Photo

Killing Eve star Jodie Comer claims Broadway as her own in her tour de force performance of Prima Facie, a scalding indictment of the law and its limits opening tonight at the Golden Theatre.

Comer plays Tessa, a young, working class Liverpool woman who has become one of London’s most promising defense lawyers through sheer intelligence and needle-sharp courtroom instincts. Her specialty – perhaps, or perhaps not, foisted upon her by the cynical male superiors who run things in ways Tessa only slowly comprehends – is the defense of men charged with sexual assault.

Tessa’s outwardly compassionate, woman-to-woman cross-examinations of assault victims are no less effective for their sympathetic overtones, perhaps more so. Her probing questions and geiger-counter instincts for finding the hidden bombs that will blow a victim’s story to smithereens make Tessa an invaluable force in the courtroom.

Throughout the early portion of the play, Comer shows us Tessa’s razor skills as she demonstrates the cross-examination techniques (and narrates their finer points simultaneously). We see her take apart a pompous police detective, and a nervous sexual assault victim. Tessa might have fleeting pangs of guilt for the latter, and unbridled glee at dismantling the former, but for the most part she sees her job as just that – a necessary cog in the machinery of justice, with each player in a courtroom’s dramatics assigned a crucial role to make the system play out as fairly as possible. It’s not a perfect system, she knows, but even when it appears horribly unfair, it’s the best we got.

Tessa’s perceptions change, and her well-assembled world crumbles, in a blink. She’s recently become romantically interested in a coworker, a gentle-demeanored fellow attorney. After a shared late night tryst in the office, the two decide to have a proper date, with food and drinks and maybe, or more likely assuredly, a trip back to Tessa’s apartment for more than a nightcap.

Only something begins to go terribly wrong. As they lay in bed, Tessa begins to feel dizzy and queasy, and is soon vomiting in her bathroom. When the coworker carries her back to bed, and despite her protests (she’s feeling gross and ill and suddenly terrified) the man ignores her pleas, pins her down, covers her mouth and violently, painfully rapes her.

Tessa knows from professional experience what will follow, the questions and the insinuations. Unlike the women she has cross-examined, Tessa knows every hidden trap the law has in wait, and yet even she can’t avoid them. Comer recounts this legal horror step-by-step, letting the audience see the withering of self-confidence and increasing panic as days drag into weeks, months and years between the rape and Tessa’s day in court.

Directed with energy and empathy by Justin Martin (The Crown, The Inheritance, the upcoming Stranger Things: The First Shadow), Comer is rarely still – and when she is, there’s purpose behind it – moving office desks and a chair into any number of configurations and uses. (The set is designed by Miriam Buether, as are Tessa’s costumes – mostly lawyerly attire with the sole exception of a garish rose-pink blouse gifted, poignantly, from Tessa’s working-class Liverpool mom.)

When the play (100 minutes, no intermission) enters its latter half and Tessa’s long-in-coming court date arrives, Prima Facie rarely lets us raise our hopes or even, really, challenges our expectations – most of us have been prepared by too many Law & Order: SVUs. The drama is in how Tessa deals with the crumbling of her ideals and the smashing of her self-delusions, and in how Comer can so vividly, indelibly display both.

0 notes

Text

The Sign in Sydney Brustein’s Window

No, “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” is not some amazing rediscovered masterpiece. But yes, Oscar Isaac and Rachel Brosnahan make it worth seeing, especially for its promising but deeply flawed first act.

“The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” was Lorraine Hansberry’s 1964 follow-up to her Broadway debut five years earlier, “A Raisin in the Sun.” She worked from her hospital bed while battling pancreatic cancer, mining rewrites during rehearsals. The play went on to run three months on Broadway and closed two days before Hansberry died at age 34 on Jan. 12, 1965. Revivals have been rare in the intervening years, and this starry one that opened Thursday on Broadway at the James Earl Jones Theater makes it clear why. The production had previously played at the Brooklyn Academy of Music earlier this year.

It’s difficult to imagine more engaging performances than those being given by Isaac and Brosnahan. They portray the young and troubled married couple that lives in Greenwich Village and are repeatedly called “bohemians.” Sidney is a political activist who goes from one failed entrepreneurial gig to another. Iris is a waitress who longs to be an actress. They’re in love, and from the way Isaac and Brosnahan go after each other, it’s evident the sex is great on a scale of Stella and Stanley Kowalski.

When we meet Sidney and Iris, however, there’s more quarreling than lovemaking going on. Sidney is quickest with the insults. Put him in a room with another person, and there’s bound to be a fight. Iris is spared only when other victims wander into their apartment, and they include Sidney’s young ex-Communist friend (Julian De Niro), his conventional uptown sister-in-law (Miriam Silverman), the gay upstairs-neighbor playwright (Glenn Fitzgerald), an avant-garde artist who is designing Sidney’s recently acquired newspaper (Raphael Nash Thompson) and a leftist political candidate (Andy Grotelueschen), whom Sidney somehow finds time to manage.

When Isaac and Brosnahan are onstage alone, “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” delivers the theatrical power of Ruth and Walter Lee Younger’s tragically compromised marriage in “A Raisin in the Sun.” Both couples can’t begin to fulfill the American Dream that’s been jammed into their respective heads.

The first act of “Sidney Brustein’s Window” lasts 90 minutes, and about 45 minutes of it is the production’s most compelling as Isaac and Brosnahan love and slug it out under Anne Kauffman’s direction. There is another 45 minutes, however, when Sidney and Iris interact with the other characters, all of whom should go back to the Herb Gardner comedy from which they came. Most cringe-worthy is Silverman’s conservative sister Mavis, a doppelgänger for the conservative brother Nick Burns in “A Thousand Clowns,” which opened on Broadway two years before Hansberry’s play.

Since Sidney and Iris’ marriage essentially ends at the end of Act 1, there’s no action left to dramatize during the almost-as-long second act. Iris disappears for most of its 80 minutes, and Isaac is reduced to a drunk who listens while the supporting characters are given a moment – a very extended moment – to rant about racism (De Niro), an unfaithful husband (Silverman) and the emptiness of success (Fitzgerald).

A new character (the barely intelligible Gus Birney) enlivens things a bit because she looks and acts like a streetwalker (costumes by Brenda Abbandandolo). Her outfit and hair (by Leah Loukas) don’t lie, and after 15 minutes, this prostitute with a heart of tin has committed suicide in the Brustein bathroom. As records go, it may be the fastest suicide in the history of the theater.

And there’s something else that’s phony about this cliché of a character. How could her fiancé (De Niro) not know that his girlfriend, made up for “RuPaul’s Drag Race,” is not having sex with other men for money? Racism may be the least of this guy’s problems.

Before this tragic episode inspires way too much onstage analysis, the prostitute is invited upstairs by the gay guy so she can watch him and his new boyfriend have sex. Fitzgerald manages to be wonderfully enigmatic in his request, while Isaac acts drunk and Kauffman, for her part as director, distracts us from the absurd theatricality of it all by cleverly bringing Brosnahan, De Niro and Silverman into the audience so they can observe the action in silence. They’re a kind of silent chorus, which relates back to something Mavis has told Sidney about her Greek-American father. Hansberry’s play is chockfull of references to all sorts of mythological characters.

Sidney and Iris reunite at the end so she can tell him what a fool he was to back the wrong political candidate. Why a would-be actress with no political chops knows this and Sidney doesn’t is not explained despite “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” lasting nearly three hours.

0 notes

Photo

One of my favorite theatre companies in the New York area is Hudson Theatre Works. Coming from Connecticut, I don’t always “like” their work but they always manage to challenge the audience and ask them to make up their own minds.

I am happy to report that (they are actually in an old school building in Weehawken, NJ) that their latest is provocative and challenging.

“Shelley”, by Joanne Hoersch, is a radiant take on how the creation of a work of art is a torture, a bliss, a collaboration of memory, experience and courage, that takes us by the hand with its framing character, 78 year old Claire Clairmont, who, in her youth, was part of a ménage à trois with the Romantic poet Percy Shelley and more importantly for this story, his wife and Claire’s stepsister, Mary Shelley. She invites us to “come, share these memories with me.”

We follow them from their high spirited escape from Mary’s overbearing father to what they envision is a liberated France where women have the right, as Percy says, “to choose whom they will marry or even if they will marry.”

What they discover is a far cry from what they expected; France is a desolate land pillaged by years of revolution, The Terror and now the Napoleonic Wars. They meet one man, scarred, mutilated by the wars, one eye bulging from a smashed bone, his arms telling the history of attacks by both the Jacobins and Napoleon’s army. Claire is repulsed by the man’s appearance while Mary is haunted by him.

And so begins Mary’s journey towards creating what will become one of the most influential novels ever written; Frankenstein.

The play cleverly and poignantly inserts the group’s experiences with hallucinatory drugs, an experiment with reanimation (it was believed at this time that applying electrical current to a dead person could bring the person back to life), open marriage, radical politics, as well as a beautifully rendered story of a young duchess who was sent to the guillotine.

Mary’s rich imagination runs in parallel to the harsh realities of her life. Rather than witnessing the electrical spark of life, we witness the spark of creativity, the struggle to find the artist’s voice, as well as the fear but also the excitement of jumping into the void to write something that has never been written before. Claire, the least talented but most life affirming character in the play, tells us in her final monologue that “I read some of my poetry to Percy, and briefly looked up at him. I could tell how ordinary he thought I was and it delighted him “ She freely admits that Percy and Mary’s names will never be lost to history, but hers will. Yet, she stands as the lone survivor, the only one left who knows what the true, not the mythic content of their lives actually was.

Ryan Natalino brings a passionate commitment to the role of Mary, pushing her life forward towards something she knows is there, yet still unreachable. BC Miller as Claire is a delight, sexually brave, light hearted with an impeccable sense of comic timing and an important counterpoint to Mary’s intellectualism. Daniel Melchiorre’s Percy is, despite his radical views, an aristocrat, and Mr. Melchiorre expertly navigates the tightrope between what Percy believes and what Percy is. Todd Hilsee as Mary’s father, William Godwin, lets us feel the weight he carries of having once been famous and relevant and now reduced to poverty and dependency. His disgust with Percy is a thinly veiled jealousy of Percy’s standing in the world, which enhances the enmity between them. And Joanne Guarnnacia, as the older version of Claire, reliably keeps a strong hold on the narrative until her final monologue, which brought me to tears. Frank Licato’s direction, as always, is precise and spare. And, as usual, he always gets wonderful performances from the actors. The set and lighting by Gregory Erbach is evocative, as are the costumes by Ann Lowe and the sound/music by Donald Stark.

0 notes

Text

Leopoldstadt

The great playwright Tom Stoppard and his simpatico director Patrick Marber make a lasting gift of remembrance in the brilliant, gorgeous and devastating new play Leopoldstadt, opening tonight at Broadway’s Longacre Theatre. But it’s a gift that comes with strings, ropes even, the author seems to be warning us: There’s burden attached to memory, and pain, and, above all, responsibility – duty, even – that accompanies every yellowed snapshot in an old family album and every fading face that once seemed fixed with such clarity.

Most of us, thankfully, won’t have the unbearably catastrophic history to carry through life that the youngest of Leopoldstadt‘s characters are ultimately left with. When we reunite with them at the end of the play, in 1955, their numbers dwindled to three, the survivors of Hitler’s campaign to eradicate Europe’s Jews are all that’s left of the once expansive family we’ve come to know in the previous hours.

When we first encounter, in 1899, the extended family of Hermann Merz (David Krumholtz), its members are as grand and sophisticated as the gorgeously appointed Old World drawing room in Vienna. One of those appointments of set designer Richard Hudson’s detail-perfect surroundings is a lovingly decorated Christmas tree – a nod to the Catholics who have married into this otherwise Jewish family and, perhaps more tellingly, to those Jews – Hermann, especially – who believe that the days of separatism are history, that full assimilation of Jews into the Austria they’ve long called home is at hand. Hermann, unlike his more politically astute and analytical brother-in-law Ludwig (Brandon Uranowitz), has no use for radical talk of a Jewish homeland in some godforsaken desert, and places his trust in such social markers as wealth, connections, participation in the high culture and genteel (and gentile) society that so clearly separates, spiritually and otherwise, the world-class city of Vienna from its old Jewish ghetto district of Leopoldstadt.

History has informed the audience that Austria won’t so easily shed its Leopoldstadts, and Hermann’s dreams of assimilation are delusions, that wealth and civic-mindedness and politesse will come to nothing in just a few short decades, when a simple, loud knock at the door will have this beautiful family frozen in terror, the only word capable of expressing what they see outside being a panicked whisper “trouble.”

Stoppard and Leopoldstadt take their time getting to Kristallnacht, though, providing us with many, many snapshots of this family as it grows, develops and lives and dies in the years between Hermann’s doomed optimism and the violence that comes calling in 1938.

An outline of the four scenes that follow the 1899 introduction will be as reductive in personal detail as the family tree that is occasionally projected onto a scrim, but might serve as a helpful throughline:

A year after our introduction to the family, we watch as Stoppard zooms in on one of the personal stories among the family members, in this case a brief infidelity by Gretl (Faye Castelow), the Jewish Hermann’s Catholic wife, with a handsome caddish Austrian officer whose anti-Semitism and cruelty will become all too apparent when he meets Hermann. Gloating, the officer casually crushes Hermann’s naivete, if not his spirit.

Gretl’s tryst will have ramifications in the years to come, though not in ways the characters – or the audience – might predict. When we next see the family, it’s 1924, and the various aunts, uncles, cousins and grandparents – Jews and “papists” both – have gathered for a bris. There have been casualties of the Great War – one grandson is missing, and Jacob (Seth Numrich), the son of Hermann and Gretl, has lost an arm and an eye to battle. As in the previous scene, an outsider brings an ominous mood: The young banker who arrives to meet with Hermann regarding some family business gives voice to the nationalist sentiment that will soon enough change history.

And that history arrives with full force in the next scene: It’s 1938, and the family – children now adults with children of their own, the patriarchs and matriarchs now grown old – is gathered in the once opulent, now spare, apartment (Hudson’s set is a storyteller in itself), trying to make sense of the chaos outside and desperate to plot a course of action. Even now, amidst the sounds of screams and shattering glass – tonight is Kristallnacht – the family is divided as to whether to leave Austria (they still believe they can) or ride out what some of the elders believe to be just the latest in a long line of struggles. A newcomer to the gathering – a British journalist (Numrich, again; many in the cast portray more than one character) who has fallen in love with the young widow of that WWI casualty – warns of horrors unimaginable, horrors that even now seem unthinkable to most, at least until the Nazis to take names, loot possessions and make the decisions that will send each family member on their own particular path to hell.

The results of those decisions are made evident in the final scene, when, in 1955, only three members of the family survive and have gathered in the apartment – how the apartment is returned to the family won’t be spoiled here. Rosa (Jenna Augen), whom we first met as a little girl, is now the family elder, having moved to New York City prior to the Holocaust. Her nephew Nathan (Uranowitz) is the lone family survivor of Auschwitz, and cousin Leo (Arty Froushan), the London-raised son of the war widow and stepson of that British journalist, seems to have no memory of his Viennese childhood, or, for that matter, his Jewish heritage.

Indeed, Leo’s callow disregard for history is, Stoppard could be saying, history itself’s last laugh on the hopeful dreams of assimilation expressed by Hermann a half-century before, the cost of acceptance equal to the steep price of willful ignorance. It will be up to Rosa and Nathan to remind Leo of his past, of history, and of those that paid the price for ability to forget.

Any summary of scenes and timeline descriptions of Leopoldstadt can’t begin to convey the richness of Stoppard’s work, and this play, like his other masterworks Arcadia and The Coast of Utopia, is full of digressions and discussions and dialogue as funny as it is poignant. Mathematics, not surprisingly, comes into play, as it so often does with Stoppard, but so too does Zionism and modern art and so many other aspects of 20th Century political history that Leopoldstadt can at times seem like a right and proper companion piece to Ken Burns’ wonderful The U.S. and The Holocaust documentary.

If Stoppard sacrifices audience connection with any particular character – just as we’re getting to know one generation, a new era arrives – he compensates by etching a family history so sprawling and compelling that we embrace it even as we struggle with the details. (You’ll be mentally tracing this family tree long after the play’s end.) An excellent cast of 38 – 38! – delivers each character with enough individual personality to guide us along the way, even if we’re not always immediately cognizant of how one person might be related to another. Naming specific actors seems churlish with a sprawling cast this good, but nonetheless: In addition to the ones already named in this review, there’s Eden Epstein, Caissie Levy and Aaron Neil turning in remarkable performances, giving life to characters that demand to be remembered.

0 notes

Photo

The Minutes

Time has caught up to The Minutes. When the civic comedy was announced for the 2020 Broadway season, it seemed like a prescient choice, full of up-to-the-moment thoughts about governance. Tracy Letts is the rare playwright whose own celebrity is enough to prompt a Broadway run; ever since the runaway success of August: Osage County, he has had that green-light touch. But then, of course, there were delays.

Between the parentheses of March 2020 and April 2022, actor Armie Hammer left the cast after his reputation combusted; Trump befouled the transfer of power; and the insurrectionists revealed the chaos at the heart of our democracy. Every postponed production has had to account for lost time and changed context, but the gap posed a special challenge for The Minutes: The show deals with a city council meeting, and we’ve spent 700 days watching such conclaves accelerate beyond fractiousness into Kafka-esque terror. Events raced past Letts’s script, with death threats and violence interrupting school-board meetings and public health hearings. Juvenalian satire requires that it be more extreme than reality. Imagine Jonathan Swift having supply-chain issues — only to discover that the English had actually started eating babies before he could publish.

Mr. Peel (Noah Reid), a novice assemblyman in a small town, has missed a closed session of the town council due to his mother’s funeral. He’s a bit of a naïf, thrilled to show pictures of his infant daughter to his colleagues, wandering out of the rain still dazed from grief. “You feel untethered,” says another man, as they gather. “Well, I suppose you are.” Now that Mr. Peel is back in their chamber, the other councilors are being weirdly cagey about whatever happened the previous week, and they refuse to distribute that meeting’s minutes. Plus one of the councilmen is missing. Mr. Peel begs the clerk (Jessie Mueller), Mayor Superba (Letts himself), and the room at large for clarification — but everyone ducks his questions. There’s plenty of new business to distract him: Mr. Blake (K. Todd Freeman) proposes a cage-match attraction to raise money for the town’s festival; Mr. Hanratty (the firework Danny McCarthy) hopes to make the civic fountain accessible; Mr. Oldfield (Austin Pendleton) wants a parking spot. Still, the town’s old business — very, very old business — will not be denied.

Having trouble remembering all those names? No problem, most of them are mnemonics. Mr. Peel is the hero with thin skin; Superba is top man. The dithery, fluttery Ms. Matz (Sally Murphy) is mad; Mr. Oldfield is old; Superba’s sidekick, the contemptuous Mr. Breeding (Cliff Chamberlain), struts and preens like a gorilla in season. And grouchy Mr. Assalone (Jeff Still) is … look, I’m not going to spoil the plot for you.

This determinative nomenclature is a little nod to Dickens and a peep into Letts’s comic methods. Like Dickens, he’s a connoisseur of folly — he rolls human silliness against his palate as if he’s testing it for notes of stone fruit. He therefore finds much to be delighted by in meeting minutiae. The clerk mispronounces Mr. Assalone’s name every time she calls the roll. Mr. Oldfield and Ms. Innes (Blair Brown) squabble in increasingly hilarious ways, and people bicker over points of order and word choice. “Oh, here we go, the language police,” grumbles Mr. Breeding, after saying ten offensive things in a row. “Language police” might describe Letts too: He has fun with infractions.

There’s overwhelming abundance in having a cast that includes so many heavy hitters, all contentedly kibitzing on the bench. There are a lot of Tony Awards on that stage. Reid — already beloved from his role on Schitt’s Creek and new to Broadway — has the wide eyes of a rookie; some of the drifting menace in the room is our vicarious sense of what it feels like to be a young actor with a thousand years of collected theatrical experience arrayed before him. (The laugh-a-minute Pendleton was in the original production of Fiddler on the Roof, but sure, don’t let that intimidate you.) Letts has a rapid pinprick wit, and he inflicts real damage in the play’s early sections. Part of his cleverness lies in this interplay of the actors’ outsize magnificence and his message about small-town city fathers. These fools think they’re Olympians, and who gave them power? Look around.

The Minutes begins as sly frustration comedy. From the moment the lights flicker and the thunder crashes, we can tell Letts is planning to steer this thing into absurdist dread. At first, how he gets there is dramaturgically impressive, full of flashbacks and a bizarre, all-hands-on-deck reenactment of the town’s own history. Letts clearly finds pleasure in the way archives work, from their little notations (Peel’s greatest triumph comes from knowing what NB means when he sees it written on a document) to the way that records render up the past. It’s the opening of one such record that plunges the play from lightness into desperate gravity. The show suddenly becomes clumsy. Letts and director Anna D. Shapiro fumble the first pivot into seriousness, and they do far worse than that in the final turn.

I think Letts has important issues on his mind, so I’m sorry I couldn’t follow him as he goes more fully into them. As he did in August: Osage County, he wants to deal with the state’s foundational sin — the wholesale slaughter of Native Americans. In that play, the house (synecdoche for the country) has a literal Indian in the attic, and the housekeeper character Johnna only reminds and presides. But in The Minutes, Letts isn’t content simply to point at history: He wants to impart its horror. This tonal shift requires a huge stylistic swing, and The Minutes — so fine and deft and wicked for its first 60 minutes — can’t take it. The play shakes and starts to fly to pieces, a Superleggera car taken off-road. I read The Minutes back in the early days of the shutdown, and I remember the moment when I began to think our real absurdities outstripped Letts’s fictional ones. His touch is so perfect and light when he’s doing realism that reality obliged and caught up to him. Knowing what he does now, what play would he write? Would that blunt ending be the same? I won’t believe it. You can’t just leave your satire lying around for two years; you have to measure it down to the minute.

The Minutes is at Studio 54.

0 notes

Text

Cyrano at BAM

Cyrano at BAM May, 2022

Cyrano de Bergerac is having a pop culture moment lately. It’s been 400 years since the real Cyrano lived and more than 100 since Edmond Rostand made his life into an 1897 play, but the skilled writer who, believing himself ugly and therefore unlovable, uses his talents to help another man woo his love was just the subject of a musical film starring Peter Dinklage. Now, British director Jamie Lloyd’s fresh take on Cyrano de Bergerac is making its American premiere at the BAM Harvey Theater, three years after debuting to acclaim in London. It’s different from the lavish period film in every way, and it’s worth the trip to Brooklyn. Lloyd’s Cyrano lives comfortably in anachronism. Classics purists will still find the rhyming-couplet poetry of Rostand’s play intact, but Martin Crimp’s freewheeling adaptation will also delight the Gen-Z crowd: 19th-century verse gives way to 21st-century spoken-word poetry and rap, including plenty of red-hot roasts. Think Hamilton, but faster (yes, it’s possible) and with no accompaniment but a single beatboxer (Vaneeka Dadhria). To that point, Lloyd has stripped Cyrano de Bergerac down to its bare essentials: no props, no period sets or costumes, only a torrent of words. Lloyd’s reasoning? Words are powerful, needing nothing else to make them effective when crafted well. Nothing else besides a deft wordsmith, of course, and here it’s the intoxicating James McAvoy in his New York stage debut. As the lovestruck yet insecure Cyrano, he delivers ferocity, vulnerability, and passion in quick succession, and you’ll want — and need — to hang on every word that Crimp has given him. Ferocity comes first: He introduces himself by leaping downstage and challenging another character to a “swordless” swordfight (no props, remember) at a Hamlet performance. But McAvoy wields a microphone like a weapon and has a sharp enough tongue to rival any blade. (He also unleashes insults at the middling Hamlet actor — Adrian Der Gregorian, a great actor parodically playing the part as a “misunderstood,” artsy bro at a poetry slam. If you know, you know.) But lest that first scene make you think Cyrano is all anger, he divulges his love for the beautiful, intelligent Roxane (Evelyn Miller) to a friend five minutes later. Suddenly, this self-assured showstopper in leather is as flustered and giddy as a schoolboy with a crush. Cyrano can be a tough protagonist to root for, with his self-destructive pride, lofty way of talking, and constant deception, but the versatile McAvoy brings unexpected humility and humor to the character. And you can’t help but be enamored by the balcony scene toward the end of Act 1, the show’s most arresting sequence. Cyrano feeds dialogue to Christian (a sweet Eben Figueiredo) to woo Roxane, but inadvertantly ends up speaking for Christian himself under cover of darkness. With Roxane’s back turned, Cyrano delivers his love confession, a seductive monologue, straight to the audience. No matter how far you’re sitting from the stage, McAvoy makes the moment feel truly intimate, an admirable feat in an 897-seat theatre. Ultimately, the only flaw in McAvoy’s casting is that it’s difficult to imagine him wanting for admirers, especially since he doesn’t wear the honking prosthetic nose that supposedly makes him ugly. (It’s worth mentioning here that Lloyd also gives Cyrano and Christian some serious homoerotic chemistry, creating a true love triangle.) Although McAvoy’s presence commands constant attention at every turn, don’t overlook Miller, who gives a quietly strong performance as Roxane and makes us think twice about our endearment to Cyrano. She especially shines in Act 2 — which discards much of the humor of Act 1 and digs into tragedy — with a speech decrying both Cyrano and Christian for objectifying her beauty and overlooking her intelligence. To both Crimp’s and Miller’s credit, the monologue doesn’t feel preachy, but righteous. Cyrano wields his anger like a battering ram, bowling over everyone in sight, but Roxane wields hers like a dagger, striking pointedly at the heartstrings.

0 notes

Photo

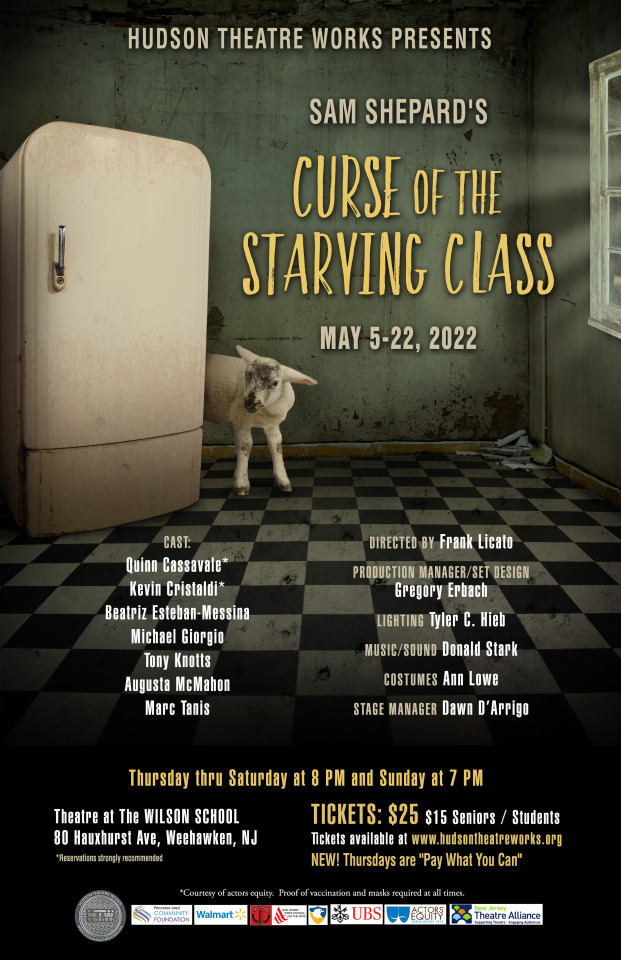

May, 2022

CURSE OF THE STARVING CLASS Presented by Hudson Theatre Works It’s great to be back to live theatre. I haven’t been in a while but when I saw that one of my favorite regional companies was doing Sam Shepard I decided it was time. I have seen some productions of Shepard recently and felt that they failed to capture the initial essence that made Shepard indispensable. The play, written in 1978, is no longer the “comedy” it was or might have been originally. In the 40 something years that has passed the play has taken on a darker tone befitting the world we know now, but it is just as illuminating and in this production wonderfully theatrical.

On the lower East Side of New York in the 1960s, traditional concepts of theatre were being turned upside down by visionary revolutionaries such as Julian Beck, Judith Malina, Richard Schechner, Ellen Stewart, and most importantly for the up and coming Sam Shepard, Joe Chaikin, actor, director and artistic inspiration for The Open Theatre, who became Shepard’s collaborator and lifelong friend.

A true actor, Chaikin believed, could find inspiration in a movement of the body; a gesture, a moment of silence, or a dance. The external reality could ignite an internal response that was not based on the standard approaches of sense memory, or duplication of one’s own empathetic feelings. It was spontaneous, fractured and rhythmic.

Shepard loved music, particularly jazz and rock, (he was briefly the drummer for a folk rock psychedelic band, The Holy Modal Rounders). Cowboy Mouth, one of his earliest plays, was co-written and performed in 1971 with Patti Smith, the avatar of rock ‘n’ roll as sacred incantation. Smith’s character is looking for Jesus with a cowboy mouth, a rock and roll savior. Interpret the text as a trained method actor and it dies on your lips. If the actor has the courage to simply speak with urgency and spontaneity it not only comes alive, it takes you into dangerous zones where you literally don’t where your words are taking you. It is this willingness to trust the text more than your own inner reality that energizes and defines Shepard’s plays.

Shepard’s father left his family to go fight as a bomber pilot in WWII. He was a Rhodes scholar, a successful businessman, a good father. He returned as an abusive alcoholic who could not hold a job. The great silence of the 1950s, the unwillingness of an entire nation to come to terms with what had happened, morphed, as the Vietnam War approached, into a nation that could sit in their brand new homes, with brand new cars and fat bank accounts, and watch villages being torched thousands of miles away, while they ate dinner together as a family.

The rhythms of life had fractured. In a Shepard play, living is always on the edge; volatile, minute to minute, simultaneously both familiar and utterly unknown. In his play Action, which may or may not be taking place in a post apocalyptic world, the main character, Jeep, delivers a fevered monologue at the end. “I have no idea how it got here.I have no idea who did it. I got no references for this.” In Angel City, a story about Shepard’s early forays into Hollywood, he states in his introduction that, ([the] actors transcend character motivation and try to create a ''kind of music or painting in space.'

Hudson Theatre Works’ presentation of “Curse of the Starving Class,” has taken Shepard’s advice and run with it. Under the direction of Frank Licato, who is also the artistic director of the company, we are presented with actors walking a tightrope. “Curse” is considered part of Shepard’s trio, or sometimes quintet, of “family” plays and it is indeed a family that we meet, recognizable by certain touchstones – we are in the kitchen with a mother Ella (Quinn Cassavale) and a daughter, Emma (Augusta McMahon), as well as a son Wesley (Tony Knotts) who is repairing a broken door. But there is also an empty refrigerator. And we are informed by Wesley by means of a beautifully disjointed, fevered monologue, that the door is broken because his father broke it down the previous night in a drunken rage and has now disappeared.

The monologue is immediately crisscrossed by a banal, but perfectly executed speech by Ella exhorting her daughter on the dangers of menstruation and sanitary napkins, which are , in her opinion, actually filthy.

Shepard’s tilted world is beginning to take shape. Or not. The play soars into its own orbit. Weston, the father, played with a fierce commitment to language by Kevin Cristaldi, finally arrives to deliver his laundry so that Ella can wash it, and then launches into a meditation about the beauty of an eagle swooping down to grab a sheep’s castrated testicles in its talons.

We know that this family is in trouble, but who or what is the source of it? There’s a scheming, rabid capitalist lawyer, and a slimy land speculator, who threaten from the outside, but there is rot from within as well.

Licato has gotten the talented cast all onto the same page. They feel the rhythms of Shepard’s language, they dare to jump from word to word, sentence to sentence without a net. Life is only what comes right after the word you just uttered. Shepard the playwright arrived at a time when drama, structured as a cradle to grave trajectory that in the end gave us a sense of ourselves and a meaning, however tragic, to our lives, was gone.

All the actors, including Augusta McMahon as Emma, the daughter, and TC Tanis, Michael Giorgio and Beatriz Esteban-Messina are all terrific

Shepard does not give comfort or even provide a roadmap. He puts poetry in the mouths of villains, profanity into the mouths of the innocent. I am reminded of an interview I heard years ago with Patti Smith, where she extolled the beauty of Jim Morrison’s grave in Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, because it was littered with cigarette butts and honored with garbage. Or maybe she didn’t say that.

Licato understands Shepard, how to get under and around the language, and he has ignited his cast with the courage to approach it unconventionally. A worthy challenge that is well met.

0 notes

Photo

February 19, 2020

I have taken this blog on as a way of getting the word out about theaters in the tri-state that many don’t know about. In an age when most of the major papers have discontinued their coverage of smaller theaters or ANY theaters outside of Manhattan I am going to try to cover places that I feel should have attention paid to them. The particular work may or may not be my taste (and I will certainly let you know that) but the theater should be covered.

Seven Angels in, CT is a theater that I have been to and have appreciated over the years for their commitment to new plays. Their current play is called, ‘Love and Spumoni.

Love and Spumoni” is based on the story “Listen to Your Heart” by Mary Lou Piland, which went viral after she presented it as a 12-minute story on “The Moth Radio Hour” in October 2015.

Italian Piland (Marissa Follow Perry) falls in love with African American Anthony, played by Dante Jeanfelix. Due to her devoutly Catholic family, she can’t tell them of her feelings for someone not Catholic or Italian, much less African-American.

Coupled with her crippling social anxiety, which makes her incapable of holding a conversation with Anthony, creates a situation that is ripe for both comedy and drama.

The problem is that the beginning of the play spends too much time from the perspective of an adult Mary Lou (Maria Baratta) who narrates how she came to be telling her story and setting up the story instead of just telling it.

The narrator role, interjecting almost constantly throughout, further compounds the issues. She also plays every character outside of her younger self and Anthony, including her father, mother, grandmother, sister, and best friend. The play could have easily been more compelling, with a more diverse array of character dynamics, if different actors presented all the characters.

This would also rid the play of the narrative issue, let the characters tell the story, and give the story a smoother narrative.

Will the families destroy the tender shoots of love in bloom? Will Mary Lou find herself exiled and forced to abandon her home? Can Anthony’s mother accept her and welcome her into her new role?

The actors and director do a good job but the play needs more work.

“Love and Spumoni” has an important romantic story to tell and there is a foundation of a fun1980s romcom hidden within. It just needs to trust the characters and drop the narrator.

Love and Spumoni

Theater: Seven Angels Theatre

0 notes

Photo

February 18, 2020

Open Box Arts

Large news organizations in New York rarely send their arts critics across the Hudson River to check out what’s going on in New Jersey and other satellite states of the Monolith. But there is gold to be mined in smaller, less well funded places that perform magic on low budgets. That’s what I’m here for and one of those places is Hudson Theatre Works, a small, passionate, tenacious theatre company located in Weehawken, New Jersey, just a stone’s throw (or a ten minute bus ride) from mid-town Manhattan.

This is the first time I’ve seen their work but I have been hearing about their adventurous theatrical choices for some time now. I’m sorry it’s taken me this long to get there. Their current offering is Hamlet. In Frank Licato’s pared down, superlative and cleverly edited version, this gutsy interpretation of the Shakespearean classic, resonates to create a tense direct account of the text. At two and a half hours the play moves with surgical precision. A cast of 10 perform the play with passion and commitment. Bess Miller, as Hamlet, opens the play, alone on stage, and launches into, “Oh that this too, too solid flesh would melt,” soliloquy. Not what we are used to, but its placement tells us immediately what we are to expect from this production. The audience settles in, we know that we can trust this actor with the text. The setting is minimal; a few large boxes covered in elegant cloth, a large screen, martial drumbeats. With music and projections by Donald Stark and Harrison Stengle and moody lighting by Josh Hemmo.

Then we’re off. From Hamlet to the ghost of Hamlet, from flesh to spirit, life to death, and the incomprehensible stuff of life that winds its way through this lovely, straight forward text, presented in this infinitely comprehensible production.

The acting is top notch. Ryan Natalino as Ophelia is a courageous and more womanly character than the Ophelias I’ve seen before, yet she is in love, and allows her vulnerability to Hamlet seep into her performance like a tinted darkness that brings her to the brink of being a tragic heroine; Mike Folie as the blowhard “yes man” Polonius , is pitch perfect with his comic timing, yet he imparts his character with a poignancy and love for his children that makes his death truly shocking.

Michael Gardener, playing Horatio, is bound to Hamlet by both loyalty and love. As Hamlet lays dying in his arms, the full weight of Mr. Gardener’s performance takes hold. Horatio is often relegated to a minor presence, a sounding board for Hamlet, but here we have a fully embodied character who brings history and loyalty forward and it adds a particular gravitas to the end of the play. Scott Cagney almost steals the show as the Player King and Nolan Corder, Amanda Yachechak, Sara Parcesepe and Louise Heller and Charles Wagner round out this talented cast as Gertrude and Claudius.

As Hamlet, Bess Miller wrestles with all of the doubt, desire and determination to avenge his father’s death. But we hear it, and we see it. When I compare Ms. Miller’s performance to the infinite number of Hamlet’s I’ve born witness to, she is the one who opened the doors to the language for me most clearly. She is an actress we root for, and though Hamlet is a prince, he is as buffeted by life as any one of us. When she says, “Now, I am alone,” she actually is alone on stage as well as alone within the play. We are drawn in, we sense the duality, always the duality.

The play’s the thing, and in this nutshell of a theatre, we are all kings of infinite space, because this production has brought us through this infinitely fascinating play, with infinite generosity. Go see it.

The play runs thru March 1st and tickets are available at www.brownpapertickets.com.

#shakespeare#hamlet theatre newjersey weehawken

2 notes

·

View notes