#but ill limit to just comparing the initial sketch to the final one

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

@flowerakatsuka I actually LOVE getting excuses to talk about this kind of stuff so ill be happy to elaborate!! under the cut in case this gets too long (which it probably will)

so full disclosure, there was a pretty long gap between when proto-kiru (then called yoshimi) was initially Designed and when i started to flesh her out as an actual oc. i actually wasn't into ososan at the time and it was more a challenge of "how would I design an ososan oc Now now that im not 15 anymore", and i didn't pick her up again until february of this year when my BTAS hyperfixation started to fizzle out. the first drafts for keiko (then named hibari, which i changed since it was a bit too similar to one of my long-time ocs hikari) were drawn the same day i picked up yoshimi again. so she was both a day-one character and Not at the same time!

please ignore the poor lighting on these pictures.

i had a pretty strong Idea for what i wanted from keiko in terms of appearance at the start and a basic concept for her (a bit more bookish + "nerdy" than other ososan girls we've seen thus far), but I had a pretty hard time applying it to the design sensibilities of ososan. her first outfit was basically just uehara-san's outfit, and i struggled with rendering her curlier hair in the ososan style which made it look more goopy and awkward. i also wasn't quite sure what to do with her face yet.

still, i translated what i thought would be my final sketches for her and (then) yoshimi to digital, and from here I started to develop their designs at roughly the same time, sort of balancing them out and trying to make sure they look good together. i was proud of them for maybe 3 days before I decided i hated how they looked.

granted, there were a LOT of reasons for this; for one, I was color picking yanas skin tone for kiru, which didn't work well at ALL because he's way paler than it looks. but more than that I wasn't really referencing features that actual ososan characters had? so they looked more like strange fun house mirror imitations of ososan characters than anything else

see what i mean? they don't look right at all. but if you look closely you can sort of see me figuring out keikos hair!

a lot of the refining process when it came to getting to where we are now was just... referencing actual ososan characters. trying to make them feel more believable and like they could actually exist alongside the current ensemble. it was honestly more about them looking right in the style than anything else, since i like to stay pretty canon compliant in terms of design when it comes to fandom ocs-- I find that the limitations make me more creative!

for keiko specifically my main inspirations were nyaa and osoko, though i referenced dobusu's hair pretty frequently as well since they have roughly the same hair texture. she was honestly a lot harder than kiru to balance out in this sense, since i had to make sure she didn't look Too generic compared to the other pretty girls in the canon cast (i.e totoko, homura, etc). her more eccentric fashion sense is also an attempt to remedy this because plot twist! she's a weirdo!

ippei however I had down from day one. he's always looked the same and always will. my perfect creation <3

#larry time#ocs#keiko#i love to yap about character design so thank you again for the tags!!#only slightly related but i will say#despite the grief keikos design gave me in the early stages#no character has been anywhere NEAR as hard to pin down in terms of design as mayumi. my fucking god

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

art summary 2023!!!

i wanted to give slight commentary instead of just 12 random pngs so here you go

tuesday 3rd january - blah blah blah!

this was meant to be the first frame of an animation. then flipaclip decided not to work. anyway theres a lot of incomplete stuff from this year and this is (sort of) one of them. idk how to explain why theres 4 of me and what's going on, it makes sense (sort of) if you read the thing its based on.

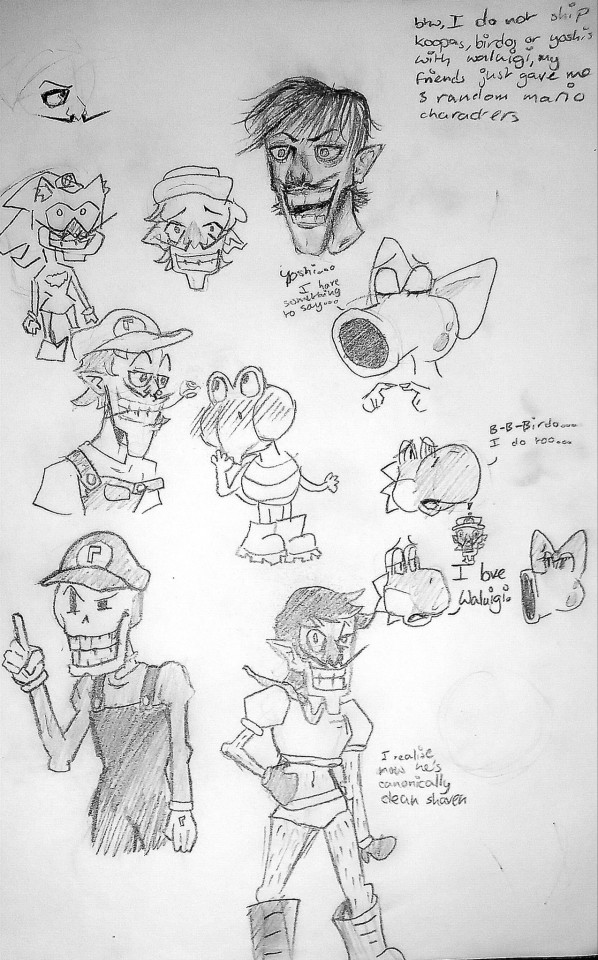

monday 20th february - waluigi doodle page

i literally cannot stress enough this is the only thing i can be certain was definitely drawn in february. i would have picked a different thing otherwise, i swear. i was on a gc late at night asking who i should draw with waluigi and they gave me yoshi koopas and birdette. istg.

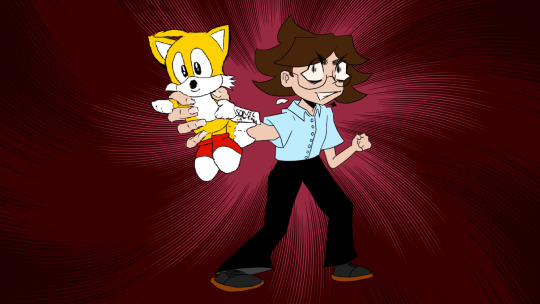

tuesday 21st march - tails and tbh (discord pfp)

FINALLY!!! SOMETHING ACTUALLY GOOD FOR COMPARING!!!

its funny how on one hand i dont draw tails like that AT ALL anymore, but at the same time, literally all my headcanons are there, like his fangs coming out when hes really happy, his fluffy ears, etc. the onky thing missing really is drawing fluffy arms and legs lol. as for the rest of the drawing, i think its ok. theres a few errors, particularly with the stroke, and i needed to fix the fill bucket around tbh's eyes, but this is nearly a year old now so im not fixing it. sorry.

friday 21st april - gently holding tails

ah, tails plushie, how i love thee. where the hell are you girl i havent seen you in months. i have waluigi now. i miss you :(

tuesday 9th may - waluigi sketch with alcohol markers

i hate alcohol markers. they dry too quickly. so it surprised me when one day, while forcing myself to like them, i drew something i actually liked. i still love this btw!!! this is the basis for how i currently draw waluigi rn, and my art as a whole!!!

also fun fact: i drew this the day before i started reading sonic idw :)

saturday 24th june - transmasc luigi watercolour stuff

once again, weird mario fanart i made while talking to a friend late at night. the initial shirtless luigi was drawn as a joke because of a really quick shirtless waluigi my friend drew at summer school in 2022 as a joke, which is what the weird one who craves death is based on. weird as this art may be, this was such a happy time in the year for me and i miss it greatly :)

ill have to do july - december in a follow up post because i reached the image limit lol

#art#woe. art dump be upon ye#annual summary 🎉#(hopefully ill remember to do this next year lol)#waluigi#papyrus undertale#yoshi#birdette#koopa troopa#miles tails prower#tbh creature#luigi

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

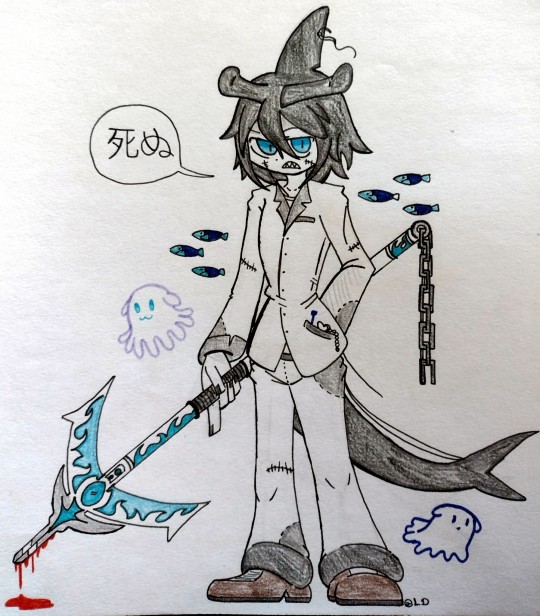

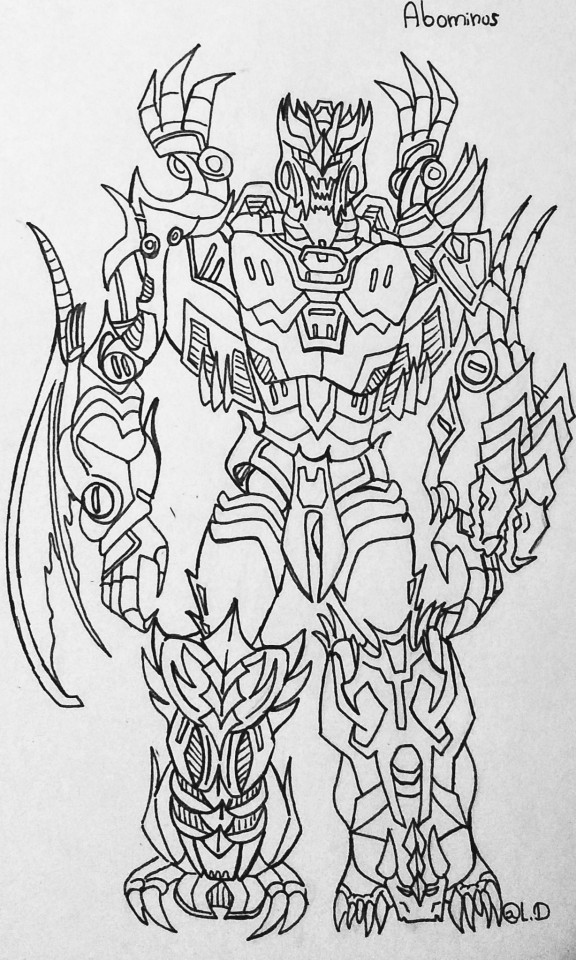

If I feel like posting my crown jewel of an oc then I can and I will

#i could ramble. so much about him#but ill limit to just comparing the initial sketch to the final one#like he has more outfits and weapons but you know.#abaddon my beloved despite being the absolute worst#sok does oc stuff#finally thought of a tag for ocs too haha. guess ill edit the other oc posts someday to organize#sketch

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

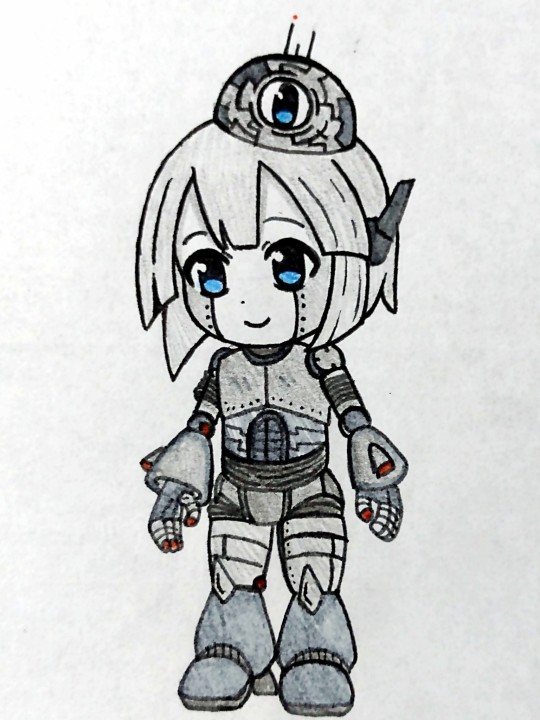

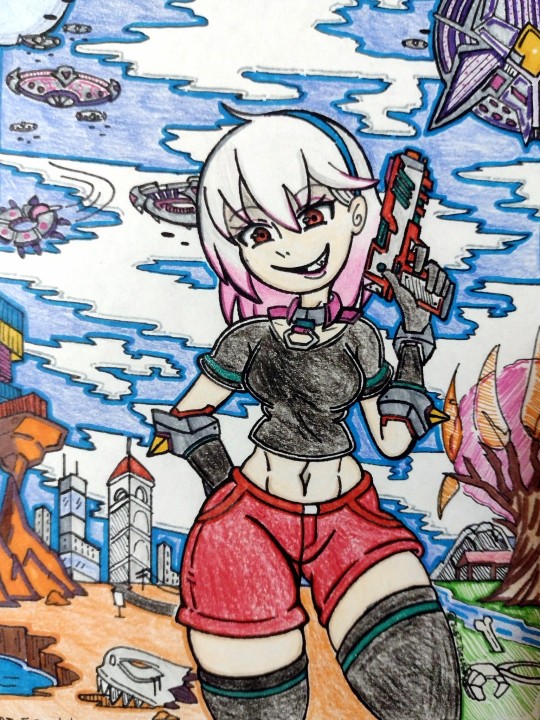

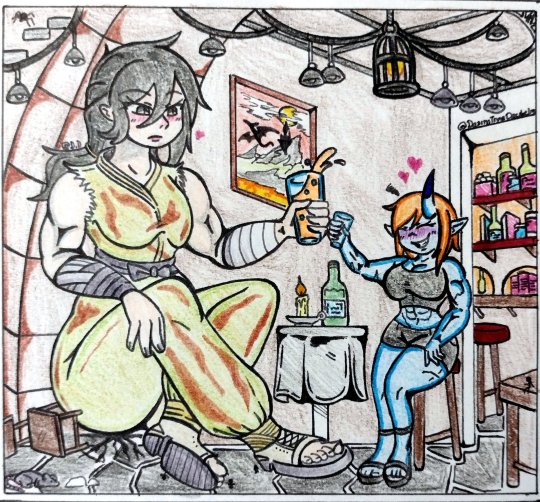

• Commissions on Traditional Art (SFW)

-Pencil: 1$

-Highlighted: 5$

-Colored: 10$

-OC Creation: from Scratch: 50$ USD (with references: 30$)

-Icon: 8$

-Chibi: 12$

-Comic: 25$ (panels limit 6, each extra panel costs 5$)

• Example: https://www.tumblr.com/just-decibelio/754367433029156864/ill-leave-this-here-for-those-who-are-interested?source=share

-Long Comic: 100$ (compared to the normal comic this one is made by 6 full pages that can contain different panels, each extra page cost 20$)

• Example: https://www.tumblr.com/just-decibelio/754368516877107200/for-those-who-are-interested-in-a-long-c%C3%B3mic-this?source=share

• Detailed Background: +5$ with the initial payment of the piece

• Character Limit: 2 (more characters after the base 2 costs 10$)

• First time you commission me? You get a totally free piece alongside your first order (only once)

• Final payment will receive a small increase due to PayPal's fee

Examples:

•Commissions in Traditional Art (NSFW)

-Pencil: 3$

-Highlighted: 8$

-Colored: 15$

-Icon: 10$

-Chibi: 17$

-Comic: 30$

-Furry: 20$

↓ Same Limits as SFW commissions ↓

• Payment only through PayPal or Ko-fi (from now on the payment must be sent in advance before starting the piece, there's no refunds after the initial sketch it's done)

• Final payment will receive a small increase due to PayPal's fee

• I draw the line when it comes to IRL people or underage characters, if it's a person you know you need their permission first.

#commission#prices#commissions sheet#deepseaprisoner#funamusea#fortnite#giantess#fanarts#traditional art

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jojo Rabbit

The problem with ‘Jojo Rabbit’ isn’t that it’s offensive. It isn’t offensive, it’s just that it’s not especially good.

Taiki Waititi’s self-styled ‘anti-hate satire,’ as has been widely-publicised, casts the Polynesian-Jewish actor as the titular Jojo’s (newcomer Roman Griffin Davis) imaginary best-friend Hitler. A grotesque, fumbling and fitting mockery, Waititi’s portrayal is more akin to Family Guy’s Fuhrer iteration than, say, any of Mel Brooks attempts; more on this later.

Scarlett Johansson fulfils the role of Jojo’s mother Rosie in Waititi’s second very deliberate piece of casting. The actress, in her portrayal evoking the imagery of the propagandistic Aryan myth, like Waititi is of course Jewish. The Ghost in the Shell star is well-known for her outspoken views on the appropriateness of her casting specifically yet not exclusively as regards criticisms that have been made relating her perceived racial background. Her decision to take up the part in this skewering of racism, conversely necessitating an actress who is anything but white playing a figure of archetypal whiteness who too expresses an antithesis to hatred herein, is no doubt a subtle riposte to many of her detractors.

Unfortunately, the film sparingly works on anything close to this level.

The exceptions are Sam Rockwell and Rebel Wilson as Jojo’s instructors, with the humour inherent in Wilson’s portrayal in particular underlining both the malevolence and absurdity of rampant extremism while not neglecting to emphasise it’s devastating effects. Repeated protestations that children sacrifice themselves for the cause while she remains at a distance strike the balance and searing real-life resonance that Jojo Rabbit pursues throughout, with the film otherwise often absent necessary grounding in real-life consequence.

Sure, there are allusions to the Shoah (Holocaust) for example, which is overwhelmingly related through the experience of Elsa, a young Jewish girl who is hiding in the walls of Jojo’s house, played by Leave No Trace star Thomasin McKenzie in yet another star-making turn. The film wants to relate a broader historical context, and certainly there are many examples of features, as early as the likes of Casablanca, that have done so absent graphic imagery and within the confines of a smaller narrative.

Conversely, Jojo Rabbit presumes an audience knowledge of the extent of the Nazi’s atrocities (irrespective of the victims’ backgrounds). No there is not a single film or text that can adequately account for these events yet many, from Schindler’s List to varied adaptations of Anne Frank’s story to X-Men have found ways to elaborate on, significantly, the scale of events and the breadth of their impact.

Audiences are not ill-informed nor should such a presumption be made; viewers will likely have varying understandings of the historical events surrounding Jojo Rabbit. Yet to the extent that the film either seeks to inform on the breadth of hate’s consequence and relative to this underline how the horrific mentalities depicted throughout bear broader consequence through crucial reference to wider historical context, it falls short.

Naysayers of such a view will likely bring up Brooks’ deservedly beloved classic and still raucous hallmark of far-right lampooning The Producers, among this author’s very favourite films, and musicals; excepting of course the terrible 2005 adaptation. Yet there’s a crucial distinction to be drawn here. Brooks, statedly, will gleefully mock the Nazis but fell short of conveying the Shoah as the basis for any comedy; famously criticising Roberto Benigni’s Life is Beautiful.

This author does not share the view that anything should necessarily be off limits for creatives and that there can be catharsis (if managed effectively and as seen in respects of Waititi’s latest) in sourcing humour in even the most dire of circumstances. Benigni, in what was the third and weakest of three acts, nonetheless accounted for a necessarily reckonable extent of the scale of his subject, a matter significantly confined to being explored this time around through McKenzie’s character.

If you’re going to take the piss out of Nazis that’s great and you’ve got a lot to work with, you just have to be funny and to resonate not neglect to ground or effectively relate the humour to its less than fictional ramifications, something for instance the very overrated ‘Allo ‘Allo! didn’t always muster. Waititi achieves such in some of the jumbled approaches to comedy, yet most ably manages same in the asides divorced from typical slapstick humour which could just as well have been transplanted to many a more dramatic picture.

If you’re going to broach the Shoah with comedy however, there’s a necessity to relate and ground the breadth of it’s reach and consequence to extents feasible in film if simply for the humour to be effective and to resonate for any regardless of their level of knowledge of the occurrences or lack thereof; with Jojo Rabbit we don’t quite get there.

On the matter of audiences ‘getting it,’ much of the dialogue between Elsa and Jojo is replete with ‘gotcha’ moments and platitudes; in their simplicity undermining what could have been more palpable, realistic encounters for those watching and intended by the creators to be either affirmed or swayed in their views. The arc of Rockwell’s character and the most interesting herein, broadly comparable to Jojo’s as he too begins to see the faults in the Nazis’ extremism, is comparably better handled. With both characters quite literally scarred and consequentially soon rejected by their contemporaries, the subplot centring on Rockwell’s Klenzendorf, too highlighting the persecution suffered by disabled and queer persons at the hands of the Third Reich, deploys an illiteral, viscerally impacting subtleness notably absent from less effective stretches.

To be clear, this author is not of the view that any filmmaker has a responsibility to educate, however serious the subject, rather than entertain. It’s just that you need to contextualise some subjects if their skewering is to resonate, regardless of how clued-in your audience might be, and imparting none of this is helped if you too blatantly spell out your point at various junctures.

Now; Waititi’s Hitler. Littered throughout, there’s a grand total of two scenes where it’s effective. The first; largely for its then novelty, and the last, for trying something different and uniquely dark. The rest of the appearances wreak of sketch comedy (the concept itself being ripe for a briefer run) stretched unnecessarily over two hours ala What We Do in the Shadows. Waititi’s performance isn’t bad, it’s simply that after the initial impact it becomes (with the exception of the final scene) one-note and non-essential, much like Roman Griffin Davis’ own turn which, while serviceable, is overshadowed by a conveyer belt of performers running rings around him.

Foremost among them is the very underrated Johansson, stealing the film in its easily best scene involving a brutish impersonation of an off-screen figure. A narrow second-best and likewise impacting sequence too involves Johansson, and a pair of shoes.

It is these moments, as good as they are, which underline the main problem above and beyond all else with Jojo Rabbit in that there are three different tones running interchangeably within. There’s Rockwell and Wilson doing their shticks (alongside a likewise excellent Stephen Merchant as a gangly gestapo), Waititi who is operating at a wholly different comic register and everything else which over and above comedy predominantly pursues drama.

Some of these dramatic moments are the film’s very best and could have been resplendent in many a more tonally-orientated picture irrespective of the genre(s) pursued, yet falter amidst refrains to varied comic tonalities which themselves don’t always land. For all the film’s faults there is regardless a simple and undeniable joy in seeing Nazis so belittled and moreover at the behest of those in a sustained effort of self-actualisation and catharsis to which many a viewer will relate.

There’s nothing wrong with pursuing the subjects this film does and those times one does get it wrong it doesn’t mean the flick is necessarily offensive nor is this one, but don’t expect everyone to queue up.

‘Jojo Rabbit,’ which premiered at the Jewish International Film Festival, is in cinemas from Boxing Day

on Film Fight Club

on Festevez

#xl#reviews#jojo rabbit#life is beautiful roberto benigni#roman griffin davis#sam rockwell#scarlett johannson#stephen merchant#taika waititi#thomasin mckenzie#jiff#jiff2019#jiff 2019#jewish international film festival#jewish international film festival 2019

0 notes

Text

Analysis: One Sure Thing About COVID-19: No Telling How Many People Have It

It has been nearly three months since the first cases of a new coronavirus pneumonia appeared in Wuhan, China, and it is now a global outbreak. And yet, despite nearly 90,000 infections worldwide (most of them in China), the world still doesn’t have a clear picture of some basic information about this outbreak.

In recent weeks, a smattering of scientific papers and government statements have begun to sketch the outlines of the epidemic. The Chinese national health commission has reported that more than 1,700 medical workers in the country had contracted the virus as of Feb 14. (That’s alarming.) The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that some 80% of those infected have a mild illness. (That’s comforting.) Last week, a joint World Health Organization-China mission announced that the death rate in Wuhan was 2% to 4%, but only 0.7% in the rest of China — a difference that makes little scientific sense.

In recent days, the WHO has complained that China has not been sharing data on infections in health care workers. Last month, the editors of the journal Nature called on researchers to “ensure that their work on this outbreak is shared rapidly and openly.”

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

Sign Up

Please confirm your email address below:

Sign Up

Much more could be known and, in all likelihood, some scientists out there have good, if not definitive, answers. And yet, the lack of consistent, reliable and regularly updated information on the key measures of this outbreak is startling. In an era when we get flash-flood warnings on phones and weekly influenza statistics from every state, why is data on the new coronavirus so limited?

Science, politics and pride have all, in various ways, conspired to keep potentially vital, lifesaving knowledge under wraps. That is problematic at a time when more information is needed to be strategic about preparedness.

It began early in the course of the epidemic. On Dec. 30, a Chinese physician, Dr. Li Wenliang, posted on social media about a small number of people with unusual pneumonia. Though scientists in labs were already sequencing the virus, he was “warned and reprimanded” by local officials for rumor-mongering and the “illegal activity of publishing false information online.” (Li later died of the illness.)

There is a tradition in China (and likely much of the world) for local authorities not to report bad news to their superiors. During the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign by the Communist Party of China from 1958 to 1962, local officials reported exaggerated harvest yields even as millions were starving. More recently, officials in Henan province denied there was an epidemic of AIDS spread through unsanitary blood collection practices.

Indeed, even when Beijing urges greater attention to scientific reality, compliance is mixed. On Feb. 13, the Communist Party secretaries of Wuhan and Hubei provinces lost their jobs over their botched initial handling of the crisis. But damage had been done. As the virus was taking hold, doctors were not wearing proper protective equipment. Sick people, thinking they had just a cold, didn’t seek medical attention. And travelers continued to board cruise ships, spreading a new pathogen.

“Early on, management was less than optimal in Hubei and they’re paying for that now,” Dr. Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health who has been working in China and advising the Chinese government since the SARS outbreak, told me.

There were, of course, genuine barriers to understanding what exactly was happening in Wuhan: Cases of pneumonia are not unusual in winter, and there was no way to know there was a novel virus. (Lipkin’s group is working on building a new test that distinguishes between different causes of viral pneumonias, with a researcher headed to China next week for testing.)

Lest Americans feel it could never happen here, Lipkin pointed out that it took many months for health officials in the United States to acknowledge and recognize HIV as a new virus, despite gay men turning up at alarming rates with unusual pneumonias and skin cancers.

Scientific competition has also slowed reaction and response, experts fear — leading to the extraordinary editors’ plea in Nature. For a young researcher, a paper in Nature or the New England Journal of Medicine is gold in career currency. Scientific prestige may encourage perfecting data for peer review, but preparedness requires rapid dissemination of information.

While federal officials in the United States warn Americans to be ready for the virus, there are important aspects of its spread about which we have little information — even though they have likely been studied by scientists and officials in China, Japan and elsewhere. Scientists in various countries are presumably gathering large amounts of data day by day and the world deserves to see more of it.

“Were there patterns around infections, places, procedures? Maybe that is being collected and readied for the medical literature. But it would be hugely important to know,” said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which studies epidemics.

For example: Of the more than 1,700 health workers infected in China, did those infections occur before they knew to wear protective equipment? Were they doing procedures that might lead to exposure? Those answers would quell fears about how the virus spreads and how to protect front-line workers.

Likewise, hundreds of people tested positive aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship and were transferred to the hospital. But little public information has been released about what shape they were in. How many in the cohort were really sick, how many just had minor symptoms, and how many just needed isolation? Does the pattern of infection suggest a role for transmission via plumbing on the ship?

Finally, the world’s public health researchers need much more transparency about how officials are monitoring this epidemic. What exactly is China’s surveillance strategy among the general population? To gauge the actual death rate of COVID-19, researchers would need to know how many people actually have it, even if they have only mild symptoms. In-country surveillance may reveal a very large pool of people with mild or no symptoms at all.

Lipkin noted that because cases observed early in an epidemic are the most severe, early mortality estimates tend to be high. As more information comes out, the death rates are likely to fall. “We’re probably six months out from having a good picture, and when we do I’d guess the mortality will drop dramatically,” he said.

Compared with the situation in 2003, when it took about five months for the Chinese central government to publicly acknowledge a deadly crisis associated with SARS, the flow of information has clearly improved. But since then, travel and commerce between China and the rest of the world have increased manifold. The spread of information about emerging infectious diseases needs to keep up with that new reality.

Analysis: One Sure Thing About COVID-19: No Telling How Many People Have It published first on https://nootropicspowdersupplier.tumblr.com/

0 notes

Text

Analysis: One Sure Thing About COVID-19: No Telling How Many People Have It

It has been nearly three months since the first cases of a new coronavirus pneumonia appeared in Wuhan, China, and it is now a global outbreak. And yet, despite nearly 90,000 infections worldwide (most of them in China), the world still doesn’t have a clear picture of some basic information about this outbreak.

In recent weeks, a smattering of scientific papers and government statements have begun to sketch the outlines of the epidemic. The Chinese national health commission has reported that more than 1,700 medical workers in the country had contracted the virus as of Feb 14. (That’s alarming.) The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that some 80% of those infected have a mild illness. (That’s comforting.) Last week, a joint World Health Organization-China mission announced that the death rate in Wuhan was 2% to 4%, but only 0.7% in the rest of China — a difference that makes little scientific sense.

In recent days, the WHO has complained that China has not been sharing data on infections in health care workers. Last month, the editors of the journal Nature called on researchers to “ensure that their work on this outbreak is shared rapidly and openly.”

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

Sign Up

Please confirm your email address below:

Sign Up

Much more could be known and, in all likelihood, some scientists out there have good, if not definitive, answers. And yet, the lack of consistent, reliable and regularly updated information on the key measures of this outbreak is startling. In an era when we get flash-flood warnings on phones and weekly influenza statistics from every state, why is data on the new coronavirus so limited?

Science, politics and pride have all, in various ways, conspired to keep potentially vital, lifesaving knowledge under wraps. That is problematic at a time when more information is needed to be strategic about preparedness.

It began early in the course of the epidemic. On Dec. 30, a Chinese physician, Dr. Li Wenliang, posted on social media about a small number of people with unusual pneumonia. Though scientists in labs were already sequencing the virus, he was “warned and reprimanded” by local officials for rumor-mongering and the “illegal activity of publishing false information online.” (Li later died of the illness.)

There is a tradition in China (and likely much of the world) for local authorities not to report bad news to their superiors. During the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign by the Communist Party of China from 1958 to 1962, local officials reported exaggerated harvest yields even as millions were starving. More recently, officials in Henan province denied there was an epidemic of AIDS spread through unsanitary blood collection practices.

Indeed, even when Beijing urges greater attention to scientific reality, compliance is mixed. On Feb. 13, the Communist Party secretaries of Wuhan and Hubei provinces lost their jobs over their botched initial handling of the crisis. But damage had been done. As the virus was taking hold, doctors were not wearing proper protective equipment. Sick people, thinking they had just a cold, didn’t seek medical attention. And travelers continued to board cruise ships, spreading a new pathogen.

“Early on, management was less than optimal in Hubei and they’re paying for that now,” Dr. Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health who has been working in China and advising the Chinese government since the SARS outbreak, told me.

There were, of course, genuine barriers to understanding what exactly was happening in Wuhan: Cases of pneumonia are not unusual in winter, and there was no way to know there was a novel virus. (Lipkin’s group is working on building a new test that distinguishes between different causes of viral pneumonias, with a researcher headed to China next week for testing.)

Lest Americans feel it could never happen here, Lipkin pointed out that it took many months for health officials in the United States to acknowledge and recognize HIV as a new virus, despite gay men turning up at alarming rates with unusual pneumonias and skin cancers.

Scientific competition has also slowed reaction and response, experts fear — leading to the extraordinary editors’ plea in Nature. For a young researcher, a paper in Nature or the New England Journal of Medicine is gold in career currency. Scientific prestige may encourage perfecting data for peer review, but preparedness requires rapid dissemination of information.

While federal officials in the United States warn Americans to be ready for the virus, there are important aspects of its spread about which we have little information — even though they have likely been studied by scientists and officials in China, Japan and elsewhere. Scientists in various countries are presumably gathering large amounts of data day by day and the world deserves to see more of it.

“Were there patterns around infections, places, procedures? Maybe that is being collected and readied for the medical literature. But it would be hugely important to know,” said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which studies epidemics.

For example: Of the more than 1,700 health workers infected in China, did those infections occur before they knew to wear protective equipment? Were they doing procedures that might lead to exposure? Those answers would quell fears about how the virus spreads and how to protect front-line workers.

Likewise, hundreds of people tested positive aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship and were transferred to the hospital. But little public information has been released about what shape they were in. How many in the cohort were really sick, how many just had minor symptoms, and how many just needed isolation? Does the pattern of infection suggest a role for transmission via plumbing on the ship?

Finally, the world’s public health researchers need much more transparency about how officials are monitoring this epidemic. What exactly is China’s surveillance strategy among the general population? To gauge the actual death rate of COVID-19, researchers would need to know how many people actually have it, even if they have only mild symptoms. In-country surveillance may reveal a very large pool of people with mild or no symptoms at all.

Lipkin noted that because cases observed early in an epidemic are the most severe, early mortality estimates tend to be high. As more information comes out, the death rates are likely to fall. “We’re probably six months out from having a good picture, and when we do I’d guess the mortality will drop dramatically,” he said.

Compared with the situation in 2003, when it took about five months for the Chinese central government to publicly acknowledge a deadly crisis associated with SARS, the flow of information has clearly improved. But since then, travel and commerce between China and the rest of the world have increased manifold. The spread of information about emerging infectious diseases needs to keep up with that new reality.

Analysis: One Sure Thing About COVID-19: No Telling How Many People Have It published first on https://smartdrinkingweb.weebly.com/

0 notes

Text

Analysis: One Sure Thing About COVID-19: No Telling How Many People Have It

It has been nearly three months since the first cases of a new coronavirus pneumonia appeared in Wuhan, China, and it is now a global outbreak. And yet, despite nearly 90,000 infections worldwide (most of them in China), the world still doesn’t have a clear picture of some basic information about this outbreak.

In recent weeks, a smattering of scientific papers and government statements have begun to sketch the outlines of the epidemic. The Chinese national health commission has reported that more than 1,700 medical workers in the country had contracted the virus as of Feb 14. (That’s alarming.) The Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that some 80% of those infected have a mild illness. (That’s comforting.) Last week, a joint World Health Organization-China mission announced that the death rate in Wuhan was 2% to 4%, but only 0.7% in the rest of China — a difference that makes little scientific sense.

In recent days, the WHO has complained that China has not been sharing data on infections in health care workers. Last month, the editors of the journal Nature called on researchers to “ensure that their work on this outbreak is shared rapidly and openly.”

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

Sign Up

Please confirm your email address below:

Sign Up

Much more could be known and, in all likelihood, some scientists out there have good, if not definitive, answers. And yet, the lack of consistent, reliable and regularly updated information on the key measures of this outbreak is startling. In an era when we get flash-flood warnings on phones and weekly influenza statistics from every state, why is data on the new coronavirus so limited?

Science, politics and pride have all, in various ways, conspired to keep potentially vital, lifesaving knowledge under wraps. That is problematic at a time when more information is needed to be strategic about preparedness.

It began early in the course of the epidemic. On Dec. 30, a Chinese physician, Dr. Li Wenliang, posted on social media about a small number of people with unusual pneumonia. Though scientists in labs were already sequencing the virus, he was “warned and reprimanded” by local officials for rumor-mongering and the “illegal activity of publishing false information online.” (Li later died of the illness.)

There is a tradition in China (and likely much of the world) for local authorities not to report bad news to their superiors. During the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign by the Communist Party of China from 1958 to 1962, local officials reported exaggerated harvest yields even as millions were starving. More recently, officials in Henan province denied there was an epidemic of AIDS spread through unsanitary blood collection practices.

Indeed, even when Beijing urges greater attention to scientific reality, compliance is mixed. On Feb. 13, the Communist Party secretaries of Wuhan and Hubei provinces lost their jobs over their botched initial handling of the crisis. But damage had been done. As the virus was taking hold, doctors were not wearing proper protective equipment. Sick people, thinking they had just a cold, didn’t seek medical attention. And travelers continued to board cruise ships, spreading a new pathogen.

“Early on, management was less than optimal in Hubei and they’re paying for that now,” Dr. Ian Lipkin, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health who has been working in China and advising the Chinese government since the SARS outbreak, told me.

There were, of course, genuine barriers to understanding what exactly was happening in Wuhan: Cases of pneumonia are not unusual in winter, and there was no way to know there was a novel virus. (Lipkin’s group is working on building a new test that distinguishes between different causes of viral pneumonias, with a researcher headed to China next week for testing.)

Lest Americans feel it could never happen here, Lipkin pointed out that it took many months for health officials in the United States to acknowledge and recognize HIV as a new virus, despite gay men turning up at alarming rates with unusual pneumonias and skin cancers.

Scientific competition has also slowed reaction and response, experts fear — leading to the extraordinary editors’ plea in Nature. For a young researcher, a paper in Nature or the New England Journal of Medicine is gold in career currency. Scientific prestige may encourage perfecting data for peer review, but preparedness requires rapid dissemination of information.

While federal officials in the United States warn Americans to be ready for the virus, there are important aspects of its spread about which we have little information — even though they have likely been studied by scientists and officials in China, Japan and elsewhere. Scientists in various countries are presumably gathering large amounts of data day by day and the world deserves to see more of it.

“Were there patterns around infections, places, procedures? Maybe that is being collected and readied for the medical literature. But it would be hugely important to know,” said Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, which studies epidemics.

For example: Of the more than 1,700 health workers infected in China, did those infections occur before they knew to wear protective equipment? Were they doing procedures that might lead to exposure? Those answers would quell fears about how the virus spreads and how to protect front-line workers.

Likewise, hundreds of people tested positive aboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship and were transferred to the hospital. But little public information has been released about what shape they were in. How many in the cohort were really sick, how many just had minor symptoms, and how many just needed isolation? Does the pattern of infection suggest a role for transmission via plumbing on the ship?

Finally, the world’s public health researchers need much more transparency about how officials are monitoring this epidemic. What exactly is China’s surveillance strategy among the general population? To gauge the actual death rate of COVID-19, researchers would need to know how many people actually have it, even if they have only mild symptoms. In-country surveillance may reveal a very large pool of people with mild or no symptoms at all.

Lipkin noted that because cases observed early in an epidemic are the most severe, early mortality estimates tend to be high. As more information comes out, the death rates are likely to fall. “We’re probably six months out from having a good picture, and when we do I’d guess the mortality will drop dramatically,” he said.

Compared with the situation in 2003, when it took about five months for the Chinese central government to publicly acknowledge a deadly crisis associated with SARS, the flow of information has clearly improved. But since then, travel and commerce between China and the rest of the world have increased manifold. The spread of information about emerging infectious diseases needs to keep up with that new reality.

from Updates By Dina https://khn.org/news/analysis-coronavirus-infection-rate-unknown/

0 notes