My name is Bex! She/Her. I'm a self-employed plush maker and designer of scientifically accurate soft toy extinct creatures and obscure critters. I also try my hand at digital painting, sculpting and other arty things. On top of my own creations, I share lots of content related to whatever my interests are at the moment, as well as photos of my pet rats and my aquarium. Click here for my online shop!

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

South American armored sucker mouth catfish

Illustrations by Sam Scalz

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

from silk reeling to fine suzhou embroidery by 许潇潇

16K notes

·

View notes

Text

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

Fresh summer spinos are looking for homes!

these big guys are beach themed, mimicing the golden warm sand and cool turqouise waves

----

barks-bog.com

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

Race: Understanding Human Diversity - Part 1

A small sample of our species (Eric Haynes, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The following is adapted from the extensive notes for what would have been Episode 4 of my Through Time and Clades lecture series "Humanity, a Prologue - Season 2". I still find the material I intended to cover very important and felt it would make for a good series of blog posts.

This first post will outline a brief history of the study of race and human diversity in anthropology, and then ask whether Homo sapiens can be scientifically classified in such a way. I intend the second post to outline how human diversity is understood today, and the third post will trace the evolution of human diversity through time, primarily through genetics and aDNA.

What is Race?

A race is social classification unit of humans based on physical characteristics that are considered significant as distinguishing traits. Put another way, "race is a worldview and social classification that divides humans into groups based on their appearance and assumed ancestry, and that has been used to establish social hierarchies" (Graves & Goodman, 2022). Therefore, the idea of human races is tied with the history of human social relations, as we shall soon see below.

However, the word race has become confused in the public perception of anthropology. There are assumptions of synonymy between terms like "race", "ancestry", "ethnicity", etc, but it must be stressed that each of these terms have distinct meanings.

For the benefit of readers, let's go over some of these other terms, as they will be used again throughout this series of articles.

Ethnicity - and ethnic groups - are explicitly cultural definitions. Belonging to a specific ethnicity means identifying with a group of people who share specific norms, mores, customs, values, traditions, beliefs, and habits (Kottak, 2008). Ethnic groups can be in essence religiously-based, or linguistically-based, or tied to a specific country or region, and are considered by others and themselves as belonging to the same culture and having the same history. Sometimes, but not exclusively, they can be based on race.

Ancestry is somewhat trickier to define. We think of our ancestors as the people who came before us (and a few folks may even suspect that all of their ancestors belong to a particular race) and it is a fact that the further back you go eventually you will reach the last common ancestral population of our species Homo sapiens. However, the essence of ancestry is complex and multifaceted.

Take, for example, the thought-experiment outlined by Steve Olson in his 2002 book Mapping Human History: think about your biological parents, now think about their parents. That gives you four grandparents. Now think about their parents. And keep going. You are essentially doubling your ancestral pool as you go back down the generations. Mathematically, you will eventually reach a point where the total number of ancestors alive at any given time will far exceed the known global human population (for example: if you take a generation to mean 20 years, then 30 generations ago you should have over a billion ancestors... but estimates of the human population in 1400 don't reach much beyond 375 million people!).

That means, according to statistician Joseph Chang, that when you reach a certain point (by his calculations just 800 years ago) there are two possibilities: any given person alive at the time is either your ancestor and everyone else's ancestor, or they have left no living descendants (Chang, 1999). Subsequent work has elaborated and tweaked this model - the common-ancestral age estimate has been placed somewhere 3,600 years ago - but the core findings hold true: "we see families as discrete units in our lifetimes, which they are. But they're fluid and continuous over longer periods beyond our view, and our family trees sprawl in all directions" (Rutherford, 2017). Given what we know of world history from beyond the modern colonial era, people got around fairly easily and were certainly not overwhelmingly limited by geography.

For the purposes of genetics research, scientists have used the term "ancestry" to mean different things in regards to the sample size or the period of time being studied. For the purposes of these articles, I will be discussing genetic ancestry as referring to the recovered DNA signature in descent groups that are inherited from older related or ancestral populations.

That brings us now to more technical terminology that you might come across in scientific literature. According to Philip W. Hedrick, populations are defined in terms of mating propensity, while demes are a group of interbreeding individuals that exist together in time and space, from whom mates would normally be chosen (Hedrick, 2011). These then are historical terms with no absolute boundaries: much like the rest of life, human populations and demes change over time and acquire new characteristics. This is especially true in the case of admixture or introgression, terms designating when two or more temporal populations intermix genetically, which is all the more clear in our aforementioned discussion of ancestry. As a rule, the larger the sampled population, the more frequent will be the record of admixture.

Thus, we need to be precise when using such terminology. Populations and ethnicities are not races, and race is not the same as ancestry. For a more rigorous explanation of these distinctions, statistical geneticist Sasha Gusev has written on the subject here.

A Brief History of Racial Anthropology

So where did our understanding of race and human diversity come from? People have no doubt recognized differences and similarities amongst each other since the earliest times, but so far as the evidence tells us, ancient peoples put significantly less emphasis on race as a biological concept than modern peoples have done. The Greek philosophers Aristotle & Hippocrates II spoke at length about environmental determinism and believed that climate and latitude could produce "better" or "lesser" peoples (Quinn, 2024). Other Greeks, and later Roman authors (including Christians), would embrace these ideas and use them to justify slave practices and colorism (Kendi, 2016). However, the construction of biological races as immutable categories was not in the minds of the ancients, despite an awareness of human physical variation (Graves & Goodman, 2022). They were more concerned with cultural differences and superiority, and a person - regardless of their country of origin - could assimilate and "make themselves" into, say, a Greek or Roman (Sussman, 2014).

The first inklings of biological-racialism began to show towards the end of the post-classical or medieval world. The horrifying practices of the Spanish Inquisition were at once racist and antisemitic in that they singled-out specific groups (primarily the Jewish people but also Romani & Christianized Muslims) and sought to remove them from society (Sussman, 2014). Far from being simply a religious conflict, the Inquisition specifically classified people based on "impurity of blood" and forbid the assimilation of groups that had been the norm since classical times. This mentality transferred with the Iberian colonists as they reached the Western Hemisphere and encountered Amerindian peoples, as well as during their earlier expeditions along the western African coasts.

It is particularly telling that the origin of racist ideas should have commenced during the trans-Atlantic colonial era. In previous times, explorers in Eurasia and North Africa tended to travel on foot or over caravans. As we will see, human variation is clinal with no prominent breaks in sequence: a person traveling from western Europe to China would meet people who each time would look gradually different but still retain mostly similar features. Now consider a Spanish or British sailor traveling to Central America or southern Africa: their frame of reference would now be disparate and opposite ends of a spectrum, the differences in physical features on people being necessarily enhanced by having missed the clinal variation between them (Graves & Goodman, 2022).

In any case, such differences made racist thoughts, laws, and practices all the more easier to justify, and it wasn't long until cultural and physical descriptions merged into racist categories: one of the first was the French scholar François Bernier in 1684 whose "new division of the earth" recognized 4-5 races of people and argued that white Europeans were the original blueprint of humanity. Carl Linnaeus - the founder of our modern biological classification - elaborated this scheme with his own 5-race system in 1758. He agreed with the elevation of Europeans and specifically defined the races in terms of both physical traits and cultural norms which to him were treated objectively but are so very clearly prejudiced and ignorant upon basic reading (Kendi, 2016). Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a contemporary of Linnaeus, devised a rival 5-race system in 1795 and was the first to coin the term "Caucasian" to refer to Europeans and related peoples in southern Asia. At the same time, the bodies of disenfranchised and Indigenous peoples were being studied and dissected to support these schemes. This practice was carried on well into the 1800s. The American doctor Samuel George Morton had amassed an enormous collection of human skulls for the purposes of measurement and comparison, beginning in 1839. He concluded that the skulls of Caucasians had the highest cranial capacity and thus were the most intelligent of humans. It is interesting to consider that, while paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould had reviewed and criticized Morton's work in 1981 to much surprising controversy, in Morton's own time a German scholar Friedrich Tiedemann performed much the same experiment and could not replicate the results, subsequently seeking to challenge Morton's findings in the name of antiracism (Kendi, 2016).

From the earliest colonial times to the peak of pre-Darwinian evolutionary thought, there was an on-going discourse among Europeans about whether the human races descended from different ancestors (the polygenesis model) or whether all humans descend from one ancestor (the monogenesis model). Such arguments played key roles in the justification of slavery and other racist practices among the European nations at home and abroad. After Charles Darwin outlined natural selection in print in 1859, he eventually penned his research on human origins in another book The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex by 1871. Darwin's analysis was at once enlightened and prejudiced: he agreed with the monogenesis model and pointed out problems in racial classification from earlier authors, but he argued that the races were ancient, suspected that they came about due to sexual selection, and that each had differing levels of cognition. He agreed with his contemporaries that European peoples were the most civilized and lightly implied that the subjugation and genocide of "primitive" "savages" was an outcome of natural selection (DeSilva et al. 2021). From almost immediately this moment on, the study of human races gained an evolutionary veneer, and many scholars who misunderstood the principles of natural selection used its language to justify human hierarchies.

In one direction, this developed into a persistent and sinister ideology. In 1855, French royalist diplomat Arthur de Gobineau published An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races in which he argued over four volumes that the physical and mental characters of different human races had remained consistent from the beginning and would remain so into the future. Among the Caucasians, Gobineau highlighted the "Aryans" (a term for the proto-Indo-European-speaking groups which lived across Central Asia) were the most advanced and responsible for everything good and civilized in the world (Kendi, 2016). Several authors took Gobineau's work and expanded upon it, including economist William Z. Ripley, whose 1899 book The Races of Europe was treated as an authoritative work in racial anthropological circles (Sussman, 2014). In the end, a direct line of descent can be traced from Gobineau & his peers to the foundations of both the American eugenics movement and the ideology of Nazism.

Long before the early 1900s, when modern anthropology came of age, there had always been antiracist critiques of the mainstream academics and scholars who purported their ideas about race. From John Woolman to Frederick Douglass, it would be unfair to say that the study of human diversity was always upheld by bigots. It would also be unfair to downplay the role of racism and its prevalence in all forms across the history of anthropology.

The work of Franz Boas and his students did much to shape the course of the field. As members of the American School of Cultural Anthropology, they approached the study of humanity from a holistic and non-essentialist approach, rejecting ideas of evolutionary hierarchy and white supremacy (Erickson & Murphy, 2008). Though not always free from cultural biases, Boas himself studied American immigrants of many backgrounds and found that some traits (like skull shape) said more about health and environment than "racial purity". Critically, in a 1894 paper , Boas said the following: "Historical events appear to have been much more potent in leading races to civilization than faculty, and it follows that achievements of races do not warrant us to assume that one race is more highly gifted than the other" (Sussman, 2014). Further work by Robert Lowie, Alfred Kroeber, & Margaret Mead did much to dismantle the scientific paradigm that a person's race determined their culture or psychology.

There were still attempts to classify human races, however, with the most notable and widely-cited attempt by Carleton S. Coon in his 1962 The Origins of Races. This work adapted an earlier scientific racial nomenclature for much of the later 20th Century, describing "Caucasoids" & "Mongoloids", for example. Such terms, frustratingly, remain in use in some circles to this day. Coon utilized older arguments from early paleoanthropology to argue that human races developed from deep in the past, from various populations of Homo erectus rather than from a single Homo sapiens ancestor. In many ways, Coon was challenging a growing consensus among younger anthropologists that "biological race" as a concept should be abandoned in regards to humans. One of Boas' students, Ashley Montagu, had written extensively on human evolution from the view of the growing modern synthesis since the 1940s, and he played a key role in outlining the UNESCO statements on race in the 1960s (Sussman, 2014). And the work of Sherwood Washburn - notably a 1951 paper - pushed for a complete overhaul of physical anthropology and a rejection of the idea of racial classification.

By the end of the 20th Century, racial anthropology had undergone a significant metamorphosis. The increasing study of human cultural and physical diversity, the advent of genetic studies, and the processing power of computer modeling had through the world's largest wrench into the study of "race". There was also a greater awareness of the societal damage done by racial anthropology and the need to seriously study the phenomena earlier scholars under modern scientific advances: "conformity to political correctness was not the cause of these changes; rather awareness of the uses of race in colonialism, slavery, segregation, and in the holocaust stimulated re-examination of the race concept using the new genetic data that was accumulated throughout the 20th century" (Leiberman, et al. 2003).

Today, many researchers have brought to light a proper understanding of human diversity in a modern evolutionary context. And their tools and data sets are even greater than at the turn of the century: we can now peer into the human genome and sequence DNA and proteins that are thousands to millions of years old. Much of this new and current research will be explored in these articles.

How Are Subspecies Recognized?

So why are humans so diverse? We're mammals right? And we recognize that many mammalian species can be divided into subspecies, so why not us? And if we can be, wouldn't these subspecies be considered races?

If the question of "what is a species" is controversial in biology and paleontology, then the question of "what is a subspecies" is probably more-so. Since the early days of Linnaean taxonomy, naturalists have flooded the literature with trinomial names, often using little justification beyond differences in, say, fur color or relative size. In 1942, biologist Ernst Mayr defined a subspecies (which he synonymized with "geographic race") as "a geographically localized subdivision of the species, which differs genetically and taxonomically from other subdivisions of the species". Other later authors have provided mathematical rules based on genetics; for example, Susan Haig & colleagues wrote that "the only quantitative subspecies definition we found was the 75% rule that states a subspecies is valid if 75% or more of a population is separable from all (or >99% of ) members of the overlapping population" (Haig, et al. 2006).

In their 2019 book concerning wolf conservation, Joseph Travis and colleagues provide more multifaceted criteria. They argued for combining a wealth of 1) morphological and fossil evidence, 2) genetic evidence, and 3) ecological and behavioral evidence to support a proper and valid taxonomic division of a subspecies, with "the general view being that subspecies are groups of actually or potentially interbreeding populations that are phylogenetically distinguishable from, but reproductively compatible with, other such groups" (Travis, et al. 2019).

One could argue that all this talk of subspecies is moot. Stephen Jay Gould argued in his essay "Why We Should Not Name Human Races - a Biological View" that the use of subspecies as a classifier inhibits and oversimplifies our understanding of regional evolution. Using case studies from island land snails and house sparrows, he decried "shall our approach to such variation be that of a cataloger? Shall we artificially partition such a dynamic and continuous pattern into distinct units with formal names? Would it not be better to map this variability objectively without imposing upon it the subjective criteria for formal subdivision that any taxonomist must use in naming subspecies?" (Gould, 1977).

Regardless, there is at least a set of guidelines that can be followed to determine whether humans can be classified as subspecies. Such processes have already been used to mold a proper understanding of living mammalian diversity, and this research is perpetually changing. For example, it was once proposed that tigers (Panthera tigris) constituted about nine subspecies, but arguments have been made to condense this number to just two. In 2023 alone, one paper favored the two-subspecies proposal while another favored the old nine-subspecies model (Wang, et al. 2023; Sun, et al. 2023). Giraffes have gone through a similar back-and-forth, between proposals that the giraffe is one species with nine subspecies and that the giraffe represents multiple species: the most recent analysis favors four species, each with a few subspecies (Kargopoulos, et al. 2024).

Far from being exempt, much research has been done on the question of human genetic diversity and whether this matches what we in other large mammals.

How Does Human Diversity Quantify?

Morphological and fossil evidence had been used in the past to classify humans into subspecies and races, but recent work on a more complete hominin fossil record shows without question that all Homo sapiens remains share more in common with each other than with other human species like Neanderthals or Homo erectus. There are characteristic features like our globular skull, prominent chins, and gracile rib-cage and pelvis which clearly define our species whenever remains have been found on every continent. There is regional variation in space but also time, and these changes to skeletal morphology have been shown as having more to do with environment, culture, and sheer chance than with relatedness to a specific racial type. Paleolithic humans have historically been difficult to classify with modern "racial groups", and there has never been enough time and distance to keep any one population isolated for so long as to develop distinct traits. We're really good at moving around and mating.

The difficulties in objectively studying differences based on morphology have let researchers to turn to genetics. One of the most famous studies was conducted by Richard Lewontin in 1972. He sampled populations from around the world and quantified the genetic diversity within and between proposed racial and ethnic groups. Here's Lewontin in his own words:

"The results are quite remarkable. The mean population of the total species diversity that is contained within populations is 85.4%, with a maximum of 99.7% for the Xm gene, and a minimum of 63.6% for Duffy. Less than 15% of all human genetic diversity is accounted for by differences between human groups! Moreover, the difference between populations within a race accounts for an additional 8.3%, so that only 6.3% is accounted for by racial classification" (Lewontin, 1972).

Lewontin's work was widely shared and referenced in the years since its publication, but there have also been subsequent studies that have essentially validated its primary findings: that there are more genetic differences between human groups within proposed races than between proposed races, and that human genetic diversity as a whole is pretty small. Just some examples: Barbujani, et al. 1997 reported 84.5% of genetic diversity found within populations, 5% is found between populations within a “race”, 8-11.7% between “races”; Rosenberg, et al. 2002 reported 3-95% of genetic diversity found within populations, 2.4% is found between populations within a “race”, 3.6% between “races”; and Li, et al. 2008 found 89.9% of genetic diversity within populations, 2.1% is found between populations within a “race”, 9% between “races”.

Furthermore, work has failed to find evidence of specific genetic variants which are "private to geographic regions (excluding individuals with likely recent admixture from other regions)" (Bergström, et al. 2020). It is quite apparent that Homo sapiens had a very recent ancestry and descended from a fairly small gene pool which has expressed itself in the remarkably similar genetic blueprint between all of us: "63% of variants common in at least one region are also globally widespread, in the sense of being found across all five regions. This number rises to 82% for variants common in at least one region outside of Africa." (Biddanda, et al. 2020).

How human genetic diversity compares to other large mammals (Templeton, 1998)

When all of this is compared to other large mammals, the genetic variation shrinks even more. A 1998 paper by Alan R. Templeton used a fixation index on a sample of mammal species to see where they stood on a spectrum between equally-shared genetic diversity within but not between populations and fixed genetic diversity between but not within populations. The results showed that global human genetic diversity was lesser than, say, the population of impalas in Kenya or all the populations of wolves across the Northern Hemisphere. Even among our fellow great apes, we find that the total diversity of humans is dwarfed by that found in regional populations of gorillas or chimpanzees (Gagneux, et al. 1999). Again, such results corroborate the findings of Lewontin and his successors.

How human genetic diversity compares to other great apes (Gagneux, et al. 1999)

Lastly, using ecology or behavior to classify humans into subspecies just does not work, because adaptive traits can vary widely between human groups, even within the same environments, and are also often determined by cultural or historical factors. So if you wanted to classify humans in this way, you would find that different "races" have adapted to the challenges of different climatic or environmental conditions inconsistently. Sometimes cultural solutions would overlap, but never always. Biological human ancestry does not parallel with behavioral ecology in the same way it does with other organisms.

In Essence...

Taken together, morphological, genetic, and ecological data have repeatedly shown that, statistically, these are not great enough to warrant classification into subspecies, let alone races. At no time has a human group been isolated geographically for so long that it is morphologically and genetically distinct from the rest of the world population. Human diversity is best understood as clinal, showing continuity between groups with little in the way of significant geographic barriers that are not broken somewhere in the world. Noah Rosenberg's aforementioned 2002 study utilized a software called STRUCTURE which placed genetic similarities into clusters which could then be divided into any given number the researcher provides. In this particular study, the majority of the clusters centered on five geographic groups that one could say support a division of humanity into five races, but (as Adam Rutherford eloquently explained in his 2017 book A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived) this would be succumbing to the sort of past subjectivity that painted racial anthropology: "look for clusters, and you'll find clusters". Rather than plugging these results into preexisting racial classification systems, wouldn't it be better to ask new questions? "Why do we see these groupings, especially if the rest of the genome, in fact the majority of the genome, does not show such regional variation?"

STRUCTURE clusters found across global human samples (Rosenberg, et al. 2002)

It must be stressed, then, that biological anthropologists today do recognize that there is clear regional variation between human groups. While we are all so similar genetically, we are not clones. The study of this diversity has opened up exciting avenues of research which have revealed key insights into the last 300,000 years of human evolution. But it is also with a strong and firm hand that it must also be stressed that race is an inaccurate, unhelpful, and meaningless way to understand all this diversity. In much the same way that most paleontologists and evolutionary biologists have done away with the essentialist Linnaean schemes that have plagued animal classification, so to have proper anthropologists abandoned "race science". As we've clearly seen at the start of this post, race science was clearly born of racism, and this is a fact that must always be emphasized whenever someone tries to argue about "race realism" or "human biodiversity": nearly of the time, arguments about the validity of race as a biological concept have racist roots, no matter how deep.

Representations of clinal human variation. A showcases a simple cline and the effect selective sampling can do in suggesting distinct genetic clusters; B shows global genetic diversity represented by continental-scale gradients (Maglo, et al. 2016)

For all this diversity, human beings are still importantly similar, moreso than many other large mammals. So much so that we can be considered a monotypic species: biologically we are Homo sapiens and that's as specific as we can get. Human subgroups do not fall under the criteria used to classify subspecies of mammals, nor any other category like breed (see Norton, et al. 2019). Though human physical & genetic diversity is real, racial classification does not reflect this; nor can a cladogram fully represent the evolution of human diversity over time, so full of admixture as it is. Our genetic past is a tangled knotted bush, not a neat pedigree-tree. Human genetic variation is statistically greater within populations than between populations, even when factoring in geographic clustering. All humans, everywhere, are closely related members of the same species.

In the next post, I'm going to specifically address the latest research into human diversity. What does the science say about our range of skin colors, hair shapes, skull dimensions, dentition, blood type, and other features of our anatomy? What about disease? Or IQ and intelligence? Some of the answers may surprise you.

Book References

Jeremy DeSilva, et al. A Most Interesting Problem: What Darwin's Descent of Man Got Right and Wrong about Human Evolution (Princeton University Press, 2021)

Paul A. Erickson & Liam D. Murphy. A History of Anthropological Theory (University of Toronto Press, 2008)

Alan H. Goodman & Joseph L. Graves Jr. Racism, Not Race: Answers to Frequently Asked Questions (Columbia University Press, 2022)

Stephen Jay Gould. The Mismeasure of Man - 2nd Edition (W, W, Norton & Company, 1996)

Stephen Jay Gould. Ever Since Darwin: Reflections in Natural History (W. W. Norton & Company, 1977)

Philip W. Hedrick. Genetics of Populations - 4th Edition (Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2011)

Ibram X. Kendi. Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (Bold Type Books, 2016)

Conrad Phillip Kottak. Cultural Anthropology - 12th Edition (McGraw Hill, 2008)

Ernst Mayr. Systematics and the Origin of Species (Columbia University Press, 1942)

Steve Olson. Mapping Human History (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002)

Jonathan Pritchard. An Owner's Guide to the Human Genome (Standford University, 2024 & ongoing)

Josephine Quinn. How the World Made the West (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2024)

Adam Rutherford. A Brief History of Everyone Who Ever Lived (The Experiment, 2017)

Robert W. Sussman. The Myth of Race (Harvard University Press, 2014)

Joseph Travis, et al. Evaluating the Taxonomic Status of the Mexican Gray Wolf and the Red Wolf (National Academies Press, 2019)

Paper & Article Citations

Guido Barbujani, et al. 1997. An apportionment of human DNA diversity (PNAS)

Anders Bergström, et al. 2020. Insights into human genetic variation and population history from 929 diverse genomes (Science)

Arjun Biddanda, et al. 2020. A variant-centric perspective on geographic patterns of human allele frequency variation (Elife)

Joseph T. Chang, 1999. Recent common ancestors of all present-day individuals (Advances in Applied Probability)

Pascal Gagneux, et al. 1999. Mitochondrial sequences show diverse evolutionary histories of African hominoids (PNAS)

Sasha Gusev, 2024. A molecular genetics perspective on the heritability of human behavior and group differences (Gusev Lab)

Susan Haig, et al. 2006. Taxonomic Considerations in Listing Subspecies Under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (Conservation Biology)

Nikolaos Kargopoulos, et al. 2024. Heads up–Four Giraffa species have distinct cranial morphology (PLoS One)

Richard Lewontin, 1972. The Apportionment of Human Diversity (Evolutionary Biology)

Jun Z Li, et al. 2008. Worldwide human relationships inferred from genome-wide patterns of variation (Science)

Leonard Lieberman, et al. 2003. The Decline of Race in American Physical Anthropology (Anthropological Review)

Koffi N Maglo, et al. 2016. Population Genomics and the Statistical Values of Race: An Interdisciplinary Perspective on the Biological Classification of Human Populations and Implications for Clinical Genetic Epidemiological Research (Fronteirs in Genetics)

Heather L. Norton, et al. 2019. Human races are not like dog breeds: refuting a racist analogy (Evolution: Education and Outreach)

Noah A. Rosenberg, et al. 2002. Genetic structure of human populations (Science)

Xin Sun, et al. 2023. Ancient DNA reveals genetic admixture in China during tiger evolution (Nature Ecology and Evolution)

Alan R Templeton, 2013. Biological races in humans (Stud Hist Philos Biol Biomed Sci)

Alan R. Templeton, 1998. Human Races: A Genetic and Evolutionary Perspective (American Anthropologist)

Chen Wang, et al. 2023. Population genomic analysis provides evidence of the past success and future potential of South China tiger captive conservation (BMC Biol)

Sherwood Washburn, 1951. The New Physical Anthropology (Section of Anthropology: Transactions of the New York Academy of Sciences)

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello everyone! I will be tabling at DINOCON this August 16th-17th at the University of Exeter in England!!

My tablemate will be the amazing, illustrious plushie creator @thylacines-toybox! Come over and check out our stuff, and maybe snag some books and merch minus shipping costs from the USA, lol! I've never done an international convention before and if it goes well I hope to return!

I will also be painting up a bunch of watercolor originals of prehistoric creatures to sell! Comment with your favorite dead beast, bug, or plant and I will add it to my list of considerations! The weirder and more obscure, the better :^)

492 notes

·

View notes

Text

Big shop update!!!!

new spinos

hognose restock + new snow morph

many gouramis!!

----

barks-bog.com

584 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other day I just felt like bringing every single thylacine plushie I have out onto the lawn. Group photo time!

Compared to last April's photo, there are... 19 new plush thylacines, bringing the total to 63!! (if we include puppets, mitts, hidden joeys, and all Jellybeans). That includes 5 that I made or modded from other plushies.

My shelves were due a big rearranging anyway, so I'll probably post another collection update once that's done, because there's a lot of great new non-plush thylacines in there too!

The names! (I am actually starting to have a hard time remembering the genders I originally gave a few of these lol, but the names are all still crystal clear to me. A few of them can get transed, that's okay.)

And all their brands/makers...

And here is the less organised heap, plus Ellis who enjoyed loafing on the blanket I used to carry them all outside.

Oops, between taking these pics and posting them, I may have actually sewn a secret 64th thylacine.

516 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I reworked my lifesize Thylacine pattern, and here's the results of my first test. I'm so pleased I don't think I need to change hardly a thing!

This plushie Thylacine is available over on my website; https://www.palaeoplushies.com/shop/thylacinus-cynocephalus-lifesize-11-1

816 notes

·

View notes

Text

10000 YEAR OLD ROCK ART OF GIRAFFES FOUND IN LIBYA LET'S GO

61K notes

·

View notes

Text

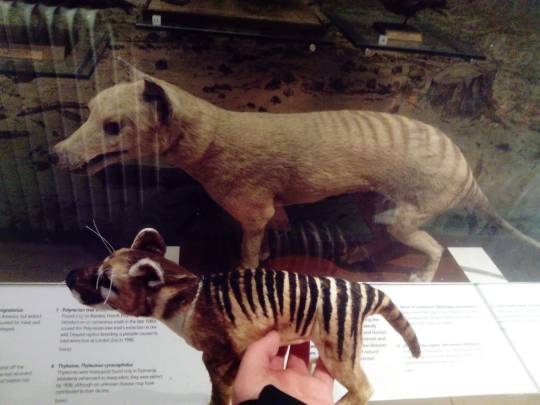

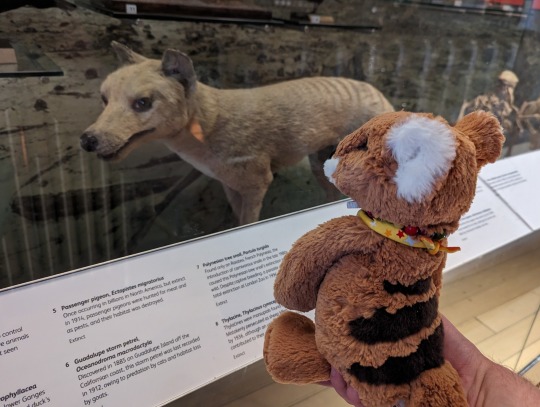

When I visit the National Museum of Scotland I usually like to pay a wee visit to the thylacine there, and I often have a thylacine of my own with me when I do... so I have collected quite a few photos like this over the years, hehe. First photo here is from 2017.

640 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rats on the lawn gifset

367 notes

·

View notes

Text

An unusual Thylacine colour morph... This Bicolour thylacine displays both melanism and white patches (piebaldism). A speculative colouration that may have occured if thylacines were domesticated rather than driven to extinction. This piebald thylacine is available over on my website; https://www.palaeoplushies.com/shop/thylacine1-2

#palaeoplushies#speculative evolution#speculative biology#speculative zoology#spec bio#plushie#thylacine

184 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bicoloured Thylacine!

This was inspired by naturally occurring piebald quolls and Tasmanian devils as well as domesticated sugar gliders showing bicolour/piebald patterning.

Maybe in an alternative universe, thylacines were domesticated rather than driven to extinction?

232 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yamaguchi Kayo - "Cormorants,"

woodblock print, 1963

5K notes

·

View notes