#rikyu-cha

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Vrtra sketch (sailor M nib with rikyu-cha)

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

L’histoire du Thé, aurait comme origine légendaire, une histoire datant de 2737 avant notre ère en Chine. Effectivement, alors que l’Empereur Shennong était en train de bouillir de l’eau à l’abri d’un arbre, une légère brise agita les branches et détacha quelques feuilles. Ses feuilles iront se mélanger à l’eau et lui donneront le parfum et la couleur qu’on reconnaît au thé. L’Empereur goûtera, appréciera et ira même en reprendre. Ainsi, l’arbre que l’Empereur avait choisi été un Théier Sauvage. Ainsi, le thé naquit selon cette légende. Une autre légende l’attribue à Bodhidharma, mais nul ne sera réellement de quand tient l’invention du thé. Toutefois, après cela, nous pouvons retravailler avec plus ou moins de certitudes. Le thé évoluera d’un usage royal et noble à un usage populaire sous la Dynastie des Tang de Chine (618 à 907) et il dépassera un cadre médical pour devenir l’élément de raffinement de la journée. Le premier traité sur le thé. “Le Cha Jing”, sera écrit par Lu Yu entre 760 et 780. Il y décrira de façon poétique la nature de la plante et il codifiera la préparation et la dégustation de la boisson.

Le thé à plusieurs façons d’être consommé. Sous forme de brique compressée, le thé est rôti avant d’être réduit en poudre et d’être mêlé à l’eau bouillante. On peut aussi y ajouter du sel, des épices ou bien même du beurre rance. Nous avons une autre façon de consommation qui naquît sous la dynastie des Song (960-1279), connue aujourd’hui comme le “Cha No Yu japonais” qui met l’accent sur le respect des règles de préparations et sur les bols. Pulvérisées à l’aide d’une meule pour obtenir une poudre très fine, les feuilles sont de plus en plus raffinées. Mélanger en mousse ensuite avec un fouet en bambou, sera l’essence même du raffinement du thé. En marge de cela, le thé en vrac se répand et une consommation des classes plus désavantagée se développera. La dynastie Ming (1368 à 1644), un décret impérial stoppera toutefois la fabrication des briques de thé pour une consommation qui sera celle actuelle : en infusion et dans un récipient, influençant ainsi les objets et accessoires utilisés pour sa préparation. Pour le Japon, ça ne sera qu’au XVe siècle que ce dernier se développera et pourra se répandre dans l’archipel japonais. Le thé deviendra une religion, un art et une philosophie qu’avec Sen No Rikyu (1522-1591) qui sera le premier grand-maître du thé.

Une terrasse de culture du Thé Longjing dans la province du Zhejiang. Sa préparation se fait par un séchage à la poêle au lieu du séchage classique du thé. Ses feuilles sont aussi roulées au lieu d'être pliées, faisant de ce dernier, un thé assez spécial et fortement falsifié. Il existe une grande variété de caractéristiques pour définir le Longjing. La définition commune pour l'authentique Longjing est le fait qu'il provient de la province chinoise du Zehejiang. Avec une définition plus stricte, il est restreint à une zone de différents villages du Lac de l'Ouest de Hangzhou. Il est aussi possible de le définir par du thé ayant poussé dans le district de Xihu. Une large majorité du thé Longjing présent sur le marché ne provient actuellement pas de Hanghzou, mais de différentes régions telles que le Yunnan, le Ghuizhou, le Sichuan et le Guangdong produisant un thé non-authentique. Thé vert, sorte de thé le plus consommé en Chine et au Japon, le Longjing est cultivé en terrasse.

Le thé vert est le thé le plus consommé en Chine, en Corée et au Japon. Il se répand aujourd'hui de plus en plus en Occident, où l'on boit traditionnellement plutôt du thé noir. Les différents terroirs, cultivars utilisés et modes de culture permettent d'obtenir des thés verts très différents. Si le Sencha est le thé quotidien des Japonais, lors de la cérémonie du thé japonaise, c'est du Matcha, une poudre de thé vert broyé, qui est utilisée.

Le Thé Longjing obtint le statut de thé pour la cérémonie du thé ou de thé impérial sous la dynastie Qing. Selon la légende, le statue aurait été donnée par l'Empereur Kangxi lorsque son petit-fils, le futur Empereur Qianlong aurait visité le lac de l'ouest lors d'une de ses célèbres visites. Lors d'une de ses visite, il se rendit au temple Hu Gong se situant sur la montagne du Pic du Lion (Shi Feng Shan) où se trouvaient 18 théiers et recevra en guise d'accueil une tasse de thé Longjing. Qianlong, tellement impressionné par le thé produit ici, décida de lui conférer le statut de Thé Impérial. Il existe une autre légende reliant l’empereur Qianlong au thé Longjing. On raconte qu'en visitant le temple, il regardait les dames cueillir le thé. Il était tellement séduit par leurs mouvements qu'il a décidé de les essayer lui-même. Alors qu'il cueillait du thé, il reçut un message l'informant que sa mère, l'impératrice douairière Chongqing, était malade et souhaitait son retour immédiat à Pékin. Il fourra les feuilles qu'il avait cueillies dans sa manche et partit immédiatement pour Pékin. À son retour, il alla immédiatement rendre visite à sa mère. Elle remarqua l'odeur des feuilles provenant de ses manches et les firent immédiatement préparer pour elle. On dit que la forme du thé Longjing a été conçue pour imiter l’apparence des feuilles aplaties que l’empereur préparait pour sa mère.

Le Masala Chai. "Chai" est le terme hindi du sous-continent indien pour désigner le thé. Le Masala Chai est la forme de thé la plus utilisée à cet endroit. Consistant à un thé noir très sucré mélangé avec du Masala (un mélange d'épices) dans du lait bouillant dans une casserole. Le Thé, n'étant qu'un besoin récréatif ou vu comme des plantes par les Indiens, poussé depuis l'antiquité dans la région de l'Assam. Il ne fut introduit comme une boisson populaire que par les Britanniques assez tard. En 1830, la British East India Company devant intéressé par le monopole du thé Chinois qui commercer et supporté l'énorme consommation de thé pour la Grande-Bretagne (environ 0.45 kg par an pour une personne.) Les colons Anglais ont appris l'existence des plantes de Thé de l'Assam récemment après cette préoccupation et ont ainsi décidé de cultiver localement cette plante. En 1870, 90 % du thé consommé en Grande-Bretagne était d'origine chinoise et en 1900, une chute vertigineuse du thé chinois fut reconnue et seulement 10 % du thé consommé été de cette origine. 50 % était d'origine indienne et 33 % provenait de Ceylan.

Sans recette fixe, le Masala Chai est généralement consommé avec un Thé Noir assez fort, telle que l’Assam pour que son goût ne soit pas altéré par le goût du sucre et des épices consommé traditionnellement avec. Souvent servi sucré, voire très sucré, il possède un fort goût épicé à cause de cela. La pratique commune des Marathi, un peuple de l'ouest de l'Inde pour la préparation du Masala Chaï, est de combiner la moitié d'une tasse d'eau avec une la moitié d'une tasse de lait dans un pot mis sur le feu. Le sucre est ajouté durant cette partie ou après. Le gingembre est graduellement mis dans la préparation suivie de la mise d'une préparation dite "Thé Masala". Les ingrédients variant d'une région à une autre le "Thé Masala" est typiquement consommé avec différentes épices propres à chaque région. Il est aussi trouvable sur les abords des routes, des voies rapides ou des allées, des vendeurs de petite taille nommés "Chaiwalla" en Hindi ou "Cha-Ola" en Bengali.

Mélange d’épice contenant une grande quantité différente d’épice, nous pouvons retrouver dans le Masala Chai : du Gingembre, de la Cannelle, de la Cardamome, de l’Anis Étoilé, du Fenouil, du Poivre, des Clous de Girofle ou de la Coriandre, de la Muscade ou du Cumin. On peut parfois même y trouver de l’écorce de Citron.

Nous pouvons aussi avoir du thé traité d’une telle façon qu’il se présente sous forme de granulés plutôt que d’une feuille. Cette sorte de thé est utilisée particulièrement dans le Cachemir, il est nommé Zhūchá (Perle de thé) en chinois ou en anglais “Gunpowder” à cause de sa forme. Ce thé est produit depuis la Dynastie Tang datant de 618 à 907.

Le Matcha, pouvant aussi être appelé Kocha ou Konacha est un Thé Vert moulu et broyé entre deux pierres. Il est connu pour son utilisation dans le Chanoyu, la Cérémonie du Thé Japonais. La région de Nisho est connue pour la qualité du Matcha nommé "Nishiocha". L'origine provient d'une tradition originaire de Chine sous la dynastie Sui (581–618) où il est alors appelé mocha. Cette tradition y arrive à son apogée sous les dynasties Tang (618–690 et 705–907) et Song (960-1279). La préparation et la consommation de ce thé devinrent un rituel sous l'influence de la pratique du bouddhisme Chan, dans lequel il était bu dans un bol commun en guise de sacrement.Les Ustensiles couramment utilisées dans la préparation et la consommation du matcha, le bol à thé (chawan), le petit fouet (chasen), et l'écope (chashaku). Le matcha doit être tamisé avant d'être mélangé à l'eau. On utilise à cette fin des tamis spéciaux, généralement en acier inoxydable, au maillage serré, et incluant un réceptacle provisoire. Pour faire passer le thé à travers le tamis, on peut utiliser une spatule de bois spéciale ou placer une pierre polie sur le tamis et le secouer doucement. Si le matcha doit être servi lors d'une cérémonie du thé, il doit être placé dans une petite boîte spéciale. Dans le cas contraire, on peut verser le contenu du tamis directement dans le bol à thé. Du fait de son goût légèrement amer, le matcha est traditionnellement servi accompagné d'une petite sucrerie, qu'on laisse fondre sur la langue avant de boire le thé, ou dont on croque un bout avant chaque gorgée (la cérémonie prescrivant de boire son bol en trois fois). Au Japon, il est bu sans sucre, ni lait, ni ajout.

La production du matcha commence quelques semaines avant la récolte, lorsque les buissons de thé sont couverts pour les protéger de la lumière directe du soleil. Cela ralentit la croissance de la plante, rend ses feuilles plus sombres et entraîne la production d'acides aminés qui adoucissent le goût du thé, notamment l’acide aminé L-theanine responsable du goût umami du thé matcha. Après la récolte, si les feuilles sont enroulées avant le séchage, ce qui est le cas d'ordinaire, le thé résultant sera du gyokuro. Si à l'inverse les feuilles sont dépliées pour le séchage, elles vont quelque peu s'émietter et produire du tencha. Le tencha peut ensuite être moulu en une poudre très fine, d'un vert clair ; il sera alors appelé matcha. Seul le tencha en poudre peut être qualifié de matcha. Les autres variantes de thés moulus sont simplement appelées konacha. Le taux élevé de catéchine (un flavonoïde) qu'il contient est une conséquence de la taille très fine de la poudre du matcha. La saveur du matcha est affectée par ses acides aminés. Les meilleurs matcha ont généralement un arôme plus profond et plus doux que les thés récoltés plus tardivement. Le matcha est maintenant un ingrédient courant dans les sucreries japonaises. Il est utilisé dans le kasutera, les manjū et le monaka, les mochi, comme garniture pour le kakigōri, comme boisson mélangé avec du lait et du sucre, ou en matcha-shio (une préparation qui peut accompagner le tempura). Il est aussi utilisé comme un arôme pour parfumer des chocolats, des bonbons, des gâteaux (cookies, puddings…) ou des crèmes glacées. L'utilisation du matcha dans des boissons modernes s'est répandue dans les cafés aux États-Unis où, comme au Japon, il peut être mélangé au café au lait, au milkshake, dans des boissons glacées, et dans des boissons sucrées ou alcoolisées. Le thé matcha connaît également un grand succès dans les bubble teas, boisson aux perles d'origine taïwanaise. Les vertus alimentaires du thé vert en général et du matcha en particulier ont suscité un vif intérêt aux États-Unis. On peut maintenant trouver du matcha dans de nombreux aliments diététiques allant des mélanges à base de céréales aux barres énergétiques.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

Nice to meet you Rikyu! We heard about your tea shop from Koma, but didnt know it doubled as a general store...do you plan on reopening it after the bout? We'd love to visit!

"Truly? I would very much appreciate your patronage. It serves as both a teahouse and a general shop to sell various wares. Our products are simple, but quite effective. The tea as well. That is the way of Wabi-cha."

"In fact, and please do not think me presumptuous, but I would be rather pleased if I had the honor of enacting such a ceremony with you. It would be 'on the house', as they say."

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wabi Sabi là gì? Vẻ đẹp không hoàn hảo phong cách Wabi Sabi

Wabi Sabi - vẻ đẹp của sự không hoàn hảo, tôn vinh cái cũ và vô thường, là triết lý sống thanh đạm của Nhật. Vậy bạn hiểu phong cách Wabi Sabi là gì? Nguồn gốc? Đặc trưng của Wabi Sabi? Trong bài viết này hãy cùng với chúng tôi tìm hiểu chi tiết về phong cách này nhé!

Phong cách Wabi Sabi là gì?

Khái niệm về Wabi Sabi khởi nguồn từ phương pháp Thiền của đạo Phật ở thế kỷ thứ XII. Sau đó nó đã được phát triển mạnh mẽ qua nghi thức trà đạo cải tiến của thiền sư Sen no Rikyu. Wabi Sabi đã dần tiến đến vị trí độc tôn trong quan niệm của xứ sở “mặt trời mọc”

Wabi Sabi trong thiết kế nội thất Wabi Sabi trong tiếng Nhật căn bản được hiểu đó là “tìm kiếm nét đẹp chưa hoàn thiện”. Wabi Sabi được phối hợp từ 2 từ riêng biệt là “Wabi” và “Sabi”, cụ thể như sau: “Wabi” có nghĩa là nhận ra sự đủ đầy trong tâm hồn thông qua những nhu cầu sống đơn sơ và khiêm tốn về vật chất. Nó cũng giống như bạn tận hưởng điều tuyệt vời nhờ sự tĩnh lặng từ thiên nhiên, tìm về cốt lõi của cuộc sống hạnh phúc. “Sabi” chính là vẻ đẹp được mài giũa thông qua đôi bàn tay của không gian và thời gian. Các chi tiết của đồ vật, nội thất dường như là được khoác lên mình chiếc áo bụi bặm, sạm màu nhưng đủ độ chín muồi. Để rồi những sứt mẻ ấy nổi bật lên nét quyến rũ và hoài cổ mà ai trong chúng ta cũng muốn được một lần nghiền ngẫm. Trong cuộc sống hiện đại thì phong cách Wabi Sabi hiện diện rất phổ biến trong các kiến trúc và thiết kế kết hợp cùng với các phong cách khác nhau như: Bắc Âu, đồng quê hay tối giản…

Nguồn gốc của Wabi Sabi là gì?

Phong cách Wabi Sabi được bắt nguồn từ câu chuyện về Sen no Rikyu. Đây là một thiền sư vào thế kỷ XVI, ngài đã khái quát học thuyết trà đạo mà cho đến nay người Nhật vẫn thực hành nó mỗi ngày. Theo như truyền thuyết thì chàng thanh niên Sen no Rikyu rất háo hức muốn học bí quyết của nghệ thuật trà đạo. Chàng đã tìm đến một bậc thầy về trà có tên Takeeno Joo. Thầy Takeeno Joo vì muốn kiểm tra khả năng của người học trò mới nên đã yêu cầu anh phải chăm sóc khu vườn. Rikyu đã dọn vườn từ trước ra sau và quét sạch cho đến khi không còn một cọng rác nào. Tuy nhiên, trước khi thầy nhìn thấy được sự nỗ lực của chàng thì Rikyu đã rung lắc một cây anh đào làm cho hoa Sakura rơi rụng đầy đất. Chính một chút không hoàn hảo này đã đem lại vẻ đẹp hoàn hảo cho quang cảnh. Đây cũng là lịch sử ra đời của khái niệm Wabi Sabi.

Bậc thầy trà đạo Sen no Rikyu Sen no Rikyu được xem như là một trong những bậc thầy trà đạo Nhật Bản. Ông đã chuyển đổi nghi lễ trà đạo với những dụng cụ xa xỉ và hoa mỹ để thành một thói quen hàng ngày của người dân. Bằng việc sử dụng những dụng cụ không hoàn hảo, đôi khi là bị nứt hoặc được sửa lại, trong một căn phòng tối giản mà Rikyu đã biến việc thưởng trà trở thành khoảnh khắc chạm tới linh hồn. Quan điểm của ông đó là: hòa hợp, tinh khiết, thành kính và bình dị. Hình thức thưởng trà thanh đạm này còn được gọi với cái tên là Wabi-cha. Ở đây “cha” trong tiếng Nhật có nghĩa là “trà”. Ngày nay thì người Nhật vẫn thưởng trà đạo với những bộ ấm tách cũ kỹ hàng trăm năm tuổi. Trong nghề làm gốm ở Nhật Bản thì những chiếc tách thường được nặn với những hình dáng móp méo, bất nhất bởi vì mỗi vật thể cần phải có được những hình dáng độc nhất thì mới bộc lộ rõ được hết vẻ đẹp duy biệt của nó. Có thể nói, vẻ đẹp khiếm khuyết của Wabi Sabi được tìm thấy ở bất kì loại hình nghệ thuật nào tại Nhật.

Đặc trưng của Wabi Sabi là gì?

Trong quan điểm thẩm mỹ của con người ở xứ sở Phù Tang thì phong cách Wabi Sabi chiếm vị trí độc tôn. Nó được áp dụng cho nhiều lĩnh vực, bao gồm cả kiến trúc và thiết kế nội thất. Phong cách Wabi Sabi không hướng đến sự xa hoa, lộng lẫy mà thay vào đó chính là nét thô sơ, hoài cổ. Những nét đặc trưng, nổi bật trong phong cách này đã giúp cho con người tìm thấy được niềm vui và hạnh phúc thực sự. Sự đơn giản Phong cách Wabi Sabi luôn giữ được sự đơn giản, không quá cầu kỳ trong kiểu cách thiết kế nhờ vào việc sử dụng các vật liệu hữu cơ. Đó cũng chính là lý do vì sao mà phong cách này luôn hiện lên được sự chân thực và mộc mạc hơn là sự buồn tẻ và đơn điệu.

Wabi Sabi luôn hướng đến sự tối giản Nhờ vào lối thiết kế tối giản mà sự tự nhiên và những cảm giác ấm áp của không gian cũng được tạo thành. Ngoài ra thì không gian cũng trở nên thông thoáng, độ ẩm được điều chỉnh rất tự nhiên, không thải độc tố. Sự tiết chế Sự tiết chế cũng là một trong những nguyên tắc cơ bản nhất của phong cách Wabi Sabi. Trong một số trường hợp thì những nguyên tắc này cũng được thể hiện thông qua những gì bị lược bỏ hoặc lãng quên trong tác phẩm. Sự điều tiết sẽ mang đến cho người dùng cảm giác chân thực cũng như trải nghiệm sự vô thường của không gian. Vật liệu Thiết kế nội thất theo phong cách Wabi Sabi có những đặc điểm riêng, ví dụ như sử dụng các vật liệu hữu cơ, gần gũi với thiên nhiên.

Wabi Sabi sử dụng vật liệu gần gũi với thiên nhiên Phong cách này đã được loại bỏ các giai đoạn trang trí với mục đích là để truyền tải thông điệp về quá trình tiến hóa của mọi vật cũng như lịch sử hình thành xã hội loài người theo thời gian. Kết cấu Thông thường thì những món đồ nội thất được thiết kế theo phong cách này sẽ có bề mặt khá xù xì và thô ráp… Tuy nhiên, chúng vẫn giữ được vẻ tự nhiên, không đồng đều. Chính bởi những đặc trưng này mà đã tạo thành những tiêu chí độc đáo của phong cách Wabi Sabi. Kiểu dáng Phong cách Wabi Sabi có kiểu dáng chú trọng đến vẻ đẹp ban đầu. Mặc dù có cải biên nhưng nó lại chú ý đến vẻ đẹp tự nhiên, không làm mất đi tính chất hay tính nguyên bản. Đây cũng chính là điểm nổi bật và cũng là điều mà người Nhật luôn muốn theo đuổi.

Wabi Sabi chú trọng vẻ đẹp ban đầu Sự sang trọng của những kiểu thiết kế này hoàn toàn không có liên quan đến sự công nghiệp hóa mà hướng đến sự tự nhiên và bền vững. Trong cuộc sống hiện đại thì đây không phải là một điều dễ dàng có thể giữ được. Màu sắc Màu sắc theo phong cách này cũng thường hướng đến sự chân thực với các đường nét tự nhiên. Bên cạnh sự thống nhất thì màu sắc cũng chứa đựng sự tương phản để làm nổi bật lên không gian. Những gam màu được sử dụng luôn mang đến sự tĩnh lặng, yên bình trong tâm hồn. Không gian Khi thiết kế theo phong cách Wabi Sabi thì điều đầu tiên bạn cần chú ý đó là tỷ lệ và phối cảnh. Đặc trưng của phong cách này chính là không cho phép những khoảng trống vô nghĩa. Nói cách khác, ngay cả những khoảng trống thì cũng có ý nghĩa riêng của chúng.

Wabi Sabi không cho phép các khoảng trống vô nghĩa Tỷ lệ thiết kế của từng món đồ nội thất cũng phải được đo lường cẩn thận để không lộ ra những khoảng trống về độ rộng, chiều cao hay độ mở. Phong cách thiết kế này mang đến sự yên bình và thanh thản cho tâm hồn. Vì vậy mà không gian mở đóng một vai trò rất quan trọng, giúp kết nối các nguồn sáng để tạo ra một điểm nhìn. Có thể bạn quan tâm: Vintage là gì? Đặc điểm phong cách vintage trong thời trang, nhiếp ảnh Phong cách retro là gì? Các đặc trưng của phong cách retro Thực tế thì Wabi Sabi đã ăn sâu, bén rễ vào trong văn hóa của người Nhật. Và bạn có thể nhìn thấy phong cách Wabi Sabi ở khắp mọi nơi. Read the full article

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (84): Nambō Sōkei’s Postscript to Book Seven.

○ The preceding volume [is dated] the Second Year of Bunroku [文祿] -- the ki-shi [癸巳] year -- Second Month, twenty-eighth day¹.

[For] the deceased teacher, Rikyū Sōeki dai-koji, on the third anniversary of the date of his death², incense, flowers, tea, and sweets [were offered] during the memorial service³.

After [I] finished chanting the sūtras, beneath the lamps [on the altar], [my] tears of yearning flowed freely⁴. Along with stories of the bygone age, with neither end nor beginning, I wrote [everything down] continuously⁵ -- [and lo,] already it has become an entire volume⁶.

And in that room where [I] had been writing, [I] intoned [this] gāthā, offering it [to Rikyū] below [his] mortuary tablet⁷.

A disciple of Rikyū dai-koji’s Pure Tea, Nambō Sōkei prostrates himself [before the altar]⁸:

“A solitary lamp, its oil exhausted, the flower is not quite white⁹;

“The single dǐng [鼎], its water dried, [my] tea is not green¹⁰.

“The master has left the thatched hut, the three stages of enlightenment [are] a dream¹¹;

“The East Wind announces the dawn, [and my] tears of emptiness fall [like raindrops]¹².”

_________________________

◎ This is Nambō Sōkei’s oku-gaki [奧書] to Book Seven of the Nampō Roku. While the gāthā may actually have been written by Sōkei, the rest of this entry is a melodramatic creation of the Edo period -- for even if Sōkei was so racked by sadness during what would be his final hours, it would have been unseemly for a monk of his eminence to leave such traces of his grief behind to sully his reputation. Nevertheless, this is how the Nampō Roku ends, leaving it to us to cherish and carry on Rikyū’s memory in perpetuum.

¹Migi kono ikkan ha Bunroku ni[-nen] ki-shi ni-gatsu nijū-hachi nichi [右此一巻ハ文祿二癸巳二月廿八日].

Migi kono ikkan [右この一巻] means the preceding volume -- that is, Book Seven.

Bunroku-ni [文祿二] means the second year of the Bunroku era. The second year of Bunroku ran from February 2, 1593, to February 19, 1594.

Bunroku was the era that followed the Tenshō [天正] era (during which most of the episodes that are documented in the Nampō Roku occurred).

Ki-shi [癸巳] is the 30th year in the sixty-year cycle.

[Bunroku ni-nen] ni-gatsu nijū-hachi nichi [二月廿八日] was March 31, 1594.

This date indicates that this oku-gaki [奧書] is a forgery, because Nambō Sōkei elsewhere recognized that Rikyū’s seppuku took place on the 28th day of the third month of the year (because Tenshō 19 had two first months) -- thus, the 28th day of the Second Month of Tenshō 19 was April 21, 1591; so the third anniversary would have had to be on the corresponding day, according to the Lunar Calendar, in 1593 -- April 30.

²Sen-ji Rikyū Sōeki dai-koji dai-san-kai ki-shin [先師利休宗易大居士第三囘忌辰].

Sen-ji [先師] means the deceased teacher.

Rikyū Sōeki dai-koji [利休宗易大居士]: the formula dai-koji [大居士] is primarily used after the person is deceased.

Dai-san-kai ki-shin [第三囘忌辰]*: means the third (anniversary of); ki-shin [忌辰] means the day of (someone’s) death.

Tanaka’s genpon text introduces a comma following Rikyu’s name and title (that is, following the word dai-koji [大居士]). Also, rather than dai-san-kai ki-shin [第三囘忌辰], the genpon has san-kai [no] hi [三回日], which means the third (memorial) day. ___________ *The toku-shu shahon and genpon change the nonstandard kanji kai [囘] to the more usual kai [回], writing this as dai-san-kai ki-shin [第三回忌辰].

Both kanji actually have the same meaning.

³Kō ka cha kashi wo kuyō-shi [香花茶菓ヲ供養シ].

Kuyō-suru [供養する] means to hold a memorial service for (Rikyū).

However, kō ka cha kashi wo kuyō-shi [香・花・茶・菓を供養し] would mean “incense, flowers, tea, and kashi were offered” (in other words, arranged on the altar in front of the image of the Buddha and Rikyū’s mortuary tablet).

The offering of kashi in particular, on occasions such as this, seems to be something that was done during the Edo period. In records from Rikyū’s period, kashi are never mentioned.

⁴Ju-kyō ekō-shi owarite, tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo shi-tate [誦經囘向シ畢テ、燈下懷旧ノ涙ヲシタテ].

Ju-kyō ekō-shi owarite [誦經回向し畢て]: ju-kyō [誦經] means chanting of the sūtra(s); ekō-suru [回向する] means to hold a memorial service for (Rikyū); owarite [畢わりて = 終りて]* means concluded, be through with.

Tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo shi-tate [燈下懷旧の涙を爲たて]: tō-ka [燈下] means beneath the lamp(s), in other words, in front of the altar; kaikyū no namida wo shitate [懷旧の涙を爲たて] means tears of yearning† flow freely.

In other words, when the chanting of the sūtra(s) during the memorial service for Rikyū were concluded, Sōkei sat in front of the altar with tears of yearning flowing.

The toku-shu shahon represents this sentence as u-kyō ekō-shi owarite, ta-nen no ya-wa bundan wo omoide, tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo otoshite [誦經回向シ畢リテ、多年ノ夜話聞談ヲ思ヒ出、燈下懷旧ノ涙ヲ落シテ].

There seems to be an error in this version of the text (perhaps a copyist’s mistake when Shibayama Fugen’s notes were being typeset for publication?), since the meaning of ya-wa bundan [夜話聞談] is unclear. The genpon text gives this as ya-wa kandan [夜話閑談], which means “informal chatting at night,” and this is probably the correct expression‡.

The genpon text has abbreviated this sentence by removing the first phrase: ta-nen no ya-wa kandan wo omoidete tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo otoshite [多年ノ夜話閑談ヲ思出テ燈下懷旧ノ涙ヲ落シテ].

Ta-nen no ya-wa kandan wo omoidete [多年の夜話閑談を思い出て] means “remembering many years of late-night chats**.”

And, tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo otoshite [燈下懷旧の涙を落して] means “beneath the (altar) lamps tears of yearning fall.”

So, “remembering many years of late-night chats, beneath the (altar) lamps my tears of yearning fall.” ___________ *This use of the kanji “畢” to mean owaru [畢わ�� = 終わる] was more or less unique to the Edo period.

†Kaikyū [懷旧] more literally means things like reminiscence, nostalgia. Yearning, in the sense of longing for something (or someone) that is in the past, that cannot be experienced again.

‡With respect to the toku-shu shahon version, assuming that ya-wa kiki-dan [夜話聞談] is a mistaken rendering of ya-wa kandan [夜話閑談], the meaning of u-kyō ekō-shi owarite, ta-nen no ya-wa kandan wo omoide, tō-ka kaikyū no namida wo otoshite [誦經回向シ畢リテ、多年ノ夜話閑談ヲ思ヒ出、燈下懷旧ノ涙ヲ落シテ] would be “after finishing the recitation of the sūtra(s), [I] remembered the many years of chatting at night, and shed tears of yearning beneath the [altar] lamps.”

**The toku-shu shahon has omoide [思い出], rather than omoidete [思い出て], but both refer to memories, recollections.

⁵Arishi-yo no monogatari tomo wo, ato-saki naku kaki-tsuzuke [アリシ世ノ物語トモヲ、アトサキトナク書ツヽケ].

Arishi-yo no monogatari tomo wo [在りし世]: arishi-yo [在りし世] means the bygone age, the world that is past; no monogatari tomo wo [の物語ともを] means along with stories of (a world that is no more).

Ato-saki naku kaki-tsuzuke [後先となく書続け]: ato-saki naku [後先となく] means without either end or beginning*; kaki-tsuzuke [書續け] means writing continuously.

Once again, the toku-shu shahon deviates from the text that is found in the Enkaku-ji manuscript: tsukuzuku to wasurarenu-monogatari domo wo, ato-saki to naku kaki-tsurane [ツク〻〻ト忘ラレヌ物語ドモヲ、アトサキトナク書ツラネ].

Tsukuzuku to wasurarenu-monogatari [熟と忘れぬ物語どもを] means (these) thoroughly unforgettable stories....

So this version changes “stories of a by-gone world,” to “stories that can never be forgotten.”

The genpon text, meanwhile, has tsukuzuku to wasurarenu-monogatari domo ato-saki to kaki-tsuke [ツクヅクト忘ラレヌ物語ドモヲアト先ト書付].

The meaning here is that these completely unforgettable stories were written down in (temporal) order, from beginning to end. __________ *The temporal inversion is something that is rather unique to the Japanese language.

⁶Sude ni ikkan to naru-mono nari [已ニ一巻トナル者也].

Sude ni [已に] means already*.

Ikkan to naru-mono nari [一巻となるものなり] means it had already become an entire volume of text.

In other words the author (who is supposed to be Nambō Sōkei) is saying that, writing incessantly since the conclusion of the (dawn) memorial service, he is rather surprised that his writings have already filled up an entire book†. __________ *There is a nuance of something being “too late” inherent in this expression.

†This is nonsense, since the variability of the language -- including numerous idiomatic usages that did not exist until long after Sōkei’s lifetime -- preclude the contents of Book Seven from having been written by a single author writing during the sixteenth century, let alone in a matter of no more than four or five hours.

The length of daylight in Sakai at the end of March 31 is approximately 12 hours and 30 minutes, and the dawn service would probably have taken an hour. The walk to the nearest mountains that are high enough for one to commit suicide by jumping from a height would have taken 6 or 7 hours from the Shū-un-an, which leaves no more than 4 or 5 hours for the writing of Book Seven -- an absolute impossibility.

The convention was that, for a retainer (or, in this case, a disciple) to follow the master into death, if not done immediately on the day of the master’s passing, the suicide would have to take place on the third anniversary of that date (so Sōkei would have had to get to the mountains before the end of the same day, otherwise his suicide would be meaningless).

⁷Shippitsu no seki ichi-ge wo tonaete hai-ka ni teisu [執筆ノ席一偈ヲトナヘテ牌下ニ呈ス].

Shippitsu no seki [執筆の席] means the room in which Nambō Sōkei was writing the text that became Book Seven of the Nampō Roku.

Ge [偈] refers to a gāthā [गाथा], a type of religious poem or song* -- originally such a verse when it occurred within a religious text or narrative (the type of which originated in India).

Ichi-ge wo tonaete [一偈を稱えて] means this one gāthā (written below) was recited or intoned.

Hai [牌] refers to a Buddhist mortuary tablet (usually called an i-hai [位牌]), an example of which is shown below.

The name of the deceased would be carved or written on the face of the i-hai.

Hai-ka ni teisu [牌下に呈す]: hai-ka ni [牌下に] means below† (Rikyū’s) Buddhist mortuary tablet; teisu [呈す] means to present, to offer (often in the sense of offering something by displaying it publicly, such as on an altar).

Here this text seems to mean that, after intoning his gāthā aloud, Sōkei placed the written page on the altar, as an offering for the repose of Rikyū’s soul (in other words, so that he would be reborn into the bliss of Amitābha’s Pure Land).

The toku-shu shahon has two changes: shippitsu no jo ichi-ge naru, soko hai-ka ni teisu [執筆ノ序一偈成ル、乃牌下ニ呈ス].

Shippitsu no jo [執筆の序] means the introduction, introductory section, or preface to the text that Sōkei was writing down.

Shippitsu no jo ichi-ge naru [執筆の序一偈成る] means there was a gāthā included in the preface‡.

Soko [乃 = そこ, 其處] means there, in that place.

Hai-ka ni teisu [牌下に呈す] means presented (or offered) below (in front of) the i-hai. This seems to mean that the sheet of paper on which the gāthā was written was laid flat on the altar, in front of the i-hai, as a sort of offering.

The genpon, taking its cue from the toku-shu shahon text, goes even farther afield from what was written in the Enkaku-ji manuscript: shippitsu no jo naru ko-ge naru, ue ni teisu, tada kou jō wo jutsuru nomi [執筆ノ序成ル小偈ナル、上ニ呈ス、只乞フ情ヲ述ルノミ].

Shippitsu no jo naru ko-ge naru [執筆の序成る小偈なる] means there was an preface to the writing**, and a short gāthā.

Ue ni teisu [上に呈す] means it (it is unclear whether this is supposed to indicate that the whole document, or just the gāthā by itself) was offered above (that is, it was placed on the altar).

Tada kou jō wo noberu nomi [只乞う情を述るのみ] means this was simply a way (for Sōkei) to express his emotions (on this sad occasion).

The toku-shu shahon text could be understood either way (though it tends to support the idea that this is at least in part a dedicatory text); but what is found in the genpon edition reads more like a narrative, than as the actual text of a dedication. __________ *It is said that gāthā were traditionally composed of units of 24 syllables. The reader should note that Sōkei’s poem (which is quoted at the end of this oku-gaki) consists of two units of two lines, each line of which has 12 syllables.

Gāthā were sometimes recited (usually mentally, rather than aloud) in rhythm with the breath, as a form of meditation practice.

†As with the expression tō-ka [燈下] (see footnote 4, above), “below the lamp(s),” which meant that Nambō Sōkei was seated on the floor in front of the altar (on which the lamps were arranged), hai-ka ni [牌下に] means that Sōkei was seated on the floor in front of Rikyū’s memorial tablet (which was also arranged on the altar) while he intoned this gāthā.

‡This is confusing, because the gāthā is found at the end of this oku-gaki (between the dedication and Nambō Sōkei’s seal), which, in turn, is placed at the end of the Nampō Roku, not the beginning (as this seems to imply). An oku-gaki of this sort could only be placed at the end, since it includes the date when the writing was completed. (A similar format is seen in Rikyū’s various densho, where he adds a few complementary lines, the date, and the name of the recipient, to the end of the document.)

**In this version of the text, shippitsu [執筆], “the writing,” seems to be referring to the completed text of Book Seven (though not necessarily bound into a book -- indeed, the evidence is that the documents in Nambō Sōkei’s wooden chest were mostly individual sheets of paper, of various sizes).

⁸Rikyū-daikoji sei-cha-montei Nambō Sōkei keishu [利休大居士淸茶門弟南坊宗啓稽首].

Sei-cha-montei [淸茶門弟] means a disciple of (Rikyū’s) Pure Tea.

Nambō Sōkei [南坊宗啓]: sometimes his name is written Sōkei [宗啓] (as here), and sometimes it is written Sōkei [宗慶], in documents surviving from his period. There does not seem to have been any definitive consensus on way to write it (which, as a matter of fact, was quite common during that period); but neither have I ever seen any documents written by his own hand that would lay the matter to rest, one way or the other (and in this his “name seal” -- which can be seen above at the end of the translated gāthā -- is of no help at all).

Keishu [稽首] means to bow down so that one’s forehead touches the floor; to prostrate oneself (in front of Rikyū’s mortuary tablet).

■ Hereafter follows the text of Sōkei’s gāthā. It is composed in four lines of 12 syllables each. There are no meaningful differences in the text of this poem between the three iterations of this oku-gaki.

⁹Ko-tō yū-shin ka san-haku [孤燈油盡花纔白].

Ko-tō [孤燈] means a solitary lamp (this is referring to Rikyū, whose teachings and approach were so different from that of his more popular contemporaries).

Yū-shin [油盡] means (the lamp's) oil is exhausted.

Ka san-haku [花纔白] means the flower* is not quite white.

The white flower indicates a pure heart, the person who can live their life fully in samadhi. Rikyū did not quite attain this level of spiritual purity (because of his association with Hideyoshi). __________ *The toku-shu shahon text uses the kanji ka [華], rather than ka [花]. Both, however, mean flower.

¹⁰Ittei sui-kan cha fu-sei [���鼎水乾茶不靑].

Ittei [一鼎] means one dǐng -- a dǐng being an ancient Chinese vessel in which ceremonial food was boiled and served (according to the Yì-jīng [易經]), making it roughly comparable to a jō-bari-gama [上張釜] (many of which also had three legs -- though they were considerably smaller). The analogy is to a kama.

A bronze Chinese dǐng is shown above.

Sui-kan [水乾] means the water (in the dǐng) has dried up.

Cha fu-sei [茶不靑] means the tea is not green. (Spoiled matcha is whitish or grayish-brown.)

¹¹Shi-kyo sō-bō san-kaku mu [師去草房三覺夢].

Shi-kyo [師去] means the master has departed (in other words, Rikyū has died).

Sō-bō [草房] is the Chinese word for a thatched cottage; a thatched hut.

San-kaku-mu [三覺夢]: san-kaku [三覺] refers to the three stages of the Buddha’s enlightenment. These three are:

◦ zì-jué [自覺] (ji-gaku), self-awareness, the state in which one realizes oneself;

◦ jué-tā [覺他] (kaku-ta), the desire to bring enlightenment to others; and,

◦ jué-xíng qióng-mǎn [覺行窮満] (kaku-gyō gū-man), the state in which the work of enlightenment is completed, and one awakens to perfection; the condition of the Bodhisattva.

One who has transcended all three of these stages is called the Buddha.

But here Sōkei is saying that the three stages are a dream (mu [夢]).

¹²Shitake hō-kyō rui kō rei [東風報曉涙空零].

Shitake [東風] means the east wind.

Hō-kyō [報曉] means announces the dawn.

Rui-ko rei [涙空零] means (and) tears of emptiness fall (like raindrops).

■ The page is only signed with Nambō Sōkei’s red seal (reproduced from the last page of the Enkaku-ji manuscript version of the Nampō Roku).

==============================================

◎ If these translations are valuable to you, please consider donating to support this work. Donations from the readers are the only source of income for the translator. Please use the following link:

https://PayPal.Me/chanoyutowa

0 notes

Text

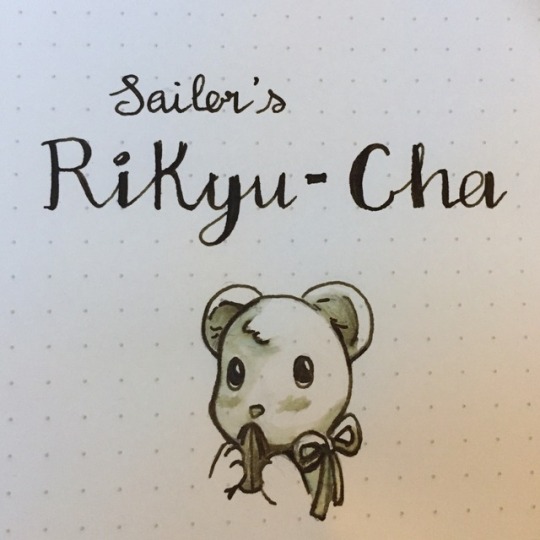

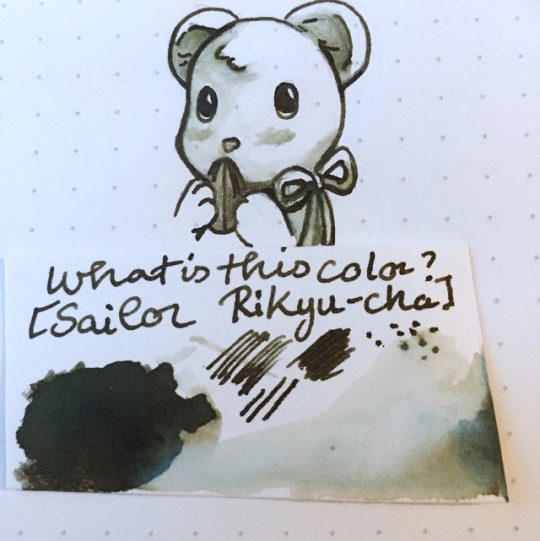

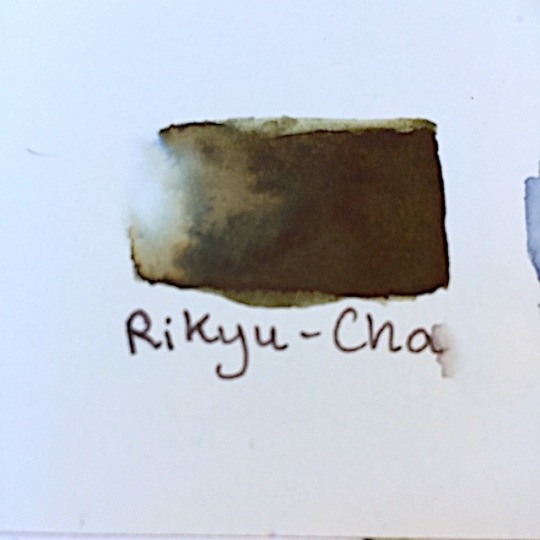

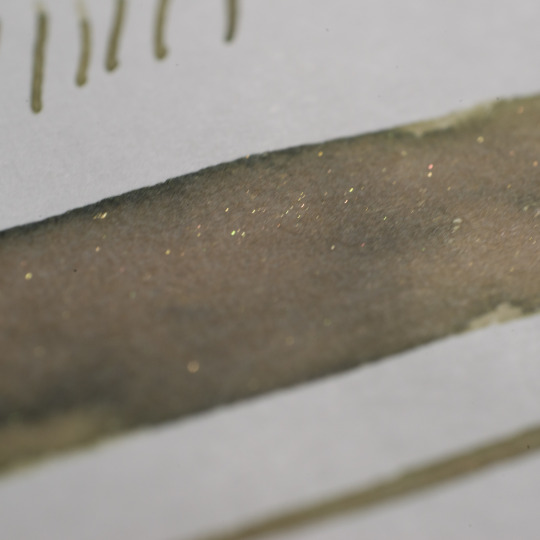

Ink Review: Rikyu-Cha by Sailor

Hey guys! Sorry for the late update but today’s ink of choice is Rikyu-Cha, part of Sailor’s Jentle series which suppose to depict colors from Japan’s season shifting. It was later re-released to as part of Shikiori line on smaller glass bottles.

Image sketched on Rhodia pad with brush and Wooden Custom Pen with German Bock nib

Sailor is one of the most well know Japanese ink and pen manufacturer from their own line of pens and ink to exclusive inks made for specific department stores such as Bungbox/Bungubox.

Tested on Rhodia Pad and Borden & Riley Paris Paper for Pens paper.

Swatch made on Strathmore 300 Smooth Bristol Pad

I managed to get the 50ml bottle when it was on closeout at Jetpens.com ( some other stores such as Anderson Pens are still carrying it at the moment). This ink is now sold as part of the Shikiori line which comes in a 20ml glass bottle instead. What impresses me about the old 50ml bottle compare to the new classy 20ml ones was that it comes with an ink feed that I can fill my pen without any possible accident although 20ml definitely saves me a lot more cubicle spaces. My first impression with this ink (and other Sailor ink I’ve used so far such as Sailor Jentle Sakura-Mori and Sailor Shikiori Shimoyo) is the strong plastic like smell coming from either the bottle or the ink itself. The ink’s color is fantastic as it reminds me of dried tea leave that my grandma likes to brew into drinks in the evening. When diluted it gives a full gamut of brown, dark green and a tinge of blue that would be interesting if you like to do a wash with it.

Drying time: Very Fast (3-5 seconds)

Water resistance: Pretty good (Will fade but still very much readable)

Feathering: None

Bleeding: None

Pricing:

$15-20 (50ml) at Pen Chalet, Anderson Pens and The Nibsmith

$12 (20ml) at Jetpens [Clearance]

(All pricing listed are taken off online information at the moment this post was written and only to be served as reference)

Thoughts

I’ve seen a lot of positive reviews on this ink and the actual product does not disappoint me at all. It flows really nicely on my M size bock nib and maybe next time I will fill this ink on a broad or even flex nib to fully showcase its range of colors.

This week’s color theme is blue and green so stay tuned for the next update!

#ink#fountain pen ink#green#green tea#dark green#brown#green brown#brown green#sailor ink#shikiori#sailor jentle#sailor shikiori#rikyu cha#rikyu-cha#sailor rikyu-cha#japanese ink#fountain pen ink review#ink review#inktober 2018

3 notes

·

View notes

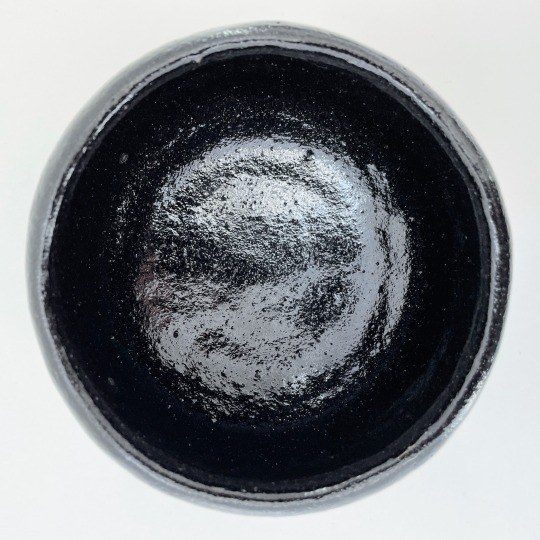

Photo

Rikyū, 1988, Kōichi Satō

In this poster for the 1989 film Rikyū (about the 16th-century tea master Sen no Rikyū), Satō creates an aura around the central motif of a bowl of tea with gradations of vibrant color. Rikyū was associated with wabi-cha, a style of tea ceremony characterized by simplicity, restraint and an austere beauty. Satō’s image of a single raku-ware tea bowl – a highly prized tea-ceremony vessel made from clay fired at a low temperature – is accompanied by a poetic text that translates as ‘beauty is unwavering’

Photograph: The Merrill C Berman Collection

#koichi sato#artist#art#illustrator#poster#rikyu#film#16th-century tea master sen no rikyu#tea#japan#wabi-cha#culture#the merrill c berman collection

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The first Raku tea bowl was created by Chōjirō, a tile craftsman, with the guidance of Sen no Rikyū. The prominent tea master was seeking a tea bowl for a style of Japanese tea ceremony emphasizing simplicity known as wabi-cha. The Raku bowl reflected the ideals of the wabi aesthetic, as it was formed by hand with an appreciation for the natural imperfections.

#raku#raku bowl#chawan#tea bowl#black raku chawan#sen no rikyu#wabi-cha#wabi-sabi#tea#bowl#matcha#chanoyu#tea ceremony#kyoto#japan#made in japan#green tea#way of tea#pottery#handmade#japanese pottery#japanese tea

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

Venduto all'asta il set da cerimonia del tè in oro di Toyotomi Hideyoshi!

Un servito da tè da 3 milioni di yen!

Il 27 Maggio in Giappone è stato venduto all’asta un inestimabile tesoro che si riteneva scomparso: il set completo da cerimonia del tè in oro quasi massiccio (in lega di 88% d’oro circa con argento) appartenuto a Toyotomi Hideyoshi che si crede sia stato usato anche da Sen No Rikyu.Questo servito era stato creato per essere usato nella sala da tè d’oro. Set da tè in oro originale Toyotomi…

View On WordPress

#cerimonia del tè#cerimonia del tè giapponese#cha#chado#chanoyu#chashitsu d&039;oro#Giappone#matcha#Museo d&039;arte di Hirosawa#oggetti per il tè d&039;oro#sala da tè d&039;oro#Sen No Rikyu#servito da tè d&039;oro#set da tè di Hideyoshi#set da tè di lusso#set da tè in oro#tè#tè giapponese#té#thè#Toyotomi Hideyoshi

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

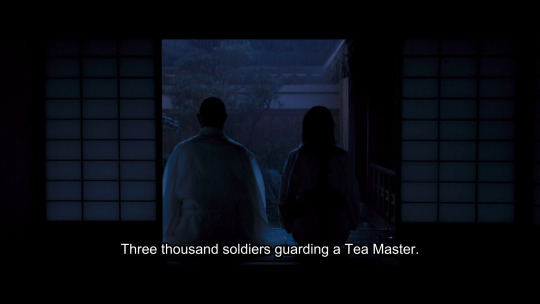

Ask This of Rikyu (利休にたずねよ, Rikyū ni tazuneyo) - 2013

#sen no rikyu#ask this of rikyu#tea ceremony#cha no yu#japanese culture#japanese film#ebizo ichikawa#miki nakatani#茶の湯

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Japanese Tea Ceremony

The Japanese Tea Ceremony, also known as chado or sado (“way of tea”) or cha-no-yu (“hot-water tea”), is a ritual in which tea is prepared and served, following a strict protocol. It is considered one of the classical Japanese arts of refinement, and there are even schools devoted to teaching the proper way to perform this ritual. The ritual consists of two major forms of assembly, The informal one is the chakai and the formal one is the chaji. The ceremony may vary in complexity, protocol, and duration. Traditionally, powdered green tea is known as matcha was used in these ceremonies. Furthermore, the Senchado is leaf tea was used rather than powdered tea in less famous ceremonies.

Tea was consumed as far back as the 7th century by meditating Buddhist monks to stay alert. Historical records report tea being given to Emperor Saga by a priest who has returned from China in A.D. 815. By the 14th century tea drinking had developed in an elaborate and expensive pastime enjoyed by the upper classes. There are some tea plants native to Japan but nobody ever thought of drinking tea made from their leaves until after tea was introduced to Japan from China.

The true tea ceremony was devised by Murata Juko (died 1490), an advisor to the Shogun Ashikaga. Juko believed one of the greatest pleasures in life was to live like a hermit in harmony with nature, and he created the tea ceremony to evoke this pleasure. The tea ceremony was influenced by samurai culture and Zen Buddhism, both of which emphasized discipline and simplicity. The tea ceremony was an important aspect of a samurai's training. Samurai class developed certain rules and procedures that participants of the tea ceremony were supposed to follow.

The form of tea ceremony practiced today was created in the late 1500s by the tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591). He served as tea master for Hideyoshi Toyotomi and is credited with simplifying the tea ceremony in accordance with Zen ethos and the concept of wabi (simplicity) and bringing the tea ceremony from the upper classes to ordinary people. He replaced Chinese porcelain with hand-molded Japanese ceramics formalized the austere aesthetic and emphasized the use simple tools that reflected the unpredictable aspects of nature.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Il maestro zen e l'assassino

Taiko, un guerriero che visse in Giappone prima dell'era Tokugawa, studiava il Cha-noyu, il rituale del tè,con Sen no Rikyu, un maestro che insegnava quell'estetica espressione di serenità e di appagamento. Per l'aiutante di Taiko, il guerriero Kato, quell'entusiasmo del suo superiore per il cerimoniale del tè rappresentava una vera e propria incuria degli affari di stato, e per questo decise di uccidere Sen no Rikyu.

Finse di fare una visita amichevole al maestro e fu da lui invitato a bere del tè. Il maestro, che era molto esperto nella sua arte, capì subito l'intenzione del guerriero, così disse a Kato di lasciare la sua spada fuori prima di entrare nella stanza per la cerimonia, spiegandogli che il Cha-no-yu è il vero simbolo della pace.

Kato non volle saperne. «Io sono un guerriero» disse. «Non lascio mai la mia spada. Cha-no-yu o non Chano-yu, io la spada la tengo». «E va bene. Tieniti la tua spada e vieni a bere un po' di tè» acconsentì Sen no Rikyu. La teiera bolliva sul fuoco di carbonella. Tutt'a un tratto Sen no Rikyu la rovesciò. Si levò sibilando una nuvola di vapore che riempi la stanza di fumo e di cenere. Il guerriero, spaventato, corse fuori.

Il maestro di rituale del tè si scusò. «E' stata colpa mia. Torna dentro a bere un po' di tè. La tua spada l'ho qui io, è tutta coperta di cenere; dopo la pulirò e te la darò». Stando così le cose, il guerriero capì che non era tanto facile uccidere il maestro del tè, e rinunciò all'idea.

Buona notte.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cha-no-yu or Sado (the Tea Ceremony) originated in the Muromachi period (1337–1573), when the aristocracy, including samurai and relations of the royal family, enjoyed this hobby where expensive china for teacups was used and lots of guests were invited. Thanks to Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), the Great Japanese Tea Master, the tea ceremony became more refined in style. Sen no Rikyu served Oda Nobunaga, the most powerful general of that time. After his death, he was employed by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, successor of Nobunaga. Unfortunately, frictions between Rikyu and Toyotomi led the General to force Rikyu to commit ritual suicide in 1591 – a fact Toyotomi regretted to the end of his life.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Purity”, estimated as constituting the spirit of the art of tea, may be said to be the contribution of Japanese mentality. Purity is cleanliness or sometimes orderliness, which is observable in everything everywhere connected with the art. Fresh water is liberally used in the garden, called roji (courtyard); in case natural running water is not available, there is a stone basin filled with water as one approaches the tearoom, which is naturally kept clean and free of dust and dirt.

Purity in the art of tea may remind us of the Taoistic teaching of Purity. There is something common to both, for the object of discipline in both is to free one’s mind from the defilements of the senses.

A teamaster says: “The spirit of cha-no-yu is to cleanse the senses from contamination. By seeing the kakemono in the tokonoma (alcove) and the flower in the vase, one’s sense of smell is cleansed; by listening to the boiling of water in the iron kettle and the dripping of water from the bamboo pipe, one’s ears are cleansed; by tasting tea one’s mouth is cleansed; and by handling the tea utensils one’s sense of touch is cleansed. When thus all of the sense[s are] cleansed, the mind itself is cleansed of defilements. The art of tea is after all a spiritual discipline, and my aspiration for every hour of the day is not to depart from the spirit of tea, whih is by no means a matter of mere entertainment” [-Nakano Kazuma, in the Hagakure].

In one of Rikyu’s poems...[he] refers to his own state of mind while looking out quietly from his tearoom:

The court is left covered with the fallen [needles] of the pine tree; no dust is stirred and calm is my mind. The [moon] far up in the sky looking through the eaves shines on a mind undisturbed with remorse. It is, indeed a mind pure, serene, and free from disturbing emotions, that can enjoy the aloneness of the Absolute:

The snow-covered mountain path winding through the rocks has come to its end; here stands a hut. The master is all alone; no visitors he has nor are any expected.

Suzuki, Zen and the art of tea / 1, pp.281-2

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 5 (28): Two Varieties [of Tea] and Two Bowls, with the Sasa-mimi Displayed on a Tray.

28) Ni shu ni wan sasa-mimi bon-kazari nari [二種二碗サヽ耳盆飾也]¹.

[The writing reads: (above) ichi no (一ノ)²; (between the ten-ita and the ji-ita) sasa-mimi fukuro iri (サヽ耳袋入)³; kasane-chawan (カサネ茶碗)⁴; (below) ni no (二ノ)⁵; kaku no gotoku isshu ha hakobite mo suru (如此一種ハハコヒテモスル)⁶.]

_________________________

¹Ni shu ni wan sasa-mimi bon-kazari nari [二種二碗サヽ耳盆飾也].

“Two kinds [of tea], two bowls, the sasa-mimi is displayed on a tray.”

The “two kinds [of tea]” may both be served as koicha, or the first may be prepared as koicha, while the second is served as usucha*. This is up to the host, and to the quality or flavor of the tea that is available to him†.

It is important to mention that, on account of their being tied in shifuku, both Shibayama Fugen and Tanaka Senshō assume that both kinds of tea will be served as koicha. (This was true of the previous arrangement also, even though the sasa-mimi, in that case, was not tied in its shifuku, meaning that the tea it contained was of a lesser quality -- for whatever reason‡.) However, both of these scholars have ignored the fact** that, in the early days, both the koicha-ire and the usucha-ire were tied in shifuku, to protect the tea that they contained. ___________ *While it will strike us as being odd that the usucha-ire is tied in a shifuku (and so lead us to doubt this interpretation of the kazari), in the early days the container of tea that would be served as usucha was also tied in a shifuku, to protect the tea -- specifically, when the matcha it contained had been freshly ground for that gathering (as was the preferred way of doing things in the early days). The decline in this practice only began when the custom of reusing the left over matcha that had been prepared for koicha as usucha later (whether during the same gathering, or on a later occasion), so it would not go to waste. This was a distinctly wabi sort of attitude that would have been counterintuitive to the ideas of chanoyu in the early period (when the norms of the practice, as it has come down to us, were generally focused on people like Ashikaga Yoshimasa, and the members of his court).

Since the arrangements associated with the sasa-mimi originated around the turn of the century, they sometimes partake of the style of chanoyu favored by Yoshimasa, and sometimes anticipate the practices of the wabi machi-shū chajin that would flower later in the sixteenth century.

†Though it might not be necessary to say so, certain varieties (or blends) of matcha lend themselves to preparation as usucha, while others are best served as koicha.

In the early days (and even in the present), the tea from the tea plantations was divided into six grades -- three (high, middle, and low) for the tea that had been harvested before the 88th day of the Lunar year, and three for the tea that had been harvested after that date. Some of the first and second of these were mixed (half and half) to form an intermediate grade, and some of the second and third were, likewise, mixed, resulting in five grades of hatsu-no-mukashi [初の昔] (the tea from the first harvest), and five grades of ato-no-mukashi [後の昔] (the tea from the second harvest). The upper two grades of each were almost always served as koicha, and the lower two were usually served as usucha, while the middle grade could be used for either. The five grades were priced accordingly, and, with the exception of the wealthy (who could afford to have their cha-tsubo filled with enough tea to last a year), the tea was purchased in small amounts, that could be ground (usually at home) for one occasion. Small amounts of tea were usually sold in boxes made of paulownia wood, since this kind of wood would stabilize the moisture content (the same kind of wood was used for the stopper for the large cha-tsubo, for the same reason), and some say that these boxes were the original sa-tsū-bako [茶通箱].

‡Each time the lid is removed from the chaire, the tea that it contains looses some of its flavor. In Jōō’s day, when serving koicha to five guests, the chaire would have to be opened five times (since each guest was served with an individual bowl of koicha). Rikyū abridged this practice by serving the shōkyaku an individual bowl of koicha, while doubling up on the remaining guests (so, in his case, the chaire would only have to be opened three times). Nevertheless, opening it only once means that any subsequent bowls of koicha will necessarily be inferior to the first. But since the quality of the tea leaves used for koicha is inherently better than those used for usucha, using the left over koicha tea to serve usucha is still offering the guests usucha prepared with a higher-than-usual quality of matcha -- while also allowing the host to use the left-over tea up before it degrades any further.

Unfortunately, the subtlety of flavor and aroma to which this argument refers is lost on modern day readers, because we almost always drink matcha that was commercially ground days -- and maybe weeks or months -- before sale, under conditions that would have appalled the people of Jōō’s or Rikyū’s period. In the classical period, just enough tea leaves were removed from the cha-tsubo, and these leaves were immediately ground into matcha using a hand-powered tea mill. The matcha was then quickly put into the chaire (which was supposed to be filled fully, leaving little empty space into which the aromatics could diffuse), and then the chaire was tied into its shifuku. Today, 8-hours worth of leaves are fed into mills that are mechanically turned so fast that the stones become too hot to touch with the bare hand (when hand-turned, the stones do not become noticeably hotter than room temperature), while the ground tea collects in a shallow gutter (but otherwise fully exposed to the air in the grinding room) that is emptied only at the end of the eight-hour shift. The matcha is then stored in a large, metal-lined box until a sufficient quantity has been ground to allow for mechanical packaging (which might take several days, depending on the size of the operation -- usually these boxes have a maximum volume of perhaps a half cubic meter, while the amount of matcha in them typically occupies less than a quarter of the box). Thus, the tea has already lost most of the volatile elements long before it is even sealed into cans and ready to be sent off to the distributors.

**Seemingly because both assume that these arrangements were created by Rikyu, rather than historically coming from much earlier in the century -- and, because the shin-nakatsugi seemed (to them) to establish the precedent for the koicha-ire to be displayed without a shifuku.

This shows a lack of understanding of both the shin-nakatsugi, and the purpose of the shifuku (at the time when Shibayama and Tanaka were active, the official teaching was that the shifuku was there to protect the chaire).

First, the original purpose of the shifuku was to protect the tea (not the chaire) by pressing the lid of the chaire (or other tea container) tightly against the mouth of the vessel, thereby preventing the volatile compounds that contribute to the flavor and aroma of the tea from escaping (this is also why the underside of the lid was covered with a thin gold foil pasted onto a piece of rather thick paper, and why, in the early days, the paper-backed-foil was changed before each gathering: when the lid is put on the chaire, and the shifuku is tied, the shifuku presses the lid tightly against the mouth of the chaire, with the paper allowing the gold to be pressed into all of the irregularities present at the mouth, and so effecting as good a seal as was technologically possible during that period).

As for the shin-nakatsugi, this container was made with a kiri-ai-guchi [切り合い口]. This kind of lid tightly matches the raised lip of the body (you can test this by lifting the lid off -- you should be able to feel resistance when you do so, and this shows how good the seal really is), once again providing one of the best seals technically possible at that time. As a result, a shifuku was not needed -- when the shin-nakatsugi was new (and so Shukō did away with it). However, making a kiri-ai-guchi was extremely difficult (especially without modern tools that can carefully match the inside of the lid with the lip: the body and lid are made separately, then covered with layers of paper and lacquered together, and then finally cut apart, so that the match between the two parts is virtually perfect), and expensive. Ordinary lacquered tea containers (including the natsume designed by Jōō) were not made in this way (kiri-ai-guchi natsume are available in the present, but Jōō‘s natsume had ordinary lids), and that is why the natsume is always described as being tied in a shifuku when it will be used to serve koicha.

Also, as the shin-nakatsugi ages, the wood continues to dry out and shrink, so that eventually the seal fails. This is why, when an old nakatsugi was used, it, too, was tied in a shifuku.

Consequently, if one wished to imitate Shukō’s arrangement of the shin-nakatsugi without a shifuku, then one had to use a newly made shin-nakatsugi. This is why Rikyū’s shin-nakatsugi, which was made for him by Hideyoshi’s personal lacquer artisan ten-ka-ichi Seiami [天下一盛阿彌], was revered and handled as if it were Shukō’s original: the nakatsugi was newly made, but its craftsmanship was identical to what Shukō’s shin-nakatsugi had been at the time it was made.

²Ichi no [一ノ].

“For the first.”

In the case of this temae, the tea in the sasa-mimi will be served first -- as koicha.

³Sasa-mimi fukuro iri [サヽ耳袋入].

“The sasa-mimi is [tied] into its fukuro.”

This piece of information informs us that the tea in the sasa-mimi is intended to be served as koicha.

⁴Kasane-chawan [カサネ茶碗].

“Chawan, one inside of the other.”

The chawan are stacked one inside the other, with a half of a dry chakin placed in between -- so that the foot of the upper bowl will not scratch, or soil, the lower chawan.

The lower chawan will be used to serve the first kind of koicha, and the upper chawan will be used when preparing the second kind of tea.

⁵Ni no [二ノ].

“For the second.”

The tea in the tea container that is resting on the floor will be served second.

The fact that the second chaire is placed directly on the floor suggests that the container itself is markedly inferior to the sasa-mimi*.

As a result, the only reason for displaying it would seem to be to inform the guests that two kinds of koicha will be served during the goza -- meaning that when such advance-notice was not necessary (for a particular group of guests), it would do just as well to keep the second tea container out of sight until it was time to serve the tea that it contained. ___________ *It would have almost certainly have been made in Japan, and more likely of lacquerware than of pottery.

Something needs to be explained about the sasa-mimi (since the fact that they were “karamono” would seem to imply that these were high-class tea utensils). These containers were originally made to hold scented hair pomade, which was a popular souvenir gift item. The ko-tsubo were also associated with the souvenir trade -- but in their case, they held one or two little servings of medicinal liqueurs.

In China, it was popular for people, when visiting locations famous for their scenic beauty, to buy souvenirs for their friends back home -- at the souvenir shops that usually infested the locals that offered the best views. Usually these were small bottles of special medicinal liqueurs for the men, and little vials of pomade for the women -- both of which were touted to be, frankly, sexually stimulating (the liqueur was supposed to enhance the man’s virility, while the fragrance in the woman’s hair was intended to excited him further -- on the theory that the more the man was excited, the greater his partner’s pleasure would be). These souvenirs were costly (though the cost was connected with the contents, not the containers); and their contents were soon used up, leaving just the empty jars. In China, the little bottles were usually thrown away; but in Korea (and in Japan), the containers were treasured -- perhaps even more than their contents had been -- since, after all, they were all that was left of the gift.

The little bottles used for medicinal liqueur could be rinsed thoroughly, or soaked in water, and after a while the smell would go away. However, the pomade was more difficult to purge (in that period when dish-washing soap had yet to be invented, and badly stained dishes were usually cleaned by scouring them with sand), which is why the sasa-mimi did not figure in the shōgun’s collection of tea utensils.

The use of the sasa-mimi, like the suiteki [水滴] (and the other little containers of that sort -- many of which were originally made for serving condiments on the dining table), was brought into use as chaire by the machi-shū, because, until trade with the continent resumed, it was almost impossible to get those continental objects that were not absolutely essential (which is precisely the kind of things that were the mainstay of chanoyu) -- while the number of chajin was only increasing year by year. Thus anything made on the continent was valued (usually disproportionately -- the yō-hen and yu-teki temmoku, for example, were mistakes that the Chinese potters threw away, and it was only profitable to import them because the minimal outlay -- usually a tiny sum for the person who looked through the potters’ middens to collect the unbroken pieces -- promised exorbitant profits, particularly when the numbers available were kept small).

⁶Kaku no gotoku isshu ha hakobite mo suru [如此一種ハハコヒテモスル].

“It may also be done [in such a way] that the one variety [of tea] shown like this can also be brought out [from the katte].”

Since the tea in the tea container that is resting on the mat will not be served until after the tea contained in the sasa-mimi has already been drunk, it is completely possible for the second kind of tea to be brought out from the katte at the time it is needed -- since, if the host does things as shown, the second container of tea might get in the way.

It is never wrong to arrange things in the manner depicted in the sketch, but it is also possible for the host to simply bring the second tea container out later.

——————————————–———-—————————————————

◎ Analysis of the Arrangement.

Here there is really not much that needs to be explained. In any temae where there are two chawan stacked together, the lower bowl is used first, and the upper bowl is used second, as Shibayama Fugen discusses in his commentary. After entering the room and approaching the daisu, the container of tea that will be used second is moved to the left side of the mat before the sasa-mimi is lowered*; and while the first kind of koicha is being served, the smaller chawan functions as a kae-chawan for the main bowl.

The service of the second variety of koicha will be focused on the tea, since the utensils are not important. For this reason, Tanaka Senshō adds that if the second container of tea is going to be brought out from the katte just before it is needed, then perhaps the second chawan should also be brought out at that time (with a new chakin and chasen arranged in it), Doing so immediately precludes any possible cross-contamination between the first kind of koicha and the second†.

Because two different kinds of koicha will be served, two chakin should be arranged in the chawan. One chakin is used while serving the first kind of tea, and the second chakin is used when preparing the other. ___________ *After the bon-sasa-mimi is lowered from the ten-ita, it is placed in front of the mizusashi, as usual, and then the pair of chawan are lowered as a unit and stood to the left of the chaire-bon.

During the preparation of the first variety of tea, the smaller chawan remains on the left side of the mat, just forward of the host’s left knee -- again, as is usually done.

Throughout, the alignment of the various utensils with the kane is as always.

†In this case, there is no reason for two chawan to be displayed on the ten-ita; thus, only one chawan should be arranged with the bon-sasa-mimi when the guests return from the naka-dachi.

This idea is explored at greater length in elsewhere in the Nampō Roku -- as well as in the book of secret teachings that was appended to the collection as the ninth book.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

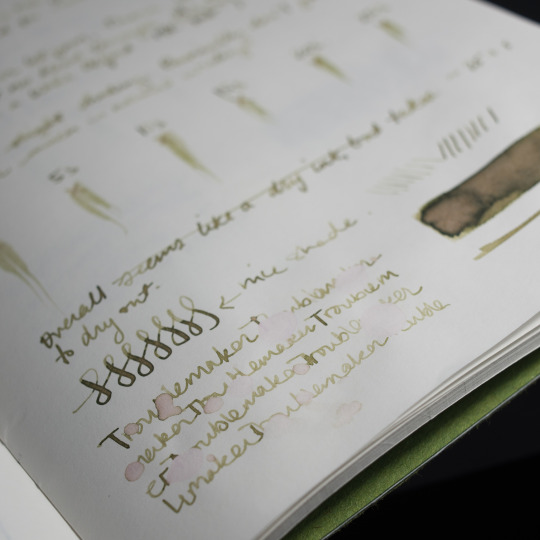

Troublemaker Inks - España Boulevard

Troublemaker Inks is a relatively new ink company operating out of the Philippines. They pride themselves on making inks with an honest price and homage to places and people local to them, so it‘s always nice to open a package and see inks and names with a hint of the culture that inspired them.

Today, I received Troublemaker’s Spring sample line, and from them I decided I’d try España Boulevard first.

This is a pale, greenish-brown ink with slight gold shimmer. It shades nicely and smears green. In concentration, it darkens to a raw umber.

On Tomoe River 68gsm, there is very slight ghosting, but no bleed-through. It’s not feathering so far either (with a Wahl-Oxford 14k semi-flex nib).

Drying time - expect complete dryness in the 45-60second range.

Waterfastness - Not waterfast.

Shading - Yes

Sheening - No

Colour - Brown with pinkish undertones, smears to green. Mid to light toned.

Feathering - No

Bleed - No

To be honest I had been looking for a good pale ink like this due to some issues I’m having with a Leuchtturm notebook (which I’ll discuss later). As pale inks go, this has just enough contrast in the shading that it’s not hard to read in normal lighting.

Overall, I am quite positive with this ink. It compares well to inks like PenBBS Liberte Guidant le Peuple (which is more straight desaturated brown) and Sailor Rikyu-Cha (which has similar brown/green properties, but is a bit darker).

If I were to criticize it in any way, it would be from the perspective that the shimmer arguably isn’t very noticable unless seen in the right light. I quite like this ink already on its own and without the shimmer, it makes for a very calming, conservative sort of look. I don’t *dislike* the shimmer exactly, but I think I would probably either buy this without the shimmer or just fill it unshaken for pens which may have issue with shimmer. As it stands, it just seems a bit extraneous.

This sample was purchased with my own money from the Troublemaker Inks website, and time permitting, I’ll post more along the same lines just to give you an idea of what they have available. I bought the 10 sample Spring pack along with a full bottle of an ink I’ll discuss soon. Shipping has always been quite reasonable, although you should be prepared for roughly a month’s wait for delivery, depending on where you live (I’m in Canada near Toronto).

2 notes

·

View notes