#ghibelines

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

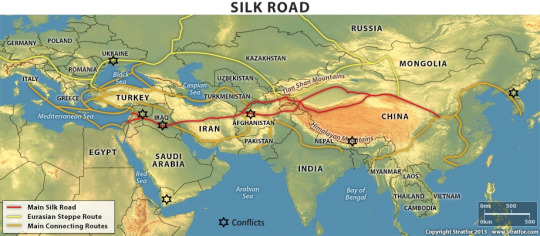

Photo

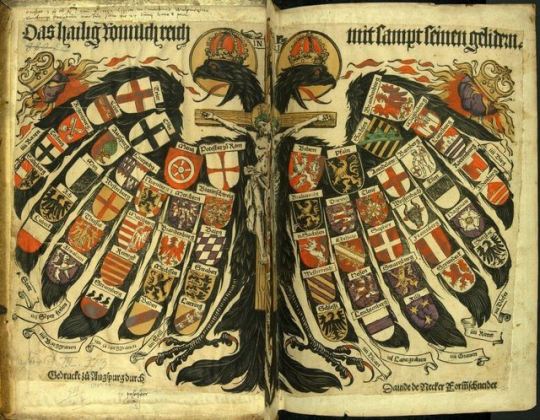

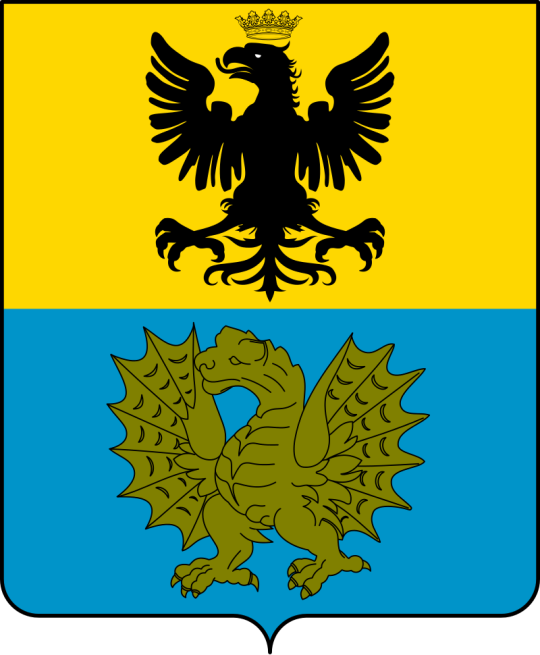

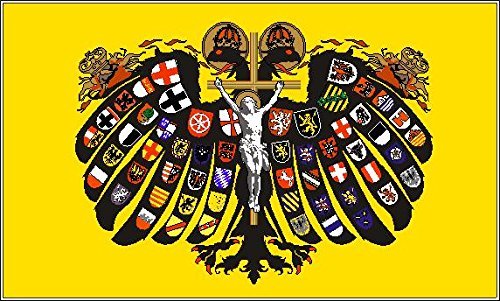

“The earliest depiction of the double-headed eagle can be found on ancient on Hittite monuments in central Anatolia. In the early 19th century, in Boğazkale, an old Hittite capital in modern-day Turkey...The double-headed eagle motif originally dates from c. 3800 BC. The Hittites had worshiped the double headed eagle as the King of Heaven, who was also called the Hittite Bird of the Sun. The bird was their symbol to signify Hittite military power.”

”The bird bird appears in Lygash under the name of Imgig, and was the Sumerian symbol for the god of Lagash, Ninurta son of Enlil...the double-headed eagle, however, is not restricted to supporting deities, and also appears supporting human figures. This is an indication of the use of the eagle as a personal (or family) symbol...The Seliuk Turks referred to it as Hamca and among the Zuni it appeared as a highly conventionalized design, but still as a double-headed thunder bird, the Sikyatki.”

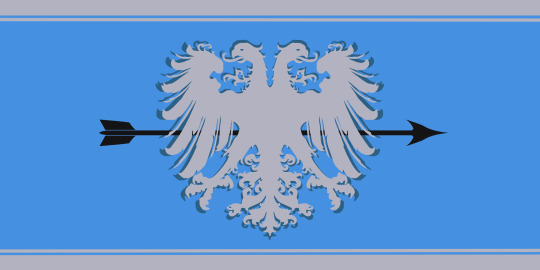

”The double-headed eagle has been used as an emblem by countries, nations, and royal houses in Europe since the early medieval period. Notable examples include the Byzantine House of Palaiologos, the Holy Roman Empire, the House of Habsburg, and the Ruriks and Romanovs of Russia. The symbol often appears on countries’ coats of arms and flags. The emblem was adopted by the Russians, Poles, Serbians, Prussians, Austrians and Saxons. It was used as a private seal and as arms in Germany, Spain, France, Netherlands, England, and Russia.”

(via Mystery Of The Ancient Double-Headed Eagle Symbol | Locklip)

Double Headed Eagle iconology of Byzantium

“Greek scholars have tried to make links with ancient symbols: the eagle was a common design representing power in ancient city-states, while there was an implication of a "dual-eagle" concept...However, there is virtually no doubt that its origin is a blend of Roman and Eastern influences. Indeed, the early Byzantine Empire inherited the Roman eagle (extended wings, head facing right) as an imperial symbol.”

“[T]he church of Greece kept, and is to this date still using Byzantine flags with the eagle, usually black on yellow/gold background. But after the Ottoman conquest this symbol also found its way to a "new Constantinople" (or Third Rome), i.e. Moscow. Russia, deeply influenced by the Byzantine Empire, saw herself as its heir and adopted the double-headed eagle as its imperial symbol. It was also adopted by the Serbs, the Montenegrins, the Albanians and a number of Western rulers, most notably in Germany and Austria.”

“The first mention of a double-headed eagle in the West dates from 1250 in a roll of arms of Matthew of Paris for Emperor Friedrich II. Theodore II Laskaris chose it for his symbol as Emperor (Empire of Nicaea), taking it to symbolize his state's claims to all the Byzantine Empire's former domains, both European (West) and Asian (East)... After the recapture of Constantinople and the restoration of the Byzantine Empire, the symbol was used as an emblem of the imperial family, but it is uncertain whether it was the official emblem of the Empire.”

“The double-headed eagle became the standard of the Seljuk Turks with the crowning of Toghrül (meaning "Eagle") Beg at Mosul in 1058 as "King of the East and the West" and was much used afterwards. The Sultans of Rum, Ala ad-Din Kay Qubadh I (1220-1237) and his son Kay Khusrau II (1237-1246) used the bicephalous eagle in their standards, and the motif was also found on tissues, cut stones, mural squares, and Koran holders.”

(via Double Headed Eagle iconology of Byzantium | Kythera Family blog)

The double-headed eagle of the Third Rome

“When looking carefully, you can distinguish 9 coats of arms on the eagle. However, in most cases, these shields are printed so tiny that few details can be revealed. The center shield on the eagle's chest is the one with the arms of Moscow. Then, in clockwise order starting from the heads, we see the arms of [Khanate of] Astrakhan, [Khanate of] Siberia, [Kingdoms & Principalities of] Georgia, [Grand Duchy of] Finland, [Grand Principalities of] Kiev-Vladimir-Novgorod, [Khanate of] Taurica, [Kingdom of] Poland and [Khanate of] Kazan...this double-headed eagle represents about 500 years of Russian imperial history.”

(via The double-headed eagle of the Third Rome | Franky’s Scripophily BlogSpot)

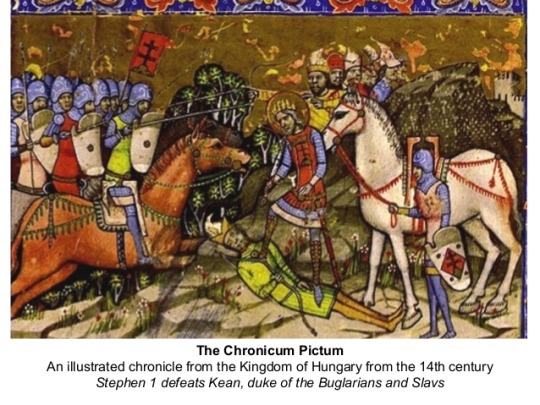

Kiev and the Byzantine Legacy in Russia

“The history of Kiev begins under the rule of the Rus. The Rus (also known as Varangians) were original Vikings who began to trade along the Volga River and later the Dnieper River. They establish several principalities centered on cities like Novgorod and later Kiev...Vladimir was also among the rulers of Kiev who gave military assistance to the Byzantines, leading to the formation of the Varangian Guard...Saint Sophia's Cathedral in Kiev, which dates to the early 11th century. It was designed rival Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, thus symbolizes Kiev as the 'new Constantinople'. There was even a Golden Gate in Kiev, named after the famous Golden Gate of Constantinople. In addition, the Kiev Monastery of the Caves date to 1051 and were influential in the spread of Orthodox thought.“

“As the Byzantine Empire was slowly dying, Moscow began to grow in power. The Metropolitan of Kiev moved to Moscow in the 14th century as the Tatars undermined the power of Kiev. Ivan III (1440-1505), the Grand Prince of Moscow, ended the dominance of the Golden Horde in Russia, and became to expand his own power. In 1472, He married Sophia Palaiologina, the niece of the last Byzantine Emperor, after the fall of Constantinople. He would then claim that Moscow was the “Third Rome” and by the end of the 16th century, the Metropolitan of Moscow claimed the title of patriarch. The title Tsar also reflects this claim to be the successor of Constantinople. In fact, the Russian Empire’s symbol was the Byzantine Double Eagle until the Soviet’s overthrew Tsar Nicholas II. This symbol has since returned after the fall of the Soviet Union.“

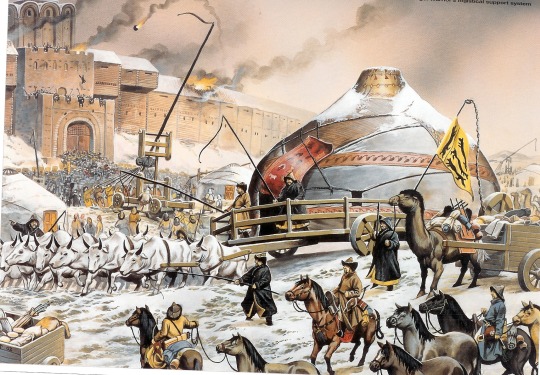

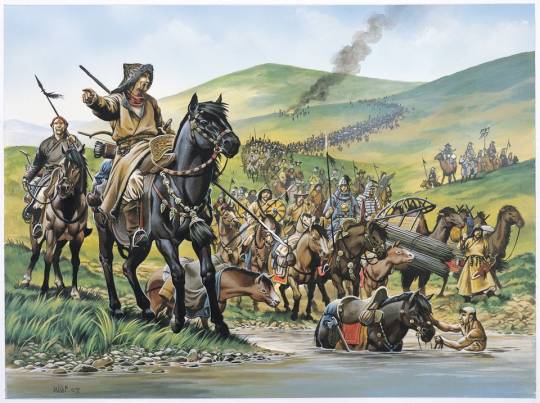

Mongol-Papal Encounter: Letter Exchange between Pope Innocent IV and Güyük Khan in 1245-1246

“By the late 1230s, Mongol armies had begun raiding parts of Russia and eastern Europe. Between 1236 and 1242, these military campaigns–commanded by Subutai (d. 1248), Batu Khan (d. 1255), and Berke (d. 1266), among others–had wrought major devastation across Russia, Poland, Hungary and the Balkans. The cities of Kiev, Pereyaslavl, Chernihiv, Lublin, and other major population centers in eastern and central Europe were sacked and their populations massacred.”

“The defeats of the Polish forces at the Battle of Liegnitz/Legnica (April 9th 1241) and the Hungarian military at the Battle of Mohi (April 11th 1241) opened up most of the Balkans and Central Europe to Mongol raids, leading to even more destruction, displacement and massacres. These alarming developments shook the foundations of Latin Christendom. Although the Mongols withdrew from most of the Balkans and east-central Europe soon after”

(via Mongol-Papal Encounter: Letter Exchange between Pope Innocent IV and Güyük Khan in 1245-1246 | Ballandalus blog)

Borjigin

“A Borjigin or Borjigid is a member of the sub-clan, which started with Yesugei (but the Secret History of the Mongols makes it go back to Yesugei's ancestor Bodonchar), of the Kiyat clan. Yesugei's descendants were thus said to be Kiyat-Borjigin. The senior Borjigid provided ruling princes for Mongolia and Inner Mongolia until the 20th century. The clan formed the ruling class among the Mongols and some other peoples of Central Asia and Eastern Europe.”

“The Borjigin family ruled over the Mongol Empire from the 13th to 14th century. The rise of Genghis (Chingis) narrowed the scope of the Borjigid-Kiyad clans sharply. This separation was emphasized by the intermarriage of Genghis's descendants with the Barlas, Baarin, Manghud and other branches of the original Borjigid.”

”In the western regions of the Empire, the Jurkin and perhaps other lineages near to Genghis's lineage used the clan name Kiyad but did not share in the privileges of the Genghisids. The Borjigit clan had once dominated large lands stretching from Java to Iran and from Indo-China to Novgorod. In 1335, with the disintegration of the Ilkhanate in Iran, the first of numerous non-Borjigid-Kiyad dynasties appeared. Established by marriage partners of Genghisids, these included the Suldus Chupanids, Jalayirids in the Middle East, the Barulas dynasties in Chagatai Khanate and India, the Manghud and Onggirat dynasties in the Golden Horde and Central Asia, and the Oirats in western Mongolia.In 1368, under Toghun Temür, the Yuan dynasty was overthrown by the Ming dynasty in China but members of the family continued to rule over Mongolia homeland into the 17th century, known as the Northern Yuan dynasty.”

“After the breakup of the Golden Horde, the Khiyat continued to rule the Crimea and Kazan until the late 18th century. They were annexed by the Russian Empire and the Chinese...The Qing dynasty respected the Borjigin family and the early emperors married the Hasarid Borjigids of the Khorchin. Even among the pro-Qing Mongols, traces of the alternative tradition survived. Aci Lomi, a banner general, wrote his History of the Borjigid Clan in 1732–35. The 18th century and 19th century Qing nobility was adorned by the descendants of the early Mongol adherents including the Borjigin.”

“Genghis Khan founded the Mongol Empire in 1206. His grandson, Kublai Khan, after defeating his younger brother Ariq Böke, founded the Yuan dynasty in China in 1271. The dynasty was overthrown by the Ming dynasty during the reign of Toghaghan-Temür in 1368, but it survived in Mongolia homeland, known as the Northern Yuan dynasty.”

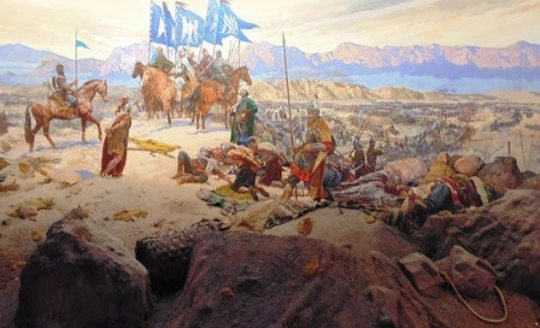

Bahri dynasty

“The Bahri dynasty or Bahriyya Mamluks was a Mamluk dynasty of mostly Cuman-Kipchak Turkic origin that ruled the Egyptian Mamluk Sultanate from 1250 to 1382. They followed the Ayyubid dynasty, and were succeeded by a second Mamluk dynasty, the Burji dynasty."

Burji dynasty

“From 1250 Egypt had been ruled by the first Mamluk dynasty, the mostly Cuman-Kipchak Turkic Bahri dynasty. In 1377 a revolt broke out in Syria which spread to Egypt...Barquq was proclaimed sultan in 1382, ending the Bahri dynasty...Permanently in power, he founded the Burji dynasty.”

House of Borghese

“Borghese is the surname of a princely family of Italian noble and papal background, originating as the Borghese or Borghesi in Siena, where they came to prominence in the 13th century holding offices under the commune. The head of the family, Marcantonio, moved to Rome in the 16th century and there, following the election (1605) of his son Camillo as Pope Paul V they rose in power and wealth. They were one of the leading families of the Black Nobilityand maintain close ties to the Vatican.”

Guelphs and Ghibellines

“The Guelphs and Ghibellines were factions supporting the Pope and the Holy Roman Emperor, respectively, in the Italian city-states of central and northern Italy. During the 12th and 13th centuries, rivalry between these two parties formed a particularly important aspect of the internal politics of medieval Italy.”

”The names were likely introduced to Italy during the reign of Frederick Barbarossa. When Frederick conducted military campaigns in Italy to expand imperial power there, his supporters became known as Ghibellines (Ghibellini). The Lombard League and its allies were defending the liberties of the urban communes against the Emperor's encroachments and became known as Guelphs (Guelfi). The Ghibellines were thus the imperial party, while the Guelphs supported the Pope. Broadly speaking, Guelphs tended to come from wealthy mercantile families, whereas Ghibellines were predominantly those whose wealth was based on agricultural estates.”

Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor

“In 1241–1242, the forces of the Golden Horde decisively defeated the armies of Hungary and Poland and devastated their countryside and all their unfortified settlements. King Béla IV of Hungary appealed to Frederick for aid, but Frederick, being in dispute with the Hungarian king for some time (as Bela had sided with the Papacy against him) and not wanting to commit to a major military expedition so readily, refused. He was unwilling to cross into Hungary, and although he went about unifying his magnates and other monarchs to potentially face a Mongol invasion, he specifically took his vow for the defense of the empire on "this side of the Alps."

”Frederick was aware of the danger the Mongols posed, and grimly assessed the situation, but also tried to use it as leverage over the Papacy to frame himself as the protector of Christendom. While he called them traitorous pagans, Frederick expressed an admiration for Mongol military prowess after hearing of their deeds, in particular their able commanders and fierce discipline and obedience, judging the latter to be the greatest source of their success. He called a levy throughout Germany while the Mongols were busy raiding Hungary. In mid 1241 Federick dispersed his army back to their holdfasts as the Mongols preoccupied themselves with the lands east of the Danube, attempting to smash all Hungarian resistance. He subsequently ordered his vassals to strengthen their defenses, adopt a defensive posture...A chronicler reports that Frederick received a demand of submission from Batu Khan at some time.”

“A letter written by Emperor Frederick II, found in the Regesta Imperii, dated to June 20, 1241, and intended for all his vassals in Swabia, Austria, and Bohemia, included a number of specific military instructions. His forces were to avoid engaging the Mongols in field battles, hoard all food stocks in every fortress and stronghold, and arm all possible levies as well as the general populace.

Mongol probing attacks materialised on the Holy Roman Empire's border states...A full-scale invasion never occurred, as the Mongols spent the next year pillaging Hungary before withdrawing. After the Mongols withdrew from Hungary back to Russia, Frederick turned his attention back towards Italian matters.”

Pope Innocent IV

“In 1245, Innocent IV issued bulls and sent an envoy in the person of Giovanni da Pian del Carpine (accompanied by Benedict the Pole) to the "Emperor of the Tartars". The message asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and stop his aggression against Europe. The Khan Güyük replied in 1246 in a letter written in Persian that is still preserved in the Vatican Library, demanding the submission of the Pope and the other rulers of Europe...two Mongolian envoys to the Papal seat in Lyon, Aïbeg and Serkis. In the letter Guyuk demanded that the Pope appear in person at the Mongol imperial headquarters, Karakorum in order that “we might cause him to hear every command that there is of the jasaq”.

Seventh Crusade

“In 1244, the Khwarezmians, recently displaced by the advance of the Mongols, took Jerusalem on their way to ally with the Egyptian Mamluks. This returned Jerusalem to Muslim control, but the fall of Jerusalem was no longer a crucial event to European Christians, who had seen the city pass from Christian to Muslim control numerous times in the past two centuries. This time, despite calls from the Pope, there was no popular enthusiasm for a new crusade. There were also many conflicts within Europe that kept its leaders from embarking on the Crusade.”

“Pope Innocent IV and Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor continued the papal-imperial struggle. Frederick had captured and imprisoned clerics on their way to the First Council of Lyon, and in 1245 he was formally deposed by Innocent IV. Pope Gregory IX had also earlier offered King Louis' brother, count Robert of Artois, the German throne, but Louis had refused. Thus, the Holy Roman Emperor was in no position to crusade. Béla IV of Hungary was rebuilding his kingdom from the ashes after the devastating Mongol invasion of 1241.”

Interregnum (Holy Roman Empire)

“The term Great Interregnum is occasionally used for the period between 1250 (death of Frederick II) and 1273 (accession of Rudolf I)...After the deposition of Frederick II by Pope Innocent IV in 1245...in 1273, Rudolf I of Germany, a minor pro-Staufen count, was elected. He was the first of the Habsburgs to hold a royal title, but he was never crowned emperor. After Rudolf's death in 1291, Adolf and Albert were two further weak kings who were never crowned emperor...Sigismund (r. 1411 – 1437) was crowned emperor in 1433, but only with Frederick III (r. 1452 – 1493), the second emperor of the House of Habsburg, did the Holy Roman Emperor return to an unbroken succession of emperors (with the exception of Charles VII all of the House of Habsburg) until its dissolution in 1806.”

Franco-Mongol alliance

“European attitudes began to change in the mid-1260s, from perceiving the Mongols as enemies to be feared, to potential allies against the Muslims. The Mongols sought to capitalize on this, promising a re-conquered Jerusalem to the Europeans in return for cooperation. Attempts to cement an alliance continued through negotiations with many leaders of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Persia, from its founder Hulagu through his descendants Abaqa, Arghun, Ghazan, and Öljaitü, but without success. The Mongols invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in attempts at joint operations with the Franks, but the considerable logistical difficulties involved meant that forces would arrive months apart, never able to coordinate activities in any effective way...the Egyptian Mamluks successfully recaptured all of Palestine and Syria from the Crusaders.”

“Christian kings began to prepare for a new crusade (the Seventh Crusade), declared by Pope Innocent IV in June 1245 at the First Council of Lyon. The loss of Jerusalem caused some Europeans to look to the Mongols as potential allies of Christendom, provided the Mongols could be converted to Western Christianity. In March 1245, Pope Innocent IV had issued multiple papal bulls, some of which were sent with an envoy, the Franciscan John of Plano Carpini, to the "Emperor of the Tartars". In a letter now called the Cum non solum, Pope Innocent expressed a desire for peace, and asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and to stop killing Christians. However, the new Mongol Great Khan Güyük, installed at Karakorum in 1246, replied only with a demand for the submission of the pope, and a visit from the rulers of the West in homage to Mongol power:”

Hohenstaufen

“The Hohenstaufen also known as Staufer, were a dynasty of German kings (1138–1254) during the Middle Ages. Before ascending to the kingship, they were Dukes of Swabia from 1079. As kings of Germany, they had a claim to Italy, Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire. Three members of the dynasty—Frederick I (1155), Henry VI (1191) and Frederick II (1220)—were crowned emperor. Besides Germany, they also ruled the Kingdom of Sicily (1194–1268) and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1225–1268) [succeeded by the House of Habsburg in 1268]”

House of Habsburg

“The House of Habsburg and alternatively called the House of Austria was one of the most influential and distinguished royal houses of Europe. The throne of the Holy Roman Empire was continuously occupied by the Habsburgs from 1438 until their extinction in the male line in 1740. The house also produced emperors and kings of Bohemia, Hungary, Croatia, Galicia, Portugal and Spain with their respective colonies, as well as rulers of several principalities in the Netherlands and Italy.”

“The Habsburg Empire was never composed of a single unified and unitary state as Bourbon France, Hohenzollern Germany, or Great Britain was. It was made up of an accretion of territories that owed their historic loyalty to the head of the house of Habsburg as hereditary lord. The Habsburgs had mostly married the heiresses of these territories, most famously of Spain and the Netherlands. They used their coats of arms then as a statement of their right to rule all these territories."

Rudolf I of Germany

“Rudolf I, also known as Rudolf of Habsburg was Count of Habsburg from about 1240 and King of Germany from 1273 until his death.Rudolf's election marked the end of the Great Interregnum in the Holy Roman Empire after the death of the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II in 1250.

The disorder in Germany during the interregnum after the fall of the Hohenstaufen dynasty afforded an opportunity for Count Rudolf to increase his possessions. His wife was a Hohenberg heiress; and on the death of his childless maternal uncle Count Hartmann IV of Kyburg in 1264, he also seized his valuable estates.”

Kyburg family

“Kyburg also Kiburg was a noble family of grafen (counts) in the Duchy of Swabia, a cadet line of the counts of Dillingen, who in the late 12th and early 13th century ruled the County of Kyburg, corresponding to much of what is now Northeastern Switzerland.The family was one of the four most powerful noble families in the Swiss plateau beside the House of Habsburg, House of Zähringen and the House of Savoy during 12th century. With the extinction of the Kyburg family's male line in 1264, Rudolph of Habsburg laid claim to the Kyburg lands and annexed them to the Habsburg holdings, establishing the line of "Neu-Kyburg", which was in turn extinct in 1417.”

“In 1250/51 the childless Hartmann IV gave the western part of the property with the center of Burgdorf to his nephew Hartmann V. As a result, Hartmann V, who was supported by the Habsburgs, came into conflict repeatedly with the growing city-state of Bern. His uncle had to step in often to keep the peace. When Hartmann V died in 1263, Count Rudolf von Habsburg became the guardian of Hartmann's daughter Anna, and also took over the administration of the western section. In 1264, after the death of Hartman IV, Rudolf stepped in to control the eastern half as well. Though this brought him into conflict with the claims by the widow Margaret of Savoy and her family.”

”Anna, daughter of Hartmann V, married Eberhard I of Habsburg-Laufenburg. This marriage was intended to secure Habsburg interests in Aargau (Argovia) against Savoy. The son of Eberhard and Anna, Hartmann I (1275–1301) again called himself "of Kyburg". His line came to be known as that of Neu-Kyburg or Kyburg-Burgdorf, persisting until 1417.”

House of Borgia

“The House of Borgia was an Italo-Spanish noble family, which rose to prominence during the Italian Renaissance. They were from Aragon, the surname being a toponymic from the town of Borja, then in the Crown of Aragon, in Spain.The Borgias became prominent in ecclesiastical and political affairs in the 15th and 16th centuries, producing two popes: Alfons de Borja, who ruled as Pope Callixtus III during 1455–1458, and Rodrigo Lanzol Borgia, as Pope Alexander VI, during 1492–1503.”

Name of Turkey

“The English name Turkey, now applied to the modern Republic of Turkey, is historically derived (via Old French Turquie) from the Medieval Latin Turchia, Turquia. It is first recorded in Middle English (as Turkye, Torke, later Turkie, Turky), attested in Chaucer, ca. 1369. The Ottoman Empire was commonly referred to as Turkey or the Turkish Empire

The English name of Turkey (from Medieval Latin Turchia/Turquia) means "land of the Turks"...The phrase land of Torke is used in the 15th-century Digby Mysteries. Later usages can be found in the Dunbar poems, the 16th century Manipulus Vocabulorum ("Turkie, Tartaria")...The medieval Greek and Latin terms did not designate the same geographic area now known as Turkey. Instead, they were mostly synonymous with Tartary, a term including Khazaria and the other khaganates of the Central Asian steppe, until the appearance of the Seljuks and the rise of the Ottoman Empire in the 14th century...The Arabic cognate Turkiyya (Arabic: تركيا) in the form Dawla al-Turkiyya (State of the Turks) was historically used as an official name for the medieval Mamluk Sultanate which covered Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Hejaz and Cyrenaica.”

What’s the Word for Turkey in Turkish?

“The word for turkey in Turkish is hindi.What? OK, so what’s the Hindi word for turkey?Turns out that the word for turkey in Hindi is टर्की. And that, if you don’t know Devanagari, is transcribed ṭarkī in the Latin alphabet.

Turkeys are native to the Americas, but the Europeans first encountering them thought that they looked like a kind of guinea fowl, another large, ungainly, colorful-faced kind of bird. Now, guinea fowl were also called turkey fowl, but that’s because they actually had a legitimate connection to Turkey the country: Europeans received most of their guinea fowl imported via Turkey...the first turkeys brought to Europe also generally came via Turkey: The birds had originally been domesticated by the Aztecs and were brought to Europe by Spanish conquistadores, who traded them to the rest of the continent via North Africa.

Japanese and Korean call it the equivalent of “seven-faced bird,” Abkhazian and other languages in the Caucasus call it “blue bird,” and Thai and Urdu call it “elephant chicken” or “elephant trunk chicken.”

(via What’s the Word for Turkey in Turkish? | Slate)

#turkey#silkroad#chainofcommerce#noblemerchantclans#ambasadorsorspies#kiyat#borjigin#burji#borgia#borghese#kiburg#ghibelines#holyromanempire#rudolfofhapsburg#hapsburgdynasty#vladtheimpaler#transylvania#house of saxe-coburg and gotha#popeinnocentiv#guyukkhan#mongolultimatum#marriagealliance#tributetax#wagewarfortribute#secrethistoryofthemongols#doubleheadedeagle#goldenhorde#goldenorder

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

the wiki page for Dante focuses mostly on his role in the Guelph/Ghibeline conflict & not on his role in the communes which it doesn’t seem to mention. You get the impression from the wiki that he entered politics out of passionate feeling, while the Britannica article makes it pretty much secondary: he became involved in the conflict (between pro- and anti-papal Geulphs) as an expression of his commune’s already existing resistance to the Pope.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Favorite Historical Event-That-Should-Be-a-Movie

As I was doing research for this post, I came across a historical event that immediately added itself to my list of historical figures and events that should be movies already. In this case, the wedding of Lionel of Clarence to Violante Visconti in 1368.

Ok, maybe I should explain who those people were. Lionel of Clarence, also known as Lionel of Antwerp was the second surviving son of Edward III, and thus a royal duke (second in line for the throne of England after the future Richard II), as well as Earl of Ulster and King’s Lieutenant of Ireland. Violante Visconti was the daughter of Galeazzo II Visconti, the Lord of Milan and Pavia, who gave her Alba, Mondovi, Kenites, Cherasco, and Demonte as her patrimony.

(The lovely couple. FYI, Lionel was almost seven feet, a very tall boi indeed by 14th century standards.)

Their wedding was part of a truly staggering bit of late Medieval diplomacy. As part of his broader effort to win the Hundred Years War, Edward III wanted to marry his son Edmund of Langley (the ancestor of the House of York) to Margaret of Flanders, who was an heiress and a half, inheriting the counties of Flanders, Burgundy, Nevers, Rethel, and Artois. This marriage would greatly strengthen England’s position in the Low Countries by directly incorporating the sometimes unreliable Burgundians into their continental empire. The problem was that Edmund and Margaret were related, and Urban V was dragging his heels on granting a dispensation.

Edward decided to jog the Pope’s elbow by arranging a marriage between his second son and the Duke of Milan, who was not only the conqueror of Pavia, but also the Imperial Vicar (the Holy Roman Emperor’s man in Italy) and thus the chief enemy of the Pope in the Guelph-Ghibeline Wars. And since Milan was the great power of northwestern Italy (especially after Duke Galeazzo married Bianca of Savoy), this also placed the Visconti in a position to threaten Valois France’s southern border. In return for the Visconti’s aid against France, Edward in turn promised to support Milan’s bid for hegemony in Italy:

For Lionel his sonne with theim to send The duke his doughter of Melayn for to wed Promysing then hym so to recommend That of Itale the rule sholde all be led By hym and his frendes of Italye bred.

So already we have a marriage that could have potentially changed the course of European history in several ways:

It could have dramatically reshaped the Hundred Years War, allowing England to invade Valois France from the south up through the Loire valley, and then push west to link up with Aquitaine. At the very least, the Valois would have had to hold back troops to guard their backs, which would have weakened their attacks on Brittany, Normandy, and Aquitaine.

If the marriage had resulted in a male heir, it could have entirely prevented the Wars of the Roses. See, when Richard II was deposed, Henry Bolingbroke claimed the throne of England as the son of John of Gaunt, the third son of Edward III, and thus gave rise to the House of Lancaster. The Yorkists descended from the male line through Edmund of Langely, the fourth son, which was something of a problem, so instead they claimed their right to rule from Lionel of Clarence through his daughter Philippa, who married Edmund Mortimer the Earl of March, and thus gave rise to the Mortimer claim. However, if there’s an male heir of the House of Clarence, Henry Bolingbroke might not become king and the Yorkists certainly couldn’t have claimed to come before the Lancastrians.

In turn, the marriage would have given England a claim on the Duchy of Milan, which could have dramatically changed the course of Renaissance Italian history. See, one of the major fulcrums of the Italian Wars between France and Spain was Louis XII’s claim to the Duchy of Milan through his grandmother Valentina Visconti (man, the Visconti loved alliteration!), which he argued outranked the Sforza’s claim through Bianca Maria, the natural daughter of the last Visconti Duke of Milan. But if England has a preceding claim to Milan through Violante, the wars might go in a very different direction.

But enough about European politics, let’s talk about OTT medieval weddings. Lionel traveled to Milan in style, with 457 knights and squires and 1280 squires, which required a fleet of 52 ships to transport him to Calais. Despite the whole hundred-year-war business, Charles V feted the bridegroom with gifts worth 20,000 florins (£1 million in today’s money). Along the way, Lionel hired Sir John Hawkwood, the legendary English condotierri, both to serve as his escort and implicitly as England’s contribution to Milan’s wars against the Papal States.

The wedding ceremony was carried out at the Church of Santa Maria Maggiori, the future Cathedral of Milan, and celebrated outdoors, so that the people of Milan could witness the magnificence. The banquet was thirty courses of meat and fish on gilt plate, with wedding gifts of war horses, hounds and hawks, and full suits of armor paraded in between the courses. But to me, the main attraction is the guest list. To show everyone that they weren’t just medieval warlords but men of culture, both the groom and bride’s party brought some of the brighest lights of European culture to the party. The English brought Geoffrey Chaucer and the chronicler and Arthurian poet Jean Froissart; not to be outdone, the Italians responded by getting Petrarch himself, arguably the father of Humanism, the modern Italian language, and the Renaissance itself, to show up for a free meal. I’m not usually one for wanting to have lived in the past, but I’d find it very hard to turn down a seat at that dinner table, just to watch Chaucer take the piss out of Froissart’s chivalric romance while Petrarch argues for an entirely new philosophy and aesthetic.

And just to add some spice, it all ends in tragedy. Lionel, an exceedingly healthy young man, dies five months later, with his deputy Edward le Despenser claiming that Galeazzo had poisoned his son-in-law, perhaps in order to get out of having to pay a stupendous dowry of 100,000 florins (£5.5 million in todays money). Le Despenser was so pissed off that he hired Sir John Hawkwood to hold the towns in the Piedmont that had been given to Lionel in the marriage, and to make war on the Visconti.

Whether Lionel was in fact poisoned - it’s worth noting that Violante’s second husband was in fact assassinated by the Visconti in order to get their hands on Monferrato, and her third husband (a Visconti cousin) was imprisoned and murdered by her brother in order to solidify his control over Milan - and indeed, whether he was murdered by the Visconti to get out of a debt or by agents of the Pope to thwart the Visconti and the Planagenets, we’ll never know.

However, it’d make a hell of an Altmanesque ensemble movie, with dynasties scheming and dreaming and coming to nothing, while cultural giants dispute platonic love versus sex and Christian virtue versus Humanism, and professional mercenaries are just there looking to get paid.

60 notes

·

View notes

Note

Guelph or Ghibeline?

i won’t suck your dick, church

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Suggested the idea to Philip

The arrival of messengers from Alexis corresponding with the collection of the crusading army appears at a very early period to have suggested the idea to Philip that the crusade might be made use of, under the pretext at least of assisting his brother-in-law. Philip had, however, selfish reasons which disposed him to help young Alexis. He seems to have persuaded himself that he had a right to the imperial throne of the East through his wife, and one of his dreams was that it might be possible to unite the two cares of the New and the Elder Nome in his own person. Thus the indignation which lie had a right to feel at the deposition and imprisonment of his wife’s father urged him to a course which coincided with that which his own ambition would dictate. Add to this that the disastrous result of the last crusade had been most keenly felt in Germany, and that any movement against the empire in the East was sure to be popular with his own subjects, and we see that the motives which urged Philip to assist young Alexis were exceedingly strong.

Crusade into a weapon against

If he could help him by turning the crusade into a weapon against the reigning emperor in Constantinople, lie would at the same time succeed in recovering the allegiance of those of his own subjects whom the pope’s excommunication had caused to waver. He could let the pope see that he was more powerful than his rival, and even Innocent might think it well to side with the stronger claimant. His own power would be enormously increased. He might be not only the triumphant leader of the Ghibelin party, but lord of the East and of the West.

Impelled by such motives, the appointment of Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, to the command of the crusading army on the death, in May, 1201, of Theobald of Champagne, supplied the instrument he required. If Boniface could be induced to act with him, a successful attack might be made on Constantinople, and his plans appeared assured of success.

0 notes

Photo

Suggested the idea to Philip

The arrival of messengers from Alexis corresponding with the collection of the crusading army appears at a very early period to have suggested the idea to Philip that the crusade might be made use of, under the pretext at least of assisting his brother-in-law. Philip had, however, selfish reasons which disposed him to help young Alexis. He seems to have persuaded himself that he had a right to the imperial throne of the East through his wife, and one of his dreams was that it might be possible to unite the two cares of the New and the Elder Nome in his own person. Thus the indignation which lie had a right to feel at the deposition and imprisonment of his wife’s father urged him to a course which coincided with that which his own ambition would dictate. Add to this that the disastrous result of the last crusade had been most keenly felt in Germany, and that any movement against the empire in the East was sure to be popular with his own subjects, and we see that the motives which urged Philip to assist young Alexis were exceedingly strong.

Crusade into a weapon against

If he could help him by turning the crusade into a weapon against the reigning emperor in Constantinople, lie would at the same time succeed in recovering the allegiance of those of his own subjects whom the pope’s excommunication had caused to waver. He could let the pope see that he was more powerful than his rival, and even Innocent might think it well to side with the stronger claimant. His own power would be enormously increased. He might be not only the triumphant leader of the Ghibelin party, but lord of the East and of the West.

Impelled by such motives, the appointment of Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, to the command of the crusading army on the death, in May, 1201, of Theobald of Champagne, supplied the instrument he required. If Boniface could be induced to act with him, a successful attack might be made on Constantinople, and his plans appeared assured of success.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

The agreement between the delegates of the Crusaders

The agreement between the delegates of the Crusaders and the Venetians was ratified, as we have seen, in May, 1201. The crusading army was to arrive in Venice not later than the 24th of June, 1202. In the interval between these dates Death of many events happened. Theobald, Earl of Champagne, the young noble who had taken the Cross on the preaching of Fulk—who had probably been induced to do so partly in order to escape the vengeance of Philip of France—who had been elected leader of the expedition, and in whom all had confidence, died in May, 1201. Ilis loss was the more serious that his great wealth was no longer available for the purposes of the crusade. A payment in advance which had been promised to Yen ice could not be met.

Adopted for the conduct of the expedition

The leaders were divided as to the course to be adopted for the conduct of the expedition. None among them possessed either position or ability sufficient to indicate him as the leader. After considerable delay the leadership was offered to the Duke of Burgundy, and, on his refusal, to Count Theobald of Bar, who also refused. Then a parliament of the Crusaders met at Soissons, and Villehardouin proposed Boniface, ot^ouiface!11 Marquis of Montferrat Visit Bulgaria. The proposal was finally, though reluctantly, accepted. From the first it was evident that Boniface had not the confidence of the Crusaders, and his election was the first severe blow given to the success of the expedition.

Fulk himself affixed the cross to the shoulders of Boniface in the Church of Our Lady at Soissons, and, as the great preacher died in May, 1202, he disappears from this history.1 The appointment of Boniface was in August, 1201. Two months later he was at the court of Philip of Swabia,2 on the invitation of that sovereign. What was the object of his visit may never be accurately known; His visit to but subsequent events raise the presumption that pinup. Philip either had the design of an attack upon Constantinople before this visit, or formed such a design at, and in consequence of, his interview with Boniface.

Prisoner in Constantinople

Philip, the head of the house of the Waiblings, or, as the name was now beginning to be spelled in Ital}r, Ghibelins, had married the daughter of Isaac Angelos, the emperor of the New Eome, who was at this moment a prisoner in Constantinople, deprived of his eyesight, though allowed to go about the city of which he had once been the ruler. The son of Isaac and heir to the throne—whom we may conveniently call, after the fashion of the time, young Alexis, to distinguish him from the reigning usurper Alexis in Constantinople—had made his escape from the capital. lie left the imperial city in the spring of 1201, arrived in Sicilia, and sent messengers to Germany announcing his safe arrival.

Allowing three months for the news to reach Philip, there was ample time for the messengers of Philip to reach the Marquis of Montferrat, and for the latter to have been at the Swabian court in October. Boniface remained with Philip until January or February, 1202, and then left with an embassy for Rome, sent thither in order to induce Innocent the Third to take up the cause of young Alexis. In the spring of the year the latter received letters of recommendation to the Crusaders from Philip. It therefore appears clear that, from the beginning of 1202, the leader of the expedition had become aware of the facts connected with the claims of Alexis. Subsequent evidence indicates that even at this time he had promised Philip to aid him.

At the time appointed—namely, the 24th of June most of the leaders of the expedition had arrived, according to the arrangement, in Venice. Baldwin of Flanders, Hugo Count of St. Paul, Geoffrey of Villehardouin, perhaps Boniface, and many also from Germany, were present, while the Abbot Martin and others from that country were on their way thither.

0 notes

Photo

The agreement between the delegates of the Crusaders

The agreement between the delegates of the Crusaders and the Venetians was ratified, as we have seen, in May, 1201. The crusading army was to arrive in Venice not later than the 24th of June, 1202. In the interval between these dates Death of many events happened. Theobald, Earl of Champagne, the young noble who had taken the Cross on the preaching of Fulk—who had probably been induced to do so partly in order to escape the vengeance of Philip of France—who had been elected leader of the expedition, and in whom all had confidence, died in May, 1201. Ilis loss was the more serious that his great wealth was no longer available for the purposes of the crusade. A payment in advance which had been promised to Yen ice could not be met.

Adopted for the conduct of the expedition

The leaders were divided as to the course to be adopted for the conduct of the expedition. None among them possessed either position or ability sufficient to indicate him as the leader. After considerable delay the leadership was offered to the Duke of Burgundy, and, on his refusal, to Count Theobald of Bar, who also refused. Then a parliament of the Crusaders met at Soissons, and Villehardouin proposed Boniface, ot^ouiface!11 Marquis of Montferrat Visit Bulgaria. The proposal was finally, though reluctantly, accepted. From the first it was evident that Boniface had not the confidence of the Crusaders, and his election was the first severe blow given to the success of the expedition.

Fulk himself affixed the cross to the shoulders of Boniface in the Church of Our Lady at Soissons, and, as the great preacher died in May, 1202, he disappears from this history.1 The appointment of Boniface was in August, 1201. Two months later he was at the court of Philip of Swabia,2 on the invitation of that sovereign. What was the object of his visit may never be accurately known; His visit to but subsequent events raise the presumption that pinup. Philip either had the design of an attack upon Constantinople before this visit, or formed such a design at, and in consequence of, his interview with Boniface.

Prisoner in Constantinople

Philip, the head of the house of the Waiblings, or, as the name was now beginning to be spelled in Ital}r, Ghibelins, had married the daughter of Isaac Angelos, the emperor of the New Eome, who was at this moment a prisoner in Constantinople, deprived of his eyesight, though allowed to go about the city of which he had once been the ruler. The son of Isaac and heir to the throne—whom we may conveniently call, after the fashion of the time, young Alexis, to distinguish him from the reigning usurper Alexis in Constantinople—had made his escape from the capital. lie left the imperial city in the spring of 1201, arrived in Sicilia, and sent messengers to Germany announcing his safe arrival.

Allowing three months for the news to reach Philip, there was ample time for the messengers of Philip to reach the Marquis of Montferrat, and for the latter to have been at the Swabian court in October. Boniface remained with Philip until January or February, 1202, and then left with an embassy for Rome, sent thither in order to induce Innocent the Third to take up the cause of young Alexis. In the spring of the year the latter received letters of recommendation to the Crusaders from Philip. It therefore appears clear that, from the beginning of 1202, the leader of the expedition had become aware of the facts connected with the claims of Alexis. Subsequent evidence indicates that even at this time he had promised Philip to aid him.

At the time appointed—namely, the 24th of June most of the leaders of the expedition had arrived, according to the arrangement, in Venice. Baldwin of Flanders, Hugo Count of St. Paul, Geoffrey of Villehardouin, perhaps Boniface, and many also from Germany, were present, while the Abbot Martin and others from that country were on their way thither.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

Suggested the idea to Philip

The arrival of messengers from Alexis corresponding with the collection of the crusading army appears at a very early period to have suggested the idea to Philip that the crusade might be made use of, under the pretext at least of assisting his brother-in-law. Philip had, however, selfish reasons which disposed him to help young Alexis. He seems to have persuaded himself that he had a right to the imperial throne of the East through his wife, and one of his dreams was that it might be possible to unite the two cares of the New and the Elder Nome in his own person. Thus the indignation which lie had a right to feel at the deposition and imprisonment of his wife’s father urged him to a course which coincided with that which his own ambition would dictate. Add to this that the disastrous result of the last crusade had been most keenly felt in Germany, and that any movement against the empire in the East was sure to be popular with his own subjects, and we see that the motives which urged Philip to assist young Alexis were exceedingly strong.

Crusade into a weapon against

If he could help him by turning the crusade into a weapon against the reigning emperor in Constantinople, lie would at the same time succeed in recovering the allegiance of those of his own subjects whom the pope’s excommunication had caused to waver. He could let the pope see that he was more powerful than his rival, and even Innocent might think it well to side with the stronger claimant. His own power would be enormously increased. He might be not only the triumphant leader of the Ghibelin party, but lord of the East and of the West.

Impelled by such motives, the appointment of Boniface, Marquis of Montferrat, to the command of the crusading army on the death, in May, 1201, of Theobald of Champagne, supplied the instrument he required. If Boniface could be induced to act with him, a successful attack might be made on Constantinople, and his plans appeared assured of success.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes

Photo

Boniface careful to point out Boniface

Boniface, as Bobert de Clari is careful to point out, Boniface.

Marquisuf was a relative of Philip. His father was William Montferrat, and the connection of his family with on the Ghibelin side. This William had married Sophia, daughter of Jbredenc Barbarossa, and sister or half-sister of Philip.1 In the contest for the imperial throne, which had commenced on the death of Henry the Sixth, in 1197, between Philip and Otlio of Brunswick, Innocent himself had sent Boniface with the Archbishop of May- ence to try to arrange their differences. The mission had, however, failed. Kot only was Boniface acquainted with the affairs of Philip, but he had occasion to be well versed in what was passing at Constantinople. The family of Mont- ferrat was well acquainted with the East. Six of its members had contracted marriages with the imperial family. William, the father of Boniface, had four sons, each of whom connected his name with the history of the crusades, and three of them very closely with that of Constantinople. These sons were William, surnamed Longsword, Conrad, Reynier, and Boniface.

The eldest was for a time the hope of the Crusaders. The family was related to the families of the Roman emperor in the West, the King of France, and other powerful princes. He married, in 1175, the daughter of Baldwin the Fourth, the King of Jerusalem, and received in dowry the earldoms of Jaffa and Ascalon, but died two months afterwards.

Marquis of Montferrat

The second son, who became Marquis of Montferrat on the death of William, was that Conrad whom we have seen in Constantinople, aiding the emperor to resist the attack upon the city by Branas. We have seen also that after his marriage with Theodora, sister of Isaac, he refused to follow the emperor to Adrianople, was dissatisfied with his honors, and went to Palestine in 1187, where he played a most important part during the next four years, and especially distinguished himself in the siege of Tyre.

0 notes