#1924 Democratic National Convention

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

The second Madison Square Garden, which actually was in Madison Square, on January 17, 1924. It was preparing for the Democratic National Convention in June (and July. There were 103 ballots). Its seating capacity was normally 13,000, but was increased to 20,000 for the convention.

Photo: Associated Press

#vintage New York#1920s#Madison Sq Garden#1924 Democratic National Convention#Jan. 17#17 Jan.#Democratic convention#political convention#arena#old NYC

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bye-Bye, Boss! And The Unsung Socialist Hero Of Cincinnati’s Charter Movement

Where are the parades? Where are the celebrations? Election Day this year marks exactly a century since Cincinnati voters rose up to finally end boss rule in the Queen City.

From the 1880s right up to 1924, Cincinnati had been run by what amounted to a criminal syndicate, with George Barnsdale Cox, known as “Boss Cox,” and his minions controlling every aspect of city politics and – most importantly – city finances through their stranglehold on the Hamilton County Republican Party. The Cox Gang siphoned millions of public dollars into their own pockets, let city schools and public services languish, allowed gambling and prostitution to flourish under police protection, and nationally besmirched the reputation of our city. Just how powerful was Boss Cox? Here is a major national magazine, Collier’s, from 24 September 1910:

“No public officeholder in Cincinnati is allowed to name his own deputies. Cox himself appoints these underlings. He has in each public office his representative, who is in real charge. In one case it was disclosed in a legislative investigation that the regularly elected official was not even allowed the combination of his office safe. That was the property of Cox’s agent.”

And here is The New Republic from 7 May 1924 describing a major source of the Boss’s ill-gotten gains:

“Cox was a grafter. It was definitely proved that he had pocketed many thousands of dollars, bribes paid to him by banks for illegally depositing with them Hamilton County funds.”

By 1924, Cox himself had been dead for eight years, but the ironclad Republican machine he had constructed still sputtered along, led by burlesque impresario Rudolph K. “Rud” Hynicka. It infuriated local progressives that Hynicka didn’t even live in Cincinnati but pulled all the strings – political and purse – in Cincinnati from his office in New York City.

The entire boss system came crashing down on 4 November 1924, when Cincinnati voters marked their ballots by a 2.5 to 1 margin to adopt a city manager form of government eliminating the ward-based city council.

In the years since, mythology has enshrined a conventional explanation of how this peaceful revolution prevailed. In this telling, independent Republicans like Murray Seasongood assumed the founding father roles. Here is a typical summary of the traditional narrative, from an article by William A. Baughin from the Winter 1988 issue of Queen City Heritage:

“Under the direction of Seasongood . . . the Charter Committee conducted a successful campaign to bring about these changes in the fall elections of 1924. After this victory, the Charter Committee remained in existence, completing its transition to a de facto political party when it endorsed and campaigned for a slate of councilmanic candidates in 1925.”

Though not exactly inaccurate, the standard version ignores decades of organized opposition to Boss Cox from Democrats and, notably, Socialists. It is not too strong a statement to assert that Cincinnati’s successful charter vote in 1924 would have been impossible without concerted action by the local Socialists and their allies.

Rarely mentioned these days is a radical reformer who devoted half a century to a campaign for social and economic reform. Herbert S. Bigelow was a provocative and controversial figure throughout a long and eventful life. He opposed United States involvement in the First World War and was kidnapped and horsewhipped because of that. He lobbied for old age pensions, for fair taxation, and for municipal control of utilities and transportation.

Bigelow set the stage for the political coup of 1924 as far back as 1912, when he helped organize a progressive, statewide constitutional convention. Bigelow headed a delegation to that convention from Hamilton County, was elected president of the convention; and guided the convention toward submitting to the voters an Initiative and Referendum amendment, and a Municipal Home Rule amendment as well.

As a young man, studying for the ministry at Cincinnati’s Lane Seminary, Bigelow’s social consciousness was awakened, and he dedicated his life “less for the gospel of heaven above and more for justice here on earth.” As pastor of the old Congregational Church on Vine Street, Bigelow’s social agenda so alienated the old-time congregants that he created a totally new “People’s Church” with no theological dogma, only a commitment to progressive causes. He preached, he said, the Social Gospel.

Bigelow’s church spawned what would today be called a political action committee, known as the People’s Power League, organizing liberals and radicals of every stripe from labor unions to Socialists to disenchanted refugees from the major parties. When the United States entered World War I, Bigelow loudly protested the forced enlistment of men through the draft, a position that almost got him killed. As Daniel R. Beaver relates in his 1957 biography of Bigelow, “A Buckeye Crusader”:

“The minister's outspoken attitude aroused the opposition of many patriotic organizations around Cincinnati and finally brought about a physical attack on him October 28, 1917. Bigelow was kidnapped as he was about to address a meeting of the Socialist Party in Newport, Kentucky, taken to a deserted field and horsewhipped, ‘In the name of the women and children of Belgium.’”

Bigelow that year backed the Socialist Party in Cincinnati’s municipal elections. He was convinced his attackers were egged on by the business and industrial interests of Cincinnati. Bigelow expressed a lifelong antipathy to any cause, no matter how popular, that had the support of Cincinnati’s established capitalists. This prejudice, according to biographer Beaver, affected his involvement in the Charter movement:

“His attitude was clearly shown in 1924 when a battle was begun by moderate Cincinnatians led by Murray Seasongood to introduce the city charter form of government into the political life of Cincinnati. [Bigelow] distrusted the motives of the reformers because of their business connections and remained aloof until it became obvious that he and his followers were needed to circulate petitions for a charter election. Though subsequent events are disputed, it seems that he and his associates exacted from the Charterites a promise to include a plan for proportional representation in their bill in return for the support of Bigelow's organization.”

Despite the essential contributions from the People’s Church, Charterites downplayed the pastor’s involvement because Bigelow, in addition to building grassroot support for municipal reform was also campaigning quite vocally in 1924 for Progressive presidential candidate Robert M. LaFollette, who had the backing of the Socialists. Still, Bigelow was able to influence the Charterites to adopt several reforms that originated in his progressive campaigns.

A much more nuanced version of the victory of 1924 would acknowledge the contributions of organized labor, women and Socialists in addition to the traditional political parties, and especially the role of Cincinnati’s lifelong firebrand, Herbert S. Bigelow.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Women streamed into public office in the 1920s, the largest single increase in women’s officeholding to date, leveling off only after 1930. The Democrats and Republicans began to mandate equal representation of men and women on party committees. Altogether, these achievements covering peace, politics, labor, health care, and the home seemed to indicate a wide acceptance of women’s significance in the public arena.

Yet by 1924 popular magazines were running articles (written by men) with such titles as “Is Women’s Suffrage a Failure?” and “Women’s Ineffective Use of the Vote.” There were signs, even early on, that not all was going according to plan. The only woman in Congress in 1921, Alice Robertson, was an anti-suffragist. Women vastly increased their numbers in office, but the meaning of that increase must be set in a wider context. In 1924, there were 84 women legislators in 30 states. Five years later there were 200, an increase of almost 250 percent. But while there were 200 women in office, there were 10,000 men.

…To some triumphant suffragists the next logical step was an equal rights amendment, which would sweep away all remaining forms of discrimination at once. Activist Alice Paul spearheaded the drive for the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). She presided over the National Women’s Party (NWP) when in November 1923, the 75th anniversary of the first women’s rights convention, at Seneca Falls, New York, it announced the text of the ERA: “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.” A month later the amendment was introduced into Congress.

To Paul, it was logical that the ERA should succeed suffrage as the focus of NWP. Like suffrage, the ERA was only part of the feminist agenda, but it would give women power, which they could then use as they pleased. Instead of becoming the new mass women’s movement, however, the NWP dwindled. It emerged from the suffrage fight in 1920 with 35,000 members. By the end of the decade, it had sunk to 1,000.

…But the divisions among women were not all caused by the women themselves. For one thing, the raids and prosecutions of the Red Scare had a chilling effect on women’s groups. Facing possible jail terms or deportation simply for associating with radical women, some women turned a cold shoulder to former friends. In an era in which organizing at all was suspect, women in the 1920s could either organize together for equality and rights and be labeled “red” and fired, or they could try to go it alone.

It was not then surprising that women in their 20s and 30s who wanted to succeed in the public world of business or politics believed the most important thing to leave behind was “sex-consciousness,” their sense of themselves as women who shared interests with other women. They abandoned any organized quest for general social reform and opted instead for individualism. “Breaking into the human race,” as they put it, and individual success in the world as it was became their goals.

…Despite antagonism toward feminist groups, the 1920s found activist women not so much absent as scattered. No longer were they the “woman movement,” as they had been in the 19th century; now they were women. They still organized, but in a multitude of smaller groups that often opposed each other. Every woman seemed to belong to at least one group, and often to several. There were church groups, parents’ associations, self-improvement clubs, and civic leagues. Many women returned to the causes that had most concerned them before the peak of the suffrage movement.

Some threw all their efforts into the peace movement. Others returned to issues such as social reform, hours and wages for women, clean city streets and water, adequate schooling and playgrounds, and safe factory conditions, for example. In the South, new interracial efforts against lynching occupied some women. In the Southwest, Hispanic women worked for bilingual education.”

- Sarah Jane Deutsch, “The Nature of ‘Liberation’: Inventing a Public Woman.” in From Ballots to Breadlines: American Women, 1920-1940

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTD

TODAY IN HISTORY The Associated Press

In 1924, 14-year-old Bobby Franks was murdered in a “thrill killing” carried out by University of Chicago students Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb (Bobby’s distant cousin).

In 1927, Charles A. Lindbergh landed his Spirit of St. Louis monoplane near Paris, completing the first solo airplane flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 33 1/2 hours.

In 1932, Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean as she landed in Northern Ireland, about 15 hours after leaving Newfoundland.

In 1955, Chuck Berry recorded his first single, “Maybellene,” for Chess Records in Chicago.

In 1972, Michelangelo’s Pietà , in St. Peter’s Basilica at the Vatican, was damaged by a hammer-wielding man. (The sculpture went back on display 10 months later after it was reconstructed.)

In 1979, former San Francisco City Supervisor Dan White was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the slayings of Mayor George Moscone and openly gay Supervisor Harvey Milk. Outrage over White’s lenient sentence sparked the White Night riots that evening.

On May 21 … ON MAY 21 …

In 1471, painter and printmaker Albrecht Durer was born in Nuremberg, Germany.

In 1542 Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto died while searching for gold along the Mississippi River.

In 1832 the first Democratic National Convention got under way, in Baltimore.

In 1840 New Zealand was declared a British colony.

In 1881 Clara Barton founded the American Red Cross.

In 1924 14-year-old Bobby Franks was murdered in a “thrill killing” committed by Nathan Leopold Jr. and Richard Loeb, two students at the University of Chicago.

In 1927 Charles Lindbergh landed his Spirit of St. Louis near Paris, completing the first solo airplane flight across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1956 the United States exploded the first airborne hydrogen bomb over Bikini Atoll in the Pacific.

In 1968 the nuclear-powered U.S. submarine Scorpion, with 99 men aboard, was last heard from. (The remains of the sub were later found on the ocean floor 400 miles southwest of the Azores.)

In 1979 former San Francisco City Supervisor Dan White was convicted of voluntary manslaughter in the slayings of Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Harvey Milk.

In 1980 Ensign Jean Marie Butler became the first woman to graduate from a U.S. service academy as she accepted her degree and commission from the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Conn.

In 1991 former Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated by a suicide bomber.

In 1998, in the wake of deadly anti-government protests, Indonesia President Suharto stepped down after 32 years in power and was succeeded by Vice President B.J. Habibie.

Also in 1998 teen gunman Kip Kinkel opened fire inside Thurston High School in Springfield, Ore., killing two students, a day after killing his parents. (Kinkel was sentenced to 112 years in prison for the slayings.)

In 1999 Susan Lucci won a Daytime Emmy Award for best actress on her 19th try.

In 2004 the UN Security Council approved a peacekeeping force of 5,600 troops for Burundi to help the African nation finally end a 10-year civil war.

In 2012 a suicide bomber killed about 100 and wounded hundreds in Sanaa, Yemen, during rehearsals for a military parade.

In 2014 a Cairo court sentenced former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak to three years in prison for plundering the state treasury. In 2016 U.S. special operations forces launched a drone strike that killed Taliban leader Mullah Mansour in a remote town in Pakistan.

In 2017 Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus performed its last shows at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., ending 146 years as “The Greatest Show on Earth.”

0 notes

Text

Trump preps for massive campaign rally Sunday at New York City's Madison Square Garden

Former President Donald Trump will hold a massive campaign rally in New York City's Madison Square Garden on Sunday, – just nine days before voters cast their ballots.

The event, which was first-come, first-serve, sold out within hours of being announced.

The 19,500-seat venue is home of the New York Knicks and New York Rangers.

The Trump campaign says the program includes political icons, celebrities, musical artists, and friends and family of former President Trump who will all discuss how he is "the best choice to fix everything that Kamala Harris broke."

"This epic event, in the heart of President Trump's home city, will be a showcase of the historic political movement that President Trump has built in the final days of the campaign," the campaign said in a press release.

Elon Musk and Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) CEO Dana White will attend the rally Sunday.

Musk has already hit the campaign trail for Trump, delivering a memorable speech in Butler, Pennsylvania, earlier this month, when the former president returned to the same site where an assassination attempt was made on his life on July 13.

White, who has been a close friend of Trump for years and played a role in him reestablishing the mixed martial arts company in the early 2000s, introduced the former president at this year’s Republican National Convention in Milwaukee, telling the crowd the stakes have never been higher.

Other notable attendees this Sunday include former Independent presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy Jr., former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani, political commentator Tucker Carlson and former Democrat presidential nominee turned Republican Tulsi Gabbard.

High-profile names from the political world include Republican vice-presidential candidate JD Vance, Speaker Mike Johnson, Rep. Elise Stefanik, R-N.Y., and Rep. Byron Donalds, R-Fla.

Republican National Committee Co-Chair Lara Trump as well as the former president’s sons Eric Trump and Donald Trump Jr. will also feature.

Former President Donald Trump speaks at a rally in Uniondale, New York, on Wednesday, Sept. 18, 2024. (Julia Bonavita/Fox News Digital)

The Garden hosted the Republican National Convention (RNC) in 2004 and the Democratic National Convention (DNC) in 1924, 1976, 1980 and 1992.

Then-President Ronald Reagan, in his 1984 re-election landslide, was the last Republican to carry New York in a White House race.

"We're making a play for New Jersey. We're making a play for Virginia," Trump said at a rally earlier this month, before adding that he's also aiming to compete in Minnesota and New Mexico.

Earlier this year, during a campaign stop at an Upper Manhattan bodega, Trump said he would "straighten out New York."

An aerial view of Madison Square Garden and the Skylight at Moynihan Station on Sept. 19, 2020 in New York City. (C. Taylor Crothers/Getty Images)

This will be Trump’s second big rally in the state of New York.

Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump speaks during a campaign rally at Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum on Sept. 18, 2024 in Uniondale, New York. (Getty Images)

Trump also held a rally in the Bronx over the summer at Crotona Park, which had a permit allowance of 3,500 people. The New York Post reported the Bronx rally drew up to 10,000 supporters.

Entrance to Madison Square Garden. (Joan Slatkin/UCG/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The campaign also said they saw more than 100,000 people at the former president’s rally in Wildwood, New Jersey, in May.

Trump previously said New York has "gotten so bad in the last three years, four years."

Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump raises his fist as he departs a campaign event at Nassau Coliseum on Wednesday, Sept.18, 2024 in Uniondale, New York. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

While it is unlikely deep blue New York flips red in the White House race, another rally in the state may help Republicans down the ballot as they try to hold on to their House of Representatives majority in November's elections.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Events 8.28 (after 1920)

1921 – Russian Civil War: The Red Army dissolved the Makhnovshchina, after driving the Revolutionary Insurgent Army out of Ukraine. 1924 – The Georgian opposition stages the August Uprising against the Soviet Union. 1936 – Nazi Germany begins its mass arrests of Jehovah's Witnesses, who are interned in concentration camps. 1937 – Toyota Motors becomes an independent company. 1943 – Denmark in World War II: German authorities demand that Danish authorities crack down on acts of resistance. The next day, martial law is imposed on Denmark. 1944 – World War II: Marseille and Toulon are liberated. 1946 – The Workers’ Party of North Korea, predecessor of the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea, is founded at a congress held in Pyongyang, North Korea. 1955 – Black teenager Emmett Till is lynched in Mississippi for whistling at a white woman, galvanizing the nascent civil rights movement. 1957 – U.S. Senator Strom Thurmond begins a filibuster to prevent the United States Senate from voting on the Civil Rights Act of 1957; he stopped speaking 24 hours and 18 minutes later, the longest filibuster ever conducted by a single Senator. 1963 – March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom: Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gives his I Have a Dream speech. 1964 – The Philadelphia race riot begins. 1968 – Police and protesters clash during 1968 Democratic National Convention protests as protesters chant "The whole world is watching". 1973 – Norrmalmstorg robbery: Stockholm police secure the surrenders of hostage-takers Jan-Erik Olsson and Clark Olofsson, defusing the Norrmalmstorg hostage crisis. The behaviours of the hostages later give rise to the term Stockholm syndrome. 1988 – Ramstein air show disaster: Three aircraft of the Frecce Tricolori demonstration team collide and the wreckage falls into the crowd. Seventy-five are killed and 346 seriously injured. 1990 – Gulf War: Iraq declares Kuwait to be its newest province. 1990 – An F5 tornado strikes the Illinois cities of Plainfield and Joliet, killing 29 people. 1993 – NASA's Galileo probe performs a flyby of the asteroid 243 Ida. Astronomers later discover a moon, the first known asteroid moon, in pictures from the flyby and name it Dactyl. 1993 – Singaporean presidential election: Former Deputy Prime Minister Ong Teng Cheong is elected President of Singapore. Although it is the first presidential election to be determined by popular vote, the allowed candidates consist only of Ong and a reluctant whom the government had asked to run to confer upon the election the semblance of an opposition. 1993 – The autonomous Croatian Community of Herzeg-Bosnia in Bosnia and Herzegovina is transformed into the Croatian Republic of Herzeg-Bosnia. 1993 – A Tajikistan Airlines Yakovlev Yak-40 crashes during takeoff from Khorog Airport in Tajikistan, killing 82. 1996 – Chicago Seven defendant David Dellinger, antiwar activist Bradford Lyttle, Civil Rights Movement historian Randy Kryn, and eight others are arrested by the Federal Protective Service while protesting in a demonstration at the Kluczynski Federal Building in downtown Chicago during that year's Democratic National Convention. 1998 – Pakistan's National Assembly passes a constitutional amendment to make the "Qur'an and Sunnah" the "supreme law" but the bill is defeated in the Senate. 1998 – Second Congo War: Loyalist troops backed by Angolan and Zimbabwean forces repulse the RCD and Rwandan offensive on Kinshasa. 1999 – The Russian space mission Soyuz TM-29 reaches completion, ending nearly 10 years of continuous occupation on the space station Mir as it approaches the end of its life. 2003 – In "one of the most complicated and bizarre crimes in the annals of the FBI", Brian Wells dies after becoming involved in a complex plot involving a bank robbery, a scavenger hunt, and a homemade explosive device. 2009 – NASA's Space Shuttle Discovery launches on STS-128.

0 notes

Text

Divided and Undecided, 2024’s America Rhymes With 1924’s

Things should have been settled. The weary delegates should have already chosen a presidential nominee, packed up their Welcome to New York souvenirs and returned home in time for the nation’s celebration of what it stood for. Instead, the study in indecision that was the Democratic National Convention of 1924 staggered through the Fourth of July weekend, its 3,000 delegates all but ensnared in…

0 notes

Text

Black women have made important contributions to the United States throughout its history. However, they are not always recognized for their efforts, with some remaining anonymous and others becoming famous for their achievements. In the face of gender and racial bias, Black women have broken barriers, challenged the status quo, and fought for equal rights for all. The accomplishments of Black female historical figures in politics, science, the arts, and more continue to impact society.

Marian Anderson (Feb. 27, 1897–April 8, 1993)

Underwood Archives / Getty Images

Contralto Marian Anderson is considered one of the most important singers of the 20th century. Known for her impressive three-octave vocal range, she performed widely in the U.S. and Europe, beginning in the 1920s. She was invited to perform at the White House for President Franklin Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1936, the first African American so honored. Three years later, after the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow Anderson to sing at a Washington, D.C. gathering, the Roosevelts invited her to perform on the steps of the Lincon Memorial.

Anderson continued to sing professionally until the 1960s when she became involved in politics and civil rights issues. Among her many honors, Anderson received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963 and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

Mary McLeod Bethune (July 10, 1875–May 18, 1955)

PhotoQuest / Getty Images

Mary McLeod Bethune was an African American educator and civil rights leader best known for her work co-founding the Bethune-Cookman University in Florida. Born into a sharecropping family in South Carolina, the young Bethune had a zest for learning from her earliest days. After stints teaching in Georgia, she and her husband moved to Florida and eventually settled in Jacksonville. There, she founded the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute in 1904 to provide education for Black girls. It merged with the Cookman Institute for Men in 1923, and Bethune served as president for the next two decades.

A passionate philanthropist, Bethune also led civil rights organizations and advised Presidents Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, and Franklin Roosevelt on African American issues. In addition, President Harry Truman invited her to attend the founding convention of the United Nations; she was the only African American delegate to attend.

Shirley Chisholm (Nov. 30, 1924–Jan. 1, 2005)

Don Hogan Charles / Getty Images

Shirley Chisholm is best known for her 1972 bid to win the Democratic presidential nomination; she was the first Black woman to make this attempt in a major political party. However, she had been active in state and national politics for more than a decade and had represented parts of Brooklyn in the New York State Assembly from 1965 to 1968. She became the first Black woman to serve in Congress in 1968. During her tenure, she co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus. Chisholm left Washington in 1983 and devoted the rest of her life to civil rights and women's issues.

Althea Gibson (Aug. 25, 1927–Sept. 28, 2003)

Reg Speller / Getty Images

Althea Gibson started playing tennis as a child in New York City, winning her first tennis tournament at age 15. She dominated the American Tennis Association circuit, reserved for Black players, for more than a decade. In 1950, Gibson broke the tennis color barrier at Forest Hills Country Club (site of the U.S. Open); the following year, she became the first African American to play at Wimbledon in Great Britain. Gibson continued to excel at the sport, winning both amateur and professional titles through the early 1960s.

Dorothy Height (March 24, 1912–April 20, 2010)

Chip Somodevilla / Getty Images

Dorothy Height has been described as the godmother of the women's movement because of her work for gender equality. For four decades, she led the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW )and was a leading figure in the 1963 March on Washington. Height began her career as an educator in New York City, where her work caught the attention of Eleanor Roosevelt. Beginning in 1957, she led the NCNW and also advised the Young Women's Christian Association (YWCA). She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994.

Rosa Parks (Feb. 4, 1913–Oct. 24, 2005)

Underwood Archives / Getty Images

Rosa Parks became active in the Alabama civil rights movement after marrying activist Raymond Parks in 1932. She joined the Montgomery, Alabama, chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1943 and was involved in much of the planning that went into the famous bus boycott that began the following decade. Parks is best known for her December 1, 1955, arrest for refusing to give up her bus seat to a White rider. That incident sparked the 381-day Montgomery Bus Boycott, which eventually desegregated that city's public transit. Parks and her family moved to Detroit in 1957, and she remained active in civil rights until her death.

Augusta Savage (Feb. 29, 1892–March 26, 1962)

Archive Photos / Sherman Oaks Antique Mall / Getty Images

Augusta Savage displayed an artistic aptitude from her youngest days. Encouraged to develop her talent, she enrolled in New York City's Cooper Union to study art. She earned her first commission, a sculpture of civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois, from the New York library system in 1921, and several other commissions followed. Despite meager resources, she continued working through the Great Depression, making sculptures of several notable Black people, including Frederick Douglass and W. C. Handy. Her best-known work, "The Harp," was featured at the 1939 World's Fair in New York, but it was destroyed after the fair ended.

Harriet Tubman (1822–March 20, 1913)

Library of Congress

Enslaved from birth in Maryland, Harriet Tubman escaped to freedom in 1849. The year after she arrived in Philadelphia, Tubman returned to Maryland to free her family members. Over the next 12 years, she returned nearly 20 times, helping more than 300 enslaved Black people escape bondage by ushering them along the Underground Railroad. The "railroad" was the nickname for a secret route that enslaved Black people used to flee the South for anti-slavery states in the North and to Canada. During the Civil War, Tubman worked as a nurse, a scout, and a spy for Union forces. After the war, she worked to establish schools for formerly enslaved people in South Carolina. In her later years, Tubman also became involved in women's rights causes.

Phillis Wheatley (May 8, 1753–Dec. 5, 1784)

Culture Club/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Born in Africa, Phillis Wheatley came to the U.S. at age 8, when she was captured and sold into enslavement. John Wheatley, the Boston man who enslaved her, was impressed by Phillis' intellect and interest in learning, and he and his wife taught her to read and write. The Wheatleys allowed Phillis time to pursue her studies, which led her to develop an interest in poetry writing. A poem she published in 1767 earned her much acclaim. Six years later, her first volume of poems was published in London, and she became known in both the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The Revolutionary War disrupted Wheatley's writing, however, and she was not widely published after it ended.

Charlotte Ray (Jan. 13, 1850–Jan. 4, 1911)

Charlotte Ray has the distinction of being the first African American woman lawyer in the United States and the first woman admitted to the bar in the District of Columbia. Her father, active in New York City's Black community, made sure his young daughter was well educated; she received her law degree from Howard University in 1872 and was admitted to the Washington, D.C., bar shortly afterward. Both her race and gender proved to be obstacles in her professional career, and she eventually became a teacher in New York City instead.

#10 of the Most Important Black Women in U.S. History#Black Women#Black Women Matter#Black Lives Matter#us history

221 notes

·

View notes

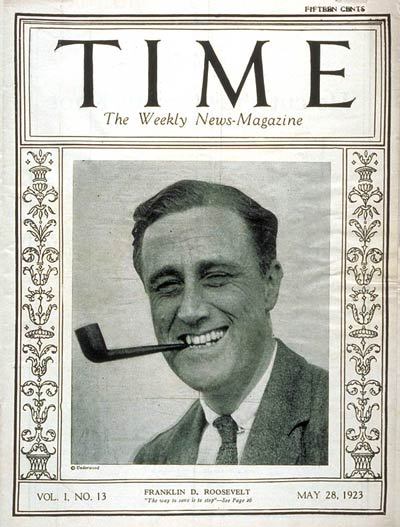

Photo

41-year-old Franklin Roosevelt appeared on the cover of Time magazine of 28 May 1923.

Roosevelt had been a rising political star -- serving as NY state senator (1910-1913), Assistant Secretary of the Navy (1913-1919), and Vice President candidate (with James Cox running for President) in 1920 -- before being stricken with paralytic illness in August 1921.

Roosevelt worked to strengthen his body, learn to stand and walk with heavy braces, and was determined to remain in politics. He endorsed Al Smith in his successful run for NY Governor in 1922 and his nominating speech of Al Smith at the 1924 Democratic Convention was seen as his official return to the national stage.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

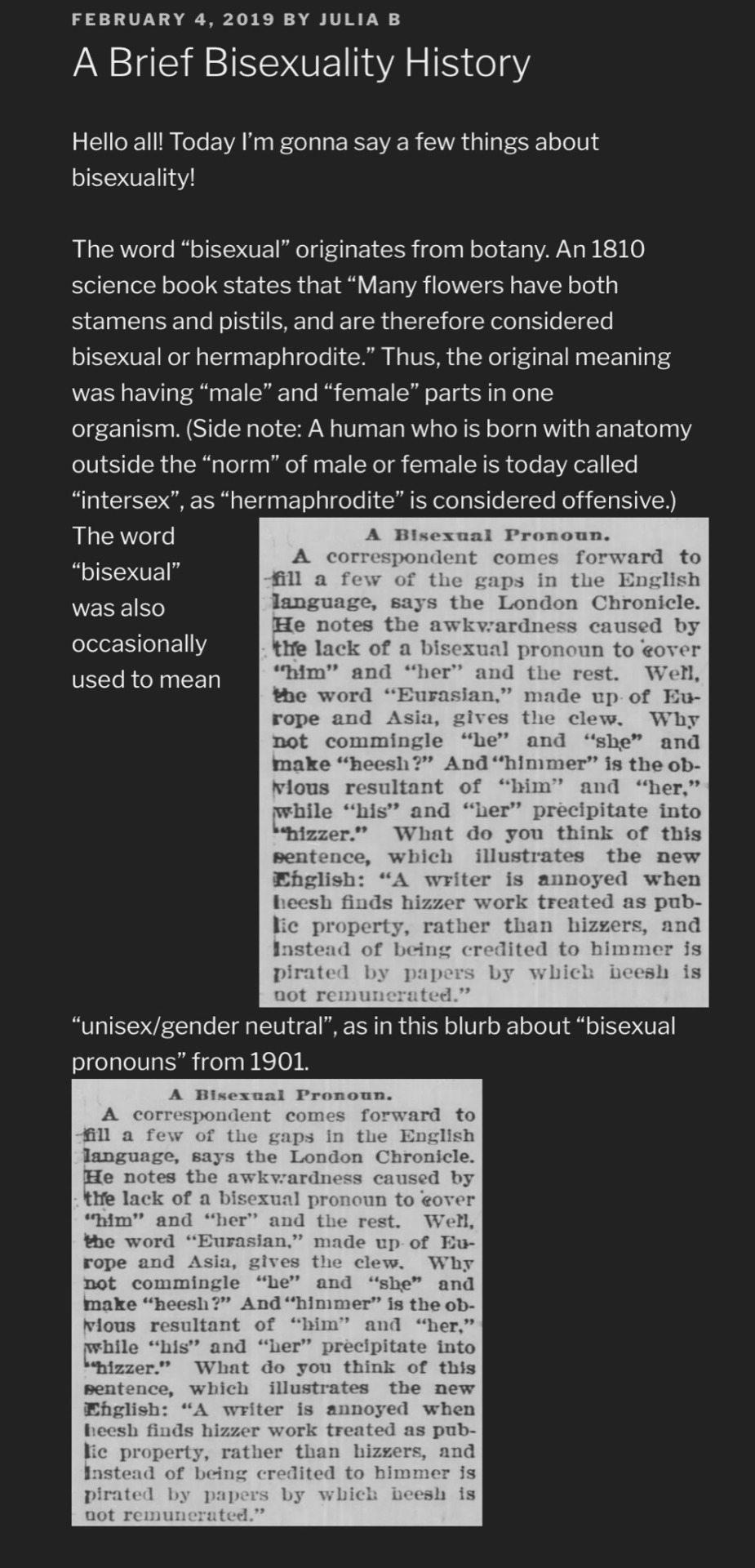

So, how did it come to be a label for a sexual orientation? Well, in the early 1900s, a popular view of same-sex desire was “inversion theory”. This theory, put forth by straight male psychologists, proposed that gay men and lesbian women were sexual “inverts”: people who appeared physically male or female on the outside, but internally/mentally (or “psychically”) were of the “opposite” anatomical sex.

For people whose desires were not exclusively gay or exclusively straight, the theory said they had “psychical hermaphroditism”, so that their desire for women stemmed from their “male psyche” and their desire for men stemmed from their “female psyche”. Some psychologists even stated that bisexual desire indicated a person was “immature”, as in not fully developed. Richard von Krafft-Ebing, in his 1894 book Psychopathia Sexualis, wrote several case studies of “Psychical Hermaphroditism”, including the case of “Mrs. M., aged 44”, who “exemplifies the fact that an inverted and a normal sexual instinct may be united in one person, be it man or woman. […] Her sexual feeling would be directed at one time to women, at another to men.” Another case detailed in this text is that of Mr. X, age 28: “With reference to his sexual inclinations, the patient is still uncertain whether he feels more inclination toward the opposite sex or toward his own sex.” These people whose sexual attractions were a “combination” of “normal” (straight) and “inverted” (gay) would later be deemed “bisexual”.

When gay rights movements began later in the 1900s, men who we would today call bisexual were active in gay men’s groups, and women who we would today call bisexual were active in lesbian groups. In many circles of society back then (e.g. within the sexual liberation movement of the 1960s) being exclusively attracted to the same gender was not a requirement to identify as gay/lesbian. Here, “gay” was used as an umbrella term for all non-straight and/or transgender people.

In other circles, if one was not exclusively gay or exclusively straight, they would be ostracized from both straight and gay communities. For example, Al Weininger, the vice president of the Society for Human Rights, the first known gay men’s organization in the United States (est. 1924), was bisexual and married. He had to keep this a secret, as the group denied membership to bisexuals, believing that they would be less committed to the cause.

A bisexual activist, Brenda Howard, is known as the “Mother of Pride” for her work in coordinating the first Pride March in 1970. Another bisexual, Bill Beasley, was the core organizer of the first Los Angeles Gay Pride March in 1972.

In the 60s and 70s, second-wave feminism led to people who expressed attraction to more than one gender being fully ousted from gay and lesbian communities. Many bisexuals were tired of hiding a part of themselves anyway. Thus, by the mid-70s to early 80s, bisexuals had formed their own communities or subgroups. Remnants of this separation (and the prior “fusion” of bisexuals into gay groups) still remain in the names of longstanding LGBT organizations such as:

PFLAG – “Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays” (est. 1973)

SAGE – “Senior Action in a Gay Environment” (est. 1979 – now re-acronymed as “Services & Advocacy for GLBT Elders”

GLAAD – “Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation” (est. 1985)

LAGBAC – “Lesbian and Gay Bar Association of Chicago” (est 1987)

GLSEN – “Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network” (est. 1990)

COLAGE – “Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere” (est. 1990)

During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s, bisexual men were vilified as a collective scapegoat for the spread of “the gay disease” to straight people. BiPOL, a bisexual political action group, was formed in 1983 to combat this negative stereotype and to advocate for bisexuals. In 1984, BiPOL sponsored the first bisexual rights rally, outside the Democratic National Convention in San Francisco.

On December 5 1998, the Bisexual Pride flag designed by Michael Page was unveiled, and in 1999, the first Celebrate Bisexuality Day (September 23) was organized by Michael Page, Gigi Raven Wilbur, and Wendy Curry.

As you can see, it has been a long long road from the misguided “Bisexuals are psychical hermaphrodites” to the correct “Bisexuals are people who have attraction to more than one gender”!

For decades now, bisexuals have been fighting stereotypes and misinformation, such as “Bisexuals are slutty/greedy/more likely to cheat on me”, or “Bisexuality is a phase/They��re gays in denial/They’re straights faking it for attention”, or “Bisexuality reinforces the gender binary/ Bisexuals are limited to two genders/Bisexuals won’t date trans or nonbinary people”. In fact, none of these are true.

I will close with a quote from the 1990 Bisexual Manifesto.

We are tired of being analyzed, defined and represented by people other than ourselves, or worse yet, not considered at all. We are frustrated by the imposed isolation and invisibility that comes from being told or expected to choose either a homosexual or heterosexual identity.

Bisexuality is a whole, fluid identity. Do not assume that bisexuality is binary or duogamous in nature: that we have “two” sides or that we must be involved simultaneously with both genders to be fulfilled human beings. In fact, don’t assume that there are only two genders.

Do not mistake our fluidity for confusion, irresponsibility, or an inability to commit. Do not equate promiscuity, infidelity, or unsafe sexual behavior with bisexuality. Those are human traits that cross all sexual orientations. Nothing should be assumed about anyone’s sexuality, including your own.

#bisexual history#queer history#bisexual education#queer education#bisexuality#lgbtq community#bi#lgbtq#support bisexuality#bisexuality is valid#lgbtq pride#bi tumblr#pride#bi pride#bisexual#bisexual community#bisexual flag#bisexual nation#queer nation#bisexual positivity#biphobic gay people#biplusus#biphopia#biphobic#support bisexual people#respect bisexual people#lgbtq history#lgbt history#bisexual pride

252 notes

·

View notes

Text

Franklin D. Roosevelt delivers the nominating speech for Alfred E. Smith at the Democratic Convention at Madison Square Garden, June 29, 1924. This speech is often considered FDR’s first major gesture of re-entry into national politics after recovering from his bout with polio. Smith did not get the nomination—that went to John W. Davis, who was roundly defeated in the general election by Calvin Coolidge.

Photo: FDR Presidential Library

#vintage New York#1920s#Franklin D. Roosevelt#Democratic National Convention#1924 election#1924 Democratic convention#nominating speech#June 26#26 June#American politics#FDR

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shirley Chisholm

Photo: National Women’s History Museum

Shirley Chisholm was the first African American woman elected to Congress, serving in the House of Representatives for New York’s twelfth district from 1969 to 1983.[1] Born on November 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, New York, to two immigrant parents. Her father, Charles St. Hill, was a factory worker from Guyana, and her mother, Ruby Seale St. Hill, was a seamstress from Barbados.[2] Her father and mother worked a lot to support their family, leading to Chisholm to be sent to live with her grandmother in Barbados at three years old.[3] Living in Barbados for most of her formative years, Chisholm received much of her early education in Barbadian schools, which used traditional British teachings, such as, reading, writing, and history. Chisholm credited much of her academic success on this type of early education. Returning to Brooklyn at 10 years old, Chisholm attended New York public schools, attending Girls’ High School, where she excelled.[4] Her excellence in school gave her scholarships to several distinguished universities, but because she was unable to afford room and board, Chisholm attended Brooklyn College and lived at home. At Brooklyn College, Chisholm was encouraged to pursue a political career, working with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but after graduating Cum Laude in 1946, she became a nursery school teacher.[5] Chisholm earned her Master’s Degree in early childhood education from Colombia University in 1951 and by 1960, she was a consultant for the New York City Division of Day Care.[6]

Her political career began in 1964 when she was elected to the New York State Legislature, being the second African American to do so.[7] During her time in the State Legislature, Chisholm sponsored fifty bills, eight of which were passed. Some of the most successful of those bills were ones that gave assistance to poor students to go into higher education, provided employment insurance to personal and domestic employees and reversed a law that made it so female teachers lose their tenure while out on maternity leave.[8] After serving in the State Legislature for four years, Chisholm set her sights on the Federal Government.

In 1968, Chisholm won against Civil Rights leader James Farmer for New York’s twelfth district’s seat in Congress. Chisholm’s career in Congress, lasting from 1969 to 1983, saw her fighting for racial and gender equality, the end of the Vietnam War, and more. She served on several House committees, such as Agriculture, Veteran’s Affairs, Rules and Education, and Labor.[9] Chisholm fiercely fought for her district, even protesting her appointment to the Forestry Committee because it had no importance to the people of her district.[10] Chisholm was also a fierce advocate for women’s rights, fighting for a woman’s right to choose and speaking against traditional professional roles of women, such as secretaries, teachers, etc. Chisholm co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus in 1971, which recruits, trains, and supports pro-choice women candidates for office.[11]And Chisholm’s work was far from over, in fact, she wanted to do more on a bigger platform…the presidency.

In 1972, Chisholm became the first woman and first African American to seek the nomination for one of the two major political parties. Chisholm sought the Democratic Party’s nomination, but faced discrimination all the way through. Chisholm was blocked from being in any televised debates, having to take legal action in order to get just one speech.[12] She was able to enter the primaries of twelve states, winning twenty-eight delegates, and receiving 152 first ballot votes at the Democratic National convention.[13] Her campaign was focused on civil rights, police brutality, the Judicial system, gun control, drug abuse, and much more.[14] Though she did not win the nomination, Chisholm did not let it slow her down, serving ten more years in congress, before retiring in 1983.

After retiring from Congress, Chisholm became a professor at Mt. Holyoke College in Massachusetts, teaching politics and women’s studies.[15] In 1985, Chisholm confounded the National Political Congress of Black Women, which helps facilitate the educational, political, economic, and cultural development of African American Women, in 1984.[16] She retired from teaching in 1987, moving to Florida in 1991. In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated her to be the Ambassador of Jamaica, but she had to decline because of ill health.[17] Chisholm continued to write and lecture, writing two books, Unbought and Unbossed, and The Good Fight, until her death in 2005. Chisholm left a massive legacy for people of color and women that is still felt to this day. Without her hard work and perseverance, we would not be where we are today.

Bibliography

“Home.” National Congress of Black Women - Los Angeles Chapter. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://ncbwinclac.org/.

“Our Mission.” National Women’s Political Caucus. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.nwpc.org/about/.

“Shirley Chisholm Biography.” Encyclopedia of World Biography. Accessed February 11, 2022. https://www.notablebiographies.com/Ch-Co/Chisholm-Shirley.html.

“Shirley Chisholm: CSU.” The California State University. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.calstate.edu/impact-of-the-csu/alumni/Honorary-Degrees/Pages/shirley-chisholm.aspx.

Michals, Debra. “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).” National Women’s History Museum. PWC Charitable Foundation. https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/shirley-chisholm.

[1] Debra Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005),” National Women’s History Museum, PWC Charitable Foundation, 2015, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/shirley-chisholm.

[2] Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).”

[3] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography, accessed February 11, 2022, https://www.notablebiographies.com/Ch-Co/Chisholm-Shirley.html.

[4] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[5] Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).

[6] Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).

[7] Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).

[8] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[9] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[10] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[11] “Our Mission,” National Women’s Political Caucus, accessed February 11, 2022, https://www.nwpc.org/about/.

[12] Michals, “Shirley Chisholm (1924-2005).

[13] “Shirley Chisholm: CSU,” The California State University, accessed February 14, 2022, https://www.calstate.edu/impact-of-the-csu/alumni/Honorary-Degrees/Pages/shirley-chisholm.aspx.

[14] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[15] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,” Encyclopedia of World Biography.

[16] “Home,” National Congress of Black Women - Los Angeles Chapter, accessed February 14, 2022, https://ncbwinclac.org/.

[17] “Shirley Chisholm Biography,��� Encyclopedia of World Biography.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Were Democrats Or Republicans For Slavery

Presidency Of Martin Van Buren

Democrats Responsible for Slavery, Republican Party for Abolition.mp4

The Presidency of Martin Van Buren was hobbled by a long economic depression called the Panic of 1837. The presidency promoted hard money based on gold and silver, an independent federal treasury, a reduced role for the government in the economy, and a liberal policy for the sale of public lands to encourage settlement; they opposed high tariffs to encourage industry. The Jackson policies were kept, such as Indian removal and the Trail of Tears. Van Buren personally disliked slavery but he kept the slaveholder’s rights intact. Nevertheless, he was distrusted across the South.

The 1840 Democratic convention was the first at which the party adopted a platform. Delegates reaffirmed their belief that the Constitution was the primary guide for each state’s political affairs. To them, this meant that all roles of the federal government not specifically defined fell to each respective state government, including such responsibilities as debt created by local projects. Decentralized power and states’ rights pervaded each and every resolution adopted at the convention, including those on slavery, taxes, and the possibility of a central bank. Regarding slavery, the Convention adopted the following resolution:

What Happened In 1969

The war in Vietnam came to a head. The democrats under Kennedy had gotten us into the war and then after Kennedy was killed President Johnson continued and grew our presence in Vietnam.

Peoples opposition to the war became the focus of the democrat party and the emotional democrats became the protagonists for eliminating the policies that kept blacks in the back of the bus as well as free love and marijuana.

I was young at the time and this is the Democratic Party i remember which were opposed to real things. There was a war in vietnam. People were dying. There was segregation.

Republicans didnt resist outlawing segregation. The resistance was focused on the remaining segregationists in the Democratic Party. Strom Thurmond a democrat from the south fillibustered the passage of the civil rights act.

In 1968 the democrats held a national convention. This convention devolved into riots and was the watershed for racism and the Democratic Party. The racists were ejected from the Democratic Party ostensibly.

Democrats today claim that in 1969 what happened is that the racists in the Democratic Party moved to the Republican Party.

There is no evidence of this. Storm Thurmond, Robert Byrd never switched parties. Robert Byrd a former KKK leader stayed a democrat until he retired from the senate in 2010. Biden called Byrd a mentor.

Biden was one of the most outspoken opponents of busing.

None of that is true.

If you arent a democrat then they dont want you in the identity group.

After The Civil War Democrats Continued To Fight Against Equality For Blacks

For 100 years the democrats staged a rear guard action seeking to keep blacks subservient and doing their bidding.

They passed laws to limit black peoples ability to vote, to sit on the front of the bus, to own land, to rent apartments, to go to the same schools and many other things.

If anyone owes black people reparations it is these democrats.

Given this history of democrats it is stunning that the Democratic Party continues to exist. Shouldnt it be disbanded? We are tearing down statues, removing names of historically racist people and institutions so why not destroy the Democratic Party? It is slavery and was the principal advocate of slavery. They also were heavily involved in passing racist laws, hanging blacks and many republicans who opposed the democrats.

Why would anyone want to be part of a party that was historically so critical and central to the whole effort to enslave and repress blacks?

People have a tendency not to be partisan and to label this as white Americans that did this but it was the Democrats. Republicans were the ones fighting it. If not for those republicans the black people in America would never have been freed or gotten voting rights or many other things that had to be fought. Many white republicans were killed by democrats even after the end of the civil war who were called sympathizers.

Again, why doesnt this basic fact that is indisputable matter?

Those blacks who could vote between 1860 and 1969 voted for republicans.

Recommended Reading: How Many Registered Democrats And Republicans Are There

Political Firsts For Women And Minorities

From its inception in 1854 to 1964, when Senate Republicans pushed hard for passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 against a filibuster by Senate Democrats, the GOP had a reputation for supporting blacks and minorities. In 1869, the Republican-controlled legislature in Wyoming Territory and its Republican governor John Allen Campbell made it the first jurisdiction to grant voting rights to women. In 1875, California swore in the first Hispanic governor, Republican Romualdo Pacheco. In 1916, Jeannette Rankin of Montana became the first woman in Congressand indeed the first woman in any high level government position. In 1928, New Mexico elected the first Hispanic U.S. Senator, Republican . In 1898, the first Jewish U.S. Senator elected from outside of the former Confederacy was Republican Joseph Simon of Oregon. In 1924, the first Jewish woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives was Republican Florence Kahn of California. In 1928, the Republican U.S. Senate Majority Leader, Charles Curtis of Kansas, who grew up on the Kaw Indian reservation, became the first person of significant non-European ancestry to be elected to national office, as Vice President of the United States for Herbert Hoover.

A New Political Party

After passing all these pro-slavery laws, in May 1854, a number of anti-slavery members in Congress formed a new political party to fight slavery. These anti-slavery members were from the Whigs, Free Soil advocates and Emancipationists. They wanted to gain equal rights for black Americans.

The name of that party? They called it the Republican Party. They chose this name because they wanted to return to the principles of freedom and equality. These are the principles first put forth in the documents of the republic before the pro-slavery Congressional members had misused and manipulated to their own purposes those original principles.

You May Like: Who Won More Democrats Or Republicans

The New Deal Era: 19321939

After Roosevelt took office in 1933, New Deal legislation sailed through Congress at lightning speed. In the 1934 midterm elections, ten Republican senators went down to defeat, leaving them with only 25 against 71 Democrats. The House of Representatives was also split in a similar ratio. The “Second New Deal” was heavily criticized by the Republicans in Congress, who likened it to class warfare and socialism. The volume of legislation, as well as the inability of the Republicans to block it, soon made the opposition to Roosevelt develop into bitterness and sometimes hatred for “that man in the White House. Former President Hoover became a leading orator crusading against the New Deal, hoping unrealistically to be nominated again for president.

Most major newspaper publishers favored Republican moderate Alf Landon for president. In the nation’s 15 largest cities the newspapers that editorially endorsed Landon represented 70% of the circulation. Roosevelt won 69% of the actual voters in those cities by ignoring the press and using the radio to reach voters directly.

Roosevelt carried 46 of the 48 states thanks to traditional Democrats along with newly energized labor unions, city machines and the Works Progress Administration. The realignment creating the Fifth Party System was firmly in place. Since 1928, the GOP had lost 178 House seats, 40 Senate seats and 19 governorships, though it retained a mere 89 seats in the House and 16 in the Senate.

Southernization; Oh That Sounds Fun Wait It Isnt

From the 1960s to the 2000s a southernization of the Republican party occurs. Paired with Goldwater and;Hoover states rights conservatism and along;with old Anti-Communist ideology, it was enough to completely change the political parties.

From the late 1800s to the 2000s Republican progressives moved toward the Democratic Party and Southern Conservatives moved toward the Republican party. See;the New Deal Coalition and Conservative Coalition.

The grand result is that the David Dukes of the world today fly the Confederate Battle flag and vote Republican.

This story;is a major reason why the voter map looks the way it does.

Meanwhile, while we can still see Gores and Clintons, and sometimes even a Byrd, in the modern Democratic party, those Redeemer and Redeemed liberals made a conscious choice to ally with the dominate Progressive and Neoliberal factions in this cycle.

You May Like: When Did The Southern Democrats Become Republicans

What Does Republican Mean

The word republicanmeans of, relating to, or of the nature of a republic. Similarly to the word democratic, the word republican also describes things that resemble or involve a particular form of government, in this case the government in question is a republic. A republic is a government system in which power rests with voting citizens who directly or indirectly choose representatives to exercise political power on their behalf.;

You may have noticed that a republic sounds a lot like a democracy. As it happens, most of the present-day democracies are also republics. However, not every republic is democratic and not every democratic country is a republic.

For example, the historical city-state of Venice had a leader known as a doge who was elected by voters. In the case of Venice, though, the voters were a small council of wealthy traders, and the doge held his position for life. Venice and other similar mercantile city-states had republican governments, but as you can see, they were definitely not democratic. At the same time, the United Kingdom is a democratic country that has a monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, and so it is not a republican country because it is not officially a republic.;

Slavery And The Emergence Of The Bipartisan System

Civil Rights and Slavery – Republican and Democrat Parties – Prager University

From 1828 to 1856 the Democrats won all but two presidential elections . During the 1840s and 50s, however, the Democratic Party, as it officially named itself in 1844, suffered serious internal strains over the issue of extending slavery to the Western territories. Southern Democrats, led by Jefferson Davis, wanted to allow slavery in all the territories, while Northern Democrats, led by Stephen A. Douglas, proposed that each territory should decide the question for itself through referendum. The issue split the Democrats at their 1860 presidential convention, where Southern Democrats nominated John C. Breckinridge and Northern Democrats nominated Douglas. The 1860 election also included John Bell, the nominee of the Constitutional Union Party, and Abraham Lincoln, the candidate of the newly established antislavery Republican Party . With the Democrats hopelessly split, Lincoln was elected president with only about 40 percent of the national vote; in contrast, Douglas and Breckinridge won 29 percent and 18 percent of the vote, respectively.

Don’t Miss: Are There More Democrats Or Republicans In Us

On This Day The Republican Party Names Its First Candidates

On July 6, 1854, disgruntled voters in a new political party named its first candidates to contest the Democrats over the issue of slavery. Within six and one-half years, the newly christened Republican Party would control the White House and Congress as the Civil War began.

For a brief time in the decade before the Civil War, the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson and his descendants enjoyed a period of one-party rule. The Democrats had battled the Whigs for power since 1836 and lost the presidency in 1848 to the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor. After Taylor died in office in 1850, it took only a few short years for the Whig Party to collapse dramatically.

There are at least three dates recognized in the formation of the Republican Party in 1854, built from the ruins of the Whigs. The first is February 24, 1854, when a small group met in Ripon, Wisconsin, to discuss its opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The group called themselves Republicans in reference to Thomas Jeffersons Republican faction in the American republics early days. Another meeting was held on March 20, 1854, also in Ripon, where 53 people formally recognized the movement within Wisconsin.

On July 6, 1854, a much-bigger meeting in Jackson, Michigan was attended by about 10,000 people and is considered by many as the official start of the organized Republican Party. By the end of the gathering, the Republicans had compiled a full slate of candidates to run in Michigans elections.

Culture Conflict And Al Smith

At the 1924 Democratic National Convention, a resolution denouncing the Ku Klux Klan was introduced by Catholic and liberal forces allied with Al Smith and Oscar W. Underwood in order to embarrass the front-runner, William Gibbs McAdoo. After much debate, the resolution failed by a single vote. The KKK faded away soon after, but the deep split in the party over cultural issues, especially prohibition, facilitated Republican landslides in 1924 and 1928. However, Al Smith did build a strong Catholic base in the big cities in 1928 and Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s election as Governor of New York that year brought a new leader to center stage.

the myth of the Democratic Party masterfully re-created, a fresh awareness of the elemental differences between the parties, and ideology with which they might make sense of the two often senseless conflicts of the present, and a feeling for the importance of dynamic leadership. The book was a mirror for Democrats.

You May Like: Are Any Republicans Running Against President Trump

Presidency Of Andrew Jackson

The spirit of Jacksonian democracy animated the party from the early 1830s to the 1850s, shaping the Second Party System, with the Whig Party as the main opposition. After the disappearance of the Federalists after 1815 and the Era of Good Feelings , there was a hiatus of weakly organized personal factions until about 18281832, when the modern Democratic Party emerged along with its rival, the Whigs. The new Democratic Party became a coalition of farmers, city-dwelling laborers and Irish Catholics. Both parties worked hard to build grassroots organizations and maximize the turnout of voters, which often reached 80 percent or 90 percent of eligible voters. Both parties used patronage extensively to finance their operations, which included emerging big city political machines as well as national networks of newspapers.

Behind the party platforms, acceptance speeches of candidates, editorials, pamphlets and stump speeches, there was a widespread consensus of political values among Democrats. As Mary Beth Norton explains:

The party was weakest in New England, but strong everywhere else and won most national elections thanks to strength in New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and the American frontier. Democrats opposed elites and aristocrats, the Bank of the United States and the whiggish modernizing programs that would build up industry at the expense of the yeoman or independent small farmer.

Why It Doesnt Make Sense To Equate Modern Democrats With The Old Southern Democrats

The Democrats, formally the;anti-Federalists,;had an;aversion to aristocracy from the late 1700s to the progressive era.

That truism;led to the southern conservatives of the solid south like;John C. Calhoun and small government liberals like Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, and Martin Van Buren allying;in the same party;for most of U.S. history.

However,;that changed;after Civil Rights under LBJ and the rise of Goldwater States Rights Republicans .

Today the solid south, and figures like Jeff Sessions, are in an alliance in the big tent of the Republican Party . This was as much a response to the growing progressiveness of the Democratic Party as anything.

One simple way to confirm this is to look at the factions of;Lincolns time. There were four. They;were:

The Northern liberal Whig/Republicans, The;Nativist Know-Nothing; allies of the Whig/Republicans, The Southern Democrats and their Northern allies , and The;Free Soil;;allies of the Democrats who;took a libertarian like position.

Todays Democrats are more like socially liberal Whig/Republicans , libertarians are like Free Soilers , Trumpians are like Nativist Know-Nothings , and Southern Democrats are like the modern Southern conservative Republicans.

The current parties are thus:

Social Liberals and Neoliberals vs. Social Conservatives and Neoliberal Conservatives AKA Neocons .

Clearly, the country has never been fully polarized, even at its most polarized.

Also Check: Do Republicans Want To Impeach Trump

The Second Bush Era: 20002008

George W. Bush, son of George H. W. Bush, won the 2000 Republican presidential nomination over Arizona Senator John McCain, former Senator Elizabeth Dole and others. With his highly controversial and exceedingly narrow victory in the 2000 election against the Vice President Al Gore, the Republican Party gained control of the Presidency and both houses of Congress for the first time since 1952. However, it lost control of the Senate when Vermont Senator James Jeffords left the Republican Party to become an independent in 2001 and caucused with the Democrats.

In the wake of the on the United States in 2001, Bush gained widespread political support as he pursued the War on Terrorism that included the invasion of Afghanistan and the invasion of Iraq. In March 2003, Bush ordered for an invasion of Iraq because of breakdown of United Nations sanctions and intelligence indicating programs to rebuild or develop new weapons of mass destruction. Bush had near-unanimous Republican support in Congress plus support from many Democratic leaders.

Bush failed to win conservative approval for Harriet Miers to the Supreme Court, replacing her with Samuel Alito, whom the Senate confirmed in January 2006. Bush and McCain secured additional tax cuts and blocked moves to raise taxes. Through 2006, they strongly defended his policy in Iraq, saying the Coalition was winning. They secured the renewal of the USA PATRIOT Act.

source https://www.patriotsnet.com/were-democrats-or-republicans-for-slavery/

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Democrats Nominate James Cox For President, FDR for Vice President

The Democratic National Convention in progress in San Francisco.

July 6 1920, San Francisco--A few weeks after the Republicans’, the Democrats convened their national convention in San Francisco on June 28. Just like the Republicans, the Democrats had no clear nominee going into the convention, and had three major contenders. The first was William McAdoo, Wilson’s Treasury Secretary until December 1918, and also his son-in-law from May 1914. The second was Wilson’s Attorney General, A. Mitchell Palmer, who had tried to make a name for himself as a crusader against anarchists and Bolsheviks after his house was bombed by an anarchist in June 1919. The Palmer Raids of November 1919 and January 1920 arrested thousands of suspected anarchists and communists, and deported over 500 of them, among them Emma Goldman. Palmer’s star had faded somewhat since his prognostications (informed by intelligence from J. Edgar Hoover) of attacks and unrest on May Day 1920 proved to be unfounded. The third was James Cox, the Governor of Ohio. Also running were New York Governor Al Smith (who would receive the 1928 nomination), Ambassador to the UK John W. Davis (who would receive the 1924 nomination), along with other hopefuls and favorite sons.

Not directly running, but waiting in the wings, were two giants of the Democratic Party. William Jennings Bryan hoped to be nominated for a fourth time, and President Wilson believed that an unprecedented third term could be necessary to secure America’s entry into the League of Nations, despite all evidence to the contrary and his continuing infirmity since his stroke. While Wilson did not enter the race directly, his refusal to rule himself out left his son-in-law, McAdoo, in an awkward position, thus preventing McAdoo from taking active steps to secure the nomination.

Bryan attempted to lead a fight for the platform, but was repeatedly checked. A proposed plank to adopt the Treaty of Versailles with reservations, along with a Constitutional amendment to reduce the necessary Senate vote for treaty ratification to a simple majority, was rejected; the delegates were loyal to Wilson’s position on this matter. Another proposal, a “bone-dry” plank on Prohibition (which had already been in force since January), was similarly defeated.

The balloting for the Presidential nomination began on July 2. After the second ballot, McAdoo led with 289 votes (out of a total of 1097), with Palmer close behind with 264, followed by Cox with 149 and Al Smith with 101 (90 of which were from New York). As the Democrats required a two-thirds majority to pick a nominee, no candidate was even close. Another twenty ballots were held on July 3. Cox had a major surge on the seventh ballot as Smith and other favorite sons dropped out of contention and many New York and New Jersey delegates switched to him; the totals were then 384 McAdoo, 295.5 Cox, and 267 Palmer. On the twelfth ballot, Cox took the overall lead (404-375.5-201), but hit a peak of 468.5 delegates on the 15th ballot and made no additional progress until the convention recessed just before midnight after the 22nd ballot.

Wilson’s man at the convention, Secretary of State Colby (Lansing having been sacked in February for supposed disloyalty), hoped the deadlock would lead to an opportunity for Wilson, who was still beloved among the delegates in San Francisco. At the right moment, a motion to suspend the rules and nominate Wilson by acclamation might just pass. He had been warned off such a plan by DNC leadership, but after 22 ballots thought the opportunity might soon present itself. A journalist warned Wilson’s private secretary, Joe Tumulty, however. Tumulty, who had been busy hiding the President’s condition since October, was decidedly opposed to his renomination, and warned Edith Wilson that such a motion was unlikely to succeed and that the President would be humiliated and perhaps blamed for the deadlocked convention. Colby backed down, and the balloting resumed on July 5. McAdoo retook the lead on the 30th ballot, and still held it when the convention recessed briefly after the 36th ballot.

After the 38th ballot, Palmer released his delegates and Cox once again had the lead. However, it still took until the 43rd ballot for Cox to secure a majority, and then finally on the 44th ballot Cox, at 1:39 AM on July 6, was nominated by acclamation once it was clear he had secured two-thirds support. The next morning, after Cox was consulted, former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt was chosen as the Vice Presidential nominee. Charismatic, young (this was several years before his polio), from the critical state of New York, and with an ideal last name, Roosevelt was quickly approved by an exhausted convention.

Sources include: Patricia O’Toole, The Moralist.

#wwi#ww1#ww1 history#ww1 centenary#world war 1#world war i#world war one#The First World War#The Great War#1920 election#United States#wilson#woodrow wilson#Edith Wilson#mcadoo#fdr#franklin roosevelt#july 1920

9 notes

·

View notes

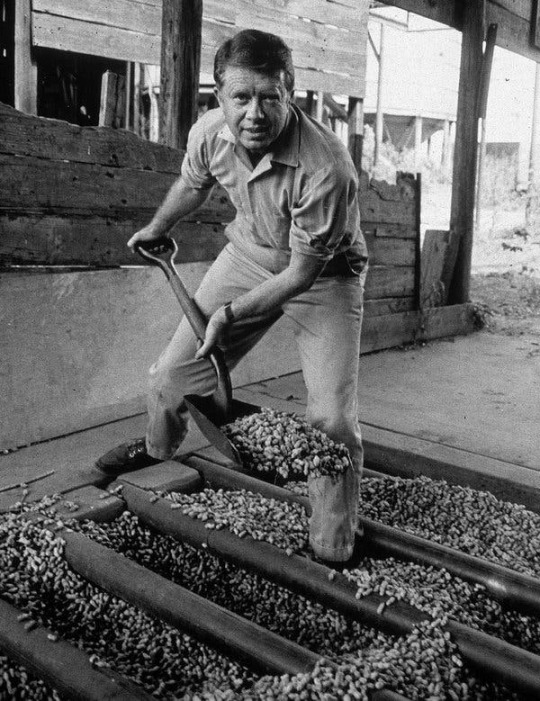

Photo

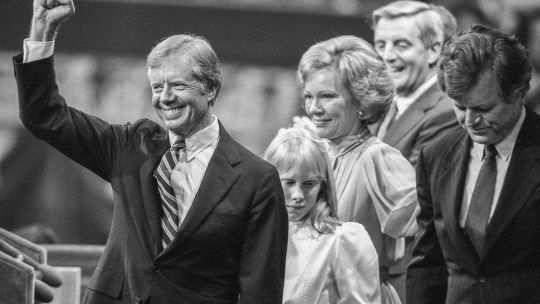

Arrivals & Departures 01 October 1924 James Earl Carter Jr.

James Earl Carter Jr. is an American politician, philanthropist, and former farmer who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as a Georgia State Senator from 1963 to 1967 and as the 76th governor of Georgia from 1971 to 1975. Since leaving the presidency, Carter has remained engaged in political and social projects as a private citizen. In 2002, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work in co-founding the Carter Center.

Raised in Plains, Georgia, Carter graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1946 with a Bachelor of Science degree and joined the United States Navy, where he served on submarines. After the death of his father in 1953, Carter left his naval career and returned home to Georgia to take up the reins of his family's peanut-growing business. Carter inherited comparatively little due to his father's forgiveness of debts and the division of the estate among the children. Nevertheless, his ambition to expand and grow the Carters' peanut business was fulfilled. During this period, Carter was motivated to oppose the political climate of racial segregation and support the growing civil rights movement. He became an activist within the Democratic Party. From 1963 to 1967, Carter served in the Georgia State Senate, and in 1970, he was elected as Governor of Georgia, defeating former Governor Carl Sanders in the Democratic primary on an anti-segregation platform advocating affirmative action for ethnic minorities. Carter remained as governor until 1975. Despite being a dark-horse candidate who was little known outside of Georgia at the start of the campaign, Carter won the 1976 Democratic presidential nomination. In the general election, Carter ran as an outsider and narrowly defeated incumbent Republican President Gerald Ford.

On his second day in office, Carter pardoned all the Vietnam War draft evaders by issuing Proclamation 4483. During Carter's term as president, two new cabinet-level departments, the Department of Energy and the Department of Education, were established. He established a national energy policy that included conservation, price control, and new technology. In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaties, the second round of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT II), and the return of the Panama Canal Zone to Panama. On the economic front, he confronted stagflation, a persistent combination of high inflation, high unemployment and slow growth. The end of his presidential tenure was marked by the 1979–1981 Iran hostage crisis, the 1979 energy crisis, the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In response to the invasion, Carter escalated the Cold War when he ended détente, imposed a grain embargo against the Soviets, enunciated the Carter Doctrine, and led a 1980 Summer Olympics boycott in Moscow. In 1980, Carter faced a challenge from Senator Ted Kennedy in the primaries, but he won re-nomination at the 1980 Democratic National Convention. Carter lost the general election to Republican nominee Ronald Reagan in an electoral landslide. He is the only President in American history to serve a full term of office and never appoint a justice to the Supreme Court. Polls of historians and political scientists usually rank Carter as a below-average president; he often receives more positive evaluations for his post-presidential work.

In 1982, Carter established the Carter Center to promote and expand human rights. He has traveled extensively to conduct peace negotiations, monitor elections, and advance disease prevention and eradication in developing nations. Carter is considered a key figure in the Habitat for Humanity charity. He has written over 30 books ranging from political memoirs to poetry while continuing to actively comment on ongoing American and global affairs, such as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The earliest-serving of the five living U.S. presidents, Carter is the longest-lived president, the longest-retired president, the first to live forty years after his inauguration, and the first to reach the ages of 95 and 96.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Democrat party switch lie / myth

Historical face punch courtesy GOP-TEA-PUB TUMBLR. Tumblr keeps taking this fact bomb down. Spread it.

June 17, 1854The Republican Party is officially founded as an abolitionist party to slavery in the United States.

October 13, 1858 During the Lincoln-Douglas debates, U.S. Senator Stephen Douglas (D-IL) said, “If you desire negro citizenship, if you desire to allow them to come into the State and settle with the white man, if you desire them to vote on an equality with yourselves, and to make them eligible to office, to serve on juries, and to adjudge your rights, then support Mr. Lincoln and the Black Republican party, who are in favor of the citizenship of the negro. For one, I am opposed to negro citizenship in any and every form. I believe this Government was made on the white basis. I believe it was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity for ever, and I am in favor of confining citizenship to white men, men of European birth and descent, instead of conferring it upon negroes, Indians, and other inferior races.”. Douglas became the Democrat Party’s 1860 presidential nominee.

April 16, 1862 President Lincoln signed the bill abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia. In Congress, almost every Republicanvoted for yes and most Democrats voted no.

July 17, 1862 Over unanimous Democrat opposition, the Republican Congress passed The Confiscation Actstating that slaves of the Confederacy “shall be forever free”.

April 8, 1864 The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. Senate with 100% Republican support, 63% Democrat opposition.

January 31, 1865 The 13th Amendment banning slavery passed the U.S. House with unanimous Republican supportand intense Democrat opposition.

November 22, 1865

Republicans denounced the Democrat legislature of Mississippi for enacting the “black codes”which institutionalized racial discrimination.

February 5, 1866

U.S. Rep. Thaddeus Stevens(R-PA) introduced legislation (successfully opposed by Democrat President Andrew Johnson) to implement “40 acres and a mule” relief by distributing land to former slaves.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rights to blacks.

May 10, 1866

The U.S. House passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the laws to all citizens. 100% of Democrats vote no.

June 8, 1866

The U.S. Senate passed the Republicans’ 14th Amendment guaranteeing due process and equal protection of the law to all citizens. 94% of Republicans vote yes and 100% of Democrats vote no.

March 27, 1866

Democrat President Andrew Johnson vetoes of law granting voting rightsto blacks in the District of Columbia.

July 16, 1866 The Republican Congress overrode Democrat President Andrew Johnson’s vetoof legislation protecting the voting rights of blacks.

March 30, 1868 Republicans begin the impeachment trialof Democrat President Andrew Johnson who declared, “This is a country for white men, and by God, as long as I am President, it shall be a government of white men.”

September 12, 1868 Civil rights activist