I'll be a little ray of sunshine if it fuckin' kills me. Now don't be shy. Introduce yourself. We're best friends now, no backing out. || User 20+ ||

Don't wanna be here? Send us removal request.

Photo

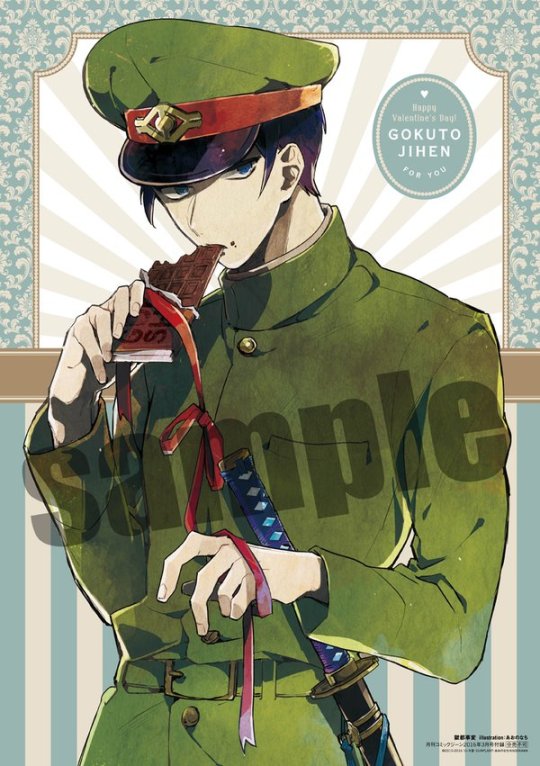

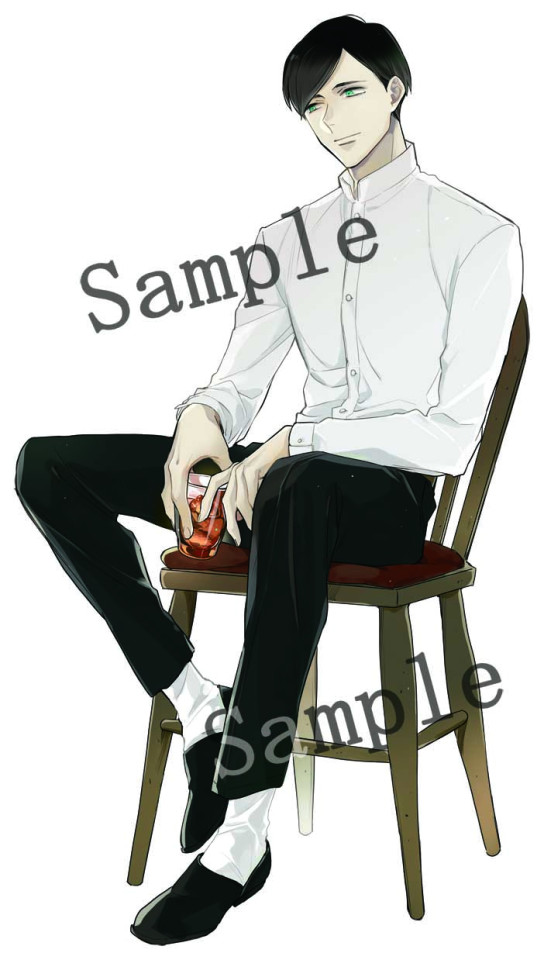

Sooo i found this from animate and other japanese websites. ( altho i dont remember it :‘3 / )

If I’m not mistaken these are from magazines or something limited edition. We can tell that how they revealed the underworld escorts looking casual without their uniforms on.

Please correct me if i’m wrong and tell me anything you know about this special illustrations! Thanks!

120 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(source) (as seen on Tumblr)

Sorry for adding this so randomly, but it was really for personal reference. I translated the floor plan of the Gokuto Jihen Manor (First Floor) into English for anyone who was curious, with some minor notes.

“Bathroom” isn’t quite right… it’s more like “toilet” because that’s really all there is in there (and a sink). I’m pretty sure the escorts use the Shower/Bath Room to actually wash up.

“Washitsu”, the three rooms in the north, are literally “Japanese Style Rooms”. They probably have tatami flooring and fusuma doors.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

【お仕事情報】獄都新聞連載開始のお知らせ

5月12日(木)より、コミックジーンにてリンネ堂様 (監修, 原作) SUNPLANT様 (原作協力) の「獄都新聞」の漫画を担当させて頂く事になりました!!

原作:リンネ堂さまのサイト→(http://rinnedou.moryou.com/index.html)

公式ツイッター→(https://twitter.com/gokutojihen)

公式サイト(http://gokutojihen.com/index.html)

今年2月に発売されました「獄都事変コミックアンソロジー-閃-」でも参加させて頂きましたが、まさか獄都新聞の連載漫画を描かせて頂けるとは夢にも思っておりませんでした……!!!本当に……!!!!!!

獄都事変に登場するキャラクター達は一人一人の個性が強く、そんなみんなが集まってどたばたとコミカルに繰り広げられる展開は読んでいても描いていてもとても楽しいです!

初めての連載漫画に、制作においてご協力頂いてるたくさんの編集の方々や原作者さまとの連携で大変非常に絶大に緊張しておりますが、それに負けないくらいの誠心誠意を込めて永く永く描き続けてまいりたいと思います!

是非是非書店でお見かけした際は何卒よろしくお願いいたしますー!

35 notes

·

View notes

Photo

((from twitter)) hes tOO HANDSOME I CANT

206 notes

·

View notes

Photo

They did a photoshoot of Hirahara and Matsumoto’s Adventure to the Living World.… this is getting out of hand

45 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A limited-time event about Gokuto Jihen will occur in some GraffArtSHOP stores from Friday 13th to Sunday 29th of December 2019 ! A few products using these illustrations will be sold. Mail orders will open after the events with what will be left.

(source : Twitter) (art : Aononachi)

96 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(from here and other duplicated tweets)

transparent escorts for your sidebar or something

360 notes

·

View notes

Text

“I’ll never talk” ok that’s cool. didn’t really expect you to. I’m not gonna torture you for information—I have an elaborate espionage network for that. everyone knows torture is an unreliable means of extracting information and anything obtained from it is not to be trusted. I’m not an idiot. I’ve read all the torture science. if there’s one thing I can’t stand it’s the foolish notion that torture serves a practical purpose. no, my torture dungeon exists for good, clean fun. it’s all about the love of the game. strap ’em to the rack, boys!

11K notes

·

View notes

Text

googling shit like "why do i feel bad after hanging out with my friends" and all of the answers are either "you need better friends" (i don't; my friends are wonderful) or "your social battery is drained, you need to rest and regain your energy levels" (i don't; i've got tons of energy, it's just manifesting as over-the-top neurotic mania). why is this even happening. it's like some stupid toll i have to pay as a punishment for enjoying myself too much

111K notes

·

View notes

Note

Where do you fall on the "killing vs. not killing bad guys" argument? I know the debate is complicated and there's a lot of various factors for and against either side, so I wanna hear your take on things.

An intensely complicated subject that tends to get oversimplified on both sides of the equation. I generally don't like to take a "side" on this because I feel like the idea of there being "sides" on killing misses the point.

Unless you're talking about cold-blooded execution of a subdued foe, killing generally isn't a choice you get to make. It's a consequence of the choice you already made to use violence.

While arguments about killing villains exist beyond superhero comics, this is a particular way that they tend to happen in superhero media. Superhero stories depict their heroes as, effectively, SWAT teams. The Green Goblin is about to blow up Newark, so Spider-Man breaks in and smashes his face against a brick wall until he passes out.

Part of the fantasy is the idea that nonlethal violence is easy and reliable. After Spider-Man reduces the Green Goblin's HP to 0, a Windows menu pops up and says "Would you like to finish him?" Spider-Man boldly clicks "No" after every fight like the hero he is.

It allows fans to enjoy brutal takedowns of bad guys without having to reckon with the reality that when Batman brought an entire floor down on top of that guy's head, he probably didn't wake up in a hospital bed. Batman can throw a guy off a third story balcony and watch his knees crack as he hits the ground and the story assures you that he's fine. He'll just need a little stay in the hospital.

But realistically speaking, all of these guys would have body counts. Not because they were aggressively trying to murder, but because you don't really get the choice. It is extremely easy to kill someone and surprisingly difficult to nonlethally incapacitate them. The line between how much blunt-force cranial trauma will knock someone unconscious versus how much will kill them is extremely blurry and it moves.

There are less lethal ways of incapacitating someone than others. Obviously, tasing someone has a lower mortality rate than shooting them with bullets. But the only surefire way to uphold a Code of No-Killing is to not use violence as your problem-solving tool in the first place. And there's not a lot of de-escalation training going around the Avengers Mansion.

So it always just feels kind of self-delusional when superheroes brag about not killing people but their primary mode of problem-solving is to shoot a guy in the face with an exploding arrow or something. You're gonna kill people if you're Batmanning. Sorry, that's just the reality of violence. When you throw a guy off a roof, you don't get to choose what physics is going to do to that sack of meat and bone as it hits the ground.

Now, on the opposite end of the spectrum, should superheroes kill people on purpose? Uh. No. I don't want cops extrajudicially murdering whoever they don't like, and I don't want Batman to do it either. Due process exists for a reason.

Superheroes should not try to kill people. But they are going to kill people sometimes, because their hammer is violence and their stories are just excuses to pit them against nails.

"But the Joker always breaks out of prison." Yeah, but he also always comes back to life. If you can nitpick about genre conventions then I can too. Hell, often times you can't even redeem a villain without the next writer unwriting it and making them a bad guy again. At a metafictional level, there is rarely any way to truly do away with a popular villain.

But. Y'know. Let's talk about heroes who aren't fucking copaganda. In the broader fictional sense, should stories end with the hero killing the villain or shouldn't they?

This, again, has no simple Yes or No answer. It depends heavily on the themes being explored and what the villain is meant to represent.

We need to talk about the "demise" of the villain, which can be a literal death or it can be many other things. The primary function of the villain is to be wrong about something. To oppose the hero, who is right about something.

The villain holds bad ideas, bad beliefs, bad ideology. The hero may start out holding good ideas, or they may be something that the hero comes to over the course of the story. But by the time these two meet in the third act climax, they are meant to embody the two faces of the story's central thesis. Regarding whatever this story is trying to talk about, the hero is right and the villain is wrong.

Whatever form it takes, whether literal death or not, the demise of the villain is the final statement on their incorrect or even toxic beliefs. Which often does take the form of literal death because it's easy to write a comeuppance that way.

Luke Skywalker believes that there is love in his father's heart for him, and Emperor Palpatine is confident that Anakin is truly lost. But Luke's love for his family wins out and destroys Palpatine.

Scar is selfish, cowardly, and disloyal. Simba returns out of a sense of responsibility and loyalty to his people, coming clean to them and accepting his place among them. Scar tries to sell out the hyenas to save his own skin, as well as stabbing Simba in the back. For his treachery, the hyenas rip him to pieces; He is devoured by the very loyalties that he selfishly betrayed.

Obadiah Stane, the embodiment of war profiteering and the military-industrial complex, is literally consumed by the clean energy project that Tony wants to move the company towards instead.

Sauron underestimates the power of the small and meager folk, and believes wholeheartedly in Great Men of History. And so when Great Man Aragorn marches to his gates, he allows himself to become convinced that this is his true nemesis, his true rival, the threat he must face. This is the glorious battle that will decide the fate of Middle-Earth. And so he turns his eye away from the common folk that will be his undoing.

The villain's flaws, their toxic ideology, the things that make them the villain, are what their demise is supposed to be about. They can be consumed by their failings or undone by the hero's virtues, but either way, in a well-executed demise, a closing statement on the story's thesis is made.

But a well-executed demise doesn't necessarily have to be fatal, either. Like I've said, it can be things other than a literal demise. Sometimes it absolutely should.

In Civil War, Zemo is driven by an obsession for revenge. His homicidal retaliatory bloodthirst is a toxin that he infects both T'Challa and Tony with over the course of the story. Tony succumbs and has to be defeated with force, though Steve still demonstrates his strength of character by sparing Tony's life in the end even when the madness of the battle threatens to grip him too.

But it's T'Challa who delivers Zemo's demise. Not by killing him, but by making the choice to rise above vengeance. T'Challa breaks the shackles of Zemo's infectious vengeance and chooses mercy. And it's in this moment that Zemo's feelings, his cruelty, are opposed and vanquished by T'Challa's heroic virtue.

Firelord Ozai believes in the Social Darwinist ideology of Might Makes Right. He leads a culture where disputes are settled with deathmatches and believes it is his right to blanket the world in fire because he has the power to do so, and no one can stop him. Aang, by contrast, is a pacifist at heart because those are the values he was raised in; Values of a culture that Ozai exterminated, whose very last vestiges exist only in Aang's heart.

Ozai would kill Ozai and Azula, who often gets left out of this conversation. Because theirs is a culture where righteousness stands hand-in-hand with brute strength. Where who is right is decided by who is left standing when the dust settles, and who is a pile of ash. Aang defeats Ozai; By Ozai's belief system, Aang is stronger thus Aang is righteous and it is his Conqueror's Right to execute Ozai where he stands.

But Aang doesn't just beat Ozai; He rejects Ozai's way of life. He renounces the belief system of the imperialist colonizer and holds true to the belief system of a people they destroyed. While a simultaneous outcome plays out between Katara and Azula, as Katara similarly chooses mercy once she's obtained a position of power and control over Azula.

Special note also to Zuko who demonstrates that he actually cares more about protecting people than about winning his Glorious Deathmatch of Imperialist Honor. Which also serves as a rejection of Azula's beliefs that relationships are founded on fear and control. Zuko, too, rejects the belief systems of Ozai and Azula and warrants recognition. Ozai would never have taken a hit like that for Azula. Azula would never take a hit like that for Ty Lee.

It's this mercy that breaks the Hundred-Year War, destroying not the perpetrators of it but the very principles on which it is founded. This philosophical annihilation of Azula and Ozai's very understanding of strength and power is their villainous "demise", and weighs far more than just cutting their heads off and calling it a day ever could.

There is no correct answer to whether or not heroes should kill. What matters most is how the demise the writer chooses for the villain reflects upon the story's central ideas and thesis.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hundred Line writing team interview from Famitsu issue 1895

Let's start off establishing what each of you do in the game.

Kazutaka Kodaka: The project was originally my idea, and I worked as the General Director and Story Director.

Koutarou Uchikoshi: I worked primarily as a Writer, and also as Director No. 2.

Mr. Togawa, Oyama, Ishii, and Koizumi, please tell us your career history in addition to your role.

Akihiro Togawa: I worked as Gameplay Director, Writer, Screen Composition Director, Schedule Manager, Task Distributor, Debug Manager, and various other miscellaneous roles. I previously worked at Atlus's Team Persona. My roles in the Persona series included Section Leader and Story Director.

Kyouhei Oyama: Aside from being a Writer, I'm the writer in charge of the off-game stories. I was originally a light novel author, but then switched to a freelance game writer job. After working as the main writer for the VR visual novels Tokyo Chronos and ALTDEUS: Beyond Chronos, I was lucky enough to become a member of Too Kyo games.

Nonon Ishii: I'm a Writer and created the Invaders' language. I took a college internship at Too Kyo Games and made my employment official immediately after graduation. This will be my debut title and even I can't believe how massive of a game I'm starting off with.

Youichirou Koizumi: I'm a writer. I knew Kodaka and Uchikoshi since my novelist days and we have been working together since before we founded Too Kyo Games.

I'd like to ask Mr. Kodaka and Uchikoshi how do you feel now that development is finished (note: this interview was conducted on February 28th) and you are now just waiting for the release day.

Kodaka: I'm excited to see what people will say about it, considering that this game is in so many ways different from what I've done before. I'm relieved to see that the Steam demo has been incredibly well-received. I believe that the demo was the right marketing strategy, both for sales and for my mental health. There was a time I was worried about this selling less than a thousand copies, but not anymore (pained laughter).

Uchikoshi: Same answer as Kodaka. We tried a lot of new things, and that got us with a script not only huge but also made through a unique process. I was never capable of imagining player reactions, so no guessing how they'll feel about until I see it happen. In that sense, what I look forward to the most are the post-release reviews.

Was it decided from the get-go that the script size would be humongous?

Kodaka: One of the initial concept keywords was "a visual novel that never ends". We want to create a VN that a player could keep playing for as long as they still wanted, so we predicted a sizable script. We made a game with 100 routes and left the story branching direction to the expert, Uchikoshi. The game was envisioned as an Uchikoshi title first and foremost: everything was built upon the idea of having many routes, and it worked. I can confidently say the game is good.

Uchikoshi: However, we also made it so you don't have to play every route to fully enjoy it. Kodaka's order was to make every route feel like it could have been the true route, so we made different stories covering various genres. We want you find your favorite route and interpret that one as the true ending.

This game is Kodaka's and Uchikoshi's first collaboration. Did you discover anything new about each other working together?

Kodaka: We didn't spend the whole time in neighboring desks, and had distinctively separate tasks, so not really…

Uchikoshi: I just confirmed what I already knew: that Kodaka is an amazing director. Now I see that the reason for that is his willingness to be mean. I keep my distance from my staff, so I struggle to tell them that A was actually supposed to be B. Kodaka doesn't. He makes difficult requests and the staff listens to him because these corrections make the game incredible. I respect and want to learn from him, because that's how a director needs to be.

Kodaka: If you don't say things would be better another way, you'll only regret it later. When I talked about my struggles to a famous anime director, he said "You may think things are acceptable as they currently are, but after you put in the work to improve them, you won't feel the same way." and that really clicked with me. Since then, I stopped holding back on what I tell the staff.

Do you all have any particularly memorable correction requests from Kodaka?

Koizumi: None that I can remember.

Kodaka: That's because you only joined the writing team later. There was barely anything left to fix at that point.

Uchikoshi: Media Vision, the developer, was who had it the roughest, no?

Togawa: No, their problems passed from person to person until they reached me (pained laughter). But none of that ever felt unreasonable. When Kodaka explained something, it was always easy to agree that it would make the game better, so I was constantly feeling positive about my work. However, as the Schedule Manager, there was some internal conflict between "this is guaranteed to improve the game" vs "this will add so many work hours".

Oyama: I loved how this was an easy environment for us writers to get all of our ideas implemented, as the only condition given is that they don't suck. Whenever I had nothing to fix, I'd just come up with something funny, and if the proposal passed the "interesting" threshold, it'd be approved. So it's hard to answer about difficulties when this has been one of the easiest jobs ever.

Ishii: They even implement ideas from a total novice like me. I remember the joy I felt I saw that an idea I came up with on the spot in the middle of a meeting made it into the game.

Kodaka: That's because I'll be taking credits for my subordinates' achievements (laughs).

(laughs) What was the writing process like?

Kodaka: Due to the immense size of this game's script, we decided to split the work between the team. I wrote the main route, then based on that, Uchikoshi came up with the branching system and general ideas for what goes in which branch story, and lastly, we distributed the routes to the writers as necessary. There's only 6 of us here, but including the guest writers, I'd say the game was written by about 10 people.

How did you decide who gets each route?

Uchikoshi: Some they chose, some we assigned to them.

Koizumi: All of mine were just assigned to me without warning (laughs).

Togawa: I didn't get to choose anything either (laughs).

Kodaka: That's because you two joined later. The writers joined the project at different dates. At first, it was just Uchikoshi and Ishii, plus people who aren't here today. Oyama and Koizumi joined in this order, and Togawa was the last. When was it that you entered the team, Togawa?

Togawa: August 2023, I think. It was around that time that I sorted out our schedule and figured out that we'd need a miracle to salvage this production.

Kodaka: Meaning that by September 2023, the writer team wasn't complete yet (pained laughs).

Togawa: I rebuilt that schedule over and over again, but even my best attempts left me unsure if we could deliver the game in time. As such, I had to make Kodaka also write some side routes, and with that, we somehow managed to put the script together.

Yeah, I can see that happening when you have 100 routes…

Kodaka: Still, there were some new discoveries that would never have happened if we weren't splitting the work like this. This is my first time making other people play with my characters, so proofreading the other routes was a kind of fun I never knew before. The feeling of "Is this really what my character would do in this scenario?" is very new and interesting. It's also fun to pick out on each writer's peculiarities. For example, Uchikoshi fans will immediately be able to notice when a route is written by Uchikoshi.

This game features a cast of very unique characters. What was the process of creating them like?

Kodaka: I came up with all the characters on my own, and the first thing I had settled on was that the Special Defense Unit would have 15 students. What changed is that I intended the students to be more down-to-earth characters, but as I kept adding quirks whenever I was finding them too generic, they came to become what they are now.

Uchikoshi: Is that why the characters who join later (Nozomi Kirifuji, Kurara Oosuzuki, Kyoshika Magadori, Yugamu Omokage, Mojiro Moko) are the most eccentric ones?

Kodaka: That was the intention… we even talked about making the designs of the initial team (Takumi Sumino, Takemaru Yakushiji, Hiruko Shizuhara, Darumi Amemiya, Eito Aotsuki, Tsubasa Kawana, Gaku Maruko, Ima Tsukumo, Kako Tsukumo, Shouma Ginzaki) more down-to-earth, but I couldn't handle it. At all. Still, because I initially tried to make the initial squad more down-to-earth, the additional squad naturally came to be the eccentric side.

How did the mascots SIREI and NIGOU originate?

Kodaka: The main thing with SIREI and NIGOU was trying to do something different from Danganronpa's Monokuma and Rain Code's Shinigami. His conduct is similar to them, but I wrote his dialogue with a militaristic flavor in hopes to make him feel more petty and cunning. Being able to have Houchuu Ootsuka voicing SIREI and Ikue Ootani voicing NIGOU was also excellent for distinguishing them from Monokuma and Shinigami.

Was there any character who was easier to write or more challenging?

Kodaka: Danganronpa had characters I didn't know how to use well, but this time, everyone was easy. But I have to say Kirifuji was the one who required the most restraint. She's the one character with nothing crazy going on, so I made sure not to make any dumb jokes with her, as she'd be the one I'd use to recenter myself after going too far in one direction.

What about you, Uchikoshi?

Uchikoshi: All characters had very distinct personalities, which made them all easy to write, but Darumi's dialogue is what came the most naturally to me.

Kodaka: Did bullying Darumi come just as naturally?

All: (laughs)

Uchikoshi: I was doing the screen composition for my routes and the sprite selection for Darumi was the most fun part because all of her expressions fit just right with any of her lines. The hardest was Omokage, I guess.

Kodaka: Omokage's dialogue is annoying to type. You need to manually fix the IME conversion every time (pained laughs).

Uchikoshi: I didn't mean the conversion (laughs). I wasn't good at gauging how much Omokage was interested in killing the other characters. He was difficult.

Togawa: Omokage was the hardest for me, too. It took me until the very end before I grasped his way of thinking.

Kodaka: Omokage's character is easy to understand if you play his solo scenes. But I only wrote that after you had already worked on him…

Togawa: His solo scenes are exactly what made me understand what Omokage was like (awkward laughs).

Did you not make character profiles and background documents for your writers to peruse while writing?

Kodaka: Ishii made his own basic profiles, but I didn't make any comprehensive documents. I know this is not a good practice to have, but the script I wrote already had everything, so I made them read the story to understand the characters.

Interesting. And what character was smooth sailing for Togawa?

Togawa: Magadori and Oosuzuki as a duo. They have so much chemistry that any idea I could have naturally converted into fun dialogue when put to paper. Also, Kawana was easy to write. I love, love, love nice girls like her (laughs).

Kodaka: Honestly, Kawana is so down-to-earth that I always found her scenes lackluster when I wrote them. For that reason, reading the routes that star her was really eye-opening. I'm glad to have someone else writing her, because I couldn't make her good.

Uchikoshi: Kawana really shines the brightest when the writer is Togawa or Koizumi.

Maybe the lack of proper character profiles was what allowed them to fill the gaps so well. Now, what about you, Oyama?

Oyama: Omokage was the easiest. I couldn't understand the way he thinks, but once I realized that I don't need to understand him to write him, he became so heavily featured on my routes that you could easily assume Omokage is the main love interest of the game (laughs). Him aside, I had an easy time with Magadori and Mojiro, characters simple in what makes them tick. The biggest challenges were Takumi and Kirifuji. Characters that are too relevant to the plot are very influenced by what is happening at the moment, so very often I didn't know how to write them.

And you, Ishii?

Ishii: Since my routes were the most comedy-heavy ones, Maruko and Magadori were the easiest. Their overblown reactions to things are hilarious, and the only thing you need to add there to complete a scene is clever commentary from Takumi. Meanwhile, the toughest ones to write were the zealous pair of Yakushiji and Mojiro. I struggled with Yakushiji because I don't know how to make the delinquent archetype appealing, and my lack of wrestling knowledge added a lot of extra work when coming up with references for Mojiro.

Togawa: But thanks to wrestling documentaries, you familiarized yourself with wrestling history and techniques.

Ishi: Yes, I was indeed studying through documentaries to put wrestling moves in my story (laughs).

And what character were you the best or worst with, Koizumi?

Koizumi: I can't think of anyone I didn't know how to handle. For the easiest to write, I wanted to choose students that haven't been mentioned yet, but no, my routes have way too much Magadori, Oosuzuki, and Kawana screentime for it to be anyone else. I'm very strongly attached to these three in particular, and that makes them easy to write.

Kodaka: Since you wanted a character no one mentioned, didn't you have a rough time with Ginzaki? I remember you running out of self-deprecation vocabulary to use at some point.

Togawa: We all researched that independently, meaning Ginzaki's self-debasing lexicon will be very different from route to route.

Kodaka: I was implementing insults I came across online. Just scrolling through social media and going "Wow, this insult is GOOD!" (laughs).

In this age of stricter regulations, I feel like this game really strikes the limits of what is allowable to depict. How did the writing team delineate what it could and couldn't do?

Kodaka: I asked everyone to consult me whenever in doubt, and drew the line at specific points like "no poking fun at real wars". That said, I thought I had kept the sex jokes to a minimum, so it came as a shock to me when I saw a demo review say "too many sex jokes". In my head, the first 7 days playable in the demo had no dirty jokes at all, so my honest first reaction was "WHERE?!".

All: (laughs)

Koizumi: A huge chunk of the dirty jokes got weeded out. The initial version of the script had some really extreme ones…

Kodaka: The woman in the writing team said my jokes were too much, so I did away with them. But then she had no opinions on Uchikoshi's.

Uchikoshi: I was trying to write mine in Kodaka's style, so I have no idea why I didn't get the same reaction (awkward laughs).

Kodaka: The ultimate consequence of that was the sex jokes in Uchikoshi's scripts being more numerous and risqué than in mine (laughs).

Tells us about any memorable situations in the production process.

Kodaka: Splitting the screen composition work with other people was unusual. In my previous works, I handled all the composition on my own, but this time I was working with too big of a script… Since doing it on my own would have taken 5 years (strained laughs), I put Togawa in the schedule management role and made each writer responsible for the screen composition in their respective routes.

Togawa: The decision to let the writers build their own scenes was stressful, considering the schedule was already tight before, and a few of them had never done that before.

By the way, who had never done this before?

Togawa: Oyama and our rookie Ishii.

Oyama: As such, I had to ask questions to Togawa on the desk next to mine every time I didn't know how to do something (laughs).

Kodaka: The writing was generally done remotely, but then everyone had to come to the office to input their scripts into the screen format. Having everyone together facilitated the process of creating the cores of the game's presentation system, and let questions be instantly cleared up.

Togawa mentioned being initially anxious about distributing the screen composition work, but looking back now that it's over, how was it like?

Togawa: Everyone worked hard to follow my schedule, and working together is more exciting than working alone. The most memorable part was how fast Oyama learns. Oyama was a computer-illiterate man who only ever used MS Word. Nonetheless, when he discovered the joy of assigning visual assets to his lines of text, he evolved at breakneck speeds. It was a nostalgic experience, reminding me that I was just like him when I first joined the gaming industry (laughs).

What a heartwarming thing to say in a story about a tight schedule (laughs). Were there any other major advantages to splitting and distributing the screen composition work?

Kodaka: I feel like having to do their own screen composition made the writers learn more about the stories they wrote.

Koizumi: True. Having to select sprites and expressions for every line made me want to edit my scripts, and I could feel the story becoming better as the screen composition process progressed.

Kodaka: It does help polishing the plot. The reason why I have always been doing my own screen composition is because I still would be editing a lot regardless of who made it. I can easily imagine myself going "Nah, this line doesn't work with this sprite". Not to sound too obvious, but a story's writer is always the most qualified person to choose what expression is best placed on each line of dialogue. Building screens also teaches you to pace your scenes. And it will give you a better feel for things when you start writing your next game's script. I believe a game writer's job should always include the screen composition part.

A humanoid Commander for the Invader squad appeared in the demo. Mr. Ishii told us that he was in charge of the Invader language. Can you tell us how you came up with it?

Ishii: Too Kyo's visual designers created the alphabet and my job was to create the pronounced language. The exact mission prompt was to create a Japanese-style syllabary (48 sounds) using phonetic moras that resembled spoken French. The problem is that I don't speak French, so the first step was to constantly listen to French in multiple video apps and engrave the French phonemes into my skull. After I had enough of a notion, I lined up 48 French-sounding syllables and fit them into a kana table. With this conversion, the Invader language was complete.

Uchikoshi: I've already seen people analyzing it.

Ishii: That was a shock to me too. Really impressive considering the sounds were assigned to the letters at random.

Kodaka: Did anyone leak the alphabet?

All: (laughs)

We didn't get to see the Invaders language much in the demo, did we?

Kodaka: They figured it out from the letters that appear together with "New Game", "Continue", "Load" etc. on the title screen.

Ishii: As the one who came up with the language, the fact that people are willing to speculate and analyze under limited information makes me really happy.

Speaking of the Invaders, buffing the ally who finished off the Commander was a pretty original gameplay mechanic. How did you come up with that?

Kodaka: I noted down gameplay ideas while planning the base plot. Things like "I want this battle to have a higher number of enemies" or "I want this battle to use the entire team". One of the ideas I jotted down there was "I want the act of finishing the enemies off to look cruel", and when Media Vision converted that into the game format, they turned into a mechanic that buffs party members.

The coup de grâce cutscene being first-person from the enemy Commander's perspective was impactful.

Kodaka: I'll have to be honest, we only made it from the enemy's perspective to cut corners. I did make an animated cutscene where the Commander appears at the end, but that wasn't part of the initial production plans. We didn't have the time or hands to make 3D models of all Commanders just for a coup de grâce cutscene. We discussed various presentation ideas and came up with the enemy POV where we could use the pre-existing 3D models of the party. By using the enemy's perspective, we were able to further emphasize how fearsome and brutal the party members can be, so that was ultimately for the best.

I'd like to ask a few questions to the Gameplay Director, Mr. Togawa, about mechanics and balance. In my playthrough, I noticed a lot of tricks that the player is able to exploit. It's a superbly polished game, really. How was the development process for the battles?

Togawa: When I joined the battle team, the first thing I did was rethink the game's experience blueprint from the start. Although the battles back them already had a core set of rules, they failed to stand out in comparison to other tactical RPGs and felt obtuse regarding extremely important parts: "what's meant to be a cathartic moment for the player'' and "what's the intended experience for this particular battle". After mulling over the question of what's meant to be a cathartic moment in The Hundred Line's battles in my head, the answers I came up with were "the thrill of wiping hordes of enemies in one move" and "the puzzle element of letting the player assemble the route to get there with some degree of freedom".

I can see that.

Togawa: The design process involved coming up with mechanics, balancing the game around them, etc. for the purpose of setting this cathartic moment as the goal and actualize a battle system that lets the player use diverse methods to reach it. For some basic examples… Including the Special Attacks for the aforementioned thrill of wiping hordes, making character abilities more niche to increase the number of options, etc.

The Invader placement on the board is also exquisite. Knowing how to beat the enemies right increases your number of actions, so things look beatable on really short turn counts.

Togawa: I care a lot about enemy placement. Initially, we had flocks of enemies near Yakushiji, the guy with the wide attack range. But making the intention there too obvious would led to the player feeling handheld and losing excitement. So we adjusted things to let the player figured out on their own how they can take out a swarm in one go.

I also thought that the element of turning party member defeat into a positive to be really well-thought-out, despite the insanity of it.

Togawa: Thank you (laughs). The mechanic of using the lives of your party as disposable tools is a conceptual opposite of traditional tactical RPGs, where you want to avoid harming your party as much as possible. I'm proud to say no one does it like The Hundred Line does. The answer to the question of "what is the battle functionality of sacrificing your friends in THL?" is one that spent a lot of time in the oven. I believe that when you reach the ending, you'll come out of it feeling that this mechanic made the narrative far more immersive.

I look forward to learning the answer to the mystery. I was also surprised by how challenging the battles were. In a September 2024 presentation, Kodaka said that story-driven games want to keep difficulty on the lower end, so I was worried the game would feel lacking to fans of the genre.

Kodaka: Sorry about that. The battle gameplay underwent a lot of adjustments after September, including difficult changes, meaning what I told you in an interview back then is simply not true for the finished version of the game. Back then, I believed the battle gameplay had hit the low ceiling for the best form it could take, but luckily, Togawa finished his screen composition duties around that same month and moved on to balance adjustment. Togawa proposed to keep tweaking the game until the last day of the contract and Media Vision was kind enough to accept those terms, resulting in the last push that elevated the battle quality. Disregard what I said in previous sessions.

Togawa: Every single battle in the game has been altered after September. I'd spend every day on hours-long conversations with Media Vision's director and fine-tuning everything. We also revised character abilities, and there's even one character that had their Specialist Skill changed post-September. There are more things I'd have liked to try with more time, but what I couldn't do here will have to be saved for the sequel… if there ever is one.

Isn't it too early to be thinking about a sequel? I mean, are you not planning any DLC?

Kodaka: None. Everything The Hundred Line could have is already packed in the game. Future plans can always change later, but if I was forced right here right now to come up with an expansion for the franchise, I think I'd do prequel novels covering key moments in the lives of the members of the Special Defense Unit. Shizuhara's backstory is already covered in Oyama's Former Lives of the SDU: File 03 - Hiruko Shizuhara's First Battle, so I suppose it'd be nice to have novels for the rest as well.

Uchikoshi: Sounds feasible. Novels aren't limited by the game's assets, meaning they can be set in places that don't appear in-game.

Togawa: Didn't Oyama want to write the story of the Commanders? There is one stand-out character among the enemy Commanders and Oyama was excitedly imagining a story where this one wins (laughs).

Oyama: I still want to write that if given the chance (laughs).

It won't be long until The Hundred Line's release. Please explain the game's appeal to the people who haven't played the demo yet.

Kodaka: I imagine they're already expecting a good story, and my play experience tells me the game is also well-made as a tactical RPG. Trying out the story and gameplay on the demo would be ideal, but what's shown there is barely a glimpse of the full picture. The 8th day marks the start of a constant stream of incredible events, so I hope the demo players are looking forward to what's coming next.

A closing message from each of you to the fans looking forward to the game.

Togawa: The Hundred Line is my first Director work. I used everything I learned up to this point to honor this title. The staff devoted heart and soul into constructing this, and I can say with my whole heart that the game is good. Please purchase it and experience the crazy world we created. I can think of one scene that will catch a lot of people off-guard.

Oyama: As Togawa just explained, so much effort went into this game that I don't even want to imagine the timeline where it flops (awkward laughs). All I have right now is a wish for success. Please, play my game and spread the word if you like it. @'ing or DM'ing me with your reviews would make my day.

Ishii: When I was first briefed on this project, I was impressed at the amount of text it took to make a visual novel, but later, my more experienced colleagues explained to me that this project was abnormal (laughs). We're delivering a title that demonstrates Too Kyo Games is as "too crazy" as the name says. I hope you enjoy the wildness of it. I'm looking forward to the reviews.

Koizumi: The Hundred Line is Too Kyo's first original IP. It'd be accurate to say the company was made specifically to produce this game, which naturally makes me invested in wanting more people to have a good time with it. Nothing can be better than seeing people grateful that the developer Too Kyo Games exists.

Uchikoshi: Repeating something I said before: I hope you can find one route among the many to be your favorite. And to the completionists wanting to play every route: be my guest.

Kodaka: Fresh news, never revealed before: there is a route where everyone survives. I got really emotional reading this one. You're free to stop playing whenever you're satisfied, but I believe you'll have a tough time coming across another game as wild as this, so I'd like you to savor it as much as you can.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Links:

Design team interview

Music team interview

Special guest interview

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

today I used the phrase "breasting boobily" in casual real life conversation and everyone was shocked asking how I came up with that and I had to explain it. ive been at the devil's sacrament so long that I forgot he wasn't god

129K notes

·

View notes

Text

The Hundred Line character design team interview from Famitsu issue 1895

Hello, Mr. Komatsuzaki and Shimadrill. Tell us how you felt when you read the first project presentation for The Hundred Line.

Rui Komatsuzaki: The initial project proposal already had a pretty solid general idea of the plot, so I only needed to expand on that. The Hundred Line's key concept was 100 endings, so I could already predict that my usual amount of illustrations wouldn't cut it. The actual number went way above my already high expectations. I wasn't used to working this much (pained laughter).

Shimadrill: I joined Too Kyo Games because I was a fan of Kodaka's and Komatsuzaki's work, so I felt like I had to keep up no matter how tough it got. Kodaka and Komatsuzaki are particularly fast workers. I didn't even have time to complain without how much I needed to do.

What exactly was requested for the designs of the Special Defense Unit members?

Kazutaka Kodaka: I gave Komatsuzaki the story's script and a document listing characteristics and nicknames of each character (delinquent for Yakushiji, punk rock for Amemiya, and so on) and asked him to come up with the designs.

Komatsuzaki: The design workflow was the same it was in the previous games. Instead of nailing their characterization one-by-one, I started with a draft of the whole cast based only on the amount and general characteristics of them. I used that to fine-tune the collective balance of the cast, and only after that part was settled that I gave the characters individual attention.

Was the process smooth?

Komatsuzaki: Speaking of things being the same as usual, the first version of the mascot characters was never altered. SIREI got approved at the first try.

Kodaka: Back then, I still hadn't given SIREI's character much thought, so Komatsuzaki could go with whatever design he wanted. SIREI's quirks derived from the design rather than the other way around.

Was NIGOU just as easy?

Komatsuzaki: Yeah. I was told NIGOU could be just a palette swap of SIREI, but I wanted them to be a little different, resulting in the current design.

Any other important points?

Komatsuzaki: I really wanted SIREI and NIGOU to be transparent. After that, I exposed their brains and hearts.

Kodaka: I didn't know how to react when he drew a brain after I had already told him SIREI was a robot. I wasn't sure if it was okay for robots to have brains. But later I came to the conclusion that the best computer imaginable would be one capable of utilizing a live human brain. My final decision was that SIREI and NIGOU are equipped with advanced computers that only resemble human brains, but that's a lore tidbit that never gets said in-game.

Cool.

Komatsuzaki: Also, having read the story, I could imagine this game mascot would take some serious damage, so I thought it was better not to make them animal-themed like Monokuma was. I don't want to see an animal-like mascot being seriously harmed. So I tried to give him a design more tolerable to brutalize.

Changing the subject to the Special Defense Unit, who would you consider the most memorable student?

Komatsuzaki: Unlike my previous games, The Hundred Line has combat outfits, which are mostly uniform for every character. To make the characters easier to identify during combat, there was a greater need to give them diverse, distinct, and memorable body types and heads. This means their conceptualization had great emphasis on their heads and physiques. I'd say Amemiya is the most memorable character. She set the bar for how striking they should be. I tend to use muted colors a lot, but Amemiya's design was an attempt to use colors I normally don't. The cast was balanced with her at the center of the scale.

Speaking of characters, I noticed they have a lot of sprites, as usual. How many did you make per character?

Komatsuzaki: The plan was making about 20 per character, totaling around 300 sprites, but I was wrong in predicting the real number would be 3 digits. There are so many that I stopped counting along the way.

How many did you have counted by the time you gave up?

Komatsuzaki: The total of sprites about 1 year before the game was gold was 1368. I kept making more after that, but I can't give a general figure because I was too afraid to count them.

Drill: No estimates for the final number?

Kodaka: We have over 100 per character, with the biggest ones reaching 200, so… I guess over 2000 in total?

How did you get this many?

Komatsuzaki: Sprite production involves the following steps: 1. I draw drafts for the sprites based the expressions and scenes that pop up in my head while I'm reading the story. 2. I refine the drafts. 3. I put together the sprite list while examining which variations are essential and which are redundant. However, this time the story was too long and I could never be done reading all of it, and until I finish reading, the sprite list only keeps increasing. I had a lot more expressions than usual before the first selection.

Kodaka: We tried to lower the amount. But there's a good reason why the number spiralled out of control: in The Hundred Line, each writer did the screen composition for their own stories. One goes "Keep this one, I'll use it", another goes "Keep this one, I'll use it", and little by little we end up with less thing to cut off, and even more things to add (awkward laughs).

Komatsuzaki: I obviously didn't predict this bloat. Face portraits are far from the only thing I got the amount of digits wrong in THL. I never want to be in a game this overblown again…

Kodaka: But thanks to Komatsuzaki drawing full-body sprites, we could do things we couldn't in previous titles. In Danganronpa, the characters had fixed on-field portraits and only changed expressions when zoomed in for conversation. In The Hundred Line, their sprites can be placed with expressions that fit the situation right from the get-go, making this game feel more living and breathing than its predecessors.

How did the designs for the Class Weapons and Class Armors came to be?

Komatsuzaki: The initial plan was to get the Class Weapons designed by someone other than myself. I had to make The Hundred Line's concept art in a period where I was extremely busy with another game and didn't have much time to work on it. But, for reasons I cannot disclose, requesting the other person stopped being a viable possibility. In the end, I had to do everything myself. I chose the weapons for every student, but since that's very relevant for combat, I first asked Media Vision to give me a general idea of size and shape, then added the defining details based on that.

Kodaka: Amemiya's Class Weapon are kitchen knifes that float midair for no reason. That's something better conveyed by showing a mock-up than by describing verbally.

Some of the Class Weapons are very peculiar. Do they have a shared theme? If yes, what?

Komatsuzaki: The design idea was that they had to seem made of bone and blood, so many of the smaller details look fleshy.

Any favorite Class Weapon?

Komatsuzaki: The most costly ones to produce are the ones that occupy my mind the most. Specifically, Yakushiji's bike, Kawana's AC, and Ginzaki's robot. The robot in particular was hell for Media Vision. I'm truly sorry about that. Most weapons match their mock-ups in size, but the robot was the only one I had to make bigger than they wanted.

Why?

Komatsuzaki: A robot needs to be big enough to comfortably fit Ginzaki inside the cockpit (awkward laughs). Also, thanks to me inventing the whole gimmick of the robot transforming into a shield, Media Vision had loads of extra work for the transformation sequence. I'm very grateful to them for producing a functional transformation sequence despite how the concept art I gave them illustrating what part moves where was so full of errors.

Kodaka: We sorta went crazy with the amount of animations on the robot, but thanks to Media Vision, it looks awesome.

Next, I'd like to ask about Class Armor. What was the design process like?

Komatsuzaki: Like with Class Weapons, I remember producing them on my spare time from other work. First I produced Sumino's to be the base for the other suits, and I wanted them their outfits to look unkempt by default. I actually wanted them to run around in mantles, but since those are time-consuming to model in 3D, that idea was cut from the game. Class Armors are made from blood, so having mantles or not doesn't really matter… That said, the battle models were made by Media Vision's modeller and I had to be insistent to get him to make them the way I drew. I feel so sorry for the sheer amount of constraints he had to work through.

Kirifuji's suit really stands out.

Komatsuzaki: That was a high-effort design. Kirifuji's suit had to be different from everyone else's, for lore reasons.

Kodaka: I was okay with hers being just a palette swap of the others, but Komatsuzaki went with a design that much better reflects her lore.

Komatsuzaki: It's a great design that I came to regret once I had to make multiple sprites for it. It's not the easiest design to draw (pained laughs).

What exactly was requested for the monster designs with the School Invaders and their Commanders?

Kodaka: I told Drill to make the Invaders colorful and toy-like. The popness of the enemy designs contrasts against the overall seriousness of the story, making them more unsettling, in my opinion. It was also decided from the start that the enemies could take more vicious forms, so I believe starting colorful would add to the creepiness of the transformations.

Drill: This request from Kodaka was the basis of the Invader production, and I also took a page from Komatsuzaki's book, only finishing them individually after I had already figured out the balance of the whole group. I remember that, when lining up the full roster of Invaders, I focused on making their silhouettes resemble capsule toys.

Komatsuzaki: I remember you going out to check real figures.

Drill: I took a trip to Nakano Broadway to study soft vinyl kaiju figures.

They're so colorful that every battle had me wanting to eat them.

Kodaka: Did I ever say I wanted the Darumarrs to look like a mixed blob of jelly beans?

Drill: You did. Then I suggested that displaying them as flocks of 3 in one tile would highlight the mixed blob factor and give off the feeling of fighting against large numbers. The idea of placing multiple enemies in the same tile was inspired by Warhammer 4K, which I used to play a lot.

I can see that. Any other production secrets regarding the monsters?

Komatsuzaki: Their coloring was redone soooo many times.

Drill: Their original models were really well-made, but not as saturated as I wanted their colors to be. Changing the lighting wouldn't fix the saturation, so their coloring had to be adjusted by redrawing them. That's what gave them the vibrant candy colors you find so tasty.

Did Kodaka have specific requests for the Commanders design?

Kodaka: The fodder Invaders were colorful, so I asked for the Commanders to look monochrome and divine.

Drill: Those two were the only requests for the collective, but there were specific things he wanted for each individual Commander. For example, the prompt for the Squad 1 Commander was "I want him to look too strong to reasonably be the first boss".

Kodaka: I also told you to make him huge. The debate of "is making TRPG enemies big is a good thing?" is a can of worms I told Shimadrill to ignore and just make the first one you fight look big and strong (laughs).

He sure looked big and strong (laughs).

Drill: That's why I decided on the dragon theming for the Squad 1 Commander. I've seen some demo players reaction to sudden strong-looking boss appearing, so I'd say the design did exactly what Kodaka wanted it to.

The Commander also had a humanoid design. Who did this one?

Kodaka: Komatsuzaki.

Komatsuzaki: We initially wanted Shimadrill, the monster design expert, to do them, but he didn't have the time for it when he was simultaneously working on another game, so I did all of it on my own. The humanoid Commanders also had a major share of restrictions coming from lore and production cost reasons, but with enough attempts, I feel like I managed to make them reasonably distinct from one another, within the limitations. It's easy to tell from how they all have different masks.

Kodaka: When checking the pictures for approval, I thought the way the mask design resembled Skull Knight was so cool. We were almost behind the schedule at the time we assigned the humanoid designs to Komatsuzaki, and there are many of them, so I was expecting simpler designs. Him making their design with this much care and detail in so little time was a pleasant surprise.

Is it true that Shimadrill designed the school backgrounds?

Drill: Correct. I was in charge of the school's exterior and hallways, and drew them in great detail.

Kodaka: Komatsuzaki and I have something of a "When in need, ask Drill" mentality. He is often helping out with the most random situations. For example, we thought the design for the alarm speaker that rings when Invaders attack was lame. Worried that this wouldn't convey tension to the player, we called Drill to make a more striking speaker design.

Drill: If we're counting that, I also redesigned the weird wooden boxes (awkward laughs). That request came quite close to the deadline, and it was something I wouldn't think needed adjustments, but Kodaka is a director particular about the details.

Komatsuzaki: There were so many things we got Drill to redesign because they looked too normal.

What was the hardest part of the background designs?

Kodaka: The first thing to come to mind is the school's exterior. It's always visible during combat, so I asked Drill to draw something memorable. He came up with multiple variations, including more hawkish school illustrations. The Last Defense Academy lore back then wasn't the same it is now, and one of the ideas of having a cannon like the one from Battleship Yamato frequently shooting at the field.

Drill: We actually took reference sheets from Battleship Yamato.

I'd expected you take reference sheets from real schools. Were you avoiding that on purpose?

Drill: We were. For some reason, I had to study exclusively warships, tanks, and spaceships to draw a school (laughs). The Last Defense Academy is important enough to the game to be part of the title, and as someone with the mission to support Kodaka and Uchikoshi at Too Kyo Games, I couldn't afford to put out something uncreative. My job is to figure out what would be fun, and create the showy designs Kodaka and Uchikoshi love so much. I always try my best to be ahead of the game when it comes to their expectations.

I was impressed by how each floor look so different from another. Is that essential to the Shimadrill style?

Drill: No, it's essential to the Kodaka style. He requested every floor to be different, so the hallways wouldn't feel samey to the player.

Kodaka: I got him to come up with multiple hallway variations and chose which of them to use and what color they'd have. There are a lot of objects placed on the hallways, and all of them reflect elements of the Tokyo Residential Complex's culture and history that won't get fully elaborated in-game. Drill came up with lore reasons for the presence of each object in the academy, so you can theorize on how their inclusion makes sense.

There's some really… unique furniture in the background. Special mention to the cooking machine being a Thousand-Armed Kannon statue.

Drill: The robot Kannon was my idea. Kodaka asked me to come up with an automatic cooking machine, so I sought inspiration in pre-90s sci-fi art and Expo videos.

Kodaka: AI could never come up with a Thousand-Armed Kannon cooking machine (laughs).

Never (laughs). Next, tell us about the event CGs.

Kodaka: There are over 600 CG illustrations in The Hundred Line. Most of them are drawn by third-party workers, but Drill and Komatsuzaki finalize the art. They have a base standard of quality, but we do go harder on the more plot-significant ones.

Komatsuzaki: That's right, about 2 months before the game was gold, we were still working on improving the important ones.

Drill: I remember that.

Kodaka: Wasn't there a few that Drill made from scratch because there were too many for the third-party workers to keep up with the production pace?

Drill: I was called "just for a little finishing touches" and when I looked at it, I had to do even the lineart… Normal projects demand a lot less work than that when the game is just two months away from going gold (pained laughs).

I see you were in hell for as long as it could keep you there…

Kodaka: Checking if no CG illustration was contradicting the story was so much work. The most common mistakes were having the students dressed normal in scenes they were supposed to have their Class Armor, and randomly including students that would be absent at that point in time… This kind of verification is usually easy because it's done by the writer who knows everything about the story, but with the size of THL's story, the workload here had to be split between multiple people, plus my part was too big for me to remember all of it. In the end, I had to reread the entire story to see if any of the art had a mistake in it. That took forever.

Komatsuzaki: The Hundred Line is far from our only game conceived to be excessive in scope, but it is a league above the rest. We couldn't have completed it without help from a lot of people beyond just us of Too Kyo Games.

Kodaka: I'm the last person who should be saying this (awkward laughs), but this wasn't a project any normal person would consider realistic, and yet we completed it. I'm proud to say every detail is the way I wanted it to be, and that going into debt for it was the right call. In a choice between a life where I make The Hundred Line and a life where I don't, I'd pick the former without thinking twice. But if you asked me if I wanted to make a second The Hundred Line…

Komatsuzaki: No (pained laughs).

Kodaka: That's where I'm at right now, too. Do not say the word "sequel" in my presence (pained laughs).

(laughs) You heard Kodaka's feelings on it. If you're interested in knowing what kind of game could do this to him, please check out the demo.

Komatsuzaki: The demo currently available only shows the tip of the iceberg. The full game contains experiences you can't even imagine. Please play it for yourself, at least until you reach an ending.

Drill: I know I'm asking for too much, but if possible, I'd like you to play all endings instead of stopping at just one. I want as many people as possible taking a proper look at the CG illustrations I drew, if nothing else.

Kodaka: I feel that. In the writer team interview, I answered "You're free to stop playing whenever you're satisfied", but my honest opinion about it is "Play everything".

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Links:

Writing team interview

Music team interview

Special guest interview

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

i don’t understand people who love a problematic character but get angry when people mention the evil things that character did. like, that’s your man! he’s proud he did all that, support his hobbies!

28K notes

·

View notes

Text

they wouldn't leave that man alone about his characters' smoking habits and that's why we ended up with Venom fucking vaping

8K notes

·

View notes