#sparse modeling imaging

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Hasta la fecha, se han realizado numerosas observaciones de discos protoplanetarios (o discos circunestelares) con ALMA.

#alma#ALMA super-resolution#astronomía radio#características de disco (anillos#discos protoplanetarios#DSHARP#early planet formation#eDisk#espirales)#evolución de discos#formación planetaria temprana#imágenes con sparse modeling#Ophiuchus star-forming region#planet formation disk substructures#polvo y gas en disco#PRIISM#protoplanetary disk rings#región de Ophiuchus#sistemas estelares jóvenes#sparse modeling imaging#subestructuras de polvo#super-resolución

0 notes

Text

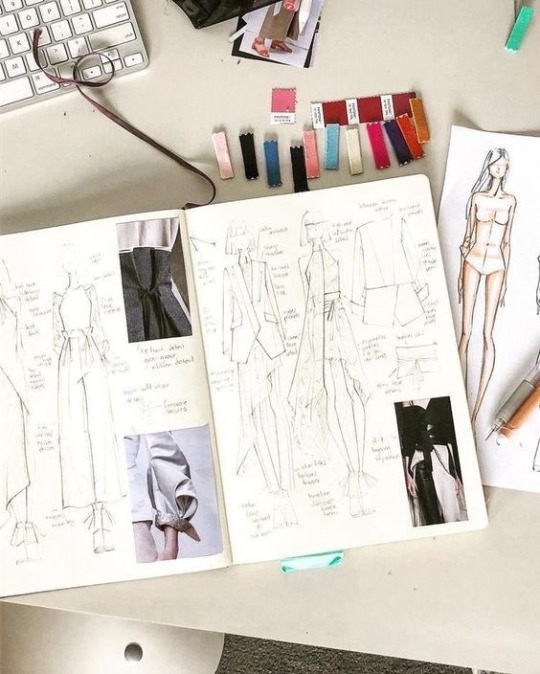

high fashion fashion

synopsis: you’re meeting with the top fashion designer in the country to get your measurements taken for haute couture: an exclusive, annual fashion magazine you had the luck to be chosen for

warnings: reader receiving, cunnilingus, fingering, strap-ons, swearing

w/c: 4.4k

a/n: momo part 2 here!

-ˋˏ✄┈┈┈┈

"miss minatozaki! the model is here to see you as requested!"

you shuffle around a little awkwardly as you stand behind the agent that had led you to the infamous fashion designer's lair. you were still a new name in the modelling industry so it came as a surprise when you booked one of the biggest fashion magazines in the country. naturally, that meant working with the best of the best, and minatozaki sana was the best of the best.

"come in!" a voice drifts out, it's high-pitched and honeyed, the kind of voice that lures people in and gets them to do whatever the speaker asks of them. you were cautious though, sana's reputation preceded her. tales of her perfectionism were not sparse, she was a difficult woman to please, and had been known to ruin careers with the shake of a head or the slight frown in her eyebrows.

the agent rushes you in, whispering about making sure you did whatever sana wanted you to do, and then taking their leave just as quick, terrified to be in the same room as the fashion designer of the century.

you wring your hands nervously, stepping forward and taking in your surroundings. it wasn't unlike any other studio you've been in. messy fabrics and half-completed outfits strewn over pages of designs and measurements, mannequins standing half-dressed and lifeless, and in the centre of it all, the mastermind of the methodical chaos you stood in, was minatozaki sana herself.

she tuts, making a note on the design she was currently working on, not having acknowledged your presence yet, so you stand there awkwardly, waiting for her to instruct you.

your eyes can't help but trace over her features while she works. it was only natural, you were a model, you learnt to have a sharp eye for the physical body, to be critical of yourself and others whether you were on the clock or not.

her face was perfect. she was wearing specs that perched neatly on a nose other models would pay for. her lips, although currently downturned in a frown as she perused her work, were set in a natural pout that accentuated her features, her eyes sharp and calculating behind the soft, round frame of her glasses. you could mistake her for the model for a big-brand eyewear company. your eyes glide down to her shoulder where her top slid down revealing pearly soft skin, and a sharp 90 degree angle, her collarbones protruding and proud. you're almost in disbelief at her beauty, how someone like her could've slipped under your radar, under everyone's radar. people knew her for the beauty she created, not the beauty she possessed.

you're so caught up in her you don't notice she's finally taken notice of you; quick, assertive eyes running over your own body, calculations and images of clothing pieces already forming in her head.

"y/n right?"

your eyes flick up to hers, blushing slightly at having been caught. you clear your throat, nodding, not trusting your voice to speak.

she puts down her pencil and steps out from the desk she was working behind, taking slow steps towards you. you were used to this, people staring at you, studying you. but under sana's gaze you felt like a baby deer again, like the first time you were scouted for your modelling agency. she circles you, humming here and there as she takes you in.

"i can see why mina chose you."

you cough awkwardly, "excuse me?"

"the editor. she handpicks the models for the annual haute couture magazine every year."

your eyes widen, she meant myoui mina. chief editor of the haute couture magazine. a limited fashion piece that only came out once a year and was revered by critics all across the country. the one you had the opportune luck to be selected for.

"r-right."

sana scoffs, "pretty face but can't speak. lucky you didn't go into acting."

you're a little taken aback at that, but you remind yourself this was characteristic of sana. this was in line with what you had heard. you would just have to grit your teeth and bear it, you could not afford to lose this opportunity.

"hmm. yes you'll do." she walks back to her work counter, heels clicking as she waves a hand dismissively.

"strip. everything. i'll take your measurements now and we can both get back to work."

you stutter, following after her, "d-don't you already have my measurements?"

she turns suddenly, raising an eyebrow as you almost crash into her. you realise she's a little shorter than you, though her presence made it seem she towered over you. "is there a problem?"

you blush, trying to create some distance between the two of you, "n-no ma'am! i just thought-"

"i like to take my own measurements. i don't trust the ones they sent me. after all..." she raises a hand, a manicured nail coming to trace your throat, from the middle of your neck to the tip of your chin. you hold your breath. "the notes didn't mention how devastatingly exquisite you are. i'll need to see if the rest of the... hardware matches that pretty face of yours." there's a dangerous glint in her eye, her lips curling up into a smirk as she watches your breath catch, then she's turning away and striding towards another work desk, leaving you tripping after yourself to follow her.

she quickly makes space on the counter, pushing aside sheets of drawings and pulling out a fresh new page devoid of any markings.

"well? are you shy or something? no one is allowed in here without my permission. we're alone darling don't worry." you can hear the teasing lilt in her voice, she doesn't need to turn away from her work for you to picture the smirk on her face.

you quickly rid yourself of your clothing, shivering a little in the air-conditioned workshop, reminding yourself that this was nothing out of the ordinary, you had been laid bare in front of beautiful women and men before, sana shouldn't be any different.

you hesitate when you reach your bra, but sana could smell your uncertainty.

"i said everything."

you gulped, undoing the clasp and sliding the straps off your shoulders, nipples hardening under the cool air of the room. you bend down to slide off your panties, stepping out of them carefully before coming back up, suddenly face to face with sana who's eyeing you with a hunger akin to the one of lioness. you turn to place your underwear with all your other clothes, but knowing sana was watching your every step lit a little fire in your lower stomach.

your toes clench on the cool tile of the workshop, you force yourself to take a breath before turning back to sana, and then letting her circle you again like her prey.

you almost jump when you feel her fingertip on your naked back, holding back sounds your mouth certainly shouldn't be making at work.

her finger slowly, slowly traces downwards, sana admires the smooth planes of your back, the sharp bones that jut out at your wingspan, the curve of your spine before pushing back out to your ass.

you don't even realise you're holding your breath until she pushes down slightly at the small of your back and you gasp.

then sana giggles. "cute."

her hand never leaves your body, she walks back around to face you, fingers tracing your arms, then your sides, squeezing teasingly at your hips.

"hmm... yes i can definitely work with this." her voice is lower, and you can't help but think she may be a little affected by you too.

she steps away again, grabbing a measuring tape, "you wouldn't mind doing a couple poses for me would you darling? i need to see which fabric would work best when you move around and sit or get into whatever other absurd positions momo might get you in when you take the photos."

you shake your head, irritated at the blush that was now definitely apparent on your cheeks. you were better than this, you took lessons on how to school your expression and bodily reactions for when you were forced into uncomfortable clothes and outfits.

sana nods towards a stool nearby, "just take a seat there, sit however's comfortable for now."

you follow her instructions almost robotically, wincing a little at the chill of the metal stool against the skin of your ass. you cross your legs, willing the arousal that was leisurely dripping out of you to stop before sana found out and fired you for being unprofessional.

she watches you wriggle around on the stool, trying to get comfortable with a smirk, treading forward when you're finally still. you try to look straight ahead, avoiding her gaze, but she cups your cheek lightly, forcing you to look up at her. she tilts your head from side to side, hums, then grabs the measuring tape and steps behind you, measuring your shoulder span.

"relax sweetheart, i can feel the tension in your muscles."

you let out a shaky breath, still refusing to speak.

"nervous?"

you shrug.

"you've done this before haven't you?"

you nod.

"are you not speaking because of the comment i made earlier? i didn't mean it y'know. it's not the first time i've rendered someone speechless before."

you gulp, unsure of the implications of her words, "r-right."

she giggles again, "almost thought i'd have to make you scream for me."

"w-what?!"

she hums, moving backwards again and ignoring your question, "lie down over there would you? on your front. if i know momo i know she loves her horizontal shots."

you shakily get up, moving to the mattress on the floor and laying down cautiously, feeling sana right on your heels.

it would be harder to hide your slick in this position, but you clenched your thighs together and did your best. the cool material of the sheets on the mattress brush across your already sensitive nipples in this state, and you fight the urge to let go and just go wild under sana's watchful gaze.

she hovers above you, noting down every twitch of your body, every arch, curve, bend. there's some rustling behind you but you keep focused on resisting your dirtier thoughts. that is until sana sits on top of your thighs.

you gasp at the feeling of her weight on top of you, right below your ass, "u-um-"

"i said to relax darling. i need to see how you'll feel when you're in this position." her excuses were getting sloppier.

"y-you do?"

"are you questioning me?"

"n-no! i'm sorry- please- um- please continue."

"good girl."

you feel your ears burning now as well, the blush having travelled across your cheeks and up. even you knew there was something other than fashion fitting going on here with that comment. but you still let her hands run over your back, even as they tease dangerously lower, down to your hips.

sana coughs, shuffling around, but her shuffling around was really her pushing her body up against your ass, essentially riding the back of your thighs. you can't help but release a choked-out moan, fingers digging into the skin of your forearms where you're resting your head, breaths coming in and out heavier.

she stops, smirking, then does it again, rocking forwards, eyes twinkling when you give her the exact same reaction, unable to control yourself.

"miss m-minatozaki-"

"just sana for you darling."

"... s-sana-"

"hmm?" she leans down, rocking forwards again, delighting in the moan you release, humming right next to your ear, her body laid almost completely on top of you.

"is this- is this still- are you still taking my measurements?"

she chuckles lowly, "what do you think?"

you whine, completely unsure what this devil of a woman wanted from you, "y-yes?"

"then why are you asking?" she giggles, finally letting you go, standing back up. "now, the couch please."

you inhale greedily, pushing yourself back up and wobbling over to the couch. your legs almost give out when you sit down, sinking into the material, and looking at anywhere but sana.

you're about to cross your legs again when she tuts, "ah ah. spread them."

your eyes widen, "b-but-!"

"but what? you already showed me a pose with your legs crossed, now i'll need to see one spread. surely you've seen it's a very classic pose? one of the outfits i'll have to design include pants and momo will definitely make you do this pose in them."

with nothing else to retort, you shyly spread your legs, the urge to cover yourself is overbearing. you wait for sana to say something, anything, prepared for your career to end here and now. you were so close to the big leagues too.

"run a hand through that pretty hair will you darling? elbow up."

you blink, doing as she says, dumbfounded as she steps closer, completely disregarding the obvious signs of lust at your core.

those hands come out again, one at your thigh, the other tracing down the tricep of the arm you have lifted above your head. with nowhere else to go, your arousal leaks outward, pussy drenched and needy as you hold your breath.

the hand that's at your thigh inches upwards, the one at your tricep downwards to cup your face again, thumb brushing over your lips that open just barely enough for her to fit her fingernail inside.

she can feel your shaky breaths on her thumb, can hear the whimper you let out when the hand at your thigh continues to trace up and down, closer and closer to your heat.

"s-sana..."

"yes darling?" her voice is husky, eyes lidded, lips open, whispering like she was sharing a secret even though no one else was around.

"i-i- i'm- i need-"

"what do you need?"

you gulp, fighting back against your better conscience, but the lust that's curling up inside your stomach wins out, "you. i need you."

she grins, "do you now?"

"yes please- sana please-"

"you're so cute when you beg darling. alright then. i'll entertain you." the hand that's at your thigh finally pushes forward, fingertips meeting drenched folds as you gasp in relief and desperation, hips pushing forward, trying to feel more of her.

"god you're so wet sweetheart. is this all for me?"

you're whimpering as she traces those practiced fingers of hers up and down your slit, just barely giving any pressure to your clit before dipping back down. "y-yes! all you all you-"

"well i have to be a good host and receive what you've given me don't i?"

she sinks down onto her knees, pulling your thighs towards her, taking off her specs and licking her lips devilishly as her eyes lock on her target.

your hands are about to move into her hair when she barks up at you, "no touching. you can touch yourself but you can't touch me."

you whine but obey, sliding your hands back up your stomach to grope at your chest needily, your nipples having been attention-starved since you took your bra off.

she grins, enjoying the view for a little before finally bringing her face closer. she blows on your puffy clit playfully, loving the way you squirm and whimper under her, before attaching her mouth to your pussy, sucking greedily.

"o-oh-!"

your hands grip your chest harder, wishing you could hold onto her head instead, but you have to settle for grinding down into her face, pushing against her grip at your hips while she eats you out, slurping loudly. the sounds are absurd, but your mind is too hazy to worry about being embarrassed anymore, not when your fingers are pinching and twisting your own nipples while you watch sana suck your clit into her mouth, her eyes locked on yours while she eats.

"g-god sana so good- so fucking good mmf- you- you- you're driving me insane god-"

sana flicks her tongue happily in response, one hand releasing your hip and coming down to play with your entrance. you clench around nothing, eager to take her in, and she obliges, pushing a finger in with your clit still in her mouth, curling it to hit the spot that only served to bring you closer to the edge.

"r-right there fuck- right there- i'm gonna- you're doing so good fuck-"

she starts pumping her finger in and out of you, the squelching sounds of your sex only become louder, an accompaniment to her suckling. you're flicking your fingers over your nipples, again and again, matching her pace, each stroke getting you closer and closer. then she adds in another finger, curling upwards, hooking into you, and you cry out, back arching, hips pushing into her face, shaking and trembling as you feel yourself fall over the edge.

sana continues to lick and nose at you while you come down, hands rubbing soothing motions into your hips and thighs. eventually, she slides back up, hand replacing yours over your chest and copping a feel for herself.

she's kissing your neck, chest, ears, all while you try and gain sense of yourself again. you turn your head with a pout, urging her to look at you. she smiles, knowing what you wanted without even asking, leaning in to kiss your pout away, your lips moving against one another as you hum at the taste of yourself on her lips,

she continues fondling your chest, rolling her fingers over nipples as you start to wriggle under her again, easily aroused.

she breaks away from your mouth with a smirk, "you're pretty when you cum."

you whine, burying your head in her neck.

"maybe i should tell mina and momo that. i think they'd get the best shots if you were mid orgasm."

"w-what?" your voice is shaky, still squiriming under her touch.

"hmm... you want another don't you? i've been working on something... special. how would you like to try it out for me?"

she doesn't wait for an answer, detaching herself from you and walking to one of her work desks. you can only watch after her, still spread open and tingly all over as she rummages through a drawer. your eyes widen when she pulls out a dildo, mind and vision suddenly clearer as she smirks, tugging out a corresponding harness and slipping the dildo into it.

then she starts to strip.

she leaves her top on, only removing her bottoms before stepping into the harness, the patchwork dildo hanging from her hips, looking strangely like it belonged on her.

she giggles when she notices you staring, doing a little spin, the fake dick swinging around ridiculously. "you like? i was going for... cutesy and demure." she plops down next to you, tapping her thighs.

you swallow nervously, pushing yourself up and straddling her.

"you can touch now."

your hands that were awkwardly swinging by your side finally come up to rest on her shoulders.

"answer the question."

"y-yeah- i- um- it's cute."

she giggles again, "that's good. need to make sure something as cute as you gets filled up with something just as cute hmm? then you can make all those cute sounds for me too."

her hands are relentless, tugging you down into her lap, brushing your hair over your shoulder, running fingers down over sides. she's always got to have her hands on you.

you huff when she teases the strap along your slit, feeling yourself dripping already. you try and catch her eye, pouting again.

she rolls her eyes, "just ask me if you want to kiss."

"can you kiss me?"

"see that was so cute! that's a good girl." then she's pulling you into her, latching onto your lips.

the makeout session that proceeds has you grinding down into her without even realising, and you take a hint of pleasure at her returning the movement, her own hips starting to rut up into yours. she sucks your bottom lip into her mouth, swiping her tongue across it before letting it go, invading your mouth still with the faint taste of yourself. when you break away to gasp for air, she moves straight to your cheek, then down to your jaw, neck, collarbones, sucking marks along her way, hands coming up to play with your chest again.

she pushes your breasts upwards so her mouth can reach skin easier, sucking and kissing, careful not to leave marks on you, knowing your body was your instrument in this line of work.

you moan when you feel her lips wrap around a nipple, the warm cavern of her mouth sucking the little nub, her tongue lapping over it with glee.

you're unabashedly rocking against her now, loving the tingle that went up your spine with every pass of the strap on your clit, her mouth still attached to your chest while you held the back of her head, keeping her against you while you moaned and whined into her.

she switches nipples, cool air hitting the wet, exposed nub. you shiver under her despite her actions only heating your body up past a temperature you didn't know was possible.

"s-sana-"

she hums around your nipple, always so focused on her work, the vibrations go straight to your core.

"need you- n-now- please-"

your nipple pops free from her mouth, "i'm not stopping you." then she's back at your chest, sucking and kissing, addicted.

you groan, looking down between you and shakily aligning your entrance with her strap. it takes a few tries and you're almost crying in frustration and sana's not helping at all, completely preoccupied with your chest, before you finally sink down, moaning low and heavy as you feel her fill you up.

"fuuck-"

sana sucks at the patch of skin on your left breast just a little harder in response.

you push yourself back up using her shoulders, then drop back down, cursing as your core tingles at the sensation.

you repeat the process, eyes locked on the way she enters and exits you, her strap coated in your essence, the squelching sounds mix with your whines and groans.

"fuck- fuck- fuck-" you start riding her, swearing each time she fills you up, setting up a rhythm that has you dizzy with need. sana finally decides to break away to watch her masterpiece bounce in front of her. fading bite marks and patches of red skin sway as she moves her hands down to your hips, pushing you down harder with each entrance, bucking her own hips up to get the strap that much deeper.

"fuck!" your hands on her shoulders tighten, feeling her everywhere inside you, around you.

"review it for me sweetheart." she husks out, "if you saw it in a magazine would you buy it?"

"y-yes- fuck- w-wait no i don't- i don't know-"

"no?"

"you don't come with it- fuck-"

she chuckles, hands moving again to grip your ass, squeezing the flesh between her fingers, "let's say i do. then what?"

"y-yes- yes yes fuck- yes i would-"

"mhmm? i want a more detailed review than that darling. i need to know how to make improvements."

"f-fuck sana- it's so- you're fucking me so- so good- it's good it's good-"

"other than good?"

"g-god you're so- it's um- fuck- it's cute and- i like the colours- a-and shit jesus christ- it fills me up just right- and i'm gonna- fuck- i can't- it's gonna make me cum-!"

"why don't i give it a helping hand then hm?"

"yes! yes- please- please- god- fuck yes-"

she pushes herself up, pulling you back down, surprising you with the amount of strength she had hidden, then she's thrusting up into you roughly.

"uh- uh- fuck- uh-" you're moans are cut up with every thrust, she's experienced, like she is in everything she does, panting with effort while her hips work, her arms pulling you down with every thrust up, you can't even keep track of where she's entering you, moving so fast it was a blur. or maybe those were the tears building up as it gets almost too much, your desperation to cum for her, to cum all over her.

"f-fuck!" you scream out, clenching down around her, hips moving of their own accord, shaking and moaning, almost blacking out from pleasure.

your breaths are heavy as you come back down, still with sana's strap lodged inside you, sweaty hands unwrapping themselves from around her neck, slumping down and resting your entire weight on the fashion designer.

sana hums, brushing through your hair and your back, letting you catch your breath.

when you finally gain enough of your bearings, you grunt as you sit up, sliding the dildo out of yourself, cringing at the mess you've made between the two of you.

sana only giggles, bringing a finger down to trace the length of the dildo and then bringing it to her own mouth, sucking it and humming around the taste.

your stomach twinges again in arousal, but you whine, too sensitive to go again, knocking your forehead against sana's shoulder as you avoid looking at her.

she lets you rest there for a while, but eventually stands up, carrying the dildo off with her to clean off. when she comes back, she has your clothes and a damp towel for you to clean yourself up with.

"i have another appointment now. feel free to stay as long as you'd like, just don't touch any of the designs. i'll send the completed outfits for you to try once they're done." she's all business again, but before you let her turn on her heel and leave, you croak out.

"w-what about you?"

"what about me?" she raises an eyebrow.

you blush, covering yourself now that you have enough shame to be embarrassed. she pays you no mind, following your eyeline and looking down at herself. then she realises what you're asking.

she laughs brightly, "no sweetheart you don't need to take care of me. but if i ever need another... trial customer... i'll be sure to ask for you." she winks, and then she's off, heels clicking in the workshop and door closing behind her.

you sink down into the couch, still processing exactly what happened. all you knew was that everyone was right to be terrified of minatozaki sana. though your fear came with a side of thrill you're sure no one else could've warned you about.

#sana#minatozaki sana#twice sana#sana x reader#twice sana x reader#minatozaki sana x reader#twice x reader#twice imagines#sana imagines#sana smut#twice smut#twice sana smut#minatozaki sana smut#dovveri

729 notes

·

View notes

Note

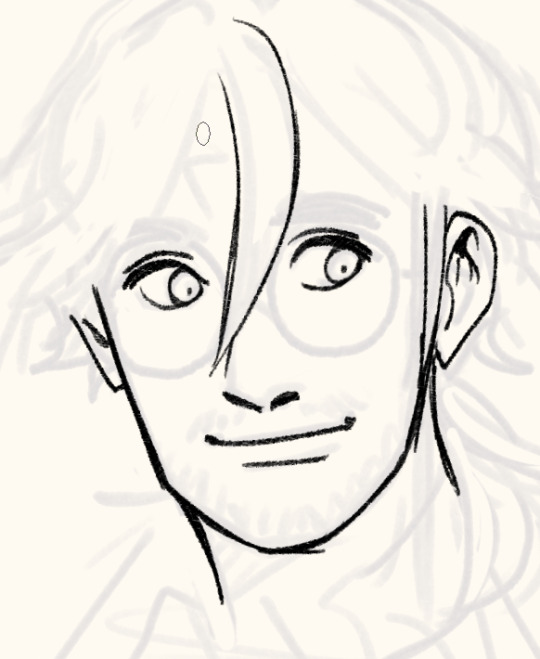

Ik vind het geweldig hoe levendig en karaktervol je gezichten zijn! – en de manier waarop je je haar tekent is ook prachtig! Zou je, indien mogelijk, wat tips kunnen delen over je proces?

Dank u!

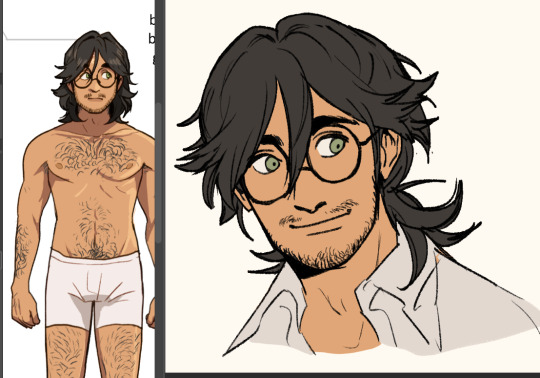

Process:

I sketch very loosely, usually using a pencil brush. Drawing quickly and lively is the priority here, but sometimes it means the drawing quality is really awful lol. I try to flip the image a few times to make sure it's not like, Wrong. Which it will be, to be clear. I hold my pen at a dramatic slant, so my faces are always distorted.

Here's a corrected face next to how I instinctively sketch it out (after flipping the image):

Bad

I wanted to say you can tell when I use 3D models to expedite this but actually they look identical because I not only correct my natural distortion but I also correct the 3D jank. Is correction my art style...?

Anyway, the rest of the piece.

I find it easier to use a thinner brush and go over the lines a few times to make it thicker than use a brush with thick line weight. This gives me more control and looks more natural.

I build up thickness on the beard with condensed hairs curling one direction and then in the other. Layering them makes it look thick and natural. (Mustache is more sparse, so it's just single curves.)

Then I pull up old colours to flat it. I usually work in only 2-3 layers, one for darks and one for lights - dark and light colours will fill differently, and splitting them like this means I can use a lasso fill faster. If there's a really detailed element, I give it its own layer for ease of lasso.

When colouring, big gloopy pen pressure is actually useful to livening up the piece. Make sure theres a light source. I always pick the one that makes the nose easier to draw. Add a second, deeper shadow in corners (like just under the chin) for some depth.

Now that he has more dimension, I can actually see there's a wee bit more to correct. What am I correcting? I don't know. It just looks wrong. I use mesh transform and the liquify tool until my brain stops hurting.

Good enough! Now for the mandatory filters.

I use mzxmmz's iikanji gradient sets (all 3), because they're very drastic and make interesting colour splits. I set them to 20%~30% opacity on a soft light correction layer.

And there he is. Crazy stalker handsome rogue Harry

As for the way I draw my hair, there's actually a quick cheat:

Draw the curls like ribbons (orange). Note how the thickness varies, like the angles of a ribbon. Add texture with little accent lines (green). Fill it out by following along the edge of the curl (purple). Repeat this with a bunch of different strands. It will end up looking very full and with a strong sense of shape.

You can establish this shape by just drawing single lines of the curl pattern/shape you want and then filling out the rest with the ribbon form, detail, and following-line.

Beautiful complex-looking organic curl pattern in minutes!

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mr and Mrs Smith AU: When Jane met John

Pairing: Hobie Brown x fem! Reader

Word count: 9k

Summary: Joining a spy agency? Check ✓ Hired in said agency? Check ✓ Getting a new fancy house? Check ✓ An entire armoury of weapons at your disposal? Check ✓ A new Husband? Check ✓ wait, what?

Tags: Use of Y/N sparsely, no specific physical description of the reader (except for her clothing), Hobie and R call each other by fake names (ie: John, Jane, Smith etc), spy AU, CW suggestive, CW food mentions, TW blood, CW violence, CW vomit mention, TW death.

A/N: Happy 1k! Happy reading!!!❤️

Navigation

Masterlist

Buy me a ☕?

The waiting room seems like it's designed to make you extra anxious. From the bright fluorescent lights that whir above, to the carpet that smells like a very harsh citrus soap. Add the metallic chairs that's incredibly cold under your slacks— It all makes you bounce your leg from the bundle of nerves inside your stomach. The people waiting around you don't help either, they all look like they came out of magazine covers. Hair all tied up in a perfect bun, pencil skirts that cinch their waist perfectly. Button ups that are ironed until there's no crease in sight.

You bite your lip, eyes glued on the steel door, to where your last resort is, to where your entire future depends on. Looking around the room full of models, it doesn't seem like you're applying for a security job.

Maybe you should've worn that pencil skirt that's gathering dust in your closet.

Even though you technically don't know what kind of job it is, you really need to get this one, or else. Your savings could only get you so far. An old ‘friend’ of yours recommended this ‘company’. It operates at the highest security, the risk is just as high, but the pay is higher. More than what you've ever earned in the five years you've worked anyway.

Flicking your eyes above the door, the light finally turns green from red, and a chiming sound can be heard as the door clicks open on its own. You still wonder where the applicant goes after their interview since you never saw them exit out the same door. A morbid thought passes by your mind: a gun plus a bullet to the head. The image makes you grab the rubber band on your wrist to slap it against your skin. It leaves the stinging pain for only a moment, but it's enough to throw away the vision from your brain.

An applicant enters and you look down at the piece of paper in your hand— you're next.

The number, 2715 is written in Times New Roman. You can recognize that font anywhere, for it's the same font used on newer gravestones, the same font on his— you slap the rubber band against your wrist again. This time harder than the last. The stinging stays for a minute more. Your heels tap against the carpet, the clock ticks, the fluorescent whirs, someone coughs and you want to punch them in the face— you slap the rubber band against your skin again.

Your ears perk up at the familiar chime like you've been Pavlov’d by the sound after waiting for three hours on that uncomfortable metal chair that has tiny holes that you've gotten your pinky finger stuck in on hour two.

With a deep breath, you saunter your way towards the creaking door, trying to summon all the confidence in your body. They may be watching so you do your best to not look as nervous as you feel like.

As you enter the room, the large screen in the center raises a curious brow. The light from the monitor shines a spotlight on the singular office chair right in front of it. The room is dim, save for the single light. The screen reminds you of one of those mall touch screens that shows you the map of the building. There's another door on the opposite wall, now you know where all the other candidates exit, and it's definitely not from a bullet judging from the clean floors.

With a tentative step, you cross the distance. Sitting down, the chair is a comfortable welcome from the last one you sat on.

“Am I supposed to push a button?” You roam your eyes over the circular shape up top. You surmise that it's the camera.

The calming sky blue screen flashes words,

> Hihi, welcome

“Hi?”

> Insert nail clippings

A box slides out below the screen, prompting you to take the ziplock with your nail clippings from your bag. It slides back in with a mechanic hiss once you place the plastic on the drawer, and the screen blinks to a couple of questions that you answer honestly.

> What's your ethnicity?

You don't falter. Answering it truthfully.

> Height?

You clear your throat, the lump is either from the nerves or how your voice faltered when you answered.

> Are you willing to relocate?

You wring your hands together on your lap. “Yes, absolutely. Nothing's holding me back.” Then the dreaded question pops up on the bright screen.

> Tell me about yourself

“Uh, I graduated top of my class.” You scratch the back of your neck. “MI6 agent for three–no, uh four years.” Chuckling shakily, you continue. “I got high merits…w-well until the thing— but I was on the road to promotion b-before it happened.” God, you hate interviews.

> Words that people would describe you with?

You blink, sucking in a breath. “Truthfully?” Joking, the screen doesn't appreciate your humour.

> Yes

“Oh, p-people would describe me as a… someone who has initiative. Cunning…” unfeeling— you slap the band on your wrist again. Sitting up right, you gaze at the camera like your eyes could see the person typing behind it. You guess it's a person at least. “Passed all my training with flying colours, infiltration, marksmanship, hand to hand, you name it. You tell me the job and I'll do it with no questions asked.”

> Are you okay with high risk?

“More than okay.” You answer quickly.

> With a team or alone?

“I'm alright with either, but I prefer alone.”

> Why did you get fired?

“You know why.” You say intensely, eyes boring holes into the screen. For a second you thought you flubbed it but the screen continues to flash a new question.

> Have you killed anyone?

> And why?

The question turns into what you're more accustomed to. “Yes, approximately…” you inhale sharply. “Forty three. Two unintentionally, the rest with various…weapons.” You mindlessly play with the loose thread of your blazer to get rid of the flashing images in your head. “As for why, that's confidential information.”

The robot or the person behind the screen seems to accept your vague answers for it moves on with the interview.

> Favourite food?

Your eyebrows knit at the sudden turn of question. “Uh, I have a sweet tooth, ice cream. I think. But I can't resist good popcorn.” Your tone wavers at the end.

> Have you been in love?

You laugh, but the question still flashes on screen, unchanged and unamused. Clamping up, you feel for the rubber on your wrist.

“I-I'm sorry but what is this part for?”

The screen remains the same.

“—No,” you remember that they've probably already known everything about you even before you applied. So you decide to answer vaguely, that seems to work out before. “Once, just once.”

> When was the last time you said ‘I love you?’

“A long time ago.”

> To whom?

“You know who.”

—

You're surprised that you got the job even after the disastrous interview. The suitcase is light in your tightly clasped hand. The belongings you've tossed inside are sparse, only packing the ones you only need.

The large wooden door looms in front of you, the street behind you is bustling and right across your new home is an expansive park. A park that looks like you need to pay just to get inside. The neighborhood that you're situated in can be described as exclusive, rich and very suburban. The kind of setting where parents would do anything to raise their kids in. Something you've never thought in your dangerous life to live in, more so even step foot in.

With an exhale, you unlock the door. It clicks open surprisingly, you doubted the company for a second when you pushed it in. Maybe they gave you the wrong address? Maybe something went wrong in their system and your name popped up instead of someone more worthy? Someone who's a better shot, someone who isn't as bat shit insane as you.

The long hallway greets you, the low warm light brings comfort to your rattling bones. Its carpet runner is soft beneath your sneakers, red and blue threads weaved around the thick cloth. Framed art is posted on the walls, the artist's name you recognize from some pretentious reality tv about selling mansions that you once drunkenly watched alone on a friday night.

You leave your baggage in the hallway. Opting to explore the cinnamon scented home. Its rich walls remind you of chocolate that you once got for your birthday. The furniture doesn't look like it came from Ikea, the oak is sturdy under your palm, no rough surface, no protruding nails that slashes your flesh.

You snap the rubber band on your wrist for the umpteenth time today.

There's an ornate door sitting on your right, robins and roses are carved on the wood. The biometric scanner is placed right next to the door, it’s a stark contrast to the traditional home. Flipping the cover open, you place your thumb on the smooth surface of the scanner. After a half second, the door clicks open, revealing a steel elevator. The bright light above it almost blinds you.

Your curiosity makes you enter the steel cage, roaming your eyes, you spot the buttons.

“Might as well.” You say to the emptiness of the house.

As the elevator door closes, the front door opens.

There's a lack of elevator music, perhaps that's the best since you always hated the cheery chiming of it. The second the door opens, you take a peek inside. The weird smell combination of chlorine and butter hits your nose.

“Holy shit,” you mumble in disbelief at the indoor pool and theatre. “A fucking pool under the house? And a fucking theatre screen in front? Which rich fuck decided that?” Your voice echoes, bouncing off the tiled walls of the pool.

Roaming the large room, eyes wide and strides small, you marvel at the high ceilings with the same warm tone lights hidden in the coves to soften the lights. You crouch down, letting the warm water lap at your hand.

There's a handful of sun loungers on the side, tables in between them for drinks and whatever rich people put on it. A projector hangs above the pool, an electrical hazard, you thought and an image of an entire pool party getting electrocuted lingers in your mind. You snap the rubber band against your wrist.

The popcorn machine helps distract you from the intrusive thought. Opening the machine, the popped kernels are still warm against your skin. You quickly scoop up a handful of it in your palm, the butter slicking your hand and your mouth as you eat it like how a baby deer eats grass.

You've had enough of the overly decorated basement, getting back on the elevator, you finish off your popcorn with one big bite. Still chewing, you wipe your hands on your trousers to press the shiny buttons on the elevator. The doors close as you chew loudly, eyes up on the screen showing the floors of the house, you don't notice the stranger standing outside of the opened doors.

Butter on your lips, you almost smack him on his pretty face.

“Christ!” You yelp, almost choking on a kernel.

“Close, but no.” He smirks, eyes flicking at the sheen on your lips.

Your husband, the title echoes in your popcorn filled head. His smile captures your attention, a ten megawatt grin that could power the entire posh neighborhood. His piercings glimmer in the warm light, and your eyes are glued to the ones on his eyebrows. Hazel eyes, the left one seems to be lighter than the other, watercolour eyes stare back at you, scanning your features. If you stare long enough you swear you can see patches of green and gray in those expressive eyes.

“John Smith.” He introduces himself, your husband, your partner. John doesn't raise his ringed hand for you to shake, instead he nods at you, waiting patiently for you to say your name. As if he doesn't know.

Clearing your kernel filled throat, you quickly run your tongue across your teeth (with your mouth closed of course) because you don't want to embarrass yourself further by having popcorn stuck in your teeth.

“Jane, Jane Smith.” You reach towards him to shake his hand, he raises a brow at you in turn.

“I don't do that, love, sorry.”

“Shake hands?”

“Yeah,” he looks to the left of your face, his eyebrow twitches slightly— a tell.

“Are you a germaphobe?” You ask before you could stop yourself.

“Not really, I've got issues…with intimacy.” John shrugs, the metals on his leather jacket clinks together. You think he'd rather be a model or a rock star instead of a spy with how he dresses and carries himself with confidence.

You smile knowingly, “We all do, but you don't have that issue. It's our first day of marriage and you decide to lie to your wife?” You click your tongue, eyebrow raised. “Not a very good first impression, John.”

He'll never get used to being called that basic name. ‘John’ takes your hand, it's warm, searing hot under your slippery hand. You'd thought his warmth would cook your flesh, you guess the butter on your palm would work wonders. You're starting to regret snacking. The calluses on his palm matches your own, a large scar across his palm tells you a story untold. Silver rings decorate his long fingers. There's a more simple silver bracelet on his wrist, a stark contrast to the ornate rings he sports on both hands.

He's handsome, you think, rightfully so. With his chiseled jaw that rivals any greek statue and eyes that could be mistaken for stars; he's tall too, so that's a plus. You lucked out on the fake husband department. Well, there's worse men to fake marry out there. Just judging from first impressions, you're glad he's the one you have on your side,

“How'd you know?” He asks, eyes narrowed.

“I'm very perceptive.”

“Trained?”

“Nope,” you hide your bundle of nerves with your casual tone. His hand is still clasped on your own, you don't notice it. “Just very good at reading people.”

“Did you have a stint at the BAU too?”

Too? You ignore it for now. “No,” chuckling, you finally notice the heat on your palm so you let him go. “Just…natural talent, I guess.”

“What’s under the house?” John asks, stepping aside so you could exit the elevator.

“A beating heart.” You curse yourself, fingers already reaching for the rubber band on your wrist.

To your surprise, John laughs. The sound is genuine, eyes crinkling in the corners. “I got the reference.”

“I figured.”

“I saw a black box in the office, you wanna check it out?” He points behind him with his thumb.

“Why? Do you think there's a beating heart in there too?”

“Maybe.” He plays along, walking beside you. “You never know with the company, for all we know there's a head in there.”

“Morbid.” You joke as he opens the door for you.

“Says you?” John keeps reminding himself of his real name whilst he memorizes the side of your face. He already wants to tell you his real name, not the one assigned to him by the suits behind the faceless screen he has grown familiar with. He says his name in his mind again, if he accidentally blurted it out, well, c'est la vie.

“Says me,” you shrug casually, trying to keep up with his wit and charm. You already think you're losing. You scrunch your face at the painting above the mantle. It's an art of two lovers doing the tango, if tango excludes clothes and includes intense snogging.

He chuckles right next to you, an airy laugh that has you smiling too. “A very brave choice. Not my taste, but whatever floats the company's boat. What's inside is a bit better though.” Your ‘husband’ reaches towards the frame of the painting, gently pressing down, it releases a metallic click as it reveals a secret compartment full of weapons.

You hide a snort behind your hand. The cabinet reminds you of your own. Unimpressed, you flick your eyes down at the office table, the large black box sitting on top of it is just begging to be opened.

Without a second thought, you open it. Taking out the bottle of expensive looking wine, you read the card that is tied in a neat ribbon around the neck.

“‘Good luck on your first day of marriage’” you look at the man beside you. He's incredibly close to you, his elbow grazing yours, lips slightly parted whilst he takes a peek at the wine. He smells of burgundy and leather, it calms your senses for some odd reason. “I prefer coke.” You practically shove the bottle in his hands. The glass clinks against his metal rings.

“The snorting variation or the fizzy one?” He asks, placing the bottle down on the narra table with an almost silent thud.

“The fizzy one.” You take his question at face value. He doesn't question why you don't prefer alcohol. Sitting down on the plush office chair, you open the laptop in front of you. It dings, needing a password to open it. “It needs a—”

Before you could even finish the question, he gives you a scrap of paper from the numerous envelopes inside the box. The password is printed on it with the same font as the one from the piece of paper you held a couple of weeks ago.

You type it whilst he rifles through the box. The home screen pops up, nothing too fancy or out of the ordinary. Except for the single application in the corner that's only labeled as ‘S’

Clicking it, a chat box appears.

> Hihi, follow man

John snakes up next to you, the harsh light from the laptop shines on his pensive face. You return your attention towards ‘your boss’. A picture of a young blond man pops up in the chat, there's a mole near his left eye, he sports dark eyebrows. And a look that says ‘daddy paid for my college!’

> 40.748817, -73.985428

“That's downtown I think.” John pipes up next to you, and you look at him like he just said the sky is green and the grass is blue.

> Take keys, take car. Bring car here

> 51.505554, -0.075278.

“A car?” You rhetorically ask.

“Must be a very expensive car, or an important one.” John answers back as he leans further down to take a better look at the monitor. His hand is on the back of your chair, his necklaces dangle on his neck like a pretty chandelier.

You both wait for more instructions but it doesn't come.

“Hihi isn't very talkative, huh?” Your voice echoes in the awkward silence.

“‘Hihi?’”

“Yeah, I thought I'd give it a nickname.” You think he's weirded out but with an amused laugh he pats your shoulder nonchalantly.

“Cute.” You don't know if he's referring to you, or to the nickname you dubbed your electronic boss. “I've separated our papers.” John says as you still contemplate his last comment. “Here's yours.”

“Thanks.” You scan the pile in your hands. Your own face greets you as you flip through it all.

“It has everything we need. Credit card, ID's, carry permit and a passport.”

“What's that one?” You point at the larger envelope next to John's pile. A smaller black leather envelope sits atop it.

He opens the large envelope, giving you the contents of it. “Marriage certificate. And this one…” shaking the leather envelope, whatever is inside of it clinks. Taking it out, he shows you the gold bands. “...our wedding rings.” Heat rises in your cheeks unavoidably once he says it softly. “May I?” Open palm reaching out, he beckons.

You try to remember which hand wears it. With a split second decision, you place your left hand atop his own. Carefully sliding the cold ring in your marriage finger, you stay locked in on his eyes that's concentrating like he's disarming a bomb.

John pats your hand and then inserts his own ring in his finger, mirroring yours.

“Guess we're married.” You shrug casually like your heart doesn't beat against your ribcage, like it's trying to escape its confines. “It feels kind of weird?”

“We are,” he flashes you his signature smirk. “And we'll get used to it, hm, wife?”

“Yeah, I'll adapt.” You say just barely above a whisper, hands suddenly clammy.

“That's my girl.” Throwing you a wink, he walks away from a flustered you.

Yeah, you got lucky.

—

Morning comes and you had the best sleep you've had in years. Even if you slept on an empty stomach last night, you still slept like a baby on the eight hundred thread count Egyptian cotton blanket. You stare blankly at the beige ceiling, hands roaming around the soft bed sheet like you're making a snow angel. Sleep ridden eyes roam around the expansive master bedroom to which your new husband has graciously let you take.

Speaking of ‘John’, his bedroom is just across your own. Surprisingly enough, he hasn't woken up yet based on the silence in the hallway outside, you hadn't pegged him as a late riser.

Breakfast calls for you when your stomach rumbles loudly, but you're too comfortable to even move from your spot. Something taps from your window that's facing the foot of your bed. A soft tippy tap of something hitting the glass that has you sitting up. Eyes blinking rapidly, you stare off a pigeon perched outside. Its iridescent feathers shine in the early morning sun, its beak tapping rhythmically at the window.

Sliding your hand behind you, blindly grasping at a pillow, you fling it across the room to scare off the bird. The pillow hits your mark and out flies away the annoying pigeon. With a sigh, you get off your ass to get ready for the day ahead. You don't want to be late to your first day out in the field, no use in rotting in your luxurious bed if you can't keep it after you get fired for being late.

You dress for the day and for the cool weather. Spring has come but the freezing temperature has decided to stay for a little while. With a cozy turtleneck and comfy slacks, you forgo the torturous device called ‘heels’ for a pair of trainers. Staring at yourself in the mirror, you shrug with a huff. And you snap the rubber against your skin once again.

Taking the chair off the doorknob and then unlocking the door, you exit your sanctuary. Closing your door softly, you find yourself in front of John's room. Judging from the soft snores, you notice that he’s still sleeping. You might be his fake wife but it's not your job to wake him up. So you continue down the hallway and into the kitchen to fix yourself a bowl of cereal.

Bowl in hand, you chew as you walk up to the rooftop. Unlocking it, the sun greets you with a comfortable heat, and you frown at it. You keep eating whilst you explore the space. There's a bountiful garden in the corner, raised garden beds full of fresh vegetables and fruit that is ripe for the taking. An outside dining area sits in the middle, you recognize the long table from a catalog you once read to pass the time at the dentist. You remember that it doubles as a grill and leg warmer in the winter.

“Fancy,” you murmur with your mouth full of grainy goodness. Sipping the leftover milk in the bowl, you place it on the expensive table to crouch down next to a bushel of strawberries to sniff. “Almost ripe,” you figure from the softness of the fruit.

A bird flies above you, it's shadow casting over you. With the sound of fluttering wings, the bird perches on the table, black orbs staring at you, head tilting like it's observing your presence.

“Are you the same fucking bird?” You question the pigeon. It coos at you, and then pecks at the ceramic of your discarded bowl. “Motherfucker—” standing up, you have the look of someone ready to square up with the feathered creature.

“Why are you fighting an innocent bird?” John appears with a mug of tea in his hand. You forgot to make tea.

“I wasn't fighting with it.”

“He,” your partner crosses the distance, the bird doesn't fly away from the close proximity. You raise an eyebrow at that. “might be hungry.” He gestures towards the strawberries behind you with his chin. “Think you can grab us one, lovie?” You're gonna need some time to get used to that term.

“It's not ripe.”

“I don't think he's picky.”

“It's too sour, it might upset his stomach.”

“He's a pigeon, he's used to eating shit off the pavement. I think that's fine, love.”

With an awkward nod, you pick the one that's redder than the rest. Throwing it towards John, he catches it with a practiced hand. He sits down before laying the fruit in front of the bird. You watch it unfold, the pigeon hops on the table, beak pecking at the seeds. You're intrigued at their interaction.

John sips at his drink, still in his sleep clothes. Toned arms in full display from the loose tank top he sports. Pajama pants hanging low on his hips, silk bonnet on his head. He only has one sock on his feet, you tilt your head.

“What happened to your sock?” You point at his bare foot curiously.

“Hmm?” He looks down, and he chuckles like he just realized the missing article of clothing. “Don't know, probably kicked it off while I was sleepin’”

“Oh,” you blink, “you should get ready, we might miss our target.”

He fakes salutes at you, drinking casually from his mug as you leave the rooftop. He doesn't miss how you didn't take your dish with you. Sighing, he watches the pigeon eat his fill.

—

You and John arrive at a pub. It's dim inside with only a few miserable patrons sitting sparsely at different corners of the musty establishment. They all look miserable, all having expressions from different points of the human emotion. But there's only one face you're observing— your target.

He sits alone on the bar stool, back hunched, eyes red and nursing a half filled pint of beer. Holding his face in his hand, blond hair raked in between his fingers, bomber jacket hanging loosely on his form, bags under his sagging eyes. He's the picture of someone who's on the bottom of the barrel.

John guides you with his hand hovering on your back. Not touching, at the same time still close, you are supposed to be a couple after all. You slide into a booth that has the perfect view of the target, but still out of his sight and out of earshot. The leather seat is worn down, tiny bits of it are ripped, at least it's not sticky. He orders for you, and you observe how he slyly roams his eyes towards the man, looking out for the keys.

He comes back with a plate of chips and dip. “Thought it would be weird not to order anythin’”

“Good call,” you take a chip whilst your eyes only briefly leave the target's back. “Thought you'd buy me a pint.”

“Did you want a pint? This early? Do you want to talk about it?” He half jokes as he takes a smaller chip.

“No,” you scoff, “and no. I just thought you'd order it instead of this.”

“You're not the only perceptive one in this relationship.” John looks over his shoulder to quickly do a once over at the forlorn man.

“Did you see where he's keeping it?”

“Inside his jacket, right side.”

You nod, “Is he carrying?”

“Not that I can tell.” He shrugs, licking the salt off his finger. “So, why'd you join?”

“Really? We're doing that?” You watch as the man gulps down his remaining drink and then orders a new one immediately.

“Yes, we're doin' that. Won't that make us work better together? To get to know each other a bit more?”

“Fine,” you silently huff. “No one else would take me, this is a last resort, I guess?”

“Bullshit, love, I think anyone would be happy to have you in their…agency?”

“Flattery won't get you anywhere, birdman.” A small smile appears on your lips, he beams at you. “Besides, who else is hiring for someone with the specific skill set that I have?”

He hums, while turning subtly to take a peek at the target. Returning his attention to you after seeing the blonde man still hunched in his stool, John takes another chip. “True, did you get kicked out from the last one?”

“Not really,” you stare at the crack on the wooden table. “You?”

“Not really,” he shrugs and you roll your eyes.

“You MI6?” He asks casually. “This your first time in London?”

“I'm not answering either of those questions.”

“C’mon,” he wiggles his left hand, the wedding band shines in the pub light. “Husband, remember? ‘sides, I won't tell anyone.”

You place your elbows on the table, smiling sarcastically at him. After a beat for his anticipation, you grin wider. “No.”

His shoulders fall, a chortle escaping his lips. “Cheeky.” Pointing an accusing finger at you, he quickly looks behind him, only to find the target sluggishly exiting the pub. “He's on the move.”

You both follow the drunk man like gravity is pulling you towards him. Walking the streets of busy downtown London, stranger's faces whizz past you. John has his hands casually in his pockets, yet he stays close to you, eyes flicking in the corners to check on you.

“Why don't you ask me a question? Y’know tit for tat?” He waits patiently for you to answer back, hell he'll even take a grunt at this point.

“Okay,” you surprisingly start the conversation on his behalf. “Have you killed anyone?” The passing pedestrians don't seem to notice you and the morbid subject.

Your partner snorts, nose scrunched up, eyes glued on the staggering target. “Nah. Have you?”

“I call bullshit,” you dodge a distracted woman scrolling on her phone. “Anyway, I have. I'm not exactly proud of it or flaunting it if you're thinking that I'm doing that.”

“Good, once you start flaunting it like a bloody trophy, you've lost it.”

You hum in agreement, the sound of a deep rumble in your chest as you two turn a corner. “Why do you think hihi needs us to nick the car?”

“Hihi” he chuckles, you turn to him with a serious face. “There's probably a stash of confidential information in the trunk or somethin’”

“Maybe a stash of weapons?” The man in front of you stumbles. “I don't see him as the type to harbor secret documents.”

John nods, “a highly infectious disease then?”

“Christ, we better drive carefully once we get a hold of it.” You turn to him briefly. “Maybe it's a really expensive sports car and he's all sad and mopey because he's gone broke after buying it?”

“Got a whole story now, huh?” He pushes you lightly with his leather clad shoulder, and you smile softly. “You good at pickpocketing him?” Your partner gestures with his chin, said target is walking into traffic. He seems unbothered by the oncoming vehicles. John curses under his breath.

“We should do that now before he kills himself.” You speed walk across the crossing, grabbing the drunk man before a car hits him.

Arms enveloping around his bomber jacket, swiping him away and quickly carrying him to the footpath, you save him before an suv hits you both. The car honks loudly and angrily as your target groans in your arms like he's about to hurl the contents of his stomach.

John punches the hood of the car, pointing at the driver accusingly. A distraction for you to take the keys hidden in the man's jacket.

“You almost hit my fuckin' wife, you wanker!” Your partner yells, covering the sound of jingling keys in your expert hand. He plays the part well.

Surprisingly, the target straightens up in your hold, a split second after you pocketed the car keys inside your own coat.

“Y-you,” he slurs, feet struggling to keep himself upright. “Dickhead!” Slamming his fists on the hood with a loud *thunk, he joins John who gives you a look and a shrug. The drunken yelling gets louder and the driver now exits his car with an equally angry look.

John takes this opportunity to come back to your side, hand holding your elbow, he leads you away from the screaming match as more and more people try to intervene.

“Got it?” He whispers closely to the shell of your ear, sending goosebumps to rise in your arms.

“‘course I did.” You jingle the keys inside your pocket. “I'm not an amateur.”

Playing along, he laughs, hand still holding your elbow softly. “Good job, missus.”

With an awkward chuckle, you lean away from him. “Just so you know, I'm not in this for…the romance.” You bite the inside of your cheek. “I'm not looking to date my co-worker.”

John raises his hands in mock surrender. “Fine by me. if the situation calls for us to actually act as a couple—”

“We'll act as a couple, I won't fuss if that's what you're saying.”

“Good, now let's get this bloody car.”

—

“A fucking ‘99 toyota corolla?” You stare in disbelief at the rusting metal. “At least it's one of the good models.” Kicking the wheel, you expect it to tumble over like in an old timey cartoon.

John is crouched way down to check the bottom of the car. “It's clear.” He stands up fully, cleaning his hands on his jeans. You wince at his movements. “What?”

“Nothing.” You open the driver's side, the smell of alcohol and something musty hits your nose. “Nasty.” Coughing, you air it out by opening another door.

“You know your cars?”

“A little bit.” You say with your nose pinched. Sparing him a look, he stands in the parking lot like he's still waiting for the rest of the story. “What?”

“Throw me a bone here, love.” You roll your eyes. “Why do you know so much about cars?”

“I said I know a little bit.” You place your hands on your hips like an exasperated mother whose son keeps asking weird questions about dinosaurs. “I dated a mechanic.” You say flatly.

“Really? Did you date a pickpocket too? Or do you date people so you could absorb their skills like kirby?”

“Are you jealous?” You tease him with a comment you didn't have the foresight that it would backfire.

“We are married.” He says matter-of-fact with a killer smirk and eyes glinting with mischief. “And this is technically our honeymoon so—”

“Get in the fucking car, birdman.”

—

The wheel is sticky under your hands, you have an intense urge to wash your hands or to at least grab a sanitizer. Apparently your disgust shows on your face, for John chortles next to you.

“What?” You say through gritted teeth.

“Nothin’, you just look like someone shat in your tea.”

“The wheel is sticky.”

“I have a handkerchief with me, d’you want me to?” Taking out the dark green cloth from his jean pockets, he's already twisting in his seat to wipe it clean.

“Please,” you ask softly, hands sliding down to make space for him.

Your hand never left the wheel while he cleans it for you. John's seatbelt is unclasped so he could have more movement, his face is close to your vision, warmth blanketing over you. He's so close that you can smell his cologne, it's a different one from yesterday, it's more flowery with a hint of mint. You spot a hidden mole under his ear. A tiny dot that is just begging to be poked.

Without thinking, you press softly with the pad of your finger. He yelps, flinching away instinctively. Looking at you with wide eyes and mouth agape, you're ready to be called a nasty nickname, or be cussed out with a loud voice. Instead of what you're anticipating, a laugh bellows out, a rumbly laugh that makes you smile and let out an almost silent chortle.

“I think you found my mole.” John holds the side of his neck with a grin. “You let your urges get to you, love.”

“Sorry,” you keep your eyes on the road to hide your embarrassment.

“It's fine, your hand was just cold. Ask me next time, I have a few more cute moles on me.”

“Nevermind, you ruined it.” With a roll of your eyes and a smile, you park at the coordinates. “Nice acting back there, I see an Emmy nomination for you in the future.”

“Thanks, I barely remember what I said. You sure this is the place?” John peeks at the map pulled up on your phone. “Shit, we're here.”

The entire street is suburban, large colonial houses lining the sides, tall pine trees decorate the sidewalks. There's not a lot of people walking by, save for a couple pedestrians walking their dogs, the place is devoid of people.

“What now?” You unclasp your seatbelt to twist around in your seat so you could observe the neighborhood.

“Hihi told us to bring it here, so maybe we should—?” John lets out a high pitched scream that also has you yelling in surprise, not from whatever made him shriek but from the sound that escaped him. “What the fuck!”

Leaning slightly to look at what had his knickers in a bunch, you stare blankly at a bespectacled man in a bespoke suit. The man gives you and your partner an apologetic look, he points for John to open the window.

He turns towards you with an eyebrow raised. “Should I?”

“Yeah, I think you should.”

“What if he's got a gun?” He whispers.

“We also have guns, John. I'll cover you, don't worry. Maybe this is what hihi asked us to do.”

“Easy for you to say, you're not the one opening it.” He gives you a glare before rolling the window down an inch. “Hi, mate. What can we do for you?”

“The car,” the stranger points a lengthy finger at the wheel. His voice is crackly and gravelly, like he just smoked a pack of cigarettes before he went up to the car. “You're late, but that doesn't matter. How much do I owe you, folks?”

“Uh, the usual.” You say with fake confidence.

“Good,” the lean man straightens up, “mind gettin’ out of the car then?”

“Right, sorry, bruv.” John, gives you one look before exiting the car. He's nervous and so are you.

As the doors shut, the man flexes his open palms expectantly for the keys, to which you hand off immediately. He gives you bad vibes, maybe your intuition tells you to run for the hills.

“Thank you, sweetheart. I'll wire the money to the usual account.” The nickname sends shivers down your spine.

He closes the door and starts up the car. With a splutter of the exhaust, he slowly drives away. You and John watch, standing side by side in the middle of the street in confusion.

“He was weird, right? Not to mention it was too easy.” You turn your head to look at him. “Maybe they're trying to ease us in?”

“It was all weird, not just him—” A blast coming from the car interrupts him, the sheer force of it sends you two down on the rough pavement.

Your cheeks are incredibly warm from the searing heat of the bomb. The light from it blinds the two of you.

Palms skinned, trousers slashed at the knees, your ears ring loudly like an annoying buzz from a broken microphone. Coughing loudly, smoke fills your lungs, debris is scattered around the once pristine neighborhood. There's blood on the concrete, you can't hear John calling for you, your vision is blurred by the cloud of smoke. His hand reaches for you, and your instincts tell you to run.

“Fuck!” He yells, running beside you at full speed. “What the fuck!”

“Keep running!” You yell as he turns around to check on a woozy you. “I'm fine!”

Someone behind you screams for you to stop so you and your partner run faster. Knees aching, thighs burning, you don't stick around to look who's running after you. The unmistakable click of a gun’s safety is loud in your eardrums, even if your lungs threaten to give out, you sprint right next to John as he turns a corner and into a carwash.

The smell of soap and heavy pine scented car freshener hits your bloody nose. He tugs you towards the plastic curtains and inside what you presume as the employee lounge, someone yells after you but it falls on deaf ears as you and John continue your escape.

Exiting the establishment, the metal doors open to a messy alleyway. Boxes upon boxes of trash and god knows what are littered all around. The pungent smell makes you want to hurl, or maybe that's the adrenaline having a weird effect on your stomach.

You two find reprieve for a second, huffing, trying to get oxygen back in. Hands on your aching thighs, the concrete below you slowly turns crimson as your mysterious injury drips precious blood on the messy ground.

“You're bleedin’” He says in between inhales. There's rustling of fabric next to you, and you feel the warm cloth placed on your forehead.

“No shit, Sherlock.” Waving the drenched cloth away, you scoff lightly. “Don't.”

“What am I supposed to do? Let you bleed?”

You stand up straight, blood coating your lashes as you stare at him. “I've got a better idea.” Placing your palms on the source of the pain, you let your blood coat it.

“What—?” You roughly smudge the warm ichor all over his face and shirt, the plain white of his t-shirt turns a dark pink shade with your touch. Leaning away, he gives you a slow nod of understanding. “Ease us in, huh?”

“I'm rarely wrong and this is one of the rare instances.”

“Let's hope you're right about this one.”

—

You kick the backdoor open with ferocity. It bangs loud against the wall, getting the restaurant staff's attention.

“Help please! My husband!” John's limp arm is around your shoulders, your hand gripping on to his waist to add that one detail that would convince them of your innocence. “There was a bomb!” You don't let the bystanders touch you or John whilst you quickly lumber through their dinghy bathroom. There's murmurs and chairs scraping on the tiled floors as you lock the door behind you.

The bathroom is small, tiles yellowed from the years, the stench of bleach itching your nose. The lightbulb above you whirs like it's about to burst out. He leaves your side to take off his bloodied jacket, tossing it outside from the window— his exit, you presume.

“Your phone.” He holds his empty hand out to you, when you only raise an eyebrow at him, he sighs, eyes turning soft, adrenaline melting out of his system. “Please, c’mon, love, you got me sayin’ please and shit.”

“What for?” You try desperately to wipe the blood off your face.

“To contact you, just in case you need help.”

“I can handle it.”

“I know you can, how else did you get the job then? Just let me,” his voice wavers a bit but he corrects himself with a timed clear of his smoke filled throat. “Please, Jane.”

After pausing, you take your phone out from your pocket to give it to him. He enters his number after seeing your home screen of a basic mountain range.

“There.” Giving the phone back, you expected him to give his too, but he doesn't as he's already halfway out of the window. “I'll see you at home?”

You let out a chuckle, “yeah, I'll see you at home.” He gives you one last smile as he exits the small bathroom and into the streets where numerous sirens go off from ambulances and fire trucks.

—

It was a blur the entire trip home, you bought a loose hoodie from a thrift store and then promptly discarded your blood soaked coat in the bottom of a dumpster. It was a shame though, you liked that coat, it had real wool in the lining. The uber drive was thankfully uneventful, if the driver noticed the remnants of dried blood on your skin he didn't mention it. You gave him five stars for it.

An empty house greets you, John's shoes are nowhere to be seen in the hallway, nor his jacket. You worry for a second, mind rushing through possibilities. The rubber band burns as you pull it back and release it with a harsh thwack against your skin.

The water is cool as you shower, your blood mixing in and pooling around your feet and into the drain like a macabre whirlpool. You don't let your mind wonder about the man that you turned into a street pancake. Instead, you focus on yourself in the mirror.

You stare at the gash near your hairline, the skin around it is angry, leaving a throbbing sensation. There's also a few scratches on your face, especially around your chin. Your main concern is the large gash. It doesn't look like it needs to be stitched together though, which is a good thing since you don't have the energy to even tend to the tiny scratches on your palms. Cleaning and bandaging the wound, you put on clean pajamas and head to bed.

You stop in your tracks when you see John lying face down on your bed. Still in his iron soaked clothes, save for the jacket. You glare at his boot, it's off the bed but you still grit your teeth at the thought of it grazing your bedsheets.

He senses your presence, and he lifts his head up, chin helping prop himself up. “Your bed is better than mine.” His multi coloured eyes are laced with exhaustion, dull yet there's still a spark when he looks at your annoyed gaze.

“Who are you? Goldilocks?”

“Yeah, I ate your porridge too.”

“Damn, not my porridge.” Too tired to fight him, you slither into bed next to him, an arm's length away from his equally tired body. Staring at the ceiling, you feel his eyes on you. “What's up with your eyes?”

“It's called heterochromia—”

“I know what it is, I'm asking why you're staring at me like you're about to devour me.”

“I could devour you if you want.” He says nonchalantly but with the charisma of a man who knows what he's talking about.

“Maybe next time.” You blindly pat his shoulder which ended up with you patting his cheek. He hums at your touch, a deep rumble that you felt through the mattress. “Not bad for our first day huh?” Lifting your hand away, he twists on the bed to mirror your position. Now you're both gazing at the beige ceiling like it owes you money.

You're tired but for some reason you're fighting off the sandman from sprinkling sand in your heavy eyes.

“I lied back there, I've killed before.” His voice is merely above a whisper but you heard it as loud as a trumpet blaring in your ears.

“I know, you wouldn't be here if you haven't.” You answer with empathy. “If it makes you feel better, I've been to London before. Twice, on a family trip and a decade later…on vacation.”

“Glad to know.” He taps the inside of your elbow as a thank you for trusting him. “You CIA?” He blurts out above the comfortable silence.

“God no.” You truthfully say.

“And here I thought you're an alumni of the culinary institute of America.”

For the first time in years, you let out the loudest laugh you could muster. Snort and all.

Your ‘husband’ joins in with his own rambunctious laughter, the bed shakes at the loud guffaws. The happy sound fills the room, and your heart feels like it isn't as heavy as before. It's still there, the heaviness, but it isn't as cumbersome. You now realize that you've only snapped the rubber band on your wrist a couple times today.

An annoying tapping sound interrupts you both. Simultaneously sitting up by the elbows, you two tilt your head at the intruder.

“It's that pigeon again.” You actually smile at the thought of the same bird coming back to your house like a white strand of hair that keeps growing even after you've pulled it out. “I think we should name him. Something like Terry or Flanders.” You chuckle softly.

“Jeff.”

You shake your head. “Nope, doesn't suit him, what if it's a she?”

“His name is Jeff.” John turns to look at you, eyes full of certainty.

You turn to him, blinking rapidly in realization. “He's yours. He's your bird, isn't he?”

“You are insightful.” He smiles, a soft one that fills you with endearment that you haven't felt in years. “Met him a few months ago, fed him once and now he wouldn't leave me alone. I guess he followed me here too.”

“Y’know, pigeons are really smart, kinda like crows. He probably thinks you're his daddy.”

“Does that make you Jeff's mummy?”

“I don't want to be Jeff's mom.” Said bird taps on your window again, like he senses that you're currently talking about him.

“Too bad,” he raises his marriage finger, showing you the gold band. “He's our kid, love.”

You smile, hiding it with a huff and by laying back down with a gentle thump.

“Can I tell you somethin’?” His face pops up in your vision, you nod in place. “My real name is—”

“Let me stop you right there.” You sit back up, almost hitting his head with your own at how fast you sat. “There's a reason why they gave us fake names. Whether we like it or not, It's John,” You point at him. “And Jane Smith.” You point at yourself. “Until they dismiss us, that's our names. Not whatever you were about to tell me.”

“But you know it's not our names, right?”

“Of course I do. You don't look like a John, John.”

“And you don't look like a Jane. I just…” He sighs. “Just want someone to know my real name. We almost died back there, what if we stayed a minute longer inside that car? What then? I don't want to die with someone else's name written on my grave.” His words are genuine, but it sounds like he has said these words before.