#precolumbian art

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Cueva de los Manos, Santa Cruz, Argentina

The handprints were stenciled using bone pipes to spray the pigment. They were placed in waves over the course of over 6000 years.

#this is one of the artworks i think about the most#and one that is a must see for me#cueva de los manos#argentina#art history#precolumbian#cave art#hands#handprints#art#history#precolumbian art#precolumbian history#cave paintings

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

3D Reconstruction of Tenochtitlán by Thomas Kole

#history#art#mesoamerica#archaeology#antiquities#mexico#aztec#indigenous#indigenous history#precolumbian#precolumbian art#tenochtitlan#my posts

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Frog jar, Moche culture, 100-800 AD

from Dumbarton Oaks

200 notes

·

View notes

Text

Larco Museum, precolumbian pottery - Lima, 2014

#picofthenight#travel#peru#original photographers#photographers on tumblr#ancient art#pottery#pre columbian#precolumbian art#art#ancient pottery#photoofthenight

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

tumi (ceremonial knife) | c. 1100 - 1470 CE | peru, chimú culture

Naymlap, the heroic founder-colonizer of the Lambayque Valley on the north coast of Peru, is thought to be the legendary figure represented on the top of this striking gold tumi.

in the art institute of chicago collection

#peru#peruvian art#precolumbian#precolumbian art#south american art#late intermediate peru#middle ages

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Evil Omaru time (not canon)

#art#clip studio paint#lgbtq#artists on tumblr#digital art#oc art#comics#ocs#oc#precolumbian#precolumbian art#fanart#the first draconic#cascades#penumbra#procreate#lorraverse#nmauve#ndotmov#dragon#dragon oc#god oc#fantasy#sci fi comic#sci fi fantasy#concept doodles#not canon

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Symbolism & Mythology in Pre-Columbian Art

Pre-Columbian art is a rich tapestry woven from the diverse cultures that flourished in the Americas before the arrival of European colonizers. Civilizations such as the Maya, Aztecs, and Incas imbue their artworks with complex symbolism and mythology that reflect their religious beliefs, social structures, and cosmological views. This article explores pre-Columbian art’s intricate symbolism and mythology, shedding light on the deeper meanings behind these ancient masterpieces.

The Maya: A World of Gods and Kings

The Maya civilization, known for its sophisticated writing system and astronomical knowledge, produced art with symbolic meanings. Maya art centrally explores the concept of the cosmos, which they divided into three realms: the heavens, the earth, and the underworld, or Xibalba. They often represent this tripartite division through vertical compositions in their art.

A prominent example is the depiction of the World Tree, or Wacah Chan, which connects the three realms. The tree’s roots extend into the underworld, its trunk symbolizes the earthly plane, and its branches reach the heavens. Artists often show the World Tree with a serpent at its base, representing the underworld, and a bird at its top, symbolizing the celestial realm. This motif underscores the Maya belief in the interconnectedness of all levels of the universe.

Kings and deities are another significant focus in Maya art. Rulers were often depicted in elaborate headdresses and costumes, symbolizing their divine right to govern. The headdresses frequently featured motifs such as jaguars, serpents, and birds, each representing different aspects of power and the sacred. The Maya associated the jaguar with strength and the underworld, while they linked the serpent to rebirth and fertility.

The Aztec: A Pantheon of Powerful Deities

The Aztec civilization, which dominated central Mexico in the 14th to 16th centuries, left behind a wealth of art that provides insight into their complex religious beliefs. The Aztecs worshipped a pantheon of gods, each associated with different aspects of life and nature. These deities were often depicted in their art, each with distinctive symbols that conveyed their powers and attributes.

Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, is one of the most prominent figures in Aztec art. Artists often depict him as a hummingbird or an eagle, animals associated with the sun and warriors. They load his images with symbols of warfare, such as shields, spears, and hearts, representing the sacrifices made to sustain him. This god’s representation underscores the Aztec emphasis on warfare and human sacrifice as central elements of their religious practice.

Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god, is another crucial figure in Aztec mythology. Represented as a serpent adorned with quetzal feathers, Quetzalcoatl symbolizes the dual aspects of the divine and the terrestrial. The feathers signify the heavens, while the serpent represents the earth. This duality reflects the Aztec belief in the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth.

The Inca: Divine Kingship and the Natural World

In the Andean highlands, the Inca civilization created art that reflects their reverence for nature and their concept of divine kingship. The Inca believed that their emperor, or Sapa Inca, was a descendant of the sun god Inti, and this divine connection is evident in their art.

Sun motifs are prevalent in Inca art, often appearing in gold artifacts and architectural designs. Gold, believed to be the sun’s sweat, was a sacred material used to create elaborate ceremonial objects. The sun disk, or Inti Raymi, commonly represents the sun god and his life-giving energy. These symbols reinforced the emperor’s divine right to rule and the central role of the sun in Inca cosmology.

Inca art also reflects a deep connection to the natural world. Animals such as llamas, condors, and pumas are frequently depicted, each holding specific symbolic meanings. The llama, a vital animal for transport and agriculture, symbolizes prosperity and sustenance. Soaring high in the Andes, the condor is associated with the heavens and acts as a messenger between the earthly and divine realms. The puma represents strength and is often associated with the earth.

Symbolism Across Civilizations: Common Themes

While each pre-Columbian civilization had unique artistic traditions, some common themes and symbols transcend cultural boundaries. One such theme is using animals to represent divine or natural forces. Jaguars, serpents, eagles, and other animals frequently appear in the art of different cultures, each imbued with specific symbolic meanings. These animals often act as intermediaries between the human and the divine, reflecting the belief in a world where nature and the supernatural are intertwined.

Another common motif is the depiction of deities and rulers with elaborate regalia that signify their power and divine status. These figures are often shown with headdresses, jewelry, and weapons, symbolizing their connection to the gods and authority over the earthly realm. Using such symbols helped legitimize their rule and convey their role as intermediaries between the human and the divine.

Conclusion

The art of pre-Columbian civilizations is a testament to their rich mythological and symbolic traditions. Through intricate depictions of gods, animals, and cosmological concepts, these artworks provide a window into ancient peoples’ spiritual and cultural lives. By understanding the symbolism and mythology embedded in these pieces, we can better appreciate the complexity and depth of pre-Columbian art and the civilizations that created it.

Why a Certificate of Authenticity is Essential When Purchasing Artifacts

Research Academic Papers and News Articles

#ancient art#ancient history#archaeology#pre-columbian#art history#artifacts#inca#aztec#mayan#south america#Precolumbian art#Pre-columbian art#Pre-columbian artifacts

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mayan plate with monkey tail in spiral

Date: c. 300-850 AD

Collection: Museo Nacional de Antropología, México

#fine art#art#artwork#mayan#mayan art#monkeys#monkey#pre columbian#precolumbian#plate#monkey plate#mayan plate#art of the day#spiral#ancient art#mayan culture#mexican art#antiquities

4K notes

·

View notes

Photo

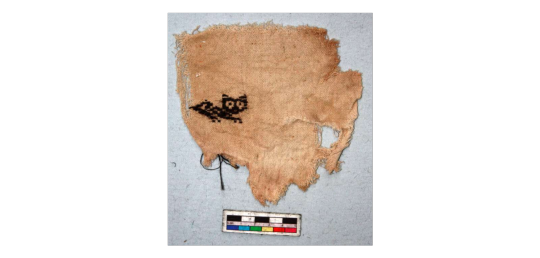

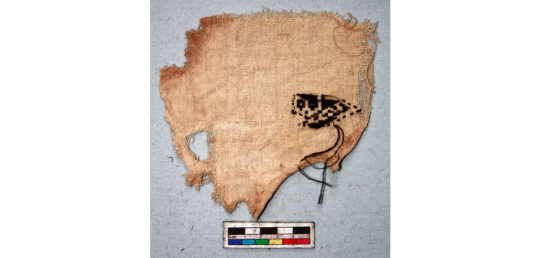

ohhhh noooo it has the saddest eyes

textile

Cultures/periods: Chimu (?) Chancay (?)

Production date: 900-1430

Made in: Peru

Provenience unknown, possibly looted

Textile fragment; cotton plain weave ground with paired warps; camelid supplementary weft patterning; feline figure; cream and black.

British Museum

#precolumbian#Precolumbian art#andean#Andean textiles#textile art#chancay#chimu#Peru#peruvian art#Peruvian textiles

33K notes

·

View notes

Text

Lobster Vessel

Ceramic vessel formed as a spiny lobster. Nazca culture.

Penguin Vessel

Painted ceramic vessel in the shape of a Humboldt penguin. Nazca culture.

Orca Vessel

Ceramic vessel depicting an orca. Nazca culture.

166 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quetzalcoatl as depicted in Codex Borbonicus

#digital art#my art#artists on tumblr#digital artist#art#trans artist#illustration#mythology and folklore#fanart#mesoamerica#quetzalcoatl#aztec gods#aztec mythology#aztec#aztec culture#precolumbian#azteca

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gold filigree pendant of a frog, Cocle culture, Panama, 500-1000 AD

from The Art Institute of Chicago

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

I have compulsively pestered the institution, with citations.

one of which was THIS Nasca pot, held at the Art Institute of Chicago. Same rough timeframe! Absolutely no ambiguity!

(I also found a few books on Andean textiles that I didn't already own. Contemplating whether they are within my nonexistent budget.)

I am very neurotypical about all this (sarcasm)

I was just in Detroit, for reasons, and stopped in at their Detroit Institute of Arts

and now I have to compose an email to the curation team

because I believe that they are Wrong about this pot:

The display label said “Bowl Painted with Children Spinning Yarn, about 400, Ceramic, Unknown artist, Nasca culture, Peru.” (The collection label is “Bowl Decorated with Men Spinning, between 200 BCE and 200 CE, Nazca, Precolumbian” which is a weird discrepancy but not the point)

The point is, this simply isn’t what spinning looks like. I don’t think anyone in human history has attempted to make yarn this way. It is certainly not how the Nasca bead spindle or the modern Southern Quechua pushka are used.

I’m fairly certain that they are actually holding slings, slingshots. Virtually unchanged from the Nasca culture to the modern Southern Quechua, with a tassel at one end and a slit pouch.

@tlatollotl care to give me a vibe check? before I compulsively pester an institution?

#nasca#nazca#peruvian textiles#quechua#quechua art#museum#museum curator#precolumbian#precolumbian art#waraka#huaraca#honda#sling#slinging#slingshot#Peru#andes

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Female figurine from Guerrero, Mexico, Xalitla region, crafted in the Xochipala style, dating from approximately 1500-500 BC, made of earthenware with pigment decoration. Collection & Credit: The Getty.

The Xochipala style emerged in the region now known as Guerrero, Mexico, around 1500-500 BC. This period in Mesoamerican history precedes the classic civilizations like the Maya or Aztec.

#archaeology#ancient Mexico#ancient history#xochipala#mesoamerica#ancient Art#ceramic art#precolumbian#figurine#artifact#history#Guerrero

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

tripod vessel with slab legs | c. 300 - 600 CE | mayan (modern-day guatemala)

"The painted body and lid of this vessel depict white water lilies floating against a green blue background; the water lily was seen as a plant that connects the underworld of water to the air of our world above."

in the detroit institute of arts collection

268 notes

·

View notes

Text

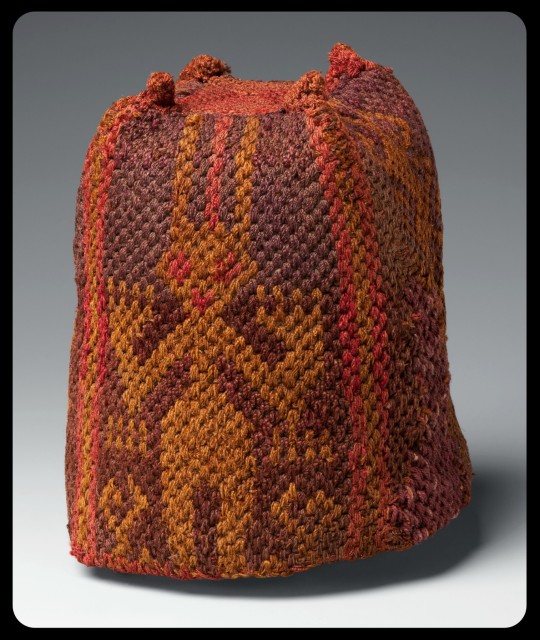

Four-Cornered Hats from Peru and Bolivia, c.600-800 CE: these colorful, finely-woven hats are at least 1,200 years old, and they were crafted from camelid fur

Above: four-cornered hats made by the Wari Empire of Peru (top) and the Tiwanaku culture of Bolivia (bottom) during the 7th-9th centuries CE

Often referred to as "four-cornered hats," caps of this style were widely produced by the ancient Wari and Tiwanaku cultures, located in what is now Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

Finely woven, brightly colored hats, customarily featuring a square crown, four sides, and four pointed tips, are most frequently associated with two ancient cultures of the Andes: the Wari and the Tiwanaku. The Wari Empire dominated the south-central highlands and the west coastal regions of what is now Peru from 500–1000 A.D. The Tiwanaku occupied the altiplano (high plain) directly south of Wari-populated areas around the same time, including territory now part of the modern country of Bolivia.

Above: pair of four-cornered hats made by the Wari people of Peru, c.600-900 CE

Both cultures used the hair of local camelids (i.e. llamas, alpacas, or vicuñas) to produce their hats. The hair was harvested, crafted into yarn, and treated with colorful dyes, and the finished yarn was then woven and/or knotted into caps and other textiles. Four-cornered hats from both cultures were often decorated with similar stylistic elements, including geometric patterns (particularly diamonds, crosses, and stepped triangles) and depictions of zoomorphic figures such as birds, lizards, and llamas with wings.

Above: four-cornered hats made by the Tiwanaku people of Bolivia, c.600-900 CE

The two cultures used different techniques to construct/assemble their hats, however:

Although they shared certain technological traditions, such as complex tapestry weaving and knotting techniques, the Wari and the Tiwanaku utilized significantly different construction methods to create four-cornered hats. Wari artists typically fashioned the top and corner peaks as separate parts and later assembled them together. Tiwanaku artists generally knotted from the top down, starting with the top and four peaks, to create a single piece.

Above: a four-cornered hat from Bolivia or Peru, made by either the Tiwanaku or Wari culture, c.500-900 CE

There is evidence to suggest that four-cornered hats were often worn as part of daily life, as this publication explains:

Many have indelible marks of hard usage: wear along the edges and folds, a crusting of hair oil on the inside, remnants of broken chin ties, and ancient mends.

Above: a pair of hats made by the Wari culture of Peru, c.600-800 CE

Above: more hats from the Wari culture of Peru, c.700-900 CE, with colorful tassels decorating the four peaks of each cap

The oldest known/surviving examples of the Andean four-cornered hat date back to nearly 1,700 years ago. They began to appear along the northern coast of Chile at some point during the 4th century CE; these early hats had an elongated design with four short peaks, and they are typically associated with the Tiwanaku culture.

Above: this early example of a four-cornered hat was created by the Tiwanaku culture between 300-700 CE

Why indigenous artifacts should be returned to indigenous cultures.

Sources & More Info:

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Four-Cornered Hats 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12

Museum Publication: Andean Four-Cornered Hats (PDF available here)

Emory University: Four-Cornered Pile Hat

Metropolitan Museum of Art: Andean Textiles

#archaeology#artifact#anthropology#history#four-cornered hat#tiwanaku#wari#art#textile art#hats#peru#bolivia#precolumbian#andes#alpaca#fiber art#crafting#pile hats#ancient textiles#indigenous art

217 notes

·

View notes