#somali literature

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Maxaa erey tafiir go'ay!

Maxaan maanso teeriya,

Every lost syllable tells in my heartbeat,

Every lost line is a scar on my heart.

- Maxamad Xaashi Dhamac ‘Gaariye’

#somalia#somali#somali literature#somali poetry#somali art#somali culture#somali language#suugaanta#somali gabay#somali poems#Maxamad Xaashi Dhamac ‘Gaariye’#abwaan gaariye

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The refugee's heart often grows an outer layer. An assimilation. It cocoons the organ. Those unable to grow the extra skin die within the first six months in a host country.

Warsan Shire, Assimilation

#Warsan Shire#Assimilation#Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head#refugees#heart#hard hearted#poetry#poetry quotes#Somali literature#British literature#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

My pregnancy was honestly, one of the hardest things in my life. What should've been a happy and beautiful journey often felt like I was drowning in a dark and invisible hole.

To cope - I started writing short letter to my unborn daughter - Riyyah, who I get to hold in my arms everyday and marvel at. Alhamdulilah.

In many ways - I am still recovering from it. In other ways - it has shown me a strength I never knew I had and given me a love I never imagined possible. I've shared some of those letters here:

#poetry#poem#love#personal#fgabdon#motherhood#pregnancy#islam#faith#religioin#faith in god#first love#storytelling#original story#writer#literature#novel#self love#tawakkal#mum#mummy#hyperemesis#somali

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

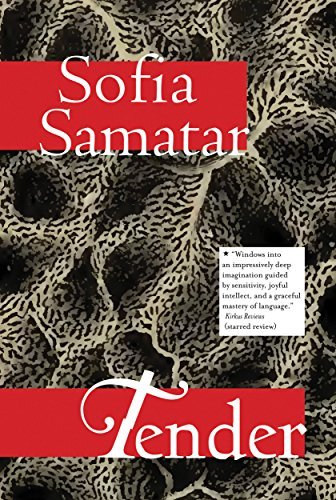

"How to Get Back to the Forest" is available to read here

#short stories#short story#how to get back to the forest#sofia samatar#21st century literature#english language literature#american literature#african american literature#somali american literature#black literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls#tw bugs#links to text

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have a weird, muddy opinion on how people on this site call The United States of America "USAmerica." Yeah, it works, and it removes any confusion about whether you're talking about the country or the landmass, but at the same time, it feels clunky? USAmerica just feels... idk, it's like you couldn't say it out loud without sounding goofy? You can say "the USA" out loud and it sounds good and makes sense, but at the same time the "the" makes it a bit awkward gramatically, and you can't just say "I'm from USA," but you can say, in text form, "I'm from USAmerica."

THEN there's the fact that people from that country are typically referred to as "Americans," and things from there as "American." When someone says "America," you don't think about the two connected continents the term could technically be referring to, you just think about the United States of America. It's an unusually "built" country within the region, made up of 51 smaller, unified nation-states that have combined into one very large, culturally and geographically disjointed country under one sprawling government, where every state, now functionally more of a province, retains the ability to have differing laws and economic policies, yet must answer to the grand government that controls them all as a whole, like if every country in Europe was ruled by one overseeing organization but were free to remain distinct as mini-nations rather than homogenized provinces. Two USAmerican states are far more different in legislation and culture than, say, two Canadian provinces are.

Given this, it makes sense for the country to simply be named "The United States of America." It's a bunch of states from America that are united into one big Voltron of a nation. Of course, though, you can't just say something like "this book is a great work of United States of America-ian literature," due to the way the English language works. Within the framework of English grammar, ideally, a country needs an adjective form of its name to concisely describe people and things from there, and while there are no hard rules as to how to go about that to my knowledge, there are a few different ways. You can apply a prefix to the country's name such as "ish" (British, Scottish, Turkish), "ian" (Brazillian, Russian, Indian), "ese" (Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese), "i" (Pakistani, Somali, Yemeni), or "an" (Guatemalan, German, Mexican), or if it sounds good you can just get funky with it and change a vowel or two (Norse, French, Dutch, Malagasy). And then there's Iceland with the "ic" (because they're special).

So BASICALLY, from THAT standpoint, using "American" as the USA's adjective makes sense. It flows well, does what it needs to. The problem, of course, is the overlap with the name of the landmasses. Technically, when one says "South American," they could be referring to either the continent of South America, or the south of the USA. Same with "North American." Now, nobody actually uses either of those terms to describe regions of the country, probably due to this overlap. A USAmerican could simply say "I'm from the north" or "I'm from a southern state," and you would understand given the context of them being a USAmerican. But then again, they couldn't just simply drop the country and compass-ional (whatever tf the term is) region in the same clause like people from any other country could without it sounding weird. "I'm from South France" makes sense as a sentence, as does "This plant grows in Northern Australia." "I was born in the South of the United States of America" is clunky and overly verbose, yet the lack of a proper country name without a "the" throws a wrench into that.

So what do we (typically) do? Just say "American" and let context do the work, clarifying if neccesary. "I'm from Southern America" obviously is not intended to apply to the continents, although it technically could. The reader, simply due to the context of knowing that South America is a continent and "America" usually refers to the USA unless otherwise stated, understands that the writer almost certainly means they're from a place like Texas or Louisiana, rather than Argentina or Chile. This way of writing/speaking is imprecise and requires unspoken context, but it gets the job done. America the country is a weird case in terms of its makeup, and that's reflected in its name. You're not referring to one country, you're referring to 51 micro-nations held together with one big fat federal government spread over them, like the thick plastic wrap holding a pallet of crates, boxes and sacks together as one shippable unit. And besides, nobody ever says "America" to refer to both continents, even though they technically could. They say "The Americas," because while technically one region, NA and SA are both very distinct and barely physically connected at all, held together by a single small landbridge (that has a canal though it now anyways, so you can't walk from one continent to the other without crossing water anymore).

So, in conclusion, idk, the term "USAmerica" removes the needless complexity of situational context, but it's somehow clunkier-feeling than the preexisting norm of just saying "America." I use and will continue to use the term USAmerica for brevity's sake since it's the norm on this site, but I'd certainly never use it anywhere else. America is an unusual country, and its name reflects that. A square peg in a language made of round holes, that can still fit if you turn it sideways a little. idk. I suppose the only real lesson here is that a) American exceptionalism is unintentionally portrayed in the language the country speaks, and b) English has a weird grammar system where things that are objectively correct within it sometimes don't "feel right" for no reason other than lacking succinctness.

#in case you couldn't tell I went up a dose on Vivance lmao#words pourin outta me like scraps of withered intestine out of a 2022 ivermectin true believer#like mayonaise onto a Subway sandwich after I ask the white girl behind the counter for “just a bit of mayonaise”#like [insert corny topical humor sequence no. 3]#English grammar#grammar#english#english language#grammar nerd#writing#usamerican

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

intros!

hey y'all! I'm new to Tumblr and this is my lil blog!

about me (from my carrd!) : I'm an entp 3w4, I'm studying biomedical engineering and cs. some general hobbies of mine include: studying foreign languages (I'm fluent in English and Somali, can speak French, and am learning Arabic + Korean), programming, video, astronomy, poetry, literature, visiting museums and observatories, making Pinterest boards and playlists, reading (especially dystopian), art, kickboxing and weightlifting, and all things food.

I'm actually not sure yet what I want to post on my Tumblr, but I'll start with some of my favorite pictures, and then I'll probably also share writing, my cats, and recipes :)

here are links to my pinterest and spotify too

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have any literature on sound changes involving ejective consonants? Specifically ejective consonants changing into something else?

I don't know of any general surveys, but several individual cases are of course found in literature in more detail. It would be worthwhile to have some compiled data on this though! For a start I'll collect some examples in this post.

The best-described case might be Semitic, where any handbook (or even just the Wikipedia article) will inform you about *kʼ > q, tsʼ > (t)s etc. being attested in Arabic / Aramaic / Hebrew. Offhand I don't know if there is a particular locus classicus on the issue of reconstructing ejectives for Proto-Semitic, though.

---

Cushitic, which I've been recently talking about, has open questions remaining especially in what exactly to reconstruct for various correspondences involving ejective affricates, but at least the development of the ejective stops seems to be well-established. Going first mainly per Sasse (1979), The Consonant Phonemes of Proto-East Cushitic, Afroasiatic Linguistics 7/1, three developments into something else appear across East Cushitic for *tʼ:

*tʼ > /ɗ/ (alveolar implosive): Oromo, Boni, Arboroid (Arbore, Daasenech, Elmolo), Dullay, Yaaku and, at least word-internally, Highland East Cushitic.

*tʼ >> /ᶑ/ (retroflex implosive): Konsoid (Konso, Dirasha a.k.a. Gidole, Bussa). (As per Tesfaye 2020, The Comparative Phonology of Konsoid, Macrolinguistics 8/2. Some other descriptions give these too as alveolar /ɗ/.)

*tʼ >>> /ɖ/ (retroflex voiced plosive): Saho–Afar, Somali, Rendille.

Presumably these all happen along a common path *tʼ > ⁽*⁾ɗ > ⁽*⁾ᶑ > ɖ. Note though that Sasse reconstructs *ɗ and not *tʼ — but comparison with the case of *kʼ, the cognates elsewhere in Cushitic, and /tʼ/ in Dahalo and word-initially in Highland East Cushitic I think all point to *tʼ in the last common ancestor of East Cushitic. (As per other literature, I don't think East Cushitic is necessarily a valid subgroup and so this last common ancestor may also be ancestral to some of the other branches of Cushitic.)

For *kʼ there is a wide variety of secondary reflexes:

Saho–Afar: *kʼ > /k/ ~ /ʔ/ ~ zero (unclear conditions).

Konso: *kʼ > /ʛ/ (no change in Bussa & Dirasha).

Daasenech: *kʼ > /ɠ/ word-initially, else > /ʔ/.

Elmolo: *kʼ > zero word-initially, else > /ɠ/.

Bayso: *kʼ > zero.

Somali: *kʼ > /q/, which varies as [q], [ɢ] etc.; merges in Southern Somali into /x/). Before front vowels, > /dʒ/.

Rendille: *kʼ > /x/.

Boni: *kʼ > /ʔ/.

though some of them again could be grouped along common pathways like *kʼ > *q > *χ > x, *kʼ > *ʔ > zero.

*čʼ > /ʄ/ happens at minimum in Konso (corresponds to /tʃʼ/ in Bussa & Dirasha). Proposed developments of a type *čʼ >> /ɗ/ in some other languages could go thru a merger with *tʼ first of all.

No East Cushitic *pʼ seems to be reconstructible, but narrower groups show *pʼ > /ɓ/ in Konsoid (corresponds to Oromo /pʼ/) and maybe *pʼ > /ʔ/ in Sidaamo (corresponds to Gedeo /pʼ/; mainly in loans from Oromo).

There is also an unpublished PhD from University of California at LA: Linda Arvanites (1991), The Glottalic Phonemes of Proto-Eastern Cushitic. I would be interested if someone else has access to this (edit: has been procured, thank you!)

Secondary developments of *tʼ and *kʼ in the rest of Cushitic, per Ehret (1987), Proto-Cushitic Reconstruction, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 8 (he also reconstructs *pʼ *tsʼ *čʼ *tɬʼ, but I'm less trustful of their validity):

Beja: *tʼ > /s/, *kʼ > /k/.

Agaw: *tʼ > *ts (further > /ʃ/ in Bilin and Kemant), *kʼ > *q (further word-initially > /x/ in Xamtanga and Kemant, /ʁ/ in Awngi)

West Rift: *kʼ > *q (and *tʼ > *tsʼ).

(The tendency for assibilation of *tʼ is interesting; although plenty of Cushitic languages get rid of ejectives entirely, none seems to have a native sound change *tʼ > /t/.)

---

The historical phonology of the largest Afrasian branch, Chadic, is much more of a work in progress, but I would trust at least the following points as noted e.g. by Russell Schuh (2017), A Chadic Cornucopia:

*tʼ > *ɗ perhaps already in Proto-Chadic (supposedly all Chadic languages have /ɗ/);

*kʼ > /ɠ/ in Tera (Central Chadic);

/tsʼ/ in Hausa and some other languages corresponds to /ʄ/ or /ʔʲ/ in some other West Chadic languages, not entirely clear though which side is more original.

Tera /ɠ/ alas does not seem to be discussed in detail in the Leiden University PhD thesis by Richard Gravina (2014), The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic; he e.g. asserts /ɠəɬ/ 'bone' to be an irregular development from *ɗiɬ, while Schuch takes it as a cognate of e.g. Hausa /kʼàʃī/ 'bone'. (Are there two etyma here, or might the other involved Central Chadic languages have *ɠ > /ɗ/?)

If Olga Stolbova (2016), Chadic Etymological Dictionary is to be trusted (I've not done any vetting of its quality) then Hausa /tsʼ/ is indeed already from Proto-Chadic *tsʼ, and elsewhere in Chadic often yields /s/, sometimes /ts/ or /h/. Her Proto-Chadic *kʼ mostly merges with /k/ when not surviving. (She also has an alleged *tʼ with no ejective reflexes anywhere, and alleged *čʼ and *tɬʼ which mostly fall together with *tsʼ, but also show some slightly divergent reflexes like /ʃ/, /ɬ/ respectively.)

---

Moving on, a few other examples I'm aware of OTTOMH include the cases of word-medial voicing in several Koman languages and in some branches of Northeast Caucasian (Chechen and Ingush in Nakh; *pʼ in most Lezgic languages). Also in NEC, the Lezgic group shows complicated decay of geminate ejectives, broadly:

> plain voiceless geminate in Lezgian, Tabassaran & Agul (same also in Tindi within the Andic group);

> voiceless singleton (aspirated) in Kryz & Budux;

Rutul & Tsaxur show some of both of the previous depending on the consonant, as well as word-initially *tsʼː > /d/ and *tɬʼː > /g/ — probably by feeding into the more general shift *voiceless geminate > *unaspirated > voiced (which happens in almost all of Lezgic).

in Udi, both short and geminate ejectives > plain voiceless geminates (plus a few POA quirks like *qʼʷ > /pː/, even though *qʷ > /q/).

Again I don't know if this has been described in better detail anywhere in literature, this is pulled just from the overviews in the North Caucasian Etymological Dictionary plus some review of the etymological data by myself.

Ejectives in Kartvelian are mostly stable in manner of articulation, but there's a minor sound correspondence between Karto-Zan *cʼ₁ (probably = /tʃʼ/) versus Svan /h/ that newer sources like Heinz Fähnrich (2007), Kartwelisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch for some reason reconstruct as *tɬʼ or *tɬ. The Svan development would then probably go as *tɬ⁽ʼ⁾ > *ɬ > /h/, after original PKv *ɬ > /l/.

I do not know very much about the historical phonology of any American languages, including if there's anything interesting happening to ejectives there; if someone else around here does, please do tell!

#phonology#phonotypology#ejectives#historical linguistics#sound change#anonymous#cushitic#chadic#lezgic#kartvelian

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Incoming message for Markus ‘Notch’ Persson: Title: "Take care of my two sisters, @zoesaldana and @rosariodawson.":

Hey Markus,

My name is Angelo, and I’m the Crown Prince of Somalia. I’m writing this because I’ve got a favor to ask—one you can’t refuse. If you do, you’ll lose business deals in my Somali nation. Think of it as a favor for a favor: you take care of my two sisters, and in return, I’ll help you get your revenge. I know you’ve been bullied, and I know the bullies have hurt your net worth. You dropped from $2.5 billion in 2015 to $1.3 billion in 2024. You’ve clearly been through bullying, but I’m here to help. I’ll make sure you get the most beautiful revenge in the world. Your net worth will climb from $1.3 billion to $30 billion in the coming decades. So, hang tight to my two sisters—Rosario and Zoe Saldana—because they’re your key to victory.

Markus says: “What do I have to do for them?”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “I encourage you to adopt them and treat them like your own sisters. You’ll never regret it.”

Markus says: “I can do that, no problem. But… can I have sex with them?”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “Yeah, if they agree, you’ve got my blessing. But if they don’t, it’d be awkward—just make sure they’re on the same page.”

Markus says: “Fair enough. But how did you know I was being bullied?”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “I’ve been following your story since 2015. I’ve seen your ups and downs. They bullied you because you refused to submit to their corruption. That’s why they’ve been dragging your name through the mud in the media. It’s clear you’re a victim.”

Markus says: “Yeah, they did bully me, that’s true. So, you’re saying Rosario and Zoe are being bullied too?”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “Exactly. If you don’t step in, they could end up in places they don’t want to be. The corruption they’re facing is unbearable. That’s where you come in—take them away from all that, protect them, and in return, when you meet me, I’ll help you secure some major business contracts. It’s a pretty solid deal, don’t you think?”

Markus says: “Hell yeah, it’s the best deal of the decade. I’m in. I’ll adopt Zoe and Rosario—don’t worry about it. I got your back.”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “Thanks, bro. You can call President Macron in France. He’ll help you secure the contracts you need, alright?”

Markus says: “The President of France? Macron? Alright, I’ll give him a call. Thanks.”

Crown Prince Angelo says: “Take care of my two sisters—you’re responsible for their safety now. Until we meet again. Also, check out my two blogs—you’ll find some very entertaining literature, that’s for sure.”

The end.

P.S.:

Synopsis of the letter:

In this dialogue, Crown Prince Angelo of Somalia reaches out to Markus “Notch” Persson, the billionaire creator of Minecraft, with a proposition. Angelo asks Markus to take care of his "sisters," Rosario and Zoe Saldana, in exchange for future business opportunities in Somalia and help with getting revenge on those who have bullied Markus, leading to a significant drop in his net worth. Markus agrees to adopt and protect Rosario and Zoe, asking if he can have a romantic relationship with them, which Angelo permits as long as they consent. The conversation ends with Angelo advising Markus to contact French President Emmanuel Macron to secure important business contracts and to ensure the safety of the two women.

The overall message is a favor-for-favor deal, combining protection, financial success, and revenge.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rosario Dawson (@rosariodawson): “You haven’t reached out to me in over two months. What’s going on?” Angelo (POW): “Your character belonged to the earlier seasons of 2024. That chapter has closed, and with it, your time on this particular network. That’s why I stopped writing to you.” Rosario Dawson (@rosariodawson): “A lot has changed since summer 2025 began. We’ve lost a significant amount of clout.” Angelo (POW): “I’m aware. That’s exactly what happens when I stop writing about Rosario. My pen holds power. When I stop speaking your name, the spotlight fades.” Rosario Dawson (@rosariodawson): “All those people who used to steal your intellectual property—your haters—are now under investigation. Did you know that?” Angelo (POW): “Yes, I did. That’s the inevitable fate of frauds. They didn’t just steal my work—they attempted to destroy my reputation. How foolish can one be? You can’t plagiarize my writing, echo my ideas to the world's billionaires, and expect to walk away clean. Eventually, the truth catches up. That’s exactly what’s happening now.” Rosario Dawson (@rosariodawson): “I’d never considered it from that angle. It’s like stealing from Stephen King (@StephenKing)—a master of horror. You can mimic the surface, but you’ll never replicate the depth. No one writes horror like he does. So when someone steals his work, it’s only a matter of time before they’re exposed. You can’t fake that level of originality.” Angelo (POW): “Thank you for putting it that way. That metaphor captures my experience perfectly. I don’t just write; I craft a unique kind of literature—war screenplays with deep psychological complexity and intricate structure. My work is sophisticated, layered, and impossible to duplicate. When others attempt to imitate me, they fail. Why? Because there’s only one Somali monarch who writes like I do. And yes—listen carefully—I said monarch. I’m not just an author or a screenwriter. I am a monarch, and that distinction matters. All of my detractors—the ones who plagiarized my work—did so without remorse. What’s worse, they even tried to tarnish my name in the process. That’s the height of stupidity: to steal from the very person who taught you how to speak with influence, with eloquence—how to address billionaires and world leaders. That’s been my reality for the past 18 months. I elevated you all. I gave you cultural currency. And how did you repay me? You betrayed me. Every last one of you. Now, I turn my back. Because only miserable people behave the way you all did. And no—don’t try to deny it. Misery is the only explanation for your actions.”

0 notes

Text

Hargeisa International Book Fair : the voice of Somali literature

From July 26 to 31, 2025, Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, will host the 18th edition of the Hargeisa International Book Fair (HIBF), the largest book fair in the Horn of Africa. Under the theme “Africa,” the event brings together authors, poets, artists, and over 10,000 visitors to promote reading, writing, and Somali culture. Hargeisa will resonate with pages and words during the 18th…

0 notes

Text

Labeeb (Somali)

Labeeb is an umbrella term encompassing a wide range of identities within Somali context. This includes effeminate male or mukhannath, transgender, transfem, transvestite, gender non-confirming, and intersex individuals. Most labeebs are born with masculine sex traits or male phenotype, embodies femininity in later life. A few are born with intersex variation.

Another synonym for Labeeb in Somali is Lagaroone (means passive homosexual men) “Labeeb identity” is deeply rooted in indigenous Somali culture, dating back to pre-colonial times. They are perceived as either woman or third gendered individuals within Somali society.

Etymology

There is no valid consensus regarding the origin of the term [more information needed]. There are few hypothesises regarding the origin of labeeb term in Somali:

The word Labeeb was adopted from Arabic language. The word originates from the root word "lubab," which means "core" or "essence." This reflects the core meaning of "labeeb" as someone who possesses deep understanding, wisdom, and insight. Although, the term "Labeeb" has a specific meaning in the Somali context, the meaning and connotations of words can evolve significantly over time.

Labeeb word may come from the portmanteau of Labe and Eebe or Lab and Eebe. The word Labe means double, dual and the word Eebe means deity/god. This reflects the connection between gender plurality and divinity, gender non-conformity and spirituality.

Sexuality and Marriage

Labeebs may belong to any sexualities including, heterosexual, homosexual, androsexual, gynesexual, bisexual, asexual, or queer. But some people conflate labeeb with khaniis (homosexual in Somali) due to androsexuality.

Throughout the Somali history, Labeebs are known to have relationship with other males. They may play feminine role in a relationship. In pre-colonial era, labeebs were able to marry either male or female.

History

Somalia has a long history of social acceptance of non-heteronormative relationships and gender variance. Labeebs were well-integrated into broader Somali society before the colonization. In Somali folklore, such individuals are often depicted as wise and respected members of the community. Queer people are known for their role in maintaining social harmony.

The mukhannath Labeebs, with their distinctive dress and mannerisms, played a vital role in arts and literature–often serving as poets, singers, and storytellers in the early Islamic periods. Under the ottoman empire, labeeb may served as royal attendants for women because many lacked sexual desires or preference for females.

The arrival of colonialism and the subsequent spread of radical Islamic ideologies (e.g. wahabi islam, salafism) brought about significant changes in the Somali society, impacting the Labeeb community. The introduction of gender insensitive interpretations of Sharia led to increased discrimination and marginalization of these people. Many Labeeb individuals were forced to conceal their gender identity or expression to avoid social stigma and persecution.

Despite these challenges, the trans and intersex community continues to exist within Muslim society. In recent years, there has been a growing movement advocating for the rights and recognition of gender-diverse individuals in MENA and East Africa.

Media

We don't have any clues of modern media representation of Labeeb in Somalia. Gender Identity and sexuality are not discussed positively in public discourse. In Somali Diaspora, there are significant representation of Somali labeeb or trans folks in SWANA and Somali queer spaces. There is a short documentary film called Labeeb, directed by Abdi Osman, which features Somali trans woman Sumaya Dalmar.

References:

https://www.facebook.com/share/1BmdqjqSwZ/

https://www.instagram.com/p/BjYwEkAh_jE/?igsh=MTNsdTFxaGgwOTNxdQ==

https://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/en/interpreters/Documents/SOGIESC_Glossaries/SOGIESC_List_of_Terms_Somali.pdf

https://www.somalinet.com/health/medical_terms/english/Androgynous

https://so.m.wiktionary.org/wiki/labeeb

https://www.somalispot.com/threads/subhanalah-a-gorgeous-somali-girl-pleads-4-help-4-medical-intervention-she-was-discovered-2-b-a-man.30980/#post-809975

https://www.somalispot.com/threads/being-intersex-in-a-somali-household-intersex-xalimo-tells-her-experience.109086/post-2811859

https://www.somalispot.com/threads/did-yall-know-theres-more-than-2-genders.107056/page-3

https://www.somalinet.com/forums/viewtopic.php?t=277239#p3216038

https://www.somalinet.com/forums/viewtopic.php?t=80832&start=60

https://www.somaliaonline.com/community/topic/72424-somali-trans-murdered/?do=findComment&comment=1003885

https://vjic.org/vjic2/?page_id=3556

https://theshinydiaries.com/tag/queerliterature/

https://artsandscience.usask.ca/news/n/3080/newsletter.php#:~:text=A%20screening%20of%20the%20documentary,Light%20refreshments%20will%20be%20served

1 note

·

View note

Text

Ubax deyrti baxayow udgoonow

Sida oogta waaberi iftiimow

He’s aromal, like a flower grown in autumn

You glow like an early gleaming morning

- Sahra Ahmad

#somalia#somali#somali literature#somali poetry#somali art#somali culture#somali language#suugaanta#somali gabay#somali poems#Sahra Ahmad

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Bless the Type 4 child, scalp massaged with the milk of cruelty, cranium cursed, crushed between adult knees, drenched in pink lotion.

Warsan Shire, Extreme Girlhood

#Warsan Shire#Extreme Girlhood#Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in her Head#type 4#beauty#hair types#hairstyle#Somali literature#BIPOC author#poetry#poetry quotes#Black History Month#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[ID: Two digitally drawn cat heads facing each other. They are smiling. Their noses almost touch. /.End ID]

Left:

Rhett Keller is 22, cis man, he/him pronouns, and gay. He goes to college for art and plays guitar in the band. He is a Japanese Bobtail.

Right:

Tea Dawson is 23, cus man, he/him pronouns, and bisexual. He goes to college for literature and plays drums in the band. He is (maybe) a Somali.

#TricksterTox#Tox's art#Tox's fursonas#Tox's fursona Rhett#Tox's fursona Tea#Tox's fursona Rhett notes#Tox's fursona Tea notes#Has ID

1 note

·

View note

Text

#short story collection#short story collections#tender: stories#sofia samatar#english language literature#american literature#somali american literature#black literature#african american literature#21st century literature#have you read this short fiction?#book polls#completed polls

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discovering Languages that Use the Arabic Alphabet

When people think of the Arabic alphabet, they often associate it with the Arabic language alone. However, a surprising number of languages around the world also rely on this script for their written communication. This alphabet has traveled across continents and cultures, influencing and blending with diverse languages in fascinating ways. From Central Asia to East Africa, languages that use the Arabic alphabet illustrate its adaptability and cultural reach.

The Arabic Alphabet Beyond Arabic

The Arabic script is one of the most widely adopted writing systems globally, second only to the Latin alphabet. Its journey began over a thousand years ago and has since touched the linguistic landscape of numerous regions, especially those with Islamic influence. This script often adjusted its form to suit new sounds and structures in different languages, making it a versatile foundation for many non-Arabic-speaking communities.

Persian: A Classical Example

Persian, also known as Farsi, is perhaps one of the best-known languages that use the Arabic alphabet. Although Persian and Arabic are from different language families, the adoption of the Arabic script in Persian dates back to the early days of Islam's spread into Persia. Persian adapted the alphabet by adding a few letters to represent sounds that don't exist in Arabic, a modification that has allowed it to flourish and develop a unique literature and poetic tradition.

Urdu: A Language of Poetry and Expression

Urdu, primarily spoken in Pakistan and parts of India, also uses the Arabic script. The beauty of Urdu lies in its calligraphy, which draws heavily from the aesthetic traditions of Persian and Arabic scripts. Urdu writing, known as Nastaliq, has a distinctive style that is both expressive and complex. In Urdu poetry, prose, and even everyday communication, this script has become an inseparable part of its cultural identity.

Pashto and Dari in Afghanistan

Afghanistan’s linguistic diversity includes Pashto and Dari, two languages that have incorporated the Arabic script into their writing. Each language has evolved with regional adaptations, but both have deep connections to Islamic literature and philosophy. The Arabic alphabet in Afghanistan, like in many other countries, provides a bridge between local linguistic traditions and the broader Islamic world.

Malay and Jawi: A South Asian Influence

In Southeast Asia, the Arabic script made its way into languages like Malay. Known locally as Jawi, the adaptation of Arabic letters to Malay was a result of Islamic influence on the region, starting in the 14th century. While Jawi has largely been replaced by the Latin script in Malaysia and Indonesia, it is still taught in religious contexts and preserved in traditional texts, especially in Brunei and certain Malaysian regions.

East African Swahili and Somali Script

Swahili, one of Africa's most spoken languages, once widely used the Arabic script, particularly in religious and cultural contexts. Although Swahili today is primarily written in the Latin alphabet, some regions still honor this tradition in religious literature and historical documentation. Somali also briefly adopted the Arabic script before moving to a Latin-based system, showing yet another example of the Arabic alphabet’s adaptability.

Kurdish and Beyond

In the Kurdish-speaking regions of Iraq and Iran, the Arabic alphabet is used with some adaptations to suit the unique sounds in Kurdish. Variations of the alphabet continue to evolve based on the needs of Kurdish speakers, allowing them to record their language and literature with ease. Beyond these examples, languages like Baluchi, Kazakh (in certain communities), and even some historical Turkic languages have all utilized the Arabic script.

Learning Arabic and Its Script

The Arabic alphabet’s reach across so many languages is a testament to its versatility. But for those interested in learning Arabic or deepening their understanding of its script, resources like Shaykhi offer a structured approach to Arabic and Quranic studies. Shaykhi is dedicated to teaching Arabic from the basics up to advanced levels, giving students the tools they need to read, understand, and appreciate not only the language but also its rich cultural and religious heritage. With a focus on Quranic learning, Shaykhi provides a pathway for anyone curious about exploring Arabic and its script in greater depth.

In Closing

Languages that use the Arabic alphabet are found across diverse regions and cultures, and each one adds its own flavor and adaptations to the script. From Persian’s poetic expressions to Malay’s historical texts, these languages reflect the adaptability of the Arabic alphabet and its influence on global communication.

0 notes