#ruby loftus screwing a breech ring

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Laura Knight

Ruby Loftus screwing a Breech-ring

1943

#laura knight#wwii#wwii era#wwii england#women at work#women in war#the home front#factory workers#women artists#women painters#war documentary#british artist#british art#modern art#art history#aesthetictumblr#tumblraesthetic#tumblrpic#tumblrpictures#wwii women#aesthetic#beautiful painting#ruby loftus

130 notes

·

View notes

Text

This 1943 painting by Laura Knight (1877-1970) depicts 21-year-old Ruby Loftus (2921-2004) working at an industrial lathe cutting the screw of a breech-ring for a Bofors anti-aircraft gun. Ruby became an expert in the production of breech-rings in just seven months – something that usually took years. After the war, Ruby and her husband John Green emigrated to Canada and she never worked in a factory or engineering again.

"Normal Women: 900 Years of Making History" - Philippa Gregory

#book quotes#normal women#philippa gregory#nonfiction#laura knight#ruby loftus#industrial lathe#breech ring#bofors#anti aircraft gun#expert#production#ww2#wwii#world war two#second world war#john green#emigration#canada#factory workers#engineering

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Miss Loftus had been brought to the attention of the War Artist's Advisory Committee as 'an outstanding factory worker'. Knight expected to do a studio portrait but the Ministry of Supply requested that she be painted at work in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Newport.

Making a Bofors Breech ring was considered the most highly skilled job in the factory, normally requiring eight or nine years training. Loftus was aged 21 at the time of the painting and had no previous factory experience. Her ability to operate the machine presented a considerable publicity coup at the time. However, it has been suggested that she was placed at the machine precisely for this reason.

Loftus was an outstanding factory worker who had mastered complex engineering skills in a very short space of time, and Knight was commissioned to paint her at work in the factory. Knight was fascinated by circus artistes and dancers, and she emphasises the balance and posture of her subject at work. Industrial machinery was a wholly new element in Knight's work but her technical accuracy was praised in contemporary reports: Knight, like Loftus, was proving herself in a traditionally male environment.

History note

War Artists Advisory Committee commission

Inscription

Laura Knight

---

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring is an oil painting on canvas measuring 86.3 by 101.9 centimetres (2.83 ft × 3.34 ft). It is one of the largest pictures of the wartime commissions, and the largest of the single-figure portraits they acquired.[5] The painting is in the realist style;[15][16][c] the cultural historian Gillian Whiteley considers the painting resembles the works of the Soviet socialist realists, and provides "an authoritative, optimistic, heroic and popular inspirational image".[17] The picture shows Loftus, bent over the lathe, which is in the act of cutting the screw of the breech. Her fingers rest on the machinery as she concentrates on the work she is doing.[15] According to the cultural historian Barbara Morden, Ruby Loftus is similar to other works by Knight in showing a female worker focused on her work.[12] The art historian Catherine Speck writes that Loftus's feminine features and clean hands "affirm the temporary nature of ... [Loftus's] work 'for the duration' " of the war; in this way the painting feels to Speck more like propaganda, rather than an image of Loftus going about her usual work.[18]

According to the cultural historian Barbara Morden, Loftus is depicted as "a young and attractive woman";[19] with brown curly hair not quite contained under a green headscarf or snood. She wears paint-splattered overalls and make-up, the latter emphasising her femininity.[19][20][21] By leaning over the workbench her face is placed in the horizontal centre of the picture, accentuating her importance. Her face is highlighted with the reflection of the light shining on the wet metal.[22][12] The social historian Elizabeth de Cacqueray observes that Loftus's head and the highlighted metal disk face each other along the diagonal of the picture, with Loftus's head scarf and face repeated ovals that reflect each other.[15]

The painting shows Loftus cutting the screw threads which would attach the barrel to the breech housing of the gun as sparks and water droplets come off the lathe.[12] According to Foss her workspace is "clean and efficient-looking",[5] while the natural approach to the work—and the level of technical details captured in the picture—"had the desired effect of testifying to Loftus's exploit [of being expert at her work] being an indisputable fact".[23]

The background of the painting shows the rest of factory floor, populated with women working at their benches; there is one man present, probably the foreman, given that he wears a tie.[24][21] The clothing worn by the women carries a patriotic tone, according to the art historian Mike McKiernan, as reds, whites and blues dominate.[25] According to the cultural historian Lindsey Robb, the painting—along with Frank Dobson's 1944 work An Escalator in an Underground Factory—"reinforce the representation of industrial work as female" during wartime.[24]

According to the art historians Teresa Grimes, Judith Collins and Oriana Baddeley, Knight adopts what they call a "documentary approach" to the machinery that "has the verisimilitude of a photograph but makes a far more powerful impact".[16] In this manner, the painting is similar to many examples of British wartime cinema that depicted the working class in an unsentimental manner.[16]

Laura Knight - Ruby Loftus screwing a Breech-ring (1943)

#studyblr#history#military history#art#art history#engineering#munitions#labour#employment#ww2#home front#britain#england#wales#ruby loftus#laura knight

339 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring by Laura Knight, 1943

#Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring#Laura Knight#1943#1940s#painting#art#illustration#vintage#wwii#world war II#rosie the riveter

88 notes

·

View notes

Photo

MWW Artwork of the Day (3/16/21) Laura Knight (British, 1877–1970) Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring (1943) Oil on canvas, 86.3 x 101.9 cm. Imperial War Museum, London

Loftus was an outstanding factory worker who had mastered complex engineering skills in a very short space of time, and Knight was commissioned to paint her at work in the factory. Making a Bofors Breech ring was considered the most highly skilled job in the factory, normally requiring eight or nine years training. Loftus was aged 21 at the time of the painting and had no previous factory experience. Her ability to operate the machine presented a considerable publicity coup at the time.

Knight was fascinated by circus artistes and dancers, and she emphasises the balance and posture of her subject at work. Industrial machinery was a wholly new element in Knight's work but her technical accuracy was praised in contemporary reports: Knight, like Loftus, was proving herself in a traditionally male environment.

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

From Wikipedia Picture of the Day; March 8, 2018:

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring is a 1943 painting by the British painter Laura Knight depicting a young woman, Ruby Loftus (1921–2004), working at an industrial lathe as part of the British war effort in World War II. The painting was commissioned by the War Artists' Advisory Committee, and is now part of the Imperial War Museum's art collection. The painting brought instant fame to Loftus, and has been likened to the American figure of "Rosie the Riveter".

Painting: Laura Knight

#wikipedia#international women's day#history#art#painting#Ruby Loftus Screwing A Breech Ring#Laura Knight#Ruby Loftus#World War II

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ruby Loftus screwing a Breech-ring, 1943, Laura Knight

Medium: oil,canvas

233 notes

·

View notes

Text

Postscript - Hegel’s Trowel: Recovery Story

Elaine Scarry in The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World writes about how tools and manufactured objects are extensions of the body into the world and thus ways of knowing it. The book identifies the ‘presence of the human body in the artefact’, and by homology the remaking of the human body into a concomitant made object/artefact. Making and constructive working, then, are crucial elements within any engagement of the body and the mind with the world, and of knowing the world through the body and the body through the world. That is to say, she supports Hegel’s doctrine of the self-creating power of work and making.

Scarry writes of how, unlike political torture and violent war - which are investigated in the first half of her text as extreme examples of hyper-negative un-making – transformative therapeutic positive making is involved in the re-making of the world, and as such, the reworking of pain, and in this making human subjects relieve the sufferings of contemporary and historical oppression and conflict. Published in 1985, The Body in Pain might also be useful in discussing the micro tortuousness and conflict found in the everyday world and how simple acts of making and creating can transform these pains. Covid 19 has brought non-conflict societies closer to the extreme world of unmaking in which the body is under complete attack. In which case everyday making will become, when we can return to making, a material and symbolic tool in our rehabilitation. Rescuing, repairing, restoring creativity and constructive activity to their proper path. Paradoxically, The Body in Pain argues the vocabulary of “creating,” “inventing,” “making,” is not, in the 20C, for some illogical ideological reason a morally resonant one. More than this, “material making” is ‘ethically neutral’ or conceived as an ‘amoral phenomenon’. But, she continues, ‘an unspoken question begins to arise’:

‘Given that the deconstruction of creation is present in the structure of one event which is widely recognised as being as close to being an absolute of immorality (torture), and given that the deconstruction of creation is again present in the structure of a second event regarded as morally problematic by everyone and as radically immoral by some (war), is it not peculiar that the very thing being deconstructed -- creation �� does not in its intact form have a moral claim on us that is as high as the others’ is low, that the action of creating is not, for example, held to be bound up with justice in the way those other events are bound up with injustice, that it (the mental, verbal, or material process of making the world) is not held to be centrally entailed in the elimination of pain as the unmaking of the world is held to be entailed in pain’s infliction? The morality of creating, of course, can be inferred from the immorality of uncreating […] That we ordinarily perceive it as empty of ethical content is itself a signal to us of how faulty and fragmentary our understanding of creation is.’

The Silk Mill workshop has now returned to making the Museum of Making museum. Post-covid-19 lockdown.

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring, 1943, Laura Knight - Credit Imperial War Museum

Steve Smith Workshop Supervisor, Museum of Making

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Laura Knight, Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring, 1943

#Laura Knight#art#womens art#20th century art#womens work#wwii#British art#Ruby Loftus#history#womens history

112 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring, Laura Knight

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jolly Olde England

Flying standby is a little nerve wracking - one doesn’t know until the last minute if there’s a seat for you! Luckily we got on the flight from Vancouver to Gatwick and were bumped up to First Class - thank you WestJet!! We had given ourselves a week to “acclimatize” before starting our long hike and good thing we did! This jet lag seems to get worse with age - 2 am and we’re wide awake...we’ve been managing about 4 hours of sleep each night! I wonder if I’ll just fall down dead on the sidewalk! But nevertheless we are soldiering on! We are staying in Gatwick and catching the train into London each morning, about 45 minutes. There are thousands and thousands of tourists everywhere and hundreds of different hop on-hop off buses carting us around. Nobody seems able to figure out which bus is which and there is always a confused mob around each bus stop. We saw all the main sites (Buckingham Palace, Tower of London, London Eye, Parliament Buildings, Trafalgar Square, etc) from the upper deck of our bus then hopped off to walk through the Tate Modern Art Gallery - absolutely fantastic! The guide on the bus referred to the new Prime Minister as “Bojo.” I loved that! A few protesters about with “Say No to Brexit” signs but they were heavily outnumbered by tourists! That was Day #1. Yesterday we went to the National Art Gallery - another fantastic exhibition with crowds taking selfies with Van Gogh’s “Sunflowers.” Then we braved the infamous London Tube to the British War Museum. Blair’s great Aunt, Roby Loftus (you can google her) was the subject of a famous painting during the war and the painting, by Dame Laura Knight, is on display here. The painting has the rather suggestive title “Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech Ring.” Sadly we found out that the painting is either in storage or in Manchester, they weren’t sure. But that left us time for a beer in a local pub before the long train ride back to Horley. Our last day in London and we’re soon off to St Paul’s Cathedral and the National Museum. Tomorrow we leave for Portugal.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Sure!

So, the elephant in the room with Beauty and the Beast in WWII is that it takes place in France, which was under partial or complete Nazi occupation from 1940 till 1944 (and when the occupation was partial there was a Nazi puppet government in the unoccupied part). I think in order for the plot to remain intact it has to be either transposed to a stable Allied or neutral country (at least for me as an Anglophone the US, Canada, or the UK are the obvious Allied options, Ireland the obvious neutral option) or a specific part of rural France without much Nazi presence (the primarily-Calvinist villages in the mountains south of the Loire come to mind; some were outright Resistance-controlled). Resistance Belle and Milice Gaston is a believable setup, but it seems in poor taste to me so my personal preference would be to transpose the plot to North America or the British Isles. Which gives us a ton of fun clothing options, especially for Belle, who would ABSOLUTELY work in a war industry:

From Life magazine, an American periodical. Photo by Margaret Bourke-White.

"Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring," a British propaganda painting by Laura Knight. In the Imperial War Museum in London.

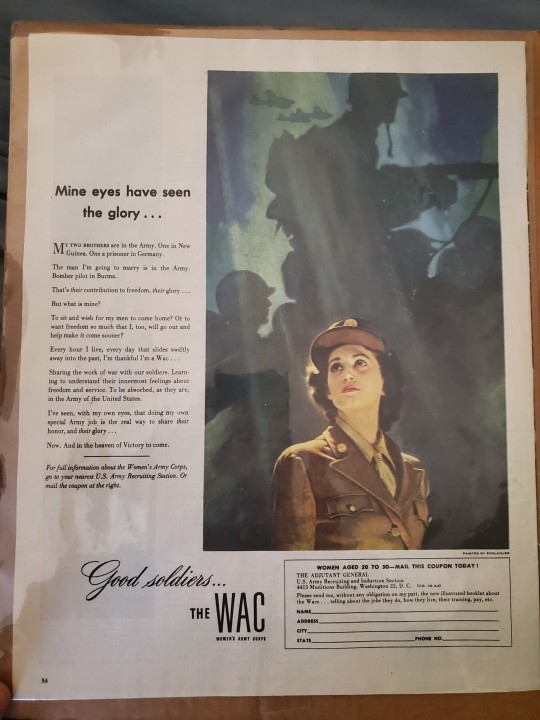

Or even join the military outright:

Women's Army Corps recruitment ad from Ladies' Home Journal, another American periodical. From my personal collection of historical ephemera.

A restructuring of the plot where the Beast is someone she meets not in or near her hometown but while she's elsewhere doing war work could be really interesting, although it would intensify something I'm already not crazy about in B&tB, which is the narrative's mostly negative attitude towards Belle's hometown in particular and rural life in general.

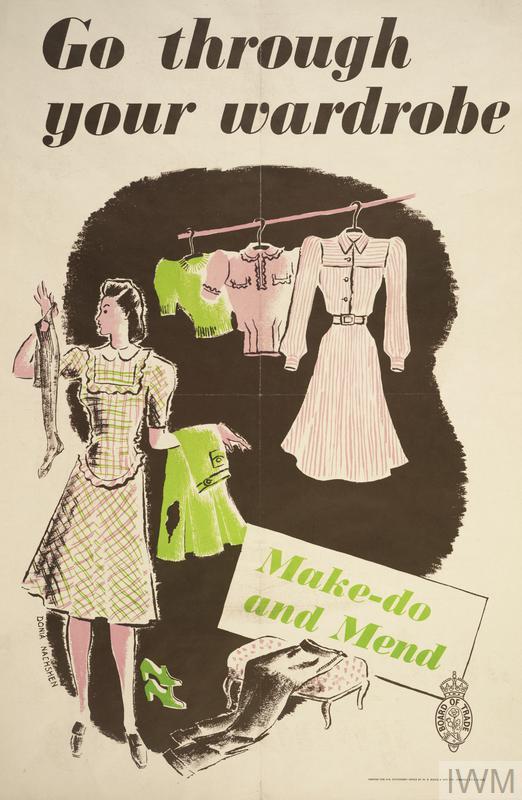

As for clothes, the watchwords in WWII fashions are austerity, practicality, and reusability. This sounds pretty boring but the results are still impressive by our standards today given the much more opulent and structured baseline. A few more images from my computer; I'm afraid I can't cite all of these individually but most of them are fairly easy to find in archives of wartime photography and Allied propaganda art.

These are the ones I can't really cite individually, although there are some clues like the name of the Indiana department store and the fact that one is in the aforementioned IWM collection. I love the one of the woman with the skeet-shooting rifle. The home front really was in its girlboss era in a lot of ways and this fact does significantly inform my interest in the war years, although it runs the risk of being exaggerated by people unwilling to wrestle with the other salient aspects of the period, like the fact that tens of millions of people died.

Cover of the Australian Home Journal, which as the name implies was much the same sort of magazine as the LHJ mentioned above. These are pretty austere cuts, materials, patterns, and silhouettes compared to styles immediately before and after the war, although "austere" does not mean "modest"; skirts were shorter and proto-bikini two-piece swimsuits came into wide use in this period. If you are a clothing manufacturer and your fabric allowance has been cut by 10% because the military needs more cotton and silk for uniforms, parachutes, and waterproof maps, it's good business to try to make skimpier styles happen.

Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in the 1945 film noir The Big Sleep. Bacall's suit is more interestingly patterned and the shoulderpads are impressive--eighties big shoulders were originally forties retro!--but the overall cut and construction are still pretty trim and spare.

Ingrid Bergman in a photoshoot for advertising Casablanca. The all-white in and of itself was supposed to make an outfit look a bit more formal during the war years. If Belle's community is really getting its civilian economy throttled, she might even wear something similar to this to the ball.

Or this, if we're going with WAC!Belle. I believe these are historical costumers/reenactors, but everything looks accurate to me.

More dance photos, one from the BBC, the other from the University of North Texas digital archives. Because sex-segregated workplaces and military formations kept getting moved around, lots of communities ended up with wild gender imbalances. In some places same-sex dancing became normal, in others they rustled up as many members of the "minority" gender as they possibly could and let them into the dance halls for free. To this day interviews with very old British women often have them speaking fondly of the free dances on or near military bases.

However, my personal favorite ballgown option is this:

Teresa Wright in Mrs. Miniver, a British propaganda movie that's widely seen as one of the most undeserving Best Picture Oscar winners of all time, not because it's bad but because 49th Parallel and The Magnificent Ambersons are considered significantly better. I like it, though. Wright's gown is a little too glamorous for most actual wartime situations, but then, B&tB and Mrs. Miniver are both movies with all that movie magic entails.

(Teresa Wright would make a fairly good Belle in general imo; in addition to her acting style, I've read essays calling her "the Anti-Pin-Up Girl" and her studio contract has this in it: "The aforementioned Teresa Wright shall not be required to pose for photographs in a bathing suit unless she is in the water. Neither may she be photographed running on the beach with her hair flying in the wind. Nor may she pose in any of the following situations: In shorts, playing with a cocker spaniel; digging in a garden; whipping up a meal; attired in firecrackers and holding skyrockets for the Fourth of July; looking insinuatingly at a turkey for Thanksgiving; wearing a bunny cap with long ears for Easter; twinkling on prop snow in a skiing outfit while a fan blows her scarf; assuming an athletic stance while pretending to hit something with a bow and arrow." Anybody getting Emma-Watson-as-Belle vibes should know that when Wright did period movies she did wear the same types of costumes as everyone else. Which isn't to say those costumes were good, although we do get some nice eye candy in the regrettably-titled California Conquest.)

I could go on, but I hope this helps, anon!

If Disney’s beauty and the beast took place in during WW2, what would the characters would be wearing? How would the war would’ve effected the plot?

That's not so much my era of expertise, but @monstrousgourmandizingcats would knock this discussion out of the park! MGC, care to take over?

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday #PortraitChallenge #watercolour of detail from Ruby Loftus Screwing a Breech-ring, by Laura Knight, 1943

@I_W_M

@StudioTeaBreak

#julesartvan http://www.artvan.co.uk/storydots/index.php?id=819

0 notes

Photo

Laura Knight - Ruby Loftus screwing a Breech-ring (1943)

1 note

·

View note

Photo

#Britain in #WW2: Ruby Loftus screwing a breech-ring. Miss Loftus had been brought to the attention of the War Artist's Advisory Committee as "an outstanding factory worker." Knight expected to do a studio portrait but the Ministry of Supply requested that she be painted at work in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Newport. (Portrait of a female factory worker operating a lathe.) 🎨(Artist: Knight, Laura. Source: iwm.org.uk; © IWM (Art.IWM ART LD 2850) #books #history #British #Allies #worldwar2 #Britain #amwriting #photography #art #painting #goodreads #writersofinstagram #journals #nonfiction #biography #memoirs #writer #wwii #veterans #womenshistory #supportourtroops #thankyouveterans #bookstagram 📚🎨 https://www.instagram.com/p/CAzBwXBBo15/?igshid=1vho086tnxrdn

#britain#ww2#books#history#british#allies#worldwar2#amwriting#photography#art#painting#goodreads#writersofinstagram#journals#nonfiction#biography#memoirs#writer#wwii#veterans#womenshistory#supportourtroops#thankyouveterans#bookstagram

0 notes