLA’s Feminist Newsmagazine.

While I looked at an old copy of Together from 1975, I found myself looking at the flipped out curtain bangs, huge square glasses, and different prints. Through this indulgence in the aesthetics of Second-Wave Feminism Advocacy, I almost forgot about the reality of the movement, which was saturated with white feminism, selective allyship, and respectability politics. In recent years, it’s been easy to point out the problems and recognize the importance of intersectional feminism and womanism. Even an article from this issue of Together says, “‘Where are minority women in feminism?’” We find ourselves asking the same question — albeit with different words and perspectives — nearly 50 years later: have we made space for marginalized people within feminism or other social activism? How do we prevent ourselves from falling into selective allyship? We can start off with sincere, strict, and comprehensive reflection of our present moment.

As UCLA returns to implementing in-person instruction, everybody can feel the pre-pandemic memories emerge. Things going “back to normal” necessitates adherence to COVID protocols, but is that enough? Is it enough when the Disabled Student Union (DSU) is still continuing to advocate for hybrid learning options, reinstatement of priority enrollment, and their basic rights to education when UCLA should have listened first?

Recently, the DSU conducted the longest sit-in in UCLA history. However, the continuous usurpation of disability rights has been going on since late May 2021. The UCLA Academic Senate and consulting administration decided to place a unit cap on disabled students’ priority enrollment, ignoring the many difficult realities that disabled students have to go through. Even before the past few years, UCLA has been ahead of the disability law requirements, but have still fallen short. In another article from Together in 1994, then 24 year-old student Celia Salinas —a legally blind student— remarked that, “We are, in fact, ahead of the requirements by law.” Salinas then went on to comment on the “convoluted and stupid” ramps at UCLA, pointing out how they were “too steep, too narrow, and they’re not in a logical places… Also when it rains, where the ramp intersects with the street, it’s a big, huge puddle.” Even the Medical Center at the time was not wheelchair accessible past the 1st or 2nd floor. While UCLA was supposedly ahead of the curve, clearly they were not listening to the actual thoughts and opinions of disabled people. Advocacy can only be considered as such if it takes into account the actual needs and wants of the group it is trying to advocate for.

The United States (currently) faces the COVID variant, omicron. UCLA students and faculty find themselves scrambling from Zoom and to classrooms, with little support and high expectations. If the administration had just listened first to the underrepresented voices that requested for hybrid options, maybe the first four weeks of Winter Quarter would not have been as tumultuous.

When the demands of marginalized people are ignored and suppressed, it ultimately affects us all. A majority of a group may want to make the excuse that since a certain group is in the minority, their opinions and concerns should not affect the whole group— but it is quite the opposite. If the majority does not respond to the basic rights of a minority, the minority is further oppressed and subjugated by the majority, ultimately creating more inequality. There is a ripple effect that is created by a splash of apathy.

Right before the genesis of Together, the early forms of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 were vetoed twice by Richard Nixon, leading to protests led by the Disabled in Action (DIA) organization run by Judith Heumann. However, Together’s earliest article about disability rights is dated to 1994. As inclusive as Together and FEM have historically strived to be, the inclusion of disability rights within the publication has been a fairly recent development, though disabled people have always and will be a part of society.

Our nostalgia should not come before the needs and rights of those around us, and perhaps part of our nostalgia praxis should include the reflections of our shortcomings. In order to not commit the same mistake twice, it is important to learn what was originally wrong; however if the same mistakes persist, there has been no learning.

Time and time again it is proven that the voices of oppressed communities are unvalued and their voices go unheard. If the institutions and organizations we are a part of want to claim they support diversity, inclusivity, and equity, they must be held to a higher standard and held responsible for their failures. Professors can say they value and want to support their marginalized students, but active actions must be taken to prove that before they claim that they care. If they are not held accountable, UCLA will only further oppress communities that have given this institution and its student body the diverse and liberal qualities they claim to promote.

0 notes