#The Gothic Script of the Middle Ages

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Typography Tuesday

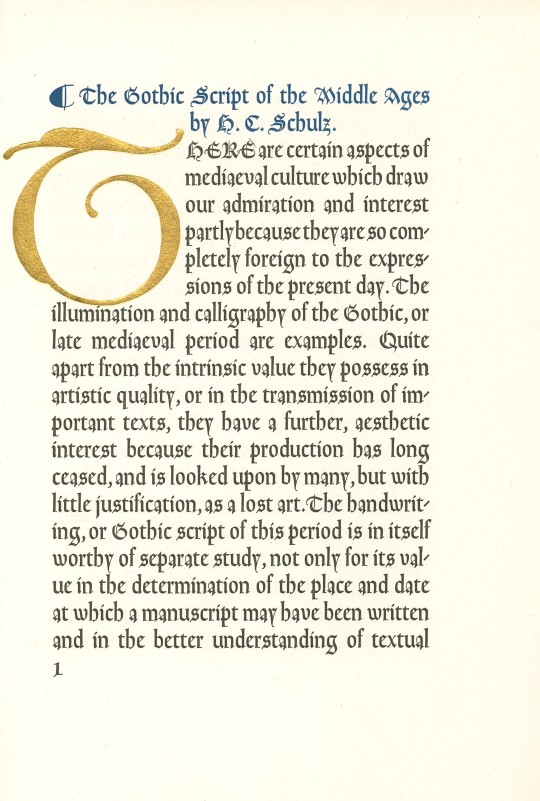

This week, a little bit of Gothic with The Gothic Script of the Middle Ages by H. C. Schulz, printed in San Francisco by the Grabhorn Press in an edition of 71 copies for the publisher and first bibliographer of the Grabhorn Press David Magee in 1939. The type used is Fred Goudy's Deepdene Text, a blackletter typeface designed in the early 1930s to complement his humanist Deepdene typeface designed earlier. The two typefaces are not otherwise related in style. The book is printed in red, black, and blue, with a lovely gold-leaf initial T in the opening text.

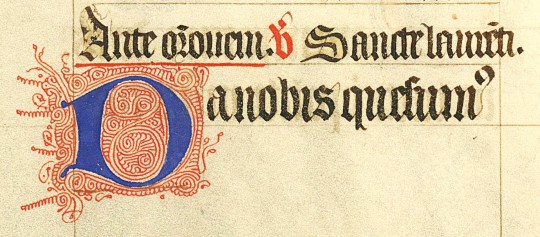

This volume is a "leaf book": a book with content centered on the content of another book, or type of book, with a sample leaf from that other book included in the volume. In this case, a leaf from a late 14th-century manuscript Collectar is included in the publication. We don't know who H. C. Schulz is, but judging from the several other leaf books he produced with the Grabhorn Press, he must have been a collector and authority on manuscript books. Unfortunately, he also seems to have been a breaker of books, or at best a collector of broken books, which in turn encourages the breaking of books.

Schulz describes the leaf included here as made "probably in Northern France" and that "The writing is a very bold Gothic script in the best liturgical tradition, and a contrast to its heaviness is given by the fine pen ornamentation of the initials." Our copy of The Gothic Script of the Middle Ages is part of a gift from the estate of our dear friend Dennis Bayuzick.

View other books from the collection of Dennis Bayuzick.

View our other Typography Tuesday posts.

#Typography Tuesday#typetuesday#Gothic script#Gothic type#The Gothic Script of the Middle Ages#H. C. Schulz#Grabhorn Press#David Magee#Frederic Goudy#Deepdene Text#manuscripts#medieval manuscripts#illuminated manuscripts#collectar#illuminated initials#leaf books#Dennis Bayuzick

72 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nigel's Book Details: Spread Four

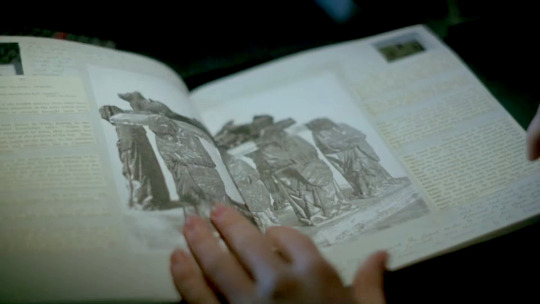

Using the order in which each spread is presented in the scene where Alex finally reads through Nigel's book, this is the fourth spread.

Text

Sadly, this is yet another spread wherein the text excerpts and the handwritten notes remain illegible even with sharpening/image filtering.

Central Image: Tomb of Philippe Pot

This spread is dominated by one large image across both pages. Despite the awkward angle and distortion from running across the gutter between pages, it was actually fairly easy to identify this image with the right search terms.

This is an old photograph of the tomb of Philippe Pot, a funerary monument currently housed in the Louvre. It was commissioned around 1480 by Philippe, some 13 years before his death. It represents the Burgundian style popular at the time, with 8 mourners serving as pallbearers holding up an effigy of Philippe, carved from limestone and painted and gilded.

Philippe Pot

Philippe was a scholar and bibliophile, raised at the court of the Dukes of Burgundy, a powerful political state at the time. He was made a knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece, a chivalric order founded by Duke Philip the Good. This honor was stripped from him when he defected to serve King Louis XI of France, later brokering a truce between the two warring states, and he was appointed seneschal of Burgundy by King Louis.

The Monument

Philippe was buried at Citeaux Abbey, in the chapel of Saint-Jean-Baptiste. During the French Revolution, all church property was claimed by the state, and it was first relocated to another abbey and then purchased by a private owner to decorate his garden. It was moved and sold a few more times before being acquired by the Louvre in 1889. It was cleaned and restored a few times after this photograph was taken, and its current appearance can be seen below.

The mourners, called "pleurants", each bear a painted and gilded heraldic shield that refers to specific members of Pot's lineage, indicating the monument is of the "kinship tomb" type. The four shields on the left represent the heraldries of Guillaume III Pot (d. c. 1390) and Raguenonde Guénant, the Cortiambles family, the Anguissola family, and the de Blaisy family. Those on the left represent the de Montagus and de Nesles, and two unidentified families.

The Gothic script inscriptions around the edges of the platform recount the deeds of Philippe and explain his reasons for switching sides.

The animal at the feet of the effigy was poorly restored by prior generations resulting in loss of some detail. Historians disagree on whether it was meant to represent a lion or a dog but many see it as a dog, a popular symbol of loyalty in Burgundian tomb art.

I think I'll call him Luther.

Further reading: The Order of the Golden Fleece

Another organization founded in the late Middle Ages, but not a monastic order like the Templars. This order still exists today in two separate branches. The Spanish order has become an order of merit of the state, while the Austrian order has remained a Catholic chivalric order and is recognised even by the Republic of Austria as an international legal entity. Considered to be a highly prestigious honor even today.

My research has dredged up no particular historical association between this order and anything involving Templars or Freemasons other than the mere fact that both the Templars and the Golden Fleece were knightly organizations. I also find no connection between Philippe Pot and the Templars. Based on that, I think the photo of this tomb was included purely for the aesthetics--the medieval character, the heraldic shields, the effigy of a knight are all meant to evoke the idea of Templars without actually being tied to them.

[Nigel's Book Details: Spread One] [Nigel's Book Details: Spread Two] [Like Minds Masterpost]

#due to difficulty identifying some images i am choosing to proceed with the spreads I CAN do rather than#try to complete each spread in order#basically: spread 3 is giving me fits so we're moving on for now#like minds#nigel colbie#alex forbes#tom sturridge#murderous intent#like minds 2006#like minds analysis#like minds annotations

33 notes

·

View notes

Note

Waittttt why don’t you like the nosefertu movie 🥺🥺

I didn't, anon, no, sorry! I've been trying to be relatively discrete about it, because I know people on here really love it, and I don't actually like harshing anyone's buzz, but it wasn't even a case of it just not being for me, I actually didn't think it was very good.

My issues of it are kind of two-fold, one is with the writing, and the second is more specifically tied to the visual language of the film, and probably more about me really being a cinephile with a particular interest in gothic / gothic-adjacent cinema, haha. I'll put this under a cut in case people would like to scroll past, but also because there are quite a lot of screenshots in the second bit.

My main issue with the writing is that it was a) heavily, heavily expositional, and b) I don't think it had anything new to say about these characters, which is a huge issue when you're looking at the fourth adaptation of this specific story, which in turn is a part of more than 80 Dracula adaptations.

In terms of the exposition, that was frustrating alone with the world building and the period setting, but I'm overall pretty forgiving of that in films like this. What I had a really big issue with was that the script never let us in to any of these relationships. We were told what they were by the characters. There was no authentic intimacy in any of the dynamics, everything that we were supposed to feel about their relationships we were told to feel, not invited to feel.

Ellen and Anna's friendship for instance is positioned as one of the hearts of the film, but we get no context as to their friendship, we are offered no scenes of close intimacy beyond the one in bed later in the film, which feels like too little too late to me. The fact that their friendship is a point of friction in Anna's marriage with Friedrich is also dropped in randomly halfway through the film to spearhead middle act tension, but that doesn't really match the tone of the dynamics as we see them in the first half of the film where he seems to want to look after Ellen as much as Anna does.

I've actually found this with a lot of Eggers scripts - and for the record, I think he is a better director than he is a writer - where he is just fundamentally disinterested in the backgrounds and interpersonal dynamics of his characters. He likes relationships as far as they service the plot and the aesthetic that he's trying to achieve, and deepening them beyond that is just not something he does. It might work for some people, but it actually leaves me really cold as a viewer. I need to know more to feel more, I need to be shown the stakes, instead of told them, I don't get anything out of the film by it telling me that Ellen and Anna are friends, just like I don't get all that much out of it telling me that Ellen and Thomas are in love, which it does, repeatedly, without ever investing in why they are in love. I need to know that why to be emotionally invested, and I just don't think that's there.

Which kind of filters a bit back to this question of why Eggers wanted to remake this. There are excellent versions of it already that tell deeper stories of coming of age, sexually and emotionally, trauma, and female sacrifice, so what did he want to bring to it? More explicit sexuality? Modern effects? That's not enough for me. I think adaptations and remakes have to have something to say - Interview with the Vampire certainly does - and when they don't, they just feel hollow to me, which this film did.

And this goes to my second point too, because a lot of this film felt like it owed a lot visually to better films to me. Again, I do think Eggers is a good director - he manages tone really well, and I think his visual sensibility is compelling (although not as compelling as others, I have to say), but I also think his eye is so heavily influenced by others sometimes that he veers out of homage and into straight up lifting shots.

And I'll give him a pass on some of it, right? Him adapting shots from the 1922 and 1979 films are a part of being in conversation with them, y'know? I don't actually have a problem with him recreating those, and he recreates heaps. I won't repost all of them, but The Frida Cinema did a great compilation of them on Instagram here if you're interested. Here are a few though:

(Interestingly, I actually think his versions are the least innovative in almost all cases too - I often find Eggers movies to be really flat visually - but I'm not going to get into that).

What I have more of an issue with is that I think that a lot of his shots are taken from other films too. Let me show you some examples.

Let's start with that beautiful curtain shot, and then let's have a look at one from the wonderful Jane Campion film, Bright Star (2009), and finally Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970).

The last one is a little different, of course, but I did want to include it because that is literally a Nosferatu-esque monstrous vampire coming through the curtain, and also I think Eggers took a lot of inspiration from that particular film.

Okay another one. Let's look at Ellen in her white night gown, running out the door, and then lets have a look at two other iconic gothic films - The Uninvited (1944) and Eyes without a Face (1960).

Another one! Ellen ripping off her dress, then lets have a look at a shot from famed British arthouse filmmaker, Derek Jarman's The Last of England (1987)

This one feels obvious, but of course the eyes rolling back screaming shot is obviously heavily reminiscent of The Exorcist (1973).

This shot of Ellen, with this shot from The Piano (1993) which I would've maybe talked myself out of if I didn't immediately Google and find out Eggers listed The Piano as one of his favourite films on the Nosferatu press tour (taste! Now THAT'S a movie!).

And this is a promo shot because I couldn't find the still from the film itself, but again, Ellen with Orlock, and Valerie with the Monster in Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970)

Like I mentioned, I do think he took quite a lot from Valerie and Her Week of Wonders generally which is a dreamy, gothic, erotic horror featuring vampires that was released as a part of the Czechoslovak New Wave in 1970. It's not super easy to capture in screenshots, but there are elements to the tone and the way that he structures the story that feel heavily influenced, and even involves sex with the unseen supernatural outside. These shots don't look that similar, but trust me, it's basically the same thing happening in both (and again, I think Jires' shot is a lot more compelling).

I could honestly probably list a lot more, because I know while I was watching it, I recognised shots from The Innocents (1961) [a lot of the window shots felt very heavily tied to this one], My Cousin Rachel (1952), Night of the Hunter (1955), The Spiral Staircase (1946) and Viy (1960). That's not a criticism necessarily, but it goes back to my point that I just don't think Eggers had much to say in this particular film. He wanted an aesthetic and a vibe which he obviously saw and loved in other films, but without having anything to say, or a deeper understanding of these characters, I think it stifled his own creativity which let the film down on both a writing level and a visual level.

It was like watching a collage of a bunch of things he liked, and I get it, I mean, I like those things too, I think we have similar taste in movies, haha, but without a good script to drive this film forwards, or meaningful engagement of these characters - - like I said, it just left me really cold.

#sorry this got a little long haha#film asks#i do respect that between bright star and the piano he's obviously a jane campion stan#but also lifting shots from women directors...#anyway everyone should watch bright star because it's probably a top ten movie for me#also the piano#also any of the other films i listed here haha

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Their task was to circumvent Sauron: to bring help to the few tribes of Men that had rebelled from Melkor-worship, to stir up rebellion. . .and after his first fall to search out his hiding (in which they failed) and to cause [?dissension and disarray] among the dark East. . .They must have had very great influence on the history of the Second Age and Third Age in weakening and disarraying the forces of East. . .who would both in the Second Age and Third Age otherwise have. . .outnumbered the West." - J.R.R. Tolkien, The Peoples of Middle-earth, "Last Writings"

@ainurweek day 5 ⇢ THE BLUE WIZARDS

[ID: an edit comprised of four posters in teal, grey-blue, and shades of brown. All have a beige background.

1: A small rectangular image of Joel Adama Gueye, a middle-eaged italian-senegalese model with light brown skin and dark, tightly curled hair pulled back and decorated with small metal pieces. He is looking up and to the left with a serious expression, and wears a large silver necklace. A blue piece of cloth unfolds behind him. The upper right corner of the image is framed with a layered teal and blue decoration, and text in the bottom left corner reads "alatar," with the first letter larger and in a teal gothic font with a brown shadow, while the rest is just teal and in a cursive script / 2: A rectangular image extending from the top right corner of the poster almost to the left. It shows blueish mountains wreathed in clouds and extending down to water. Teal text in a frame of the same color, partially layered over the image, reads "alatar" in the same format as Image 1, and below it, "also called Rómestámo, or east-helper, and Haimenar, meaning one who fares far, was a Maia of Oromë before undertaking the journey to Middle Earth as one of the five Istari. He strove valiantly to bring succor to the peoples of the East and frustrate the encroaching power of Mordor." The same decoration as in Image 1 is on the lower right corner of the frame / 3: Same format as Image 2, but reversed. This time, the image shows a street of blue buildings in a traditional north african style, and the large text reads "Pallando," and below it, "also called Morinehtar, or darkness-slayer, and Palacendo, meaning far-sighted one, was sworn to the service of Nessa. They traveled to Middle Earth at the behest of their friend and companion Alatar, and alongside the armies of the East proved themself a great warrior." / 4: Same format as Image 1, but the central picture shows Dua Saleh, a young sudanese person with dark skin and braided black hair. They are looking down and to the right, and wearing a white collared shirt and a silver piece of jewelry that extends across their face, as well as silver caps on their ears. Text reads "pallando" //End ID]

#ainurweek#ainurweek2024#alatar#pallando#the blue wizards#the silmarillion#mepoc#istari#maiar#silmedit#tolkienedit#oneringnet#tolkiensource#sourcetolkien#fantasyedit#litedit#brought to you by me#edits with the wild hunt#posters#described#fc: joel adama gueye#fc: dua saleh#i love you blue/teal + brown... i love you...

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Okay, so more cogent thoughts on Nosferatu (2024):

It was a very middling movie in everything except the costuming, set design, and art direction — which were top notch. I also give it props for the great lighting, i.e. being one of the few movies set mostly in the night where you can actually see what's going on. Eggers and Blaschke really used light and shadow extremely well in a few scenes, thinking here in particular of that one shot of Ellen (i.e. Lily Rose Depp) on the bed with the side profile of her shadow on the pillow and that ending shot of Von Franz (i.e. Willem Dafoe) illuminated in the mirror that were genuinely such beautiful, artistic frames. Visually, great movie. But visuals can't make up for a script and a cast that were stilted as all hell.

First of all, the screenplay itself was trying way too hard. No one spoke in a particularly convincing way — everything was long monologues, diatribes really, that were meant to be ominous and add to the gothic atmosphere. But it was pure narration, nothing left to the actual interpretation of the other storytelling elements to convey horror. Instead of letting the atmosphere carry the mood, it relied so much on telling us "btw this is the horrifying thing happening, this is why it is horrifying" and genuinely felt like they didn't think people would understand...what was essentially a very basic story. Where tf is the dude that wrote The Lighthouse??? This cannot be the same man.

Second, the acting. Or the lack of acting!!! At least on the part of Lily Rose Depp. This woman cannot act, I'm sorry. The people who praise her for this role, I'm asking: did we see the same movie? This woman cannot modulate her voice beyond two slightly differentiated tones, and same goes for her facial expressions. Dead delivery for a floundering script, and considering she was most of the movie, made for an incredibly boring 2 hours. I will say, she did some great body acting but that's probably the only thing she did with any sort of panache. The rest felt too committed to showing her off in the sexiest waif girl light that it could, rather than actually making use of her as an actress.

She and her castmates had no chemistry either, especially between her and Nicholas Hoult and Bill Skarsgard. I'm supposed to believe this woman's husband would traverse the snowy mountains of Transylvania with nothing but a coat and a horse to get back to her after THE most sexless kisses??? I'm supposed to believe that Nosferatu was enticed by her "passion" and her dead-eyed impression of romance???

Speaking of sex scenes, there were a few in the movie that were just so bad. Lily Rose Depp making the same pornhub "uh uh uh" moans during ALL of these scenes, with little change in delivery or intonation. And I do mean "uh uh uh," it was embarrassingly bad and not just because the sex itself was badly simulated by her partners.

And then there's Nosferatu himself. What a disappointment. I wanted something grotesque, I wanted something fun. We kept getting teased about Bill Skarsgard's "horrific transformation" but like. It was a bald cap and a coat. It was a prosthetic nose. The most grotesque thing about him was being...emaciated? Slightly deformed? Kinda middle aged looking? I don't know that we saw enough of him to really be able to judge his acting on this particular film, but imo he did a better job as Pennywise than in this role. It was just the most mid monster one could potentially want to fuck, unbelievably mid.

The "gore" people kept warning about was very very light, very standard for a horror movie and not even the most grotesque in recent memory (First Omen still had this beat by a long long long shot in terms of actual grotesquerie). Some frontal nudity that was nothing to write home about. But at least there were 2,000 rats. At least we had that.

2.5/5 stars

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

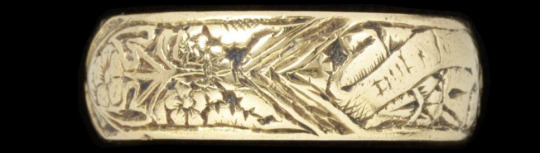

Poesy rings - Also spelled posie or posey, these rings derived their name from the French word “poésie,” or poem, because of the short sayings with which they were engraved that were religious, friendly or amorous in nature. Posy rings were popular from the latter half of the Middle Ages, which extended from the 15th to 17th century. In medieval times, when religion was very much a part of everyday life, it was common for saints’ figures or religious text to appear on the rings alongside romantic expressions or even expressions of friendship. In this way, the rings functioned both as a religious talisman and a gift of love. The phrases were written in Latin, Old French or Old English. Until about 1350, the lettering was done in a script with rounded capital letters known as Lombardic, while later examples use Gothic script. Certain inscriptions appear on multiple rings, indicating the goldsmiths of the day had a book of stock phrases from which clients could choose.

Phrases:

‘A Frindes gift’

‘A loving wife during life’

‘A true friends Gift’

‘A vertuous wife preseurueth life’

‘After consent ever content’

‘x AMICVS x TVVS’ ‘I love you.”

‘As God decreed soe wee agreed’

‘ As gold is pure, so love is sure’

‘AS I DESERVE SO I DESIER’

‘As I prove I wish your love’

AXCEPT * THIS * GIFT

‘Be true in Harte’

‘Bee firme in faith’

‘ CERT A MON GRE ‘ (certainly my choice)

‘Content is a treasure’

‘Continew Faythfull’

‘Denial is Death’

‘EN BON’

‘EN BON DESIR’

‘EN MI MARIE’ (to my husband)

‘Far of yet not forgot’

‘Feare god love thy choyse’

‘Feare not mee, i’le faithful bee’

‘God above increase our love’

‘God made us two one’

‘God send me always of his grace’

‘Harbor the harmless hart’

‘Harts United Live Contented’

‘Humility is the true Nobility’

‘I am free for God & Thee’

‘I cannot show the love I O’

‘I give it the to think on mee’

‘ I have obtained whome god ordained ‘

“I joy in one yet enjoy none”

‘I x LIKE x MI x CHOYSE’

‘I LIKE MY CHOIES ONLY’

‘I live in Hope’

‘I love and like my choice’

‘I rejoyce in the my choice’

‘I with your pretty sight, will breed you much delight’

‘In Christ and thee my comfort be’

‘In love abide till death devide’

‘In loyalty Ile live and dye’

‘In thy breast my heart doth rest’

‘In thee I find content of mind’

‘In thee my choyce I doe reioyce’

‘In thy sight is my delight’

‘Knit in one by Christ alone ‘

‘Let the Lord above send peace & love’

‘Let this present my good intent’

‘Let love continue’

‘Let us share in joy and care’

‘Let vertue rule affection’

‘Let vertue still direct thy will’

‘Let virtue be a guid to thee * ‘

‘Live & Love’

‘Live and Love Happy’

‘Live in Love & feare the lord above’

‘ Love I Like Thee + Sweete Requite Thee’

‘Love is my joy’

‘Love is the bond of peace’

‘love never dies where vertu lies’

‘Loue to be louved’

‘Love till you dye and soe will I’

‘Love vertu’

‘Moe love to Myne’ More love to Mine’

‘My gift is myselfe’

‘my hart is thine’

‘My Heart I Bind Where Love I Find’

‘My love by this presented is‘

My love to thee shall endless be

‘NE MEUR BON’ followed by a heart rebus (A good heart never dies)

‘No gift like good will’

‘No riches like content’

‘Noe Heart More true than mine to you.’

‘Noe recompence but love’

‘None Can Preuent the Lord’s Intent’

‘Not loft but gon before.’

‘Not so able as willing’

‘Not the value but my love’

‘Of earthli joyse thou art my choys’

‘Oh hurt noty [heart pictogram] whose only joy thou art’

‘One chosen both happy’

‘Rather dye then faith denye’

‘Remember the giver’

‘Sith hands and hart with one Consent let nought but death the Knot preuent’

‘Some love in earnest, some in jest, I love her that I like best’

‘Success to our fleet.’

‘The god of peace our love increase’

‘* THE HART SAW * THE LOVE CHOSEN * * NEVER BROKEN * JOYND ETERNAL *’

‘The Lord us Bless with Good Success’

‘The loue is trew that I O U’

‘The Love of thee is life to me’

‘The ring is round & hath no end so is my love for thy’

“Thinke it not strange though wee exchaing”

‘True love is endless’

‘True love will not remove’

‘TRYFULL+NOT+WYTH+THE+TRUSTY++’

‘UBI AMOR IBI FIDES’ Where There is Love There is Faith’

‘United hearts death only parts’

‘Vertue paseth ryches’

‘Wee joine our harts in God’

‘Wee joyne our love in God above’

‘When this you se remember me’

‘Yield and Conquer’

‘You and I will Lovers dye’

‘You have my hart’

‘You never knew a heart more true ‘

‘YOURS TO COMMAND.’

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

13 books meme

@introvertia tagged me in this (thank you, lovely, you're such a positive influence on my reading consistency <3) So let's talk books!

1) The Last book I read:

The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell. Absolutely destroyed me—90's science fiction, examining the paradoxes of faith and the difficulties of cross-culture exploration, seasoned with a hefty dose of grief and frustrated desire. Might as well have been written for me.

2) A book I recommend:

The Wicked & The Divine, by Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie. A sprawling examination of the celebrity-industrial complex, cultural and individual objectification, and the dark side of fandom culture. Well worth reading through in its entirety.

3) A book that I couldn’t put down:

Starling House, by Alix E. Harrow. I'm a sucker for a fierce and driven heroine who makes things happen by sheer force of will, despite the odds being against her. Between that and the deliciously spooky atmosphere, I adored this book.

4) A book I’ve read twice (or more):

<i>Good Omens</i>, by Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett. Hardly an original answer on this website, but it's a classic for a reason <3

5) A book on my TBR:

Victor Lavalle's The Changeling, thanks to @introvertia's recommendation. I know nothing about it but I'm looking forward to reading it!

6) A book I’ve put down:

The War of Art, by Steven Pressfield. I know that the accepted formula for self-help books is to present your one theory and explain why it solves every problem in the known universe, and I hate it, which is probably why I don't read a lot of self-help books. Needless to say, around the time this dude claimed that Hitler wouldn't have become a mass murderer if he'd followed the book's advice, I gave up in disgust.

7) A book on my wish list:

Honestly, I don't have many? I've been enjoying reading from the library, in part because my bedroom is already showing the strain of previous book-buying sprees.

8) A favorite book from childhood:

The Woman Who Rides Like a Man, by Tamora Pierce. I read the entire Alanna series numerous times but I think this was my favorite—I really loved seeing her come into her own independence and learn a new culture (and one that accepted her unusual gender presentation).

9) A book you would give to a friend:

Again, depends strongly on the friend...but I can think of more than a few who'd enjoy the old-school gothic fairytale setting and viciously driven heroine of A. G. Slatter's All the Murmuring Bones.

10) A book of Poetry or Lyrics you own:

Hm...does the script to Hedwig and the Angry Inch count?

11) A nonfiction book you own:

The Devil in the White City, by Erik Larson—they practically issue you a copy when you move to Chicago. (In fairness, it's a cracking read.)

12) What are you currently reading:

Skin Folk, a collection of short stories by Nalo Hopkinson. I'm also rereading (or re-listening to) Mike Carey's The Devil You Know, and enjoying it rather better this time around—I think the first time I tried it, almost ten years ago, I was expecting something more along the lines of The Dresden Files and wasn't quite old enough to appreciate the more emotionally battered and worn-down middle-aged protagonist. Now, being a decade older and having lived through a global pandemic and seen rather more of just how terrible people can be to each other...I think it's more my speed. And possibly good research for if I ever get my angel noir story off the ground.

13) What are you planning on reading next?

Definitely The Changeling.

Bonus Round Shelfie?

I'm at a library right now but I might add one later!

Tagging: @klove0511, @sirsparklepants, @emiliosandozsequence, @skybound2, @ihni, @callieb, @lord-angelfish, @redmyeyes, @misschinablue, and @sea-salted-wolverine—no pressure, obviously, but I'd be interested in your answers!

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

🌌 The Bohemians of the 1830s: Rebellion, Reform, and Romance 🌌

In a world choking on industrial smoke and rigid norms, the 1830s Bohemians were a breath of wild air. This wasn’t just a lifestyle—it was a revolution. Artists, poets, and visionaries turned their backs on society’s scripts, carving out a new, untamed world where freedom and passion reigned.

🗣️ Social Reform Movements: The Dreamers Who Took Action

Bohemians weren’t just lost in daydreams; they were fierce. They were abolitionists, feminists, labor rights advocates—fighters who saw the system for what it was and said, not on our watch. While the middle class worshipped at the altar of money and manners, Bohemians embraced a life of art, defiance, and connection. Freedom over wealth. Creativity over conformity. And Bohemian women? They blazed new trails, demanding education, equality, and the right to live and love on their own terms.

🎨 Romanticism: Where Nature and Emotion Collide

In the 1830s, Romanticism hit like a storm, sweeping Bohemians into a world of raw, unfiltered emotion. They turned their backs on cold rationality, trading it for art that felt—for moments in nature where beauty wasn’t just seen, but felt in every cell. Nature became their sanctuary, far from the clamor of factories and city grime. Art and poetry weren’t just words or paint; they were reflections of the untamable, the unpredictable, the deeply alive. 🌲🌌

📜 Literary Experimentation: The Power of Words, the Pull of Mystery

The 1830s were a golden age of literary rebellion. Writers like Dickens and the Brontës dug deep, bringing social issues to light and unearthing the hidden lives of their characters. Gothic aesthetics took hold, wrapping mystery, the supernatural, and a haunting beauty around every word. It was the age of Keats and Byron, of poetry that didn’t just talk about self-discovery but bled it—lines that captured the endless longing, the quiet beauty, the burning questions of existence. For Bohemians, every word was a mirror, a map for their own journeys into the unknown.

🧠 Nietzsche and Kierkegaard: Philosophy That Dared You to

Be

The 1830s sparked a philosophical shift that resonated deeply with the Bohemian spirit. Nietzsche’s ideas called for an unapologetic life. Break the mold, find your will, carve your path. His idea of the “Übermensch” was an invitation to transcend the ordinary, to be bold, to craft yourself and live on your own terms. It’s easy to see why Bohemians, already questioning society’s rules, embraced this call for self-mastery and authenticity.

Then there was Kierkegaard, the philosopher of angst and existential choice. Life, he said, is a journey, and it’s yours—marked by moments of profound choice, defined by what you’re willing to leap into without guarantees. Kierkegaard’s “leap of faith” resonated with Bohemians who were living passionately, searching for meaning outside conventional walls. In a world of logic and rules, he offered a path that was personal, raw, and infinitely true.

🎭 Theatre and Melodrama: A Stage for the People

Bohemian theatre wasn’t just about entertainment; it was about truth. The rise of melodrama meant emotion took center stage, and plays reflected the struggles, dreams, and despair of ordinary people. Every scene was a pulse, a mirror to society’s cracks. Bohemians used theatre to challenge, to provoke, and to stir something real in the hearts of their audiences. It wasn’t just a performance; it was a call to change.

👔 Dandyism: Fashion as Rebellion, Style as Identity

Enter the dandy—a figure of flamboyance, elegance, and absolute individuality. The dandy made fashion art, rejecting toxic masculinity and rigid norms. Every hat, every coat was a statement of freedom, a celebration of self. To live as a dandy was to refuse to be defined, to craft yourself as a work of art, a testament to the Bohemian ideal of living boldly, deeply, and entirely on your own terms.

The Bohemian Legacy: Freedom, Art, and a Life Without Compromise

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

can we have... all the etymology

All of the characters on my toyhouse should have etymologies for their names and middle names, so check there for those. Aside from that, some interesting ones include:

ColdR: “Cold air”, gives a vaguely sci-fi feel. As the title of the game itself, it refers to the prevalence of ice in the game’s mechanics and worldbuilding.

HotR: “Hot air”, matches ColdR

World of Zero: “Zero” brings to mind a void, and comes from such terms as "subzero" and "absolute zero". “World” here refers to a realm, not a literal world. The “World of Zero” is found below the regular “World”, which could be considered “1” in this scenario.

World of Infinity: The opposite of the “World of Zero”. If Absolute Zero is the coldest temperature, then the hottest temperature is infinite. The World of Infinity’s status as being accessed from Zero portals within the World of Zero is inspired by “division by zero” and the impossible paradox it causes. It is also themed after “integer underflow”, a programming quirk that occurs when trying to go below the lowest number possible in a given program - causing it to “underflow” to the highest number instead, which in this case is “Infinity”.

Many family names are named after programming languages, or other programming terms, while many first names are named after sea animals. This creates a feel of thematic consistency and also reflects on the series' themes of environmentalism and technology. Some notable family names include:

Nothyp: Python backwards.

Clua: C + Lua, brings to mind a cold and icy image, alliterates with Cold(R) and Coralde

Scripte: Originally was "Avascuript", from JavaScript, but it felt like a mouthful so it was shortened, with an E added for the French feel.

Hetamel: HTML. Feels kind of wet.

Unixell: From Unix and Excel.

Soluta: A play on “Clua”; if “Clua” is a “Clue”, then “Soluta” is the “Solution”.

Visbaze: From “visual basic” programming language. “Viz” includes an “ice”-like sound.

Wada: Japanese family name that means “harmonious rice paddy”, which doesn’t really pertain to the character it's on but suggests she has Japanese ancestry. Contains the programming language “Ada”.

Psysol: From “psy” and “sol”, as in sun, alluding to the character’s psychic fire powers. Also sounds like “solitude”, giving the impression Iolas is a loner.

Lascap: Anagram of “Pascal”, a programming language. Alliterates with Lybia, the name of the most important Lascap.

PSI Age: Evokes the idea of a new time period, and puts immediate emphasis on the importance of PSI to the setting. Also, if ColdR Prime was the “ice age”, then this is the “PSI age”.

Devil's Darning Needle: “Devil’s darning needle” is an alternate name for the stickbug, which XXX physically resembles with her tall and gangly physique. Devil gives the impression of a rebellious and/or gothic person, while darning needles refer to her knitting passion. It also evokes the idea of her “piercing” through the Sectors. The connection with needles and knitting also brings to mind puppetry. XXX herself has been used as a “puppet” by various people through her life, ranging from ???, to !!!, to her current situation with the Sectors.

Cradlelands: The Cradlelands are an isolated place, like a “cradle” for the people living in them. It is also a very “primal” kind of place, giving a sense of, say, “humanity’s cradle”; and for Erco III and co, it is seen as a place of origin; a place that feels like home. One could also link it to how Berceuse takes care of her subjects; very protectively, as someone would cradle their child. And, well, they’re lands. So, Cradlelands. It’s meant to give the idea of a vaster, uncharted place, that one may want to explore. It’s home, but much is unknown about it, and they want to know more.

Alright let's get into the stuff yall will actually eat up.

Emperor Berceuse: “Berceuse” means “lullaby”, and in French also refers to a rocking motion. This overall ties into the same sort of themes and aesthetics you would get from “cradle”. It also fits the intense care she provides towards Nester, and later her subjects in the Cradlelands.

Notably, both she and Erco share an “Erc”. Berceuse also ends in an “Eus” sound, which brings to mind the likes of “Zeus”, “Deus” and other words associated with divinity, helping create the impression of a figure bearing incredible power.

“Emperor” is added to the title to give the impression of a highly powerful, outright tyrannical ruler. It is used instead of “Empress” due to it suiting Berceuse’s overall image better; Berceuse, as far as ruling goes, is very gender-neutral and does not place any emphasis on her femininity. (Also, it helps make her seem less like a person and more like some kind of mythical force; and her identity may originally have been a secret, and she is still intended to leave much of her past shrouded in mystery in-universe.) It is also a name that could fit well in a fantasy masquerade, while also suiting a more science-fantasy type of antagonist.

Daemon: “Daemon” is a word for a program that runs as a background process in computing; Daemon, too, is essentially responsible for handing much of the background tasks for the Berceuse Empire in her sister’s stead; it being tied to technology helps make Daemon appear as a very mechanical and scientific type of character.

Yet it also has many fantasy connotations. A daemon in greek mythology was a type of guiding spirit, which she could be considered to be towards Berceuse; almost like some kind of guardian angel (which she visually resembles with her wings). And yet, at the same time, it also refers to demons. A common motif with Daemon is that she is an “angel” towards some and a “devil” towards other; and even her name suits this.

Berceuse Empire: Since Berceuse is an Emperor, it is logical that what she rules would be an Empire. Since much of it centers around her and her image, it is named directly after herself. It also gives the image of an oppressive, regimented kingdom, fitting her tyranny and conquering.

Aye-aye: From “Erco II”, or specifically the “II” part at the end, which, when spelled separately (as it is intended to be), sounds like “Aye aye”. Also comes from the animal, which she has some features in common with, such as her “ears” or her orange visor. Since it’s an animal’s name, it also gives a bit of a wild or animalistic image, which suits her.

It also creates an opportunity for wordplay; as she is a captain to some rebel groups, one could imagine people saying “Aye-aye, captain”; which could both be an expression of agreement with her, or a description of her. The fact that it sounds like an agreement specifically may also give the idea that it is difficult to disagree with her.

Aion: From “Erco I”, specifically the “I”, and the Greek deity “Aion”, who is a deity representing the cycle of time; Aion, of course, happens to have time powers, and it being a deity gives Aion a cool and strong image. Aion representing cycles also ties into OUROBOROS, which Aion has notable ties to.

Aia: From “Amonea I” and Aion; essentially being a feminine version of his own name. Aia’s design looks particularly mythical, as well, and her design is reminiscent of a spartan outfit, continuing the Greek theme.

OUROBOROS: From the name of the ancient symbol, which is often used to represent cycles; and OUROBOROS, or at least the form seen so far, is symbolic of the cycle of pain Ophione and Astralde go through. The symbol also specifically depicts a snake, which Ophione is already symbolized with (And Ophione is actually aware of OUROBOROS, unlike Astralde.) OUROBOROS being in all caps is something not seen often in ColdR (or Sekaiju), which helps give the impression that it is a level above other entities seen in the former (and most in the later).

Dogma of Self: Represents the ultimate expression of the self and the ego; a power so strong it is imposed onto others. In other words, a “Dogma” representing the “Self”. It is achieved when one fully realizes their own independence and individuality; when no one but themselves is determining who they are; when the only one making “Dogmas” about their identity is themselves. Finally, “Dogma of Selves” tend to involve abilities so powerful they practically change the rules of reality; shifting the “dogmas” of reality to the “dogmas” of the self.

#coldr#wowsers this is a big post#emperor berceuse#berceuse sekaiju#daemon sekaiju#etymology#many of them

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

What do you find more interesting to draw in comics?

Now this is an interesting question! My answers will probably be a little abstract but here we go:

hmm drawing and writing are pretty much the same to me. I never write scripts for my original comics I just start sketching a lot. I love creating long-form comic stories so I basically draw what the story needs. (but also write what the images need)

There are some aesthetic movement/style I love such as medieval revivalism, Jugend style, Gustavian style, Glasgow style, Gothic horror & romanticism... I combine different influences that resonate with me to create something that's true to me. In generally I tend to approach my comics more aesthetically.

There are also some themes that basically inform my whole direction as an artist. The big one is my interest in the destructive power of love and desire. I think inner conflict is just inherently part of our everyday lives because we live in a world that coerces us to internalise some pretty fucked up ideas about humanity.

I prefer drawing erotica because it's a great tool to explore those themes to their fullest both symbolically and literally. it's about connection through bodies but also separation because it can be messy, gross and off-putting. I love that contrast and conflict. Return of the Demon Girlfriend is especially about that.

I guess I could have answered something normal like "blonde twinks" or "hot middle-aged men crying" but here we are.

#artists are just kinky little perverts whose work is to channel our collective obsession and trauma I think#ask sarasade#perlelas

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Some movies, considered chronologically:

THE FLAMINGO KID (1984): Nostalgia-burdened period piece, set in 1963, about working-class kid Jeffrey (Matt Dillon), who gets a summer job parking cars at an exclusive beach club called El Flamingo, starts dating a rich girl (Carole R. Davis), and becomes fascinated by her father (Richard Crenna), a self-made sports car dealer and local card sharp who thinks college is sucker's game. This alienates Jeffrey's own father (Hector Elizondo), a stalwart plumber who doesn't want to see Jeffrey squander his chances of bettering himself. The story is thus a sort of YA prototype of Oliver Stone's later WALL STREET — a Reagan-era morality play about a young man caught between two father figures, one representing the Lure of Easy Money and the other a paragon of Honest Hard Work — badly undermined by its absurdly idealized longing for the alleged innocence of the Kennedy era (underlined by an obnoxious oldies soundtrack). It offers a meaty role for Crenna, but as a drama, it has less substance than FERRIS BUELLER'S DAY OFF. Davis's character is such a nonentity that you keep forgetting she's there, and the way she ends up functioning as a proxy for Jeffrey's obsession with her dad is awkward. CONTAINS LESBIANS? Nope. VERDICT: A simple-minded story blinded by its rose-colored glasses.

THE JOY LUCK CLUB (1993): Sudsy but affecting episodic adaptation of Amy Tan's novel about four middle-aged Chinese women and their strained relationships with their Chinese-American daughters, starring Ming-Na Wen and nearly every other Chinese actress working in the U.S. at the time. The way the script segues between the characters' respective stories is clunky, and it often teeters on the brink of schmaltz, but there are moments of real dramatic power amongst the more superficial tearjerker moments, and you'd have to have a stonier heart than I to not sob at the bittersweet ending. Strong acting helps, with Tsai Chin particularly good as Auntie Lindo. CONTAINS LESBIANS? It seems like it should, but alas. VERDICT: Heavy-handed at times, but undeniably moving.

COLD COMFORT FARM (1996): Before she became an action star, Kate Beckinsale starred in this hilarious adaptation of Stella Gibbons' 1932 satiric novel about glib orphan Flora Poste, who makes it her project to fix all the problems of the titular farm and its eccentric denizens — distant cousins who feel obligated to Flora (whom they will only address as "Robert Poste's child") because of some unspecified wrong they once did her late father. Among the inmates of Cold Comfort are Cousin Judith (Eileen Atkins), a hysterically morose creature straight out of a gothic novel; Cousin Amos (Ian McKellen), a fire-and-brimstone preacher who warns his brethren, "There'll be no butter in Hell!"; Amos and Judith's oversexed son Seth (Rufus Sewell), a local stud who dreams of being in the talkies; and of course Aunt Ada Doom (Sheila Burrell), who rules the family with an iron fist and won't let anyone forget that she once saw something nasty in the woodshed. A delightfully silly spoof of a particular category of once-popular English literature, as the farm's assorted grim melodramas prove no match for the implacable (if somewhat snobbish) modern sensibilities of its plucky heroine. CONTAINS LESBIANS? Nope. VERDICT: Great fun throughout, although Stephen Fry irritates as a boorish "Laurentian person" who keeps hitting on Flora despite her obvious disinterest.

BREAKDOWN (1997): Competent but underwhelming Jonathan Mostow thriller starring Kurt Russell and Kathleen Quinlan as Jeff and Amy Taylor, a couple of Yuppies whose fancy Jeep breaks down on the highway on a trip from Massachusetts to California. A passing trucker (J.T. Walsh) gives Amy a ride into the nearest town to find them a tow truck, but when Jeff gets their Jeep running again and follows her into town, he finds that Amy has disappeared, and no one, including the trucker, will admit to having seen her. It has a great premise, and Russell is credible enough in the lead, but it's pretty ordinary, and, once you know what's going on (which is revealed a little over a half-hour in), pretty superficial — there's no psychological depth, and I kept waiting for some other story twist that never came. CONTAINS LESBIANS? It barely contains women (Amy is absent for 80 percent of the running time). VERDICT: Not bad, but nothing special, and you'll forget it 10 minutes after it ends.

MY TWO HUSBANDS (2024): Okay Lifetime thriller about a young woman named Eliza (Isabelle Almoyan), still reeling from the recent murder of her mother (Joanie Geiger), who becomes deeply suspicious of her father's young new wife, a flight attendant named Brooke (Kabby Borders) who's no older than Eliza — and, as the title alludes, is secretly married to another man (Britton Webb, who looks like a lesser Baldwin brother) and up to no good. Despite the cheesy title (which is really also a spoiler) and awkward marketing (which misleadingly suggests a comedy-drama with Brooke rather than Eliza as the main character), it has a surprisingly decent, reasonably credible script, hamstrung by very weak performances. The story is still interesting enough to make it a not-bad little thriller, although it would have been better with a stronger cast and less somnabulistic direction. CONTAINS LESBIANS: It sometimes seems like Eliza's friend Star (Kristen Grace Gonzalez) might be her girlfriend, but the script is noncommittal on this point. VERDICT: A B+ script burdened with D+ acting and C- direction.

#movies#hateration holleration#the flamingo kid#matt dillon#richard crenna#the joy luck club#amy tan#ming na wen#tsai chin#cold comfort farm#stella gibbons#kate beckinsale#ian mckellen#rufus sewell#breakdown#kurt russell#jt walsh#my two husbands#isabelle amoyan#kabby borders

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

fere-humanistica revival

illustration is figure 1., «Text page from Die Nachtfeier der Venus. Printed by Officina Serpentis. 1919.», from «Tendencies in Geman Book-Printing since 1914» by dr hanna kiel [The Fleuron, no. iv, at the office of the fleuron, london, 1923, p81]. dr kiehl tells us: «The ‘Officina Serpentis’, established in 1911 by Tieffenbach [eduard wilhelm tieffenbach], is comparable to the Vale Press, being almost entirely a reflection of its founder’s personality. He is his own publisher, type-designer and printer. In contrast to other German book-artists, he has been influenced more by the Kelmscott Press than by the Doves. His own type is based upon that used for Schoeffer’s Bible …» [ibid., p75]. ‘schöffer’s bible’ refers to the first Latin Bible printed by fust & schöffer, mainz, 1462, which was set in types cut by peter schöffer: these types were a further essay of an earlier cut by schöffer and first shown in the fust & schöffer edition of durandus [Rationale Divinorum Officiorum, mainz, 1459]. [cf. harry carter, A View of Early Typography, at the clarendon press, oxford, 1969, p33.] of the model for the durandus types a.f. johnson says: «The letter shares some Renaissance characteristics and others of the Middle Ages. Hence it has been called Fere-humanistica or Gotico-antiqua. … The hand is gothic but with considerable roman tendencies. It was the formal book-hand of the earlier Italian humanists of the fourteenth century, and in particular of Petrarch.» [a.f. johnson, Type Designs, grafton & co., london, 1959, p11].

for more on petrarch’s script vide ‹mano del petrarca›.

for more on peter schöffer vide ‹not schöffers roman›.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nun 2018 Review

Her cheekbone daggers above emaciated white skin and ravenous blood-soaked teeth create a haunting glimpse of ‘The Nun’ in the gloriously disturbing universe of ‘The Conjuring.’ Her character haunted parts of its films with unsettling images for sinister shocks. Now, “The Nun” serves the entire franchise as an origin story and a full-length film. What was spine-chilling previously, now feels repetitive and predictable.

This is almost the same as the Minions, but bear with me. The Minions were arguably the star attraction of the “Despicable Me” movies. Their explosions of cuteness, in baffled expressions and denim overalls, total ineptitude, and babbling gushed joy. But who would’ve thought that a whole movie focused on them—supposedly titled “Minions”, would get monotonous quickly? Well, it happened in 2015.

I will note in the very beginning that I am \not\ saying that The Nun is like the evil version of a Minion. True, she does run around in a uniform causing havoc and carrying out her master's orders, which is quite similar, but the difference of these vital secondary characters that appears when a full-length feature film is made out of them.

However, the film has a mood of its own, courtesy of Corin Hardy's direction, alongside Gary Dauberman's script from “Annabelle” and “It”. “The Nun” has an extremely haunting start: candle-lit stone corridors, fog-locked graveyards filled with makeshift wood crosses, deep and droning chants, and fog-covered grounds, all while being set at an remote abbey in Romania. The Gothic dread looms throughout - a cursed place that remains dreadful in the face of hopeful prayers offered by young nuns.

In “The Nun”, it was the dramatic suicide of a nun which prompted the Vatican to send Sister Irene (Taissa Farmiga) the demon hunter, alongside Father Burke (Demian Bichir). Burke was tasked with uncovering the dark forces plaguing the holy site. Burke’s ‘apprentice’ Sister Irene happens to be blessed with a past riddled with visions. In an unexpected and clever twist, Burke’s visions stem from her elder sister, Vera Farmiga, who played renowned seer Lorraine Warren in the original “Conjuring” movies, creating this shared universe illusion.

The presence of the younger Farmiga is equally captivating, having a quietly commanding manner about her.

Burke and Irene are accompanied by local farmhand Frenchie (Jonas Bloquet), a flirtatious French-Canadian with a charming demeanor. He acts as their escort, supplies essential comedy, and forewarns them that they’re going to the Dark Ages. He, however, has no clue how dark things will actually become.

The Vatican’s representatives are burdened with the seemingly impossible assignment of interrogating the last remaining nuns in hope of discovering the reasons behind a sister’s mournful and sinful life. However, they either find themselves in the middle of the round-the-clock silence enforced by the sisters until the sunrise or stuck behind enormous metallic doors that lock for the night. It is as though they are going in circles, and we feel the same. Throughout all this, Bonnie Aarons’ character in the film continues to stalk the dimly lit corridors, both intimidating and untraceable. Spotting her Nun costume is initially startling in a good way several times - unfortunately, Hardy exploits this technique a bit too much. He reveals what he presumes to be The Nun - though she’s more accurately A Nun - praying from side and back view, or sidestepping and blending into black curtains of fabric. These cheap thrills, take place repeatedly and in a predictable manner.

Hardy does manage some visual stunts to pep things up in this crowded and stuffy place; a few of the overhead shots are brilliant, particularly the one where Irene, clad in a white habit, is flanked by her fellow nuns dressed in black, kneeling and praying fervently. But by the end, “The Nun” is almost entirely a different story: an infuriatingly puzzly “Da Vinci Code”-lite, which I know sounds redundant. We eventually get full frontal Nun—more Nun than people want to see—but even while she’s in our face, it’s still uncertain what she actually seeks apart from a rather dull possession.

Unlike the “Conjuring” movies, which vertically stand the test together with James Wan’s original two, and not really the “Annabelle” prequels, all “demon-themed” horror felt incredibly flat. The Nun feels like an emtpy thrill ride in comparison. Once it stops and you step off, you might feel dizzy, but Eller forgot the reason why.

0 notes

Text

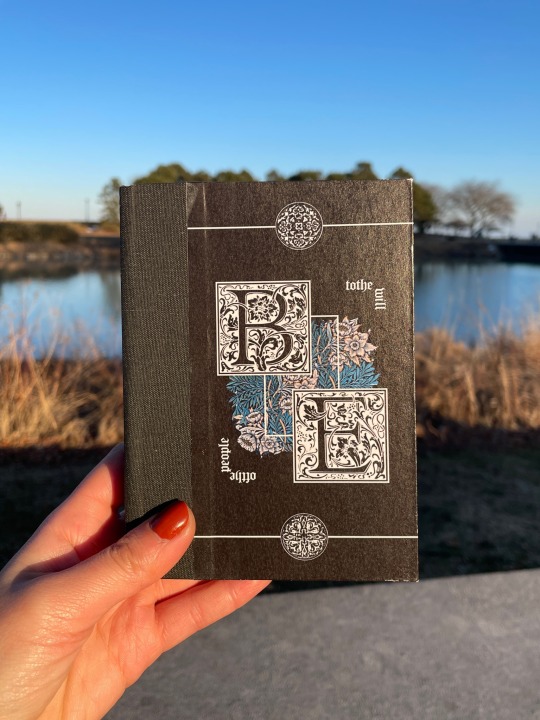

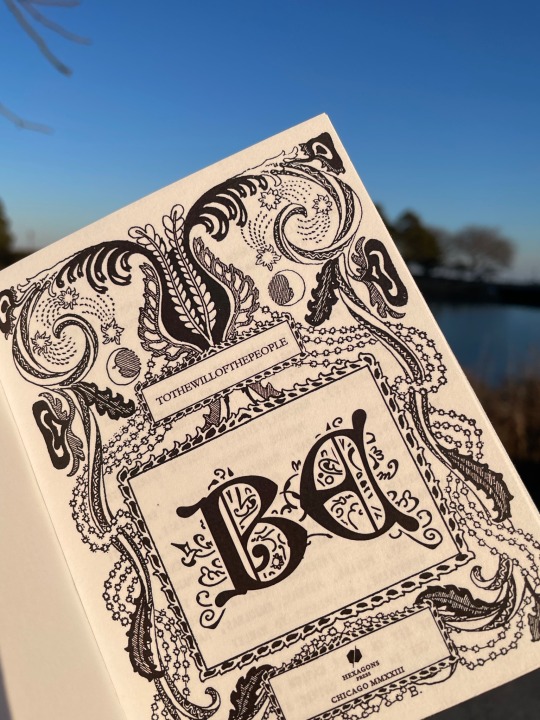

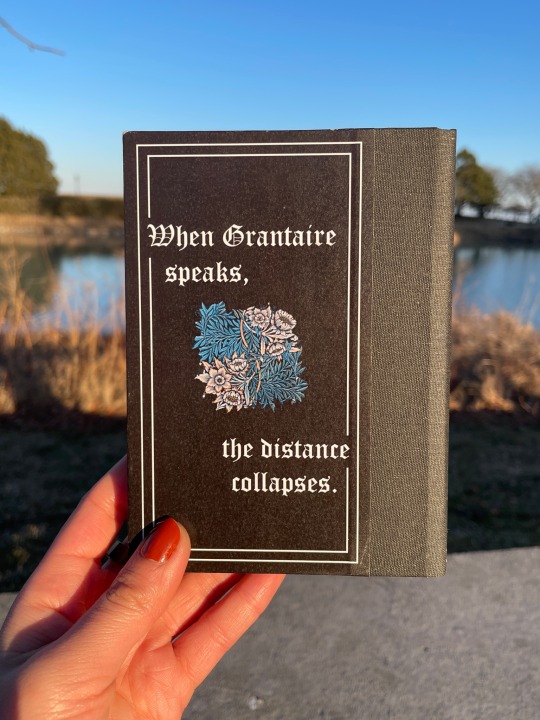

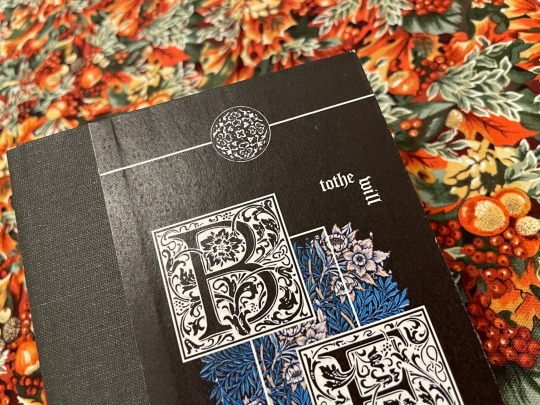

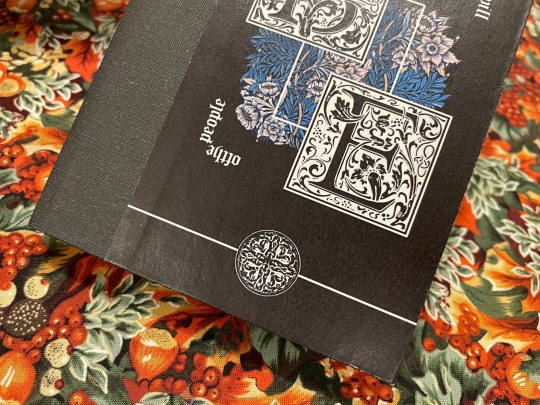

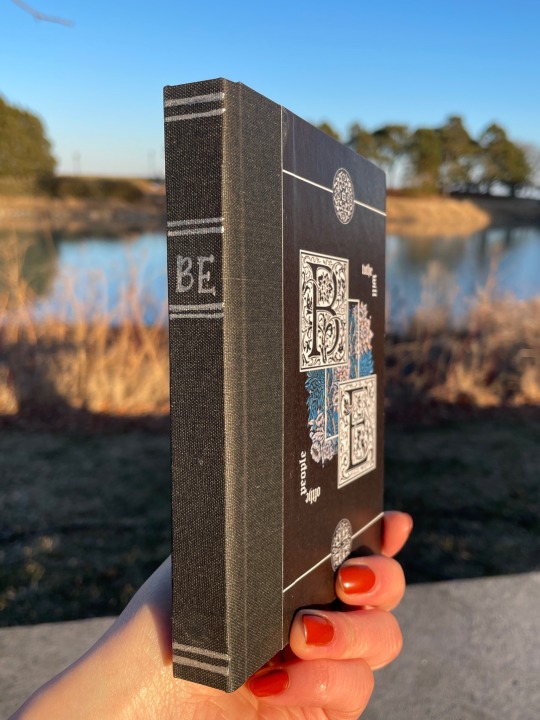

BE by tothewillofthepeople

Grantaire is earnest in this, and it’s heartbreaking. Enjolras can’t look away. This is just a rehearsal. Grantaire is still wearing skinny jeans. They have lights and phones and textual analysis and thousands of years of history between now and then and yet– When Grantaire speaks, the distance collapses. (Grantaire as Hamlet.)

Title: Middle Ages Deco Headers/Accents: Letter Gothic Standard Body text: Adobe Caslon Pro Case title: Goudy Initialen

38,667 words | 224 pages

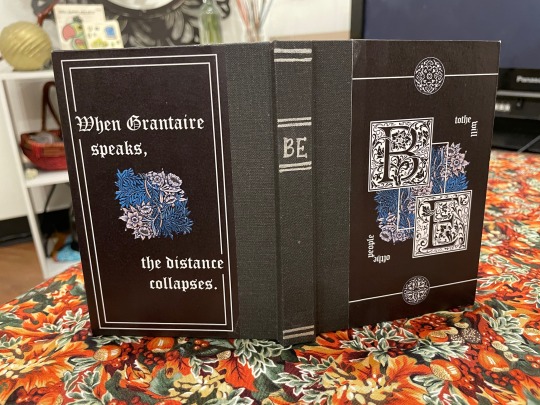

Binderary book 1: a long-favourite EXR fic. I love wild Les Mis AUs and I love Shakespeare and this is all of that in such a lovely lovely form. Stage manager Enjolras is inspired. Also, I've been frothing at the mouth to use my special blackletter fonts and go suuuper overboard designing and this was Perfect for that purpose.

More pictures/design/process under the cut.

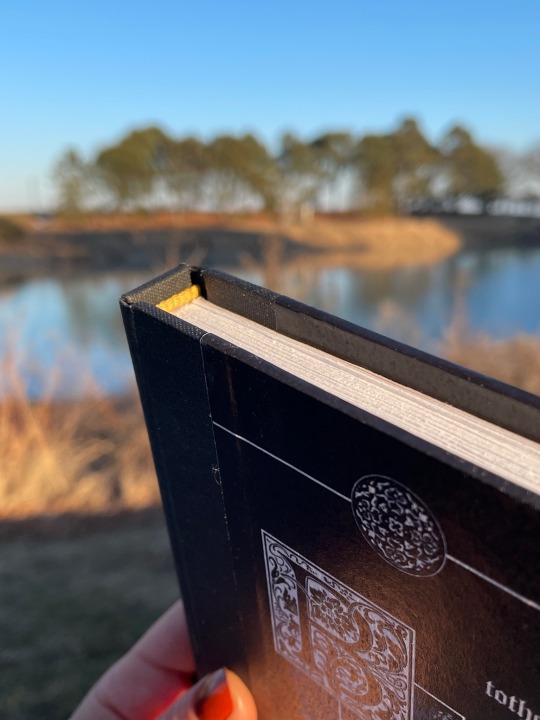

Design and Construction Case: Flat-back case binding with bradel board covers and spine. The spine cloth is Hollander's pearl linen in charcoal grey. The painted titles were done in Amsterdam acrylic ink in silver, with a pair of scissors because I don't own a painting brush and likely never will. The cover papers are printed on 80gsm white printer paper and glued with a regular Elmer's glue stick and PVA on the turn-ins, and the whole case is sprayed with workable fixatif to (hopefully) preserve it longer-term.

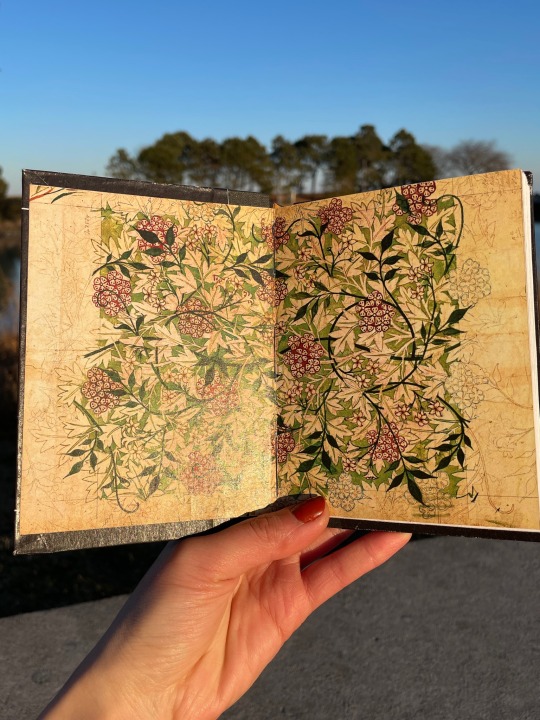

Covers: The front and back covers were designed in Photoshop. The centre image is a William Morris pattern, and the top and bottom little circles are Renaissance printer's ornaments (pngs by the lovely @helle-bored of Renegade Bindery) that I vectorized in Illustrator (Illustrator and I were sworn enemies until this month. Now we're forced friends. Like enemies to lovers).

Insides: Endpapers are a William Morris pattern recoloured in Photoshop to be a richer green and red, obv, for EXR. Printed with inkjet on 80gsm printer paper and glued to gold cardstock, and sewn into the textblock. Endbands are pre-sewn from Hollanders, dyed gold with acrylic ink to match the endpapers.

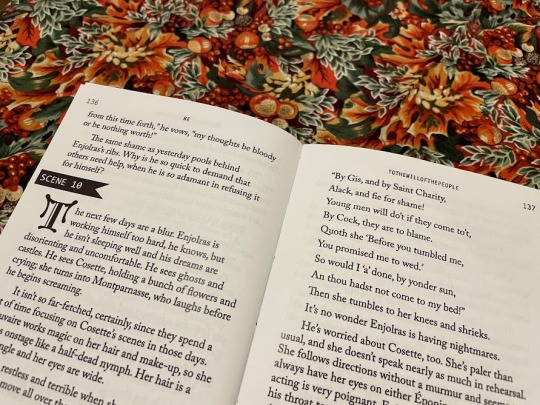

Typesetting Typeset was done in InDesign. This is a one-shot with scene breaks, so to match the theatre theme of the piece I replaced the horizontal line breaks with flagged scene numbers. I tried to strike a balance in the typesetting between classic Shakespearean aesthetic with the blackletter drop caps and cover fonts versus what you might see in a theatre script book with the monospace accents. The title spread uses a transparent decorative frame, again from Helle's collection; the large box in the middle with the title was part of the original frame and then I duplicated and resized it for the author name and my imprint.

We All Do It, or, the Mistakes Section I somehow managed to print the cover papers nine inches tall and didn't see a problem with it until they came off the printer. Truly who knows how that happened. I was working on the case at two in the morning and cut the spine cloth the wrong length three separate times...earned the measure once cut twice badge big time for that one. The endpapers were an ordeal and a half for real. What I learned: print them too big and glue the cardstock to the back, then trim the paper to size, not the other way around otherwise you'll end up with big ugly gaps where the trimming was a few millimeters off. Whoops.

And...more pictures

I'm particularly pleased with how the covers here came out so here's closeups. Also, the arc on the spine that you can see in the endband on the last one is really pleasing to me lol I fought a war trying to get the flatback hinge calculations right.

225 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gothic Writing and Typography

Today, we continue our month-long appreciation of Gothic finds in the Noel Collection with a focus on letterforms. The Gothic style, characterized by angular strokes, has had a profound impact on the history of written communication in the West.

Gothic script (also known as blackletter or textura) originated as a form of calligraphy in late twelfth-century Europe. As the book trade of the High Middle Ages grew, medieval scribes favored blackletter over the older Carolingian miniscule style because blackletter was quicker to execute.

The Noel Collection’s fragmentary leaf from a thirteenth-century breviary made in Cluny, France, is written in the textura quadrata style.

The mid-fifteenth century saw the dawn of the Western printing press, and Johannes Gutenberg issued his famous 42-line bible in a textura typeface. Most printers of the incunabula period (ca. 1450s-1500) chose a Gothic type design because they wanted to evoke the familiar writing aesthetic of late medieval scriptoria.

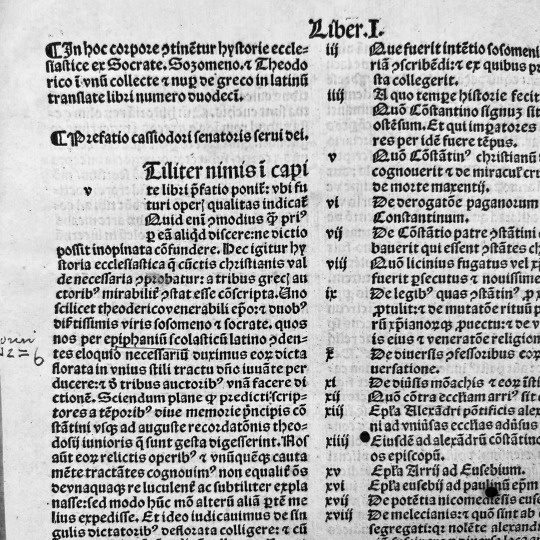

This copy of Cassiodorus’ Historia ecclesiastica tripartita is the oldest printed book in the Noel Collection, dating back to 1492! It also features one of our oldest examples of Gothic typeface.

The Renaissance and the return to the study of classical works saw the rise of Roman typefaces. The rounded and more legible style of designs such as Antiqua came to rival medieval Gothic fonts and their variants. However, many bibles were still printed with Gothic letters; for Western Europeans at the time, the font still held gravitas and conveyed the authority of tradition. The main text of the 1611 King James Bible was notably set in Gothic font, while supplementary scholarship and commentary was in Roman.

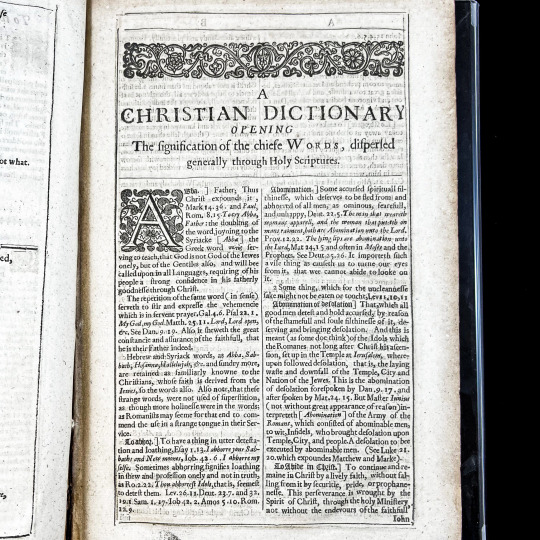

In Thomas Wilson’s Christian Dictionary of 1648, the terms are in Gothic font (perhaps matching the Gothic text of the Authorized Version of the English bible) while the definitions and explanations are in Roman and Italic typefaces.

Even though Roman typefaces held sway over most of Western Europe, Germany fully embraced the Gothic Fraktur font after it became a nation-state in 1871. All official German publications and many other books were published in Fraktur, which increasingly became associated with German cultural pride and identity. The Fraktur style and German literature were inseparable until 1941 when Adolf Hitler banned the font on the (unfounded and problematically Antisemitic) grounds that Gothic typefaces had Jewish origins.

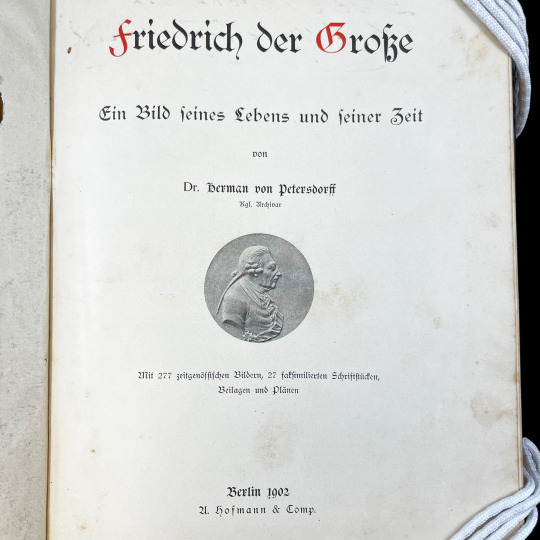

This 1902 biography of Frederick the Great (German, Friedrich der Grosse) celebrates the Prussian ruler and Germanic hero in Gothic typeface.

Images from:

Medieval manuscript fragment from a breviary. Cluny, France(?), ca. 1200s. Catalog record: https://bit.ly/3EsYYaI

Cassiodorus. Historia ecclesiastica tripartita. Paris: Wolf, ca. 1492. Catalog record: https://bit.ly/3MmAxgT

Wilson, Thomas. A Christian Dictionary. London: Richard Cotes, 1648. Catalog record: https://bit.ly/3yuG8MH

Petersdorff, Herman von. Friedrich der Große. Berlin: A. Hofmann, 1902. Catalog record: https://bit.ly/3VflBVX

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

““The Moviegoer” isn’t really about movies, and yet the title remains unexpectedly apt, just as it was when the novel, published in 1961, became a surprise winner of the National Book Award and made a sudden Southern eminence of its author, Walker Percy, a nonpracticing physician and self-taught philosopher in early middle age. It’s apt because it moves the novel (and our expectations for the novel) out of the South. It intimates that this novel, set in New Orleans, the region’s most storied city, isn’t about history or legacy, isn’t about place at all: it’s about how we see things—a novel of perception and sensibility, dealing with the search for authenticity in a scripted, stylized, mediated world.

Percy’s contemporary Flannery O’Connor characterized the literature of the American South at midcentury as set against the typical. In O’Connor’s view, there was no typical Southern novel, and that was a good thing; for her, the best Southern novel was atypical just as life in the South (in her time, as she saw it) was atypical of American life as a whole. The Southern novel she celebrated takes unusual, extreme, even grotesque, behavior as its starting point. Such a novel is rooted, she explained, in “some experience which we are not accustomed to observe every day, or which the ordinary man may never experience in his ordinary life. . . . Yet the characters have an inner coherence, if not always a coherence to their social framework. Their fictional qualities lean away from typical social patterns, toward mystery and the unexpected.”

“As I Lay Dying,” and “Wise Blood,” and later “A Confederacy of Dunces” and “The Color Purple” and “Fishboy”: these novels are fiercely atypical. But the originality of “The Moviegoer” is more paradoxical than theirs. Unlike the novels of the South that have something of the heightened quality that came to be called gothic, “The Moviegoer” becomes atypical through its scrutiny of the typical. It takes ordinary experience—“everydayness,” Binx calls it—and makes it the subject of fitful philosophical inquiry. It promises a typical moviegoer but delivers the inimitable Binx. It calls literary categories to mind by leaning away from them.

(…)

It’s a Catholic novel (the main action takes place in the days before Ash Wednesday), and yet one whose protagonist considers himself not much of a Catholic at all, but a skeptic whose “unbelief was invincible from the beginning”—who tells us, “I have only to hear the word God and a curtain comes down in my head.”

It’s a distinctly American novel, but one that stands apart from the main line from Hawthorne to Twain to James and Wharton and then to Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Cather—the double helix of innocents at home and innocents abroad. Its key antecedents are the European existentialists Kierkegaard, Sartre, and Camus—the latter two of whom were also important for Ralph Ellison, who drew inspiration from them a decade before Percy, in writing “Invisible Man.”

It’s a novel of the search—“the pilgrim’s search outside himself, rather than the guru’s search within,” Percy liked to say—but without the usual signposting. There’s no journey to a strange culture, no savvy guide, no sloughing off of one self and the taking on of another; no raft and river, no feasting or fasting, no new world at the end of the journey. There’s just the “everydayness” of Binx’s life in New Orleans and the slight diversion of an overnight train ride.

It’s a coming-of-age novel, but one whose protagonist is nearly twice the age of Huck Finn and Holden Caulfield. Binx is about to turn thirty, an age by which American men of midcentury were expected to have settled into their adult lives. He is a college graduate, a veteran, a stocks-and-bonds broker—and yet his self is “left over,” as Percy put it in an essay. Nearing thirty, Binx is gripped by “the possibility of the search” as if for the first time. The novel was a surprise even to its author. As he wrote it, Percy, like Binx, was forced out of himself and compelled to court, as O’Connor wrote, “mystery and the unexpected” as never before.

(…)

Published in 1961, lightly publicized, little noticed, “The Moviegoer” found its way to A. J. Liebling, The New Yorker writer, who had written a biography of the Louisiana governor Earl Long and was steeped in the culture and flavor of New Orleans. Liebling shared the novel with his wife, the novelist Jean Stafford, who was a judge for the National Book Awards that year, and the novel, not formally nominated, was put up for consideration. It was a strong year for American fiction: J. D. Salinger’s “Franny and Zooey,” Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22,” William Maxwell’s “The Château,” and Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “The Spinoza of Market Street” were all nominated. The award went to “The Moviegoer.” Percy, accepting the prize in New York, framed the novel in terms he had explored in his essays (and which he would develop for the rest of his career): the sickness of modern Western society, the loss of the sense of the self, the role of the writer as diagnostician. Concluding, he made his most vital point indirectly: “In short, the book attempts a modest restatement of the Judeo-Christian notion that man is more than an organism in an environment, more than an integrated personality, more even than a mature and creative individual, as the phrase goes. He is a wayfarer and a pilgrim.”

Percy was a late starter as a novelist, and Binx Bolling is late coming of age, but Percy’s novel of Binx’s coming of age was ahead of its time. With its slack and offhand protagonist, its present-tense narration, its effortless mix of informal speech, images from popular culture, and frank ruminations on the meaning of life, “The Moviegoer” is, in my estimation, the first work of what we call contemporary American fiction, the earliest novel to render a set of circumstances and an outlook that still feel recognizably ours.

Faulkner once characterized his approach to writing as “oratory out of solitude.” Of this approach Percy made a new thing altogether. The solitude of “The Moviegoer” isn’t the solitude of a rebel or an independent, but that of a person who is alone in a crowd—in a movie theatre or on a sidewalk in the French Quarter. The oratory in the book isn’t that of the Bible or of Stoic philosophy or of a Russian novel but of a voice-over—the present-tense monologue of the person who does not tell a story so much as self-consciously offer a running commentary on life as it passes before his eyes.

(…)

And yet for all that, “The Moviegoer” seems to describe the way we live now, for its affectless protagonist observes a society whose every aspect seems mediated, contrived, statistically anticipated, manipulated in advance, so that direct experience of life can seem as elusive as the experience of God.

(…)

Southern, Catholic, ironic, oblique: “The Moviegoer” doesn’t add up, quite. What is it about? What has come of Binx’s search? What has prompted him to settle down with Kate and embrace everydayness with quasi-religious devotion? “It is impossible to say,” Binx remarks in the last line of the novel proper. It is impossible to say. And yet “The Moviegoer,” like its central character, has an inner coherence. Its take on everydayness has the quality of wonder that is the novel’s true subject. It opens out onto some larger mystery, one that we, no less than he, are still trying to solve.”

“Melville began Moby-Dick around the time Blood Meridian is set, in the violent, chaotic years after the United States annexed Texas and invaded Mexico, taking most of its northern territory and bringing its western border to the Pacific Ocean. Both novels trade on the metaphysics of nature, violence, commerce, war, and law. Both, in other words, are parables of the US empire. For McCarthy, like Melville, empire meant movement, an expectation of limitlessness, and both demonstrated a skill at describing men and animals moving through vastness, through landscapes without end.

(…)

But the movement in Blood Meridian is different. McCarthy knows that the United States made and unmade itself not on the water but within the borderlands it shared with Mexico. Unlike the Pequod, Blood Meridian’s scalping Glanton Gang turns in circles. Its men cross and recross the same desert sands; they pass the same bluffs, gullies, rivers, and creosote bushes. Victory over Mexico didn’t, at least for this group of killers, open the world. Rather, the vastness of the West closes in on them. They move east to west, then west to east, and as they do their savagery intensifies, taking on its own momentum detached from the economic logic of bounty hunting, less sadistic than naturalistic, as the men become almost indistinguishable from the landscape.

(…)

McCarthy published Blood Meridian in 1985, when Ronald Reagan, after the horrors of Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and Indonesia, launched a new round of carnage in Central America, Afghanistan, Mozambique, and Angola. McCarthy mostly guarded his political opinions, though after 9/11 he seemed to have a rather conventional understanding of geopolitics and the United States’ role in the world; he accepted the fact that the War on Terror was a civilizational war.

Whatever his opinions, McCarthy is more unforgiving than Melville when it comes to writing about US empire. The relentless violence in Blood Meridian and his other books—the hacking of limbs, the dead babies, the castrated genitalia—leaves little to the imagination.

There’s an anti-humanism at play in McCarthy, often expressed in the one-dimensionality of his protagonists. In Moby-Dick, Ahab is “possessed by all the fallen angels.” He’s an archetype: Milton’s rebel hurling defiance at the vaults of heaven, Shakespeare’s Macbeth and Lear. His vengeful rebellion against the natural order of things—not least forsaking his economic duty to his masters—can be interpreted in mythological terms, fate punishing his hubris. Yet Melville, anticipating Freud, rakes over his fears, anguishes, and desires, probing Ahab’s “darker, deeper part.” Ahab’s psyche ultimately remains impenetrable (as do all of ours) and his motives subject to debate, yet he’s a very human obsessive.

Not so with his counterpart in Blood Meridian. Judge Holden, or simply “the judge,” is a murderous, erudite, cultured, dancing polyglot and pedophile. He is a character built more from ideas than drives, a mash-up of Nietzsche and Spengler, pre-Freudian, more premise than person. When read with the novel’s setting in mind—as a story of men dispatched by Mexican and Texan officials to kill as many Indigenous people as possible to open the conquered territory to settlement—the judge’s endless speechifying elevates the violence of empire into ideology and weaves the gang’s cruelty into the fabric of existence. “War is the truest form of divination,” the judge intones. “It is the testing of one’s will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select. War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of unity of existence. War is god.” Ahab, lost in his mind’s maze, would never say anything so declarative, so detached from his passions. Yet no Shakespearean doubt, no Freudian ambivalence clouds the judge’s certainty, no more than it would the work of the property surveyors who began to transfer Mexican and Native American land to US settlers.

(…)

Hairless, large, fleshy, with dull, tallowed skin: The judge is Marlon Brando’s Kurtz, an intertextual lineage that connects the horrors from the Mexican borderland to Southeast Asia. Apocalypse Now! premiered as McCarthy was writing Blood Meridian, with Chamberlain’s centuries-old description offering an uncanny model for both. The movie, its director Francis Coppola once said, is “not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam…. Little by little we went insane,” the “we” being both the film’s crew running wild in the Philippines (its production location) and the United States running wild in the world.

One could say the same about Blood Meridian: that it isn’t about the terror that followed the United States’ taking of northern Mexico. It is the terror, overwhelming the senses with suppurating images and inflamed language, forcing readers to touch the viscera, to feel the judge’s white-whale flesh, to be disgusted by his depravity as he rapes and murders children. And it is faithful to history, for the historical sources McCarthy based the book on are filled with grotesque scenes of, as one example, a regiment of Arkansas volunteers herding their victims into a cave and “yelling like fiends, while on the rocky floor lay over twenty Mexicans, dead and dying in pools of blood, while women and children were clinging to the knees of the murderers and shrieking for mercy.”

Blood Meridian is often described as an anti-western, an effort to desanctify Manifest Destiny. Still, the novel’s violence makes it hard to mark out where McCarthy’s pessimism ends and the judge’s philosophy begins. McCarthy, we can presume, based on his life and work, distrusted ideologies of progress and the self-regard of American exceptionalism, or what Melville called “vile liberty,” an idea of freedom based on extreme individualism with “reverence” for “naught”: not for nature and not for others. McCarthy too has the Glanton Gang harmonizing the individual and the group, echoing Melville when he writes that its men were “federated” in their work—not cheerily along a keel, but more like prisoners bound tight “with invisible wires of vigilance.” There’s no eros in Blood Meridian. Thanatos rules. Sex is rape, and rape is death.

Melville transmuted death into life in Moby-Dick. He has a coffin save Ishmael, the only survivor of the stoved Pequod. McCarthy, at the end of Blood Meridian, stands that coffin upright and turns it into an outhouse, the scene of a confusingly told finale in which the judge apparently rapes and murders the only character in the novel close to being moral, the kid. By book’s end, the violence, however faithful to real events, has become so omnipotent and omnipresent that it escapes the mundane motives that drive nations to wage war, to expand, to establish control over their hinterlands. The judge has become a supernatural demon, the avatar of a re-mythologized empire. Ahab, all too human, dies. The judge lives on: “He never sleeps, the judge. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.”