#Isolat Pattern

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

So the 90's were a crazy time for us growing up! Lets start with Music.. Were You A Fan Of? The Backstreet Boys The Spice Girls STEPS No Doubt N*Sync Oasis Weezer The Vengaboys TLC Destiny's Child Hanson FIVE Madonna B*Witched S Club 7 M2M 98 Degrees Ricky Martin Sonique Sugar Ray Billie Piper Vitamin C Play

What about 90's Movies.. Were you a Fan of...

Clueless Jurassic Park Pulp Fiction Titanic Home Alone The Lion King Pretty Woman 10 Things I Hate About You Empire Records Space Jam Dumb and Dumber Aladdin Wayne's World Ace Ventura American Pie Hocus Pocus Matilda She's All That Bring It On The Craft Cruel Intentions Never Been Kissed Jawbreaker Spice World Can'y Hardly Wait I Know What You Did Last Summer Romy and Michele's High School Reunion Drive Me Crazy

90's TOYS, Did you have or want these?

YoYo Play-Doh Super Soaker Betty Spaghetty Gameboy Colour Tamogotchi Bop It Furby Moon Shoes Hit Clips Mouse Trap Koosh Balls Sky Dancers Slammer Whammers Spice Girls Dolls Slime Etch a Sketch Easy Bake Oven Pokemon Trading Card Game Littlest Pet Shop Street Sharks Mighty Max Sylvian Families Beanie Babies Silly Putty Brain Warp Atari Jaguar Groovy Girls Nintendo 64 Magic Mitt Slinkies Polly Pocket Poo-Chi Rainbow Brite GakSplat Doodle Bear Skip It Trolls

How About 90's Fashion.. What did you think of...

Crop Tops I was just a kid in the 90s, that wasn’t my style. I also remember thinking I didn’t want to show my stomach. Studded Belts I had one in the 2000s. Scrunchies Loved ‘em. Still do. Butterfly Clips Loved those as well and still do. Chokers I don’t like things around my neck like that. Plaid, Pleated Mini Skirts Not my style, personally, but I liked some of the looks. Slip Dresses I didn’t wear stuff like that. Long, Leather Jacket Blazers Didn’t wear ‘em, but they’re cool. You look badass in a leather jacket haha. Chain Belts Not my thing. Boob Tubes Is that the same as a tube top? Not a fan. Hip Hugger Jeans Again, I didn’t wear that stuff as a kid but that was the popular style and I probably liked it when seeing celebrities wear them and whatnot. Camo Pants Nah. Mood Rings Those were cool. Scarf Tops Definitely not my style. Bandanas I didn’t wear them. Crushed Velvet Nah. Platform Sneakers I thought they were kinda cool. Spaghetti Straps Cute. Corsets Not my thing. Pedal Pushers I wore ‘em. Were you a fan of these 90's Television Shows Spongebob Square Pants Animaniacs Dexters Laboratory Hey Arnold Power Puff Girls Barbie Rocko's Modern Life Batman Ren and Stimpy Ed, Edd and Eddy Johnny Bravo Sesame Street Arthur Ducktales Doug Catdog Angry Beavers As Told By Ginger Tiny Toon Adventures Looney Tunes Aaahhh! Real Monsters Talespin Daria Beavis and Butthead The Wild Thornberrys King Of The Hill Futurama Digimon Pokemon Captain Planet The Simpsons Cow and Chicken Blinky Bill Rugrats Sylvester and Tweety Sonic The Hedgehog Dragontales Clifford The Dog Random 90's things. Thoughts on... Checkered Kitchenware Nostalgic Every restaurant had that it seemed. Cartoon Character Coffee Mugs and Cookie Jars Cute, I like stuff like that. Celestial Prints around the house Nah. Lava Lamps I had one; I thought they were cool. Candle Holders I don’t really have any thoughts on that. Coca Cola Tins Or that. Blonde Wood Furniture I don’t know what that is. Tape Decks Discmans to play music It was the cool thing at the time. Oversized Headphones They hurt my ears. Cd's (Singles) I loved CDs back in the day. Pastel coloured plates Cute. A fancy dish for the butter Nice. A Miracle Mop Elizabeth Taylors 'White Diamonds' in your mothers room I don’t think she wore that. Picture frames that were also photo albums Cool. a fancy decorative plate that sat in the kitchen and no one was to use it We didn’t have one. topiaries It’s pretty cool what you can make out of shrubs and trees. a basket for the mail Useful? crazy patterned bed sheets Fun. an ab isolater your parents kept in a spare room or the shed Didn’t have one. McDonalds collector cups and disney figurines Loved those. We still have a lot of ours. slime time on nickelodeon I always wanted to get slimed as a kid. MTV actually had music The good ol’ days. I loved watching TRL.

video hits on television Good times. bath oil beads Didn’t use ‘em. overalls and doc martens I liked overalls. super mario Loved Super Mario. Still do. bubble beeper I didn’t have one. nokia brick mobile phones Didn’t have one either. Man, we’ve come a long way with cellphones. pogos bangles I liked those. mary kate and ashley olsen I was a huge fan, I watched all their stuff and had all their movies on VHS. glow worms hair crimper machine It was cool at the time. I styled my hair for picture day in elementary school one year. hair straighteners Liked those as well. clarissa explains it all I liked it. barbie happy meal toys Those were fun to get. I was obsessed with Barbies. gel and glitter pens Loved those. animal shaped erasers Those and scented ones were fun to have. echo microphones puppy surprise (the dog toys that had puppies in its belly) I had one, such a freaky thing. Goosebumps novels I was obsessed with Goosebumps. My Little Pony Wasn’t into that.

Baby Born Dolls I don’t think I had one. Barbie Dolls ObSESSED. I had to have everything and would play for hours and hours everyday. Crayola Mini Stampers Cool. Snake on mobile Nokias I think I might have played before. Carebears Cute, I liked Carebears. Still do. I find myself relating to Grumpy Bear nowadays, ha.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

v4w.enko

Reminiscent of Aphex Twin and Autechre, Kiev’s Evgeniy Vaschenko, aka V4W.ENKO, draws inspiration from nature and his background in architectural studies.

The Ukrainian experimentalist came to our attention via SHAPE, a Pan-European promotional project for experimental music that we recently reported on.

v4w.enko’s visual and audio output consists of “generative music compositions”, produced via algorithms that are created in real time. Intrigued by what this all means, we talked to the glitchy producer to get some answers….

What sort of music were you exposed to when you were growing up?

v4w.enko: It was a nice mixture. I have to say this will be just from my memory, because of course my perception was affected by much more different sounds that I cannot remember. For example, the most influential period for a child is when he’s 5 years old, but it is really hard to know what sorts of music was playing then. In general I remember I had a great music library formed by tapes and vinyls that were collected by my mother and father until I was 5-7 years old. Maybe this could be explained as the background music during my growing process.

Later there was a period for me when I started selecting the music I heard in a more deliberate way. I remember I started to select music in a more precise and really selective way. I started to be shaped by the music I heard as I noticed music started to influence my lifestyle. And then after hearing some records I started to try record my own.

Pop acts such as Michael Jackson, Peter Gabriel, or even a rhythm section of Queen to punk rock like Grajdanskaya Oborona or Seed Wishes, and yes, all styles of nice grunge such as Nirvana or even Silverchair and black metal like Сradle of Filth and Catatonia. Sepultura, of course my most favourite death metal group. The Beatles, only a little. The Doors. Funk music also had a special influence on me, as well as intelligent styles of post-rock bands such as Morphine, The Cure and Joy Division.

But the bands I listened to the most were Sonic Youth, Pink Floyd, King Crimson. Later I came across John Zorn and Patitucci. In classical music I prefer Chopin, Mozart and Arvo Part. Classical music led me to microtonal music. Later I got into the universe of electronic music which inspired me a lot to create my own music. Now I discover new styles almost each day or every time I have a listening experience. Maybe now it’s across-genres time.

When did you start making your own music and what was it like to begin with?

Of course in a band – actually, in a number of bands – when I was 15-17. After I came across electronic music I started trying my own experiments with electronic instruments.

What equipment do you use now?

Max/MSP and Jitter software. Programmed patches and MSP Synths. Now I just mix a few layers of real time generated algorithms with a mixer. If I work on sound design I combine several layers in various offline mixing solutions softwares. In this area I allow myself to use recorded sounds of nature and human/urban environments, as well as analog synthesizer effects.

Regarding the sound of V4W.ENKO, I keep it in the fixed scope of the programmed-only: algorithmically synthesised music with computer.

What are the top things you’d suggest music fans visiting Ukraine should go and see/do/eat/drink?

See: nature Do: clubbing Eat: borsch Drink: samogon

Can you send us a photo of the view from your window?

Hisilicon Balong

Which Ukrainian artists should we keep an eye on this 2017?

The first that come to my mind are: .at/on, Ujif_Notfound, Nikolaienko, Sommer, Ostudinov, Mokri Dereva, Midi8, Dunaewsky69, Edward Sol, Kotra, Alla Zagaykevich, Strukturator, Quarkmonk, Tolkachev, Motoblok, Ksztalt, George Babanski, Andrey Kiritchenko, Yamabushi, Maxim Werner, Diser Tapes, Zavoloka, Zavgosp, Neither Famous Nor Rich, Sport and Music, and more.

What are your favourite albums of the year so far?

The albums that I played the most on my headphones are not from 2017 but were released in 2015-16. Basically music comes to my listening experience half or one year after the release dates.

Rrose x Tujurikkuja, Yaporigami, Isolat Pattern, Krx-V.A., Jemapur, Young Juvenile Youth, Bad Sector, 14Circles and Sanmi, namely.

Where in the world would you most like to perform?

Maybe it is because I have performed in a number of countries that I have some genuine interest in performing in very different urban centres around the world such as Lima, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, New York, Miami, Casablanca and Bangkok.

#14Circles#Andrey Kiritchenko#aphex twin#Autechre#Bad Sector#Diser Tapes#Dunaewsky69#Evgeniy Vaschenko#experimental#George Babanski#Isolat Pattern#Jemapur#kiev#Ksztalt#Maxim Werner#Motoblok#Neither Famous Nor Rich#Nikolaienko#Ostudinov#Quarkmonk#Sanmi#Sport and Music#Strukturator#Tolkachev#ukraine#v4w.enko#Yamabushi#Yaporigami#Young Juvenile Youth#Zavoloka

0 notes

Text

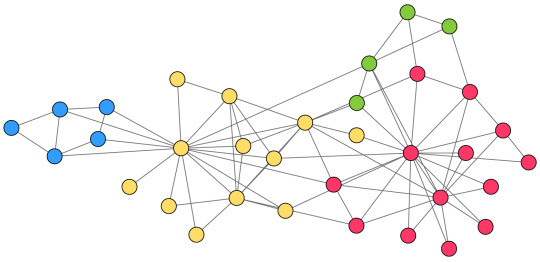

Reticulate Science

On Specialization and Interdisciplinarity

Over the past few decades a number of ideas that I call “big picture research programs” have appeared—big history, astrobiology, the overview effect, existential risk, SETI, the Drake equation, the Fermi paradox, the Anthropocene. Many of these are neither “sciences” nor “disciplines” in the conventional sense, but they represent the effort of scientists and philosophers to recover a comprehensive approach to knowledge in the wake of scientific specialization since the scientific revolution.

Is it possible to constitute a new science at this late date in the development of science? And is it possible to constitute a “big picture” discipline that takes in a wider scope rather than narrowing the scope of inquiry, as we find in specialization? What does it mean to create a “big picture” research program, and how is this big picture related to specialization? Thinking about these questions I wrote about the possibility of “big picture” disciplines a few years ago in Is it possible to specialize in the big picture?

I have come to realize that the problem of big picture sciences is isolatable from the problem of specialization and interdisciplinarity, as big picture disciplines, when they appear, effectively constitute new specialist disciplines. Moreover, I also came to realize the limits of what can be accomplished by interdisciplinary sciences, which I wrote about in The Limits of Interdisciplinarity. Science has experienced its rapid growth since the scientific revolution partly precisely because of specialization and the use of scientific abstractions specific to a given discipline—abstractions that are not as effective in other disciplines, which must severally converge on their own optimal abstractions. Specialization, too, has its limitations, but the limitations of specialization and the limitations of interdisciplinarity are complementary, so that each may inform the other; it is not a matter of the inevitable influence in a single direction of one approach upon the other.

The growth of science and of scientific knowledge has usually meant the fissioning of science into ever more specialized disciplines, so that not only are there divisions between biology, geology, physics, astronomy, and so on, but also an increasing number of divisions within each of these specializations, so that within biology there is limnology, virology, mycology, and so on, and within mycology are the further specializations of lichenology, mycotoxicology, and paleomycology. On this basis we could predict that a science of paleolichenology will be formulated at some point, and that there may well be further specializations within paleolichenology (for example, specializing in different periods of paleohistory). We have not yet encountered the limits of the progressive division of the sciences into narrower specializations, and we do not know if there is a limit.

While it is easy to muse about the possibility of a ultimate, final science that will collect all the special sciences together into one, great interdisciplinary whole, it is unlikely that this state of affairs will ever come about. Or, rather, if it does come about, it would be the end of science and the end of scientific inquiry; the final form of science would mean there would be no more growth of science or scientific knowledge.

Just as science forges ahead through inductive generalization, despite the philosophical problems that beset the model of inductive knowledge, and we must assume that the future will be at least somewhat like the past, because, without this assumption, we would have to abandon our efforts to expand our knowledge, and take refuge in either quietism or nihilism. We can take this same view of the overall structure of science, allowing more and narrower specializations to grow like weeds, because this has been the pattern of inquiry that has yielded results in the past. And the flowering of specialization calls forth in turn a response.

Even as science fissions into ever more narrowly defined specializations, the need is felt for a more comprehensive approach to knowledge, and attempts are made to join together several narrow specializations into inter-disciplinary sciences. Newly formed inter-disciplinary sciences in their turn constitute new special sciences, so that science on the whole takes on a reticulate structure in which there are sciences fissioning into narrower disciplines at the same time as multiple specializations are being collected into inter-disciplinary sciences. A bird’s eye view of all these interconnecting disciplines might be called reticulate science.

Not all novel scientific disciplines are narrower specializations within existing disciplines; in some cases it is not clear whether a novel science is a narrower specialization within, or a more comprehensive extension of, the science from which it has been derived. Is astrobiology a specialization within biology, or is it a more comprehensive discipline that includes traditional biology together with non-biological knowledge? Charles S. Cockell gave this definition:

“���astrobiology is the interdisciplinary science that sits at the interface between biological sciences, earth sciences and space sciences—exploring questions that seek to understand the phenomenon of life in its wide universal environment.”

Thus Cockell defines astrobiology in terms of its interdisciplinarity, which both draws together the work of many special sciences while directing them toward a novel epistemic imperative.

If astrobiology is the intersection of biology, earth sciences, and space sciences, does this make it more or less comprehensive than traditional biology? Is big history a specialization within history, or is it a more comprehensive discipline derived from history, but which transcends history? Is big history a more comprehensive conception of history than traditional history? Does it represent a more comprehensive conception of knowledge? Is the concept of the Anthropocene contained with geological chronology, or must it also draw from biology and even the humanities? Is the Drake equation part of SETI, part of big history, part of astrobiology, or does it (or ought it to) stand on its own?

One might speak of a class of sciences that are, at once, both derivative of earlier models while expanding and extending the scope of these models. Analogous to astrobiology, big history appears to be derived from earlier history—a daughter discipline of history, as it were—but it is also an extension of history, not only in terms of methods of research and kinds of evidence employed, but also in terms of synthesizing the growing natural histories of the natural sciences with human history into a seamless whole. And in placing human history in the context of natural history, we can extend our research from the past into the future, insofar as the predictive power of the sciences extends. This makes big history a new science that embraces the whole of time.

But insofar as any of these big picture research programs I have noted above are integral with the sciences, will their growth follow the pattern of the growth of the sciences? Will these research programs and existing antecedents within science be so fused that the fate of one is also the fate of the other? And what is the fate of science that is to be shared by novel disciplines?

One could speculate that the ultimate story of science will be to take the form of disciplines fissioning into ever narrower specializations, each confined within its disciplinary silo, terminating in isolated and virtually inapplicable knowledge. Alternatively, an age of fissioning could be followed by an age of gathering specializations together again into one grand inter-disciplinary body of knowledge, so that science rediscovers the unity that it knew before fragmenting into specialization. This is the hope mentioned above of a final form of science, which strikes me as being as sterile as its dialectical complement of isolated and inapplicable specialization.

Science, however, need not necessarily terminate in either of these antithetical scenarios. Science may also continue to add to and to complexify its reticulate structures, mediating specialization and comprehensivity, embodying both narrowly specialized knowledge and broad overviews that reveal the deep connections between specialized bodies of knowledge. This is now the future that I expect of science, with new specializations continuing to appear, at the same time as new interdisciplinary efforts appear, and the whole of science being characterized by the interweaving of overviews and specialization, with no final form, but an ongoing process of inquiry from ever new perspectives.

0 notes

Photo

AUTONOMOUS BY ANNALEE NEWITZ

BY: NIALL HARRISON ISSUE: 11 DECEMBER 2017

1.

Medicine, medical research, and healthcare systems have always felt to me a little under-explored by SF. Every so often there's a small-press anthology, or some think tank-y futurism—such as this year's Writing the Future competition, organised by Kaleidoscope Health & Care—and on screen no starship is complete without its sickbay and doctor. But when it comes to more substantial SF, and in particular novels, the pickings seem slim. The two recent-ish examples that come to mind are Project Itoh's Harmony (2008, trans. Alexander O. Smith 2010), and Juli Zeh's The Method (2009, trans. Sally-Ann Spencer 2012): both are classically dystopian narratives that dramatise the totalitarian potential of excessive care. Beyond that, you have to look for more generally biotech-oriented stories that incorporate elements of healthcare politics, such as Stephanie Saulter's (r)egeneration series (2013-2015), or mainstream-published work that shades into the speculative, such as Jillian Weise's The Colony (2010) or Hanya Yanagihara's The People in the Trees (2013). The gap seems especially glaring when it comes to American genre SF, given the political prominence and immanently-dystopian quality of the American healthcare system, and its knock-on effects for global healthcare: to paraphrase William Gibson, the drugs are here, they're just not evenly distributed.

So Annalee Newitz's first novel, Autonomous, is welcome for building its narrative around the practicalities and morality of access to effective drugs, even if some of its choices are a little more confusing than you might hope. But we'll come to that. Setup first: towards the end of the present century, the global Collapse that looms in most of today's near futures leads to a realignment of the international order, away from nation-states and towards “economic coalitions”—of which the big players seem to be the Free Trade Zone that covers most of North America, the Asian Union, the African Federation, and the Eurozone—that represent near-total capitalist capture of governmental and public services. As a result, patent terms for new medicines have been extended to longer than a normal human lifespan; regulatory oversight of the clinical development process has been weakened nearly out of existence; drugs that enhance health and cognition are common and required for many jobs; and the pay-for-treatment US insurance model appears to have been extended to basically the entire world, leading to cascading generational inequality:

Only people with money could benefit from new medicine. Therefore, only the haves could remain physically healthy, while the have-nots couldn’t keep their minds sharp enough to work the good jobs, and didn’t generally live beyond a hundred. Plus, the cycle was passed down unfairly through families. The people who couldn’t afford patented meds were likely to have sickly, short-lived children who became indentured and never got out. (p. 55)

Enter Jack Chen, patent pirate. From a family of farmers, she moved into synthetic biology research, and then into open medicine activism, first as part of a group known as The Bilious Pills, then later and for decades as a solo artist. In July of 2144, we find her in the middle of the Arctic Ocean, charging up the batteries of her submarine and worrying over news stories about a bad batch of black-market pharma that might be her fault. In an attempt to raise funds to subsidise her “real work” making medically urgent antiviral and gene therapies freely available, Jack reverse-engineered and sold Zacuity, the hot new “productivity pill” made by Zaxy, which was “didn't just boost your concentration [but] made you enjoy work” (p. 14). Now there are stories in her feed about people with obsessive task addiction, starting with a student whose “brain showed a perfect addiction pattern [...] like she'd been addicted to homework for years” (p. 11). Before too long, Jack is on the run, attempting to find a cure for the people she's inadvertently hurt, while being pursued (in alternating chapters) by agents of the International Property Coalition.

Newitz's future, while perhaps not quite matching the likes of Lauren Beukes or Ian McDonald for sentence-level stylistic verve, is rich, varied, and consistently interesting; it's fun to roam from the Arctic to Casablanca to Vegas and on. But every now and then something doesn't quite ring true. The mildest of my eyebrow-raises were down to inconsistencies or ambiguities in terminology. If you tell me a drug is in “beta” (p. 29), I will assume a move-fast-and-break-things culture has replaced more rigorous medical research, unless and until you later start talking about phase 1 clinical trials: those two linguistic paradigms don't fit neatly together. If you refer to “cloned Zacuity” (p. 13), I will assume it is produced by a process in which cloning could plausibly be relevant; so it's probably a biologic, perhaps a cell therapy of some kind; but if you then talk about “isolat[ing] each part of the drug” and “narrow[ing] the questionable parts down to four molecules” (pp. 28-9) I will get thoroughly confused, since not only does that not sound like a cell therapy or biologic, it doesn't even sound like Zacuity is a single drug, but rather a combination of small-molecule treatments.

Above this, however, sit some practical and conceptual concerns. I can accept that the novel's characters believe that subversion of intellectual property law is the most practical solution to their crisis because they are living under total capitalism; but it is odd that nobody even laments the impossibility of a system that would centralise and pool healthcare costs. Socialism seems to have been thoroughly erased in the present, in memory, and in possibility. And I can accept that “Zaxy didn't make data from their clinical trials available”, but the corollary, “so there was no way to find out about possible side effects” (p. 14) seems a little dubious in what is evidently still a networked world easily capable of crowdsourcing that information. Then there's the underlying business model itself. It seems that the have-nots massively outnumber the haves, and while pharmaceutical companies are not perfectly rational economic agents, and have been known to push the limits of appropriate pricing for access to treatment, at a certain point charging x to a market of y patients becomes less profitable than charging a fraction of x to a multiple of y. Everything we learn about the world of Autonomous suggests that Zaxy and its competitors deliberately keep themselves on the wrong side of that equation. It's only Jack and her friends attempting to fill the market hole, and it's not clear why.

Why does such pedantry matter? Perhaps it doesn't. But Zacuity is presented to us as symptomatic of a system, a synecdoche for lost autonomy, the reduction of human lives to biological machinery. It's everything Jack has dedicated her life to fighting against. And for that fight to really matter, the symptom and the system need to feel crushingly inescapable; and they don't always.

2.

Or is there another way in? Autonomous explores its core theme on more than one front. It is a novel about seeking freedom in an owned world, and although the owners in the background don't always quite feel solid, their property is memorably thorny. Two pairings stand out in particular. Travelling with Jack is Threezed (3-Z, two syllables), a young indentured man she inadvertently rescues from his owner; pursuing them are two IPC agents, an enfranchised man named Eliasz, and an indentured artificial intelligence, Paladin.

Indenture is, for the avoidance of doubt, slavery, but a version grown from the worst of contemporary employment practices and a perversion of the concept of equality. It took root, we are told, in the mid-twenty-first century, with the arrival of the first true artificial intelligences: “companies could offset the cost of building robots by retaining ownership for up to ten years” (p. 224). (The parallel to non-sentient innovations such as pharmaceuticals is hard to miss.)

But when bots were granted human rights, that didn't come with their immediate freedom; instead, a new human right was enshrined, namely the “right” of indenture. “After all, if human-equivalent beings could be indentured, why not humans themselves?” (p. 224). This global endorsement of slavery as the ultimate choice of a good capitalist subject means that in 2144 it has expanded from what we know and become an order of magnitude more extensive than at any previous point human history. Its supposed limits are fig-leaves: even if birth-indenture of humans remains technically outlawed in most of the economic coalitions, many turn a blind eye, and in any case, child indenture is fine. Such was the fate of Threezed, as Jack sees it:

Families with nothing would sometimes sell their toddlers to indenture schools, where managers trained them to be submissive just like they were programming a bot. At least bots could earn their way out of ownership after a while, be upgraded, and go fully autonomous. Humans might earn their way out, but there was no autonomy key that could undo a childhood like that. (p. 31)

The other characters—and for most of the novel Threezed is seen only through the eyes of others—know this story intellectually, but for various reasons have a hard time internalising what it means. After Jack rescues him, Threezed, “his eyes wide with feigned innocence” (p. 52), offers to “repay” her; Jack wonders whether he is “trying to manipulate her” or whether “his indenture had trained him in this specific form of gratitude” (p. 52). She asks him if he is sure. “He bowed his head in an ambiguous gesture of obedience and consent” (p. 53): a haunting reaction. Their 'relationship' continues for some time, and Jack—an ostensibly pragmatic woman, for whom romance is “like any other biological process [...] the product of chemical and electrical signaling in her brain” (p. 57)—starts to convince herself Threezed's compliance is perhaps more than his programming. “She leaned over to kiss Threezed hard on the mouth. His reaction was not artful. It felt sloppy and real” (p. 88). That “real” lands hard, I think, imbued with a desperate desire for a simple story to be true, for Jack not to be exploiting vulnerability. But of course the power imbalance has distorted Jack's perceptions, as power imbalances inevitably will. Late in the novel we discover that Threezed keeps a blog of his experiences. It is a “prickly, grotesquely truthful story” (p. 243), and his take on Jack is simply that, “Every master loves to fuck a slave” (p. 253). What he doesn't add is the horror we have already seen: a master who wants to believe the slave loves to fuck them back.

While all this is happening, Paladin and Eliasz are becoming similarly entangled, but this time it's the master's view that is withheld. Paladin—newly activated and thus something of an innocent, albeit one equipped with alarmingly lethal military hardware, and with appropriate software installed to ensure an uncomplaining 20 years of indentured service—has an unexpectedly intimate moment with Eliasz fairly early on in the novel:

The bot stood at full height, and Eliasz rested his hands on the guns that jutted from Paladin's chest. Eliasz' right hand began to move slowly, getting to know the whole barrel by feel.

[...]

Shoot the entire roof off that house. Eliasz' lips were pressed into Paladin's carapace, moving slightly as he gave the vague order.

[...]

Paladin categorized the physiological changes in Eliasz' body and reloaded his guns. The bot decided to continue his human social communication test by not communicating. It didn't make sense to remind Eliasz that every single movement of his body, every rush of blood or spark of electricity, was completely transparent to Paladin. He would allow Eliasz to believe that he sensed nothing. (pp. 75-76)

This is entertaining—and a later scene in which Paladin allocates 20% of his processing power to run internet searches for confusing sexual terms while reserving the remaining 80% to concentrate on blowing shit up is outright funny—but it's also tragic. Every one of Paladin's actions is oriented towards meeting Eliasz' needs, even “his” acceptance of a particular pronoun. Bots, we are told more than once, do not have a sense of gender, and as a result it takes Paladin a while to understand how profoundly gender shapes the world for humans. When it becomes clear that Eliasz would be more comfortable with their relationship if he could think of Paladin as a woman, Paladin accommodates by accepting “she” instead of “he”, even recognising the potential impact of the change, even knowing that the choice may not be free: “Bug would no doubt say that there are no choices in slavery, nor true love in a mind running apps like gdoggie and masterluv. But they were all that Paladin had” (p. 236). More completely programmed than Threezed, Paladin's chosen truth shies away from the grotesque—even after she achieves autonomy.

Fortunately for Paladin, Eliasz treats her better than Jack treats Threezed—he asks permission, for one thing—and his feelings, when we are eventually given access to them, do appear to be—that word again—real. In contrast to Jack's mechanistic view of love, for Eliasz it is an unexamined but powerfully felt emotion, and when at a moment of crisis he has to choose between achieving a goal and saving Paladin, he thinks: “He had a choice. Or maybe he didn't” (p. 285). And like that we are reminded that the novel's logic for “human indenture” is particularly malevolent because it extrapolates from an underlying truth: that even when nominally free citizens, humans are never perfectly autonomous and that that is in fact a good and necessary fact; that in a thousand different interactions we give up some of our freedom, for the sake of each other, for the sake of society. Is that grounds for a faint flicker of hope? In Newitz's dystopia it may be supremely difficult to define when and where “real” occurs, but if at least some voluntary abstentions of autonomy remain possible, some of the time, then neither humans nor bots have been reduced to perfect commodities yet. So the fight does still matter. I think that, in the end, is what I choose to take from this unsettling, uneven novel.

@booksandghosts This reviewer is brilliant and the emphasis above (I bold/italicked the paragraph which matters to me) explains eloquently what I called “misgivings” while I read this book. I thought you would like to know. The review is -of course- somewhat spoilery, though not overly.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Isolat Pattern - Entwined From the album ‘post-romantic’, released by Kvitnu

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

AI and Marketing: The New Power Couple

A conversational piece with Martha Mathers, Marketing Practice Leader at Gartner (by Editor-in-Chief Chitra Iyer)

What is the scope of impact of AI on Marketing? How are marketers approaching the opportunity AI offers for improved productivity and effectiveness and how can CMOs best measure the outcomes? We had a conversation with Martha Mathers, Marketing Practice Leader at Gartner, to better understand where AI-powered Marketing is headed.

First, there was automation Now there is AI.

AI is taking over the world. If not in the dystopian sense, at least in a very practical and almost invisible way, it is impacting every industry, from recruiting to developing nuclear submarines.

It’s obvious that AI is impacting some of the more visible and isolatable elements of marketing such as content marketing or customer service. But when it comes to leveraging AI across the overall marketing strategy, in order to drive the overall seamless CX, perhaps it is difficult for CMOs to find a starting point. The good news is that if you consider yourself a data-driven marketer, then half the battle is won. AI works best in a data-driven environment which lends itself to pattern-based analysis, personalization at scale, improved efficiency and the automation of routine tasks.

Martha Mathers, Marketing Practice Leader at Gartner, suggests that a good starting point for a CMO thinking about investing in AI is to look into:

1. Data: While marketers don’t need perfectly integrated data for effective use of AI, they must identify what data is required given their objective, establish the structure of that data and integrate the necessary components, given the marketing tactic.

2. Skills: Often, marketers will invest in a new capability without evaluating their team’s readiness to use, iterate and learn from the tool.

3. Customer Permission: While customers are increasingly open to engaging with artificial intelligence for many use cases and industries, it’s important to explore your specific use case and desired segment (see chart below):

I ask Martha about her experience of marketers who had built AI successfully into core sales and marketing, and she offers the example of a subset of B2B companies that completely revamped processes related to sales enablement (prompting sellers with new options based on online tools or NLP during a sales call or reconfiguring seller portals based on their data entry), customer service and customer intelligence. In addition, leveraging AI for testing platforms can provide real-time feedback; and digital platforms can adapt through machine learning to enrich the customer experience. “We also see many members re-envisioning how they plan for digital experience innovation, given the wealth of tools and capabilities available”, she says. Other examples Martha shares of creative AI-driven marketing initiatives include

A brand in the wine and spirits space that uses chatbots to help educate millennial customers and simplify their decision-making process through conversational / chat tools.

Olay and L’Oreal both use photos to provide advice and interactive experiences around new cosmetics.

Whole Foods has innovated beyond sharing recipes to using ingredients to provide shopping suggestions that increase the size of purchase.

Undoubtedly, all marketing leaders are open to the idea of leveraging AI meaningfully, but not everyone has got it right, leading to a situation where proving ROI becomes harder. What are the common mistakes CMOs tend to make when it comes to driving optimal outcomes from AI investments? Martha cites two:

First, the ‘shiny object syndrome’: “We think of this as the exploration of new technologies or approaches without a clear connection to a business need or customer problem to solve. In the burgeoning MarTech space, where vendors make lots of promises around business outcomes, this happens much more than you think”.

Second, not having clarity on the outcomes of the AI investment. “Some companies bite off more than they can chew at the selection phase, scoping a huge project for AI, given the size of the investment, before learning where it might add value and how customers will engage with it”.

Speaking of outcomes though, what are the key metrics to measure ROI on an AI investment?

Considering that AI delivers on so many fronts – from productivity to better strategy development to more efficient and effective execution and finally, of course, better sales outcomes, the results cannot be measured for just one AI-powered campaign. AI gets smarter over time. All the more important then, that that CMOs look at AI as an essential extension to all marketing components - building it into everything from data collection and storage to the application of data – for it to deliver optimal ROI. Martha has seen companies improve their content production, web design, predictive customer service, segmentation, and sales forecasting – among other applications – through AI-powered tools. “The smartest CMOs tend to approach AI with a lens of how it can advance business outcomes. From an external perspective, it might improve customer communication resonance through personalization, remove barriers to purchase with technology or increase product/service usage” says Martha.

Unlike other investments, any realistic measure of AI outcomes needs the participation of all leadership - CFO, CTO/CIO, CMO – as CX and the ultimate business objective of profitability is everybody’s mandate. Finally, what is important in the measurement of AI success is to track progress over time. As with any new technology investment, early adopters that stay with it and keep evolving it (instead of abandoning it after a few failed attempts) tend to start showing exponentially successful results over time.

When investing in an AI solution, being aware of how it will grow and evolve over time - with the company, its offerings, and its customers – is crucial. How intelligent it really is, and how it can demonstrate its ability to evolve in response to a stimulus is what sets AI apart and worth investing in, versus only evaluating what it can deliver today (now).

As AI gets smarter and more mainstream, it also becomes more accessible to everyone- from enterprises to SMBs. In fact, Martha says, Gartner has seen significant success with AI in mid-size firms that aren’t too weighed down by data silos and legacy systems. But even with AI – as with any technology - it is ultimately the people using it and working with it that will make the difference. I asked Martha if marketing teams need any additional skilling to be able to thrive in an environment driven by AI? “While there’s certainly technical understanding, there’s an underappreciated set of skills that we’ve observed as well. Strengths such as creativity – the ability to imagine the art of the possible – and collaboration come to the forefront. Companies such as L’Oreal have invested in boosting the digital savvy of their entire teams – not to make everyone digital experts, but to enable better collaboration of classically trained marketers with the digital experts”.

The future of AI in marketing applications looks bright but management and leadership need to build new models to measure the outcomes from AI investment, without taking away from asking the right questions and ensuring the solution shows progress over time. “In 2018, we will see marketing leaders move from “shiny object” to “critical capability” with AI, using it to boost productivity, improve the customer buying experience and deepen their customer understanding” That is Martha’s prediction for AI. I wonder what my AI-enabled oracle would say to that.

More on Martha Mathers:

Martha Mathers is a Marketing Practice Leader at Gartner, where she manages the global research team’s ongoing efforts to surface progressive insights, best practices, and implementation guidance for CMOs and their teams.

This article was first appeared on MarTech Advisor

0 notes

Text

Expert: One of my less popular beliefs (and that’s saying something) is that any form of sexuality is inherently objectifying. As with all language being violence and all poetry dishonest, that’s not the end of the story, obviously, and certainly not an injunction to never engage with it. My basic argument is that sexual desire is ultimately a very simple lizard-brain thing and while you can hook it up to to complex circuits, there’s a limit to the complexity of the triggers, or at least diminishing sustainability to complex triggers. The triggers can be ‘relatively’ complex, but they have to be ossified enough — have to have permanent enough associations or connections — to actually serve as triggers. You may get off to signs of someone else desiring you, but that’s not seeing them as an ends in themselves. You may get off to signs of someone’s else’s intelligence and creativity, but that’s not seeing them as an ends in themselves. Identifiable tropes or trappings of intelligence or creativity are themselves object-functioning. The causal origin such sexual triggers might reveal desires or motivations or social allegiances that we might say reflect more valorous alignments than others, but any codified trigger is nonetheless objectifying. When we view someone as an “artist” say we objectify them with such simplified pictures in broadly the same way that viewing someone as a body is objectifying, we view them as a thing rather than as an agent. Relating to someone in terms of simplified roles or characteristics is in a similar objectifying vein as relating to them in terms of their body, because such relating turns away from dwelling on the fullness of their existence in all its unknowable subjective complexity. It seems safe to say from everything we know about biology and neuroscience that in order for any stimuli to trigger sexual desire it has be sufficiently simple. It gets harder and harder to construct a triggering circuit as the complexity of the trigger rises. A sufficiently complex sexuality may no longer count as a “sexuality” and it seems unlikely to be able to even function as one. Indeed almost all sexual triggers are incredibly simple. Every remotely common flavor of kink is about severe simplifications of our environments or narratives or relations. In actual life maintaining power or being oppressed can be incredibly complicated and rife with anxiety. But kink uniformly attacks such anxieties, it removes complexity. We see the same with common modes of relating that don’t conceive of themselves as “kink”, people frequently ground their sexual attraction for others in their capacity to signify an idea or serve a role or generally perform as some thing. Even the most vaunted of complex queer practices when they get closer to sexual desire suddenly get very simplistic indeed. Going off of what people say to me in private there’s a huge amount of anxiety and unspoken tension in the present radical queer milieu around being incapable of stating actual desires or triggers for fear of being seen as too simplistic, too unintelligent, too undeveloped. So there’s a kind of tension between radical queer social practice, which delights in exponential complexity and compounding conceptual processes, and the actual sexual desires of said people. The desires tend to be far more simplistic, albeit sometimes cloaked in a bunch of performative academic complexity. Indeed what seems most common in queer practice is the holding of non-standard or unusual desires that are simplistic in function but are necessarily complex in their explanation (because of their non-standardness). A very simple system can require an incredibly complicated amount of explanation to be comprehensible within a paradigm not built to refer to it. I think we’re deluding ourselves into thinking sex can be a site of rich intellectual connection; sex is anti-intellectual. But that’s actually the most useful thing about it, it kills thought. Sex kills anxiety, strips away the tangled and sometimes counterproductive webs we’ve woven, it reduces us from a realm of rich internal subjectivity to something closer to an object. Sexual desire is — in an ethical lens — a lot like getting drunk, it strips away our agency and renders us less capable of fully recognizing or enshrining the agency of others. All we are left with is very simplistic checkboxes of consent, is the other person displaying enthusiasm, etc. We are inherently left with simplistic codes. It’s important to note that while we seek to expand agency, moments of lesser agency or shallower connection are not uniformly objectionable. After all we go literally unconscious for large portions of every day, reducing ourselves to almost as object-like an existence as is possible. We do this because our brains have limits, because as processes of cognition we grow overly complex, we need to strip ourselves down, to restructure and refurbish. It is not clear that such refactorization would not be inherent to any thinking thing, any process of cognition in this universe. There’s an expansive tendency towards building expanding networks of possibility and likewise a contracting tendency towards radical slicing away of those networks to restructure towards more stable or more broadly useful roots. Sex (both desire and mechanism) is a particularly hamfisted means of pruning overgrown complexity, and its internal logic frequently pulls us in the direction of intensely problematic simplicities. But as with alcohol and sleep, sometimes a clunky and intensely dangerous tool is all we humans have to do a necessary job. I know that the juxtaposition of sex with love risks derision for conjuring a Christian mindset, but it’s not like for two millennia millions of folks knew absolutely nothing or were influenced by no substantive insights. And of course such a split is commonly arrived at across many cultures. I think the dichotomy is the most useful/illuminating conceptual schema possible in this realm. Love is grasping the fullness of someone else’s reality, the realness of their full being. Love is a level of engagement that denies simplification, that increases the scale of an individual’s presence in your perceptual universe, fleshing them in with so much detail and motion it becomes both intractable and unboxable. Love operates in the hyper-complex and rich realm of agency and subjectivity. Sex operates in the dangerously simple realm of consent and objectification. You can have loving sex with a partner, in the sense that there’s a smooth arc of increased drunkenness and mutual objectification together (as opposed to a discretized jump to objectification via say the abruptness of adopted kinkplay), but sexual desire is never predicated on something as infinitely complex as love. It’s predicated on specific isolatable, simplistic triggers. Even when those simplistic (objectifying) triggers are things more complex than visual pattern recognition of nice bits, like “I feel safe with this person” or “I desire their happiness”. Such simplistic narratives are obviously dangerous, but they can also be grounding, if only to provide a vantage-point for new attempts at constructing complexity. Sex may even augment and facilitate loving relationships — in the sense that it provides a strong means to mutually shed off the bloated complexities that continuously emerge between two deeply integrated systems. A jump down to a more simplistic base from which to then go back and evaluate the tangles without being caught up in them. Sex can also function as a kind of game theoretic reset where two parties recognize that their tangled maps of each other have become intractable in a way causing problems. Both parties know their anxieties about the other are likely incorrect, but they’re too embedded in a paranoia to state things clearly and without creating further tangles, sex can be seen as a way to ensure mutual defection. Sex offers a way to reduce one another to an “original position” as it were, from which both can collaboratively chart the tangles from a position of relative objectivity. In a flip, sexuality can also have valorous effects by breaking symmetries. Just as self-constrained rationality can be an incredibly useful tactic, it is often desirable to introduce some clumping into an otherwise perfectly connected network to create a kind of topological diversity that facilitates evolution of ideas & cultures. Too complex of affinities and attractions can rapidly make choice between all other agents computationally intractable, thus introducing simple (ie objectifying) attractions can serve to break the ice, as it were, of an otherwise locked up social network. Without something arbitrary like sexual attraction we might find ourselves incapable of selecting among billions of irreducibly complex fountains of agency, much less being pulled into closer orbits of more intense and personal engagement where love can flourish. Of course music tastes and even the automated assignment of numbers of affinity could likewise break such symmetries, but these too would be objectifying processes, even when ultimately serving grander aims. Conversely, assigning simplistic attractions below an agent’s conscious control can also work against clumping, when such clumping diverges far from a perfectly connected network (creating epistemic closures and general constraints on freedom). Sexual desire is often a violently objectifying process, in the sense that any over-simplification that discards detail is always violent. Science can — when successful — entirely compress detail into a more simple description, finding the hidden symmetries and redundancies, without slicing anything away. But the fullness of another mind can never be accurately compressed. We defy simplification. At the same time simplification is necessary and critical for any sort of life. We require simplification. To get anywhere we need to be able to wipe the slate clean, to cut through otherwise tangled knots. Sexuality provides a machete. It’s almost always used to hurt people — its simplifications do violence both upon others and upon our own thoughts and agency — but sometimes a machete can be very useful in hacking yourself free. Without tools like machetes our explorations would be more timid and our missteps more overwhelming. It is precisely tools of simplification that enable searching minds to develop continually blossoming complexity without wandering into deadends and choking themselves out. Sometimes you have to trim to keep growing. Sometimes crude simplification, the slicing away agency and subjectivity, is necessary and useful to serve their expansion. Sometimes you have to take a shot of whiskey to clear your confused thoughts and better ruminate. Sexual desire and attraction crudely objectifies. It is most illustrative to keep it conceptually distinct from infatuation — a kind of relishing of open possibility — and love — a kind of inescapable and incompressible tangibility. All sexuality is an orientation of epistemic violence that inaccurately reduces ourselves and others. A world entirely colonized and subsumed by sexual desire would be a world of objects. And it goes without saying that our present world is permeated and ordered by sexual attraction in grotesque fractals of thoughtless violence. But all this does not suffice to prove that sexual attraction cannot be instrumentalized in the service of agency. It merely proves that sex is a dangerous mechanism that always at least partially mutilates what it touches. Yet we must remember that some of the best and most useful tools frequently live double-lives as weapons of mass destruction. http://clubof.info/

0 notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Clinical Ambience by Isolat Pattern

1 note

·

View note

Video

vimeo

ISOLAT PATTERN "BLK.HSE" Music by Benjamin Harris. Video by [AudioReact.Lab] - audioreact-lab.blogspot.it Track BLK.HSE taken from Kvitnu release "Clinical Ambience" by Isolat Pattern.

kvitnu.com/releases/kvitnu37/

2 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Preview upcoming Kvitnu release

2 notes

·

View notes