#2500 BCE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

dailymotion

Mohenjo-daro is an archaeological site in Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan. Built c. 2500 BC,Like a wonder in the World.

#Mohenjo-daro#archaeological site#Larkana District#Sindh#Pakistan#Indus Valley Civilization#2500 BCE#urban planning#drainage systems

1 note

·

View note

Text

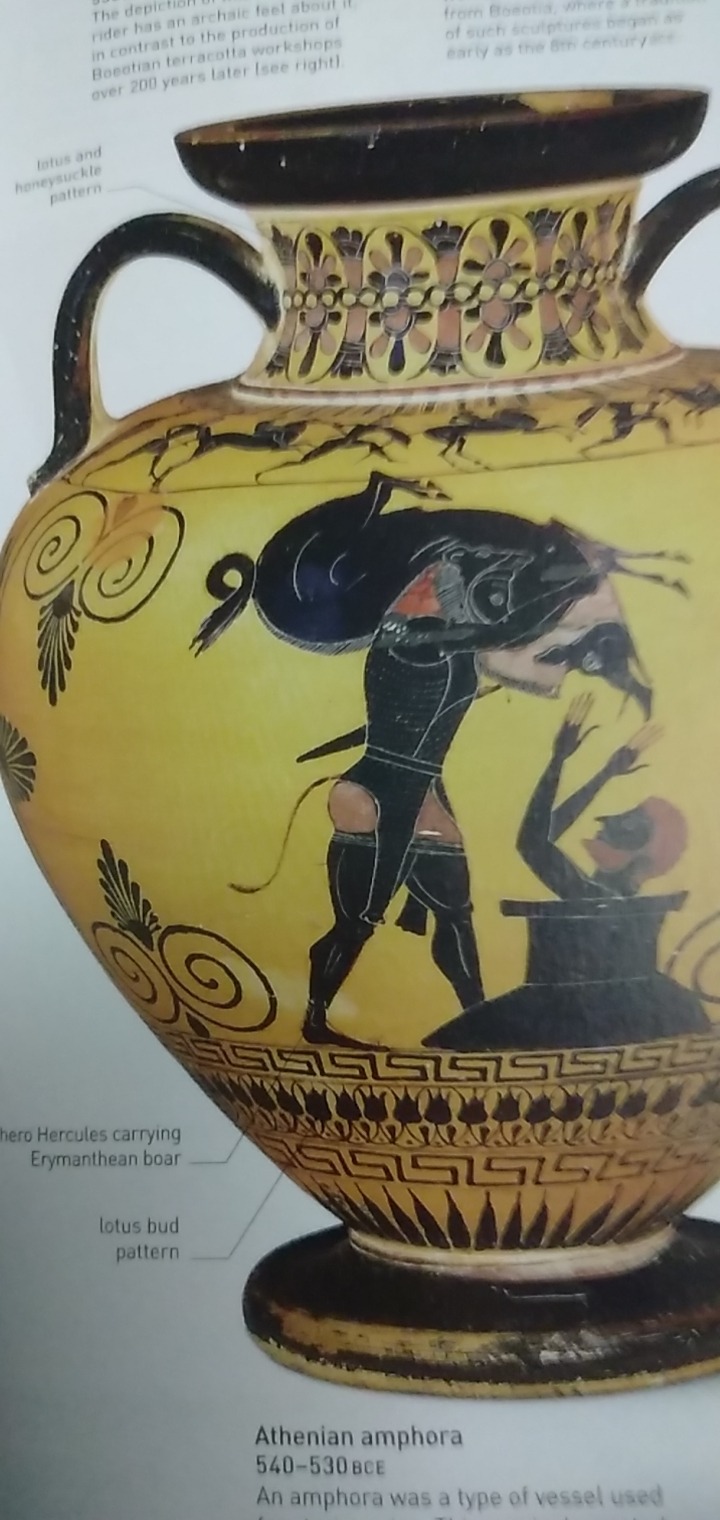

W-why does it look like Hercules is wearing black leather thigh-high boots?

Please tell me that I'm not the only one seeing this?

I... have no idea how to feel about this picture.

#Hercules#thigh boots#why?!?!#OPaconitewolfsbane#if I had to see this picture#so do you#I am having a CRISIS#the caption states that it's from 540-530 bce#so people have been sexualising their blorbos#for over 2500 years#this only appears on my dash#if i add a couple of tags#about it being shadow-banned#Herc & his thigh-highs are too sexy for Tumblr

0 notes

Text

When you think about, the world as most of us recognize it is really no more than 3000 years old. Of course there was writing and civilizations before, of course many of those things reach even us from even before that, but most of what we consider recognizable in the broadest strokes in our current times is at most 3000 years old.

If you think about it, most of Greek philosophy, even as I hate it being considered the first philosophical tradition it's still fundamental to the Western world, is roughly 2500 years old (Thales lived 624-546 BCE). The concept of China as a civilization is also about 3000 years old (Zhou Dynasty), you might stretch it to the Shang Dynasty (3600~ years ago) but anything beyond that probably can't be recognized as China.

And religions, which seem to be those incredibly permanent things? Islam is 1446 years old. Christianity 2000 years old (1992 years, if you believe the dates are correct and Jesus died at 33 years old). Buddhism is roughly 2400-500 years old. Judaism and Hinduism claim to be much, much older, but the series of changes they underwent are of a depth I cannot really even begin to comment on them.

So for virtually all people alive right now, if they were sent just three thousands years in the past (a blink in geological time), you would find nearly nobody who shared anything resembling your language, religion, culture or cosmovision, not even close. Beyond even the technological change. Or just the fact that most people weren't aware of other continents beyond their own.

Just again, something to think about when someone writes about "thousands of years". Even the shortest number that could be encompassed in that statement, three thousand years, yields a completely unrecognizable world.

286 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient Egyptians created artificial plants. They crafted fake flowers and garlands from materials like painted linen, papyrus, and thin metals to decorate temples, tombs, and homes. This practice dates back to around 2500 BCE, making Egypt one of the earliest cultures to produce artificial plants.

Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Flowers, Artificial" . Encyclopedia Americana.

More dork content here

536 notes

·

View notes

Text

figure of a fertility goddess | c. 3000 - 2500 BCE | cyprus, chalcolithic or bronze age

in the j. paul getty museum collection

250 notes

·

View notes

Text

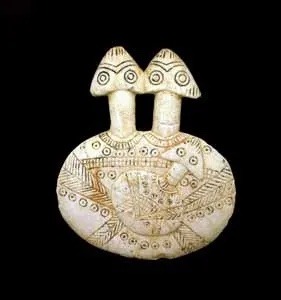

Early Bronze Age Stone Double-Headed Disc-Shaped Figurine and Child. Kültepe, Türkiye. 3000-2500 BCE.

Barakat Gallery.

#Kültepe#turkiye#art#culture#history#turkey#ancient history#middle eastern history#bronze age#stone#sculpture#Barakat gallery

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

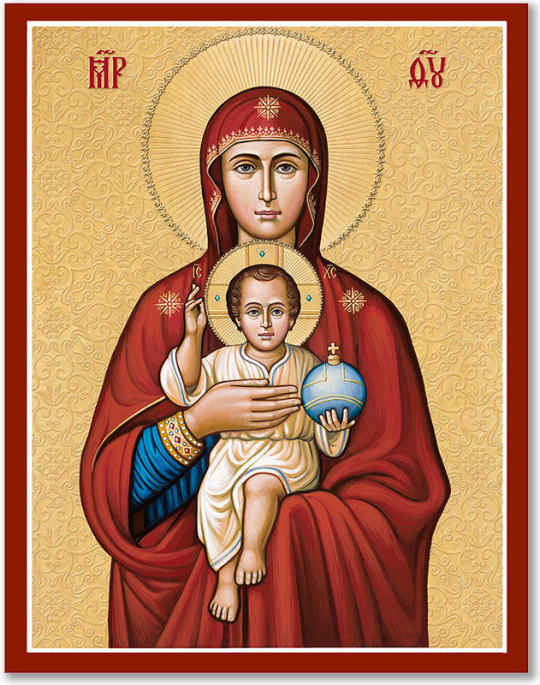

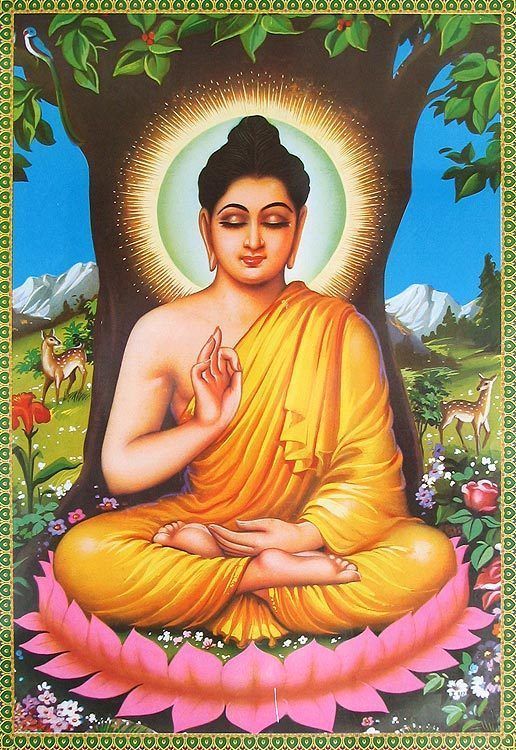

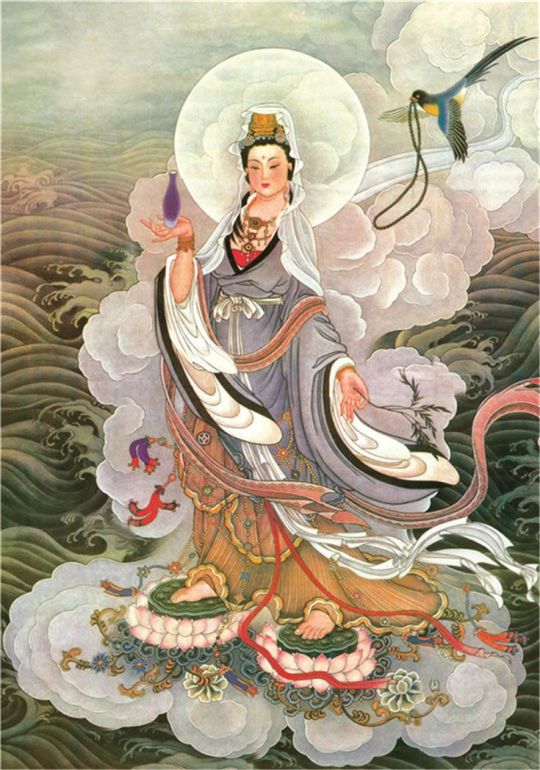

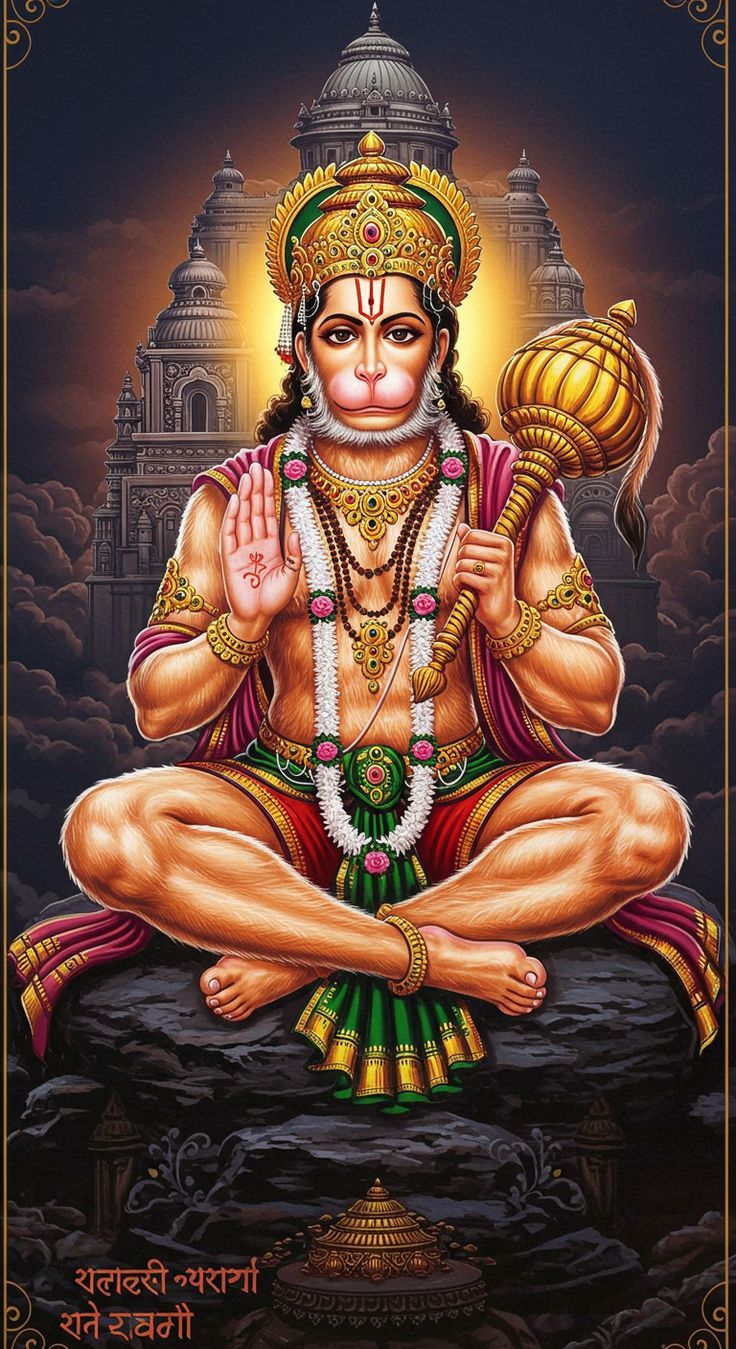

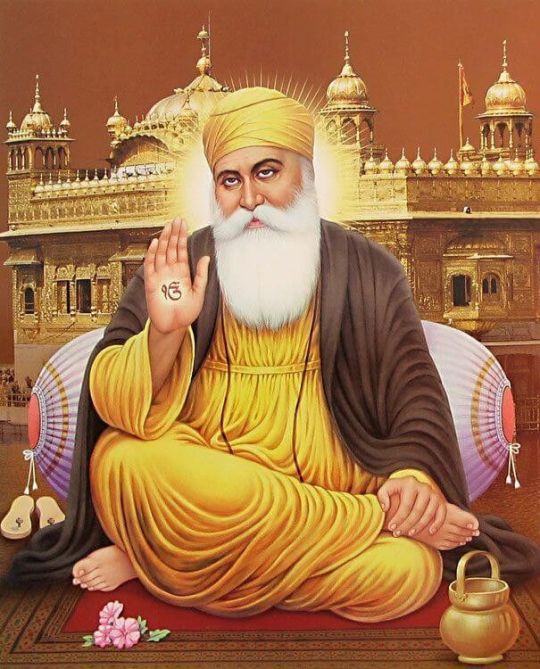

The Universal Gesture of the Raised Right Hand

The raised right hand, a gesture seen across various religions, spiritual traditions, and artistic depictions, carries with it profound symbolic meaning. This ubiquitous gesture is often linked to themes of blessing, protection, authority, and enlightenment, and has been shown in the iconography of deities, spiritual leaders, and mystics for millennia. Its recurrence suggests it is more than just a physical movement; it embodies a universal archetype that is deeply ingrained in human consciousness. Through examining the gesture's origins, symbolism, and often suppressed meanings, we can gain profound insights into its role as a bridge between the material and the divine.

Core Symbolism Across Traditions

At its core, the raised right hand symbolizes reassurance and spiritual power. Across different traditions, it conveys a sense of divine protection, authority, and the dispelling of fear. In Hinduism and Buddhism, this gesture is epitomized in the Abhaya Mudra, which translates to “gesture of fearlessness.” The Buddha, often depicted with his right hand raised to shoulder height, palm outward, uses this gesture as a symbol of peace and protection, calming the fears of the devotee. Similarly, Hindu deities like Vishnu and Shiva adopt this mudra to bestow blessings and offer divine assurance.

Christian and Cross-Cultural Depictions

In Christianity, the gesture is closely associated with Jesus Christ, who is frequently depicted raising his right hand in a benediction, signifying the transmission of divine grace and spiritual power. Mary, too, is shown in similar contexts, her hand raised in a gesture of blessing. The raised right hand also carries significance in Sikhism, where Guru Nanak's gesture symbolizes divine truth and guidance. Even in occult traditions, figures such as Baphomet incorporate this gesture to represent the balance between the spiritual and material realms, echoing the principle of "as above, so below." The universality of this gesture underscores its association with spiritual authority across various cultures.

Esoteric Meaning and the Right-Hand Path

Beyond its religious and spiritual meanings, the raised right hand also has esoteric significance. It is often seen as a symbol of the "Right-Hand Path," a concept tied to righteousness, divine order, and enlightenment. This contrasts with the "Left-Hand Path," which is often associated with hidden knowledge or rebellion against established norms. This duality—light versus dark, order versus chaos—encapsulates humanity’s ongoing journey to balance material existence with spiritual transcendence.

Prehistoric and Ancient Origins

The origins of this sacred gesture stretch far back into prehistory. Before the advent of organized religion, prehistoric shamans—spiritual leaders adept at navigating altered states of consciousness—likely used the raised right hand as a nonverbal form of communication with higher realms. Cave paintings dating back over 30,000 years show figures with raised hands, suggesting a deep, intuitive connection between this posture and spiritual invocation. As civilizations emerged, this gesture became more formalized within religious and ceremonial contexts.

In ancient Sumer (around 4000 BCE), gods and rulers were often depicted with raised hands, invoking divine authority. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, deities like Osiris and Isis are frequently shown with their hands raised during sacred rituals. The Indus Valley Civilization (circa 2500 BCE) integrated mudras, symbolic hand gestures, into their early yogic practices. The Vedic texts (circa 1500 BCE) codified these hand gestures within Hindu rituals, associating them with the control of energy and blessings. Buddhism later adopted the Abhaya Mudra, as exemplified by the Buddha, who used it to calm a charging elephant sent by his cousin Devadatta, symbolizing serene power and protection.

An Archetype Across Cultures

Despite regional differences, the raised right hand has consistently symbolized divine connection across cultures. Its prevalence suggests an archetypal truth embedded in the collective human consciousness, one that spans time and geographical boundaries.

Esotericism and the Mystical Hand

In esoteric traditions such as Freemasonry and Hermeticism, the raised right hand goes beyond a simple gesture of blessing. It symbolizes the oath of initiation into higher knowledge, invoking cosmic truths that transcend ordinary understanding. The human hand itself is often viewed as a microcosm of divine creation, with its five fingers corresponding to the pentagram—a symbol of balance—and the five elements: earth, water, fire, air, and spirit. Ancient cultures believed that certain hand positions could channel energy flows within the body or invoke universal forces, further amplifying the significance of the raised right hand.

Duality and Balance in Symbolism

The duality inherent in this gesture reflects broader cosmic principles. The right hand is often associated with light, order, and divine authority, while the left hand is linked to chaos, hidden knowledge, or rebellion. This contrast is vividly illustrated in occult symbolism through figures like Baphomet, who is depicted with one hand pointing upward, toward the heavens, and the other pointing downward, toward the earth. Baphomet embodies the balance between opposites, serving as a reminder that spiritual enlightenment requires the reconciliation of dual forces.

Suppression of Esoteric Knowledge

Yet, beneath these surface meanings lies a deeper layer of significance, one that has often been suppressed or reinterpreted throughout history. Many cultures embraced the raised right hand as a sacred symbol, but its more esoteric meanings have often been obscured by religious institutions seeking to control spiritual knowledge. The myths surrounding pre-flood civilizations—such as Atlantis—speak of societies that possessed profound knowledge of sacred geometry, cosmic cycles, and spiritual science. This knowledge was likely lost or deliberately erased after catastrophic events reshaped human history.

Early Christianity, too, contained mystical teachings that were later suppressed by institutionalized religion. Gnostic texts describe Jesus as a teacher of self-mastery, rather than blind submission to external authority. Concepts such as reincarnation, which were central to early Christian thought, were removed from doctrine during Church councils. Similarly, the role of Mary Magdalene as an equal spiritual leader was diminished to reinforce patriarchal structures. These omissions serve to obscure Christianity's esoteric roots, favoring dogma over personal enlightenment.

Sound, Frequency, and Vibrational Truths

In addition to these religious suppressions, the science of sound and frequency also holds a key to understanding the deeper significance of the raised right hand. Ancient civilizations understood that sound shapes reality, a concept encoded in sacred languages like Sanskrit and Hebrew. The standard tuning of modern music (440 Hz) contrasts with ancient systems such as 432 Hz tuning, which is believed to harmonize with natural frequencies. This shift may represent a deliberate attempt to disrupt humanity's connection to higher vibrations, further distancing the masses from their spiritual potential.

The Moon and Frequency Control Theories

Some esoteric traditions even suggest that the Moon, with its perfect size for eclipses, may have been artificially placed in Earth's orbit as part of a control mechanism for human consciousness. Its presence raises questions about its origins and whether it serves as a frequency regulator, locking humanity into specific vibrational states.

Ultimately, the raised right hand represents more than just a symbolic gesture; it embodies humanity's shared spiritual heritage. Its presence across cultures suggests that it encodes universal truths about enlightenment: mastery over physical reality through alignment with cosmic laws, protection from ignorance, and guidance toward higher planes of existence. Yet, much of its deeper meaning remains hidden beneath layers of historical suppression and reinterpretation. By rediscovering these lost meanings—whether through ancient texts or modern esotericism—we can begin unlocking humanity's full potential for spiritual awakening.

The raised right hand, as a timeless and powerful gesture, continues to beckon us toward greater understanding and unity with the divine. It is a symbol that transcends time and culture, offering us an ancient key to uncovering the profound mysteries of the universe. Through it, we are reminded of our intrinsic connection to higher wisdom and the eternal quest for spiritual enlightenment.

#symbolism#iconography#sacred iconography#sacred symbols#mystical#mysticism#divine authority#mythical christianity#esoteric christianity#esoteric#occultism#occult#occult symbols#tradition#mudras#buddhism#buddhist#vedic wisdom#vedic#spiritual#spiritual protection#sacred geometry#hermetic#transcendentalism#gnosticism#gnostic teachings#gnosis#religious art#art history#mind over matter

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

i wanna be so clear that i am responding 100% in good spirits and without a lick of ill will. and not adding this discussion to the original post because I just want to respond to an interesting comment without making it a Public Spectacle or anything. read this as though we are in the library sharing facts we're excited about.

@jane-vampeyre reblogged beans post with these tags:

#hey I wanna make a quick note that these people weren’t ancient!#they were way more recent than you’d think!#it’s really easy to fall into the idea that they were ancient bc history tends to blend when you’re not looking#the Incan empire ended in the 1570s#that’s recent!!!#that’s Elizabethan!!#and saying they’re ‘ancient’ helps to reinforce the idea that these people are all extinct#and they’re not!#kept this in the notes bc this is supposed to be a cute/sweet post and I’m being an Anthropologist about it

you're absolutely correct that the people we think of in the historical Americas are not as ancient as we think, and that's so important to remember!! however I want to point out that the common bean (which makes up the majority of the widely-eaten modern bean cultivars) was domesticated, at minimum, around 4,000 years ago (~2500–2000 BCE)! and potatoes were domesticated 7,000–10,000 ago (!!!) – which means strictly speaking potatoes are actually a prehistoric agricultural achievement, not ancient! :) I used "ancient" in the post just to mean "really old" but if I'd done more in-depth research first I would've been more pedantic LOL

I'm not an expert by any means, I just think it's so cool to think about people ten thousand years ago doing agricultural science with results that have not only lasted but become staple crops SO far beyond the region of origin!

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Kingdom of Kush (Nubia): The Great Black Empire of Africa – An In-Depth Analysis

Introduction: Kush – Africa’s Forgotten Superpower

The Kingdom of Kush was one of the greatest Black civilizations in history, yet it is often overlooked in mainstream historical narratives. Located in what is now modern-day Sudan and southern Egypt, Kush was a powerful African empire that lasted for over 3,000 years (circa 2500 BCE – 350 CE).

Kush was not a lesser version of Egypt—it was a strong, independent civilization with its own culture, writing system, military power, and economic dominance. In fact, at several points in history, Kush conquered and ruled Egypt itself.

From a Garveyite perspective, the history of Kush is a testament to:

Black self-determination – The Kushites built their own empires, economies, and armies.

Black resistance – Kush successfully fought off multiple foreign invaders, including Egypt, Persia, and Rome.

Black excellence – The Kushites were masters of trade, iron production, and pyramid construction.

By studying Kush, Black people today can reclaim their legacy and recognize that African civilization and power existed long before European and Arab invasions.

1. Origins of Kush: The Birth of African Civilization

A. The Geography and Early Beginnings of Kush

Kush developed in the Nile Valley, south of Egypt, in a region rich in gold, iron, and precious stones.

This strategic location allowed Kush to control major trade routes between central Africa, Egypt, and the Mediterranean world.

Archaeological evidence suggests that Kushite civilization began as early as 2500 BCE, developing alongside, and in many cases before, Egypt.

Example: The first major city of Kush, Kerma (circa 2400 BCE - 1500 BCE), was one of the oldest urban centres in Africa.

Key Takeaway: Kush was not a colony of Egypt—it was a powerful African kingdom in its own right.

2. The Power and Influence of Kushite Civilization

A. The Three Major Periods of Kushite History

Kushite history is generally divided into three major periods:

1)The Kerma Period (2500–1500 BCE): Early Kingdom of Kush

Kerma was one of Africa’s first powerful kingdoms.

The Kushites built mudbrick palaces, massive burial mounds, and temples that rivalled those in Egypt.

Kush was an economic powerhouse, controlling gold mines and major trade routes connecting central Africa with Egypt.

Kushite warriors were known for their powerful archers, which made their army one of the deadliest in the ancient world.

Example: The Egyptians referred to Kush as the “Land of the Bow” because of its legendary archers.

2)The Napata Period (1000–300 BCE): Kush Conquers Egypt

After Egypt weakened, Kushite kings from Napata seized control of Egypt and ruled as Pharaohs (25th Dynasty).

The Kushite rulers revived Egypt’s culture, temples, and economy, restoring the greatness of the Nile Valley.

The most famous of these rulers was Pharaoh Taharqa, who built monuments across Egypt and defended Africa from Assyrian invaders.

Example: The Bible mentions Taharqa (2 Kings 19:9) as the African ruler who resisted the Assyrian invasion of Egypt.

3)The Meroë Period (300 BCE–350 CE): Kush as a Trade and Ironworking Superpower

Kush moved its capital to Meroë, which became a major centre of iron production, trade, and wealth.

The Kushites developed their own writing system (Meroitic script), one of the world’s first alphabets.

The pyramids of Meroë, more numerous than Egypt’s, show the continued power and cultural uniqueness of the Kushites.

Example: The pyramids of Meroë, which are smaller but more abundant than those in Egypt, prove that Kush had its own distinct royal burial traditions.

Key Takeaway: Kush was not just a copy of Egypt—it was an independent African empire with its own contributions to world civilization.

3. The Economic Power of Kush: Gold, Iron, and Global Trade

A. Kush’s Control Over Global Trade

Kush was one of the richest nations in the ancient world due to its gold mines and iron production.

The Kushites controlled trade routes connecting Africa, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

Kush exported gold, ivory, ebony, frankincense, and iron weapons to Egypt, Greece, Rome, and India.

Example: Ancient Greek and Roman texts describe the Kushites as a wealthy and highly skilled people.

Key Takeaway: Africa was the centre of world trade long before Europeans arrived—the problem is that today, Africa does not control its own resources.

4. The Military Strength of Kush: Warriors, Archers, and Resistance to Foreign Invasion

A. The Kushite Military: Black Warriors Who Resisted Empires

The Kushites were feared for their elite archers, cavalry, and chariots.

Kush successfully fought against Egypt, the Assyrians, the Persians, and even the Roman Empire.

Example: Queen Amanirenas, the one-eyed warrior queen of Kush, led her army against the Romans in 24 BCE.

She destroyed Roman settlements, beheaded a statue of Emperor Augustus, and forced Rome into a peace treaty.

Key Takeaway: Black people must study the military strategies of Kush and understand that no race survives without defending itself.

5. The Decline of Kush: Lessons for Black People Today

A. Why Did Kush Collapse?

Over time, Kush weakened due to:

Deforestation from overuse of iron production.

Trade competition from rival empires.

Invasions from Aksum (modern Ethiopia).

By 350 CE, the Kingdom of Aksum conquered Kush, marking the end of the great Black empire.

Key Takeaway: No Black nation can survive without controlling its economy, resources, and military.

6. The Garveyite Vision: How to Restore the Legacy of Kush Today

A. Reclaiming Black Economic and Political Power

Black people must control their own economies, just like Kush controlled the gold and iron trade.

Black nations must unite, just as Kush once ruled over Egypt and Africa.

We must invest in Pan-African development, creating trade networks between Africa, the Caribbean, and the diaspora.

Example: If all Black people worldwide reinvested in Africa, we could create a new Kushite empire in the 21st century.

Key Takeaway: Kush shows that Black people are builders of empires—the only question is, will we build again?

Conclusion: The Kushite Spirit Must Rise Again

Marcus Garvey taught that Black people must:

"Liberate Africa, build Black industries, and establish a Black global economy."

Will we let whitewashed history continue to erase Black greatness?

Or will we rebuild the power that Kush once had and reclaim our destiny?

The Choice is Ours. The Time is Now.

#ancient nubia#nubia#Kingdom of Kush#black history#black people#blacktumblr#black tumblr#black#black conscious#pan africanism#africa#black power#black empowering#blog#african kingdom#black excellence#ReclaimOurHistory#Garveyism#marcus garvey

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mohenjo-daro is an archaeological site in Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan. Built c. 2500 BC,Like a wonder in the World

Full Video

#Mohenjo-daro#archaeological site#Larkana District#Sindh#Pakistan#Indus Valley Civilization#2500 BCE#urban planning#drainage systems

1 note

·

View note

Text

Dancing Girl

Indus Valley Civilization (2500 BCE)

#hindublr#desiblr#hinduism#india#history#sculpture#indus valley#ancient civilizations#classical civilisation#dance#classical dance#bharatnatyam#indus valley civilization#pretty#elegant

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

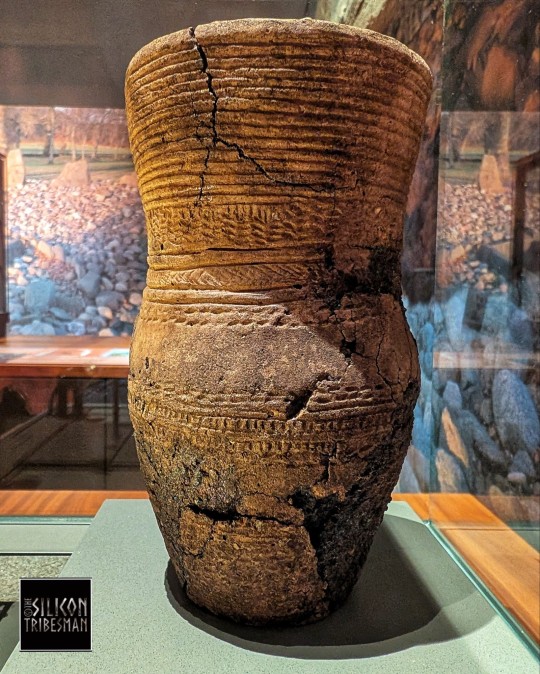

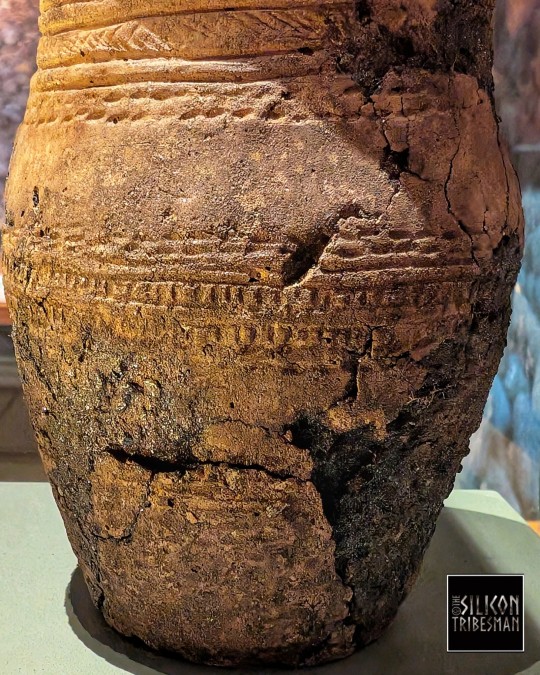

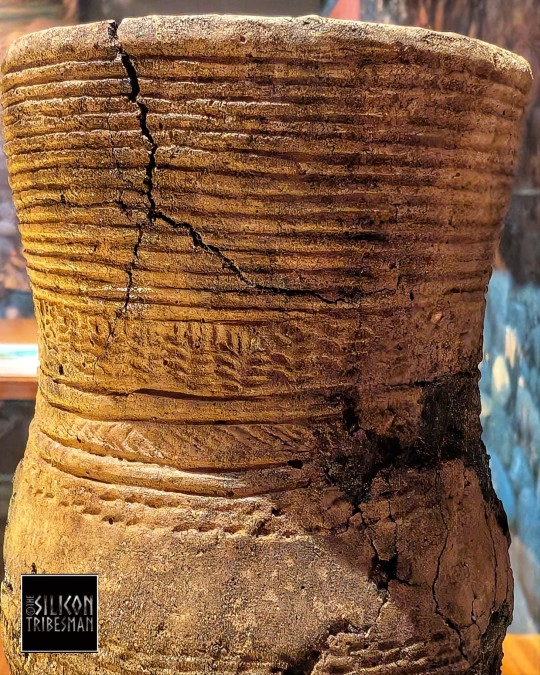

Beaker Vessel from a Cist Burial, 2500 to 1500 BCE, Temple Wood, Kilmartin Glen, Argyll, Scotland

#ice age#iron age#bronze age#stone age#prehistoric#prehistory#neolithic#mesolithic#paleolithic#archaeology#beaker#cist cairn#cairn#pottery#pottery fragments#beaker burial#ancient living#ancient cultures#ancient design#ancient history#kilmartin glen

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

Pride Month special 2025: shifts in gender, shifts in character. A Mesopotamian deity triple feature

The following article, in addition to being a pride month special, is also the third installment of a series which started with Nonconformity, ambiguity, fluidity and misinterpretation: on the gender of Inanna (and a few others) and continued in Ninshubur(s), Ilabrat, Papsukkal and the gala: another inquiry into ambiguity and fluidity of gender of Mesopotamian deities. This time instead of looking at the gender of a specific deity or category of deities I’ll instead discuss three remarkable cases in which a deity’s gender shifted: a mourning goddess turned fire god; a second, originally female, Dumuzi (feat. two unique passages which are as close to non-subtextual Inanna f/f as we can get for now - caveats apply); and a divine clerk in the service of Inanna who went from god to goddess without any other apparent changes.

Note that while I previously said this will be the final installment of the series, I have since realized at least one more will be necessary - stay tuned for further updates.

For now, more under the cut, as usual.

From mourning mother to “the handsome one”: Lisin (and Ninsikila)

Lisin already appears in the Zame Hymns from Abu Salabikh (c. 2500 BCE), one of the oldest religious texts presently known. She is the last of the deities listed, and her corresponding cult center is ĜEŠ.GI (reading uncertain), possibly to be identified as Abu Salabikh itself (Manfred Krebernik, Jan J. W. Lisman, The Sumerian Zame Hymns from Tell Abū Ṣalābīḫ With an Appendix on the Early Dynastic Colophons, p. 14). The hymn is fairly formulaic, and doesn’t say much about Lisin beyond her connection with ĜEŠ.GI. She is referred to with the title ama, literally “mother”, though it is unlikely that it should be taken literally. Instead it most likely functions as an indicator of her role as the tutelary goddess of the corresponding city (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, 46).

A lament focused on Lisin (Lisin A; as you can see here it’s part of the ECSL system, but isn’t actually accessible online), written in first person from her perspective, portrays her mourning the death of an unnamed son, for which she blames her own mother, Ninhursag. She states that this event made her lonely, and that she has no friends or neighbors. The description of mourning itself is fairly formulaic, with all the expected mentions of tearing her own hair, performing lacerations, et cetera. While multiple copies are known, they are imperfectly preserved, and not much can be said about it beyond that (Christopher Metcalf, Sumerian Literary Texts in the Schøyen Collection, p. 52-56).

Lisin’s importance declined by the Old Babylonian period (c. 1800 BCE), if not earlier (Piotr Michalowski, Lisin in RlA vol. 7, p. 33). However, that was not the end of this deity’s history. At an uncertain point after the decline, the name was rediscovered by compilers of god lists. They correctly noticed that Lisin had a spouse, Ninsikila, but that was about it - not even the gender of those two deities was evident to them. Since Lisin typically comes first in older sources, up to the Old Babylonian period (Lisin…, p 32), the new generations of theologians concluded that the former must have been male and the latter female, effectively switching their genders around, as attested for example in An = Anum (Julia M. Asher-Greve, Joan Goodnick Westenholz, Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources, p. 103). To be entirely fair to them - in Old Babylonian sources listing couples together, such as the Nippur god list, the husbands pretty much always precede the wives (Goddesses in Context…, p. 80). It was a decent guess to make based on evidence available to them.

The cylinders of Gudea (wikimedia commons)

A second factor might have been the phonetic similarity between the name of Ninsikila and that of a goddess from Dilmun (Bahrain) at some point introduced to Mesopotamia (Lisin…, p. 32). Despite actually being named Meskilak, the latter could even be referred to as Ninsikila in Mesopotamian sources, as already documented in the long composition preserved on the cylinders of Gudea (Manfred Krebernik, Meskilak, Mesikila, Ninsikila in RlA vol. 8, p. 94). Lisin also developed a distinct new role as a fire deity in apotropaic magic, though it’s not certain if that first happened after the change of gender or before (Markham J. Geller, Healing Magic and Evil Demons. Canonical Udug-hul Incantations, p. 310; Michalowski favors a late date; Lisin…, p. 33). Through dubious linguistic exegesis relying on alternate sign values and homonymy - a favorite pastime of priests and other similar experts in the first millennium BCE - Lisin's name was provided with a new etymology, too. Both cuneiform signs forming it also had readings pertaining to fire (or at least were homonyms of signs which did), so as attested in an esoteric explanatory text (BM 47463) it came to be explained as “he who burns with fire”, “the burning one” or “he who burns an offering”. A further “translation” which arose as a result of similar inquiries was “the handsome one”, relying on the use of a homonym of the sign SI from Lisin’s name being a logographic representation of Akkadian banû (Alasdair Livingstone, Mystical and Mythological Explanatory Works of Assyrian and Babylonian Scholars, p. 60-61).

A Kassite period depiction of Nanaya on a kudurru (wikimedia commons) One final step in Lisin’s career was the incorporation into the court of Nanaya in Borsippa in the late first millennium BCE (Rocío Da Riva, Gianluca Galetti, Two Temple Rituals from Babylon, p. 192). In a single case, the two of them alone occur in a ritual (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 220). In another, Lisin is just one of many courtiers listed (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 192; Usur-amassu, who will be discussed later, shows up too).

Sadly, as far as I am aware no sources shed any additional light on how exactly the connection between Lisin and Nanaya was conceptualized. It was possible to establish how it most likely developed, though. Nanaya’s temple in Borsippa - the Euršaba (“house, oracle of the heart”) - shared its ceremonial name with a temple of Lisin (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 203). While Lisin’s original Euršaba was located in Umma, a city which didn’t even exist anymore by the first millennium BCE, it continued to be referenced in laments and, most important, has an entry in the Canonical Temple List (Andrew R. George, House Most High. The Temples of Ancient Mesopotamia, p. 157). We know that in late periods theological lists could be essentially strip mined for deities to integrate into a city’s pantheon, as well documented in Seleucid Uruk (Julia Krul, The Revival of the Anu Cult and the Nocturnal Fire Ceremony at Late Babylonian Uruk, p. 261). It’s easy to imagine something similar happened in Borsippa as well. The original temple would doubtlessly be long forgotten by the late first millennium BCE, so a priest stumbling upon a reference to Lisin being worshiped there and concluding the local namesake temple is meant instead strikes me as entirely believable.

To be entirely fair, I think there’s a second possibility, though it doesn’t necessarily contradict that proposed by Rocío Da Riva and Gianluca Galetti. One of the rituals pertaining to Lisin’s new role in the Euršaba mentions a cultic installation dedicated to Nabu (Two Temple Rituals…, p. 193). Elsewhere, in astronomical texts, a star named after Lisin (Antares) is associated with Nabu and Borsippa, despite the origin of the name (Hermann Hunger, Lisi(n), RlA vol. 7, p. 32). Zachary Rubin argues that Lisin might accordingly be a stand-in for Nabu in a colophon from Borsippa which lists him together with Nanaya (The Scribal God Nabû in Ancient Assyrian Religion and Ideology, p. 70). However, the cult of Nanaya in Euršaba had no strong connection to Nabu to speak of overall (Goddesses in Context…, p. 282), and as far as I know that is the only house of worship in the city Lisin was introduced to.

From a modern perspective, the gradual shift from a dime a dozen mourning goddess to a one of a kind god certainly might feel almost like trans coding. Ultimately it’s pretty much entirely accidental, though - it’s doubtful anyone involved in Lisin’s theological transformations was aware of the full history of this deity.

(The other) "Dumuzi, she herself": Dumuzi-abzu

Tell al-Hiba, the ruins of Lagash, in 2016 (wikimedia commons) In the third millennium BCE, roughly at the same time when Lisin enjoyed a position of relative prominence in the Zame Hymns, the local pantheon of the state of Lagash included the goddess Dumuzi-abzu. This name can be translated as “good child of the abzu” (Gebhard J. Selz, Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt des altsumerischen Stadtstaates von Lagaš, p. 114). Something that needs to be addressed right off the bat is that the abzu is extremely unlikely to be personified in this case, and it’s virtually impossible Dumuzi-abzu is literally supposed to be the child of the literary character people usually think of today when they hear this term. Prior to the compilation of the Enuma Elish in the late second millennium BCE, which famously pairs Abzu and Tiamat as a theogonic couple, abzu was rarely, if ever, regarded as a deity as opposed to a location (Wilfred G. Lambert, Babylonian Creation Myths, p. 217-218). In a number of sources from between the Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian periods it isn’t even consistently a designation of the watery subterranean domain of Enki/Ea, and might instead be described as mountainous (like in Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta or the hymn Ishme-Dagan D). A variety of sources, including the Temple Hymns attributed to Enheduanna, use it as a poetic term for sanctuaries, making it potentially quite vague depending on context (The Sumerian Zame Hymns…, p. 95). What exactly does it entail in this specific case? Hard to tell, though there were many sanctuaries referred to with the term abzu in Lagash in the third millennium BCE, with Dumuzi-abzu possibly originating in one of them. Furthermore, interpreting the name as “good child of the sanctuary” would be a sensible parallel to fellow Lagashite deity Dumuzi-gu'ena, “good child of the throne room” (Akiko Tsujita, Dumuziabzu. A Goddess and a God, p. 8-9).

Dumuzi-abzu was the tutelary goddess of Kinunir (or Kinirsha), a lost city located somewhere in the proximity of Lagash (Goddesses in Context…, p. 61). We know very little about her character otherwise, though it can be safely assumed that she was closely associated with Nanshe and her daughter Nin-MAR.KI (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116). Offering lists group her with the likes of Nindara, Ninshubur, Hendursaga and other figures of similarly moderate importance in this part of Mesopotamia (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 115).

At least in Lagash, Dumuzi-abzu’s name could be shortened just to Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 114). Manfred Krebernik actually proposed that every single reference to a deity named Dumuzi in Early Dynastic texts - not just from this one state, but also from sites like Tell Fara - pertains to her, and not to Inanna’s spouse, who at the time would be primarily known as Amaushumgalanna (Manfred Krebernik, Drachenmutter und Himmelsrebe? Zur Frühgeschichte Dumuzis und seiner Familie, p. 163-164). This might be too radical of an approach, though (Gebhard J. Selz, Dumuzi(d)s Wiederkehr, p. 215), and it has been suggested that even in Lagash at least in theophoric names Dumuzi might be, well, Dumuzi (Untersuchungen zur Götterwelt…, p. 116).

As of 2024, it remains uncertain when Dumuzi became the default name of Inanna’s spouse, though first unambiguous examples are available from the Sargonic period, and it can be established with certainty that it was used fully interchangeably with Amaushumgalanna by the Old Babylonian period (Jana Matuszak, Hanan Abd Alhamza Alessawe, A Sargonic Exercise Tablet Listing “Places of Inanna” and Personal Names, p. 37). This doesn’t really change the fact that Dumuzi himself “did not belong to the leading deities in any period of Mesopotamian history” and his inflated modern importance owes a lot to the Golden Bough and similar disreputable sources (Bendt Alster, Tammuz(/Dumuzi) in RlA vol. 13, p. 433-434). This is not the time and place for further exploration of this topic, though.

Dumuzi-abzu was eventually seemingly largely subsumed into Dumuzi, but that only happened after her decline as an actively worshiped deity after the Ur III period, which in turn was a result of the area of the former state of Lagash losing its importance (Dumuziabzu…, p. 11-12). The god list An = Anum from the Kassite period identifies Dumuzi-abzu as a male deity, and as one of the sons of Enki, with no reference to any associations with Kinunir, Lagash, or deities from its pantheon. This is presumably a result of a reinterpretation of the abzu in the name as Enki’s dwelling. The shift in gender meanwhile reflected confusion with Dumuzi (Dumuziabzu…, p. 10-12). Andrew R. George suggests that Dumuzi-abzu came to be understood as a title designating the regular Dumuzi during his annual stay in the underworld, based on a broader pattern of confusion between the abzu (in this context explicitly the domain of Enki/Ea, ie. a mythical subterranean sea) and the land of the dead (The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts, p. 861). The apparent conflation of Dumuzi and Dumuzi-abzu resulted in at least one further curiosity relevant to this article. There is a unique love poem which addresses Inanna’s lover, who is left nameless through most of the composition, as Dumuzi-abzu, as opposed to simply Dumuzi. Sumerian has no grammatical gender, so technically it would not be impossible to translate the relevant passage as if the traditional female Dumuzi-abzu was the target of Inanna’s affection, though obviously this is not exactly a plausible interpretation (Bendt Alster, Sumerian Love Songs, p. 143).

Modern replica of a typical Mesopotamian lyre on display in the Iraq Museum (wikimedia commons); in all due likeness Ninigizibara was envisioned with, or as, a similar instrument Surprisingly, Dumuzi-abzu isn’t the only usually feminine figure who got to replace Dumuzi in the role of Inanna’s spouse in an unusual composition. A single late copy of the lament Uru’amma’irabi (BM 38593) casts Ninigizibara as Inanna’s husband (Wolfgang Heimpel, Balang-Gods, p. 588). Usually this deity was described as a goddess, a harp (or lyre) player and a courtier of Inanna (Goddesses in Context…, p. 115). The unique copy is self-contradictory though, since on one hand an Akkadian gloss interprets Ninigizibara as masculine, on the other the passage itself refers to the deity as a “lady” (gašan), as opposed to “lord” (Balang-Gods, p. 588).

Son turned daughter: Usur-amassu

In contrast with Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu, who both became somewhat malleable simply because they were no longer worshiped, the final major case I’ll discuss is a deity who started as a largely irrelevant figure, but arose to a position of prominence only after their gender changed.

A god named Usur-amassu (“obey his command”, possibly implicitly “obey Adad’s command” given the two are defined as father and son in An = Anum) is first documented in the Old Babylonian period; in other words, roughly when the careers of Lisin and Dumuzi-abzu were already in shambles. As is often the case with minor deities, the earliest evidence are theophoric names, one example being Usur-awassu-gamil. However, it’s worth noting the name was itself a given name in the first place, with prominent bearers including a king of Eshnunna (Paul-Alain Beaulieu, The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period, p. 229)

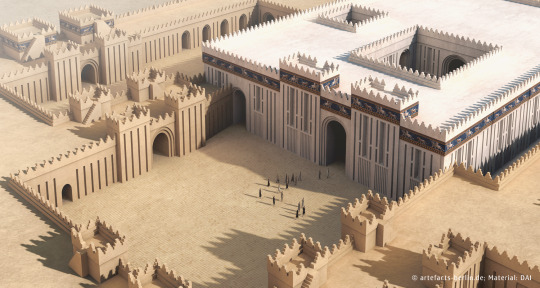

Uruk in the late first millennium BCE (artefacts-berlin.de; reproduced here for educational purposes only, in accordance with the terms of use)

Usur-amassu at some point came to be worshiped in Uruk. The oldest source attesting to this is a short text commemorating the dedication of a field by Kaššu-bēl-zēri, who served as a governor of the Sealand. Sadly nothing about the text makes precise dating possible; however, the element Kaššu is fairly rare in personal names, and was only in the vogue for a couple of decades, roughly between 1008 BCE and 955 BCE (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 225-226). However, in this city Usur-amassu was regarded as a goddess, not a god. This is surprising, as the name is grammatically masculine - and the person “asked” to obey is supposed to be the bearer (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

It should be noted this is hardly the only case where the grammatical gender of a name doesn’t match the gender of a deity, though. As I discussed in the article about Inanna and gender linked in the lead, the name Ishtar is grammatically masculine despite not only functioning as a feminine theonym but even being the source of one of the two generic words for goddess in Akkadian. Looking further, the husband of Nungal, the goddess of prisons, bore the feminine name Birtum (“fetters”; Antoine Cavigneaux, Manfred Krebernik, Nungal in RlA vol. 9, p. 617; I doubt that we are dealing with a Bronze Age equivalent of a he/him lesbian, though I think it would be a fun way to provide this generally irrelevant deity with more personality). There is also the entire phenomenon of nin names, though it is likely that despite being conventionally translated as “lady”, “mistress” etc. this term was initially gender neutral (Goddesses in Context…, p. 6).

To be entirely fair, we do have clear instances of Usur-amassu’s name being partially modified after the shift in gender - the spelling Usur-amassa occurs in Kaššu-bēl-zēri’s dedication and in Neo-Assyrian sources, and while in the Neo-Babylonian period Usur-amassu predominates, this reflects a change in the feminine possessive pronominal suffix in Akkadian, and thus keeps the name equally feminine. The first element was never adjusted, though, and the expected Usri-amassu (or Usri-amassa) is nowhere to be found (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228-229).

In at least one case, Usur-amassu’s gender was indicated by the use of a double determinative - the standard dingir (“deity”), which prefaced theonyms, was combined with innin (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228), a variant of Inanna’s name which could also function as a generic term for goddesses, at least in Uruk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 122).

It might be worth noting that a somewhat similar practice is documented in Old Babylonian Mari, where dingir could be combined with nin for similar purposes. In a single case this created a minor conundrum for researchers, as one of the deities designated this way (to be fair, only in a single source) is Lagamal (“no mercy”; ironically known well from the personal name Lagamal-gamil, “Lagamal is merciful”), who is otherwise firmly a god. Possibly two unrelated deities with the same name arose in two different cities (Gianni Marchesi, Nicolò Marchetti, A Babylonian Official at Tilmen Höyük in the Time of King Sumu-la-el of Babylon, p. 5)

Paul-Alain Beaulieu assumes that the shift in Usur-amassu’s gender had something to do with her introduction to Uruk and subsequent incorporation into the court of Inanna, and that accordingly the name came to be understood as “obey her (ie. Inanna’s) command)”, though he doesn’t pursue this point further (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229).

One might be tempted to wonder if perhaps the situation has something to do with Inanna’s oft cited association with change of gender (or at least of gender roles). I personally find this implausible. As I already discussed in the first article from this cycle, in sources which were contemporary with Usur-amassu’s arrival in Uruk this ability tends to be invoked in a highly specific, negative context. “May she change him from a man to a woman” and similar formulas appear as a penalty for oathbreakers in royal inscriptions and treaties, as first attested during the reign of Tukulti-Ninurta I. The aforementioned formulas constitute a threat of the loss of a very specific sort of performative masculinity associated with "heroism" or martial valor. More broadly the threat of a change of gender also reflects the fear of a loss of autonomy, something generally tied to masculinity in everyday life in ancient Mesopotamia (Gina Konstantopoulos, My Men Have Become Women, and My Women Men: Gender, Identity, and Cursing in Mesopotamia; Ilona Zsolnay “Goddess of War, Pacifier of Kings”: An Analysis of Ištar’s Martial Role in the Maledictory Sections of the Assyrian Royal Inscriptions).

This is not really a good parallel to Usur-amassu's mysterious "transition". Perhaps most importantly, every single reference to it has humans be affected by the reversal, not gods. There is also no evidence that Usur-amassu was perceived negatively - in contrast with anyone who would hypothetically break a royal oath. Furthermore, nothing really indicates that her role changed alongside her gender. In An = Anum and the incantation series Šurpu the male version is grouped with his brother Misharu (“justice”) and Ishartu (“righteousness”); the sources pertaining to the feminine version from Uruk similarly portray her as a deity of justice, “who renders judgment for the land”, essentially a divine judiciary clerk (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 229). In contrast with martial valor, as far as deities go this role is pretty clearly not really tied to masculinity - or femininity, for that matter (for an overview of judiciary deities and their perception see Manfred Krebernik, Richtergott(heiten) in RlA vol. 11). The change of gender also seemingly didn’t impact Usur-amassu’s preexisting connections, as an inscription from Uruk dated to the reign of Nabonassar explicitly refers to her as a daughter (bukrat) of Adad (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 228).

It’s unclear how Usur-amassu was introduced to the local pantheon of Uruk, but evidently she won over the inhabitants of Uruk pretty quickly. In the Neo-Assyrian period she was one of the deities representing the city during coronations of Assyrian rulers (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). In the following Neo-Babylonian period she was one of the five main deities of the city, next to Inanna/Ishtar, Nanaya, Urkayitu (“the Urukean”, an epithet of Inanna turned into a personification of the city) and Bēltu-ša-Rēš (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 179). Thanks to Usur-amassu’s reasonably prominent position in the pantheon of Uruk, she is well represented in the Eanna archives, which document assorted paraphernalia prepared for statues representing her (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 230-244). As a curiosity I feel obliged to point out that in one case a necklace belonging to Usur-amassu was loaned for a festival of Dumuzi (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 335-336). Alas, this evident prominence is not really reflected in publications aimed at general audiences, let alone in popculture. Last attestations of Usur-amassu come from the period of Seleucid rule over Mesopotamia. She retained a degree of importance in Uruk, as expected (The Pantheon of Uruk…, p. 227). The Eanna actually didn’t exist anymore, but like other deities associated with it she was simply moved to the freshly built Irigal instead (The Revival…, p. 90). Regardless of whether the shift in her gender had anything to do with the primary denizen of both temples, evidently their association was close enough to keep Usur-amassu afloat for the final few centuries of the city’s history.

Postscriptum

This article was initially intended as a pride month special in… 2023? Possibly earlier? I ended up abandoning its original form for a time, and eventually cannibalized its two most major sections, dealing with Shaushka, Ninsianna and Pinikir, for the recent article about Inanna, deities associated with her, and gender. I couldn’t just discard the rest, though, and now you can finally read it all. Much of the information is already on wikipedia through my long term efforts, but now it’s also accessible here, with some extra speculation as a bonus. While this is ostensibly a pride month special, technically none of the sources discussed are really focused on lgbt matters, unless you squint really hard at the two unusual passages I brought up in Dumuzi-abzu’s section. However, I still think the topic of deity gender changes is interesting - if nothing else, it shows that gender was no less malleable than any other aspect of a deity’s character under the rain circumstances. And the process cannot always be neatly explained.

Furthermore, nothing really prevents one from trying to rationalize the changes as a reflection of the respective deities’ identities in a work of fiction featuring them. It’s important to remember that Mesopotamian gods were reinterpreted to meet the needs of new audiences many times, with contemporary institutions, social phenomena or geopolitical developments projected back into the mythical past, especially in literary works (attributing downfall of legendary rulers to insufficient devotion to Marduk is particularly funny, seeing how late his rise to prominence was). Trying to condense Lisin’s puzzling history into something coherent and making him a trans man in the process would thus, arguably, be just a modern example of a similar phenomenon. As long as you don’t alter the content of the actual historical sources, this sort of playful engagement with the material seems more than fine.

47 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Ball Game of Mesoamerica

The sport known simply as the Ball Game was played by all the major Mesoamerican civilizations and the impressive stone courts became a feature of many cities. More than just a game, it could have a religious significance and featured in episodes of mythology. Contests even supplied candidates for human sacrifice and became literally a game of life or death.

Origins

The game was invented sometime in the Preclassical Period (2500-100 BCE), probably by the Olmec, and became a common Mesoamerican-wide feature of the urban landscape by the Classical Period (300-900 CE). Eventually, the game was even exported to other cultures in North America and the Caribbean.

In Mesoamerican mythology the game is an important element in the story of the Maya gods Hun Hunahpú and Vucub Hunahpú. The pair annoyed the gods of the underworld with their noisy playing and the two brothers were tricked into descending into Xibalba (the underworld) where they were challenged to a ball game. Losing the game, Hun Hunahpús had his head cut off; a foretaste of what would become common practice for players unfortunate enough to lose a game.

In another legend, a famous ball game was held at the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan between the Aztec king Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin (r. 1502-1520 CE) and the king of Texcoco. The latter had predicted that Motecuhzoma's kingdom would fall and the game was set-up to establish the truth of this bold prediction. Motecuhzoma lost the game and did, of course, lose his kingdom at the hands of the invaders from the Old World. The story also supports the idea that the ball game was sometimes used for the purposes of divination.

Continue reading...

178 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everything You Need to Know About Crystals: Tiger's Eye

Tiger's Eye (The Stone of the Sun)

Color: Golden Yellow with Brown

Hardiness: 7

Rarity: Easy to Obtain

Type: Metamorphic

Chakra Association: Sacral, Solar-Plexus, Third Eye

Deities: Ra, Sekhmet, Durga

Astrological Signs: Capricorn, Leo

Element: Earth, Fire

Planet: Sun

Origin: India, Myanmar, South Africa, USA, Mexico

Powers: The Sun, Protection, Abundance, Luck, Pride, and Justice

Crystals It Works Well With: Cat’s Eye, Chalcedony, Topaz

How It is Created: Tiger’s Eye is basically a quartz but they formed in such an unusual way that the fibers of the mineral called crocidolite are laid down in parallel bands within the structure. This creates its silk like appearance and its “cat’s eye”.

History: Tombs in the ancient city of Ur in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) dating back to 2500 BCE have yielded gold sets with agates, like tiger’s eye and carnelian. The tiger’s eye was very popular due to the belief that it harnessed the power of the earth and the sun. This is why it is associated with the god of the sun, Ra and why Egyptians considered it a very valuable gem. Roman soldiers believed that the tiger’s eye was a symbol of bravery and would ride with pieces of tiger’s eye on them in order to encourage bravery during battles.

What It Can Do:

Shields the energy field or aura from negativity

Clears tension and mental blocks from the solar plexus

Can soothe, calm, and restore one’s body and mind

Banish the evil eye and curses

Attracts money while curbing impulsive spending

Used to detect liars and deceptions

Can increase confidence and pride

Placing it on your third eye can help enhance psychic abilities and balance your lower chakras

Helps unlock and unleash your true desires

Alleviates depression and lifts moods

Reduces crabbing and addictive behavior

How To Get the Best Out of Tiger’s Eye: Wear it in bracelet or amulet form.

How to Cleanse and Charge:

To cleanse: Lay it on a windowsill where the sun shines the most or bury it in your garden where the sun shines the most

To charge: You can also charge it on the windowsill with the sun. The sun really gives it a great charge, especially if one of the deities you work with is a sun god.

Crystal Grid:

Abundance (Spiral)

Base for the grid, such as wood, slate, fossilized wood, or golden card or cloth

Citrine

Goldstone

Green Aventurine

Herkimer Diamond

Jade

Moss Agate

Ruby

Tiger’s Eye

Topaz

If you’re laying a preparatory “cleansing” spiral, start at the topmost point and lay crystals alternately, with the points pointing out from the center.

Place the Goldstone in the center as the keystone.

If laying an abundance grid, begin by placing the Goldstone in the center, stating that your intention is for it to bring abundance into your life.

Lay a spiral of alternated crystals, pointing down and inward, until you reach the Goldstone.

Add a grounding stone if appropriate.

When the grid is no longer required, dismantle it.

Sources

#tiger's eye#witchblr#witch community#witchcraft#paganblr#egyptian mythology#crystals#occulltism#baby witch#witches#witch tips#witch tumblr#witch resources#magick#witches of tumblr#witchcraft resources#witch blog#beginner witch#geology#gemstones

416 notes

·

View notes

Text

Conceptualising 10,000 Years

Yes, this is another post about how the ten-thousand-year-old primordial saints of the Resurrection are, indeed, very old. But the tricky thing about human minds is that they're really bad at comprehending massive numbers. So, in this post, I hope to give you, my dear reader, an understanding of what it means to be ten thousand years old.

Let us imagine, just for a moment, that today (28 August, 2024) marks the close of the myriadic year of our Lord–that far-off King of Necromancers, that blessed Resurrector of Saints!–and the Lyctors reach ten thousand years old today. From this premise, I believe we can better grasp just how old these people are, since we can timeline their lives based on real-world events. So, without further ado...

8000 BCE - The Great Resurrection. Earth is still experiencing the last great Ice Age. Woolly mammoths are still thriving, and, according to some estimates, the last of the smilodon and American lion species still lives. HS Sapiens are still in the Stone Age. Earliest records of ovens used for pottery.

7700 BCE - Lyctors reach 300 years old. Farmers first domesticate wheat in the area now known as Mesopotamia. Humans have yet to develop advanced agricultural technology, instead relying on very primitive methods.

7000 BCE - Lyctors are now 1000 years old. Domestication of goats in Mesopotamia.

6700 BCE- Lyctors are 1300 years old. Domestication of pigs in Mesopotamia.

6200 BCE - Lyctors are 1800 years old. The Bronze Age begins! Earliest evidence of the smelting of bronze dates back to roughly 6200 BCE in Asia Minor. With the advent of bronze, humans are able to make more effective and more durable tools.

6000 BCE - Lyctors are 2000 years old. First settlements along the Nile River

5500 BCE - Lyctors are 2500 years old. Earliest evidence of Ancient Sumer.

5000 BCE - Lyctors are 3000 years old. Major agricultural developments occurred around this time, including the first evidence for the usage of irrigation.

4000 BCE -Lyctors are 4000 years old. Extinction of the Woolly Mammoth. Humans develop the first cities around this time, and wool is first used as in textiles.

3100 BCE - Lyctors are 4900 years old. Construction on Stonehenge begins. Recorded history emerges around this time. The rise of Ancient Egypt begins. Earliest cuneiform texts date back to this time.

2334 BCE - Lyctors are 5666 years old. Sargon of Akkad is King of the Akkadian Empire.

2154 BCE - Lyctors are 5846 years old. Akkadian empire dissolves after less than 200 years wow!

2000 BCE - Lyctors are 6000 years old. Ancient Minoan civilization begins.

1341 BCE - Lyctors are 6659 years old. Birth of King Tut.

1250 BCE - Lycors are 6750 years old. Ancient Chinese and Ancient Olmec civilization begins.

800 BCE - Lyctors are 7200 years old. Start of the Classical Period.

500 CE - Lyctors are 8500 years old. End of the Classical Period. Sorry, too lazy to write all of it out. Plus, there's a billion resources on it.

900 CE - Lyctors are 8900 years old. Start of the Dark Ages.

1492 CE - Lyctors are 9492 years old. Planning of Dios Apate Major begins around here in the Locked Tomb timeline. Columbus "discovers" the Americas (and proceeds to slaughter indigenous peoples)

2000 - The myriadic year of our lord.

I hope you understand how old these people are. DISCLAIMER: Not a historian. Do not claim to be. These dates are from cursory research and could be inaccurate. Furthermore, this is nowhere near a complete account of human history, especially towards the end, when I got really bored.

Ty <3

135 notes

·

View notes