#Andean textiles

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

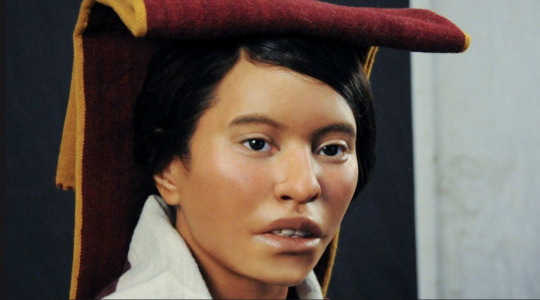

So apparently Swedish and Polish facial reconstructionists decided to try to recreate the famous Incan "Ice Maiden" mummy dubbed "Juanita".

Truthfully, I feel like these European reconstructionists ( do not know how to re-create Andean facial features and the results ended up... terribly uncanny. So down below, with the use of photoshop, I edited the bust with more Andean Indigenous Peruvian facial features to honor the "Ice Maiden".

My version:

I made her brows straighter and longer, got rid of the cleft chin, gave her a down-turned mouth, broader lips (not small), I made her lips a little larger too and I made her nose longer/bigger and wider around the nasal Ala. I also broadened her nostrils a tad

and I made her under-eyes more puffy

I widened her bone structure

I emphasized her sideburns

My version (on top):

original (white euros created) below:

I hope that in the future, more Andean/Indigenous Peruvian facial reconstructionists have opportunities to work on revealing the faces of their kin and ancestors. We needed more andean people involved in her reconstruction.

Let me know what you think of my edits down below too!

I hope you enjoy them!

the original article can be read here:

#I took the artistic liberty to remove her cleft chin all together because i never see andeans like myself with clefts#i love a more down turned lip/mouth shape#archaeology#indigenous peruvians#native peruvian#inca#inca girl#ice maiden#facial reconstruction#my photoshops#andean history#andean pride#native south american#mujer andina#ndn tumblr#andean culture#andean textiles#andean indigenous#indigenous women#andina#andean#bipoc#indigena#pre columbian#andes#warmi#we need more ndns in science

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

#TextileTuesday:

“Border fragment of wool with a continuous band of #hummingbirds and fringelike appendages representing beans. Early Nasca [Nazca, Peru, c.1-450 CE]. Pollination of bean plants by birds may be suggested here. Border was formed using a needle-knit stemstitch.”

On display at American Museum of Natural History [41.2/6321]

#animals in art#birds in art#bird#birds#museum visit#AMNH#hummingbird#hummingbirds#Peruvian art#Andean art#Nazca art#Textile Tuesday#textile#wool#ancient art#pollination#Indigenous art#ethnobotany#erhnozoology#ethnobiology#TEK#traditional ecological knowledge#South American art

6K notes

·

View notes

Photo

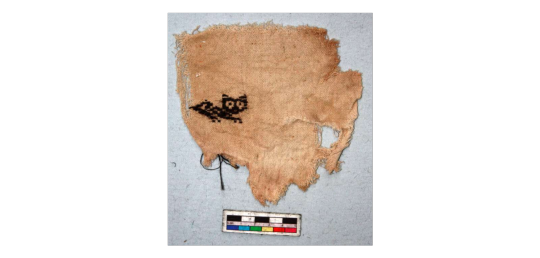

ohhhh noooo it has the saddest eyes

textile

Cultures/periods: Chimu (?) Chancay (?)

Production date: 900-1430

Made in: Peru

Provenience unknown, possibly looted

Textile fragment; cotton plain weave ground with paired warps; camelid supplementary weft patterning; feline figure; cream and black.

British Museum

#precolumbian#Precolumbian art#andean#Andean textiles#textile art#chancay#chimu#Peru#peruvian art#Peruvian textiles

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

500-year-old Snake Figure from Peru (Incan Empire), c. 1450-1532 CE: this fiber craft snake was made from cotton and camelid hair, and it has a total length of 86.4cm (about 34in)

This piece was crafted by shaping a cotton core into the basic form of a snake and then wrapping it in structural cords. Colorful threads were then used to create the surface pattern, producing a zig-zag design that covers most of the snake's body. Some of its facial features were also decorated with embroidery.

A double-braided rope is attached to the distal end of the snake's body, near the tip of its tail, and another rope is attached along the ventral side, where it forms a small loop just behind the snake's lower jaw. Similar features have been found in other serpentine figures from the same region/time period, suggesting that these objects may have been designed for a common purpose.

Very little is known about the original function and significance of these artifacts; they may have been created as decorative elements, costume elements, ceremonial props, toys, gifts, grave goods, or simply as pieces of artwork.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art argues that this figure might have been used as a prop during a particular Andean tradition:

In a ritual combat known as ayllar, snakes made of wool were used as projectiles. This effigy snake may have been worn around the neck—a powerful personal adornment of the paramount Inca and his allies—until it was needed as a weapon. The wearer would then grab the cord, swing the snake, and hurl it in the direction of the opponent. The heavy head would propel the figure forward. The simultaneous release of many would produce a scenario of “flying snakes” thrown at enemies.

The same custom is described in an account from a Spanish chronicler named Cristóbal de Albornoz, who referred to the tradition as "the game of the ayllus and the Amaru" ("El juego de los ayllus y el Amaru").

The image below depicts a very similar artifact from the same region/time period.

Why Indigenous Artifacts Should be Returned to Indigenous Communities.

Sources & More Info:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Snake Ornament

Serpent Symbology: Representations of Snakes in Art

Journal de la Société des Américanistes: El Juego de los ayllus y el Amaru

Yale University Art Gallery: Votive Fiber Sculpture of an Anaconda

#artifacts#archaeology#inca#peru#anthropology#fiber crafts#americas#pre-columbian#andes#south america#art#snake#effigy#textiles#textile art#embroidery#history#stem stitch#serpent#amaru#mythology#andean lore#fiber art#incan empire#indigenous art#repatriation#middle ages#flying snakes tho

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

JOEL G IS FROM PERU THAT MAKES SO MUCH SENSE while theres cultural reffrences from all over in ENA theres a bunch of peru specific things i recognized like the masks and outfit the merchant wears (guy who sells Turron) and the as well as many andean textile patterns and designs across the series and game. its so cool i love when regional culture influnces media like that

279 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The relationship of textiles to writing is especially significant, not only for the cuneiform-like qualities of many patterns (preserved in a Hungarian term irásos, meaning 'written'), but also for the parallels between ink on papyrus and pigment on bark cloth. There is, in fact, little difference between the two. Such connections are implied in many textile terms. For example, the Indian full-colour painted and printed 'kalamkari' are so named from the Persian for pen, kalam; the wax for Indonesian batiks is delivered by a copper-bowled tulis, also meaning pen. The European term for hand-colouring of details on cloth is 'pencilling'. The Islamic term tiraz, originally denoting embroideries, came to encompass all textiles within this culture that carried inscriptions. And the patterns woven into the silks of Madagascar are acknowledged as a language: the Malagasy vocabulary for writing and preparing the loom are synonymous, while the finest stripes are zanatsoratra, literally children of the writing, or vowels. The study of textiles is, in fact, a branch of palaeography, in which deciphering and dating reveals the stories encapsulated in cloth 'handwriting'.

With or without inscriptions, textiles convey all kinds of 'texts': allegiances are expressed, promises are made (as in today's bank notes, whose value is purely conceptual), memories are preserved, new ideas are proposed. Records were kept in quipu (khipu) a method of knotting string used by the Incas and other ancient Andean cultures to keep accounts and communicate information, the oldest of which is some 4,600 years old. Many anthropological and ethnographical studies of textiles aim at teaching us how to read these cloth languages anew. The 'plot' is provided by the socially meaningful elements; the 'syntax' is the construction, often only revealed by the application of archaeological and conservation analyses. Equally, the most creative textiles of today exploit a vocabulary of fibres, dyes and techniques. Textiles can be prose or poetry, instructive or the most demanding of texts. The ways in which they are used - and reused - add more layers of meaning, all significant indicators of sensitivities that can be traced back to the Stone Age."

— Mary Schoeser, World Textiles

525 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Many of the paracas textiles depict flying people with elongated heads holding magic related utensils.

Pre Inca Textile (Paracas - Peru)

#solar#mysterious#flying#god#energy#atlantis#paracas#ancient#knowledge#andean#textile#archaeology#peru#light#orion#pyramid#secret#serpent#awareness#rainbow#Archeology#esoteric#occult#magic#levitation#aliens and ufos#golden age#ancient gods

515 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word List: Fashion History

to try to include in your poem/story (pt. 3/3)

Pelete Bite - a fabric created by the Kalabari Ijo peoples of the Niger Delta region by cutting threads out of imported cloth to create motifs

Pelisse - a woman’s long coat with long sleeves and a front opening, used throughout the 19th century; can also refer to men’s military jackets and women’s sleeved mantles

Peplos - a draped, outer garment made of a single piece of cloth that was worn by women in ancient Greece; loose-fitting and held up with pins at the shoulder, its top edge was folded over to create a flap and it was often worn belted

Pillow/Bobbin Lace - textile lace made by braiding and twisting thread on a pillow

Pinafore - a decorative, apron-like garment pinned to the front of dresses for both function and style

Poke Bonnet - a nineteenth-century women’s hat that featured a large brim which extended beyond the wearer’s face

Polonaise - a style of dress popular in the 1770s-80s, with a bodice cut all in one and often with the skirts looped up; it also came back into fashion during the 1870s

Pomander - a small metal ball filled with perfumed items worn in the 16th & 17th centuries to create a pleasant aroma

Poulaine - a shoe or boot with an extremely elongated, pointed toe, worn in the 14th and 15th centuries

Raffia Cloth - a type of textile woven from palm leaves and used for garments, bags and mats

Rebato - a large standing lace collar supported by wire, worn by both men and women in the late 16th and early 17th century

Robe à L’anglaise - the 18th-century robe à l’anglaise consisted of a fitted bodice cut in one piece with an overskirt that was often parted in front to reveal the petticoat

Robe à la Française - an elite 18th-century gown consisting of a decorative stomacher, petticoat, and two wide box pleats falling from shoulders to the floor

Robe en Chemise - a dress fashionable in the 1780s, constructed out of muslin with a straight cut gathered with a sash or drawstring

Robe Volante - a dress originating in 18th-century France which was pleated at the shoulder and hung loose down, worn over hoops

Roses / Rosettes - a decorative rose element usually found on shoes in the 17th century as fashion statement

Ruff - decorative removable pleated collar popular during the mid to late 16th and 17th century

Schenti - an ancient Egyptian wrap skirt worn by men

Shirtwaist - also known as waist; a woman’s blouse that resembles a man’s shirt

Skeleton Suit - late 18th & early 19th-century play wear for boys that consists of two pieces–a fitted jacket and trousers–that button together

Slashing - a decorative technique of cutting slits in the outer layer of a garment or accessory in order to expose the fabric underneath

Spanish Cape - an outer wrap often cut in a three-quarter circle originating from Spain

Spanish Farthingale - a skirt made with a series of hoops that widened toward the feet to create a triangular or conical silhouette, created in the late 15th century

Spencer Jacket - a short waist- or bust-length jacket worn in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

Stomacher - a decorated triangular-shaped panel that fills in the front opening of a women’s gown or bodice during the late 15th century to the late 18th century

Tablion - a rectangular panel, often ornamented with embroidery or jewels, attached to the front of a cloak; worn as a sign of status by Byzantine emperors and other important officials

Toga - the large draped garment of white, undyed cloth worn by Roman men as a sign of citizenship

Toga Picta - a type of toga worn by an elite few in Ancient Rome and the Byzantine Empire that was richly embroidered, patterned and dyed solid purple

Tricorne Hat - a 3-cornered hat with a standing brim, which was popular in 18th century

Tupu - a long pin used to secure a garment worn across the shoulders. It was typically worn by Andean women in South America

Vest/Waistcoat - a close-fitting inner garment, usually worn between jacket and shirt

Wampum - are shell beads strung together by American Indians to create images and patterns on accessories such as headbands and belts that can also be used as currency for trading

Wellington Boot - a popular and practical knee- or calf-length boot worn in the 19th century

If any of these words make their way into your next poem/story, please tag me, or leave a link in the replies. I would love to read them!

More: Fashion History ⚜ Word Lists

#word list#fashion history#writeblr#dark academia#terminology#spilled ink#writing prompt#writers on tumblr#poets on tumblr#poetry#literature#light academia#fashion#lit#studyblr#langblr#words#linguistics#history#culture#creative writing#worldbuilding#writing reference#writing resources

145 notes

·

View notes

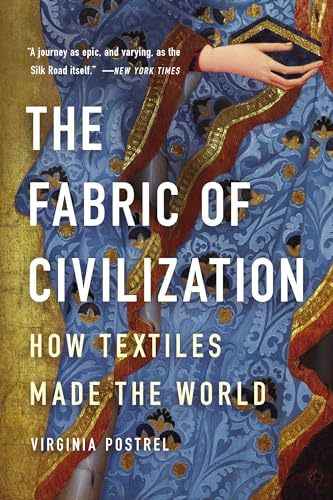

Photo

The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World

In "The Fabric of Civilization," Virginia Postrel explores how the history of textiles is akin to the story of civilization as we know it. As evidenced throughout her book, Postrel treats each chapter as a standalone story of its production and journey, all the while masterfully weaving it together to show the story of human ingenuity. While academic in nature due to its incredibly well-researched methodology, the general reader will enjoy the book's unique style and approach to world history.

In The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the World, Virginia Postrel expertly demonstrates how the history of textiles is the story of human progress. Although textiles have shaped society in many ways, their central role in the development of technology and impact on socio-economics have been exceedingly overlooked. Attempting to remedy this issue, Postrel organizes her book into two distinct sections: one focusing on the different stages of textile production (fiber, thread, cloth, and dye) and the other on the consumers, traders, and future innovators of said textiles. To strengthen her argument, Postrel pulls from different primary sources across many regions and cultures, such as the works of people like entomologist Agostino Bassi and the accounts of disgruntled Assyrian merchants. However, Postrel goes beyond relying solely on books and peer-reviewed articles; she personally interviewed textile historians, scientists, businesspeople, and artisans who offered their own insight regarding the importance of textiles in the world. To help the reader envision the intricacies of textile manufacturing, the book is riddled with images that range from ancient spindle whorls and Andean textile patterns to nineteenth-century pamphlets raging over improved cotton seeds. It is quite a laborious task to explain the history of textiles, but Postrel’s way of organizing her chapters and style of writing does an excellent job of conveying her argument.

In Chapter One, Postrel illustrates the many uses of fibers and how their multipurpose functionality served its role in world economies. From the domestication of cotton in the Americas to sericulture in ancient China, such fibers left an indelible mark on trade and technology. Chapter Two looks at the use of thread's connection with social and gender roles as Postrel argues that dismissing fabric as feminine domesticity ignores its integral role in the social innovations that products like clothing and sails provided. Chapter Three connects mathematics with weaving through handwoven textiles by Andean artisans and in the notations written down in Marx Ziegler’s manual, The Weaver’s Art and Tie-Up Book (1677). Chapter Four explains how dyes not only contributed to the distinction between social classes, such as the use of Tyrian purple by Roman emperors but also the ingenuity of humans to ascribe meaning and beauty to a variety of colors. Furthermore, the increasing and competitive trading of dyes in the 16th and 17th centuries would eventually contribute to the discovery of synthetic dyes.

Textile traders and consumers also helped to foster cultural exchanges. Postrel then highlights how traders often also served as innovators. The implementation of the Fibonacci sequence in European trading not only helped traders with bookkeeping but also gave a new perspective to the practicality of learning math by helping traders understand profits and calculate prices. Readers explore in Chapter Six how the Mongol Empire expanded across many different lands for their desire for valuable woven textiles. Under the Pax Mongolica, the textile trade flourished as the Mongols protected the Silk Road, resulting in cross-cultural and technological exchange between Europe and Asia. Lastly, in Chapter Seven, Postrel introduces synthetic polymers like nylon and polyester, where the efforts made by scientists like Wallace Carothers, Rex Whinfield, and James Dickson have revolutionized the use of textiles. Companies like Under Armour use polyester to create water-repellent clothing. Despite synthetic polymers currently being used innovatively, many still seek to look into the future of textiles. As Postrel explains, imagine your pockets can charge your phone or your hat could give you directions. The future of textiles is incredibly exciting.

As an avid writer of socio-economics, Postrel expertly showcases her knowledge of the subject. Postrel’s previous books, such as The Future and its Enemies (1998) and The Power of Glamour: Longing and the Art of Visual Persuasion (2013), cover the interconnectedness between culture, technology, and the economy. Postrel has also worked as a columnist for several news sites, is the contributing editor for the magazine Works in Progress, and was a visiting fellow at the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy at Chapman University. This book is a wonderful intellectual contribution that feels like a documentary series, perfectly threading the reader through cultures and regions like a needle through fabric.

Continue reading...

93 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ngl when I wrote Uenuku's love for weaving in Notes on the Holy Sovereign, this scenario always popped in my mind; Yupanqui and Uenuku gossiping (it's just Yupanqui yapping with Uenuku 'ohh'ing his words) during their weaving session.

Yupanqui (in the middle of a complicated pattern): 😰Did you know? That officer impregnated a local girl during a campaign. And not just any local girl, a chief’s daughter! He's risking our army for that very reason! Can you believe that?

Uenuku (also in the middle of a complicated pattern): 😯Oh!

But then Dinga joined (he took care of his mistress, bro was a malewife as the result) and dropped the most unhinged lore he probably got from his visions with the most neutral expression.

Dinga (picking the yarns): 😐He's not the father. He's covering for the girl's brother, whom he falls in love with.

Yupanqui (dropping his needles): what the- OH MY GOD?!?!?!?!?😱

Uenuku (still continuing his pattern): 😲Oh!!

Oh by the way, why do I make the bold and reckless Yupanqui a weaver? That's because I based him after a tradition of the people of Taquile from Peru. They're an expert in textile art, and weaving, particularly knitting their traditional hat named chullo, is actually a proof of manliness.

It's in Spanish, but I'm sure you could research it in internet!

Wait there's an English one as well.

#they're so silly#the weaver brosur#I love them#genshin impact#genshin#natlan#natlan lore#genshin lore#radaedan posting#ancient natlan#xbalanque team#yupanqui#genshin yupanqui#uenuku#genshin uenuku#dinga | maghan#dinga#genshin dinga

10 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Throw back to Halloween 2020 (I've always dressed up every year). I wanted to commemorate my Indigenous Peruvian ancestors that year and dressed up as this silly Paracas textile~☆

Lil’ Meow Meow in Ancient Peru! It just sits there and stares at you!

“ICONOGRAFÍA en la cultura PARACAS NECRÓPOLIS (200 a.C. - 200 d.C.)En general, los textiles precolombinos de Perú muestran una extraordinaria RIQUEZA ICONOGRAFÍCA que alcanza su sofisticada perfección a través de los textiles de la cultura Paracas Necrópolis.Por ejemplo, en este fragmento de tejido de la imagen se nos muestra a un curioso BUHO. Lleva agarradas dos pequeñas FIGURAS HUMANAS. Dentro de su ESTÓMAGO vemos un animal cuadrúpedo con un lomo con protuberancias de saurio y un vientre dentro del cual aparece la imagen de otro animal similar…La iconografía Paracas, independientemente del soporte en que se exprese, evoca temas cosmológicos, mitológicos y se refiere al mismo tiempo a relatos históricos como la conquista y la fundación de asentamientos humanos, de batallas y de celebraciones de ceremonias.Un mundo de ensoñación de una cultura indiscutiblemente admirable.”

(Source: Amantes de las Culturas del Antiguo Peru Facebook page)

#peru#peruvian#peruvian art#textile#paracas#ancient peru#textile art#andean#lil meow meow#cats#indiginous#mixed race

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The discovery, made by Dr. Ruth Shady Solís and her team from the Caral Archaeological Zone (ZAC) of Peru’s Ministry of Culture, offers a glimpse into the prominent role of women in early Andean society."

by Dario Radley April 25, 2025

Archaeologists in Peru have unearthed a well-preserved 5,000-year-old burial of a high-status woman at the Áspero archaeological site—an ancient fishing settlement associated with the Caral civilization, the oldest civilization in the Americas. The discovery, made by Dr. Ruth Shady Solís and her team from the Caral Archaeological Zone (ZAC) of Peru’s Ministry of Culture, offers a glimpse into the prominent role of women in early Andean society.

Remains of a 5000-year-old woman from the Caral civilization. Credit: Ministry of Culture of Peru (Ministerio de Cultura del Perú), via www.gob.pe. Used for non-commercial news coverage purposes.

The burial was unearthed at Huaca de los Ídolos, a public ceremonial building in Áspero, a site on the Peruvian coast in the Barranca province, some 180 kilometers north of Lima. Áspero was one of the principal satellite cities of Caral, a UNESCO World Heritage site, and flourished from 3000 to 1800 BC—contemporaneous with ancient Egypt, Sumer, and China, though it developed in complete isolation.

The remains are those of a woman between the ages of 20 and 35 years old and about 1.5 meters (5 feet) tall. What is remarkable about this find is the state of preservation: archaeologists recovered parts of her skin, nails, and hair—a very uncommon condition for human remains in the region. She was wrapped in multiple layers of cotton fabric and rush mats and covered with an embroidered feather mantle of bright macaw feathers, an art form that is one of the oldest surviving examples of Andean featherwork.

With the body was a rich collection of funerary offerings carefully arranged in two tiers. These consisted of bottle-shaped vessels, reed baskets, a bone needle with intricate incisions, a shell that most likely came from the Amazon basin, weaving tools, a piece of woolen textile, a fishing net, a toucan beak inlaid with green and brown beads, and over thirty sweet potatoes. The items not only point to the high social standing of the woman but also to the advanced trade and cultural networks in which the Caral society was a part, stretching as far as the Amazon.

According to an official statement from the Peruvian State, the discovery of the feathered panel and other exquisitely worked objects “indicates a high level of development of specialized techniques during the Caral Civilization.” The feather artwork, in particular, indicates the symbolic and aesthetic sophistication achieved by this ancient Andean civilization.

Researchers point out that the burial not only attests to the presence of elite female figures in Caral but also aligns with other elite burials unearthed at Áspero over the past several years—such as the “Lady of the Four Tupus” in 2016 and the “Elite Man” in 2019—a pattern showing ceremonial burials among the elite class. The burial group has been compared with the subsequent elite burial practices of La Galgada in the Áncash region, supporting the hypothesis of a society that bestowed special status and power on women.

A multidisciplinary team is now analyzing the woman’s remains and the associated artifacts to further understand her health, diet, cause of death, and the sociocultural use of the objects that accompanied her in burial.

More information: Ministerio de Cultura de Perú

#Peru#Women in history#Archeology#Áspero#the Caral civilization#Dr. Ruth Shady Solís#Huaca de los Ídolos#Archeological discoveries made by women

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

More #TextileTuesday:

“Cotton textile painted with a flounder-like fish.

Chancay style, Peru.”

[Chancay culture: c.1000-1470CE]

On display at American Museum of Natural History

#animals in art#museum visit#AMNH#fish#flat fish#textile#cotton#Peruvian art#South American art#Andean art#Indigenous art#Textile Tuesday#Chancay art

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

INCOMING REDESIGN RAHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH

(gods the Andean textiles are beautiful BUT DAMMIT SO INTRICATE, HELP)

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

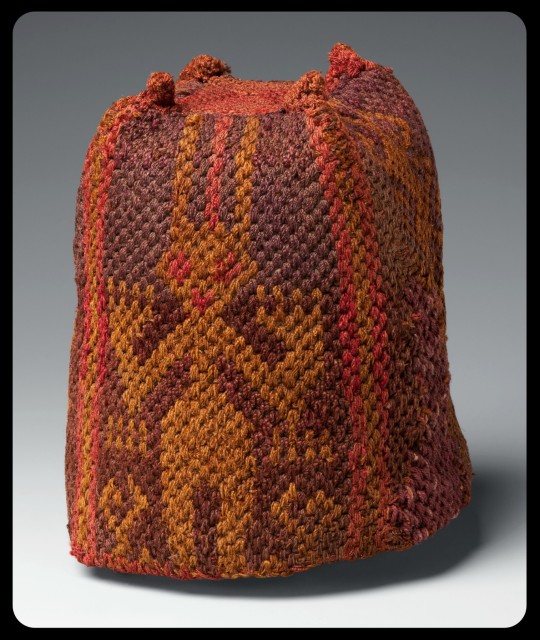

Four-Cornered Hats from Peru and Bolivia, c.600-800 CE: these colorful, finely-woven hats are at least 1,200 years old, and they were crafted from camelid fur

Above: four-cornered hats made by the Wari Empire of Peru (top) and the Tiwanaku culture of Bolivia (bottom) during the 7th-9th centuries CE

Often referred to as "four-cornered hats," caps of this style were widely produced by the ancient Wari and Tiwanaku cultures, located in what is now Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Finely woven, brightly colored hats, customarily featuring a square crown, four sides, and four pointed tips, are most frequently associated with two ancient cultures of the Andes: the Wari and the Tiwanaku. The Wari Empire dominated the south-central highlands and the west coastal regions of what is now Peru from 500–1000 A.D. The Tiwanaku occupied the altiplano (high plain) directly south of Wari-populated areas around the same time, including territory now part of the modern country of Bolivia.

Above: pair of four-cornered hats made by the Wari people of Peru, c.600-900 CE

Both cultures used the hair of local camelids (i.e. llamas, alpacas, or vicuñas) to produce their hats. The hair was harvested, crafted into yarn, and treated with colorful dyes, and the finished yarn was then woven and/or knotted into caps and other textiles. Four-cornered hats from both cultures were often decorated with similar stylistic elements, including geometric patterns (particularly diamonds, crosses, and stepped triangles) and depictions of zoomorphic figures such as birds, lizards, and llamas with wings.

Above: four-cornered hats made by the Tiwanaku people of Bolivia, c.600-900 CE

The two cultures used different techniques to construct/assemble their hats, however:

Although they shared certain technological traditions, such as complex tapestry weaving and knotting techniques, the Wari and the Tiwanaku utilized significantly different construction methods to create four-cornered hats. Wari artists typically fashioned the top and corner peaks as separate parts and later assembled them together. Tiwanaku artists generally knotted from the top down, starting with the top and four peaks, to create a single piece.

Above: a four-cornered hat from Bolivia or Peru, made by either the Tiwanaku or Wari culture, c.500-900 CE

There is evidence to suggest that four-cornered hats were often worn as part of daily life, as this publication explains:

Many have indelible marks of hard usage: wear along the edges and folds, a crusting of hair oil on the inside, remnants of broken chin ties, and ancient mends.

Above: a pair of hats made by the Wari culture of Peru, c.600-800 CE

Above: more hats from the Wari culture of Peru, c.700-900 CE, with colorful tassels decorating the four peaks of each cap

The oldest known/surviving examples of the Andean four-cornered hat date back to nearly 1,700 years ago. They began to appear along the northern coast of Chile at some point during the 4th century CE; these early hats had an elongated design with four short peaks, and they are typically associated with the Tiwanaku culture.

Above: this early example of a four-cornered hat was created by the Tiwanaku culture between 300-700 CE

Why indigenous artifacts should be returned to indigenous cultures.

Sources & More Info:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Four-Cornered Hats 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12

Museum Publication: Andean Four-Cornered Hats (PDF available here)

Emory University: Four-Cornered Pile Hat

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Andean Textiles

#archaeology#artifact#anthropology#history#four-cornered hat#tiwanaku#wari#art#textile art#hats#peru#bolivia#precolumbian#andes#alpaca#fiber art#crafting#pile hats#ancient textiles#indigenous art

217 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tiwanaku

By CLAUDIOLD - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=139063929 and By Pavel Špindler, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55235869

Tiwanaku, from the Spanish Tiahuanaco or Tiahuanacu, is the name given to a civilization from near Lake Titicaca in western modern day Bolivia, South America. It is one of the largest sites discovered in South America, covering nearly 4 square kilometers, and was likely home to between 10,000 and 20,000 people around 800 CE, though it was founded around 110 CE, based on the most reliable carbon dating and the lack of ceramic styles that are older in style. Based on recent studies, a drought in the region contributed to the collapse of the location around 1000 CE.

By Sasha India - Monolito Fraile (Tiwanaku, Bolivia), CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=105046628

Within the site, multiple structures have been excavated, including platform mounds known as Akapana composed of seven levels, Pumapunku, a T-shaped mound with a sunken court that held a monumental structure on top, and kalasasaya, a low platform mound that has a large courtyard surrounded by high stone walls, among others. There is also an area surrounded by a moat and walls that might have been a 'sacred island' or where 'elites' might have lived, with 'commoners' only entering for ceremonial purposes. Evidence indicates that rather than having markets, the various skilled artisans, including those who made pottery, jewelry, and textiles, had their output controlled by the elites except for those things that were needed for day-to-day functioning.

By Arthur Posnansky - https://nrs.lib.harvard.edu/urn-3:doak.reslib:12734425, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=144797434

Andean cultures often venerated mountains, even considering them sacred objects. Tiwanaku is located between two mountains that are considered sacred, Pukara and Chuqi Q'awa. Because of this location, Tiwanaku was a ceremonial center. It also might have been used as an observatory as it was constructed to align with Quimsachata's peak, which would provide a view of how the Milky Way moved around the South Pole with other structures positioned to 'provide optimal views of the sunrise on the Equinox, Summer Solstice, and Winter Solstice'. Some legends of the Aymara, who are thought to be descendants of the Tiwanaku, place Tiwanaku at the center of the universe.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/gateway-to-the-east-the-palaspata-temple-and-the-southeastern-expansion-of-the-tiwanaku-state/FE7182E32049DF2293A54105F589E1D6

Recently, a new discovery of a temple complex about 215 km south-east from the primary site called Palaspata. The distance and location were decided on because the site connected three trading route. The researchers used satellite images to locate an 'unmapped quadrangular plot of land' which was then scanned via lidar to create an approximate 3D map of the site was was about 125 by 145 meters. It contains a 'large, modular building with an integrated, sunken courtyard' and 'represents a gateway node that effectively materialized the power and influence of the Tiwanaku state'. The layout of the site also aligns to the equinoxes.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/gateway-to-the-east-the-palaspata-temple-and-the-southeastern-expansion-of-the-tiwanaku-state/FE7182E32049DF2293A54105F589E1D6

When the team began excavating the site, they found keru cups, or ceremonial cups for a traditional beer made from maize known as chicha. Maize was not grown in the area, but rather in the Cochabamba valleys that were to the east of the site. Pottery sherds from daily use vessels were also found as well as bones from camelids and small- to middle-sized rodents. There were also tools, such as a scraper from a camelid jaw and awls made from long bones. There were also fragments of turquoise and at least one marine shell that would have been used as jewelry. Research of the site shows that it was a 'substantial and complex population centre located in one of the main connecting points between Tiwanaku, the Central Altiplano and the inter-Andean valleys of Cochabamba' and was inhabited between roughly 630 and 950 CE, 'which largely corresponds to the period associated with the Tiwanaku expansion'.

5 notes

·

View notes