Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Text

Maggie Brown

Pennsylvania Tribune

2 December 1983

Obituaries

Walter Leuba, 81, leaves collection to Pitt after death

https://66.media.tumblr.com/6fdaaaaa58f8c9778c6d4be023a0a900/tumblr_phoha2eJyJ1xlbvkxo1_540.png

Walter Leuba, a writer, poet, and well-known collector of literature and art, passed away this September at the age of 81. His son J. Christian Leuba confirmed that Mr. Leuba died in his private residence in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is survived by his beloved wife of 45 years Martha, with whom he collected countless books, manuscripts, signed letters, photographs, and woodblock prints, among others.

https://66.media.tumblr.com/39f9d4b6db1026d1093be36fa5d36e10/tumblr_phoharvMdX1xlbvkxo1_1280.png

https://66.media.tumblr.com/858a6cbe11fa0ce40e82f2124b812317/tumblr_phohbdSI0W1xlbvkxo1_1280.png

Mr. Leuba lived a modest life in Pittsburgh working as a case worker for the Allegheny Country department of welfare, which no doubt contributed to his ideologies about social reform, and writing several pieces of poetry and prose, some of which were published in publications or self-published. He also enjoyed contributing to literary journals and crafting letters to the editors of local newspapers regarding issues about which he felt strongly.

Mr. Leuba began donating items from his personal collection several years ago, despite claiming in a 1973 interview that he would “no more dream of leaving [his collection] to a local library than jumping in the river.” However, Mr. Leuba must have experienced a change of heart when he directed Martha to donate his personal library to Hillman Library at the University of Pittsburgh. The array of works in his library illustrate Mr. Leuba’s passion for social justice and reform. Donnis De Camp, who is a co-owner of Schoyer’s Books in Squirrel Hill and assisted in the appraisal of the Leubas’ collection, commented on how highly selective Mr. Leuba was about his collection. Rather than collecting books “in a way that people would buy stock or art,” Mr. Leuba “bought the books because he loved them and wanted to study them,” Mr. De Camp remarked. And he is right – found on the cover page of many of the books in his library is a small, pencil inscription that denotes the day he finished reading each book.

https://66.media.tumblr.com/36a48447fb710dac67f90718b9f0a774/tumblr_phohbxfvyS1xlbvkxo1_1280.jpg

Among the items donated are several historically and socially significant works regarding topics of race and slavery in America ranging from the 18th century to the 20th century. Notable works include a facsimile of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Lincoln in 1863; a 1900 edition of John Milton’s Paradise Lost; and multiple issues of Putnam’s Monthly (one of which is pictured below), a magazine circulating in the North before the Civil War that curated original works of American “literature, science, and art.”

https://66.media.tumblr.com/fed5e36a082c014f483fb9e3aae40d92/tumblr_phohiavPUA1xlbvkxo3_540.jpg

https://66.media.tumblr.com/cb95fee0a75a6651f99f7665cbae7cc2/tumblr_phohiavPUA1xlbvkxo2_540.jpg

https://66.media.tumblr.com/7ef1fb22c2a67880e117abd41dd06b87/tumblr_phohiavPUA1xlbvkxo1_1280.jpg

The July to December 1855 issue of Putnam’s Monthly holds great significance in the discussion of race relations in America as it contains the famed the original serialized publication of “Benito Cereno” by Herman Melville. The novella follows the story of Spanish slave ship run by Captain Don Benito Cereno that is overthrown by its slaves in a revolt. The piece has drawn much critical attention since its publication, with some claiming it is anti-slavery propaganda and others denouncing it for its racist depiction of the slaves who revolted as evil and deceiving in nature. Although the piece doesn’t explicitly condemn slavery, it forces the reader to consider what constitutes freedom and the consequences of denying individuals their own freedom. Illustrations created by Garrick Palmer appear throughout a 1972 publication of Benito Cereno in book form. The black and white woodblock engravings depict the unease and violence throughout the novel. Printed on the sleeve of the hardcover book is a border-to-border illustration of (Benito Cereno’s servant) Babo’s decapitated head on a spike in the middle of a village square after being executed for revolting against the slave owners.

https://66.media.tumblr.com/96c21d0a102ed924450a00076faa3998/tumblr_phohjbTW2m1xlbvkxo1_1280.jpg

Many of the other works in Leuba’s library suggest that he valued “Benito Cereno” for its historical significance as a comment on attitudes towards slavery in America’s pre-Civil War era and a challenge of oppressive institutions. For example, Leuba donated volumes I and II of the 1902 edition of The Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell, a chronicle of the poet and writer’s involvement in the abolition movement through a series of articles he wrote between 1845 and 1848 for “The Pennsylvania Freeman” and “The National Anti-Slavery Standard.”

https://66.media.tumblr.com/88111c074eeb1455a82d79180b5f55d6/tumblr_phohldcOXo1xlbvkxo1_1280.jpg

https://66.media.tumblr.com/520988fab6c756987b32bc7d9d953f01/tumblr_phohldcOXo1xlbvkxo2_640.jpg

Russell speaks fervently and poetically about the immorality of slavery and denounces southern states that wish to secede in an effort to maintain their slavery laws. In a chapter titled “The Prejudice of Color,” Lowell makes impassioned claims about the state of race relations, arguing that “There is nothing more sadly and pitiably ludicrous in the motley face of our social system than the prejudice of color” (16). He shames the “professedly Christian” American people for the hypocrisy of their religious practice, asserting that “we give only a theoretical assent to the doctrines of Christ… [and] though we wear the badges of our religion most conspicuously, we contrive adroitly to hide them away whenever it suits our convenience to break any of its commandment” (18). Lowell’s stance represents a distinctly progressive view in the pre-Civil War era.

https://66.media.tumblr.com/cfb1c9d45c57ef1f08d94856293d2287/tumblr_phohm5g9Iz1xlbvkxo1_540.jpg

A 1969 edition of Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure is another item in the Leubas’ donation that exhibits distinctly progressive views for its time in American history. This narrative, which was originally published in serialized magazines in 1894, follows the tragic love story of Jude, a stonesman, and his cousin Sue, a schoolteacher with unconventional beliefs about education and other social systems. Jude and Sue, who are each married to other people, divorce their spouses and are married only to be ostracized by their community. Woodblock engravings by Agnes Miller Parker depict the utter despair and suffering the main characters experience. Mr. Leuba may have sought out later editions of Jude the Obscure and Benito Cereno for their intricate wood engravings, which constituted a large part of his art collection.

https://66.media.tumblr.com/e63c581b70877a2fe0dc9740fabca78d/tumblr_phohm5g9Iz1xlbvkxo2_540.jpg

The work explores issues of class disparity and education reform, and objections to the institution of marriage and religion. Although these issues are now often discussed, they were revolutionary for their time – something that the Leubas recognized and valued. Leuba may have similarly valued the overarching theme in Melville’s “Benito Cereno” of challenging perennial systems. This also appears in several other Putnam’s Monthly publications donated by the Leubas. In volume II of the July to December publication in 1853, Putnam’s selected numerous pieces for publication that questioned similar institutions. The essays “Education Institutions of New-York” and “Academies and Universities” in this volume examine access to education and the reform of deficient aspects of school systems. As a case-worker for the department of welfare in an urban city, Mr. Leuba was exposed to many of these persistent issues within the public education system.

Though not particularly wealthy, Walter Leuba’s passion for learning about the America’s history of social justice led him to collect an impressive archive of some of the country’s most revolutionary literary content. Mr. Leuba’s library is an invaluable donation to Hillman Library that significantly furthers Pitt’s collection of historically and socially significant works of literature (and art) that have shaped and documented America’s history of race relations and social justice.

___________________________________________________________

Pennsylvania Tribune

January 1856

Letters to the Editor

Note from the editor: A recent volume of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science and Art has evoked strong responses from dozens of our readers, especially regarding discussions of race and the current status of slavery laws, at a time when our political parties are becoming increasingly polarized. Putnam’s Monthly Magazine prides itself as a magazine of “literature, science, and art” that omits author bylines in an effort to encourage the most candid of opinions and produce the most original content. A recent piece published in DeBow’s Review, a southern publication focusing agricultural, commercial and industrial progress and resources, has denounced the publication for being anti-slavery, claiming it was “the leading review of Black Republican Party.” The July to December release of Volume IV includes an array of poems, political and historical essays, scientific observations, and works of literature. Perhaps most notable (and possibly most contentious) of the works is written by Herman Melville is “Benito Cereno,” a fictional narrative of slaves revolting against their Spanish captain Benito Cereno in an effort to reach land in which they are free. When the ship encounters an American sailor and his crew on the island of Santa Maria, the slaves seemingly force Benito to lie to the sailors and concoct a cover story about the ship encountering a storm and losing Spanish crew members. We received an overwhelming number of critiques of the publication offering vastly different interpretations of Melville’s intention and commentary on American society from our readers, many of whom formally submitted letters to the editor. So numerous and thought-provoking were the letters we received that we felt we had to publish several of them in order to do this conversation justice.

To the Editor:

It’s absurd to question Melville’s intentions in publishing this piece. Consider the publication in which Melville originally submitted the piece. All one has to do is leaf through a single month’s publications of Putman’s Monthly to encounter opposition to slavery laws and criticisms of long-standing American institutions. Other works in the very volume in which “Benito Cereno” appears express fervent opposition to the current slavery laws and offers just criticism of the pro-slavery attitude in the south. “The Coming Session,” which appears in the December issue along with the third serialization of “Benito Cereno,” addresses the legality of slavery laws in Kansas in light of an upcoming vote. The author, mirroring rhetoric used in our own Declaration of Independence, bluntly states that “he who believes in the inalienable rights of man” would take an “irreconcilably different” stance from the south on slavery laws (649). He matter-of-factly defines the abolition movement a patriotic one, and in doing so calls on politicians and all of Putnam’s elite list of subscribers to take such a stance.

Matthew Thompson

Philadelphia, PA

To the Editor:

In “The Coming Session,” the author warns that “If Congress … may not say that each human being … shall be legally entitled therein to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,’ then our Union is a chimera, and chaos has come again” (647). In many ways, Melville’s “Benito Cereno” is a dystopian tale of the conflict that arises when one claims that not every human being is entitled to these inalienable rights. In a struggle for freedom, the slaves revolt against their oppressive captain resulting in the deaths of several Spanish crewmen. Later on in the narrative, chaos arises when Captain Delano captures and re-enslaves everyone aboard the San Dominick besides the Spanish crew. Melville illustrated the chaos that is bound to ensue in our divided nation. Putnam’s Monthly aims not only to entertain, but also to educate the public and consider the implications of oppressive social structures. Captain Delano’s character eerily resembles the attitudes of slave owners and sympathizers I have encountered on my family visits to Maryland.

Sarah T. Smith

Boston, MA

To the Editor:

In a Volume II: July to December publication of Putnam’s Monthly in 1853, a Publishers’ Note in the beginning of the magazine clearly defines Putnam’s stance, or lack thereof, on matters that pertain to the public welfare of Americans. It states, “Topics of national and general interest, or relating to the public welfare, will be discussed when there is occasion, with freedom, but not, it is believed, with reckless intentions” (iv). If we are to consider “Benito Cereno” in this light—as a piece that Putnam’s objectively believes has literary or intellectual value—then I am quite disappointed with their judgment. This piece relies on the reader sympathizing with Captain Delano in his suspicions of the slaves. The prejudiced Captain Delano, who captures the members of the San Dominick leading to more bloodshed and ultimately the re-enslavement of dozens of people bound for freedom, never sees retribution, implying that slave owners and their sympathizers will not be held responsible for their cruelty. Instead of rightfully depicting the revolting slaves as desperately trying to escape the cruel and oppressive institution of slavery, they are described as devious, manipulative, and worthy of suspicion. In doing so the narrative does little to humanize these individuals. This piece is riddles with the “reckless intentions” of fostering American prejudices and might only be justified for publication because of Melville’s well-versed prose.

James Wickerman

New York, NY

Works cited:

Hardy, Thomas. Jude the Obscure. The Limited Editions Club, 1969.

Lowell, James Russel. The Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell. Houghton Mifflin and Co., 1902.

Pitz, Marylynne. “Final Chapter in Lifelong Love of Books.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 29 Dec. 1988, pp. 13–14, news.google.com/newspapers?id=Q7BRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=920DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5865, 7836772.

Putnam's Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science, and Art. July to December, 1853. II, G. P. Putnam & Co., 1853.

Putnam's Monthly Magazine of American Literature, Science, and Art. July to December, 1855. II, G. P. Putnam & Co., 1855.

0 notes

Text

The Views of the Abolitionists

Elise Hoffman

We have all heard about the Civil War and how slavery was a major reason for the war. Sometimes people argue otherwise, that the Civil War had other motives. Looking into the texts of the time, it is clear that the topic of slavery was a hot topic, discussed in multiple forms. Take Benito Cereno for example. This text was published periodically throughout the mid 1800’s, but it was far from being the only text that shows the dissent many people had for slavery. Frequently, people were able to use their religion to explain why they thought slavery was wrong. Even though most of the nation followed Christianity, people were able to see their errors by the rules dictated their religion.

First, we have the Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell. Lowell was a prolific writer in the North (vi) during this time. His intent was clearly against slavery. On pages 17 and 18 he argues that it is man’s Christian responsibility to not participate in slavery and to protect other races because they have done nothing wrong to white people. Lowell was a white man who wrote many letters during his life to combat slavery.

Another way to communicate was through music. Many have heard about slaves singing songs while working as their own form of protest or comfort in misery. What you don't hear about every day are songs written by other people during this time. George W. Clark was a white songwriter during the time period of the Civil War. He published a book called The Liberty Minstrel full of songs against slavery, illustrating how difficult life was for slaves. In the foreword of this book, Clark write to express his thoughts on slavery. He says that he has "an ardent love of humanity--a deep consciousness of the injustice of slavery--a heart full of sympathy for the oppressed, and a due appreciation of the blessings of freedom" (iv). Clark knows that he is privileged, but still feels the need to express why other people should care about slavery. His music poetically captures the sadness and despair he sees in the way slaves are treated. He humanizes them by giving them complex emotions. It is not often that 19th century white men speak of slaves as humans. It is much more recognizable to hear slaves referred to as property. This is not the case for Clark. Below are some examples of the songs he wrote demonstrating the distress that slaves go through as they are bought and sold like the property despite the fact that they are human beings.

Perhaps one of the most shocking parts of this is the inclusion of the dehumanization of slave owners. This next song shows how shallow a slave owner is for selling his slave in return for a watch.

Last is an image taken from The American Anti-Slavery Almanac for 1838. Though this comes well before Putnam's Monthly, this shows even more how much the Civil War was focused around slavery (perhaps more so because it is published earlier). Despite the name, this was first published in 1836. This image shows a white man trying to chop down a tree of slavery while other white men are trying to hold it up. At the time slavery was a hard battle to win. This image shows how it was the many (pro-slavery) against the few (abolitionists). However, even though there is only one man chopping down the tree, there are others in the background cheering him on. He may be alone in the direct battle, but he has support. This deliberately shows how slavery was a battle that white men could fight too. The quote under the image ties this concept back to the Christian responsibility against slavery. The quote is from Jeremiah 22. It reads: "Thus saith the lord, Execute judgement in the morning, and deliver him that is spoiled out of the hand of the oppressor." This means that it is a Christian's responsibility to make the judgement that slave owners are wrong and the slaves need to be set free so that they may live their lives peacefully as Christians.

Text Sources:

Clark, George W. “The Liberty Minstrel.” 1844.

Lowell, James Russell, and William Belmont Parker. The Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell. Houghton Mifflin and Company, 1902.

SOUTHARD, N. AMERICAN ANTI-SLAVERY ALMANAC, FOR 1838, Published by Isaac Knapp, 1836.

0 notes

Text

Walter Leuba’s Interpretation of Benito Cereno Illuminated Through His Collections

https://alipiccianibcproject.tumblr.com/post/179770629692/walter-leubas-interpretation-of-benito-cereno'

Alessandra Larimer-Picciani

0 notes

Text

Benito Cereno and the Leuba Collection

Nicolette Webb

Benito Cereno, the controversial and thought-provoking tale by American author Herman Melville, was first published in a serial manner in the magazine Putnam’s Monthly, which first debuted in 1853, a time which was both haunted by the tensions of uncertainty and the divisiveness of ideals. It contained articles on a variety of topics including literature, science, art, and politics and could thus be analyzed as an object of insight into the minds of its 19th century readers and their various opinions. The Special Collections Room at Hillman Library on Pitt’s campus contains several volumes of the magazine. Benito Cereno was serialized in Volume VI, however Hillman’s copy of this volume was deemed too fragile for further use. The following images will therefore be excerpts from Volume II of Putnam’s Monthly, published two years prior.

The pages of Putnam’s Monthly provide a unique insight into how Melville’s contemporaries may have been thinking about issues of race and slavery. For instance, “Wensley”, a piece of literature advertised as a “story without a moral”, calls attention to the dangers of a “gang of black rascals” and “black ruffians” (604). It makes note also of the “involuntary immigration of the negro race” from the Guinea Coast (85). In a Letter from Henry C. Carey, the leading 19th century economist and economic adviser to President Abraham Lincoln writes of those who may edit “a journal in which pro-slavery may be taught at one time and anti-slavery at another, as the one or the other may appear most likely to advance his private interests” (343). Carey also suggests that “slavery and the slave trade are not confined to the Negro race…but that they prevail…under all nations and at all times” and can only be eradicated through the adoption of more “enlightened principles” such as those used by the British (104). He appears to use the African slave trade as an area of reference in discussing what he deems as the “intellectual slavery” of America’s failure to adhere to his standards on free trade philosophy which, because it serves little purpose beyond a casual mention and reaching comparison, highlights the normalization of slavery during this time. This is further exemplified in his later statement, “I am anxious to see the educated white man free in the exercise and expression of thought, as to see the ignorant negro free in the application of his muscular powers” (231) which despite being a seeming proponent for the freedom of Africans, depicts them in terms of the racist stereotype that they are less intellectually capable than white men. The commonplace nature of slavery is also showcased in a story titled “Miss Bremer’s Home of the New World” in which a slave auction is offhandedly mentioned by one of the female characters, as she remarks of the salves at market, judging their value on their “athletic figures” and “good countenances”, even pointing out “one negro in particular – his price was two thousand dollars – to whom [she] took a great fancy” (671).

From the digital version of Volume VI of Putnam’s Monthly, more instances of discussion involving race and slavery are seen. An article titled “The Kansas Question” names slavery as the “real and vital question of the day” (425) and mentions that slavery may still exist, but it exists as “an acknowledged evil” (428). A later article declares that the African American is “no joke, and no baboon: he is simply a black man, and I say: Give him fair play and let us see what he will come to” (612). Despite this assertion, the article still uses racial slurs. What, then, might readers of Putnam’s Monthly during its original publication have thought about Benito Cereno? It is possible that some more radical readers may have embraced Melville’s portrayal of an intelligent black man. Despite some calls for emancipation and freedom, however, there remained a significant amount of racism toward African Americans, as evident in the various portrayals and mentions found throughout these volumes of Putnam’s Monthly. The notion that a white man could be outsmarted by his own slave was indeed controversial and most likely offended many. It was, on the other hand, a very ambitious tale and one that kept talks of freedom brewing in the decade leading up to the American Civil War, which would eradicate slavery once and for all.

Something interesting to note is that several volumes of Putnam’s Monthly which are in Pitt’s possession came to be so via the Leuba family when they donated several thousands of pieces to Pitt’s library in the 1970s, otherwise known as the Leuba Collection. Although Putnam’s Monthly contains some unflattering portrayals of African Americans as well as writings which promote various problematic stereotypes, it does generally favor emancipation. Likewise, the contents of the Leuba Collection suggest that they were interested in promoting social justice. One such piece is The Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell, which analyzes various aspects of the slavery debate in an attempt to show “the necessity of immediate emancipation” (200).

Other instances of references to race can be seen in the printed images and the stories which they depict. The following prints, for instance, are from Jack London’s Sea Tales. It is suspected that Jack London subscribed to the ideals of Social Darwinism and held some white supremacist views because of this. In an 1899 letter, he states, “An evolutionist, believing in Natural Selection, half believing Malthus’ “Law of Population” and a myriad of other factors thrown in, I but cannot as hail as unavoidable, the Black and the Brown going down before the White.”

The Leuba Collection also contains prints from John Steinbeck’s The Pearl which follows a family of Native Americans and addresses issues of racial discrimination.

It is clear by these inclusions that the Leuba family was fascinated in racial relations and discussions of race in various forms of art. More information can be found in the Special Collections Room of the Hillman Library of in the digital library of the Leuba Collection.

0 notes

Text

Melvill's Liberation of Mind and Its Further Impacts

https://zealousduckphilosopher.tumblr.com/post/179792049517/melvilles-liberation-of-mind-and-its-further

0 notes

Text

Contextualizing Melville’s “Benito Cereno” both in Putnam's Monthly and the Leuba Collection ---Caroline Gish---

https://coolsaladllama3000.tumblr.com/post/179774514922/gentle-jazz-filters-in-to-where-i-sit-perched-up

0 notes

Text

Putnam's Monthly, Benito Cereno, and The Leudas

The following messages were exchanged between two Pitt English majors:

Sam: Hey! Are you busy later?

Julia: Yeah, I'm working on this project for Lit 1. Basically we have to read through an old magazine from the 1800s.

Sam: OMG! I’m in Lit 1 too! With Ryan McDermott????

Julia: Yeah! We’re doing the project on “Putnam’s Monthly”. Basically it is a collection of writings from the best and newest writers of a time period. In our class we worked on an online edition of the 1855 “Putnam’s Monthly”. It was around this time that they were abolishing slavery- it’s really cool to see how the writers spoke about slavery at the time.

Sam: I thought the same thing! I read a couple pieces from the 1855 copy of “Putnam’s Monthly”. The writers of the time period talk very openly about race and slavery, they don’t even hesitate when using derogatory language! It’s pretty crazy to read stuff like that today, especially with all of the things happening in our current political world.

Julia: Yeah I felt the exact same way. What I found really interesting was that all sides of the slavery argument were included in the magazine- it wasn’t necessarily one side or the other. There were sides that were pro-slavery and there were sides that were anti-slavery. They were jumbled in right next to each other! Pretty crazy.

Sam: Did you read any of the pieces?

Julia: Yeah, I read a piece called “About Niggers” and a piece called “Only a Pebble”. These pieces were really different from one another. The first piece obviously has an offensive term in the title, which I think is what made me interested in reading it. I thought it would be pro-slavery because of this term, but it actually fights for the equality of African Americans. This wasn’t something that I was expecting at all. “About Niggers” had characters and dialogue and told a story of equality. “Only a Pebble” was written almost like a poem. There were no characters or dialogue really, but there was kind of a story line. In this story, humans were unappreciative of the pebble for all of the value and history that lay beneath the surface. The author argued that just because something doesn’t seem valuable right of the bat does not mean that it isn’t worth anything.

Sam: Do you think that “Only a Pebble” was about slavery?

Julia: I’m not really sure. What I do know is that a lot of the authors in Putnam Monthly did not feel comfortable taking a stance. Because of this, they would tell stories like the pebble which took an indirect stance. If I had to guess, I would say that the pebble stood for African Americans and the humans were White Americans. The white Americans didn’t appreciate the African Americans for the value that they could really contribute.

Sam: You know that Pitt's Special Collections has copies of Putnam, right?

Julia: No way! Do you have pics?

Sam: Yes!

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179795046368

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794622228/putnams-monthly-1853

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794616533/putnams-monthly-1853

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794611123/putnams-monthly-1853

Sam: I see. What aboutBenito Cereno? We had to read that for class right? What is that about?

Julia: Yeah, we had to read Benito Cereno. Benito Cereno is the captain of a Spanish ship. Captain Amano boards the ship when it approaches the harbor to see what is going on. Delano immediately realizes that all of the people on the ship have been through some pretty rough times, and that this is (or at least was at some point) a slave ship. Captain Benito is not doing well, but Babo, his slave, his helping him out. Delano notices weird culture on the ship during his time there. After a while, and a couple more weird instances, Delano decides to leave. He goes to get on his small boat and Benito jump son quickly as well.

Sam: Does he leave with Delano?

Julia: Not quite… Babo attacks Benito. The rest of the story is told in different types of court documents. People have taken different stances on what Melville really meant by telling this story. Some people argue that just like the pebble story, he didn’t really want to take a stance on slavery. I don’t think this is true though, and I tend to agree with other arguments.

Sam: What are the other arguments?

Julia: Some people argue that Melville was making a point about the intelligence of African Americans. He wanted to make a statement that the slaves outsmarted the workers of the ship, and he allowed several instances to show that (the instances that made Delano uncomfortable).

Sam: Was Benito Cerenopublished in “Putnam’s Monthly”? Is that how you saw it?

Julia: Benito Cerenowas published in Putnam’s Monthly in sections.

Sam: Do you think that Benito Cerenoplayed a really big role in “Putnam’s Monthly”?

Julia: I mean it is really clear when reading through the 1855 “Putnam’s Monthly” that this was the only topic of political conversation during this time in the United States. I don’t really think that Melville was the main focus during this time or anything, but I definitely believe that this was the focus of their conversation and that he added to that a significant amount.

Sam: Where can you read Benito Cereno?

Julia: Well, there’s actually a collection at Pitt that has Benito Cereno. It’s called the Leuba Collection. Walter and Martha were husband and wife and were really into collecting different pieces of art and literature. Their collection was huge, mainly consisting of pieces within their lifetimes which was the majority of the 1900s. I actually just looked on the Pitt library website, and it says that their collection consisted of all kinds of things like magazines, books, papers, wood block art, letters from famous artists and authors, and a lot of other notable pieces of collectables. It is not just literature. It is all kinds of art! Their collection seems kind of random because it was just things that the couple was interested in. They have several copies of Putnam’s Monthly within the collection too!

Sam: Are there other things in the collection that make the Leuba’s significant?

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179795030828

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791773878/leuba-cover

Julia: Well, actually they have a couple pieces of art in the collection that are really cool and have a lot to do with the discussion of race. The first thing that I noticed that was really cool was that they have a bunch of calendars decorated with artwork. On one calendar was a picture of a large white man in a large hat and beard with his arms around a smaller African American man. The African American man has his hand placed on the chest of the white man. The white man is looking away from the camera while the African American man is looking directly at it. It seems as though this is Benito with his arms around Babo. It looks like here, even in this calendar, that Babo knew what is intentions were with Benito. It is chilling to look at knowing how the story would play out.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791580288/babo-and-cereno-melvilles-bentio-cereno-calendar

Sam: Were there any other calendars like that?

Julia: Yes. Also something important: this collection was created in the 1900s, long after the slavery issue was handled. During this time though, there were other issues of race occurring in the United States. The issues of race and inequality are clearly something that was important to the Leubas. They have two photograph calendars in the collection from John Steinback’s The Pearl. This story was about a poor Native American family who was treated differently from the people in their town because they were poor. When they found a large valuable pearl, everyone started treating them differently because they had wealth. I think it shows a lot that the Leubas wanted to continue their collection on race and inequality- two main points in Melville’s story.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791569803/steinbecks-the-pearl-calendar-for-september

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791560498/steinbecks-the-pearl-calendar-for-august

Sam: So the other calendars had pictures representing this inequality on them?

Julia: Yes. These calendars had weird pictures based upon the Steinback’s story.

Sam: Were there other pieces in the Leuba’s collection on race and slavery?

Julia: Yeah there were a ton!

Sam: Like what?

Julia: Well, there was a set of two books called the Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell. Here are some pics!

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794859583/anti-slavery-1

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794864198/anti-savery-2

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794868933/anti-slavery-3

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794872713/anti-slavery-4

Sam: James Russell Lowell? Who is that?

Julia: Lowell was a poet and critic. He worked a lot on the anti-slavery movement and used his poetic talent in his favor.

Sam: Was there anything else that I should check out?

Julia: There were a ton of interesting books in the Special Collections Department that related to the issues of slavery. One more that I thought was so interesting is the book Black Mother by Basil Davidson. This gave a detailed history about the American slave trade from the beginning to the end. I thought that the inside of the jacket gave a good overview of what it was about.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794948773/black-mother-1

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794953498/black-mother-2

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794959623/black-mother-3

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794963813/black-mother-4

Sam: So, Julia, what do all of these things have in common?

Julia: Looking at “Putnam’s Monthly”, the Leuba collection, and our politics today, the issues of race and inequality have been able to transcend time. The authors’ stances back in the 1855 magazine are still very relevant to today’s politics. It’s really cool that the Leubas were very in tune with that when they created their collection. I think it’s also really neat that they had all different types of media to learn more about the anti-slavery and race movement. They had calendars with photographs, wood blocks, countless collections of papers and books, and so much more.

Sam: Wow that’s awesome! I’ll definitely have to check it out f

0 notes

Text

Olaudah Equiano and Slavery

As a high school student, I was never taught in depth about slavery, the Abolitionist Movement or the key figures involved. If you are a teacher in the Pittsburgh area looking to educate or further educate your students on these topics, you’ve come to the right Tumblr post. In this post I look at and analyze two different versions of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano and one edition of the Slave’s Friend. I have included materials that direct attention towards works for elementary as well as high school students. I have incorporated different resources that teachers can use to further their knowledge and present to their class. There are online resources such as digitized copies of additional works from this time period, which can be found on “WorldCat”. It is important to keep in mind however, that will these resources can be extremely helpful, they come with limitations. The Hillman library does not offer much on Olaudah Equiano, but it does have other works that focus on relevant topics, like slavery. If you would like more knowledge about Equiano himself, it would benefit you to branch out to other libraries and look at multiple online sources. It is my hope that I can help teachers provide information to their students about an important event in history, one that I was not educated on.

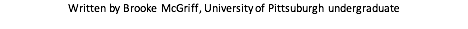

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/the-life-of-olaudah-equinao

- This is an image of the of the second edition, volume 1 of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, Gustavus Vassa, the African. He published this successful autobiography in 1789. This picture can traced back to the online archive at The British Library Collections, where it is being held . Throughout this tumblr post, I will analyze and describe an adapted children’s book version, as well as a later publicized and edited version of Equiano’s Narrative.

- For those of you who need some background information about Olaudah Equiano, I have included a short summary. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is a story about an ordinary man who lived an extraordinary life. Olaudah Equiano was born into the Ibo tribe, part of the Nigerian village of Isseke in 1745. At the age of eleven, Equiano and his sister, were kidnapped by slave traders and forced into a life of slavery. The siblings were separated and young Olaudah never saw his family again. He spent ten years as a slave in the West Indies, America and British Navy. He experienced many life-changing events such as: the religious revival in Europe and America, an expedition to the Arctic, an eruption of Mount Vesuvius, battles in the Seven Years’ War and the initial divisions of the American Revolution. He eventually saved up enough money from his personal trade business, that he bought back his freedom in 1766. He wrote his autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano in 1788 and it was published in 1789. His novel is one of the earliest slave narratives. The book was an imperative foundation of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which terminated the African trade for Britain and its dependencies. Olaudah Equiano was part of the Sons of Africa, an abolitionist group which was composed of eminent Africans who lived in Britain.

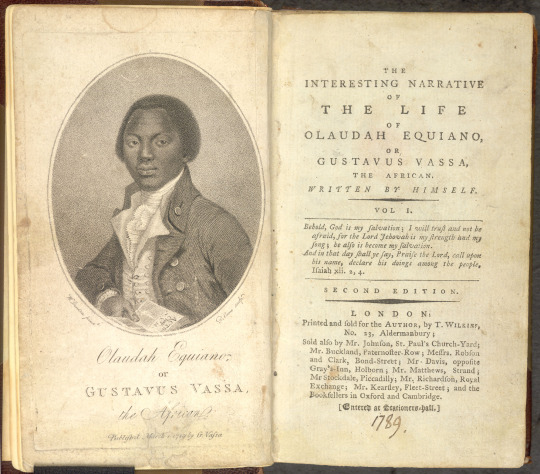

The Kidnapped Prince

- The Kidnapped Prince is a version of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano. Published in 1994, it tells the story of Equiano, however, it does so in a more simplistic way. This edition of Equiano’s Narrative was written predominately for an audience of late elementary/early middle school students. This book was written by Equiano, but then adapted by Ann Cameron with an introduction by Henry Louis Gates Jr. Since the intended readers were younger children, the novel was modernized and some of the language was shortened for a better understanding and comprehension. This adaptation version was cut short, ending two-thirds of the way through Equiano’s original publication, at the point where he regains his freedom. The goal of this revised version of Equiano’s Narrative was to provide children with a text in which they could easily apprehend but one that also preserved the essence of the author’s time and some of his original language.

- This version of Equiano’s Narrative is a hardcover copy. On the front cover, there is an illustration of Equiano as a young boy. He is clearly depicted as a slave, with his hands cuffed together in front of him, and he is standing in front of a slave ship. The text inside the book is large and spaced out, it is obvious to assume that it was written for children. The condition of the book overall is well-kept. There is no damage to the pages or the cover. This shows that the book has been taken care of and handled gently.

- I took this picture from the middle section of The Kidnapped Prince. Pictured above is a map that shows the travels in which Olaudah Equiano embarked upon during the years he was held captive as a slave. I found the design of this map to be very intriguing. Most maps from the 18th century do not include such distinct topographical features as this one does. I have encompassed below, a map you would typically see in the 1700s. The one displayed in The Kidnapped Prince isn’t as intricate to follow. This allows your elementary/middle school students to easily understand the significant message the map is showing.

- This is a more accurate depiction of Equiano’s travels, one that we might expect to see from an 18th century time period. After doing some research, I found that this map was drawn by a cartographer and composed by a historical geographer. Edward Oliver (the artist) and Miles Ogborn (the preparer) were both intellectuals that worked at Queen Mary, University of London. This is just a ‘thumbnail’ image of the map, and if you’d like to look into further detail about Equiano’s travels, I recommend reading Miles’s article “'Global historical geographies, 1500-1800’ in B.J. Graham and C. Nash (eds) Modern Historical Geographies (Harlow: Longman, 2000).”

The Slave’s Friend

- For the students you are teaching to gain a thorough grasp and understanding of the discussed material, it would be beneficial to compare it to a similar text. In this post I chose to analysis The Kidnapped Prince and The Slave’s Friend together. I wanted to relate an edition of Equiano to another work published during the same time period that centered around the same topics. I went to the Special Collections section of the Hillman Library, where I found The Slave’s Friend.

- The Slave’s Friend is a collection of anti-slavery writings. Written and published by R. G. Williams in 1839, this book was a typical abolitionist periodical aimed at representing Africans, slaves and freemen. R. G. Williams wrote these collections for the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS), focusing on pro-Christianity and anti-slavery. This anti-slavery press was a principal part in the crusade against slavery in America. The Slave’s Friend was originally an abolitionist magazine targeted at a young audience in the United States that ran between 1836-1838. The directed audience for this text were young elementary students age 6-12. The content in The Slave’s Friend was full of stories, anti-slavery poetry, religious passages, relevant news items for other sources and original writings. The magazines were inexpensive, with a price of one cent per copy. During the first year, over 200,000 magazine printings were distributed. Due to financial instability, the magazine version of The Slave’s Friend had to halt production in 1838; the last issue made was Volume IV, No. II.

- Hillman’s Special Collection had in their possession, the small pocketbook version of The Slave’s Friend. This book was very small, measuring only 4.5X2.75 inches. The front and back covers were a light brown with the spine being darker. The pages were a tan color with a darker discoloration around the edges. It was clear to see that this piece of writing was extremely old. The spine and binding were broken, and the pages were tarnished. The wear and tear on this book show that it has been handled an extensive amount of times. The pages are thin and on each there are two-page numbers, this indicates that each volume was paginated more than once. The poems, hymns and volumes are showed on pages of different colors. Most of the messages to the readers and poems appear on yellow or blue pages, where the beginning of a new volume is often displayed on an off-white page. Although The Slave’s Friend is a typical piece of children’s literature that you would see during the 19th century, I was surprised with its layout. In my opinion, this book didn’t feel or look like something a child would like to read. The pages and text were very small and the pictures were not colored. This book also didn’t have an appealing cover page, one that might be intriguing to children and pull them in. However, I thought that the different colored pages did bring some flavor and brightness to the publication, making it more enjoyable to read. I couldn’t find concrete evidence depicting the significance for why The Slave’s Friend was published the way it was, so I thought I’d include some insight of my own thoughts and feelings. It was interesting to see how children’s literature has changed so much over time. Today, we see large, colorful books with easy to read words on each page, along with colored images.

- Pictured above is the Hillman Library’s Special Collection copy of The Slave’s Friend in the palm of my hand. This image shows an accurate representation of the true size of this book.

https://safe.txmblr.com/svc/embed/inline/https%3A%2F%2Fyoutu.be%2F5IuT7hjOj3M#embed-5be0b331109f2688067128

youtube

- This video shows a glimpse inside the pages of The Slave’s Friend.

- A recurrent theme found throughout The Slave’s Friend was cruelty. The stories were often very blunt and illustrated violent behavior the slaves had to face. This relates to The Kidnapped Prince and Equiano’s Narrative, as he recounts stories of his enslaved friends and how they were sadistically tortured and punished. This book relates further to Olaudah Equiano’s autobiography because it incorporates strong religious appeals. Numerous articles in The Slave’s Friend don’t focus on slavery and the abolition movement as much as morality and the importance of religion.

- The significance of The Slave’s Friend was that it familiarized the youth with controversial subject matter and issues. It was the hope that by making them aware of the horrors of slavery, they would see the need to abolish it.

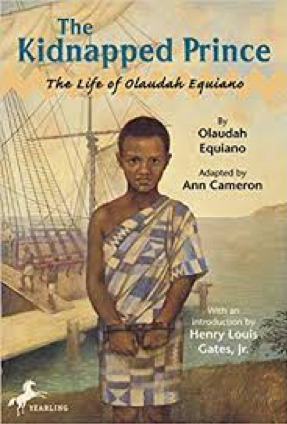

The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano

- The title The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano holds great significance in itself. Equiano titles his autobiography this way for a particular reason. He included his own name to establish to readers his African roots. The full title of his original print of this book is The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, The African. The added Gustavus Vassaidentifies his slave name and The African as a depiction of his people. Readers can gain a lot of knowledge about this narrative just from the title alone.

- The published version of Equiano’s Narrative shown above, is intended for a high school student audience. This isn’t one of Equiano’s original prints, it is the text of a Bedford Books edition which follows the first American printing. The editor of this publication, Robert J. Allison didn’t make a lot of significant changes to the text. There were only minor changes in the spelling and punctuation, insertion of paragraphs, and he added notes to the text to help explain to today’s readers, Equiano’s late eighteenth century event portrayals.

- This edition of The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano is a 1995 paperback copy. It is roughly 5.5X8.25, contains a comprehensive introduction, illustrations and a chronology. The book is in very good shape, there are no tears or any discoloration of the pages. The pages are an eggshell white and the text is typed out and easy to read for students.

http://www.briefhistories.co.uk/olaudahequianotimeline.html-

- This image is a timeline of the significant events in Olaudah Equiano’s life. It is important because it gives readers a brief history of Equiano’s life with exact dates for a better understanding of the chronology of his experiences. I provided the link above, in case of any additional interest or curiosity.

- This description of a slave ship was distributed by Thomas Clarkson with his 1786 Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species. This diagram of a slave ship is an iconic image in the world of the early British Abolitionist Movement. This image was submitted as parliamentary evidence in the filing of the bill that was eventually passed for the Abolition Act. I located this picture to its source, the British Museum’s online collection.

III.

TO THOMAS CLARKSON,

On the final passing of the Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, March, 1807.

Clarkson! it was an obstinate Hill to climb: How toilsome, nay how dire it was, by Thee Is known,—by none, perhaps, so feelingly; But Thou, who, starting in thy fervent prime, Didst first lead forth this pilgrimage sublime, Hast heard the constant Voice its charge repeat, Which, out of thy young heart’s oracular seat, First roused thee.—O true yoke-fellow of Time With unabating effort, see, the palm Is won, and by all Nations shall be worn! The bloody Writing is for ever torn, And Thou henceforth shalt have a good Man’s calm, A great Man’s happiness; thy zeal shall find Repose at length, firm Friend of human kind!

- I have included the congratulatory sonnet that Wordsworth wrote to Thomas Clarkson for his success in the passing of the Bill for the Abolition of the Slave Trade. This poem holds significance because it shows that Equiano and his story connects to a larger movement and affects a diverse population.

- This photograph of a medallion represents the anti-slavery movement symbol. This image is featured in the last few pages of Equiano’s Narrative, the 1995 version. It was designed and manufactured by Josiah Wedgwood, as early as 1787 and adopted as the seal of the Society for the Abolition of Slavery. I gathered this information from the Library of Congress. This image persisted as the symbol for the abolition movement through the American Civil War. The question “Am I not a man and a brother?” appeared on the title page of Equiano’s autobiography, the 1815 edition. While the slogan “Am I not a man and a brother?” can be seen on the 1815 edition of Equiano’s Narrative, it did not originate from there. This design was circulating as an image of abolition before Equiano’s Narrative. Later publishers put this symbol on title pages of stories with similar plots to tell readers that this book is part of a familiarized movement. I continued my research on this symbol through the Library of Congress, and learned that this figure sent a powerful message across the globe. The kneeling man with outstretched hands and shackles around his wrists and ankles, represents an enslaved African. Across the top the words read, “Am I not a man and a brother?”. This image was replicated onto multiple items during this period. It is known as the first and most distinguishable image of the 18th century Abolitionist Movement. It was and still is today, viewed as a powerful object that signifies morals, principles and the benevolent mission of the abolition movement.

- While reading this narrative, to see things through the eyes of Olaudah Equiano, it is crucial to know and understand the arguments he had against slavery. He had multiple arguments against the slave trade; it destroyed lives and families, it was morally wrong and the trade didn’t make sense economically. In later parts of the narrative, we see how Equiano’s new Christian views shape his negative belief of slavery. Bible verses are significant to this novel because they are one of the most convincing areas of his argument. He encourages slave traders and slave owners to become more knowledgeable of the Bible and all that it offers and to apply it to their own lives. In addition to his religious reasoning, Equaino used economic arguments. He created an argument that slavery should be abolished not only because of the inhumane cruelty, but because the British economy would benefit. He argued that, “Population, the bowels and surface of Africa, abound in valuable and useful returns; the hidden treasures of centuries will be brought to light and into circulation. Industry, enterprise, and mining will have their full scope, proportionally as they civilize. In a word, it lays open an endless field of commerce to the British manufacturers and merchant adventurer. The manufacturing interest and the general interests are synonymous. The abolition of slavery would be in reality an universal good.” (Equiano, 194).

- The above picture is one that I took while at Hillman’s Special Collections. It includes all of the literary works discussed in this post, side by side. I thought this was a good visual that showed the differences and significance of each work. It is clear to see that The Slave’s Friend (far left) holds the biggest difference of the three publications. This book is much smaller and older than the other two, which would make sense since it’s an original copy (1839). The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (middle) and The Kidnapped Prince (far right) share more similarities, as they range close to the same size and they both were published within a year of one another (The Kidnapped Prince, 1994/The Interesting Narrative, 1995). As time changes, literature becomes more modernized. From what we know about The Slave’s Friend and the modernized editions of Equiano’s Narrative, it’s easy to see how literature has developed overtime. All three of these publications give students supplemental material which will more strongly develop their knowledge, not only on Equiano and slavery, but also literature throughout the years.

Works Cited:

“Aboard a Slave Ship, 1829,” EyeWitness to History, www.eyewitnesstohistory.com (2000).

Cameron, Ann. “The Kidnapped Prince.” Children’s Books , 2011, www.anncameronbooks.com/nonfiction/the-kidnapped-prince.html.

Equiano, Olaudah, and Ann Cameron. The Kidnapped Prince The Life of Olaudah Equiano. Aflred A. Knoph, Inc, 1995.

EQUIANO, OLAUDAH. The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano: Written by Himself. Edited by Robert J. Allison, Bedford Books, 1995.

Geist, Christopher. The Slave’s Friend: An Abolitionist Magazine for Children. Ohio State University Press, www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20771128.pdf.

Olaudah Equiano’s Travels - a Map, Feb. 2002, www.brycchancarey.com/equiano/map1.htm.

“Olaudah Equiano Timeline.” BRIEF HISTORIES, www.briefhistories.co.uk/olaudahequianotimeline.html.

Onion, Rebecca. “How an 1830s Children’s Magazine Taught Hard Truths About Slavery.” Slate Magazine, The Slate Group, 27 Jan. 2016, www.slate.com/blogs/the_vault/2016/01/27/how_an_1830s_children_s_magazine_taught_hard_truths_about_slavery.html.

“The Slave’s Friend.” The Slave’s Friend | Teach US History, www.teachushistory.org/second-great-awakening-age-reform/resources/slaves-friend.

0 notes

Text

Benito Cereno

Jacob Williams

Herman Melville, writer of Benito Cereno, can be seen as a kind of dual figure, regarding his stance on slavery. The story Benito Cereno is a narrative told from the perspective of the captain, Amasa Delano. This takes place during the late 1700’s when the slave trade was a thriving business.

This dual stance comes into play when considering the publication in which this was included as well as the writer. The publication, Putnam’s Monthly, has been considered a large proponent of the abolition of slavery. Often regarded similarly to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, as they both took the same stance around similar times. Thus, by publication this piece can be considered an anti-slavery piece. On the contrary, Melville never attempts to take a strong stance against slavery. This lack of a position lets the reader draw their own conclusions on the author’s intentions. This is extenuated by the fact that Benito never makes any strong judgements based on race. Rather, he comes off as almost neutral as to the issue of slavery. A noticeable act of indifference comes from the text,

Three black boys, with two Spanish boys, were sitting together on the hatchets, scraping a rude wooden platter, in which some scanty mess had recently been cooked. Suddenly, one of the black boys enraged at a word dropped by one of his white companions, seized a knife, and though called to forbear by one of the oakum-pickers, struck the lad over the head, inflicting a gash from which blood flowed. In amazement, Captain Delano inquired what this meant. To which the pale Benito dully muttered, that it was merely the sport of the lad. (Melville, 361)

This, Benito’s reaction to a racially charged assault, observed by Delano on Cereno’s ship; shows his indifference and neglect to tack a stance either way. In a way, this is Melville taking neither concrete stance on slavery, merely talking about the issue and rationalizing it.

In addition, Captain Delano seems to think highly of the master/slave relationship. This is derived from Delano internalizing on the relationship between Cereno and Babo, his slave assistant.

Sometimes the negro gave his master his arm, or took the handkerchief out of his pocket for him; performing these and similar offices with that affectionate zeal which transmutes into something filial or fraternal acts within themselves but menial; and which has gained for the negro the repute of making the most pleasing body servant in the world; one, too, whom a master need be on no stiffly superior terms with, but may treat with familiar trust; less a servant than a devoted companion. (Melville, 357)

This excerpt taken from Benito Cereno clearly shows Delano imagining and glorifying the relationship between slave and master. Glamorizing this relationship further refutes this piece’s anti-slavery background and leads the reader to draw the conclusion that the author supports these sorts of Forced slavery relationships. This is in fact a strikingly different viewpoint from another piece within Putnam’s Monthly entitled About Niggers. In which, the author states “The nigger is no joke, and no baboon; he is simply a black-man, and I say: Give him fair pay and let us see what he will come to.” (Anonymous, 612). The quote contrasts Delano’s view of Babo, which may reflect on his views of all African people.

Due to these strange indifferent and pro-slavery instances within the novel; one can conclude that its significance within the anti-slavery movement may be less than what it has been exaggerated to. Upon a cursory glance many readers may have been placated with this superficial anti-slavery tale, however, a reader that chooses to examine further may realize this text is not that.

Works cited:

Anonymous, Anonymous. “About Niggers.” Putnam's Monthly, 1855, p. 608

Melville, Herman. “Benito Cereno.” Putnam's Monthly, 1855, p. 353.

0 notes

Text

Benito Cereno, Putnam's Monthly, Leuba Collection

Julia McDonald

The following messages were exchanged between to Pitt English students.

Sam: Hey! Are you busy later?

Julia: Not really. I’m busy now thought. I am working on this project for Lit 1. Basically we have to read through an old magazine from the 1800s.

Sam: OMG! I’m in Lit 1 too! With Ryan McDermott????

Julia: Yeah! We’re doing the project on “Putnam’s Monthly”. Basically it is a collection of writings from the best and newest writers of a time period. In our class we worked on an online edition of the 1855 “Putnam’s Monthly”. It was around this time that they were abolishing slavery- it’s really cool to see how the writers spoke about slavery at the time.

Sam: I thought the same thing! I read a couple pieces from the 1855 copy of “Putnam’s Monthly”. The writers of the time period talk very openly about race and slavery, they don’t even hesitate when using derogatory language! It’s pretty crazy to read stuff like that today, especially with all of the things happening in our current political world.

Julia: Yeah I felt the exact same way. What I found really interesting was that all sides of the slavery argument were included in the magazine- it wasn’t necessarily one side or the other. There were sides that were pro-slavery and there were sides that were anti-slavery. They were jumbled in right next to each other! Pretty crazy. Here are some pictures.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794611123/putnams-monthly-1853

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794616533/putnams-monthly-1853

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794622228/putnams-monthly-1853

Sam: Did you read any of the pieces?

Julia: Yeah, I read a piece called “About Niggers” and a piece called “Only a Pebble”. These pieces were really different from one another. The first piece obviously has an offensive term in the title, which I think is what made me interested in reading it. I thought it would be pro-slavery because of this term, but it actually fights for the equality of African Americans. This wasn’t something that I was expecting at all. “About Niggers” had characters and dialogue and told a story of equality. “Only a Pebble” was written almost like a poem. There were no characters or dialogue really, but there was kind of a story line. In this story, humans were unappreciative of the pebble for all of the value and history that lay beneath the surface. The author argued that just because something doesn’t seem valuable right of the bat does not mean that it isn’t worth anything.

Sam: Do you think that “Only a Pebble” was about slavery?

Julia: I’m not really sure. What I do know is that a lot of the authors in Putnam Monthly did not feel comfortable taking a stance. Because of this, they would tell stories like the pebble which took an indirect stance. If I had to guess, I would say that the pebble stood for African Americans and the humans were White Americans. The white Americans didn’t appreciate the African Americans for the value that they could really contribute.

Sam: I see. What aboutBenito Cereno? We had to read that for class right? What is that about?

Julia: Yeah, we had to read Benito Cereno. Benito Cereno is the captain of a Spanish ship. Captain Amano boards the ship when it approaches the harbor to see what is going on. Delano immediately realizes that all of the people on the ship have been through some pretty rough times, and that this is (or at least was at some point) a slave ship. Captain Benito is not doing well, but Babo, his slave, his helping him out. Delano notices weird culture on the ship during his time there. After a while, and a couple more weird instances, Delano decides to leave. He goes to get on his small boat and Benito jump son quickly as well.

Sam: Does he leave with Delano?

Julia: Not quite… Babo attacks Benito. The rest of the story is told in different types of court documents. People have taken different stances on what Melville really meant by telling this story. Some people argue that just like the pebble story, he didn’t really want to take a stance on slavery. I don’t think this is true though, and I tend to agree with other arguments.

Sam: What are the other arguments?

Julia: Some people argue that Melville was making a point about the intelligence of African Americans. He wanted to make a statement that the slaves outsmarted the workers of the ship, and he allowed several instances to show that (the instances that made Delano uncomfortable).

Sam: Was Benito Cerenopublished in “Putnam’s Monthly”? Is that how you saw it?

Julia: Benito Cerenowas published in Putnam’s Monthly in sections.

Sam: Do you think that Benito Cerenoplayed a really big role in “Putnam’s Monthly”?

Julia: I mean it is really clear when reading through the 1855 “Putnam’s Monthly” that this was the only topic of political conversation during this time in the United States. I don’t really think that Melville was the main focus during this time or anything, but I definitely believe that this was the focus of their conversation and that he added to that a significant amount.

Sam: Where can you read Benito Cereno?

Julia: Well, there’s actually a collection at Pitt that has Benito Cereno. It’s called the Leuba Collection. Walter and Martha were husband and wife and were really into collecting different pieces of art and literature. Their collection was huge, mainly consisting of pieces within their lifetimes which was the majority of the 1900s. I actually just looked on the Pitt library website, and it says that their collection consisted of all kinds of things like magazines, books, papers, wood block art, letters from famous artists and authors, and a lot of other notable pieces of collectables. It is not just literature. It is all kinds of art! Their collection seems kind of random because it was just things that the couple was interested in. They have several copies of Putnam’s Monthly within the collection too!

Sam: Are there other things in the collection that make the Leuba’s significant?

Julia: Well, actually they have a couple pieces of art in the collection that are really cool and have a lot to do with the discussion of race. The first thing that I noticed that was really cool was that they have a bunch of calendars decorated with artwork. On one calendar was a picture of a large white man in a large hat and beard with his arms around a smaller African American man. The African American man has his hand placed on the chest of the white man. The white man is looking away from the camera while the African American man is looking directly at it. It seems as though this is Benito with his arms around Babo. It looks like here, even in this calendar, that Babo knew what is intentions were with Benito. It is chilling to look at knowing how the story would play out.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791580288/babo-and-cereno-melvilles-bentio-cereno-calendar

Sam: Were there any other calendars like that?

Julia: Yes. Also something important: this collection was created in the 1900s, long after the slavery issue was handled. During this time though, there were other issues of race occurring in the United States. The issues of race and inequality are clearly something that was important to the Leubas. They have two photograph calendars in the collection from John Steinback’s The Pearl. This story was about a poor Native American family who was treated differently from the people in their town because they were poor. When they found a large valuable pearl, everyone started treating them differently because they had wealth. I think it shows a lot that the Leubas wanted to continue their collection on race and inequality- two main points in Melville’s story.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791569803/steinbecks-the-pearl-calendar-for-september

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791560498/steinbecks-the-pearl-calendar-for-august

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791773878/leuba-cover

Sam: So the other calendars had pictures representing this inequality on them?

Julia: Yes. These calendars had weird pictures based upon the Steinback’s story.

Sam: Were there other pieces in the Leuba’s collection on race and slavery?

Julia: Yeah there were a ton!

Sam: Like what?

Julia: Well, there was a set of two books called the Anti-Slavery Papers of James Russell Lowell. Here are some pics!

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794859583/anti-slavery-1

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794864198/anti-savery-2

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794868933/anti-slavery-3

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179794872713/anti-slavery-4

Sam: James Russell Lowell? Who is that?

Julia: Lowell was a poet and critic. He worked a lot on the anti-slavery movement and used his poetic talent in his favor.

Sam: Was there anything else that I should check out?

Julia: There were a ton of interesting books in the Special Collections Department that related to the issues of slavery. One more that I thought was so interesting is the book Black Mother by Basil Davidson. This gave a detailed history about the American slave trade from the beginning to the end. I thought that the inside of the jacket gave a good overview of what it was about.

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791749163/black-mother-book-cover

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791685868/excerpt-from-black-mother

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179791600288/black-mother-title-page-the-leuba-collection

Sam: So, Julia, what do all of these things have in common?

Julia: Looking at “Putnam’s Monthly”, the Leuba collection, and our politics today, the issues of race and inequality have been able to transcend time. The authors’ stances back in the 1855 magazine are still very relevant to today’s politics. It’s really cool that the Leubas were very in tune with that when they created their collection. I think it’s also really neat that they had all different types of media to learn more about the anti-slavery and race movement. They had calendars with photographs, wood blocks, countless collections of papers and books, and so much more.

Sam: Wow that’s awesome! I’ll definitely have to check it out for the project!

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179795030828

https://jrm238.tumblr.com/post/179795046368

0 notes

Text

The Inaction of the Tolerant

Any high school graduate could tell you that the racial tension present in the United States has a long and storied history. And it’s not exactly a contested statement to say that the hardships of African Americans in this country did not end with the thirteenth amendment. All the way to modern day have those of different races and creeds faced prejudice and inequality, though things have gotten better. There are many things that have improved. However it is not that simple to say that everything was incrementally worse in the past, as there is a nebulous web of events and interactions and papers and policies that muddy up the timeline of how things were. There were those during the time of slavery that knew it was wrong. Not just thought that slavery should end, but that black people are people, and deserve the same rights as any other man.

To show a somewhat balanced view of the public’s perceptions, I’ll show varying opinions from the same publication of Putnam’s, all from within a two year span from 1853 to 1854, before Benito Cereno’s publication. The following is an excerpt from an otherwise unrelated publication. “Poor sap had fallen asleep under Mrs. Braxley’s soporific prayer, being the most sleepy-headed nigger, grandma informed us, between this and a brother of his she had sold somewhere, wherever that was.” (Virginia in a Novel Form, 258) This is from a serialized story attempting to represent Virginia in prose. This is an example of the casual racism of the time, and something I feel most are familiar with. Therefore I won’t drive home the point any further, as I’m sure everybody has read about/experienced this type of racism before.

Alternatively, there were more enlightened minds in this period. The following is a scientific paper on the physiological differences between races.

“Some philosophers have pretended to see in the lower kinds of humans, very close affinities to monkeys and orangoutangs, but we believe there has not yet been any philosopher so nearly allied to those unhappy looking individuals himself, as not to be able to tell that a man was a man at the first sight. The lowest Alforian or Guinea Negro, widely removed as he is in appearance, organism and mind, from a Shakespeare or a Washington, is still more widely removed from Chimpanzee, has still a more intimate fellowship with Shakespeare and Washington than he has with Chimpanzee. It is possible, by a stretch of the imagination, to conceive that in the lapse of ages, he might become a companion of Shakespeare or Washington, by a simple, though almost prodigious development, in degree, of the qualities that we know him to possess; but it is not possible to conceive that Chimpanzee should become the equal of a Guinea Negro, by any continuous development of what he has, and only by a change in kind. It is a matter of more or less between the Negro and the superfinest Caucasian; but between Chimpanzee and the Negro, it is a matter of life and death, or of an access of faculties that would amount to entire transmutation. In other words, a man is a man all the world over, and nowhere a monkey or a hippopotamus, and whatever his rank in the scale of human being, he is entitled to every consideration that properly pertains to man, as separated from ape, baboon, hat, or any other creature that appears to be making a wonderful effort towards his standard. - This point is admitted on all hands, and may be set aside as established.” (Is Man One or Many? J.C. Norr, M.D. and George R. Gliddon. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co. 1854)

That final line, “This point is admitted on all hands, and may be set aside as established.” seems to be a post-racial perspective in an era where men and women can still be bought and sold. The authors posit that it’s obvious how all races are essentially the same, when that was not even close to a prevailing opinion. In less than a decade the entire nation would go to war over this, yet they claim that there is no further need for discussion. There is kind intent behind this, but it is not feasible, and it is not far enough. By throwing this out there and refusing to extend the dialogue further, these authors accomplish nothing.

Even more so, one year earlier this was published. “One great effect of freedom is to fill the heart with an earnest desire that every living being should participate in its privileges. It is this which makes us feel a lively sympathy for the oppressed everywhere. But oppressions are various. There are different aspects of the picture. One individual cannot be expected to regard them all. Some among us are engrossed with attempts to benefit the heathen in distant lands; others feel a profound interest in the enslaved negro, at home; others think only of the oppressed Hungarians, while others, still, are pitying the unconscious French, or lamenting over the condition of the injured Irish, or the wretched operatives of Great Britain. The serf of Russia, the poor Indian of America, the unfortunate Pole, have also friends and honest" sympathizers" among us.” (Cuba, 3, January)

Again, sympathy isn’t enough. The tolerant and well-intentioned folk are not contributing their efforts in the best way, for by not acting any more than a few words on a page, they allow the injustices they claim to oppose to continue. Whether or not Melville intended to make claims about race through Benito Cereno is irrelevant, because even if it were, the message is too subtle. There are those who would be receptive to such a message, as shown here, but weak words do not speak consistently or loudly enough.

-Jay Zimmerman

0 notes

Text

Benito Cereno and Putnam's Monthly

Emily Gallagher

"Seguid vuestro jefe (Follow your leader)"

These were the words written in chalk beneath the figurehead of the ship the San Dominick. They are the words that appear frequently throughout Benito Cereno, a novella based upon true events. Authored by Herman Melville, it first appeared in three issues of the magazine Putnam’s Monthly in 1855, during the months October, November, and December. The most impactful and haunting usage of these words in Benito Cereno is arguably in the lengthy, last sentence:

“The body was burned to ashes; but for many days, the head, that hive of subtlety, fixed on the pole in the Plaza, met, unabashed, the gaze of the whites; and across the Plaza looked towards St. Bartholomew’s church, in whose vaults slept then, as now, the recovered bones of Aranda: and across the Rimac bridge looked towards the monastery, on Mount Agonia without; where, three months after being dismissed by the court, Benito Cereno, borne on the bier, did, indeed, follow his leader.”

-from Putnam's Monthly, vol. 6, p. 644

https://66.media.tumblr.com/0ffcdc6f5cc630d3693e374210fde701/tumblr_phqe8feclX1xljixdo1_400.jpg

(Illus. engraved on wood by Garrick Palmer for the Imprint Society edition of Benito Cereno, 1972)

So what does this all mean? Which leader did Benito follow? These are the questions that immediately came to my mind when I finished reading the last line of Benito Cereno. I figured Herman Melville emphasized “follow your leader” for a reason, one that ultimately dealt with the issue of slavery in the US during the year it was published, 1855. In order to understand the conclusion I came to, one must know the basic details of the novella.

Benito Cereno is told from the perspective of Captain Delano, who comes across a disheveled ship named the San Dominick, with many African slaves aboard. He meets the captain, a Spaniard named Don Benito Cereno, along with his seemingly faithful slave Babo. Benito tells Delano that their dire state was caused by storms and an outbreak of disease, so Delano offers his help. The great twist is that the slaves aboard the ship had revolted and taken over, with Babo as their leader. Babo killed his old master and Benito’s friend, Alexandro Aranda, and had Benito under his control the entire time. At the end of the story, Babo is captured and sentenced to death. As stated in the passage above, his head is mounted on a pole, and Benito Cereno dies soon after as well.

But why did Melville say Benito “[followed] his leader”? Was he following his friend Aranda in death, or the slave Babo who had succeeded in controlling him?