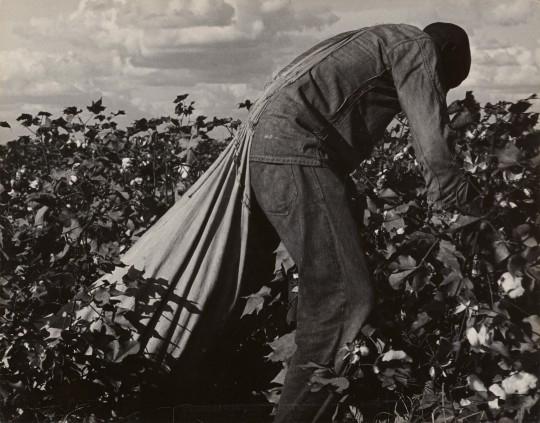

#Stoop Labor in Cotton Field

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Stoop Labor in Cotton Field, San Joaquin Valley, California

1938

Dorothea Lange (American, 1895 - 1965)

"An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion was published by Dorothea Lange and Paul Taylor in 1939 as a collaborative effort between "a photographer and a social scientist." The book was divided into six sections—Old South, Plantation under the Machine, Midcontinent, Plains, Dust Bowl, and Last West—each containing a portfolio of captioned images by Lange followed by a historical text by Taylor. The pictures in the first section consisted of field laborers and poor homes photographed in Alabama and Georgia. The anonymous cotton picker seen here serves to illustrate Taylor's essay, appearing just above his opening paragraph. Lange's view of the man's form make this difficult, exhausting work look graceful; the coarse cloth of his overalls and heavy bag crease and hang in beautiful ways.

In the revised and expanded edition of An American Exodus, issued by the Oakland Museum in 1969, this picture is accompanied by a caption from Taylor's field notes from the San Joaquin Valley in November 1938: "Migratory cotton picker paid 75 cents per 100 pounds. A good day's pick is 200 pounds. CIO union strikers demand $1 per 100 pounds." According to The WPA Guide to California, the state had been producing an important variety of cotton (Alcala) since it was introduced in 1917; in 1937 the average yield per acre was nearly twice that of the rest of the country. Although Lange did photograph workers planting and harvesting cotton in Southern states, this image was actually made of a migrant laborer in California.

The work of picking cotton occupies a chapter of John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath. Like other seasonal labor, it was a possibility for the Joad family, who had fled the dust bowl conditions of Oklahoma. In a conversational style, seemingly from the migrant picker's viewpoint, Steinbeck describes the process: "Now the bag is heavy, boost it along. Set your hips and tow it along, like a work horse. . . . Good crop here. Gets thin in low places, thin and stringy. Never seen no cotton like this here California cotton.""

#Stoop Labor in Cotton Field#San Joaquin Valley#California#20th century#1930s#1938#Dorothea Lange#photograph#photography#Getty museum

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

..."The goods these prisoners produce wind up in the supply chains of a dizzying array of products found in most American kitchens, from Frosted Flakes cereal and Ball Park hot dogs to Gold Medal flour, Coca-Cola and Riceland rice. They are on the shelves of virtually every supermarket in the country, including Kroger, Target, Aldi and Whole Foods. And some goods are exported, including to countries that have had products blocked from entering the U.S. for using forced or prison labor.

Many of the companies buying directly from prisons are violating their own policies against the use of such labor. But it’s completely legal, dating back largely to the need for labor to help rebuild the South’s shattered economy after the Civil War. Enshrined in the Constitution by the 13th Amendment, slavery and involuntary servitude are banned – except as punishment for a crime.

That clause is currently being challenged on the federal level, and efforts to remove similar language from state constitutions are expected to reach the ballot in about a dozen states this year.

Some prisoners work on the same plantation soil where slaves harvested cotton, tobacco and sugarcane more than 150 years ago, with some present-day images looking eerily similar to the past. In Louisiana, which has one of the country’s highest incarceration rates, men working on the “farm line” still stoop over crops stretching far into the distance.

Willie Ingram picked everything from cotton to okra during his 51 years in the state penitentiary, better known as Angola.

During his time in the fields, he was overseen by armed guards on horseback and recalled seeing men, working with little or no water, passing out in triple-digit heat. Some days, he said, workers would throw their tools in the air to protest, despite knowing the potential consequences.

“They’d come, maybe four in the truck, shields over their face, billy clubs, and they’d beat you right there in the field. They beat you, handcuff you and beat you again,” said Ingram, who received a life sentence after pleading guilty to a crime he said he didn’t commit. He was told he would serve 10 ½ years and avoid a possible death penalty, but it wasn’t until 2021 that a sympathetic judge finally released him. He was 73.

The number of people behind bars in the United States started to soar in the 1970s just as Ingram entered the system, disproportionately hitting people of color. Now, with about 2 million people locked up, U.S. prison labor from all sectors has morphed into a multibillion-dollar empire, extending far beyond the classic images of prisoners stamping license plates, working on road crews or battling wildfires.

Though almost every state has some kind of farming program, agriculture represents only a small fraction of the overall prison workforce. Still, an analysis of data amassed by the AP from correctional facilities nationwide traced nearly $200 million worth of sales of farmed goods and livestock to businesses over the past six years – a conservative figure that does not include tens of millions more in sales to state and government entities. Much of the data provided was incomplete, though it was clear that the biggest revenues came from sprawling operations in the South and leasing out prisoners to companies.

Corrections officials and other proponents note that not all work is forced and that prison jobs save taxpayers money. For example, in some cases, the food produced is served in prison kitchens or donated to those in need outside. They also say workers are learning skills that can be used when they’re released and given a sense of purpose, which could help ward off repeat offenses. In some places, it allows prisoners to also shave time off their sentences. And the jobs provide a way to repay a debt to society, they say.

While most critics don’t believe all jobs should be eliminated, they say incarcerated people should be paid fairly, treated humanely and that all work should be voluntary. Some note that even when people get specialized training, like firefighting, their criminal records can make it almost impossible to get hired on the outside.

“They are largely uncompensated, they are being forced to work, and it’s unsafe. They also aren’t learning skills that will help them when they are released,” said law professor Andrea Armstrong, an expert on prison labor at Loyola University New Orleans. “It raises the question of why we are still forcing people to work in the fields.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

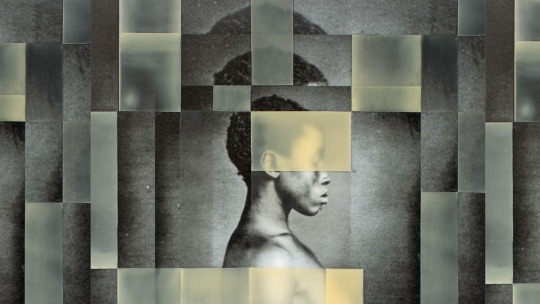

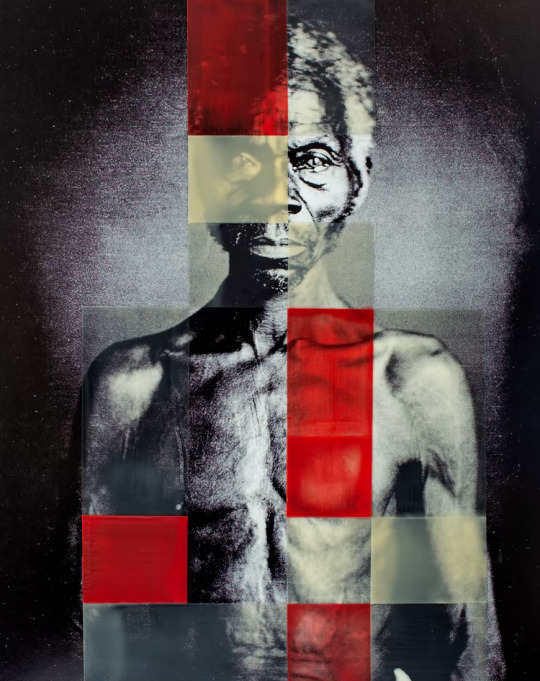

THE DARK UNDERSIDE OF REPRESENTATIONS OF SLAVERY

Will the Black body ever have the opportunity to rest in peace?

The photographs are about the size of a small hand. They’re wrapped in a leatherette case and framed in gold. From the background of one, the image of a Black woman’s body emerges. Her hair is plaited close to her head, and she is naked from the waist up. Her stare seems to penetrate the glass of the frame, peering into the eyes of the viewer. The paper label that accompanies her likeness reads: delia, country born of african parents, daughter of renty, congo. In another frame, her father stands before the camera, his collarbone prominent, and his temples peppered with gray and white hair. The label on his photo says: renty, congo, on plantation of b.f. taylor, columbia, s.c.

In 1850, when these images were captured, the subjects in the daguerreotypes were considered property. The bodies in the photographs had been shaped by hard labor on the grub plantation, where they’d spent their lives stooped over sandy soil, working approximately 1,200 acres of cotton and 200 of corn. Brought from the fields to a photography studio in Columbia, South Carolina, each person was photographed from different angles, in the hopes of finding photographic evidence of physical differences between the Black enslaved and the white masters who owned them. A daguerreotype took somewhere between three and 15 minutes of exposure time, and the end result was a detailed image imprinted on a small copper-plated sheet, covered with a thin coat of silver.

Louis Agassiz, a professor at Harvard, commissioned the portraits of Delia and Renty, along with those of other enslaved people, from the photographer Joseph T. Zealy. The daguerreotypes remained, all but forgotten, in the school’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology attic until an archivist found them in a storage drawer in 1976. Since then, these photos of Renty and his daughter Delia have been featured on conference programs, in presentations, and reproduced in books.

As photography has moved from the scientific novelty of Agassiz’s time to ubiquitous contemporary entertainment over the years, the art form has reflected society’s inequity. The rediscovery of the daguerreotypes and their use in revenue-generating materials in the present day have helped surface an ethical issue that has long accompanied images of Black people’s bodies: Their presentation and exploitation still, in many cases, outweigh individual ownership and autonomy.

While the provenance of the photos traces a line from a drawer at Harvard to a photographer in South Carolina, their story today also has roots in Norwich, Connecticut, home to Tamara Lanier, who claims to be the great-great-great-granddaughter of Renty. As a girl, Lanier’s mother told her about an ancestor named “Papa Renty.” She learned that he was a master of the Bible and that, as an act of defiance, he taught other enslaved people to read. According to the history passed down through her family, Renty got his hands on Noah Webster’s The Original Blue Back Speller, and after tending to crops in the fields, he would study the book at night.

Gillian B. White: Introducing the third chapter of “Inheritance”

Lanier would not start searching for the truth behind those stories until 2010, the year her mother died. She began a genealogical search for her ancestors. She also told an acquaintance, Richard Morrison, of her mother’s death and her own attempt at tracing her bloodline. Morrison, an amateur genealogist, took what Lanier told him and did some digging. He came up with a name: Renty Taylor. Morrison’s Ancestry.com search pulled up a photograph of Renty from 1850—one of Agassiz’s daguerreotypes. Further searches provided Lanier with information about Agassiz and Zealy and mentioned where she could find the original pictures: Harvard University. When she traveled to the school and viewed the images, Lanier was disappointed by their size, which resembled a deck of cards. There he was, the man who seemed larger than life in many of her mother’s stories, looking small and sad.

Seeing her ancestors in the archives at the university, Lanier felt the portraits were out of place. She believed that the images of Renty and Delia belonged to her. So on March 20, 2019, she filed a lawsuit against Harvard. In her lawsuit she alleges that the images of Renty and Delia are still working for the university, based on the licensing fees their images command. (In 2019, Harvard acknowledged that the images are not protected by copyright and that it charges only a $15 fee for a high-resolution scan.) Lanier requested that the university grant ownership of the daguerreotypes to her, pay her punitive damages, and turn over any profits associated with the portraits. “From slavery to where we are today, Black people’s property has been taken from them,” Lanier told me. “We are a disinherited people.”

Earlier this year, a court dismissed Lanier’s lawsuit, saying that “the law … does not confer a property interest to the subject of a photograph,” no matter the circumstances of its composition. Neither Harvard nor the judge presiding over the case disputed Lanier’s evidence that she was a direct descendant of Renty. Still, the court declared that Havard had the right to keep ownership of the photographs. Lanier has appealed the decision, and now the Massachusetts Supreme Court will weigh in. Oral arguments are scheduled for November 1.

Lanier’s case is about more than her personal interest in the photographs; rather, it has greater implications in a long-running reckoning. Agassiz used these photos of enslaved Africans, along with measurements of their cranium, as evidence of a theory known as polygenism, which was used by American proponents to justify slavery. He and other scientists believed Black people were created separately from white people, and their pseudoscientific inquiry was embedded into racist stereotypes in the bedrock of this country. To some historians, in keeping and curating images like these, Harvard is still celebrating the work of these practitioners and their discredited racial theories. (Harvard did not respond to requests for comment. In a previous statement, the university claimed the daguerreotypes were “powerful visual indictments of the horrific institution of slavery” and hoped the court ruling would make them “more accessible to a broader segment of the public.”)

The outcome of Lanier’s court case against Harvard will be legal commentary on whether the Black body ever has the opportunity to rest in peace, or whether present-day academic and entertainment priorities outweigh the rights of the Black deceased.

Whether she gets there or not depends on her long shot of an appeal. But her fight is an important front in a war over the ownership of images of Black bodies, one that is being waged on TikTok as well as in dusty archival drawers.

This technology spawns a series of questions: At a time when Black bodies are treated as teaching moments for the larger culture, are those whose bodies were broken—by the whip of an overseer or the bullet of a police officer—ever afforded the opportunity to rest in peace? This inquiry is the latest curious development in the ethically fraught conversation about Black bodies, ancestry, and ownership. There is a direct line between historical exploitation and the ongoing commercialization of and profiting from images of dead Black people, over which their descendants often have little control, few claims, and few rights.

America is still grappling with the limitations of freedom, and whether Renty and Delia will be released from the grips of the archives remains to be seen.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Former Farmworker on American Hypocrisy

In the pandemic, “illegal” workers are now deemed “essential” by the federal government.

By Alfredo Corchado

Mr. Corchado is the Mexico border correspondent for The Dallas Morning News.

May 6, 2020

ImageWorkers in Joe Del Bosque’s asparagus fields near Oro Loma, Calif., in April.

Workers in Joe Del Bosque’s asparagus fields near Oro Loma, Calif., in April.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

EL PASO — The other day, armed with a face mask, I was rushing through the aisles of an organic supermarket, sizing up the produce, squeezing the oranges and tomatoes, when a memory hit me.

Me — age 6 — stooping to pick these same fruits and vegetables in California’s San Joaquin Valley. I spent the spring weekends and scorching summers of my childhood in those fields, under the watchful eye of my parents. Once I was a teenager, I worked alongside them, my brothers and cousins, too, essential links in a supply chain that kept America fed, but always a step away from derision, detention and deportation.

Today, hundreds of thousands of immigrants from Mexico and Central America are doing that work. By the Department of Agriculture’s estimates, about half the country’s field hands — more than a million workers — are undocumented. Growers and labor contractors estimate that the real proportion is closer to 75 percent.

Suddenly, in the face of the coronavirus pandemic, these “illegal” workers have been deemed “essential” by the federal government.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

Tino, an undocumented worker from Oaxaca, Mexico, is hoeing asparagus on the same farm where my family once worked. He picks tomatoes in the summer and melons in the fall. He told me his employer has given him a letter — tucked inside his wallet, next to a picture of his family — assuring any who ask that he is “critical to the food supply chain.” The letter was sanctioned by the Department of Homeland Security, the same agency that has spent 17 years trying to deport him.

“I don’t feel this letter will stop la migra from deporting me,” Tino told me. “But it makes me feel I may have a chance in this country, even though Americans may change their minds tomorrow.”

Image

Farmworkers stacking and thinning the asparagus crop.

Farmworkers stacking and thinning the asparagus crop.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

True to form, America still wants it both ways. It wants to be fed. And it wants to demonize the undocumented immigrants who make that happen.

Recently, President Trump tweeted that he would “temporarily suspend immigration into the United States” — a threat consistent with the hit-the-immigrant-like-a-piñata policy he spearheaded in his 2016 campaign. Less than 24 hours later, the president backed down in the face of business groups fearful of losing access to foreign labor, announcing that he’d keep the guest worker program.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

In the past, the United States has rewarded immigrant soldiers who fought our wars with a path to citizenship. Today, the fields — along with the meatpacking plants, the delivery trucks and the grocery store shelves — are our front lines, and border security can’t be disconnected from food security.

It’s time to offer all essential workers a path to legalization.

It might seem hard to imagine this happening during the “Build the wall” presidency, when Congress can barely agree on emergency stimulus measures. Many Republicans no longer support even DACA, the program that protected Dreamers who grew up here and that could be revoked by the Supreme Court this week. But the pandemic scrambles our normal politics.

“We have started talking about essential workers as a category of superheroes,” said Andrew Selee, the president of the nonpartisan Migration Policy Institute and author of “Vanishing Frontiers.” If the pandemic continues for a year or two, he said, we should think “in a bold way about how do we deal with essential workers who have put their life on the line for all of us but who don’t have legal documents.”

Image

The author, far right, age 9, with his mother, Herlinda, and, from left, brothers Juan, Frank and Mario, from left.

The author, far right, age 9, with his mother, Herlinda, and, from left, brothers Juan, Frank and Mario, from left.

Maybe, he said, “they should be in the pipeline for fast-track regularization, just like those with DACA” are, for now.

Of course, America has always been a fickle country. I learned that lesson as a crop-picking boy, when my aunt Esperanza, who ran the team of farmhands that included my mom, brothers and cousins, would yell: “Haganse arco.” Duck!

The workers without documents would stop hoeing and scramble. Run — if not for their lives, then almost certainly for their livelihoods. We’d watch as the vans of the Border Patrol came to a screeching halt, dust settling. The unlucky workers would make a beeline for the nearest ditch or canal. Some would simply drop to the ground, hoping for refuge amid the rows of sugar beets, tomatoes or cotton. Sometimes the agents gave chase. We’d always root for the prey.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

On more than one occasion, agents took my mom and my aunt Teresa, locking them in the cages in the back of the van, because they didn’t have their green cards on them. We’d race home and fetch the cards and make a mad dash to the immigration offices in Fresno some 60 miles away from our farm camp in Oro Loma, praying we’d make it before they could be deported.

Image

Workers planting rows of cantaloupes near Oro Loma.

Workers planting rows of cantaloupes near Oro Loma. Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

We were desperate to prove they had every right to be out in those desolate fields, as if they were taking a dream job away from somebody else.

One time, Aunt Teresa looked genuinely disappointed at the sight of our smiling faces. She was ticked off she hadn’t been deported.

“I miss Mexico,” she said.

Sometimes, the night after such raids, a puzzling thing would take place. A labor contractor or farmer would drive up as we’d gather for dinner of beef, green chile and potato caldillo washed down with tortillas. He’d compliment us for the hard work we had put in that day. And then he’d ask: Did we know anyone who might want to come and work alongside us?

Image

Taking shelter during a lunch break.

Taking shelter during a lunch break.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

He meant more Mexicans.

The instructions were simple: Get the word out, spread the farmer’s plea back in our towns in Mexico because plenty of rain had fallen that winter and now it was summer and everything around us was ripe, aching for that human touch. The season looked promising. Plenty of crops to pick.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

Today not much has changed. The vulnerable — Dreamers working in health care; hotel maids; dairy and poultry plant workers; waiters, cooks and busboys in the $900 billion restaurant industry — still work to feed their families while feeling disposable, deportable by an ungrateful nation.

Tino, the farmworker in the San Joaquin Valley, is worried about the coronavirus. He wonders whether it’s best, after 17 years of hiding from immigration authorities, to return to Oaxaca, “where I’d rather die.”

But Tino’s dreams outweigh his fears. He wants the best for his family, including a son born in the United States, who’s looking at colleges in California. So, he continues in his $13.50-an-hour job.

Image

Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

Image

Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

He works for, among others, Joe L. Del Bosque of Del Bosque Farms, one of the largest organic melon growers in the country. Mr. Del Bosque employs about 300 people on hundreds of acres, and his fruits and vegetables are sold in just about every other organic supermarket across the country, including the place where I now shop in El Paso.

“Sadly, it’s taken a pandemic for Americans to realize that the food in their grocery stores, on their tables, is courtesy of mostly Mexican workers, the majority of them without documents,” Mr. Del Bosque told me. “They’re the most vulnerable of workers. They’re not hiding behind the pandemic waiting for a stimulus check.”

Image

Joe Del Bosque employs about 300 people on hundreds of acres.

Joe Del Bosque employs about 300 people on hundreds of acres.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

Image

Fresh organic asparagus from Del Bosque Farms.

Fresh organic asparagus from Del Bosque Farms.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

Along with other farmers, he has been pleading with Congress for the past few years to legalize farmworkers, if not as part of comprehensive immigration reform, then as a bill focused on farmworkers, because “you need these workers today, tomorrow and for a long time.”

“With or without Covid,” he added, “we need to constantly replenish our work force to ensure food supplies.”

Some Democratic lawmakers, including Representative Veronica Escobar of El Paso, are pushing to include legalization in any updated coronavirus relief package. “The hypocrisy within America is that we want the fruits of their undocumented labor, but we want to give them nothing in return,” she said.

Even with unemployment projected to be 15 percent or higher, Mr. Del Bosque told me he doubts he’ll ever see a line of job-seeking Americans flocking to his fields. The rare few who have shown up at 5:30 a.m. don’t come back. Some, he said, give up the backbreaking work before their first lunch break.

He fears looming labor shortages. That’s not because of raids by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement resuming or a wall keeping workers out. He worries about a potential coronavirus outbreak, yes, but his most immediate concern is that his farmworkers are aging. Their average age is 40. My old school, Oro Loma Elementary School, which was once filled with Mexican children, closed down in 2010.

Image

The author at Oro Loma Elementary School.

The author at Oro Loma Elementary School.

The fields are simply running out of Mexicans as fewer men and women migrate each year, either because they’re finding better jobs in Mexico or because of demographics. The Mexican birthrate is down from 7.3 children per woman in the 1960s to 2.1 in 2018. Those who do come want higher-paying jobs in other industries.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

The best way to guarantee food security in the future is to legalize the current workers in order to keep them here, and to offer a pathway to legalization as an incentive for new agricultural workers to come. These people will be drawn not just from Mexico, but increasingly from Central and South America.

Image

Mr. Del Bosque’s farm has relied on Mexican workers since the 1950s.

Mr. Del Bosque’s farm has relied on Mexican workers since the 1950s.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

Del Bosque Farms have been dependent on Mexican workers since Mr. Del Bosque’s parents, also immigrants from Mexico, started hiring them in the 1950s under the Bracero Program, which began during World War II. The program issued some five million contracts to Mexicans, inviting them to come to the United States as guest workers to help fill labor shortages so Americans could fight overseas.

Hundreds of the workers who’ve toiled at Del Bosque Farms over the years have become legal residents, many more citizens, including my father, Juan Pablo.

For many years my father spent the springs and summers working in the United States, but every November he’d high-tail it back to his village in Mexico, where he played in a band called the Birds with his five brothers. He didn’t trust his American bosses to raise his pay, and always worried about the possibility of suddenly being deported, so he wouldn’t commit to them. The Texans especially, he thought, were prejudiced against Mexicans.

The boys from Mexico worked so hard, Texas ranchers argued during one of America’s cyclical anti-immigrant periods, that the hiring of Mexicans should not be considered a felony. Thus, the Texas Proviso was adopted in 1952, stating that employing unauthorized workers would not constitute “harboring or concealing��� them. This helps explain why Americans call immigrants “illegal” but not the businesses that hire them.

ADVERTISEMENT

Continue reading the main story

When the Bracero Program ended in 1964, amid accusations of mistreatment against Mexicans, my father thought he had enough of plowing rows on a tractor and digging ditches. He dreamed of running a grocery store in Mexico, raising his kids out where mountains embraced us. But he was such a hard worker that his boss couldn’t fathom the idea of losing him. So he helped my father get a green card for every member of his family, including me. Later he began working for the Del Bosques.

Without legalization, he would have left and probably never come back.

Image

During the pandemic, undocumented immigrant farmworkers in California are deemed essential.

During the pandemic, undocumented immigrant farmworkers in California are deemed essential.Credit...Max Whittaker for The New York Times

As a 6-year-old immigrant, I’d cry at night under the California stars, homesick for Mexico, for my friends and cousins. Then one night, as my mother tucked me into bed, she caressed my face. “Shhhh,” she whispered, “they’re all here now.” And she was right.

Today my siblings include a lawyer, an accountant, two truck drivers, a security guard, an educator and a prosthetics specialist. Cousins went off to fight wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, or to help run medical centers and corporations, including Walmart in Arkansas. Others still grind away in the fields of California and meatpacking plants of Colorado, work in nursing homes or clean the houses of the rich. Many of us make an annual pilgrimage to our home village in the Mexican desert. But we’re firmly planted here.

Without being thanked for it, we’re replenishing America.

Alfredo Corchado is the Mexico border correspondent for The Dallas Morning News and the author of “Midnight in Mexico" and “Homelands: Four Friends, Two Countries and the Fate of the Great Mexican-American Migration.”

0 notes

Text

Traditional Dresses as Resistance – The New York Times

The Look

Rarámuri women in Chihuahua, Mexico, have made an indigenous style of dress a means of fighting assimilation.

By midmorning on the Wednesday before Easter, the desert sun was gaining strength in Chihuahua, Mexico. So was the deep sound of beating cowhide drums in Oasis. This settlement, situated in the working-class neighborhood of Colonia Martín López, is home to approximately 500 Rarámuris, commonly known as Tarahumaras, an indigenous people who are fleeing drought, deforestation and drug growers in Sierra Madre.

In the city, their displacement is marked by other forms of hardship, which are magnified by the way the Rarámuri stand out.

The women dress in bright, ankle-length frocks — and often spend afternoons sewing traditional Rarámuri dresses — despite pressures from the people of mixed race who comprise most of Mexico’s population to assimilate with Western style. For Rarámuri people, assimilation is the same as erasure. But there’s a pervasive idea among many in Mexico that progress is dependent on severing ties with the country’s indigenous history.

Yulissa Ramírez, 18, wants to challenge that notion. She plans to attend nursing school after she graduates from high school, where the customary uniform is white scrubs, but hopes the program will allow her to wear a traditional white Rarámuri dress. “Our blood runs Rarámuri, and there’s no reason that we should feel ashamed,” Ms. Ramírez said, speaking in Spanish, as she held her infant son.

Her mother, María Refugio Ramírez, 43, sews each of her dresses by hand, following a dressmaking tradition that dates back to the 1500s, when Spain invaded the Sierra Madre mountains. Throughout the 1600s, Jesuit priests compelled Rarámuri women to wear dresses that fully covered their bodies. Over time, Rarámuri women adopted the cotton fabrics brought over by the Spaniards and made the dresses their own by adding triangle designs and colorful borders. Today they continue to hand-sew the bright floral garments, which stand out when the women venture beyond the Chihuahua state-funded settlement and into the urban landscape of gray concrete buildings and throngs of people in bluejeans.

Their unwillingness to conform with contemporary style has, at times, come at the cost of economic advancement. But some women seek to challenge that notion. Ms. Ramírez, for example, believes that completing her nursing program in traditional dress will be an important statement that Rarámuri people are a vital part of Mexico’s future — and present.

Other Rarámuris are monetizing their craft. For example, Esperanza Moreno, 44, embroiders tortilla warmers, aprons and dish cloths with depictions of Rarámuri women in traditional garb, and sells them to Mexican nonprofits who then resell the items to shops and Walmarts throughout the country. Rarámuri women have begun sewing traditional dresses to sell, as well.

On Holy Thursday, Ms. Moreno had taken the day off from the workshop outside the settlement where she sews modern-day garments that incorporate Rarámuri designs. The job provides a steady income for Ms. Moreno, whose husband is a contractor whose jobs often take him outside Chihuahua. It’s a line of work that has led to the kidnappings of some Rarámuri men; in vehicles that look like work-site shuttles, they have been taken instead to labor in marijuana and poppy fields, sometimes for entire seasons, leaving their families concerned for their safety and often without a source of income.

Ms. Moreno sat on her front stoop playing with her 1-year-old granddaughter, Yasmín, who took a few unsteady steps before turning to smile at her grandmother. She began sewing dresses for Yasmín soon after she was born. It’s important, she said, to pass along the dressmaking tradition to new generations of women. “We want to be seen as Rarámuri,” Ms. Moreno said.

Craft-making and her current job in the workshop are a means for Ms. Moreno to provide her family with the income necessary not only to buy food and pay utilities, but to uphold Rarámuri traditions. Fabric and sewing supplies for a Rarámuri dress can cost upward of 400 pesos, more than some families earn in a month.

There are efforts within the community to help Rarámuri women achieve a sustainable income while keeping their dressmaking tradition alive. In 2015, Paula Holguin, 46, with the support of the state government, began training 30 Rarámuri women to work on sewing machines in a large, spacious workshop inside Oasis. The state government had recently completed construction of the space — a project that aims to give Rarámuri women a chance to earn a living creating commissioned garments.

While Rarámuri men discard their traditional shirt, cloth and sandals upon arrival to the city in order to obtain jobs in construction, Rarámuri women rarely trade their dresses for the uniforms required by employers. “I only wear Rarámuri dresses,” Ms. Holguin said, echoing the thousands of Rarámuri women who strive to keep not only their dress, but their people’s ways of caring for the natural world and one another. To supplement the men’s income, Rarámuri women sell crafts and ask people on the street for “korima” — their word for reciprocity — at busy intersections throughout Chihuahua. But they earn little money this way, and expose themselves and their children to heavy traffic, insults and threats.

Ms. Holguin runs her own sewing workshop, or taller de costura, where she hopes to attract enough clients so that each Rarámuri seamstress can earn money in a safe work space, without sacrificing her traditional dress and time with her children.

Ms. Holguin used to take her daughters to sell crafts, candy, or ask for “korima” on the streets of Chihuahua. “Sometimes I was treated badly,” Ms. Holguin said. “Not everyone is a good person.” An avid runner, as so many Rarámuri are, she displays in her kitchen a dozen medals won in marathons held in the Sierra. (She runs in traditional dress, as well.) Her conviction that Rarámuri women should be proud of their heritage drives her to petition the government for support and rally the women around this new business venture.

But gathering clients has proved to be a challenge. A large project, like the request for 2,000 bedsheets from a nearby hospital, kept the women busy for months at a time. Long spells with little or no work often follow. Low pay, too, keeps women working in the busy city streets. “If there’s work in the workshop, the women don’t go to the street. They sell on the street if they don’t have work,” said Ms. Holguin.

Still, Ms. Holguin was hopeful that the workshop would provide Rarámuri women with the opportunity to attain visibility as seamstresses with varied skills. She travels frequently to Mexico City to speak at government forums about the workshop and the importance of Rarámuri culture.

In 2018, when president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador was visiting Chihuahua to meet with state officials, Ms. Holguin and a small group of Rarámuri women and government officials greeted him on the streets with calls of “AMLO, support Rarámuri seamstresses.” Mr. López Obrador, who was promising to uphold indigenous rights as part of his presidency, ignored throngs of reporters to speak to Ms. Holguin and a few other Rarámuri women about their employment of Rarámuri women as seamstresses. In the end, though, government officials in high offices did not offer the support that Ms. Holguin hoped for. “No one helped us, not the president or the governor. Only clients have helped us,” Ms. Holguin said. She also credits Rarámuri women and the local officials who have supported the workshop. “Together we have lifted up this workshop,” she said.

In the face of historical violence, assimilation might appear to be a path toward economic progress, protection and safety. But to the Rarámuri women, making and wearing traditional dresses is nonnegotiable. Even Rarámuri women brought up under the influence of Chihuahua’s urban culture, and who mix elements of Western dress like metal hoops and plastic necklaces, continue to wear traditional dresses for daily living and special occasions. The dresses are not only a marker of Rarámuri identity, but protest.

“This is how we were born, and this is the way our fathers and mothers dressed us,” Ms. Holguin said. “We haven’t lost our traditions.”

Sahred From Source link Fashion and Style

from WordPress http://bit.ly/2YNnIlW via IFTTT

0 notes