#theoryofuniverse

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Where are all the aliens Fermi Paradox

The Fermi Paradox is a question which asks -- "Where are all the aliens?" The universe is estimated to be around 13.7 billion years old, and there are roughly 100 billion stellar systems in our galaxy. According to NASA's Kepler Space Telescope, there could be as many as 30 billion Earth-sized planets in the Milky Way alone with similar conditions to Earth, meaning they could support life. Who Described Fermi Paradox first? Many people have asked this question before

#whereareallthealiens#fermi#paradox#theory#theoryofeverything#theoryofuniverse#universe#univers#universeexplained#space#spaceexploration#spacetravel#discover#star#stars#science#exoplanet#aajkaakhbaar

0 notes

Photo

🌚🌎🪐🌝 The Parallel Universe Concept, also known as a parallel dimension, alternate universe, or alternate reality, there’s another universe just like ours is co-existing with one's own. It constitutes a reality is often called a “Multiverse". Best example is the movie 🎥 Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse Our science states that the 🌍 magnetic 🧲 field or the combination of opposing forces cause a Storm ⚡️🌪. But If another universe exists in other dimension, eventually when the two 🌎 collides with each other causes storm ⚡️☄️ 🌪 in both side of the world. . . . . . . . . . . . #universe #storm #nature #multiverse #multiverseconcept #paralleluniverse #trees #world #theoryofuniverse #photooftheday #photomanipulation #naturephotography #picsart #reflectioneffect #earth #astronomy #galaxy #space #imaginativeuniverse (at Pune, Maharashtra) https://www.instagram.com/p/CBf_eJJshEg/?igshid=608nd006lemh

#universe#storm#nature#multiverse#multiverseconcept#paralleluniverse#trees#world#theoryofuniverse#photooftheday#photomanipulation#naturephotography#picsart#reflectioneffect#earth#astronomy#galaxy#space#imaginativeuniverse

0 notes

Text

On the Greek Origin of “Species”

Idea = Species

The above equation has truth in the formal study of philosophy, even though colloquially, this is not generally taken to be the case.

Let’s start by examining the etymology. The word idea, as it turns out, is simply a feminine form of the root word eidon from ancient Greek. With this in mind, it’s specifically the history of the neutral form eidos that will uncover the association to the modern species.

The story begins with the Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle, who were two of the most influential historical figures in establishing the foundations of modern philosophical reasoning. While the Greek terminology have their own original meanings, their specific usage is often tailored individually by these two philosophers depending on the subject of interest across their works. As such, both men can be said to have contributed significantly to the practical definitions of such terms within the context of modern philosophy.

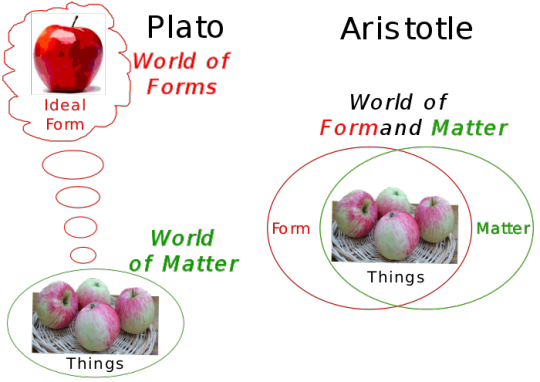

To understand then how eidos became species, we can start by separating Plato from Aristotle by their take on the Problem of Universals. The Problem of Universals starts by suggesting that universals are characteristics that ordinary objects or things are observed to have in common. As an example, consider a bowl of red apples. Each apple in the bowl will have several similar qualities, such as the color of "redness". Taking other qualities such as size, shape and texture into account, we can further conclude that all the apples in the bowl share the universal quality of "appleness". Both appleness and redness, as well as all the other minute shared qualities of the apples, can all be taken to be the universals that the apples hold in common.

When considering the concept of universals, the Problem of Universals poses three questions: (1) Do universals exist? (2) If they exist, where do they exist? And (3), if they exist, how do we obtain knowledge of them? Plato's solution to these questions is known as the Theory of Forms.

Plato's Theory of Forms

Plato's worldview suggests that the physical world is not as real or true as the timeless, unchanging and absolute Ideas (or Forms) that it is based upon. So universals in the Platonic worldview are essentially these "Forms". These Forms, are the non physical essences of all things, of which objects and matter in the physical world are merely imitations. Plato then suggests that there exists some immaterial "World of Forms", which is separate from the physical world, and is effectively, home to these ideal, timeless and absolute Forms. He also posits that these Forms are the only objects of study which can provide knowledge.

Aristotle's Theory of Universals

Aristotle on the other hand suggested that universals are both incorporeal and omnipresent, but only exist where they are instantiated, i.e. universals only exist in things. He also mentioned that a universal is identical in each of its instances- so going back to our red apples, all red things would be similar in that there is the same universal redness in each thing. There is then, no ideal Platonic Form in this theory. Rather, each instance of a thing carries a copy of the same universal property. Lastly, in Aristotle's world view, knowledge of a universal is not obtained from a supernatural source world, but rather gleaned from a consideration of its material form via an experience he termed active intellect (we will revisit active intellect later on).

To summarize, we can consider the image below:

Both the Theory of Forms and the Theory Of Universals attempt to consider the physical objects apart from the immaterial qualities that they possess. This way of analyzing the world is the fundamental reasoning underlying the branch of philosophy known as metaphysics.

Returning to the concept of eidos (ideas) as species, the Aristotelian study happens to be the branch that will reveal to us our link. To better understand Aristotles concept of species, we'll first examine his system of Logic, followed by his study of early Biology.

Species in Aristotle's Logical Study

Perhaps the best way to start in Aristotle's Logical metaphysics is to consider his general conception of potentiality vs actuality. With his Theory of Universals worldview in mind, you can think of the process of actualization as one in which things "move" from their immaterial potentiality (or potential to exist), to their fully existing material actuality (as an action, movement, object, etc). Interestingly, this process of actualization applies for objects as well as thoughts, with the actualization of thought providing the basis for his study of formal logic.

Logic, as a philosophical study, can be taken as the study of argumentation. In other words, it is the formal study of how we conceptualize and assert arguments, which are statements of what we conceive to be “real” or “true”. With this in mind, we can observe that the root of the word logic happens to be logos, which is the Greek term meaning "word"or "speech".

Aristotles central logical concept is the deduction or syllogism. He defines a deduction in his work Prior Analytics, as:

A deduction is speech (logos) in which, certain things having been supposed, something different from those supposed results of necessity because of their being so. (Prior Analytics I.2, 24b18–20)

Each of the “things supposed” is a premise (protasis) of the argument, and what “results of necessity” is the conclusion (sumperasma).

The core of this definition is the notion of “resulting of necessity”. As an example, consider that z results of necessity from x and y, if it would be impossible for z to be false when x and y are true. We could therefore take this to be a general definition of a “valid argument”.

Aristotle would use these logical principles to construct what he termed genus-differentia definitions. A definition in his metaphysics concerns itself with the notion that what can be "defined" is only that which has an "essence". As such, Aristotle's notion of a definition was to place every object into a family (or genus proximum) and then to differentiate it from the other members of that family by some unique universal (differentia specifica). All objects which follow a certain genus-differentia are what he termed as eidos (in Greek) or species (in Latin). As an example, "human" might be defined as an animal (the genus) having the capacity to reason (the differentia). Put differently, the definition of a human (species) is the two part “Animal (genus) that Reasons (differentia)”.

Aristotle’s genus-differentia species became the root of what is known today as binomial (two names) nomenclature (naming system), and is most notably used in the Linnean system of biological taxonomy.

To summarize, it may be helpful to think of the mechanisms of deductions and genus-differentia as Aristotle’s means of "moving" ideas from the "space" of potentiality to the "reality" of actuality. And while he doesn't really define this clearly, we can also think of this actualization process as that which underlies what was previously referred to as Aristotle's active intellect.

Species in Aristotle's Biological Study

Ironically, theres less to say about species as considered from Aristotle's biological study. That said, it would be remiss to explore this topic without noting that Aristotle was perhaps the first major contributor to pre-evolutionary Darwinian biology. Importantly, the term eidos does in fact repeat itself frequently within the biological study, where Aristotle sets out to erect his own animal taxonomy.

I mentioned in a previous article about the difficulties in modern taxonomy of separating species discretely. Essentially, the nature of animal species happens to be such that their differences are fundamentally continuous and arbitrary from one "species" to the next. A major demarcation of species in post Darwinian taxonomy is inter sterility, or the the inability of one population to reproduce with another. Aristotle however, is mostly uninterested in limited hybridization as a marker of eidos, instead attributing inter sterility to what he considered nonessential differentia, such as gestation periods and body size.

The essence necessary to define a true species, would then necessarily be defined by essential differentia. Rather than abstracting this essence from a collection of common characteristics among members, Aristotle instead focuses on those prime characteristics which are necessary for the existence of the species.

Thus large groups of animals are distinguished first by that which maintains their life (blood or some other fluid), and the "blooded" animals are distinguished by their mode of reproduction (vivipara, ovovivipara, ovipara). Other characteristics which Aristotle often uses for distinguishing the larger groups include location of “life” (water or land), means of cooling (i.e., respiration), type of food, method of locomotion, etc. The major distinctions between kinds of animals are all made in terms of the ways in which these animals carry out the functions which are necessary for life and for the continued existence of the species. From Aristotle's point of view, features which are conditionally necessary for life are most obviously their essential differentia.

Summary

To conclude, our link between species and ideas comes primarily via the ancient Greek eidos, as explored within the works of Aristotle's logical metaphysics and early biological taxonomy. It's worth remembering the process of the active intellect as that which takes all species in Aristotle's worldview from potentiality to actuality. Though it wasn't covered in this write up, there's reasonable evidence throughout Aristotle's works to also suggest that he considered this systematic way of thinking as consistent and applicable across several arenas of complex life, having applied a systematic approach to classifying everything from political systems, to pleasurable experiences. In the modern sense, this also makes Aristotle an early contributor to the mode of investigation known today as "systems theory".

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eidos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Species_(metaphysics)#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20a%20human%20being,species%20in%20Aristotle's%20corpus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Predicable

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle%27s_theory_of_universals

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theory_of_forms

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-logic/#SpeGenDif

https://orb.binghamton.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1085&context=sagp

https://davesgarden.com/guides/articles/view/2051

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evolution-before-darwin/

http://www.fossilized.org/anthro_textbook/index.php?subtopic=Aristotle,%20Linnaeus%20and%20the%20Typological%20Species%20Concept&week=2&topic=Species%20concepts&topic_subdb=Species%20concepts&subfield=Evolutionary%20Biology

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B3Avpz-mXU0

https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%E1%BD%81%CF%81%CE%AC%CF%89

https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1970/04/09/plato/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249901495_Eidosidea_in_Isocrates

#aristotle#plato#species#theoryofuniversals#theoryofforms#philosphy#logic#eidos#genus#differentia#nature#ideas#darwin#evolution#taxonomy#greek#greece

1 note

·

View note