#isabelle of castile

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

↳ Historical Ladies Name: Isabella/Isabelle

#isabella of gloucester#isabella of angouleme#isabella of england#isabella of aragon#isabella of france#isabella of valois#isabeau of bavaria#isabella of portugal#isabella i of castile#isabel neville#isabella d'este#isabella of austria#isabella of parma#historicalnames*#historyedit#my gifs#creations*

448 notes

·

View notes

Text

Emilio Sala y Francés (Spanish, 1850-1910) Expulsión de los judíos de España (año de 1492), 1889 Museo Nacional del Prado

#Emilio Sala y Francés#Emilio Sala#1800s#expulsion de los judios de espana#world history#expulsion of jewish people from spain#art#fine art#european art#classical art#europe#european#fine arts#oil painting#europa#mediterranean#Isabella I of Castile#king aragon#ferdinand ii of aragon#queen isabel#king#queen#spanish king#spanish queen#1400s

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabella I (1451-1504) 'The Catholic' by Pierre Gustave Eugene Staal.

#Pierre Gustave Eugene Staal#monarquía española#reino de españa#reyes de españa#reina de españa#isabel la católica#casa de trastámara#reino de castilla#reina de castilla#kingdom of spain#kingdom of castile#house of trastamara#queen of castile#engraving

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Juana of Castile X Philip the Handsome

And no, I'm not romanticizing their toxic relationship

#joanna of castile#juana i of castile#philip the handsome#juana la loca#isabel#spanish monarchy#european history#irene escolar#history#johanna van castilie

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Adrian sighed as he walked through the training centre’s main entrance, a lit cigarette already in hand. He wasn’t on time, but he was sober, which was a surprise in itself, especially considering his recent altercation with Benjamin in Barcelo, and his general distance from Eddie. He’d spent the morning considering bunking off again, but the isolation was slowly starting to nag at him; he’d never enjoyed his own company. In the end, he’d decided it was better to attend and be berated for his missed sessions than to spend another day alone; Rose hadn’t sought him out since the weekend either. Adrian was unsurprised, when he pushed forward into the meeting room, to discover that she hadn’t attended today. He’d have to check on her later. Despite himself, Adrian plastered on a lazy smile, taking a drag of his cigarette as he joined the back of the group, attempting to ignore the incredulous expressions that were shot his way. It was hard, though, considering how bright everyone’s auras were. His friends were a sea of colour, and although it was nothing new to him, it only added to the tension he felt. “Well don’t stop on my account,” he spoke up, cutting through the silence his tardy arrival had caused.

#bwrpstarters#interaction.#c: juliet blackwell.#c: eddie castile.#c: benjamin steele.#c: mason ashford.#c: elijah steele.#c: isabelle lightwood.#april 2019.#here we go again thanks mase

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

– juana i de trastámara ; infanta of spain, duchess consort of burgundy, queen of castile, aragon, valencia, mallorca, navarre, naples, sicily, sardinia and countess of barcelona was born on this day, 6th of november of 1479

#juana i de castilla#joanna of castile#juana the mad#house of trastamara#spanish history#on this day in history#weloveperiddrama#women in history#perioddramaedit#isabel tve#la corona partida#irene escolar#myedit*

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

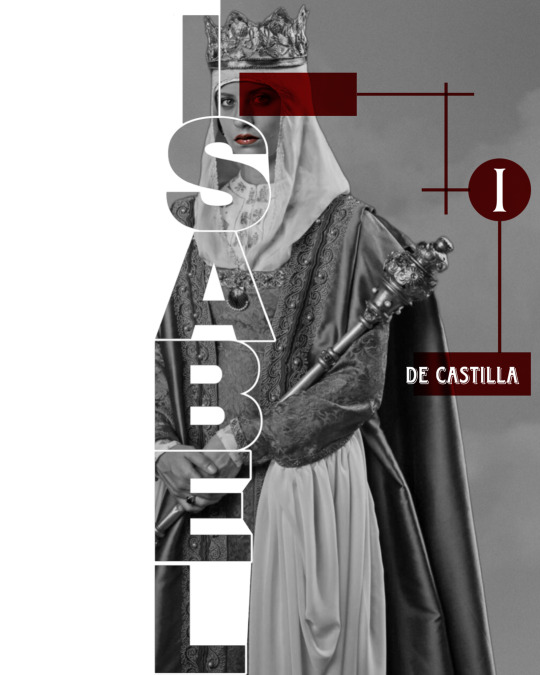

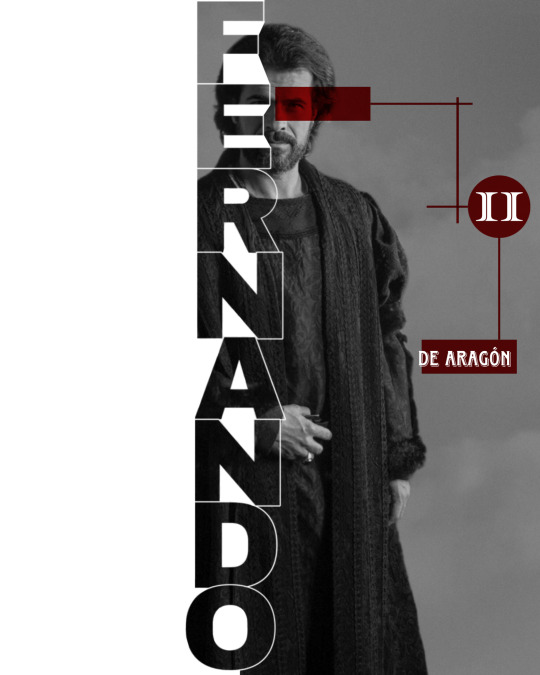

Los Reyes Católicos

#perioddramaedit#historyedit#isabella i of castile#ferdinand ii of aragon#isabel tve#michelle jenner#rodolfo sancho

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Pizarro started from nothing, rising to a life of conquest and glory. He toppled the Inca with an act of Odyssean cunning. After years of war, he went out in a blaze of glory, fighting off assassins even in his old age… is this not Bronze Age Mindset?

Is this not greatness?".

-Alaric the Barbarian.

#Francisco de Pizarro#Pizarro#conquistadors#Spaniards#Spanish empire#Crown of Castile#Bronze Age Mindset#Alaric#Alaric the Barbarian#glory#indo-european#Europe#Tradition#Conquest#The Odyssey#Homer#castile#Exploration#Isabel of Castile#Catholic monarchs#Catholic Queen#cross of burgundy#myth#frontier#America

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Period dramas dresses tournament: Orange dresses Round 1- Group C: Isabel de Castilla, El ministerio del tiempo (gifset) vs Simonetta Vespucci, Medici: the magnificent (gifset)

Propaganda for Isabel's dress:

Another pic 🧡🧡🧡

#period drama dresses tournament#tournament poll#tumblr tournament#polls#fashion poll#isabel de castilla#isabel la católica#isabella of castile#el ministerio del tiempo#simonetta vespucci#i medici#medici: the magnificent#medici the magnificent#orange r1#the ministry of time

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The pipeline of Charles “they had to deceive and drag me to my wedding” ofthe Bold, to his son in law Maximilian “hey… This Burgundian lady is pretty. I think I’m going to like her :)”, Holy Roman Emperor to Maximilian’s son Philip “marry me to this girl right now, idc if we need more pomp, I need to consummate” the Handsome is real, and it can happen to you too.

#Charles the Bold#Maximilian I#Philip the Handsome#House of Valois#house of habsburg#And then we have Charle’s namesake and great grandson (Charles V) who was so love struck he was faithful to his wife and never got over her#Also the way the consorts got sassier… From Isabelle of Bourbon being merely described pliant and faithful#To Mary of Burgundy being (ahem) THE DUCHESS OF BURGUNDY#To Joanna of Castile refusing to put up with her husband and her father’s bullshit#(And to Isabella of Portugal being a good empress and regent as Charles was away)

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isabel of Castile and Katherine of Aragon in blue

Michelle Jenner in "Isabel"

Charlotte Hope in "The Spanish Princess"

#catherine of aragon#katherine of aragon#catalina de aragon#isabel de castilla#isabella of castile#michelle jenner#charlotte hope#isabel tve#the spanish princess

92 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you know that Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York's wife Isabella is likely to have an affair with a man from the Howard family and gave birth to the Earl of Cambridge, Richard? Isabella's will was made with Edmund's consent, which may indicate that although Edmund did not want his property to go to Richard, he did not hate their mother and son. Perhaps they were just colleagues who had to have children together

I'm not quite sure I'm following your ask. I think you're asking about Isabel (or Isabella) of Castile, Duchess of York and the assertion that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was a son born from her adulterous liaison? However, the man she was accused of having an affair with was not a member of the Howard family but John Holland (or Holand), Earl of Huntington. Huntington was the son of Joan of Kent and Thomas Holland and thus half-brother to Richard II. Huntington was married to Elizabeth of Lancaster who was the sister of Henry IV, which would have been made things awkward (to say the least) when Richard II was deposed. Huntington was killed during the Epiphany Rising which aimed to restore Richard to the throne. .

Jenny Stratford recently published work arguing that the affair did not take place and that Cambridge was legitimate, as far as we can tell. I'll talk you through the evidence and her arguments against it below the cut.

Thomas Walsingham's commentary on Isabel

Thomas Walsingham wrote that Isabel was:

A lady of sensual and self-indulgent disposition, she had been worldly and lustful; yet in the end by the grace of Christ, she repented and was converted. By the command of the king she was buried at his manor of Langley with the friars, where, so it is said, the bodies of many traitors had been placed together.

Stratford points out that Walsingham got the date of her death wrong, placing it two years after her death occurred, which suggests he was probably not well-informed about his life. She suggests that the image of emerges from Isabel's will contrasts sharply against the image Walsingham provides:

The duchess herself emerges in a favourable light. In face of her husband’s debts, the arrangement to provide an income for the seven-year-old Richard by transferring to Richard II most of her jewels and plate, her personal chattels, was eminently practical. It limited the possibility of claims by the duke’s creditors, while grants previously made to Isabel were subsequently reassigned to fund the annuity. These provisions seem very unlikely to indicate that young Richard was illegitimate, any more than a gap of twelve years between the age of the oldest and youngest of the duchess’s three living children was necessarily significant. The duke’s will drawn up a decade after Isabel’s death speaks of his devotion to her.

It's also worth noting that Walsingham has something of a reputation for misogyny and for being unreliable - we now know that some of his assertions about Alice Perrers's background are groundless and serve to make her appear worse than she was, while Anna Duch argued that he effectively erased Anne of Bohemia from his account of Richard II's reign. He is also full of vitriol for Agnes Launcekrona and Katherine Swynford so it seems to me that we should treat his claims on women with great scepticism.

John Shirley's comments on Chaucer's Complaint of Mars

Forty years after Isabel's death, a scribe named John Shirley wrote an afterword on Geoffrey Chaucer's Complaint of Mars that linked it to a scandal involving "the lady of York" and John Holland. Connected with Walsingham's commentary, it's generally been taken as evidence that they had an affair.

Stratford argues that the Shirley's commentary is likely a garbled reference to the affair between Constance of York (Isabel's daughter) and Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent (John Holland's nephew) which the resulted in the birth of an illegitimate daughter, Eleanor. Following Kent's death, Eleanor claimed claimed her parents had married clandestinely before Kent married Lucia Visconti and that she was his rightful heir but her claims were rejected. Historians have suggested that Kent might have considering marrying Constance before the revelation that she had been involved in a plot against Henry IV meant he distanced himself from her.

Additionally, J. D. North argued that the astronomical framework contained within Complaint of Mars could have only applied to the year 1385 and aligns it with the beginning of the affair between Elizabeth of Lancaster and Huntington. Elizabeth had been married to John Hastings, heir to the earldom of Pembroke, in 1380 when she was 16 and Hastings was 8. However, the marriage was annulled in 1386 and Elizabeth soon after married Huntington on 24 June 1386. It is frequently asserted that Huntington and Elizabeth had embarked on an affair that resulted in a pregnancy, leading to the hasty annulment of Elizabeth's first marriage and her second marriage to Huntington though it isn't clear when their first child was born, though it was in 1386 or 1387. It may be that John Shirley's reference to the affair between "the lady of York" and Huntington may actually be referring to Huntington's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster.

It may even be that the reference represents a garbled combination of the two affairs - Constance of York and Edmund Holland, Elizabeth of Lancaster and John Holland - recorded decades later. It might be noteworthy in this regard that Elizabeth and Huntington's first child was also named Constance (both Constances were named after Isabel's sister, Constanza or Constance of Castile), which would add to the confusion).

The wills of Cambridge's father and older brother.

The argument that Richard, Earl of Cambridge was illegitimate is based around the lack of reference to Cambridge in the wills of his father and older brother, where it is assumed that this represents that Cambridge was effectively, though not legally, disowned.

His brother, Edward 2nd Duke of York's will was written after Cambridge had been executed as a traitor for his role in the Southampton Plot. His lack of reference to Cambridge may simply be because Cambridge was dead and could not be a beneficiary. There may have also been concern that any reference to Cambridge, such a request for prayers for his brother's soul, could result in suspicion of Edward's own loyalties. From the surviving evidence, Edward also seems to have had a close relationship with Henry V so Cambridge's treason may well have driven a wedge between the brothers. In short: there are a lot of reasons why Edward might have avoided referencing Cambridge explicitly that were far more relevant to the circumstances his will was written in.

Stratford notes that "a testator may not include all his bequests in his will", which would apply to both Dukes of York. Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York left "nothing in the will to any of his three children" (my emphasis). He did, however, ask to be buried "near his beloved Isabel, formerly his companion". In short, there is no reason to presume Cambridge's exclusion was due to his being informally disowned by his father due to the adultery of his mother. York's will provides no support to the idea that he had a fraught relationship with Isabel, either.

Isabel's will makes special provision for Richard, Earl of Cambridge.

Isabel's will asked Richard II for provide an annuity of 500 marks for Cambridge against the surrender of her jewels and plate until appropriate lands could be found to furnish him with an income. This has led to the belief that Cambridge would not be supported by his father and brother and, in combination with the above, that this was because he was illegitimate.

Most of this is based on the transcript of her will published in Testamenta vetusta, which is a shortened extract of the full document which didn't include Isabel's many bequests to her husband (if you read something that claims Isabel left York nothing, the author is working from the abridged will, not the full text). Stratford's study is on the original will in its full form. As noted in your ask, Isabel required and received the permission of her husband to make this will. Stratford also notes that some of those mentioned in the will are Edmund, Duke of York's officers who also appear in his will, "strongly suggesting that the duke and the leading members of his familia were in full agreement with its provisions". In short, the idea that York was refusing to acknowledge or provide for Cambridge seems somewhat illogical given his involvement and the involvement of his officers in Isabel's will which was primarily concerned with providing for Cambridge.

Stratford argues that what the will represents is an effort by Isabel and York to provide for Cambridge "while protecting as far as possible the incomes of her husband and his heir."

The principal purpose of Isabel’s will was to provide for their youngest child, Richard, then aged seven. Edmund gave his wife full powers to dispose of her horses, jewels, robes, the furnishings of her chamber, and her other chattels. She made a number of bequests, notably including books, but offered the majority of her valuables to Richard II if he would agree to provide her younger son, his godson (filiol), with an income of 500 marks per year for life. If the king did not so wish, Isabel’s oldest son, then earl of Rutland, was invited to do so on the same terms.

At the time Isabel was drawing up her will, York was heavily in debt following his Portuguese expedition, had difficulty obtaining money due to him from the Crown, and didn't have lands commensurate with his status. York's executors were still struggling to pay his debts eight years after his death and when his eldest son died in 1415, the duchy of York remained bankrupt for twenty years. Stratford notes that the money raised by Isabel's jewels and plate would "circumvent claims on the duke by his creditors".

John Holland gave Isabel a gift.

Isabel's will mentions a "sapphire and diamond brooch" given to her by John Holland, Earl of Huntington which has been taken as evidence of their affair. Sometimes she is also said to have been given a gold cup and a chaplet of white flowers by Huntington, though Stratford points out the brooch is the only item actually said to have been given to her by Huntington and is one of three gifts from named donors (the others was a "little" gold tablet given to her by John of Gaunt and a gaming board of jasper from Leo of Armenia).

Firstly, while gifts of jewels to us seem to be strictly or largely romantic gestures, this very much wasn't the case within the Middle Ages, where the exchange of jewels was a normal part of aristocratic life, albeit serving an important function. We know that medieval nobles frequently exchanged gifts, including items they had been given by others, and it is a pure speculation to assume that Isabel "treasured" the brooch or even that she kept it because it was Huntington who had given to her. Furthermore, it is entirely possible that it was identified through the designation as a gift given to her by Huntington.

Secondly, if this is evidence of their affair which produced Cambridge, it's very odd that she didn't leave Huntington's gift to Cambridge but to her eldest son, Edward, who was York's acknowledged son and heir whose legitimacy has never been doubted.

Isabel left bequests to Holland.

Isabel left her Bibles and "the best fillet I have" to John Holland. Some have argued that this is unusual enough because Holland was the only person she gave gifts to who wasn't a "close member" of her family.

Outside of her husband and three children, Isabel also left bequests to Richard II, Anne of Bohemia, John of Gaunt and Eleanor de Bohun, Duchess of Gloucester, and Stratford groups with Eleanor as a member of Isabel's "wider family" and says it is credible they were friends, not lovers. The extent that Holland isn't a "close" member of her family can be debated: he was married to her niece (Elizabeth of Lancaster) and the half-brother of her nephew (Richard II).

Stratford says that Isabel may have made the bequest to Huntington in hope that that he would influence Richard II and John of Gaunt (who was Huntington's father-in-law and and close ally in the 1380s and named as an executor in Isabel's will) to ensure that the annuity she sought for Cambridge would become a reality.

Furthermore, Stratford suggests that the "best fillet" (which was probably a collar) may have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, Huntington's wife. If so, this would rather point away from it being a memento from their affair.

There were a ten-year gap between Cambridge and his siblings.

The other main piece of evidence put forward is the large gap between Constance of York (b. c. 1375) and Cambridge (b. c. 1385). The supposition usually goes that having had two children (Edward, 2nd Duke of York was born c. 1373), Isabel and York had grown tired of each other's company and didn't have sex again, Isabel then embarked on an affair with Huntington that, some ten years after Constance's birth, left her pregnant and York allowed the child to be brought up as his son but refused to provide for him.

The problem with this scenario is that it is effectively a complete invention. The idea that York and Isabel were at odds is based around the idea of the affair and the speculation Cambridge was illegitimate. York never repudiated Isabel nor officially disowned Cambridge as a bastard. There are many possible reasons why there was such a large gap - fertility issues, miscarriages, bad luck, personal decisions, religious reasons (i.e. choosing to adopt a chaste marriage). Constance's birth may have been particularly difficult and York and Isabel decided not to chance sexual intercourse or to use the contraceptive methods available to them only to slip up. It's also possible that they may had other children who died too young to leave evidence behind and that the large gap between children wasn't that large in reality. After all, it seems we know very little about the births of their children, even the years are uncertain.

I know this is all speculative but so is the argument that they fell out. The point is that we don't have evidence to explain why beyond speculation.

Conclusion

A lot of the arguments for the affair based on tenuous links and are often based on the assumption that the affair was a historical fact and that Walsingham's comments on Isabel are an objective and reasonable account of her character. So the evidence that shows us a connection between Isabel and Huntington is often assumed to be evidence of a sexual relationship.

Take the brooch. It seems to be read as the equivalent of a man buying his lover an emerald necklace or diamond earrings. Except we know that the exchange of valuable jewels as gifts was a common aspect of medieval noble life that performed a vital function that very frequently had nothing to do with romantic or sexual feelings. We know, for example, that Henry VI gave Eleanor Cobham a brooch - it does not follow that they were therefore having an affair or that Henry harboured romantic feelings for his aunt.

That the brooch was mentioned in Isabel's will also tells us nothing. We don't know how she felt about it, only that she singled it out to be passed onto her eldest son (not Cambridge). It may be that she wanted him to have it because of he had admired it and, if it was a feminine piece, may have intended to give it onto his wife when he married. It's quite unremarkable that a medieval individual would identify a piece through noting who had given it to them and is not proof of romantic attachment. Isabel also mentioned gifts given to her by John of Gaunt and Leo of Armenia - should we assume she had affairs with them too?

On a similar note: that Isabel left items to Huntington is taken as proof of their romantic liaison. The bequest? Her best fillet (probably a collar, according to Stratford), which may well have been intended for Elizabeth of Lancaster, and her Bibles. They were likely valuable items but hardly proof of romantic involvement - such bequests were very common and would be utterly remarkable without the context of Shirley's commentary on their relationship.

It seems to me that there is good good reason to believe that John Shirley's commentary on Complaint of Mars, written decades after Isabel's death, may not have been about Isabel at all. She isn't named in the commentary and we have no clear, explicit evidence of this affair outside of the commentary itself. I think it was a garbled recollection of either Isabel's daughter, Constance of York's affair with Edmund Holland, Earl of Kent or of John Holland's affair with Elizabeth of Lancaster. We have clear, contemporary evidence of both these affairs - the existence of Constance's and Kent's daughter and this daughter's attempt to inherit Kent's estates, the annulment of Elizabeth's marriage to Hastings and her marriage to Huntington.

The evidence cited as "proof" of their affair is really nothing of the sort. Isabel's will attempted to provide for Cambridge in the face of York's (comparatively) small income and large debts. Huntington was a beneficiary but hardly the only one and not a particularly unusual choice. He gave Isabel a gift that was in keeping with the social custom of their class and time. York's will mentioned none of his children and he did not officially disown Cambridge. The lack of reference to Cambridge in his brother's will is easy to understand given it was written after Cambridge had been executed for treason. We have no real evidence of discontent between Isabel and York - he was obviously involved in the writing of her will and he requested burial with her in his own. Nor is there any account that records discord between them or separation, like we do for John of Gaunt and Constanza of Castile. York was buried with Isabel, as he had requested, and on their joint tomb-monument are Huntington's coat of arms (amongst many others). It seems very strange to me that York was so utterly furious about Isabel's adultery that he refused to provide for Cambridge, forcing Isabel to beg the king to provide for him, yet he chose to be buried with her, he chose as his second bride Huntington's niece, Joan Holland, and he chose to add the coat-of-arms with the man she had betrayed him with on their tomb monument (which was probably constructed sometime between 1393 and 1399). I don't think this picture holds up.

Walsingham did criticise Isabel for being "worldly and lustful" but Walsingham calling a woman a slut is pretty par for the course for him and he got facts of her life wrong. Nor does he report anything she actually did to deserve such a reputation. In others: scepticism is clearly needed. None of this adds up to very much. It isn't until Shirley wrote his commentary, decades later, that we find any reference to their affair. The rest are things that would be entirely unremarkable without Shirley's commentary directing us to see it as a romantic gesture.

Of course, the fact is that we can't prove she didn't have an affair and that Shirley was really referring to a more evidenced scandal. Proving a negative is hard. Even if we located, exhumed and DNA-tested the bodies of Cambridge, York and Huntington, we might confirm that Cambridge was really York's son (or Huntington's or the son of an unknown man) but we wouldn't be able to prove that Isabel didn't have sex with Huntington at some point in her life. We don't have evidence for every single time a medieval individual had sex and so we can't definitively rule out the possibility that an affair did occur. All we can say is the actual surviving evidence doesn't support the narrative that Isabel had an affair.

It's probably worth noting that Kathryn Warner also read Isabel's full will and still accepts the narrative of Isabel's infidelity, though she argues Cambridge should be given the benefit of the doubt where his illegitimacy is concerned. Personally, I find Stratford's reading of the will more credible than Warner's. I don't think the evidence cited as proof of Shirley's claim is actually evidence of an affair but the existence of a typical relationship between medieval nobles working as normal. Warner seems to contradict herself at times* and she doesn't seem to have been interested in questioning whether Isabel did or did not have an affair. I also think Stratford's extensive work on medieval manuscripts and the inventories of John, Duke of Bedford and Richard II lends credence to her claims.

Works Referenced

Jenny Stratford, "The Bequests of Isabel of Castile, 1st Duchess of York, and Chaucer’s ‘Complaint of Mars’", Creativity, Contradictions and Commemoration in the Reign of Richard II: Essays in Honour of Nigel Saul, eds. Jessica A. Lutkin and J. S. Hamilton (The Boydell Press 2022)

Jenny Stratford, "Isabel [Isabella] of Castile, duchess of Yorkunlocked (1355–1392)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (published 2022, updated 2023)

J. D. North, Chaucer's Universe (Oxford University Press 1988)

James P. Toomey (ed.), "A Household Account of Edward, Duke of York at Hanley Castle, 1409-10", Noble Household Management and Spiritual Discipline in Fifteenth-Century Worcestershire (Worcestershire Historical Society 2013).

John Evans, "XIV. Edmund of Langley and his Tomb", Archaeologia, vol. 46, no. 2, 1881

Kathryn Warner, John of Gaunt: Son of One King, Father of Another (Amberley 2022)

(also looked at the ODNB entries for York, Cambridge, Huntington and Elizabeth of Lancaster).

* After mentioning the brooch given to Isabel by Huntington, Warner states: "Isabel did not not mention other gifts she had received from anyone else". In an earlier chapter, Warner says "The 1392 will of Isabel of Castile, duchess of York and countess of Cambridge, reveals that Levon [Leo of Armenia] gave her a ‘tablet of jasper’ during this visit, which she bequeathed to John of Gaunt". Warner also repeats this within the chapter dealing with Isabel's will: "and ‘a tablet of jasper which the king of Armonie [King Levon of Armenia] gave me’ to John of Gaunt". How can Huntington's brooch be the only gift from anyone mentioned in her will when we've been told (twice) that Isabel's will includes a reference to a tablet of jasper gifted to her by Leo of Armenia? Additionally, Warner's arguments seems to be drawn from the preconceived notion that Isabel did have an affair so any evidence connecting her to Huntington must be evidence of the affair, regardless of how limited the evidence is - this is quite surprising, since it goes against one of her arguments against reading Isabella of France and Roger Mortimer's relationship as a love affair.

#ask#anon#isabel of castile duchess of york#john holland earl of huntington#edmund duke of york#richard earl of cambridge#i did just have the revelation cambridge was only a year and a bit older than henry v#god this is long

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

José Garnelo y Alda (Spanish, 1866-1944) The first tribute to Columbus (October, 12, 1492), 1892 Museo Naval, Madrid The work depicts Columbus landing in the New World on the island of Guanahani (in today's Bahama Archipelago), and the new lands being taken over in the name of the Spanish monarchs on October 12, 1492. The artist was inspired by descriptions found in Columbus's renowned journal, but modified certain aspects, including dressing the native people (whereas the journal states that they went about naked). The cross is a reference to Christianity and the evangelizing work carried out in the New World. The flags of Castile reinforce the idea of allegiance to the kingdom and Columbus' stature as an envoy of the monarchs.

#José Garnelo y Alda#spanish art#spanish#hispanic#latin#colonialism#colonization#spanish colonial#queen isabel i of castile#art#fine art#european art#classical art#european#europe#oil painting#fine arts#europa#mediterranean#christopher columbus#Ferdinand II of Aragon#catholic monarchs#castile#aragon#spanish monarchs

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thread about Joanna of Castile: Part : 10 “A Storm of Jealousy: Juana and Philip's Turbulent Reunion"

By May 1504, Juana was in Burgundy. Juana’s reunion with Philip and the children was joyful.

But soon afterwards she suspected, or discovered, an affair between Philip and a noblewoman in her entourage:

“They say,” writes Martire, “that, her heart full of rage, her face vomiting fames, her teeth clenched, she rained blows on one of her ladies, whom she suspected of being the lover, and ordered that they cut her blond hair, so pleasing to Philip …”

Philip’s response was equally furious. He had “thrown himself” on his wife and publicly insulted her.

Sensitive and obstinate, “Juana is heartbroken … and unwell …”. Isabel “suffers much, astonished by the northerner’s violence.

Maximilian’s biographer, Wiesfecker, describes Juana’s response as:

"The symptom of a pathological, passionate, if not unfounded, Haßliebe, fomenting continual strife. "

Juana would have known for years about Philip's visits to the baigneries and his more casual relationships with women. However, this affair seemed to pose a direct challenge to her standing and dignity. Juana knew her faults and had tried to limit them. In 1500, after becoming princess, she had asked Isabel to send her an honest and prudent Spanish lady who:

“Knows how to advise her, and where she sees something out of order (‘deshordenado’) in her conduct could say so as servant and adviser but not as an equal because, even if the advice were good, if expressed in a disrespectful way it would create more anger in she to whom it was said than it would allow for correction.”

Sources: Fleming, G. B. (2018). Juana I: Legitimacy and Conflict in Sixteenth-Century Castile (1st ed. 2018 edition). Palgrave Macmillan.

Fox, J. (2012). Sister Queens: The Noble, Tragic Lives of Katherine of Aragon and Juana, Queen of Castile. Ballantine Books.

Gómez, M. A., Juan-Navarro, S., & Zatlin, P. (2008). Juana of Castile: History and Myth of the Mad Queen. Associated University Presse.

#joanna of castile#juana i of castile#juana la loca#philip the handsome#isabel#european history#spanish monarchy#spanish princess#infanta#irene escolar#raul merida#flanders#vlaanderen#Huis Habsburg#House of Valois-Burgundy#Filips I van Castilië#Philippe le Beau

24 notes

·

View notes