Text

While I'm on the topic of beginners learning a language, common pitfalls beginners fall into, and and how to get out:

Starting a new learning resource (for beginners) for a few weeks/months, then quitting and starting a new learning resource (for beginners), getting stuck in a cycle of relearning the same material multiple times - if this is you, the solution is to STICK with 1 resource until you've completed it. (Or to stick with 1-4 resources if you are using different resources for reading, listening, speaking, writing etc.). If you find yourself jumping between apps, or resources, go ahead and keep jumping around until you find something you really like, so you can find that resource you'll stick to for months/a year. Basically, keep it simple, and stick with something.

No idea where to start or what to study first - if this is you, the solution is to pick a Structured Resource, so you can let the resource tell you what to do. Traditional classes in schools, MOOCs like Coursera, Textbooks labelled by 'level', Free Resources that have clear directions on what to do for how long. If you choose an app or an anki deck (something less structured), then make a study plan to do it a decent amount of time daily (more than 15 minutes) it until you complete it. If you struggle to judge what is useful and what's not, a Structured Resource that teaches basic grammar and 1000-3000 words, in listening and reading exercises (and optionally speaking and writing exercises/practice), is going to be the easiest thing to use.

Not putting in enough daily study time on average - if this is you, consider trying to make time for 1 hour or more of time engaging with the language daily. At least 30 minutes. 2+ hours if you're ambitious. Suggestions: consider using audio-only learning materials such as learner podcasts with other-language explanations (Glossika, Coffee Break Language, LanguagePod101/Innovative Language courses, Pimsleur, Paul Noble, audio sentence flashcards like japaneseaudiolessons.com), so you can study while doing chores, while getting ready, while commuting/traveling, while exercising, and see if you can fit in 30 minutes or more per day. Once you are no longer a beginner, it will be easier to make time for the language in your daily life, as you'll be able to engage with the language during more of your everyday hobbies. The beginning stage is the hardest, you got this.

Not seeing progress as fast as you wish - if this is you, the solution is increase your daily study time. I know, it sucks and is obvious. That's about the only way to see more progress in less days.

Losing motivation because you aren't seeing noticeable progress - if this is you, pick a short term monthly (or 3 month) goal, to be able to do something specific in the language. It could be any goal. Examples: read a Graded Reader story, finish X number of learner podcast episodes, read X chapters of a novel or comic (looking up words if needed), complete X chapters of textbook, go through X number of dialogues from class, watch a movie in the language (while looking words up as needed), watch a youtube video in the language (while looking words up as needed), read a short fanfiction in the language (while looking up words if needed), be able to speak a summary of your hobbies aloud, be able to write a diary entry about your day. These short term goals will give you something to achieve, will focus your studies on a particular thing you wish to do in the language, and will give you results you can see/measure for your efforts. These short term goals are also useful for if you like changing what you do every few months, and changing what you focus on improving - this is generally what I do, to keep interest and motivation up.

No idea if you've learned enough to move onto intermediate study resources and practice understanding the language - if this is you, a 'Grammar Guide Summary' and a 1000-3000 'Common Words List', both ideally with example sentences, will be your best friends. You can look these kinds of resources up online free, or if you have been studying with a Structured Resource then you should be able to quickly glance at that resource and see how much grammar and how many words it taught you (that information should be in the opening explanation of how to use the resource, or in the explanations and word lists of each chapter, or if it's an anki deck it will be the information on all the cards/the information on the deck's community page). Look up a "Grammar Guide Summary" and a 1000-3000 "Common Words List" and if most of the stuff on those resources looks familiar, then you're ready to start PRACTICING understanding the language, and you're ready to MOVE ON TO INTERMEDIATE RESOURCES. Congrats, you're no longer a beginner!

Not sure how to move into practicing what you are learning - if this is you, Graded Readers (containing a unique word count lower than the amount of vocabulary you've studied), Comprehensible Input Lessons (on youtube), and Learner Podcasts for Beginners to Lower Intermediate learners will be easiest for you to practice with. Also, if using a Structured Resource (like a class or textbook), any exercises it contains for practicing (writing sentences using the grammar and words taught that week, speaking the same sentences, listening to audio and answering questions about what it talked about, shadowing the audio - repeating what you hear as close to how it sounds, reading the text practice provided in the chapter/class).

Not sure how to start watching shows and reading novels - if this is you, you're either at the Upper Beginner or a Lower Intermediate stage, know a lot of basic grammar and 1000-3000 common words. My first suggestion is to go back to the previous point for practice until you feel comfortable. Once you wish to, watch stuff and read stuff made for native speakers - get yourself a good translation app (or website) for the language you're learning, and start watching stuff and reading stuff you want to. Look up any unknown words or grammar that seems key to understanding the main idea, and look up anything else you're curious about. Watch and read things you've seen before in another language, because the prior context of knowing the plot already will make it more understandable. Watch things with a lot of visual cues as to what's going on - cartoons for toddlers, cartoons for kids, action stuff, daily life stories, comics. Read stuff about topics you are already familiar with, such as news or history or science where you already know the topic and recognize some words. Congrats, you have hit the long intermediate stage!

#i really need to do what you’ve done and lock in on listening training#resource#langblr#mandarinblr#mandarin#language learning

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Cherry Magic Mandarin audio drama for anyone who's interested.

I just checked if I could understand it now, and I do wooh >o<)/

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

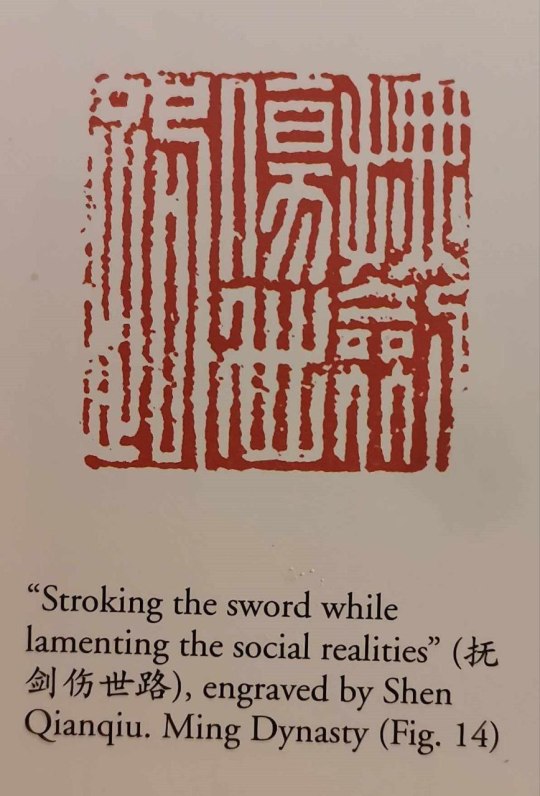

Who up stroking they sword while lamenting the social realities.

36K notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm a broken record about this, but I really recommend reading Heavenly Path's Comrpehensive Reading Guide, and then checking out their webnovel recommendations for Newcomers.

Even if you only take some tips away from that guide, something in it will be of some use to you. Their guide mentions Pleco, Readibu, a ton of free Graded Reader resources, when to start trying to read stories. Just tons of useful stuff.

For people who are already reading, and struggling to find easier, or slightly more challening, reading material, their general recommendations pages are extremely useful.

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

The legend of Qu Yuan (c. 340 – 278 BCE), the poet of tristia and itinera, and how the custom of zongzi eating and dragon boat racing on Duanwu have come to be associated with his sad tale.

On the fifth day of the fifth lunar month—端午 Duanwu—we commemorate the death of the poet-minister Qu Yuan 屈原.

Exiled from the kingdom of Chu for his fierce opposition to Qin (which did indeed demolish all, in its imperial ambition), he drowned himself in the Miluo River.

Legend has it that fishing boats set out looking for the much-beloved Qu Yuan. When he could not be found, food was thrown into the river to prevent fish from consuming his corpse.

Hence Duanwu is also known as the Dragon Boat Festival & sticky rice packets (zongzi) are eaten.

'The Songs of Chu' 楚辭, attributed to Qu Yuan (but more likely by multiple authors) are densively allusive poetic laments dating from the 3rd c BCE collapse of the Chu kingdom.

To quote David Hawkes, Chuci 楚辭are the poetry of tristia and itineria —the laments of exile.

Qu Yuan's 'Songs of Chu' are the laments of one born to "an age foul and murky"

Sighs come from me often

the heart swells within

sad that I and these times

never will be matched.

As it is then, as it is now.

Another version:

Duanwu 端午 marks the beginning of summer heat and pestilence, and the in southern China and throughout southeast Asia it was an occasion to fumigate the household and eat restorative foods wrapped in naturally antiseptic leaves.

The legend of Qu Yuan - the loyal minister in exile, wandering the Southland - then, was a Han Confucian repackaging of local folk customs.

One stayed as low profile as possible to steer clear of all the miasmic, pestilential forces —hence the need for mugwort and spells...

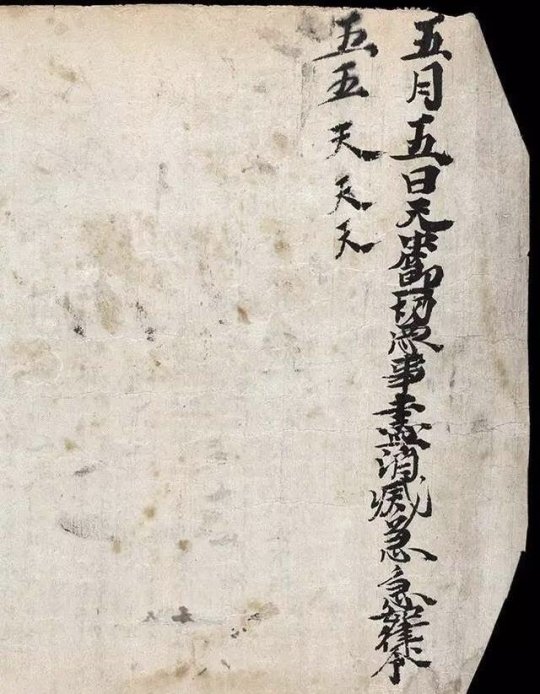

「五月五日天中節一切惡事盡消滅 急急如律令」

FIFTH DAY OF FIFTH LUNAR MONTH: ALL THINGS WICKED AND PESTILENT TO BE VANQUISHED INSTANTLY WITH THIS SPELL

We could *really* do with such a 急急如律令 these days.

[Dunhuang fragment British library S.799]

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Support and uplift chinese queer creators and their fight. There is hope for an even better tomorrow.

text version

5K notes

·

View notes

Note

sorry to bother you, but here with a question:

what does 給我 in phrases like 給我沖, 給我滾, 給我回來 , and 給我閉嘴 translate to in english or atleast, how is it that 給我 is used alot for the start of these sorts of phrases that seem very rude or atleast annoyed/emotionally charged 😅?

给 means "to give" and alone 给我 would be "give [it to] me", however in the context of the examples you gave, it becomes "for me", e.g, 给我冲, would be "charge it for me", if the context is filling a card with money or charging a battery, etc, and "charge for me" if the context—more likely, given your other phrases—is "Charge forth!".

However, for English translation, while it can be tempting to try and get as close to the Chinese as possible, doing a word for word translation is also clunky and will give you what I'd call a "translation accent" (I think I was guilty of this for a while in my early days of running this blog). It's better to leave off the 给我 and try to convey the emotion in another way, because yes, the 给我 in a phrase can often make it emotionally charged, as it places emphasis. That emotion can be annoyance or amusement—it just depends. For translation, it helps if there's vocal delivery context but even if not, you should be able to determine the emotional degree of the phrase based on what else is happening in the convo.

From your examples:

Chinese → Clunky literal translation → smoother translation options

给我冲 → Charge for me → Charge! / Rush forth! / Go! / Get them! 给我滚 → Roll for me → Get lost! / Take a hike! / Fuck off! 给我回来 → Come back for me → You get back here! / Come back here! 给我闭嘴 → Close your mouth for me → Shut up! / Zip it!

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

worst thing about tumblr is the lack of chinese variety show fandom. yeah yeah c-dramas and actors but what about the mango tv stuff. what about detective academy. who can i talk to about my massive crush on guo wentao and pu yixing and qi sijun and zhou junwei and

251 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Wishing you the wishes that matter" (by Cheeming Boey on Instagram)

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alright, sound off! WHO is learning Classical Chinese?

I want to find friends to study with and complain to!!!

I have gotten back into it in a more serious capacity after a few years of nonsense, and am continuing (sigh) to work my way through Introduction to Literary Chinese by Michael A. Fuller.

Please reblog for greater sample size! Beginners or 古文大师 all please reply!

I know some people in HK, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, China, greater Sinosphere/diaspora might be also doing it or have done it as a school subject, and I'd love to hear from you guys too :D

#studied it for a bit in college and have had some experience working with it since then but wouldn’t say I’m super well versed#also Chinese through poetry is the main book I used#obviously it’s a poetic lens but does focus on more classical language#I think it’s a good introduction!

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

The known-ish words of intermediate Chinese, or: What does it mean to know a word?

We all have this intuition, especially in languages like Chinese, that there are words we 'kind of know'. These are the known-ish words. In the case of Chinese, most people would recognise at least three axes:

1) Do I know the meaning? 2) Do I know the pronunciation? 3) Do I know how to handwrite it?

You might answer yes to some, but no to others. Voila! You know the word - ish.

And then you can also add the dimension of passive and active knowledge:

1) Do I recognise this word passively? 2) Can I use this word actively?

Great. Even more ways of kind of but not really knowing a word. But that's far from all. There's also the different domains of listening and reading, writing and speaking.

So passively, that looks like:

1) Do I know the meaning when listening? 2) Do I know the meaning when reading? 3) Do I know the pronunciation when reading?

Once we add in the active dimension, it all starts to get a bit more complicated. This is far from an exhaustive list, but consider the follows ways you could define 'knowing' a word:

1) I can read the word out loud (but I don't know what it means, and I can't use it in a sentence) 2) I know what the word means, and I can use it in a sentence (but I can't handwrite it) 3) I can use the word in a spoken sentence (but I don't know how to type it, or which character it uses) 4) I can recognise the word when reading (but don't know how to read it out loud, and can only guess at the meaning) 5) I can use the word in a written sentence (but not a spoken sentence) 6) I can type the word and recognise the word (but I don't know how to handwrite it) 7) …

Okay. What else?

Chinese is a compounding language.

Have you ever had the experience that you can't recognise a character individually, but as soon as you see it in a familiar compound, you know what it means? So:

1) I can recognise the word individually 2) I can recognise the word as part of a compound 3) I can recognise the word as part of an unfamiliar compound

Chinese is also a language with a long and storied tradition of writing in Classical Chinese as a literary language and a lingua franca across the whole of East Asia - even two hundred years ago, people were writing in Literary Chinese. 'Mandarin' as a concept did not exist.

So often the meanings of familiar characters can be quite different in formal language or chengyu in the modern language, which uses more classical / literary structures and grammar.

Take, for example, the character 次. The first layer of meaning in modern Chinese - the most foundational layer - is its meaning as time, like 'I have been to Ghana two times'.

But its second layer of meaning is secondary, or next best, or just next. For example:

1) 次货 - substandard goods 2) 次子 - second son 3) 次年 - next year

And so on. Many common words have this kind of polysemy.

So we can add another dimension:

1) I recognise this word's common meanings 2) I can use this word's common meanings 3) I recognise this word's less common meanings 4) I can use this word's less common meanings

Add in the reading and listening dimensions, and things get even messier. I am familiar enough with this basic secondary meaning of 次 to fairly quickly be able to understand that it means 'next' or 'second' rather than 'time' if I see it in a written unfamiliar compound or chengyu. But I am most definitely not quick enough to do that every single time whilst listening to the news, for example!

And what about pronunciation? Once you know a fair amount of Chinese characters, you can often guess the pronunciation of new or unfamiliar characters. How?

Because of phonetic components.

For example:

请

清

情

Notice how these all have the same component on the right? This tells us that these characters belong to the largest group of Chinese characters, phonetic-semantic characters. That is - some part of the character gives a clue to the meaning, and some part gives a clue to the pronunciation. In this case, we know they are all pronounced some variety of qing.

But it isn't always that easy. Some phonetic components tell you the tone and pronunciation - some tell you the pronunciation, but not the tone (like qing above). Some phonetic components, to go even further, are only really decipherable if you have a particular interest in phonology or historical linguistics, or learn the patterns. Consider:

脸 - lian3 (face)

险 - xian3 (dangerous)

验 - yan4 (test)

剑 - jian4 (sword)

签 - qian1 (to sign)

捡 - jian3 (to pick up)

There are far more. If you look down the whole list on Pleco, they all show a similar pattern of variation. You can see some patterns, but also numerous exceptions - most end in the -ian final, except for those that are yan of various tones. All begin with l, x, y, j, q. Most are pronounced jian3, but that is far from a rule.

All this to say - you can see a character, and know vaguely how it is pronounced. If I know that a character is pronounced qing definitely, 100%, but don't know the tone - does that mean I know the pronunciation? Or would you only say that knowing it 100% means knowing it? And in that case - how can you account for the fact that learning a character when you already know 90% of the pronunciation is significantly easier than not knowing it at all?

Let me add just a few more scenarios. Bear with me!

1) A character has more than one way to be pronounced. For this word, you read it incorrectly (but you usually know it). 2) A character has more than one tone. Some people pronounce it always with one tone, and some alternate between the two pronunciations. You only knew it with one - but you're half right? 3) You make the same mistake that a native speaker would make with tone or pronunciation of a rarer character.

In some way, these are all more knowing than not knowing anything at all.

And none of this is even taking into account different writing systems, traditional and simplified.

Here are some more scenarios:

I recognise the character in traditional (but not simplified)

I can type the character in both, but I can only hand-write in simplified

I know the Taiwanese pronunciation, but not the Chinese

etc

And of course Chinese characters are used across multiple different languages.

So you could conceivably have these kinds of situations:

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese and Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Cantonese, and the meaning in Mandarin

I know the pronunciation and meaning in Mandarin and recognise it in Cantonese, but know it means something different

I know the pronunciation in Mandarin, but don't know what the whole word actually means in Mongolian (Chinese characters used to transliterate Mongolian words)

Plus there's handwriting and calligraphy!

Personally, I can't read a lot of calligraphy and have accepted my happy illiteracy in many styles. All Chinese learners and heritage speakers know the feeling of sitting in a Chinese restaurant or museum and having a well-meaning friend say, 'Oooo, what does that say?' It's depressing! So let's add some more nuances to our known-ish characters:

I can read this character in common fonts

I can read this character in less common fonts

I can read this character when handwritten

I can read this character when handwritten quickly / by a child / by a doctor

I can read this character in grass script / seal script / etc

Then there's the question of naturalness.

I frequently add words to my Anki decks that I would be able to understand, no question, if I were reading or listening - but I probably wouldn't have thought to say it in that way. So:

I recognise this word, and would have said it exactly like this

I recognise this word, but would never have thought to say it like this

I can use this word, but didn't know you could use it in such a metaphorical way

I can use this word in a metaphorical way, but didn't realise it corresponded so closely to English / was so different from English in its meaning

And finally there's the simple question of memory.

I know I've seen this word before, but I can't remember it right now and I want to drown myself pathetically in the vast uncaring sea

I know I used to be able to use this word actively, but now can only use it passively

I can still type it, but have forgotten how to handwrite it

I can still use it in writing, but I wouldn't be able to use it in speaking

I can recognise it in set expressions, but wouldn't remember how to use it on its own

I can remember the simplified character, but not the traditional

…

So how many ways do you know a word?

I often feel embarrassed to post my vocabulary lists, because I feel that people will be surprised that I don't 'know' certain more foundational words. I think they will be confused as to why I have very 'advanced' vocabulary alongside 'simple' vocabulary. I feel a lot of pressure to be 'advanced' because of the amount of followers I have, but there's a lot of more basic characters I still don't fully know in a holistic way.

And the truth is that all of those characters and words are in Anki for different reasons. I might have a vocab list that looks like this:

略

松懈

星光

缕缕

薄雾

博览

I don't know any of these words in exactly the same dimensions as I know the others! Let's look at my reasons for including each in detail.

略 - lve4 - slightly. I have this word here because although I know it well in set expressions like 略有耳闻 'have heard a little about',略有受损 'has suffered slight losses' etc, I wouldn't remember the pronunciation if I saw it alone or with another verb apart from 有. I would still know the meaning - but I wouldn't remember how to pronounce it. So even though I 'know' this word, it's still there in Anki.

松懈 - song1xie4 - to relax, lax, slacken. This is a rare example of a totally 'new' word - most of my Anki words aren't. I know 松 already well, but have never seen the character 懈 before: I didn't know its meaning, or pronunciation.

星光 - xing1guang1 - starlight. I know both characters, pronunciation and meaning, and I can easily understand this word. I just never would have thought to say it so simply. I want to use it actively, so I put it in Anki.

缕缕 - lv3lv3 - fine and continuous (i.e. rain, drizzle). I know 缕 already on its own as a measure word for sunlight, thin hair, gossamer, mist, smoke, fine threads etc - I often forget its pronunciation, but I know its meaning reliably when reading. But together the compound 缕缕's meaning isn't quite extricable from just knowing 缕, so I put it in here.

薄雾 - bo2wu4 - mist, fog. I know 雾 well, but hadn't come across 薄 before (or wasn't sure if I had or not). This is an example where I knew its pronunciation, because of phonetic components, but I didn't know the meaning of the character.

博览 - bo2lan3 - to read widely. I know this word very well. So why is this in there? Literally just because I remembered the pronunciation and meaning of 博览, and when I was racking my brains trying to see if I knew the 薄 in 薄雾, I thought it might be the same character. I looked it up, and it wasn't. So even though I know the word, the meaning and the pronunciation, I had to put it in - because I didn't remember which character was used for the bo2.

When you acknowledge all of the different ways of knowing a Chinese character, it makes sense that your learning after the beginning level is going to be full predominantly of known-ish words.

Accept this! Form your own relationship to it! For me, a huge part in my motivation to return to learning Chinese after a year-long break was just to accept that I was likely never going to 'fully know' most of the characters and words that I partially know.

But that's okay. Think about your native language.

If your native language is English or you speak it very well, consider a word like monadic. Could you say you knew this word? Fully knew it? Like me (I learnt this word in the context of Linguistics yesterday), you might have an idea that it has something to do with one - mono, monorail, monotropism, monologue, monolithic etc. But would you be able to use it in a sentence? Would you be able to explain it to a child?

Or let's say you're learning two new English words: lithology and dreich. (The latter is a Scots word, not English - you would hear it in Scotland frequently.) Neither word you completely know. Which one is going to take you longer to learn?

It's likely going to be lithology. You can form connections with words like monolith or paleothic or maybe even lithium - even if you couldn't say for sure what the Greek element lith means, you're passingly familiar with other words containing it. You also know -ology, and you know how to pronounce the word. If you learn that it means 'the study of rocks', that is probably quite easy to remember.

Dreich, on the other hand - what is there to tell you a) how to pronounce this, or b) that it means 'dreary' or 'bleak', as in, dreary weather? You can't form any connections with similar words at all, and the [x] sound at the end - like in German or Hebrew - might be unexpected to hear if you don't live in Scotland.

That's what Chinese is like in the beginning. All words are like dreich. But the more you learn, the more words begin to be like monadic or lithology.

Learning ten new words a day like dreich would be very difficult. But if you've seen monadic a few times over the last few months, know vaguely when to use it, know how to pronounce it - it's not so hard to imagine that you could learn ten of those a day.

I find all these known-ish words very overwhelming.

And I also find recognising the potential for overwhelm in the Chinese language - because of its unique properties - very helpful in letting me feel less guilty about my current known-ish words. I do know them - ish.

But when I finally get around to properly learning them, all that ish-ness will make them that much easier to remember!

Now I try not to stress out about these types of words. I recognise that, in many ways, they are inevitable. Unless you're a poet who composes out of thin air, you're not going to ever say a literary word for emerald green as frequently as you'll read it in descriptive passages in novels.

It's natural to know certain words in a spiky profile: to know them very well in some ways, but not at all in other ways.

The more you read, the more pronounced this can become.

So here's what I've learnt, and here's the message of all this big, long, rambling post:

Putting 'easy' words that you feel you should know into Anki isn't regressing. It's adding another dimension of knowledge to your understanding of the word. You shouldn't feel ashamed or frustrated when you find you don't know one aspect of an otherwise 'easy' word. I'm still trying to learn this.

Because -

Having lots of known-ish words is not a unique failing on your part. It's a reflection of Chinese as a language and its unique complexity -

And it's part of what makes it so uniquely beautiful.

Have a nice day, everyone. meichenxi out!

293 notes

·

View notes

Text

Responding to common douyin hooks

English added by me :)

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

hey can we talk. can we stop it with the white savior pinkwashing queer paternalism that white libs always seems to hold when talking about queer people/gender-nonconforming people from countries where gay rights isn’t a legislated reality (i.e. often developing countries/countries where the majority ethnicity is non-white).

you haven’t been on weibo, you haven’t ever been to China. you haven’t walked the streets of chengdu which is the unofficial queer capital in the country, you don’t know what slangs and jokes we use to talk about queerness.

you read whatever your war crime aiding and abetting news sources spoonfeed you because you never went out of your way to befriend Chinese people in real life, you accept whatever reality is easiest for you to stomach—that Chinese people, well, “the government and the mainstream social media” at least, are ontologically evil and are intolerant to a fault; that Chinese people are so different than you (who are so liberal and tolerant and queer and punk) that these “special few Chinese people who are queer” need YOUR approval and YOUR protection and YOUR help.

I’ve spent a good portion of my life living in China, I have family there. I have queer friends there. My parents had colleagues and friends who are officially or unofficially out at work. I met my first butch-femme lesbian couple in China. I met my first trans man uncle in China. A large part of my middle school friend group turned out to be queer and have found people who they care about and who care and protect them in turn.

I only pity your willfully ignorant way of living. you see Chinese people as a sexless monolith, you see Chinese people in any position of power as a threat to your “democracy” aka violent imperialism disguised under a neoliberal facade. give me a break.

15K notes

·

View notes

Note

Hey so you seem pretty knowledgeable about learning languages! I’ve been looking for a way to learn kanji but I don’t have a huge interest in learning the languages that use it if that makes sense? Like I want to be able to read a sign and be able to tell what it says but I don’t need to be able to pronounce it. Is there a way to do that? Do you have any tips?

I've been thinking about how to respond to this because it is an interesting question for sure. I assume you mean you want to learn Chinese characters that are used in languages like Mandarin and Japanese. Mainland China uses simplified characters, Taiwan uses traditional characters, and Japanese kanji is very similar to traditional characters, but also it's own thing.

For learning them to read street signs (assuming very basic here like Stop/Go/Park/Bank) I think while there's a lot of overlap, they are separate languages. Japanese uses Chinese characters (kanji), but they don't use them as often and for the same things. Here are stop signs in China and Japan.

So learning characters to know signs in different places just doesn't work out in practice. You gotta know where you're going and what language is spoken there. I guess I do wonder why not just learn the pronunciation? If you're going to learn something you might as well put in the 10% extra effort to add the pronunciation (even if it's not ~native-like~!)

Sorry for not being able to help you out, but maybe this helps you find a more achievable goal?

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

I’ve wanted to learn mandarin for a while but the language feels really overwhelming. do you have any absolute beginner tips? also is learning to write/read pinyin a good starting point or should that wait till later?

Hi! Sorry for getting back a little late, I've been a bit busy!

I totally get how it feels really overwhelming because it genuinely can be at times! If you want to start, you don't start with learning characters and vocab, but learning pinyin and tones. Training your pronunciation and listening skills is so fundamental, so it is always the first thing anyone learning this language learns—even native speakers! Pinyin uses the alphabet and tone markers to express the sounds of the language. The way they are pronounced can be different than what you may be used to, so remember that it is just a guide and not a totally phonetic equivalent.

I really recommend this video series since it's free and very comprehensive. It also links to their pinyin chart which will give you every single pronunciation you could ever hear. Chinese pronunciation is very consistent, so you can learn every possible combination of sounds relatively easily! After you finish that, then move on to learning vocabulary and grammar like any other language.

If you specifically want to learn Taiwanese Mandarin, they do not use pinyin, but zhuyin. It works the same way and teaches the same sounds, but does not use the alphabet, but it's own system of symbols. I'd recommend learning both pinyin and zhuyin in that case. Here is a video series on Zhuyin!

It can be a lot to take in at the beginning, but you've got this!

加油!

43 notes

·

View notes