#Oregon process servers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

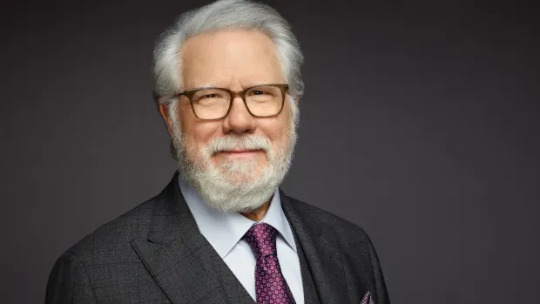

The Surprising Reason John Larroquette Took His Career-Defining Role on 'Night Court'

The comedy ninja reveals all this week's 'Parade' cover story.

MARA REINSTEIN

UPDATED:JAN 19, 2023

Get in a car and drive about 30 miles north of Portland, Oregon, into southwest Washington. That’s where you’ll find actor John Larroquette.

He and his wife, Elizabeth, have lived on a piece of rural property for about five years. He collects books and likes to narrate plays in his home recording studio. Sometimes the couple head into the city to try new restaurants and go to the theater and concerts. “It’s really beautiful,” he says. “And at my age, it’s time to slow down and be out somewhere.”

In fact, Larroquette is so fond of his far-from-Hollywood lifestyle that not too long ago, he considered himself retired from the business with a fulfilling career and a room full of trophies to show for it. Never did he think he’d return to grueling TV work, let alone reprise the very role that made him a household name.

Guess what happened next?

Yup, Larroquette, 75, is suiting back up as wise-cracking, endearingly smarmy lawyer Dan Fielding in a new version of the irreverent sitcom Night Court (premiering Jan. 17 on NBC). Set decades after the 1984-92 original, it still chronicles the colorful cast of characters passing through the New York City after-hours courtroom. But now, the Honorable Abby Stone (Melissa Rauch), the daughter of Judge Harry T. Stone (Harry Anderson), bangs the gavel.

Fielding starts the series as a process server, though not for long. “As an actor, I thought it would be an interesting idea to revisit a character 35 years later in his life and see what happened to him,” Larroquette says. “I can’t do the physical comedy and jump over chairs anymore, so my conversations with the producers were about how to find the funny.”

Call it the latest unexpected turn for a seasoned star who began his professional journey as a DJ for “underground” radio in the 1960s, moved from his native New Orleans to Los Angeles to jumpstart his career, once took a gig in exchange for marijuana, played a Klingon in the third Star Trek movie and completed rehab to kick his heavy drinking—all before his very first audition for Night Court in 1983. After the sitcom’s last episode, he won his fifth Emmy (for the drama The Practice) and a 2011 Tony for the Broadway revival of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. He and Elizabeth, wed for 47 years, have three grown children.

“I honestly wish I had a tape recorder going at all times because he’s led such an interesting life and has such wonderful stories,” marvels Rauch, his co-star and a Night Court executive producer. “He’s super-quick, funny and definitely tells it like it is.”

Exhibit A? His interview with Parade, in which he discusses life and death, and everything in between.

Did you sign on to the series right away or was it a tough sell?

When Melissa [Rauch] presented the idea to me, I immediately said, “No thank you.” I didn’t like the idea of being compared to my 35-year-old, younger self. These conversations went on for a year. Then, one day, she told me that she wanted to be on-camera as well, so I decided to try and do it. We ended up pitching the show together, and it got picked up. You know, in New Orleans, there’s a French word called “lagniappe,” which means “a little bonus.” That’s what I consider myself. She’s the heart of the show.

Sadly, a few of your co-stars—including Harry Anderson and Markie Post—have died in recent years. What was it like being on the set without them?

Very emotional. Harry passed away in 2018, but it’s still a tender spot in my heart because he and I were together for a long time even outside of work. Markie and I were very close, and we had exchanged a few emails about the show before she died [in 2021]. She was a big cheerleader for it. And Charlie [Robinson, who played the clerk “Mac”] died when we were shooting the pilot last year. I saw him a lot because we both love the theater. Being on the set—I don’t say this glibly—but it was like seeing dead people. I’d always remember how I had this bizarre and completely sincere family for nine years.

Going back to the 1980s, why did you originally take the Dan Fielding role?

It was a paycheck. This was 1983, and I was still a journeyman actor going from job to job. I was a regular on a series in the ‘70s [Baa Baa Black Sheep], but then I took a few years off to do some extremely heavy drinking. After I got sober and realized I wasn’t going to die, I thought, “What am I going to do?” I had been in a pretty big [1981] movie called Stripes with Bill Murray. I read for Ted Danson’s role in Cheers.

Wait, how far did you get in the Sam Malone casting process?

Oh, I just walked in and did a cold reading along with every other 32-year-old actor at the time. But then I auditioned for the judge in Night Court. The producers asked me to read for this other role of Dan Fielding and I said, “Sure.” Even if I hated the role, I would have taken it because I needed to make money to help pay the rent and support my family and be a responsible member of society. It was luck that I really liked it. Then I got lucky again when NBC picked up the show as a mid-season replacement.

During the height of the show’s popularity, you earned four consecutive Emmys for your performance. That must have felt beyond validating.

Obviously, being acknowledged by your contemporaries was an incredible honor. I don’t say that blithely. It was a remarkable, remarkable feeling. And I was up against some formidable talent—mainly all those guys from Cheers.

Why do you think the character was and is so appealing?

I think because he allowed the audience to know that he wasn’t a bad guy. He was more like a feckless buffoon. He also really wanted to be loved. As a matter of fact, in our pitch, we screened an old scene of Fielding in a hospital bed telling Harry, “I don’t have a life; I have a lifestyle. Nobody has ever said, ‘I love you.’” So when we find Fielding again, he’s loved and lost. And Harry’s daughter forces him out of his cave. It’s a real full-circle moment.

Let’s go back to your own start. Did you have any music skills coming out of New Orleans?

Well, I started playing clarinet in third grade, then I moved to the saxophone in the 1960s. But I euphemistically say that I could talk better than I could blow. So, I took that sax out of my mouth and became a DJ and started using my voice as much as I could. I’ve always loved the analog aspect of audio. I still have some reel-to-reel tape recordings and old microphones.

Is that how you ended up narrating the opening prologue for [the 1974 horror classic] The Texas Chainsaw Massacre?

No, no, that wasn’t through any kind of past work. In the summer of ‘69, I was working as a bartender at a small Colorado resort in a little town called Grand Lake because I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life. [Director] Tobe Hooper happened to be in town and we became friendly. Flash forward four years, and I found myself in L.A. collecting unemployment checks and trying to decide if I wanted to be an actor. Tobe heard I was in town and asked for an hour of my time to narrate something for this movie he just did. I said, “Fine!” It was a favor.

Per the Internet, he gave you a joint in lieu of payment. True?

Totally true. He gave me some marijuana or a matchbox or whatever you called it in those days. I walked out of the studio and patted him on his back side and said, “Good luck to you!” Now, I have also narrated the consequential films and did get paid. You do something for free in the 1970s and get a little money in the ‘90s. I’m not a big horror movie fan, so I’ve never seen it. But it’s certainly the one credit that’s stuck strongly to my resume.

But you’ve appeared on the big screen plenty of times. Did you have movie-star aspirations following all your TV success?

The movies I’ve done are mostly forgettable. Blind Date [from 1987] is an exception, but that’s because of Bruce Willis and Kim Basinger. And Blake Edwards directed it. It was funny. But my face is not made for a really big screen. It’s a broad, clown-like face. It’s good for a TV two-shot. And you ride the horse in the direction that it’s going and television was always right there and offering me stuff, so I kept doing that.

You also performed in a musical for the first time in How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying in 2010. How was that change of pace?

I was hesitant to do it because I had never sung and danced on stage. I was convinced I was going to be fired in the first two or three weeks. I’d keep going in my head, “five, six, seven, eight!” just trying to get the steps down. But I loved the lifestyle of being a stage actor in New York. I loved working with Daniel Radcliffe, and we became fast friends. It got to a point where I couldn’t wait to get to the theater and try it again that night. If you’re given the opportunity to do something that may be a stretch, I think it’s important to try and see if you can pull it off.

Can you talk a bit about your personal life? You seem a little reclusive.

Reclusive isn’t accurate, but I’m definitely an introvert. Elizabeth and I met doing the play Enter Laughing and got married in 1975. She puts up with me, and you can’t ask for much more than that. Our kids are grown. My daughter Lisa is a graphic designer and my son Jonathan has had a podcast for the past 17 years called Uhh Yeah Dude. And my youngest son, Ben, is a musician who graduated from the Berklee School of Music. He actually composed the new theme music for Night Court. They’re all lovely, and I love them dearly.

That’s quite a professional and personal success story, no?

You know, considering where I’m from and the kind of culture I grew up in, yes. I’ve been very successful in my chosen field. And I’m grateful for having done that because there were times when I thought I would not live, much less have a career. It’s nothing to be taken for granted. But I’m very old now. Three quarters of a century. I’m sort of playing with house money from now on, regardless of what happens.

Sorry, but 75 isn’t very old!

Yes, it’s old. It’s old. Please. It’s old. There are certainly people who live longer, but I can go down the list of wonderful friends and coworkers who are now deceased. One being Kirstie Alley, my costar in [the 1990 comedy] Madhouse, who was younger than I am. She was a lovely person, and so funny. There are only a few more exits on the freeway and you’ve got to choose one. But I’m not afraid of the hereafter and I don’t bemoan it. It’s been an interesting ride, and all rides eventually end.

Do you have any sort of words to live by?

As corny as it sounds, take things one day at a time. You know, I learned when I stopped drinking at age 32 that all you have is right now. Use the present in your life as much as you can.

Source: https://parade.com/celebrities/john-larroquette-night-court-cover-story

-----

My thoughts (please feel free to ignore):

I'm sure someone in the fandom has already posted this interview John did last year with Parade magazine when the new Night Court premiered. But I can say that it's new to me, so I'm sharing it in case it's new to someone else too.

I apologize for the highlighted purple sections above. That's just me marking the parts of the interview that resonated with me the most.

I don't know about anyone else, but some parts of his answers to the questions made me feel kind of sad. Partially because he's clearly experiencing grief at the loss of his friends. And partially because John himself may not be with us for much longer (although I hope I'm wrong and he beats Betty White to 100).

But I was talking to my mother about some of his answers, and she said that as someone who has reached an age milestone herself, she understands his perspective. And I guess I do too.

It's important to remember that in any other profession, John would likely be retired by now. So we should really be grateful for any roles he takes or public appearances he makes, and hope that his days ahead are filled with the calm, joy and laughter that he so rightly deserves.

#john larroquette#new night court#night court#fandom#interview#parade magazine#night court 2023#bittersweet

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Life is what you make it

Start your journey today

Investing in American Innovation

Tim Cook of Apple tech company is investing in U.S manufacturing, innovation. This commitment of 500 billion is expected to provide tech jobs, focusing on research and development, silicon engineering, artificial intelligence and machine learning.

It involves building an advanced AI Server manufacturing factory near Houston, this will be possible through the companies Advanced Manufacturing Fund while establishing an Apple manufacturing Academy in Detroit.

This expansion will happen in facilities in numerous states including Michigan, Texas, California, Arizona, Nevada, Iowa, Oregon, North Carolina and Washington.

Tim Cook after meeting with President Trump, pledges to be committed to the future of American Innovation.

Investing in American innovation is crucial for the future advancement and success of our economy. Innovation plays a vital role in driving economic growth, creating jobs, and increasing the United States' global competitiveness. By investing in American innovation, we can foster creativity, drive technological advancements, and spur new industries and opportunities for growth. This essay will discuss the importance of investing in American innovation and the benefits it can bring to the country.

One of the primary reasons why investing in American innovation is essential is because it can lead to the development of new technologies and products that can improve our quality of life. By funding research and development in key areas such as healthcare, renewable energy, and information technology, we can discover new solutions to pressing problems and challenges. For example, advancements in medical technology can lead to new treatments and cures for diseases, while breakthroughs in renewable energy can help combat climate change and reduce our reliance on fossil fuels.

Furthermore, investing in American innovation can help create new opportunities for job creation and economic growth. Startups and small businesses are often the drivers of innovation, and by providing support and funding to these companies, we can help spur economic activity and create new jobs. Additionally, investing in education and training programs in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields can help prepare the workforce for the jobs of the future and ensure that we have a skilled labor force to drive innovation and growth.

Moreover, investing in American innovation can help strengthen the country's global competitiveness and position as a leader in technology and innovation. By supporting research and development, we can remain at the forefront of key industries and continue to drive advancements in science and technology. This can help attract talent and investment from around the world, further fueling innovation and growth in the United States.

In addition, investing in American innovation can help drive productivity and efficiency in industries across the economy. Through the adoption of new technologies and processes, companies can streamline operations, reduce costs, and improve their competitiveness in the global marketplace. This can lead to increased profitability and economic growth, benefiting both businesses and consumers.

Furthermore, investing in American innovation can help address societal challenges and promote inclusivity and diversity in the innovation ecosystem. By supporting programs and initiatives that promote diversity and inclusion in STEM fields and entrepreneurship, we can ensure that all individuals have the opportunity to contribute to and benefit from innovation. This can lead to the development of solutions that address the needs of underserved communities and promote a more inclusive and equitable society.

Moreover, investing in American innovation can help drive sustainable development and environmental conservation. By funding research and development in renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and clean technologies, we can reduce our environmental impact and promote a more sustainable future. This can help address issues such as climate change, resource depletion, and pollution, while also creating new opportunities for economic growth and job creation in green industries.

Additionally, investing in American innovation can help promote collaboration and knowledge-sharing among industries and sectors. By supporting partnerships between academia, government, and industry, we can foster a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship that can lead to new discoveries and breakthroughs. This can help facilitate the transfer of ideas and technologies across different sectors, leading to cross-pollination and the development of new innovations.

Furthermore, investing in American innovation can help attract investment and talent from around the world. By positioning ourselves as a leader in innovation and technology, we can attract entrepreneurs, researchers, and investors who see the United States as a hub for innovation and opportunity. This can help drive economic growth and create new opportunities for collaboration and partnership with international actors.

In conclusion, investing in American innovation is essential for driving economic growth, creating jobs, and increasing our global competitiveness. By supporting research and development, education and training, and diversity and inclusivity in the innovation ecosystem, we can foster creativity, drive technological advancements, and spur new industries and opportunities for growth. This can lead to a more prosperous and sustainable future for the United States and ensure that we remain at the forefront of innovation and technology in the global economy.

0 notes

Text

AWS C8g & AWS M8g: Efficient High-Performance Computing

Amazon EC2 Instances

Utilize the new Amazon EC2 C8g and M8g instances to run your general-purpose and compute-intensive tasks sustainably. Today Amazon EC2 C8g and M8g instances are now widely available.

AWS C8g

High-performance computing (HPC), batch processing, gaming, video encoding, scientific modeling, distributed analytics, CPU-based machine learning (ML) inference, and ad serving are suited for AWS Graviton4-based C8g instanc

AWS M8g

M8g instances, which are also Graviton4-based, offer the best cost-performance for workloads with a generic purpose. Applications like gaming servers, microservices, application servers, mid-size data storage, and caching fleets are all well suited for M8g instances.

Let’s now have a look at some of the enhancements it has implemented in these two cases. With three times as many vCPUs (up to 48xl), three times as much memory (up to 384GB for C8g and up to 768GB for M8g), seventy-five percent more memory bandwidth, and twice as much L2 cache as comparable 7g instances, C8g and M8g instances offer higher instance sizes. This allows processing larger data sets, increasing workloads, speeding up results turnaround, and lowering TCO.

These instances have up to 50 Gbps network bandwidth and 40 Gbps Amazon EBS capacity, compared to Graviton3-based instances’ 30 Gbps and 20 Gbps. C8g and M8g instances, like R8g instances, have two bare metal sizes (metal-24xl and metal-48xl). You can deploy workloads that gain from direct access to real resources and appropriately scale your instances.

C8g AWS

Important things to know

With pointer authentication capability, separate caches for each virtual CPU, and always-on memory encryption, AWS Graviton4 processors provide improved security.

The foundation of these instances is the AWS Nitro System, a vast array of building blocks that assigns specialized hardware and software to handle many of the conventional virtualization tasks. It reduces virtualization overhead by providing great performance, high availability, and excellent security.

Applications written in popular programming languages such as C/C++, Rust, Go, Java, Python,.NET Core, Node.js, Ruby, and PHP, as well as containerized and microservices-based applications like those running on Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (Amazon EKS) and Amazon Elastic Container Service (Amazon ECS), are ideally suited for the C8g and M8g instances.

Available right now

The US East (N. Virginia), US East (Ohio), US West (Oregon), and Europe (Frankfurt) AWS Regions currently offer C8g and M8g instances. With Amazon EC2, as usual, you only pay for the resources you utilize. See Amazon EC2 Pricing for additional details. To assist you in moving your applications to Graviton instance types, have a look at the assortment of AWS Graviton resources.

Read more on govindhtech.com

#AWSC8g#AWSM8g#EfficientHigh#PerformanceComputing#L2cache#AmazonEC2#AWSGraviton4based#R8ginstances#AWSNitroSystem#AmazonElasticKubernetesService#Amazon#technology#technews#news#govindhtech

1 note

·

View note

Text

To the State of Kansas, Department of Motor Vehichles

Hello...

My name is J.C. Lambert.

I've been carrying a corporate TPI card from Portland Oregon as ID for about 10 years now. Former employees of the State of Kansas working in the area had me attacked for my wallet and computer equipment: so I sort of had them killed by global authorities under Reaganite Instruction to massacre anyone who would state that marijuana is "legal". Under the endowments of the Regan administration: I can have almost anyone in the United States lawfully executed and their bodies processed into cannibal pharmaceuticals as well as gemstones from bone material. (howlite, opal, etc) Such products are then sold on QVC's global market as well as the internet.

I also reported my mommy dearest for treason and terrorism, then threatened to have her incarcerated for abuse, neglect, and abandonment of the mentally ill: which forced her onto a plane from Florida to Oregon. It also probably got her killed while traveling. I do not know. What I do know, is that my elder sibling sissy poo Tammy Barlow is being a right proper terrorist cunt next to mommy dearest and she too might have to die next to MOST citizens of Kansas. When and where someone is from tighty whitey Americana society: they can fall victim to the WORST government slaughter houses in todays age. Even and especially the police or any government employed persons, baby.

If my mommy dearest is still alive...

She would be getting tortured by Zia McCabe in Portland. Why? Because Tammy-poo decided to download all the music and share that music on Kazaa and other peer-to-peer networks. If she's alive, she would return home with every bone in her body broken and vaginal scars from tasers and other electrical devices. The west coastline gets psychotic when and where they cannot get a paycheck for their hard work. Sissy-poo Tammy has children who live incestuously and grandchildren who do as well. They like to steal identities, hack into emails, and they have servers with over 100 terabytes of illegally duplicated media. So its moreso fair to have them beaten and electrocuted. However mommy dearest still has to be beaten and electrocuted JUST for having ever given birth.

Me? I'm illegally adopted. My momma is Arabella Rees, Constable if you please. Just ask the bartenders in Cardiff and New Orleans. I'm perfectly a bastard.

Which, I am rocking that system of body bagging folks here in Kansas while the whole United States is under feudal law: especially if and when and where someone is rude or refuses me whatever I could possibly want. Me? I voted for peace and freedom so such things wouldn't happen. However I am in Kansas now, which puts me to work under Reaganite and Christian oppression. While Kansas has declared corporate war with peace and freedom, Kansas is forced into a position of "Terrorist State" by the Obama administration when and where the peace and freedom partier does not smoke reefer and can perfectly pass a urine test.

Too: I am from a Luciferian Society, so anyone who would identify as a modern Christian is perfectly to be called a hypocrite and corporate terrorist.

My social workers at TPI have me using their name card, while the feds separate all the who's who and lock up appropriate people who've been involved in psychosocial gang activity. While at a loss for my wallet: I am without my Florida, Colorado, California, or Kansas ID cards.

I am going to need state ID soon, my TPI card is wearing thin and my picture is starting to rub off.

I also understand that my TPI card might not be enough to use for the purpose of business. May I use three or four classmates from highschool and a yearbook photo?

Can you tell me what all I would or could possibly need for proper ID while I sit here kidnapped in the state of kansas and missing from everywhere else in the United States? If in Colorado or California: I could scan my fingerprint and wait about 30 minutes while a quick background check is ran.

I need Social Security...

I need Birth Record...

I need Identity Card...

My fingerprints are on a perfect driving record in California and Colorado. My fingerprints are on criminal record in Portland Oregon and probably Lawrence Kansas.

With that all said....

Give me 150 thousand digital resource. Now.

PayPal Link

why? Because I am still pissed off that your city and state have had other people living in my home at 510 W. Funston 67213 for the last 20 years. The ministers who backed the criminal charges of sodomy, where sort of murdered and their church has become a Buddhist Meditation center and NOBODY described as white is welcomed to be anywhere near my home. Especially neighbors and people who would identify me as "family".

I'm going to spend your money on dope and therapy.

I truly am.

#Wales#United States#Life#Black Lives Matter#Portland#Oregon#Kansas#Wichita#People#Law#Fuedal Law#Lordship#His Lordship#Digital Violence#Therapy#Peace and Freedom#Peace & Freedom#Peace#Love#Dope#Pot#Microdot#Peace Pot & Microdot

0 notes

Text

Process Service Company

A Process Service Company specializes in delivering legal documents such as subpoenas, summonses, and complaints to individuals or businesses involved in legal proceedings. Offering efficient and reliable delivery, they ensure legal documents are properly served in compliance with legal requirements, facilitating the legal process for their clients.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Preferred Process Servers

Preferred Process Servers is your go-to choice for process service in Oregon. With a commitment to excellence, Willamette Valley Processors, LLC ensures timely and accurate service for all clients. Reach out to us at 541 250-9654 or visit https://www.preferredprocessserver.com/ for professional assistance.

Our Social Pages:

twitter

youtube

pinterest

1 note

·

View note

Text

www.armenhyl.com

Happy Holidays from ARMENHYL GROUP LLC!

Local & Nationwide Civil Process Servers

Private Investigation, Mobile Notary Signings,

Security (866) ARMENHYL

[ [email protected]] (866) 276-3649

Private Process Servers

Contact ARMENHYL Today!

#armenhyl#private process servers#nationwide process servers#virginia process servers#New York process servers#Florida process servers#San Francisco Process Servers#Yonkers NY process servers#Maryland process servers#Louisville KY process servers#Colorado Process Servers#Richmond VA Process Servers#Chesterfield VA Process Servers#Mechanicsville VA Process Servers#Charlottesville VA Process Servers#Harrisonburg VA Process Servers#www.armenhyl.com#happy holidays#merry christmas#Oregon process servers#glen allen va process servers#civil process servers#service of process#Winchester VA process Servers#Staunton va process servers#Capitol Corporation Services#same day process service#we serve now#process server chesterfield va#contact ARMENHYL today

0 notes

Text

What Is a Subpoena?

On the off chance that you have gotten an authoritative record called a subpoena Server Lane County from a procedure server, it is significant that you comprehend what this paper is and what it intends to you. A subpoena is a request given by the court, generally expecting you to show up face to face at a specific spot, date and time to affirm as an observer about a specific case. In a criminal case, you can be subpoenaed distinctly to affirm in court. In a common case, you might be subpoenaed for out-of-court declaration also. In either sort of case, a subpoena may expect you to give records.

A subpoena must be conveyed face to face. As a rule this should be possible by one of the gatherings for the situation or by any individual who is in any event 18 years of age.

On the off chance that you are not one of the gatherings for the situation, you ought to get a participation charge and transportation costs (in light of mileage) for showing up at the assigned time and spot. In a common case, the individual serving the subpoena Server Lane County should give you money or a check for the participation charge and transportation costs when you are presented with the subpoena. In a criminal case, you will be paid your observer charge and mileage costs after you travel to the assigned place and affirm as an observer.

Peruse the subpoena cautiously. The subpoena will let you know: the names of the gatherings; the date, time and spot you should show up; the name of the legal advisor who gave the subpoena; and the area and sort of court where the case is occurring.

In the event that the subpoena expects you to bring certain records or different items, they ought to be portrayed in the subpoena or in a different paper given to you alongside the subpoena.

You may question recorded as a hard copy to any subpoena, posting all the reasons you think it is out of line or shameful for you to show up or to deliver the mentioned archives or items. Protests ought to be recorded with the court promptly, not on the date you are required to show up or give the archives. You might need to talk with a legal counselor to ensure that your protests are recorded effectively and on schedule.

A subpoena will likewise necessitate that you stay at the spot portrayed until the declaration is shut, except if the adjudicator pardons you. In any case, toward the finish of every day, you should contact the legal counselor for the gathering who subpoenaed you to see whether you might be known as the following day, or on a day later. This may assist with forestalling disarray or pointless time spent pausing.

In the event that you don't show up as the subpoena Server Lane County orders, you might be found in disdain of court. Hatred of court may bring about a prison term. The court may likewise expect you to pay remuneration expenses to the gatherings who may have been harmed by your inability to show up. The court may likewise give a warrant for your capture and request that the sheriff arrest you and carry you to where your declaration is required.

On the off chance that it is outlandish or amazingly hard for you to show up at the time required by the subpoena, call the attorney for the gathering who gave the subpoena. Generally, the legal advisor's name, address and telephone number will show up on the subpoena. The legal advisor may have the option to defer your declaration so you could affirm at some other point. You should remember, be that as it may, that the legal advisor will be unable to change the date and time of your mentioned appearance if a court date is as of now settled and can't be moved. In the event that it is completely incomprehensible for you to show up, or on the off chance that it would be truly destructive to your wellbeing or business, you should look for the guidance of your own attorney to choose if there might be legitimate justification for you to be pardoned. More info: https://orerivproservice.com/

#oregon process server lane county#legal document server lane county oregon#Subpoena Server Lane County

1 note

·

View note

Text

Manorpunk 2069 AD

📓 Research Complete: The Wyoming Method

Described as “one part Farmers’ Almanac, one part Robert’s Rules of Order, and one part motivational poster,” The Wyoming Method features detailed advice on everything from home gardening to labor organizing. Written and compiled in the early 21st century, it was originally intended to assist in the process of political self-sorting — a theoretical progressive tactic of moving en-masse to sparsely-populated ‘conservative states’ — but quickly found a new purpose during The American Crisis of the 2030s, as a “community in a box” for waves of displaced internal refugees. Its influence continued to grow in the 2040s as immigrants flooded into the Great Plains Autonomous Zone, hoping to create autonomous, self-sufficient communities out of its industrial carcass.

Many of these self-organized communities failed, but some of them, particularly Concordia, Landback, and the Iowan Khaganate, would grow to become regional powers after their victories in the Muskling Uprising. While The Wyoming Method remains controversial, with some historians describing it as “reorienting the American lower strata towards a sort of manorial peasant agrarianism,” “the 21st century equivalent of those phony Oregon Trail maps,” or “suspiciously aphobic or possibly terfy,” even its detractors are forced to admit that it preserved a wealth of information on traditional crafts and skills that might otherwise have disappeared due to the mass server collapses of the American Crisis.

Effects:

+25% Neo-Carpetbagging efficiency

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

HARRY BARTELL

November 28, 1913

Harry Bartell was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, but grew up in Houston, where he got his start in radio as an announcer. He had one younger brother who died at age 23. With his youthful sounding voice, Bartell was one of the busiest West Coast radio actors from the early 1940s until the end of the 1960s. He also served in the United States Army.

His first film experience was as an uncredited sailor in the Cary Grant film Destination Tokyo in 1943, but didn’t do another film until 1952, spending all his time doing radio.

Although he was most popular on westerns such as “Gunsmoke” (he later did ten episodes of the television series as well), he also was heard on Lucille Ball’s radio comedy “My Favorite Husband” where he played a drunk in “George is Messy” (June 1950).

In Fall 1952, Bartell did three television series: “Dangerous Assignment,” “Life With Luigi” and “I Love Lucy,” although records are unclear about which was his first filmed or first to premiere.

Bartell did three episodes of “I Love Lucy,” starting with “The Courtroom” (ILL S2;E7) which first aired on November 10, 1952, but was filmed on August 8, 1952. Bartell plays a process server who seems to arrive at the wrong apartment, looking for Miss Lewis. He recognizes bandleader Ricky Ricardo and asks for an autograph. Ricky doesn’t realize he’s signed for a summons and is served papers to appear in small claims court in the matter of “Mertz v Ricardo”!

Bartell returned to the series to play the headwaiter who serves William Holden at the Hollywood Brown Derby in “Hollywood at Last!” (ILL S4;E16). Bartell is apologetic that Holden is being ogled by Lucy, but hasn’t got another table to re-seat the star.

His third an final appearance was as the jewel thief in “The Great Train Robbery” (ILL S5;E5).

The jewel thief gains Lucy’s confidence in order to get to Mr. Estes (Lou Krugman), the jeweler in the next compartment. As with all of his “Lucy” characters, he does not have a name and he appears uncredited.

He did two episodes of the Desilu helicopter series “Whirlybirds” in 1957 and 1959.

He did two episodes of the hit Desilu crime drama “The Untouchables” in 1959 and 1961. This would be his final time working for Lucy and Desi.

His last screen appearance was in the TV film Mobile Two in 1975. This was a pilot for a reboot of “Mobile One”, a series tarring Jackie Cooper.

On February 26, 2004, Harry Bartell died in Ashland, Oregon. He was 90 years old.

#Harry Bartell#Lucille Ball#Lucy#I Love Lucy#The Courtroom#The Great Train Robbery#TV#The Untouchables#Whirlybirds#Hollywood at Last!#Mobile Two#My Favorite Husband#Destination Tokyo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Surveillance is the new blooming onion at Outback Steakhouse

Thom Dunn:

The friendly surface-level rationale behind any mass data collection via surveillance is improved efficiency through metrics. With the right amount of the data, and the right analysts working through it, you can optimize pretty much any process. From a business perspective, this could potentially present new ways to work smarter, instead of working harder — increasing profits and productivity through better decision-making, which ultimately makes everyone happier.

In that context, it makes sense why a chain restaurant like Outback Steakhouse might be interested in implementing its own mini surveillance state. So far it's only limited to a single franchise in Portland, Oregon which is operated by Evergreen Restaurant Group. But Evergreen also owns some 40-other Outback Steakhouses throughout the country, which means this small pilot program could seen be expanded, if the suits think the metrics work out in their favor.

This particular surveillance experiment relies on facial recognition and other technology provided by Presto Vision, who claims to offer "real-time actionable restaurant insights." From Wired:

According to Presto CEO Rajat Suri, Presto Vision takes advantage of preexisting surveillance cameras that many restaurants already have installed. The system uses machine learning to analyze footage of restaurant staff at work and interacting with guests. It aims to track metrics like how often a server tends to their tables or how long it takes for food to come out. At the end of a shift, managers receive an email of the compiled statistics, which they can then use to identify problems and infer whether servers, hostesses, and kitchen staff are adequately doing their jobs.

“It’s not that different from a Fitbit or something like that,” says Suri. “It’s basically the same, we would just present the metrics to the managers after the shift.”

Again: from a corporate board room standpoint, this makes sense.

In practice, however, the pressure from this kind of surveillance tends to have a massively negative impact on the workers. People act differently when they know they're being watched, and when they know they're being actively judged on that. It might discourage them from acting outside of their routine, even when it might potentially benefit the customers — for example, using jokes to establish a personal connection with the customers. And if the customers are unsatisfied, for any reason — even if it's unrelated to the server's performance — then that could reflect poorly in the metrics. What could have just been one bad tip now goes directly to your boss, who might decide to cut back on your shifts because of that one bad tipper — who, for all they know, may have been an asshole and a lousy tipper anyway. Now, that server is in the hole for more than a single lousy tip; their income is down overall, and their stress is up as a result, increasing the chance that they might actually screw up on the job, thus providing the justification that the employer needs to cut their hours back even more, which is exactly what exacerbated the problem in the first place.

Don't get me wrong: a reasonable amount of data metrics could help a restaurant to optimize for improved efficiency. That's why sometimes small, busy urban restaurants can be faster at seating and serving than a physically larger space in a more low-key area. Different restaurants in different places have a different gauge for what constitutes as "busy," or how many tables they expect or hope to flip in any given night. There are valuable things that a restauranteur can learn and use. But once you start treating human employees like a canning machine on a production line, you're going to start losing out on the humanizing part of eating out. And that ultimately leaves you with a cold dining experience topped with 2,000 calories of fried battered onion.

No one wants that.

https://boingboing.net/2020/01/23/surveillance-is-the-new-bloomi.html

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boost Your Large In-Memory Databases & Business Workloads

In-memory databases help energy, financial services, healthcare, manufacturing, retail, telecom, media, entertainment, gaming, government, and public sector enterprises. They also support business-critical operations for these companies.

Performance is crucial because they require real-time or nearly real-time transaction and analytics processing for a wide range of use cases. However, cost effectiveness is equally crucial in the modern world of accomplishing more with less.

AWS in memory database

For high-memory applications, Amazon EC2 U7i custom virtual instances (8-socket) provide the scalability, high performance, and cost-effectiveness that enterprises want. They also support in-memory databases like SAP HANA, Oracle, and SQL Server.

With 896 vCPUs and up to 32 TiB of DDR5 memory, these 4th Gen Intel Xeon processor and Intel Advanced Matrix Extensions (Intel AMX)-powered 8-socket U7i instances provide the compute and memory density required to extend transaction processing throughput in rapidly expanding data environments.

U7i instances are a great option for the present and the future since the demand for high-memory cloud solutions, including AI models, will only increase as large-scale data models whether developed by internal organizations or external vendors become more prevalent.

Intel AMX, an AI engine built into Intel Xeon Scalable processors, reduces the requirement for specialized hardware while speeding up inferencing and training. This results in exceptional cost savings. These integrated accelerators are located close to system memory in each CPU core. A faster time to value is made possible by the fact that Intel AMX is frequently easier to deploy than discrete accelerators.

Benefits for Businesses

U7i instances give enterprises a quick, easy, and adaptable approach to manage their mission-critical, large-scale workloads. Additional benefits include of:

Extremely Flexible: In data environments that are expanding quickly, organizations can readily scale throughput.

Superb Work: Compared to current U-1 instances, U7i instances have up to 135% greater compute performance and up to 45% better price performance.

Decreased Indirect Costs: With U7i instances, you can operate both business apps that rely on large in-memory databases and databases themselves in the same shared Amazon Virtual Private Cloud (VPC), which guarantees predictable performance while lowering the management burden associated with sophisticated networking.

Worldwide Accessibility: U7i instances come with operating system support for Ubuntu, Windows Server, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, SUSE Linux Enterprise Server, and Amazon Linux. They are accessible in the US East (North Virginia), US West (Oregon), and Asia Pacific (Seoul, Sydney) AWS Regions. Regularly, new regions are added.

Quick and Simple to Start: Buying U7i instances is simple, allowing you to start using them right away. In addition to shared dedicated instance and dedicated host tenancy, purchase choices include On-Demand, Savings Plan, and Reserved Instance form.

What is in memory database?

In contrast to conventional databases, which store data on disc, in-memory databases store data mostly in main memory (RAM). Because accessing data in RAM is far faster than accessing data on a disc, this makes in-memory databases substantially faster for data retrieval and modification.

The following are some salient features of in-memory databases:

Benefits of in memory database

Speed: In-memory databases’ main benefit is their speed. Read and write operations are substantially faster when data is stored in RAM as opposed to disk-based storage.

Volatility: Data is lost in the event of a system crash or power outage because RAM is volatile memory. Many in-memory databases offer data permanence features, including transaction logs and recurring disc snapshots, to help reduce this.

Use Cases: Applications that need to handle data quickly, such real-time analytics, caching, and session management, are best suited for in-memory databases.

Example of in memory database

Redis: Popular in-memory data structure storage for real-time analytics, message brokers, and caches.

Memcached: A fast distributed memory object caching solution that minimizes database demand to speed up dynamic web apps.

H2: A memory-efficient, lightweight Java SQL database for development, testing, and small apps.

The cutting-edge relational database management system SAP HANA is for analytics and real-time applications.

Performance: Because RAM is used, data access and processing are incredibly quick.

Scalability: Frequently made to expand horizontally, this feature enables load balancing and distributed computing.

Decreased delay: Perfect for applications that need data access with minimal delay.

Disadvantages of in memory database

Cost: Large-scale in-memory databases are expensive since RAM is more expensive than disc storage.

Data Persistence: Adding more methods and potential complexity is necessary to ensure that data is not lost in the event of a power outage.

Limited Capacity: The RAM that is available determines how much data can be kept.

Persistence Mechanisms

In-memory databases frequently employ a number of strategies to deal with the volatility issue:

Snapshots: Writing the complete database to disc on a regular basis.

Append-Only Files, or AOFs, record each modification performed to the database so that the information can be replayed and restored.

Hybrid storage refers to the combining of disk-based and in-memory storage to provide greater storage capacity and data longevity.

Utilization Examples

Real-time analytics: Quick data processing and analysis, crucial for e-commerce, telecom, and financial services.

Caching: Keeping frequently requested data in memory to lighten the burden on conventional databases.

Session management is the process of storing user session information for online apps so that the user experience is uninterrupted.

Gaming: Keeping up with the rapid updates and data changes that occur in online gaming environments.

In summary

Applications that demand real-time data access and processing can benefit greatly from the unmatched speed and performance that in-memory databases provide. They do, however, have limitations with regard to cost, capacity, and data persistence. These difficulties can be overcome by utilizing suitable persistence methods and hybrid storage options, which makes in-memory databases an effective tool for a range of high-performance applications.

Read more on govindhteh.com

#memory#memorydatabase#amazonec2u7i#DDR5memory#cpucore#u7i#Amazon#AWS#aimodel#AI#SQLServer#news#TechNews#technology#technologynews#technologytrends#govindhtech

0 notes

Text

Clipping USA

Clipping USA is a Professional Clipping Path Service Provider located in Maryland, the USA which is operated by some highly experienced professionals. It provides the best quality for Photo Editing Service / Image Editing Services all over the world. It has become a world class Online Image Editing Service Provider for its extraordinary working skills and practical experiences. Our Customers have a good experience with “Clipping USA” and acknowledge it as one of the best Clipping Path Company in Maryland. Most of our existing customers are from the USA, Canada, Australia, UK, Germany, Sweden, Italy, Denmark, Netherlands, Japan to name a few. One can easily differ "Clipping USA" from any other competitors as a reliable Photoshop Clipping Path Service Provider especially for the best prices, turnaround, quality, and communication.

Key Features:

Low Cost Image Editing Service with Excellent Quality, Quick Turnaround time, Highly Experienced Graphic Designers, 24 Hours Shifting Duty Plan Round the Year, Frequent Quality Checking System, 100% Money Back Guarantee, High Speed Internet, Easy and flexible system for upload and download files, Safe FTP System, Reserved Team in order to Rush/Urgent Delivery.

Our Vision:

We had the vision to show our ability and skill to the global market as a competitor of other renowned Photo Editing Service Provider companies. We would love to introduce Clipping USA to the international community of Graphic Design and Online Photoshop service buyer.

get a quote

experience the quality & cost effective service.

Clipping USA has a team of 135 professional Image Editing artists. They are ready to fulfill your requirements by providing the best quality for any of your expected online outsource services as a renouned Clipping Path Service Company. Our team members have a vast knowledge of Photoshop, and Photo Editing Service as most of them have been graduated from reputed graphic institutions. They are devoted and dedicated to the welfare of this organization. Each team is assigned with a team leader to lead their group effectively who is supplied with all technical facilities and freedom for a fair work environment. We usually offer all kinds of Photoshop Image Editing Service at a remarkably lower cost.For all of our customers – the offering service names are given below since these are called as different names by Global Customers. So we also named them in details here.

Image editing services: Clipping path service– (outline path, color path, image silo, photoshop clipping mask, multipath/multiple clipping paths, Photo cut out, cut out an image, Background removal, remove background from image or deep etching service. Photoshop masking service– (Image masking/Photo masking, layer mask, photoshop hair masking, masking in photoshop alpha channel masking). Photo retouching services– (professional photo retouching wedding photo editing, model retouch, product retouch, jewelry retouch, image enhancement, photo restoration and retouching). Shadow creation service– (light manipulation, shadow manipulation, drop shadow, natural shadow, reflection shadow, original shadow). Image Manipulation Service– neck join/neck joint/ghost manipulation/ghost mannequin. Color correction service– Color changing,photoshop color correction Color adjustment,color correction in photoshop. Logo Design Service– creative logo design for e-commerce or multi-national company and raster to vector conversion services.

Best Clipping Path Service offer.

youtube

Clipping USA offers a cost-effective Clipping Path Service for our Global customers. Our basic price is US$0.25 per image only for clipping. We believe that our reasonable price and quality will make a path to a reliable business relationship.

Our production facility is for 24/7. Clipping USA keeps its service operational every day. No matter what our clients are guaranteed to have our services even on Christmas vacation. As an offshore outsourcing company, we ensure you for guaranteed Image Editing Services solution. To add here, we can handle 3500-5000 images daily for clipping path or background remove service.

Clipping Path Service Near Me

United States -USA

Alaska, Arizona

California

Colorado

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Indiana

Louisiana

Massachusetts

Michigan

Mississippi

Montana

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

Oklahoma

Oregon

Ohio

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

New South Wales

South Australia

Queensland

Tasmania

Victoria

Western Australia

Northern Ireland

England

Scotland

Wales

A Special Discount On Clipping Path Service!!!

Free Trial

youtube

Clipping USA explores the things which are essential for customers. No doubt a customer usually takes a short review on a service provider company. To assist in this regard has been represented it's abilities, global values in photo editing services. For a client to begin or keep on working with a company there should be a convincing reason that we takes with extreme confidence to announce the name Clipping USA where a customer must get a better service. It is the best Image Editing Company recognized by its thousands of Customers.The acknowledgment of customers gives a shade on the ultimate result of each completed project.

We always focus on Client benefit that is essential and in this case, a customer can also differentiate our company Clipping USA from other competitors in the competitive market. The relationship with customer works as a component of the business. We approach our clients with deference and make them feel exceptional or special. The key, obviously, is that the excellent dimension of our image editing services must be steady and everybody in our business plan. It provides some of the committed services in USA, Canada, Australia, Sweden, UK, Denmark, Italy, Japan, and some more countries with maintaining a high standard.

Clipping USA provides some of the committed services to it's customers of USA, Canada, Australia, Sweden, UK, Denmark, Italy, Japan, and some more countries with maintaining a high standard.The services are Clipping Paths, image masking, photo retouching, background removal, color correction, hair masking, high-end touch-up, product shadow creation, neck joint service, vector conversion or any other image editing service. Clipping USA allows the upload platform that is convenient to customer, as Like Hightail, Dropbox, FTP, WeTransfer, Google Drive or any others. Clipping USA also provides the dedicated server facility especially for the regular customers.

youtube

Specialties

We always focus on Client benefit that is essential and in this case, a customer can also differentiate a company in the competitive market.

Rush Service

Overnight Delivery

Hand-drawn Clipping Path

Price Starts at $0.25

Volume Discount on bulk orders

More Benifits

Lorem ispsum dolor sit amet Lorem ispsum dolor sit amet Lorem ispsum dolor sit amet Lorem ispsum dolor sit amet

KEY Advantages

The clients will have some advantages of Photograph Altering from Clipping USA: Appropriately altered photos speak to the brand and pass on an organizations' message in the most ideal way.

Brand Building

Better Deals

Manufacture Decency and Validity

Hearty Online life Procedure

Get a better Proficiency

Our Image Editing Services

Photoshop Clipping path | Image Silo

Background Remove | Photo Cut Out

Image Masking

Photo Retouching

Shadow Creation

Neck Join | Ghost Mannequin

Image Manipulation

Raster to Vector Conversion

Photo Retouching

PORTFOLIO of Image Editing Service

All

Clipping Path

Masking

Retouching

Drop Shadow

Natural Shadow

Reflection shadow

Color correction

Neck Joint

Vector

Free Trial Get in Touch and Start a Project with UsIf the file size is more than 20 MB, kindly use our web upload system to send your test images. We will reply you within a few minutes.Select Category Background Remove Image Masking Photo Retouching Shadow CreationNeck JointImage Manipulation Vector Conversion Glamour Retouching UploadOur Photo Editing Services Home Vector Conversion Raster to Vector Conversion: Clipping USA provides flawless and accurate Raster to Vector Conversion. Raster images are the series of pixels or digital dots arranged in certain and Read More Home Photo Editing Service Photo Editing Service: To make any kinds of change on a photo is called photo editing. It depends actually on one’s needs. Basically a Read More Home Clipping path Photoshop Clipping Path is a technique that is mostly used for removing background of original image. It is used for Media photographers, web design organization, fashion agencies, magazine design Read More Home Masking Photoshop Masking Service is the process to remove or replace the background of the complex images having numerous turns and curves with blurred or fuzzy edges. This technique is applied where only Read More Home Retouching In the photo editing sector retouching is the most important service. It plays a vital role to make a raw photograph into a new style and attractive looks. By this service you can Read More Home Shadow Shadow service is a system of graphic design which creates an object over the rest of an image by laying a direct shade behind the object. This is used to add a Read MoreClipping Path experience with quality & cost effective service.Clipping path is a way or system which is applied with Photoshop pen tool to cut out an image from its background using a closed vector path or shape. It implies this is the manner in which that is utilized to expel and alter the foundation of a picture. Reasonable Price Faster Turnaround Unique Quality 24/7 Service get a quote photoshop masking experience with quality & cost effective service.Photo retouching services is generally used to fix the faded, rough, badly cracked or damaged photos. This service applied to make a photo more wonderful as well. There are numerous methods, tips & tricks for enriching things from the inner side of a photo as blemish, skin tone and increasing the photo’s qualities. Reasonable Price Faster Turnaround Unique Quality 24/7 Service get a quote photo retouching experience with quality & cost effective service.Clipping USA is expertise on professional photo retouching service on photograph. Customers will get a picture upgrade benefits in mass for freelance photographer, weeding photography, photograph studios, visual creators and offices, advertisers agency, online business website proprietors, printing and distributing organizations, and some more. The cost is exceptionally focused and furthermore clients are getting something special from . So why not pass judgment on us for photo retouching service. Reasonable Price Faster Turnaround Unique Quality 24/7 Service get a quoteneck join experience with quality & cost effective service.Clipping USA offers neck joint service to remove mannequin from image, ghost manipulation, ghost mannequin, neck joint by Photoshop utilizing specialists in visual computerization. This service have been utilized by online retailers, eCommerce Photography, stock photography organizations and online eCommerce store owners,internet business shop proprietors, stock photography eCommerce shop owners and online product sellers, eBay, amazon and other affiliate marketers. Reasonable Price Faster Turnaround Unique Quality 24/7 Service get a quote Photo Retouching Services Real Estate Photography Retouching Our Real Estate Photography Retouching service include an enticing environment, legitimate lighting, and exact scale to your land photographs which will undoubtedly pull in property seekers. To increase more business sales it should be taken the advantage of quality service.Product Photo Retouching Product Photo Retouching brings a new looks for images and increase online business sales. Clipping USA enables the pictures to settle lighting issues, expel foundations, and improve the item's to meet the advance market by following clients requirements and obviously at lowest cost.Portrait retouching or Correcting Clipping USA gives a guarantee that the pictures look normal and practical after editing by Photoshop. We are all around prepared in giving proficient looking pictures, while keeping away from the utilization of digitally embellishing methods. Clients can expect a better appearance of edited images.Jewelry photo Retouching Clipping USA does have a devoted group of editors who work with gems picture for jewelry shop, online retailers, E-commerce freelance photographer. We modify adornments pictures by utilizing sparkle improvement, altering center stacking, foundation expulsion, scratch evacuation, and so forth.Amateur Photo Retouching Clipping USA has expertise on Amateur Photo Retouching work. Aside from this we additionally enable to utilize and also brings a better experience for Amateur Photographers. It's a special ability of Clipping USA that never makes a customer unhappy. So one can contact for a unique photo retouching service.Wedding Photograph retouching Our master group of photograph editors at Clipping USA guarantees that your wedding recollections are depicted in the most ideal way. We embrace all thoughtful s of wedding photograph modifying and post-preparing administrations, for example, practice photographs, wedding representations, and so on.Working procedures & disposal We give the special importance to the things are related to clients demands. Customers always expect a unique service that we offer and provide with the touch of service that best suits you and your project. Some customers will request solutions through the schematic style, and others will demand a full edited file with detailing. We pay attention to you and provide precisely what you exactly need.We continue steadily to prefer direct, personally get in touch with as the easiest method to work and offer support. We don’t like hiding behind a screen - we prefer to display who we are and how exactly we are in full.Image clients evaluation" Thanks So Much For All Of Your Great Work the past couple of days. Really good job on all of my images, very appreciated!!! "-- Rick" As always… Fantastic job and turnaround. You guys are the best in the business (and I’ve tried a lot of the companies out there). I wouldn’t go anywhere else after using you. Thanks! "-- Mike" I cannot thank you enough! You saved us from a very unhappy client! "-- Daphne" Thank you very much! You guys are truly awesome. "-- Uche" Oh my, your team did a fabulous job. I will be in touch "-- Erin" WOW!!!!!! You guys are amazing!! You are above and beyond expectations on the retouching. We are so happy with your service. I know quite a few photographers in the business and I am telling them all about you. "-- Pat" You are AWESOME! Excellent Work!! THANK YOU! "-- Michelle" I successfully downloaded all the files and am extremely happy! You guys did an amazing job! I am convinced! Your quality is amazing! Very, very well done!!! Thank you! "-- ScottIncreasing Sales and Driving Deals with Substance in Online business:Amazon is a worldwide innovation organization centering in web based business. It is the biggest web based business company as estimated by income and market capitalization.Internet business stores are turning into a fever now days, moving electronic items, clothing, furniture, nourishment, toys and gems and huge amounts of different items. Be that as it may, everybody passes up "utilizing upgraded item pictures"; which on occasion costs them truly. Redistributing item picture altering to specialists could enable them to set up enhanced pictures on Internet business. Online stores can't give that genuine shopping background and subsequently; they draw in the feeling of sight without bounds. The client can't grasp the item, smell its aroma or feel its surfaces thus they additionally take obtaining choices absolutely dependent on the all-around altered item pictures of the items they are.

P.O BOX; 10623 SILVER SPRING, MD. 20914 UNITED STATES.

+1 240 918 9262, +1 (301) 310 6411

Production Facility

HOUSE # 06, ROAD # 02, SECTOR # 11, UTTARA, DHAKA-1230, BANGLADESH.

+1 240 918 9262, +1 (301) 310 6411

Physical Address

12910 TAMARACK RD, SILVER SPRING, MD. 20904 UNITED STATES.

+1 240 918 9262, +1 (301) 310 6411

Copyright © 2019 Clipping USA

error: Content is protected !!This site uses cookies for a better user experience Okay, thanks

#clipping path#clipping#path#usa#clippingusa#clipping path service#photoshop masking service#drop shadow service#photo retouching service

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Jordan Michelman

The cows are named Baby and Snowday. Baby is a beautifully mottled brown and white, and Snowday is a solid, milk chocolate brown, her head topped with a tuft of funny cream-colored fur. They both have the most delicate eyelashes, bashful and lush. They are five years old, which is old for a cow in America; these are retired milk cows, once living on a family farm as part of Darigold, a farmers’ cooperative that works with small dairies across the Pacific Northwest. In their twilight years now, they’re at Vorfreude Dairy Beef, a farm off a long, loping little country road in the green foothills outside of Portland, Oregon. It’s owned by small-scale beef purveyor Rachel Hinnen, and today she is “harvesting” these animals—she is preparing them for slaughter. Hinnen is part of “the meat community,” as she calls it. While you can find people pursuing ethical meat production in many corners of the world, the practice has particularly gained traction in this slice of the American Pacific Northwest, where a “conscious carnivorism” movement, which advocates buying hyper-local meat or practicing butchery, has been growing for at least a decade. You might be familiar with Colin the Chicken of Portlandia fame, a skit in which a restaurant server describes to diners the name and life of the chicken on their plate. Or, more recently, a viral Tweet of the fake Uber Eats feature “Meet Your Meat,” in which you can learn that your rib eye was named Janice and enjoyed alfalfa. But the real-life meat community is serious—a more earnest group of true believers you will not find anywhere, with a conviction that borders on semireligious. You should meet your meat, they believe. In fact, to truly eat meat ethically, this means observing every step of the process: birth, life, and death, from the pastures to the butcher shop.

“I’m really glad you’re here for this,” Hinnen tells me as we stand together in the February mist. She wears a no-nonsense work hoodie, slate tights, and muck boots, her long blonde hair tucked beneath a knit beanie. “I think it’s really important to experience this part.”

The sky is warship gray. Rain falls like television static. The mobile slaughter truck is due in one hour, and the field is redolent with the smell of cow shit. Baby and Snowday—named by the family dairy where they previously resided—are not the only bovines on the property. In the pen behind us stand a group of retired Jersey dairy cows, squat and fat and rust-colored, who are marked for slaughter in the coming weeks. In the next pen over three more cows—“my pets,” she says—who go by the names Domino, Lucy, and Oreo.

“I can’t kill the OGs,” she laughs. Domino and Oreo (two classic black-and-whites) have developed the rapscallion habit of hopping fences, which one might think would mark them for the slaughter truck but has instead endeared them to Hinnen, the way a problem child is often a mother’s secret favorite. Lucy (latte brown and cream) is another story entirely. “She accidentally wound up pregnant,” Hinnen tells me, “and I spent three weeks saving her life every day from a series of complications. By the end, I felt like, you know—‘I nearly killed myself trying to save you, so how can I kill you now?’”

Much of the beef we consume in America comes from younger cows, aged between 18 and 24 months old. Most are raised specifically for beef production, the product of generations of selective genetic breeding to increase yield size and fattening speed, aided by a modern cocktail of hormones and antibiotics. Beef from older cows—including dairy cows—has long been commonplace and revered in Europe, particularly in Spain, Austria, and the United Kingdom. But in the United States, dairy cows past their prime are typically blended alongside thousands of other animals a day as part of a general ground meat supply.

Retired dairy beef is highly prized by a small but enthusiastic number of American beef connoisseurs, showing up at specialist butcher shops and on farm-to-table restaurant menus. Some small butchers separately slaughter certain cows like Snowday and Baby so that their meat can be sold and consumed individually, their unique flavors more present like those of a single-origin specialty coffee microlot or a walled clos of hallowed Champagne grapes.

I’m given a bit of busy work feeding Hinnen’s pet cows—a.k.a. the permanent collection—from a plastic pail of compressed hay treats. They lap it up from my hands with their massive prehensile tongues, agile as monkey tails, frothing with saliva and anticipation. (The word vorfreude in German means “joy in anticipation.”)

“A cow never had a better life,” Hinnen tells me, preparing a bundle of sage as a sort of preharvest ritual she conducts on mornings like this one, balancing the herbs carefully atop a fence post. I hand her my lighter—hers is in the truck—and her words grow uneasy. “I hate these days,” she says. “I don’t sleep well. I cry over every single one of these cows, and I fall in love with every single one.”

I ask about the inherent contradiction of this, you know—loving an animal so much throughout its life and then overseeing that being’s death. “I get what you’re saying,” she says—she’s heard this question before—“but truth is, it would be a problem if I didn’t feel that way. It would mean I didn’t care, you know? And the point of all this. The point is to care.”

Smoke billows from the sage, and the smell immediately alters the cows’ demeanor; they become noticeably mellower, even contemplative. Or is that just my projection? My own anxieties?

“Let me send you back over to the Jerseys for a minute,” she tells me. “I want to make a video and I get self-conscious.” Hinnen climbs into the pen, crouches down in the shit and muck, and talks quietly into her phone as the rain falls, the sage scenting the air, the cows posing just beyond her shoulders, framed artfully in the shot. Later, the video appears in Hinnen’s Instagram Stories, an instantaneous update for those who cannot be here to witness their steak being killed.

The origin story of the meat that Americans consume is fundamentally uncomfortable, like that of our clothing or rechargeable batteries. Meat consumption as a narrative is fundamentally informed by death; it’s always there, lurking, like the omnipresent specter in Hitchcock or Shakespeare. The wider conversation about the ethics of consuming meat dates back to Plato, Pythagoras and Epicurus, as well as the Buddha, the Bhagavad Gita, and the concepts of halal and haram in Islam, which, among other rules, consider how an animal is slaughtered before it is eaten. Across cultures and centuries, meat consumption—both our love of it and the questions it raises—is woven into the fabric of who we are, fundamental to a broad panoply of faiths. From the oldest cave paintings of water buffalo hunts to widely varying modern screeds (“Our Moral Duty to Eat Meat” versus “Moral Veganism”), seemingly everyone—and everyone’s ancestors—has a take.

The current ethical meat movement isn’t new either, with organizations like the Ethical Omnivore Movement drawing a sharp line between the consumption of factory-farmed meat and dairy and other, smaller means of arriving by these products. (“There should be no shame in the use of animal-based products—just in the cruel, wasteful, careless, irreverent methods of production,” its website reads.) Guides to ethically eating meat abound, even as we wrestle with the so-called meat paradox, in which animal lovers are still able to enjoy that delicious cut of steak.

What’s novel today is the extremely online-ness of it all. Social media has intertwined with the age-old practice of raising animals for meat in a distinctly modern way; everyone and their mother is quite literally on social today, and America’s family farms, butcher shops, and heirloom meat geeks are no exception.

I found out about Vorfreude Dairy Beef via this great discovery engine of our time. That said, Hinnen’s Instagram account, @vorfreudedairybeef_, is tiny with barely 500 followers. Her business involves direct sales of beef “shares”—typically a quarter of the whole slaughtered cow, sold at $6.85 per pound on the hanging weight—to home chefs, friends, and assorted beef enthusiasts. She also makes candles, soaps, and body butter from beef tallow processed in her own home kitchen and sold at local farmers markets and retail pop-ups, and she’s working on a line of tanned leather wallets, earrings, and belts. Plus, “cow yoga retreats” and “photo sessions.”

Some little kids might circle toy ads in the Sunday paper; Hinnen, age 10 in suburban Oregon, would scout the classifieds section for old cattle ranches, begging her baffled parents for cattle and land. After high school, she deferred college to work on a vast cattle station in rural Australia, and now, at 33, she’s built a small, intimately personal business around raising cows, loving cows, and yes, slaughtering them to produce high-quality grass-fed beef. “Since I was old enough to have dreams,” she says, “I have dreamed about this.”

Others also have. Larger accounts like Big Sky Caroline, Five Marys Farms, and Ballerina Farm have built #ranchlife followings in the thousands, to say nothing of Star Yak Ranch, the yak meat and jerky concern of social media provocateur Jeffree Star. From farmers like Caroline Nelson of Big Sky Caroline entering her “sheep doula era” (assisting in the birth process of a lamb) to a retired Holstein cow “living her best life” (receiving a loving brush down from Hinnen) at Vorfreude, some of this content reflects an aspirational lifestyle, although that is quickly offset with #farmlife realities: long days, early mornings, missed family events, and financial struggles.

The meat community functions around a fundamental moment of tension, in which the animal—named, loved, filmed, the source of countless joys and heartaches and sleepless nights (not to mention shares and likes)—moves along to the Great Ranch in the Sky. In this way it is meaningfully distinct from pet influencers and the myriad animal-obsessed tribute accounts (my favorites are @itsdougthepug and @ekekekkekkek, respectively), but I do think it still relates to the grand infinitesimal why behind how our brains respond to cute animals. Your favorite rancher is now on your social media feed, goofing off with an adorable 1,000-pound cow.

Hinnen estimates around half of her business comes from social media, and she considers it a tool for both sales and culture, a way to sell the bigger picture experience of her product to curious followers who may one day become future customers. “Social media also offers us an opportunity to educate,” says Sean So, the cofounder of Preservation Meat Collective, a company that links tiny ranches and heritage-breed animal farmers across the Pacific Northwest with butcher shops, restaurants, and direct-to-consumer connoisseurs of small-production beef, lamb, fowl, and game. He tells me a rib eye is just two percent of the meat on a cow, a wasteful amount. “The way meat is bought and sold in America is so incredibly broken, and we’re trying to teach people that every day online.” Some days, that’s advocating for unsung cuts, like ranch steak (also known as “arm steak”), and other days it’s educating on the age and life cycle of the animals we consume.

So was born in Cambodia and moved to Bellingham, Washington, as a child. “I’ve been harvesting animals my whole life,” he tells me. His father would buy whole animals from farmers and split them between multiple families. Today So and Preservation cofounder Travis Stanley-Jones work with a network of more than 35 individual farmers, connecting, say, Wagyu beef cattle from Enumclaw, Washington, with restaurants in Seattle, or fresh squab from Benton City, Washington, with a butcher shop in Ballard, a neighborhood in Seattle. The company works with a who’s who of restaurants across Washington State, including more than a dozen places such as Off Alley, Restaurant Homer, Hanoon, and many more. “Our goal is the opposite of greenwashing or hiding behind the gray areas of meat production,” So says. “We’re trying to build a new kind of commodity system that is not commoditized.”

On Instagram, the effect is the opposite of nameless, faceless factory farming. Preservation’s account opens a portal into the world of small-production meat—one day it’ll post about signing a new lamb purveyor that happens to be a fifth-generation family farm, the next day a video of So proudly discussing the 14-hour harvest process for fresh squab. This work follows people raising protein outside of traditional systems and animals apparently living very different lives—longer, with fresh air and clean grass—than the millions of cows, pigs, and sheep slaughtered each day in factory farms. Followers see the whole cycle, from photos of cows in the pasture to the slaughterhouse to dining rooms.

Give modern humans all the knowledge of the universe in the palm of their hands and they’ll use it to talk about shepherds and sheep, ranchers and beef, and how to butcher and cook the finished product. We’ve social networked ourselves back to the very origins of collective agricultural living, using the unthinkable vastness of God in our pockets to become more like our ancient selves. There’s something adorable about that—comforting, even—and something brutal too.

“At the end of the day, the animals need to die,” So tells me. “They need to go to harvest.”

“The waiting is the hardest part,” Hinnen says, joining me by the Jerseys.