#micklegate bar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

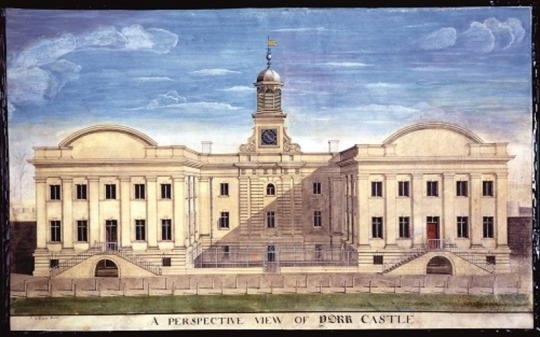

Micklegate Bar, the most important medieval city gate of York. - 1890's

View More Remarkable Historical Photos, handpicked for you each day! https://www.youtube.com/@SealedinTime

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

castlesandmedievals - Micklegate Bar, York, North Yorkshire, England

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The 12th-century Micklegate Bar in York, England. This was once the main entrance into the old walled city for people coming from the south. It served as a ceremonial entrance for monarchs: King Edward IV, Richard III Henry VII, James I, Charles I, the future James II all entered the city through here.

Often displayed on the gatehouse were the heads and other body parts of enemies. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York (father of Edward IV and Richard III), Edmund, Earl of Rutland (another son of Richard) and Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, all had their severed heads displayed on this gatehouse.

The lower part of the gatehouse is 12th century, the upper parts date to later centuries.

Source: Facebook

International Man of History

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

On November 15th 1746, James Reid was executed at York for being a part of the Jacobite uprising.

I'll cover the case of James Reid towards the end of this post, but he wasn't the only Jacobite to meet his end at York, so there is a fair bit of background I have to get through first.

After the capture of Carlisle on 30th December 1745, 193 Jacobite prisoners were sent to York. They arrived in York on 27th January 1746. By February 1746, there were 251 Jacobite prisoners held at York,

After transfers, releases and deaths in custody eventually there were 75 prisoners sent for trial in York. The trials were held between 2nd and 8th October 1746. Of the 75 prisoners, 53 pleaded guilty and were not tried but were automatically sentenced to death. Of the remaining 22, five were acquitted and the others sentenced to death.

On 1st November, ten executions were carried out at the Tyburn on York’s Knavesmire. Of these, three had their heads removed. The most prominent of those, Sir George Hamilton’s head was sent to Carlisle for display, while those of William Connolly and James Mayne were placed on Micklegate Bar. In 1754, the latter two heads were removed by a York tailor called William Arundel. He was heavily fined and imprisoned in York Tollbooth.

On the 8th November, eleven of the 53 planned executions were carried out and finally we get to the 15th November when just one man, James Reid, a Piper, was executed. At his trial, James had stated in his defense that he “had not carried arms”.

James Reid was one of several pipers who played at the Battle of Culloden. He was captured along with hundreds of men by Cumberland’s troops and taken to England. There James was put on trial and accused of high treason against the Crown. Piper Reid claimed that he was innocent because he did not have a gun or a sword. He said that the only thing he did that day on the battlefield was play the bagpipe.

After some deliberation the judges had a different opinion on the matter. They said that a highland regiment never marched to war without a piper at its head. Therefore, in the eyes of the law, the bagpipe was an instrument of war. The English jury, itself sympathetic, recommended mercy but it was rejected by a Commission headed by Lord Chief Baron Sir Thomas Parker.

The decision of those judges has echoed down through the generations. It was the first recorded occasion that a musical instrument was officially declared a weapon of war. For hundreds of years and many conflicts to come the bagpipes, when listed among the items captured in combat, was counted among rifles, sabers, and munitions. It is interesting to note that bugles and drums were recorded as musical instruments, where the bagpipe ranked among the lists of weapons. This continued through the Great War. Perhaps a fitting place for the pipes, but a tragic legacy for the piper James Reid who played at the last bloody battle of the Jacobites on Culloden Moor

In 1996, after some disputes with authorities, a man known as Mr Brooks was taken to court for playing the pipes on Hampstead Heath, an act forbidden under a Victorian by-law stating the playing of any musical instrument is banned. Mr Brooks plead not guilty by, claiming the pipes are not a musical instrument, but instead a weapon of war , citing the case of James Reid as a precedent. The unanimous verdict was that the pipes are first and foremost musical instruments returning them form a weapon of war to their rightful place as a musical instrument.

Two prisoners escaped from York Castle during this period; George Mills and William Farrier. Nothing is known of Farrier’s escape, but George Mills escaped on 10th August 1747. He had been given permission to go to the ‘House’ in which debtors were confined ‘to drink with a person discharged from prison.’

Seeing a coach driving out of the prison yard, “he got behind it… and, having a new coat on, passed out unrecognised”. Nothing more was heard of him. Following the King’s Act of Indemnity of 1747, all the remaining prisoners had eventually been released by 1752.

The pipes in the pictures are on display in The National Museum of Scotland, and are said to have been played at Culloden on that faefule day in 1746........

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Henry Scrope's career in royal service ended unexpectedly on 6 August 1415 when he was executed for high treason in Southampton on the eve of Henry V's Agincourt campaign. His head was dispatched to York and displayed on Micklegate Bar, a particular humiliation since the family held property on Micklegate. Scrope's involvement in the ‘Southampton plot’ has never been fully explained. There were no obvious signs of disaffection towards Henry V, and no evidence that the king was neglecting him. Earlier in 1415 Scrope had made an indenture to serve with the king in France, and in his will he bequeathed to the king an image of the Virgin and asked him to be a good lord to his mother, his wife, and his heir. Scrope's implication in the plot is most likely to have been the result of his close family and financial ties with the other plotters, Richard, earl of Cambridge, Edmund (V) Mortimer, earl of March, and Sir Thomas Grey. Once the plot was discovered he claimed that he had intended to reveal it, but had not done so by the time the earl of March himself betrayed the conspirators to the king. He may, however, have felt that his prospects might improve if the younger and more easily influenced earl of March were on the throne.

Brigette Vale, "Scrope, Henry, third Baron Scrope of Masham (c. 1376–1415)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Article "Edward IV"

The fifteenth century English civil war that became known as the "Wars of the Roses" arose out of tension between the rival houses of Lancaster and York. Both dynasties could trace their ancestry back to Edward III. Both vied for influence at the court of the Lancastrian King Henry VI. The growing enmity that existed between these two noble lineages eventually led to a pattern of political manoeuvring, backstabbing, and bloodshed that culminated in a contest for the crown and Edward of York’s seizure of the throne to become Edward IV, first Yorkist King of England.

Born at Rouen on April 28, 1442, Edward was the eldest son of Richard, Duke of York, and Cecily Neville, "The Rose of Raby". Dubbed “The Rose of Rouen” due to his fair features and place of birth, Edward sported golden hair and an athletic physique. Growing to over six feet tall, the young Earl of March developed into the conventional medieval image of a military leader, ever ready to enter the fray. Intelligent and literate, Edward could read, write, and speak English, French, and a bit of Latin. He enjoyed certain chivalric romances and histories as well as the more physical aristocratic pursuits of hunting, hawking, jousting, feasting, and wenching. Edward proved time and again to be a valiant warrior and competent commander, personally brave and at the same time capable of understanding the finer points of strategy and tactics. As king, he displayed a direct straightforwardness and lacked much of the devious cunning exhibited by some of his contemporaries.

Young Edward of March became embroiled in the dynastic struggle between the Houses of Lancaster and York while still a teen. The family feud erupted into violence for the first time on May 22, 1455, when Yorkist forces under command of the Duke of York and the Earl of Warwick, and Lancastrian forces under command of the Duke of Somerset and King Henry, came to blows on the streets of St. Albans. After a disastrous debacle at Ludford Bridge on October 12, 1459, the Yorkist leaders fled for Calais and Ireland. Edward, Earl of March, was among those declared guilty of high treason by an Act of Attainder passed by Parliament on November 20.

In the summer of 1460, the Earl of March sailed from Calais to Sandwich with the Earls of Salisbury and Warwick and two-thousand men-at-arms. During Edward’s first proper taste of battle at Northampton in July of that year, he and the Duke of Norfolk co-commanded the vanguard that eventually breached the Lancastrian field fortifications, thanks in part to the traitorous actions of the Lancastrian turncoat Lord Grey of Ruthyn. After the Yorkist victory at Northampton, Edward’s father returned to England and made clear his desire to become king, but the assembled lords failed to support his claim.

With the contest between Lancaster and York still undecided, Edward was given his first independent command. He was sent to Wales to quell an uprising led by Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke, while his father marched out of London to tackle the northern allies of Henry VI’s Queen Margaret of Anjou. Drawn out of Sandal Castle by the appearance of a Lancastrian army, Richard of York fell in battle outside its walls on December 30, 1460. His severed head, along with those of his younger son Edmund, the Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, the Earl of Salisbury, soon adorned spikes atop the city of York’s Micklegate Bar. A paper crown placed on his bloody pate mocked the Duke’s failed bid for the throne. On the site of his father's death, Edward later erected a simple memorial consisting of a cross enclosed by a picket fence.

Now Duke of York, Edward gathered an army in the Welsh marches to avenge the deaths of his father and younger brother. Having spent his boyhood in Sir Richard Croft’s castle near Wigmore, Edward was well known in the region. He made ready to march toward London to support the Earl of Warwick, but then turned north to face an enemy force led by the Earls of Pembroke and Wiltshire. A strange sight greeted the anxious Yorkist troops at Mortimer's Cross that frosty dawn of February 2, 1461. Three rising suns shone in the morning sky. Quick to declare this meteorological phenomenon a positive omen, Edward announced that the Holy Trinity was watching over his army. After his victory at Mortimer’s Cross, Edward added the sunburst to his banner and badge. To make clear that the conflict had entered a more savage phase, Edward ordered the execution of Owen Tudor and nine other captured Lancastrian nobles. Tudor’s severed head went on display on the market cross at Hereford, where a mad woman combed his hair, washed his bloody face, and lit candles around the grisly memorial.

On February 17, the Earl of Warwick suffered his first defeat at the second battle St. Albans, brought about in part by treachery within his ranks. However, London refused to open its gates to Queen Margaret’s looting Lancastrian army, a force the citizens of the capital feared was full of northern savages. Reunited with King Henry, but frustrated by London’s mistrustful citizenry, the queen withdrew her forces toward York. Warwick and what troops he had left then met up with the victorious Edward at either Chipping Norton or Burford on February 22.

Greeted by cheers, Edward and the Earl of Warwick, marched into the capital on February 26. Warwick’s brother, the Chancellor George Neville, asked the people who they wished to be King of England and France. They answered with shouts for Edward. On March 4, 1461, the Duke of York rode from Baynard’s Castle to Westminster, where the Yorkist peers and commons and merchants of London formally proclaimed him King Edward IV.

The new Yorkist king’s official coronation was postponed while he prepared to set out in pursuit of Margaret and Henry. After sending Lord Fauconberg northward at the head of the king’s footmen on the 11th, Edward marched out of the capital on the 13th. He issued orders prohibiting his army from committing robbery, sacrilege, and rape upon penalty of death. He followed the trail of pillaged towns and razed homesteads left behind by Margaret’s northern moss-troopers.

On March 22, Edward received word that his enemies had taken up position behind the River Aire. On March 28, his vanguard tangled with a Lancastrian force holding the wooden span at Ferrybridge. Outflanking the defenders by sending a part of his army across the Aire at Castleford, Edward managed to push his men across the bridge and up the Towton road.

The two armies drew up in battle order on a snowy Palm Sunday, March 29, 1461. At some point during the morning the snow shifted, blowing into the faces of the Lancastrian soldiers. Taking advantage of the favourable wind, Fauconberg ordered his archers forward. The ensuing volley initiated the biggest, bloodiest, and most decisive battle of the Wars of the Roses.

Edward displayed steadfast courage as the battle raged. The young king rode up and down the line and joined in the melee whenever the ranks appeared ready to waver. No quarter was given, for both sides wished to settle the issue once-and-for-all, and the dead piled up between the opposing men-at-arms. At times, the fighting momentarily ceased while the bodies of the slain were pulled aside to make room for continued bloodshed.

After several hours of fierce fighting, the Yorkist line began to give way. However, the arrival of the Duke of Norfolk’s reinforcements tipped the balance in the Yorkist favour, and the exhausted Lancastrian army eventually faltered and broke. Many fleeing soldiers were cut down by Yorkist prickers in an area now known as Bloody Meadow. As was allegedly his habit when victorious, Edward may have given orders to spare the commons but slay the lords. Those Lancastrian nobles that survived the slaughter, along with King Henry, Queen Margaret, and their son Prince Edward, sought sanctuary in Scotland.

Victory at Towton established the Yorkist dynasty, but over the next three years Edward’s rule still faced a series of Lancastrian-inspired rebellions. Many of these uprisings against the Yorkist crown centred on Lancastrian strongholds in Northumberland. Most of Queen Margaret’s moves in the years immediately following the battle revolved around control of various castles, with some rather dubious aid from the Scots. In 1463, Margaret was finally forced to flee to France when Warwick and his brother routed her Scottish allies at Norham. Left behind by his queen, Henry VI held state in the gloomy fortress at Bamburgh. Warwick besieged this stronghold during the summer of 1464, and it became the first English castle to succumb to cannon fire. Captured in Clitherwood twelve months later and abandoned by his queen and allies, the Lancastrian king was sent to the Tower of London. Edward's throne finally seemed secure. However, Edward next faced threat from an unexpected corner as Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, turned on the man he helped make king.

In 1464, Edward secretly married Elizabeth Woodville, a comparatively lowborn Lancastrian widow. This caused a rift to form between the king and the Earl of Warwick. Edward's in-laws began to exert a growing influence over his court. Displeased with his own waning influence, in 1469 Warwick orchestrated a rebellion in the north. Edward remained in Nottingham while his Herbert and Woodville allies suffered defeat at Edgecote on July 26, 1469. The king then fell under Warwick's protection. On March 12, 1470, Edward was able to rout the rebels at the battle of Losecote Field, a moniker that arose from the fact that many men fleeing the battle discarded their livery jackets displaying the incriminating badges of Warwick and Edward's treacherous brother, the Duke of Clarence. With their treachery made plain, Warwick and Clarence sailed to France and formed an unlikely alliance with Margaret of Anjou. When Warwick returned to England with his new Lancastrian allies, Edward the lost support of the country and fled to the Netherlands. Warwick "The Kingmaker" reinstated the Lancastrian monarch during Henry's Readeption of 1470-1.

Edward IV spent his time in exile assembling an invasion fleet at Flushing and trying to woo his wayward brother back to the Yorkist cause. On March 14, 1471, Edward returned to the realm he claimed as his own, landing at Ravenspur. The Duke of Clarence promptly deserted Warwick and marched to his brother’s aid. Edward headed for London and entered the capital on April 11. Reinforced by Clarence’s troops, Edward took King Henry out of the capital and led a swelling army to face Warwick at Barnet. Edward suffered an early setback as he clashed with his one-time ally on that misty Easter morn of April 14, 1471. The Yorkist left collapsed, and the centre was slowly pushed back, but confusion caused by the obscuring fog eventually doomed Warwick's army. Warwick’s soldiers mistook the star with streams livery worn by the men of the Lancastrian Earl of Oxford for Edward’s sun with streams and loosed volleys of arrows into the approaching troops. With cries of “treason”, Oxford’s men left the field. Sensing the unease that rattled the Lancastrian ranks, Edward rallied his men and pressed the attack. Under this renewed pressure, Warwick’s army wavered and broke. The earl tried to flee the battlefield, but Yorkist soldiers pulled him from his saddle and despatched him with a knife thrust through an eye. Edward arrived on the scene too late to save Warwick from such an ignoble fate.

On May 4, Edward once more led his troops into battle, this time against Queen Margaret’s army at Tewkesbury. Margaret and her son, Prince Edward, had landed at Weymouth with a small force the same day of Edward’s victory over Warwick at Barnet. Under the leadership of the Duke of Somerset, the Lancastrian force moved toward Wales to try to join forces with Jasper Tudor. Wishing to bring Margaret’s army to battle before it crossed the Severn, Edward gave chase. He caught up with Somerset and Margaret at Tewkesbury. Though his army was slightly outnumbered, the Yorkist king once again triumphed over the Lancastrians. Margaret's son, Prince Edward, was captured and slain. Some Lancastrian fugitives, including the Duke of Somerset, tried to seek sanctuary in Tewkesbury Abbey. Dispute surrounds the exact details regarding what happened inside. Edward either granted pardons to those sheltering within the abbey walls, and then reneged on his promise, or he and his men entered the building with swords drawn. Either way, those captives that survived the slaughter were subsequently executed.

With the exception of quickly quelled Kentish and northern revolts, Edward’s triumph at Tewkesbury signalled the end of Lancastrian opposition to his reign. Margaret was captured and brought before Edward on May 12. She remained his prisoner until ransomed by King Louis XI of France. After making his formal entry into London on the 21st, Edward arranged the clandestine murder of poor King Henry VI. Edward’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, entered the Tower that evening. By the next morning, Henry, the potential focus of future Lancastrian resistance to Yorkist rule, was dead.

Following his final victory, Edward IV reigned over a relatively stable, peaceful, and prosperous kingdom. Once the Yorkist usurper secured his throne, he showed a ravenous appetite for the opulence of royalty and eventually became rather overweight. As king, he ordered the construction of several grand churches. He was also known as a patron of the arts. A lover of luxury and keenly aware of the political power of a majestic presence, one of Edward’s first acts a few months after his return to the throne was the expenditure of large sums of money on a magnificent new wardrobe. The other crowned heads of Europe all recognized him as legitimate King of England. His brief war with France in 1475 ended when Louis XI agreed to pay Edward an annual subsidy. By 1478 Edward had paid off the debts amassed by his one-time enemies. Unlike many of England’s medieval kings, he died solvent. He introduced several innovations to the machinery of government that the Tudors later adopted and developed. However, his second reign was not without its troubles. Woodville influence over his court caused tension between Edward and the nobility. In 1478, Edward’s in-laws manipulated him into eliminating his disgruntled brother George, the Duke of Clarence. Edward died on April 9, 1483.

Edward of York had a remarkable military career. He personally commanded and fought in five separate battles, and never lost a single one. As a leader of armed men, he often displayed daring and dash. As leader of the Yorkist cause, he exhibited a contradictory mixture of magnanimity and ruthlessness. As king, Edward IV worked to elevate the crown above the nobility and did much to restore a sound government. Unfortunately, his rash marriage bore bitter fruit, sowing the seeds of disaster for his young sons. Edwards’s death in 1483 left a minor as heir. The Duke of Gloucester was named protector of the princes Edward and Richard. Gloucester eventually had his nephews declared bastards and had himself proclaimed King Richard III. His nephews may have been murdered in the Tower, perhaps under Richard’s direct order. Faced with an invasion force led by Henry Tudor, and betrayed by his barons, Richard fell in battle at Bosworth Field. His death marked the end of the Yorkist dynasty and the ascendancy of the Tudors.

The Poleaxe of Edward IV

Being a fierce fighter as well as a skilled commander, Edward was said to be especially proficient with that uniquely knightly pole arm, the poleaxe. A magnificently decorated example currently residing in the Musee de l’Armee in Paris, France, has been ascribed to that most aristocratic of medieval monarchs. The connection to Edward IV is dubious, but this beautiful weapon certainly belonged to some extremely wealthy French, Dutch, or English nobleman of the late fifteenth century. Any consummate warrior and lover of luxury such as Edward of York would certainly have appreciated how the weapon’s combination of fine fighting qualities and rich ornamentation.

Having more reach than a sword, the poleaxe was often the preferred weapon when men of rank fought on foot. Topped by a spike, the axe head was backed by either a hammer or a quadrilateral beak. Mounted on a haft about six feet long and wielded in both hands, the poleaxe could cut, bludgeon, and stab. Even though the example attributed to Edward’s ownership sports fine decorative elements, it still exhibits all the qualities of a functional weapon. A pronged hammer backs a slightly curved axe blade. A wickedly sharp, stout spike thrusts out of the hexagonal central socket. A sturdy rondel acts as a hand-guard.

The lordly embellishments of the Edward IV poleaxe set it apart from simpler period examples. It is profusely decorated with chiselled gilt bronze. The iron components emerge from the throats of stylized beasts. The socket is further decorated with engraved foliage, a knot of flowers, and a cluster of fiery clouds. The rondel takes the form of a full-blown heraldic rose. The assumption that this weapon once belonged to Edward IV arose from the fact that it exhibits the symbols of rose and flame, but such ornamentation was common in the fifteenth century. Still, this imagery does echo the white rose en soliel device Edward used on his banner and badge, so it may just be a weapon once wielded by that accomplished Yorkist warrior.

Sources

Arms and Armour from the 9th to the 17th Century by Paul Martin

Arms and Armour of the Western World by Bruno Thomas

Battle of Tewkesbury 4th May 1471 by P.W. Hammond, H.G. Shearring, and G. Wheeler

Battles in Britain and Their Political Background:1066-1746 by William Seymour

The Book of the Medieval Knight by Stephen Turnbull

Campaign 66: Bosworth 1485: Last Charge of the Plantagenets by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 120: Towton 1461: England's Bloodiest Battle by Christopher Gravett

Campaign 131: Tewkesbury 1471: The Last Yorkist Victory by Christopher Gravett

Men-at-Arms 145: The Wars of the Roses by Terence Wise

The Military Campaigns of the Wars of the Roses by Philip A. Haigh

Who's Who in Late Medieval England by Michael Hicks

#writers on tumblr#writerscommunity#writers and poets#nonfiction#article#history#medieval#edward iv#military history#biography

1 note

·

View note

Text

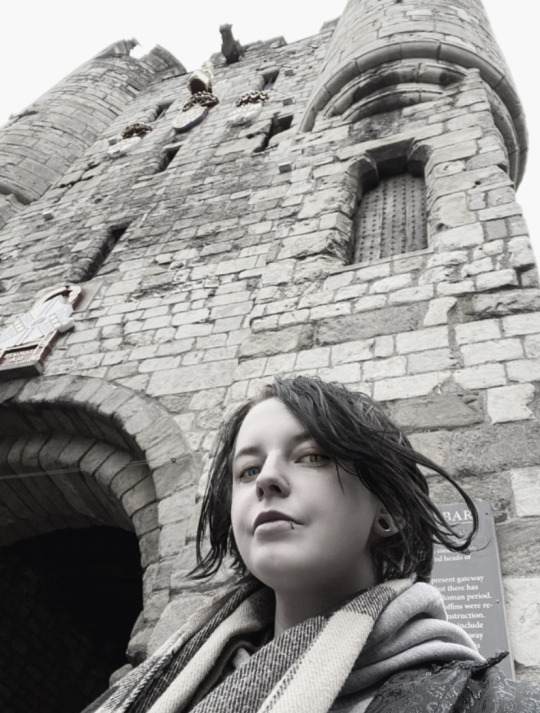

I didn’t manage to cosplay Richard iii (the version of Richard in Requiem of the Rose King) to pay homage upon the place his head was displayed as a rebel and traitor within his own home, York, fuelled with obscene rumours to the point where it was said he was in his parents womb for 2 years and a demonic monster over his body, and it was believed, over trying to rule during the War of the Roses.

Amongst downfalls, rumours are spread to ready a more secure a more loved position and angelic assumed appearance for the ones taking over as not to allow for a mutiny essentially and uproar against the new ones replacing them to take over, and cover ups to present a new line as Good, and only Good for the people.

It is said he obviously had his wrongs, but comparably it was better to a lot during that time of who was veering for power.

There’s a lot of false poison placed as fact, much which was never proved, and much which was just obvious bull now we look at it these days, and this was done to remove the return of certain families during War which threatened those who wanted to have their status.

The utmost end point is to secure a throne, and people will do absolutely anything.

This place is known as the Micklegate Bar, many people have passed beneath it and many heads have been presented upon it, it is the southern entrance to York.

I made it here, and I’m glad. A rich piece of history of a truly awful time upon these islands.

#richard plantagenet#richard iii#king richard iii#micklegate bar#war of the roses#battle of bosworth#city of york#yorkshire#Yorkshire history#York history#history#listed building#Yorkist dynasty#my photography#my photos#my face#requiem of the rose king#bara o no souretsu#baraou no souretsu#aya kanno#anime#historical anime#historical manga

41 notes

·

View notes

Photo

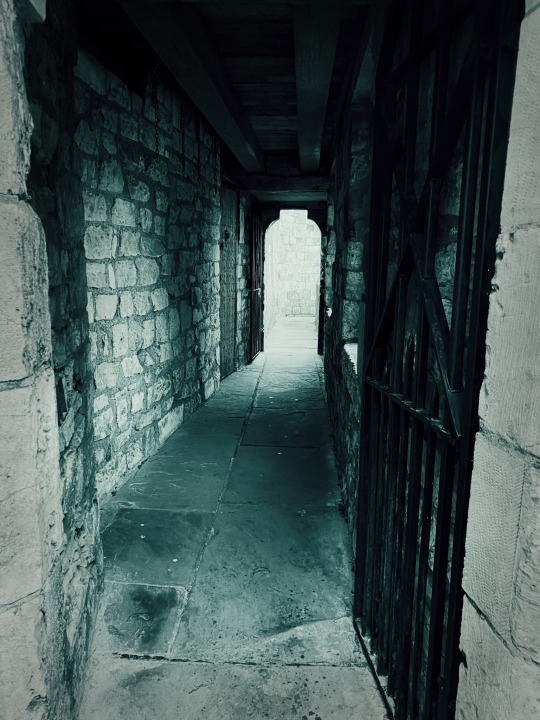

The gatehouse of Micklegate, the Micklegate Bar (Micklagate meaning ‘great street’ in Old Norse, ‘mykla gata’, from the time of the Viking rule of Jorvik, and ‘Bar’ referring to the gatehouse itself).

After the battle of Wakefield in the Wars of the Roses in 1460, the heads of the defeated Yorkist leaders; Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, and Richard Neville, 5th Earl of Salisbury, were displayed above the gatehouse.

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Micklegate Bar currently under repair

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Royals used to get beheaded now they cry about eggs

78 notes

·

View notes

Text

Micklegate Bar, the most important medieval city gate of York. - 1890's

#vintagephotos#oldphotos#history#history photo#history photos#sealedintime#photography#historyphotos#photos#rarephotos#rare photos#sealed in time

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

King Charles III and Queen Camilla arrive for a ceremony at Micklegate Bar, where the Sovereign is traditionally welcomed to York, before they unveil a statue of Queen Elizabeth II at York Minster, 09.11.2022

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solidarity with the arrested egg-thrower of York, can't believe the servile obsequience of the ones who tried to drown them out.

12 notes

·

View notes

Photo

York, England

Police detain a protester after he appeared to throw eggs at King Charles III and the queen consort as they arrived for a ceremony at Micklegate Bar Photograph: Jacob King/PA

Not all heroes wear capes

8 notes

·

View notes