#Alexander vulgate

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

🗡️ Character specific recs: GALAHAD🗡️

Download/video texts are linked beside titles if present. This is just a list of what I think is the best Galahad material out there. Every list is favorite order.

Novels

Blessed Bastard: A Novel Of Sir Galahad (Lehmann)

Lancelot and Guinevere (Douglas)

Believe (Victoria Alexander)

The Warlord Chronicle (Cornwell)

Camelot. L'invenzione della Tavola rotonda (Buongiorno)

Chivalry (Gaiman and Doran)

The Forever King Trilogy (Cochran)

Galahad: Enough of His Life to Explain His Reputation (Erskine)

The Book of Galahad (Susan Cook)

Texts

Morte d'Arthur (Malory)

Vulgate and Post-Vulgate

Cantare del Falso Scudo (summary)

Videogames

The bastard of Camelot (itch io)

Movies

1975 Monty Python and the Holy Grail (youtube)

2014 Dragons of Camelot (queer-ragnelle list)

2021 Fate/Grand Order: Camelot Part 1 and 2 (queer-ragnelle list)

2004 King Arthur (queer-ragnelle list)

Tv shows

1949 The Adventures of Sir Galahad (queer-ragnelle list)

2014 The Librarians

1979 The Legend of King Arthur (queer-ragnelle list)

Other

Episode: Good Knight MacGyver (MacGyver s07e07-s07e08)

Album: High noon over Camelot by The Mechanisms (youtube)

Album: The once and future king by Gary Hughes (youtube)

Album: Galahad Suite by Johansson (spotify)

Song: Galahad by Josh Ritter (youtube)

Musical: Spamalot

Poem: The Quest of the Sancgreal Galahad (Camelot project)

Art used from Tanno Shinobu's "Eien No Zanshou" artbook. Not Galahad, but he looked very Galahad-like.

#characters recs#galahad#sir galahad#arthurian#arthurian legend#recs#books#that art is not galahad or arthurian but any excuse for tanno shinobu art#resource#resources

50 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hello! As someone who is still new to learning about Alexander the Great I'm trying to learn more about him by reading the actual ancient texts, one of whom is Aelian. I've been told that Aelian isn't a trustworthy source for learning about Alexander, is this true?

Historians of Alexander the Great

I suspect there is some name confusion here.

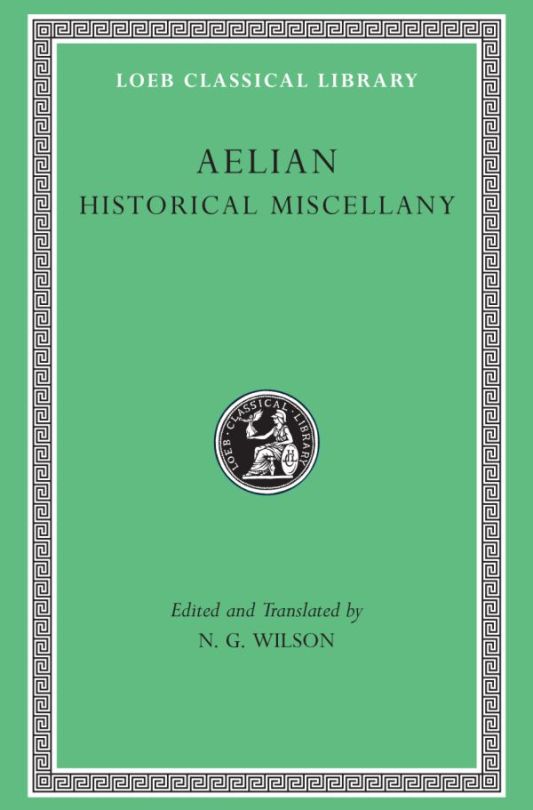

Aelian is an ancient author, and his work the Varia Historia does mention Alexander, but not much, relatively. The Loeb Classical Library translated it in 1997 (before that, it was only in Greek, which is how I first encountered it when I used it for my dissertation). His more popular On Animals (5 vols.) has been available in English for a while. So I'm thinking this probably isn't the author you mean.

Claudius Aelianus wrote in the 3rd century; he's best known in Alexander fandom circles as one (of two) authors (Epictatus in Arrian is the other) who frankly claims Alexander was Hephaistion's lover (erastes). But because it's late, and even in antiquity he was, as the Loeb library charmingly calls him, "light reading" for Romans, he can't be given a lot of credit. E.g., dramatic exaggeration was the stock-in-trade of his style of writing.

Now, who I think you actually mean IS the Arrian mentioned just above: The Anabasis of Alexander. He's probably the most popular ancient author on Alexander, although Plutarch rivals him because Plutarch's Life of Alexander is both shorter and has more colorful stories. Arrian is also often cited as the most reliable Alexander historian, and that's not wrong...for some things (particularly details of military campaigns). But he's also not always right and the so-called "vulgate" of (at least) Diodoros and Curtius should, imo, be read for correctives and things Arrian glosses/doesn't want to talk about.

If I had to give someone a single ancient history on Alexander, it would be Arrian. That said, I wouldn't give just one. I really do suggest you read all four of the major ones (Justin is a crap-shoot, honestly).

For more on the Big Five, as I call them, this video might be useful. (And part of why I made them! Now I can just point and say, "Go there.") It even includes suggested translations.

youtube

In fact, the entire playlist called "Introducing the Sources on Alexander and ancient Macedonia" might be of use, if you've got the time. The one linked above is actually the longest at about 32 minutes. The rest are all under half an hour, and a couple under 15 minutes.

youtube

#Alexander the Great#Arrian#Aelian#Classics#historians of Alexander the Great#ancient Greece#ancient Macedonia#Plutarch#Curtius Rufus#Diodoros#Justin#asks#tagamemnon

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Didn't want to hijack this post here by talking about something maybe 3 people are interested in, so I decided to make it separate:

Fun fact on this ficverse wherein I overthink the worldbuilding and add to it with a lifetime of archaeological upbringing and two degrees in human studies (geography and anthropology): The characters speak a lingua franca, vulgate Lonkan, because the Lonkan Empire spanned a huge amount of space (conservative guessing: Gohn to Jacole to Crescent Island) and was the most advanced civilization at the time. Model: Koine ("common") Greek became a lingua franca because of Alexander the Great's campaign of expansion. Do they remember that it's Lonkan? No, not really; Lonka fell a few centuries before the present and by present the language became known as the trade language.

Galuf took to Lonkan well 30 years back because Lonkan and Surgatese had the same roots, and there had been concentrated efforts to keep both languages pure. Plus, he had about 30 years to perfect his mastery of it by game start, because some part of him knew he'd have to go back.

Anyway, here's a thing I made up about a year ago for my worldbuilding project.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

You're not alone. I also tend to think of Arthur as a Warlord fundamentally rather the Idealized Ruler figure hyped in Modern retellings. His real titles from the stories are "Dux Bellorum (War Duke)" "Red Ravager" "Ameraudur (Emperor/Imperator, a military title originally)" and "King of Adventure". Doesn't really paint a picture of a person who ruled peacefully and stably.

It helps that there are elements of his medieval characterization that do not jive with Modern sensibilities. For example, "The Conquest of Europe" - his invasions of Norway, Gaul, Denmark, etc. - in the Chronicle Tradition, as well as his Sexual escapades in the Romances.

It's also pointed out by Guinevere's Mom in Awntyrs off Arthure in Tarn Weddling that his primary failing is his covetousness.

In Le Morte D'Arthur, Malory justifies - and dismisses as "mischief" - Mordred's Revolt as a result of the Common people fed up with Arthur's rule as having been nothing but constant war and only found peace during Mordred's tenure. Which, ironically, perfectly describes the Arthur of the original non-romance narratives

When it comes down to it, King Arthur is really more alike his fellow "Nine Worthies" - Alexander, Julius Caesar, David and Charlemagne - than not.

EDIT: On the flip-side, Geoffrey of Monmouth does say in his Chronicle that there was 20 year period of relative peace inbetween the Battle of Badon Hill and the beginning of Arthur's Conquest. So there's that.

EDIT2: I HAD JUST REMEMBERED: There is a moment in Vulgate Cycle (at the beginning of Lancelot pt. II) where, during the War with Galehaut, a random hermit comes along to scold Arthur for his misfortunes and teach him how to be a christian good king to get back in God's good graces. lol

I believe whole heartedly that Arthur was not a good king, he was brought up to be a soldier, a knight, a second son. He probably would not have had a high quality education in administration, unlike Kay the firstborn, and so when he becomes King of Britain he would have been horribly unprepared. Was Arthur a great soldier? Yes. Was he a great king? Probably not.

#king arthur#arthurian romances#arthurian chronicle tradition#arthuriana#arthurian legend#welsh mythology#arthurian legends#le morte d'arthur#nine worthies#historia regum britanniae#geoffrey of monmouth#vulgate cycle

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alexander is but a single creature, and a headstrong and crazy one Quintus Curtius 4.14.18

#you know what? fuck you! *Vulgates your Alexander*#for someone who works with horses everyday I sure don't remember what they look like#tagamemnon#ancient macedonia#alexander the great#ancient greece#classics#my art#don't expect much art from me I do like two drawings a year

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

duality of Alexander the great sources

justin: he murdered everyone in sight including my whole family. an inhuman monster, parasite, with no feelings. would probably kill u over bad posture. cleitarchus told me so

vs

aristoboulos: ✨alexander✨ is the love of my life and never did anything wrong. if he got upset it was probably bc of someone else, maybe a prophet. based on very unbiased self reporting

#the vulgates make my day they rlly went for it#curtius is excluded bc i love him#Alexander the great#greek history#macedonian history#alexander iii#philip ii#i hate u justin keep that in mind#dumbass

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Translation History

by Alexander Campaña

Throughout the history of translation, there have been several crucial translators who have contributed to this field. Do you know some of these essential characters? If you do not know them do not worry, you are going to know them right now!

St. Jerome

Eusebius Hieronymus, or St. Jerome was born in what is known today as Croatia, his mother tongue was Illyrian, however, he was fluent in other languages, such as Greek, Aramaic, Syriac, Arabic, Hebrew, and Latin.

St. Jerome strongly believed that translation should be equal in meaning and style. He “was one of the first notable translators to translate sense for sense rather than word for word” (Faulwetter, 2018). Therefore, he was a pioneer in the field subsequently named “dynamic equivalence”.

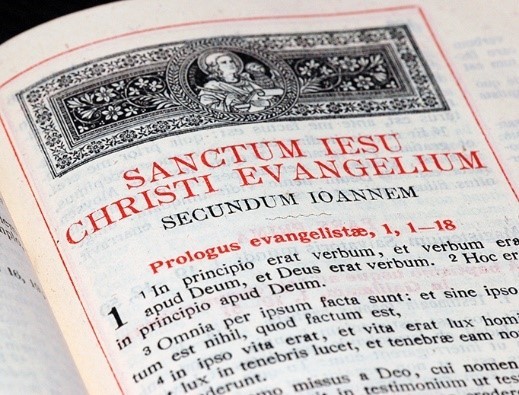

One of his most important contributions is translating the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into Latin, which until these days remains the standard Latin version of this holy book and is known as Vulgate.

Vulgate was controversial due to it was the first translation that was not done using a literal translation, but by sense for sense. Additionally to that, “Vulgate relied heavily on the cross-reference of the original Hebrew text- which many Christian scholars at the time ironically believed “tainted” the religion with Judaism” (Faulwetter, 2018).

St. Jerome passed away on September 30, thus the celebration of the International Day of Translators takes place on that date.

Constance Garnett

Constance Garnett was born on December 19, 1861, in Brighton, England. In a time when high-level education for women was rather uncommon, she won a scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge, where she graduated and studied Latin and Greek. Constance married in 1889 to the critic Edward Garnett, who encouraged her to learn Russian.

Soon after, in 1892, she started her career as a translator by translating Russian works for publication by Leo Tolstoy and Ivan Goncharov. In one of her travels to Russia, she met Tolstoy, who asked her to translate his religious works, but Garnett refused as her main goal was to translate novels.

Constance was the translator who took the responsibility for translating the great works of Russian literature into English. She made works from Tolstoy, Goncharov, Gogol, Dostoyevsky, Ostrovsky, Herzen, Turgenev, and Chekhov available to English-speaking readers in the 20th century. She died on December 17, 1946.

Fun fact: “When Constance Garnett did not know the translation of a particular word or phrase, she would sometimes leave it out altogether” (Moser, 1988).

Natasha Randall explores the task of biographical research into the figure of the literary translator Constance Garnett. This talk attempts to figure out some details about the interior life of this magnificent translator, addressing questions, such as the following: Can her translations provide additional insight into her life and character? What are the detectable choices in Garnett’s work that can contribute to a portrait of her?

We can assure you that you will not regret watching this talk! Have a look at it by clicking on this link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vbIZMzCVz8U

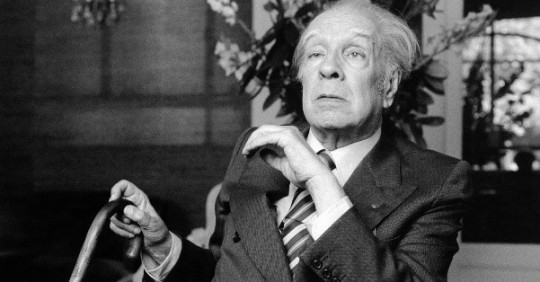

Jorge Luis Borges

Borges was one of the most proficient, successful, and famous Latin-American writers and poets. He has massively contributed to the field of translation, even though he never worked for an official translation agency.

Since Borges was little, he was surrounded by foreign languages, at home he spoke English and Spanish, and, later, learned German and French. His reading was done mainly in foreign languages, focusing mainly on English texts.

“For Borges, Translation was not about transferring a text from one language to another, but rather to transform one text into another” (Mermoud, 2015). He stated that translation, even literal ones, changes their meaning due to the inherent changeability of texts according to the reader and to the place and time of reading.

This translator believed that high-quality translations could enrich or improve the source text since it provides, to any type of text, nuanced meaning, connotation, and association. According to Mermoud (2015), “Borges enjoyed leafing through different translations of the same text, often as a literary exercise, maintaining that any changes in linguistic code were encouraged in his opinion and at times necessary”.

Borges’ translation method/philosophy goes along with the belief that the work itself is “ultimately more important than its creator”. In that sense, Borges applied his own translation method which consisted of eliminating redundant or unnecessary elements in the source text, removing what he called “textual distractions” and adding nuance, or changing the tile, among other things. Borges is responsible for some of the best and most beautiful writings as well as translations.

Do you want to check one of his translations? Below you will find his translation into Spanish of a Whitman poem.

SONG OF MYSELF

I celebrate myself, and sing myself,

And what I assume you shall assume,

For every atom belonging to me as good

belongs to you.

Whitman

CANTO DE MÍ MISMO

Yo me celebro y yo me canto,

Y todo cuanto es mío también es tuyo,

Porque no hay un átomo de mi cuerpo

que no te pertenezca.

Translated by Jorge Luis Borges

Edward George Seidensticker

Edward Seidensticker was a translator, Japanologist, historian, author, and educator who was born on February 21, 1921, in Castle Rock, Colorado. His family had some financial struggles, which is why he attended the University of Colorado at Boulder and graduated with a degree in English in 1942.

His first approach to Japanese language and culture began during World War II, while he was accompanying the U.S. Marines ashore at Iwo Jima in his capacity as a language officer. Since then, his passion for the language has only increased.

Seidensticker traveled to Japan to work as a foreign service officer of the United States. Afterward, he decided to study Japanese literature at the University of Tokyo and focused on the modern side of literature. In the middle of the 1950s, he worked as a lecturer of both American and Japanese literature at Sophia University. “While there he became acquainted with some of Japan's most revered authors and began translating their masterpieces for American readers” (Fox, 2007).

During his lifetime, Seidensticker translated more than a hundred literary Japanese works, making able for English speakers to read authors, such as Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima, among others. He is considered one of the best Japanese literature translators due to his capacity to convey the same nuances and emotions that are portrayed in the source text.

In 1971, Edward won the National Book Award in the category of Translation for his version of Yasunari Kawabata’s “The Sound of the Mountain”.

His edition of “The Tale of Genji”, an 11th-century epic of love and intrigue written by Murasaki Shikibu, was praised by critics. This translation took Seidensticker more than ten years. Sadly, he died on August 26, 2007, in Tokyo, Japan.

Now you know some of the most important, famous, and proficient translators in history. There is a long list of people worth mentioning, so why not? Comment below other translators that we should talk about in the next post!

Salto de página

References:

Costa, W. C. (1996). Borges and Textual Quality in Translation. Cadernos de tradução, 1(1), 115-135.

Faulwetter, K. (2018, February 28). St. Jerome and the First Sense-for-Sense Method in Translation Studies. Motaword. https://www.motaword.com/blog/st-jerome#:%7E:text=Jerome%20coined%20the%20field%20phenomenon,than%20%E2%80%9Cword%20for%20word%E2%80%9D.

Fox, M. (2007, August 31). Edward G. Seidensticker - Obituary. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/08/31/arts/31seidensticker.html

Mermoud, M. (2020, September 9). Stories of translators: Jorge Luis Borges. Cultures Connection. https://culturesconnection.com/stories-of-translators-jorge-luis-borges/

Moser, C. (1988). Translation: The achievement of Constance Garnett. The American Scholar, 57(3), 431-438.

Nguyen, M. (2005). Prologue of the Gospel of St. John from the Clementine Vulgate [Photograph]. https://publisher-publish.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/pb-ncregister/swp/hv9hms/media/20200828040816_5f4868edc2bf74d8cce1d2ecjpeg.webp

Panetti, D. (1500). Saint Jérôme [Saint Jérôme]. Abbaye de Chaalis - Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, France. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/38/Domenico_Panetti_-_St_J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me.jpg/467px-Domenico_Panetti_-_St_J%C3%A9r%C3%B4me.jpg

#dark acamedia#translation#language#linguistics#light academia#culture#writing#writerscorner#learning#literature#interesting

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Not to mention the man identified as Igraine's first husband and Morgan's father, Gorlois, himself probably grew out of one of Uther's other epithets, Gorlassar

Right?!! I'm also convinced of that theory. (Just look at Vulgate, Ambrosius gets renamed "Pendragon" just so Uther can take it later)

It's like... Geoffrey of Monmouth awkwardly shoving in a Zeus-style mystical rape (inspired by the Matter of Rome w/ Alexander) so that Arthur can be a demigod... in a Christian setting.

Also is the fact that Arthur had one sister originally - Anna, who later becomes Morgause.

In the context of Arthurian legend (and just legend, not history), who best fits as the narrator of "The Elegy of Uther Pendragon"? The dying and maybe decapitated Uther? Certainly the poem is written in a first-person POV, and as Uther is considered an enchanter in Welsh mythology, it's not out of the question for him to sing his own death-song. Or is it Taliesin, as the song is found in his collection of poetry?

It's pretty much Uther that's saying his elegy. There's a line there saying "... My tongue turns to declaim my elegy..."

It really wouldn't unusual for Uther to compose poetry, although to do it while dying and also having the balls to say that you're several times better than your son is infinitely amusing.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

The mysterious skull of Gian Lorenzo Bernini was found in Dresden

The story is intricate and made even more intriguing by the subject of the work that is the protagonist. A life-sized human skull carved from Carrara marble, made in ways so lifelike that it can be mistaken for a real human skull. Pope Alexander VII commissioned it in 1655 for his desk: the vulgate said to Gian Lorenzo Bernini, but then for centuries the sculpture disappeared, and the attribution could never be confirmed. The work was part of the Chigi Collection, then it was purchased in 1729 by the Elector Augustus the Strong of Saxony. Now it has been found almost by chance among the funds of the Dresden State Art Collection (Skd), not catalogued as a work by the Italian artist.

(Guido Ubaldo Abbatini, Pope Alexander VII with Bernini's skull, 1655)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Plutarch’s Biography and its Purpose

The aims of the modern historian were not necessarily shared by the ancient. Values change and the modern emphasis on objectivity and impartiality—which in itself is an impartial desire—was for many Roman historians replaced by an emphasis on morality and character. For Plutarch, who considered himself a biographer and not a historian at all, this was particularly true. As he famously wrote, “I am writing biography, not history, and the truth is that the most brilliant exploits often tell us nothing of the virtues or vices of the men who performed them ….” Plutarch may have meant this as indicative of his Lives as a whole, or perhaps just this particular example. Either way, Plutarch was interested in the morality of Alexander, and in examining whether his morality was a driving force behind his success. As Barton said, “Plutarch’s lives are linked to an explicit moral programme: of improvement by impressing on his readers the importance of political arête, excellence.” In painting his portrait of Alexander, Plutarch clearly had decided that Alexander’s character was, for the most part, praiseworthy. It may not be possible to say with certainty that Plutarch, writing in late 1st and early 2nd century CE, was defending Alexander against this tradition. Plutarch’s rendition was not pure apology,—he did in fact record some of Alexander’s ignoble deeds—but he did chose to portray Alexander in a largely a positive light. Considering that he was certainly aware of the vulgate tradition and that many of the previous works had a far more negative stance, it is very likely it seems likely that he was, to some degree, consciously defending Alexander.

Plutarch plotting.

The vulgate tradition, for all that it is considered the “bad” perspective, remains Hellenic-centric and does not truly defile the memory of Alexander. There is an emphasis on his debauchery and of the alienation and murder of some of his men, but the slaughtering of thousands of barbarians and razing of cities is not nearly as emphasized as one might expect from what is considered the negative tradition. Nonetheless, the extant sources do show that by the first and second century CE Alexander had become at best a controversial figure. A look at some of more prominent critiques of Alexander should help to establish the tradition that Plutarch broke from with his interpretation.

Many of the writers that preceded Plutarch had been critical of the Macedonian King, and Plutarch’s portrait broke with recent tradition. Diodorus Siculus, Curtuis Rufus, and possibly Trogus, working at least partially with the tradition of Cleitarchus, certainly portrayed Alexander in a largely negative light.

Not this negative though

Cleitarchus, who may have been reacting to Callisthenes’ official version, is credited with beginning the Vulgate tradition. He may not have been held in high regard by the later historians and rhetoricians, but his influence was undeniable. Diodorus, writing in the first century BCE, was not a mere compiler as has been suggested, but his Biblotecha Historia—especially book 17—is rife with inconsistencies and falsehoods. Trogus, from the little that can be glimpsed via Justin, likely wrote during the reign of Augustus, may have been a good historian but he must be judged through the filter of his epitomater and he suffers greatly from Justin’s distortions. Curtius Rufus, who likely wrote in the first century CE under Claudius, seems to be a more discerning historian, but suffers from the Roman affliction of overemphasizing morality and his work is, like Plutarch’s, more literary than historical. These works differ in content and quality, of course, but share a similar view of Alexander. He is portrayed as cruel and also lucky—Justin suggests the Battle of Issus was not won because of his strategy but due to a fortuitous chance of the battlefield, and attributes the victory at the Siege of Tyre to a mysterious, unnamed act of treachery. Justin also provides examples of Alexander’s ruthlessness, claims he bribed the priests of Zeus-Ammon to proclaim his divinity, and as being a malignant threat to his army and supporters Finally, Cleitus’s death is portrayed to show Alexander in as bad a light as possible. Curtius states a similar opinion—that Alexander was overwhelmed by good fortune.

Another, even more disparaging, perspective was held by the Stoics, as shown in the works of Seneca the Younger and his protégé Lucan. Seneca scorned Alexander as a tyrant of the worst sort, on a par with Cyrus and Cambyses. Seneca repeats his attacks on Alexander in various works, notably in the De Clementia 1.25.1, De Beneficiis 1.13.1, 2.16.1, 5.6.1,and Epistle 119. Seneca’s nephew Lucan, for his part, portrays Alexander in a highly negative way as well. Though not a Stoic, Livy’s famed digression provides an earlier, equally disapproving assessment of Alexander as well.

This, then, was the backdrop when Plutarch chose to write. He used many sources, 24 he himself cited[19]. While Plutarch does seem to have relied on Cleitarchus as one of his many sources, it is clear that he did not appropriate the historian’s bias along with his facts. It is not certain he was deliberately defending Alexander against Cleitarchus and Vulgates, there are times that he does indeed seem to be doing just that. Plutarch wrote of the Battle of Issus: “Fortune certainly presented Alexander with the ideal terrain for the battle, but it was his own generalship which did most to win the victory.” This may have been a response to the Vulgate claim that Alexander’s luck was responsible for his victories. Perhaps the only certainty is that a debate concerning Issus only mentioning terrain and Alexander’s generalship as possible factors in the outcome leaves excludes too many aspects—for instance, Persian dissension, Alexander’s own generals, or Philip’s über-weapon the sarissa—to claim accuracy. Likewise, chapter 28 seems to be at least a partial attempt to refute the Stoic charge that Alexander’s belief in his own divinity was a sign of his delusions of grandeur.

Plutarch does descend—at times—into something close to apology. His claims that Alexander never slept only with Barsine before his marriage to Roxanne seems an anachronistic attempt of Plutarch’s morality thrust upon his subject. Worse still is the claim that:

Alexander was also more moderate in his drinking than was generally supposed. The impression that he was a heavy drinker arose because when he had nothing else to do, he liked to linger over each cup, but in fact he was usually talking rather than drinking: he enjoyed talking rather than drinking….

These tendencies are coupled with attempts to justify Alexander’s megalomania and, related the tale of Alexander lighting his servant with naptha and nearly burning him alive with nary a comment on the underlying cruelty. He is certain that

“Alexander was by nature exceptionally generous and became even more so as his wealth increased.” In the struggle between Alexander’s ambitions and his soldiers desire to return home, Plutarch portrays the soldiery as ungrateful: “They found his expeditions and campaigns an intolerable burden, and little by little went so far as to abuse and find fault with the king.” He later describes their actions as full of “baseness and ingratitude.” The overall picture is of a great man, whose occasional flaws detract neither from his achievements or his morality. His tendency was to emphasize Alexander’s successes—as opposed to Arrian, for instance, who for obvious reasons stressed Ptolemy’s contributions.

The statement that Plutarch is not a completely trustworthy source is obviously a truism. The Greek biographer at times at times relied on dubious sources, such as the ephemerides that he felt trumped all other sources. His versions of the battles are atrocious: Hamilton notes that “It is safe to say that we could not understand any of the battles from Plutarch’s narrative.” Because of his well-documented methodology, Plutarch was able to choose stories completely at his whim. If an anecdote was not to his liking, or did not fit into his argument, it would be easy to leave it out as not fitting his criteria. This was shown most famously when accepts the tradition that Solon met Croesus despite the fact that it was temporally impossible. In Alexander, the examples of Philip the Acarnanian’s supposed poisoning attempt, the so-called plotting of Philotas, and the Page’s Consipiracy are “significant for Plutarch’s view of the development of his [Alexander’s] character…his actions are almost always direct and open.” His aims were not what a modern historian—or even biographer—would prefer. Life of Alexander does not address many of the questions raised by the other sources but instead “with the question whether Alexander’s achievements were due more to good fortune or to his own character” (Barrow 121).

This results partially from the difference between biography and history, but this does not provide a complete explanation of Plutarch’s deficiencies. Hamilton complains that even as a biography of Alexander the Life is inadequate,” noting that battles, future plans, and overall administration are glossed over or left out entirely. Plutarch was not, however, interested in the workings of the Alexandrian government or detailed battle tactics. His biography examined Alexander’s character and morality, and though he found Alexander succumbed at times to anger and pride, the ultimate assessment was that Alexander was worthy of the praise heaped upon him. Plutarch’s comments about biography are perhaps over-emphasized. Just as Curtius’ work should not be dismissed because of the famous dictum plura transcribe quam credo, Plutarch’s Life has historical value despite his assertion that he was not, in fact, writing history.

Even Alexander’s harshest critics were not without praise. Arrian, perhaps Alexander’s least critical chronicler, does not refrain from the occasional negative about his subject. Plutarch is more balanced than Arrian, though he used his sources selectively, to better try to prove that power corrupted Alexander absolutely. On the other side, even Justin/Trogus were not without some positive feedback on the Macedonian king. As Pearson (241) has noted:

The mistake has commonly been made of trying to divide Alexander’s historians into two classes, favourable and unfavourable. The distinction is a false one… the evidence indicates that they were not particular about the consistency in characterization.

The dichotomy is not, however, entirely false. The tradition surrounding Plutarch in his lifetime, regardless of when he actually wrote his Lives, was largely negative. Plutarch broke from this tradition but does not seem to have influenced many to follow in his footsteps. Perhaps that was not his intent. Duff (65) comments on this:

The Alexander of Plutarch’s Life is not simply the champion of Greek culture…the ideal philosopher-king, as he is in the speeches On the fortune or virtue of Alexander, nor is he a paradigm of the dangers of drink and despotism as he is in Curtius Rufus and in Stoic writers such as Seneca.

Plutarch had stated in De Alexandri Fortuna his argument that Alexander had achieved his unprecedented success not because of Fortune but despite it. That theme still exists to some extent in the Life of Alexander but it has become less overt; it becomes a subconscious assertion beneath the larger assessment of Alexander’s character. His biography is perhaps an antecedent to a modern scholar’s balanced assessment—his subject is neither wholly good nor wholly bad. Based on the specific arguments Plutarch advances, as well as his overall estimation of Alexander’s character, it is indeed likely that he meant his work, to some degree, to be a defense of his subject.

[1] Plut. Alex 1.1

[2] Duff (21) argues that “Plutarch’s words in the Alexander prologue, then, are tailored specifically to the Life which they introduce” but does not question their applicability to this particular Life.

[3] Barton 49.

[4] For instance, Alexander’s betrayal and subsequent slaughter of the Indian mercenaries in Plut. Alex 59.7.

[5] Hammond argues that both the terminology ‘Vulgate tradition’ and the underlying assumption of Cleitarchus as a common source are erroneous—but does not question that all three are more hostile than either Arrian or Plutarch.

[6] See Pearson’s discussion 212-213 in The Lost Histories of Alexander the Great.

[7] Justin Epitome 11.6.15.

[8] Ibid 11.10.14.

[9] Ibid 11.5.1-2.

[10] Ibid 11.11.6.

[11] Ibid 12.5.1.

[12] Ibid 12.6.3.

[13] Curtius Rufus 3.20

[14] Seneca De Beneficiis 7.2.5.

[15] Ibid 7.3.1.

[16] Lucan Bellum Civile 10.20-52.

[17] Livy Ab Urbe Condita 9.17-19.

[18] Though not all of the aforementioned for certain lived before him, each of them could and indeed seems most likely to have.

[19] A considered analysis of this is provided by Powell’s “The Sources of Plutarch’s Alexander.”

[20] Pearson 218.

[21] Pearson feels that role fell instead to Arrian, whose “work, whether earlier or later than Quintus Curtius, should probably be regarded as a protest against the popularity of Cleitarchus’ unsound history” (218).

[22] Plut. Alex 20.

[23] Plut. Alex 21.

[24] Plut. Alex. 23.

[25] Ibid 28

[26] Ibid 35.

[27] Ibid 39

[28] Ibid 41

[29] Ibid 71.

[30] For a more detailed discussion, see especially Hamilton’s “The Letters in Plutarch’s Alexander” and Samuel’s “Alexander’s ‘Royal Journals.’”

[31] Hamilton xl.

[32] Plut. Sol. 27.

[33] Plut. Alex. 19.

[34] Plut. Alex 48.

[35] Plut. Alex 55.

[36] Mossman 94 in Stadter Plutarch and the Historical Tradition.

[37] Hamilton lxv.

[38] Such as Powell’s assessment that “Plutarch’s Life of Alexander cannot have been used by Arrian…because a priori a historian of Alexander would not glean his material in scraps from brief and derivative works like the biographies of Plutarch” (Powell 231).

Picture: Olympias, Philip II. and Alexander

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Boi I adore you and your blog, you're always so accurate (ugh you really make justice to your memory). I feel the wild impulse of wanting to know everything about your life but i'm so afraid of stepping into false-history-shitties. Can I ask you what are your favourite false anecdotes ever made up on you?

Thank you, I certainly do justice to myself. I have learned that if no one is up to the job, you have to do it yourself. Perhaps I should have realized this before having Kallisthenes write my history… Ahem.

The dragging Batis behind my chariot at Gaza is funny:

For while Batis still breathed, thongs were passed round his ankles, he was bound to the king’s chariot, and the horses dragged him around the city, while the king boasted that in taking vengeance on an enemy he had imitated Achilles, from whom he derived his race. (Curtius 4.6.29-30 trans. Rolfe)

It’s even more extreme than Achilles, because Batis was #dragged when he was still alive! Thanks vulgate tradition, how’s that for over-dramatic? Well, if it actually happened, which it didn’t.

The Amazon Queen one is a good one. I wish that was true. Cough cough.

“Here the queen of the Amazons came to see Alexander […] And the story is told that many years afterwards Onesicritus was reading aloud to Lysimachus, who was now king, the fourth book of his history, in which was the tale of the Amazon, at which Lysimachus smiled gently and said: “And where was I at the time?” However, our belief or disbelief of this story will neither increase nor diminish our admiration for Alexander. (Plutarch 46.1-5 trans. Perrin, modified by myself)

On the other side of the coin, my vision about Homer appearing to me and telling me to found Alexandria in Egypt by Pharos is 110% true and I will not entertain any skepticism (see Plutarch 26.3-7 for details). And my dream about Herakles telling me to conquer Tyre is of course true as well (Plutarch 24.5). I would never lie about something like that.

Wanting to know everything about myself is a noble endeavor! If you want to read a good history of the glorious life of me, read Arrian. He has the best account, in my not humble at all opinion. Plutarch is also fun, but more sensationalist. And I applaud your use of “false-history-shitties;” I’m adding that to my modern vocabulary.

#asks#Alexander the Greatest#Homer#There's even an Odyssey quote in the Plutarch passage about the founding of Alexandria#you could almost say it's ....#epic

18 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey, i've seen you mentioning in your beginner guides that it's easier to focus on a single character, and i was wondering if you could help me out with some recs? i'm interested in Nimue (or Vivienne? the Lady of the Lake? I never know what to call her) and her relationships with Merlin and Arthur. classical works, essays, and retellings/contemporary books are all welcome, i'm not picky. of course, you're not obligated to answer this. thanks for reading and your amazing blog.

It was definitely easier for me, because my list of books was much less overwhelming and I could absorb general arthurian knowledge before divining into the other characters.

Of course! I usually don’t read essays, so I can’t help there (Also, I have to add that I usually don’t read Merlin specific books and many of those might have Nimue with a prominent role!), but this is what I know that revolves around the lady of the lake or where she has a prominent role. I used both Nimue and Lady of the Lake, and I tend to call and conflate with Nimue the character who becomes Merlin’s lover, and with lady of the lake the character who gives Arthur the sword:

Some (main) old texts where Nimue and the lady of the lake appears

Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur The Story of King Arthur and His Knights (Howard Pyles) The Vulgate and the Post Vulgate (but they are harder to find for cheap) Vita Merlini (Geoffrey of Monmouth) has a pseudo-lady of the lake character

(you can find the downloads of these texts in the list of everything here)

Books (lady of the lake or Nimue as protagonists) * = my favorites

The Book of Mordred (Velde)* (the story of Mordred told by three female characters’ POV, one of them is Nimue) Here Lies Arthur (Reeves)* (the lady of the lake is the main character) Avalon High (Meg Cabot)* (modern high school) Mrs. Pendragon + Mists of Manhattan (M. Lang) (a modern days story mostly focused on Guinevere but with Nimue too) Out of Avalon (Roberson) (This is a collection of short stories revolving around Avalon, so many of them are about Nimue or the lady of the lake) The Mists of Avalon (Marion Zimmer Bradley) (the whole book is focused on Avalon and has both a Nimue-like character and the lady of the lake) Cursed (Thomas Wheeler)

Books (lady of the lake or Nimue as secondary but well written characters) * = my favorites

Idylls of the Queen* (Phyllis Ann Karr) (kay and Mordred-focused, but Nimue appears and is a great character, also this is my favorite arthurian book) Queen of Camelot (McKenzie) (a Guinevere focused trilogy, with Nimue as a well characterized secondary character) Morgana* (Michel Rio) (in French/Spanish/Italian, Vivian is a secondary character and Morgana’s lover) Merlin Trilogy (James Mallory) (this is the novelization of Merlin 1998) Merlin Trilogy* (Mary Stewart) (Nimue appears as a secondary character and Merlin’s love) Believe (Victoria Alexander) (a trashy romance with Galahad, Nimue is a secondary character alongside Merlin) Warlord Chronicles* (Bernard Cornwell)

Play script or poetries

Mordred a Tragedy (the lady of the lake is one of Mordred’s allies) Idylls of the King (Tennyson)

Movies

Merlin 1993 (also known as October 32nd, this is about a modern days lady of the lake who finds her destiny) A Knight in Camelot 1998 (technically, the protagonist is hinted to be a Nimue-like character) Merlin and the War of Dragons (Nimue and Vivian both play a prominent role in this movie, and they are the best part of the movie) Merlin and the Sword (many characters in this movie! Among the stories, there is the story of Nimue and Merlin and their love)

Tv Shows

The Boy Merlin (the last episode has an interesting lady of the lake appearance) Merlin 1998 miniseries (Nimue is one of the main characters, and the lady of the lake also appears) Mists of Avalon miniseries (the lady of the lake is one of the main characters) Kaamelott (in various episode the lady of the lake appears as a secondary character) Camelot 2011 (VIvian appears in the show, but has not had any lady of the lake roles, sadly enough, and the show never had a second season) Cursed Netflix (the protagonist is the lady of the lake)

Musicals and opera

Isaac Albeniz’s Merlin opera Spamalot (but she is a bit different)

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

I see you talk a lot about historiography! What would you consider the most important development of Alexander’s historiography?

What the Hell is Historiography? (And why you should care)

This question and the next one in the queue are both going to be fun for me. 😊

First, some quick definitions for those who are new to me and/or new to reading history:

Historiography = “the history of the histories” (E.g., examination of the sources themselves rather than the subject of them…a topic that typically incites yawns among undergrads but really fires up the rest of us, ha.)

primary sources = the evidence itself—can be texts, art, records, or material evidence. For ancient history, this specifically means the evidence from the time being studied.

secondary sources = writings by historians using the primary evidence, whether meant for a “regular” audience (non-specialists) or academic discussions with citations, footnotes, and bibliography (sometimes referred to as “full scholarly apparatus”).

For ancient history, we also sometimes get a weird middle category…they’re not modern sources but also not from the time under discussion, might even be from centuries after the fact. Consider the medieval Byzantine “encyclopedia” called the Suda (sometimes Suidas), which contains information from now lost ancient sources, finalized c. 900s CE. To give a comparison, imagine some historian a thousand years from now studying Geoffry Chaucer from the 1300s, using an entry about him in some kid’s 1975 World Book Encyclopedia that contains information that had been lost by his day.

This middle category is especially important for Alexander, since even our primary sources all date hundreds of years after his death. Yes, those writers had access to contemporary accounts, but they didn’t just “cut-and-paste.” They editorialized and selected from an array of accounts. Worse, they rarely tell us who they used. FIVE surviving primary Alexander histories remain, but he’s mentioned in a wide (and I do mean wide) array of other surviving texts. Alas this represents maybe a quarter of what was actually written about him in antiquity.

OKAY, so …

The most important historiographic changes in Alexander studies!

I’m going to pick three, or really two-and-a-half, as the last is an extension of the second.

FIRST …decentering Arrian as the “good” source as opposed to the so-called “vulgate” of Diodoros-Curtius-Justin as “bad” sources.

Many earlier Alexander historians (with a few important exceptions [Fritz Schachermeyr]) considered Arrian to be trustworthy, Plutarch moderately trustworthy if short, and the rest varying degrees of junk. W. W. Tarn was especially guilty of this. The prevalence of his view over Schachermeyr’s more negative one owed to his popularity/ease of reading, and the fact he wrote on Alexander for volume 6 of the first edition (1927) of the Cambridge Ancient History, later republished in two volumes with additions (largely in vol. 2) in 1948 and 1956. Thus, and despite being a lawyer (barrister) not a professional historian, his view dominated Alexander studies in the first half of the 20th century (Burn, Rose, etc.)…and even after. Both Mary Renault and Robin Lane Fox (neither of whom were/are professional historians either), as well as N. G. L. Hammond (with qualifications), show Tarn’s more romantic impact well into the middle of the second half of the 20th century. But you could find it in high school and college textbooks into the 1980s.

The first really big shift (especially in English) came with a pair of articles in 1958 by Ernst Badian: “The Eunuch Bagoas,” Classical Quarterly 8, and “Alexander the Great and the Unity of Mankind,” Historia 7. Both demolished Tarn’s historiography. I’ve talked about especially the first before, but it really WAS that monumental, and ushered in a more source-critical approach to Alexander studies. This also happened to coincide with a shift to a more negative portrait of the conqueror in work from the aforementioned Schachermeyr (reissuing his earlier biography in 1973 as Alexander der Grosse: Das Problem seiner Persönlichtenkeit und seines Wirkens) to Peter Green’s original Alexander of Macedon from Praeger in 1970, reissued in 1991 from Univ. of California-Berkeley. J. R. Hamilton’s 1973 Alexander the Great wasn’t as hostile, but A. B. Bosworth’s 1988 Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great turned back towards a more negative, or at least ambivalent portrait, and his Alexander in the East: The Tragedy of Triumph (1996) was highly critical. I note the latter two, as Bosworth wrote the section on Alexander for the much-revised Cambridge Ancient History vol. 6, 1994, which really demonstrates how the narrative on Alexander had changed.

All this led to an unfortunate kick-back among Alexander fans who wanted their hero Alexander. They clung/still cling to Arrian (and Plutarch) as “good,” and the rest as varying degrees of bad. Some prefer Tarn’s view of the mighty conqueror/World unifier/Brotherhood-of-Mankind proponent, including that He Absolutely Could Not Have Been Queer. Conversely, others are all over the romance of him and Hephaistion, or Bagoas (often owing to Renault or Renault-via-Oliver Stone), but still like the squeaky-nice-chivalrous Alexander of Plutarch and Arrian.

They are very much still around. Quite a few of the former group freaked out over the recent Netflix thing, trotting out Plutarch (and Arrian) to Prove He Wasn’t Queer, and dismissing anything in, say, Curtius or Diodoros as “junk” history. But I also run into it on the other side, with those who get really caught up in all the romance and can’t stand the idea of a vicious Alexander.

It's not necessary to agree with Badian’s (or Green’s or Schachermeyr’s) highly negative Alexander to recognize the importance of looking at all the sources more carefully. Justin is unusually problematic, but each of the other four had a method, and a rationale. And weaknesses. Yes, even Arrian. Arrian clearly trusted Ptolemy to a degree Curtius didn’t. For both of them, it centered on the fact he was a king. I’m going to go with Curtius on this one, frankly.

Alexander is one of the most malleable famous figures in history. He’s portrayed more ways than you can shake a stick at—positive, negative, in-between—and used for political and moral messaging from even before his death in Babylon right up to modern Tik-Tok vids.

He might have been annoyed that Julius Caesar is better known than he is, in the West, but hands-down, he’s better known worldwide thanks to the Alexander Romance in its many permutations. And he, more than Caesar, gets replicated in other semi-mythical heroes. (Arthur, anybody?)

Alfred Heuss referred to him as a wineskin (or bottle)—schlauch, in German—into which subsequent generations poured their own ideas. (“Alexander der Große und die politische Ideologie des Altertums,” Antike und Abendland 4, 1954.) If that might be overstating it a bit, he’s not wrong.

Who Alexander was thus depends heavily on who was (and is) writing about him.

And that’s why nuanced historiography with regard to the Alexander sources is so important. It’s also why there will never be a pop presentation that doesn’t infuriate at least a portion of his fanbase. That fanbase can’t agree on who he was because the sources that tell them about him couldn’t agree either.

SECOND …scholarship has moved away from an attempt to find the “real” Alexander towards understanding the stories inside our surviving histories and their themes. A biography of Alexander is next to impossible (although it doesn’t stop most of us from trying, ha). It’s more like a “search” for Alexander, and any decent history of his career will begin with the sources. And their problems.

This also extends to events. I find myself falling in the middle between some of my colleagues who genuinely believe we can get back to “what happened,” and those who sorta throw up their hands and settle on “what story the sources are telling us, and why.” Classic Libra. 😉

As frustrating as it may sound, I’m afraid “it depends” is the order of the day, or of the instance, at least. Some things are easier to get back to than others, and we must be ready to acknowledge that even things reported in several sources may not have happened at all. Or at least, were quite radically different from how it was later reported. (Thinking of proskynesis here.) Sometimes our sources are simply irreconcilable…and we should let them be. (Thinking of the Battle of Granikos here.)

THIRD/SECOND-AND-A-HALF …a growing awareness of just how much Roman-era attitudes overlay and muddy our sources, even those writing in Greek. It would be SO nice to have just one Hellenistic-era history. I’d even take Kleitarchos! But I’d love Marsyas, or Ptolemy. Why? Both were Macedonians. Even our surviving philhellenic authors such as Plutarch impose Greek readings and morals on Macedonian society.

So, let’s add Roman views on top of Greek views on top of Macedonian realities in a period of extremely fast mutation (Philip and Alexander both). What a muddle! In fact, one of the real advantages of a source such as Curtius is that his sources seem to have known a thing or three about both Achaemenid Persia and also Macedonian custom. He sometimes says something like, “Macedonian custom was….” We don’t know if he’s right, but it’s not something we find much in other histories—even Arrian who used Ptolemy. (Curtius may also have used Ptolemy, btw.)

In any case, as a result of more care given to the themes of the historians, a growing sensitivity to Roman milieu for all of them has altered our perceptions of our sources.

These are, to me, the major and most significant shifts in Alexander historiography from the late 1800s to the early 2100s.

#asks#historiography#alexander the great#arrian#curtius#plutarch#diodorus#justin#w.w. tarn#fritz schachermeyr#a.b. bosworth#peter green#n.g.l. hammond#mary renault#robin lane fox#j.r. hamilton#ernst badian#classics#ancient history#ancient macedonia

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dankira and its Saints

When I heard of Dankira ended its service yesterday, I think it's about time for them to show their feast days in this latest installment to commemorate this occasion. So here it is.

[Merry Panic]

August 20 - Sora Asahi

St. Bernard of Clairvaux: 12th century French abbot and confessor, and a major leader in the revitalization of Benedictine monasticism through the nascent Order of Cistercians. There he preached an immediate faith, in which the intercessor was the Virgin Mary. In 1139, Bernard assisted at the Second Council of the Lateran. He subsequently denounced the teachings of Peter Abelard to the pope, who called a council at Sens in 1141 to settle the matter. Bernard was the first Cistercian placed on the calendar of saints, and was canonized by Pope Alexander III in 1174, and Pope Pius VIII bestowed Bernard the title of Doctor of the Church. His major shrine can be found in Troyes Cathedral.

March 20 - Mahiru Hinata

St. John Nepomucene (John of Nepomuk): 14th century priest and martyr who was drowned in the Vltava river at the behest of Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia (Czech Republic). Later accounts state that he was the confessor of the queen of Bohemia and refused to divulge the secrets of the confessional. On the basis of this account, John of Nepomuk is considered the first martyr of the Seal of the Confessional, a patron against defamation and, because of the manner of his death, a protector from floods and drowning. He is the patron saint of the Spanish Naval Infantry.

November 24 - Reiji Yano

The Vietnamese Martyrs: The Vatican estimates the number of Vietnamese martyrs at between 130,000 and 300,000. Pope St. John Paul II decided to canonize those whose names are known and unknown, giving them a single feast day. One of the most prominent person of the group is Andrew Dũng-Lạc, who was born to a peasant family and is ordained a priest in 1823. Many years later in 1998, he and the rest of the martyrs were canonized by Pope St. John Paul II. Among the number of the martyrs, there were 97 Vietnamese, 11 Dominican missionaries from Spain, and 10 French belonged to the Paris Foreign Mission Society; 59 were lay people and the rest of them are religious and or members of the clergy.

[Étoile]

February 17 - Akira Shido

Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order: The seven holy founders consisted of Alexis Falconieri, Amadeus of the Amidei, Hugh dei Lippi Uggucioni, Benedetto dell' Antella, Gherardino di Sostegno, Buonfiglio dei Monaldi and Giovanni di Buonagiunta. On January 1888, Pope Leo XIII canonized all seven of them, and their feast was inserted in the General Roman Calendar for celebration on 11 February, the anniversary of the granting of canonical approval to the order in 1304. In the 1969 revision of the calendar, 17 February, the date of death of Alexis Falconieri was judged to be more appropriate.

December 11 - Noel Gekkoin

Pope St. Damasus I: 37th bishop of Rome who reigned for 18 years. He presided over the Council of Rome of 382 that determined the canon or official list of sacred scripture, and spoke out against major heresies in the church (including Apollinarianism and Macedonianism) and encouraged production of the Vulgate Bible with his support for Jerome. He helped reconcile the relations between the Church of Rome and the Church of Antioch, and encouraged the veneration of martyrs.

June 27 - Kei Kagemiya

Our Lady of Perpetual Help (Our Lady of Perpetual Succour): A Marian title represented in a celebrated 15th-century Byzantine icon also associated with the same Marian apparition. The icon is originated from the Keras Kardiotissas Monastery and has been in Rome since 1499, and today, it is permanently enshrined in the Church of Saint Alphonsus, where the official Novena to Our Mother of Perpetual Help text is prayed weekly. In 1867, Pope Pius IX granted the image its Canonical Coronation along with its present title. The Redemptorist Congregation of priests and brothers are the only religious order currently entrusted by the Holy See to protect and propagate a Marian religious work of art. Due to promotion by the Redemptorist Priests since 1865, the image has become very popular among Roman Catholics, and modern reproductions are oftentimes displayed in residential homes, commercial establishments, and public transportation.

[Theater Bell]

May 12 - Seito Tsubaki

Bl. Imelda Lambertini: Italian laywoman, virgin and mystic. Her parents were devout Catholics and were known for their charity and generosity to the underprivileged of Bologna. On her fifth birthday, she requested to receive Holy Eucharist; however the custom at the time was that children did not receive their First Holy Communion until it reached the age of fourteen. On the day of the vigil of the Ascension, she knelt in prayer and the 'Light of the Host' was reportedly witnessed above her head by the Sacristan, who then fetched the priest so he could see. After seeing this miracle, the priest felt compelled to admit her to receiving the Eucharist. Immediately after receiving it, Lambertini went back to her seat, and decided to stay after mass and pray. Later when a nun came to get Lambertini for supper, she found Lambertini still kneeling with a smile on her face. The nun called her name, but she did not stir, so she lightly tapped Imelda on the shoulder, at which Imelda collapsed to the floor dead. Beatified by Pope Leo XII in 1826, she is the patroness of First Communicants.

July 20 - Soma Yagami

St. Apollinaris of Ravenna: 1st century Syrian bishop and martyr, whom the Roman Martyrology describes as 'a bishop who, according to tradition, while spreading among the nations the unsearchable riches of Christ, led his flock as a good shepherd and honored the Church of Classis near Ravenna by a glorious martyrdom.' A noted miracle worker, Apollinaris is considered especially effective against gout, venereal disease and epilepsy. His relics are at the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo and the 6th century Benedictine Basilica of Sant'Apollinare in Classe, both in Ravenna and in Saint Lambert's church in Düsseldorf, Germany.

November 11 - Nozomu Miki

St. Martin of Tours: Confessor and the third bishop of Tours. One of the most familiar and recognizable Christian saints in Western tradition. Martin converted to Christianity at a young age and served in the Roman cavalry in Gaul, but left military service at some point prior to 361, when he became a disciple of Hilary of Poitiers, establishing the monastery at Ligugé. He is best known for the account of his using his military sword to cut his cloak in two, to give half to a beggar clad only in rags in the depth of winter. His shrine in Tours became a famous stopping-point for pilgrims on the road to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. He is the patron of beggars, wool-weavers and tailors, as well as the patron of the United States Army Quartermaster Corps even though he detested violence.

[Sanzensekai]

September 18 - Yukari Wakakusa

St. Joseph of Cupertino: Italian friar from the Conventual Franciscans, a branch of the Franciscan order. He was said to have been remarkably unclever, but prone to miraculous levitation and intense ecstatic visions that left him gaping. Canonized as saint by Pope Clement XIII in 1767, he is the patron of mental handicaps, examinations, aviation and astronauts.

June 13 - Mitsukuni Minamoto

St. Anthony of Padua: Franciscan Portuguese friar and priest who is noted by his contemporaries for his powerful preaching, expert knowledge of scripture, and undying love and devotion to the poor and the sick, he was one of the most quickly canonized saints in church history. Although he is known as the patron of lost items, his major shrine can be found in Padua, Italy. In January 1946, he is proclaimed a Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius XII, and is given the title of Doctor Evangelicus (Evangelical Doctor).

April 28 - Oboro Kiriyama

St. Louis-Marie Grignion de Montfort (Louis de Monfort): French priest and confessor, who was known in his time as a preacher and was made a missionary apostolic by Pope Clement XI. As well as preaching, he found time to write a number of books which went on to become classic Catholic titles and influenced several popes, and he is known for his particular devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary and the practice of praying the Rosary. He is considered as one of the early writers in the field of Mariology. His most notable works regarding Marian devotions are contained in Secret of the Rosary and True Devotion to Mary. Monfort is canonized as a saint two years after World War II under the pontificate of Pope Pius XII.

[TOXIC]

October 9 - Ageha Kurenai

St. Louis Bertrand: Spanish Dominican friar, confessor, missionary, and religious brother who is known as the 'Apostle of South America.' After his ordination by St. Thomas of Villanova, he went to South America for his missionary work. According to legend, a deadly draught was administered to him by one of the native priests. Through Divine interposition, the poison failed to accomplish its purpose. There is a town festival, called La Tomatina in Buñol, Valencia, in his honor along with Mare de Déu dels Desemparats.

April 12 - Shiki Janome

Pope St. Julius I: 35th successor of St. Peter who reigned for 15 years and is credited with splitting the birth of Christ into two distinct celebrations (Epiphany and the Nativity) as well as asserting the authority of the pope over the Arian Eastern bishops. After his death in 352 AD, he is succeeded by Pope Liberius.

January 12 - Tsukumo Busujima

St. Marguerite Bourgeoys: French nun who is known as the founder of the Congregation of Notre Dame of Montreal in the colony of New France, now part of the province of Québec in Canada. She is also significant for developing one of the first uncloistered religious communities in the Catholic Church. She was canonized in 1982 and declared a saint by the Catholic Church, the first female saint of Canada.

[Black Meteor Camp (B.M.C.)]

January 31 - Atago Rentaro

St. John Bosco: Italian priest, educator, confessor and writer who is popularly known as 'Don Bosco' as well as the 'Father and Teacher of Youth'. While working in Turin, where the population suffered many of the ill-effects of industrialization and urbanization, he dedicated his life to the betterment and education of street children, juvenile delinquents, and other disadvantaged youth. He developed teaching methods based on love rather than punishment, a method that became known as the Salesian Preventive System. John was an ardent devotee of Mary, mother of Jesus, under the title Mary Help of Christians. He later dedicated his works to De Sales when he founded the Salesians of Don Bosco, based in Turin. He also founded the Institute of the Daughters of Mary Help of Christians, a religious congregation of nuns dedicated to the care and education of poor girls together with Maria Domenica Mazzarello, and he taught Dominic Savio, of whom he wrote a biography that helped the young boy be canonized.

September 6 - Habashiri Ginko

Zechariah the Prophet: He was a person that can be found in the Hebrew Bible and traditionally considered the author of the Book of Zechariah, the 11th of the Twelve Minor Prophets. He was a prophet of the Kingdom of Judah, and, like the prophet Ezekiel, was of priestly extraction. The Roman Catholic Church honors him with a feast day assigned to this date.

August 4 - Tsubaki Kento

St. John Vianney: French priest and confessor who is known as the patron saint of parish priests. He is often referred to as the 'Curé d'Ars', internationally known for his priestly and pastoral work in his parish in Ars, France, because of the radical spiritual transformation of the community and its surroundings. Catholics attribute this to his saintly life, mortification, persevering ministry in the sacrament of confession, and ardent devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary. His major shrine can be found in Ars-sur-Formans.

#random stuff#catholic#catholic saints#dankira#dankira!!! boys be dancing!#sora asahi#mahiru hinata#reiji yano#akira shido#noel gekkoin#kei kagemiya#seito tsubaki#soma yagami#nozomu miki#yukari wakakusa#mitsukuni minamoto#oboro kiriyama#ageha kurenai#shiki janome#tsukumo busujima#atago rentaro#habashiri ginko#tsubaki kento

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

While it is true that the revival of learning and letters in the fifteenth century greatly enriched the English language, it drove out thousands of very fine English words. Previous to that time, it had sometimes been necessary to use a double word to give the necessary meaning in the Scriptures. Thus, in the Anglo-Saxon Gospels of about the time of King Alfred, about a thousand years ago, the following expressions are met with: leorning-cnicht (learning-knight) for disciple (a Latin word); hundredes ealdor-man (alderman of a hundred) for centurion (also a Latin word); bocere (book-wer, bookman) for scribe (another Latin word); big-spel (near-story, example, like German Bei-spiel) for the Greek parable.

Eternal is one of the many hundreds of words which gained entrance into English during the Renaissance. Previous to that time, it was completely unknown. No such word appears in any old English scriptures. Instead of it, there is found a simple little word with the meaning of eonian, or something like that, spelt ece, of which more will be said later. In fact, it may be laid down as a rule that no language had, for some time after the first century A.D., any term to denote eternity.

Some of the following facts may at first sight seem somewhat startling, yet that is because they are not widely known. Had the old English Bibles been translated direct out of the Greek, instead of from the Latin Vulgate Version of Jerome (380 A.D.), it is very probable that the word eternal would never have been found in our modern Bibles and theological terminology at all.

But for the Norman Conquest of England in 1066 A.D., which brought many French words into the English language (and French is largely decayed and corrupt Latin), and drove out many native English words, we should most probably now be using not eternal, but ece, the old equivalent of eonian. On the other hand, had the sack of Constantinople by hordes of Turks from Asia taken place prior to the Norman Conquest, instead of in 1453, the likelihood is that we should have had the Greek term eonian incorporated into English, instead of the Latin eternal.

The capture of Constantinople by the Turks was of enormous importance to Europe. It was then the great center of learning, especially Greek learning. When it was sacked, hosts of learned doctors were scattered abroad all over Europe, carrying with them the knowledge of the Greek tongue and the treasures of Greek literature. It is hard to believe that for over a thousand years, up till the year 1453, Greek was almost unknown or forgotten in most of Europe. Even in Italy, which formerly had been dominated by Greek, it became almost unknown. Very few quotations from Greek poets are to be found in Italian writers from the sixth to the fourteenth centuries.

No Greek was taught publicly in England until about 1484, when it began to be taught at Oxford University. Erasmus, the great Dutch scholar, learnt Greek at Oxford and subsequently was Professor of Greek at Cambridge from 1509 till 1514, during which time Tyndale studied there. Erasmus issued his first Greek New Testament in 1516. This was the first Greek New Testament printed for sale. The first Greek grammar for well over a thousand years was published at Milan in 1476, and the first lexicon four years later. As an English scholar expressed it, "Greece had arisen from the grave with the New Testament in her hand."

-- Alexander Thomson, Whence Eternity? How Eternity Slipped In

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Orkney in my Arthuriana

So here is how I am thinking of the Orkney situation in my Arthuriana.

Traditionally Lot is King of Orkney. And Lothian. And Norway. In the earliest texts, Geoffey, Wace, Layamon, he is King of Lothian and inherits Norway from his uncle Sichelm. The King of the Orkneys is a fellow named Gunfasius.

Yet I think beginning in Boron Lot becomes King of Orkney. Gunfasius thus disappears from following Arthuriana. In Vulgate Lot rules Orkney (quite amusingly it is referred to as a city, I kind of doubt the French authors knew much of British geography).

So I was thinking of a meta-version of this in my version of events.

In Geoffrey there are three brothers who rule Albany between them, Auguselus, King of Albany, Urien, of Moray, and Lot, the ‘Duke’ of Lothian. Auguselus fades out of Arthuriana a bit, in some versions getting conflated with Anguish of Ireland possibly. Urien and Lot are no longer brothers. Urien is King of Gorre, or former ruler of Gorre before passing it to his nephew Bagdemagus. Following Arthuriana is complicated.

And the historical figures they were based on were not brothers, Geoffrey just made them so, sucking in history and mingling it into Arthuriana, as we all do.

Anyway, Urien was a historical figure, the King of Rheged, son of Cynfarch Oer. So what I am thinking is Cynfarch was a very ambitious man, interested in expanding his dominions and becoming the main power in Albany.

Due to a disputed succession in Orkney (think like after Alexander III of Scotland’s death) Cynfarch tries to seize power there, against a kinsman. To help his bid for power he marries a Norwegian Princess, but it is agreed a son from this union must be given Orkney. Which happens. (I go with Lot being half-brother as some accounts say the King of Norway had no other heirs save Lot, possibly to make Arthur look more legitimate in helping his brother-in-law. Well, uncle by marriage as in some accounts the Anna Lot is married to is Uther’s rather then Arthur’s sister. Anyway this would be odd with Lot having brothers so I imagine they are half-brothers.)

Auguselus, due to his father’s planning, is able to establish himself as King of Albany. As he may have been based on a ruler of Argyll I imagine his power base is there (mayhaps he married a Dál Riata Princess. His mother could be from the ruling House of Argyll.).

As for Urien his father is able to get him Gorre, having his daughter marry Tadus, from one of the most powerful Houses in Gorre for alliance. After Urien resigns the Kingdom he grants the eldest son of that union, Bagdemagus, rule of Gorre. He then heads North and is granted Rheged and Moray by his elder brother Auguselus.

But what of Orkney?

Lot has also been given Lothian by his father. (In Tysilio he has Lindsey but meh. And in Boece he’s the King of the Picts.) However there are some who think his family are not the rightful holders of authority in Orkney.

Enter Gunfasius. He believes his claim is better. Think of him like... the Florents to the Tyrells in ASOIAF. He is one of the most powerful Lords in Orkney. While he does not openly fight Lot, he remains as a potential threat. Lot cannot just eliminate him because that would make him look bad and likely trigger a rebellion from local nobles. Lot already has problems trying to hold onto another Kingdom.

In Malory two Knights are mentioned, “Then came therein two brethren, cousins unto Sir Gawaine, the one hight Sir Edward, that other hight Sir Sadok, the which were two good knights; and they asked of King Arthur that they might have the first jousts, for they were of Orkney. I am pleased, said King Arthur. Then Sir Edward encountered with the King of Scots, in whose party was Sir Tristram and Sir Palomides; and Sir Edward smote the King of Scots quite from his horse”.

I imagine these are Gunfasius’ sons. They were formerly kept as h̶o̶s̶t̶a̶g̶e̶s̶ squires by Lot. After he was beaten Arthur decided to take them as h̶o̶s̶t̶a̶g̶e̶s̶ squires to his court.

And the little detail Edward smote the King of Scots? Might be Auguselus, a little dig from his family at Lot’s family. Though I imagine the term Scots will be a bit more loaded. The people of Dál Riata are Scots, being descended from settlers from Scotia, now called Ireland, a son of an Irish King, Fergus, was the first King of Scotland.

Mostly the land is referred to as Albany, but the Scots are one of the mightiest forces there, under Goranus for much of Arthur’s reign. Then there’s Eugenius... but that’s another story.

As for the tensions between Gunfasius and Lot Arthur sees how to solve it. Gunfasius is more of a pragmatist. Like his father Lot likes prestige and grandeur. Just like Auguselus has the title King of Albany but in reality can’t really hold power over all of it. So he suggests while Lot is away Gunfasius be Steward of Orkney. Which is agreed to. As for Morgause she is asked to act in a Regent’s role in Lothian. She might bear Mordred on Orkney but she does more of her abuse in Lothian. (I imagine at times her family is more frightened of her then Gunfasius because abusive relatives are the worst. And she frightens Gunfasius and the people of Orkney more then any of her family.)

There could be some humour in pointing out Lothian is more populated and nicer then Orkney so why does Lot put all this effort into holding onto it? But nobles like titles. Dinaden might make a jibe about it as he seems the sort who would.

Also Lot’s uncle dies and he and Arthur fight to get some Norwegian lands from Riculf, who takes the Kingship. But a younger son of Aschil, King of Denmark, takes some Norwegian lands. This is due to Odbrict, King of Norway, suddenly turning up in end of Arthur section of Geoffrey. Also it’s a ref to Haakon VII of Norway, second son of heir to Danish throne, who was chosen as new King of Norway when his great-uncle Oscar II of Sweden renounced the throne of Norway in 1905.

Gunfasius continues to scheme. He has one of the best knowledges of lineages in all Britain... naturally due to his claim to Orkney meaning you have to go back some generations. He and Eugenius at times may plot together, Eugenius agreeing when he becomes King he would ‘recognise’ Gunfasius if they ever made a bid for the throne.

Gawain, being a friendly sort, gets on well with his distant cousins. They don’t have to feud because their fathers do.

However, for some reason, Edward predeceases his father, leaving a son, also called Gunfasius. Sadok joins Lancelot and the last reference to him in Malory says that when Lancelot is giving out lands to his followers “Sir Sadok he gave the Earldom of Surlat” (which seems to be a south-west commune Sarlat-la-Canéda).

Lot’s line, due to the fighting, are much diminished. He has a grandson still living... in Constantinople, so Cligès won’t be contesting Orkney.

Sadok gets the Earldom and considers contesting his nephew Gunfasius the Younger for Gunfasius the Elder’s lands. But he decides not to risk an Earldom in nicer lands anyway for Kingship of Orkney. He also sees the consequences of family splits.

So Gunfasius becomes King of Orkney. As a result of confused identification later accounts act as if Gunfasius was King of Orkney for more of Arthur’s reign.

And that is the Orkney situation!

If you got through you will realise Arthuriana is very complicated and alters round. And don’t try to think too hard about this and history. I gave up long ago.

@blackcur-rants @cukibola @epic-summaries

#arthuriana#my arthuriana#gunfasius#king lot#how many lands do gawains family have#eugenius iii#king arthur#orkney clan#auguselus#urien#arthuriana is complicated#matter of britain

20 notes

·

View notes