#CIMMYT

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

What is CIMMYT? Role, History, Work & Importance in Agriculture

Learn all about CIMMYT – its mission, history, research, achievements, and impact on wheat and maize farming worldwide, including in India. CIMMYT – Feeding the World with Better Wheat and Maize CIMMYT stands for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center. It is a global research center. It works to improve two major food crops: maize (corn) and wheat. These two crops are very…

#agricultural innovation#BISA#BNI wheat#CIMMYT#climate resilient crops#crop breeding research#Green Revolution#ICAR collaboration#Indian agriculture#International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center#maize research#Norman Borlaug#sustainable farming#USAID CIMMYT funding#wheat research#wheat varieties India

0 notes

Text

🖊#Morelos | Impulsa Morelos alianza con CIMMYT para convertir al estado en referente agroecológico SABER MÁS:

0 notes

Text

State-of-the-Art Upgrades at the Kiboko Research Station: What They Mean for Farmers

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) has partnered Kenya Agriculture and Livestock Research Organization (KALRO) to establish a research centre of excellence in the country to promote crop production. on the left – KALRO Board chairman Dr. Thuo Mathenge, Dr. Prasanna Boddupalli, Director CIMMYT and Dr. Eliud Kireger DG KALRO when inaugurating the KALRO-CIMMYT Crops…

#CIMMYT#agricultural development#agricultural excellence#Agricultural Innovation#agricultural research center#agriculture in kenya#Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation#capacity building#crop breeding programs#crop improvement#crop productivity#crop research facility#Crops to End Hunger initiative#Food security#gender inclusivity in research#germplasm storage#GIZ#Kalro#kenyan farmers#Kiboko Research Station#mechanization in agriculture#mechanized breeding#modern agriculture#research modernization#Sub-Saharan Africa#sustainable agriculture#upgraded research facilities

0 notes

Text

Novo Nordisk Foundation Awards $21.1M Grant to CIMMYT

Key Takeaways: Novo Nordisk Foundation grants up to USD 21.1 million to CIMMYT for the CropSustaiN initiative. The initiative aims to develop new wheat varieties to reduce agriculture’s nitrogen footprint. The project could enhance global food security and environmental sustainability. The initiative leverages biological nitrification inhibition (BNI) to curb the use of synthetic nitrogen…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Some goods news for women

How Ivuna women farmers are transforming their lives through seed production

In Ivuna Village, Tanzania, a determined group of women leveraged Vikoba loans, mentorship, and improved sorghum seeds to transform their livelihoods, boost household incomes, and inspire others in their community

By Florian Ndyamukama February 4, 2025

“Five of us borrowed $100 from our Vikoba group and invested it in seed production. Not only did we repay the loan with interest, but we also made a profit,” says Skola Sichalwe, a member of an extraordinary group of women who are transforming their community in Ivuna Village, Momba District. Vikoba groups, grassroots savings and credit associations, operate as informal microfinance systems in rural communities, empowering members with access to small loans and promoting financial independence. These groups often provide a lifeline for women seeking financial stability and growth in rural areas. What began as small savings groups has blossomed into a powerful movement of women breaking barriers and creating a legacy of resilience, innovation, and success. These women—once skeptical about venturing into seed production—are now thriving entrepreneurs, producing quality sorghum seeds and inspiring others in their community to follow their lead. Their journey began with a chance encounter with Miss Zainab Hussein, a passionate seed producer and a youth champion. Her vision and mentorship planted the first seeds of change. “I used to think farming was just about survival,” says Pauline Martin. “But Zainab showed us that with the right knowledge and tools, farming can be a business; a way to change our lives.”

A leap of faith in seed production

Before venturing into the world of seed production, these women were members of Vikoba groups, pooling their savings to lend and borrow money. While this system was helpful for meeting immediate financial needs, it offered little opportunity for growth or long-term investment. Everything changed when Zainab Hussein, an experienced seed producer and youth champion, began attending their meetings. Zainab introduced the group to the potential of improved seeds and the opportunities in seed production. She explained how adopting high-quality sorghum seeds could significantly increase yields and profits, far exceeding the returns from what traditional grain farming could offer. Her visits became a game changer, sparking curiosity and inspiring action among the women. “Zainab’s dedication inspired us,” says Skola Sichalwe. “She didn’t just train us. She believed in us.” As a trainer, mentor, and role model, Zainab played a central role in their transformation. She guided the women through the complexities of seed production, teaching them essential planting techniques, helping them understand TOSCI regulations, and offering practical solutions to challenges they encountered along the way. “She showed us how seed production could not only improve yields but also become a profitable business,” recalls Pauline Martin.

Zainab Hussein, a passionate seed producer and mentor whose guidance and leadership inspired the women to venture into successful seed production and transform their lives. (Photo: CBCC)

Inspired by Zainab’s success, the women saw an opportunity to turn their savings into a sustainable investment. This journey was further supported by the establishment of Youth and Women Quality Centers (YWQCs) under the Center for Behavior Change Communication (CBCC) and the Accelerated Varietal Improvement and Seed Systems in Africa (AVISA) project through CIMMYT. The AVISA project, led by CIMMYT, piloted the YWQC model to address key challenges faced by rural farmers, including limited access to quality seeds, market linkages, and knowledge on improved farming practices. These community-led centers serve as hubs that enhance last-mile seed access by working with seed companies and local producers, ensuring a consistent supply of quality seed. They also facilitate market linkages by connecting farmers with aggregators and off-takers, improving market access and profitability. Additionally, YWQCs provide capacity-building initiatives, equipping youth and women with training in farming practices, local seed production, and business skills. The model further promotes collective action by encouraging farmers to form associations, strengthening their bargaining power and collective marketing efforts. These centers became hubs of opportunity, providing essential infrastructure and resources such as access to certified seeds, extensive training, and advanced farming technologies such as the multi-crop thresher through a cost-sharing arrangement. This technology not only improved efficiency but also ensured the quality of processed seeds, increasing its market value. The project also facilitated crucial linkages between the women and certified seed producers, ensuring they had access to high-quality inputs for their production. In some cases, the project even helped them find markets for their seeds, closing the loop and creating a sustainable business model. And so, they began the journey of seed production, transforming not only their own lives but also their community.

The women’s group plants sorghum using proper spacing techniques, a transformative practice essential for certified seed production, which they adopted after training by CBCC and mentorship from Zainab. (Photo: CBCC)

With loans from their Vikoba groups, they purchased quality seeds and accessed the tools, training, and market linkages provided by the YWQCs. “For years, we saved money but didn’t know what to invest in,” says Halima Kajela. “Seed production gave us a clear opportunity to grow.”

Challenges: A Test of Determination

The journey wasn’t without hurdles. Rodents feasted on the carefully spaced sorghum seeds, a new planting method the women had to adopt for certification. “Broadcasting seeds was easier, but seed production required precise planting and spacing,” Halima explains. “This made it harder to protect the seeds from pests and animals.” Excessive rain washed away seedlings, requiring several rounds of replanting. Cattle from neighboring farms often invaded their fields, causing further damage. Adopting good agronomic practices such as proper spacing, timely weeding, and regular inspections was initially difficult for these women, who were unaccustomed to the disciplined approach required in seed production. Despite these setbacks, the women persevered. With Zainab’s guidance and support from the YWQCs, they implemented solutions like using seed planters which saved time and effort during planting, knapsack sprayers helped combat pests and diseases, and multi-crop threshers simplified the post-harvest process. All these tools saved time and improved efficiency.

Triumph in the fields

And their hard work paid off. In their very first season, the women achieved remarkable success, producing three tons of TARISOR 2, an improved sorghum variety. This achievement not only set them apart from other first-time producers in the district, but also marked the beginning of a transformative journey.

Before the arrival of multi-crop thresher, the women relied on traditional methods to thresh sorghum. Their dedication laid the foundation for their transformation into successful seed producers. (Photo: CBCC)

The impact of their efforts went far beyond the impressive harvest. Ten women became officially registered seed producers with the Tanzania Official Seed Certification Institute (TOSCI), gaining recognition and credibility in the seed production business. Two members received specialized training in seed and fertilizer dealership, equipping them to expand their services and outreach to the community. Four women ventured into distributing essential agricultural inputs, such as maize seeds and hermetic bags, further diversifying their income streams and supporting local farmers. Recognizing the need for efficient post-harvest processing, the group collectively contributed to the purchase of a multi-crop thresher. This crucial investment significantly streamlined their operations, reducing labor and ensuring higher-quality processed seeds. Their efforts quickly translated into financial rewards. Within a short time, they sold one ton of their high-quality seeds, earning over $700. As word of their success spread, demand for their seeds continued to grow, promising even greater opportunities in the seasons ahead.

A ripple effect of change

Their success has had a profound effect on their community. The women’s achievements have earned them respect, and their influence is inspiring others to follow in their footsteps. “Before this, I didn’t believe in seed production,” says Pauline. “But after seeing Zainab’s success and what we achieved, even my husband now supports me fully in this venture.” Their impact extends beyond their fields. Other Vikoba groups have invited them to share their knowledge on seed production, and 10 new women have expressed interest in joining the initiative. By making improved sorghum varieties more accessible, they’ve also helped increase production and reduce food insecurity in their village.

Looking ahead: Planting seeds for the future

Inspired by their success, the women have ambitious plans. With a clear vision for the future, they are determined to expand their seed production enterprise and bring its benefits to a wider community. One of their primary goals is to extend their production to neighboring wards, such as Mkomba. To make their knowledge and improved seed varieties more accessible, they plan to establish demonstration plots closer to the village center. These plots will serve as practical learning sites, allowing more farmers to experience the advantages of using certified seeds and adopting best practices. “The demand for quality seeds is growing,” says Halima Kajela, one of the group members. “We’re committed to meeting that demand and helping more farmers improve their yields.” They are also exploring ways to diversify their operations. They aim to invest in distributing other agricultural inputs and post-harvest services such as threshing, to support farmers in the community and generate additional income. For these women, seed production isn’t just a business—it’s a symbol of empowerment.

#tanzania#Women in agriculture#Youth and Women Quality Centers (YWQCs)#Accelerated Varietal Improvement and Seed Systems in Africa (AVISA)#Sorghum#Tanzania Official Seed Certification Institute (TOSCI)

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

La agricultura de conservación transforma al sector en el sur de África

Por Busani Bafana BULAWAYO, Zimbabue – En las polvorientas llanuras del distrito de Shamva, en el centro de Zimbabue, el campo de maíz de Wilfred Mudavanhu desafía la sequía. Con la última sequía provocadapor el fenómeno de El Niño que ha azotado a varios países del sur de África, el cultivo de maíz de Mudavanhu está floreciendo, gracias a un innovador método de cultivo que ayuda a mantener la humedad en el suelo y promueve la salud de la tierra. Tras cosechar apenas 1,5 toneladas de maíz cada temporada, la cosecha de Mudavanhu aumentó a 2,5 toneladas del grano en la campaña 2023/2024. Mudavanhu es uno de los muchos agricultores de Zimbabue que adoptan la agricultura de conservación, un método que da prioridad a la mínima alteración del suelo, la rotación de cultivos y la conservación de la humedad del suelo. La práctica se complementa con otros métodos, como el control oportuno de las malas hierbas, el acolchado y el cultivo en pequeñas parcelas para obtener altos rendimientos. Los investigadores afirman que el método de la agricultura de conservación está siendo un salvavidas para los agricultores que se enfrentan al cambio climático. Durante más de 20 años, el Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo (CImmyt) ha promovido la investigación sobre la agricultura de conservación en el sur de África con el objetivo de conseguir que los agricultores aumenten el rendimiento de sus cosechas. Según los investigadores, con la agricultura convencional, el rendimiento del maíz de los pequeños agricultores de Zimbabue ha sido a menudo inferior a una tonelada por hectárea. La adopción de prácticas de este tipo de agricultura ha permitido aumentar el rendimiento hasta 90 %. Mientras que en Malaui los agricultores han experimentado un aumento del rendimiento del maíz de hasta 400 %, los cultivos se integran con árboles fijadores de nitrógeno como el Faidherbia albida. En Zambia, el rendimiento del maíz con agricultura convencional ha sido de 1,9 toneladas por hectárea, y ha aumentado a 4,7 toneladas por hectárea cuando los agricultores han utilizado prácticas de agricultura de conservación. Pero más allá de los altos rendimientos, la agricultura de conservación ahorra humedad y mejora la salud del suelo, ofreciendo a los agricultores una solución a largo plazo al creciente problema de la degradación del suelo, una amenaza inminente ante el cambio climático, señalan los investigadores. «A medida que se agrava la crisis climática, la agricultura de conservación se ha convertido en esencial para los agricultores del sur de África, ya que ofrece un enfoque resistente e inteligente desde el punto de vista climático para aumentar la productividad y resistir los impactos del cambio climático, reforzando la seguridad alimentaria sostenible», dijo a IPS Christian Thierfelder, científico principal del Cimmyt. A su juicio, la agricultura de conservación podría cambiar el sistema de cultivo de secano en la región. Unos tres millones de agricultores del sur de África practican este tipo de agricultura, dijo Thierfelder. «Cuanto más afecte el cambio climático, como se ha visto en las recientes sequías, más adoptarán los productores de la agricultura de conservación, porque la forma tradicional de hacer agricultura ya no siempre funcionará», aseguró. El uso de máquinas está atrayendo a los pequeños agricultores a adoptar la agricultura de conservación. El Cimmyt ha investigado el uso de máquinas adecuadas para los sistemas de agricultura de conservación de los pequeños agricultores. Se ha comprobado que las máquinas aumentan los métodos de cultivo intercalado que utilizan los agricultores, al tiempo que abordan los retos de la elevada demanda de mano de obra asociada a la agricultura de conservación. Tradicionalmente, los agricultores pasan horas cavando cuencas de siembra, un proceso que requiere mucho tiempo y mano de obra. La excavadora de cuencas ha mecanizado la fase de preparación de la tierra, reduciendo el número de personas necesarias para excavar las cuencas. Thierfelder explicó que el Cimmyt se ha asociado con proveedores de servicios registrados en Zimbabue y Zambia, que ofrecen servicios de mecanización que mejoran la eficiencia agrícola y reducen la demanda de mano de obra. Una de estas innovaciones, la excavadora de cuencas, una máquina rentable y de bajo consumo energético, reduce la mano de obra hasta en 90 %. Cosmas Chari, agricultor y proveedor de servicios en el distrito zimbabuense de Shamva, solía pasar un día cavando cuencas para plantar, pero ahora tarda una hora utilizando la excavadora de cuencas. Mudavanhu, el productor maicero, se convirtió en proveedor de servicios de mecanización tras integrar la agricultura de conservación con la mecanización. Como proveedor de servicios, Mudavanhu alquila un tractor de dos ruedas, una desgranadora y un desgarrador a otros agricultores que practican la agricultura de conservación. Otro agricultor, Advance Kandimiri, también es proveedor de servicios de mecanización. «Empecé como proveedor de servicios de mecanización en 2022 y adopté la agricultura de conservación utilizando la mecanización», dijo Kandimiri, que compró un tractor, una desgranadora y una plantadora de dos hileras. «La agricultura de conservación es más rentable que la agricultura convencional que practicaba antes de conocer esta agricultura de conservación·, afirmó Kandimiri. Los datos de la investigación del Cimmyt indican que los agricultores que adoptan prácticas de conservación pueden obtener unos ingresos extra de aproximadamente 368 dólares por hectárea como resultado de obtener mayores rendimientos y reducir los costes de los insumos. Agricultura de conservación en la región Los agricultores de África meridional han encontrado el éxito tras adoptar prácticas de agricultura de conservación (AC) con resultados notables. En 2011, durante una visita a Monze, en la provincia meridional de Zambia, Gertrude Banda observó de primera mano los importantes beneficios de la AC. Los agricultores que practican la AC desde hace más de siete años demostraron cómo la siembra de cultivos sin laboreo mediante un ripper de tracción animal permitía reducir la mano de obra en la preparación de la tierra y mejorar el rendimiento de los cultivos. Banda afirma que esta experiencia la motivó a adoptar la AC en su propia explotación de nueve hectáreas, donde cultiva caupís (Vigna unguiculata), cacahuetes y soja. Practica la rotación de cultivos, alternando el maíz con diversas leguminosas para mejorar la fertilidad del suelo y el rendimiento de las cosechas. Además, utiliza residuos de cacahuete y la leguminosa caupí para alimentar al ganado. Ganó unos 5000 dólares con la venta de su cosecha de soja. «En la actualidad, toda mi explotación sigue los principios de la AC», afirma Banda. «Todos mis cultivos se plantan en hileras y hago rotar el maíz con diversas leguminosas para mantener la salud del suelo», añade. Más de 65 000 agricultores de Malaui y 50 000 de Zambia han adoptado la AC, según el Cimmyt, cuyas investigaciones demuestran que la educación de los agricultores, la formación y la orientación técnica son vitales para que los agricultores hagan el cambio. Sin embargo, la adopción generalizada de la agricultura de conservación sigue siendo escasa a pesar de sus reconocidas ventajas. Según Hambulo Ngoma, economista agrícola del Cimmyt, los pequeños agricultores tienen dificultades para acceder a insumos y equipos. Además, «los agricultores tienen conocimientos limitados sobre el control eficaz de las malas hierbas y se enfrentan a incertidumbres sobre el rendimiento a corto plazo, lo que puede desalentar una práctica constante», dijo Ngoma. Aunque la AC ha demostrado su valía, «los índices de adopción siguen siendo relativamente bajos en África meridional», afirma Ngoma, y añade: “Muchos agricultores carecen de recursos para invertir en las herramientas y la formación necesarias para una aplicación eficaz”. Asociaciones fructíferas para promover la agricultura de conservación Blessing Mhlanga, agrónomo de sistemas de cultivo del programa de Sistemas Agroalimentarios Sostenibles del Cimmyt, afirmó que el éxito de la AC va más allá de la tecnología y las técnicas, sino que depende de la educación y de la inclusión de los principios de la AC en las políticas nacionales. En Zambia, por ejemplo, el Cimmyt, en colaboración con la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura (FAO), ayudó a diseñar una estrategia de mecanización que ha allanado el camino para que la AC mecanizada se incorpore a los programas agrícolas dirigidos por el gobierno. «Tecnologías como la intensificación con gliricidia, un árbol de rápido crecimiento que fija el nitrógeno, el cultivo en franjas y las camas permanentemente elevadas forman parte ahora de la agenda agrícola nacional de Zambia», explicó Mhlanga. Añadió que la adopción de la AC por parte de los pequeños agricultores puede ser transformadora, especialmente en regiones que dependen del cultivo de secano. Mhlanga afirmó que, con más de 250 millones de hectáreas de tierras dedicadas a la agricultura de conservación en todo el mundo y un índice de adopción de estas prácticas que aumenta en 10 millones de hectáreas cada año, el futuro de la agricultura de conservación es prometedor. Sin embargo, puntualizó. queda mucho por hacer para proporcionar a los pequeños agricultores como Mudavanhu las herramientas y los conocimientos adecuados para adoptar plenamente la agricultura de conservación. T: MF / ED: EG Read the full article

0 notes

Text

MARGARITA ES UNA GOBERNADORA DE TERRITORIO: RODRIGO ARREDONDO

*La acompaña a “Morelos Agroecológico: Integración y Elaboración de mapas de fertilidad para el estado de Morelos y Firma de Convenio Gobierno del estado -CIMMYT” El presidente de Cuautla, Rodrigo Arredondo, acompañó a la Gobernadora de Morelos, Margarita González Saravia al programa “Morelos Agroecológico: Integración y Elaboración de mapas de fertilidad para el estado de Morelos y Firma de…

0 notes

Text

Latest Jobs at Eldoret Water and Sanitation Company Limited (ELDOWAS)

Managing Director

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/eldoret-water-and-sanitation-company-limited-eldowas-eldoret-333-managing-director/

General Manager, Technical Services

General Manager, Finance & Strategy

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/eldoret-water-and-sanitation-company-limited-eldowas-eldoret-333-general-manager-finance-strategy/

Maintenance Officer(Electro-Mechanical)

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/eldoret-water-and-sanitation-company-limited-eldowas-eldoret-333-maintenance-officerelectro-mechanical/

Jobs at World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF)

Program Analyst CIMMYT

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/world-agroforestry-centre-icraf-nairobi-333-program-analyst-cimmyt/

Project Coordinator

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/world-agroforestry-centre-icraf-nairobi-333-project-coordinator/

Data Specialist – Agronomic Analytics and Modeling CIMMYT

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/world-agroforestry-centre-icraf-nairobi-333-data-specialist-agronomic-analytics-and-modeling-cimmyt/

Occupational Health and Safety Officer CIMMYT

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/world-agroforestry-centre-icraf-nairobi-333-occupational-health-and-safety-officer-cimmyt/

Human Resource Assistant CIMMYT

https://www.mercymaiyo.com/job/world-agroforestry-centre-icraf-nairobi-333-human-resource-assistant-cimmyt/

0 notes

Text

Capacita Agricultura a ejidatarios de Michoacán en el manejo sostenible del suelo

Capacita #Agricultura a ejidatarios de #Michoacán en el manejo sostenible del suelo

El objetivo es propiciar un entorno de concientización y educación sobre el cuidado del recurso suelo en la entidad, para alcanzar el objetivo del Gobierno de México de garantizar la seguridad alimentaria del país. Productores de los municipios de Cuitzeo y Huandacareo, Michoacán, se sumaron al proceso de formación del programa Doctores del Suelo, iniciativa impulsada por la Secretaría de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Bill Gates hat die Kontrolle über die globale Produktion und Lagerung von Saatgut übernommen

Bill Gates hat die Kontrolle über die globale Produktion und Lagerung von Saatgut übernommen

Bill Gates besitzt nicht nur das meiste Ackerland in Amerika… Er hat auch die Kontrolle über die globale Produktion und Lagerung von Saatgut übernommen… Seit beginn der neolithischen Revolution vor etwa 10.000 Jahren haben Bauern und Gemeinden daran gearbeitet, den Ertrag, den Geschmack, die Ernährung und andere Eigenschaften von Saatgut zu verbessern. Sie haben das Wissen über die…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

CIMMYT releases 12 new maize lines to boost productivity for smallholder farmers

New Post has been published on https://newscheckz.com/cimmyt-releases-12-new-maize-lines-to-boost-productivity-for-smallholder-farmers/

CIMMYT releases 12 new maize lines to boost productivity for smallholder farmers

The International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) has released a set of 12 new CIMMYT maize lines (CMLs).

These lines were developed at various breeding locations of CIMMYT’s Global Maize program by a multi-disciplinary team of scientists in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia.

The lines are adapted to the tropical maize production environments targeted by CIMMYT and partner institutions.

CIMMYT seeks to develop improved maize inbred lines in different product profiles, with superior performance and multiple stress tolerance to improve maize productivity for smallholder farmers.

CMLs are released after intensive evaluation in hybrid combinations under various abiotic and biotic stresses, besides optimum conditions. Suitability as either seed or pollen parent is also thoroughly evaluated.

To increase the utilization of the CMLs in maize breeding programs of partner institutions, all the new CMLs have been tested for their heterotic behavior and have been assigned to specific heterotic groups of CIMMYT: A and B.

As a new practice, the heterotic group assignment is included in the name of each CML, after the CML number — for example, CML604A or CML605B.

Release of a CML does not guarantee high combining ability or per se performance in all environments.

Rather, it indicates that the line is promising or useful as a parent for pedigree breeding or as a potential parent of hybrid combinations for specific mega-environments.

The description of the lines includes heterotic group classification, along with information on their specific strengths, and their combining ability with some of the widely used CMLs or CIMMYT lines.

0 notes

Video

Experimental line of provitamin A-enriched orange maize, harvested in Zambia by International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center Via Flickr:

#Africa#África#África Austral#África sub-sahariana#asociación#beta-carotene#beta-caroteno#biofortificación#biofortificado#biofortification#biofortified#campo#CIMMYT#cob#colaboración#collaboration#color#color anaranjado#colour#corn#ear#enhanced#experimental#field#HarvestPlus#improved variety#investigación#line#línea#maíz

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise of Pigeon Pea Farming: How Festus Muthoka Transformed His Farm with the New Mituki Variety in Machakos

Discover how Festus Muthoka transformed his farm in Machakos County by adopting the Mituki pigeon pea variety, achieving higher yields and income in challenging farming conditions. Learn more about this game-changing crop. Explore the benefits of the Mituki pigeon pea variety, a drought-resistant crop that matures quickly and offers multiple harvests per year. See how farmers in Kenya are…

#CIMMYT#agricultural innovations#climate-resilient crops#crop innovation#Drought-resistant crops#dryland farming#farmer success stories.#farming in kenya#Festus Muthoka#Food security#green pigeon pea#high-yield crops#Kalro#Kenyan agriculture#Machakos County farming#Mituki pigeon pea#multiple harvests#pigeon pea farming#pigeon pea variety#seed purity#sustainable farming

0 notes

Text

अमेरिकी वैज्ञानिक टीम बिहार में बनाएगी न्यू कृषि मॉडल, पसंद आया बिहार का जलवायु|

पटना। विश्व के कई देश कृषि क्षेत्र को बढ़ावा देने की जुगत में लगे हुए हैं। लेकिन जलवायु अनुकूल न होने के कारण कई स्थानों पर खेती को मदद नहीं मिल पाती है।

अमेरिकन वैज्ञानिकों की टीम भी भारत में कृषि मॉडल बनाने के लिए सर्वे कर रही है। अमेरिकन वैज्ञानिकों की टीम को बिहार की जलवायु पसंद आयी है। वह जल्दी ही बिहार में न्यू कृषि मॉडल बनाने जा रहे हैं, जिससे खेती और किसानों फायदा मिलेगा।

बिहार में बीसा समिट (BISA-CIMMYT) की तरफ से जलवायु अनुकूल कृषि कार्यक्रम चलाया जा रहा है। इस कार्यक्रम को बिहार सरकार ने सभी 38 जिलों में लागू कर दिया है। बीते तीन दिनों से अमेरिका के कोर्नेल विश्वविद्यालय से वैज्ञानिकों की टीम बिहार में जलवायु अनुकूल कृषि कार्यक्रम संचालित कर रही है। इस दौरान अमेरिकी वैज्ञानिकों की टीम को बिहार की जलवायु बेहद पसंद आयी है।ये भी पढ़े: प्राकृतिक खेती ही सबसे श्रेयस्कर : ‘सूरत मॉडल’

टीम ने जुटाई फसल अवशेष प्रबंधन की जानकारी

– अमेरिकन वैज्ञानिकों की टीम ने बिहार के भगवतपुर जिले के एक गांव, जो की सीआरए (Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRA) Programme under Jal-Jeevan-Haryali Programme) यानी जलवायु अनुकूल कृषि कार्यक्रम के जल-जीवन-हरियाली कार्यक्रम के अंतर्गत आता है, का दौरा किया है। यहां मुआयना के बाद टीम ने फसल अवशेष प्रबंधन (Crop Residue Management) की जानकारी भी जुटाई है। इसके अलावा बीसा पूसा ( बोरोलॉग इंस्टीच्यूट फॉर साऊथ एशिया – Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA)) में ��ल रहे लांग ट्रर्म ट्राइल्स, जीरो टिलेज विधि और मेड़ विधि के बारे में भी महत्वपूर्ण जानकारियां जुटाई हैं। जल्दी ही बिहार में इसका असर देखने को मिलेगा।ये भी पढ़े: फसलों के अवशेषों के दाम देगी योगी सरकार

– बिहार सरकार द्वारा चलाए जा रहे जलवायु अनुकूल कृषि कार्यक्रम की पूरे विश्व में सराहना हो रही है। यहां आकर कई देशों के वैज्ञानिक जानकारी प्राप्त कर रहे हैं। बिहार समेत देश के अन्य कई कृषि संस्थानों के साथ मिलकर जलवायु अनुकूल कृषि कार्यक्रम किसानों तक पहुंच रहे हैं। इससे फसल का विविधीकरण करके और नई तकनीकी का उपयोग करके किसानों को फायदा देने की योजना बनाई जा रही है। जो आगामी दिनों में प्रभावी रूप से दिखाई देगी। —— लोकेन्द्र नरवार

Source अमेरिकी वैज्ञानिक टीम बिहार में बनाएगी न्यू कृषि मॉडल, पसंद आया बिहार का जलवायु

#BISA-CIMMYT#Borlaug Institute for South Asia (BISA)#Cornell University#crop residue management#अमेरिकन वैज्ञानिकों की टीम#अमेरिकी वैज्ञानिक टीम बिहार में बनाएगी न्यू कृषि मॉडल#कृषि संस्थानों#कोर्नेल विश्वविद्यालय

0 notes

Photo

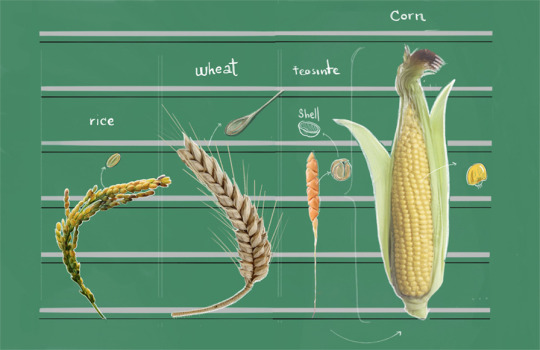

Maize: From Mexico to the world

For Mexicans, the “children of corn,” maize is entwined in life, history and tradition. It is not just a crop; it is central to their identity. By Matthew O'Leary May 20, 2016

EL BATAN, Mexico (CIMMYT) – For Mexicans, the “children of corn,” maize is entwined in life, history and tradition. It is not just a crop; it is central to their identity.

Even today, despite political and economic policies that have led Mexico to import one-third of its maize, maize farming continues to be deeply woven into the traditions and culture of rural communities. Furthermore, maize production and pricing are important to both food security and political stability in Mexico.

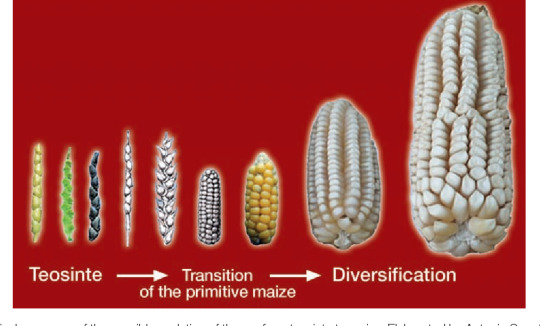

One of humanity’s greatest agronomic achievements, maize is the most widely produced crop in the world. According to the head of CIMMYT’s maize germplasm bank, senior scientist Denise Costich, there is broad scientific consensus that maize originated in Mexico, which is home to a rich diversity of varieties that has evolved over thousands of years of domestication.

The miracle of maize’s birth is widely debated in science. However, it is agreed that teosinte (a type of grass) is one of its genetic ancestors. What is unique is that maize’s evolution advanced at the hands of farmers. Ancient Mesoamerican farmers realized this genetic mutation of teosinte resembled food and saved seeds from their best cobs to plant the next crop. Through generations of selective breeding based on the varying preferences of farmers and influenced by different climates and geography, maize evolved into a plant species full of diversity.

The term “maize” is derived from the ancient word mahiz from the Taino language (a now extinct Arawakan language) of the indigenous people of pre-Columbian America. Archeological evidence indicates Mexico’s ancient Mayan, Aztec and Olmec civilizations depended on maize as the basis of their diet and was their most revered crop.

As Popol Vuh, the Mayan creation story, goes, the creator deities made the first humans from white maize hidden inside a mountain under an immovable rock. To access this maize seed, a rain deity split open the rock using a bolt of lightning in the form of an axe. This burned some of the maize, creating the other three grain colors, yellow, black and red. The creator deities took the grain and ground it into dough and used it to produce humankind.

Many Mesoamerican legends revolve around maize, and its image appears in the region’s crafts, murals and hieroglyphs. Mayas even prayed to maize gods to ensure lush crops: the tonsured maize god’s head symbolizes a maize cob, with a small crest of hair representing the tassel. The foliated maize god represents a still young, tender, green maize ear.

Maize was the staple food in ancient Mesoamerica and fed both nobles and commoners. They even developed a way of processing it to improve quality. Nixtamalization is the Nahuatl word for steeping and cooking maize in water to which ash or slaked lime (calcium hydroxide) has been added. Nixtamalized maize is more easily ground and has greater nutritional value, for the process makes vitamin B3 more bioavailable and reduces mycotoxins. Nixtamalization is still used today and CIMMYT is currently promoting it in Africa to combat nutrient deficiency.

White hybrid maize (produced through cross pollination) in Mexico has been bred for making tortillas with good industrial quality and taste. However, many Mexicans consider tortillas made from landraces (native maize varieties) to be the gold standard of quality.

“Many farmers, even those growing hybrid maize for sale, still grow small patches of the local maize landrace for home consumption,” noted CIMMYT Landrace Improvement Coordinator Martha Willcox. “However, as people migrate away from farms, and the number of hectares of landraces decrease, the biodiversity of maize suffers.”

Diversity at the heart of Mexican maize

The high level of maize diversity in Mexico is due to its varied geography and culture. As farmers selected the best maize for their specific environments and uses, maize diverged into distinct races, according to Costich. At present there are 59 unique Mexican landraces recorded.

https://www.cimmyt.org/blogs/maize-from-mexico-to-the-world/

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scientists at the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) in Sonora are focused on developing wheat varieties which can better cope with drought, rising temperatures and excessive rainfall. In other words, wheat that can thrive under the extreme and unpredictable weather conditions farmers are experiencing globally due to the rapidly warming planet.

Diversity is crucial to breeding resilience and adaptability, which is why scientists are turning to wild and forgotten wheat varieties from across the world to search for those with temperature- and drought-tolerant traits such as deep roots, waxy leaves and stress hormones.Wheat is the most widely consumed grain globally, accounting for a fifth of our carbohydrate and protein intake, and is farmed in every inhabited continent to make bread, chapatis, pasta, couscous, noodles and pastries eaten by billions of people. The wheat we eat today can be traced back to wild grasses domesticated by Neolithic farmers in western Asia and northern Africa, coming to Mexico relatively recently with Spanish settlers.

Wheat does best in temperate climates, but no matter where humans took seeds, wheat adapted to the local ecosystem, evolving over generations as each variety or landrace developed good and bad quirks.

Diversity was the norm, and before the second world war thousands of landraces were being cultivated across the globe, often side by side with other crops – which partially buffered communities from ecological disasters such as disease epidemics and extreme weather. But yields were often low as many wheats were tall and gangly, and would be harvested too early or else tumble in windy conditions.

Global wheat production tripled after the Green Revolution in the mid-20th century after Norman Borlaug, an American plant pathologist deployed to Mexico by the Rockefeller Foundation, used a semi-dwarf gene from a Japanese wheat to create shorter stem varieties which when farmed with fertiliser and water improved yields beyond anyone’s dreams.

This was the birth of extractive industrial agriculture and Borlaug’s discoveries in Mexico changed the way the world farmed wheat, rice and many other crops.

Uniformity, standardisation, and fossil fuel-driven technologies became the gold standard and Borlaug was awarded the Nobel peace prize as malnutrition declined. But the loss of diversity in crops, ecosystems and traditional sustainable practices came at a huge environmental and human cost. And now the climate crisis is making us pay.

“After the Green Revolution the focus was on breeding high-yield disease-resistant specialists for different regions, but the mega-varieties were not bred to cope with unpredictable climate conditions. Now we need generalists, and there’s enough diversity to cope with unpredictable climate events – we just need to find and exploit it, but funding is an issue,” said Matthew Reynolds, head of physiology at CIMMYT’s wheat program.

11 notes

·

View notes