Text

Online Conflict: Social Media Governance, Digital Citizenship, and Online Harassment.

This week's set reading by Haslop, O'Rouke, & Southern studies the normalisation and tolerance of online harassment and the prevalence of gender-based harassment (2021). This discussion will explore social media governance, conflict and digital citizenship, and online harassment.

Social Media Governance

Social media is governed at multiple levels; including government, platform owners, and micro-level regulators.

Governments regulate online activity through legislation (Gorwa 2019). This legislation is often imposed onto both users and platform owners, and varies amongst countries. In Australia, laws such as the Online Safety Act 2021 enforce the protection of users from harm online (eSafety Commissioner 2023b). China has internet censorship laws enforced as part of their regulation (Gamso 2021). Service providers and platform owners must abide to censorship laws in order to operate in the region, such as implementing content filtering practices (Gamso 2021).

Content moderation by social media owners occurs on a large scale. Mass governance is achieved through platform policies, features, and automated enforcement (Birman et al. 2019; Gorwa 2019). At this level, content moderation is platform specific (Gorwa 2019). Facebook’s terms of service exemplify platform governance. Users must abide by these terms, such as restrictions on what content is allowed to be shared, in order to continue to use the platform (Facebook 2023b).

View the terms and conditions below.

Micro-level social media governance refers to regulation that occurs within certain spaces on the platform. Expanding on the aforementioned example, Facebook groups are governed by users selected as moderators and administrators (Facebook 2023a). These users have the authority to delete content, mute and remove users, and delete the groups they govern (Facebook 2023a).

The activities of these governing groups may intersect, such as the combination of human and automated regulation or changes in platform policy due to legal obligation (Birman et al. 2019; Hallinan, Scharlach & Shifman 2023). These groups may also have conflicting interests, often social or commercial.

Conflict and Digital Citizenship

Conflict in online communities is inevitable as there is potential for conflict in any spaces in which individuals can communicate. Online spaces are a digital microcosm of society, and thus online and offline conflict are interrelated (Kilvington 2021). Conflict online mirrors larger issues in society; often the unequal distribution of power in the context of gender relations, accessibility, and visibility (Kilvington 2021). By analysing online as an extension of offline conflict, it can be suggested that online conflict cannot be eliminated simply through content moderation and social media governance (Kilvington 2021).

Harassment in Digital Spaces

Online harassment is "defined as threats or other offensive unwanted behaviours targeted directly at others through new technology channels … or posted online for others to see that is likely to cause them harm" (Haslop, O'Rouke & Southern 2021, p. 1421). Hate and harassment have existed prior to online spaces, however social media has both normalised and amplified this behaviour (Keipi et al. 2016). The tools afforded by social media to reach a larger audience have subsequently augmented the visibility of hate, and anonymity features protect perpetrators from offline consequences (Keipi et al. 2016; Kilvington 2021; Haslop, O'Rouke & Southern 2021). This behaviour is often tolerated amongst those with higher digital literacy, perceived as an inescapable aspect of social media (Haslop, O'Rouke & Southern 2021).

Below is a video by TikTok creator, Mei Pang, responding to the range of negative comments left on her profile. In this video, Pang also states that harassers are empowered by their anonymity.

Harassment Towards Minorities

As offline inequalities are reflected into digital spaces, online harassment is disproportionately targeted towards minority groups (Farkas et al. 2021; Kilvington 2021). Discriminatory harassment, or hate speech, refers to the spread of hatred towards an individual or group based on protected characteristics (Kilvington 2021). It often extends beyond an individual receiver, with harassers targeting entire communities (Keipi et al. 2016; Kilvington 2021). Women, ethnic minorities, and the LGBTQ+ community are commonly victimised (Kilvington 2021).

Hate speech thrives on social media particularly due to user anonymity and the perceived invisibility of victims (Farkas et al. 2021; Kilvington 2021). As a result, perpetrators face little consequences for their actions and have no acknowledgement of the harm inflicted on their victims (Kilvington 2021). Moreover, unlike in offline spaces, online harassers can shamelessly express offensive views and easily connect with like-minded users (Kilvington 2021). This facilitates the formation of hate groups which mobilise to spread mass discriminatory harassment (Kilvington 2021).

An important factor to note when considering hate speech regulation is that what constitutes a criminal offence varies cross-nationally (Keipi et al. 2016). Thus, governance of hate speech on social media may be managed at either a platform or government level (Keipi et al. 2016).

Strategies for Remedying Harassment

Humour

Humour is adopted as a strategy for mitigating the effects of online harassment (Gilmour & Vitis 2017). The use of humour to respond to harassment shifts the power dynamic, transforming hateful comments into objects for ridicule and critique (Gilmour & Vitis 2017).

The following video exemplifies the use of humour to undermine hate comments. For context, creator is a man who wears stereotypically feminine clothing and makeup.

(Language warning)

Legal, Advocacy, and Advice

Users are protected from severe online harassment in Australia by the eSafety Commissioner, a government agency formed for online safety (eSafety Commissioner 2023b). Empowered primarily by the Online Safety Act 2021, the eSafety Commissioner has the power to investigate reports of acts such as adult cyber abuse and image-based abuse (eSafety Commissioner 2023b). With jurisdiction over service providers, the agency can enforce the removal of offensive content (eSafety Commissioner 2023b). The agency also provides a guide for reporting harassment on popular platforms and websites (eSafety Commissioner 2023a).

Platform Corporate Social Responsibility and User Self-Governance

Platform owners have a social responsibility to protect their users from harassment (Gorwa 2019). As aforementioned, content moderation is enforced through platform policies and automated surveillance (Gorwa 2019). Platforms also place significant responsibility onto users to uphold anti-conflict values (Hallinan, Scharlach & Shifman 2023). Equipped with features for managing and reporting harassment, users are tasked with performing free content moderation to contribute to creating a safer online space (Hallinan, Scharlach & Shifman 2023).

This delegation of responsibility onto users is exemplified by Instagram's 'commitment to anti-bullying' announcement. Instagram's commitment highlights user features which empower victims to limit, restrict, report, and block perpetrators (Instagram 2023). There are also features which encourage users to self-regulate, such as comment warnings given for attempting to post a potentially offensive comment (Instagram 2023). The bulk of this announcement highlights features which place the responsibility of governance onto users rather than the platform owners.

References

Birman, I, Bruckman, A, Gilbert, E & Jhaver, S 2019, 'Human-Machine Collaboration for Content Regulation: The Case of Reddit Automoderator', ACM transactions on computer-human interaction, vol. 26, no. 5, pp. 1-35.

Broude, E 2022, @eiitanbroude, 30 December, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS8ENVQP7/ >.

eSafety Commissioner 2023a, eSafety Guide, eSafety Commissioner, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://www.esafety.gov.au/key-issues/esafety-guide>.

eSafety Commissioner 2023b, Regulatory Schemes, eSafety Commissioner, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://www.esafety.gov.au/about-us/who-we-are/regulatory-schemes>.

Facebook 2023a, What is the difference between an admin and a moderator in a Facebook group?, Help Centre, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://www.facebook.com/help/901690736606156>.

Facebook 2023b, Terms of Service, Facebook, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://www.facebook.com/legal/terms>.

Farkas, J, Matamoros-Fernández, A, Nikunen, K, Pantti, M & Titley, G 2021, 'Racism, Hate Speech, and Social Media: A Systematic Review and Critique', Television & new media, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 205-224.

Gamso, J 2021, 'Is China exporting media censorship? China’s rise, media freedoms, and democracy', European journal of international relations, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 858-883

Gilmour, F & Vitis, L 2017, 'Dick pics on blast: A woman’s resistance to online sexual harassment using humour, art and Instagram', Crime media culture, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 335-355.

Gorwa, R 2019, 'What is platform governance?', Information, communication & society, vol. 22, no. 6, pp. 854-871.

Hallinan, B Scharlach, R & Shifman, L 2023, 'Governing principles: Articulating values in social media platform policies', New media & society, vol. 0, no. 0.

Haslop, C, O'Rouke, F, & Southern, R 2021, '#NoSnowflakes: The toleration of harassment and an emergent gender-related digital divide, in a UK student online culture', Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 1418-1438.

Instagram 2023, Instagram stands against online bullying, Instagram, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://about.instagram.com/community/anti-bullying>.

Keipi, T, Nasi, M, Oksanen, A & Rasanen, P 2016, Online hate and harmful content: cross-national perspectives, Taylor & Francis, eBook Central (Proquest), pp. 53-74.

Kilvington, D 2021, 'The virtual stages of hate: Using Goffman’s work to conceptualise the motivations for online hate', Media, culture & society, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 256-272.

Pang, M 2023, @meicrosoft, 16 March, viewed 8 May 2023, <https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS8EFRp3P/>.

0 notes

Text

Gaming Communities: Formation, Social Gaming, and Live-streaming

This week's discussion is an exploration of gaming communities, particularly how platforms and online spaces have enabled its formation. This discussion centres on the notion that gaming communities interact through multiple platforms and flow between those that best suit their present needs.

Social Gaming

Multiplayer features have become conventional in online gaming (Allen et al. 2021). Multiplayer features entail collaborative or competitive play with other users, and have shifted gaming into an activity in which users can socialise with others (Allen et al. 2021). Multiplayer games facilitate community formation in various ways, including social support and bonding over shared interests (Kelly, Magor & Wright 2021).

The Fortnite community exemplifies how gamers bond over multiplayer games and exist on other platforms when not actively playing. Fortnite is a globally popular synchronous online game, attracting over 125 million users within its first 9 months (Marlatt 2020). Despite the game's competitiveness, the Fortnite community bonds over common goals of increasing skill, status, and performance.

Outside of active gameplay, members of the Fortnite community can continue to interact through dedicated spaces on other platforms. There are currently 47.3 million posts on Instagram under '#fortnite' at the time of writing, and the official Fortnite server on Discord has over 1 million members (#fortnite 2023; Discord 2023a). These spaces are formed by users to share highlights of gameplay, memes, fan-art, and communicate with others in the community.

Below is an example of a member of the Fortnite community using Twitter to engage with others.

Platforms and Community Building

The gaming community has access to a range of platforms which fulfil specific needs. Platforms such as Steam and Discord have features ideal for community building and engagement, including discussion boards and chats (Gandolfi 2022). Services like Twitch and YouTube Gaming offer an experience aligned closer to spectatorship (Gandolfi 2022).

Community building is also facilitated by platforms through opportunities for social learning (Gandolfi 2022). In the context of gaming, users experience social learning when applying behaviours displayed by others in the community (Gandolfi 2022). Through features such as content sharing, streaming, and forums; platforms contribute to community building by creating spaces in which users can collaborate with others to extend their knowledge beyond games' provided instructions (Gandolfi 2022).

Niche Communities: Knowledge Communities

Online communities for sharing knowledge, skill, and expertise are referred to as knowledge communities. Whilst the aforementioned section discusses social learning enabled by platform features, the existence of knowledge communities differs as these are gamer-created spaces dedicated to sharing knowledge. These communities form from collaboration between users who place value on expertise.

Nookipedia is a wiki space for knowledge communities of the Animal Crossing series. It is an unofficial player-created encyclopedia in which the community documents learned knowledge from their gameplay. The Nookipedia community consists of users who share information on collectibles, in-game events, and game updates; and demonstrates how sub-communities form based on niche interests.

Streaming and Community Building

Streaming as an activity for community building originates from communal game spectatorship which has existed before the internet (Bowman et al. 2019). Streaming has shifted gameplay into a opportunity for connection in a space unlimited by proximity (Taylor 2018). Streaming communities are centred on both communal spectatorship and collaboration, often forming around streamers or genres of content.

Livestreaming, in particular, has facilitated the creation of communities as real time interactions foster both streamer-to-viewer and viewer-to-viewer relationships (Taylor 2018). The consumption of live content enables viewers to discuss what they're viewing as it happens. This communal watching forms a social activity in which gamers experience a sense of unity with other watchers.

Live-streaming and E-Sports

Professional e-sports players utilise livestreaming to expand their audience and generate revenue from training sessions (Taylor 2018). These communities are also formed upon spectatorship (Taylor 2018). Livestreaming has expanded e-sports spectatorship, enabling fans to communicate with others and watch tournaments globally (Taylor 2018).

Toxicity in Gaming Communities

Toxicity in gaming communities is normalised and commonplace (Griffiths & McLean 2019; Bergstrom 2022). The prevalence of harassment can be partially attributed to the level of anonymity that platforms afford. Sexism is an issue rife in gaming communities (Gandolfi 2022). Strategies for mitigating harassment, such as avoiding communication with others, directly hinders women's ability to gain a sense of belonging in communities (Griffiths & McLean 2019). This sexism, as well as other types of harassment, can be suggested to foster gaming communities that are exclusionary and homogenous.

In response, women and other marginalised groups have created their own spaces. Discord server Dungeons and Darlings is an example of this (Discord 2023b). A space for tabletop gaming for women and non-binary gamers, this server is an opportunity for minority gamers to freely communicate and collaborate without fear of harassment (Discord 2023b).

Other Gaming Communities: Melbourne Indie Game Scene

The Melbourne indie game scene shares similarities to the online gaming community (Keogh 2020). The Melbourne scene is a collection of sub-communities; bonding over creativity, collaboration, and innovation (Keogh 2020). Video-game creators participate in shared spaces and information sharing, creating a community from a skill rendered non-commodifiable due to saturation (Keogh 2020). However whilst online gaming communities form from leisure, the Melbourne indie game scene exists for the survival and visibility of the community in an unsustainable industry (Keogh 2020).

References

@neverthinking 2023, not yana, 6 May, viewed 6 May 2023, <https://twitter.com/neverthinkng/status/1654660580630753283?s=20>.

#fortnite 2023, viewed 5 May 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/fortnite/>.

Allen, A, Bignill, J, De Regt, T, Kannis-Dymand, L, Mason, J, Millear, P, Raith, L, Stallman, H M, Stavropoulous, V & Wood, A 2021, 'Massively Multiplayer Online Games and Well-Being: A Systematic Literature Review', Frontiers in psychology, vol. 12, p. 698799.

Bergstrom, K 2021, 'Anti-social social gaming: community conflict in a Facebook game', Critical studies in media communication, vol. 38, no. 1, pp. 61-74.

Bowman, N, Chen, Y-S, Lin, J-H & Lin, S-F 2019, 'Setting the digital stage: Defining game streaming as an entertainment experience', Entertainment computing, vol. 31, p. 100309.

Discord 2023a, Official Fortnite, Discord, viewed 5 May 2023, <https://discord.com/invite/fortnite>.

Discord 2023b, Two fantastic women-owned Discord communities, Discord, viewed 4 May 2023, <https://discord.com/blog/iwd-2023-two-women-owned-servers>.

Gandolfi, E 2022, 'Playing is just the beginning: Social learning dynamics in game communities of inquiry', Journal of computer assisted learning, vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 1062-1076.

Griffiths, M D & McLean, L 2019, 'Female Gamers’ Experience of Online Harassment and Social Support in Online Gaming: A Qualitative Study', International journal of mental health and addiction, vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 970-994.

Kelly, S, Magor, T & Wright, A 2021, 'The Pros and Cons of Online Competitive Gaming: An Evidence-Based Approach to Assessing Young Players' Well-Being', Frontiers in psychology, vol. 12, p. 651530.

Keogh, B 2020, 'The Melbourne indie game scenes Value regimes in localized game development', in P Ruffino (ed), Independent Videogames: Cultures, Networks, Techniques and Politics, Taylor & Francis Group, eBook Central (ProQuest), pp. 209-222.

Nookipedia 2023, Main Page, Nookipedia, viewed 4 May 2023, <https://nookipedia.com/wiki/Main_Page>.

Marlatt, R 2020, 'Capitalizing on the Craze of Fortnite: Toward a Conceptual Framework for Understanding How Gamers Construct Communities of Practice', Journal of education (Boston, Mass.), vol. 200, no. 1, pp. 3-11.

Taylor, T L 2018, Watch Me Play: Twitch and the Rise of Game Live Streaming, Princeton University Press, eBook Central (ProQuest), pp. 1-23.

0 notes

Text

Beauty Filters, Beauty Standards, Body Dysmorphia, and the Discernment of Selfie Authenticity

This week's set reading by Baker explores face filters with a focus on Snapchat, the beauty industry, and psychological consequences of filtering the appearance (2020). This discussion will inquire into the impact of beauty filters on the reinforcement of rigid Western beauty ideals, body dysmorphia, and audiences' discernment of selfie authenticity. It will centre on the female experience as the use of filters is coded towards women (Baker 2020).

Origination of Filters and Rise of Beauty Filters

Snapchat Lenses marked the first mainstream launch of filters on social media (Baker 2020). Filters began as a digital adornment of selfies, often used for social connection and entertainment (Baker 2020). However, with the rise of beauty filters, the technology has shifted from a social feature to a safety blanket for self-presentation (Baker 2020).

Beauty filters refer to filters that beautify the users' appearance (Baker 2020). These filters often slim the face and nose, enlarge the eyes and lips, and clear the skin (Baker 2020). Beauty filters have become ubiquitous and easily accessible on all major appearance-based social media platforms (Baker 2020).

Filters that subvert beauty also exist (McIntyre & Miller 2022). Such filters warp the face against female Western beauty standards, such as widening the jaw and reducing the size of the eyes. However, whilst these filters seemingly reject Western beauty standards, their purpose is commonly understood to be a veil with which users can trendily reveal their 'unfiltered' face that adheres to beauty ideals.

Below is an example of these trends.

With the current celebration of seemingly un-curated content on social media, in conjunction with technological advancement, beauty filters have become close to imperceptible (Cambre & Lavrence 2020). Such filters, referred to by Cambre & Lavrence as "ambient filters", apply subtle edits to selfies (2020, p. 205630512095518). Shifting from obvious and animated edits to 'natural' editing, modern selfie filtering is easily accessible and almost undetectable.

Influencer Claudia Tihan's selfie below depicts the delicate editing of ambient filters (Tihan 2022).

Filters and Homogenised Beauty

Filters and beauty apps can be identified as a form of simplified selfie manipulation technology. Thus, the technological illiteracy of users limits selfie editing to the options beauty apps and filters afford (Baker 2020). Whilst beauty apps offer a range of pre-set options for editing; filters are further simplified, often limiting users to a single pre-set edit. Altering faces to a limited definition of beauty, the ubiquity of filters has resulted in homogenous appearances online (Cambre & Lavrence 2020).

The pre-set editing options also reflect ideals of thinness and whiteness, reinforcing rigid Western beauty standards (Baker 2020; McIntyre & Miller 2022). Filters' imposing of ideals of lighter skin, lighter eyes, and smaller noses onto women of colour is particularly problematic; camouflaging identity erasure as 'beautification' (Baker 2020). The existence of beauty filters and their coding towards women also reinforces the aesthetic labour that women are expected to undertake when presenting themselves online (Baker 2020).

Filters and Body Dysmorphia

Achieving an unachievable beauty standard has now become possible through the use of filters (Baker 2020). A 2022 study found that a significant motivation behind users' engagement with filters is presenting themselves as their idealised self (Barhorst et al. 2022). The accessibility and normalisation of beauty filters has created a reliance on beautification technologies for self-presentation (Barhorst et al. 2022; McIntyre & Miller 2022). However, the internalisation of a filtered appearance contribute to a dissonance between the online presentation and offline self (Coy-Dibley 2016; McIntyre & Miller 2022). Users conduct upwards social comparison with their filtered selves, ultimately a presentation of themselves beautified to meet an unattainable standard (Coy-Dibley 2016). This can lead to appearance dissatisfaction, which is a precursor for body dysmorphia and cosmetic-surgery seeking behaviours (Coy-Dibley 2016; McIntyre & Miller 2022).

Digital citizenship, Filters, and the Digital Forensic Gaze

The ubiquity of ambient filters in the current social media sphere has created a space in which intensive looking is required to determine selfie authenticity (Cambre & Lavrence 2020). Cambre & Lavrence's term "digital forensic gaze" describes this style of looking, in which audiences attempt to identify tells of filtering such as glitching and warping (2020, p. 205630512095518). This style of audience interaction with content has become commonplace as filter technologies continue to improve (Cambre & Lavrence 2020). This discernment of whether selfies are filtered or real is a behaviour which can shield users from negative effects on body satisfaction (McLean, Paxton & Rodgers 2022). The ability to critically evaluate the authenticity of selfies prevents the internalisation of unachievable ideals (McLean, Paxton & Rodgers 2022).

In reference to digital citizenship, it can be suggested users with a well-developed digital forensic gaze have a responsibility to educate others on filtering practices. Spaces are created on social media to compare public figures' online presentations with their offline selves to counter the effect of selfies indiscernibly filtered to perfection.

An example of these spaces is @/celebface on Instagram, which compares celebrities' subtly filtered selfies with raw photographs.

instagram

Such accounts serve to educate other users on the ubiquity and undetectability of modern selfie filtering, giving users their own lens to participate in the digital forensic gaze.

References

@c4ndel44 2023, 21 April, viewed 29 April 2023, <https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS8TfpQLF/ >.

@celebface 2019, November 14, viewed 29 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/B40nsW3HTsn/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y= >.

Cambre, C & Lavrence, C 2020, '"Do I Look Like My Selfie?”: Filters and the Digital-Forensic Gaze', Social media + society, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 205630512095518.

Coy-Dibley, I 2016, '“Digitized Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image', Palgrave communications, vol. 2, no. 1, p. 16040.

Baker, J 2020, 'Making up on mobile: The pretty filters and ugly implications on Snapchat', Fashion, Style, & Popular Culture, vol. 7, no. 2&3, pp. 207-221.

Barhorst, J B, Javornik, A, Marder, B, Marshall, P, McLean, G, Rogers, Y & Warlop, L 2022, '‘What lies behind the filter?’ Uncovering the motivations for using augmented reality (AR) face filters on social media and their effect on well-being', Computers in human behaviour, vol. 128, p. 107126.

McIntyre, J & Miller, L A 2022, 'From surgery to Cyborgs: a thematic analysis of popular media commentary on Instagram filters', Feminist Media Studies, vol. (ahead-of-print), no. (ahead-of-print), pp. 1-17.

McLean, S A, Paxton, S J & Rodgers, R F 2022, '“My critical filter buffers your app filter”: Social media literacy as a protective factor for body image', Body image, vol. 40, pp. 158-164.

Tihan, C 2022, claudiatihan, viewed 29 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/s/aGlnaGxpZ2h0OjE3ODk2NjIzOTE2OTgwOTgy?story_media_id=2759131310419851775&igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=>.

0 notes

Text

Visibility, Female Self-Presentation, and Public Health

Duffy & Meisner explore issues related to algorithmic visibility and the actions taken by content creators to achieve increased visibility online (2022). This discussion will focus on the relationship between visibility, female self-presentation, and related public health issues.

Microcelebrity and Visibility Labour

Microcelebrity is a deliberate practice in which everyday media users utilise self-branding techniques on social media to build fame (Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020). Visibility labour refers to the unpaid activities that users unknowingly participate in to increase popularity on social media (Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020).

Microcelebrities' content creation careers are reliant on the visibility that a platform affords them (Duffy & Meisner 2022). Platform specific strategies for attaining higher visibility are discussed amongst content creators, often discussing how to navigate algorithms to increase visibility (Duffy & Meisner 2022). Below is an example of the visibility strategies shared within the content creation community.

Aesthetic Templates

A method of gaining visibility on appearance-based social media platforms is adhering to aesthetic templates (Foster 2022). Aesthetic templates refer to the visual attributes that receive increased attention online; including poses, accessories, body editing, and body modifications.

Aesthetic templates comprise specific appearance ideals (Foster 2022). Feminine ideals centre around enhanced femininity; celebrating features such as large lips, thin noses, high cheekbones, and an hourglass body shape (Cowart & Lefebvre 2022; Foster 2022).

The work dedicated to self-presentation to conform to aesthetic templates is referred to as aesthetic labour (Sarah & Dobson 2016; Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020). Conformity to aesthetic templates and ideals has resulted in women with high visibility sharing similar appearances, which in some cases are achieved by cosmetic procedures (Coward & Lefebvre 2022; Foster 2022).

This can be observed below.

instagram

instagram

Pornification and Sexualised Labour

It can be posited that some women are accentuating their adherence to feminine aesthetic templates through highly sexualised self-presentation (Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020). In reference to visibility on social media, this strategy of pornification is dominant due to its success in garnering attention (Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020).

@LemyBeauty on Instagram exemplifies the use of pornified self-presentation to attract visibility online. In conjunction with adhering to aesthetic templates through posing, body editing, and meeting beauty ideals; the influencer presents a sexualised version of self which emulates aesthetics of commercial pornography.

As online engagement is commodified, adopting a 'porn-chic' self-presentation strategy for product promotion increases monetary gain for content creators (Drenten, Gurreri & Tyler 2020).

instagram

Public Health: Identity Dissonance, Body Dysmorphia, and Digital Citizenship

The attribution of visibility through adherence to aesthetic templates drives desire to conform to unrealistic beauty ideals (Cowart & Lefebvre 2022). The feminine aesthetic template is often unattainable by natural means, achievable only through cosmetic procedures (Cowart & Lefebvre 2022). Attempts to align with aesthetic templates can create a dissonance between online presentation and the offline self, which may ultimately lead to body dysmorphia and an increased desire to change (Cowart & Lefebvre 2022).

The glamorisation of cosmetic procedures by microcelebrities perpetuates an unrealistic beauty standard for women (Burns, Goode & Rodner 2022). Simultaneously, cosmetic procedures are normalised on social media by practitioners as a method of self-promotion (Dorfman et al. 2018). The unregulated advertisement of cosmetic procedures in conjunction with the celebration of unattainable ideals contribute to solidifying the relationship between social media and body dysmorphia (Dorfman et al. 2018; Burns, Goode & Rodner 2022).

As social media users are the heavily sought-after audience within the attention economy, users have agency over the types of content that receive visibility (Sarah & Dobson 2016). From this, it can be suggested that the attributes which form aesthetic templates can be modified by users engaging with content which depicts naturally attainable appearances online.

References

@alix_earle 2022, 28 July, viewed 18 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/Cgh-WLRpm9U/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=>.

@amrezy 2023, 27 March, viewed 18 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CqQxK3NJ8nP/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=>.

@amymarietta 2023, 13 March, viewed 17 April 2023, <https://vt.tiktok.com/ZS87eRuo2/>.

@lemybeauty 2021, 17 July, viewed 18 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CRZkxEFnCZ0/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y=>.

Burns, Z, Goode, A & Rodner, V 2022, '“Is it all just lip service?”: on Instagram and the normalisation of the cosmetic servicescape', The Journal of services marketing, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 44-58.

Carah, N & Dobson, A 2016, 'Algorithmic Hotness: Young Women's "Promotion" and "Reconnaissance" Work via Social Media Body Images', Social Media + Society, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. p.205630511667288.

Cowart, K & Lefebvre, S 2022, 'An investigation of influencer body enhancement and brand endorsement', The Journal of services marketing, vol. 36, no. 1, pp. 59-72.

Dorfman, R G, Fine, N A, Mahmood, E, Schierle, C F & Vaca, E E 2018, 'Plastic Surgery-Related Hashtag Utilization on Instagram: Implications for Education and Marketing', Aesthetic Surgery Journal, vol. 38, no. 3, pp. 332-338.

Drenten, J, Gurrieri, L & Tyler, M 2020, 'Sexualized labour in digital culture: Instagram influencers, porn chic and the monetization of attention', Gender, work, and organization, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 41-66.

Duffy, B E & Meisner, C 2022, 'Platform governance at the margins: Social media creators' experiences with algorithmic (in)visibility', Media, culture & society, vol. 45, no. 2, pp. 285-304.

Foster, J 2022, '“It’s All About the Look”: Making Sense of Appearance, Attractiveness, and Authenticity Online', Social Media + Society, vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 205630512211387.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slow Fashion, Digital Citizenship, and Greenwashing

This week's set reading by Domingos et al. explores the slow fashion movement and consumer values, attitudes, and behaviour intentions towards slow fashion (2022). The concept of fast fashion must first be introduced to provide context for the slow fashion movement.

Fast fashion is the production of clothes based on principles of trendiness, speed-to-market, and low-cost (Hall 2018). The clothes are often low quality and produced through unethical labour (Geiger & Keller 2018). Main environmental consequences of fast fashion are landfill contribution, water pollution, and greenhouse gases from the production process (Geiger & Keller 2018; Jung, Kim & Lee 2021). Fast fashion is aligned with the glamorisation of overconsumption.

Slow fashion is a movement which rejects fast fashion and promotes conscious consumption of high-quality clothes (Hall 2018). It centres on consumers' awareness of the social and environmental impact of garment manufacturing (Hall 2018). Domingos et al. concluded that members of the slow fashion community value exclusivity, individuality, and timelessness in clothing (2022). They also have an interest in the ethical treatment of workers and the environment during garment production (Domingos et al. 2022).

The Online Slow Fashion Community

The online slow fashion community is a space to share content related to ethically and sustainably obtained clothing (Lee & Weder 2021). The slow fashion community encompasses multiple smaller micro-publics. The thrifting micro-public share their second-hand garment purchases. Trends have arisen within this group, such as the hashtag #thriftwithme which has 1.7 billion views on TikTok at the time of writing.

Closely aligned is the upcycling micro-public, which refers to the redesigning and alteration of second-hand clothes into unique pieces.

Thrifting and upcycling contribute to sustainable fashion through the reuse of existing clothing. Supporters of the slow fashion movement juxtapose the values of overconsumption and trendiness upheld by the mainstream fashion community (Lee & Weder 2021).

The Slow Fashion Movement and Digital Citizenship

The slow fashion movement and digital citizenship share key principles of personal responsibility, ethical and respectful treatment of others, and rejection of overconsumption (Geiger & Keller 2018).

The existence of the online slow fashion community is also a display of digital citizenship. Members utilise the platform afforded by technology to advocate for a more sustainable approach to fashion (Choi & Cristol 2021). These demands for ethicality and environmental consideration have engendered tangible change, driving various fast fashion brands to adopt green initiatives.

Greenwashing

Sustainability is often commodified in an attempt to sell to the slow fashion community (Adamkiewicz et al. 2022). Referred to as greenwashing, fast fashion companies falsely present themselves as ethical and eco-conscious whilst implementing little change to their operations to reduce their environmental impact (Adamkiewicz et al. 2022).

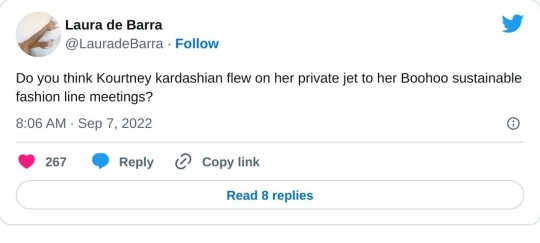

Fast fashion brand Boohoo exemplifies this. Boohoo is owned by Boohoo Group PLC, one of the world's largest fast fashion companies with an annual revenue of 1.98b GBP in 2022 (Boohoo Group PLC 2022). Boohoo announced a partnership with Kourtney Kardashian in 2022 and her collaboration on a sustainable fashion line. The partnership was heavily promoted on social media.

Whilst Boohoo portrayed their collaboration with Kourtney Kardashian as an opportunity to educate others on the impact of fast fashion, the slow fashion community criticised the irony of discouraging overconsumption whilst launching a new line of clothes. The line also includes garments made from unrecyclable materials such as polyurethane which further contradicts their claims of sustainability (Boohoo 2023).

Digital citizenship is displayed through the slow fashion community's online advocacy for a more ethical fashion industry. Whilst greenwashing is a performative practice, its occurrence exemplifies that change can be enacted as a result of digital communities.

References

@boohoo 2022, 17 September, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/reel/CiK2_DIoBSc/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=22ee4000-0c21-48e8-8385-eecccf5295e8>.

@annaime 2022, 27 June, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://www.tiktok.com/@annaime/video/7113665683921046827?_r=1&_t=8b9uVEVyoHB>.

@melxdivine 2023, 15 March, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://www.tiktok.com/@melxdivine/video/7210550880066669866?_r=1&_t=8bHvNDrZBKb>.

Adamkiewicz, I, Adamkiewicz, J, Kochańska, E & Łukasik, R M 2022, 'Greenwashing and sustainable fashion industry', Current opinion in green and sustainable chemistry, vol. 38, pp. 100710.

Boohoo 2023, KOURTNEY KARDASHIAN BARKER FAUX LEATHER OVERCOAT, Boohoo, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://au.boohoo.com/kourtney-kardashian-barker-faux-leather-overcoat/GZZ20024.html>.

Boohoo Group PLC 2022, Annual Report and Accounts 2022, Boohoo Group PLC, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://www.boohooplc.com/sites/boohoo-corp/files/2022-05/boohoo-com-plc-annual-report-2022.pdf>.

Choi, M & Cristol, D 2021, 'Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education', Theory Into Practice, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 361-370.

De Barra, L 2022, Laura de Barra, 6:06PM, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://twitter.com/lauradebarra/status/1567424165266743301?s=46&t=dBWcXxGaUY1mSknxzPUwOA>.

Domingos, M, Faria, S & Vale, V T 2022, 'Slow Fashion Consumer Behavior: A Literature Review', Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 2860.

Geiger, S M & Keller, J 2018, 'Shopping for Clothes and Sensitivity to the Suffering of Others: The Role of Compassion and Values in Sustainable Fashion Consumption', Environment and behavior, vol. 50, no. 10, pp. 1119-1144.

Hall, J 2018, 'Digital Kimono: Fast Fashion, Slow Fashion?', Fashion theory, vol. 22, no. 3, pp. 283-307.

Lee, E & Weder, F 2021, 'Framing Sustainable Fashion Concepts on Social Media. An Analysis of #slowfashionaustralia Instagram Posts and Post-COVID Visions of the Future', Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 17, pp.9976.

Lee, Y, Kim, I & Jung, H J 2021, 'Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing', Sustainability (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 1208.

Rai, R 2022, Reena Rai, 6:15PM, viewed 7 April 2023, <https://twitter.com/reenarai_/status/1567426291405561856?s=46&t=dBWcXxGaUY1mSknxzPUwOA>.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Digital Citizenship: Hashtag Publics, Political Engagement, and Activism

This week's set reading discusses digital citizenship, intersectionality, and participatory democracy. Choi and Cristol explore proposed methods for informed and engaged digital citizens to solve social inequities to achieve participatory democracy (2021).

Digital citizenship refers to the safe and ethical use of technology, and the rights and responsibilities that are afforded by its use. Choi and Cristol denote participatory democracy as a desired outcome of digital citizenship (2021). Participatory democracy is achieved by daily acts of "expressive political participation and personalised politics" (Choi & Cristol 2021). Under these requirements, participatory democracy on social media requires users to share the intentions of their political action and express personalised views (Choi & Cristol 2021).

Social media has enabled individuals' experiences to be shared with others. In an activism context, this connection with others facilitates the formation of a collective with a common political interest. Online activist communities develop with the political strength to engender change through collective action (Choi & Cristol 2021). The existence of digital activist communities is suggested to be essential to the realisation of a participatory democracy online (Choi & Cristol 2021).

Activist communities can form under hashtags on social media (Kim & Lee 2022). Hashtag activism facilitates participatory democracy as individuals can contribute to social movements by sharing both personal and political viewpoints (Choi & Cristol 2021). Communities form from hashtag activism as individuals connect over interest in a common cause and empowers collective action (Kim & Lee 2022).

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement continues to be an example of hashtag activism and participatory democracy. The #BLM hashtag is an online space for social justice activists to participate in discussions about the issues of police brutality and systemic racism (Bush & Satchel 2021). It also provides education and alternative representations of the black community to counter negative stereotypes in attempt to engender social change (Bush & Satchel 2021).

Black Lives Matter formed in 2013 to protest police brutality against the black community in the United States (Bush & Satchel 2021). In 2020, the BLM community grew exponentially in response to the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor (Bush & Satchel 2021). The community utilised social media to boost awareness of the crimes and share information on the BLM movement. The activity of the community under the #BLM hashtag increased the visibility of the movement and mobilised those with an interest in social justice to form a collective. Online activism translated into physical displays as protests were organised during the peak of mobilisation, and from this the movement gained international recognition (Bush & Satchel 2021).

There are currently 26.4 million posts under #BlackLivesMatter on Instagram (Instagram 2023). This space is adopted by activists to disseminate messages regarding police brutality and for supporters to express their solidarity with the movement.

instagram

The use of online spaces also enables political issues to bypass physical borders; fostering larger, international digital communities of activists. The #BLM hashtag formed a global collective of activists and allies with a unified goal of ending police brutality.

This visibility also instigated the development of an Australian context of the BLM movement. Australian activists utilised the virality of the American context to amplify awareness of police brutality towards Indigenous Australians (Abad 2021).

instagram

The public protest of systemic racism and police brutality towards Indigenous Australians also received traditional media coverage. 60 Minutes conducted an investigation into Indigenous Australian deaths in police custody (60 Minutes Australia 2023).

youtube

Digital citizenship in reference to political engagement has facilitated the rise of grassroots activist movements such as BLM (Choi & Cristol 2021). With the ability to evoke positive changes using social media, activism relies less heavily on traditional democratic pathways (Choi & Cristol 2021). This is particularly important for marginalised groups due to barriers to political participation in these traditional spaces (Choi & Cristol 2021).

References

@soupformyfamilyatlanta 2023, 27 March, viewed 28 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CqQWT6JO-0C/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=2d03c678-8d67-4bac-8f33-d683e04ca071>.

@squidly69 2020, June 13, viewed 27 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/p/CBXsn_LguKT/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=376d87d4-ef96-485d-a3c4-d91537974861>.

60 Minutes Australia 2023, The scandal surrounding the shocking number of Indigenous deaths in prison | 60 Minutes Australia, 5 March 2023, viewed 27 March 2023, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WxALeEVHG5s>.

Abad, G S 2021, Why does the BLM movement matter in Australia?, United Nations Association of Australia, viewed 27 March 2023, <https://www.unaa.org.au/2021/11/03/why-does-the-blm-movement-matter-in-australia/>.

Bush, N V & Satchel, R M 2021, 'SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, MEDIA, AND DISCOURSE Using Social Media to Challenge Racist Policing Practices and Mainstream Media Representations', in N Crick (ed), The rhetoric of social movements: networks, power, and new media, Routledge, eBook Central (ProQuest), pp. 172-190.

Choi, M & Cristol, D 2021, 'Digital citizenship with intersectionality lens: Towards participatory democracy driven digital citizenship education', Theory Into Practice, vol. 60, no. 4, pp. 361-370.

Instagram 2023, #blacklivesmatter, viewed 27 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/blacklivesmatter/>.

Kim, Y & Lee, S 2022, 'ShoutYourAbortion on Instagram: Exploring the Visual Representation of Hashtag Movement and the Public’s Responses', Sage Open, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 215824402210933

0 notes

Text

Exploring the Relationship between Social Media and Reality TV

This week's reading 'Reality Television: The TV phenomenon that changed the world' by Ruth Deller explores the relationship between reality TV and social media (Deller 2019). Deller analyses two areas related to this relationship, the self and online communities (2019).

Reality TV and The Self

Prior to participatory media, reality TV was the only media platform ordinary individuals had access to for self-branding (Deller 2019). Microcelebrity practices, which refers to the purposeful branding of oneself online, is suggested by Deller to have originated from reality TV (2019). Modern microcelebrity has developed as technologies have afforded ordinary individuals with the tools to brand themselves (Djafarova & Trofimenko 2019). Vlogging and self-disclosure closely mimic the practices conventional to reality TV, with each attempting to portray a sense of authenticity (Deller 2019).

Reality TV participants become famous to the specific audience who watch the season, and participants can utilise social media to convert these fans into their own supporters post-broadcast (Hargraves 2018).

Married at First Sight couple Martha Kalifatidis and Michael Brunelli exemplify this.

After featuring on the 2018 season, the couple have amassed a combined total of 1 million followers on Instagram. Both figures engaged in microcelebrity practices to continue to brand themselves after the season aired. Kalifatidis, in particular, self-discloses elements of her life such as her pregnancy and experiences with Brunelli through posting day-in-the-life style vlogs.

The couple also receive promotional deals with brands, similar to influencers.

Social media has transformed reality TV into a pathway to a career as a public figure that extends beyond the show (Deller 2019).

Social media has also afforded reality TV participants more agency over their presentation during and after broadcast (Deller 2019). Participants can adopt their platforms to share their perspectives on their representations in reality TV, and provide a seemingly unfiltered presentation of themselves that is perceived as more reputable by the audience (Deller 2019). Whilst both reality TV and social media are curated, participants have agency over their own presentation on social media (Deller 2019; Djafarova & Trofimenko 2019).

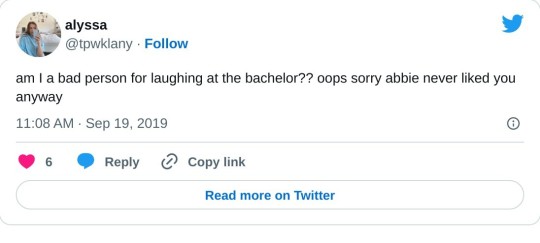

Abbie Chatfield utilised social media to both share her experiences and rebrand after her debut on reality TV. Chatfield was presented as the villain of the 2019 season of The Bachelor and received significant hate on social media.

After the season finale's air, Chatfield utilised Instagram to share her experience of the show which heavily contrasted her portrayal on air. This is written in the caption of her post below.

instagram

Chatfield utilised her social media platform to separate herself from The Bachelor and currently has a career as a radio presenter, TV personality, and podcaster. She now presents herself on social media as a body-positive, sex-positive mental health advocate.

Reality TV and Online Communities

The use of social media has shifted reality TV consumption into a communal activity in which viewers can actively participate (Stewart 2020). A key element of watching reality TV is its liveness (Stewart 2020). Watching live broadcasts creates a sense of unity amongst viewers because they know that others in the community are watching at the same time (Deller 2019).

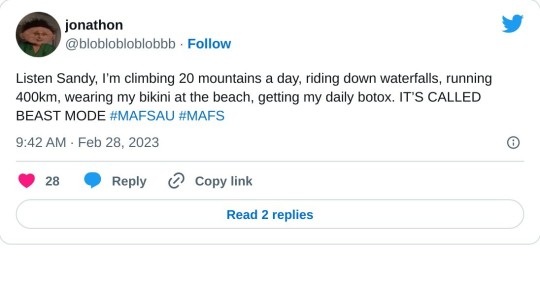

The following tweets are from a live broadcast of a recent scandal in the current Married at First Sight Australia season.

Social media has connected these viewers and enabled them to form online communities where they can discuss what they're watching as it happens (Stewart 2020). Social media discussions are the tangible product of live reality TV's collective viewing experience.

The adoption of social media as a space for fans to congregate has created digital communities which extend past the liveness of reality TV (Deller 2019). Online communities of reality TV fans stay active for continued discussion and sharing of memes and reactions to the content viewed prior. Fans usually adopt fan-created spaces online and approach these spaces with humour (Deller 2019).

'Love Island Memes' is a fan-created Facebook group in which the Love Island UK community can continue to discuss the series outside of the show's broadcast times.

These accounts depict how social media has extended the congregation of fans into communities which now exist beyond just second-screen commentary.

References @abbiechatfield 2019, Abbie Chatfield, 24 September, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/abbiechatfield/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=65466b16-5ece-4797-9efe-afa2fb8ebcd4>.

@bloblobloblobbb 2023, jonathon, 28 February, 8:42PM, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://twitter.com/bloblobloblobbb/status/1630503599125200898>.

@marthaa_k 2022, Martha Kalifatidis, 1 July, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/reel/CfdxhPrgvTg/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link>.

@marthaa_k 2023, Martha Kalifatidis, 9 February, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://www.instagram.com/reel/CobwYRMt6lM/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link>

@PK_APOSTOLI 2023, Apolo, 28 February, 8:53PM, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://twitter.com/PK_APOSTOLI/status/1630506519556128769>

@shanaedanii 2019, ♡, 19 September, 9:02PM, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://twitter.com/shanaedanii/status/1174639848474300416>.

@tpwklany 2019, alyssa, 19 September, 9:08PM, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://twitter.com/tpwklany/status/1174641524329480194>.

Deller, R A 2019, Reality Television: The TV phenomenon that changed the world, Emerald Publishing, eBook Central (ProQuest), pp. 153-175.'

Djafarova, E & Trofimenko, O 2019, ''Instafamous' - credibility and self-presentation of micro-celebrities on social media', Information, communication & society, vol. 22, no. 10, pp.1432-1446.

Hargraves, H 2018, ''For the first time in ________ history...': microcelebrity and/as historicity in reality TV competitions', Celebrity Studies, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 503-518.

Home 2023?, It's a Lot Podcast, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://www.itsalotpodcast.com>.

Rhodes, C 2021, Chelsea Rhodes, 19 August, viewed 25 March 2023, <https://www.facebook.com/groups/loveislandmemes/permalink/1367573150364046/>.

Stewart, M 2020, 'Live tweeting, reality TV and the nation', International journal of cultural studies, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 352-367.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tumblr as a Space for Online Communities

Social media enables people to congregate and discuss topics in a digital space. Digital communities or micro-publics form on social media, and different platforms have features that can create a more suitable space for certain micro-publics. Tumblr exemplifies this as it has a reputation for accepting marginalised communities (Miller, Reif & Taddicken 2022).

This week's set reading discussed selfie taking, the body positivity movement on social media, and the community formed under the 'body positivity' hashtag on Tumblr (Miller, Reif & Taddicken 2022). Miller, Reif & Taddicken contend that those who take selfies, young women in particular, may feel pressured to present themselves in a way to adhere to beauty ideals (2022). Social media communities that revolve around the rejection and redefinition of beauty ideals have been formed in response to this pressure. The reading focuses on the community around the 'body positivity' hashtag on Tumblr, which shares an interest in rejecting beauty standards and celebrating non-conventional bodies online (Miller, Reif & Taddicken 2022). Whilst Miller, Reif & Taddicken's study focuses on women members of Tumblr's body positivity community in 2017; current posts under the hashtag are inclusive of men, non-binary, and trans individuals (2022).

Tumblr's user base is often supportive in comparison to other social media platforms, which establishes a space that is safe for self-disclosure (Bianchi, Cash & Fabbricatore 2022). Tumblr's openness to nudity prior to the 2018 NSFW ban also differentiated itself from other platforms (Miller, Reif & Taddicken 2022). The acceptance of this content enabled the body positivity community to share selfies and engage in discussion without breaching platform policies. However, the implementation of the ban impacted the suitability of Tumblr and the community has adopted other platforms since (Miller, Reif & Taddicken 2022).

Tumblr's anonymity and non-personal profile format increases the inclusivity of the platform (Bianchi, Cash & Fabbricatore 2022). Anonymity provides freedom from surveillance, which allows for protected participation due to users' fear of offline consequences (Flinchum, Kruse, & Norris 2018). This element of Tumblr makes it a safer space to participate in online, particularly when discussing sensitive topics such as activism (Keller 2019, Calhoun 2020). Micro-publics of feminist and social justice activists are prominent on Tumblr and coexist within a larger community of users interested in activism.

Linked below are two posts from the activism community. The first is an expression of opinion opposing the overturning of Roe v. Wade, and the second is encouraging other users to protest the erasure of segregation from the public school curriculum in Florida, USA.

It can be argued that these users are comfortable sharing personal experience and political opinion on Tumblr due to anonymity (Flinchum, Kruse, & Norris 2018). Feminist activism, in particular, is popular on Tumblr due to the supportive community and level of privacy the platform affords (Keller 2019). Similarly, black activists and allies often utilise Tumblr to engage in everyday political discourse in a more intimate setting (Calhoun 2020).

Tumblr's unique properties and user base establish the platform as a protective space for marginalised micro-publics. The decline in the body positivity community's use of Tumblr exemplifies how users will adopt the platforms that are most suitable for their desired discourse.

References

Bianci, M, Caso, D & Fabbricatore, R 2022, 'Tumblr Facts : Antecedents of Self-Disclosure across Different Social Networking Sites', European journal of investigation in health, psychology and education, vol. 12, no. 9, pp. 1257-1271.

Calhoun, K 2020, 'CHAPTER 4 Blackout, Black Excellence, Black Power: Strategies of Everyday Online Activism on Black Tumblr', in A Cho, I N Hoch, A McCracken & L Stein (eds), a tumblr book: platform and cultures, University of Michigan Press, pp. 48-62.

Flinchum, J R, Kruse, L M, Norris, D R 2018, 'Social Media as a Public Sphere? Politics on Social Media', The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 62-84.

Keller, J 2019, '“Oh, She’s a Tumblr Feminist”: Exploring the Platform Vernacular of Girls’ Social Media Feminisms', social media + society, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 205630511986744.

Miller, I, Reif, A & Taddicken, M 2022, '"Love the Skin You're In": An Analysis of Women's Self-Presentation and User Reactions to Selfies Using the Tumblr Hashtag #bodypositive', Mass communication & society, vol. ahead-of-print,, no. ahead-of-print, pp. 1-24.

0 notes

Text

Social Media Platforms as Ideal Public Spheres

Three traits cornerstone Habermas' notion of an ideal public sphere; "unlimited access to information, equal and protected participation, and the absence of institutional influence” (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018). There is debate on whether social media platforms align with these requirements.

Arguments For:

Social media is an interactive space which empowers communication amongst active participants. Social media has democratised media content production, enabling equal participation by providing users with the tools necessary to independently broadcast their voice. This redistribution of power has established a media space where communication is on a peer-to-peer level rather than one-to-many (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018). This has empowered individuals to engage in discourse publicly.

The reliance on traditional media gatekeepers has been removed by social media platforms. The equal contribution of the public to the media landscape has decreased the influence of institutions (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018). Moreover, unlike traditional media, there are no gatekeepers on social media platforms which permit or deny the posting of content. This fulfils the requirement of a space absent of institutional influence.

Users also have unlimited access to all information available on social media platforms (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018).

Whilst social media fundamentally meets the requirements of a public sphere, its ideality is inhibited by multiple factors.

Arguments Against:

Unlimited access to information

Users are segregated into niche online communities and are not exposed to the unlimited information available on social media. Algorithms analyse user data to predict and present content which aligns with an individual’s interests. Users are repeatedly exposed to media which affirms pre-existing viewpoints, forming a filter bubble (Belavadi et. al 2020). The online community is separated into smaller ideologically homophilic circles, constructing echo chambers of opinion (Belavadi et. al 2020). Automated content personalisation ultimately limits information access by sheltering users from exposure to opposing viewpoints.

Equal and protected participation

The exclusion of individuals from social media often arises as a consequence of the digital divide, which refers to the discrepancies which prevent certain groups' equal use of online spaces. Primary factors are the lack of access to the required technology, such as a stable internet connection and personal devices, and one's degree of competence with these technologies (James 2021). As individuals have varying access and competence which limits them in different ways, social media is not a space in which all individuals can equally participate.

Users are not protected when participating in discourse on social media. As mentioned in the Flinchum, Kruse & Norris reading; surveillance on social media can result in online activity impacting users’ life offline. This is reflected by the offline consequences faced by NBA player Kyrie Irving’s career after posting a link to an antisemetic film on Twitter in 2022 (Ganguli & Sopan 2022). Irving received an eight-game suspension by the Brooklyn Nets, and Nike terminated his contract 11 months prior to its official expiration (Doston & Vera 2022; Ganguli & Sopan 2022). Exemplified by Irving’s financial and reputational damage; users are held accountable offline for content shared on social media. Users may alter or limit their online presence to not reflect their views and reduce the risk of offline consequences.

The following video discusses the incident further and highlights the damage to Irving's reputation.

youtube

Source: Good Morning America 2022

Government surveillance is also an issue for protected participation on social media. This is exemplified by Douyin, the predecessor of TikTok launched for the Chinese market. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) monitors online activity and enforces strict internet censorship restrictions (Gamso 2021). Government surveillance prevents protected participation as Douyin users must limit their online expression, particularly on political issues, to avoid legal prosecution.

The following video briefly explains the CCP's internet censorship practices.

youtube

Source: South China Morning Post 2020

Absence of institutional influence

The commodification of user information breaches the requirement of a space free from institutional influence. Data is collected by platform owners and offered as targeted marketing to external organisations. Meta Inc., parent company of Facebook and Instagram, generated $116.6b USD in revenue in 2022 primarily from promotion (Meta Inc. 2022). Platforms themselves benefit economically from their existence, profiting from the data generated by users’ self expression. Thus, social media is not free from economic institutional influence.

Attainability of the Ideal Public Sphere

The reading acknowledges doubts on the attainability of the public sphere outside of theory (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018). Equal participation of all individuals requires the removal of all barriers which often stem from prominent sociocultural and economic issues in society (Flinchum, Kruse & Norris 2018). Thus, the ideal public sphere theorised by Habermas may be unattainable in both the digital and physical space.

Reference List

Belavadi, P, Burbach, L, Calero Valdez, A, Nakayama, J, Plettenberg, N & Ziefle, M 2020, 'User Behavior and Awareness of Filter Bubbles in Social Media', in V G Duffy (ed), Digital Human Modeling and Applications in Health, Safety, Ergonomics and Risk Management. Human Communication, Organization and Work, Springer International Publishing, SpringerLink, pp. 81-92.

Dotson, K & Vera, A 2022, Kyrie Irving returns to the Brooklyn Nets after serving 8-game suspension, CNN, viewed 2 March 2023, <https://edition.cnn.com/2022/11/20/us/kyrie-irving-return-brooklyn-nets/index.html >.

Flinchum, J R, Kruse, L M, Norris, D R 2018, 'Social Media as a Public Sphere? Politics on Social Media', The Sociological Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 62-84.

Gamso, J 2021, 'Is China exporting media censorship? China’s rise, media freedoms, and democracy', European journal of international relations, vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 858-883.

Ganguli, T & Sopan, D 2022, What to Know About Irving’s Antisemitic Movie Post and the Fallout, New York Times, viewed 2 March 2023, <https://www.nytimes.com/article/kyrie-irving-antisemitic.html>.

Good Morning America, 2022, Kyrie Irving causes controversy by sharing anti-Semitic film, viewed 10 March 2023, <Kyrie Irving causes controversy by sharing anti-Semitic film>.

James, J 2021, New perspectives on current development policy : COVID-19, the digital divide, and state internet regulation, Springer International Publishing AG, p.23-35.

Meta Inc., 2022, Meta Reports Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2022 Results, Meta Investor Relations, viewed 10 March 2023, <https://s21.q4cdn.com/399680738/files/doc_financials/2022/q4/Meta-12.31.2022-Exhibit-99.1-FINAL.pdf>.South China Morning Post 2020, How China censors the internet, viewed 11 March 2023, <How China censors the internet>

3 notes

·

View notes