#kiki try not to suffer challenge (IMPOSSIBLE)

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

practicing osomatsu-san art style …this is hell ;w;

#osomatsu san#mr osomatsu#osomatsu matsuno#osomatsu san fanart#osomatsu fanart#おそ松さん#osomatsu kun#practicing the art style…i hate this#kiki try not to suffer challenge (IMPOSSIBLE)#I could draw him in my art style but that’s boring..#also kinda new to tumblr ;w; but I do lurk a littleeeee teeheee#been in this fandom for 7 years and never really interacted#but if anyone has any advice on getting the art style right errrrmmm i would appreciate it! i just used official art#official art being NEET style book cover… used ichi choro and oso pose ^_^#need to master this art style#my art style is kinda messy..sorry about that! !#hc that oso has some facial hair and just messy/bed hair all the time..heheee if you haven’t noticed that#also hc he has some beauty marks#but forgot to add that in..;w;#but it’s mostly on his body so ..bleh#okay …enough talking I’ll try to post more :3

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part 3: Nancy Drew & The Vanishing Set Designer

The Importance of Cohesive, Believable Game Worlds

A wall of text series on how Nancy Drew games largely lost their charm--this time with pictures!

Boasting more than 30 titles released over the course of nearly 20 years, it’s obvious why the Nancy Drew series has experienced changes in graphics. Thanks to never-ending advancements in PCs and artists who continue to hone their craft, the games moved ever closer to an ultra-realistic ideal.

Improved textures and dynamic character animations were some of the most noticeable and appreciated changes that helped to further immerse the player and create a beautiful game world. That said, a convincing game world does not require the latest and greatest graphics--it only requires cohesion. The most realistic graphics in the world are nothing without a skillful designer behind the scenes, setting the stage and making everything feel “right.” Unfortunately, that designer seemed to vanish with increasing regularity as time went on.

Empty Spaces

HER has never had a AAA budget, and that comes with certain limitations. One of the most obvious is the amount of characters that Nancy is able to interact with in each game. Since creating, animating, and voicing characters takes quite a bit of time, there are rarely more than five. This can create some challenges when it comes to creating a game world which feels lively and believable.

Some locations, like the abandoned Thornton Hall or the soon-to-be B&B in Message in a Haunted Mansion need no excuse for their limited cast, but others require a bit of explaining.

Sometimes, a story-driven explanation is given for how sparsely populated a location is. For example, in Secret of the Scarlet Hand, the museum is currently closed to visitors, just like the park in The Haunted Carousel. But other times, a few tricks are needed to seal the deal--and not every game had some up its sleeve.

The Good:

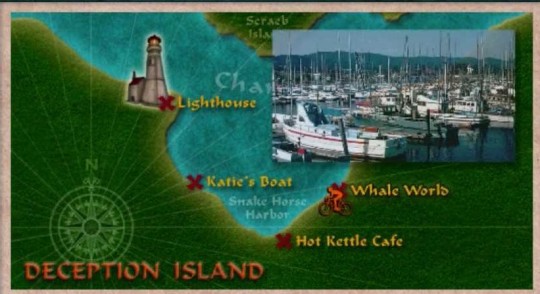

Danger on Deception Island did a good job of making the Hot Kettle Cafe, an otherwise sparsely occupied establishment, feel as if a group of bustling customers were just out of view through the use of sound effects.

Dishes are clinking, people are chatting and laughing, but only Holt and Jenna are ever seen. Yet, the simple addition of those sound effects and a little sign saying the other part of the cafe was occupied helped the player suspend their disbelief.

Perhaps even more impressive, Danger by Design managed to make a public park feel fairly believable through the use of cleverly obscured vendors, street and nature noises, a pesky squirrel, and a suspect visiting at one point.

This location, coupled with the choice to have Nancy immediately appear behind the parfait counter at Cafe Kiki against the sound of chatting customers, allows the game developers to avoid making Paris feel underpopulated even though there are only a handful of NPCs.

The Bad:

Unfortunately, The Phantom of Venice did not succeed in presenting Venice as well as DAN presented Paris. Though the Ca’ itself was beautiful and the musical score was, as usual, wonderful, the vast majority of the locations felt completely and utterly dead.

No amount of heels clicking on the pavement, people occasionally shouting Italian phrases, or flocks of pigeons landing briefly was going to make these locations--which are visited many times throughout the game--feel real.

The game designers chose to set many of the clickable buildings further back, revealing large swathes of empty streets and public squares, rather than having Nancy appear at the front door like she does in many other games.

While I can see they were clearly trying to showcase the unique architecture of Venice, it simply results in a mostly “off” feeling game world since one would expect lots of people to be roaming around.

The Silent Spy--with its basically empty train station--and Shadow at the Water’s Edge--with its barren urban environments--suffer from this problem as well, along with the game I love to hate: The Shattered Medallion.

Even though MED makes a ridiculous attempt at explaining why Sonny Joon is the only member of staff present and conveniently gets rid of the vast majority of the competitors within the first act of the game, it still utterly fails at making the player feel as if they are participating in a game show. Frankly, with the constraints put upon HER by their budget and game engine, I simply cannot imagine how they could have successfully pulled off an authentic game show experience, but the lack of competing teams was far from the only issue with MED.

The Great Outdoors

The trouble with any game world is that there almost always must be a boundary--a limit to where the player can go. Except for games that feature randomly generated locations, players can expect to--sometimes literally--hit a wall at some point. The trick is to make it seem as if there is no wall.

Outdoor locations can make pulling off such a feat difficult, because as the depth of field is increases, more and more objects are required to fill all that space. However, it is by no means impossible, and HER has marvelously pulled it off many times.

The Good:

Ghost Dogs of Moon Lake was the first game to truly offer an outdoor experience. While previous games like Treasure in the Royal Tower and Secret of the Scarlet Hand had walled gardens, DOG gave the player an expansive forest to explore during the day and night.

This game succeeds at giving the player a sense of actually being deep within a dense forest by using layers upon layers of 3D trees. No matter where you look inside the thicket, you never seem to see a “wall.”

Not only that, but allowing the player to wander in the woods rather than having every location be accessible by a jump map--like the motor boat map--makes the game world feel very large, though some players may find backtracking to be annoying over time.

Another contribution to that sense of realism, much like the Hot Kettle trick, is the use of environmental sounds and critters. Songbirds singing in the trees, the famous chirping worms of Pennsylvania, and other woodland noises play almost constantly in the background as Nancy’s feet crunch upon earth and fallen leaves.

The DOG designers also used a limited, cohesive color palette of muted, earthy tones not only in the forest but also throughout the cabin, speakeasy, and ranger station.

The result? A game which, though it may not rival the likes of Skyrim in detail or variety, feels thoroughly cohesive and drips with atmosphere.

Similar success--though on a smaller scale--was achieved by the forest in The Captive Curse, which was full of sounds, had misty depth of field and gave the player a true sense of being lost in a dark, potentially sinister place.

The Bad:

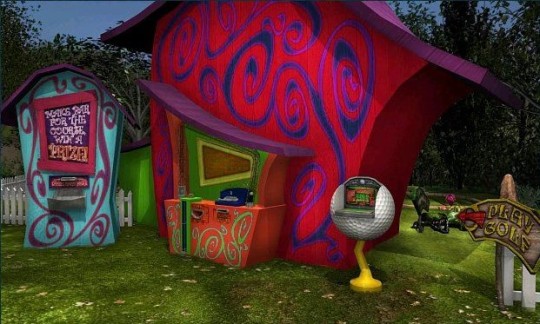

The Shattered Medallion, on the other hand, is one of the worst offenders of a poorly designed outdoor world. Given that this game was almost entirely set outside, HER certainly had a challenge on their hands, but they failed miserably.

Contrast this forest scene with the one from DOG or CAP. Those trees are almost definitely 2D photographs pasted in a row, allowing for almost no depth of field, and it’s the same story for the mountains.

Using 2D assets is not necessarily a no-no, but here they make the actual 3D models--the silver flower stations and the puzzle palace--look wildly out of place.

The same thing is happening in this other half-ass location from MED. A strange collage of photographs with a few oddly lit 3D models pasted on top makes for a very “wrong” feeling scene.

Indeed, almost every outdoor location in MED has this very weird feeling of being on a Hollywood set--like the backdrops could fall down at any moment and reveal the whole thing to be a farce--and it’s made only worse by the almost complete lack of background noise. Admittedly, I have never been to New Zealand--perhaps it really is deathly quiet--but this game could have greatly benefited from some consistent sounds of nature to liven-up its otherwise lifeless locations.

On top of all that, this game seems to have no color scheme of which to speak nor does it feel expansive. A jump map is used extensively for traversing the landscape, with many outdoor locations only allowing the player to take a mere handful of steps in any given direction.

The result? A game which simply feels “wrong” in nearly every conceivable way.

By no means is MED the only offender, though. Similar depth of field issues--though not as egregious--were present in Secret of the Old Clock, and as far as cohesion goes, I think we should all take a moment of silence for this travesty:

All I can say is, whoever approved that design was just...wrong.

The Jump Map

Jump maps can be great time-savers when going back and forth is a key gameplay element, and the Nancy Drew games certainly involve a lot of back and forth. Sometimes they save a player a lot of headache, but sometimes they break immersion--particularly when they attempt to stand in as a cheap substitute for an expansive, believable game world.

The Good:

Danger on Deception Island is one of many games which features a jump map for key locations.

What makes this map work is simple: each location is fairly large and immersive in its own right, and there is presumably little to be gained by forcing the player to click one million times down the actual road to each place.

That said, while the player may jump from the lighthouse to the Hot Kettle with the click of a button, copious amounts of kayaking, exploring beaches and the enormous tunnel system keep the game from seeming too constrained. The player feels as if they really have explored Deception Island, rather than feeling as if they have simply visited a few buildings.

The jump map in DOG, SSH, STFD and various other titles work for the same reasons--the forest, Beech Hill museum, and WWB studio respectively seem so large that jumping around to smaller, more limited locations doesn’t actually feel very limiting at all. Plus, the art style used for the map can often add to the immersion, like the subway and train maps.

The Bad:

Though its map certainly looks plausibly like an amusement park flyer, The Haunted Carousel was the first game with a jump map that truly felt like a limitation.

Though there are double the “clickable” locations on CAR’s map in comparison to DDI’s, there simply isn’t much to explore in CAR’s locations. Indeed, the park feels very tiny, and I can’t say I truly felt like I “saw” Captain’s Cove. Perhaps if even one location had allowed for more open exploration, the game wouldn’t have felt so limited.

In the same way that mini-games and repetitive tasks can serve to artificially lengthen or beef up a game, jump maps can attempt to artificially expand a game world. Sadly, there are even more cheap tricks deployed in service of this goal.

Third Person Perspective

Secret of the Old Clock was the first game to transform the jump map into a driving simulator, and this mechanic was met with mixed reception--it seemed like players either loved it or hated it for various reasons. Regardless of opinion, this game mechanic always introduces a risk: the style of the game changes.

No longer is the player immersed in a first-person, beautifully rendered 3D world--they are now dropped into third-person on a stylized, top-down map. The effect is simple: the player is very aware they are playing a video game.

The Creature of Kapu Cave, The White Wolf of Icicle Creek, The Phantom of Venice, and The Haunting of Castle Malloy all featured variations of this third-person mechanic, and many games afterwards incorporated some form of the driving simulator to varying degrees of success, but Ransom of the Seven Ships went absolutely wild with it all.

From sailing around, to scuba diving, to rock climbing, to digging holes, to driving the golf cart around the island--the player was constantly yanked from the first-person, 3D-rendered game world and thrust into what were essentially 2D mini-games. While the color scheme was consistent, the art style varied greatly, making the game feel much less cohesive than many of its counterparts.

While RAN certainly felt like a very large game in terms of terrain--complete with copious amounts of agonizing back-tracking--it really lacked immersion. Indeed, there is no real sense of urgency like that in The Final Scene--despite it being Bess who has been kidnapped--and the focus is constantly taken off of the mystery at hand and onto figuring out how to drive correctly or sail that godforsaken boat.

A Matter of Preference

Ultimately, I think the Nancy Drew games evolved along something of a sliding scale. In the beginning, the aim was to put the player into Nancy Drew’s shoes, but this aim slowly and steadily shifted towards that of simply creating a game. And the truth is, there is nothing wrong with either aim; it’s all about what experience you’re looking to have.

When I first started playing the Nancy Drew series, I was looking for a mystery-solving simulator and I couldn’t get enough. I’ve played a lot of other detective games, but the ND games were really something special, so when they stopped delivering the same type of product, I really felt like something great had been lost.

Again, there is nothing wrong with game-y games, but there is something to be said about games that try to provide an authentic experience. It’s not every day that an ordinary person gets to solve a mystery--a mystery that seems so plausible that you feel a real sense of accomplishment when you unravel all its threads.

I missed that in so many of the later games, and I think that’s a shame.

Read Part 1: Nancy Drew & The Curse of the Pointless Task & Part 2: Nancy Drew & The Case of the Missing Realism

68 notes

·

View notes

Note

More of A Slip of the Tongue, because Ryuu casually calling them mom and dad is the happiest thing to ever happen to me. <3

Kirito’s half hanging out of the window when he says, “It’s a little funny.”

“It’s been weeks.” Ryuu rubs at his head, agitated, trying not to watch whatever death-defying trick he’s gleaned off of Obi this week. “And Jirou told me he’d ‘tell my father abut this’ when he saw me walking back from the lab last night. The guards were laughing.”

Kirito makes a sound suspiciously like a snort. “C’mon, it’s been two weeks, and nothing ever happens here.”

Ryuu hunches over his desk, grumbling, “Well I wish it would.”

It hadn’t helped that Obi was waiting for him this morning, mouth set in concern. The whole way to the lab he’d gently reminded him that sleep was important, especially for growing researchers. Ryuu had to bite his lips to keep from pointing out that guard captains needed the same.

“Maybe someone will fall off the wall,” Kirito offers brightly. “That always gets tongues wagging.”

He rolls his eyes. “One can only hope. Now come back and close the window. Science takes a consistent room temperature, and you’re letting in a draft.”

“But Obi –”

Ryuu fixes him with his most Shirayuki-like look of disappointment. “Well, if you want to explain why Shirayuki’s stones didn’t crystallize –”

“Yeesh, I’m coming, I’m coming.” Kirito scrambles back, closing the window with a rusty screech. Suzu will have to look at that when he gets back from –

“Oh hey now.” Kirito pressed himself against the glass, nose pressed comically flat. It was too bad there was no chance of anyone seeing it, four stories up. “Looks like you’re about to get your wish, Little Ryuu.”

He glares at Kirito for the nickname, but squeezes in beside him, peeping through the glass, and –

And blue-and-white banners snap in the breeze, just above where a young man with white hair has swung off his horse, two aides at his back.

Oh no. Oh no no no. This is –

Kirito cocks a grin. “The prince is here for an official visit.”

– a disaster.

The next morning finds Ryuu in his office, wearing a groove in the floorboards.

It’s Friday, and Friday is journal day, as per his request four years ago, when he first saw the state of Suzu’s lab notebooks. While both his lab mates – and their assistants – bear the event with an air of noble suffering, Ryuu revels in it. He closes his door, cozens under his desk, and sets to replicating his scrambled notes neatly in his notebook, enjoying the scent of parchment and leather as he works. Sometimes, he doesn’t even get disturbed until dinner.

Today, however, it makes him a sitting duck.

There’s no reason to be so worried – it’s not as if anyone would tell Prince Zen; they know he’s friends with Obi and Shirayuki, but it’s rare that outsiders are brought in on the jokes that the Northerners share when the snow falls and work slows. But still – it would be all too easy to slip, for a guard to say tell Ryuu’s dad that he has the midnight shift, or go bring Little Ryuu to his mother, or – something worse. His imagination is white noise, but that does not make the dread any less real.

He tries to force himself to work, to sit up at his desk and order his notes into something approaching consistency, but his hands shake; when he tries to hold a pen, it trembles from his grasp.

That is ridiculous. It was – a slip of the tongue. It didn’t mean anything, and a man like Prince Zen would know that. There’s no way he would feel threatened by the – the subconscious feelings of an adolescent. It’s not like he was saying –

“Ryuu!” The door bursts open, and his papers take flight.

The prince stands in the midst of his office as notes fall like flakes from the rafters, as if they stand in a snowglobe that’s been tipped. Zen might as well be a painted figure for the pose he cuts, hands on his hips and eyebrows upraised. It would only make sense; whenever Ryuu stood in his presence, the feeling of unreality clung to the moment: a prince taking interest in a little orphan boy, just like out of a fairy tale.

“Prince Zen,” he breathes. “Are you looking for Shirayuki? We don’t share offices anymore. I think she’s in a meeting with Shidan, but hers is just –”

“Oh, no, Obi already told me.” His smile is perfect and white and kind, but it only sets Ryuu more on edge, makes him wonder more what a prince was doing in his office. “I came to see you.”

Ryuu swallows hard. “Me?”

“Yes, you!” the prince laughs, as if he could not fathom how Ryuu might not know the level of his esteem. “I thought we all might have dinner tonight.”

“A-all?” He winces, thinking about a grand hall, chairs filled to a man, Ryuu up on a dais –

“Yes, you, me, Obi and Shirayuki.” He seems excited by the prospect. “A private dinner, with just all of us from Wistal. No Mitsuhide or Kiki this time, of course.”

Wistal is a small, quiet office with the window open, Higata struggling with pots heavier than he can carry, and Garrack peeking down at him with soft eyes and oh-so-quietly closing the curtain. It isn’t the prince and his aides, not to him.

There’s no good way explain. No way that isn’t insulting at least, and Ryuu does appreciate the prince’s good will toward him, his solicitousness when it comes to Ryuu’s academic growth.

It is just impossible for him to shake the feeling that it only endures because of his relationship with Shirayuki. As if he is some – some younger sibling, destined to be forgotten and ignored as soon as the romance ends.

If the romance ends, he reminds himself. It’s been six years; time enough for hearts to change, if they were going to.

“Sure,” he grunts with a nod. “Of course.”

The prince claps his hands, pleased. “Great! Tonight, then? My quarters?”

“Ah.” He makes himself busy with picking up his notes, so the man doesn’t see his grimace. “Yes. Sure.”

“I heard my mother is sending your proposal on to the Council of Lords,” Zen offers, during a friendly lull in conversation.

It’s all been fond memories of Wistal until now; ones Ryuu didn’t share, but were pleasant to listen to as he ate. He’d laugh in the right places, and the conversation would carry on without him, and it was – nice. Not as fine as eating with just Obi and Shirayuki, but good enough.

But of course, it’s not to last.

“Um, yes,” he murmurs, eyes darting over the table for something to anchor him. The salt doesn’t grab his attention, nor the other serving dishes, but Obi lays a hand flat on the table, and that – that holds him. “She is.”

“That must have been some presentation!” Prince Zen’s mouth opens wide in a smile, and oh – oh no – he doesn’t know what he’s invited, saying something like –

“The presentation was brilliant,” Shirayuki gushes, at the same time Obi loudly brags, “Ryuu is the youngest to ever present in front of Their Majesties.”

He covers his face, but it does nothing to muffle the conversation; Obi and Shirayuki boasting about a humiliating number of his academic exploits while the prince sits quietly, making the right sounds in the right places.

“One of the old men at the university tried to challenge his work the other day,” Obi begins, in that broad way he has when he’s settling in to tell a story, and Ryuu groans. “And he –”

“He means one of the chairs at the university,” Shirayuki interjects. “He was trying to disprove Ryuu’s theory on root systems –”

“Right, he had some problem with the way Ryuu was talking about roots.” He wishes he could will himself into nothingness, rather that have to listen to this. “And Ryuu, he goes right up to him, in the middle of his lecture –”

“It was a forum.” Shirayuki’s voice lifts with excitement; she’s never had much love for the herbology chair. “He’d called it to correct Ryuu’s research, there were nearly five hundred people there, almost all of them in upper level research –”

“Right, so in front of all these smart-types, Ryuu comes in, carrying something like a hundred pounds of books –”

“He’d taken out every book on root systems in the library –”

“And he just told the old man off right there, in front of everyone!”

“His rebuttal was elegant,” Shirayuki told the prince, pride thick in her voice. Ryuu’s heart clenches at the sound. “Not a person left without thinking Ryuu’s theory was the next step forward on plant proliferation.”

“You know I prefer fists when it comes to fights, Master,” Obi says, “but I couldn’t have been prouder than if Ryuu punched the old man him –”

“Obi,” Ryuu cries out, of only to stop him. He can’t take all this – this attention.

The table goes utterly silent. Ryuu drops his hands.

The prince stares at him with a strange face. “Dad?”

Aaaargh.

He casts his gaze over at Obi, trying to – to ask for help, or – or something, but he –

He is staring down at his plate with something akin to wonder, akin to pride, akin to – to–

Heartbreak.

“Obi?” he tries, but it’s swallowed up by the prince’s laugh, by his booming, “I didn’t know you were so old as to have a son, Obi.” He turns thoughtful. “Though if all your boasting is true, you certainly sowed your wild oats enough.”

Shirayuki frowns. “Zen…”

Obi’s face stutters, mouth passing through a grimace before he lets out his own laugh. “Well, Miss always said: I may joke, but I never lie.”

She glances at him, wary, but Obi’s face is as bright as it ever is. Ryuu wonders if she can see it’s a mask, if she can see the way it’s peeling and cracking at the edges. It’s always been Shirayuki who could see these things, but – but –

Prince Zen is so dazzling, she’s too often blinded by his presence. Ryuu presses his lips together, hands fisting beneath the linens.

“Well, if Obi is the father,” Zen chuckles, swiveling his head to Ryuu. “Then who is the mother?”

He shouldn’t – he shouldn’t say anything – hadn’t he been so worried about this just hours ago? – but –

But he raises his gaze to Shirayuki’s face, flushed and frowning, and says with pointed ease, “I don’t know, I guess.”

Ryuu doesn’t read faces easy, at least ones that don’t belong to Obi or Shirayuki, but he sees the suspicion take hold on Zen’s at the same time resolve sets on Shirayuki’s.

“Zen, I don’t think…” She clears her throat. “You shouldn’t joke. Obi…”

Her face flushes, not from the wine this time, and she says, “He would be a really good father, I think.”

“Is.” The word is out of his mouth before he can think, but –

But it’s worth it, to see the look on Obi’s face.

Shirayuki sees it too. “You’re right,” she says, so softly, “he is a good father.”

Zen’s gaze darts between the two of them. “I…see.”

In the silence that follows, no one able to lift their gazes from the table, Ryuu wonders if they all are beginning to.

“Well!” Obi leaps to his feet, dish in hand. “I should – should go. I have the morning shift, you know, wouldn’t do to go to bed late and wine-drunk.”

Shirayuki half-stands to follow. “Obi –”

He holds up a hand, and his smile is – is pained. “No need, Miss. You and Master enjoy dessert.” He shifts his gaze to Ryuu, lips pulled tight. “Come on, Little Ryuu. Help your father with these.”

“O-of course.”

When they close the door behind them, arms laden with dishes, the room is still silent, still thick with something.

Obi lays an assuring hand on his shoulder. “Don’t worry, Little Ryuu. They’ll work things out.” His face is too deep in shadow to see more than the white of his teeth as he smiles. “After all, it’s just a joke.”

His hands tighten around the rim of his plates. It’s not, it’s not. “Yeah,” he grunts softly. “Sure.”

His room is dark when she goes to him. Only the moonlight shafting through his narrow windows illuminates him, shows how he is caved in, hollowed out around his heart.

You’re right, of course, Zen had said after the door closed, smiled pulled tight across his face. Now that I think about it, Obi’s always had a soft spot.

It’s not his fault; he hasn’t been here to know – to know all the things she does, but –

“You can take it back now.”

His voice is as it always is, light and playful, but she hears the fraying in it too, the way he’s unraveling.

“There’s no one here now,” he reminds her. “You can take it back, Miss.”

“Obi –”

“Please.”

The bristle of his hair tickles her palm as she rests it on his head. “I can’t.”

He looks up at her then, oh so slowly, eyes blinking and dark in the shadows. All she can see of them is their shine. “Why?”

“It would be a lie,” she says, so softly, running furrows in his hair. “It would be a lie if I took it back.”

He pitches forward, head thumping against her belly. “You should go.” His voice is muffled in the folds of her dress. “You should be with Master, Miss.”

“No.” Her fingers shift softly over the whorl of his cowlick. “I’m right where I’m meant to be.”

His breath is hot against her belly, heavy. She feels damp where he rests his head. “I’m right where I’m needed most,” she says, less certain. “Aren’t I?”

Finally, finally, he tilts into her touch. “Yes,” he sighs. “Yes.”

#thelionshoarde#obiyuki#happy family#my fic#ans#Holiday Promptathon#speaking as a younger sibling#there was always a difference between the people who only were interested in you#because they were dating your sibling#and the people who found you interesting and valuable#whether they were with your sibling or not#and i always felt that ryuu must feel the difference

28 notes

·

View notes