#rainer c fritz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Rainer C. Fritz, 1979

Album art for Prophetic Dream by Akira Inoue

291 notes

·

View notes

Text

Your hosts travel to West Germany for EIN TOTER HING IM NETZ aka THE CORPSE IN THE WEB (1960) from director Fritz Böttger! This "nudie" horror film offers an early attempt at bridging sex appeal and horror, but is not necessarily successful at it.

Context setting 00:00; Synopsis 11:00; Discussion 16:48; Ranking 31:05

#podcast#west germany#german horror#ein toter hing im netz#the corpse in the web#horrors of spider island#fritz botger#wolf c hartwig#willy mattes#karl bette#georg krause#haidi genee#alex d'arcy#barbara valentin#harald marech#rainer brandt#elfie wagner#dorothee glocklen#helga franck#helga neuner#gerry sammer#eva schauland#helma vandenberg#walter faber#SoundCloud

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Literature and Philosophy

MA IN LITERARY STUDIES

Literature and Philosophy (EN71021A): Course Outline Spring 2019

Tutor: Julia Ng

Teaching Mode: 2-hour seminar

Seminar Wednesday 9-11

St James Hatcham G02

NB: Please acquire a print copy of Walter Benjamin’s Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. J. Osborne (Verso, 1998/2009), as we will be studying this text in its entirety. Other materials for this course will be posted to the course’s learn.gold page.

Week 1, Wednesday 16

th

January – Introduction; “intention” in Brentano and Husserl

Introductory discussion

Franz Brentano, “The Distinction between Mental and Physical Phenomena,” in Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint [1874], trans. A. C. Rancurello, D. B. Terrell and L. L. McAlister (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1995), Bk. 2, chap. 1, pp. 59-77.

Edmund Husserl, “Philosophy as a Rigorous Science," in Phenomenology and the Crisis of Philosophy, trans. Quentin Lauer (Harper & Row, 1965), section on “Naturalistic Philosophy,” pp. 79-122.

Week 2, Wednesday 23th January – Husserl

Edmund Husserl, “Philosophy as a Rigorous Science," in Phenomenology and the Crisis of Philosophy, trans. Quentin Lauer (Harper & Row, 1965), excerpt from “Historicism and Weltanschauung Philosophy,” pp. 122-129.

Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy, I, trans. F. Kersten (Martinus Nijhoff, 1983), §§87-90, 93-95.

Week 3, Wednesday 30th January – Benjamin

Benjamin, OGT, “Epistemo-Critical Prologue”

References

Plato, Symposium

Scheler, “On the Tragic”

Wek 4, Wednesday 6th February – Benjamin

Benjamin, OGT, “Trauerspiel and Tragedy,“ I

References

Schmitt, Political Theology

Gryphius, Leo Armenius

Calderon, Life is a Dream

Week 5, Wednesday 13th February – Benjamin

Benjamin, OGT, “Trauerspiel and Tragedy,“ II

References

Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

Lukács, Soul and Forms

Rosenzweig, The Star of Redemption

Scheler, “On the Tragic”

Benjamin, “Fate and Character”; “Toward the Critique of Violence”

Week 6, Wednesday 20th February

Tutorial Week – No seminar

Week 7, Wednesday 27th February – Benjamin

Benjamin, OGT, “Trauerspiel and Tragedy,“ III; „Allegory and Trauerspiel,“ I

References

Shakespeare, Hamlet

Panofsky and Saxl on Dürer’s Melancholia I

Giehlow on Melancholia I; The Humanist Interpretation of Hieroglyphs

Warburg

Freud, “Mourning and Melancholia”

Week 8, Wednesday 6th March – Benjamin

Benjamin, OGT, “Allegory and Trauerspiel,“ II and III

References

Benjamin, “On Language as Such and on the Language of Man”; “The Role of Language in Trauerspiel and Tragedy”; “Trauerspiel and Tragedy”

Gryphius, Leo Armenius

Week 9, Wednesday 13th March – Adorno

Adorno, “The Actuality of Philosophy” (May 2, 1931), in Telos 31 (1977), 120-133.

Adorno, “The Idea of Natural History” (1932), in Telos 60 (1984), 111-124.

Week 10, Wednesday 20th March – Adorno

Adorno, “III.2 World Spirit and Natural History,” in Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton, Continuum, 1973, pp. 300-360.

Week 11, Wednesday 27th March – Conclusion

General discussion

Preparatory Reading

Gryphius, Leo Armenius

Calderon, Life Is A Dream

Shakespeare, Hamlet

Hofmannsthal, The Tower

Further Reading

Benjamin

On Language as Such and on the Language of Man (1916)

The Role of Language in Trauerspiel and Tragedy (1916)

Trauerspiel and Tragedy (1916)

Fate and Character (1919)

Toward the Critique of Violence (1921)

Calderon's El mayor monstrue, los celos and Hebbel's Herodus and Mariamne (1923)

General

Adorno, Theodor. "Portrait of Walter Benjamin," in: Prisms. Trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber. MIT Press, 1981.

Adorno, Theodor. Against Epistemology: A Metacritique. Trans. Willis Domingo. Oxford: Blackwell, 1982.

Adorno, Theodor, and Walter Benjamin. The Complete Correspondence, 1928-1940. Ed. Henri Lonitz. Trans. Nicholas Walker. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1999.

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life, Stanford UP, 1998.

Cascardi, Anthony J. "Comedia and Trauerspiel: On Benjamin and Calderón." Comparative Drama 16:1 (1982), 1-11.

Cobb-Stevens, Richard. “Husserl on Eidetic Intuition and Historical Interpretation,” American Catholic Philosophical Quarterly 66 (1992): 261–75.

Comay, Rebecca. "Mourning Work and Play," in Research in Phenomenology 23 (1993), pp. 105-130.

Drummond, John. “Husserl on the Ways to the Performance of the Reduction,” Man and World 8 (1975): 47–69.

Drummond, John. “The Structure of Intentionality,” in The New Husserl, ed. D. Welton (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 65–92.

Derrida, Jacques. "Force of Law."

Fenves, Peter. "Marx, Mourning, Messianity," in: Hent de Vries/Samuel Weber (Hg.): Violence, Identity and Self-Determination, Stanford, 1997, 253–270.

Fenves, Peter. "Tragedy and Prophecy in Benjamin’s 'Origin of the German Mourning Play,'" in: Arresting Language. From Leibniz to Benjamin, Stanford UP, 2001, 227–248.

Foster, Roger. Adorno: The Recovery of Experience. SUNY Press, 2007.

Freud, Sigmund. "Mourning and Melancholia," The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, XIV. The Hogarth Press, 1957, pp. 237-258.

Friedlander, Eli. "On the Musical Gathering of Echoes of the Voice: Walter Benjamin on Opera and the Trauerspiel." The Opera Quarterly, vol. 21 no. 4 (2005), pp. 631-646.

Geulen, Eva. The End of Art : Readings in a Rumor after Hegel. Stanford University Press, 2006.

Giehlow, Karl, and Robin Raybould. The Humanist Interpretation of Hieroglyphs in the Allegorical Studies of the Renaissance with a Focus on the Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I. Brill, 2015.

Hamacher, Werner. "Guilt History."

Hanssen, Beatrice. Walter Benjamin's Other History : of Stones, Animals, Human Beings, and Angels. University of California Press, 1998.

Hanssen, Beatrice. "Philosophy at Its Origin: Walter Benjamin’s Prologue to the 'Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels,'" in: Modern Language Notes 110 (1995), 809–833.

Haverkampf, Hans-Erhard. Benjamin in Frankfurt : Die Zentralen Jahre 1922-1932. Societäts-Verlag, 2016.

Helmling, Steven. "Constellation and Critique: Adorno's Constellation, Benjamin's Dialectical Image." Postmodern Culture 14:1 (2003).

Johnson, Barbara, The Wake of Deconstruction, Cambridge, Mass, 1994.

Johnson, Christopher D. “Configuring the Baroque: Warburg and Benjamin.” Culture, Theory and Critique, vol. 57, no. 2, 2016, pp. 142–165.

Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King's Two Bodies : a Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton University Press, 1997.

Klibansky, Raymond; Panofsky, Erwin; Saxl, Fritz. Saturn and Melancholy : Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion, and Art. Basic Books, 1964.

Lacan, Jacques. "Desire and the Interpretation of Desire in Hamlet," in: Shoshana Felman (ed.): Literature and Psychoanalysis. The Question of Reading: Otherwise, Baltimore, 1982, 11–52.

Lindner, Burkhardt. "Habilitationsakte Benjamin. Über ein 'akademisches Trauerspiel' und über ein Vorkapitel der "Frankfurter Schule" (Horkheimer, Adorno)/"Walter Benjamins's attempt of a Habilitation. On an 'academic Trauerspiel' and on other preliminaries of the "Frankfurter Schule" (Horkheimer, Adorno)." In: Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik 14.53 (1984): 147-166.

Lukács, György. Soul and Form. MIT Press, 1978.

Lukács, György. Theory of the Novel.

Marin, Louis. Food for Thought. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

McFarland, James. “Presentation.” Constellation: Friedrich Nietzsche and Walter Benjamin in the Now-Time of History. Fordham University Press, 2012, pp. 67-102 (Chapter 2).

McLaughlin, Kevin. "Benjamin's Barbarism." The Germanic Review: Literture, Culture, Theory, 81:1 (2006), 4-20.

Menke, Christoph, and James. Phillips. Tragic Play : Irony and Theater from Sophocles to Beckett. Columbia University Press, 2009.

Merback, Mitchell B. Perfection's Therapy : an Essay on Albrecht Dürer's Melencolia I. Zone Books, 2017.

Miller, J. Hillis. »The Two Allegories«, in: Morton Bloomfield (ed.): Allegory, Myth and Symbol, Cambridge, 1981, 355–370.

Mininger, J. D., and Jason Michael Peck. German Aesthetics : Fundamental Concepts from Baumgarten to Adorno. Bloomsbury, Bloomsbury Academic, 2016.

Nägele, Rainer. Theater, Theory, and Speculation: Walter Benjamin and the Scenes of Modernity, Baltimore, 1991.

Newman, Jane O. Benjamin's Library: modernity, nation, and the Baroque. Cornell UP, 2011.

Newman, Jane O. "Tragedy and 'Trauerspiel' for the (Post-)Westphalian Age." In: Renaissance Drama 40 (2012), pp. 197-208.

Newman, Jane. “Enchantment in Times of War: Aby Warburg, Walter Benjamin, and the Secularization Thesis.” Representations, vol. 105, no. 105, 2009, pp. 133-0_4.

Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

Pensky, Max. Melancholy Dialectics: Walter Benjamin and the Play of Mourning. U Mass Press, 1993.

Plato, Symposium.

Rosenzweig, Franz, and Barbara Ellen Galli. The Star of Redemption. University of Wisconsin Press, 2005.

Scheler, Max. "On the Tragic." CrossCurrents 4.2 (1954), 178-191.

Schmitt, Carl, et al. Hamlet or Hecuba : the Intrusion of the Time into the Play. Telos Press, 2009.

Schmitt, Carl. Political Theology : Four Chapters on the Concept of Sovereignty. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Szondi, Peter. An Essay on the Tragic. Stanford University Press, 2002.

Weber, Samuel. Benjamin's -Abilities. Harvard University Press, 2008.

Willard, Dallas. “The Paradox of Logical Psychologism: Husserl’s Way Out,” American Philosophical Quarterly 9 (1972): 94–100.

Woodfield, Richard (ed.) Art history as cultural history: Warburg's projects. G+B Arts International, 2000.

Learning Outcomes

- You will have a grasp of the place of literature in the modern Continental philosophy tradition.

- You will have a good understanding of how this tradition challenges and transforms Classical philosophical conceptions of literature.

- You will be able to expound and analyse the textual and conceptual styles of the three key thinkers on the course.

- You will have a sound grasp of the literature of and on both the broad relationship between literature and philosophy, and the three specific thinkers addressed on the module.

- You will be able to use the ideas and texts explored in the module to inform your readings in literary and cultural texts.

Assessment Criteria

- Students should show a clear command of traditional conceptions of the literary in the history of philosophy, and of how the modern Continental tradition challenges these.

- Students should show a detailed critical knowledge of at least one of the module’s key thinkers’ ideas.

- Students should show a knowledge and capacity to use a good range of secondary literature on both general issues in the field and on the specific thinkers and texts they address.

- Students should be able to read the relevant texts from both literary critical and conceptual perspectives.

- Students should show an awareness of the relevance of the issues and texts studied on the course to contemporary debates in literary theory.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

1861 Georges Méliès 1875 D.W. Griffith 1879 Victor Sjöström 1880 Tod Browning 1881 Cecil B. DeMille 1884 Robert Flaherty 1885 Allan Dwan / Sacha Guitry / G.W. Pabst / Erich von Stroheim 1886 Michael Curtiz / Henry King / John Cromwell 1887 Raoul Walsh 1888 F.W. Murnau 1889 Charles Chaplin / Jean Cocteau / Carl Theodor Dreyer / Victor Fleming / Abel Gance / James Whale 1890 Clarence Brown / Fritz Lang 1892 Ernst Lubitsch 1893 William Dieterle 1894 Frank Borzage / John Ford / Jean Renoir / King Vidor / Josef von Sternberg 1895 Buster Keaton 1896 Julien Duvivier / Howard Hawks / Leo McCarey / Dziga Vertov / William Wellman 1897 Frank Capra / Douglas Sirk 1898 René Clair / Sergei Eisenstein / Henry Hathaway / Mitchell Leisen / Kenji Mizoguchi / Preston Sturges 1899 George Cukor / Alfred Hitchcock 1900 Luis Buñuel / Mervyn LeRoy / Robert Siodmak 1901 Robert Bresson / Vittorio De Sica 1902 Emeric Pressburger / Max Ophüls / William Wyler 1903 Vincente Minnelli / Yasujiro Ozu 1904 Delmer Daves / Terence Fisher / George Stevens / Jacques Tourneur / Edgar G. Ulmer 1905 Mikio Naruse / Michael Powell / Otto Preminger / Jean Vigo 1906 Jacques Becker / Marcel Carné / John Huston / Anthony Mann / Carol Reed / Roberto Rossellini / Luchino Visconti / Billy Wilder 1907 Henri-Georges Clouzot / Joseph H. Lewis / Jacques Tati / Fred Zinnemann 1908 Tex Avery / Edward Dmytryk / Phil Karlson / David Lean / Manoel de Oliveira 1909 Elia Kazan / Joseph Losey / Joseph L. Mankiewicz 1910 John Sturges / Akira Kurosawa 1911 Jules Dassin / Nicholas Ray 1912 Michelangelo Antonioni / Samuel Fuller / Gene Kelly / Alexander Mackendrick / Don Siegel 1913 André de Toth / Mark Robson / Frank Tashlin 1914 Mario Bava / William Castle / Robert Wise 1915 Orson Welles 1916 Budd Boetticher / Richard Fleischer / George Sidney 1917 Maya Deren / Jean-Pierre Melville 1918 Robert Aldrich / Ingmar Bergman 1920 Federico Fellini / Eric Rohmer 1921 Luis García Berlanga / Miklós Jancsó / Chris Marker / Satyajit Ray 1922 Blake Edwards / Jonas Mekas / Pier Paolo Pasolini / Arthur Penn / Alain Resnais 1923 Ousmane Sembene / Seijun Suzuki 1924 Stanley Donen / Sidney Lumet 1925 Robert Altman / Claude Lanzmann / Sam Peckinpah / Maurice Pialat 1926 Roger Corman / Shohei Imamura / Jerry Lewis / Andrzej Wajda 1927 Kenneth Anger / Ken Russell 1928 Stanley Kubrick / Jacques Rivette / Nicolas Roeg / Agnès Varda / Andy Warhol 1929 Hal Ashby / John Cassavetes / Alejandro Jodorowsky / Sergio Leone 1930 Claude Chabrol / Clint Eastwood / John Frankenheimer / Kinji Fukasaku / Jean-Luc Godard / Frederick Wiseman 1931 Jacques Demy / Mike Nichols / Ermanno Olmi 1932 Milos Forman / Monte Hellman / Louis Malle / Nagisa Oshima / Carlos Saura / Andrei Tarkovsky / François Truffaut 1933 John Boorman / Stan Brakhage / Roman Polanski / Bob Rafelson / Jean-Marie Straub 1934 Sydney Pollack 1935 Woody Allen / Theo Angelopoulos 1936 Hollis Frampton / Danièle Huillet / Ken Loach 1937 Ridley Scott 1938 Paul Verhoeven 1939 Peter Bogdanovich / Francis Ford Coppola / William Friedkin / Glauber Rocha 1940 Dario Argento / Brian De Palma / Victor Erice / Terry Gilliam / Abbas Kiarostami / George A. Romero 1941 Bernardo Bertolucci / Stephen Frears / Patricio Guzmán / Krzysztof Kieslowski / Hayao Miyazaki / Raúl Ruiz / Bertrand Tavernier 1942 Peter Greenaway / Michael Haneke / Werner Herzog / Walter Hill / Martin Scorsese 1943 Roy Andersson / David Cronenberg / Mike Leigh / Terrence Malick / Michael Mann / Alan Rudolph 1944 Charles Burnett / Jonathan Demme / George Lucas / Peter Weir 1945 Terence Davies / Rainer Werner Fassbinder / George Miller / Wim Wenders 1946 Joe Dante / Claire Denis / David Lynch / Paul Schrader / Oliver Stone / John Woo 1947 Hou Hsiao-hsien / Takeshi Kitano / Rob Reiner / Steven Spielberg / Edward Yang 1948 John Carpenter / Philippe Garrel / Errol Morris 1949 Pedro Almodóvar 1950 Chantal Akerman / John Landis / John Sayles 1951 Kathryn Bigelow / Jean-Pierre Dardenne / Abel Ferrara / Aleksandr Sokurov / Robert Zemeckis / Zhang Yimou 1952 Jacques Audiard / Gus Van Sant 1953 Jim Jarmusch 1954 James Cameron / Jane Campion / Joel Coen / Luc Dardenne / Ang Lee / Michael Moore 1955 Olivier Assayas / Béla Tarr / Johnnie To 1956 Danny Boyle / Guy Maddin / Lars von Trier / Wong Kar-wai 1957 Ethan Coen / Aki Kaurismäki / Spike Lee / Mohsen Makhmalbaf / Tsai Ming-liang 1958 Tim Burton 1959 Nuri Bilge Ceylan / Pedro Costa / Sam Raimi 1960 Leos Carax / Atom Egoyan / Hong Sang-soo / Richard Linklater / Takashi Miike / Jafar Panahi 1961 Alfonso Cuarón / Todd Haynes / Peter Jackson / Alexander Payne / Abderrahmane Sissako / Michael Winterbottom 1962 David Fincher / Hirokazu Koreeda / Kenneth Lonergan 1963 Michel Gondry / Alejandro González Iñárritu / Park Chan-wook / Steven Soderbergh / Quentin Tarantino 1964 Guillermo del Toro / Kelly Reichardt / Andrey Zvyagintsev 1965 Jonathan Glazer 1966 Lucrecia Martel 1967 Denis Villeneuve 1969 Wes Anderson / Darren Aronofsky / Noah Baumbach / Bong Joon-ho / James Gray / Spike Jonze / Steve McQueen / Lynne Ramsay 1970 Paul Thomas Anderson / Jia Zhangke / Christopher Nolan / Apichatpong Weerasethakul 1971 Sofia Coppola / Carlos Reygadas Directors listed by key production country (Country of birth, if it differs, is listed in brackets) Argentina Lucrecia Martel Australia Jane Campion (New Zealand) / George Miller Austria Michael Haneke (Germany) Belgium Chantal Akerman / Jean-Pierre Dardenne & Luc Dardenne Brazil Glauber Rocha Canada David Cronenberg / Atom Egoyan (Egypt) / Guy Maddin / Denis Villeneuve China Jia Zhangke / Zhang Yimou Denmark Carl Theodor Dreyer / Lars von Trier Finland Aki Kaurismäki France Olivier Assayas / Jacques Audiard / Jacques Becker / Robert Bresson / Leos Carax / Marcel Carné / Claude Chabrol / René Clair / Henri-Georges Clouzot / Jean Cocteau / Jacques Demy / Claire Denis / Julien Duvivier / Abel Gance / Philippe Garrel / Jean-Luc Godard / Sacha Guitry (Russia) / Patricio Guzmán (Chile) / Claude Lanzmann / Louis Malle / Chris Marker / Georges Méliès / Jean-Pierre Melville / Max Ophüls (Germany) / Maurice Pialat / Roman Polanski / Jean Renoir / Alain Resnais / Jacques Rivette / Eric Rohmer / Raúl Ruiz (Chile) / Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet / Jacques Tati / Bertrand Tavernier / François Truffaut / Agnès Varda (Belgium) / Jean Vigo Germany / West Germany Rainer Werner Fassbinder / Werner Herzog / F.W. Murnau / G.W. Pabst (Austria-Hungary) / Wim Wenders Greece Theo Angelopoulos Hong Kong Wong Kar-wai (China) / Johnnie To / John Woo (China) Hungary Miklós Jancsó / Béla Tarr India Satyajit Ray Iran Abbas Kiarostami / Mohsen Makhmalbaf / Jafar Panahi Italy Michelangelo Antonioni / Dario Argento / Mario Bava / Bernardo Bertolucci / Vittorio De Sica / Federico Fellini / Sergio Leone / Ermanno Olmi / Pier Paolo Pasolini / Roberto Rossellini / Luchino Visconti Japan Kinji Fukasaku / Shohei Imamura / Takeshi Kitano / Hirokazu Koreeda / Akira Kurosawa / Takashi Miike / Hayao Miyazaki / Kenji Mizoguchi / Mikio Naruse / Nagisa Oshima / Yasujiro Ozu / Seijun Suzuki Mauritania Abderrahmane Sissako Mexico Luis Buñuel (Spain) / Alejandro Jodorowsky (Chile) / Carlos Reygadas New Zealand Peter Jackson Poland Krzysztof Kieslowski / Andrzej Wajda Portugal Pedro Costa / Manoel de Oliveira Russia / USSR Sergei Eisenstein (Latvia) / Aleksandr Sokurov / Andrei Tarkovsky / Dziga Vertov (Poland) / Andrey Zvyagintsev Senegal Ousmane Sembene South Korea Bong Joon-ho / Hong Sang-soo / Park Chan-wook Spain Pedro Almodóvar / Victor Erice / Luis García Berlanga / Carlos Saura Sweden Roy Andersson / Ingmar Bergman / Victor Sjöström Taiwan Hou Hsiao-hsien (China) / Tsai Ming-liang (Malaysia) / Edward Yang (China) Thailand Apichatpong Weerasethakul Turkey Nuri Bilge Ceylan UK John Boorman / Danny Boyle / Terence Davies / Terence Fisher / Stephen Frears / Jonathan Glazer / Peter Greenaway / David Lean / Mike Leigh / Ken Loach / Joseph Losey (USA) / Alexander Mackendrick (USA) / Steve McQueen / Michael Powell / Michael Powell (UK) & Emeric Pressburger (Hungary) / Lynne Ramsay / Carol Reed / Nicolas Roeg / Ken Russell / Michael Winterbottom USA (A-B) Robert Aldrich / Woody Allen / Robert Altman / Paul Thomas Anderson / Wes Anderson / Kenneth Anger / Darren Aronofsky / Hal Ashby / Tex Avery / Noah Baumbach / Kathryn Bigelow / Budd Boetticher / Peter Bogdanovich / Frank Borzage / Stan Brakhage / Clarence Brown / Tod Browning / Charles Burnett / Tim Burton USA (C-D) James Cameron (Canada) / Frank Capra (Italy) / John Carpenter / John Cassavetes / William Castle / Charles Chaplin (UK) / Joel Coen & Ethan Coen / Francis Ford Coppola / Sofia Coppola / Roger Corman / John Cromwell / Alfonso Cuarón (Mexico) / George Cukor / Michael Curtiz (Hungary) / Joe Dante / Jules Dassin / Delmer Daves / Brian De Palma / André de Toth (Hungary) / Guillermo del Toro (Mexico) / Cecil B. DeMille / Jonathan Demme / Maya Deren (Ukraine) / William Dieterle (Germany) / Edward Dmytryk (Canada) / Stanley Donen / Stanley Donen & Gene Kelly / Allan Dwan (Canada) USA (E-G) Clint Eastwood / Blake Edwards / Abel Ferrara / David Fincher / Robert Flaherty / Richard Fleischer / Victor Fleming / John Ford / Milos Forman (Czechoslovakia) / Hollis Frampton / John Frankenheimer / William Friedkin / Samuel Fuller / Terry Gilliam / Michel Gondry (France) / Alejandro González Iñárritu (Mexico) / D.W. Griffith / James Gray USA (H-L) Henry Hathaway / Howard Hawks / Todd Haynes / Monte Hellman / Walter Hill / Alfred Hitchcock (UK) / John Huston / Jim Jarmusch / Spike Jonze / Phil Karlson / Elia Kazan (Turkey) / Buster Keaton / Henry King / Stanley Kubrick / John Landis / Fritz Lang (Austria) / Ang Lee (Taiwan) / Spike Lee / Mitchell Leisen / Mervyn LeRoy / Jerry Lewis / Joseph H. Lewis / Richard Linklater / Kenneth Lonergan / Ernst Lubitsch (Germany) / George Lucas / Sidney Lumet / David Lynch USA (M-R) Terrence Malick / Joseph L. Mankiewicz / Anthony Mann / Michael Mann / Leo McCarey / Jonas Mekas (Lithuania) / Vincente Minnelli / Michael Moore / Errol Morris / Mike Nichols (Germany) / Christopher Nolan (UK) / Alexander Payne / Sam Peckinpah / Arthur Penn / Sydney Pollack / Otto Preminger (Austria-Hungary) / Sam Raimi / Bob Rafelson / Nicholas Ray / Kelly Reichardt / Rob Reiner / Mark Robson (Canada) / George A. Romero / Alan Rudolph USA (S-U) John Sayles / Paul Schrader / Martin Scorsese / Ridley Scott (UK) / George Sidney / Don Siegel / Robert Siodmak (Germany) / Douglas Sirk (Germany) / Steven Soderbergh / Steven Spielberg / George Stevens / Oliver Stone / John Sturges / Preston Sturges / Quentin Tarantino / Frank Tashlin / Jacques Tourneur (France) / Edgar G. Ulmer (Austria-Hungary) USA (V-Z) Gus Van Sant / Paul Verhoeven (Netherlands) / King Vidor / Josef von Sternberg (Austria) / Erich von Stroheim (Austria) / Raoul Walsh / Andy Warhol / Peter Weir (Australia) / Orson Welles / William Wellman / James Whale (UK) / Billy Wilder (Austria-Hungary) / Robert Wise / Frederick Wiseman / William Wyler (Germany) / Robert Zemeckis / Fred Zinnemann (Austria-HungaryJonas Mekas)

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

FOMA 23: German Post-War Modern

As a result of the devastating destructions of the Second World War architects in postwar Germany were faced not only with the rebuilding of cities but also with the opportunity to break with the past and follow new paths.

Children in bombed out Berlin in 1945. | Photo Otto Donath via Berliner Ferlag

The following five buildings represent Forgotten Masterpieces of German postwar architecture that deserve a closer examination.

The theater captured shortly after its completion in 1966 by Sigrid Neubert. | Photo via Baunetz

The first building is the Municipal Theater in Ingolstadt by Hardt-Waltherr Hämer and his wife Marie-Brigitte Hämer. Hämer is best known for his Berlin works, where he eloquently proposed a cautious renewal of the city and its quarters.

Interior view of the theater around 2009. | Photo via Breitschaft Architekten

The theater, designed and built between 1960 and 1966, is undoubtedly a prime example of German Brutalism that takes a bold modern stand within the city center of Ingolstadt: with its board-marked concrete surfaces and complex, interlocking interiors makes for interesting spatial experiences that are faintly reminiscent of Hans Scharoun‘s Berlin Philharmony.

View of the church from Northwest. | Photo by © Florian Monheim

As the followers of my Tumblr might have recognized I have a major knack for postwar church architecture in Germany and beyond. One of the most interesting examples of postwar modern church architecture in Germany is St. Paulus in Neuss in the lower Rhine region, a congenial collaboration between architects Fritz and Christian Schaller and engineer Stefan Poloyni.

View from East into the nave. | Photo by © Florian Monheim

On a hexagonal plan they created an awe-awaking space that is crowned by a spherical, folded and diamond-shaped vault. The church quintessentially represents the inventiveness of architects faced with the task of designing contemporary religious architecture: a spectacular, technologically innovative space that relies on the interplay of light and shadow to create a contemplative yet solemn atmosphere.

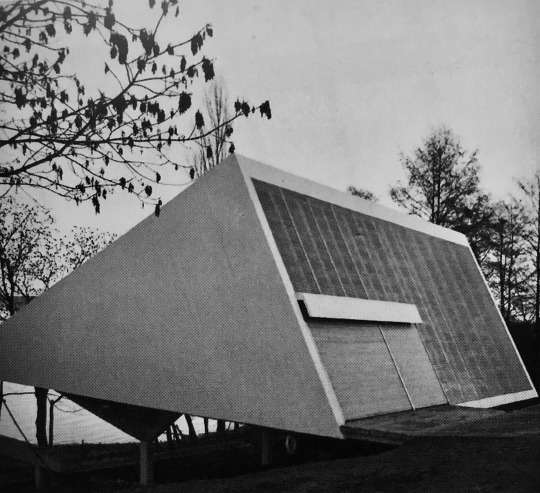

Moroshito after completion in 1961. | Photo via SAII

The summer house Moroshito, which Paul Stohrer designed for himself at Lake Constance, is a very unusual example of German postwar modernism and as such a favorite of mine. In its wedge-shaped design Stohrer processed influences from Oscar Niemeyer, a reference rarely present in German postwar architecture, and also gave expression to his colorful personality, which not only included a life-long passion for painting, but also for flamboyant sports cars.

The house's little bridge leading to the waters of Lake Constance. | Photo via Ruppenstein

Free from a client’s restriction Stohrer realized a house that was tailor made to his needs and gave him the freedom to play with shapes, materials and plans.

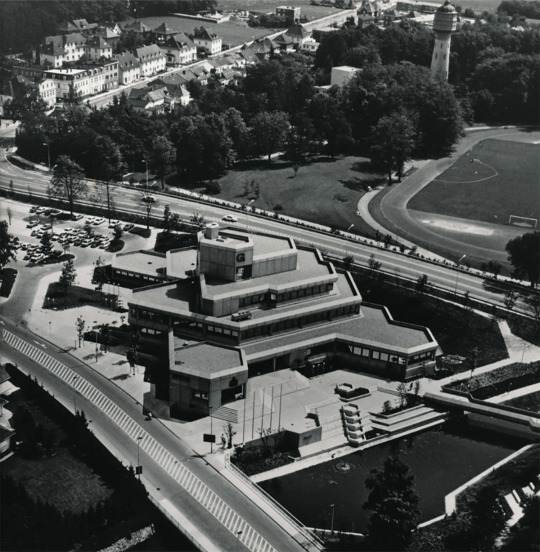

Aerial view of the town hall in 1975. | Photo via Baunetz

Harald Deilmann’s design for the Town Hall Gronau, a city on the German-Dutch border, represents a multi-functional approach to town halls in Germany in the 1960s and 1970s.

The town hall in 2016. | Photo by © Christian Richters

The scaled design houses a multitude of rooms, office, meeting places and with its raw concrete facade gives expression to the increased artistic freedom architects sought in these years. The building ranks among the most interesting yet overlooked examples of brutalism town hall architecture in Germany after WWII.

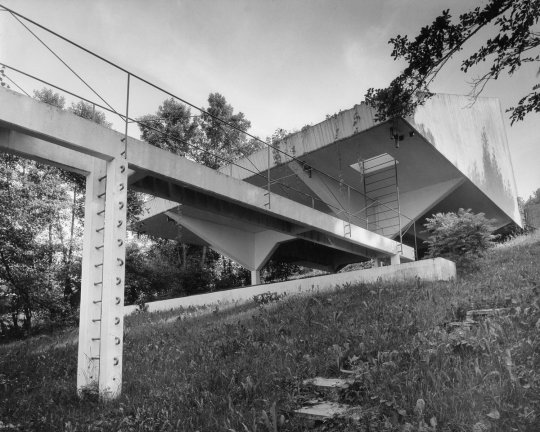

The Stadthalle in c. 1964. | Photo via Wesser Kurier

Last example of the architectural self-confidence of cities in postwar Germany is the Stadthalle in Bremen by Roland Rainer, built between 1961 and 1964. Rainer’s idea was to form a structural unity of a roof and stands, an idea that resulted in a suspension roof spanning more than 100 meters.

The Stadthalle was in 2000 renamed to AWD Arena. | Photo via Ortsamtwest

Due to the resulting expressive construction the Stadthalle soon became one of the city’s landmarks and together with the Stadthalle in Vienna and the one in Ludwigshafen forms a trilogy of Rainer’s successful civil engineering works.

--

#FOMA 23: Phillip Ost

Phillip Ost studies art history at Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, a middle-sized town in the Northwest of Germany. He focuses on postwar art and architecture in Germany and beyond with a special emphasis on postwar church architecture and German Art Informel. In 2014 he established German Post-War Modern, initially intended to serve as his personal visual archive of largely forgotten modernist architecture in Germany.

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

Unknown Page

Unknown Page Number Apa

Unknown Page

UnknownDirected byJaume Collet-SerraProduced by

Andrew Rona

Written byBased onOut of My Head by Didier Van CauwelaertStarringMusic byCinematographyFlavio LabianoEdited byTimothy Alverson

Production company

Distributed by

Warner Bros. Pictures[1] (International)

Kinowelt Filmverleih (Germany)[2]

Optimum Releasing (United Kingdom)[2]

StudioCanal (France)[2]

February 16, 2011 (Westwood)

February 18, 2011 (United States)

March 2, 2011 (France)

March 3, 2011 (Germany)

March 4, 2011 (United Kingdom)

113 minutesCountry

United States[3]

Germany[3]

United Kingdom[3]

France[3]

LanguageEnglish[1]Budget$30[2]–40[4] millionBox office$136.1 million[5]

Unknown is a 2011 action-thriller film directed by Jaume Collet-Serra and starring Liam Neeson, Diane Kruger, January Jones, Aidan Quinn, Bruno Ganz, and Frank Langella.[6] The film, produced by Joel Silver, Leonard Goldberg and Andrew Rona, is based on the 2003 French novel by Didier Van Cauwelaert published in English as Out of My Head which was adapted as the film's screenplay by Oliver Butcher and Stephen Cornwell.[7] The narrative centers around a professor who wakes up from a four-day long coma and sets out to prove his identity after no one recognizes him, including his own wife, and another man claims to be him.

This is an unknown page. Please call 1-800-442-3453 for assistance. Access study documents, get answers to your study questions, and connect with real tutors for UNKNOWN 121212: Writing (Page 2) at Alabama State University.

Released in the United States on February 18, 2011, the film received mixed reviews from critics and grossed $136 million against its $30 million budget.

Plot[edit]

Dr. Martin Harris (Liam Neeson) and his wife Liz (January Jones) arrive in Berlin for a biotechnology summit. At their hotel, Harris realizes he left his briefcase at the airport and takes a taxi to retrieve it. The taxi is involved in an accident and crashes into the Spree, knocking him unconscious. The driver rescues him but flees the scene. Harris regains consciousness at a hospital after being in a coma for four days.

When Harris returns to the hotel, he discovers Liz with another man (Aiden Quinn). Liz says this man is her husband and declares she does not know Harris. The police are called, and Harris attempts to prove his identity by calling a colleague named Rodney Cole, to no avail. He writes down his schedule for the next day from memory. When he visits the office of Professor Leo Bressler, whom he is scheduled to meet, 'Dr. Harris' is already there. As Harris attempts to prove his identity, 'Harris' provides identification and a family photo, both of which have his face. Overwhelmed by the identity crisis, Harris loses consciousness and awakens back at the hospital. A Terrorist named Smith kills his attending nurse, but Harris escapes.

Harris seeks help from private investigator and former Stasi agent Ernst Jürgen. Harris's only clues are his father's book on botany and Gina (Diane Krueger), the taxi driver, an undocumented Bosnian immigrant who has been working at a diner since the crash. While Harris persuades her to help him, Jürgen researches Harris and the biotechnology summit, discovering it is to be attended by Prince Shada of Saudi Arabia. The prince is funding a secret project headed by Bressler, and has survived numerous assassination attempts. Jürgen suspects that the identity theft might be related.

Harris and Gina are attacked in her apartment by Smith and another terrorist, Jones; they escape after Gina kills Smith. Harris finds that Liz has written a series of numbers in his book, numbers that correspond to words found on specific pages. Using his schedule, Harris confronts Liz alone; she tells him that he left his briefcase at the airport. Meanwhile, Jürgen receives Cole at his office and reveals his findings about a secret terrorist group known as Section 15. Jürgen soon deduces that Cole is a former mercenary and member of the group. Knowing Cole is there to interrogate and kill him and with no way of escape, Jürgen commits suicide to protect Harris.

After retrieving his briefcase, Harris parts ways with Gina. When she sees him kidnapped by Cole and Jones, she steals a taxi and follows them. When Harris awakes, Cole explains that 'Martin Harris' is just a cover name created by Harris. His head injury caused him to believe the cover persona was real; when Liz notified Cole of the injury, 'Harris' was activated as his replacement. Gina runs over Jones before he can kill Harris, then rams Cole's van, killing him as well. After Harris finds a hidden compartment in his briefcase containing two Canadian passports, he remembers that he and Liz were in Berlin three months earlier to plant a bomb in Prince Shada's suite.

Now aware of his own role in the assassination plot, Harris seeks to redeem himself by thwarting it. Hotel security immediately arrests Harris and Gina, but Harris proves his earlier visit to the hotel. After security is convinced of the bomb's presence, they evacuate the hotel.

Harris realizes that Section 15's target is not Prince Shada, but Bressler, who has developed a genetically modified breed of corn capable of surviving harsh climates. Liz accesses Bressler's laptop and steals the data. With Bressler's death and the theft of his research, billions of dollars would fall into the wrong hands. Seeing that the assassination attempt has been foiled, Liz tries to disarm the bomb but fails and is killed when it explodes. Harris kills 'Harris', the last remaining Section 15 terrorist, before he can murder Bressler. While Bressler announces that he is giving his project to the world for free, Harris and Gina—with new identities—board a train together.

Cast[edit]

Liam Neeson as Dr. Martin Harris

Diane Kruger as Gina

January Jones as Elizabeth 'Liz' Harris

Aidan Quinn as imposter Martin

Frank Langella as Professor Rodney Cole

Bruno Ganz as Ernst Jürgen, a former Stasi operative

Sebastian Koch as Professor Bressler

Stipe Erceg as Jones

Olivier Schneider as Smith

Rainer Bock as Herr Strauss (chief of hotel security)

Mido Hamada as Prince Shada

Karl Markovics as Dr. Farge

Eva Löbau as Nurse Gretchen Erfurt

Clint Dyer as Biko

Many German actors were cast for the film. Bock had previously starred in Inglourious Basterds (which also starred Diane Kruger) and The White Ribbon. Other cast includes Adnan Maral as a Turkish taxi driver and Petra Schmidt-Schaller as an immigration officer. Kruger herself is also German, despite playing a non-German character.

Production[edit]

Friedrichstraße, Berlin, is the scene of a car chase

Oberbaumbrücke, from which the taxi plunges into the river

Principal photography took place in early February 2010 in Berlin, Germany, and in the Studio Babelsberg film studios.[6] The bridge the taxi plunges from is the Oberbaumbrücke. The Friedrichstraße was blocked for several nights for the shooting of a car chase. Some of the shooting was done in the Hotel Adlon. Locations include the Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin Hauptbahnhof, Berlin Friedrichstraße station, Pariser Platz, Museum Island, the Oranienburger Straße in Berlin and the Leipzig/Halle Airport.[8] According to Andrew Rona, the budget was $40 million.[9] Producer Joel Silver's US company Dark Castle Entertainment contributed $30 million.[10] German public film funds supported the production with €4.65 million (more than $6 million).[11] The working title was Unknown White Male.

Release[edit]

Unknown was screened out of competition at the 61st Berlin International Film Festival.[12] It was released in the United States on February 18, 2011.

Critical response[edit]

On Rotten Tomatoes, a review aggregator, the film has an approval rating of 55% based on 200 reviews; the average rating is 5.81/10. The site's critical consensus reads, 'Liam Neeson elevates the proceedings considerably, but Unknown is ultimately too derivative – and implausible – to take advantage of its intriguing premise.'[13] On Metacritic the film has an average weighted score of 56 out of 100, based on 38 critics, indicating 'mixed or average reviews'.[14] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of 'B+' on an A+ to F scale.[15]

Richard Roeper gave the film a B+ and wrote, 'At times, Unknown stretches plausibility to the near breaking point, but it's so well paced and the performances are so strong and most of the questions are ultimately answered. This is a very solid thriller.'[16] Justin Chang of Variety called it 'an emotionally and psychologically threadbare exercise'.[17]

Box office[edit]

Unknown grossed $63.7 million in North America and $72.4 million in other territories for a worldwide total of $136.1 million.

It finished a number one opening at its first week of release with $21.9 million.[18]

References[edit]

Unknown Page Number Apa

^ abcd'Unknown (2011)'. AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

^ abcdUnknown at Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

^ abcd'Unknown (EN) [Original title]'. LUMIERE. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

^40 million according to Andrew Rona at Berlinale press conference, Friday 18 February 2011. See 'Video Press Conference' at Berlinale web site after 30 minutes. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

^Unknown at The Numbers. Retrieved 2013-04-12.

^ ab'Unknown White Male Starts Principal Photography'. MovieWeb.com. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

^Dargis, Manohla (2011-02-17). 'Me, My Doppelgänger and a Dunk in the River'. The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

^'Unknown Shooting in Berlin'. EmanuelLevy.com. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

^Andrew Rona at Berlinale press conference, 18 February 2011. See 'Press Conference' video at Berlinale web site after 30 minutes. Retrieved 2012-01-23.

^Fritz, Ben; Kaufman, Amy (17 February 2011). 'Movie Projector: 'I Am Number Four' to be No. 1 at holiday weekend box office [Updated]'. Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

^'Unknown Identity'. MediaBiz.de. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

^'The 'Competition' of the 61st Berlinale'. Berlinale.de. 18 January 2011. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

^'Unknown (2011)'. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

^'Unknown reviews'. Metacritic. Retrieved 2 September 2011.

^'Unknown–CinemaScore'. cinemascore.com. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

^Roeper, Richard (2011). 'Richard Roeper's Reviews - Unknown Review'. YouTube. Reelz Channel. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

^'Unknown'. Variety. 15 February 2011.

^'Unknown' Helps French Cinema Have an Identity Abroad in 2011'. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2012-02-07.

External links[edit]

Unknown on IMDb

Unknown at AllMovie

Unknown at Box Office Mojo

Unknown at Rotten Tomatoes

Unknown at Metacritic

Unknown at The Numbers

Unknown Page

Retrieved from 'https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Unknown_(2011_film)&oldid=1000301041'

0 notes

Text

Luise Rainer, c. 1932 - photo portrait by Fritz Henle

1 note

·

View note